Abstract

Fermentation strategies for production of high concentrations of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) [P(3HB-co-3HV)] with different 3-hydroxyvalerate (3HV) fractions by recombinant Escherichia coli harboring the Alcaligenes latus polyhydroxyalkanoate biosynthesis genes were developed. Fed-batch cultures of recombinant E. coli with the pH-stat feeding strategy facilitated production of high concentrations and high contents of P(3HB-co-3HV) in a chemically defined medium. When a feeding solution was added in order to increase the glucose and propionic acid concentrations to 20 g/liter and 20 mM, respectively, after each feeding, a cell dry weight of 120.3 g/liter and a relatively low P(3HB-co-3HV) content, 42.5 wt%, were obtained. Accumulation of a high residual concentration of propionic acid in the medium was the reason for the low P(3HB-co-3HV) content. An acetic acid induction strategy was used to stimulate the uptake and utilization of propionic acid. When a fed-batch culture and this strategy were used, we obtained a cell concentration, a P(3HB-co-3HV) concentration, a P(3HB-co-3HV) content, and a 3HV fraction of 141.9 g/liter, 88.1 g/liter, 62.1 wt%, and 15.3 mol%, respectively. When an improved nutrient feeding strategy, acetic acid induction, and oleic acid supplementation were used, we obtained a cell concentration, a P(3HB-co-3HV) concentration, a P(3HB-co-3HV) content, and a 3HV fraction of 203.1 g/liter, 158.8 g/liter, 78.2 wt%, and 10.6 mol%, respectively; this resulted in a high level of productivity, 2.88 g of P(3HB-co-3HV)/liter-h.

Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) are intracellular carbon and energy reserve materials that are accumulated by a variety of microorganisms under certain unbalanced growth conditions (1, 7, 12, 19, 23). Since PHAs possess thermoplastic or elastomeric properties depending on the monomer composition and are completely biodegradable when they are disposed, they have been considered good candidates for biodegradable polymers (9). Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) [P(3HB)] is accumulated by numerous microorganisms and is the best-characterized PHA (12, 23). Several bacteria, such as Ralstonia eutropha, Alcaligenes latus, Azotobacter vinelandii, methylotrophs, and recombinant Escherichia coli harboring the heterologous PHA biosynthesis genes, have been employed for efficient production of P(3HB) (12, 13). However, P(3HB) is a highly crystalline and brittle homopolymer, which restricts its use to a limited range of applications (9). Because of this, it has been suggested that poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) [P(3HB-co-3HV)] is better than P(3HB) because it is more flexible and stronger (7, 9). P(3HB-co-3HV) has been produced on a fairly large scale by fed-batch cultures of R. eutropha from glucose and propionic acid (3).

A major problem in commercialization of PHAs as substitutes for conventional petrochemical-based polymers is the high production cost of these compounds (3, 4). Much effort has been devoted to lowering the production cost of PHAs by developing better bacterial strains and more efficient fermentation and economical recovery processes. In the case of the P(3HB) homopolymer, several processes which result in production of high concentrations of P(3HB) with a high level of productivity have been developed (12, 13). In particular, it has been shown that recombinant E. coli harboring the heterologous PHA biosynthesis genes has several advantages over wild-type PHA producers; these advantages include a wide range of utilizable carbon sources, accumulation of a large amount of P(3HB) with a high level of productivity, and the fragility of cells, which allows easy recovery of PHA (8, 12, 14). Recently, we reported that an unprecedentedly high concentration of P(3HB) (141.6 g/liter) and a high level of productivity [4.63 g of P(3HB)/liter-h) could be obtained with a fed-batch culture of recombinant E. coli harboring the A. latus PHA biosynthesis genes (6). Therefore, we decided to determine if P(3HB-co-3HV) copolymer could also be produced at a high level of efficiency by recombinant E. coli harboring the A. latus PHA biosynthesis genes. There have been several reports of production of high concentrations of P(3HB-co-3HV) by wild-type PHA producers, such as R. eutropha (11, 18, 24), A. latus (20), A. vinelandii (17), Alcaligenes sp. (10), and Paracoccus denitrificans (26). The highest level of copolymer P(3HB-co-3HV) productivity obtained so far was 2.55 g of PHA/liter-h by a fed-batch culture of R. eutropha (11). If P(3HB-co-3HV) can be produced by recombinant E. coli with a similar or higher level of productivity, the other advantages of recombinant E. coli described above should reduce the overall cost of production of P(3HB-co-3HV).

In this paper, we describe a cultivation strategy for production of a high concentration of P(3HB-co-3HV) with a high level of productivity. Strategies for producing P(3HB-co-3HV) with different 3-hydroxyvalerate (3HV) mole fractions are also described.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmid DNA.

The E. coli strain used in this study was XL1-Blue (supE44 hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi relA1 lacF′[proAB+ lacIq lacZΔM15 Tn10(tetr)]) (15). Plasmid pJC4 harboring the A. latus PHA biosynthesis genes and the parB locus of plasmid R1 has been described previously (6).

Culture conditions.

Cells were maintained as a 20% (vol/vol) glycerol stock preparation at −80°C after growth in Luria-Bertani medium. Seed and fed-batch cultures were grown in chemically defined MR medium (pH 6.9) (25). Separately sterilized glucose and thiamine were added to MR medium at final concentrations of 20 g/liter and 10 mg/liter, respectively. For production of P(3HB-co-3HV), propionic acid was used as a cosubstrate in order to provide the precursors of 3HV monomers (28). For the acetic acid induction experiments, MR medium was supplemented with 2 g of tryptone (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) per liter in order to reduce the lag period (28). For the oleic acid supplementation experiments, 1 g of oleic acid (Junsei Chemical Co., Tokyo, Japan) per liter was added to MR medium (28).

For the fed-batch cultures, seed cultures were prepared by growing cells in a shaking incubator overnight at 30°C and 250 rpm. For acetic acid induction experiments, cells were cultivated in MR medium supplemented with 2 g of tryptone per liter, 10 mM acetic acid, and 20 mg of thiamine per liter without glucose. Fed-batch cultures were grown at 30°C in a 6.6-liter jar fermentor (Bioflo 3000; New Brunswick Scientific Co., Edison, N.J.) initially containing 1.6 liters of MR medium. The culture pH was controlled at 6.9 except for short periods of nutrient feeding (see below) by adding 28% (vol/vol) ammonia water. The dissolved oxygen concentration was controlled (see below) by automatically changing the agitation speed to 1,000 rpm and adjusting the pure oxygen percentage. During the active PHA synthesis phase, the dissolved oxygen concentration was maintained at 1 to 3% of air saturation (25). The feeding solution contained (per liter) 700 g of glucose, 15 g of MgSO4 · 7H2O, 250 mg of thiamine, and different amounts of propionic acid. The pH-stat feeding strategy was employed for fed-batch cultures. When the pH rose to a value greater than its setpoint (pH 6.9) by 0.1 pH unit, an appropriate volume of feeding solution was automatically added in order to increase the glucose concentration in the culture medium to 20 g/liter (25). The propionic acid concentration in the culture medium was increased depending on the ratio of glucose to propionic acid in the feeding solution. For the fed-batch cultures supplemented with oleic acid, oleic acid was added so that each dose increased the concentration of oleic acid in the culture by 1 g/liter.

Analytical procedures.

Cell growth was monitored by measuring the absorbance at 600 nm with a model DU Series 600 spectrophotometer (Beckman, Fullerton, Calif.). The cell concentration, defined as the dry weight of cells per liter of culture broth, was determined by weighing dry cells as described previously (15). PHA concentrations were determined with a gas chromatograph (model HP5890; Hewlett-Packard, Wilmington, Del.) by using n-benzoic acid as the internal standard (2). The PHA content was defined as the percent ratio of PHA concentration to cell concentration.

The concentration of propionic acid in the culture medium was measured by high-performance liquid chromatography by using a model L-3300 RI monitor, a model L-600 pump, and a model D-2500 chromatointegrator, (all obtained from Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with an ion-exchange column (type HPX-87H; 300 by 7.8 mm; Aminex, Hercules, Calif.); 0.01 N H2SO4 was the mobile phase.

RESULTS

Cell growth and P(3HB-co-3HV) accumulation in flask cultures.

The characteristics of cell growth and P(3HB-co-3HV) production were first examined by growing flask cultures of recombinant E. coli XL1-Blue(pJC4) under various conditions. The results are summarized in Table 1. When the recombinant E. coli XL1-Blue(pJC4) was cultivated in a chemically defined medium containing 20 g of glucose per liter and 20 mM propionic acid, the cell dry weight, PHA concentration, and PHA content obtained were 4.6 g/liter, 2.6 g/liter, and 56.8 wt%, respectively. The cell and PHA concentrations, as well as the PHA content, could be increased by induction with 10 mM acetic acid. In the culture without acetic acid induction, the 3HV fraction was increased significantly by adding oleic acid. A high PHA concentration (5.6 g/liter) and a PHA content of 74.0 wt% with a relatively high 3HV fraction (18.1 mol%) could be obtained by using acetic acid induction and oleic acid supplementation. Therefore, P(3HB-co-3HV) can be efficiently produced by using acetic acid induction and/or oleic acid supplementation with recombinant E. coli harboring the A. latus PHA biosynthesis genes.

TABLE 1.

Production of P(3HB-co-3HV) by recombinant E. coli XL1-Blue(pJC4) incubated under various conditions at 30°C for 60 h

| Culture conditions | Cell dry wt (g/liter) | PHA concn (g/liter) | PHA content (wt%) | 3HV fraction (mol%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose (20 g/liter) + 20 mM propionic acid | 4.6 | 2.6 | 56.8 | 7.2 |

| Glucose (20 g/liter) + 20 mM propionic acid + acetic acid induction | 7.9 | 5.9 | 74.8 | 13.8 |

| Glucose (20 g/liter) + 20 mM propionic acid + oleic acid supplementation | 5.2 | 3.2 | 61.2 | 19.5 |

| Glucose (20 g/liter) + 20 mM propionic acid + acetic acid induction + oleic acid supplementation | 7.5 | 5.6 | 74.0 | 18.1 |

P(3HB-co-3HV) production by fed-batch cultures.

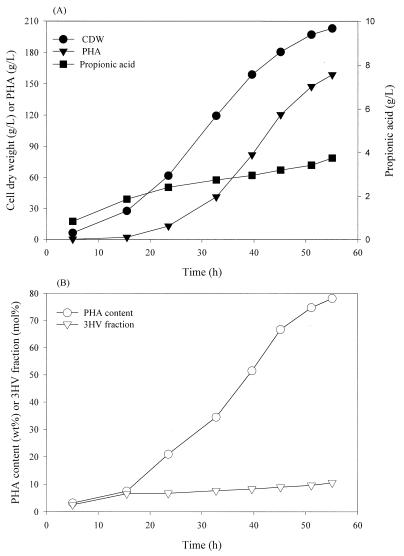

Based on the flask culture results, fed-batch cultures of recombinant E. coli XL1-Blue(pJC4) were used to produce P(3HB-co-3HV) with several different nutrient feeding strategies. First, a nutrient solution was added so that each dose increased the concentration of propionic acid in the culture by 20 mM. Figure 1 shows the time profiles of cell growth and PHA production. The cell concentration, PHA concentration, PHA content, and 3HV fraction obtained in 56.8 h were 120.3 g/liter, 51.1 g/liter, 42.5 wt%, and 10 mol%, respectively. The maximum 3HV fraction in PHA was 13.8 mol% at 32.2 h. Propionic acid accumulated continuously in the medium to a concentration of 22.6 g/liter.

FIG. 1.

Time profiles for cell dry weight (CDW), PHA concentration, and residual propionic acid concentration in the medium (A) and PHA content and 3HV fraction in PHA (B) during fed-batch culture of strain XL1-Blue(pJC4). The feeding solution was added in order to increase the concentrations of glucose and propionic acid to 20 g/liter and 20 mM, respectively, after each feeding.

Fed-batch culture with acetic acid induction or oleic acid supplementation.

It has been shown that the mechanisms for uptake and degradation of propionic acid in E. coli seem to be the same as the mechanisms for uptake and degradation of acetic acid (16, 21, 28). Based on the previous findings and the results obtained with flask cultures, the conditions that result in more efficient uptake and utilization of acetic acid (namely, induction with acetic acid or oleic acid) were used with fed-batch cultures. To investigate the effect of acetic acid induction, cells were first grown on acetic acid until the absorbance at 600 nm was 0.8. Then pH-stat nutrient feeding was started in order to increase the glucose and propionic acid concentrations to 20 g/liter and 20 mM, respectively, after each feeding. Figure 2 shows the time profiles for cell and PHA concentrations, PHA content, and the 3HV fraction during this experiment. The cell concentration, PHA concentration, and PHA content obtained in 50.9 h after acetic acid induction were 141.9 g/liter, 88.1 g/liter, and 62.1 wt%, respectively. The maximum 3HV fraction in PHA was 17 mol% at 34.1 h. Therefore, the cell concentration, PHA concentration, and PHA content could all be increased by acetic acid induction. Even with acetic acid induction, propionic acid still accumulated, but to a lesser extent (up to 11 g/liter).

FIG. 2.

Time profiles for cell dry weight (CDW), PHA concentration, and residual propionic acid concentration in the medium (A) and PHA content and 3HV fraction in PHA (B) during fed-batch culture of XL1-Blue(pJC4) after induction with 10 mM acetic acid. The feeding solution was added in order to increase the concentrations of glucose and propionic acid to 20 g/liter and 20 mM, respectively, after each feeding.

Next, a fed-batch culture of recombinant E. coli with oleic acid supplementation was studied. The final cell and PHA concentrations and PHA content after 53.5 h were 129.6 g/liter, 54.1 g/liter, and 41.8 wt%, respectively. The 3HV fraction in PHA was increased from 10 to 19.3 mol% by oleic acid supplementation (time profiles not shown). Again, there was accumulation of propionic acid, but the amount of propionic acid was less than the amount observed in the absence of oleic acid supplementation or acetic acid induction.

Reduction of propionic acid accumulation.

Even though acetic acid induction and oleic acid supplementation could enhance propionic acid utilization, propionic acid still accumulated. To reduce the accumulation of propionic acid during culture, a feeding solution containing a lower propionic acid concentration was used without acetic acid induction or oleic acid supplementation. This solution was designed to increase the propionic acid concentration to 5 mM after each feeding. The cell concentration, PHA concentration, and PHA content obtained in 51.9 h were 179.4 g/liter, 134.7 g/liter, and 75.1 wt%, respectively. The maximum fraction of 3HV in PHA was 3.3 mol%. The final residual concentration of propionic acid was 5.2 g/liter, which is much lower than the concentration obtained during the three fed-batch culture experiments described above (time profiles not shown).

Figure 3 shows the time profiles for cell concentration, PHA concentration, and PHA content when cells were cultivated with oleic acid supplementation after acetic acid induction. In this experiment, the nutrient solution was added in order to increase the propionic acid concentration to 5 mM after each feeding. The cell concentration, PHA concentration, and PHA content obtained in 55.1 h were 203.1 g/liter, 158.8 g/liter, and 78.2 wt%, respectively. The maximum 3HV fraction in PHA increased from 3.3 to 10.6 mol%.

FIG. 3.

Time profiles for cell dry weight (CDW), PHA concentration, and residual propionic acid concentration in the medium (A) and PHA content and 3HV fraction in PHA (B) during fed-batch culture of XL1-Blue(pJC4) with oleic acid supplementation after acetic acid induction. The feeding solution was added in order to increase the concentrations of glucose and propionic acid to 20 g/liter and 5 mM, respectively, after each feeding.

When cells were cultivated under the same conditions except that the propionic acid concentration was increased to 10 mM after each feeding, the cell concentration, PHA concentration, and PHA content obtained in 52.1 h were 189.1 g/liter, 135.1 g/liter, and 71.4 wt%, respectively (Fig. 4). The maximum 3HV fraction in PHA was 16.1 mol%. Therefore, the 3HV fraction could be increased by adding more propionic acid, while the detrimental effect of a high concentration of propionic acid could be alleviated by acetic acid induction and/or oleic acid supplementation. The results of the fed-batch culture experiments are summarized in Table 2.

FIG. 4.

Time profiles for cell dry weight (CDW), PHA concentration, and residual propionic acid concentration in the medium (A) and PHA content and 3HV fraction in PHA (B) during fed-batch culture of XL1-Blue(pJC4) with oleic acid supplementation after acetic acid induction. The feeding solution was added in order to increase the concentrations of glucose and propionic acid to 20 g/liter and 10 mM, respectively, after each feeding.

TABLE 2.

Summary of P(3HB-co-3HV) production by fed-batch cultures of recombinant E. coli under various conditions

| Culture conditions | Fermentation time (h) | Cell dry wt (g/liter) | PHA concn (g/liter) | PHA content (wt%) | 3HV fraction (mol%) | 3HV yield (g of 3HV/g of propionic acid) | Productivity (g of PHA/liter-h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose added to a concn of 20 g/liter and propionic acid added to a concn of 20 mM after each feeding | 56.8 | 120.3 | 51.1 | 42.5 | 10 | 0.23 | 0.90 |

| Glucose added to a concn of 20 g/liter and propionic acid added to a concn of 20 mM after each feeding with acetic acid induction | 50.9 | 141.9 | 88.1 | 62.1 | 15.3 | 0.34 | 1.73 |

| Glucose added to a concn of 20 g/liter and propionic acid added to a concn of 20 mM after each feeding with oleic acid supplementation | 53.5 | 129.6 | 54.1 | 41.8 | 19.3 | 0.35 | 1.01 |

| Glucose added to a concn of 20 g/liter and propionic acid added to a concn of 5 mM after each feeding | 51.9 | 179.4 | 134.7 | 75.1 | 3.3 | 0.33 | 2.60 |

| Glucose added to a concn of 20 g/liter and propionic acid added to a concn of 5 mM after each feeding with acetic acid induction and oleic acid supplementation | 55.1 | 203.1 | 158.8 | 78.2 | 10.6 | 0.47 | 2.88 |

| Glucose added to a concn of 20 g/liter and propionic acid added to a concn of 10 mM after each feeding with acetic acid induction and oleic acid supplementation | 52.1 | 189.1 | 135.1 | 71.4 | 14.8 | 0.43 | 2.59 |

DISCUSSION

P(3HB-co-3HV) has been considered a better candidate for producing biodegradable plastic material than P(3HB), because it is more flexible, stronger, and easier to process. Slater et al. (22) demonstrated that P(3HB-co-3HV) could be synthesized by a special mutant (atoC fadR) strain of E. coli LS5218 harboring the R. eutropha PHA biosynthesis genes (29), because this E. coli strain allowed constitutive expression of the enzymes involved in utilization of short-chain fatty acids. However, E. coli LS5218 did not grow to a high cell density, nor did it accumulate much polymer (27). We examined other E. coli strains to determine whether they produced P(3HB-co-3HV) more efficiently (28). Non-atoC fadR E. coli strains harboring the R. eutropha PHA biosynthesis genes accumulated P(3HB-co-3HV) with 3HV fractions as high as 33 mol% from glucose and propionic acid in flask cultures.

In this study, we investigated strategies for production of P(3HB-co-3HV) by a high-cell-density culture of non-atoC fadR recombinant E. coli harboring the A. latus PHA biosynthesis genes with different 3HV fractions. Recombinant E. coli harboring the A. latus PHA biosynthesis genes produced a large amount of P(3HB) with a higher level of productivity than recombinant E. coli harboring the R. eutropha PHA biosynthesis genes (6). In a flask culture used for production of P(3HB-co-3HV), the final cell and PHA concentrations obtained with recombinant E. coli XL1-Blue(pJC4) harboring the A. latus PHA biosynthesis genes were higher than the final concentrations obtained with recombinant E. coli XL1-Blue(pSYL105) harboring the R. eutropha PHA biosynthesis genes.

When we used the fed-batch culture containing recombinant E. coli XL1-Blue(pJC4) harboring the A. latus PHA biosynthesis genes and the feeding strategy that increased the glucose and propionic acid concentrations to 20 g/liter and 20 mM, respectively, after each feeding, the cell concentration obtained was 120.3 g/liter, but the PHA content was rather low (42.5 wt%). We found that propionic acid accumulated during incubation of the fed-batch culture. The residual concentration of propionic acid after 56.8 h was as high as 22.6 g/liter, which seemed to be the reason for relatively low level of PHA. To stimulate the uptake of propionic acid, acetic acid induction experiments were carried out. The cell and PHA concentrations, the PHA content, and PHA productivity all increased when acetic acid induction was used. The residual concentration of propionic acid in the medium decreased considerably. In the fed-batch culture with oleic acid supplementation, the cell and PHA concentrations increased a little but were lower than the concentrations obtained with acetic acid induction. On the other hand, the 3HV fraction increased twofold. On the basis of these results, we reasoned that oleic acid supplementation mainly increased the 3HV fraction in PHA. The 3HV yield on propionic acid was also increased by acetic acid induction and oleic acid supplementation.

However, the high residual concentration of propionic acid in the medium and the low PHA content were problems that had to be solved for efficient production of P(3HB-co-3HV) by recombinant E. coli. In the fed-batch cultures, the feeding solution containing propionic acid was added when the glucose in the medium was depleted. Because the uptake rate of propionic acid seems to be different from the uptake rate of glucose, propionic acid accumulates if its concentration is not optimized. To decrease the level of propionic acid in the medium, we performed fed-batch culture experiments with different feeding solutions containing lower concentrations of propionic acid. When the feeding solution was added in order to increase the propionic acid concentration to 5 mM, the concentration of PHA and the PHA content increased and productivity was higher, while the residual concentration of propionic acid was much lower. With acetic acid induction and oleic acid supplementation, the PHA concentration and the PHA content increased to 158.8 g/liter and 78.2 wt%, respectively. The productivity was as high as 2.88 g of P(3HB-co-3HV)/liter-h. When the feeding solution was added in order to increase the propionic acid concentration to 10 mM with acetic acid induction and oleic acid supplementation, the concentration of PHA and the PHA content decreased slightly compared to the values obtained when 5 mM propionic acid feeding was used. However, the final 3HV fraction was higher (14.8 mol%). On the basis of these results, we concluded that a high concentration of PHA and a high PHA content could be obtained by using a feeding solution with a low concentration of propionic acid, but the 3HV fraction in PHA was low. Table 2 also shows that when the feeding solution containing a low propionic acid concentration was added, the 3HV yield on propionic acid increased.

Prior to this study, it was reported that the highest concentration of P(3HB-co-3HV), a PHA content, and a 3HV fraction were 117 g/liter, 74 wt%, and 4.3 mol%, respectively, when a fed-batch culture of R. eutropha was used and that the highest level of PHA productivity was 2.55 g of P(3HB-co-3HV)/liter-h (11). However, when the 3HV fraction in the PHA increased to 14.3 mol%, the cell and PHA concentrations and the PHA content decreased to 129 g/liter, 74 g/liter, and 57 wt%, respectively, which resulted in a level of productivity of 1.67 g of P(3HB-co-3HV)/liter-h. The results reported in this paper show that a higher concentration of PHA and a higher PHA content with a relatively high 3HV fraction can be obtained with a fed-batch culture of recombinant E. coli harboring the A. latus PHA biosynthesis genes.

In order to compare the processes for production of P(3HB-co-3HV) by recombinant E. coli with other processes in which wild-type organisms are used, an economic evaluation of the processes was carried out by using the method described previously (4). In this evaluation, a P(3HB-co-3HV) production scale of 100,000 metric tons per year was used. According to the economic evaluation of the process for production of PHA having a 3HV fraction of 14.3 mol% by R. eutropha, the PHA production cost was as high as $9.75/kg of PHA when the recovery method involved surfactant-hypochlorite digestion. For the process described here in which recombinant E. coli was used, the PHA production cost with a 3HV fraction of 10.6 mol% was only $5.05/kg of PHA when the same recovery method was used. Furthermore, when PHA was recovered from E. coli cells by the simple NaOH digestion method described recently (5), the PHA production cost was $3.95/kg of PHA.

In conclusion, P(3HB-co-3HV) having a 3HV fraction of 3 to 20 mol% could be efficiently produced by recombinant E. coli containing the A. latus PHA biosynthesis genes by simply varying the propionic acid concentration in the feeding solution. Our results along with other advantages of employing recombinant E. coli described previously, should make recombinant E. coli a good candidate for production of PHA. Recently, research on production of PHA by a transgenic plant has been carried out. However, the concentration and yield of PHA should be increased in order to reduce the PHA production cost to a value close to the cost of starch production. Therefore, PHA production will rely on efficient bacterial fermentation until the early 21st century, and recombinant E. coli will play an important role in this production.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology and by LG Chemicals, Ltd.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson A J, Dawes E A. Occurrence, metabolism, metabolic role, and industrial uses of bacterial polyhydroxyalkanoates. Microbiol Rev. 1990;54:450–472. doi: 10.1128/mr.54.4.450-472.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braunegg G, Sonnleitner B, Lafferty R M. A rapid gas chromatographic method for the determination of poly-β-hydroxybutyric acid in microbial biomass. Eur J Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1978;6:29–37. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byrom D. Polymer synthesis by microorganisms: technology and economics. Trends Biotechnol. 1987;5:246–250. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi J, Lee S Y. Process analysis and economic evaluation for poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) production by fermentation. Bioprocess Eng. 1997;17:335–342. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi J, Lee S Y. Efficient and economical recovery of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) from recombinant Escherichia coli by simple digestion with chemicals. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1999;62:546–553. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0290(19990305)62:5<546::aid-bit6>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi J, Lee S Y, Han K. Cloning of the Alcaligenes latus polyhydroxyalkanoate biosynthesis genes and use of these genes for enhanced production of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) by recombinant Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:4897–4903. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.12.4897-4903.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doi Y. Microbial polyesters. New York, N.Y: VCH; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fidler S, Dennis D. Polyhydroxyalkanoate production in recombinant Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1992;103:231–236. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90314-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holmes P A. Biologically produced PHA polymers and copolymers. In: Bassett D C, editor. Developments in crystalline polymers. Vol. 2. London, United Kingdom: Elsevier; 1988. pp. 1–65. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jang J H, Rogers P L. Effect of levulinic acid on cell growth and poly-β-hydroxyalkanoate production by Alcaligenes sp. SH-69. Biotechnol Lett. 1996;18:219–224. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim B S, Lee S C, Lee S Y, Chang H N, Chang Y K, Woo S I. Production of poly(3-hydroxybutyric-co-3-hydroxyvaleric acid) by fed-batch culture of Alcaligenes eutrophus with substrate control using on-line glucose analyzer. Enzyme Microb Technol. 1994;16:556–561. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee S Y. Bacterial polyhydroxyalkanoates. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1996;49:1–14. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0290(19960105)49:1<1::AID-BIT1>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee S Y. Plastic bacteria? Progress and prospects for polyhydroxyalkanoate production in bacteria. Trends Biotechnol. 1996;14:431–438. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee S Y. E. coli moves into the plastic age. Nature Biotechnol. 1997;15:17–18. doi: 10.1038/nbt0197-17b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee S Y, Yim K S, Chang H N, Chang Y K. Construction of plasmids, estimation of plasmid stability, and use of stable plasmids for the production of poly(3-hydroxybutyric acid) in Escherichia coli. J Biotechnol. 1994;32:203–211. doi: 10.1016/0168-1656(94)90183-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neidhardt F C. Escherichia coli and Salmonella. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Page W J, Manchak J, Rudy B. Formation of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) by Azotobacter vinelandii UWD. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:2866–2873. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.9.2866-2873.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park C H, Damodaran V K. Effect of alcohol feeding mode on the biosynthesis of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) Biotechnol Bioeng. 1994;44:1306–1314. doi: 10.1002/bit.260441106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poirier Y, Nawrath C, Somerville C. Production of polyhydroxyalkanoates, a family of biodegradable plastics and elastomers, in bacteria and plants. Bio/Technology. 1995;13:142–150. doi: 10.1038/nbt0295-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramsay B A, Lomaliza K, Chavaric C, Dube B, Bataille P, Ramsay J A. Production of poly-(β-hydroxybutyric-co-β-hydroxyvaleric) acids. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:2093–2098. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.7.2093-2098.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rhie H G, Dennis D. The function of ackA and pta genes is necessary for poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) synthesis in recombinant pha+Escherichia coli. Can J Microbiol. 1995;41:200–206. doi: 10.1139/m95-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Slater S C, Gallaher T, Dennis D E. Production of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) in a recombinant E. coli strain. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:1089–1094. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.4.1089-1094.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steinbüchel A, Füchtenbusch B. Bacterial and other biological systems for polyester production. Trends Biotechnol. 1998;16:419–427. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(98)01194-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steinbüchel A, Pieper U. Production of a copolyester of 3-hydroxybutyric acid and 3-hydroxyvaleric acid from single unrelated carbon sources by a mutant of Alcaligenes eutrophus. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1992;37:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang F, Lee S Y. Production of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) by fed-batch culture of filamentation-suppressed recombinant Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4765–4769. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.12.4765-4769.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamane T, Chen X F, Ueda S. Polyhydroxyalkanoate synthesis from alcohols during the growth of Paracoccus denitrificans. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;135:207–211. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yim K S, Lee S Y, Chang H N. Effect of acetic acid on poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) synthesis in recombinant Escherichia coli. Korean J Chem Eng. 1995;12:264–268. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yim K S, Lee S Y, Chang H N. Synthesis of poly-(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) by recombinant Escherichia coli. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1996;49:495–503. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0290(19960305)49:5<495::AID-BIT2>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang H, Bias V O, Gonyer K, Dennis D. Production of polyhydroxyalkanoates in sucrose-utilizing recombinant Escherichia coli and Klebsiella strains. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:1198–1205. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.4.1198-1205.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]