Abstract

Introduction:

Breast Implant Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma (BIA-ALCL) is a significant public health concern for women with breast implants. The increase in incidence rates underscores the need for improved methods for risk reduction and risk management. The purpose of this study was to perform a systematic review to assess surgical risk reduction techniques and analyze communication/informed consent practices in patients with textured implants.

Methods:

A systematic review of the literature was conducted in PubMed (legacy), Embase (Embase.com), and Scopus with four search strategies including key terms centered around breast reconstruction and BIA-ALCL.

Results:

A total of 571 articles were identified, of which 276 were included in the final review after duplicates were removed. After review, zero (0) articles were determined to fit the inclusion criteria of demonstrating data driven evidence of BIA-ALCL risk reduction through surgical measures, demonstrating a significant lack of data on risk reduction for BIA-ALCL.

Conclusions:

Risk management for BIA-ALCL is an evolving area requiring additional investigation. While removal of textured devices in asymptomatic patients is not currently recommended by the FDA, variability in estimates of risk have led many patients to electively replace these implants in an effort to decrease their risk of developing BIA-ALCL. To date, however, there is no evidence supporting the concept that replacing textured implants with smooth implants reduces risk for this disease. This information should be used to aid in the informed consent process for patients presenting to discuss management of textured breast implants.

INTRODUCTION

Breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL) is a significant public health concern impacting millions of women with textured implants. A decade ago, the risk for developing BIA-ALCL was thought to be as low as 0.1 to 0.3 per 100,000 patient years; however, current estimates indicate that the incidence of BIA-ALCL may be much higher.1–3 Two recent analyses from a large cohort of patients with long-term follow-up at our institution suggest that the risk for BIA-ALCL may be as high as 1/559 women, with an average time to diagnosis of 10 years.2, 3 Notably, a time-to-event analysis suggests that the risk of developing BIA-ALCL increases over time.2 This is particularly alarming to the thousands of women with textured implants who have yet to approach this 10-year mark.1

The rising incidence of BIA-ALCL has increased awareness of an association between textured implants and the development of the disease. In July 2019, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a recall of all Allergan Natrelle BIOCELL textured breast implants, often classified as macrotextured devices.4, 5 While these devices may no longer be used for reconstructive or aesthetic breast surgery, developing a management strategy for asymptomatic patients with textured implants who fear they may be at risk for BIA-ALCL is of critical importance. Current practice for conveying information on the association between textured implants and BIA-ALCL includes contacting patients with textured devices6 or having information easily accessible to patients at follow-up visits.7 Surgical options for reducing the risk of developing BIA-ALCL revolve around removing the textured device, with subsequent closure, exchange to smooth devices, or conversion to autologous reconstruction.

Current guidelines from the FDA do not recommend replacing or removing textured implants in asymptomatic patients.4, 5 This recommendation is likely due to a paucity of data on the efficacy of implant removal/exchange to decrease the risk of developing BIA-ALCL. In an effort to guide informed consent and shared decision-making, the purpose of this study was to perform a systematic review of the literature to search for evidence supporting surgical risk reduction of BIA-ALCL among women with textured breast implants. Additionally, we present our institutional approach to managing risk for BIA-ALCL in asymptomatic patients with textured devices.

METHODS

In accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines, we conducted a comprehensive search of the literature in the following bibliographic databases on January 18, 2020: PubMed (legacy), Embase (Embase.com), and Scopus. The four search strategy components were related to breast/mammaplasty, prosthesis, anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL), and strategies/practices for ALCL risk reduction, respectively. The search terms used were subject headings (MeSH, Emtree terms) and/or keywords. Boolean operators OR and AND were used to combine the search terms and the search strategy components. Search results were limited to English; no time limits were applied.

The search strategy included the following key terms: ((“Breast Implants”[MeSH] OR BIA-ALCL[tiab] OR “Breast”[MeSH] OR “Mammaplasty”[Mesh] OR breast[tiab] OR breasts[tiab] OR mammaplasty[tiab] OR mammaplasties[tiab] OR mammoplasty[tiab] OR mammoplasties[tiab] OR mammary[tiab]) AND (“Prostheses and Implants”[Mesh] OR “Prosthesis Implantation”[Mesh] OR BIA-ALCL[tiab] OR implant[tiab] OR implants[tiab] OR implantation[tiab] OR prosthesis[tiab] OR prostheses[tiab] OR endoprosthesis[tiab] OR endoprostheses[tiab] OR prosthetic[tiab] OR endoprosthetic[tiab]) AND (“Lymphoma, Large-Cell, Anaplastic”[Mesh] OR ALCL[tiab] OR anaplastic[tiab]) AND (“Device Removal”[MeSH] OR “Reoperation”[MeSH] OR“Adipose Tissue/transplantation”[MeSH] OR ”Surgical Flaps”[Mesh] OR “Transplantation, Autologous”[Mesh] OR “prevention and control” [Subheading] OR removal[tiab] OR remove[tiab] OR removes[tiab] OR removed[tiab] OR removing[tiab] OR replacement[tiab] OR replace[tiab] OR replaced[tiab] OR replaces[tiab] OR replacing[tiab] OR exchange[tiab] OR exchanged[tiab] OR exchanges[tiab] OR exchanging[tiab] OR capsulectomy[tiab] OR capsulectomies[tiab] OR autologous[tiab] OR flap[tiab] OR flaps[tiab] OR graft[tiab] OR grafts[tiab] OR grafting[tiab] OR autograft[tiab] OR autografts[tiab] OR autografting[tiab] OR autotransplant[tiab] OR autotransplants[tiab] OR autotransplantation[tiab] OR autotransplantations[tiab] OR fat transfer[tiab] OR lipomodeling[tiab] OR lipomodelling[tiab] OR mastopexy[tiab] OR risk reduction[tiab] OR reducing risk[tiab] OR reducing risks[tiab] OR reduce risk[tiab] OR reduced risk[tiab] OR reduced risks[tiab] OR reduces risk[tiab] OR prevention[tiab] OR preventive[tiab] OR preventative[tiab] OR prevent[tiab] OR prevents[tiab] OR prevented[tiab] OR preventing[tiab] OR prophylaxis[tiab] OR prophylactically[tiab] OR prophylactics[tiab] OR re-operation[tiab] OR reoperation[tiab] OR smooth[tiab] OR recommendation[tiab] OR recommendations[tiab] OR recommend[tiab] OR recommends[tiab] OR recommended[tiab] OR recommending[tiab] OR guideline[tiab] OR guidelines[tiab])) AND (English[lang]).

Abstracts were screened for inclusion by two reviewers (SD and TP). Any abstracts with conflicting evidence were resolved by the lead author (JN). Screened articles were categorized by study type and methodology. Inclusion criteria included any study which presented data examining surgical risk reduction of BIA-ALCL among women with textured breast implants.

RESULTS

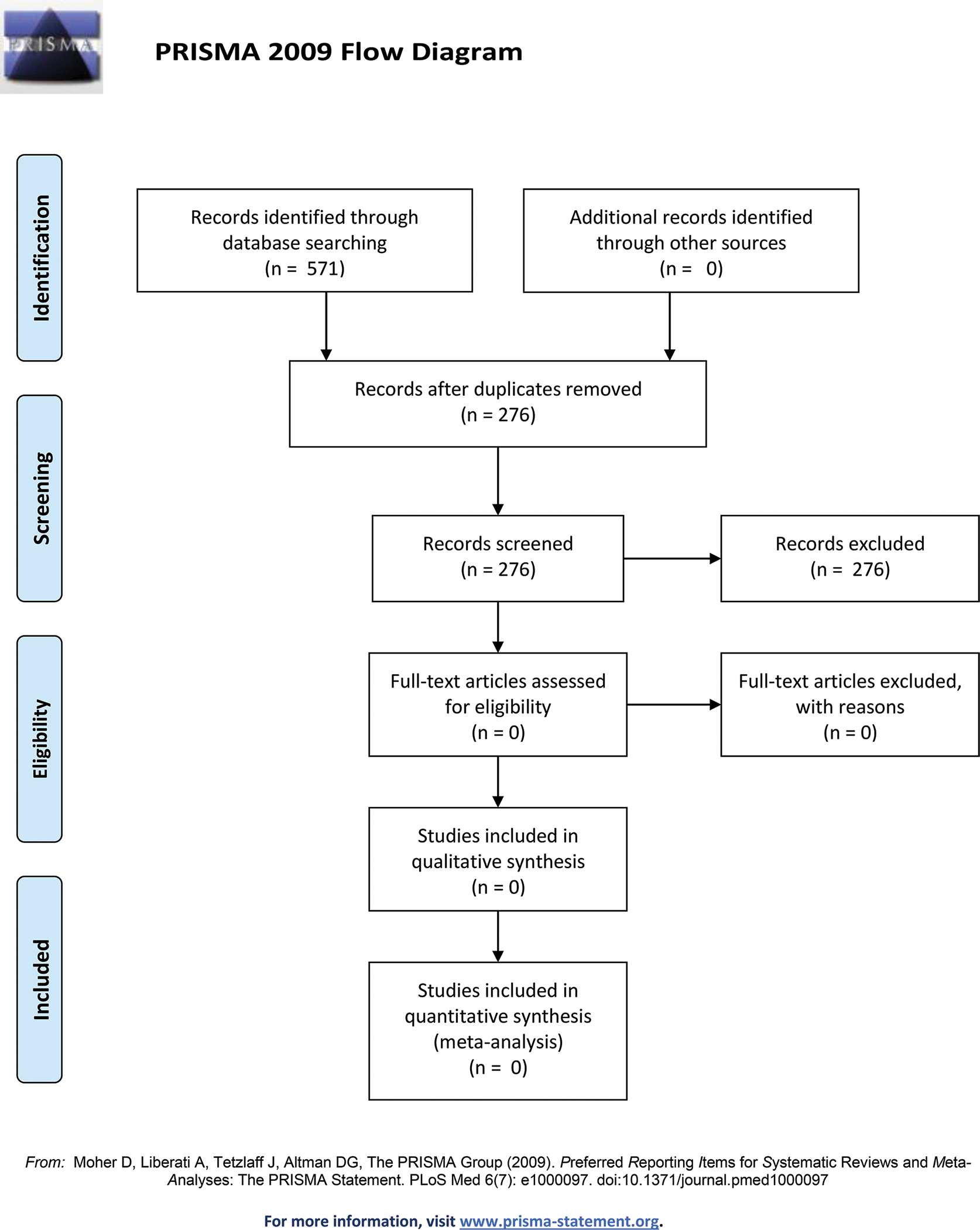

Our systematic search of the literature yielded 571 records. After duplicates were excluded, 276 articles were reviewed for inclusion in this analysis. Inclusion criteria specified any analysis of risk reduction for BIA-ALCL. Both reviewers concluded that none of the 276 articles met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

BIA-ALCL Surgical Risk Management Systematic Review

The articles reviewed are summarized in Table 1; the majority were case reports or case series (n=70), followed by narrative reviews (n=29), literature reviews (n=13), and commentaries (n=18).

Table 1.

Summary of Reviewed Articles by Study Type and Primary Topics Addressed by Search Results

| Study Type | BIA-ALCLa | Implants and Surgical Practicesb | Pathologyc |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case report / Case series | 67 | 0 | 3 |

| Cohort | 9 | 8 | 6 |

| Narrative review | 13 | 10 | 6 |

| Clinical trial | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Commentary | 18 | 0 | 0 |

| Cross-sectional | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Basic science | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Literature review | 11 | 2 | 0 |

| Meta-analysis | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Panel review | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Registry study | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Trend analysis | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Not categorizable (n=105) |

BIA-ALCL, breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma

BIA-ALCL refers to any paper whose topic referred to the diagnosis, treatment, management, or epidemiology related to patients with BIA-ALCL.

Implants and surgical practices refer to analyses of the implants and practices used for breast reconstruction or augmentation.

Pathology refers to the assessment of pathological characteristics or disease development of BIA-ALCL.

DISCUSSION

This systematic review of the literature found no current evidence through data analysis that surgical management alters the risk for BIA-ALCL in women with textured implants. However, this finding only indicates that we have yet to answer the question of how removal of textured devices impacts risk for BIA-ALCL in asymptomatic women.

The average time to diagnosis of BIA-ALCL is 8 to 10 years following implantation with a textured breast implant,8–10 with median time to diagnosis typically ranging from 7.5 to 11 years.2, 3, 9–14 Although reported times to diagnosis may be as short as 0.4 to 2 years and as long as 32 years after textured implant exposure,10, 13, 15 our recent time-to-event analysis shows that the longer the exposure to the textured device, the higher the risk of developing BIA-ALCL.2

For women with textured implants, this information is both unnerving and concerning. For breast cancer patients who have had breast reconstruction following mastectomy to treat their cancer to then have the reconstructive device pose a cancer risk can be devastating. Adding to their burden is the fact that an increasing number of breast cancer patients are undergoing contralateral prophylactic mastectomies due to fear of cancer in the contralateral breast,16 resulting in bilateral breast reconstruction being the most common form of reconstruction in some patient populations.17, 18 Women with textured implants placed for aesthetic purposes may experience similar anxiety but without the previous cancer diagnosis and treatment. Given the FDA recall of some textured devices4, 5 and the time-to-event analysis indicating that the risk of BIA-ALCL at 10 years could be as high as 1/559 women,2 these women are faced with the challenge of deciding how to choose among their options for managing their risk for this disease.

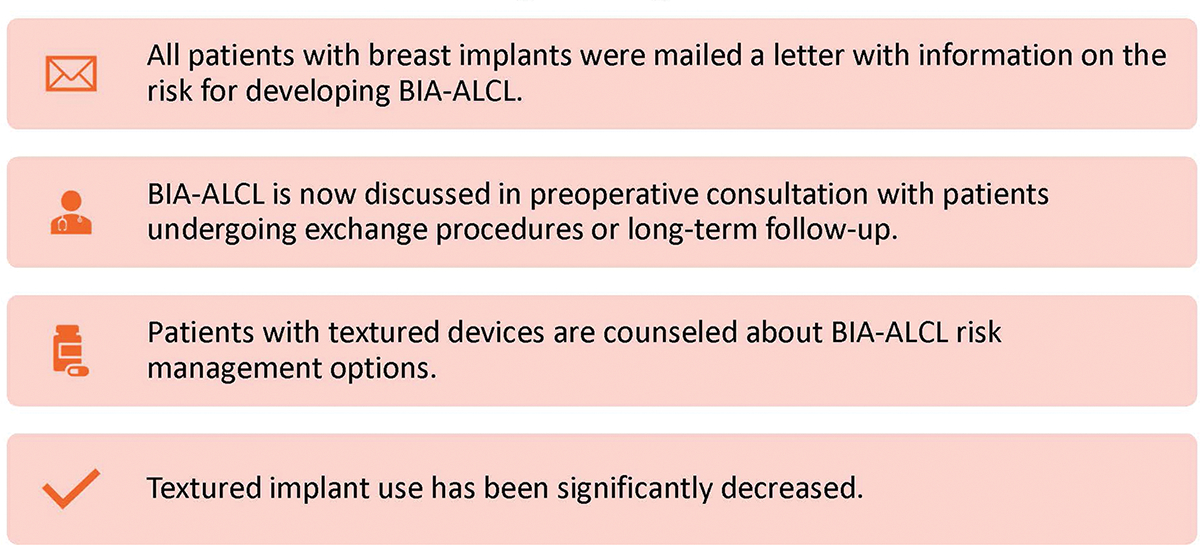

Risk Communication

The first aspect of risk management is conveying the appropriate information to the at-risk population (Figure 2). Methods used to date include mailed letters,6 in-clinic direct patient counseling,7 and web-based intiatives.4 A 2019 study by Roberts et al outlined a comprehensive approach used at Penn State University Medical College to contact 1020 patients, which resulted in few patient calls (76 patients) and few surgical procedures (9 patients).6 Invited discussions from Clemens, McCarthy, and Haddock on the Penn State approach noted that although such a comprehensive risk communication plan may not be reasonable or feasible in all settings, it was a well-presented recommendation for guiding other centers on risk management.7, 19, 20 At the very least, the Roberts et al report continues the discussion as to how best to educate patients with textured implants about their risk for BIA-ALCL. When possible, direct communication to patients should ideally be provided regarding risk, regardless of practice setting.

Figure 2.

BIA-ALCL Risk Communication Strategies

An improved understanding of BIA-ALCL pathology and textured implants indicates that inflammatory responses to the implant surface may result in malignant transformation of T lymphocytes; these abnormal T cells are characterized by expression of CD30 antigen (CD30+) and absence of Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase (ALK) expression (ALK-negative). The degree and type of texturing on the implant surface modulates the risk of malignant transformation with the highest risk in macro-textured devices.1 In response to these findings, in July 2019 the FDA recalled maco-textured BIOCELL devices marketed by Allergan Corporation.4, 5 In September 2019, the Australian regulatory counterpart (Therapeutic Goods Administration) also issued a recall of certain models of textured implants, including Allergan BIOCELL products and suspended the use of other textured implant models for 6 months except under special authorization).21 These recalls have brought renewed focus on the risk for BIA-ALCL, and while these prevent the future use of textured implants, addressing the risk management needs of asymptomatic patients who already have textured breast implants is of significant importance as well.

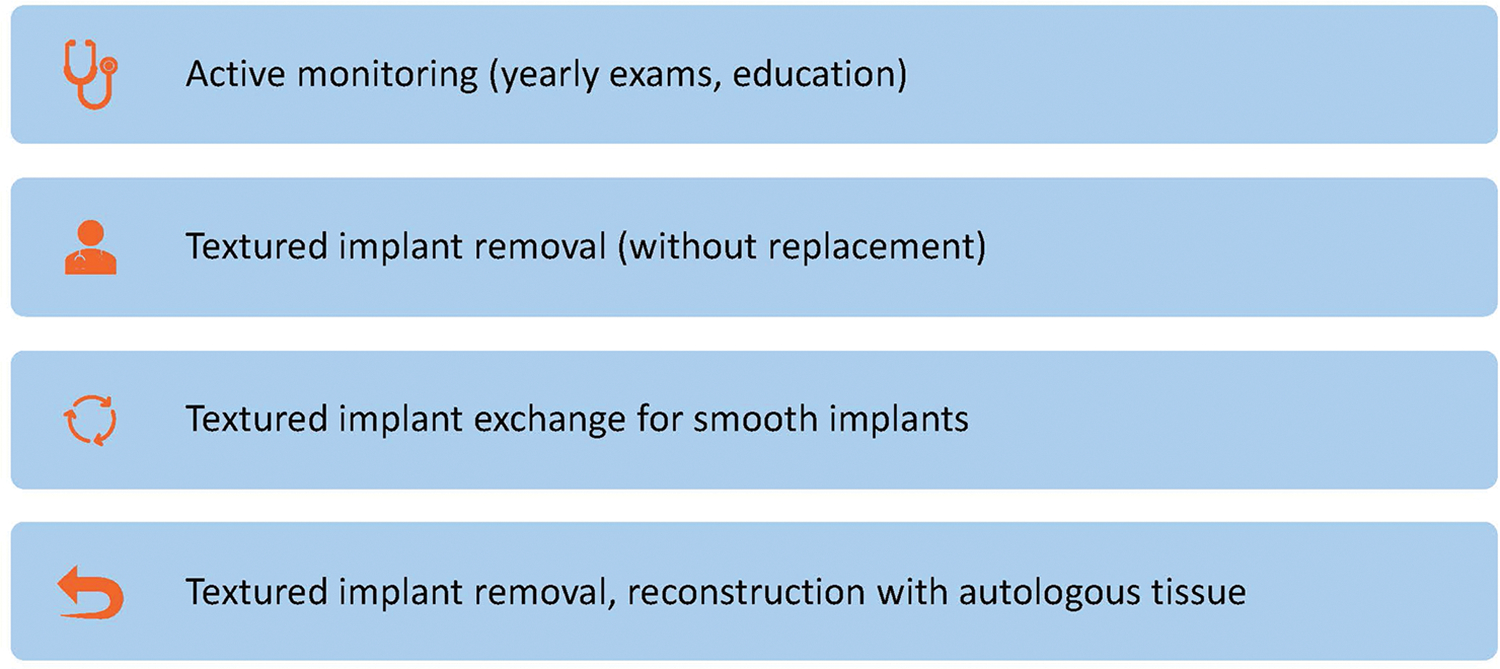

At our institution, patients presenting for BIA-ALCL counseling are offered four options for risk management (Figure 3), as detailed below.

Figure 3.

BIA-ALCL Risk Management Options

Surveillance

The first BIA-ALCL risk management option is active surveillance, which should include regular clinical examinations by a plastic surgeon and/or other health care provider. It is important to note that there is no screening test for BIA-ALCL. Screening MRIs of silicone implants should be performed as per the FDA guidelines22 in order to evaluate silicone implant integrity but are not a substitute for clinical examination in this setting. It is common for trace fluid to be found with routine imaging, but the volume of fluid that warrants further investigation has not been established. Clinicians should consider aspiration and cytology examination if fluid volume allows, but associated risks include an inconclusive sample or device rupture. Clinicians can also consider reimaging in 3 to 6 months to ensure the volume is stable and not increasing. Other screening modalities for fluid collections include ultrasound or CT scanning. On physical exam, new onset breast swelling or a newly palpable mass should prompt further investigation through imaging. Although considered the most straightforward option, surveillance does not attempt to reduce the risk for BIA-ALCL from textured implant exposure.

Surgical Risk Reduction

It is critical to first note that the U.S. FDA does not currently recommend the removal of textured devices in asymptomatic patients. Patients who wish to undergo explantation as a potential surgical risk reduction have three options: 1) device removal +/− capsulectomy and no replacement, 2) device removal +/− capsulectomy and exchange for smooth implants, or 3) device removal +/− capsulectomy and conversion to autologous tissue reconstruction (for the breast reconstruction patient).

Surgical risk reduction of BIA-ALCL is, at this point, speculative and hypothetical, based on the concept that the textured surface is the inciting and causal component of BIA-ALCL in women who may have a predisposition or environmentally related milieu to develop the disease. If BIA-ALCL has not developed at the point of removal, then, hypothetically, one can argue that removing the textured device may halt future disease development. The fact that some patients have smooth implants at the time of diagnosis of BIA-ALCL but have a history of textured device placement indicates that development of BIA-ALCL is not halted by changing implant surface types alone.2, 13 This is not well understood and warrants further investigation. Additionally, the latest FDA update reports a single case of BIA-ALCL in a patient with a smooth implant.23 While the FDA clearly states its data cannot be verified and may be inaccurate, this may give some patients pause.

Each of the surgical options to potentially reduce risk for BIA-ALCL may involve partial or total capsulectomy. Although BIA-ALCL starts in the capsule, there are no data to support removing or not removing the capsule as part of a secondary procedure to reduce risk of disease development. Capsulectomy does increase surgical risk. In some cases, such as in a breast reconstruction patient with irradiated skin and thin mastectomy flaps, total capsulectomy may risk implant loss. Partial capsulectomy in high-risk patients should be considered. Peri-prosthetic fluid and capsule specimens should be sent for analysis to rule out BIA-ALCL. It is important to recognize that in some patients who have died from BIA-ALCL, incomplete capsulectomies were performed. Certainly, should BIA-ALCL be diagnosed, a complete capsulectomy is indicated. Exchanging a textured implant for a smooth implant may have future consequences. In the least, the risks and benefits of capsulectomy should be discussed with the patient.

The patient should be informed of all surgery-related complications. Although textured implant removal and capsulectomy with closure has the lowest risk of the surgical risk reduction options, the procedure carries a low risk of bleeding, seroma, and infection. Implant exchange with capsulectomy risks entering the implant pocket, with subsequent risk of infection, hematoma, seroma, capsular contracture, and implant loss. Conversion from implant to autologous reconstruction has been associated with improved patient-reported outcomes but is the most substantial surgical risk reduction option for BIA-ALCL.24 The reported risk of flap loss in the largest series of reconstruction patients is low, approximately 1% to 2%, but perioperative complications of delayed healing, hematoma, and infection are typically higher than flap loss.25–27 Patients must understand these risks in juxtaposition with the risk of developing BIA-ALCL. The risk of a postoperative surgical complication following revision surgery is likely to be higher than even the highest risk estimates for developing BIA-ALCL. This must be discussed in the informed consent process and explicitly stated. For many women, the perceived benefits will outweigh the risks. This is an opportunity for shared decision-making, where there is currently no clear right answer. The final decision will depend on the individual patient’s preferences, values, and risk tolerance.

This study has several limitations, the most important of which is the lack of information on surgical risk reduction of BIA-ALCL in the literature. We were unable to perform an assessment of risk reduction as such. As more procedures are performed to address the anxiety about BIA-ALCL in patients with textured implants, we anticipate a growing body of literature that better outlines the risk of perioperative complications in this cohort of patients. Whether or not removing the implant directly reduces the risk for BIA-ALCL will be determined in the decades to come, as we follow patients with implants who choose different options for managing their risk for this disease.

CONCLUSIONS

Risk management of BIA-ALCL is an evolving area for surgeons who perform breast reconstruction. While current recommendations do not include prophylactic removal of textured devices, given the rising BIA-ALCL risk estimates, many patients elect surgery that, theoretically, may reduce risk. To date, however, there is no evidence in the literature to suggest that this in fact reduces the risk of developing BIA-ALCL. This information should be used to aid in the informed consent process for patients presenting to discuss management of textured breast implants.

Financial Disclosure Statement:

This research was funded in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748. Dr. Mehrara has an investigator-initiated award from PureTech Corp. and serves as an advisor to the company. All other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Collett DJ, Rakhorst H, Lennox P, Magnusson M, Cooter R, Deva AK. Current Risk Estimate of Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma in Textured Breast Implants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;143:30s–40s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nelson JA, Dabic S, Mehrara BJ, et al. Breast Implant-associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma Incidence: Determining an Accurate Risk. Ann Surg. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cordeiro PG, Ghione P, Ni A, et al. Risk of breast implant associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL) in a cohort of 3546 women prospectively followed long term after reconstruction with textured breast implants. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2020;73:841–846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.U. S. Food and Drug Administration. The FDA Requests Allergan Voluntarily Recall Natrelle BIOCELL Textured Breast Implants and Tissue Expanders from the Market to Protect Patients: FDA Safety Communication. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/safety-communications/fda-requests-allergan-voluntarily-recall-natrelle-biocell-textured-breast-implants-and-tissue. Accessed 9/28/20.

- 5.U. S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Takes Action to Protect Patients from Risk of Certain Textured Breast Implants; Requests Allergan Voluntarily Recall Certain Breast Implants and Tissue Expanders from Market. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-takes-action-protect-patients-risk-certain-textured-breast-implants-requests-allergan. Accessed 9/28/2020.

- 6.Roberts JM, Carr LW, Jones A, Schilling A, Mackay DR, Potochny JD. A Prospective Approach to Inform and Treat 1340 Patients at Risk for BIA-ALCL. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;144:46–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clemens MW, McGuire PA. Discussion: A prospective approach to inform and treat 1340 patients at risk for BIA-ALCL. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;144:57–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clemens MW, Jacobsen ED, Horwitz SM. 2019 NCCN consensus guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL). Aesthet Surg J 2019;39:S3–S13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doren EL, Miranda RN, Selber JC, et al. US epidemiology of breast implant–associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;139:1042–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brody GS, Deapen D, Taylor CR, et al. Anaplastic large cell lymphoma occurring in women with breast implants: analysis of 173 cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135:695–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leberfinger AN, Behar BJ, Williams NC, et al. Breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma: a systematic review. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:1161–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loch-Wilkinson A, Beath KJ, Knight RJW, et al. Breast implant–associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma in Australia and New Zealand: high-surface-area textured implants are associated with increased risk. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;140:645–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCarthy CM, Loyo-Berrios N, Qureshi AA, et al. Patient Registry and Outcomes for Breast Implants and Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma Etiology and Epidemiology (PROFILE): initial report of findings, 2012–2018. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;143:65s–73s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thompson PA, Prince HM. Breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma: a systematic review of the literature and mini-meta analysis. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2013;8:196–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miranda RN, Aladily TN, Prince HM, et al. Breast implant–associated anaplastic large-cell lymphoma: long-term follow-up of 60 patients. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mamtani A, Morrow M. Why Are There So Many Mastectomies in the United States? Annu Rev Med 2017;68:229–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cemal Y, Albornoz CR, Disa JJ, et al. A paradigm shift in U.S. breast reconstruction: Part 2. The influence of changing mastectomy patterns on reconstructive rate and method. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;131:320e–326e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nelson JA, Allen RJ Jr., Polanco T, et al. Long-term patient-reported outcomes following postmastectomy breast reconstruction: an 8-year examination of 3268 patients. Ann Surg. 2019;270:473–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCarthy CM. Discussion: A Prospective Approach to Inform and Treat 1340 Patients at Risk for BIA-ALCL. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;144:60–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haddock NT, Teotia SS. Discussion: A Prospective Approach to Inform and Treat 1340 Patients at Risk for BIA-ALCL. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;144:55–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Australian Government Department of Health Therapeutic Goods Administration. Breast Implants and Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma: Update -- Further Suspension of Breast Implant Devices. Available at: https://www.tga.gov.au/alert/breast-implants-and-anaplastic-large-cell-lymphoma. Accessed 9/28/2020.

- 22.U. S. Food and Drug Administration. 24 Hour Summary General and Plastic Surgery Devices Advisory Committee Meeting March 25 & 26, 2019. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/media/122960/download. Accessed 9/28/2020. [Google Scholar]

- 23.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Medical Device Reports of Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/breast-implants/medical-device-reports-breast-implant-associated-anaplastic-large-cell-lymphoma#table2-c. Accessed 10/8/2020.

- 24.Coriddi M, Shenaq D, Kenworthy E, et al. Autologous breast reconstruction after failed implant-based reconstruction: evaluation of surgical and patient-reported outcomes and quality of life. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;143:373–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carney MJ, Weissler JM, Tecce MG, et al. 5000 Free Flaps and Counting: A 10-Year Review of a Single Academic Institution’s Microsurgical Development and Outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;141:855–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Largo RD, Selber JC, Garvey PB, et al. Outcome Analysis of Free Flap Salvage in Outpatients Presenting with Microvascular Compromise. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;141:20e–27e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fischer JP, Sieber B, Nelson JA, et al. Comprehensive outcome and cost analysis of free tissue transfer for breast reconstruction: an experience with 1303 flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;131:195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]