Abstract

Washed-cell suspensions of Sulfurospirillum barnesii reduced selenate [Se(VI)] when cells were cultured with nitrate, thiosulfate, arsenate, or fumarate as the electron acceptor. When the concentration of the electron donor was limiting, Se(VI) reduction in whole cells was approximately fourfold greater in Se(VI)-grown cells than was observed in nitrate-grown cells; correspondingly, nitrate reduction was ∼11-fold higher in nitrate-grown cells than in Se(VI)-grown cells. However, a simultaneous reduction of nitrate and Se(VI) was observed in both cases. At nonlimiting electron donor concentrations, nitrate-grown cells suspended with equimolar nitrate and selenate achieved a complete reductive removal of nitrogen and selenium oxyanions, with the bulk of nitrate reduction preceding that of selenate reduction. Chloramphenicol did not inhibit these reductions. The Se(VI)-respiring haloalkaliphile Bacillus arsenicoselenatis gave similar results, but its Se(VI) reductase was not constitutive in nitrate-grown cells. No reduction of Se(VI) was noted for Bacillus selenitireducens, which respires selenite. The results of kinetic experiments with cell membrane preparations of S. barnesii suggest the presence of constitutive selenate and nitrate reduction, as well as an inducible, high-affinity nitrate reductase in nitrate-grown cells which also has a low affinity for selenate. The simultaneous reduction of micromolar Se(VI) in the presence of millimolar nitrate indicates that these organisms may have a functional use in bioremediating nitrate-rich, seleniferous agricultural wastewaters. Results with 75Se-selenate tracer show that these organisms can lower ambient Se(VI) concentrations to levels in compliance with new regulations proposed for release of selenium oxyanions into the environment.

Wastewater derived from the drainage of irrigated agricultural fields of the western San Joaquin Valley of California contains high concentrations of the toxic trace element selenate (∼3.5 μM) as well as nitrate (∼3.5 mM) (20, 29). Evaporative concentration of these waters in this semiarid region forms brines which are still rich in oxyanions of selenium (30 to 40 μM) and nitrogen (∼0.7 mM) (14, 15). Assays of in situ denitrification and dissimilatory selenate reduction in the sediments underlying these brines show that both these respiratory processes have their highest activity within the top (0- to 2-cm subsection) of the sediment column, where they are spatially segregated from sulfate reduction (15). This suggests that bacterial respiration of selenate and nitrate occurs simultaneously at these ambient concentrations, which appears to contradict results with sediment slurries (14), enrichment cultures (21), and cell suspensions of Sulfurospirillum barnesii SES3 (12, 24), all of which indicate preferential usage of nitrate over selenate. Similarly, during growth of Thauera selenatis, use of nitrate as an electron acceptor precedes that of selenate (3). Nonetheless, T. selenatis has been employed successfully in pilot studies to remove selenium oxyanions (by reduction to elemental selenium) in nitrate-rich drainage waters (2, 9). Removal of these toxic oxyanions by their reduction to the much less harmful and physically immobile elemental state forms the practical basis for the design of such anaerobic treatment systems.

It has been hypothesized elsewhere that selenate-respiring bacteria may have a broad-specificity, molybdenum-containing enzyme capable of reduction of either nitrate or selenate in addition to other substrates (10, 12). However, experiments with cell suspensions and mutant strains of T. selenatis indicate the presence of distinct nitrate and selenate reductases (17), and the purified selenate reductase of T. selenatis shows substrate specificity only for selenate and will not couple with nitrate (19). The selenate reductase of T. selenatis is soluble and located in the periplasm, while that of S. barnesii is insoluble and membrane bound, a fact which has impeded the latter’s purification and characterization (22a). Nonetheless, membrane fractions from S. barnesii exhibit difference spectra which indicate that only a b-type cytochrome is associated with selenate reduction while a c-type cytochrome is involved in nitrate reduction, thereby suggesting the presence of two distinct respiratory pathways (25).

Despite these obvious differences, S. barnesii membranes from selenate-grown and nitrate-grown cells also have a diminished but discernible capacity to couple methyl viologen oxidation to the reduction of other substrates (e.g., membranes from nitrate-grown cells will oxidize methyl viologen with selenate at 40% the rate exhibited with nitrate [25]). One interpretation of these results is that S. barnesii expresses low levels of a constitutive selenate reductase when the organism is grown on nitrate. Such a condition would allow for it to reduce micromolar levels of selenate in the presence of millimolar nitrate and hence make it a suitable candidate for the bioremediation of nitrate-rich, seleniferous wastewaters as has been shown elsewhere for T. selenatis (3, 9). We now report on the potential of S. barnesii as well as the recently isolated haloalkaliphiles Bacillus arsenicoselenatis and Bacillus selenitireducens (26) to serve as bioremediative agents for the removal of selenium oxyanions from nitrate-rich waters.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experiments with washed-cell suspensions.

S. barnesii SES3 was grown in an anaerobic lactate-basal salts medium supplemented with vitamins and yeast extract (1.0 g/liter) with 10 mM selenate [Se(VI)], nitrate, arsenate, thiosulfate, or fumarate as the electron acceptor (8, 12). All manipulations were made in an anaerobic glove box, and strict anaerobic techniques were employed throughout the experiments. Cells were harvested from late log phase by centrifugation and washed twice in anaerobic buffer solution (12). Cells were resuspended in either phosphate or bicarbonate buffer with lactate (2.0 mM) plus 1.0 mM Se(VI) and incubated in 60-ml anaerobic (N2 atmosphere) serum bottles (25- to 30-ml cell suspension) with gyratory shaking (100 rpm) at 30°C, during which time samples were periodically withdrawn by syringe from the liquid phase. In some experiments, nitrate-grown cells were resuspended with nitrate (5.4 mM) plus Se(VI) (0.7 mM) with only a limiting quantity of lactate provided (5 mM). In another experiment, nitrate-grown cells were resuspended with equimolar levels of nitrate plus Se(VI) (1 mM each) at nonlimiting levels of lactate (5 mM). This experiment was repeated with or without the addition of chloramphenicol (20 μg/ml) to inhibit de novo protein synthesis. The haloalkaliphiles B. arsenicoselenatis and B. selenitireducens were grown in an alkaline (pH 9.8), saline (salinity = 40 g/liter) basal salts medium supplemented with vitamins and 0.2 g of yeast extract per liter (26). Lactate (20 mM) was the electron donor with nitrate (20 mM) or nitrate plus Se(VI) (5 mM each) as electron acceptors. Cells were harvested, washed, and incubated as described above, with an alkaline (pH 9.8) phosphate wash solution as given in the work of Switzer Blum et al. (26), differing by use of 40 g of NaCl per liter and omission of Na2CO3 and NH4Cl. Cells were resuspended in this medium with lactate (10 to 15 mM) and nitrate plus Se(VI) (1.0 mM each) and incubated in shaking serum bottles as given above in the experiments for S. barnesii.

Inhibition experiments.

Cell suspensions of S. barnesii grown on nitrate or Se(VI) were prepared as described above and placed in serum bottles. Incubations (3 h) were run with 2.5 mM lactate as the electron donor. These investigations measured inhibition of reduction of 100 μM Se(VI) and of 100 μM nitrate by Se(VI)-grown and by nitrate-grown cells. Cells were incubated with 0, 0.01, 0.1, and 1.0 mM nitrate or selenate.

Kinetic experiments with cell membranes.

Membrane fractions of nitrate-grown S. barnesii were prepared and assayed by measuring the oxidation of methyl viologen as reported previously (25). Michaelis-Menten kinetic experiments were conducted by using nitrate, nitrite, and Se(VI) as the electron acceptors. The values for Km and Vmax were calculated by double-reciprocal plots with Prism software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, Calif.).

Experiments with 75Se-selenate.

75Se(VI) (sodium salt) was employed as a tracer to monitor dissimilatory Se(IV) reduction by cell suspensions at Se oxyanion detection limits below those of the high-performance liquid chromatograph. Cell suspensions (20 ml) were generated as given above and were incubated with lactate (10 to 15 mM) and nitrate (5 mM) with a starting unlabeled selenate concentration of ∼50 μM plus 1.3 μCi of carrier-free 75Se-selenate (Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, N. Mex.; purity = >99%; specific activity = 3.08 Ci/mmol). Samples were withdrawn over the course of the incubation and centrifuge filtered (to remove elemental 75Se), and the liquid phase which represented a mixture of 75Se(VI) and 75Se-selenite [Se(IV)] was either counted directly or injected into a high-performance liquid chromatograph for separation and fraction collection of the eluted volumes containing the two selenium oxyanions (5, 12).

Analyses.

Nitrate, nitrite, Se(VI), and Se(IV) were determined by ion chromatography (13). 75Se was quantified with a γ-spectrophotometer (14). Cell densities in the suspensions were determined by acridine orange direct counts (7). Protein was measured by the Bradford assay (1).

RESULTS

Incubation of cell suspension.

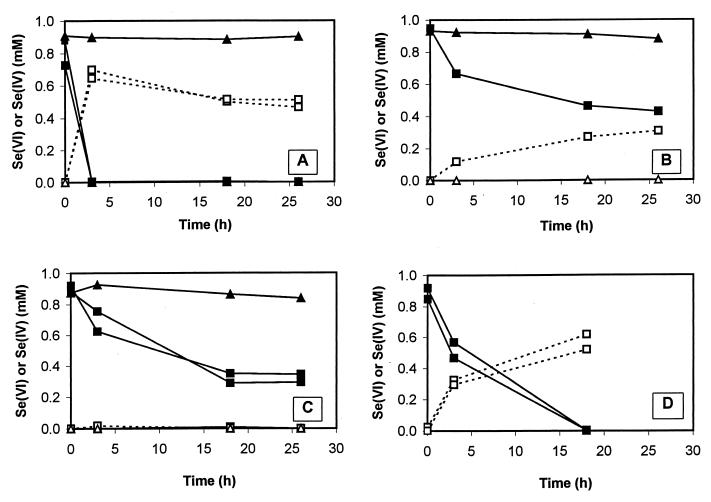

S. barnesii cells demonstrated obvious selenate reductase activity (indicated by the consumption of selenate) in cells grown on fumarate, arsenate, nitrate, and thiosulfate (Fig. 1). No activity was present in autoclaved controls (Fig. 1A, B, and C). When normalized to cell density, activity was highest in the fumarate-grown cells (Fig. 1A; ∼1.04 × 10−18 mol cell−1 min−1) and was lowest in the nitrate-grown cells (Fig. 1C; ∼0.13 × 10−18 mol cell−1 min−1). With the exception of nitrate-grown cells, there was a stoichiometric balance between selenate consumption and selenite accumulation. No selenite was present in nitrate-grown cells (Fig. 1C), presumably due to its further reduction to Se(O) by a respiratory nitrite reductase expressed during growth on nitrate (3) but not expressed with the other electron acceptors. Nitrate-grown S. barnesii cells were previously shown to rapidly reduce millimolar Se(IV) to Se(O) (15).

FIG. 1.

Reduction of Se(VI) by washed-cell suspensions of S. barnesii grown with fumarate (cell density = 1.6 × 109 cells/ml) (A), arsenate (cell density = 4.0 × 108 cells/ml) (B), nitrate (cell density = 4.3 × 109 cells/ml) (C), and thiosulfate (cell density = 2.0 × 108 cells/ml) (D) as electron acceptors. Symbols: squares, live samples; triangles, autoclaved controls; closed symbols, Se(VI); open symbols, Se(IV). Two sets of squares in panels A, C, and D are for replicate cell suspensions.

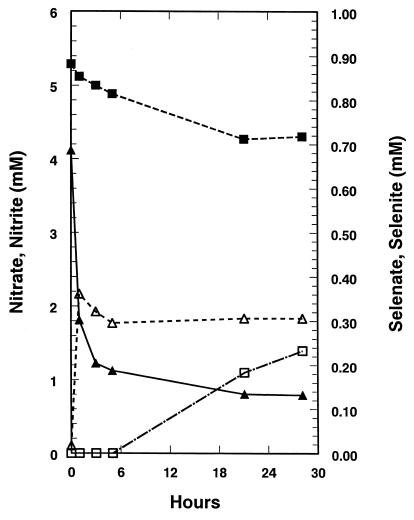

Selenate-grown suspensions of S. barnesii quickly reduced selenate to selenite in the presence of a limiting quantity of lactate (Fig. 2). The observed rate (∼5.2 × 10−18 mol cell−1 min−1) was higher than that achieved with fumarate-grown cells (Fig. 1A). The amount of Se(VI) consumed (∼0.58 mM) was not in balance with the selenite recovered (∼0.34 mM), probably due to the reduction of some of the selenite to Se(O). Reduction of nitrate to nitrite was evident, but it proceeded at a lower rate (approximately fourfold) than that for selenate reduction, and accumulation of nitrite lagged behind that of selenite. In the case of nitrate-grown cells resuspended with limiting lactate, both nitrate and selenate were reduced simultaneously (Fig. 3). When normalized to cell densities, nitrate reduction was ∼11-fold faster than that in selenate-grown cells, while selenate reduction was nearly fourfold slower. In this experiment, there was a rough balance between nitrate or selenate removed and the corresponding accumulation of nitrite of selenite.

FIG. 2.

Reduction of Se(VI) (▴) and nitrate (■) to Se(IV) (▵) and nitrite (□) by selenate-grown washed-cell suspensions of S. barnesii with 5 mM lactate as electron donor. Cell density = 8.0 × 108 cells/ml.

FIG. 3.

Reduction of Se(VI) (▴) and nitrate (■) to Se(IV) (▵) and nitrite (□) by washed-cell suspensions of nitrate-grown S. barnesii with 5 mM lactate as electron donor. Cell density = 1.3 × 109 cells/ml.

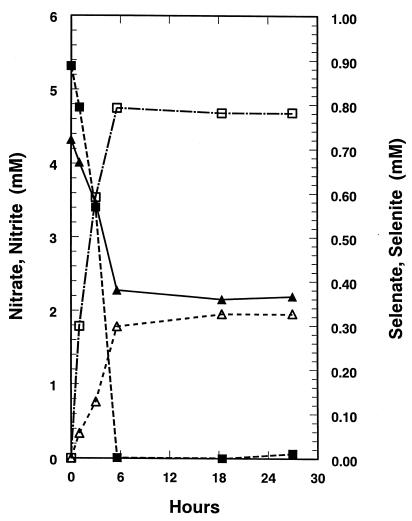

When nitrate-grown S. barnesii cells were suspended in the presence of equimolar (1 mM) nitrate and selenate at nonlimiting lactate concentrations (∼5 mM), nitrate reduction preceded that of selenate, followed by the interim accumulation and subsequent sequential reduction of nitrite and selenite (Fig. 4). In a follow-up experiment, these results were essentially reproduced, the only difference being that the cells were able to reduce all the oxyanions by 2 h of incubation instead of 7 h (data not shown). Chloramphenicol had no effect upon these reductions, and the results obtained with the experimental and control suspensions were identical, which suggests that the enzymes involved were constitutive (data not shown). When selenate-grown S. barnesii cells were incubated with equimolar nitrate plus selenate as given above, reduction of selenate and nitrate was rapid and virtually simultaneous (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Reduction of Se(VI) (▴) and nitrate (■) to Se(IV) (▵) and nitrite (□) by washed-cell suspensions of nitrate-grown S. barnesii incubated with 5 mM lactate as electron donor. Cell density = 5.1 × 109 cells/ml.

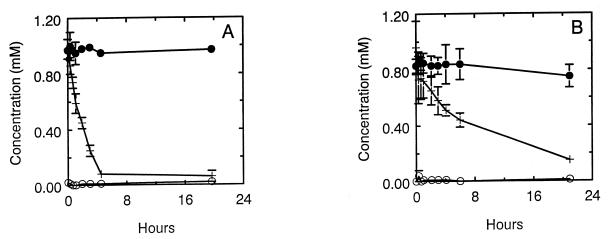

The results obtained with nitrate-grown B. arsenicoselenatis (Fig. 5A) and B. selenitireducens (Fig. 5B) stand in contrast to those obtained with S. barnesii. Although washed-cell suspensions of each of these haloalkaliphiles were able to reduce nitrate, neither culture exhibited any ability to reduce selenate. When we grew B. arsenicoselenatis in medium which contained both nitrate and selenate, washed cells were able to readily reduce selenate, but nitrate consumption lagged behind (data not shown). Thus, the starting concentrations of 0.67 mM nitrate and 0.92 mM selenate were lowered to 0.61 and 0.37 mM, respectively, after 4.5 h of incubation, and in addition, 0.34 mM selenite accumulated in the medium. In contrast, reduction of selenate did not occur for B. selenitireducens (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Reduction of Se(VI) and nitrate by cell suspensions of B. arsenicoselenatis (cell density = 2.8 × 108 cells/ml) (A) and B. selenitireducens (cell density = 1.8 × 109 cells/ml) (B) grown with nitrate as the electron acceptor. Symbols: ●, Se(VI); ○, Se(IV); +, nitrate. Results represent the means of three suspensions, and bars indicate ±1 standard deviation. Absence of bars indicates that errors were smaller than symbols.

Inhibition experiments with S. barnesii.

In experiments with nitrate- and Se(VI)-grown cells, no inhibition of nitrate reduction by 0.01 to 1.0 mM selenate was observed (Table 1). However, for selenate-grown cells, 0.1 and 1.0 mM nitrate did cause a significant partial inhibition (46 to 53%) of selenate reduction (Table 2). For nitrate-grown cells, 1.0 mM nitrate caused a 60% inhibition of selenate reduction, but no inhibition was noted at 0.1 mM nitrate.

TABLE 1.

Inhibition of nitrate reduction by selenate in washed-cell suspensions of nitrate- and selenate-grown S. barnesii with lactate as the electron donora

| Selenate (mM) | Nitrate reduced (nmol/ml)b

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Nitrate-grown cells | Selenate-grown cells | |

| 0.00 | 46.7 ± 6.0 | 42.2 ± 3.2 |

| 0.01 | 50.0 ± 4.6 | 40.5 ± 2.7 |

| 0.10 | 45.1 ± 2.2 | 43.0 ± 3.7 |

| 1.00 | 50.4 ± 3.3 | 50.7 ± 1.0 |

Lactate concentration was 2.5 mM, nitrate concentration was 100 μM, incubation time was 3 h, and cell density was 1.34 × 107 cells ml−1.

Mean ±1 standard deviation of three cell suspensions.

TABLE 2.

Inhibition of selenate reduction by nitrate in nitrate- and selenate-grown washed-cell suspensions of S. barnesii with lactate as the electron donora

| Nitrate (mM) | Se(VI) reduced (nmol/ml)b

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Nitrate-grown cells | Selenate-grown cells | |

| 0.00 | 55.8 ± 5.9 | 33.4 ± 3.2 |

| 0.01 | 55.0 ± 8.7 | 31.0 ± 1.0 |

| 0.10 | 61.3 ± 3.2 | 15.6 ± 1.4 |

| 1.00 | 22.3 ± 4.0 | 18.0 ± 1.3 |

Lactate concentration was 2.5 mM, selenate concentration was 100 μM, incubation time was 3 h, and cell density was 3.98 × 107 cells ml−1.

Mean ±1 standard deviation of three cell suspensions.

Kinetic experiments with S. barnesii membranes.

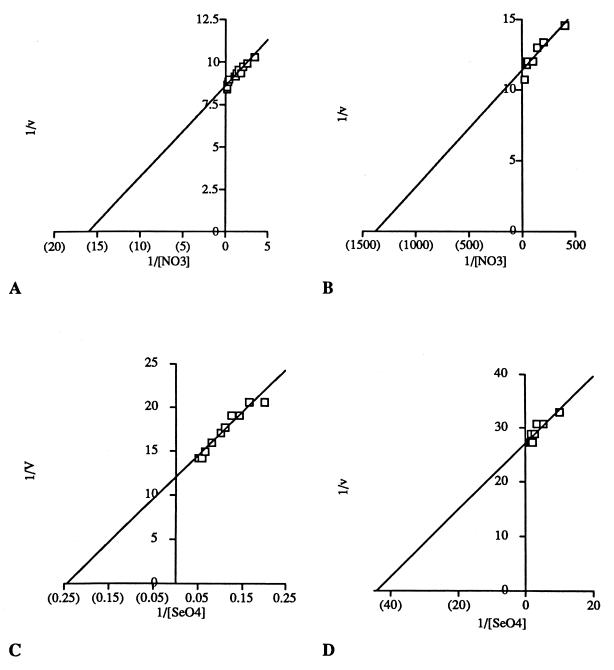

Membranes from nitrate-grown cells demonstrated biphasic saturation kinetics for selenate and nitrate (Fig. 6), although not for nitrite (data not shown). In contrast, no biphasic characteristics were displayed by selenate-grown cells (data not shown). The derived kinetic parameters for membranes from nitrate- and selenate-grown cells are given in Table 3. There were comparable high-affinity selenate reductases present in both membrane preparations, but a low-affinity selenate reductase (Km = 4 mM) was discernible only in the nitrate-grown membranes. Likewise, constitutive activity for nitrate reduction was evident in both selenate- and nitrate-grown cells (Km = 62.4 to 63.7 μM), but a very high affinity nitrate reductase (Km = 0.7 μM) was additionally displayed in nitrate-grown cells. A high-substrate-affinity nitrite reductase was present in membranes from both nitrate- and selenate-grown cells, although there was an affinity for nitrite greater by an order of magnitude in membranes from nitrate-grown cells. The high affinity can be attributed to the multiheme cytochrome c nitrite reductase expressed in nitrate-grown cells (25).

FIG. 6.

Double-reciprocal plots of biphasic methyl viologen oxidation kinetics achieved with membrane fractions of nitrate-grown S. barnesii with nitrate (A and B) or selenate (C and D) as the electron acceptor.

TABLE 3.

Kinetic parameters for membrane fractions of selenate- and nitrate-grown S. barnesii cells assayed with methyl viologen

| Condition | Km (μM) | Vmaxa | r2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| SeO4-grown cells | |||

| SeO4 | 13.1 | 28.2 | 0.97 |

| NO3 | 63.7 | 45.1 | 0.97 |

| NO2 | 2.3 | 68.5 | 0.98 |

| NO3-grown cells | |||

| SeO4 (high-affinity site) | 23.1 | 36.7 | 0.82 |

| SeO4 (low-affinity site) | 4,085 | 83.6 | 0.94 |

| NO3 (high-affinity site) | 0.70 | 87.2 | 0.86 |

| NO3 (low-affinity site) | 62.4 | 116.43 | 0.95 |

| NO2 | 0.36 | 39.6 | 0.95 |

Micromoles of methyl viologen oxidized per minute per milligram of protein.

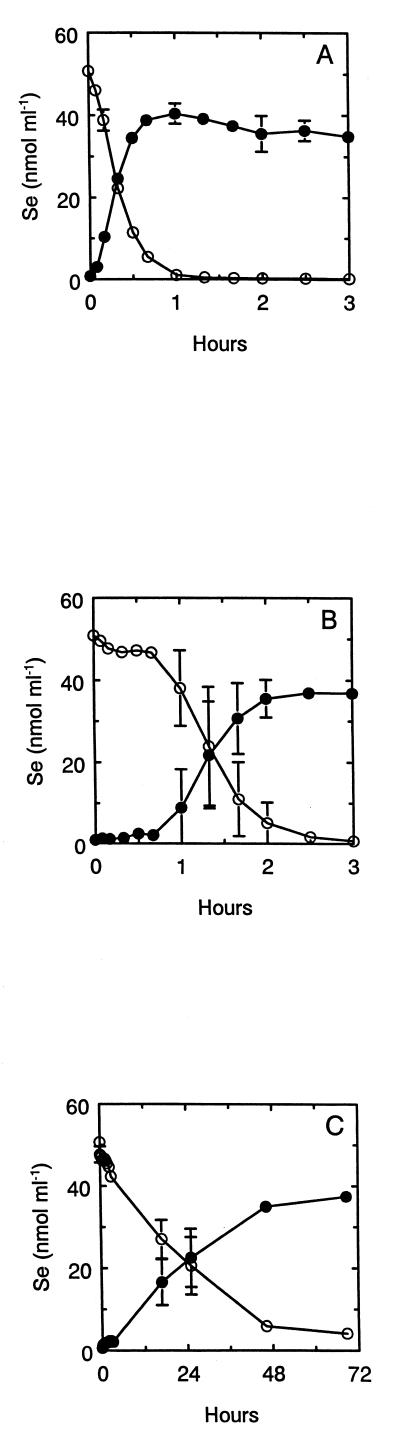

Radiotracer experiments with 75Se-selenate.

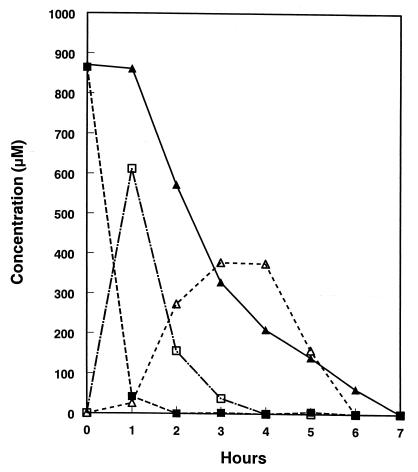

Cell suspensions of nitrate-grown S. barnesii rapidly reduced 50 μM selenate to Se(O) in the absence of nitrate (rate = ∼8.3 × 10−18 mol cell−1 min−1 [Fig. 7A]). There was a near equivalence between counts lost from solution and particulate counts retained on the filter, a situation similar to that for reduction of 75Se-selenite by this organism (12). After 80 min of incubation, essentially all (∼99%) of the selenate had been reduced to Se(O), and only traces of counts remained in solution, which were equivalent to <0.12 μM after 69 h of incubation (see below). There was no removal of counts from solution or accumulation of counts onto the filters in a sterile control or in a formalin-killed control (data not shown). The presence of 50 μM nitrate caused a 40-min lag before the reduction of 75Se-selenate was initiated (Fig. 7B), at which time reduction proceeded at a slightly lower rate (6.3 × 10−18 mol cell−1 min−1), and reduction was complete after 3 h. In contrast, cells incubated with 5 mM nitrate immediately reduced 75Se-selenate (Fig. 7C), but the reduction rate, although steady, was much lower than in the two other conditions (∼0.17 × 10−18 mol cell−1 min−1).

FIG. 7.

Reduction of 50 μM Se(VI) to Se(O) by cell suspensions of nitrate-grown S. barnesii as monitored by 75Se. (A) Suspension without nitrate; (B) Suspension with 50 μM nitrate added; (C) suspension with 5 mM nitrate added. Symbols: ○, Se(VI); ●, Se(O). Symbols indicate the averages of two cell suspensions, and bars indicate the ranges of values. Absence of bars indicates that errors were smaller than symbols. Cell density = 1.0 × 108 cells/ml.

We resolved the speciation of residual selenium oxyanions by high-performance liquid chromatography as collected 75Se-selenate and 75Se-selenite fractions. In the incubation without added nitrate (Fig. 7A), we detected 0.12 μM residual counts in solution after 69 h of incubation, of which dissolved selenate and selenite were 1 and 6 nM, respectively, which combined accounted for only 5.8% of the total residual counts (data not shown). For the incubation with 50 μM nitrate added (Fig. 7B), 0.14 μM residual counts in solution were detected at 69 h, of which selenate and selenite were 13 and 6 nM, respectively, which accounted for 13.6% of the residual counts. With 5 mM nitrate added to cells (Fig. 7C), 4.1 μM residual counts were detected in solution at 69 h, but selenate and selenite together accounted for only 0.11 μM, or 29.1%, of these residual counts. A similar result was obtained with B. arsenicoselenatis cells which were grown with both nitrate and selenate in the medium. Cells rapidly reduced the 50 μM selenate, removing 98.2% by 40 min, with residual counts equivalent to 0.9 μM remaining in solution (Table 4). Resolution of these counts revealed that there were 36 nM selenate and 14 nM selenite remaining in solution, which accounted for 5.5% of the total residual counts. There was no observed reduction of 75Se-selenate to 75Se(O) by B. selenitireducens (Table 4), an organism that respires selenite but not selenate (26).

TABLE 4.

Reduction of 50 μM Se(VI) to Se(O) in 75Se radiotracer incubations of washed-cell suspensions of B. arsenicoselenatis and B. selenitireducens grown with nitrate plus Se(VI)

| Conditiona | Se(VI) removedc (nmol ml−1) | % Removed | Se(O) recoveredd (nmol ml−1) | % Recovered |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. arsenicoselenatis | 51.9 | 98.2 | 50.2 | 95.0 |

| B. arsenicoselenatis killedb | −0.4 | 2.2 | 3.5 | |

| B. selenitireducens | 4.0 | 7.9 | 1.5 | 3.0 |

Incubated for 1 h with 15 mM lactate plus 5 mM nitrate.

Four percent formalin added to cells.

As determined from counts in the filtrate.

As determined from counts recovered in the pellet.

DISCUSSION

S. barnesii is a lithotroph, able to grow with selenate, nitrate, nitrite, thiosulfate, elemental sulfur, Fe(III), Mn(IV), fumarate, arsenate, dimethyl sulfoxide, or trimethylamine-N-oxide as an anaerobic electron acceptor or with oxygen under microaerophilic conditions (8, 12, 24). It is assigned to the ɛ subgroup of the class Proteobacteria, a taxonomic feature which distinguishes it from T. selenatis, which belongs to the β subgroup (23), as well as from B. arsenicoselenatis, which is assigned to the low-G+C gram positives (26). In an earlier report, we noted that cell suspensions of nitrate-grown S. barnesii did not reduce 5 mM selenate and, conversely, selenate-grown cells did not reduce 10 mM nitrate (12). Previous work with estuarine sediment slurries indicated that reduction of 5 mM selenate was strongly inhibited by 10 mM nitrate (15) and that injection of 20 mM nitrate into intact sediment cores caused significant inhibition of the reduction of 20 μM selenate in sediments taken from two Se-contaminated sites in Nevada (22). These observations led to the idea that it was first necessary to remove nitrate from Se-contaminated wastewaters before selenate could be removed by bacterial reduction, and several treatment schemes that employed this concept were devised (6, 11, 16).

However, the above conclusion is skewed in the sense that the experiments were conducted at exceptionally high concentrations of either selenate or nitrate, or both. Thus, although the results have some physiological significance, they may have only limited relevance for treatment of wastewaters. Levels of nitrate and selenate in drainage wastewaters are low millimolar and micromolar, respectively, a condition which was not previously examined in our lab. Our results with intact sediments at in situ nitrate and selenate concentrations indicated that reduction of these anions occurs simultaneously within the same depth horizon (14), which would suggest that they are not necessarily mutually exclusive processes. This argues against nitrate interference with selenate reduction, even when the latter ion is present at only micromolar concentrations. Indeed, the reduction potential (E′0) for the Se(VI)-Se(IV) couple (+440 mV [4]) is comparable to that of the NO3−-NO2− couple (+433 mV [27]), and the corresponding free energy changes (ΔG′°) associated with the oxidation of lactate are −85.8 kJ/mol e− and −57.8 kJ/mol e− (8, 12). For the purpose of a simple comparison, we can use H2 as the electron donor and apply it to the actual concentrations of 5 mM for nitrate and 0.05 mM for selenate employed in the cell suspension experiments to calculate the free energy change associated with the following equations: SeO4⩵+ H2→SeO3⩵ + H2O (ΔG′° = −189.4 kJ) and NO3− + H2→NO2− + H2O (ΔG′° = −176.6 kJ). It is evident that thermodynamic considerations slightly favor respiration of selenate over nitrate under these conditions rather than the reverse. Therefore, instances in which nitrate reduction occurs prior to selenate reduction (Fig. 4) must be attributed to physiological, kinetic, or enzymatic factors (e.g., substrate affinities, expression, and regulation) associated with the nitrate and selenate reductases rather than free energy yields of the reactions.

S. barnesii has a constitutive selenate reductase capable of reducing submillimolar levels of selenate when grown on fumarate, nitrate, thiosulfate, or arsenate (Fig. 1). When normalized to cell density, the activity was nearly 10-fold higher in fumarate-grown cells (Fig. 1A) than in nitrate-grown cells (Fig. 1C). This could explain the previously observed inability of nitrate-grown cells to reduce ∼5 mM selenate over a comparable time (12). Selenate reductase activity in nitrate-grown cells was low and removed only ∼61% of the available selenate by 17 h, after which time activity ceased (Fig. 1C). In contrast, nitrate-grown cells were able to achieve a complete reduction of submillimolar selenate within 1 to 7 h if they were resuspended with 5 mM nitrate and an excess supply of lactate (Fig. 3 and 6). The presence of millimolar nitrate levels in the milieu enhanced the ability of S. barnesii to reduce submillimolar selenate by keeping the cells at a high state of metabolic activity. This avoided any physiological constraints caused by the lack of adequate amounts of electron acceptor (30).

There was a simultaneous reduction of nitrate with selenate regardless of whether S. barnesii was previously grown on selenate (Fig. 2) or nitrate (Fig. 3). The rates of reductase activity, when normalized to cell abundance, were markedly higher with the oxyanion used for growth than with the nongrowth electron acceptor (4-fold for selenate; 11-fold for nitrate). Previously, we reported that methyl viologen oxidation by membranes from nitrate- or selenate-grown cells also displayed substantial activity when linked to the corresponding nongrowth electron acceptor (25). These observations give evidence for the presence of two distinct reductases in S. barnesii: a selenate reductase and a nitrate reductase. Also, it seems that low activity levels of each enzyme may be constitutive during growth on the opposite oxyanion. A similar situation occurs in T. selenatis (17).

Kinetic experiments with membrane preparations (Table 3) reveal that similar Kms were achieved for selenate reduction in nitrate-grown cells (23.1 μM) and that in selenate-grown cells (13.1 μM), indicating that they are carried out by the same enzyme. These values compare favorably with the purified selenate reductase of T. selenatis, which displays a Km of 16 μM (19). There was even closer agreement for the Kms displayed for nitrate reduction in S. barnesii (68 and 62 μM), again indicating that it is carried out by the same enzyme. One interpretation is that there are discrete selenate and nitrate reductases which display these Kms and that they are constitutive in nitrate- and selenate-grown cells. Alternatively, because selenate does not inhibit nitrate reduction (Table 1) while nitrate inhibits selenate reduction in both nitrate-grown and selenate-grown cells (Table 2), it is also possible that this constitutive selenate reductase is capable of some nitrate reduction. A complicating factor is that membranes from nitrate-grown cells exhibited biphasic kinetics for selenate (Fig. 6A) as well as nitrate (Fig. 6B). This enzyme appears to be a nitrate reductase because it exhibits a much stronger affinity for nitrate (Km = 0.7 μM) than does the constitutive enzyme (Km = 62 to 68 μM). Apparently, this high-affinity nitrate reductase can also reduce selenate but with a much lower affinity (Km = 4,085 μM) than that displayed by the constitutive selenate reductase.

We observed no inhibitory effect on nitrate consumption by selenate (Table 1), but there was a consistent partial inhibition of selenate reduction by nitrate (Table 2). One interpretation is that nitrate affects the ability of the inducible, high-affinity nitrate reductase to reduce selenate, but this does not explain the partial inhibition by nitrate in selenate-grown cells which lacked this high-affinity nitrate reductase (Table 3). The clearest explanation is that some nitrate reduction is achieved by the constitutive selenate reductase and hence that there is no discrete “constitutive” nitrate reductase in selenate-grown cells. The Se(VI) reductase from S. barnesii has yet to be purified and characterized, but that from T. selenatis is specific only for selenate and does not reduce nitrate (19). If the selenate reductase of S. barnesii is also substrate specific, there are several other explanations for the observed partial inhibition by nitrate of selenate reduction. One possibility is that there is yet another molybdenum-containing enzyme present in S. barnesii which has a broad substrate specificity. For example, dimethyl sulfoxide and trimethylamine-N-oxide reductases contain molybdenum and have broad substrate affinities (28). In such a situation, nitrate addition would result in a total inhibition of the trimethylamine-N-oxide enzyme’s ability to reduce Se(VI) but would not constrain the true selenate reductase of S. barnesii. Another possibility is that both these reductases are linked to multiple-component electron transport chains and that some of the components operate in common. Clearly, the reduction of selenate and nitrate by intact cells of S. barnesii is a complex phenomenon, and it involves more processes than just those mediated by only two singularly specific enzymes. For the purpose of bioremediation, however, it is important not to lose sight of the fact that nitrate caused only a partial inhibition of selenate reduction (Table 2) and that both selenate and nitrate reduction are achieved quickly in nitrate-grown cells (Fig. 3 and 4).

In contrast to the results obtained with S. barnesii, neither B. arsenicoselenatis nor B. selenitireducens exhibited a constitutive selenate reductase when grown on nitrate (Fig. 5). The selenate reductase of B. arsenicoselenatis was present when cells were grown with nitrate plus selenate, and resuspended cells effectively reduced 50 μM selenate to Se(O) (Table 3), which suggests that this organism may also have some bioremediative potential but that its selenate reductase must first be induced. No selenate reduction was apparent in B. selenitireducens cells, even when they were grown with selenate plus nitrate (Table 3). B. selenitireducens does not grow on selenate (26), and the results we report here show that this organism cannot effectively sequester selenate as Se(O), although it can achieve this readily with selenite. Thus, B. selenitireducens may have a specific utility as a bioremediative agent for wastewaters which have selenite as the major dissolved Se species, such as those that are generated from petroleum refining.

Radiolabel experiments with S. barnesii reveal that it can rapidly sequester 50 μM selenate as Se(O) (Fig. 7). The low Kms for S. barnesii selenate reductases (Table 3) are in the range of dissolved selenium oxyanions that occur in wastewaters, but we wished to determine if the reductases are effective at lowering the selenate-selenite levels to below ∼63 nM, the discharge value being proposed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (18). Residual concentrations of “unreacted” counts remaining in solution indicate that within an hour the concentration had dropped to ∼120 nM (for S. barnesii) and ∼900 nM (for B. arsenicoselenatis), values which represent removal of >98% of the initial concentration. However, the actual amount of selenate plus selenite in these samples was very low relative to the total residual counts. As resolved by high-performance liquid chromatography and gamma counting of the collected fractions, the residual concentrations of selenium oxyanions accounted for only a few percent of the total residual counts in solution. Therefore, the actual levels of selenium oxyanion removal were 99.99% for S. barnesii and 99.9% for B. arsenicoselenatis. The most likely interpretation of this data is that the bulk of these “residual” counts represent colloid-sized 75Se(O) which had passed through the 0.2-μm-pore-size filter during centrifugation-filtration. The analytically determined amounts of residual selenate plus selenite in solution for S. barnesii were 7 and 19 nM when incubated with 0 and 50 μM nitrate, and those for B. arsenicoselenatis were 50 nM. For S. barnesii incubated with 5 mM nitrate, the residual selenium oxyanion concentration was 110 nM. Collectively, these values are either below or near the proposed new standard (∼63 nM) for discharge into the environment (18). Therefore, both S. barnesii and B. arsenicoselenatis can be favorably considered as potential candidates for bioremediating seleniferous agricultural wastewaters or the alkaline brines formed upon their evaporative concentration. Thus, further experiments with bench top (9) and pilot-plant-scale (2) digesters, which have been done with T. selenatis, would be justified for these organisms as well.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to D. Newman and J. T. Hollibaugh for helpful comments on an earlier draft of the manuscript and to S. Lawrence for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Smith J G, Struhl K. Short protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cantafio A W, Hagen K D, Lewis G E, Bledsoe T L, Nunan K M, Macy J M. Pilot-scale selenium bioremediation of San Joaquin drainage water with Thauera selenatis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:3298–3303. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.9.3298-3303.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeMoll-Decker H, Macy J M. The periplasmic nitrite reductase of Thauera selenatis may catalyse the reduction of selenite to elemental selenium. Arch Microbiol. 1993;160:241–247. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doran J W. Microorganisms and the biological cycling of selenium. Adv Microb Ecol. 1982;6:1–32. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dowdle P R, Oremland R S. Microbial oxidation of elemental selenium in soil slurries and bacterial cultures. Environ Sci Technol. 1998;32:3749–3755. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerhardt M B, Green F B, Newman R D, Lundquist T J, Tresan R B, Oswald W J. Removal of selenium using a novel algal bacterial process. Res J Water Pollut Control Fed. 1991;63:799–805. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hobbie J E, Daley R L, Jaspar S. Use of Nuclepore filters for counting bacteria for fluorescence microscopy. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1977;33:1225–1228. doi: 10.1128/aem.33.5.1225-1228.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laverman A M, Switzer Blum J, Schaefer J K, Phillips E J P, Lovley D R, Oremland R S. Growth of strain SES-3 with arsenate and other diverse electron acceptors. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:3556–3561. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.10.3556-3561.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Macy J M, Lawson S, DeMoll-Decker H. Bioremediation of selenium oxyanions in San Joaquin drainage water using Thauera selenatis in a biological reactor system. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1993;40:588–594. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oremland R S. Biogeochemical transformations of selenium in anoxic environments. In: Frankenberger W T Jr, Benson S, editors. Selenium in the environment. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 1994. pp. 389–420. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oremland R S. Selenate removal from wastewaters. U.S. patent 5,009,786. April 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oremland R S, Switzer Blum J, Culbertson C W, Visscher P T, Miller L G, Dowdle P, Strohmaier F E. Isolation, growth, and metabolism of an obligately anaerobic, selenate-respiring bacterium, strain SES-3. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:3011–3019. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.8.3011-3019.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oremland R S, Culbertson C W. Evaluation of methyl fluoride and dimethyl ether as inhibitors of aerobic methane oxidation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:2983–2992. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.9.2983-2992.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oremland R S, Steinberg N A, Maest A S, Miller L G, Hollibaugh J T. Measurement of in situ rates of selenate removal by dissimilatory bacterial reduction in sediments. Environ Sci Technol. 1990;24:1157–1164. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oremland R S, Hollibaugh J T, Maest A S, Presser T S, Miller L G, Culbertson C W. Selenate reduction to elemental selenium by anaerobic bacteria in sediments and culture: biogeochemical significance of a novel, sulfate-independent respiration. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:2333–2343. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.9.2333-2343.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Owens L P. Bioreactors in removing selenium from agricultural drainage water. In: Frankenberger W T Jr, Engberg R A, editors. Environmental chemistry of selenium. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 1997. pp. 501–514. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rech S A, Macy J M. The terminal reductases for selenate and nitrate respiration in Thauera selenatis are two distinct enzymes. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:7316–7320. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.22.7316-7320.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Renner R. EPA decision to revise selenium standards stirs debate. Environ Sci Technol. 1998;32:350. doi: 10.1021/es9836388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schröder I, Rech S, Krafft T, Macy J M. Purification and characterization of the selenate reductase from Thauera selenatis. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:23765–23768. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.38.23765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Squires R C, Groves G R, Raymond G, Johnston W R. Economics of selenium removal from drainage water. J Irrigation Drainage Eng. 1989;115:48–57. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steinberg N A, Switzer Blum J, Hochstein L, Oremland R S. Nitrate is a preferred electron acceptor for growth of selenate-respiring bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:426–428. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.1.426-428.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steinberg N A, Oremland R S. Dissimilatory selenate reduction potentials in a diversity of sediment types. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:3550–3557. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.11.3550-3557.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22a.Stolz, J. F. Unpublished data.

- 23.Stolz, J. F., and R. S. Oremland. Bacterial respiration of arsenic and selenium. FEMS Microbiol. Rev., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Stolz J F, Ellis D J, Switzer Blum J, Ahmann D, Oremland R S, Lovley D R. Sulfurospirillum barnesii sp. nov. and Sulfurospirillum arsenophilus sp. nov., new members of the Sulfurospirillum clade of the ɛ-Proteobacteria. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1999;49:1177–1180. doi: 10.1099/00207713-49-3-1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stolz J F, Gugliuzza T, Switzer Blum J, Oremland R, Martinez Murillo F. Differential cytochrome content and reductase activity in Geospirillum barnesii strain SES3. Arch Microbiol. 1997;167:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s002030050408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Switzer Blum J, Burns Bindi A, Buzzelli J, Stolz J F, Oremland R S. Bacillus arsenicoselenatis sp. nov., and Bacillus selenitireducens sp. nov.: two alkaliphiles from Mono Lake, California that respire oxyanions of selenium and arsenic. Arch Microbiol. 1998;171:19–30. doi: 10.1007/s002030050673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thauer R K, Jungermann K, Decker K. Energy conservation in chemotrophic bacteria. Bacteriol Rev. 1977;41:100–180. doi: 10.1128/br.41.1.100-180.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weiner J H, MacIssac D P, Bishop R E, Bilous P T. Purification and properties of Escherichia coli dimethyl sulfoxide reductase, an iron-sulfur molybdoenzyme with broad substrate specificity. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:1505–1510. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.4.1505-1510.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weres O, Jaouni A, Tsao L. The distribution, speciation, and geochemical cycling of selenium in a sedimentary environment, Kesterson Reservoir, California, U.S.A. Appl Geochem. 1989;4:543–563. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zehr J P, Oremland R S. Reduction of selenate to selenide by sulfate-respiring bacteria: experiments with cell suspensions and estuarine sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:1365–1369. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.6.1365-1369.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]