Abstract

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is a ubiquitous pathogen that establishes a lifelong infection affecting up to 80% of the US population. HCMV periodically reactivates leading to enhanced morbidity and mortality in immunosuppressed patients causing a range of complications including organ transplant failure and cognitive disorders in neonates. Therapeutic options for HCMV are limited to a handful of antivirals that target late stages of the virus life cycle and efficacy is often challenged by the emergence of mutation which confer resistance. In addition, these antiviral therapies have several adverse reactions including neutropenia in newborns and in increase in adverse cardiac events in HSCT patients. These findings highlight the need to develop novel therapeutics that target different steps of the viral life cycle. To this end, we screened a small molecule library against ion transporters to identify new antivirals against the early steps of virus infection. We identified valspodar, a 2nd-generation inhibitor characterized to target ABC transporters, to limit HCMV infection as demonstrated by the decrease in IE2 expression of virus infected cells. Cells treated with increasing concentrations of valspodar over a 9-day period have minimal cytotoxicity. Importantly, valspodar limits CMV plaque numbers in comparison to DMSO controls demonstrating its ability to inhibit viral dissemination. Collectively, valspodar represents a new anti-CMV therapeutic that limits CMV infection by likely targeting a host factor and suggests that specific ABC transporters may participate in the HCMV life-cycle.

Keywords: Human cytomegalovirus, valspodar, p-glycoprotein, novel drug, viral infection, dissemination

1. Introduction

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is a beta-herpesvirus with a global seroprevalence of 45–100%, exhibiting substantial geographic variation even within a country. HCMV infection of immune modulated patients including pregnant women can cause severe disease in newborns. In fact, HCMV is the leading cause of infectious congenital birth defects (Bale, J.F. et al., 2002). Also, HCMV accounts for more than 60% of complications in solid organ transplant patients (Lee, S. et al., 2020). The HCMV genome ~236 encodes for >170 ORF open reading frames with more than 20 viral envelope proteins. Following entry and viral capsid translocation to the nucleus, the viral life cycle occurs through highly-regulated temporal stages of IE gene expression, early gene expression, viral DNA replication, late gene expression and lastly, viral egress. The initial viral genes following infection are the essential IE1 and IE2 gene products ~6 hr post infection. IE1 stimulates viral and cellular promoters by interacting with diverse transcriptional regulators and synergistically with IE2 promoters (Meier, J.L. and M.F. Stinski, 1997) and IE2 is a transactivator for early viral proteins (Cherrington, J.M. and E.S. Mocarski, 1989, Meier, J.L. and M.F. Stinski, 1997). Thus, IE1/2 expression is an excellent proxy to evaluate therapeutics against a HCMV infection (Gardner, T.J. et al., 2013, Straschewski, S. et al., 2010) (Gardner, T.J. et al., 2016).

Our current study examined compounds characterized to target cell surface membrane transports and found that the valspodar limits a HCMV infection. Valspodar was characterized to target the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) family member multidrug resistance protein-1(MDR1, p-glycoprotein) (ABCB1). Some ABC transporters export a variety of substrates across the membrane bilayer functioning as drug efflux pumps (Ween, M.P. et al., 2015). Many tumors up-regulate MDR1 and multidrug resistance-associated protein 1 (MRP1) (ABCC1) expression or activity to enhance the expulsion of chemotherapy drugs (Gimenez-Bonafe, P. et al., 2004, Gradilone, A. et al., 2008, Ween, M.P. et al., 2015). In theory, ABC transporter inhibitors may be effective in combination with chemotherapy to enhance drug levels in tumor cells (Chen, Z. et al., 2016, Nanayakkara, A.K. et al., 2018). There are several inhibitors characterized to target MDR1, often with overlapping affinities, that fall into three classes: 1st-, 2nd-, and 3rdgeneration inhibitors (Thomas, H. and H.M. Coley, 2003). The 1st-generation represents naturally occurring compounds such as cyclosporine D, the 2nd-generation are synthetic derivatives of natural products such as valspodar, and the 3rd-generation represents synthetic compounds (Krishna, R. and L.D. Mayer, 2000). These inhibitors typically modulate ABC transporter function by competing for binding and transport of the substrate across the membrane or by binding to the protein and inducing allosteric changes, which hinder translocation.

Valspodar, also known as PSC-833, was developed by Sandoz/Novartis (Twentyman, P.R. and N.M. Bleehen, 1991) as a chemosensitizer and studied thoroughly on hematological and solid tumors refractory to the classical anticancer drugs. Valspodar dose-dependently inhibits both the substrate export and basal ATPase activity of p-glycoprotein (Loor, F., 1999). Valspodar showed higher selectivity than other 2nd generation modulators for inhibition of p-glycoprotein and other ABC transporters (Ween, M.P. et al., 2015), but shares a common side effect with cyclosporins hepatotoxicity (Loor, F., 1999). Valspodar can also impact the activity of cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A), an enzyme that metabolizes ~30% of all prescribed drugs (Zanger, U.M. and M. Schwab, 2013). While these inhibitors have been studied in oncology, less is known about their impact in viral infections (Chen, Z. et al., 2016), and especially in the context of HCMV infection. Interestingly, a member of the ABC family ABCC1, multidrug resistant-associated protein-1, has been targeted for degradation in latently-infected HCMV cells (Weekes, M.P. et al., 2013). Thus, we propose that ABC transporters may play a greater role during a HCMV life cycle and they may represent new targets to limit HCMV infection and dissemination.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell lines, viruses and chemicals.

MRC5 and NHDF (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were cultured in DMEM (Corning #10–013-CV) with 10% FBS, 1mM HEPES (Corning, #25–060-CI), 100U/mL penicillin and 100g/mL streptomycin (Corning, #30–002-CI). The ARPE-19 human retinal epithelial cells (ATCC #CRL-2302) were cultured in DMEM/F-12 medium (Gibco, # 11765–054) at 1:1 ratio with FBS, HEPES and Pen/Strep. The HCMV strain AD169IE2-YFP and a repaired AD169 (denoted BADrUL131-C4) containing the UL131-UL128 open reading frame of the HCMV strain TR and expresses the reporter EGFP (AD169BADrUL131) (Wang, D. and T. Shenk, 2005) were propagated as described (Gardner, T.J. et al., 2013). Infectious virus yield was assayed on MRC5 by median tissue culture infective dose (TCID50). The Membrane Transporter/Ion Channel Compound Library (#HY-L011, 123 compounds (10mM DMSO) was from MedChem Express (Manmouth Junction, NJ). P-glycoprotein inhibitors elacridar (HY-50879), tariquidar (HY-10550), valspodar (#HY-17384), and zosuquidar (HY-15255) and ganciclovir (HY-13637) from MedChem Express were resuspended in DMSO (10mM).

2.2. MedChemExpress Screen.

MRC5 cells (1×104) in 96-well plates (Greiner, Monroe, NC) were pre-treated for 1 hour with 5μM in duplicate prior to infection with AD169IE2-YFP (MOI:3). At 18hpi, cells were analyzed with an Acumen eX3 cytometer for the number of IE2-YFP positive cells/well based on IE2-YFP fluorescent intensity/well (Gardner, T.J. et al., 2013). Any fluorescent signal larger than 5μm, smaller than 300μm, and separated from any other emission by at least 0.5μm in both x and y axes was classified as an “event.” Fluorescent emission above 2 standard deviations of background was registered as positive signal. Using DMSO treated cells infected with AD169IE2-YFP as 100% infection, the percent infection of cells pre-treated with each compound was determined. These values were used to calculate the Robust Z-scores for each compound to determine the Median Absolute Deviation (MAD) value, a statistical strategy to minimize the impact of outlining values over a data set (Zhang, J.H. et al., 1999).

2.3. Determining the half-maximal effective concentration (EC50) of p-glycoprotein inhibitors.

MRC5 cells (1×104) in a 96-well plate were treated with varying concentrations (0–5μM) of compound in sextuplicate (1h@ 37°C) and infected with AD169IE2-YFP (MOI:3). At 18hpi, the plates were analyzed for the number of IE2-YFP positive cells/well based on IE2-YFP fluorescent intensity/well (Gardner, T.J. et al., 2013) as above. Using DMSO treated cells (0.1%) infected with AD169IE2-YFP as 100% infection, the percent infection of treated cells was determined (Gardner, T.J. et al., 2015).

2.4. Determine the cytotoxicity of P-glycoprotein inhibitors.

MRC5 cells (1×104) in a 96-well plate were treated with varying concentrations (0–5μM) of compound in sextuplicate (Cohen, T. et al., 2016). After 19 hours, NucGreen Dead 488 (NucGreen) (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) was directly added to five of six wells/condition (10min at RT). The number of dead cells (NucGreen+) cells was determined by measuring the fluorescent intensity/well using a fluorescent plate reader. Cellular toxicity of the compound-treated cells was calculated into percent cell viability using total number of cells as 100% compared to the number of NucGreen-positive cells from treated cells. The MTT assay (Biotium Inc, Fremont, CA) was performed based on the manufacture’s instruction. MRC5 cells (1×104) in a 96-well were treated with the respective compound (0–33.3 μM) for the indicated times and analyzed using a spectrophotometer after 16hrs. The CellTiter Glo Luminescent Assay (Promega Inc, Madison, WI) was performed based on the manufacture’s instruction. MRC5 cells (1×104) plated in a 96-well plate overnight were treated with valspodar (2.5–40μM) in triplicate for up to 6 days. Cyclohexamide (50μg/mL) was used as a control. CellTiter Glo substrate was added in a 1:1 ratio with media in cells treated for 1, 3, 6, and 9days and the luciferase activity (relative light units, RLU) was measured using a BioTek Synergy H1 microplate reader. In a parallel, an identical plate was labelled with Hoechst reagent (25μg/ml) to quantify the cell number using a Celigo cytometer.

2.5. Time-of-addition assay.

NDHF cells (1×104) were plated in a 96-well plate overnight were untreated or treated with valspodar (10μM) at −60 to 180 minutes post infection (mpi) or heparin (50μg/ml) at −60mpi with AD169 (MOI:1). At 24hpi, the cells lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis using anti-IE1 and anti-GAPDH antibodies (Stein, K.R. et al., 2019).

2.6. Evaluating virus dissemination upon treatment with valspodar.

The virus focus forming units (FFU) assay was performed on NHDF and ARPE-19 cells (50,000 cells/well) in a 24-well plate followed by virus infection with AD169BADrUL131 or TB40/E (MOI:0.001) with valspodar (1–20uM), DMSO or ganciclovir (5uM) at 7 and 10–12dpi. Following a 2 hr incubation at 37oC, the inoculum was removed and cells were overlaid with 1% low melt sea agarose. Upon solidification of the agarose, valspodar, DMSO or ganciclovir in media was added at the indicated concentrations. For AD169BADrUL131-infected cells, the cells were examined using brightfield and YFP fluorescence to quantify the number and size of virus clusters using a Celigo Cytometer. For TB40/E-infected cells, the cells were stained using an anti-IE1 rabbit antibody followed by an anti-rabbit IgG-conjugated to Alexa647 and measured using a Celigo cytometer (Stein, K.R. et al., 2019). The FFU were referred to as plaques based on average cluster area of 10,000μm2 or 30,000μm2 and the average colony area (μm2).

3. Results

3.1. High-content screening of HCMV infection identifies valspodar as a novel inhibitor.

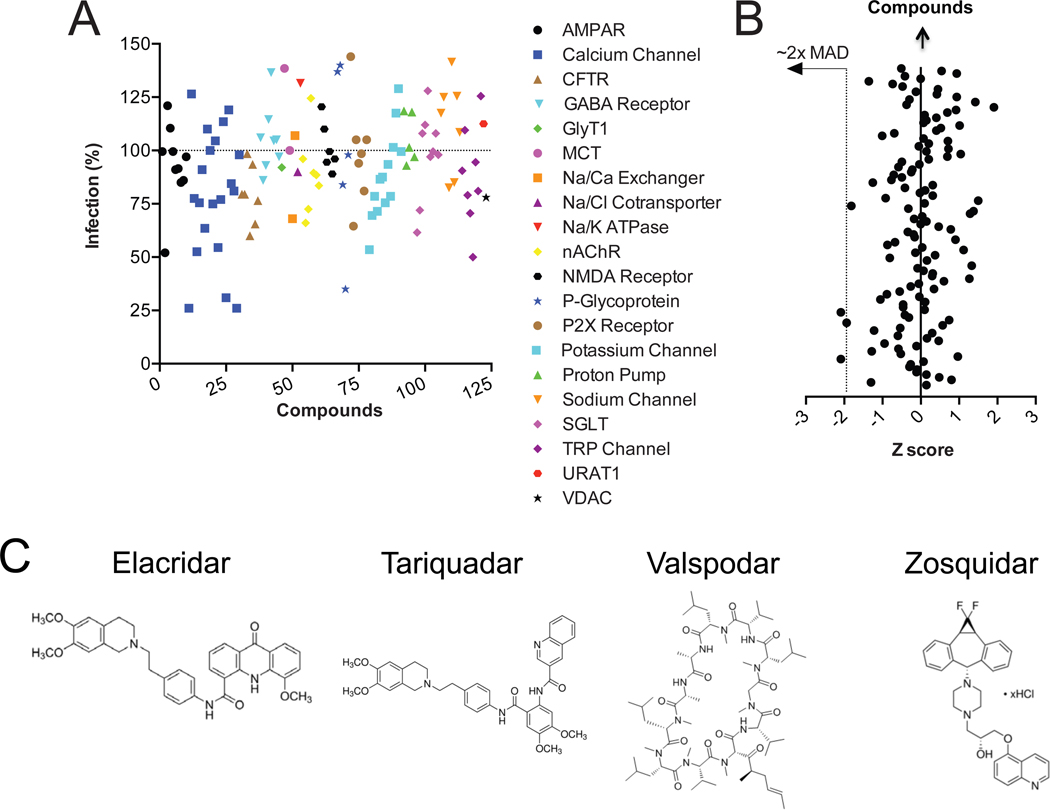

A previous high-content screen identified the cardioglycoside convallatoxin, an Na/K-ATPase transporter inhibitor, as a HCMV entry inhibitor (Gardner, T.J. et al., 2015, Babula, P. et al., 2013). To further evaluate whether cellular transporters play role in virus infection, we performed a high-content screen using the AD169IE2-YFP-fibroblast infection model with the MedChem Express membrane transporters and ion channels library (123 compounds) (Figure 1A). MRC5 cells pre-treated with the chemical library were infected with AD169IE2-YFP and analyzed for virus-infected cells by measuring YFP fluorescent intensity (Gardner, T.J. et al., 2016) at 18hpi. Using DMSO-treated cells infected with virus as 100% infection, the most effective compounds that inhibited infection were Ca+2 channel inhibitors and valspodar, an inhibitor initially characterized against p-glycoprotein (Figure 1A). In order to identify compounds that statistically decrease an HCMV, a robust Z score value was calculated for each compound (Chung, N. et al., 2008) and applying the 2-sigma rule for the median absolute deviation (MAD), four compounds decreased infection and reduced YFP fluorescent intensity beyond the normal distribution (Figure 1B). Given the novelty of valspodar in a HCMV infection and previous findings that Ca+2 channel inhibitors inhibit HCMV infection (Dunn, D.M. and J. Munger, 2020, Mercorelli, B. et al., 2018, Allal, C. et al., 2004), we focused on characterizing valspodar as a HCMV inhibitor.

Figure 1. High content screen to identify CMV inhibitors.

(A) MRC5 cells were pretreated with compounds of the MedChem Express library of membrane transport/ion channel inhibitors and infected with AD169IE2-YFP (MOI:3). The number of infected cells was quantified based on YFP fluorescence with the Acumen eX3 cytometer. Average YFP mean fluorescent intensity from MRC5 cells infected with AD169IE2-YFP-infected fibroblasts was calculated into % infection (duplicates) based on YFP (+) cells using DMSO treated cells as 100% infection. The % infection was plotted based on chemical ID number (X axis). Symbols represent the protein family target of the different compounds. (B) The robust Z-score (X axis) was calculated from the fluorescence intensity of AD169IE2-YFP-infected fibroblasts for each compound and plotted against each compound (Y axis). Four compounds reduced YFP expression >2 median absolute deviations (MAD) (dotted line) beyond the mean score (Y axis). (C) The structures of elacridar, tariquidar, valspodar, and zosuquidar are indicated.

3.2. Valspodar limits CMV infection with minimal toxicity.

Valspodar limited a HCMV infection by ~65% compared to the 3rd-generation ABC transporter inhibitors elacridar, tariquidar, and zosuquidar in the library (Figure 1A). Valspodar is a 2nd-generation inhibitor that is structurally diverse than elacridar, tariquidar, and zosuquidar (Figure 1C). The 3rd-generation inhibitors were designed to inhibit noncompetitively and preferentially target brain capillaries (Hubensack, M. et al., 2008). These differences may contribute to the effectiveness of valspodar over the other inhibitors. In order to validate the specificity of valspodar, MRC5 cells pre-treated with increasing doses of elacridar, tariquidar, valspodar, and zosuquidar were infected with AD169IE2-YFP (MOI:3) and analyzed for virus infected cells (Figure 2A, black lines). The calculated effective concentration to reduce virus infection (EC50) of valspodar was ~4μM (Figure 2A). EC50 values could not be calculated for elacridar or zosuquidar (Figure 2A) and the EC50 value for tariquidar was >15μM (Figure 2A), nearly 5x greater than valspodar. These findings further support valspodar as a HCMV inhibitor.

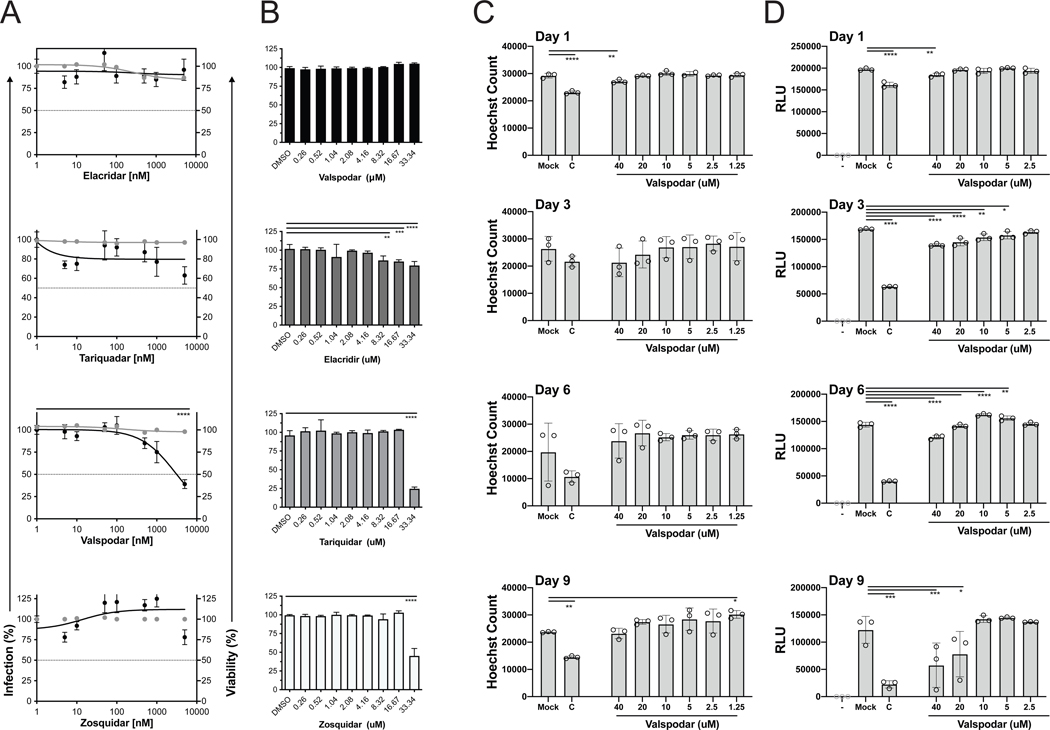

Figure 2. Determine efficacy of p-glycoprotein inhibitors.

(A) MRC5 cells treated with DMSO and increasing amounts of elacridar, tariquidar, valspodar, and zosuquidar (0–5000nM) were infected with AD169IE2-YFP (MOI:3) and subjected to analysis using an Acumen eX3 cytometer for YFP(+) cells. The % infection (black lines and circles) was determined based on the number of YFP(+) cells from compound-treated cells using DMSO-treated cells as 100% infection. The intranuclear cell staining using NucGreen fluorescent cell dye was utilized to determine cell viability (gray lines and circles) with DMSO treated cells as 100% cell viability. Error bars represent standard error of the mean. (B) MRC5 cells treated with DMSO and increasing amounts of elacridar, tariquidar, valspodar, and zosuquidar (0–33.34μM) for two days was subjected to a MTT assay. DMSO treated cells was designated at 100% cell viability and error bars represent standard error of the mean. MRC5 cells treated with DMEM, cyclohexamide or increasing concentrations of valspodar for 1, 3, 6, or 9 days were stained with Hoechst reagent (C) to quantify cells/well (in triplicate) or measured for ATP levels using Ultra-Glo™ rLuciferase activity (D) (relative light units (RLU) (in triplicate)). Statistical significance was determined by a one-way ANOVA (p value, * <0.05, ** <0.01, *** < 0.001, **** <0.0001).

In parallel, the cell impermeant dye NucGreen was used to evaluate cell toxicity (Figure 2A, gray lines). The concentration of the compounds needed to kill 50% of the cells (CC50) could not be determined after 24 hours of treatment. To further evaluate valspodar induced cytotoxicity, MRC5 cells treated with elacridar, tariquidar, valspodar, and zosuquidar (0–33μM) were evaluated using an MTT assay (Figure 2B). The MTT assay measures cell viability based on the cell metabolic activity of NADH-dependent cellular oxidoreductase (Riss, T.L. et al., 2004). The results demonstrate that elacridar and valspodar do not induce cell toxicity for up to 33μM. However, after only two days, tariquidar and zosuquidar significantly decreased cell viability at 33μM. These findings demonstrate that elacridar, tariquidar, valspodar, and zosuquidar have minimal toxicity upon short-term treatments.

We next evaluated the cytostaticity and cytotoxicity of long-term treatment with valspodar (Figure 2C–D). Confluent MRC5 cells treated with valspodar (0–40μM) and cycloheximide (50μg/mL) for up to 9 days was analyzed for cell number by staining with Hoechst reagent (Figure 2C) or ATP levels using CellTiter Glo luciferase activity (Figure 2D). Valspodar treatment did not significantly reduce the cell number over 9 days at even the highest concentration of 40μM. Upon examination of ATP levels in valspodar-treated cells, a small decrease (10–15%) in luciferase activity (relative light units, RLU) was observed at Day 3 and 6 >5μM and ~50% decrease at 20 and 40μM treated cells at Day 9 (Figure 2D). Cycloheximide treated cells demonstrated a significant decrease in cell number and luciferase activity (Figure 2C–D). These results imply that valspodar does not does not cause major cell toxicity at concentrations that limit virus infection and impacts ATP levels at >20μM during long term treatment. Thus, valspodar is not toxic at low concentrations upon prolonged treatment.

3.3. Valspodar limits virus infection.

Human fibroblasts pretreated with increasing concentrations of valspodar (0–16μM) were infected with AD169IE2-YFP and virus infection was evaluated at 24hpi (Figure 3A). As a control, cells were treated with the previously characterized inhibitor convallatoxin (10nM). The % infection was determined using DMSO treated cells as 100% infection. Interestingly, valspodar was unable to completely inhibit infection and reaches a maximum inhibition plateau of ~40% infection at >10μM. The data suggest that valspodar inhibition may be due to a low affinity interaction with its target and not completely block infection. Also, the redundant entry pathways of HCMV may allow to escape valspodar-dependent inhibition.

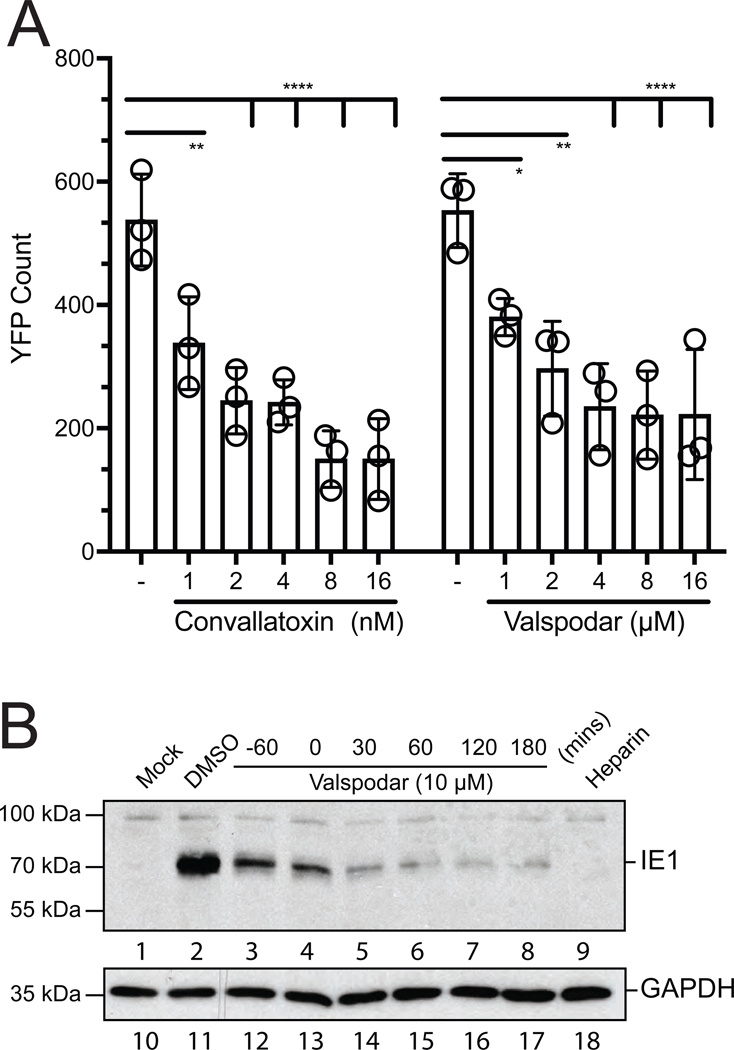

Figure 3. Valspodar limits a HCMV infection.

(A) Fibroblasts treated with valspodar (0–16μM) and convallatoxin (0–16nM) were infected with AD169IE2-YFP (MOI:1) and subjected to analysis using an Celigo cytometer for YFP(+) cells. The % infection was determined based on DMSO-treated cells as 100% infection. The error bars represent standard error of the mean from 4 samples. (B) NHDF cells mock-infected or infected with AD169 (MOI:1) untreated (DMSO) and treated at −60, 0, 30, 60, 120, and 180 minutes (mins) post-infected with valspodar or −60 mins post with heparin (50μg/ml) were harvested at 24hpi. The total cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis using an anti-IE1 (lanes 1–9) or anti-GAPDH (lanes 9–16) antibodies. The molecular weight markers and targeted polypeptides are indicated. Statistical significance was determined by a two-way ANOVA (p value, * <0.05, ** <0.01, **** <0.0001).

We next evaluated the ability of valspodar to block infection during the initial stage of entry (Figure 3B). MRC5 were treated at −60, 0, 30, 60, 120, and 180 minutes post-infection (mpi) with AD169 (MOI:1). At 24hpi, infected cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis for IE1 protein (Figure 3B, lanes 1–9). Mock (M), DMSO (−), and heparin (50μg/ml) treated cells were used as controls. A GAPDH immunoblot was used as a loading control (Figure 3B, lanes 10–18). Valspodar treatment inhibited IE1 expression at all times post-infection with the most effective after 30 mpi (Figure 3B, lanes 5–8). As expected, heparin treatment inhibited virus infection (Figure 3B, lane 9). The results demonstrate that valspodar functions prior to and up to 2 hpi at preventing IE1 expression by targeting a step during from virus entry to IE1 gene expression. In addition, an immunoblot of in virus-infected cells treated with valspodar at 3 dpi revealed a significant decrease in IE1 expression (Supplemental Figure 1A). Collectively, these findings support the model that valspodar limits a HCMV infection.

3.4. Valspodar limits CMV proliferation.

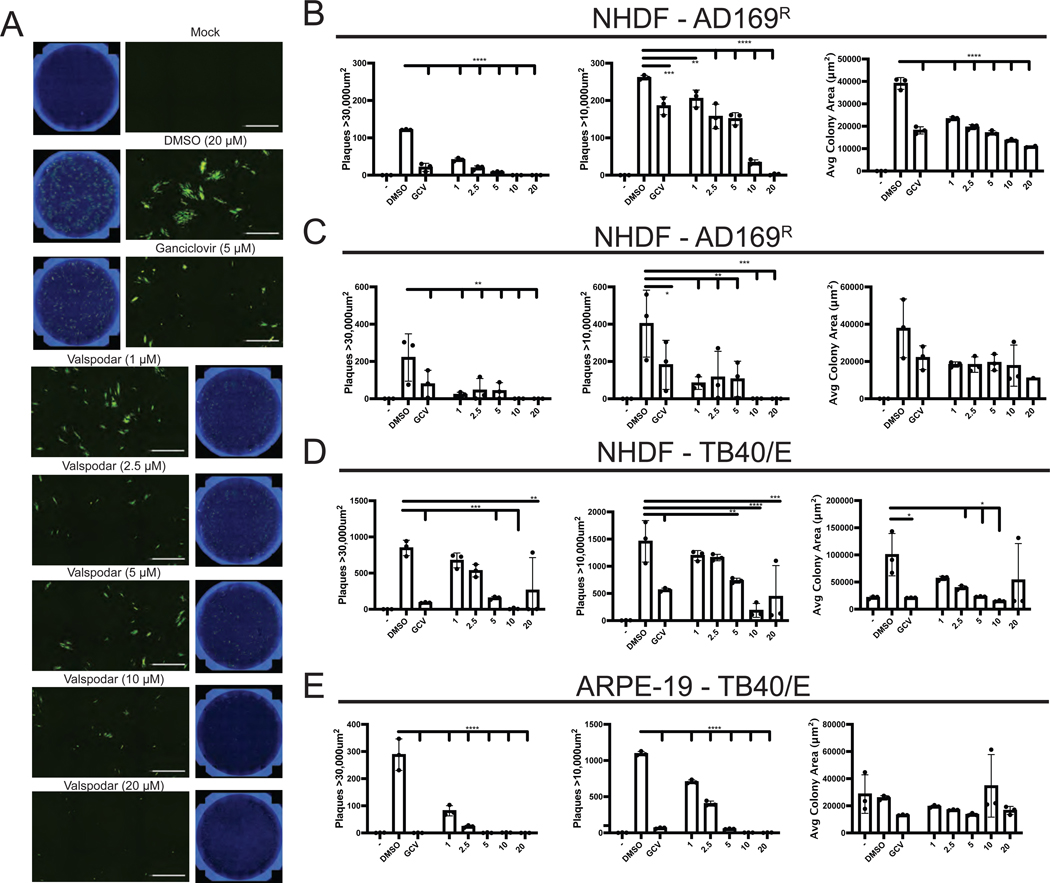

To address whether valspodar is capable of inhibiting multi-cycle virus proliferation, we performed a virus focus forming unit (FFU) assay (Figure 4). NHDF pretreated with DMSO, valspodar (0–20μM) or ganciclovir (5μM) were infected with AD169BADrUL131a (AD169R) and analyzed for clusters of virus infected cells at 7 and 12dpi based on YFP fluorescence. Ganciclovir is a FDA approved anti-CMV drug that limits HCMV DNA replication by targeting the viral polymerase UL97 (Biron, K.K., 2006). A cluster of virus infected cells will be designated a viral plaque based on an average cluster area of 10,000μm2 or 30,000μm2 for small and large viral clusters. Whole well images and zoomed images after 12dpi using Hoechst (blue) and YFP (green) demonstrate the size and fluorescence signal of the viral clusters (Figure 4A). Valspodar treatment significantly reduced virus plaques at 7 and 12dpi compared to plaques of untreated cells (Figure 4B and C). The variability in plaques at day 12dpi was due to the merging of nearby plaques making distinction of plaque borders more difficult. Treatment with 1μM valspodar decreased plaque number by ~40% at 7dpi and ~75% at 12dpi, while 10μM and 20μM valspodar treatment almost completely inhibited plaque formation. Also, valspodar was as effective at inhibiting virus dissemination as ganciclovir demonstrating valspodar as an effective inhibitor of CMV proliferation.

Figure 4. Valspodar inhibits HCMV dissemination in fibroblast and epithelial cells.

(A) AD169BADrUL131 (AD169R) (MOI:0.001) infected NHDF cells treated valspodar (0–20μM), DMSO, or ganciclovir (5μM) were fixed on 7 and 12dpi and stained with Hoechst reagent to quantify cell number and imaged using a Celigo cytometer to determine plaque size and number based on YFP fluorescent signal. Representative images from each condition are shown as a well and increased magnification (20X). Plaque numbers from 7dpi (B) and 12dpi (C) were determined based on the size of a virus cluster of at least > 30,000 μm2 and >10,000 μm2 and the average colony area for plaques (μm2) with a 10,000 μm2 cutoff. Plaque numbers and colony area were determined from TB40/E infected NHDF (D) or ARPE-19 epithelial cells (E). Statistical significance was determined by a two-way ANOVA (p value, * <0.05, ** <0.01, **** <0.0001).

We next examined the effectiveness of valspodar to limit dissemination of TB40/E diverse cell types (Figure 4D–E). NHDF or ARPE-19 cells pretreated with increasing concentrations of valspodar (0–20μM) or ganciclovir (5μM) with infected with TB40/E and analyzed for plaques at 10 dpi (Figure 4D–E). Virus-infected cells were determined by staining cells with an anti-IE1 antibody (Stein, K.R. et al., 2019) and the viral plaques were determined based on the average cluster area of 10,000μm2 or 30,000μm2 and average colony area (μm2). In all case, there was a valspodar concentration dependent decrease of viral plaques (Figure 4D–E). For virus infected NHDF cells, the valspodar EC50 values ranged from ~3–5μM (Figure 4D) and ~1–3μM for TB40/E-infected ARPE-19 cells (Figure 4E). Ganciclovir-treated cells were used as a control for inhibition of CMV proliferation (Figure 4D–E). Collectively, valspodar represents a new HCMV inhibitor that limit virus dissemination in diverse cell types.

4. Discussion

ABC transporters represent a group of membrane transporters that export a wide array of xenobiotics from cells and are proposed to impart drug resistance to cancer cells (Lu, J.F. et al., 2015, Chen, Z. et al., 2016, Fletcher, J.I. et al., 2010, Ween, M.P. et al., 2015). The ABC transporter p-glycoprotein has been implicated in the inflammatory response, apoptosis, and pathogen resistance to drugs by mediating the transport of glucocorticoids, HIV protease inhibitors and antibiotics, respectively (Garcia-Carrasco, M. et al., 2015). The identification of valspodar, initially characterized as a p-glycoprotein inhibitor, as a HCMV inhibitor suggests that p-glycoprotein or other possible ABC transporters targeted by valspodar (e.g. ABCB2, ABCB11, ABCC2, ABCC4) (Ween, M.P. et al., 2015) may be involved in virus infection and dissemination. Our data indicates that valspodar functions upon pre-treatment and up to 2hpi suggesting it targets a during the early stage of infection including viral gene expression (Figures 1–3), but a mechanism of action needs to delineated. Interestingly, targeting p-glycoprotein with an antibody characterized to limit protein activity (Mechetner, E.B. and I.B. Roninson, 1992, Goda, K. et al., 2007) did not limit HCMV infection (Supplemental 1B). These results imply that valspodar-induced HCMV inhibition may be independent of p-glycoprotein activity or again may be dependent on a different ABC transporter. Thus, it would be interesting to discover if a different ABC transporter participates in an HCMV infection, perhaps through siRNA knockdown or CRISPR knockout screens. Mdr1a−/− (p-glycoprotein) knockout mice infected with ectromelia virus had reduced virus titers supporting the role of p-glycoprotein in virus proliferation (Xu, D. et al., 2004). Also, overexpression of p-glycoprotein limited infection of HIV, influenza and Sendai virus (Blumenthal, R.D. et al., 2000, Lee, C.G. et al., 2000) suggesting that p-glycoprotien may have a more global impact on virus infection and dissemination. Given that ABC transporters play numerous roles in membrane integrity, intracellular signaling, and lipid metabolism (Johnstone, R.W. et al., 2000), inhibition of this family of compounds by valspodar may directly or indirectly impact virus infection and spread.

Anti-HCMV drugs approved for solid organ transplant and HSCT recipients (>50,000 in US (Bently, T.S. and S.G. Hanson, 2014)) include ganciclovir, foscarnet, fomivirsen (Biron, K.K., 2006), and recently letermovir (Kim, E.S., 2018). These drugs, except for fomivirsen, target viral replication and packaging, respectively (Lurain, N.S. and S. Chou, 2010). Limitations to these drugs include the incomplete prevention of virus-associated diseases, cytotoxicity, and the rise of resistant strains. There are also several preclinical studies that have identified compounds that limit CMV replication: 1) artemisinins (Arav-Boger, R. et al., 2010), 2) an anthraquinone derivative, atanyl blue PRL, also inhibits herpes simplex virus (Alam, Z. et al., 2015), 3) the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) inhibitor SP600125 (Zhang, H. et al., 2015) and 4) compounds that inhibit IE2’s activation of early gene transcription (Mercorelli, B. et al., 2016). These studies exemplify that targeting different steps of the CMV life cycle can impact viral replication. The multi-drug approach has been quite effective in treating HIV and HCV infected individuals (Shafer, R.W. and D.A. Vuitton, 1999, De Clercq, E., 2013) and may be effective approach to prevent CMV-associated diseases

Valspodar limited infection in fibroblasts when pre-treated or present during infection as indicated by a reduction in IE1 protein expression (Figure 3). Additionally, valspodar was quite effective at limiting HCMV dissemination in both epithelial and fibroblast (Figure 4). The cytotoxicity data demonstrated that valsopdar has limited toxicity at concentrations that limit virus dissemination as observed by cell permeability assays and analysis of metabolically activity (Figures 2). Even though valspodar can cause hepatotoxicity, this is dependent on cell type and dosage. Thus, valspodar may be useful in a combination with other HCMV drugs. Collectively, valspodar represents a new class of HCMV inhibitors that impact virus infection and dissemination.

5. Conclusions

Human cytomegalovirus proliferation increases the morbidity and/or mortality of immunocompromised individuals such as newborns, organ transplant recipients, and AIDS patients. Safe and effective drugs are required to limited cytomegalovirus infection and proliferation. We have identified valspodar as a new class of human cytomegalovirus inhibitors that block infection and virus dissemination.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1. (A) Valspodar blocks IE1 expression of HCMV infection. NHDF cells mock-infected or infected with AD169 (MOI:1) untreated (DMSO) and treated at -60, 0, and 30 minutes (mins) post-infected with valspodar or −60 minutes post with heparin (50μg/ml) were harvested at 24hpi. The total cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis using an anti-IE1 (lanes 1–9) or anti-GAPDH (lanes 9–16) antibodies. The molecular weight markers and targeted polypeptides are indicated. (B) Anti-p-glycoprotein antibody does not block a HCMV infection. NHDF cells preincubated with anti-p-glycoprotein antibody (UIC-2), anti-MRP1, and isotype control (0–40ug/ml) for 1hour at 37oC were infected with AD169R (moi: 0.5) and analyzed for GFP positive cells at 24hpi using a Celigo Cytometer. The data points represent triplicate of each time point and the error bars are the standard error.

Highlights.

Valspodar limits human cytomegalovirus infection.

Valspodar inhibits human cytomegalovirus proliferation and dissemination.

Valspodar represents a new class of human cytomegalovirus inhibitors.

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported in part by NIH grants R01AI139258, R21AI147632, RF1AG059319, and T32AI007647. A.P. is sponsored in part by a USPHS institutional research training award T32-AI007647. We would like to thank Rosmel Hernandez for discussion regarding valspodar function.

Abbreviations

- dpi

days post-infection

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

- hpi

hours post-infection

- HSCT

hematopoietic stem cell transplant

- MRC5

human lung fibroblasts

- IE

immediate-early

- MOI

multiplicity of infection

- NHDF

newborn human dermal fibroblasts

- ORF

open reading frame

- Pgp

P-glycoprotein

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References :

- Alam Z, Al-Mahdi Z, Zhu Y, Mckee Z, Parris DS, Parikh HI, Kellogg GE, Kuchta A. & Mcvoy MA 2015. Anti-cytomegalovirus activity of the anthraquinone atanyl blue PRL. Antiviral Res, 114, 86–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allal C, Buisson-Brenac C, Marion V, Claudel-Renard C, Faraut T, Dal Monte P, Streblow D, Record M. & Davignon JL 2004. Human cytomegalovirus carries a cell-derived phospholipase A2 required for infectivity. J Virol, 78, 7717–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arav-Boger R., He R, Chiou CJ, Liu J, Woodard L, Rosenthal A, Jones-Brando L, Forman M. & Posner G. 2010. Artemisinin-derived dimers have greatly improved anti-cytomegalovirus activity compared to artemisinin monomers. PLoS One, 5, e10370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babula P, Masarik M, Adam V, Provaznik I. & Kizek R. 2013. From Na+/K+-ATPase and cardiac glycosides to cytotoxicity and cancer treatment. Anticancer Agents Med Chem, 13, 1069–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bale JF, Miner L. & Petheram SJ 2002. Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection. Curr Treat Options Neurol, 4, 225–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bently TS & Hanson SG 2014. Milliman Research Report: 2014 U.S. organ and tissue transplant cost estimates and discussion. [Google Scholar]

- Biron KK 2006. Antiviral drugs for cytomegalovirus diseases. Antiviral Res, 71, 154–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal RD, Lew W, Juweid M, Alisauskas R, Ying Z. & Goldenberg DM 2000. Plasma FLT3-L levels predict bone marrow recovery from myelosuppressive therapy. Cancer, 88, 333–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Shi T, Zhang L, Zhu P, Deng M, Huang C, Hu T, Jiang L. & Li J. 2016. Mammalian drug efflux transporters of the ATP binding cassette (ABC) family in multidrug resistance: A review of the past decade. Cancer Lett, 370, 153–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherrington JM & Mocarski ES 1989. Human cytomegalovirus ie1 transactivates the alpha promoter-enhancer via an 18-base-pair repeat element. Journal of virology, 63, 1435–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung N, Locco L, Huff KW, Bartz S, Linsley PS, Ferrer M. & Strulovici B. 2008. An efficient and fully automated high-throughput transfection method for genome-scale siRNA screens. J Biomol Screen, 13, 142–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen T, Williams JD, Opperman TJ, Sanchez R, Lurain NS & Tortorella D. 2016. Convallatoxin-Induced Reduction of Methionine Import Effectively Inhibits Human Cytomegalovirus Infection and Replication. J Virol, 90, 10715–10727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Clercq E. 2013. A cutting-edge view on the current state of antiviral drug development. Med Res Rev, 33, 1249–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn DM & Munger J. 2020. Interplay Between Calcium and AMPK Signaling in Human Cytomegalovirus Infection. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 10, 384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher JI, Haber M, Henderson MJ & Norris MD 2010. ABC transporters in cancer: more than just drug efflux pumps. Nat Rev Cancer, 10, 147–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Carrasco M, Mendoza-Pinto C, Macias Diaz S, Vera-Recabarren M, Vazquez De Lara L, Mendez Martinez S, Soto-Santillan P, Gonzalez-Ramirez R. & Ruiz-Arguelles A. 2015. P-glycoprotein in autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Autoimmun Rev, 14, 594–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner TJ., Bolovan-Fritts C, Teng MW, Redmann V, Kraus TA, Sperling R, Moran T, Britt W, Weinberger LS & Tortorella D. 2013. Development of a high-throughput assay to measure the neutralization capability of anticytomegalovirus antibodies. Clinical and vaccine immunology : CVI, 20, 540–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner TJ, Cohen T, Redmann V, Lau Z, Felsenfeld D. & Tortorella D. 2015. Development of a high-content screen for the identification of inhibitors directed against the early steps of the cytomegalovirus infectious cycle. Antiviral Res, 113, 49–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner TJ, Stein KR, Duty JA, Schwarz TM, Noriega VM, Kraus T, Moran TM & Tortorella D. 2016. Functional screening for anti-CMV biologics identifies a broadly neutralizing epitope of an essential envelope protein. Nat Commun, 7, 13627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimenez-Bonafe P, Fedoruk MN, Whitmore TG, Akbari M, Ralph JL, Ettinger S, Gleave ME & Nelson CC 2004. YB-1 is upregulated during prostate cancer tumor progression and increases P-glycoprotein activity. Prostate, 59, 337–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goda K, Fenyvesi F, Bacso Z, Nagy H, Marian T, Megyeri A, Krasznai Z, Juhasz I, Vecsernyes M. & Szabo G Jr. 2007. Complete inhibition of Pglycoprotein by simultaneous treatment with a distinct class of modulators and the UIC2 monoclonal antibody. J Pharmacol Exp Ther, 320, 81–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gradilone A, Spadaro A, Gianni W, Agliano AM & Gazzaniga P. 2008. Induction of multidrug resistance proteins in lymphocytes from patients with arthritic disorders. Clin Exp Med, 8, 229–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubensack M, Muller C, Hocherl P, Fellner S, Spruss T, Bernhardt G. & Buschauer A. 2008. Effect of the ABCB1 modulators elacridar and tariquidar on the distribution of paclitaxel in nude mice. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol, 134, 597607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone RW, Ruefli AA & Smyth MJ 2000. Multiple physiological functions for multidrug transporter P-glycoprotein? Trends Biochem Sci, 25, 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim ES 2018. Letermovir: First Global Approval. Drugs, 78, 147–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna R. & Mayer LD 2000. Multidrug resistance (MDR) in cancer. Mechanisms, reversal using modulators of MDR and the role of MDR modulators in influencing the pharmacokinetics of anticancer drugs. Eur J Pharm Sci, 11, 265–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CG, Ramachandra M, Jeang KT, Martin MA, Pastan I. & Gottesman MM 2000. Effect of ABC transporters on HIV-1 infection: inhibition of virus production by the MDR1 transporter. FASEB J, 14, 516–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Park Y, Kim SG, Ko EJ, Chung BH & Yang CW 2020. The impact of cytomegalovirus infection on clinical severity and outcomes in kidney transplant recipients with Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia. Microbiol Immunol, 64, 356–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loor F. 1999. Valspodar: current status and perspectives. Expert Opin Investig Drugs, 8, 807–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu JF, Pokharel D. & Bebawy M. 2015. MRP1 and its role in anticancer drug resistance. Drug Metab Rev, 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lurain NS & Chou S. 2010. Antiviral drug resistance of human cytomegalovirus. Clinical microbiology reviews, 23, 689–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechetner EB & Roninson IB 1992. Efficient inhibition of P-glycoprotein-mediated multidrug resistance with a monoclonal antibody. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 89, 5824–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier JL & Stinski MF 1997. Effect of a modulator deletion on transcription of the human cytomegalovirus major immediate-early genes in infected undifferentiated and differentiated cells. Journal of virology, 71, 1246–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercorelli B, Luganini A, Celegato M, Palu G, Gribaudo G. & Loregian A. 2018. Repurposing the clinically approved calcium antagonist manidipine dihydrochloride as a new early inhibitor of human cytomegalovirus targeting the Immediate-Early 2 (IE2) protein. Antiviral Res, 150, 130–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercorelli B., Luganini A, Nannetti G, Tabarrini O, Palu G, Gribaudo G. & Loregian A. 2016. Drug Repurposing Approach Identifies Inhibitors of the Prototypic Viral Transcription Factor IE2 that Block Human Cytomegalovirus Replication. Cell Chem Biol, 23, 340–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanayakkara AK, Follit CA, Chen G, Williams NS, Vogel PD & Wise JG 2018. Targeted inhibitors of P-glycoprotein increase chemotherapeutic-induced mortality of multidrug resistant tumor cells. Sci Rep, 8, 967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riss TL, Moravec RA, Niles AL, Duellman S, Benink HA, Worzella TJ & Minor L. 2004. Cell Viability Assays. In: Markossian S, Sittampalam GS, Grossman A, Brimacombe K, Arkin M, Auld D, Austin CP, Baell J, Caaveiro JMM, Chung TDY, Coussens NP, Dahlin JL, Devanaryan V, Foley TL, Glicksman M, Hall MD, Haas JV, Hoare SRJ, Inglese J, Iversen PW, Kahl SD, Kales SC, Kirshner S, Lal-Nag M, Li Z, Mcgee J, Mcmanus O, Riss T, Saradjian P, Trask OJ Jr., Weidner JR, Wildey MJ, Xia M. & Xu X. (eds.) Assay Guidance Manual. Bethesda (MD). [Google Scholar]

- Shafer RW & Vuitton DA 1999. Highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) for the treatment of infection with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie, 53, 73–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein KR, Gardner TJ, Hernandez RE, Kraus TA, Duty JA, Ubarretxena-Belandia I, Moran TM & Tortorella D. 2019. CD46 facilitates entry and dissemination of human cytomegalovirus. Nat Commun, 10, 2699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straschewski S, Warmer M, Frascaroli G, Hohenberg H, Mertens T. & Winkler M. 2010. Human cytomegaloviruses expressing yellow fluorescent fusion proteins--characterization and use in antiviral screening. PLoS ONE, 5, e9174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas H. & Coley HM 2003. Overcoming multidrug resistance in cancer: an update on the clinical strategy of inhibiting p-glycoprotein. Cancer Control, 10, 159–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twentyman PR & Bleehen NM 1991. Resistance modification by PSC-833, a novel non-immunosuppressive cyclosporin [corrected]. Eur J Cancer, 27, 1639–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D. & Shenk T. 2005. Human cytomegalovirus virion protein complex required for epithelial and endothelial cell tropism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 102, 18153–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weekes MP, Tan SY, Poole E, Talbot S, Antrobus R, Smith DL, Montag C, Gygi SP, Sinclair JH & Lehner PJ 2013. Latency-associated degradation of the MRP1 drug transporter during latent human cytomegalovirus infection. Science, 340, 199–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ween MP, Armstrong MA, Oehler MK & Ricciardelli C. 2015. The role of ABC transporters in ovarian cancer progression and chemoresistance. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol, 96, 220–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu D, Regner M, Smith D, Ruby J, Johnstone R. & Mullbacher A. 2004. The multidrug resistance gene mdr1a influences resistance to ectromelia virus infection by mechanisms other than conventional immunity. Immunol Cell Biol, 82, 462–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanger UM & Schwab M. 2013. Cytochrome P450 enzymes in drug metabolism: regulation of gene expression, enzyme activities, and impact of genetic variation. Pharmacol Ther, 138, 103–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Niu X, Qian Z, Qian J. & Xuan B. 2015. The c-Jun N-terminal kinase inhibitor SP600125 inhibits human cytomegalovirus replication. J Med Virol, 87, 2135–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JH, Chung TD & Oldenburg KR 1999. A Simple Statistical Parameter for Use in Evaluation and Validation of High Throughput Screening Assays. J Biomol Screen, 4, 67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1. (A) Valspodar blocks IE1 expression of HCMV infection. NHDF cells mock-infected or infected with AD169 (MOI:1) untreated (DMSO) and treated at -60, 0, and 30 minutes (mins) post-infected with valspodar or −60 minutes post with heparin (50μg/ml) were harvested at 24hpi. The total cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis using an anti-IE1 (lanes 1–9) or anti-GAPDH (lanes 9–16) antibodies. The molecular weight markers and targeted polypeptides are indicated. (B) Anti-p-glycoprotein antibody does not block a HCMV infection. NHDF cells preincubated with anti-p-glycoprotein antibody (UIC-2), anti-MRP1, and isotype control (0–40ug/ml) for 1hour at 37oC were infected with AD169R (moi: 0.5) and analyzed for GFP positive cells at 24hpi using a Celigo Cytometer. The data points represent triplicate of each time point and the error bars are the standard error.