Abstract

Previous studies that assessed risk factors for venous thromboembolism (VTE) in COVID-19 patients have shown inconsistent results. Our aim was to investigate VTE predictors by both logistic regression (LR) and machine learning (ML) approaches, due to their potential complementarity. This cohort study of a large Brazilian COVID-19 Registry included 4120 COVID-19 adult patients from 16 hospitals. Symptomatic VTE was confirmed by objective imaging. LR analysis, tree-based boosting, and bagging were used to investigate the association of variables upon hospital presentation with VTE. Among 4,120 patients (55.5% men, 39.3% critical patients), VTE was confirmed in 6.7%. In multivariate LR analysis, obesity (OR 1.50, 95% CI 1.11–2.02); being an ex-smoker (OR 1.44, 95% CI 1.03–2.01); surgery ≤ 90 days (OR 2.20, 95% CI 1.14–4.23); axillary temperature (OR 1.41, 95% CI 1.22–1.63); D-dimer ≥ 4 times above the upper limit of reference value (OR 2.16, 95% CI 1.26–3.67), lactate (OR 1.10, 95% CI 1.02–1.19), C-reactive protein levels (CRP, OR 1.09, 95% CI 1.01–1.18); and neutrophil count (OR 1.04, 95% CI 1.005–1.075) were independent predictors of VTE. Atrial fibrillation, peripheral oxygen saturation/inspired oxygen fraction (SF) ratio and prophylactic use of anticoagulants were protective. Temperature at admission, SF ratio, neutrophil count, D-dimer, CRP and lactate levels were also identified as predictors by ML methods. By using ML and LR analyses, we showed that D-dimer, axillary temperature, neutrophil count, CRP and lactate levels are risk factors for VTE in COVID-19 patients.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11739-022-03002-z.

Keywords: COVID-19, Pulmonary embolism, Deep vein thrombosis, Risk factors, Thromboprophylaxis

Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is an underdiagnosed disease, with an estimated incidence of 10 million cases per year worldwide, and more than half a million deaths [1]. However, its incidence varies widely, depending on the prevalence of genetic and acquired risk factors, such as age, sex, comorbidities, acute illnesses and immobilization in a population [2]. As it leads to high morbidity and mortality [3], early recognition and prompt treatment are essential [4].

Coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) can trigger an intense endotheliitis and hypercoagulability state, which can lead to an increased thromboembolic risk [5–8]. Several reports have described a high incidence of VTE in patients hospitalized with COVID-19, ranging from 20 to 60% in critically ill patients admitted to intensive care units (ICU) and 5–20% in those hospitalized in wards [9–11]. The incidence of VTE remained high even when thromboprophylaxis was used [12, 13]. In those patients, pulmonary embolism (PE) represents a major diagnostic challenge, as its symptoms and signs overlap with the ones of the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). The occurrence of VTE in patients with COVID-19 has been shown to increase mortality [14–17] and thromboprophylaxis appears to reduce mortality in those patients [18]. Therefore, there has been a major worldwide effort to identify predictors of VTE in hospitalized COVID-19 patients, as a path to promote prevention, early diagnosis and treatment [9, 10, 19–21].

The main available scores for predicting VTE in medical patients do not seem to perform well in patients with COVID-19 [22, 23]. Furthermore, the score originally developed to predict VTE in patients hospitalized for COVID-19 (CHOD) still needs to be validated in larger populations to confirm its accuracy [23]. In addition, there is still a major inconsistency among the potential predictors of VTE identified by previous studies [24]. In this context, machine learning (ML) techniques, which can identify complex (non-linear) correlations among potential predictors, may be useful tools [25]. However, to the best of our knowledge, the use of ML as an approach to assess VTE predictors in COVID-19 patients has not yet been reported. Thus, this study aims at identifying predictors of VTE in a large cohort of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in Brazil, using traditional statistical methods as well as ML techniques’ approaches. We also reported the incidence of thromboembolic complications in COVID-19 and their prognostic impact.

Methods

Study design and settings

This cohort is a substudy of the Brazilian COVID-19 Registry, conducted in 37 Brazilian hospitals, described in detail elsewhere [26]. Due to previous evidence of the importance of D-dimer as a predictor of VTE in COVID-9 patients upon hospital admission [5, 10, 11, 14, 15, 19, 21, 27, 28], we restricted the present analysis to the 16 hospitals in which D-dimer was routinely performed at hospital admission (less than 35% missing values). The hospitals were located in three Brazilian states (Minas Gerais, Santa Catarina and Rio Grande do Sul).

Study subjects

Consecutive adult patients (≥ 18 years) with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 [29], admitted to participating hospitals between March and September 2020 were enrolled. Patients who were transferred from the participating hospital to another hospital (not part of the cohort) within 30 days and did not have VTE within that period were not included. We also excluded patients who were admitted for other reasons and developed COVID-19 symptoms during their stay (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of Brazilian patients included in the study. VTE venous thromboembolism

Data collection and quality assessment

Demographic information, clinical characteristics, laboratory and outcome data were collected by trained hospital staff or undergraduate medical or nurse interns from medical records, using a validated case report form (CRF) on Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) [30, 31].

A detailed data management plan (DMP) was developed and provided to all participating centers, and undergoing online training was mandatory prior to data collection. Comprehensive data quality checks were undertaken, to ensure high quality [32]. In case the patient was transferred from one participant hospital to another, information about the patient was merged and considered as a single entry.

All covariates in the present study were assessed upon hospital admission, except for in-hospital anticoagulation. During hospitalization, prophylactic anticoagulation was considered as the use of low-molecular-weight heparin, such as enoxaparin 40 mg once a day, unfractionated heparin 5,000 international units, twice or three times a day, or fondaparinux at a dose of 2.5 mg a day.

Therapeutic anticoagulation, on the other hand, referred to the use of enoxaparin 1 mg/kg, twice a day (or once a day, if estimated glomerular filtration rate < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2), unfractionated heparin with titrated dose to 1.5–2.5 times the baseline of activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) when compared to control or fondaparinux at doses of 5 mg, 7.5 mg or 10 mg once a day, depending on the patient’s weight.

Some centers used an intermediate dose of heparin for routine thromboprophylaxis, since this was an available approach at the beginning of the pandemic. Others have used this dose for patients considered to be at high risk for VTE, as defined by the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) guideline [33]. The intensity of the intermediate dose varied according to centers, and was either enoxaparin 40 mg twice-daily, enoxaparin 0.5 mg/kg twice-daily or enoxaparin 1 mg/kg once daily (in the absence of severe renal dysfunction). Some institutions, on the other hand, used full-dose anticoagulation for prophylaxis, that is treatment dose with the intention of prevention, in the absence of suspected or confirmed VTE.

Outcomes

Symptomatic VTE was diagnosed based on clinical manifestations confirmed by objective imaging such as compression ultrasonography (CUS) with Doppler or bedside compression ultrasonography for deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and computed tomography pulmonary angiography or ventilation-perfusion scan, for PE. If hemodynamic instability made it impossible to perform the previous tests in patients suspected of PE, the presumptive diagnosis was performed by abnormalities suggestive of acute right ventricular overload on echocardiogram or at the point-of-care multi-organ ultrasonography [34]. Catheter-associated thrombosis or visceral thrombosis were not considered as outcomes.

We also assessed mortality, need for invasive mechanical ventilation, renal replacement therapy and bleeding in patients with confirmed VTE. Bleeding was classified as: (1) severe if: fatal, critical location (intracranial, spinal, pericardial, articular, retroperitoneal or intramuscular with compartment syndrome), shock, permanent disability, and/or fall in hemoglobin level ≥ 2 g/dL (1.24 mmol/L) or leading to transfusion of two or more units of whole blood or red cells, (2) not severe, but clinically relevant when it did not meet the criteria for severe bleeding, but required medical intervention, temporary interruption of treatment or caused pain. In addition, (3) non-serious if none of the previous definitions.

D-dimer assessment

Assessment of D-dimer levels was not performed with the same method among the 16 centers (Table S1). To allow for a unified analysis, we presented D-dimer levels in relative values, that is, the number of times the D-dimer was increased in relation to the upper limit of the reference value of the test used. Then, we stratified it into five groups, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of cohort of Brazilian patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19

| Characteristics | Confirmed VTE (n = 2741) |

Non VTE (n = 38461) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency (%) or median (IQR) | Non-missing cases (%) | Frequency (%) or median (IQR) | Non-missing cases (%) | |

| Age (years) | 63.0 (51.0, 72.0) | 274 (100%) | 60.0 (48.0, 72.0) | 3846 (100%) |

| Sex at birth | 274 (100%) | 3845 (100%) | ||

| Men | 150 (54.7%) | 2134 (55.5%) | ||

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension | 151 (55.1%) | 274 (100%) | 2092 (54.4%) | 3846 (100%) |

| Coronary artery disease | 16 (5.8%) | 274 (100%) | 192 (5.0%) | 3846 (100%) |

| Heart failure | 15 (5.5%) | 274 (100%) | 242 (6.3%) | 3846 (100%) |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 3 (1.1%) | 274 (100%) | 137 (3.6%) | 3846 (100%) |

| Stroke | 9 (3.3%) | 274 (100%) | 141 (3.7%) | 3846 (100%) |

| Asthma | 19 (6.9%) | 274 (100%) | 272 (7.1%) | 3846 (100%) |

| COPD | 24 (8.8%) | 274 (100%) | 233 (6.1%) | 3846 (100%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 87 (31.8%) | 274 (100%) | 1,084 (28.2%) | 3846 (100%) |

| Obesitya | 68 (24.8%) | 274 (100%) | 698 (18.1%) | 3846 (100%) |

| Cirrhosis | 2 (0.7%) | 274 (100%) | 21 (0.5%) | 3846 (100%) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 8 (2.9%) | 274 (100%) | 204 (5.3%) | 3846 (100%) |

| Rheumatological disease | 0 (0.0%) | 274 (100%) | 3 (0.1%) | 3846 (100%) |

| HIV infection | 4 (1.5%) | 274 (100%) | 42 (1.1%) | 3846 (100%) |

| Cancer | 14 (5.1%) | 274 (100%) | 170 (4.4%) | 3846 (100%) |

| Surgery in previous 90 days | 14 (5.1%) | 274 (100%) | 87 (2.3%) | 3841 (100%) |

| Previous transplant | 1 (0.4%) | 274 (100%) | 17 (0.4%) | 3846 (100%) |

| Medications on admission | ||||

| NSAIDs | 9 (3.3%) | 274 (100%) | 135 (3.5%) | 3846 (100%) |

| Potassium sparing diuretic | 9 (3.3%) | 274 (100%) | 106 (2.8%) | 3846 (100%) |

| Thiazide diuretic | 32 (11.7%) | 274 (100%) | 496 (12.9%) | 3846 (100%) |

| Hypoglycemic (non-insulin) | 55 (20.1%) | 274 (100%) | 693 (18.0%) | 3846 (100%) |

| Immunosuppressant | 3 (1.1%) | 274 (100%) | 21 (0.5%) | 3846 (100%) |

| ACE or BRA inhibitor | 102 (37.2%) | 274 (100%) | 1313 (34.1%) | 3846 (100%) |

| Insulin | 19 (6.9%) | 274 (100%) | 270 (7.0%) | 3846 (100%) |

| Statin | 53 (19.3%) | 274 (100%) | 714 (18.6%) | 3846 (100%) |

| Amiodarone | 0 (0.0%) | 274 (100%) | 48 (1.2%) | 3846 (100%) |

| Oral anticoagulant | 13 (4.7%) | 274 (100%) | 290 (7.5%) | 3846 (100%) |

| Beta blocker | 38 (13.9%) | 274 (100%) | 694 (18.0%) | 3846 (100%) |

| Calcium channel blocker | 30 (10.9%) | 274 (100%) | 469 (12.2%) | 3846 (100%) |

| Inhaled corticosteroid | 6 (2.2%) | 274 (100%) | 127 (3.3%) | 3846 (100%) |

| Oral corticosteroids | 7 (2.6%) | 274 (100%) | 78 (2.0%) | 3846 (100%) |

| Digitalic | 0 (0.0%) | 274 (100%) | 20 (0.5%) | 3846 (100%) |

| Loop diuretic | 16 (5.8%) | 274 (100%) | 278 (7.2%) | 3846 (100%) |

| Clinical characteristics at admission | ||||

| Temperature (°C) | 36.6 (36.1, 37.4) | 169 (62%) | 36.5 (36.0, 37.2) | 2617 (68%) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 261 (95%) | 3687 (96%) | ||

| > 90 mmHg without amine | 227 (87.0%) | 3445 (93.4%) | ||

| < 90 mmHg without amine | 9 (3.4%) | 45 (1.2%) | ||

| Any value, but with amine | 25 (9.6%) | 197 (5.3%) | ||

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 261 (95%) | 3685 (96%) | ||

| > 60 mmHg without amine | 207 (79.3%) | 3,010 (81.7%) | ||

| < 60 mmHg without amine | 29 (11.1%) | 478 (13.0%) | ||

| Any value, but with amine | 25 (9.6%) | 197 (5.3%) | ||

| Heart rate (bpm) | 90.0 (80.0, 103.0) | 264 (96%) | 88.0 (78.0, 100.0) | 3693 (96%) |

| Respiratory rate (bpm) | 21 (18, 25) | 222 (81%) | 20 (18, 24) | 3153 (82%) |

| Glasgow coma score < 15 | 44 (16.1%) | 274 (100%) | 504 (13.1%) | 3846 (100%) |

| Laboratory tests | ||||

| D-dimer/maximum reference value | 239 (87%) | 3069 (80%) | ||

| ≤ 1 x | 30 (12.6%) | 684 (22.3%) | ||

| 1–1.9 x | 54 (22.6%) | 857 (27.9%) | ||

| 2–3.9 x | 36 (15.1%) | 539 (17.6%) | ||

| 4–9.9 x | 37 (15.5%) | 267 (8.7%) | ||

| ≥ 10 x | 82 (34.3%) | 722 (23.5%) | ||

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 94.3 (54.2, 183.7) | 243 (89%) | 72.8 (33.4, 130.1) | 3460 (90%) |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 13.1 (11.8, 14.2) | 269 (98%) | 13.4 (12.2, 14.5) | 3777 (98%) |

| Leukocytes count (cells/mm3) | 8.8 (6.0, 11.9) | 269 (98%) | 6.9 (5.1, 9.4) | 3777 (98%) |

| Neutrophils count (cells/mm3) | 6928.0 (4,310.0, 9205.0) | 269 (98%) | 4946.1 (3374.0, 7452.0) | 3658 (95%) |

| Lymphocytes count (cells/mm3) | 1000.0 (684.5, 1355.0) | 267 (97%) | 1058.0 (730.0, 1478.5) | 3656 (95%) |

| Neutrophils-to-lymphocytes ratio | 6.2 (4.0, 10.6) | 267 (97%) | 4.7 (2.8, 8.0) | 3654 (95%) |

| Platelet count (109/L) | 214.0 (162.0, 282.2) | 268 (98%) | 197.0 (155.0, 256.0) | 3742 (97%) |

| TGP/ALT (U/L) | 35.5 (23.0, 56.0) | 207 (76%) | 34.9 (22.0, 56.0) | 2791 (73%) |

| TGO/AST (U/L) | 43.0 (32.0, 63.8) | 205 (75%) | 40.0 (28.9, 59.6) | 2806 (73%) |

| Arterial pO2 (mmHg) | 76.0 (63.0, 100.0) | 237 (86%) | 76.0 (64.0, 97.8) | 3186 (83%) |

| Arterial pCO2 mmHg | 35.7 (32.0, 40.0) | 237 (86%) | 35.0 (31.9, 39.0) | 3196 (83%) |

| SF ratio | 350.0 (120.0, 441.7) | 266 (97%) | 428.6 (328.6, 452.4) | 3755 (98%) |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.9 (0.7, 1.2) | 264 (96%) | 0.9 (0.8, 1.2) | 3683 (96%) |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 138.0 (135.0, 140.1) | 260 (95%) | 138.0 (135.0, 140.0) | 3507 (91%) |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 274 (100%) | 3842 (100%) | ||

| Lactate dehydrogenase (U/L) | 421.0 (336.1, 629.0) | 177 (65%) | 373.0 (272.0, 511.0) | 2443 (64%) |

| INR | 1.1 (1.0, 1.2) | 210 (77%) | 1.1 (1.0, 1.2) | 2410 (63%) |

| Lifestyle habits | ||||

| Illicit drugs | 1 (0.4%) | 274 (100%) | 32 (0.8%) | 3846 (100%) |

| Alcoholism | 9 (3.3%) | 274 (100%) | 155 (4.0%) | 3846 (100%) |

| Current smoking | 8 (2.9%) | 274 (100%) | 144 (3.7%) | 3846 (100%) |

| Ex-smoker | 53 (19.3%) | 274 (100%) | 591 (15.4%) | 3846 (100%) |

| Anticoagulant during hospitalizationc | ||||

| Prophylactic use of anticoagulantb | 166 (60.6%) | 274 (100%) | 3081 (80.1%) | 3846 (100%) |

| Full-dose anticoagulation for prophylaxis | 0 (0.0%) | 274 (100%) | 498 (12.9%) | 3846 (100%) |

| Therapeutic use of anticoagulant | 204 (74.5%) | 274 (100%) | 612 (15.9%) | 3846 (100%) |

| Admission to intensive care | 195 (71.2%) | 274 (100% | 1426 (37.1%) | 3846 (100%) |

ACEi angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, ARB angiotensin receptor blocker, bpm beats per minute, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, FiO2 fraction of inspired oxygen, HIV human immunodeficiency virus, INR international normalized ratio, IQR Interquartile range, NSAIDs nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, O2 saturation (%) peripheral oxygen saturation, PaO2 partial pressure of oxygen, PaCO2 partial pressure of carbon dioxide, SF ratio peripheral O2 saturation/FiO2, TGO/AST aspartate aminotransferase, TGP/ALT alanine aminotransferase, VTE venous thromboembolism

aBMI > 30 kg/m.2

bOf these, 29 patients (0.7% in total) used an intermediate dose of anticoagulation

cThe rate of anticoagulant use, summing the three strategies (usual prophylactic use, full dose of anticoagulation for prophylaxis and therapeutic use), exceeds 100%, due to the fact that the same patient transitioned from prophylactic dose to full dose of anticoagulation, and vice versa, in the same hospitalization

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using R software (version 4.0.2). Descriptive analyses were used to summarize all the variables: continuous variables were summarized using medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) and categorical variables with counts and percentages.

Logistic regression (LR) was used to investigate the associations (odds ratio [OR], 95% confidence interval [95% CI]) of variables at hospital presentation as potential risk factors for VTE (demographic characteristics, underlying medical conditions, home medications, clinical characteristics and laboratory analysis at hospital presentation). Bivariate analysis considered the use of prophylactic anticoagulants at any dosage. For the multivariate model, variables with p < 0.15 in bivariate analysis were included and model selection was based on Akaike information criterion (AIC). Before multivariable analysis, missing values were handled using multiple imputation with chained equations, under the missing at random assumption (mice R package, 10 sets of imputations).

Machine learning approaches

We evaluated tree-based boosting (such as extreme gradient boosting machines and light gradient boosting machines) and bagging (essentially random forests) ML algorithms, combined with Shapley Additive ExPlanation (SHAP) values [35] to obtain feature importance and impact of variables on predictions over the same imputed data used with the statistical tools. All algorithms were trained in a tenfold cross-validation procedure, using a grid search algorithm for hyperparameter tuning. Our particular choice of these tree-based algorithms is due to their higher interpretability [36], especially when compared with neural or deep learning solutions. In addition, the use of SHAP values allows us to learn and infer more interesting patterns, such as non-linear correlations, as well as interpreting individual model predictions.

Patient and public involvement

Due to the fact that this was an urgent public health research study in response to a Public Health Emergency of international concern, patients or the public were not involved in the design, conduct, interpretation or presentation of results of this research.

Results

Patients

Among 4120 consecutive patients included, the median age was 61 years (IQR 48–72); 55.5% were male; 39.3% critical patients and 60.1% hospitalized in the ward. The most common comorbidities were hypertension, diabetes mellitus and obesity (Table 1). Most patients (91%) received thromboprophylaxis, either at the usual prophylactic (low) dose (78.1%), intermediate (0.7%) or even full dose (12.1%), during hospitalization (Table 1).

Venous thromboembolism was confirmed in 274 (6.7%) patients of whom 74.8% had PE, 19.7% DVT and 5.4% had both conditions.

Among patients with atrial fibrillation (AF), although home anticoagulant use was higher among patients with CHA2DS2-VASc ≥ 2 when compared to those with CHA2DS2-VASc < 2, the VTE event rate in patients with AF was too small to show a difference when compared to the CHA2DS2-VASc < 2 group (Table S2).

Risk factors associated with venous thromboembolism

Table S3 shows the results of the bivariate analysis. In multivariable logistic regression analysis (Table 2), the following variables were shown to be independent predictors of VTE: obesity (OR 1.5, 95% CI 1.11–2.02, p < 0.01), being an ex-smoker (OR 1.44, 95% CI 1.03–2.01, p = 0.03), surgery in the past 90 days (OR 2.2, 95% CI 1.14–4.23, p < 0.01), temperature on admission (OR 1.41, 95% CI 1.22–1.63, p < 0.01), D-dimer equal or above four times the reference value (OR 2.16, 95% CI 1.26–3.67, p < 0.01), lactate (OR 1.10, 95% CI 1.02–1.19, p = 0.01) and C-reactive protein values (OR 1.09, 95% CI 1.01–1.18, p = 0.01), neutrophil count (OR 1.04, 95% CI 1.01–1.08, p = 0.02). Among the protective factors, there were atrial fibrillation (AF)/flutter (OR 0.30, 95% CI 0.09–0.99, p = 0.04), SF ratio (OR 0.997, 95% CI 0.996–0.998), p < 0.01) and prophylactic anticoagulation (OR 0.20, 95% CI 0.15–0.26, p < 0.01). Patients with confirmed VTE had higher mortality (28.4% vs 18.5%, p < 0.001), required mechanical ventilation (58.4% vs 26.4%, p < 0.001) and renal replacement therapy (21.5% vs 9.7%, p < 0.001) more frequently, and bleed more (5.8% vs 1.5%, p < 0.001), when compared to the group without confirmed VTE (Table 3).

Table 2.

Multivariable analysis for prediction of symptomatic venous thromboembolism, based on variables available upon hospital presentation

| Variable | Frequency (%) or median (IQR) | Confirmed VTE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | p value | ||

| Obesitya | 766 (18.6%) | 1.50 (1.11–2.02) | < 0.01 |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 140 (3.4%) | 0.30 (0.09–0.99) | 0.04 |

| Previous use of beta blocker | 732 (17.8%) | 0.73 (0.50–1.07) | 0.11 |

| Ex-smoker | 644 (15.6%) | 1.44 (1.03–2.01) | 0.03 |

| Surgery in previous 90 days | 101 (2.5%) | 2.20 (1.14–4.23) | < 0.01 |

| Temperature (°C)bc | 36.5 (36.0, 37.2) | 1.41 (1.22–1.63) | < 0.01 |

| SF ratiobd | 428.6 (317.9, 452.4) | 0.87 (0.83–0.93) | < 0.01 |

| D-dimer/maximum reference valueb | |||

| 1–1.9x | 911 (22.1%) | 1.32 (0.83–2.09) | 0.239 |

| 2–3.9x | 575 (13.9%) | 1.19 (0.72–1.96) | 0.486 |

| 4–9.9x | 304 (7.3%) | 2.16 (1.26–3.67) | < 0.01 |

| ≥ 10x | 804 (19.5%) | 1.89 (1.18–3.01) | < 0.01 |

| Lactatebe | 1.4 (1.1, 1.9) | 1.10 (1.02–1.19) | 0.01 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L)bd | 74.4 (34.0, 134.1) | 1.09 (1.01–1.18) | 0.01 |

| Neutrophils’ countbf | 5,045.0 (3,400.0, 7,613.8) | 1.04 (1.005–1.075) | 0.02 |

| Prophylactic use of anticoagulant | 3,247 (78.8%) | 0.20 (0.15–0.26) | < 0.01 |

| Full-dose anticoagulation for prophylaxis | 498 (12.1%) | NA | 0.95 |

IQR Interquartile range, SF ratio oxygen saturation/inspired oxygen fraction

aBMI (Body mass index) > 30 kg/m2

bData regarding hospital presentation

cIncrement of 1.0 ºC

dIncrement of 50 units

eIncrement of 1 unit

fIncrement of 1000 units

Table 3.

Outcomes in patients with and without confirmed venous thromboembolism

| Outcomes | Diagnosis of VTE | p value2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No1 (n = 3846) |

Yes1 (n = 274) |

||

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 1016 (26.4%) | 160 (58.4%) | < 0.001 |

| Need for renal replacement therapy | 373 (9.7%) | 59 (21.5%) | < 0.001 |

| Death | 710 (18.5%) | 77 (28.4%) | < 0.001 |

| Bleeding | 56 (1.5%) | 16 (5.8%) | < 0.001 |

| Severity of bleeding | 0.311 | ||

| Severe | 26 (46.4%) | 4 (25.0%) | |

| Not severe, but clinically relevant | 18 (32.1%) | 8 (50.0%) | |

| Not severe | 12 (21.4%) | 4 (25.0%) | |

1Statistics presented: n (%)

2Statistical tests performed: Chi-square test of independence; Fisher’s exact test

Machine learning

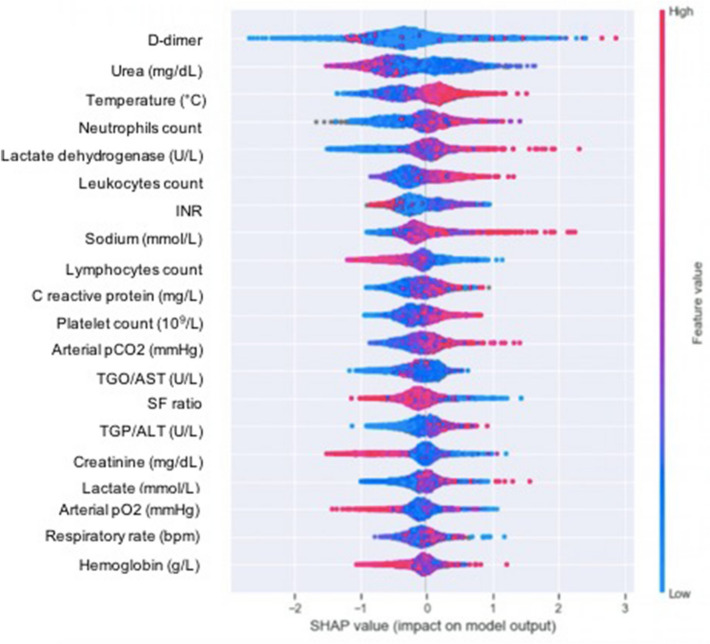

Figure 2 shows the impact of variables on final prediction of VTE by SHAP values. D-dimer value was the most important feature in predicting VTE, followed by urea, axillary temperature and neutrophils' count. In addition to the D-dimer, axillary temperature and neutrophils count, three other variables identified by the ML methods coincided with those shown by the logistic regression and maintained the direction of the correlation: high C-reactive protein and lactate values increased the risk of VTE (red tone of the graph shifted to the right from point 0), while high SF ratio was associated with lower incidence of the outcome (red tone of the graph left shifted from point 0).

Fig. 2.

Impact of variables on the prediction of venous thromboembolism by machine learning. Variables closer to the top are those with the highest correlation with the outcome. Red means probability of the outcome being predicted while blue means a smaller probability. Values to the right mean higher input values of the variable, while values to the left mean otherwise. FiO2: fraction of inspired oxygen; INR: international normalized ratio; PCO2: arterial carbon dioxide partial pressure; PaO2: arterial oxygen partial pressure; SF ratio: peripheral oxygen saturation/FiO2, TGO/AST: aspartate aminotransferase; TGP/ALT: alanine aminotransferase

The figure also shows that for hemoglobin, values either too high or too low yield higher risk. For urea, creatinine and lymphocytes count, low values yield higher risk.

Machine learning vs traditional statistics

Figure 3 shows the comparison of predictors from LR and ML analyses. There is some intersection between the most important variables identified by the regression analysis and the boosting + SHAP values’ analysis. This intersection is, in particular, expected for the important factors, such as D-dimer, but it is also expected that we find more variables in the boosting algorithm’s feature importance, seeing as factors like collinearity do not hinder its performance, meaning that collinear variables are still used, to the degree that they encode some level of new information. In the analysis by logistic regression, this collinearity can negatively impact the results, being sometimes necessary to remove some variables. Furthermore, variables like Hemoglobin, in which either values too high and too low increase risk, can only be safely captured as important by the SHAP values’ approach, seeing as the regression analysis cannot capture non-linear approaches without explicit modeling.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of VTE risk predictors identified by logistic regression analysis (A) and machine Learning approaches (B). SF ratio oxygen saturation/inspired oxygen fraction, INR international normalized ratio, PCO2 arterial carbon dioxide partial pressure, PaO2 arterial oxygen partial pressure, TGO/AST aspartate aminotransferase, TGP/ALT alanine aminotransferase

Discussion

This multicenter study, one of the largest individual studies on risk factors of VTE in COVID-19 patients, observed that among the variables identified by the multivariate logistic regression analysis as predictive of VTE, six were confirmed by ML analysis, which include D-dimer levels, axillary temperature, neutrophil count, C-reactive protein and lactate levels and SF ratio. The incidence rate of VTE was 6.7%, confirming the increased thrombotic risk in COVID-19 patients. Mortality, need for mechanical ventilation and renal replacement therapy were higher in patients who developed VTE in comparison with the patients who did not, highlighting the severity of this complication in the prognosis of COVID-19.

D-dimer was one of the main predictors identified in both methods. It has been shown to be an important predictor of VTE in COVID-19 patients [10, 24, 28]. A recent meta-analysis suggested that the traditional D-dimer cutoff value (< 500 µg/L) used to exclude VTE in the general population seems applicable also to patients with COVID-19 [9]. However, as a VTE risk predictor, there are still uncertainties about which levels would, in fact, predict a VTE. In addition, the interpretation of D-dimer results is challenging due to the great diversity of methods, cutoff values, measurement units and whether presented as D-dimer units (DDU) or fibrinogen equivalent units (FEU), which are approximately twice those of DDU. The majority of studies which assessed D-dimer in COVID-19 patients did not make these points about the test clear, impairing the interpretability of the results [37]. Therefore, the analysis of D-dimer in relative values, compared to the reference value, seems to be more proper. A Chinese study indicated that the most significant association with VTE occurred when D-dimer increments ≥ 1.5 fold [38], while in the present analysis this association was observed when it was four or more times above the reference value, the same as observed in a North American retrospective cohort [28]. These data suggest that this cutoff value may be a predictor of VTE in hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

Our study showed other independent risk factors as predictors of VTE in COVID-19 patients, which were not previously identified in other studies [24]. Although some authors have questioned the role of traditional risk factors of venous thromboembolic disease as predictors of VTE among COVID-19 patients [21, 39], our study reassures recent surgery and obesity as independent predictors. Surgery has been consistently recognized as a major transient risk factor for VTE, among the general population [40]. It was quite unexpected that such association was not observed among COVID-19 patients in previous studies. We hypothesized that this may be due to the lack of power or to lack of collection of information on recent surgery in the previous studies. Obesity has been shown to be associated with severe disease and increased risk of mortality among COVID-19 patients [14, 15, 21, 38, 41], its association with VTE involves venous stasis, decreased mobility, and coagulation abnormalities [42–47]. Increased plasma levels of fibrinogen, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, factors VII and VIII, von Willebrand factor, increased platelet activation and higher circulating procoagulant microparticles as well as endothelial dysfunction have been reported [42–47].

Smoking has not been observed to be a predictor among patients with COVID-19 in the more recent individual studies [24], as well as does not appear to be a predisposing factor for hospitalization for COVID-19 [48]. In our study, previous smoking was an independent predictor of VTE, but current smoking was not. This may be due to underreporting of current smoking, as the rate was less than 4%.

Unlike previous reports, our study identified axillary temperature upon hospital presentation as an independent predictor of VTE risk, which may be the consequence of contraction of volume secondary to insensitive losses, contributing to the venous stasis of the Virchow’s triad [7].

The present analysis identified inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein and neutrophil count to be independently associated with the occurrence of VTE, in agreement with other reports [21, 24]. However, unlike other publications, we also found that lactate level was an independent predictor of VTE. Lactate level is a marker of disease severity and corroborates previous evidence that indicates an increased thrombotic risk in patients hospitalized with severe infections, such as sepsis and septic shock [49].

Hospitalization due to acute infections has shown to be a strong trigger for VTE, independent of immobilization [50, 51]. In hospitalized patients with COVID-19, the cytokine storm, excessive inflammation, and the consequent endothelial injury, inflammatory endotheliitis, besides hypoxia and disseminated intravascular coagulation are believed to play a key role in this process [6, 7, 52].

We found that atrial fibrillation and flutter, SF ratio (peripheral oxygen saturation over inspired oxygen fraction) and prophylactic use of anticoagulant were protective factors for VTE. The highest levels of SF ratio (peripheral oxygen saturation over inspired oxygen fraction) likely reflect a diminished severity of the inflammatory response. In fact, SF ratio was an important predictor of mortality in the ABC2-SPH score, derived from this same cohort [53]. This variable has been validated as a surrogate for the PaO2/FiO2 ratio to assess the severity of hypoxemia, in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome [54].

Our findings confirm those of a previous study which showed that pre-existing cardiovascular diseases are not associated with a higher VTE risk, in COVID-19 patients [21]. However, the presence of atrial fibrillation or flutter was shown to be a protective factor of VTE. This is likely to be a proxy of anticoagulant use, since 60% of these patients in our study were using anticoagulants prior to admission and the vast majority of these patients had oral medication changed to therapeutic heparin during hospitalization. It is unclear why only 60% of patients with AF were reported to be anticoagulated at home. The medical records did not make it clear whether the reason was an increased risk of bleeding. It is possible a problem of underreporting.

Despite this possible reduction in the rate of VTE with full anticoagulation, it does not mean that full-dose anticoagulation should be routinely administered to patients with COVID-19. A recent meta-analysis has shown that the indiscriminate use of a full dose of anticoagulant significantly increased the incidence of bleeding and mortality [55]. On the other hand, a randomized multiplatform trial indicated a potential benefit of routine therapeutic anticoagulation for patients hospitalized for non-critical COVID-19, in relation to days free of cardiovascular or respiratory organ support [56]. Another randomized study not included in the meta-analysis [55] showed that the empirical use of anticoagulant at a therapeutic dose reduced the occurrence of thromboembolic events in patients hospitalized in a ward with D-dimer ≥ 4 times the reference value [57], the same cutoff we observed as a predictor of VTE in the present study. More studies are still needed to better guide when and for whom to use the full dose of anticoagulant as a prophylactic strategy. However, our study corroborates the most recent evidence that a possible cutoff value of the D-dimer four times the upper limit of reference may be a guide for a more aggressive anticoagulation approach. As expected, in our study, the use of anticoagulants at a prophylactic dose reduced the risk of VTE in COVID-19 patients, corroborating data already available [21].

In the present study, ML approaches detected other fourteen potential predictors of VTE in addition to the six variables identified by logistic regression analysis. One of the main advantages in traditional methods, such as regressions, lies in how simple they are and in how just analyzing the model (i.e., looking at the coefficients, for instance) can properly explain what was learned in the model [35]. Despite that, many of such techniques fall short in the sort of patterns they can learn, mostly remaining restricted to linear associations among variables, manually crafted non-linearities and other simpler variable associations. In addition, LR’s performance usually deteriorates in presence of collinearity, which may be especially problematic when the variables are not perfectly collinear and discarding some of them may result in useful information loss. Furthermore, missing values have to be replaced with some form of artificial values, which may also generate problems. Machine-learning approaches have the ability of dealing with collinearity and redundancy, which may have occurred among some variables, as well as the ability to assess non-linear correlations.

Among the chief advantages of using ML models is their learning capacities, enabling them to capture much more complex patterns, sometimes even ascending into semantic and abstract levels, albeit requiring substantially more data points in exchange. In the particular case of decision trees, random forests and gradient boosting machines, collinearity is not a problem, which means no potentially predictive information has to be discarded, and missing values do not require any form of filling [58, 59]. However, there is also an increased risk of identifying spurious (non-significant) associations, mainly due to issues of overfitting [60].

In multivariate logistic regression analysis, we have not observed an association with some variables which were significant in the aforementioned meta-analysis [24], including white blood cell count, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and prolonged prothrombin time, but these variables were observed as predictors in the ML model.

The rate of VTE in our study was at the lowest limit of that usually described in the literature [10]. Several factors may have influenced this finding. Some of the previous studies performed routine imaging exams or even excluded patients who had not performed imaging exams for VTE while asymptomatic for the disease, which may have overestimated the rate of thromboembolic events [21]. In addition, the first cases of infection in Brazil only occurred at the end of February 2020, while the first wave of the disease only happened between April and May of that same year. At that time, the thrombogenic potential of the disease was already known and the routine use of thromboprophylaxis for patients hospitalized for COVID-19 was already widespread [61]. The rate of use of thromboprophylaxis, either at high or low dose, in our study was high, with more than 90% of the participants having used it. Furthermore, since the publication of the Recovery trial [62], dexamethasone has been included in the treatment of patients with COVID-19, when they require using oxygen therapy or ventilatory support. It is possible that this has also influenced the decreased incidence of VTE, through reduced inflammation and, therefore, the thrombotic potential. [63]. We also hypothesize there could be an underestimation of the occurrence of VTE due to limited access to objective tests, to avoid spreading out the disease. Nevertheless, even considering an incidence of 6.7%, it was higher than that described in other viral infections, supporting the thrombogenic potential of COVID-19 [64].

When compared to the group without VTE, the use of invasive mechanical ventilation, the need for renal replacement therapy and in-hospital mortality were about twice as high in patients with VTE, reinforcing the prognostic importance of thrombotic events in patients with COVID-19 [14, 15, 21, 38, 41]. As expected, the bleeding rate was higher in groups with VTE, due to the more frequent use of therapeutic doses of anticoagulants. However, most of these bleeding events were non-serious. Although there was no difference in the severity of bleeding between the groups, the analysis was underpowered as the number of events was quite small. The sources of bleeding in each group are described in Table S4.

This study has some limitations. First, this is a pragmatic study, with retrospective data collection, which resulted in missing data on some laboratory tests. Second, all variables analyzed were collected upon hospital admission, as we would like to provide evidence to alert clinicians, so they could be able to identify, as soon as possible, patients at the highest risk of VTE, allowing for prompt diagnosis and treatment. Therefore, other relevant factors that could increase the risk of VTE, occurring during hospitalization, were not evaluated. Third, laboratory tests were not centralized. In particular, D-dimer was performed using different methodologies, according to local hospitals. We strongly believe that the way we analyzed, in relative values, increases the applicability of our findings. Fourth, although we consider the potential of ML to contribute to the identification of VTE risk factors in patients with COVID-19, its predictive performance still needs to be prospectively verified. Fifth, to more properly assess for outcomes, it would be necessary to build prediction models, which is outside the scope of this manuscript. Ultimately, in more than 2 years of a pandemic and, after the surge of variants and people have been vaccinated, the presentation of the COVID-19 disease has varied greatly, both in clinical manifestation and in severity.

Conclusion

We evaluated predictors of VTE in a large cohort of patients with COVID-19 using both LR analysis and ML approaches. There was consistency between them, by which we identified that D-dimer, axillary temperature, neutrophils count, C-reactive protein and lactate as risk factors for VTE. We suggest that patients presenting these risk factors at admission should be more closely monitored for VTE development. SF ratio, prophylactic use of anticoagulant and atrial fibrillation, probably as a proxy of anticoagulant use, are protective of VTE development in COVID-19 patients. Finally, we observed that the occurrence of VTE had an impact on higher mortality, the need for mechanical ventilation and renal replacement therapy, reinforcing the importance of early diagnosis and treatment.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Abbreviations

- AIC

Akaike information criterion

- ALT

Alanine aminotransferase

- aPTT

Activated partial thromboplastin time

- 95% CI

95% Confidence interval

- COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 19

- CRF

Case report form

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- CUS

Compression ultrasonography

- DDU

D-dimer units

- DMP

Data management plan

- DVT

Deep venous thrombosis

- AF

Atrial fibrillation

- FEU

Fibrinogen equivalent units

- ICU

Intensive care units

- ISTH

International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis

- IQR

Interquartile ranges

- LDH

Lactate dehydrogenase

- LR

Logistic regression

- ML

Machine learning

- OR

Odds ratio

- PaO2/FiO2

Ratio of arterial oxygen partial pressure over inspired oxygen fraction

- PE

Pulmonary embolism

- REDCap

Research Electronic Data Capture

- SARS

Severe acute respiratory syndrome

- SHAP

Shapley Additive ExPlanation

- SF ratio

Peripheral oxygen saturation/inspired oxygen fraction

- VTE

Venous thromboembolism

Author contributions

Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work: MSM and WCS. Substantial contributions to the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work: MSM, WCS, MCP, LEFR, RTS, BBMP, AVS, AFG, BSMB, BMC, CMR, CDG, CCRC, ECP, EWR, EMSK, FA, FAB, FFMGA, FGA, GPC, GGV, GANB, JHSMC, JRCSF, KBR, LSO, LSP, LSP, LBS, LSFC, LK, MAF, MMS, MC, MAPF, MCAN, MAPM, MNZF, MHGJ, NCSS, NRO, NMP, PGSA, PLA, RAV, RMM, SCF, SMMG, SFA, SAP, TK, TOF and MAG. Drafted the work: MSM, MCP, PDP, BBMP and WCS. Revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content: all the authors. Final approval of the version to be published: all the authors. Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved: MSM, MCP and WCS.

Funding

This study was supported in part by Minas Gerais State Agency for Research and Development (Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais—FAPEMIG, Belo Horizonte, Brazil) [grant number APQ-00208-20], National Institute of Science and Technology for Health Technology Assessment (Instituto de Avaliação de Tecnologias em Saúde—IATS, Porto Alegre, Brazil)/National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico—CNPq, Distrito Federal, Brazil) [grant number 465518/2014-1], and CAPES Foundation (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior) [grant number 88887.507149/2020-00]. The sponsors had no role in study design; data collection, management, analysis, and interpretation; writing the manuscript; and decision to submit it for publication. MSM and MP had full access to all the data in the study and had responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. Thanking participant(s) We would like to thank the hospitals which are part of this collaboration, for supporting this project: Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre; Hospital Eduardo de Menezes; Hospital Julia Kubitschek; Hospital Mãe de Deus; Hospital Márcio Cunha; Hospital Mater Dei Betim-Contagem; Hospital Mater Dei Contorno; Hospital Mater Dei Santo Agostinho; Hospital Metropolitano Dr. Célio de Castro; Hospital Moinhos de Vento; Hospital Nossa Senhora da Conceição; Hospital Santa Cruz; Hospital Santa Rosália; Hospital Semper; Hospital SOS Cárdio; Hospital Universitário de Santa Maria. We also thank all the clinical staff at those hospitals, who cared for the patients, and all undergraduate students who helped with data collection.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Brazilian National Commission for Research Ethics (CAAE 30350820.5.1001.0008).

Authorship

“All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.”

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Prior presentation

This manuscript had previously been posted, as a preprint, on Research Square on January 6, 2022 (https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-1180396/v1).

Informed consent

Individual informed consent was waived due to the severity of the situation and the use of unidentified data, based on medical chart review only (see attached document).

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Warley Cezar da Silveira, Email: warleysilveira@gmail.com.

Lucas Emanuel Ferreira Ramos, Email: luckermos19@gmail.com.

Rafael Tavares Silva, Email: rafaelsilva@posteo.net.

Bruno Barbosa Miranda de Paiva, Email: brunobarbosa.mpaiva@gmail.com.

Polianna Delfino Pereira, Email: polidelfino@yahoo.com.br.

Alexandre Vargas Schwarzbold, Email: alexvspoa@gmail.com.

Andresa Fontoura Garbini, Email: andrygarbini@hotmail.com.

Bruna Schettino Morato Barreira, Email: brunasmbarreira@gmail.com.

Bruno Mateus de Castro, Email: brunocastro1199@gmail.com.

Carolina Marques Ramos, Email: carol.marques@live.com.

Caroline Danubia Gomes, Email: carolinegomes.pesquisaclinica@gmail.com.

Christiane Corrêa Rodrigues Cimini, Email: christiane.cimini@gmail.com.

Elayne Crestani Pereira, Email: elaynepp@yahoo.com.br.

Eliane Würdig Roesch, Email: eroesch@hcpa.edu.br.

Emanuele Marianne Souza Kroger, Email: manu.kroger@gmail.com.

Felipe Ferraz Martins Graça Aranha, Email: felipegracaaranha@hotmail.com.

Fernando Anschau, Email: afernando@ghc.com.br.

Fernando Antonio Botoni, Email: fbotoni@medicina.ufmg.br.

Fernando Graça Aranha, Email: fgaranha@icloud.com.

Gabriela Petry Crestani, Email: gabrielapetryc@gmail.com.

Giovanna Grunewald Vietta, Email: ggvietta@gmail.com.

Gisele Alsina Nader Bastos, Email: gisele.nader@hmv.org.br.

Jamille Hemétrio Salles Martins Costa, Email: jamillesalles@yahoo.com.br.

Jéssica Rayane Corrêa Silva da Fonseca, Email: jessicarcsfonseca@gmail.com.

Karen Brasil Ruschel, Email: karenbruschel@gmail.com.

Leonardo Seixas de Oliveira, Email: seixasleo@yahoo.com.br.

Lílian Santos Pinheiro, Email: lilian.pinheiro98@hotmail.com.

Liliane Souto Pacheco, Email: lilianespacheco@gmail.com.

Luciana Borges Segala, Email: lrsegala@gmail.com.

Luciana Siuves Ferreira Couto, Email: lucianasiuves@gmail.com.

Luciane Kopittke, Email: kluciane@ghc.com.br.

Maiara Anschau Floriani, Email: maiara.floriani@hmv.org.br.

Majlla Magalhães Silva, Email: majlla.mag@gmail.com.

Marcelo Carneiro, Email: marceloc@unisc.br.

Maria Angélica Pires Ferreira, Email: mpiferreira@hcpa.edu.br.

Maria Auxiliadora Parreiras Martins, Email: auxiliadorapmartins@hotmail.com.

Marina Neves Zerbini de Faria, Email: marinanzfaria@yahoo.com.br.

Matheus Carvalho Alves Nogueira, Email: mathnogueira42@gmail.com.

Milton Henriques Guimarães Júnior, Email: miltonhenriques@yahoo.com.br.

Natália da Cunha Severino Sampaio, Email: natsamster@gmail.com.

Neimy Ramos de Oliveira, Email: neimyramos@gmail.com.

Nicole de Moraes Pertile, Email: nicole.pertile@hmv.org.br.

Pedro Guido Soares Andrade, Email: peuguido@icloud.com.

Pedro Ledic Assaf, Email: pedro.ledic@hmdcc.com.br.

Reginaldo Aparecido Valacio, Email: ravalacio@hotmail.com.

Rochele Mosmann Menezes, Email: rochelemenezes@unisc.br.

Saionara Cristina Francisco, Email: saionaracf@gmail.com.

Silvana Mangeon Meirelles Guimarães, Email: smangeon@gmail.com.

Silvia Ferreira Araújo, Email: silviaferreiragastro@gmail.com.

Suely Meireles Rezende, Email: srezende@medicina.ufmg.br.

Susany Anastácia Pereira, Email: susany2808@gmail.com.

Tatiana Kurtz, Email: kurtz@unisc.br.

Tatiani Oliveira Fereguetti, Email: tatianifereguetti@gmail.com.

Carísi Anne Polanczyk, Email: carisi.anne@gmail.com.

Magda Carvalho Pires, Email: magda@est.ufmg.br.

Marcos André Gonçalves, Email: mgoncalv@dcc.ufmg.br.

Milena Soriano Marcolino, Email: milenamarc@ufmg.br.

References

- 1.The Lancet Haematology Thromboembolism: an underappreciated cause of death. Lancet Haematol. 2015;2:e393. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(15)00202-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heit JA, O’Fallon WM, Petterson TM, et al. Relative impact of risk factors for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1245. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.11.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tagalakis V, Patenaude V, Kahn SR, Suissa S. Incidence of and mortality from venous thromboembolism in a real-world population: the Q-VTE study cohort. Am J Med. 2013;126:832.e13–832.e21. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith SB, Geske JB, Maguire JM, et al. Early anticoagulation is associated with reduced mortality for acute pulmonary embolism. Chest. 2010;137:1382–1390. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-0959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Libby P, Lüscher T. COVID-19 is, in the end, an endothelial disease. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:3038–3044. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ranucci M, Ballotta A, di Dedda U, et al. The procoagulant pattern of patients with COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1747–1751. doi: 10.1111/jth.14854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lowenstein CJ, Solomon SD. Severe COVID-19 is a microvascular disease. Circulation. 2020;142:1609–1611. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.050354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levi M, Iba T. COVID-19 coagulopathy: is it disseminated intravascular coagulation? Intern Emerg Med. 2020;16(2):309–312. doi: 10.1007/s11739-020-02601-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suh YJ, Hong H, Ohana M, et al. Pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis in COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiology. 2021;298:E70–E80. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020203557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kefale B, Tegegne GT, Degu A, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of thromboembolism among patients with coronavirus disease-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2020;26:107602962096708. doi: 10.1177/1076029620967083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hill JB, Garcia D, Crowther M, et al. Frequency of venous thromboembolism in 6513 patients with COVID-19: a retrospective study. Blood Adv. 2020;4:5373–5377. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020003083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Helms J, Tacquard C, Severac F, et al. High risk of thrombosis in patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:1089–1098. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06062-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Llitjos J, Leclerc M, Chochois C, et al. High incidence of venous thromboembolic events in anticoagulated severe COVID-19 patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1743–1746. doi: 10.1111/jth.14869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bilaloglu S, Aphinyanaphongs Y, Jones S, et al. Thrombosis in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in a New York city health system. JAMA. 2020;324:799. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.13372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malas MB, Naazie IN, Elsayed N, et al. Thromboembolism risk of COVID-19 is high and associated with a higher risk of mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EclinicalMed. 2020;29–30:100639. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stokes EK, Zambrano LD, Anderson KN, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 case surveillance—United States, January 22–May 30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:759–765. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6924e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan. China JAMA. 2020;323:1061. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poli D, Antonucci E, Ageno W, et al. Low in-hospital mortality rate in patients with COVID-19 receiving thromboprophylaxis: data from the multicentre observational START-COVID register. Intern Emerg Med. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s11739-021-02891-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosovsky RP, Grodzin C, Channick R, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary embolism during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Chest. 2020;158:2590–2601. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.08.2064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moll M, Zon RL, Sylvester KW, et al. VTE in ICU patients With COVID-19. Chest. 2020;158:2130–2135. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.07.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fauvel C, Weizman O, Trimaille A, et al. Pulmonary embolism in COVID-19 patients: a French cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:3058–3068. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silva BV, Jorge C, Plácido R, et al. Pulmonary embolism and COVID-19: a comparative analysis of different diagnostic models performance. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;50:526–531. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2021.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rindi LV, al Moghazi S, Donno DR, et al. Predictive scores for the diagnosis of Pulmonary Embolism in COVID-19: a systematic review. Int J Infect Dis. 2022;115:93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.11.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Henrina J, Santosa Putra IC, Cahyadi I, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of venous thromboembolism in patients hospitalized for COVID-19: systematic review and meta-analysis. Thrombosis Update. 2021;2:100037. doi: 10.1016/j.tru.2021.100037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hou L, Hu L, Gao W, et al. Construction of a risk prediction model for hospital-acquired pulmonary embolism in hospitalized patients. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2021;27:107602962110408. doi: 10.1177/10760296211040868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marcolino MS, Ziegelmann PK, Souza-Silva MVR, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in Brazil: Results from the Brazilian COVID-19 registry. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;107:300–310. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cerdà P, Ribas J, Iriarte A, et al. Blood test dynamics in hospitalized COVID-19 patients: potential utility of D-dimer for pulmonary embolism diagnosis. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0243533. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0243533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen SL, Gianos E, Barish MA, et al. Prevalence and predictors of venous thromboembolism or mortality in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Thromb Haemost. 2021;121:1043–1053. doi: 10.1055/a-1366-9656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.World Health Organization Diagnostic testing for SARS-CoV-2. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/diagnostic-testing-for-sars-cov-2. Accessed 30 January 2022.

- 30.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gregory KE, Radovinsky L. Research strategies that result in optimal data collection from the patient medical record. Appl Nurs Res. 2012;25:108–116. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spyropoulos AC, Levy JH, Ageno W, et al. Scientific and Standardization Committee communication: clinical guidance on the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1859–1865. doi: 10.1111/jth.14929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Konstantinides SV, Meyer G, Becattini C, et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS) Eur Heart J. 2020;41:543–603. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lundberg S, Lee S-I (2017) A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. arXiv:1705.07874

- 36.Hastie T TR, & FJH (2009) The elements of statistical learning: data mining, inference, and prediction, 2nd ed. Springer, New York

- 37.Favaloro EJ, Thachil J. Reporting of D-dimer data in COVID-19: some confusion and potential for misinformation. Clin Chem Lab Med (CCLM) 2020;58:1191–1199. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2020-0573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li J, Wang H, Yin P, et al. Clinical characteristics and risk factors for symptomatic venous thromboembolism in hospitalized COVID-19 patients: a multicenter retrospective study. J Thromb Haemost. 2021;19:1038–1048. doi: 10.1111/jth.15261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bikdeli B, Madhavan MV, Jimenez D, et al. COVID-19 and thrombotic or thromboembolic disease: implications for prevention, antithrombotic therapy, and follow-up. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2950–2973. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Caron A, Depas N, Chazard E, et al. Risk of pulmonary embolism more than 6 weeks after surgery among cancer-free middle-aged patients. JAMA Surg. 2019;154:1126. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.3742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen S, Zheng T, Wang S, et al. Association between risk of venous thromboembolism and mortality in patients with COVID-19. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;108:543–549. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mertens I, van Gaal LF. Obesity, haemostasis and the fibrinolytic system. Obes Rev. 2002;3:85–101. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-789X.2002.00056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Basili S, Pacini G, Guagnano MT, et al. Insulin resistance as a determinant of platelet activation in obese women. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:2531–2538. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Juhan-Vague I, Alessi M-C, Mavri A, Morange PE. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, inflammation, obesity, insulin resistance and vascular risk. J Thromb Haemost. 2003;1:1575–1579. doi: 10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pannacciulli N, de Mitrio V, Marino R, et al. Effect of glucose tolerance status on PAI-1 plasma levels in overweight and obese subjects. Obes Res. 2002;10:717–725. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goichot B, Grunebaum L, Desprez D, et al. Circulating procoagulant microparticles in obesity. Diabetes Metab. 2006;32:82–85. doi: 10.1016/S1262-3636(07)70251-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morel O, Luca F, Grunebaum L, et al. Short-term very low-calorie diet in obese females improves the haemostatic balance through the reduction of leptin levels, PAI-1 concentrations and a diminished release of platelet and leukocyte-derived microparticles. Int J Obes. 2011;35:1479–1486. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Farsalinos K, Barbouni A, Niaura R. Systematic review of the prevalence of current smoking among hospitalized COVID-19 patients in China: could nicotine be a therapeutic option? Intern Emerg Med. 2020;15(5):845–852. doi: 10.1007/s11739-020-02355-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kaplan D, Casper TC, Elliott CG, et al. VTE incidence and risk factors in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. Chest. 2015;148:1224–1230. doi: 10.1378/chest.15-0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grimnes G, Isaksen T, Tichelaar YIGV, et al. Acute infection as a trigger for incident venous thromboembolism: results from a population-based case-crossover study. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2018;2:85–92. doi: 10.1002/rth2.12065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schultz MJ, Haitsma JJ, Zhang H, Slutsky AS. Pulmonary coagulopathy as a new target in therapeutic studies of acute lung injury or pneumonia—a review. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:871–877. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000201882.23917.B8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Castro RA, Frishman WH. Thrombotic complications of COVID-19 infection. Cardiol Rev. 2021;29:43–47. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0000000000000347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marcolino MS, Pires MC, Ramos LEF, et al. ABC2-SPH risk score for in-hospital mortality in COVID-19 patients: development, external validation and comparison with other available scores. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;110:281–308. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.07.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rice TW, Wheeler AP, Bernard GR, et al. Comparison of the Spo2/Fio2 ratio and the Pao2/Fio2 ratio in patients with acute lung injury or ARDS. Chest. 2007;132:410–417. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moonla C, Sosothikul D, Chiasakul T, et al. Anticoagulation and in-hospital mortality from coronavirus disease 2019: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2021;27:107602962110089. doi: 10.1177/10760296211008999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.The REMAP-CAP, ACTIV-4a, and ATTACC Investigators (2021) Therapeutic anticoagulation with heparin in critically Ill patients with Covid-19. New England J Med 385:777–789. 10.1056/NEJMoa2103417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Spyropoulos AC, Goldin M, Giannis D, et al. Efficacy and safety of therapeutic-dose heparin vs standard prophylactic or intermediate-dose heparins for thromboprophylaxis in high-risk hospitalized patients with COVID-19. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181:1612. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.6203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mohnen SM, Rotteveel AH, Doornbos G, Polder JJ. Healthcare expenditure prediction with neighbourhood variables—a random forest model. Stat Polit Policy. 2020;11:111–138. doi: 10.1515/spp-2019-0010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Friedman JH. Greedy function approximation: a gradient boosting machine. Ann Stat. 2001;29:1189–1232. doi: 10.1214/aos/1013203451. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sagawa S, Raghunathan A, Koh PW, Liang P (2020) An investigation of why overparameterization exacerbates spurious correlations. arXiv:2005.04345

- 61.Ren B, Yan F, Deng Z, et al. Extremely high incidence of lower extremity deep venous thrombosis in 48 patients with severe COVID-19 in Wuhan. Circulation. 2020;142:181–183. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.The RECOVERY Collaborative Group (2021) Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. New England J Med 384:693–704. 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.van Zaane B, Nur E, Squizzato A, et al. Systematic review on the effect of glucocorticoid use on procoagulant, anti-coagulant and fibrinolytic factors. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:2483–2493. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.04034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bunce PE, High SM, Nadjafi M, et al. Pandemic H1N1 influenza infection and vascular thrombosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:e14–e17. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.