Abstract

Background.

Interferon-gamma release assay utilization in pediatric tuberculosis (TB) screening is limited by a paucity of longitudinal experience, particularly in low-TB burden populations.

Methods.

We conducted a retrospective review of QuantiFERON (QFT)-TB Gold results in San Francisco children from 2005 to 2008. Concordance with the tuberculin skin test (TST) was analyzed for a subset of children. Progression to active disease was determined through San Francisco and California TB registry matches.

Results.

Of 1092 children <15 years of age, 853 (78%) were foreign-born, and 136 (12%) were exposed to active TB cases (contacts). QuantiFERON tests were positive in 72 of 1092 (7%) children; 15 of 136 (11%) recent contacts; 53 of 807 (7%) foreign-born noncontacts; and 4 of 149 (3%) US-born noncontacts. QuantiFERON-negative/TST-positive discordance was seen more often in foreign-born/bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG)-vaccinated children <5 years of age (52 of 56, 93%) compared to those ≥ 5 years of age (90 of 123, 73%; P = .003). Foreign-born, BCG-vaccinated children were more than twice as likely to have a discordant (79%) result as US-born, non-BCG-vaccinated children (37%; P < .0001). During 5587 person-years of follow-up of untreated children, including 146 TST-positive/QFT-negative children, no cases of active TB were identified, consistent with a negative predictive value of 100%.

Conclusions.

Our experience supports the use of QFT to evaluate latent TB infection in children, particularly young BCG-vaccinated children. The proportion of QFT-positive results correlated with risk of exposure, and none of the untreated QFT-negative children developed TB. The low QFT-positive rate highlights the need for more selective testing based on current epidemiology and TB exposure risk.

Keywords: interferon-gamma release assays, pediatrics, tuberculosis

INTRODUCTION

Diagnostic tests that identify pediatric latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) and reliably exclude infection in asymptomatic individuals, regardless of exposure, is important because children under age 4, and between ages 10 and 15, are at greater risk for rapid progression from asymptomatic infection to active tuberculosis (TB) disease than adults [1, 2]. Despite well known performance limitations, such as poor specificity due to tuberculin cross-reactivity with nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) and bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG), the tuberculin skin test (TST) is routinely used for LTBI screening in children [3–5]. False-positive TST results are of most concern in low-TB incidence areas, such as the United States, which have significant foreign-born, BCG-vaccinated populations [5–8].

In the last decade, interferon-gamma release assays (IGRAs) became available for the evaluation of LTBI [4, 9]. Diverse studies, mainly performed in adults, demonstrate the superior specificity of IGRAs in populations at risk for TB infection. When compared with the TST, IGRA results better correlate with TB exposure history and, unlike the TST, lack cross-reactivity with the majority of NTMs and BCG [10–13]. Although pediatric studies are limited, the accumulating evidence indicates that IGRAs are highly specific and well correlated with exposure history in children [14–19].

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Red Book [20] recommends the preferential use of IGRAs over the TST for TB testing in children ≥5 years who are BCG vaccinated; however, the TST is preferred, and IGRAs are acceptable for all children age <5 with the qualification that IGRAs should generally not be used in those age <2 due to lack of data [20].Despite these guidelines, the use of IGRAs in pediatrics is variable and limited, including use in older BCG-vaccinated children. In the Baltimore Department of Public Health, QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-tube (QFT-GIT) use was significantly lower in younger patients: 7% of those ages 2–12 and 64% of those ages 12–17, compared to 76% for individuals age ≥18 [21].Issues raised regarding the routine use of IGRAs in pediatrics include the following: rates of indeterminate results in young children, interpretation and management of TST-positive/IGRA-negative results, operational issues regarding phlebotomy in young children, and lack of longitudinal experience informing sensitivity and predictive value [4, 8, 22–28].

The City and County of San Francisco has a population of approximately 826 000 (2012); 36% are foreign-born (2007–2011; http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/06/06075.html). Tuberculosis incidence in San Francisco is significantly higher than the United States with an annual average rate of 16.0 cases per 100 000 (range, 14.1–17.8 per year) (program data, 2005–2012; www.sftbc.org) compared to 4.5 per 100 000 for the United States during the same time frame [29]. On average, 4 children <15 years old are diagnosed with active TB each year, representing 3% of the total TB incidence in San Francisco.

The San Francisco Department of Public Health (SFDPH) regularly utilizes QFT for TB screening in populations less likely to return for TST reading (ie, homeless), BCG-vaccinated persons, and other high-risk groups, including children [30]. Children tested for TB are new immigrants, contacts to active TB cases, and US-born children, with or without an identified TB risk, whose healthcare providers elect to use a TB test to fulfill school entry requirements. In this study, we retrospectively examine results of QFT tests performed on children in San Francisco between 2005 and 2008, evaluated concordance rates in those who were also tested with the TST, and report results from San Francisco and California TB registry matches to identify the development of active TB.

METHODS

Tuberculosis Screening and Evaluation

The San Francisco Department of Public Health operates 12 community-based, primary care health centers and collaborates with more than 20 community-based organizations that routinely screen children for TB in accordance with local and national guidelines [30].

During the study period, community-based screening involved symptom review, risk assessment, and a TST or QFT. If either the symptom screen or TST/QFT results were positive, patients were referred to the TB clinic for a chest radiograph and medical evaluation. Known contacts to contagious TB cases or children requiring screening upon immigration to the United States had initial screening performed at the TB clinic. During the TB clinic evaluation, if a prior TST was suspected to be falsely positive, based on a lack of significant exposure and/or a history of BCG vaccination, the physician may have ordered a QFT.

In asymptomatic children with a negative chest radiograph, a final diagnosis of LTBI was based on the results of the positive QFT (regardless of the TST result, if performed). Nevertheless, based on the physician’s individual assessment, a small subset of children with a negative QFT and a current or prior positive TST were given a final diagnosis of LTBI and were managed accordingly. In children with indeterminate QFT results, the test was generally repeated and the result of the subsequent test was used to determine LTBI status; if the result was again indeterminate (or the QFT was not repeated), the final diagnosis was based on the most recent TST result.

Window prophylaxis with isoniazid (INH) was recommended for contacts <5 years of age pending results of repeat testing 8 weeks from last exposure [20]. Some TST-positive children may have initiated LTBI treatment and subsequently discontinued the regimen upon being QFT-negative. In children given a final diagnosis of LTBI, a treatment regimen of 9 months of INH was recommended; however, not all children underwent treatment.

Testing

QuantiFERON-Gold ([QFT-G] second generation test) was initially performed at all testing sites. At select clinics, including the TB clinic, QFT-G was replaced by QFT-GIT (Gold In-TB, third-generation test) between January and December 2008. Blood was collected Monday through Thursday for QFT-G and Monday through Friday for QFT-GIT and submitted to the SFDPH laboratory.

Collection and laboratory processing were done according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), and specimens were incubated on site at the TB clinic or SFDPH laboratory, no more than 8 hours after specimen collection. Results were interpreted according to published guidelines [31]. Tuberculin skin testing was done Monday through Friday by the Mantoux method with Tubersol and interpreted according to published guidelines [30]; specifically, ≥10 mm induration was considered positive for all noncontacts and ≥5 mm induration for all contacts.

Study Eligibility

Children <15 years of age identified in the SFDPH laboratory information system as having a QFT test performed March 1, 2005–December 31, 2008 were included in the study. For children with more than 1 recorded QFT during the study period, the latest test result was included in the study. Children with missing foreign-born status and/or race/ethnicity were excluded from the analysis.

Tuberculosis Clinic and Registry Matching

QuantiFERON results identified in the SFDPH laboratory information system were matched to the TB clinic database using a unique SFDPH medical record number, first name, last name, and date of birth, to generate a subset of pediatric patients that (1) were evaluated at the TB clinic during the study period and either had a TST done and/or received LTBI treatment and (2) may have developed active TB after the study period. Race or ethnicity and gender were used to verify possible matches. In addition, QFT results were matched to the California Department of Public Health (CDPH) TB registry in August 2013 to passively identify children who may have developed active TB in San Francisco or elsewhere in California between March 1, 2005 and December 31, 2012. A preliminary match was performed to identify potential matches and included first name, last name, and birth year. The potential matches were rematched by first name, last name, full date of birth, sex, and race/ethnicity to confirm the final list of active TB cases.

Data Analysis

Categorical data were compared using Pearson’s χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test (when appropriate). The Cochran-Armitage test was used to assess test result trends by age group. The Mann-Whitney Wilcoxon test was used to compare mean follow-up times. Significance for all tests was assessed at alpha = 0.05. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). The University of California, San Francisco Committee on Human Research approved the study and the California Department of Public Health Committee on Human Research approved the match to the California TB Registry.

RESULTS

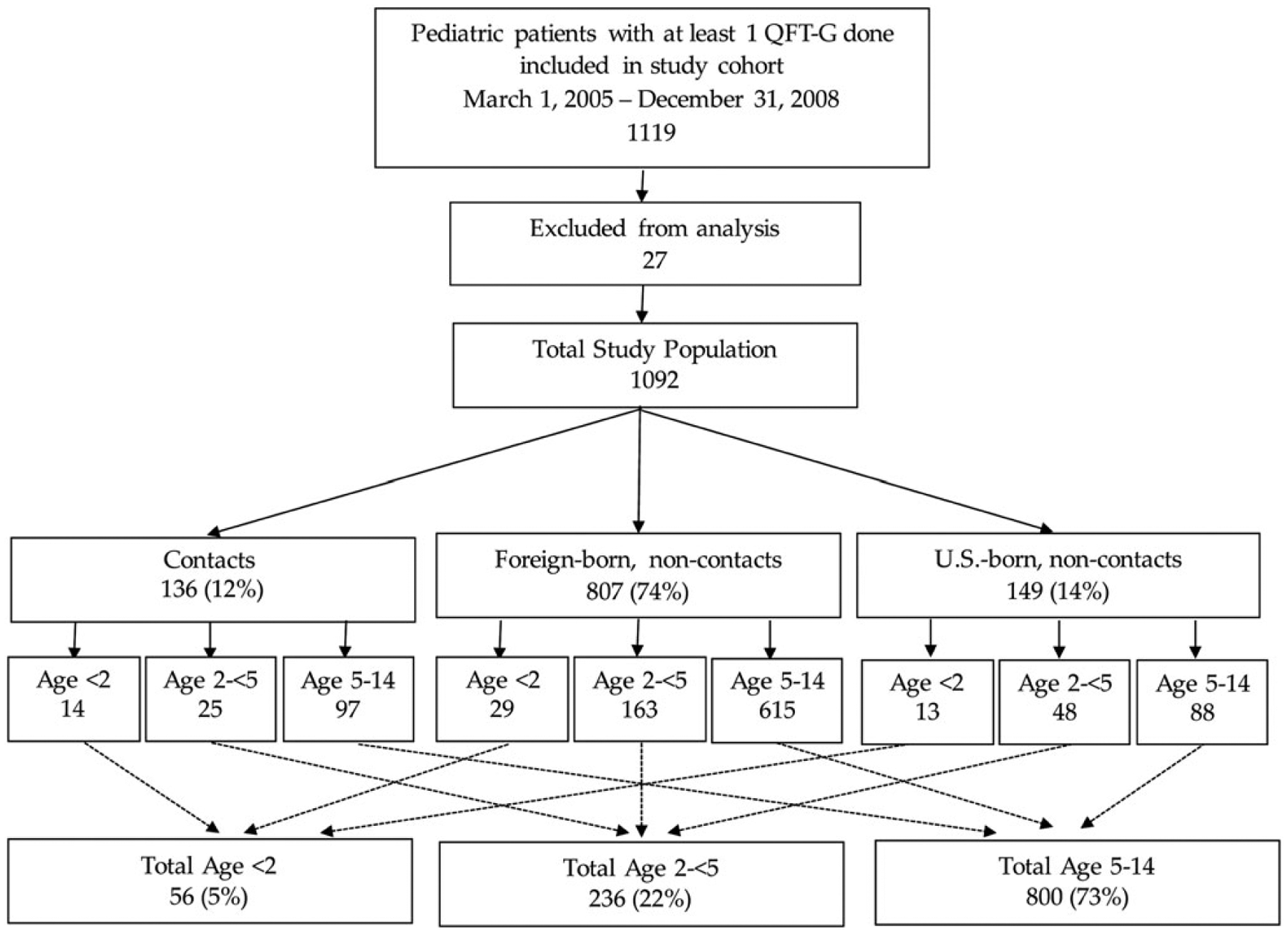

Between March 1, 2005 and December 31, 2008, 1119 children <15 years of age were tested with QFT. Due to missing foreign-born status and/or race/ethnicity, 27 (2%) were excluded from further analysis. The final study population included 1092 children (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study population by age and risk group. QFT-G, QuantiFERON-Gold.

The median age of children tested with QFT was 8.7 years (interquartile range [IQR], 4.7–12.2); 292 (27%) were <5 years of age, including 56 (5%) <2 years of age. The majority of children tested were foreign-born (78%) (Table 1). Overall, 136 children (12%) were tested as contacts to active TB cases. Children <2 years of age were more likely than other age groups to be tested due to being a recent contact to a TB case (P = .01).

Table 1.

Demographics of Children Tested With QuantiFERON by Age Group

| Demographic Group | Total | Age < 2 | Age 2 to < 5 | Age 5 to < 14 | P Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | ||

| Total | 1092 | 56 | 236 | 800 | |||||

| Male | 545 | (50) | 27 | (48) | 122 | (52) | 396 | (50) | .81 |

| Female | 547 | (50) | 29 | (52) | 114 | (48) | 404 | (51) | |

| Race/ethnicity | .0001 | ||||||||

| Asian | 735 | (67) | 36 | (64) | 133 | (56) | 566 | (71) | |

| Black | 63 | (6) | 2 | (4) | 14 | (6) | 47 | (6) | |

| Hispanic | 235 | (22) | 17 | (30) | 76 | (32) | 142 | (18) | |

| White | 59 | (5) | 1 | (2) | 13 | (6) | 45 | (6) | |

| Foreign-born | 853 | (78) | 32 | (57) | 167 | (71) | 654 | (82) | <.0001 |

| US-born | 239 | (22) | 24 | (43) | 69 | (29) | 146 | (18) | |

| Contact | 136 | (12) | 14 | (25) | 25 | (11) | 97 | (12) | .01 |

| Noncontact | 956 | (88) | 42 | (75) | 211 | (89) | 703 | (88) | |

Results of Interferon-Gamma Release Assays Testing

QuantiFERON results were not significantly different between test versions (P = .21; data not shown); therefore, results are presented in aggregate. Overall, 7% (72 of 1092) of children tested positive, 86% (943 of 1092) tested negative, and 7% (77 of 1092) had indeterminate results (Table 2). Older children (age 5–14) were more likely to have a QFT-positive result than children age <2 and age 2 to <5 (P < .001).

Table 2.

QuantiFERON Results by Age and Risk Group

| Total | Positive | Negative | Indeterminate | P Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | n | (%)* | n | (%)* | n | (%)* | ||

| Total | 1092 | 72 | (7) | 943 | (86) | 77 | (7) | |

| Age | .0001 | |||||||

| <2 | 56 | 1 | (2) | 44 | (79) | 11 | (20) | |

| 2 to <5 | 236 | 9 | (4) | 210 | (89) | 17 | (7) | |

| 5 to <15 | 800 | 62 | (8) | 689 | (86) | 49 | (6) | |

| Risk group | ||||||||

| Contact | 136 | 15 | (11) | 113 | (83) | 8 | (6) | .04 |

| Foreign-born (noncontact) | 807 | 53 | (7) | 700 | (87) | 54 | (7) | |

| US-born (noncontact) | 149 | 4 | (3) | 130 | (87) | 15 | (10) | |

| Risk group and age Contact | ||||||||

| <2 | 14 | 0 | (0) | 12 | (86) | 2 | (14) | .13† |

| 2 to <5 | 25 | 2 | (8) | 20 | (80) | 3 | (12) | |

| 5 to <15 | 97 | 13 | (13) | 81 | (84) | 3 | (3) | |

| Foreign-born (noncontact) | ||||||||

| <2 | 29 | 1 | (3) | 24 | (83) | 4 | (14) | .27† |

| 2 to <5 | 163 | 7 | (4) | 147 | (90) | 9 | (6) | |

| 5 to <15 | 615 | 45 | (7) | 529 | (86) | 41 | (7) | |

| US-born (noncontact) | ||||||||

| <2 | 13 | 0 | (0) | 8 | (62) | 5 | (38) | .005* |

| 2 to <5 | 48 | 0 | (0) | 43 | (90) | 5 | (10) | |

| 5 to <15 | 88 | 4 | (5) | 79 | (90) | 5 | (6) | |

Row percentage.

Pearson’s χ2 test.

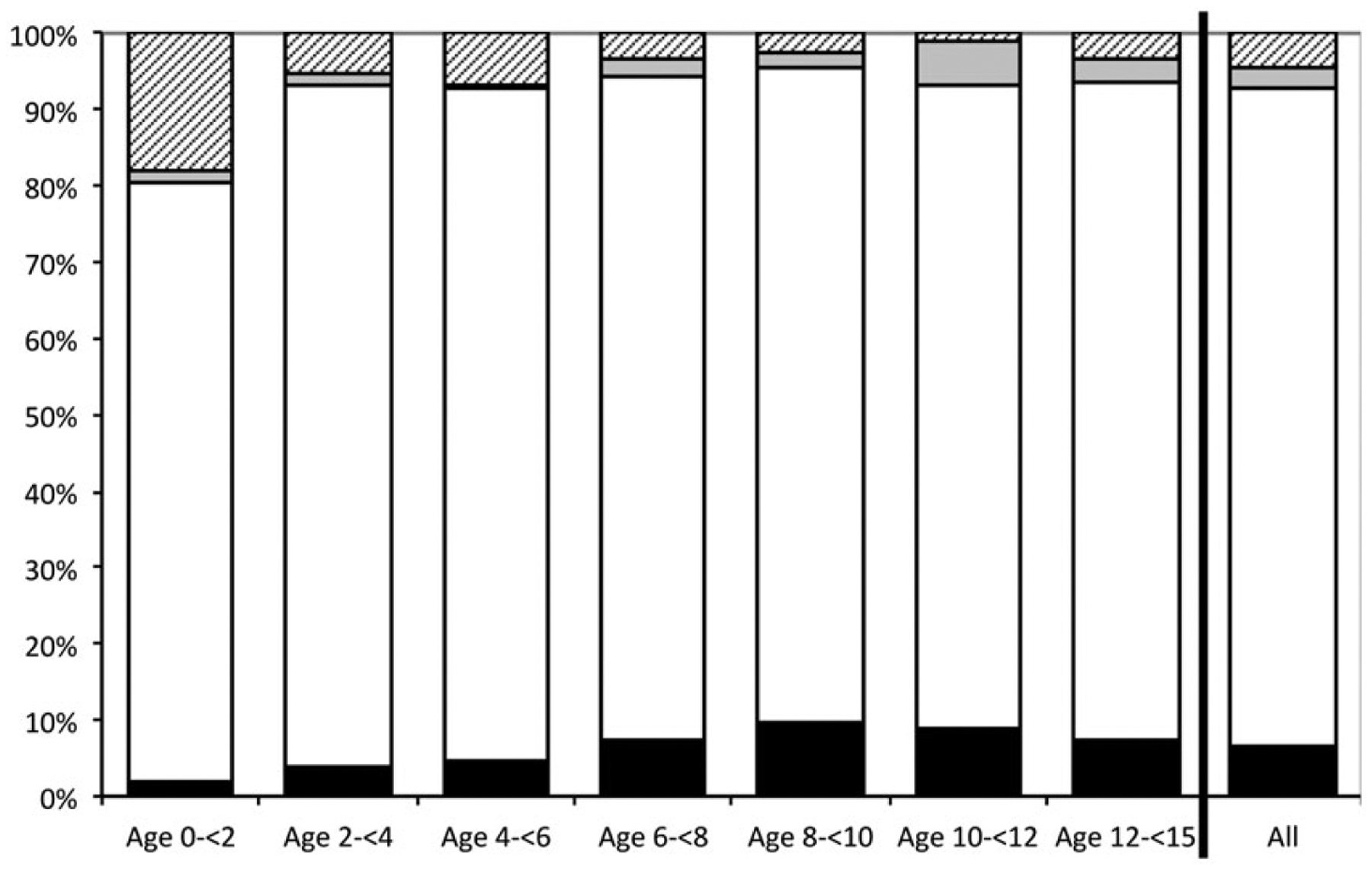

The percentage of positive QFT results were as follows: 11% (15 of 136) in children who were recent contacts to active TB cases: 7% (53 of 807) in foreign-born noncontacts, and 3% (4 of 149) in US-born noncontacts (P = .04). When stratified by risk group, age was not associated with positive results among contacts or foreign-born noncontacts. However, US-born noncontacts over 5 years of age were more likely to test positive than their younger counterparts (P = .005). There was no significant difference in positive results among US-born (10%, 9 of 90) and foreign-born contacts (13%, 6 of 46; P = .39) (data not shown). Overall, QFT-positive results increased steadily through age 9, from 2% to 10% (P = .02) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Pediatric QuantiFERON results stratified by age category. Solid black bars, positive results; solid white bars, negative results; solid gray bars, indeterminate, high nil results; hatched gray bars, indeterminate, low mitogen results.

QuantiFERON/Tuberculin Skin Test Discordance

A TST was done within 60 days before or after the QFT for 215 (61%) of 350 children evaluated at the TB clinic. QuantiFERON/tuberculin skin test discordance results by risk and age groups are presented in Table 3. A total of 158 (73%) had QFT-negative/TST-positive discordant results. There was no QFT-positive/TST-negative discordance because all children with both tests were TST-positive. When stratified by risk group, 37% (7 of 19) of contacts to active cases, 79% (142 of 179) of foreign-born or BCG-vaccinated, and 53% (9 of 17) of US-born, non-BCG-vaccinated children had discordant results. When the foreign-born/BCG-vaccinated group was stratified by age, the discordant rate was 93% (52 of 56) for children <5 years of age and 73% (90 of 123) for children ≥5 years of age (P = .003). Among the US-born/non-BCG-vaccinated children, discordance was not significantly different between age groups (P = .64).

Table 3.

QFT/TST Concordance by Risk Group and Age

| Risk Group and Age | Total | Concordant | % | Discordant | % | P Value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 215 | 57 | (27) | 158 | (73) | .03 |

| Contact | 19 | 12 | (63) | 7 | (37) | .42 |

| Foreign-born or BCG-vaccinated* (noncontacts) | 179 | 37 | (21) | 142 | (79) | .36 |

| US-born and not BCG-vaccinated (noncontacts) | 17 | 8 | (47) | 9 | (53) | .51 |

| Contact | ||||||

| Age <5 | 10 | 9 | (90) | 1 | (10) | .02 |

| Age 5–14 | 9 | 3 | (33) | 6 | (67) | |

| Foreign-born or BCG-vaccinated* (noncontacts) | ||||||

| Age <5 | 56 | 4 | (7) | 52 | (93) | .003 |

| Age 5–14 | 123 | 33 | (27) | 90 | (73) | |

| US-born and not BCG-vaccinated (noncontacts) | ||||||

| Age <5 | 8 | 3 | (38) | 5 | (63) | .64 |

| Age 5–14 | 9 | 5 | (56) | 4 | (44) |

Abbreviations: BCG, bacille Calmette-Guerin; QFT, QuantiFERON; TST, tuberculin skin test.

Fourteen US-born children were BCG-vaccinated.

P value for Fisher’s exact test.

Tuberculosis Clinic Evaluation Outcomes and Follow-up Status

Three hundred fifty (350, 32% of the study population) children received evaluation at the TB clinic. Seven (0.6%) children were suspected to have TB disease and all were started on a multidrug regimen. Five (0.5%) children, all QFT-positive, were subsequently confirmed to have active TB: 2 were culture-positive and TST-positive and 3 were clinically diagnosed due to radiologic improvement while on treatment. The 2 additional cases were <16 months old and were treated as clinical TB cases because of high risk for progression due to significant exposure to contagious TB (Table 4).

Table 4.

Characteristics of Children With Suspected and Confirmed Active TB

| Nativity | Age | Sex | Race/Ethnicity | Contact | QFT Result | TST Result | Confirmed Active Disease | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | US-born | 2 | M | Hispanic | Yes | Positive | Negative (history)* | Yes - Improved chest x-ray |

| 2 | US-born | 1 | M | White | Yes | Negative | Not done | No |

| 3 | US-born | <1 | M | Hispanic | Yes | Indeterminate | Negative | No |

| 4 | Foreign-born | 2 | M | Asian | No | Positive | Positive (history)** | Yes - Improved chest x-ray |

| 5 | US-born | 5 | M | Hispanic | No | Positive | Positive | Yes - Improved chest x-ray |

| 6 | US-born | 2 | M | Black | Yes | Positive | Positive | Yes - Culture-positive |

| 7 | Foreign-born | 12 | F | Asian | Yes | Positive | Positive | Yes - Culture-positive |

Abbreviations: QFT, QuantiFERON; TB, tuberculosis; TST, tuberculin skin test.

TST-negative 7 months before being QFT-positive.

TST positive 1 year before QFT test.

Excluding the 7 children treated for active TB disease, 109 children initiated a LTBI regimen (data not shown). The remaining 976 (89%) children in the cohort were not treated for LTBI; 906 were QFT-negative, of which 96 were contacts and 686 were foreign-born, noncontacts (data not show) (Table 5). In addition, 26% of the untreated group comprised 46 children <2 years of age and 212 children ages 2–5.

Table 5.

QFT and TST Results in Untreated Children by Age and Years of Study Follow-up

| QFT Result | Total | Median Years of Follow-up (Range) | Age <2 | Median Years of Follow-up (Range) | Age 2 to <5 | Median Years of Follow-up (Range) | Age 5–14 | Median Years of Follow-up (Range) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 976 | 5.7 (4.7–6.6) | 46 | 5.8 (4.0–7.8) | 212 | 5.5 (4.0–7.8) | 718 | 5.7 (4.0–7.8) | |

| QFT-positive | 11 | 6.0 (4.5–6.8) | 0 | - | 1 | - | 10 | 5.9 (4.5–6.8) |

| TST-positive | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | ||||

| TST-negative | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| TST not done | 9 | 0 | 1 | 8 | ||||

| QFT-negative | 906 | 5.6 (4.0–7.8) | 37 | 6.0 (4.2–7.8) | 199 | 5.4 (4.0–7.8) | 670 | 5.6 (4.0–7.8) |

| TST-positive | 146 | 7 | 47 | 92 | ||||

| TST-negative | 19 | 2 | 5 | 12 | ||||

| TST not done | 741 | 28 | 147 | 566 | ||||

| QFT-indeterminate | 59 | 6.2 (4.0–7.8) | 9 | 5.3 (4.0–7.5) | 12 | 6.0 (4.5–7.3) | 38 | 6.6 (4.2–7.8) |

| TST-positive | 5 | 1 | 0 | 4 | ||||

| TST-negative | 14 | 3 | 5 | 6 | ||||

| TST not done | 40 | 5 | 7 | 28 |

Abbreviations: QFT, QuantiFERON; TST, tuberculin skin test.

Untreated children in the study cohort were observed for a median of 5.7 years (IQR, 4.7–6.6). During 5587 person-years of follow-up, no cases of active TB were identified in any untreated child, including the 146 TST-positive/QFT-negative children (8 of whom were contacts). There was minimal variation (<1 year) in follow-up time by age group, gender, race/ethnicity, foreign-born status, and test result. On average, noncontacts were observed for 1 year longer than contacts (5.8 vs 4.8 years [P < .0001]; data not shown) because more contacts were identified at the later part of study period.

Table 6 shows the estimated number of TB cases that would have developed in untreated TST-positive children if QFT had missed identifying LTBI. If all untreated TST-positive cases were truly infected with TB, at least 8–13 cases of TB disease would have been expected during the follow-up period. This includes 4 cases of TB disease in children <5 years of age.

Table 6.

Estimated Cases of TB Disease During Follow-up Period If LTBI Cases Had Been Missed

| Age | Untreated TST+/QFT− or Indeterminate (Contacts to Contagious TB Cases) | Lifetime Risk of Disease Following Missed/ Untreated LTBI* | Total Expected Cases of TB Disease If LTBI Missed/Left Untreated+ | If 90%** of Those Developing Disease Do So Within Available Follow-up Time+ | If 75% of Those Developing Disease Do So Within Available Follow-up Time | If 50%++ of Those Developing Disease Do So Within Available Follow-up Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 to <1 | 0 (1) | ~50% | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 to <2 | 3 (0) | ~20%-30% | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 to <5 | 47 (0) | ~5% | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| 5–10 | 0 (4) | ~2% | ||||

| 10 to <15 | 96 (2) | ~10%-20% | 4–9 | 4–8 | 3–7 | 2–5 |

| All ages | 146 | 8–13 | 8–12 | 7–11 | 5–8 |

Abbreviations: LTBI, latent tuberculosis infection; QFT, QuantiFERON; TB, tuberculosis; TST, tuberculin skin test.

Calculations are rounded down (if <0.5) or up (>0.5) for estimated cases.

Comprehensive reviews of the natural history of pediatric TB indicate that >90% of cases that progress to disease do so within the first year after primary infection [32].

In adults, 50% of TB infection that progresses to disease does so in the first 2 years after infection [30].

DISCUSSION

The San Francisco TB program’s experience represents the largest longitudinal retrospective pediatric cohort study with IGRAs in a low TB-prevalence setting to date [3, 4, 19, 26–28]. We observed the outcomes of 906 untreated QFT-negative children, including 146 who were TST-positive. The cohort was passively observed over 4–7 years and included children of varying risk for TB infection, including BCG-vaccinated immigrant children from countries of high-TB prevalence, contacts to active TB cases, and US-born children evaluated before entering school, thus reflecting the current spectrum of LTBI testing practices in the United States.

Longitudinal studies from pre-chemotherapy literature report the risk of progression to TB disease after primary infection was 50% in ages <1 and up to 20% in 1–2 and 10–15 year olds, and that >90% of cases that progress to disease do so within the first year after primary infection [1, 32]. If LTBI was missed by false-negative or indeterminate QFT results, particularly in children with discordant TST-positive results, we would have expected development of TB disease during the available follow-up time; however, no cases of disease occurred, strongly suggesting that the QFT has a high negative predictive value (NPV) for progression to active TB in the population studied. Likewise, studies by the Hamburg (Germany) Public Health Department and in Japanese school contact investigations reported no cases of active TB over several years of follow-up in untreated QFT-negative children [12, 33, 34].

In our cohort, TST-positive/QFT-negative discordance was substantial and consistent with current and past literature [14, 16–18]. In the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) preimmigration TST-QFT comparison study of 2530 immigrant children (age 2–14 years) from the Philippines, Vietnam, and Mexico, TST-positive/QFT-negative discordance was 85%, 84%, and 41%, respectively [35]. In San Francisco, discordance was most pronounced at 93% in foreign-born, BCG-vaccinated children <5 years old compared to 73% in those age ≥5 (P = .003). This finding suggests a higher rate of false-positive TST results when BCG vaccination is more recent, consistent with large studies showing the greatest TST reactivity in the 3–4 years after inoculation [6, 7, 36, 37]. Systematic use of TST in immigrant children inevitably leads to cases of inaccurately diagnosed LTBI and unnecessary radiologic studies and treatment. Furthermore, the discordant results of QFT with TST and the high NPV in this study provide strong support for the preferential use of IGRAs in routine screening of both BCG and non-BCG-vaccinated children <5.

QuantiFERON-positive results were markedly lower compared with historical TST-based rates among foreign-born children in San Francisco (24% from 2001 to 2004, San Francisco program data). Based on QFT, our study showed a 7% TB infection rate among foreign-born and BCG-vaccinated children and 3% for other US-born noncontacts. These findings are consistent with results from Howley et al [35], in which the percent positive QFT differed significantly from TST at 5.6% and 26%, respectively. Bacille Calmette-Guerin vaccination and NTM exposure confounds TST results and overestimates infection rates of foreign-born children. This has significant implications for program efficiency, patient safety due to unnecessary treatment, and programmatic and societal cost-effectiveness.

The benefit of preventing active TB cases by screening children requires a certain threshold rate of LTBI to be programmatically cost-effective; for the TST, this is estimated to be 10% [38]. San Francisco pediatric TB infection rates are below this estimated threshold despite following guidelines for risk-based targeted testing from the AAP, CDC, and the California Tuberculosis Controllers Association [30, 39, 40]. Universal TB testing as a school entrance requirement, or for all children at certain ages, continues in local communities in California. The low rates of TB infection found in this cohort of children who, for the most part, had at least 1 risk factor for TB infection emphasize the opportunity to eliminate universal TB testing in low-risk populations of children.

This analysis is subject to the following limitations. First, our longitudinal surveillance relied on a retrospective study design and passive methods of querying TB registries to identify subjects who subsequently developed active TB. Nevertheless, public health reporting of pediatric TB cases in San Francisco and California are unlikely to miss cases of active TB because a past analysis found that 99.7% of active TB cases were appropriately reported to the CDPH [41]. However, children who moved outside of California during the study period and developed active TB disease would not have been captured in the registry matches. Second, dual TST and QFT testing was performed on only a subset of patients; the observed discordant rates might not reflect the entire study population and general population of the United States. Third, children evaluated in this cohort were of varying risk for TB infection, which impacts QFT-positive rates and projected estimates for TB disease if LTBI had been missed. Fourth, we were unable to evaluate and compare QFT and TST testing practices directly; however, we believe our study population is representative of all children screened for TB in San Francisco. Finally, a lack of a microbiologically defined gold standard for LTBI, and difficulty in diagnosing TB in children, compromises all studies that aim to interpret and compare results of diagnostic testing methods for TB.

The San Francisco experience supports more generalized use of QFT in risk-based screening of pediatric patients for LTBI, including children <5 years of age and, in particular, those who are BCG-vaccinated. Our growing longitudinal experience indicates that QFT has an excellent NPV and may be used to reliably exclude LTBI in children. The enhanced specificity of QFT has reduced the number of children to whom we offer LTBI treatment, and it enabled us to focus limited resources on completing preventive treatment in the pediatric population. Overall, greater use of the IGRAs and more selective TB testing based on current epidemiology and risks assessments can prevent unnecessary radiographic imaging and treatment in many children and better utilize limited TB control resources. Our experience suggests the potential IGRAs may have in the pediatric primary care setting to effectively diagnosis LTBI. Use of IGRAs in this population could have implications for advancing TB elimination efforts in the United States.

Acknowledgments

We thank the TB program and laboratory staff.

Financial support.

This work was supported in part by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, TB Elimination, Laboratory Cooperative Agreement (5U52PS900454).

Potential conflicts of interest.

J. A. G. and L. M. K. received travel support from Qiagen during the study period for presentations on San Francisco’s programmatic IGRA implementation and QFT surveillance outcomes; S. I. received honoraria from Qiagen after the study period; L. M. K. did not begin employment with Qiagen until after the study period. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Marais BJ, Gie RP, Schaaf HS, et al. The natural history of childhood intra-thoracic tuberculosis: a critical review of literature from the pre-chemotherapy era. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2004; 8: 392–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newton SM, Brent AJ, Anderson S, et al. Paediatric tuberculosis. Lancet Infect Dis 2008; 8:498–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lighter J, Rigaud M. Diagnosing childhood tuberculosis: traditional and innovative modalities. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 2009; 39:61–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewinsohn DA, Lobato MN, Jereb JA. Interferon-gamma release assays: new diagnostic tests for Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection, and their use in children. Curr Opin Pediatr 2010; 22: 71–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huebner RE, Schein MF, Bass JB. The tuberculin skin test. Clin Infect Dis 1993; 17:968–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farhat M, Greenaway C, Pai M, Menzies D. False-positive tuberculin skin tests: what is the absolute effect of BCG and nontuberculous mycobacteria? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2006; 10: 1192–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Piñeiro R, Mellado MJ, Cilleruelo MJ, et al. Tuberculin skin test in bacille Calmette-Guérin-vaccinated children: how should we interpret the results? Eur J Pediatr 2012; 171:1625–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riazi S, Zeligs B, Yeager H, et al. Rapid diagnosis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in children using interferon-gamma release assays (IGRAs). Allergy Asthma Proc 2012; 33:217–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Starke JR. Interferon-gamma release assays for diagnosis of tuberculosis infection in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2006; 25:941–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arend SM, Thijsen SF, Leyten EM, et al. Comparison of two interferon-gamma assays and tuberculin skin test for tracing tuberculosis contacts. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007; 175: 618–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diel R, Loddenkemper R, Meywald-Walter K, et al. Predictive value of a whole blood IFN-gamma assay for the development of active tuberculosis disease after recent infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008; 177:1164–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diel R, Loddenkemper R, Niemann S, et al. Negative and positive predictive value of a whole-blood interferon-γ release assay for developing active tuberculosis: an update. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011; 183:88–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pai M, Zwerling A, Menzies D. Systematic review: T-cell-based assays for the diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection: an update. Ann Intern Med 2008; 149:177–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lighter J, Rigaud M, Eduardo R, et al. Latent tuberculosis diagnosis in children by using the QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube test. Pediatrics 2009; 123:30–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Detjen AK, Keil T, Roll S, et al. Interferon-gamma release assays improve the diagnosis of tuberculosis and nontuberculous myco-bacterial disease in children in a country with a low incidence of tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 45:322–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cruz AT, Geltemeyer AM, Starke JR, et al. Comparing the tuberculin skin test and T-SPOT.TB blood test in children. Pediatrics 2011; 127:e31–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bianchi L, Galli L, Moriondo M, et al. Interferon-gamma release assay improves the diagnosis of tuberculosis in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2009; 28:510–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Machingaidze S, Wiysonge CS, Gonzalez-Angulo Y, et al. The utility of an interferon gamma release assay for diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection and disease in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2011; 30: 694–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ling DI, Zwerling AA, Steingart KR, Pai M. Immune-based diagnostics for TB in children: what is the evidence? Paediatr Respir Rev 2011; 12:9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Committee on Infectious Diseases. Tuberculosis. In Pickering LK, ed. Red Book: 2012 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2012: pp. 736–59. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shah M, DiPietro D, Greenbaum A, et al. Programmatic impact of QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube implementation on latent tuberculosis diagnosis and treatment in a public health clinic. PLoS One 2012; 7:e36551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Critselis E, Amanatidou V, Syridou G, et al. The effect of age on whole blood interferon-gamma release assay response among children investigated for latent tuberculosis infection. J Pediatr 2012; 161:632–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Basu Roy R, Sotgiu G, Altet-Gómez N, et al. Identifying predictors of interferon-γ release assay results in pediatric latent tuberculosis: a protective role of bacillus Calmette-Guerin? A pTB-NET collaborative study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012; 186:378–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pavić I, Topić RZ, Raos M, et al. Interferon-γ release assay for the diagnosis of latent tuberculosis in children younger than 5 years of age. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2011; 30:866–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haustein T, Ridout DA, Hartley JC, et al. The likelihood of an indeterminate test result from a whole-blood interferon-gamma release assay for the diagnosis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in children correlates with age and immune status. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2009; 28:669–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lewinsohn DA. Embracing interferon-gamma release assays for diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2009; 28:674–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Powell DA. Interferon gamma release assays in the evaluation of children with possible Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection: a view to caution. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2009; 28:676–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Connell TG, Tebruegge M, Ritz N, et al. The potential danger of a solely interferon-gamma release assay-based approach to testing for latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in children. Thorax 2011; 66:263–4; author reply 265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reported Tuberculosis in the United States, 2012. MMWR 2013; 62:201–5.23515056 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Targeted tuberculin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. American Thoracic Society. MMWR Recomm Rep 2000; 49(RR-6):1–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mazurek GH, Jereb J, Vernon A, et al. Updated guidelines for using interferon gamma release assays to detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection - United States, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep 2010; 59(RR-5):1–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marais BJ, Perez-Velez CM. Tuberculosis in children. N Engl J Med 2012; 367:348–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Higuchi K, Harada N, Mori T, Sekiya Y. Use of QuantiFERON-TB Gold to investigate tuberculosis contacts in a high school. Respirology 2007; 12:88–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Higuchi K, Kondo S, Wada M, et al. Contact investigation in a primary school using a whole blood interferon-gamma assay. J Infect 2009; 58:352–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Howley MM, Painter JA, Katz DJ, et al. Evaluation of QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube and tuberculin skin tests among immigrant children being screened for latent tuberculosis infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2014; doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reid JK, Ward H, Marciniuk D, et al. The effect of neonatal bacille Calmette-Guérin vaccination on purified protein derivative skin test results in Canadian aboriginal children. Chest 2007; 131:1806–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chan PC, Chang LY, Wu YC, et al. Age-specific cut-offs for the tuberculin skin test to detect latent tuberculosis in BCG-vaccinated children. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2008; 12:1401–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Flaherman VJ, Porco TC, Marseille E, Royce SE. Cost-effectiveness of alternative strategies for tuberculosis screening before kindergarten entry. Pediatrics 2007; 120:90–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pediatric Tuberculosis Collaborative Group. Targeted tuberculin skin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2004; 114(Supplement 4): 1175–201. [Google Scholar]

- 40.California Tuberculosis Controllers Association. CTCA Position of TB Testing of School-Age Children. Available at: http://ctca.org/fileLibrary/file_370.pdf. Accessed April 1, 2014.

- 41.Curtis AB, McCray E, McKenna M, Onorato IM. Completeness and timeliness of tuberculosis case reporting. A multistate study. Am J Prev Med 2001; 20:108–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]