Abstract

Objective

In light of the current FDA proposal to ban menthol cigarettes, this study updates trends in menthol cigarette use among adolescents age 13–18 up to the year 2020. The study considers a potential role for the ban to reduce Black/nonblack disparities in menthol cigarette use, as well as a counterargument that a ban is not necessary because menthol use is already diminishing.

Methods

Data are from annual, cross-sectional, nationally-representative Monitoring the Future surveys of 85,547 8th, 10th, and 12th grade students surveyed between 2012–2020. Analyses include trends in past 30-day menthol and nonmenthol cigarette smoking among the total adolescent population, as well as stratified by race/ethnicity.

Results

Declines in adolescent menthol and nonmenthol cigarette smoking continued through 2020 so that in 2018–20 past 30-day prevalence for each was less than 1% for non-Hispanic Black adolescents and less than 2.2% for nonblack adolescents. For non-Hispanic Black adolescents no smoking declines in mentholated or nonmentholated cigarette use from 2015–17 to 2018–20 were statistically significant, in part because prevalence levels approached a floor effect and had little room to fall further. Menthol levels were lower for non-Hispanic Black v. all other adolescents in all study years.

Conclusions

Continuing declines in adolescent menthol prevalence indicate that both menthol prevalence and also Black/nonblack disparities in its use are steadily decreasing. However, these decreases in adolescence will take decades to reach later ages through generational replacement. Efforts to accelerate menthol decreases will require new initiatives to increase cessation among adult menthol users.

Introduction

Progress in the reduction of menthol smoking prevalence, as well as accompanying disparities across race/ethnicity, has become a key issue for national smoking policy. In an effort to further such progress, the FDA recently announced that it is working toward a ban on menthol as a characterizing flavor in cigarettes.1 In response, organizations such as the ACLU have suggested that such a ban may not be necessary because current policies are working and both menthol smoking, and perhaps also the associated disparities by race/ethnicity, are on their way out.2 In this paper we provide an update on recent, national trends in adolescent menthol and nonmenthol smoking prevalence from 2012 to 2020, with an emphasis on potential differences in these trends for Black adolescents.

Background

Menthol is a chemical that manufacturers commonly add to cigarettes. It serves to mask some of the harshness associated with the inhalation of cigarette smoke.3 This anti-irritating property might be particularly important for youth novice users who are likely to be unaccustomed of the airway irritation caused by nAch receptors from tobacco smoke and therefore might discontinue smoking after having and unpleasant initial experience.4,5 While almost all cigarettes sold in the U.S. contain at least some menthol,3 brands marketed specifically as “menthol” usually have substantially higher concentrations of the chemical and are often advertised with the themes of “smooth,” “cool,” “fresh,” and “pleasure.”6 U.S. federal law prohibits tobacco companies from marketing cigarettes with any taste (i.e. “characterizing flavor”) other than menthol or tobacco.7

Three attributes of menthol cigarettes have raised alarms and drawn calls to prohibit them. First, adolescent smokers use them at higher levels in comparison to older smokers,8–10 and adolescents report they are easier to smoke.11 Second, adolescents who use menthol v. nonmenthol-flavored cigarettes report higher levels of dependence and addiction symptoms, such as cravings,9,10,12,13 tolerance,13 and reduced time until needing another cigarette.9,10,12 Consistent with these findings, adolescents who smoke menthol are later less successful in quitting smoking.14 Third, Black smokers are more likely to use menthol than are smokers of other races and ethnicities,11,15 in part because of tobacco marketing strategies that have focused on Black communities.16 This concentration of menthol use in a minority population has led some to propose banning menthol cigarettes as a social justice issue.17

On April 29, 2021 the FDA announced that it is advancing a tobacco product standard within the next year that will ban menthol as a characterizing flavor in cigarettes.1 The rationale for this action, according to the FDA announcement, is to save lives and, relatedly, to reduce youth initiation of smoking. An additional rationale listed in the announcement is to reduce disparities in menthol smoking between African Americans and other racial/ethnic populations.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU)2,18 and some prominent African American opinion leaders19 have expressed concerns about this potential ban and suggest its consequences may outweigh its benefits. Their main concern is that it could criminalize menthol cigarette sales and distribution. They emphasize that an unintended consequence of the ban is that it could contribute to the history of U.S. drug laws that have disproportionately impacted the Black population and substantially contributed to their higher rates of incarceration.20 They advocate continuation of current cigarette policies that have had remarkable success in reducing adolescent cigarette use over the past two decades.21

The proposed menthol ban and the reaction it has elicited raises at least two research questions that this study addresses. First, we ask whether and at what rate decreases in adolescent use of menthol cigarettes have occurred and are currently taking place. Second, we ask if these decreases trended differently across race/ethnicity, particularly for Black adolescents.

This study focuses on adolescence because this life stage plays a key role in efforts to reduce population prevalence of smoking, and specifically of menthol smoking. Almost all adults who smoke first began in adolescence, with 90% of smokers aged 30 to 39 reporting cigarette initiation before they were age 18.22 Over the past two decades reductions in cigarette smoking – menthol or otherwise – follow a distinctive “cohort” pattern in which population-level declines first start in adolescence and then stay with birth cohorts as they age into adulthood.23,24 Adolescent prevalence of menthol and nonmenthol cigarette plays a large role in shaping adult prevalence levels in later years.

The most current, published estimates on adolescent menthol cigarette use reported a substantial decrease in adolescent use of menthol and nonmenthol cigarettes through year 2018.25 For all race/ethnicities combined in grades 6–12, national prevalence of past 30-day menthol cigarettes use fell from 6.2% in 2011 to 2.5% in 2018.25 For nonmenthol cigarettes prevalence fell from 4.1% to 2.5%.25 While decreases in nonmenthol cigarettes date back to at least 2004,8 evidence for a decrease in adolescent menthol use is more recent and was not found in earlier analyses for the time period from 2004 to 2010.8,26

Information comparing adolescent menthol use across Black and nonblack adolescents is more dated. From 2004 to 2010 past 30-day menthol prevalence was similar for non-Hispanic Black and white adolescents age 12–17, at 5.3% and 5.2% respectively.8 Menthol prevalence was lowest for Hispanics at 3.9%.8 Over this time period prevalence of menthol use changed little for any of these groups. Much remains unknown about prevalence levels and trends by menthol status across these racial and ethnic groups past 2010.

This study contributes to the field in three ways. First, it updates trends in U.S. adolescent menthol cigarette use up to 2020. Second, it fills a gap in the literature and presents these trends for Black and nonblack adolescents past 2010, up to the year 2020. This information is directly relevant for current policy discussions on menthol cigarette regulation. Finally, this study is the first to present information on menthol cigarette questions added to Monitoring the Future in 2012. As the largest nationally-representative, annual surveillance resource that collects data on menthol cigarette use in youths, MTF brings to the field an additional, nationally-representative data set for triangulation and comparison of findings with other national analyses on this topic.

Methods

Data

Data come from the annual Monitoring the Future study, which uses self-administered questionnaires in school classrooms to survey U.S. students.27 The project has been approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board, approval #HUM00131235. The project draws three, independent, nationally-representative, cross-sectional samples of 8th, 10th, and 12th grade students each year. Data for this study come from the nine annual surveys between 2020 and 2012, which is the first year the survey included questions on menthol and nonmenthol cigarette use. Student response rates averaged 89%, 87%, and 81% in 8th, 10th, and 12th grades respectively. The great majority of non-response is due to student absence. For a detailed description of the survey methodology see Bachman et al.28

The main analytic sample consists of 85,547 respondents who provided information on all measures. These respondents are out of a total sample of 101,879 who provided information for at least one measure, of whom 98,401 provided information on the dependent variable of past 30-day smoking and menthol cigarette use. Questions on menthol cigarette use were administered to a randomly-selected 1/6 of students in 12th grade and to a randomly-selected 1/3 of students in 8th grade and in 10th grade. Analyses combined all three grades into one analysis pool, in light of analyses showing similar results in each grade (reported as sensitivity analyses in the results section below).

Table 1 lists all variables used in the analysis, their definitions, response categories, and sample proportions. Years are grouped into three-year intervals for Figure 1 and Table 2, for three reasons. First, MTF typically combines at least two consecutive years of data when presenting outcomes by race and ethnicity so that sample sizes for smaller demographic groups are large enough to produce more stable prevalence estimates, especially when prevalence is low.29 Second, data collection in year 2020 was curtailed as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. While this resulted in a sample size about 25% the size of a typical data collection, analyses support the results from the curtailed, 2020 data as nationally-representative.30 Given the smaller sample size, the combination of 2020 data with both 2019 and 2018 seemed prudent to ensure sufficient sample size. Third, the survey contains nine years of information on menthol use, and three-year groupings serendipitously result in three equally-spaced intervals.

Table 1:

Variable Definitions and Proportions (95% Confidence Intervals in Parentheses)

| Measure | Prevalence (95% C.I.) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Smoked any Cigarette in Past 30 Days | |

| Question: How frequently have you smoked cigarettes during the past 30 days? Coded 1 for any response greater than zero. | 6.40 (6.06–6.74) |

| Smoked a Mentholated Cigarette in Past 30 Days | |

| Question: Are the cigarettes you usually smoke menthol? (asked only of respondents who reported smoking a cigarette in the past 30 days). Coded 1 for a response of yes. | 3.18 (2.96–3.39) |

| Smoked a Nonmentholated Cigarette in Past 30 Days | |

| Question: Are the cigarettes you usually smoke menthol? (asked only of respondents who reported smoking a cigarette in the past 30 days). Coded 1 for a response of no. | 3.23 (3.01–3.45) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | |

| Question: How to you describe yourself (Select one or more responses)? Coded 1 for respondents who marked only “Black or African American” and were not coded Hispanic. | 11.98 (11.03–12.92) |

| Hispanic | |

| Question: How to you describe yourself (Select one or more responses)? Coded 1 for respondents who marked “Mexican American or Chicano,” “Cuban American,” “Puerto Rican,” or “Other Hispanic or Latino.” | 24.02 (22.65–25.39) |

| Non-Hispanic White | |

| Question: How to you describe yourself (Select one or more responses)? Coded 1 for respondents who marked only “White (Caucasian)” and were not coded Hispanic. | 52.49 (50.91–54.07) |

| Other Race | |

| Question: How to you describe yourself (Select one or more responses)? Coded 1 for respondents who were not coded Hispanic and marked “Asian American,” “American Indian or Alaska Native,” “Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander” and/or multiple races. | 12.17 (11.57–12.77) |

| Female | 51.59 (51.06–52.12) |

| Question: What is your sex? Coded 1 for respondents who marked “Female.” | |

| Parent has college degree | |

| Questions: “What is the highest level of schooling your father completed?” and “What is the highest level of schooling your mother completed?” Coded 1 for a marked response of “Completed college” or “Graduate or professional school after college” for either father or mother | 56.68 (55.55–57.80) |

| Year of Surveya | |

| 2012–14 | 36.24 (33.73–38.75) |

| 2015–17 | 36.67 (34.21–39.14) |

| 2018–20 | 27.09 (24.78–29.40) |

| Grade of Respondentsb | |

| 8th Grade | 34.42 (31.75–37.10) |

| 10th Grade | 36.73 (33.9–39.57) |

| 12th Grade | 28.85 (26.34–31.35) |

In 2020 the COVID pandemic curtailed data collection, resulting in a sample about one-quarter the size of a regular data collection. Detailed analysis supports the 2020 sample as nationally representative.30

In all years the survey administered questions on mentholated cigarettes to a randomly selected one-third of 8th and 10th grade students and one-sixth of 12th grade students. All analyses are weighted so that the 8th, 10th, and 12th grade samples have a relative influence proportional to the size of these grades in the U.S. national population.

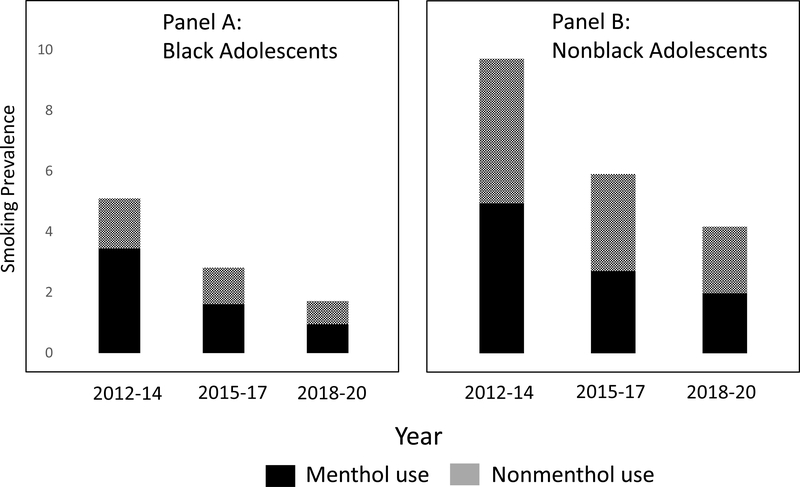

Figure 1:

Prevalence of Past 30-Day Smoking by Menthol and Nonmenthol Use, Year, and Race

Table 2:

Unadjusted Prevalence of Cigarette Use in the Past 30 Days, by Black/Non-Black Race and by Year (95% Confidence Intervals in Parentheses)

| ----------------- Years of survey ----------------- | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2012–2014 | 2015–17 | 2018–20 | |

|

| |||

| Any Cigarette | |||

| All | 9.17 (8.54–9.85) | 5.52a (5.08–5.99) | 3.89a (3.42–4.42) |

| Black | 5.10 (4.14–6.28) | 2.82a (2.12–3.74) | 1.71a (1.09–2.67) |

| Nonblack | 9.71 (9.02–10.46) | 5.91a (5.43–6.42) | 4.17a (3.66–4.75) |

| Mentholated Cigarette | |||

| All | 4.77 (4.34–5.23) | 2.57a (2.31–2.86) | 1.86a (1.59–2.18) |

| Black | 3.45 (2.72–4.37) | 1.61a (1.11–2.31) | 0.95 (0.51–1.75) |

| Nonblack | 4.94 (4.48–5.45) | 2.71a (2.43–3.03) | 1.98a (1.68–2.33) |

| Nonmentholated Cigarette | |||

| All | 4.41 (4.02–4.83) | 2.95a (2.65–3.28) | 2.03a (1.72–2.39) |

| Black | 1.65 (1.14–2.39) | 1.21 (0.79–1.84) | 0.76 (0.43–1.34) |

| Nonblack | 4.77 (4.35–5.23) | 3.20a (2.87–3.56) | 2.19a (1.85–2.59) |

Prevalence level significantly differs (p<.05) from previous time period.

Note: Prevalence significantly lower (p<.05) for black as compared to nonblack adolescents In all three time periods for all outcomes.

Note: Figure 1 presents a graph of these results.

Race and ethnicity measures are based on self-reported answers to the question “How do you describe yourself?” which has the response categories of “Black or African American,” “Mexican American or Chicano,” “Cuban American,” “Puerto Rican,” “Other Hispanic or Latino,” “Asian American,” “White,” “American Indian or Alaska native,” and “Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander.” Students who marked only “Black or African American” are coded as Non-Hispanic Black. Students are coded as Hispanic if they mark “Mexican American or Chicano,” “Cuban American,” “Puerto Rican” or “Other Hispanic or Latino.” Students who mark “White” and no other categories are coded as non-Hispanic White, and students who marked the remaining categories and/or multiple categories are coded as “Other Race.”

Analysis

Analyses include trends in observed prevalence levels as well as multivariable regressions. For all regressions the analysis presents relative risk ratios, estimated using a generalized linear model with a binomial distribution for the residuals and a log link function.

Analyses use STATA “svy:” commands to take into account sample weights, as well as clustering of respondents in primary sampling units. With the probability weights, each year has equal influence on the study results, despite differential sample sizes. In addition, the weights are set so that each grade has an influence on the analysis proportional to its size in the U.S. population.

Results

Figure 1 and Table 2 present trends in menthol and nonmenthol cigarette prevalence from 2012 to 2020. Four main findings are of note. First, prevalence of both menthol and nonmenthol cigarette continued downward through 2020. Both fell by more than half from 2012 to 2020 among both non-Hispanic Black and all other adolescents.

Second, levels of absolute decline in cigarette prevalence were smaller for non-Hispanic Black as compared to all other adolescents. For example, from 2015–17 to 2018–20 the absolute decline in menthol smoking for non-Hispanic Black adolescents was 0.66% (from 1.61% in 2015–17 to 0.95% in 2018–20) compared to 0.73% for all other adolescents (from 2.71% to 1.98%). Smaller absolute declines for non-Hispanic Black as compared to all other adolescents took place across all time periods for menthol, nonmenthol, and overall smoking (Table 2).

These smaller, absolute declines for non-Hispanic Black adolescents took place despite larger relative declines. For example, the relative decline in overall smoking across the 2015–2017 and 2018–2020 time periods was 65% for non-Hispanic Black adolescents (1.65=2.82/1.71) and 42% for all others (1.42=5.91/4.17). Larger relative declines for non-Hispanic Black as compared to all other adolescents took place across all time periods for menthol, nonmenthol, and overall smoking (Table 2). This trend of smaller absolute declines but larger relative declines in smoking over time occurred because non-Hispanic Black adolescents began with relatively lower prevalence levels at all time periods and for all cigarette measures (Table 2).

Third, for all time periods prevalence of menthol use was significantly lower for non-Hispanic Black as compared to all other adolescents. In the most recent time period of 2018–2020 the 0.95% prevalence for non-Hispanic Black adolescents is about half of the 1.98% prevalence for all other adolescents.

Fourth, among the subgroup of past 30-day smokers the majority of non-Hispanic Black adolescents used menthol cigarettes and the majority of all other adolescents used nonmenthol cigarettes in more recent years. For example, 56% of non-Hispanic Black adolescents who had smoked in the past 30 days in 2018–2020 used menthol cigarettes (.56=.95/1.71), compared to 47% for all other adolescents (.47=1.98/4.17). This pattern holds true for the last two time periods of 2015–2017 and 2018–2020. In the first time period of 2012–2014 a majority of both non-Hispanic Black (68%) and all other adolescent smokers (51%) used menthol cigarettes.

Table 3 presents risk ratios from a multivariable model predicting cigarette prevalence as a function of demographics. These results formalize and support the patterns in the observed data presented in Figure 1 and Table 2. Non-Hispanic Black adolescents had the lowest levels of use for overall, menthol, and nonmenthol cigarettes, indicated for all three outcomes by a risk ratio less than one and the smallest risk ratio in the race/ethnicity block of measures. For example, the probability for mentholated cigarette use among non-Hispanic Black adolescents was about half of that (.55) for non-Hispanic white adolescents (the reference group). A decline in prevalence over time for all three cigarette measures is indicated in all models by a risk ratio for year of survey that was less than one and varied across the three outcomes from .85 to .88. These results control socioeconomic status, as indicated by a parent with a college degree, and age. Females had lower levels of use for nonmenthol cigarettes (risk ratio=.61), but not for menthol cigarettes.

Table 3:

Results from Regressions of Past 30-Day Smoking on Demographics, Year, and Grade: Relative Risk Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals in Parentheses

| ------------------ Type of Combustible Cigarette Smoked ------------------ | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Any | Mentholated | Nonmentholated | |

|

| |||

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.43** (0.36–0.50) | 0.55** (0.45–0.68) | 0.31** (0.24–0.40) |

| Hispanic | 0.62** (0.56–0.69) | 0.67** (0.58–0.76) | 0.58** (0.50–0.68) |

| Other | 0.80** (0.70–0.92) | 0.87 (0.73–1.05) | 0.75** (0.63–0.89) |

| Non-Hispanic White | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Female | 0.80** (0.75–0.86) | 1.04 (0.95–1.14) | 0.61** (0.55–0.68) |

| Parent has College Degree | 0.63** (0.59–0.67) | 0.57** (0.52–0.63) | 0.69** (0.62–0.77) |

| Year of Surveya | 0.86** (0.85–0.88) | 0.85** (0.82–0.87) | 0.88** (0.86–0.90) |

| School Grade | |||

| Grade 8 | 0.31** (0.28–0.35) | 0.34** (0.29–0.40) | 0.29** (0.25–0.34) |

| Grade 10 | 0.57** (0.52–0.63) | 0.65** (0.57–0.74) | 0.51** (0.45–0.58) |

| Grade 12 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Constant | 0.29** (0.27–0.32) | 0.13** (0.11–0.15) | 0.16** (0.14–0.19) |

Note: n=85,547

Year centered at 2012

p<.05

p<.01

Table 4 presents relative risk ratios from a multivariable model predicting menthol use among the subgroup of adolescents who had smoked in the past 30 days. Non-Hispanic Black adolescents were significantly more likely to use menthol cigarettes than were non-Hispanic white adolescents (risk ratio=1.31). Females were also more likely to use mentholated cigarettes (risk ratio = 1.30), and menthol/nonmenthol use differed little by grade.

Table 4:

Results from Regression of Menthol Use on Demographics, Year, and Grade among Past 30-Day Smokers: Relative Risks and 95% Confidence Interval in Parentheses

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1.31** (1.16–1.48) |

| Hispanic | 1.08 (0.99–1.18) |

| Other | 1.09 (0.97–1.21) |

| Non-Hispanic White | Reference |

| Female | 1.30** (1.21–1.39) |

| Parent has College Degree | 0.92* (0.86–0.99) |

| Year of Surveya | 0.98* (0.96–1.00) |

| School Grade | |

| Grade 8 | 1.02 (0.92–1.13) |

| Grade 10 | 1.11* (1.02–1.22) |

| Grade 12 | Reference |

| Constant | 0.44** (0.40–0.49) |

Note: n=4,918

Year centered at 2012

p<.05

p<.01

Sensitivity analyses examined whether the main findings for non-Hispanic Black and all other adolescents varied by survey year or school grade in the multivariable models (results not tabled). Year did not modify the results across non-Hispanic Black and all other adolescents in Tables 3 and 4, as tested with the addition of a multiplicative interaction term of year and the indicator variable for non-Hispanic Black (p>.05). Additional analyses of year did not support a curvilinear effect, as tested with the additional inclusion of a year-squared term (p>.05). Grade did not modify the race/ethnicity results in Tables 3 and 4, as tested with the addition of a multiplicative interaction term for grade of school and non-Hispanic Black (p>.05). In addition, Supplemental Table 1 and Supplemental Figure S1 present parallel findings to Table 2 and Figure 1, but restricted to 12th grade students only.

Discussion

This study set out to examine whether a decline continued in recent years for adolescent menthol and nonmenthol cigarette use and, if so, whether this decline differed for non-Hispanic Black adolescents. For adolescents who were other than non-Hispanic Black, both menthol and nonmenthol prevalence levels significantly declined from 2015–17 to 2018–20. For non-Hispanic Black adolescents, these prevalence levels trended downward but did not significantly decline. In part, this is because of a floor effect that left little room for these levels to fall further, with both menthol and nonmenthol use for these adolescents below 2% in 2015–17, and both below 1% in 2018–20.

The study findings identify important similarities and differences in menthol cigarette use compared to patterns in 2010, the date of the most recent published, national information on menthol use among black and nonblack adolescents. One key difference is this study’s finding that menthol cigarette use levels were significantly lower among non-Hispanic Black as compared to all other adolescents. Previously, before 2010 menthol use prevalence had been similar for both groups.8

One key similarity of this study with past findings is that among past 30-day smokers non-Hispanic Black adolescents are significantly more likely to use menthol than are all other adolescents. In sum, from 2012–2020 levels of menthol cigarette use were lower for non-Hispanic Black as compared to other adolescents, and among adolescents who had smoked in the past 30 days the pattern was flipped with menthol cigarettes in higher use among non-Hispanic Black as compared to all other adolescents.

These study results provide new information for two arguments central to the rationale for a potential menthol ban. The first argument is that a menthol ban may not be necessary because current policies to reduce cigarette use are working. These policies trace back to at least the Master Tobacco Settlement Agreement of 1998,31 which resulted in increased cigarette prices for consumers; restrictions on advertising, sponsorship, and lobbying activities targeting youth; the creation of a National Public Education Foundation to create nationwide media and education campaigns to reduce youth smoking and to conduct related research (since renamed the “Truth Initiative”); and substantial payments to the U.S. states to aid their implementation of additional, state-specific anti-smoking programs. More recent policy aimed at reducing adolescent cigarette prevalence includes “Tobacco to 21” legislation that prohibits sales of tobacco products to individuals under the age of 21.32

On the one hand, the study results point to continued success of these efforts, which have helped reduce menthol cigarette prevalence to less than 2% for all adolescents in the most recent time period of 2018–2020. To the extent that youth who do not start smoking in adolescence have historically had very low probability of starting in later life,22 this finding suggests that menthol cigarette use could fall to near-zero levels in the coming generations as today’s adolescents cohorts grow older.

On the other hand, these same results indicate that current efforts to reduce menthol cigarette initiation have approached near-maximum effectiveness. A reduction of the remaining one or two percent prevalence for adolescent menthol use will have only a small impact on menthol prevalence levels for the population as a whole. While today’s low levels of menthol cigarette use among adolescents potentially portend a future with near-zero menthol cigarette prevalence in the long term, it will take many generations for today’s adult menthol smokers to be replaced by today’s youth cohorts. The largest and most rapid potential gains to reduce menthol prevalence would be achieved by increased cessation among current adult users, assuming current tobacco control efforts continue and adolescent cigarette prevalence remains low.

This study also informs a second argument central to the rationale for the menthol ban, which is that such a ban could potentially reduce Black/nonblack disparities in menthol use. The study results show that levels of menthol cigarette use were significantly lower for non-Hispanic Black as compared to all other adolescents in all study time periods from 2012 to 2020. These results indicate that new initiation among youth is not the main driver of today’s Black/nonblack disparity in menthol use in the total population.8 Rather, the disparity represents in large part the persistence of smoking patterns among adults that likely formed many decades earlier, when they were adolescents, and/or lower levels of cessation among Black adults who started smoking decades earlier. Consequently, efforts with the most potential to reduce the current disparity in Black/nonblack menthol cigarette use should focus on menthol cessation initiatives and not just the disruption of current processes that recruit new smokers. Of particular importance are policies and initiatives aimed at addressing the relatively lower levels of smoking cessation among non-Hispanic Black adults as compared to non-Hispanic whites and Hispanics.33

An important area for future research and surveillance is potentially higher levels of smoking initiation after adolescence for non-Hispanic Black smokers as compared to other groups. This could lead to widening Black/nonblack disparities in menthol use over the life course. Smoking initiation post adolescence has typically received little attention because it has not been high,22,34 although analyses that have examined this issue indicate that Black smokers initiate smoking at slightly later ages than other groups.35,36 Recent analyses indicating that the age of smoking onset appears to be increasing for the U.S. population37 raises the possibility that any later menthol initiation for Black as compared to nonblack smokers may have a larger role in menthol disparities than it has had in the past. Consequently, evaluation of menthol policy should include attention to and monitoring of post-adolescence initiation processes that may be emerging.

Two limitations of this study are important to note. First, the MTF survey does not include questions on menthol-flavored cigars, which are also included in the FDA menthol ban. These products warrant separate consideration. Second, the survey does not include youth who have dropped out of high school by 12th grade, a group that typically has higher levels of tobacco use. The small size of this group, which according to the U.S. Census is about 6% of the U.S. 12th grade population,38 precludes it from having a large effect on the estimates in this study. It is expected that overall tobacco prevalence would be about one to two percentage points higher, based on other national surveys that do include high school dropouts.23

Conclusion

Continuing declines in adolescent menthol prevalence among both non-Hispanic Black and all other adolescents indicate that both menthol use and associated Black/nonblack disparities are steadily decreasing. However, these decreases will take many decades to complete through generational replacement alone. Efforts to accelerate menthol decreases will require new initiatives to increase cessation among adult menthol users. These initiatives could include a ban on menthol cigarettes that is structured so that it does not penalize the population it is intended to benefit, and/or the promotion of harm reduction policies proven to help adults quit smoking.

Supplementary Material

What this paper adds.

What is already known on this subject

Black as compared to nonblack adolescents have in the past had higher prevalence of menthol cigarette use in the U.S., although trends for these two groups since 2010 are largely unknown.

What this study adds

For both non-Hispanic black and nonblack adolescents prevalence of menthol cigarette use fell by more than 50% from 2012 to 2020.

Prevalence of adolescent menthol cigarette use is now similar and near zero for both non-Hispanic Black and nonblack adolescents, at 2% and 1%, respectively, in 2018–2020.

Near-zero incidence of menthol cigarette use in adolescence suggests that efforts to lower both menthol use and its associated Black/nonblack disparities among the overall U.S. population will require initiatives focused on increasing cessation among adults.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health (R01-DA-001411 to R. Miech, P.I.).

Contributor Information

Richard A. Miech, University of Michigan

Adam M. Leventhal, University of Southern California

Lloyd D. Johnston, University of Michigan

References

- 1.FDA Commits to Evidence-Based Actions Aimed at Saving Lives and Preventing Future Generations of Smokers; Efforts to Ban Menthol Cigarettes, Ban Flavored Cigars Build on Previous Flavor Ban and Mark Significant Steps to Reduce Addiction and Youth Experimentation, Improve Quitting, and Address Health Disparities [press release]. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Civil Liberties Union. ACLU Statement on FDA Menthol Cigarette Ban. 2021; https://www.aclu.org/press-releases/aclu-statement-fda-menthol-cigarette-ban.

- 3.Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee. Menthol Cigarettes and Public Health: Review of the Scientific Evidence and Recommendations. Rockville, MD: U.S. Departement of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yerger VB, McCandless PM. Menthol sensory qualities and smoking topography: a review of tobacco industry documents. Tobacco control. 2011;20(Suppl 2):ii37–ii43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaur G, Gaurav A, Lamb T, Perkins M, Muthumalage T, Rahman I. Current perspectives on characteristics, compositions, and toxicological effects of e-cigarettes containing tobacco and menthol/mint flavors. Frontiers in physiology. 2020;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rising J, Alexander L. Marketing of menthol cigarettes and consumer perceptions. Tobacco induced diseases. 2011;9(1):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.21 U.S.C. § 387g. 2009.

- 8.Giovino GA, Villanti AC, Mowery PD, et al. Differential trends in cigarette smoking in the USA: is menthol slowing progress? Tobacco control. 2015;24(1):28–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hersey JC, Nonnemaker JM, Homsi G. Menthol cigarettes contribute to the appeal and addiction potential of smoking for youth. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2010;12(suppl_2):S136–S146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mantey DS, Chido-Amajuoyi OG, Omega-Njemnobi O, Montgomery L. Cigarette smoking frequency, quantity, dependence, and quit intentions during adolescence: comparison of menthol and non-menthol smokers (National youth tobacco survey 2017–2020). Addictive Behaviors. 2021:106986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohn AM, Rose SW, D’Silva J, Villanti AC. Menthol smoking patterns and smoking perceptions among youth: findings from the population assessment of tobacco and health study. American journal of preventive medicine. 2019;56(4):e107–e116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wackowski O, Delnevo CD. Menthol cigarettes and indicators of tobacco dependence among adolescents. Addictive behaviors. 2007;32(9):1964–1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cwalina SN, Majmundar A, Unger JB, Barrington-Trimis JL, Pentz MA. Adolescent menthol cigarette use and risk of nicotine dependence: Findings from the national Population Assessment on Tobacco and Health (PATH) study. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2020;206:107715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mills SD, Hao Y, Ribisl KM, Wiesen CA, Hassmiller Lich K. The Relationship Between Menthol Cigarette Use, Smoking Cessation, and Relapse: Findings From Waves 1 to 4 of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2021;23(6):966–975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Cigarette Brand Preferences among Adolescents. Monitoring the Future Occasional Paper No 45. 1999. http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/occpapers/occ45.pdf.

- 16.Mills SD, Henriksen L, Golden SD, et al. Disparities in retail marketing for menthol cigarettes in the United States, 2015. Health & place. 2018;53:62–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delnevo CD, Ganz O, Goodwin RD. Banning Menthol Cigarettes: A Social Justice Issue Long Overdue. Oxford University Press US; 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Civil Liberties Union. Letter of Concern from over Two Dozen Justic, Law Enforcement, Legal, Drug Policy, and Directly Impacted Organizations. 2021; https://www.aclu.org/letter/coalition-letter-concern-hhs-menthol-cigarette-ban.

- 19.Robinson E Opinion: Why the Ban on Menthol Cigarettes Leaves a Sour Taste in My Mouth. Washington Post: 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Research Council. The Growth of Incarceration in the United States: Exploring Causes and Consequences. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miech R, Keyes KM, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD. The great decline in adolescent cigarette smoking since 2000: consequences for drug use among US adolescents. Tobacco Control. 2020;29(6):638–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking—50 years of progress: a report of the surgeon general. Atlanta, GA: Office of the Surgeon General; 2014: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK179276/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK179276.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miech RA, Johnston L, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, Patrick ME. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975–2020: Volume I, Secondary School Students. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schulenberg JE, Johnston L, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Miech RA, Patrick ME. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975–2019: Volume II, College Students and Adults Ages 19–60. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research; 2020: http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-vol2_2019.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sawdey MD, Chang JT, Cullen KA, et al. Trends and associations of menthol cigarette smoking among US middle and high school students—National Youth Tobacco Survey, 2011–2018. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2020;22(10):1726–1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Villanti AC, Mowery PD, Delnevo CD, Niaura RS, Abrams DB, Giovino GA. Changes in the prevalence and correlates of menthol cigarette use in the USA, 2004–2014. Tobacco control. 2016;25(Suppl 2):ii14–ii20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Monitoring the Future. Data from: Monitoring the Future (MTF) Public-Use Cross-Sectional Datasets, National Addiction & HIV Archive Program, November 11, 2021. 2021. https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/NAHDAP/series/35. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bachman JG, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Schulenberg JE, Miech RA. The Monitoring the Future Project after Four Decades: Design and Procedures. Occasional Paper #82. 2015. http://monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/occpapers/mtf-occ82.pdf. Accessed November 17, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Miech RA, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, Patrick ME. Demographic Subgroup Trends among Adolescents in the Use of Various Licit and Illicit Drugs, 1975–2019 (Monitoring the Future Occasional Paper #94). Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; 2020: http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/occpapers/mtf-occ94.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miech R, Leventhal A, Johnston L, O’Malley PM, Patrick ME, Barrington-Trimis J. Trends in Use and Perceptions of Nicotine Vaping Among US Youth From 2017 to 2020. JAMA pediatrics. 2020;175(2):185–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones WJ, Silvestri GA. The Master Settlement Agreement and its impact on tobacco use 10 years later: lessons for physicians about health policy making. Chest. 2010;137(3):692–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tobacco to 21 Act, 1258 (2019).

- 33.Chang SS. Re: Smoking cessation: A Report of the surgeon general. The Journal of urology. 2020;204(2):384–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Health UDo, Services H. Preventing tobacco use among youth and young adults: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease; …; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Escobedo LG, Anda RF, Smith PF, Remington PL, Mast EE. Sociodemographic characteristics of cigarette smoking initiation in the United States: implications for smoking prevention policy. Jama. 1990;264(12):1550–1555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Control CfD. Differences in the age of smoking initiation between blacks and whites--United States. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 1991;40(44):754–757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barrington-Trimis JL, Braymiller JL, Unger JB, et al. Trends in the age of cigarette smoking initiation among young adults in the US from 2002 to 2018. JAMA network open. 2020;3(10):e2019022–e2019022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Child Trends Databank. High School Dropout Rates. 2018. https://www.childtrends.org/indicators/high-school-dropout-rates.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.