Dear Editor,

In this journal, Mendez-Brito and colleagues reviewed the effectiveness of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) against COVID-19. [1] We would like to contribute to this discussion with analyzing the recent experience of applying NPIs in Lithuanian.

Lithuania has been relatively successful in managing the first peak of a COVID-19 outbreak (March – May 2020). [2] However, the subsequent wave had much worse consequences. In December 2020, Lithuania had recorded unacceptably high COVID-19 morbidity and mortality indicators. The main reason for this was that previous Government seriously lagged behind in implementing adequate non-pharmaceutical measures. The newly elected Government imposed a strict lockdown (December 16, 2020), which lasted until June 30, 2021. [3] In order to prevent a long lasting lockdowns and to limit the spread of SARS-CoV-2 infections and to motivate for an uptake of vaccination, Lithuania introduced the COVID-19 vaccination passport (in Lithuanian “Galimybių pasas”). The COVID-19 passport was issued to people, who 1) are fully vaccinated; or 2) has a laboratory confirmed previous COVID-19 infection. Holders of these passports had the right to visit shopping malls, concerts, restaurants and other facilities. The use of COVID-19 passport was terminated on February 4th, 2022. The aim of this study was to evaluate a potential impact of COVID-19 passports to epidemiological situation in Lithuania.

We have evaluated the potential impact of the COVID-19 passport to epidemiological situation in Lithuania by the construction of three main possible scenarios without having a COVID-19 passport. Models of the three scenarios were constructed according to the simplified method of epidemic dynamics prognosis, which is described in a separate paper.1 [4] The proposed approach is based on a modified SIR model with assumptions that the number of daily new infected cases is the most reliable parameter allowing the estimate of the disease spreading due to lockdown measures where the number of infections is much smaller than the number of people to be potentially infected.

In order to damp daily and weekly fluctuations, and estimated the parameter were smoothed by moving average, where each average is calculated over a sliding window of length days:

| (1) |

where time is measured in days.

The daily growth rate of new infection cases was estimated on the basis of smoothed daily new infection cases

| (2) |

when is growing and is falling when . If acceleration of the infection is slowing, then is reducing and reaches peak when cross 1.

The parameter can be interpreted as the average daily reproduction number [5].

The second assumption of the approach is that if lockdown condition is stable, then is constant and having value matching effectiveness of lockdown measures.

In order to predict COVID-19 disease spread in infected country or region with imposed lockdown measures, a model of the growth rate of new cases needs to be developed. Model of is constructed on expected conditions for virus spreading based on data of disease previous dynamics.

So, if we have model of we can predict number of daily new infections :

| (2a) |

It is already known, from that non-pharmaceutical interventions limits population mobility and, consequently, contacts. [1] Reaction of the COVID-19 spread to lockdown measures comes with some delay of 2–4 weeks. [4]

The Lithuania COVID-19 passport was introduced on May 24, 2021, but was applied in the full validity only on September 13, 2021, when it became clear that the rise in SARS-Cov-2 infections were beginning to threaten the stability of the public health system. In early September, the average number of infections exceeded 670 infections per day (Fig. 1 ), 10 deaths per day, and the number of hospitalized COVID-19 patients at – 600.2 As people returned from the summer holidays, contacts at workplaces and entertainment and retail events increased. [6] The introduction of COVID-19 passport has limited people-to-people contacts at work, public transport, shopping and entertainment, and retail events. Due to human behavior inertia, the effect of COVID-19 passport on contact reduction lasted for about 1–2 weeks.

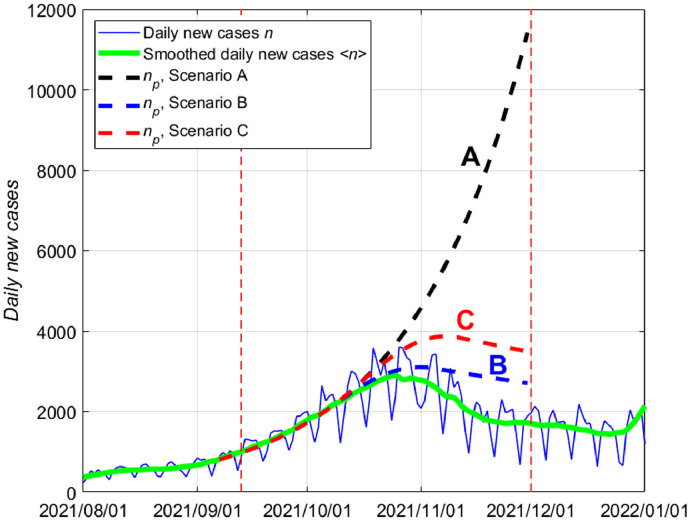

Fig. 1.

Dynamics of the daily new cases , daily new cases smoothed by moving average of a sliding window of 15 days, and modelled scenarios of the daily new cases .

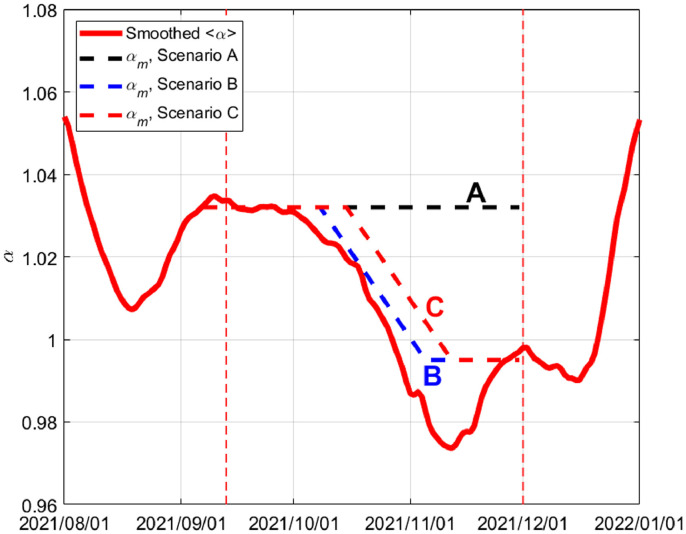

The decrease in contacts with additional delays also started to affect the spread of the virus. The growth rate of new infection cases in early September was around and began to decline two weeks (since early October) since the introduction of COVID-19 passport. In the October last decade, reached 1, marking the peak of COVID-19 infection (Fig. 2 ), after which the number of infections began to decline and ranged from 0.974 to 0.998. Omicron was first identified in Lithuania on December 15, 2021, although it is likely that it appeared earlier. The infectivity of the Omicron strain was so high that COVID-19 passport quarantine measures were no longer sufficient to stop the new virus strain and began to grow relentlessly and exceeded 1 in the second half of December, reaching 1.06 in early January 2022.

Fig. 2.

Dynamics of the daily growth rate of new cases smoothed by moving average of a sliding window of 15 days, and modelled scenarios of .

If the full validity of the COVID-19 passport would not been introduced on September 13, 2021, and if people's behavior (self-protection, mobility and other safety measures) did not continue to change, it is likely that the growth rate of new infection cases would have adhered to the same value as before the introduction of COVID-19 passport () and the number of infections would have continued to grow exponentially until it reached 11,000–12,000 infections per day by the end of December (Scenario A). Such a scenario is considered unlikely, as people were not only passively responding to the quarantine measures being introduced, but were also actively considering the potential risk of infection. Therefore, when the number of infections and their consequences (hospitalizations, intensive care units admissions, and deaths) exceed the psychological threshold, people themselves actively begin to beware and avoid contact. Against this background, we developed two other scenarios (B and C) related to human behavior such that when number of daily new infections reaches the psychological threshold of 1000 infections per day in Scenario B, people start responding to infections in late September (1 week later) and in early October (2 weeks later) for Scenario C.

There were a total of 163,307 officially registered COVID-19 infections in the period from the introduction of the COVID-19 passport on 13/09/2021 up to 01/12/2021. According to our calculations, under Scenario A 337,632 infections would be expected (i.e. +174,325 more were registered), while under Scenario B - 189,953 infections (+26,646), and under Scenario C - 220,368 infections (+57,061).

There was a total of 2065 COVID-19 deaths officially registered (deaths/infections ratio ≈ 1.26%) in the period from the introduction of the COVID-19 passport on 13/09/2021 until 01/12/2021. Our estimates suggest, that under Scenario A number of deaths from COVID-19 could have reached 4269 (+2204 more than it was), and for Scenario B – 2402 (+337) and Scenario C – 2787 (+722).

The COVID-19 passport policy has caused many debates in Lithuania. However, according to a Lithuanian National Broadcaster LRT poll (December 2, 2021), 53% of Lithuanians evaluated COVID-19 passports positively. [7] A study by Walkowiak et al. (2021) estimates, that Lithuania's strict policy resulted in a 12.34 p.p. increase in the vaccination rate in Lithuania. [8] According to our preliminary assessment, the COVID-19 passport could have helped to prevent approximately 26,000 – 57,000 COVID-19 infections and 330 - 720 deaths in the period between 13/09/2021 and 01/12/2021 in the country. More likely this effect could be even more significant, as we evaluated only the impact of COVID-19 passport to people's behavior. An increased vaccination level was not included in this analysis. Studies from other countries have reported similar positive impact of COVID-19 passports to epidemiological trends. [9,10] This suggests that vaccination passports could be an effective measure in tackling future pandemics. However, legal, social and ethical aspects should be considered.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: MS, AD. Data analysis and modeling: AD, GS, EM, RN. Writing-original draft: MS, AD. Writing-review and editing: MS, AD, GS, EM, RN.

Funding

This research received no specific grants from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of Competing Interest

MS and AD are members of the Health Experts’ Council under the President of the Republic of Lithuania.

Footnotes

Data for these calculations can be downloaded from https://storage.covid19datahub.io/rawdata-1.zip

Data can be downloaded from https://storage.covid19datahub.io/rawdata-1.zip

References

- 1.Mendez-Brito A., El Bcheraoui C., Pozo-Martin F. Systematic review of empirical studies comparing the effectiveness of non-pharmaceutical interventions against COVID-19. J Infect. 2021;83:281–293. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2021.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Šmigelskas K., Petrikonis K., Kasiulevičius V., Kalediene R., Jakaitienė A., Kaselienė S., et al. SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence in Lithuania: results of national population survey. Acta Med Litu. 2021;28:48–58. doi: 10.15388/Amed.2020.28.1.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vaišnorė R., Jakaitienė A. COVID-19 reproduction number and non-pharmaceutical interventions in Lithuania. Proc Lithuanian Math Soc, Ser. A. 2021;62:27–37. doi: 10.15388/LMR.2021.25218. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Džiugys A., Bieliūnas M., Skarbalius G., Misiulis E., Navakas R. Simplified model of COVID-19 epidemic prognosis under quarantine and estimation of quarantine effectiveness. Chaos Solitons Fract. 2020;140 doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.110162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallinga J., Teunis P. Different epidemic curves for severe acute respiratory syndrome reveal similar impacts of control measures. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160:509–516. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Google. COVID-19 Community Mobility Reports - Lithuania. Available at: https://www.google.com/covid19/mobility/.

- 7.Lietuvos radijas ir televizija (LRT). Iš pirmų lūpų: kas Lietuvos gyventojus paskatino skiepytis ir kaip jie vertina galimybių pasą. Vilnius: LRT; 2021 Available at: https://www.lrt.lt/naujienos/lietuvoje/2/1552636/is-pirmu-lupu-kas-lietuvos-gyventojus-paskatino-skiepytis-ir-kaip-jie-vertina-galimybiu-pasa.

- 8.Walkowiak M.P., Walkowiak J.B., Walkowiak D. COVID-19 Passport as a factor determining the success of national vaccination campaigns: does it work? The case of Lithuania vs. Poland. Vaccines. 2021;9 doi: 10.3390/vaccines9121498. 1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oliu-Barton M., Pradelski B.S.R., Woloszko N., et al. The effect of COVID certificates on vaccine uptake, health outcomes and the economy. Working Paper 01/ 2022, Bruegel. Available at: https://www.bruegel.org/2022/01/the-effect-of-covid-certificates-on-vaccine-uptake-public-health-and-the-economy/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Mills M.C., Rüttenauer T. The effect of mandatory COVID-19 certificates on vaccine uptake: synthetic-control modelling of six countries. Lancet Public Health. 2022;7:e15–e22. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00273-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]