Abstract

Objective

To identify the elements of internet-based support interventions and assess their effectiveness at reducing psychological distress, anxiety and/or depression, physical variables (prevalence, severity and distress from physical symptoms) and improving quality of life, social support and self-efficacy among patients with breast cancer.

Design

Systematic review and narrative synthesis.

Data sources

Web of Science, Cochrane Library, PubMed, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, CNKI, Wanfang and VIP from over the past 5 years of each database to June 2021.

Eligibility criteria for study selection

Included were randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or quasi-experimental (QE) studies focusing on internet-based support interventions in patients with breast cancer.

Data extraction and synthesis

Reviewers independently screened, extracted data and assessed risk of bias (Cochrane Collaboration’ risk of bias tool, Joanna Briggs Institute reviewer’s manual). Narrative synthesis included the effect and elements of internet-based support interventions for women with breast cancer.

Results

Out of 2842 articles, 136 qualified articles were preliminarily identified. After further reading the full text, 35 references were included, including 30 RCTs and five QE studies. Internet-based support interventions have demonstrated positive effects on women’s quality of life and physical variables, but inconsistent effectiveness has been found on psychological distress, symptoms of anxiety and/or depression, social support and self-efficacy.

Conclusions

Internet-based support interventions are increasingly being used as clinically promising interventions to promote the health outcomes of patients with breast cancer. Future research needs to implement more rigorous experimental design and include sufficient sample size to clarify the effectiveness of this internet-based intervention.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42021271380.

Keywords: oncology, breast tumours, telemedicine, biotechnology & bioinformatics

Strengths and limitations of this study.

It is important to identify the elements of internet-based support interventions and to understand whether these interventions positively improve patients with breast cancer’s health outcomes. Comprehensive search using a sensitive search strategy identified a lot of potential correlation research.

Due to the differences in research subjects, intervention contents, intervention programmes, outcome indicators and measurement instruments, no data synthesis was conducted for meta-analysis, and only narrative analysis was conducted.

There is insufficient evidence to determine whether any component combination is superior to other component combinations in improving the quality of life.

Introduction

Breast cancer is currently the most common malignant tumour in women worldwide.1 WHO data show that the number of new cases of breast cancer in 2020 is as high as 2.26 million, exceeding lung cancer for the first time, becoming the world’s highest incidence of cancer.2 The treatment of patients with breast cancer is based on the comprehensive treatment of surgery, supplemented by chemotherapy, radiotherapy, endocrine therapy, targeted therapy and other treatment methods. As the health system’s effectiveness in early diagnosis and treatment has improved, the number of breast cancer survivors has also increased significantly.3

However, the diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer bring patients varying degrees of treatment toxicities in the short-term, such as pain, limited limb function, hair loss, nausea and vomiting, bone marrow suppression and long-term physical and psychological distress symptoms such as impaired body image, fatigue, sleep disturbance, anxiety and depression, which seriously affect the quality of life.4–6 The importance of supporting patients adequately regarding symptoms resulting from diagnosis and treatment has been widely recognised.7 However, there are still many female patients with breast cancer who report unmet supportive care needs, and these needs are mostly in the health system/information and psychology fields.8 9 Besides, the patient’s symptom distress, self-efficacy and social support are three inter-related factors that affect a person’s ability to cope with chronic diseases.10 All the above may lead to poor quality of life for patients with breast cancer.

The survival rate of breast cancer is expected to continue to increase, leading to an increase in the number of patients requiring long-term care: this poses a challenge for the patients themselves, their families and oncology services. However, geographical distance restrictions and scheduling issues challenge the feasibility of clinical face-to-face supportive care interventions.11

At present, medical personnel can provide customised supportive care for patients with the internet as the carrier and information technology as the means (including mobile communication technology, cloud computing, internet of things, big data, etc), which is also increasingly favoured by patients with cancer.12 13 Internet-based support interventions are defined as smartphones and tablets (including applications), websites, social media and other mobile devices-delivered support programmes to provide information and facilitate communication regarding self-care management and adverse effects related to toxicities owing to breast cancer therapy.7 14 15

Internet-based support interventions often take the form of multimodal interventions, including information support, symptom management, behaviour management, psychological support, communication/interaction with health professionals and peer support. In order to meet the information and support needs, in the past few years, healthcare providers have cooperated with information technology professionals to develop self-guided psychoeducational or educational websites or application,16–20 e-health support systems21–23 in the field of cancer. In the area of symptom management research, internet-based support interventions include evidence or knowledge on self-management strategies,23 24 symptom self-reporting,22 25 symptom warning combined with risk rating assessment tools and tailored recommendations.23 25–27 Internet-based psychological support interventions include self-directed and expert-supported psychological diagnosis, treatment and counselling, are important to help patients with breast cancer transition from treatment to recovery.16 19 20 24 28–34 In the area of symptom management research, internet-based support interventions include self-report aromatase inhibitor compliance,25 35 keeping a health diary, self-diagnose lifestyle and receiving information about exercise and rehabilitation diet and nutrition from application modules24 or healthcare professionals.36 37 Internet-based forms of peer support interventions include the provision of breast cancer survivor videos,16 17 34 support group forums or discussion boards,16 17 24 30 38 39 group medical counselling40 and online and offline recovery volunteer support activities.41 42

Previous original studies have measured the effectiveness of internet-based support interventions in patients with cancer on anxiety and/or depression,18 29 psychological distress,43 44 social support,45 physical variables14 and quality of life.46 47 Among these outcomes of interest, physical variables refer to the prevalence, severity and distress from physical symptoms.15 Besides, more evidence is needed. In this fast-developing research field, it is important to regularly recapitulate its status. In addition, China is the world’s most populous country, breast cancer is one of the most common malignant tumours in Chinese women.48 This article integrates articles published in Chinese or English to help understand the impact of internet-based support interventions on patients with breast cancer at the global level.45

This systematic review aims to identify the elements of internet-based support interventions and assess their effectiveness at reducing psychological distress, anxiety and depression, physical variables, and improving quality of life, social support and self-efficacy among patients with breast cancer.

Methods

We performed a systematic review based on PRISMA guidelines, and it was registered in PROSPERO from https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/displayrecord.phpRecordID271380.

Search strategy

Seven electronic databases were searched: Web of Science, Cochrane Library, PubMed, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, CNKI, Wanfang and VIP. We searched the articles from over the past 5 years of each database to June 2021. (see online supplemental file 1) The search keywords included ‘breast neoplasm OR breast cancer’ AND ‘Telemedicine OR online OR Internet OR connected health OR telehealth OR e-health OR m-health OR e-intervention OR e-technology OR computer OR mobile application OR mobile device OR social media OR WeChat’ AND ‘patient education OR intervention OR support OR teaching OR instruction* OR program* OR psychoeducat* OR self-management OR Social Support OR support system* OR support group*’. (Full details of the search strategy employed with each database are detailed in online supplemental file 1.)

bmjopen-2021-057664supp001.pdf (171.1KB, pdf)

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

In this systematic review, we included the following: (1) The population is adult women with patients with breast cancer, (2) Studies about internet-based support interventions, defined as smartphones and tablets (including applications), website, social media and other mobile devices-delivered support programmes to provide information and facilitate communication regarding self-management and adverse effects related to toxicities owing to breast cancer therapy, (3) All intervention study types including randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or quasi-experimental intervention studies were considered,(4) Outcome variables in the study included one of the following, such as psychological distress, anxiety and/or depression, physical variables, social support, self-efficacy and quality of life and (5) Articles were written in English or Chinese.

Studies were excluded for the following reasons: (1) If they focused on internet-based support interventions related to other types of cancer, (2) Study types include review, non-clinical study, meta-analysis and so on, (3) The full text cannot be obtained, (4) Repeated publications.

Study selection and data extraction

All stages of study selection, data extraction was conducted by two researchers independently, and disagreements were resolved by consultation with a third researcher. For included studies, the following data were extracted with a predetermined data extraction form, including study characteristics (author(s), country and year of publication), sample size, intervention characteristics and outcome characteristics. Missing data would be obtained from authors by email, if possible.

Data synthesis

The data synthesis was undertaken following CRD’s guidance(CRD:Centre for Reviews and Dissemination).49 This study follows the narrative synthesis method of Popay et al, and conducts narrative synthesis in a systematic and transparent way, focusing on the effect and content elements of intervention measures.50

Assessment of risk of bias

The quality of RCTs studies was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration’ risk of bias tool.51 This tool rates seven domains as having a low, unclear or high risk of bias. These domains consist of sequence generation, allocation concealment, participants’ and study personnel’s blinding; outcome assessment blinding; outcome data completeness; selective outcomes’ reporting; and other threats to validity, including intervention contamination, baseline imbalance and carry-over effect in cross-over trials. In addition, we used the Joanna Briggs Institute reviewer’s manual to evaluate the risk of bias of quasi-experimental studies.52 The overall quality of the quasi-experimental research is evaluated from nine items including causality, baseline, intervention, control, outcome index measurement, follow-up and analysis.

Patient and public involvement

No patient involved.

Results

Selection of studies

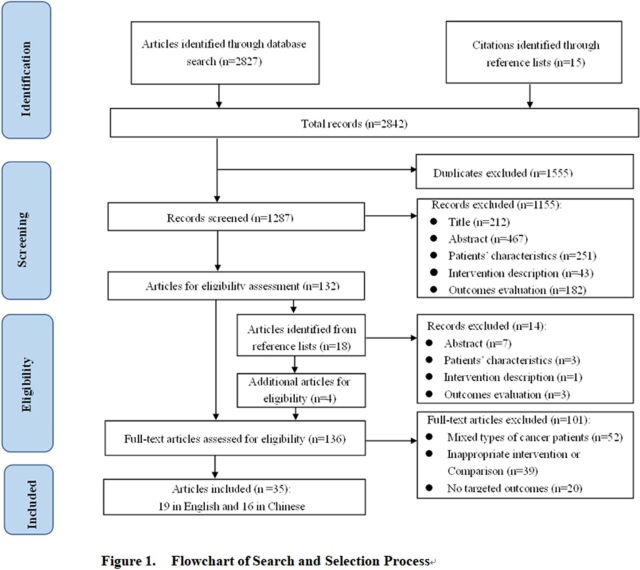

A total of 2842 references were obtained through database retrieval and reference tracing. After reading the titles and abstracts to exclude duplicates, 136 references were obtained through preliminary screening. After further reading the full text, 35 references were finally included per all inclusion and exclusion criteria established for the systematic review (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of search and selection process.

Study characteristics and risk of bias

The quality appraisal of the 35 articles is shown in tables 1 and 2, and the characteristics of the included studies are summarised in tables 3 and 4. A total of 35 articles were included in this literature review. Sixteen studies were undertaken in mainland China, six in the USA, two in the Netherlands, two in Australia, two in Sweden, one study each in Taiwan, Turkey, Switzerland, Italy, Japan, Korea and Ireland. Thirty study designs were RCTs, the other five study designs were quasi-experimental studies.

Table 1.

Risk of bias assessment tool for randomised controlled trials

| References | Item 1 | Item 2 | Item 3 | Item 4 | Item 5 | Item 6 | Item 7 |

| Lally et al 16 | + | ? | ? | ? | + | + | + |

| Zhu et al 17 | + | + | ? | + | + | + | + |

| Korkmaz et al 18 | + | ? | ? | ? | + | + | + |

| White et al 19 | + | ? | ? | ? | + | + | + |

| Admiraal et al 20 | + | + | – | – | + | + | + |

| Ventura et al 21 | + | + | ? | ? | + | + | + |

| Wheelock et al 22 | + | ? | ? | ? | + | + | + |

| Du et al 23 | + | ? | ? | ? | + | + | + |

| Hou et al 24 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Graetz et al 25 | + | + | ? | ? | + | + | + |

| Fjell et al 26 | + | + | ? | ? | + | + | + |

| Handa et al 27 | + | ? | ? | ? | + | + | + |

| Rosen et al 28 | + | – | – | – | + | + | + |

| Zhou et al 29 | + | ? | + | + | + | + | + |

| Zhou et al 30 | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + |

| Foley et al 31 | + | ? | ? | ? | + | + | + |

| Wang et al 32 | + | ? | ? | ? | + | + | + |

| Sherman et al 33 | + | ? | ? | ? | + | + | + |

| Villani et al 34 | ? | ? | ? | ? | + | + | + |

| Liu et al 35 | ? | ? | ? | ? | + | + | + |

| Kim and Kim36 | + | ? | ? | ? | + | + | + |

| Im et al 38 | + | ? | ? | + | + | + | + |

| Wang et al 39 | ? | ? | ? | ? | + | + | + |

| Visser et al 40 | ? | ? | – | – | + | + | + |

| Peng et al 41 | ? | ? | ? | ? | + | + | + |

| Chee et al 54 | + | ? | ? | + | + | + | + |

| Wang et al 57 | + | ? | ? | ? | + | + | + |

| Li et al 58 | ? | ? | ? | ? | + | + | + |

| Chen et al 59 | + | ? | ? | ? | + | + | + |

| Egbring et al 60 | + | + | ? | ? | + | + | + |

Key: ‘+’ =low risk of bias; ‘–’ =high risk of bias; ‘?’ =unclear risk of bias. Item 1: Random sequence generation; Item 2: Allocation concealment; Item 3: Blinding of participants and personnel; Item 4: Blinding of outcome assessment; Item 5: Incomplete outcome data; Item 6: Selective outcome; Item 7: Other sources of bias.

Table 2.

Risk of bias assessment tool for quasi-experimental studies

| References | Item 1 | Item 2 | Item 3 | Item 4 | Item 5 | Item 6 | Item 7 | Item 8 | Item 9 |

| Li et al 37 | Y | U | U | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y |

| Yue et al 42 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | U | Y |

| Dai and Wang53 | Y | U | U | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y |

| Zhou et al 55 | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | N | U | U | Y |

| Xu et al 56 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U |

|

Y |

Key: Y=yes, N=no, U=unclear. Item 1: Was the causal relationship in the study clearly stated?, Item 2: Was the baseline comparable between the groups?, Item 3: Were the other measures received by the groups the same, except for the intervention to be validated?, Item 4: Was a control group established?, Item 5: Were multidimensional measures of outcome indicators performed before and after the intervention?, Item 6: Was follow-up complete, and if not, were missing visits reported and measures taken to address them?, Item 7: Were the outcome indicators measured in the same way for all study groups?, Item 8: Were the measures of outcome indicators reliable?, Item 9: Were the data analysis methods appropriate?

Table 3.

Internet-based support interventions randomised controlled trials: study characteristics and results

| Author/year/country | Sample size (I/C) | Intervention description | Intervention characteristics | Intervention content elements | Duration | Outcomes/ measurements |

Results |

| Lally et al

2020 USA16 |

43/57 | Name: Tailored self-mannagement psychoeducational programme Structure: Five module of supportive oncology-based psychoeducation and cognitive-behavioural techniques, coping skills, problem solving, communication strategies and validation. |

Delivery: Web Self-guided: √ Automated reminders: × Face-to-face contact: × Tailored: √ |

Information support; Psychological support; Peer Support. |

12 weeks |

|

No significant outcomes. |

| Zhu et al

2018 China17 |

57/57 | Name: Mobile Breast Cancer e-Support Programme Structure: Learning Forum (information related to breast cancer disease and symptom management), Discussion Forum (anonymous support group), Consult an Expert (online consultation) and Personal Stories (interview stories of breast cancer survivors). |

Delivery: Application Self-guided: × Automated reminders: × Face-to-face contact: × Tailored: × |

Information support;Interaction with healthcare professionals; Peer support. |

3 months |

|

|

| Korkmaz et al

2020 Turkey18 |

24/24/ 24 |

Name: A web-based education programme Structure: Provides education or coach to patients with breast cancer in the preoperative and postoperative process. |

Delivery: Web Self-guided: √ Automated reminders: × Face-to-face contact: × Tailored: × |

Information support. | 1 month |

|

|

| White et al

2018 Australia19 |

177/202 | Name: An information- based, breast cancer specific website Structure: Information module, emotional responses, support services, family responses and life after cancer, a diary. |

Delivery: Web Self-guided: √ Automated reminders: √ Face-to-face contact: × Tailored: × |

Information support; Psychological support. |

6 months |

|

|

| Admiraal et al

2017 Netherlands20 |

69/69 | Name: Tailored self-mannagement psychoeducational programme Structure: (1) problem orientation; and (2) fully automated and customised psychoeducation for reported problems; and (3) resources and services for reported problems. |

Delivery: Web Self-guided: √ Automated reminders: × Face-to-face contact: × Tailored: √ |

Information support; Psychological support. |

12 weeks |

|

No significant outcomes. |

| Ventura et al

2017 Sweden21 |

121/105 | Name: Swedish Interactive Rehabilitation Information programme Structure: Includes links to web pages and lectures last for 4 hours about two modules: medical issues arising and psychosocial aspects. |

Delivery: A computer-based programme Self-guided: × Automated reminders: × Face-to-face contact: × Tailored: × |

Information support. | 9 months |

|

No significant outcomes. |

| Wheelock et al

2015 USA22 |

41/59 | Name: A web-based system for symptom management Structure: Three routine clinical follow-up appointments, self-reported symptoms, with review by nurse practitioners, targeted education and triage. |

Delivery: Web +computer system Self-guided:× Automated reminders: × Face-to-face contact: × Tailored: √ |

Information support; Symptom management; Interaction with healthcare professionals. |

18 months | Symptom prevalence (patients self-reported) | 7.36 vs 3.2; p=0.0045 |

| Du and Yao 2021 China23 |

40/40 | Name: Follow-up management intervention based on clinical decision support system Structure: Fills in the corresponding health status evaluation sheet, the system automatically interprets the results of the evaluation sheet and triggers an abnormal state alarm, the normal state gives a follow-up/treatment reminder, and the abnormal state pushes-related health education courses or intervention from medical staff. |

Delivery: A full-process information management system Self-guided: × Automated reminders: √ Face-to-face contact: × Tailored: √ |

Information support; Symptom management; Interaction with healthcare professionals. |

6 months |

|

|

| Hou et al

2020 Taiwan24 |

59/53 | Name: A Self-Management Support mHealth Application Intervention Structure: Eight main features (1) evidence or knowledge about breast cancer, (2) exercise and rehabilitation after surgery, (3) diet and nutrition for breast cancer patients, (4) emotional support to prevent anxiety and depression, (5) personal health records to track treatment and side effects, (6) information on social resources, (7) experience sharing and (8) expert consulting. |

Delivery: Application Self-guided: √ Automated reminders: √ Face-to-face contact: × Tailored: × |

Information support; Symptom management; Behaviour management Psychological support; Interaction with healthcare professionals; Peer support. |

3 months |

|

83.45 vs 82.23, p=0.03 (QLQ-C30); 265.53 vs 63.13, p=0.04 (QLQ-BR23) |

| Graetz et al

2018 USA25 |

25/23 | Name: A mobile application for managing adverse symptoms. Structure: Test the use of the application designed with and without weekly reminders for patients to report real-time symptoms and AI use outside of clinical visits with built-in alerts to patients’ oncology providers. |

Delivery: Application Self-guided:√ Automated reminders:√ Face-to-face contact: × Tailored:√ |

Information support Symptom management; Behaviour management. |

8 weeks | Symptom distress (FACT-ES) | No significant outcomes. |

| Fjell et al

2020 Sweden26 |

75/74 | Name: An interactive application intervention Structure: Symptom self- reporting, an alert system for contacting healthcare professionals, access to self-care advice and a visual chart of symptom history. |

Delivery: Application Self-guided: √ Automated reminders: √ Face-to-face contact: × Tailored: √ |

Information support; Symptom management; Interaction with healthcare professionals. |

2 weeks |

|

|

| Handa et al

2020 Japan27 |

52/50 | Name: A breast cancer patient support system application. Structure: Record the patient’s subjective and objective symptoms by time and number, provides tips for self-care, including advice on when the patient should go for check-ups, and ways to manage side effects. |

Delivery: Application Self-guided: √ Automated reminders: × Face-to-face contact: × Tailored: × |

Information support; Symptom management. |

12 weeks | Anxiety and depression (HADS) | No significant outcomes. |

| Rosen et al

2018 USA28 |

55/57 | Name: Application-delivered mindfulness training intervention Structure: Includes techniques for calming meditation (eg, focus on the breath) and insight meditation (eg, cultivating awareness, insight and compassion). |

Delivery: Application Self-guided:√ Automated reminders: Face-to-face contact: × Tailored × |

Information support; Psychological support. |

8 weeks |

|

t (258.40)=3.09, P<0.01, 95% CI (2.71 to 11.90) |

| Zhou et al

2019 China29 |

66/66 | Name: Cyclic adjustment training intervention Structure: Relaxed deep breath training; music listening; anticancer stories reading/ listening/watching; adjust experiences and feelings sharing with peers;be instructed to self-ask the following questions. |

Delivery: WeChat Self-guided: × Automated reminders: × Face-to-face contact: √ Tailored: × |

Information support; Psychological support; Interaction with healthcare professionals; Peer support. |

12 weeks |

|

|

| Zhou et al

2020 China30 |

55/56 | Name: WeChat-based multimodal nursing program Structure: Provision of information, training, support, and counselling centred and oriented to the needs of breast cancer patients, involving physical, psychological and social adjustment distress. |

Delivery: WeChat Self-guided: × Automated reminders: × Face-to-face contact: √ Tailored: × |

Information support; Psychological support; Interaction with healthcare professionals; Peer support. |

6 months |

|

|

| Foley et al

2016 Ireland31 |

26/13 | Name: Patient accessed tailored information Intervention Structure: Tailored surgical information pertaining to individual patients and the scripts were reviewed by the National Adult Literacy Agency and contain basic breast cancer biology, the different treatments used and surgical techniques. |

Delivery: Application Self-guided: √ Automated reminders: × Face-to-face contact: × Tailored: √ |

Information support. | 2 weeks |

|

|

| Wang et al

2019 China32 |

44/44 | Name: Continuous rehabilitation nursing support intervention Structure: Knowledge sharing, health consultations, sharing of feelings and experiences between patients, relax training; cope with negative emotions. |

Delivery: WeChat Self-guided: × Automated reminders: × Face-to-face contact: × Tailored: × |

Information support; Psychological support; Interaction with healthcare professionals; Peer support. |

6 months |

|

|

| Sherman et al

2018 Australia33 |

155/149 | Name: Structured Online Writing Exercise Intervention Structure: Individuals could describe their deepest thoughts and emotions with specific prompts focused on self-compassion according to a modified expressive writing prompt. |

Delivery: Web Self-guided:√ Automated reminders:× Face-to-face contact: × Tailored: × |

Psychological support. | NA |

|

|

| Villani et al

2018 Italy34 |

14/15 | Name: E-health Stress Inoculation Training (SIT) intervention Structure: Face-to-face counselling with a psychologist, live videos simulating the chemotherapy process, watching live video interviews with women who have experienced breast cancer, relaxation videos with guided meditation audio. |

Delivery: Web Self-guided: × Automated reminders:× Face-to-face contact:√ Tailored: × |

Psychological support; Interaction with healthcare professionals; Peer support. |

3 months |

|

|

| Liu et al 2019 China35 |

50/50 | Name: Innovative Follow-Up Intervention Structure: Provide preoperative rehabilitation guidance, discharge follow-up form and endocrine medication survey form, health consultation. |

Delivery: WeChat Self-guided: × Automated reminders: × Face-to-face contact: × Tailored: × |

Information support; Behaviour management; Interaction with healthcare professionals; Peer support. |

12 months | Self-efficacy (GSES) | P<0.05 |

| Kim and Kim 2020 North- Korea36 |

Name: A web-based expert support self-management programme (WEST) Structure: Keep a health diary, self-diagnose lifestyle, learn health information and receive individualised feedback from a nurse, phone counselling with experts. |

Delivery: Application Self-guided: √ Automated reminders: × Face-to-face contact: × Tailored: √ |

Information support; Behaviour management; Interaction with healthcare professionals. |

6 months | Self-efficacy (health-specific self-efficacy scales) |

No significant outcomes. | |

| Im et al

2020 USA38 |

66/49 | Name: Technology-Based Information and Coaching/ Support Programme on Pain and Symptoms Structure: Online knowledge or education with cultural characteristics, online assistance resources, group and one-on-one guidance in the form of online forums on the website. |

Delivery: Web Self-guided: × Automated reminders: × Face-to-face contact: × Tailored: √ |

Information support; Interaction with healthcare professionals; Peer support. |

3 months |

|

P=0.0229 |

| Wang et al

2019 China39 |

75/74/\ | Name: Specialised case management intervention Structure: Establish case management files, push the answers to patient questions, share knowledge, remind and supervise the implementation of the patient’s personal plan daily, including medication, symptoms, and weight. |

Delivery: WeChat Self-guided: × Automated reminders: × Face-to-face contact: × Tailored: × |

Information support; Interaction with healthcare professionals; Peer support. |

9 months | Symptom severity (CTCAE) | P<0.05 |

| Visser et al

2018 Netherlands40 |

50/59 | Name: Group medical consultations (GMCs) and tablet-based online support group sessions Structure: A face-to-face GMC and an online application, consisting of three tablet-based video GMCs, email, videos and additional information. |

Delivery: Application Self-guided: × Automated reminders:√ Face-to-face contact: × Tailored: √ |

Information support; Interaction with healthcare professionals; Peer support. |

3 months |

|

No significant outcomes. |

| Peng et al 2020 China41 |

59/58 | Name: Online and offline rehabilitation intervention Structure: online and offline rehabilitation volunteer support activities, case management file establishment and offline rehabilitation guidance, online rehabilitation knowledge guidance and rehabilitation consultation and Q&A. |

Delivery: WeChat Self-guided: × Automated reminders: × Face-to-face contact: √ Tailored: × |

Information support; Psychological support; Interaction with healthcare professionals; Peer support. |

12 months |

|

|

| Chee et al

2016 USA54 |

30/35 | Name: A culturally tailored internet cancer support group Structure: (a) interactive online message board by moderated a registered nurse; (b) interactive online evidence-based educational sessions; and (c) online resources. |

Delivery: Web Self-guided: × Automated reminders: × Face-to-face contact: × Tailored: × |

Information support; Interaction with healthcare professionals; Peer support. |

1 month |

|

|

| Wang et al 2017 China57 |

320/ 318/ |

Name: Continuous nursing intervention Structure: Regularly provides the service like medical information, care reminders, health monitoring and health education. |

Delivery: Application Self-guided: × Automated reminders: × Face-to-face contact: × Tailored: × |

Information support; Symptom management; Interaction with healthcare professionals; Peer support. |

2 weeks |

|

|

| Li and Hanping 2018 China58 |

60/60 | Name: Management of chemotherapy adverse events Structure: Information support, alert for chemotherapy adverse events, personalised management from a case manager or multidisciplinary expert, SMS alert feedback. |

Self-guided: √ Automated reminders: √ Face-to-face contact: × Tailored: √ |

Information support; Symptom management; Interaction with healthcare professionals. |

2 weeks |

|

|

| Chen et al

2015 China59 |

45/45 | Name: Tracking intervention based on network information platform Structure: Through the system, follow-up nurses participate in the diagnosis and treatment process of the patient during the hospitalisation process, provide post-discharge patient greetings, rehabilitation guidance, reminders for follow-up and other nursing services. |

Delivery: Web Self-guided: × Automated reminders: √ Face-to-face contact: √ Tailored: × |

Information support; Interaction with healthcare professionals Peer support. |

3 months |

|

|

| Egbring et al

2016 Switzerland60 |

46/49/ 44 |

Name: A mobile and web-based application to record daily functional activity and adverse events. Structure: Record functional activity and adverse events, and collaborate with physicians in the monitoring and review of patient-reported symptoms. |

Delivery: Application Self-guided: √ Automated reminders: × Face-to-face contact: × Tailored: × |

Information support; Symptom management; Interaction with healthcare professionals. | 42 days | Symptom prevalence (patients self-reported) |

n=1033 (supervised application group) vs n=656 (questionnaire group). |

BIS, Body Image Scale; CBI, Cancer Behavior Inventory; CES-D, Center for Epidemiological Survey-Depression Scale; CTCAE, Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events; DASS, Depression Anxiety Stress Scale; EESS, Eysenck Emotional Stability Scale; EORTC, The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer; ERQ, The Emotion Regulation Questionnaire; FACT-B, Functional Assessment of Cancer Treatment-B; GSES, General Self-Efficacy Scale; HADS, The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; MSAS-SF, The Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale–Short Form; NRS, Numerical Rating Scale; PRQ, Personal Resource Questionnaire; QLQ, quality of life questionnaire; QLSBC, quality of life scale of beast cancer; SAS, Self-Rating Anxiety Scale; SCL, Symptom Checklist; SDS, Self-Rating Depression Scale; SICPA, Stanford Inventory of Cancer Patient Adjustment; SMS, short message service; STAI, The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; SUPPH, Strategies Used by People to Promote Health.

Table 4.

Internet-based support interventions quasi-experiment studies: study characteristics and results

| Author/year/ country | Sample size (I/C) |

Intervention description | Intervention characteristics | Intervention content elements | Duration | Outcomes/ measurements |

Results |

| Li et al, 201737

China |

48/58 | Name: Continuous nursing intervention Structure: Includes three sections: Rehabilitation Encyclopedia, Personal Center and Q&A. Rehabilitation Encyclopedia, including diet, exercise, sleep, drugs, psychology and other rehabilitation knowledge. Personal centre records patient health files. |

Delivery: WeChat Self-guided: × Automated reminders: × Face-to-face contact: × Tailored: √ |

Information support; Behaviour management; Interaction with healthcare professionals Peer support. |

4 weeks |

|

|

| Yue et al, 202042

China |

148/146 | Name: ‘Internet +’ nursing mode intervention Structure: ‘Music Oxygen Bar’ group activities, case managers tailor-made family rehabilitation plan for patients, weChat provides postoperative rehabilitation knowledge and video, medical consultation, Healing Music and social support. |

Delivery: WeChat Self-guided: × Automated reminders: × Face-to-face contact: × Tailored: × |

Information support; Interaction with healthcare professionals; Peer support. |

12 months | Lymphoedem symptom distress and severity (BCLE-SEI) | P<0.05 |

| Dai et al, 201755

China |

47/42 | Name: Intervention based on nurse–patient communication platform Structure: Knowledge sharing, health counselling and one-on-one chat (responsible nurse communicates with 3–5 patients via personal WeChat ID). |

Delivery: WeChat Self-guided: × Automated reminders: × Face-to-face contact: × Tailored: × |

Information support; Interaction with healthcare professionals; Peer support. |

6 months |

|

|

| Zhou et al, 201957

China |

153/145 | Name: Hospital–family collaborative transitional care intervention Structure: Provides breast cancer postoperative function exercise method video, rehabilitation knowledge, health lecture activities and expert consultation activities notice, outpatient doctor sitting arrangements daily, shift. |

Delivery: WeChat Self-guided: × Automated reminders: × Face-to-face contact: × Tailored: × |

Information support; Interaction with healthcare professionals; Peer support. |

6 months |

|

|

| Zhou et al, 201957

China |

Nurses conduct WeChat group visits. | ||||||

| Xu et al, 201758

China |

75/75 | Name: An internet and mobile phone-based case management programme Structure: Mobile internet technology is applied to postoperative case management in patients with breast cancer in education, follow-up and remote consultation. |

Delivery: Application +WeChat Self-guided: × Automated reminders: × Face-to-face contact: × Tailored: × |

Information support; Symptom management; Interaction with healthcare professionals. |

2 months |

|

1. P<0.05 2. No significant outcomes. |

BCLE-SEI, Breast Cancer and Lymphedema Symptom Experience Index; BFI, Brief Fatigue Inventory; BIS, 10-item Body Image Scale; BIS, Body Image Scale; CBI, Cancer Behavior Inventory; CES-D, Center for Epidemiological Survey-Depression Scale; CTCAE, Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events; DASS-21, The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21item; EESS, Eysenck Emotional Stability Scale; EORTC QLQ-C30, The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer quality of life questionnaire-core 30; ERQ, The Emotion Regulation Questionnaire; FACT-B, Functional Assessment of Cancer Treatment-B; FACT-ES, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Endocrine Symptoms; GSES, General Self-Efficacy Scale; HADS, The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HAMA, Hamilton Anxiety Scale; HAMD, Hamilton Depression Scale; I, intervention group; I/C:C, control group; MDASI, MD Anderson Symptom Inventory; MSAS-SF, The Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale–Short Form; NA, not available; NRS, Numerical Rating Scale; PRQ, Personal Resource Questionnaire; QLQ-BR23, The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer quality of life questionnaire-breast cancer module 23; QLSBC, quality of life scale of beast cancer; SAS, Self-Rating Anxiety Scale; SCL-90, the Symptom Checklist-90; SDS, Self-Rating Depression Scale; SICPA, Stanford Inventory of Cancer Patient Adjustment; STAI, The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; SUPPH, Strategies Used by People to Promote Health.

The delivery modes of internet-based support intervention include website platform (n=9), mobile application programme (n=13), WeChat platform (n=11), a full-process information management system (n=1), a web-based computer system (n=1), a computer-based programme (n=1). There are 12 articles on tailored interventions.

Description of participants

The 35 studies consisted of 5368 patients. The participant sample sizes ranged from 29 to 638 participants. The mean ages ranged from 41.1~59.9 years. Seven studies analysed patients with locally or locally advanced cancer (stages I–III), whereas three studies only included patients with cancer with stages I–II.16 21 53 Five studies included solely patients who had completed cancer treatment during their follow-up,17 28 29 36 40 27 studies only included patients during treatment and 4 studies patients in all treatment phases.28 38 40 54

Content elements of internet-based support intervention internet-based support

Internet-based support intervention contained six elements: (1) Information support (n=33)16–32 35–42 53–60 : including breast cancer disease and treatment knowledge, self-management strategies for physical symptoms and recovery, available aid resources or organisational service information, expert consultation or outpatient consultation arrangements and expert lectures. (2) Symptom management (n=10)22–27 56–58 60: including patients’ self-assessment and monitoring of their physiological symptoms, medical staff’s self-management guidance for patients, automatic feedback of symptom management application or system and symptom early warning processing combined with clinical risk algorithm. (3) Behaviour management (n=5)24 25 35–37: including medication compliance management, limb functional exercise compliance management, infusion port maintenance, healthy lifestyle management. (4) Psychological support (n=11)16 19 20 24 28–34: divided into self-guided and professional guidance/support. Self-guided psychological support is realised by the corresponding modules of intervention independently completed by patients with breast cancer. Professionally guided psychological support is conducted through email interaction with the therapists or online interaction with groups of other patients with breast cancer. It includes negative emotional self-assessment or monitoring, cognitive behavioural therapy, mindfulness training, expressive writing to alleviate physical image distress, psychological education, cognitive behavioural therapy and so on. (5) Interaction with healthcare professionals (n=25)17 22–24 26 29 30 32 34–42 53–60: The main form is that patients with breast cancer directly contact with health professionals and ask questions, health professionals give advice or emotional support to patients with breast cancer. (6) Peer support (n=20)16 17 24 29–32 34 35 37–42 53–55 57 59: Support information, emotional support and rehabilitation experience sharing are mainly provided by other patients with breast cancer.

Intervention providers were mainly nurses or physicians, a few multidisciplinary teams24 55 56 brought together by physicians, nurses, dietitians, physiatrists, psychotherapists and information engineers. In terms of intervention sample size, due to the study conditions, most of the interventions were conducted in small samples, with single-group sample sizes mostly concentrated in 30–60 individuals, and only six studies20 26 29 38 39 56 with sample sizes of 61–100, and only seven studies19 21 33 39 42 55 57 with sample sizes of more than 100, while only three studies25 31 34 with sample sizes of less than 30.

Based on the duration of intervention, 22 intervention studies focused on the period from breast cancer diagnosis to radiotherapy and chemotherapy, and the duration of intervention was mostly 3–6 months.16 17 19 23 24 27 29 30 32 34 53 55 59 Only two studies21 39 lasted 9 months, while the intervention duration of the other seven studies18 31 37 56–58 60 ranged from 2 weeks to 8 weeks.

Interventions and associated outcomes

In this systematic review, the internet-based support interventions were evaluated for their effectiveness on quality of life, anxiety and/or depression, psychological distress, physical variables, social support and self-efficacy. The measurement scales are shown in tables 3 and 4.

Quality of life

Eighteen studies reported on quality of life with significant positive intervention effects reported by 17.17–19 24 26 28 30 32 34 37 41 53–59 In seven RCTs and four quasi-experimental studies conducted in China, the quality of life score of the intervention group was higher than that of the control group. 17 29 30 32 37 41 57-61 A web-based tailored psychoeducational intervention for patients with breast cancer who completed curative-intent primary treatment reported that improvements in distress, distress-related problems (practical, family/social, emotional, religious/spiritual and physical problems) and quality of life were observed in both study groups but no significant differences.20

Anxiety and/or depression

Eleven studies found inconsistent results regarding the impact of the internet-based support interventions on symptoms of anxiety and/or depression. The results of six RCTs and one quasi-experimental study included in this review showed that internet-based support interventions significantly improved anxiety and depression in patients with breast cancer.18 29 33 34 37 57 59 The limitations of other studies may explain the insignificant effects of the intervention, such as short follow-up time,27 31 under-representation of the research subjects,19 the lack of human-computer interaction in the system,21 the average level of anxiety and depression among participants at baseline was within the normal range for non-clinical samples.

Psychological distress

Five studies reported inconsistent results concerning the effectiveness of internet-based support interventions on psychological distress. In an RCT study of online expressive writing focused on self-compassion, participants in the intervention group reported significantly less body image-related distress and greater body appreciation than only expressive writing participants in the control group.33 In one pre-test/post-test design, which findings supported the positive effects of the Internet Cancer Support Group on psychological symptoms.54 In the other three RCTs concerning psychological education and group medical consultation, patients in the intervention group reported lower scores of psychological distress than the control group, but this difference was not significant.16 20 40

Physical variables

Seventeen studies reported on physical variables, including the prevalence, severity and distress from physical symptoms. All except two studies30 56 which was conducted in China showed positive significant intervention effects. In five non-randomised studies and four RCT studies conducted in China, patients in the intervention group reported significantly improved symptoms of lymphoedema,42 55 body image distress,41 fatigue symptoms,37 39 nausea and vomiting and other gastrointestinal discomfort symptoms,39 53 58 postoperative complications56 and the prevalence of adverse drug reaction.57 In the other six studies, three of them are RCTs,17 22 60 and the other two are randomised pre-test/post-test designs,38 54 symptom distress was significantly lower in the intervention group, and there was a trend toward lower symptom severity and symptom prevalence. In a pilot RCT in USA,25 Symptom burden increase was higher for the application group compared with the application +reminder group but did not reach statistical significance. In an RCT study in Sweden, an interactive application-based symptom management intervention significantly reduced the prevalence of nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite and constipation during neoadjuvant chemotherapy.26

Social support

Two studies showed that the online interventions did not significantly improve patients’ social support. In one RCT, internet-based support intervention did not significantly change social support relative to the effect of usual care alone at 3 months.17 However, the longer women used the internet-based support programme, the higher women perceived social support. One study focused on online support groups did not significantly improve patient perceived social support, which effectiveness appeared influenced by other factors, such as socio-demographic background and disease.54

Self-efficacy

Self-efficacy was reported in six studies, of which three studies had significant positive intervention effects on it. In three RCTs conducted in China, concerning a breast cancer e-support programme,17 a full-process information management system for patients with breast cancer based on clinical decision support23 and follow-up of innovative approaches based on WeChat platform,35 the intervention groups reported improved self-efficacy than control groups. In the other three RCTs, regarding a web-based expert support self-management programme,36 a computer-based educational programme,21 and the Internet Cancer Support Group,54 participants in the two groups showed no significant differences in self-efficacy.

Discussion

This review examines the effectiveness of internet-based support interventions for various health outcomes in patients with breast cancer. Due to the rapid growth of online interventions in this group in recent years, this review focuses on studies published over the past 5 years. A total of 35 studies were identified.

In the research field of supporting and caring for breast cancer, the content elements of internet intervention include information support, symptom management, behaviour management, psychological support, contact with medical staff and peer support. In some studies, information support or psychological support is provided to patients with breast cancer only through internet intervention.18 31 33 However, in addition to providing information support or psychological support, most studies also provide comprehensive interventions such as symptom management, peer support and interaction with medical staff. Patients with breast cancer believe peer support40 61 or interacting with professionals17 20 21 36 60 is more useful than simply providing care information or psychological support. This suggests that multielement internet-based support interventions are favoured by patients with breast cancer.

In addition, some studies based on evidence-based self-help intelligent information technology system can provide personalised customised information for patients, reduce the information burden unrelated to specific diagnosis or cancer stage, and to some extent solve the information limitation caused by the imbalance of health resources in various regions.16 19 20 23 26 27 37 58 In the future, it is necessary to organise multidisciplinary teams to develop elements and programmes for personalised assessment and comprehensive intervention of internet support interventions, and to involve patients with breast cancer from end users in the process of intervention research and development. Based on the current situation of uneven resources of experts in various regions, the research and development of intelligent decision-making system can be explored to realise the customisation and recommendation of personalised schemes.

For patients who prioritise the use of the internet to meet the information and support needs, adding face-to-face contact interventions may be insignificant and have little impact on outcomes. For patients who prioritise face-to-face contact as a source of information and support, adding face-to-face contact into internet intervention research may be important, but this may reduce the explanatory power of the intervention effect of internet intervention research itself.21

The optimal duration of internet-based support interventions remains to be explored. The limited duration of follow-up for internet-based interventions hinders the long-term effects of such internet-based support interventions. Most of the studies included in this review were followed-up for no more than 6 months, and only five studies were followed-up for 9, 12 or 18 months.21 22 35 39 41 In current and future studies, there is a need to extend the periodicity and follow-up of the internet support intervention to explore whether this intervention has long-term benefits for breast cancer. In addition, the charging and sustainability of the internet support platform should be considered in the integration into the daily care of patients and needs to be further explored.

Quality of life is a major prognostic indicator for patients with breast cancer, as diagnosis and treatment often result in significantly impaired quality of life.4 Modern oncology disciplines unanimously believe that the quality of life of patients with cancer is more representative of the cure effect and recovery status of the patient than the survival period and mortality rate.62 Overall, internet-based support interventions can improve the quality of life of patients with breast cancer. Only one study does not support this view,20 and the study was a web-based tailored psychoeducational programme. Patients were not guided throughout all the problem solving therapy phases and may have been exposed too little to the content of the programme to solicit any observable effect, which were their explanation for why their intervention may not have significantly impacted quality of life.20 On the one hand, the reason may be that the intervention content of this study is unitary, and only psychological and information intervention is carried out. The measurement standard of quality of life includes many aspects such as physiology, psychology and society, and is affected by many factors. On the other hand, affected by the differences in ethnic culture, people in different regions will have differences even if they use the same measurement scale.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network63 currently defines ‘psychological distress’ as an unpleasant emotional experience of psychological, social and/or spiritual nature caused by multiple factors, which can further aggravate physical symptoms, impact treatment compliance and quality of life. The negative emotions of patients with cancer are affected by many factors, such as disease cognition, social support and physiological status. The results of this review show that the effect of internet-based support intervention on reducing negative emotions of patients with breast cancer is still controversial. It is suggested that future research needs to further analyse the promotion and obstacle factors of internet psychological support intervention, and explore improvement strategies to better implement and promote network intervention.21 31 40

This review included 17 studies that reported indicators related to physical symptoms. Eight studies focused on the alleviation of physical symptoms distress in patients with breast cancer, and the other eight studies focused on the severity of physical symptoms in patients. Few studies focused on the changes of other measurement indicators, such as the prevalence or number of physical symptoms. Indeed, the goal of symptom management is not necessarily to prevent symptoms, but to reduce their severity and impact on psychological distress and quality of life. Kearney et al 64 reported that monitoring and reporting of symptoms may also manifest as an increase in symptom severity depending on the time of assessment or patient self-report, better reflecting actual symptom burden and providing a clearer target for intervention.

Lack of social support for patients with chronic diseases including breast cancer is associated with poor emotional health, increased depressive symptoms and poor quality of life.65 Besides, studies also have shown that improving self-efficacy can promote behaviour change, improve self-management ability, quality of life and confidence in coping with illness.66 Although social support and self-efficacy are important factors affecting the quality of life of patients with breast cancer, this review found that the effect of internet-based support intervention on these two measurement indicators is still controversial, which needs further discussion in future research.

Limitations

First, due to language restrictions, only published literature in Chinese and English from this review. Second, this review focused on only six health outcomes to test the effectiveness of internet-based interventions; therefore, the amount of literature selected may have been reduced. To obtain a more comprehensive picture, future reviews could include other health outcomes such as supportive care needs, satisfaction with cancer treatment, and decision conflict/distress. Again, the heterogeneity of the included studies in terms of sample and methodology, the different age and tumour stages of the study population, the differences in the content, modality, frequency and duration of the interventions adopted by the studies, and the different measurement tools for the same outcome indicators did not lend themselves to a combined study; therefore, this review is only a descriptive study of the findings. Finally, some of the studies included in this review had small sample sizes.25 31 34 The insignificant impact may be due to a lack of statistical power rather than a true intervention nullification.

Conclusion

The results of this review suggest that internet-based support intervention can have a positive effect on patients with breast cancer, and can effectively improve the quality of life of patients. However, the effect of internet-based support intervention on patients’ physical symptoms, social support, self-efficacy, anxiety, depression and other negative emotions is still controversial, which is worthy of further discussion in future intervention studies. In the future, it is necessary to standardise internet-based support interventions (content, form, frequency, duration), formulate a unified evaluation index system, design larger sample, multicentre RCTs, and further explore the long-term intervention effect of internet-based support nursing on patients with breast cancer. Medical professionals can combine the existing or new internet-based interventions with the clinical nursing path of patients with breast cancer and their daily life self-management to improve the quality of life among patients with breast cancer. With the participation of multidisciplinary teams and patients with breast cancer, the research and development of intelligent decision-making system is explored to realise the customisation and recommendation of personalised intervention programmes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank patients with breast cancer and health professionals’ involvement and their input on the study design.

Footnotes

Contributors: JS was responsible for all aspects of the study including conception of the idea, acquisition of funding, recruitment of the author team and guarantor.YH and QL: study design, data collection and analysis, drafting and revising the manuscript. FZ: supervision of study design, data collection and analysis, revising the manuscript. JS: supervision of study design, data collection and analysis, revising the manuscript.

Funding: This study is supported by The Natural Science Foundation of the Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions of China, No. 18KJA320013.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin 2017;67:7–30. 10.3322/caac.21387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021;71:209–49. 10.3322/caac.21660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Desantis CE, Ma J, Gaudet MM. Ca: a cancer Journal for clinicians. Breast cancer 2019;69. 10.3322/caac.21583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Khan F, Amatya B, Pallant JF, et al. Factors associated with long-term functional outcomes and psychological sequelae in women after breast cancer. Breast 2012;21:314–20. 10.1016/j.breast.2012.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mehnert A, Koch U. Prevalence of acute and post-traumatic stress disorder and comorbid mental disorders in breast cancer patients during primary cancer care: a prospective study. Psycho-Oncol 2007;16:181–8. 10.1002/pon.1057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gorini A, Mazzocco K, Gandini S, et al. Development and psychometric testing of a breast cancer patient-profiling questionnaire. Breast Cancer 2015;7:133–46. 10.2147/BCTT.S80014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bouma G, Admiraal JM, de Vries EGE, et al. Internet-Based support programs to alleviate psychosocial and physical symptoms in cancer patients: a literature analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2015;95:26–37. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fiszer C, Dolbeault S, Sultan S, et al. Prevalence, intensity, and predictors of the supportive care needs of women diagnosed with breast cancer: a systematic review. Psycho-Oncol 2014;23:361–74. 10.1002/pon.3432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Smith A, Hyde YM, Stanford D. Supportive care needs of cancer patients: a literature review. Palliat Support Care 2015;13:1013–7. 10.1017/S1478951514000959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lou Y, Yates P, McCarthy A, et al. Fatigue self-management: a survey of Chinese cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. J Clin Nurs 2013;22:1053–65. 10.1111/jocn.12174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen YY, Guan BS, Li ZK, et al. Effect of telehealth intervention on breast cancer patients' quality of life and psychological outcomes: a meta-analysis. J Telemed Telecare 2018;24:157–67. 10.1177/1357633X16686777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jansen F, van Uden-Kraan CF, van Zwieten V, et al. Cancer survivors' perceived need for supportive care and their attitude towards self-management and eHealth. Support Care Cancer 2015;23:1679–88. 10.1007/s00520-014-2514-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Van de Poll-Franse LV, Van Eenbergen MCHJ. Internet use by cancer survivors: current use and future wishes. Support Care Cancer 2008;16:1189–95. 10.1007/s00520-008-0419-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cruz FOAM, Vilela RA, Ferreira EB, et al. Evidence on the use of mobile Apps during the treatment of breast cancer: systematic review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2019;7:e13245. 10.2196/13245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fridriksdottir N, Gunnarsdottir S, Zoëga S, et al. Effects of web-based interventions on cancer patients' symptoms: review of randomized trials. Support Care Cancer 2018;26:337–51. 10.1007/s00520-017-3882-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lally RM, Kupzyk KA, Bellavia G, et al. CaringGuidance™ after breast cancer diagnosis eHealth psychoeducational intervention to reduce early post-diagnosis distress. Support Care Cancer 2020;28:2163–74. 10.1007/s00520-019-05028-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhu JM, Ebert L, Liu XY. Mobile breast cancer e-Support program for Chinese women with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy (Part 2): multicenter randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018;6:e104. 10.2196/mhealth.9438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Korkmaz S, Iyigun E, Tastan S. An evaluation of the influence of web-based patient education on the anxiety and life quality of patients who have undergone mammaplasty: a randomized controlled study. J Cancer Educ 2020;35:912–22. 10.1007/s13187-019-01542-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. White V, Farrelly A, Pitcher M, et al. Does access to an information-based, breast cancer specific website help to reduce distress in young women with breast cancer? results from a randomised trial. Eur J Cancer Care 2018;27:e12897. 10.1111/ecc.12897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Admiraal JM, van der Velden AWG, Geerling JI, et al. Web-based tailored psychoeducation for breast cancer patients at the onset of the survivorship phase: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017;54:466–75. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ventura F, Sawatzky R, Öhlén J, et al. Challenges of evaluating a computer-based educational programme for women diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Cancer Care 2017;26. 10.1111/ecc.12534. [Epub ahead of print: 24 06 2016]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wheelock AE, Bock MA, Martin EL, et al. SIS.NET: a randomized controlled trial evaluating a web-based system for symptom management after treatment of breast cancer. Cancer 2015;121:893–9. 10.1002/cncr.29088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Du P, Zhou Z, Lu Y. Application and effectiveness evaluation of clinical decision support in breast cancer follow-up management. Chinese Nursing Management 2021;21:110–5. 10.3969/j.issn.1672-1756.2021.01.024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hou IC, Lin HY, Shen SH, et al. Quality of life of women after a first diagnosis of breast cancer using a self-management support mHealth APP in Taiwan: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2020;8:e17084. 10.2196/17084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Graetz I, McKillop CN, Stepanski E, et al. Use of a web-based APP to improve breast cancer symptom management and adherence for aromatase inhibitors: a randomized controlled feasibility trial. J Cancer Surviv 2018;12:431–40. 10.1007/s11764-018-0682-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fjell M, Langius-Eklöf A, Nilsson M, et al. Reduced symptom burden with the support of an interactive app during neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer - A randomized controlled trial. Breast 2020;51:85–93. 10.1016/j.breast.2020.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Handa S, Okuyama H, Yamamoto H, et al. Effectiveness of a smartphone application as a support tool for patients undergoing breast cancer chemotherapy: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Breast Cancer 2020;20:201–8. 10.1016/j.clbc.2020.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rosen KD, Paniagua SM, Kazanis W, et al. Quality of life among women diagnosed with breast cancer: a randomized waitlist controlled trial of commercially available mobile app-delivered mindfulness training. Psycho-Oncol 2018;27:2023–30. 10.1002/pon.4764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhou K, Li J, Li X. Effects of cyclic adjustment training delivered via a mobile device on psychological resilience, depression, and anxiety in Chinese post-surgical breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2019;178:95–103. 10.1007/s10549-019-05368-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhou K, Wang W, Zhao W, et al. Benefits of a WeChat-based multimodal nursing program on early rehabilitation in postoperative women with breast cancer: a clinical randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud 2020;106:103565. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Foley NM, O'Connell EP, Lehane EA, et al. PATI: patient accessed tailored information: a pilot study to evaluate the effect on preoperative breast cancer patients of information delivered via a mobile application. Breast 2016;30:54–8. 10.1016/j.breast.2016.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang W, Zhou KN, et al. Effect of Internet-based continuous rehabilitation nursing support on health-related quality of life in postoperative chemotherapy patients with breast cancer. Chin Nurs Res 2019;33:1821–6. 10.12102/j.issn.1009-6493.2019.11.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sherman KA, Przezdziecki A, Alcorso J, et al. Reducing body Image-Related distress in women with breast cancer using a structured online writing exercise: results from the my changed body randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:1930–40. 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.3318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Villani D, Cognetta C, Repetto C, et al. Promoting emotional well-being in older breast cancer patients: results from an eHealth intervention. Front Psychol 2018;9:2279. 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liu Y, Liu SY, Feng DD. Effect of an innovative follow-up technique on improving the resilience and self-efficacy in patients with breast cancer during endocrine therapy(article in Chinese). J China Med Univ 2019;48:85–6. 10.12007/j.issn.0258-4646.2019.01.019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kim HJ, Kim HS. Effects of a web-based expert support self-management program (West) for women with breast cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Telemed Telecare 2020;26:433–42. 10.1177/1357633X19850386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Li L, Wu M, SJ L. Influence of continuous intervention of WeChat on cancer related fatigue and negative emotion in patients after breast cancer operation. Chin Nurs Res 2017;031:4675–7. 10.3969/j.issn.1009-6493.2017.36.024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Im EO, Kim S, Yang YL, et al. The efficacy of a technology-based information and coaching/support program on pain and symptoms in Asian American survivors of breast cancer. Cancer 2020;126:670–80. 10.1002/cncr.32579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wang ZJ, Lin ZJ, HX M. Application effect of specialized case management based on WeChat mobile platform in extended service of breast cancer patients. Chin Nurs Res 2019;33:524–7. 10.12102/j.issn.1009-6493.2019.03.043 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Visser A, Prins JB, Jansen L, et al. Group medical consultations (GMCs) and tablet-based online support group sessions in the follow-up of breast cancer: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Breast 2018;40:181–8. 10.1016/j.breast.2018.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Peng CE, Li Z, Mao HX. Effect of online and offline rehabilitation intervention on upper limb function and body image of patients with breast reconstruction after breast cancer surgery. J Nurs Manag 2020;20:1637–42. 10.3969/j.issn.1672-1756.2020.11.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yue CL, HP X, Sun L. The application effect of"Internet +" nursing mode intervention on lymphedema among postoperative patients with breast cancer. Chinese Nursing Management 2020;20:670–6. 10.3969/j.issn.1672-1756.2020.05.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Steel JL, Geller DA, Kim KH, et al. Web-Based collaborative care intervention to manage cancer-related symptoms in the palliative care setting. Cancer 2016;122:1270–82. 10.1002/cncr.29906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Van den Berg SW, Gielissen MFM, Custers JAE, et al. BREATH: Web-Based Self-Management for Psychological Adjustment After Primary Breast Cancer--Results of a Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:2763–71. 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.9386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zhu JM, Ebert L, Wai-Chi Chan S. Integrative review on the effectiveness of Internet-based interactive programs for women with breast cancer undergoing treatment. Oncol Nurs Forum 2017;44:E42–54. 10.1188/17.ONF.E42-E54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Willems RA, Bolman CAW, Mesters I, et al. Short-Term effectiveness of a web-based tailored intervention for cancer survivors on quality of life, anxiety, depression, and fatigue: randomized controlled trial. Psycho-Oncol 2017;26:222–30. 10.1002/pon.4113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Fang SY, Wang YL, Lu WH, et al. Long-Term effectiveness of an E-based survivorship care plan for breast cancer survivors: a quasi-experimental study. Patient Educ Couns 2020;103:549–55. 10.1016/j.pec.2019.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. WHO . World cancer report; 2020. https://wwwiarcfr/cards_page/world-cancer-report/

- 49. Khan KS, Ter Riet G, Glanville J. Undertaking systematic reviews of research on effectiveness: CRD’s guidance for carrying out or commissioning reviews NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A. A product from the ESRC methods programme version. In: Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews, 2006: 1–92. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011;343:d5928. 10.1136/bmj.d5928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Institute TJB . The Joanna Briggs Institute reviewer’s manual. edition. Australia: The Joanna Briggs Institute, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Dai SJ, Wang HY. Application of WeChat-assisted nurse-patient communication in young and middle-aged breast cancer patients after surgery. J Nurs Sci 2017;32:98–100. 10.3870/j.issn.1001-4152.2017.14.098 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Chee W, Lee Y, Im E-O, et al. A culturally tailored Internet cancer support group for Asian American breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled pilot intervention study. J Telemed Telecare 2017;23:618–26. 10.1177/1357633X16658369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Huimin Z. Effect of WeChat supported hospital-family collaborative transitional care on postoperative functional recovery in breast cancer patients. J Nurs Sci 2019;34:63–6. 10.3870/j.issn.1001-4152.2019.02.063 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56. HP X, Wang S, Sun RP. Chinese nursing management. In: Internet and mobile technology use in case management among breast cancer patients after surgery, 2017: 1540–4. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lu W, Jie Z, Wen D. Feasibility analysis and clinical practice in the postoperative nursing care of breast cancer patients with chemotherapy after discharge by applying APP service platform of mobile phone. Journal of Qilu Nursing 2016;22:22–4. 10.3969/j.issn.1006-7256.2016.06.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58. XY L, Chen YY, Shi HP. The effects of alert system for chemotherapy adverse events among breast cancer patients. Chinese Journal of Nursing 2018;53:1338–42. 10.3761/j.issn.0254-1769.2018.11.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Chen Y, Chen LJ, Huang YF. Effect of the tracking intervention based on network information platform on quality of life for breast cancer survivors after surgery. Journal of Nursing Science 2015;30:8–10. 10.3870/j.issn.1001-4152.2015.24.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Egbring M, Far E, Roos M, et al. A mobile APP to stabilize daily functional activity of breast cancer patients in collaboration with the physician: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Med Internet Res 2016;18:e238. 10.2196/jmir.6414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Beatty L, Binnion C, Kemp E, et al. A qualitative exploration of barriers and facilitatorsto adherence to an online self-help intervention for cancer-related distress. Support Care Cancer 2017;25:2539–48. 10.1007/s00520-017-3663-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) . Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet 2005;365:1687–717. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66544-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. National Comprehensive Cancer Network . Distress management. clinical practice guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2003;1:344–74. 10.6004/jnccn.2003.0031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kearney N, McCann L, Norrie J, et al. Evaluation of a mobile phone-based, advanced symptom management system (ASyMS) in the management of chemotherapy-related toxicity. Support Care Cancer 2009;17:437–44. 10.1007/s00520-008-0515-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Wells AA, Gulbas L, Sanders-Thompson V, et al. African-American breast cancer survivors participating in a breast cancer support group: translating research into practice. J Cancer Educ 2014;29:619–25. 10.1007/s13187-013-0592-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Chen Z, Zhang C, Fan G. Interrelationship between interpersonal interaction intensity and health self-efficacy in people with diabetes or prediabetes on online diabetes social platforms: an in-depth survey in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17. 10.3390/ijerph17155375. [Epub ahead of print: 26 07 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-057664supp001.pdf (171.1KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.