Abstract

Aims:

Metabolic function/dysfunction is central to aging biology. This is well illustrated by the Polymerase Gamma (POLG) mutant mouse where a key residue of the mitochondrial DNA polymerase is mutated (D257A), causing loss of mitochondrial DNA stability and dramatically accelerated aging processes. Given known cardiac phenotypes in the POLG mutant, we sought to characterize the course of cardiac dysfunction in the POLG mutant to guide future intervention studies.

Materials and Methods:

Cardiac echocardiography and terminal hemodynamic analyses were used to define the course of dysfunction in the right and left cardiac ventricles in the POLG mutant. We also conducted RNA-seq analysis on cardiac right ventricles to identify mechanisms engaged by severe metabolic dysfunction and compared this analysis to several publically available datasets.

Key Findings:

Interesting sex differences were noted as female POLG mutants died earlier than male POLG mutants and LV chamber diameters were impacted earlier in females than males. Moreover, male mutants showed LV wall thinning while female mutant LV walls were thicker. Both males and females displayed significant RV hypertrophy. POLG mutants displayed a gene expression pattern associated with inflammation, fibrosis, and heart failure. Finally, comparative omics analyses of publically available data provide additional mechanistic and therapeutic insights.

Significance:

Aging-associated cardiac dysfunction is a growing clinical problem. This work uncovers sex-specific cardiac responses to severe metabolic dysfunction that are reminiscent of patterns seen in human heart failure and provides insights to the molecular mechanisms engaged downstream of severe metabolic dysfunction that warrant further investigation.

Introduction

Aging is a complex process that impacts all organ systems of the body, and their interactions. Many cellular and molecular mechanisms have been implicated in the biology of aging, including chronic low-grade inflammation, cellular senescence, DNA damage, telomere shortening, mTOR signaling, ROS generation, loss of proteostasis, and mitochondrial dysfunction (1). These mechanisms are related and subject to significant environmental influence (2). Mitochondrial function and mitochondria-derived signals are central to aging pathology (3, 4). We sought a model of accelerated aging given advantages in defining shorter intervention/treatment time windows and robust phenotypic changes to facilitate unbiased approaches to identify aging-associated mechanisms. Further, accelerated aging models reduce both time and funds required relative to experiments conducted with natural aging.

Mutations in the mitochondrial DNA polymerase, Polymerase Gamma (POLG) have been associated with a number of mitochondrial diseases in humans (reviewed in 5). Several POLG mutant mouse models have been developed that broadly display accelerated aging phenotypes including hair loss, weight loss, brittle bones, early mortality, and cardiac remodeling (e.g. 6–9). The POLG D257A point mutant mouse lacks proof reading capacity in the mitochondrial DNA polymerase, resulting in reduced mitochondrial DNA integrity (10). These mice have been reported to display phenotypes consistent with accelerated cardiac aging, though literature reporting the degree of cardiac dysfunction in these animals is varied (6, 11–14).

Results

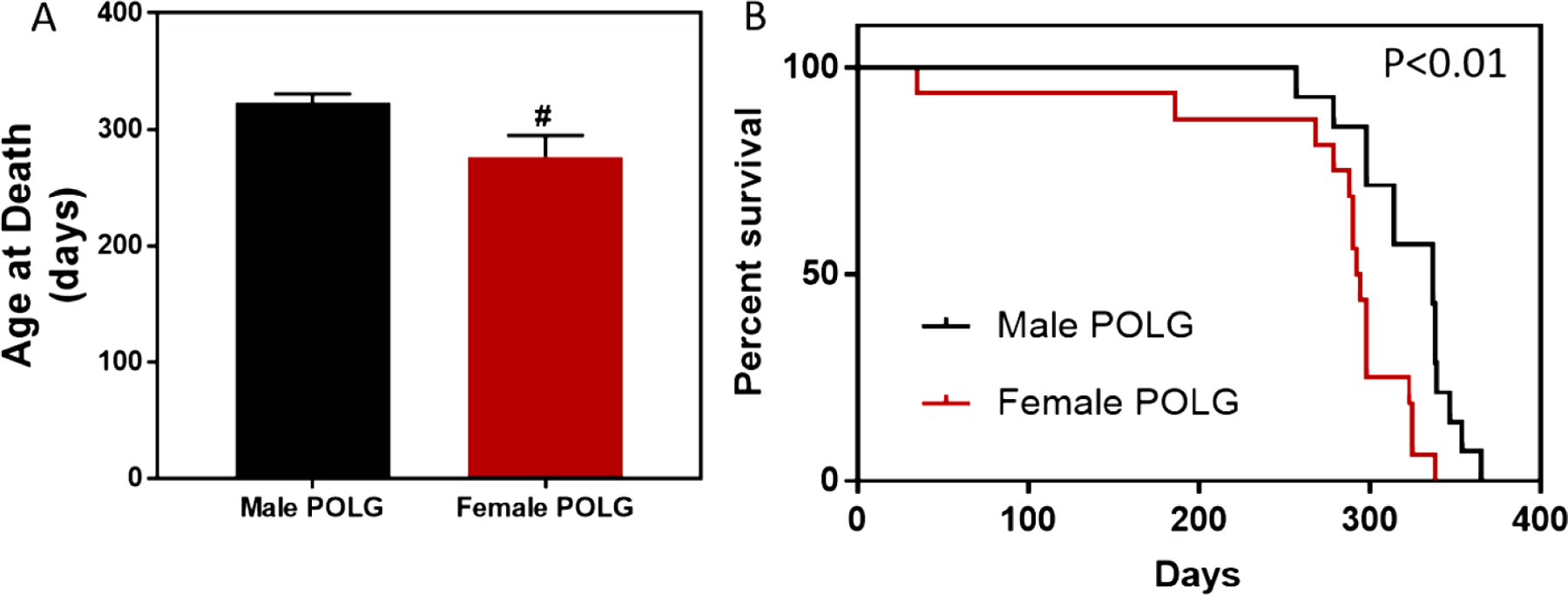

As previously reported, POLG mutants displayed gross phenotypes consistent with accelerated-aging, including hair loss, weight loss, frail bones, kyphosis, and early mortality (6). Given know variations in disease pathology/progression based on environmental factors that vary from institution to institution (e.g. diet, light cycle, housing conditions and density, vivarium traffic, elevation, etc.) we embarked on a pilot survival study to determine the POLG life-span locally. Here, we include both natural death and veterinarian directed euthanasia due to severely deteriorated condition as death (lack of response to stimulation, loss of >20% of body weight, Body Condition Score <2). The average age of death for male POLG mice was 322.5 days of age (+/− 8.154, N=14) while female average survival was only to 276.7 days (Figure 1A). These data are in agreement with significantly worsened outcomes in a classical survival analysis in the female relative to male POLG mutants (Figure 1B, Log-rank test p=0.0026 and Gehan-Breslow-Wokcoxon test p=0.0073).

Figure 1. Sex difference in POLG mutant survival.

Female POLG mutant mice lived an average of 277 days while male POLG mutants lived an average of 323 days (A, # indicates P<0.05, t test). Survival analysis also showed that female mutants died sooner than males (B, Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon p=0.0073, Pantel-Cox p=0.0026, N=14 male and N=16 female).

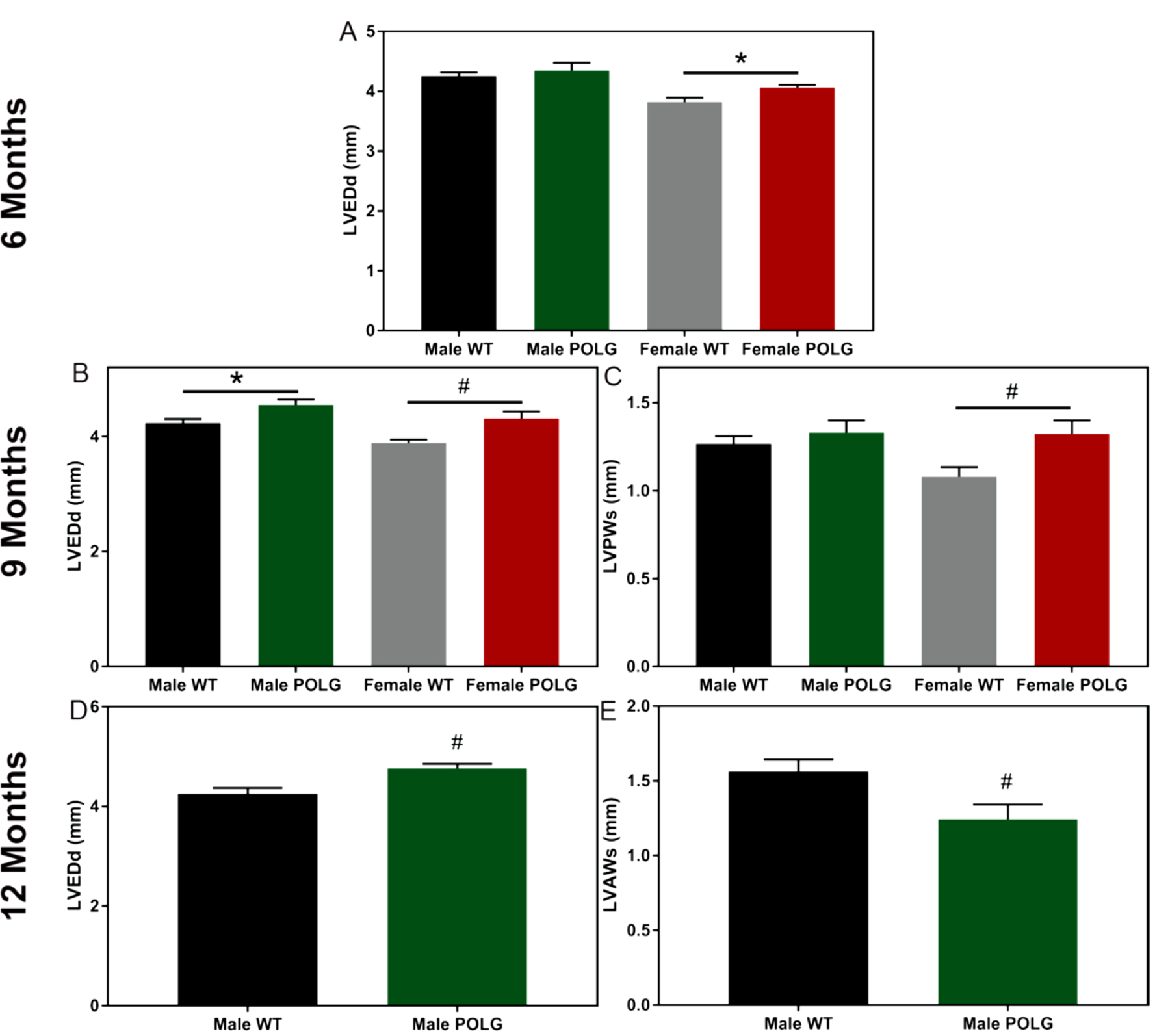

Given these findings, we sought to assess indices of cardiac aging in male and female POLG mutant and WT control littermates. Echocardiographic imaging was conducted every three months beginning at 6 months of age. Due to differential survival, females were subjected to echo imaging at 6 and 9–10 months of age while males were imaged at 6, 9, and 11–12 months of age with the last echo imaging session being timed with onset of accelerated deterioration of condition. Though no differences were noted in males at 6 months of age, females POLG mutants displayed increased left ventricular diastolic diameter relative to WT controls (Figure 2A). At 9 months of age, both male and female POLG mutants had increased left ventricular diastolic chamber dimensions (Figure 2B). Surprisingly, both male and female POGL mutants displayed apparent improved systolic function as measured by ejection fraction (EF) and fractional shortening (FS) relative to WT littermates (supplemental Table 1). However, it is likely that these changes reflect compensatory mechanisms engaged in the presence of decreased heart rates in the POLG mutants undergoing functional assessment. Also at 9 months of age, female POLG mutants showed increased LV wall thickness relative to controls (Figure 2C). Interestingly, at 11–12 months of age, male POLG mutants displayed LV wall thinning and increased chamber size relative to controls, consistent with a dilated cardiomyopathy phenotype (Figure 2D and 2E). This indicates sex-specific remodeling responses to metabolic dysfunction in the heart.

Figure 2. LV chamber remodeling in the POLG mutant.

At 6 months of age, female but not male POLG mutant mice had larger LV chambers relative to controls as indicated by diastolic diameter (A). Both male and female POLG mutants displayed larger LV chamber dimensions at 9 months of age (B). Female POLG mutants also displayed LV hypertrophy as indicated by increased posterior wall thickness at 9 months (C). POLG mutant males displayed increased diastolic diameter (D) as well as decreased anterior wall thickness (E). Female mice did not survive to 12 months of age. # indicates p<0.05 and * indicates ANOVA posthoc did not reach significance though t-test was p<0.05 (n=7–10).

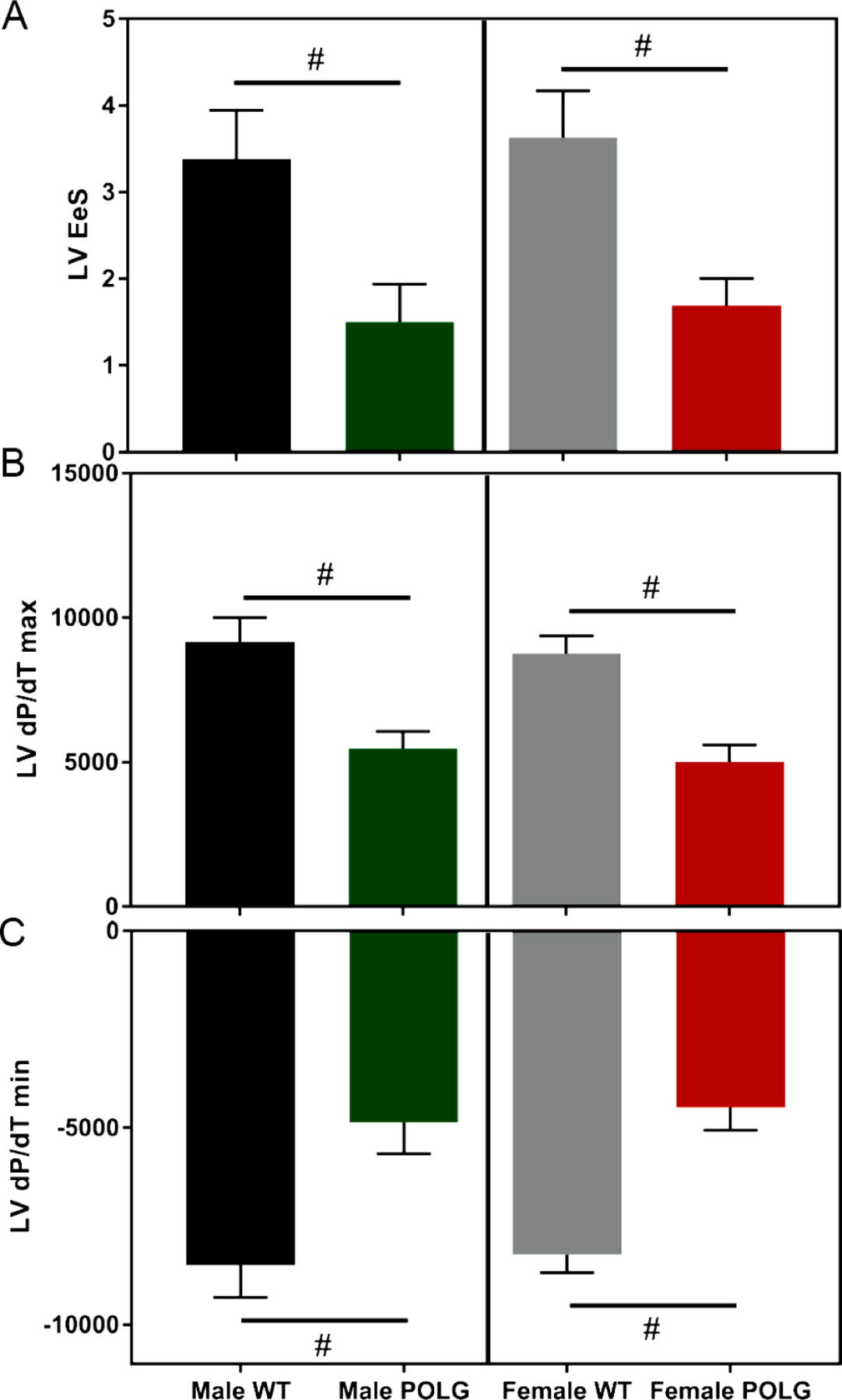

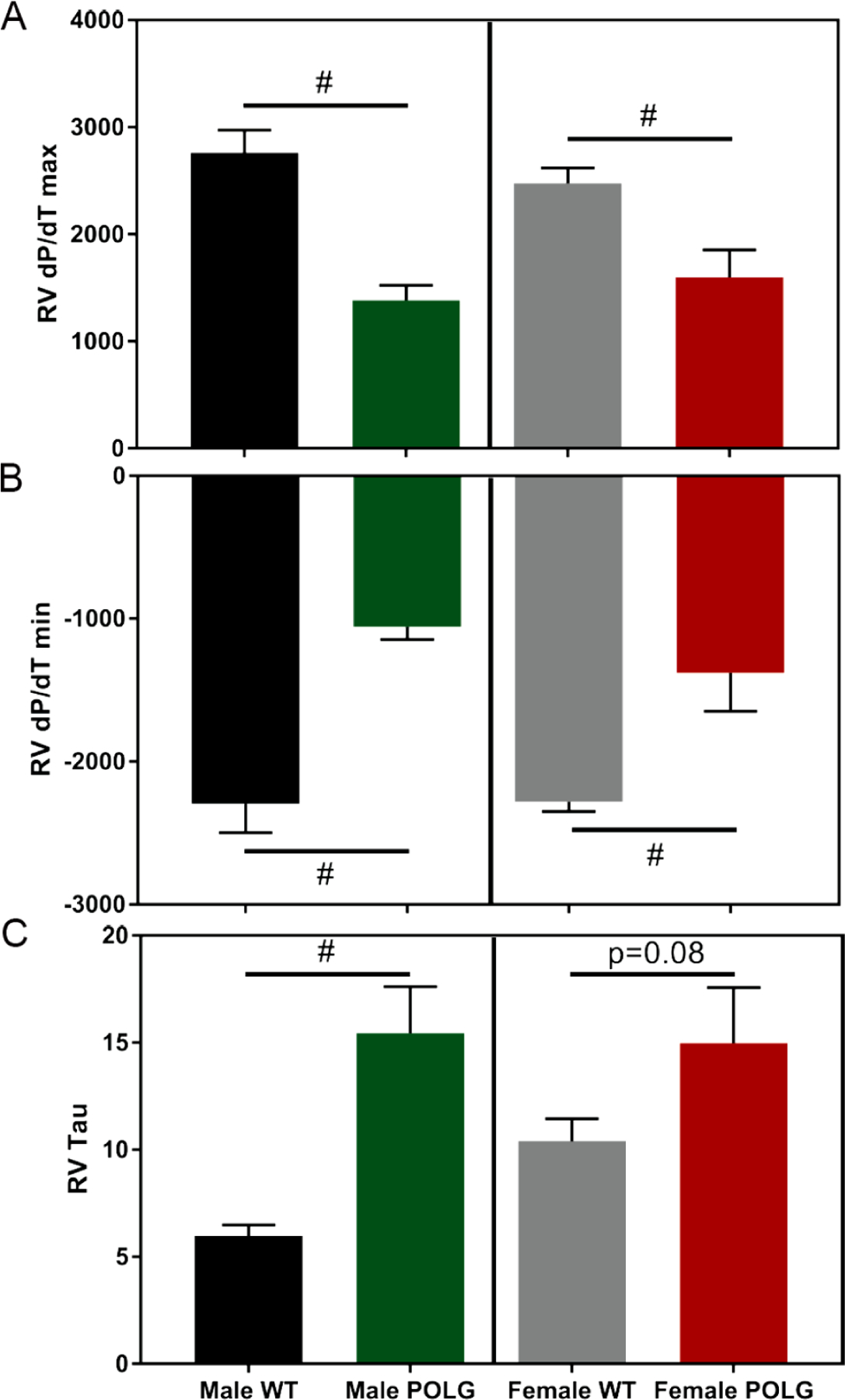

Mice were also subjected to invasive hemodynamic measurements of LV and RV function (males 11–12 months of age and females 9–10 months of age). Both male and female POLG mice displayed decreased LV contractility relative to controls as illustrated by decreased Ees and decreased dP/dT max and slowed relaxation as indicated by dP/dT min (Figure 3). In the RVs, despite no change in baseline pressure, the POLG mutants showed decreased dP/dT max and dP/dT min values indicating decreased kinetics of contraction and relaxation, which is consistent with increased Tau values in the POLG (Figure 4). To control for differences in heart rate, dP/dT max and dP/dT min values were divided by heart rate (dP/dT:HR). Still, the POLG mutants displayed decreased contraction and relaxation indices (supplemental Figure 1). Further, LV pressure at dP/dT max (51.6 POLG vs 58.8 WT, p=0.01) and max power (14981 POLG vs 23406 WT, p=0.02) were lower in the POLG mutants, indicating systolic dysfunction.

Figure 3. Terminal hemodynamic assessment of LV function.

Male and female POLG mutants displayed decreased LV systolic and diastolic function as indicated by decreased Ees (A), dP/dT max (B), and dP/dT min (C). # indicates p<0.05 via t-test vs same sex/age WT littermates. Females are 9–10 months of age and males are 11–12 months of age (n=3 male POLG, n=3 male WT, n=5 female POLG, n=8 female WT).

Figure 4. Terminal hemodynamic assessment of RV function.

Male and female POLG mutants displayed decreased RV systolic and diastolic function as indicated by decreased dP/dT max (A) and dP/dT min (B). Similarly, Tau, an indicator of time required for relaxation, was increased in the POLG mutant males, though only trended toward an increase in females (D). # indicates p<0.05 via t-test vs same sex/age littermate controls. Females are 9–10 months of age and males 11–12 months of age (n=4 male POLG, n=4 male WT, n=6 female POLG, n=8 female WT).

Consistent with a lack of wall thickening in the male POLG cardiac echos, LV weights normalized to tibia length only indicated LV hypertrophy in female POLG mice (Figure 5A) while RV hypertrophy was noted in POLG mutants from both sexes (Figure 5B). Furthermore, no differences in lung weights (wet weight) suggest that RV remodeling and dysfunction is not secondary to gross pulmonary remodeling or edema (Figure 5C), though liver weights clearly indicate hepatic venous congestion, which is a hallmark of RV failure (Figure 5D, 15–17).

Figure 5. Gravimetric analysis of POLG mutation induced remodeling.

Female POLG mutant mice had larger LVs that WT mice while no trend was observed in males (A). Both male and female POLG mutants showed significant RV hypertrophy relative to controls (B) but no indication of pulmonary edema (C). POLG females also showed increased liver weights, indicating hepatic venous congestion, often observed in RV failure. # indicates p<0.05 vs same sex/age WT littermates. Females are 9–10 months of age and males are 11–12 months of age (n=6–7 per group).

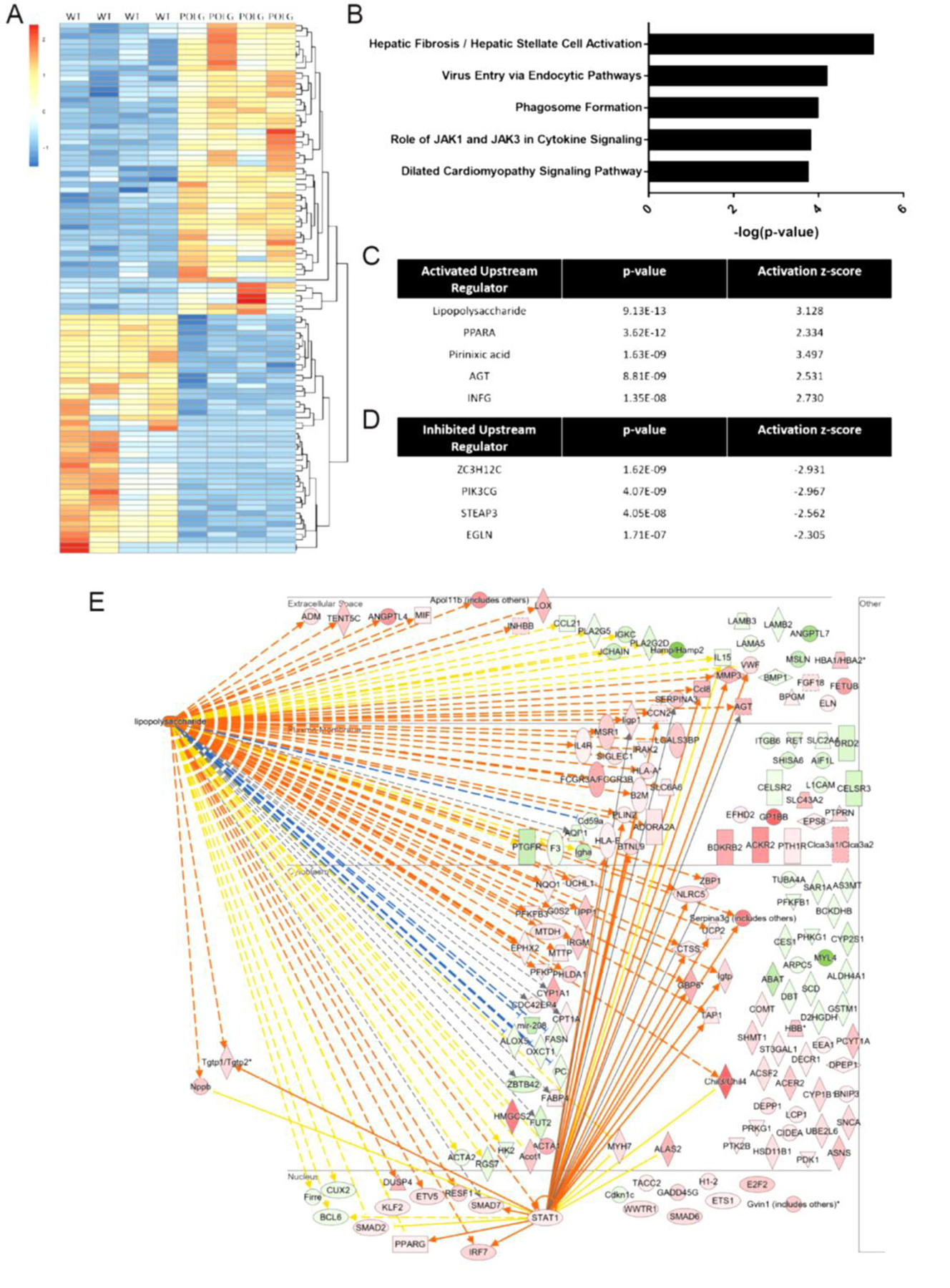

To gain insights regarding mechanisms engaged in the presence of severe metabolic dysfunction and associated with RV failure, RNA-seq analysis was conducted on RV tissue in POLG and WT mice (N=4, all females). 455 genes were differentially expressed between WT and POLG RVs (Log2FC>I0.05I, adjusted p<0.05, top 100 displayed in heatmap Figure 6A). Not surprisingly, IPA (Qiagen) analysis of these genes indicated significant alterations in pathways associated with hepatic fibrosis, endocytic pathways, phagosome formation, JAK1/JAK3 signaling, and dilated cardiomyopathy signaling (Figure 6B). Upstream analysis also identified key regulator molecules predicted to be activated or inhibited in the POLG samples relative to controls (Figure 6C and 6D). The statistically strongest prediction was for activation of LPS signaling, a dominant pro-inflammatory molecule. Gene expression changes leading to the prediction of LPS activation are shown in Figure 6E.

Figure 6. Differential gene expression in the POLG mutant RV.

RNA-seq analysis was conducted on RNA isolated from POLG mutant and WT RV tissue. Top 100 of 276 differentially expressed genes (log2FC>I1I, adjusted p<0.05) are depicted in heatmap (A). Core analysis in IPA (Qiagen) was performed on genes showing log2FC>I0.5I (455 differentially expressed genes). Top effected canonical pathways (B) as well as predicted activated upstream regulators (C) and predicted inhibited upstream regulators (D) are shown. Genes leading to the prediction of LPS activation are displayed in (E, gene symbol colors: green indicates decreased expression and red indicates increased expression; line colors: yellow indicates measured expression inconsistent with predicted activity, blue and orange lines indicate measured expression is consistent with predicted activity).

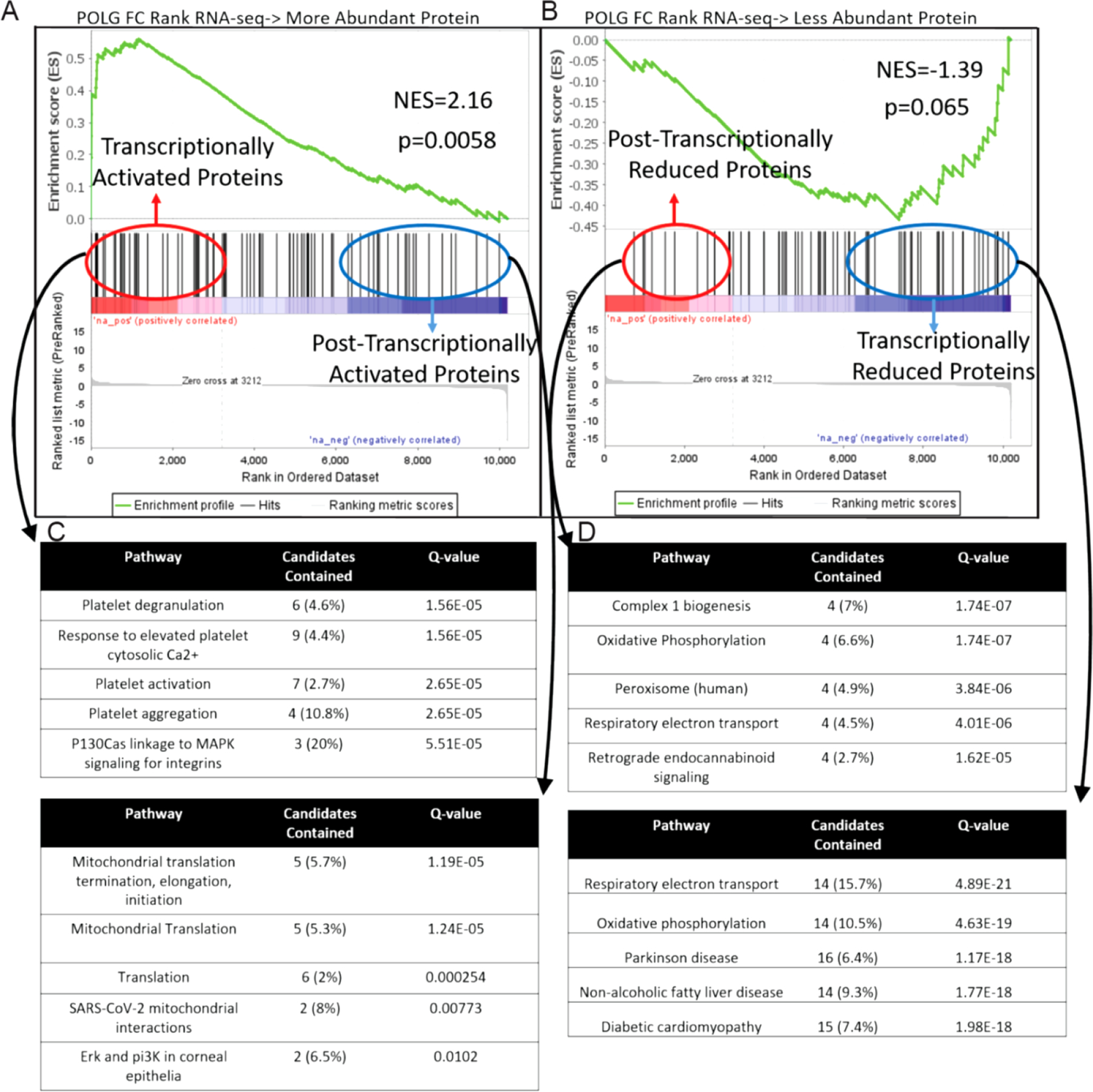

We next sought to compare our transcriptome expression data in the POLG mutant with proteome abundance data in the POLG heart (18) using Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA, Broad Inst.). A ranked list of genes based on log(2) fold change in the current POLG RNA-seq data (>10,000 genes filtered only by minimum expression) was created and tested against a list of genes encoding significantly upregulated proteins in POLG mutant hearts and again against a list of genes encoding significantly reduced proteins in POLG mutant hearts. Significant enrichment was reached for genes and proteins significantly upregulated by the POLG mutation (Figure 7A, p=0.0058) while genes and proteins with reduced expression were only suggestive of enrichment (Figure 7B, p=0.065). By identifying genes and proteins that clearly move in the same vs opposite directions with POLG mutation, we highlight proteins for which abundance is likely to be regulated by transcriptional vs post-transcriptional mechanisms. Interestingly, proteins that were upregulated consistently with transcription show clear enrichment for platelet related events (Figure 7C, consistent with decompensated heart failure (19), inflammation and tissue damage, reviewed in 20) while proteins that are upregulated post-transcriptionally are associated with the mitochondria, particularly protein translation in the mitochondria and ETC assembly (Figure 7C). Proteins that were down regulated in the POLG mutant, regardless of whether the protein change was consistent with the mRNA direction or not, were associated with active mitochondrial function (Figure 7D, e.g. electron transport chain and TCA cycle).

Figure 7. Comparison of POLG effected cardiac Transcriptome vs cardiac Proteasome.

GSEA was used to compare the conservation of gene and protein expression changes caused by POLG mutation. Proteins found to be more (A) or less abundant (B) in POLG hearts were converted into gene list and compared against the Log FC ranked RNA-seq dataset. ConcensusPath DB was then used to determine over represented pathways in proteins that were post-transcriptionally vs transcriptionally activated (C) and reduced (D) proteins.

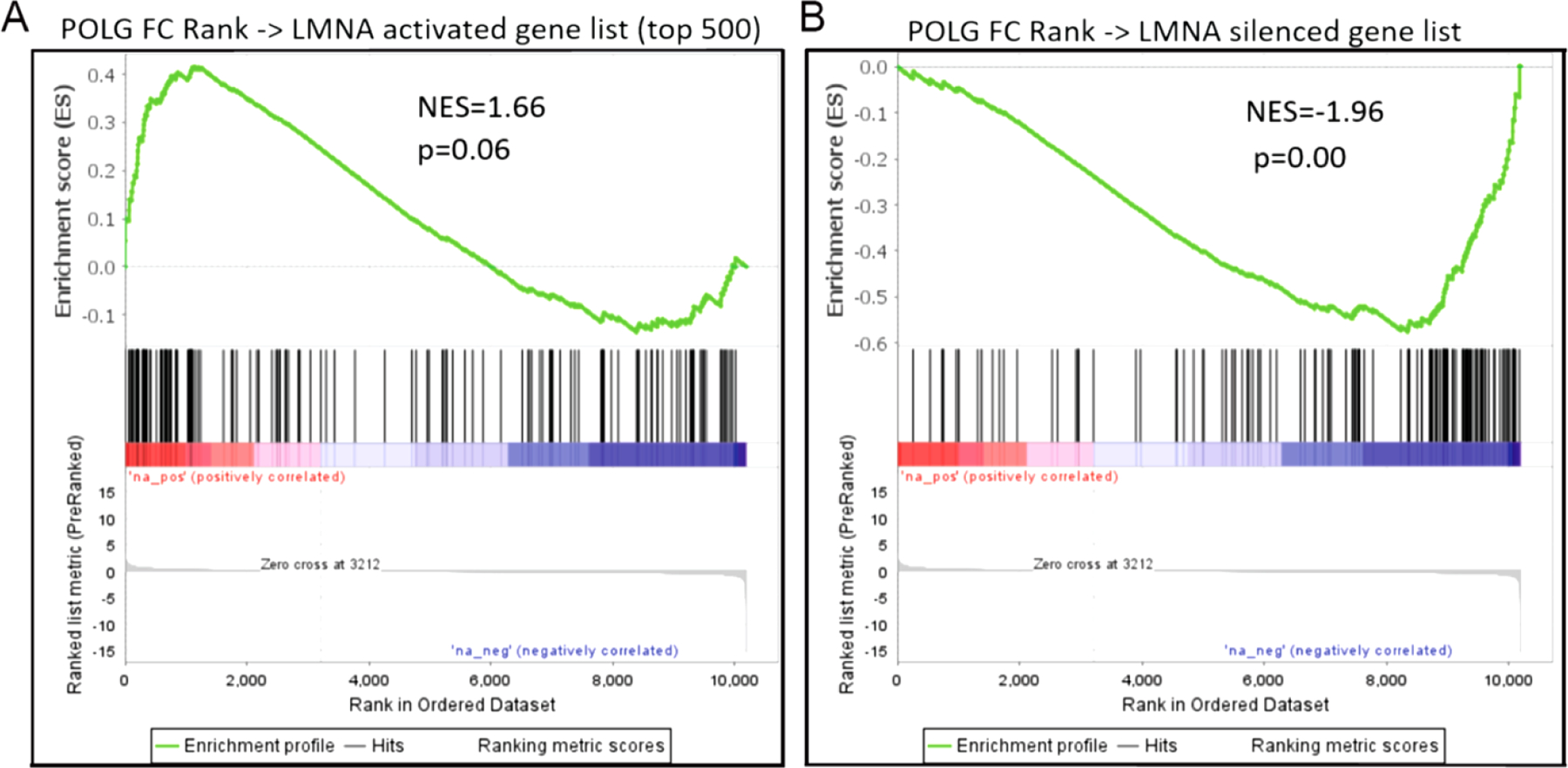

GSEA was also used to determine how closely related the effect of POLG mutation was to accelerated cardiac aging caused in another genetic model (LMNA disruption). Similar to above, a ranked list of genes based on log(2) fold change in the current POLG RNA-seq data (>10,000 genes) was created and tested against gene sets for either LMNA disruption activated genes or LMNA disruption inhibited genes (21). While there was suggestion of enrichment for the genes activated in the LMNA mutant and POLG mutant (Figure 8A, normalized enrichment score (NES) =1.66, p value = 0.065), the enrichment found in inhibited genes was striking (Figure 8B, NES = −1.96, p value = 0.00).

Figure 8. Conservation of gene expression changes in two genetic models of accelerated cardiac aging.

GSEA was used to compare the gene expression changes caused by POLG mutation to those caused by cardiomyocyte specific LMNA disruption. While there was suggestion of conservation between the genes activated by both LMNA and POLG mutation (A), the overlap in silenced genes from both models was robust (B).

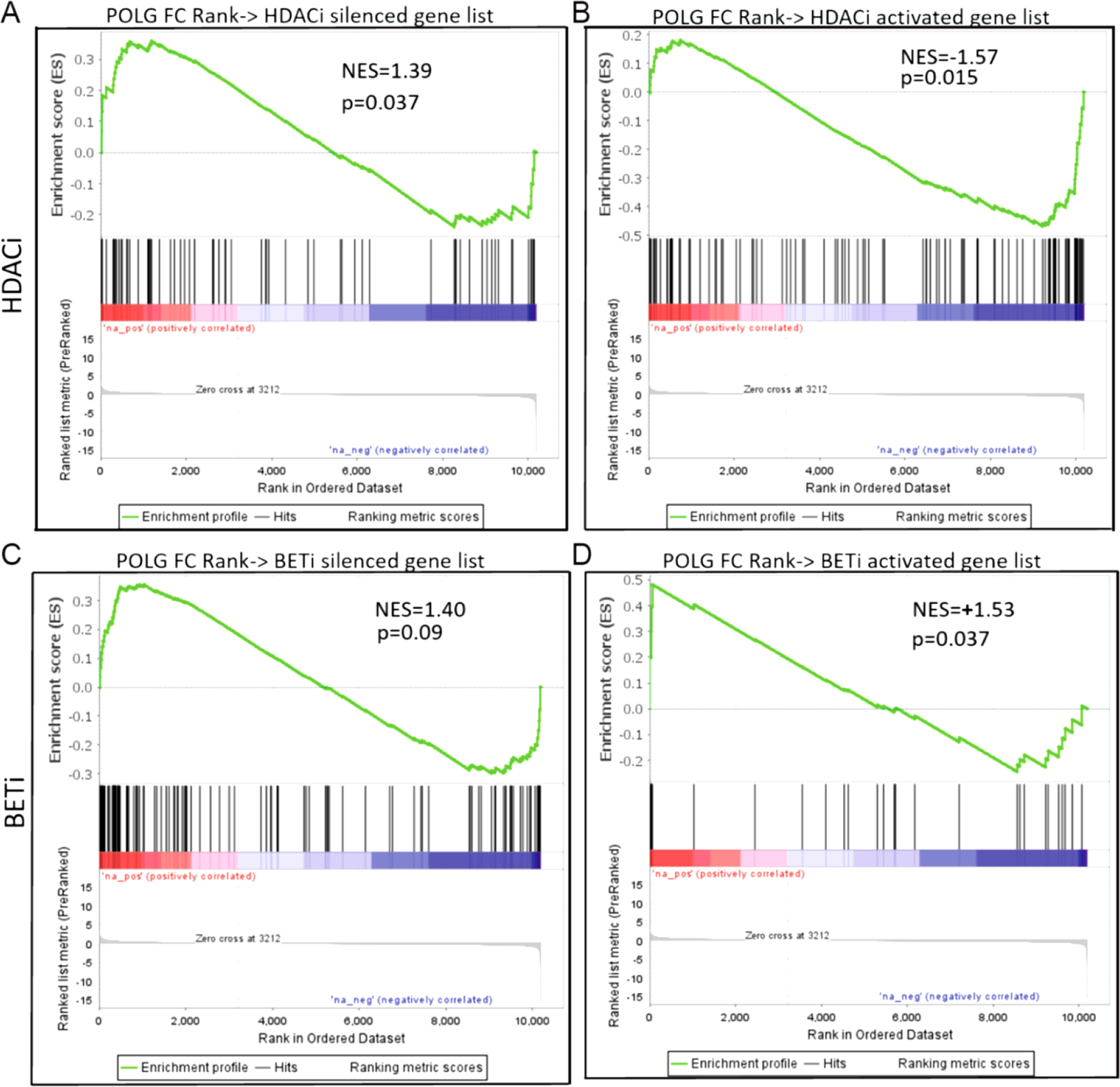

Given the significant overlap in gene expression between the accelerated aging models, we sought to determine if two promising epigenetic therapeutic approaches might impact significant portions of the POLG mutant gene expression signature (Figure 9). Gene sets for activated or inhibited genes were taken from cardiac HDAC inhibitor (HDACi, ITF2357/Givinostat) and cardiac BET protein inhibitor (BETi, JQ1) treated RNA-seq datasets (22 and 23 respectively). The same POLG log(2) FC ranked gene list as generated for Figures 7 and 8 was compared to these gene sets in GSEA. Both HDACi inhibited and activated genes were significantly enriched in the POLG dataset (HDACi inhibited : NES = 1.39, nominal p value = 0.037; HDACi activated : NES = −1.57, nominal p value = 0.015). The BETi dataset showed marginal enrichment in the POLG data for JQ1 inhibited genes (NES =1.40, nominal p value = 0.09) and also possitive enrichment for JQ1 activated genes (i.e. JQ1 activated genes that were also activated by POLG mutation, NES = 1.53, nominal p value = 0.037). This suggests that HDAC inhibitor treatments may provide more benefit in aging associated cardiac pathologies via their ability to rescue the expression of pathologically silenced genes.

Figure 9. GSEA comparison of POLG effected genes with HDACi or BETi regulated genes.

When POLG gene expression changes (fold change ranked gene list) were compared to the genes regulated by HDAC inhibitor treatment in cardiac tissue, significant enrichment was found with HDACi silenced (A) and activated genes (B). No enrichment was found with BET inhibitor silenced genes (C) and positive enrichment was observed for genes activated with BET protein inhibition (D).

Discussion

Metabolic dysfunction is a component of natural aging. Dysfunction generated during natural aging is typically far milder that what is seen in the POLG mutant (both metabolic and cardiac). We selected this model given the clear cardiac remodeling phenotype and the notion that metabolically driven mechanisms of remodeling associated with aging might be more apparent in this severe model as genome wide epigenetic and transcriptomic studies in natural aging models typically show underwhelming changes.

Several of our findings including in vivo survival, cardiac function, and cardiac morphology of POLG mutant mice are not entirely consistent with the interpretations of others who have used this model, which we attribute predominantly to environmental influences alluded to in the introduction (e.g. diet). Additional contributing factors potentially include lack of investigation in female POLG mice, lack of reporting of sex used, method of gravimetrics normalization (i.e. body weight vs tibia length), using echocardiographic calculations of LV mass instead of weights, isoflurane dose used during functional assessment and alternate use of ketamine as anesthetic during imaging. In our hands, mortality was earlier than others have reported and while our IACUC protocol did not support using natural death as an endpoint, euthanized animals were in severely deteriorated condition and unlikely to have survived more than a week past termination. In contrast, others have reported POLG D257A average lifespan at over 400 days (e.g. 12). In the referenced study, animals were fed a ~30% fat diet while our animals were fed chow containing only 5.8% fat, potentially suggesting that higher fat content is protective in this model. It is important not to discount the effects of environmental factors throughout the lifespan, including during developmental critical periods (24).

Interpretation of the cardiac functional measurements presented are potentially confounded by decreased heart rates observed in the POLG mutants. We attribute this to increased isoflurane sensitivity in the POLG mutants. Future investigation in this model may require cardiac pacing or alternate anesthetic. However, normalization of dp/dt max/min values to heart rate and EeS measurements (less dependent on heart rate) during invasive hemodynamic, as well as elevated liver weights/hepatic congestion support the interpretation of LV and RV dysfunction which is in line with other POLG cardiac literature (e.g. 11). Mitochondrial mutation and dysfunction is strongly linked with cardiac dysfunction in the clinic, including for the RV (e.g. 25).

Importantly, transcriptome profiling of the POLG RV provides a unique dataset for hypothesis generation regarding gene expression regulation downstream of severe metabolic dysfunction. IPA analysis of differentially expressed genes indicated clear inflammatory gene expression patterns in the POLG mutants as well as significant impacts on fibrosis and cardiomyopathy associated pathways. Investigation of molecules predicted to be critical up stream regulators strongly support pro-inflammatory signaling activation in the POLG RV. For instance, lipopolysaccharide, AGT (angiotensinogen), INFG were all predicted to be activated and clearly stimulate inflammation (e.g., 26–28). Similarly, Zc3h12c, the top predicted inhibited upstream regulator, has been implicated as an inhibitor of NF-kB (29).

Full utility of this RNA-Seq dataset is currently limited by the relative lack of available complementary RV datasets, particularly in accelerated aging models. With this limitation, we opted to compare gene expression changes in the POLG RV with currently available proteomic and transcriptomic data generated from LV or whole heart tissue in models and treatments of interest.

Comparison of gene expression changes in the POLG mutant with protein abundance changes allowed us to identify proteins most likely to be regulated by post-transcriptional mechanisms. Importantly, we identified a number of proteins critical for mitochondrial protein translation that are likely post-transcriptionally activated as these proteins were more abundant in the POLG mutant but their transcript expression was decreased. In contrast, many mitochondrial proteins necessary for metabolic function (e.g. ETC, TCA cycle) were less abundant in the POLG mutant (irrespective of transcript change). We believe this is a compensatory mechanism in the face of severe metabolic dysfunction where the mitochondria elevates expression of proteins associated with mitochondrial protein expression and complex assembly while decreasing expression of the actual subunits the translation and assembly machinery build into functional enzyme complexes. This pattern is strikingly similar to the mitochondrial unfolded protein response (UPRmt) where mitochondrial translation- and protein folding- loads are reduced (reviewed in 30), though GSEA, IPA, and ConsensusPathDB analyses failed to associate the POLG signature with UPRmt. It is likely that this UPRmt-like pattern is alternatively activated in the POLG RV as a previous report indicated the main transcriptional activator of UPRmt, CHOP/Ddit3, was not elevated in the POLG heart (14) and it is not increased in our data.

Our RNA-seq dataset also allowed comparison of two models of accelerated cardiac aging (POLG and LMNA mutation). Interestingly, while there was some overlap in the upregulated genes in both models, the overlap in downregulated genes in both models was profound. From a philosophical perspective, this potentially indicates cardiac aging is less about what genes are upregulated but rather, function lost due to the genes that have reduced expression. Along these lines, we observed that HDAC inhibition significantly upregulated the expression of genes whose expression was lost in the POLG mutant, reinforcing the notion of zinc-dependent HDAC inhibition as a potentially beneficial therapeutic strategy.

Given the severe phenotypes observed in POLG mutant mice, it is unclear how broadly these results are applicable to human age-related cardiac remodeling. However, the fact that this mutant mouse was engineered to model a pathological human mutation suggests these findings are at least somewhat relevant for individuals with mitochondria-involved genetic cardiomyopathies. Moreover, we expect that several of the identified mechanisms are applicable in less extreme aging-associated remodeling. For instance, inflammation and LPS activation are commonly reported activated pathways in many aging models, including natural aging. Also in our data, STAT1 activation was identified as a strong sub-node downstream of LPS. Recent reports indicate that age-dependent increases in STAT1 baseline activity (and therefore less responsive to stimulation), contributes to senescence and is associated with chronic inflammation and cardiovascular risk in human aging (31, 32).

This work highlights the degree to which alternate environmental exposures can modulate the presentation of pathology arising from the same genetic mutation. Observed sex differences reiterate the complexities of sex-dependent responses to metabolic insult (33–36), that can also be seen in response to inflammation (37). Importantly, we provide a unique dataset to the field, which will allow hypothesis generation for investigation of cardiac RV physiology and function. We also conclude that the POLG mutant may be a useful tool for in vivo study of non-canonical UPRmt, and demonstrate the importance of gene expression rescue in potential anti-aging therapeutics.

Methods

Animals:

PolG D257A mutant mice were acquired from the Jackson Laboratory (B6.129S7(Cg)-Polgtm1Prol/J, deposited by Dr. Tomas A Prolla) and housed in the Davis Heart and Lung Research Institute vivarium. Wild type (WT) and homozygous POLG D257A mutants (POLG) were generated by heterozygous breeding. Animals were maintained on a 12:12 light:dark schedule and had free access to water and food (Teklad 7012). All animal care and experimental procedures were in accordance with the Ohio State University IACUC and NIH ethical use of animal guidelines.

Echocardiography:

Cardiac function assessment (echo and PV Loop/hemodynamics) was conducted as in Tanwar et al., 2017 (38). Echocardiography was performed utilizing the Vevo 3100 (Visual Sonics) ultrasound with a 40 MHz transducer. Under light anesthesia (1–2% isoflurane in O2), mice were placed in supine position and imaged to acquire LV and RV function. LV chamber dimensions (end-diastolic dimension at diastole [LVEDd], posterior wall at diastole [LVPWd]), fractional shortening (FS) and ejection fraction (EF) were obtained utilizing m-mode in the peristernal short-axis view of the heart at the level of the papillary muscles.

Hemodynamics:

Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and intubated via a tracheotomy. They were then transferred to a ventilator (VentElite, Harvard Apparatus) at 135 µL/min/g body and kept at 37°C via a heating pad. PV loops were then performed to evaluate cardiac function with a 1 Fr PVR-1030 small mammal catheter (Millar) and analyzed through LabChart8 Pro (AD Instruments). An IV consisting of 10% Bovine Albumin Serum (BSA) in 0.9% saline was used to maintain fluids throughout the surgery. In some measurements (ESPVR [Ees]) the inferior vena cava was occluded with a suture string to alter pre-load. RV pressure was obtained after measurements were taken from the LV. LV chamber dimensions obtained by echocardiography were used to calibrate LV hemodynamic measurements.

Terminal Harvest:

Under a deep plane of isoflurane anesthesia, the heart was removed and flushed with heparinized saline. Weights were obtained for whole heart, LV, RV, as well as liver (entire) and lungs (entire left and right). Weights were normalized to tibia length. For hearts intended for LV and RV histology, LV/RV dissection was not conducted, otherwise the RV was removed and snap frozen while the LV apex was removed and snap frozen with the LV remainder (mid through base) being formalin fixed for histological analysis.

RNA-Seq:

Sequencing and differential expression analysis conducted by LC Sciences (Houston, TX). Poly(A) RNA sequencing library was prepared from DNAse treated RNA from flash frozen RV tissue (female WT (4) and POLG (4) at 9–10 months of age) following Illumina’s TruSeq-stranded-mRNA sample preparation protocol. RNA integrity was checked with Agilent Technologies 2100 Bioanalyzer. Poly(A) tail-containing mRNAs were purified using oligo-(dT) magnetic beads with two rounds of purification. After purification, poly(A) RNA was fragmented in divalent cation buffer at elevated temperature. Quality control analysis and quantification of the sequencing library were performed using Agilent Technologies 2100 Bioanalyzer High Sensitivity DNA Chip. Paired-ended sequencing was performed on Illumina’s NovaSeq 6000 sequencing system.

RNA-seq Analysis:

Cutadapt (39) and Perl were used to remove adaptor contamination, low quality and undetermined bases. Then sequence quality was verified using FastQC (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/). HISAT2 (40) was used to map reads to the MM10 genome. The mapped reads of each sample were assembled using StringTie (41). Then, all transcriptomes were merged to reconstruct a comprehensive transcriptome using perl and gffcompare. After the final transcriptome was generated, StringTie and edgeR (42) was used to estimate the expression levels of all transcripts. StringTie was used to perform expression leveling for mRNAs by calculating FPKM. Differentially expressed mRNAs were identified by R package edgeR.

IPA Analysis:

Differentially expressed genes were loaded into IPA (Qiagen) and a core analysis was run for genes with adjusted p<0.05 and absolute log2FC>0.5. The top effected canonical pathways and predicted activated and inhibited upstream regulators are reported. Depiction of genes leading to the prediction of LPS activation was generated using the pathway grow and build tool in IPA (intermediate nodes in the pathway that did not show expression or differential expression in the dataset were removed manually).

GSEA:

To compare the POLG mutation gene expression effect to other datasets, a log2FC ranked list of genes from the POLG dataset was compared to gene lists of significantly altered genes/proteins from the datasets indicated in the text using GSEA’s “GSEAPreranked” function (GSEA version 4.2.1, 43, 44). For Figure 7, proteins found to be clearly correlated with transcriptional regulation or post-transcriptional regulation were analyzed in ConsensusPath DB (45, 46).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Prasanjit Sahoo for technical assistance. MSS was supported by NIH AG056848, AHA 857280 and DHLRI institutional funds.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Data Availability

RNA-seq datasets will be deposited to the NCBI GEO database.

References

- 1.Franceschi C, Garagnani P, Morsiani C, Conte M, Santoro A, Grignolio A, Monti D, Capri M, Salvioli S. The Continuum of Aging and Age-Related Diseases: Common Mechanisms but Different Rates. Front Med (Lausanne) 2018. Mar 12;5:61. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2018.00061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lakatta EG. So! What’s aging? Is cardiovascular aging a disease? J Mol Cell Cardiol 2015. Jun;83:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dai DF, Rabinovitch PS. Cardiac aging in mice and humans: the role of mitochondrial oxidative stress. Trends Cardiovasc Med 2009. Oct;19(7):213–20. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu NN, Zhang Y, Ren J. Mitophagy, Mitochondrial Dynamics, and Homeostasis in Cardiovascular Aging. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2019. Nov 4;2019:9825061. doi: 10.1155/2019/9825061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rahman S, Copeland WC. POLG-related disorders and their neurological manifestations. Nat Rev Neurol 2019. Jan;15(1):40–52. doi: 10.1038/s41582-018-0101-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewis W, Day BJ, Kohler JJ, Hosseini SH, Chan SS, Green EC, Haase CP, Keebaugh ES, Long R, Ludaway T, Russ R, Steltzer J, Tioleco N, Santoianni R, Copeland WC. Decreased mtDNA, oxidative stress, cardiomyopathy, and death from transgenic cardiac targeted human mutant polymerase gamma. Lab Invest 2007. Apr;87(4):326–35. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koczor CA, Torres RA, Fields E, Qin Q, Park J, Ludaway T, Russ R, Lewis W. Transgenic mouse model with deficient mitochondrial polymerase exhibits reduced state IV respiration and enhanced cardiac fibrosis. Lab Invest 2013. Feb;93(2):151–8. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2012.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trifunovic A, Wredenberg A, Falkenberg M, Spelbrink JN, Rovio AT, Bruder CE, Bohlooly-Y M, Gidlöf S, Oldfors A, Wibom R, Törnell J, Jacobs HT, Larsson NG. Premature ageing in mice expressing defective mitochondrial DNA polymerase. Nature 2004. May 27;429(6990):417–23. doi: 10.1038/nature02517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang D, Mott JL, Farrar P, Ryerse JS, Chang SW, Stevens M, Denniger G, Zassenhaus HP. Mitochondrial DNA mutations activate the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway and cause dilated cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Res 2003. Jan;57(1):147–57. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00695-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams SL, Huang J, Edwards YJ, Ulloa RH, Dillon LM, Prolla TA, Vance JM, Moraes CT, Züchner S. The mtDNA mutation spectrum of the progeroid Polg mutator mouse includes abundant control region multimers. Cell Metab 2010. Dec 1;12(6):675–82. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dai DF, Chen T, Wanagat J, Laflamme M, Marcinek DJ, Emond MJ, Ngo CP, Prolla TA, Rabinovitch PS. Age-dependent cardiomyopathy in mitochondrial mutator mice is attenuated by overexpression of catalase targeted to mitochondria. Aging Cell 2010. Aug;9(4):536–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00581.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Someya S, Kujoth GC, Kim MJ, Hacker TA, Vermulst M, Weindruch R, Prolla TA. Effects of calorie restriction on the lifespan and healthspan of POLG mitochondrial mutator mice. PLoS One 2017. Feb 3;12(2):e0171159. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Golob MJ, Tian L, Wang Z, Zimmerman TA, Caneba CA, Hacker TA, Song G, Chesler NC. Mitochondria DNA mutations cause sex-dependent development of hypertension and alterations in cardiovascular function. J Biomech 2015. Feb 5;48(3):405–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2014.12.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woodall BP, Orogo AM, Najor RH, Cortez MQ, Moreno ER, Wang H, Divakaruni AS, Murphy AN, Gustafsson ÅB. Parkin does not prevent accelerated cardiac aging in mitochondrial DNA mutator mice. JCI Insight 2019. Apr 16;5(10):e127713. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.127713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Urashima T, Zhao M, Wagner R, Fajardo G, Farahani S, Quertermous T, Bernstein D. Molecular and physiological characterization of RV remodeling in a murine model of pulmonary stenosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2008; 295:H1351–H1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simon MA. Assessment and treatment of right ventricular failure. Nat Rev Cardiol 2013; 10:204–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ikeda S, Satoh K, Kikuchi N, Miyata S, Suzuki K, Omura J, Shimizu T, Kobayashi K, Kobayashi K, Fukumoto Y, Sakata Y, Shimokawa H. Crucial role of rho-kinase in pressure overload-induced right ventricular hypertrophy and dysfunction in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2014. Jun;34(6):1260–71. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.303320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McLaughlin KL, Kew KA, McClung JM, Fisher-Wellman KH. Subcellular proteomics combined with bioenergetic phenotyping reveals protein biomarkers of respiratory insufficiency in the setting of proofreading-deficient mitochondrial polymerase. Sci Rep 2020. Feb 27;10(1):3603. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-60536-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chung I, Choudhury A, Lip GY. Platelet activation in acute, decompensated congestive heart failure. Thromb Res 2007;120(5):709–13. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Estevez B, Du X. New Concepts and Mechanisms of Platelet Activation Signaling. Physiology (Bethesda) 2017. Mar;32(2):162–177. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00020.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Auguste G, Rouhi L, Matkovich SJ, Coarfa C, Robertson MJ, Czernuszewicz G, Gurha P, Marian AJ. BET bromodomain inhibition attenuates cardiac phenotype in myocyte-specific lamin A/C-deficient mice. J Clin Invest 2020. Sep 1;130(9):4740–4758. doi: 10.1172/JCI135922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Travers JG, Wennersten SA, Peña B, Bagchi RA, Smith HE, Hirsch RA, Vanderlinden LA, Lin YH, Dobrinskikh E, Demos-Davies KM, Cavasin MA, Mestroni L, Steinkühler C, Lin CY, Houser SR, Woulfe KC, Lam MPY, McKinsey TA. HDAC Inhibition Reverses Preexisting Diastolic Dysfunction and Blocks Covert Extracellular Matrix Remodeling. Circulation 2021. May 11;143(19):1874–1890. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.046462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duan Q, McMahon S, Anand P, Shah H, Thomas S, Salunga HT, Huang Y, Zhang R, Sahadevan A, Lemieux ME, Brown JD, Srivastava D, Bradner JE, McKinsey TA, Haldar SM. BET bromodomain inhibition suppresses innate inflammatory and profibrotic transcriptional networks in heart failure. Sci Transl Med 2017. May 17;9(390):eaah5084. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aah5084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Velten M, Gorr MW, Youtz DJ, Velten C, Rogers LK, Wold LE. Adverse perinatal environment contributes to altered cardiac development and function. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2014. May;306(9):H1334–40. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00056.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karamanlidis G, Bautista-Hernandez V, Fynn-Thompson F, Del Nido P, Tian R. Impaired mitochondrial biogenesis precedes heart failure in right ventricular hypertrophy in congenital heart disease. Circ Heart Fail 2011. Nov;4(6):707–13. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.961474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Drosatos K, Drosatos-Tampakaki Z, Khan R, Homma S, Schulze PC, Zannis VI, Goldberg IJ. Inhibition of c-Jun-N-terminal kinase increases cardiac peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha expression and fatty acid oxidation and prevents lipopolysaccharide-induced heart dysfunction. J Biol Chem 2011. Oct 21;286(42):36331–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.272146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rong J, Tao X, Lin Y, Zheng H, Ning L, Lu HS, Daugherty A, Shi P, Mullick AE, Chen S, Zhang Z, Xu Y, Wang J. Loss of Hepatic Angiotensinogen Attenuates Sepsis-Induced Myocardial Dysfunction. Circ Res 2021. Aug 20;129(5):547–564. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.318075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCarthy MK, Procario MC, Twisselmann N, Wilkinson JE, Archambeau AJ, Michele DE, Day SM, Weinberg JB. Proinflammatory effects of interferon gamma in mouse adenovirus 1 myocarditis. J Virol 2015. Jan;89(1):468–79. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02077-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu L, Zhou Z, Huang S, Guo Y, Fan Y, Zhang J, Zhang J, Fu M, Chen YE. Zc3h12c inhibits vascular inflammation by repressing NF-κB activation and pro-inflammatory gene expression in endothelial cells. Biochem J 2013. Apr 1;451(1):55–60. doi: 10.1042/BJ20130019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Münch C The different axes of the mammalian mitochondrial unfolded protein response. BMC Biol 2018. Jul 26;16(1):81. doi: 10.1186/s12915-018-0548-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sayed N, Huang Y, Nguyen K, Krejciova-Rajaniemi Z, Grawe AP, Gao T, Tibshirani R, Hastie T, Alpert A, Cui L, Kuznetsova T, Rosenberg-Hasson Y, Ostan R, Monti D, Lehallier B, Shen-Orr SS, Maecker HT, Dekker CL, Wyss-Coray T, Franceschi C, Jojic V, Haddad F, Montoya JG, Wu JC, Davis MM, Furman D. An inflammatory aging clock (iAge) based on deep learning tracks multimorbidity, immunosenescence, frailty and cardiovascular aging. Nat Aging 2021. Jul;1:598–615. doi: 10.1038/s43587-021-00082-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shen-Orr SS, Furman D, Kidd BA, Hadad F, Lovelace P, Huang YW, Rosenberg-Hasson Y, Mackey S, Grisar FA, Pickman Y, Maecker HT, Chien YH, Dekker CL, Wu JC, Butte AJ, Davis MM. Defective Signaling in the JAK-STAT Pathway Tracks with Chronic Inflammation and Cardiovascular Risk in Aging Humans. Cell Syst 2016. Oct 26;3(4):374–384.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2016.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walker CJ, Schroeder ME, Aguado BA, Anseth KS, Leinwand LA. Matters of the heart: Cellular sex differences. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2021. Nov;160:42–55. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2021.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fourny N, Beauloye C, Bernard M, Horman S, Desrois M, Bertrand L. Sex Differences of the Diabetic Heart. Front Physiol 2021. May 27;12:661297. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2021.661297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murphy E, Amanakis G, Fillmore N, Parks RJ, Sun J. Sex Differences in Metabolic Cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Res 2017. Mar 15;113(4):370–377. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvx008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Velten M, Heyob KM, Wold LE, Rogers LK. Perinatal inflammation induces sex-related differences in cardiovascular morbidities in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2018. Mar 1;314(3):H573–H579. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00484.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beale AL, Meyer P, Marwick TH, Lam CSP, Kaye DM. Sex Differences in Cardiovascular Pathophysiology: Why Women Are Overrepresented in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. Circulation 2018. Jul 10;138(2):198–205. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.034271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tanwar V, Gorr MW, Velten M, Eichenseer CM, Long VP 3rd, Bonilla IM, Shettigar V, Ziolo MT, Davis JP, Baine SH, Carnes CA, Wold LE. In Utero Particulate Matter Exposure Produces Heart Failure, Electrical Remodeling, and Epigenetic Changes at Adulthood. J Am Heart Assoc 2017. Apr 11;6(4):e005796. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.005796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martin Marcel. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet.journal, [S.l.], v. 17, n. 1, p. pp. 10–12, may 2011. ISSN 2226–6089. Available at: http://journal.embnet.org/index.php/embnetjournal/article/view/200 doi:https://doi.org/10.14806/ej.17.1.200. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim D, Paggi JM, Park C, et al. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat Biotechnol 37, 907–915 (2019). 10.1038/s41587-019-0201-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pertea M, Pertea G, Antonescu C, et al. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat Biotechnol 33, 290–295 (2015). 10.1038/nbt.3122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK (2010). “edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data.” Bioinformatics, 26(1), 139–140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, Mesirov JP. Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Oct 2005, 102 (43) 15545–15550; DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mootha V, Lindgren C, Eriksson KF, et al. PGC-1α-responsive genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation are coordinately downregulated in human diabetes. Nat Genet 34, 267–273 (2003). 10.1038/ng1180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kamburov A, Pentchev K, Galicka H, Wierling C, Lehrach H, Herwig R. ConsensusPathDB: toward a more complete picture of cell biology. Nucleic Acids Research 2011. 39(Database issue):D712–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kamburov A, Wierling C, Lehrach H, Herwig R. ConsensusPathDB--a database for integrating human functional interaction networks. Nucleic Acids Research 2009. 37(Database issue):D623–D628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

RNA-seq datasets will be deposited to the NCBI GEO database.