Abstract

Unique patterns of biomarkers were reproducibly characterized by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI)–mass spectrometry and were used to distinguish Bacillus species members from one another. Discrimination at the strain level was demonstrated for Bacillus cereus spores. Lipophilic biomarkers were invariant in Bacillus globigii spores produced in three different media and in B. globigii spores stored for more than 30 years. The sensitivity was less than 5,000 cells deposited for analysis. Protein biomarkers were also characterized by MALDI analysis by using spores treated briefly with corona plasma discharge. Protein biomarkers were readily desorbed following this treatment. The effect of corona plasma discharge on the spores was examined.

A number of gram-positive bacteria form spores when they encounter a nutrient shortage or are exposed to certain chemicals. The genera Bacillus and Clostridium are the classical genera that form endospores (7). In recent years the genus Bacillus has been divided into several groups or genera (for details see reference 11). Bacillus strains and, in particular, Bacillus species are not easily distinguished by spore analysis (14). Current technology has failed to yield immunological, biochemical, or nucleic acid-based methods for identifying spores of these organisms rapidly and definitively. Because of the resistance of spores (13), the approaches that are most frequently used to identify them require, as a first step, germination and culturing of the resulting vegetative bacteria. DNA- and RNA-based characterization also requires complex sample preparation. More rapid antibody-based analytical methods have been described, and these methods identify the genus Bacillus; however, they do not distinguish Bacillus spores at the species level (12). Since the genus Bacillus contains Bacillus thuringiensis, an industrially important nonpathogenic pesticide, Bacillus cereus, a noninfectious food pathogen, and Bacillus anthracis, a lethal infectious pathogenic bacterium, rapid discrimination of the spores from each other is necessary for effective intervention and treatment of human disease. In this study we evaluated matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI)–mass spectrometry to determine whether it can be used to directly characterize Bacillus spores with speed, reliability, and sensitivity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microorganisms.

Bacillus subtilis 168, Bacillus globigii, B. thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki HD-1, and B. cereus T, B33, and NCTC8035 spores were obtained from the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID), Frederick, Md., and were grown in chemically defined sporulation medium by using previously described procedures (4). B. globigii spores were also produced in new sporulation medium (NSM) (10). The spores were harvested by mild centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min. The remaining vegetative cells were destroyed by treating the harvested material with lysozyme (50 μg/ml) in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.2). The purified spores were lyophilized and stored at −20°C. B. anthracis Sterne, a nonpathogenic strain, was prepared on plates containing NSM (10). Spore preparations were evaluated microscopically for the presence of dormant spores, germinated spores, and vegetative cells. Samples of B. globigii spores produced in 1966 and 1996 by using casein acid digest medium (CADM) were obtained from the Bioferm Corporation, Wasco, Calif. Montana soil was NIST (Gaithersburg, Md.) reference material 2710, and urban particulates were NIST reference material 1648.

Mass spectrometric study.

MALDI mass spectra were obtained with a Kompact MALDI 4 time of flight instrument (Kratos Analytical Instruments, Chestnut Ridge, N.Y.) in the linear mode at an accelerating voltage of 20 kV by using a 0.3-μs delay time. The laser fluence was typically 10 mJ/cm2. Each spectrum comprised the ions from 50 laser shots. Untreated spores were suspended (1 to 5 mg/ml) in acetonitrile–0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (70:30, vol/vol), and 0.3 μl was deposited in a well on a 20-well Kratos sample slide. The sample was covered with 0.3 μl of a 50 mM solution of sinapinic acid prepared in the same solvent mixture, unless another matrix is specified. Samples treated by corona plasma discharge (CPD) in a sample well were typically mixed with 0.3 μl of saturated sinapinic acid in acetonitrile–0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (70:30, vol/vol). Both internal and external mass markers were used to provide a mass accuracy of 1 part in 3,000.

For the sensitivity study, the number of spores in a suspension containing 5 mg (dry weight) of B. thuringiensis spores per ml of phosphate-buffered saline solution (pH 7.4) was determined by using a Petroff-Hauser counting chamber (9). The spore count was estimated to be 2.4 × 108 spores/ml. Before each determination the suspension was vortexed to ensure homogeneity. Suspension volumes between 10 and 200 nl were spotted onto a Kratos 30-well sample slide with a model 7101 1-μl syringe (Hamilton, Reno, Nev.); this procedure was carried out under a magnifying lamp. The spot size was estimated to be ∼0.5 mm for a 20-nl sample. In order to avoid carryover, the syringe was washed extensively between samples. An equal volume of the MALDI matrix solution, 50 mM 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid in methanol-deionized water (1:1, vol/vol), was added to the well and allowed to dry. Each deposition was repeated in triplicate.

The exact molecular masses of some of the biomarkers were determined with an IonSpec HiRes Fourier transform mass spectrometer (IonSpec Co. Irvine, Calif.) equipped with a 4.7-T superconducting magnet (5). An external MALDI ion source was present in a separate, differentially pumped chamber outside the magnet. The N2 laser fluence was estimated to be 40 mJ/cm2. The mass accuracy was 20 ppm. The molecular masses of other biomarkers were determined by using the Kratos MALDI time of flight instrument in linear mode with time-delayed ion extraction (2) and in reflectron mode (16); the mass accuracies were 500 and 300 ppm, respectively.

CPD.

A high-frequency, high-voltage generator (model BD-20A; MesoSystems Technology, Richland, Wash.) was used for CPD experiments (1). The original electrode was replaced with a 20-mm-diameter hollow cylinder with a sharp edge. This electrode was placed about 10 mm above each well in the sample slide in air in order to provide low-current CPD pulses with repetition rates of 120 pulses/s (1a).

B. cereus T spore viability was assessed following CPD treatment for various lengths of time. The spore samples used contained no vegetative cell debris and were >95% refractive. A total of 2 × 106 spores were added to the 20 wells of a steel MALDI slide, dried, and exposed for different periods of time to CPD. Subsequently, the spores were recovered from the slide by extensive rinsing with nuclease-free water and transferred to a 2-ml screw-top vial.

Spore viability was determined as a function of discharge time. Spores and spore debris were recovered by centrifugation at 7,000 × g for 5 min and were resuspended in 200 μl of nuclease-free water. The suspension was then inoculated onto sheep blood agar plates, and the number of CFU was determined. The calculated values represented the number of viable colonies recovered from an entire MALDI sample slide.

RNA was extracted with RNAqueous kits (Ambion, Inc., Austin, Tex.) from spores and debris recovered following 2 min of treatment by CPD and was assayed by determining UV absorbance at 260 nm. A control experiment was performed with spores that were broken open by the method of Tabatabai and Walker (15).

Electron microscopy.

Scanning electron micrographs of CPD-treated B. cereus T spores and untreated controls were obtained with a model 1820D microscope (Amray Co., Bedford, Mass.). The spores were suspended at a concentration of 5 mg/ml in acetonitrile-water (70:30, vol/vol). This stock preparation was diluted so that the final estimated concentration was 50 μg of spores/ml. Plasma discharge was performed with dried films of the spores directly on a microscope glass slide. Before introduction into the scanning electron microscope, the samples were coated with a platinum-gold alloy by using a vacuum deposition apparatus. Scanning electron micrographs were then obtained at an accelerating potential of 20 kV and a magnification of ×20,400.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

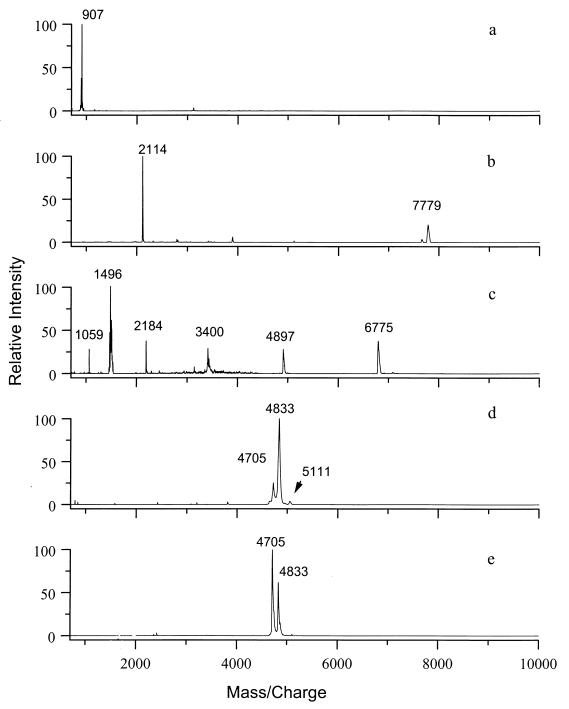

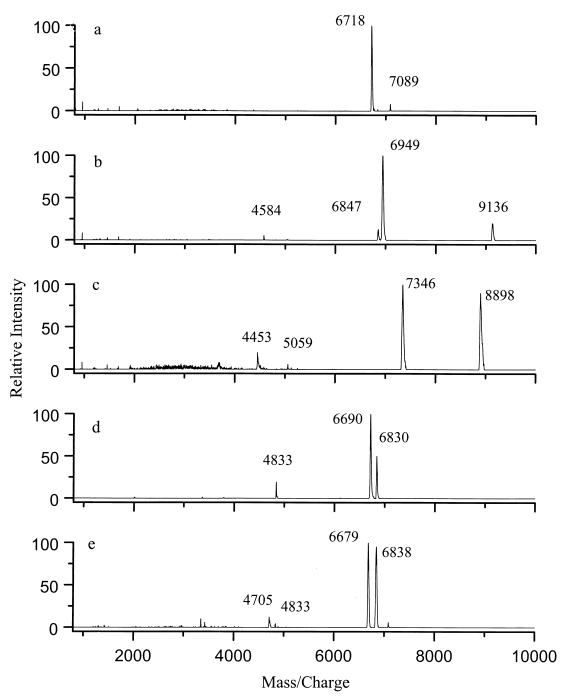

Distinctive biomarkers were present in the MALDI spectra of the spores of the five Bacillus species studied (Fig. 1). Spectra of these biomarkers were qualitatively reproduced at the University of Maryland, at USAMRIID, and at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (1). Some variability in the molecular masses was observed, and this variability could be related to replacement of protons by sodium and/or potassium cations. The molecular mass assignments shown in Fig. 1 and 2 were supported by anion MALDI spectra and high-resolution Fourier-transform mass spectrometry (FTMS) measurements. The biomarkers could be washed off the spores with a variety of organic solvents; thus, they were characterized as lipophilic and were presumed to be present on the outsides of the spores. Their structures are being studied.

FIG. 1.

Linear-mode MALDI spectra of spores of five Bacillus species. (a) B. thuringiensis subsp. kustaki HD-1. (b) B. subtilis 168. (c) B. globigii. (d) B. cereus T. (e) B. anthracis Sterne.

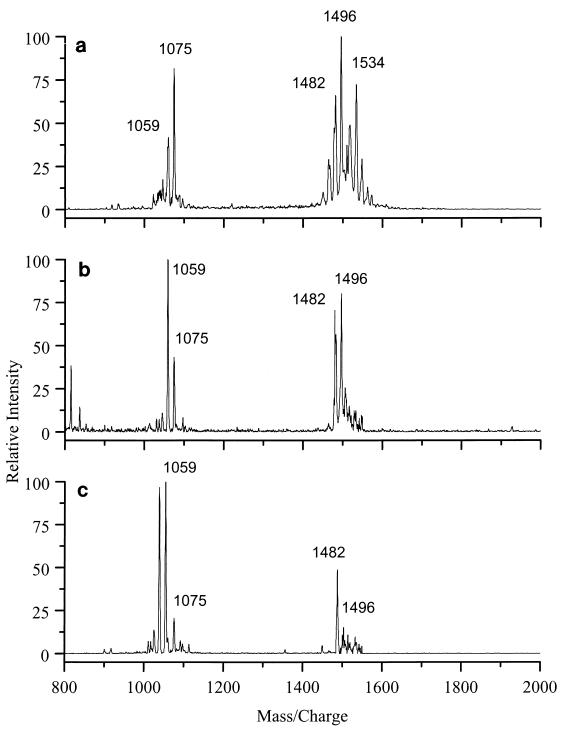

FIG. 2.

Reflectron mode MALDI spectra of B. globigii spores grown in three different media, CADM (a), chemically defined sporulation medium (b), and NSM (c).

In order to determine whether the spectra characterized secreted biomarkers or chemicals adsorbed from the growth medium, B. globigii spores were grown in three different growth media used for MALDI analysis. The spectra of the three samples all contained the same family of peaks around m/z 1059 (Fig. 2). A second set of peaks around m/z 1496 was also characteristic of B. globigii spores. One spectrum (Fig. 2a) was obtained from spores grown in CADM in 1996. The MALDI spectrum obtained from a sample of the same species grown in CADM and stored since 1966 contained the same molecular ions, but the relative intensities were different (results not shown).

More importantly, the MALDI fingerprint was reproducible. Different cultures grown on different days provided similar MALDI spectra.

The limit of detection of this technique for characterization of B. thuringiensis was evaluated by using dilutions of a suspension whose spore concentration had been determined by using a Petroff-Hauser counting chamber. A spectrum obtained from about 5,000 spores contained the peak shown in Fig. 1a, which was characteristic of B. thuringiensis spores. In this study the sensitivity was determined by limitations related to sample handling rather than by the mass spectrometer.

The molecular masses of the lipophilic biomarkers of the spores of three strains of B. cereus (T, B33, and NCTC8035) are summarized in Table 1. The spectra suggest that some Bacillus spores can be distinguished at the strain level by MALDI-mass spectrometry. The values in Table 1 were obtained in reflectron mode (see above) in order to provide accurate mass values to address this critical question.

TABLE 1.

Biomarker ions (mass range, 800 to 10,000 Da) detected by MALDI in reflectron mode from different B. cereus strains (mass accuracy, 300 ppm)

| Molecular masses (Da) of ions detected in:

| ||

|---|---|---|

| B. cereus T | B. cereus B33 | B. cereus NCTC8035 |

| 4,328 | ||

| 4,705 | 4,705 | |

| 4,792 | ||

| 4,815 | 4,815 | |

| 4,833 | 4,833 | |

| 4,871 | ||

| 5,111 | ||

| 5,145 | ||

| 5,381 | ||

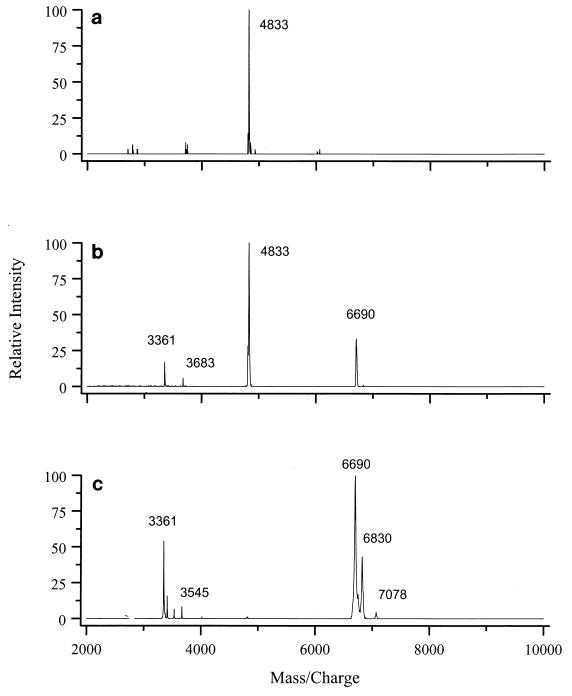

Workers in our laboratory have recently described the effectiveness of CPD for improving the accessibility of biomarkers for MALDI analysis of refractory samples (1a). The MALDI spectra of untreated B. cereus T spores and of spores treated by CPD for 5 and 30 s are shown in Fig. 3. The external biomarkers that dominated the spectrum of the untreated sample were also visible in the spectrum of spores treated for 5 s (Fig. 3a and b). However, a larger set of higher-mass ions was present in the MALDI spectra of the CPD-treated samples (Fig. 3c).

FIG. 3.

Linear-mode MALDI spectra of B. cereus T spores not treated by CPD (a) or treated by CPD for 5 s (b) or 30 s (c).

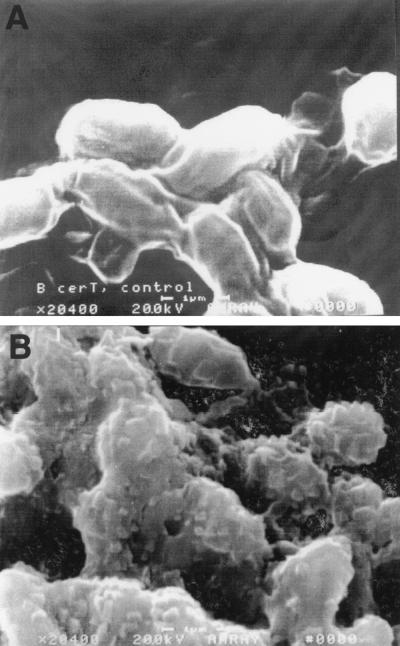

The extent and nature of spore disruption by CPD were examined by using several techniques. Electron micrographs of B. cereus T spores are shown in Fig. 4; these micrographs were obtained before and after CPD treatment for 120 s. Clearly, the outside spore surface was altered; however, the spores did not disintegrate.

FIG. 4.

Electron micrographs of B. cereus T spores before (A) and after (B) 120 s of treatment by CPD (magnification, ×20,400).

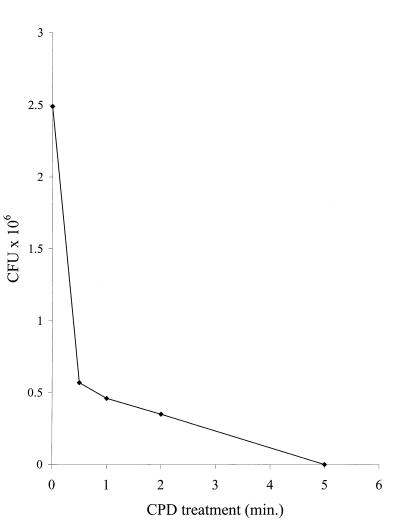

To assess the viability of the spores following CPD treatment, B. cereus T spores were enumerated on blood sheep agar plates as described above. Exposure of spores to CPD for up to 2 min reduced the viability by less than 1 log, while longer treatment times resulted in a greater than 6-log kill (Fig. 5). In addition, recovery of nucleic acids leaking from the spores treated by CPD was assayed independently. Triplicate measurements of RNA recovery revealed a 27% ± 4% increase following 2 min of CPD treatment, while a 436% increase was observed when spores were opened by using a classical method (15). The results of these experiments are consistent with the interpretation that the spore wall was modified during the short discharge times used with MALDI analysis but was not completely opened. Such resilience is appropriate for the candidate agent of universal panspermia (6).

FIG. 5.

Numbers of CFU following CPD treatment of 107 B. cereus T spores for different times.

Figure 6 shows MALDI spectra obtained after CPD treatment of the same five Bacillus species characterized in the experiment whose results are shown in Fig. 1. Clearly, the biomarker sets provided a unique and distinctive fingerprint for each of the samples studied. The external and internal biomarkers characterized in Fig. 1 and 6 could be combined to provide a larger number of biomarkers for distinguishing the species. Rule-based computer programs for this purpose are under development, and these programs do not involve library searching and do not require reproducible relative intensities of peaks. Identification based on searches of the proteome-genome database has also been proposed recently (3). When ions in the spectrum of B. subtilis 168 spores (Fig. 6b) were compared with proteins predicted on the basis of the genome of B. subtilis 168 (8), the observed molecular masses (6,846, 6,948, and 9,135 Da) matched within 1 Da the masses predicted for YvrF protein, YdiQ protein, and YuK [A-F, I-M] proteins, respectively. Entries for no other organism in the SwissProt/TrEMBL database matched more than one of the peaks.

FIG. 6.

Linear-mode MALDI spectra of spores of five Bacillus species obtained after 15 s of CPD treatment. (a) B. thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki HD-1. (b) B. subtilis 168. (c) B. globigii. (d) B. cereus T. (e) B. anthracis Sterne.

The molecular masses of biomarkers observed in MALDI spectra of samples of the three B. cereus strains obtained after 15 s of CPD treatment are summarized in Table 2. These strains are the same strains studied in the experiment whose results are shown in Table 1, and again the three strains can be readily distinguished.

TABLE 2.

Biomarker ions (mass range, 800 to 10,000 Da) detected by MALDI in linear mode from different B. cereus strains after 15 s of treatment with CPD (mass accuracy, 500 ppm)

| Molecular masses (Da) of ions detected in:

| ||

|---|---|---|

| B. cereus T | B. cereus B33 | B. cereus NCTC8035 |

| 6,690 | 6,690 | 6,690 |

| 6,830 | 6,830 | 6,830 |

| 7,070 | 7,070 | 7,070 |

| 7,353 | ||

| 7,450 | ||

Conclusions.

MALDI-mass spectrometry provides reproducible biomarkers for characterization of spores of members of the genus Bacillus. Two classes of biomarkers have been observed. Lipophilic compounds present on the outside of the spore wall have been found to be uniquely associated with samples of different bacteria grown under a variety of conditions. Further support for the hypothesis that these compounds are true biomarkers was provided by independent characterization of B. globigii and B. thuringiensis spores at multiple sites under different sampling conditions. A larger selection of higher-mass biomarkers can be obtained when the spores are first treated by CPD, and many of these biomarkers have masses characteristic of proteins from the Bacillus proteome. These two classes of compounds can be combined to provide a larger set of biomarkers for computer-supported recognition of spores based on MALDI mass spectra.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Brandon Falk and Danying Zhu for culturing the spores used in this study; John Ezzell and Terry Abshire for providing facilities and advice for the spore viability assays performed at USAMRIID, Frederick, Md.; and Miquel Antoine for mass spectrometry measurements obtained at the Applied Physics Laboratory, Columbia Md. Scanning electron microscopy was performed at the Laboratory for Biological Ultra-Structure, a core facility of the College of Life Sciences at the University of Maryland.

This work was supported by contracts from the Applied Physics Laboratory of Johns Hopkins University.

REFERENCES

- 1.Antoine, M. Personal communication.

- 1a.Birmingham J, Demirev P, Ho Y P, Thomas J, Bryden W, Fenselau C. Corona plasma discharge for rapid analysis of microorganisms by mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 1999;13:604–606. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0231(19990415)13:7<604::AID-RCM529>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cotter R J. Delayed extraction MALDI. In: Cotter R J, editor. Time of flight mass spectrometry. Instrumentation and applications in biological Research. Washington, D.C.: American Chemical Society; 1997. p. 161. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Demirev P, Ho Y P, Ryzhov V, Fenselau C. Microorganism identification by mass spectrometry and protein database searches. Anal Chem. 1999;71:2732–2738. doi: 10.1021/ac990165u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hageman J H, Shankweiller G W, Wall P R, Franich K, McCowan G W, Cauble S M, Crajeda J, Quinones C. Single, chemically defined sporulation medium for Bacillus subtilis: growth, sporulation, and extracellular protease production. J Bacteriol. 1984;160:438–441. doi: 10.1128/jb.160.1.438-441.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ho Y P, Fenselau C. Applications of 1.06 μm IR laser desorption on a Fourier-transform mass spectrometer. Anal Chem. 1998;70:4890–4895. doi: 10.1021/ac980914s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hock J K, Losick R. Panspermia, spores and the Bacillus subtilis genome. Nature. 1997;390:237–238. doi: 10.1038/36747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joklik, W. K., H. P. Willett, D. B. Amos, and C. M. Wilfert. The classification and identification of bacteria, p. 13. In W. K. Joklik et al. (ed.), Zinsser microbiology—1992. Appleton and Lange, Norwalk, Conn.

- 8.Kunst F, et al. The complete genome sequence of the gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Nature. 1997;390:249–256. doi: 10.1038/36786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mallette F M. Evaluation of growth by physical and chemical means. In: Norris J R, Ribbons D W, editors. Methods in microbiology—1969. London, United Kingdom: Academic Press; 1969. pp. 521–566. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phillips A P, Ezzell J W. Identification of Bacillus anthracis by polyclonal antibodies against extracted vegetative cell antigen. J Appl Bacteriol. 1989;66:419–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1989.tb05111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Priest F G. Systematics and ecology of Bacillus. In: Sonenshein A L, Hoch J A, Losick R, editors. Bacillus subtilis and other gram-positive bacteria. Biochemistry, physiology, and molecular genetics. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1993. pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quinlan J J, Foegeding P M. Monoclonal antibodies for use in detection of Bacillus and Clostridium spores. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:482–487. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.2.482-487.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roberts T A, Hitchins A D. Resistance of spores. In: Gould G W, Hurst A, editors. The bacterial spore—1969. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1969. pp. 611–670. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schnepf E, Crickmore N, Van Rie J, Lereclus D, Beaum J, Fetelson J, Zeigler D R, Dean D H. Bacillus thuringiensis and its pesticidal crystal proteins. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:775–806. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.3.775-806.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tabatabai L, Walker H W. Extraction and characterization of deoxyribonucleic acid from spores and vegetative cells of Bacillus stearothermophilus. J Bacteriol. 1967;94:1805–1806. doi: 10.1128/jb.94.5.1805-1806.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vorm O, Matthias M. Improved mass accuracy in matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry of peptides. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 1994;5:955–958. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(94)80013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]