Abstract

(6R)-2,2,6-Trimethyl-1,4-cyclohexanedione (levodione) reductase was isolated from a cell extract of the soil isolate Corynebacterium aquaticum M-13. This enzyme catalyzed regio- and stereoselective reduction of levodione to (4R,6R)-4-hydroxy-2,2,6-trimethylcyclohexanone (actinol). The relative molecular mass of the enzyme was estimated to be 142,000 Da by high-performance gel permeation chromatography and 36,000 Da by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The enzyme required NAD+ or NADH as a cofactor, and it catalyzed reversible oxidoreduction between actinol and levodione. The enzyme was highly activated by monovalent cations, such as K+, Na+, and NH4+. The NH2-terminal and partial amino acid sequences of the enzyme showed that it belongs to the short-chain alcohol dehydrogenase/reductase family. This is the first report of levodione reductase.

Optically active hydroxy cyclohexanone derivatives, such as (4R,6R)-4-hydroxy-2,2,6-trimethylcyclohexanone (actinol), are useful chiral building blocks of naturally occurring optically active compounds, such as xanthoxin (3) and zeaxanthin (11).

Microbial production of actinol from 2,2,6-trimethylcyclohexanedione has been demonstrated previously by Nishii et al. (15, 16), because actinol is the key intermediate in zeaxanthin formation. However, in this case, a racemic mixture of 4-hydroxy-2,2,6-trimethylcyclohexanones was obtained as the reduction product; this mixture contained (4R,6S)-, (4S,6R)-, (4R,6R)-, and (4S,6S)-4-hydroxy-2,2,6-trimethylcyclohexanones at a quantitative ratio of 68:25:5:2, and actinol accounted for only 5% of the total isomer content. Moreover, the enzyme involved in reduction of 2,2,6-trimethylcyclohexanedione has not been purified yet.

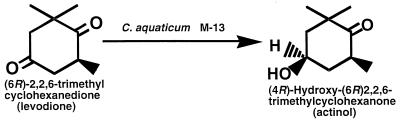

We screened the microorganisms that can catalyze stereo- and regioselective reduction of the carbonyl group at the C-4 position of levodione and found that the soil isolate Corynebacterium aquaticum M-13 was the best producer of the enzyme under the conditions tested. The enzyme produced actinol with a 95% enantiomeric excess as the reduction product (Fig. 1). We describe here purification and characterization of this levodione reductase from C. aquaticum M-13, which we found to be a novel, monovalent cation-activated enzyme.

FIG. 1.

Conversion of (6R)-2,2,6-trimethyl-1,4-cyclohexanedione to (4R,6R)-4-hydroxy-2,2,6-trimethylcyclohexanone by C. aquaticum M-13.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microorganisms and cultivation.

Microorganisms preserved in the AKU Culture Collection (Faculty of Agriculture, Kyoto University) and soil isolates which can grow on a medium containing 1,4-cyclohexanedione as the sole carbon source were subjected to screening. The strains were cultivated aerobically at 30°C for 20 h in a medium (pH 7.0) containing 1% glucose, 1.5% peptone, 0.3% K2HPO4, 0.1% yeast extract, 0.2% NaCl, and 0.02% MgSO4 · 7H2O.

Chemicals.

Levodione and actinol were prepared as described previously (11, 15). 3,5,5-Trimethyl-2-cyclohexene-1,4-dione (ketoisophrone) and dihydro-3-oxo-4,4-dimethyl-2-furanone (ketopantoyl lactone) were synthesized as described previously (11, 20). 2,3-Pentanedione and 1-phenyl-1,2-propanedione were purchased from Wako Pure Chemicals (Osaka, Japan) and Tokyo Kasei Industries (Tokyo, Japan), respectively. All other chemicals used in this study were of analytical grade and were commercially available.

Screening of levodione-reducing strains.

Washed cells of each microorganism obtained from 5 ml of culture broth were incubated in 1 ml of reaction mixture containing 100 μmol of potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 904 nmol of NAD+, 784 nmol of NADP+, 14.3 U of glucose dehydrogenase (Amano Pharmaceutical, Nagoya, Japan), 278 mmol of glucose, and 32.5 nmol of levodione. The reaction mixture was incubated at 30°C for 18 h with shaking, and then the mixture was vigorously shaken with 1 ml of ethyl acetate. The ethyl acetate layer was analyzed to determine its levodione and actinol contents by gas chromatography (GC) as described below.

Analysis of levodione and actinol.

Quantitative analysis of the levodione and actinol contents was performed with a Shimadzu model GC-14B GC equipped with a flame ionization detector by using a type HR-20M capillary column (0.25 mm by 30 m; Shinwa Chemical Industries, Kyoto, Japan) at 160°C (isothermal) and He as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. Under these conditions, levodione, actinol, and (4S,6R)-hydroxy-2,2,6-trimethylcyclohexanone (a diastercomer of actinol) eluted at 6.8, 15.6, and 15.9 min, respectively.

Enzymatic preparation of actinol.

Enzymatic reduction of levodione was carried out as follows. A 3.3-ml reaction mixture containing 830 μmol of potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 1.5 U of the enzyme, and 130 μmol of NADH was incubated at 30°C. At 5-min intervals for 30 min, 5 μmol of levodione was added. After 30 min of incubation, the reaction mixture was extracted with 2 ml of ethyl acetate, and the ethyl acetate layer was concentrated. The concentrated ethyl acetate layer was analyzed by GC under the conditions described above.

Enzyme assay.

Enzyme activity was determined by spectrophotometrically measuring the levodione-dependent decrease in the NADH content. The standard 2.5-ml assay mixture contained 5 μmol of levodione (final concentration, 2.0 mM), 0.80 μmol of NADH, 500 μmol of potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), and the enzyme. One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that catalyzed oxidation of 1 μmol of NADH per min.

When the effect of monovalent cations was measured, the potassium phosphate buffer was replaced by an equimolar concentration of Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4).

Kinetic studies.

Steady-state kinetic studies were performed in 100 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4). When the apparent Km value for levodione was determined, the levodione concentration was varied from 2.0 to 20 mM in the presence of a fixed concentration of NADH (320 μM). When the apparent Km value for NADH was determined, the NADH concentration was varied from 40 to 320 μM in the presence of a fixed concentration of levodione (10 mM).

The kinetic parameters of the reverse reaction were also determined with same substrate concentrations.

Purification of the enzyme.

All purification procedures were performed at 0 to 4°C in 10 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing 0.1 mM dithiothreitol, unless otherwise specified.

The washed cells (wet weight, 60 g) isolated from 8 liters of culture broth were suspended in 180 ml of the buffer and then disrupted with an ultrasonic oscillator for 60 min. After centrifugation, the resulting supernatant was fractionated with solid ammonium sulfate. The precipitate obtained with 40 to 60% saturation was collected, dialyzed against 10 liters of the buffer for 18 h, and applied to a DEAE-Sepharose FF (Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden) column (3.0 by 20 cm) equilibrated with the buffer. The enzyme was eluted with a linear 0 to 1.0 M NaCl gradient in 660 ml of the buffer at a flow rate of 2.0 ml/min. The enzyme eluted at approximately 0.28 M NaCl in the buffer.

The concentration of (NH4)2SO4 was adjusted to 2 M by adding solid (NH4)2SO4 to the enzyme solution before the enzyme solution was loaded onto an Alkyl Superose HR10/10 (Pharmacia Biotech) column (1.0 by 10 cm) that was connected to a fast protein liquid chromatography system (Pharmacia Biotech) and previously had been equilibrated with the buffer containing 2 M (NH4)2SO4. The enzyme was eluted with a linear 2 to 0 M (NH4)2SO4 gradient in 230 ml of the buffer at a flow rate of 0.8 ml/min. The activity-containing fractions, which eluted at approximately 1.5 M (NH4)2SO4 in the buffer, were pooled and dialyzed against 3 liters of the buffer for 8 h.

The enzyme solution was applied to a MonoQ HR5/5 column (0.5 by 5 cm) that was connected to a fast protein liquid chromatography system and previously had been equilibrated with the buffer. The enzyme was eluted with a linear 0 to 0.8 M NaCl gradient in 35 ml of the buffer at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. The activity-containing fractions, which eluted at approximately 0.4 M NaCl in the buffer, were collected and used as the purified enzyme for characterization.

Lysyl endopeptidase digestion and isolation of the peptides.

The purified enzyme was digested with lysyl endopeptidase (Wako Pure Chemicals, Osaka, Japan) under the conditions described previously (10). The peptides were separated by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography on a μRPC C2/C18 column (Pharmacia Biotech) connected to a Smart system (microscale protein purification system; Pharmacia Biotech). The peptides were eluted with a linear 0 to 80% acetonitrile gradient containing 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid.

Amino acid sequence analysis.

A partial amino acid sequence was determined with a model 476A pulsed liquid protein sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) as described previously (22). The partial amino acid sequence obtained was compared with the sequences of proteins stored in the SWISS-PROT (release 37.0+/06-14, June 99), PIR (release 60.0, March 99), and PRF (release 99-05, May 99) protein databases. Sequence alignment was performed by using the Blast (1) and Fasta (18) programs.

Other methods.

The molecular mass of the enzyme and protein concentrations were determined as described previously (22).

RESULTS

Screening of levodione-reducing strains.

Levodione-reducing activity was widely distributed in various microorganisms. As shown in Table 1, bacteria belonging to the genera Corynebacterium, Cellulomonas, and Arthrobacter catalyzed stereoselective reduction of levodione and gave actinol as a reduction product. One strain, C. aquaticum M-13, was selected as the best producer of the enzyme that catalyzes the stereoselective reduction of levodione to actinol under the conditions tested.

TABLE 1.

Screening of the levodione-reducing microorganisms

| Strain | Yield (%)a | Enantiomeric excess for actinol (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Corynebacterium aquaticum M-7 | 93.7 | 85.9 |

| Corynebacterium aquaticum M-13 | 97.4 | 87.7 |

| Micrococcus sp. strain AKU510 | 100 | 50 |

| Flavobacterium okeanokoites AKU152 | 42.3 | 56.7 |

| Arthrobacter sulfureus AKU635 | 64 | 44 |

| Cellulomonas cellulans AKU672 | 73 | 78.3 |

| Saccharomyces dairensis AKU4127 | 41.9 | <−95.0 |

| Candida maltosa AKU4624 | 50.6 | −92.4 |

Yield for actinol plus (4S,6R)-4-hydroxy-2,2,6-trimethylcyclohexanone.

Purification of the enzyme.

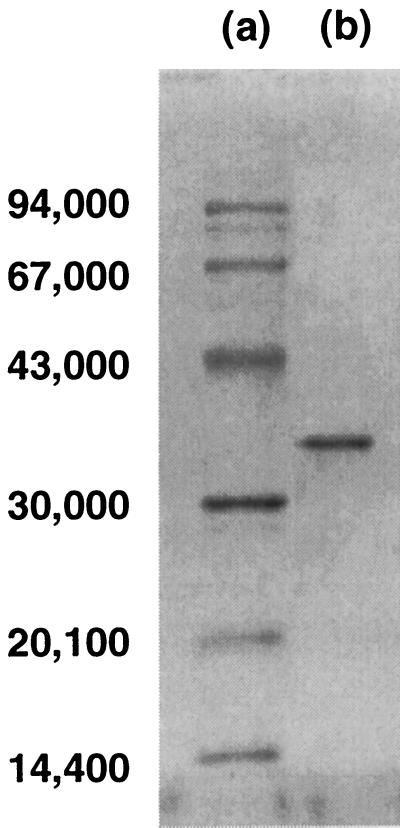

The enzyme activity of the cell extract was too low to determine the specific activity; however, after ammonium sulfate precipitation, the enzyme activity seemed to increase, which allowed quantitative measurement. The method used for purification of levodione reductase is summarized in Table 2. The enzyme was purified to homogeneity, and the overall level of recovery was 10.7%. The purified enzyme produced a single band on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gels (Fig. 2).

TABLE 2.

Purification of the levodione reductase from C. aquaticum M-13

| Step | Total protein (mg) | Total activity (U) | Sp act (U/mg) | Yield (%) | Purification (fold) | Enantiomeric excess for (4R,6R) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell extract | 3,680 | 89.0 | ||||

| 40–60% (NH4)2SO4 precipitation | 504 | 54.0 | 0.110 | 100 | 1 | 95.1 |

| DEAE-Sephacel | 39.2 | 30.0 | 0.770 | 55.6 | 7.00 | 94.9 |

| Alkyl Superose HR10/10 | 2.88 | 28.0 | 9.72 | 51.9 | 88.4 | 95.0 |

| MonoQHR5/5 | 0.280 | 5.80 | 20.7 | 10.7 | 188 | 95.0 |

FIG. 2.

SDS-PAGE of the levodione reductase from C. aquaticum M-13. Lane a, Mr standards, including (from top to bottom) phosphorylase b (Mr, 94,000), bovine serum albumin (67,000), ovalbumin (43,000), carbonic anhydrase (30,000), trypsin inhibitor (20,100), and α-lactalbumin (14,400); lane b, purified enzyme (4 μg). The gel was stained for protein with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250 and was destained in methanol-acetic acid-water (7:6:47).

Relative molecular mass and subunit structure.

Using a calibrated column of Superdex-200 PC3.2/30 (Pharmacia Biotech), we estimated that the relative molecular mass of the enzyme was 155,000 Da, while the molecular mass determined by high-performance gel permeation chromatography performed with a Cosmosil 5Diol-300 column (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan) was about 142,000 Da. The relative molecular mass of each subunit was estimated to be approximately 36,000 Da by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 2). These results suggest that the enzyme is a tetramer.

Stereoselectivity for levodione reduction.

Using levodione as the substrate, we analyzed the optical purity of the reduction product by GC. The actinol formed by the enzyme was the (4R,6R) enantiomer with 95.0% enantiomeric excess.

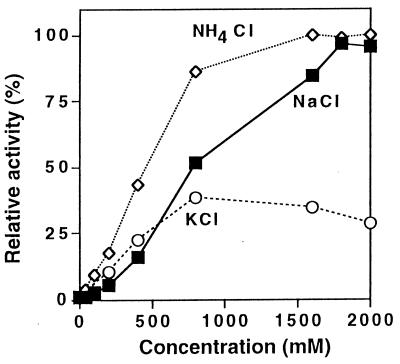

Effect of monovalent cations on enzyme activity.

The purified enzyme eluted from the MonoQ HR5/5 column, which contained approximately 400 mM NaCl, had a specific activity of 20.7 U/mg. However, the specific activity of the enzyme decreased to 0.69 U/mg after overnight dialysis against 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4) supplemented with 0.1 mM dithiothreitol.

The activity of the dialyzed enzyme was restored when a monovalent cation, such as NH4+, Na+, Cs+, K+, and Rb+, was added to the reaction mixture. Activation by the monovalent cations K+, Na+, and NH4+ is shown in Fig. 3.

FIG. 3.

Effects of K+ (○), Na+ (■), and NH4+ (◊) on enzyme activity. Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) was used as the buffer, and the enzyme activity with 2 M NH4+ was defined as 100%. Chloride was used as the anion in all mixtures.

Substrate specificity and catalytic properties.

The substrate specificity of the levodione reductase of C. aquaticum M-13 is shown in Table 3. Some cyclic ketones, including ketoisophorone and ketopantoyl lactone, and some vicinal diketones, including 2,3-pentanedione and 1-phenyl-1,2-propanedione, were reduced by this enzyme in addition to levodione. However, other cyclic ketones, including isophrone, cyclohexanone, cyclopentanone, and 1,4-cyclohexanedione, and some typical substrates for aldo-keto reductase, such as p-nitrobenzaldehyde and pyridine-3-aldehyde, were not reduced. Normal hyperbolic kinetics were observed with levodione. The apparent Km and Vmax values under the conditions described above, both in the presence and in the absence of KCl, as calculated from Lineweaver-Burk plots, are shown in Table 4.

TABLE 3.

Substrate specificity of the levodione reductase from C. aquaticum M-13

| Substrate | Concn (mM) | Relative activity (%)a |

|---|---|---|

| Levodione | 2 | 100 |

| Ketoisophorone | 2 | 31.8 |

| Ketopantoyl lactone | 2 | 12.7 |

| 2,3-Pentanedione | 10 | 11.6 |

| 1-Phenyl-1,2-propanedione | 10 | 7.9 |

The enzyme activity with 2 mM levodione was defined as 100%.

TABLE 4.

Apparent kinetic constants for levodione reductasea

| Salt | Km (mM) | Vmax (U/mg) | Vmax/Km |

|---|---|---|---|

| None | 11.3 ± 1.8 | 18.2 ± 2.2 | 1.61 ± 0.2 |

| 1 M KCl | 3.00 ± 0.5 | 125 ± 15 | 41.7 ± 0.6 |

The dialyzed enzyme was used. The enzyme activity was measured in Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4) with and without 1 M KCl. The kinetic constant values are averages ± standard deviations resulting from three different determinations.

The enzyme was very specific for NADH as a coenzyme; when the levodione concentration was 2 mM, the apparent Km value for NADH was 154 μM, and no decrease was observed at 340 nm due to reduction of levodione when NADH was replaced by an equimolar concentration of NADPH.

The reversibility of the reaction was investigated by using actinol and NAD+ at concentrations of 2.0 and 0.32 mM, respectively. We observed an increase in the absorbance at 340 nm due to oxidation of actinol. When the ethyl acetate extract of the reaction mixture obtained after oxidation was examined by GC, a peak corresponding to the levodione peak was observed. Thus, the enzyme catalyzed a reversible reaction between levodione and actinol. The apparent Km and Vmax values with 320 μM NAD+ in the presence of 1 M KCl for actinol oxidation were 1.36 ± 0.25 mM and 15.9 ± 1.2 μmol/min/mg of protein, respectively.

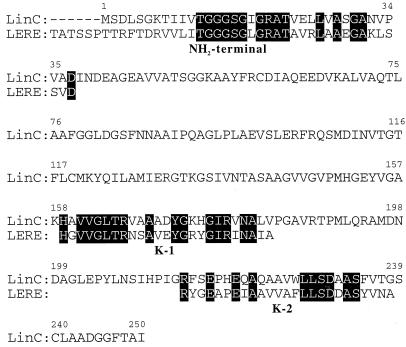

Partial amino acid sequence analysis.

The NH2-terminal amino acid sequence of the enzyme was determined by automated Edman degradation by using a pulsed liquid phase sequencer (Fig. 4). This sequence was found to be similar to the NH2-terminal amino acid sequences of the short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase (SDR) family (4, 19) proteins, such as biphenyl-2,3-dihydro-2,3-diol dehydrogenase of Pseudomonas sp. strain KKS102 (7), cis-1,2-dihydrobenzene-1,2-diol dehydrogenase of Pseudomonas putida (9), cis-toluene dihydrodiol dehydrogenase of P. putida F1 (24), and 2,5-dichloro-2,5-cyclohexadiene-1,4-diol dehydrogenase of Sphingomonas paucimobilis (14), which belong to the SDR family (4, 19). Moreover, this NH2-terminal amino acid sequence contains G-X-X-X-G-X-G, which is highly conserved in the NH2-terminal regions of SDR family proteins (19). These results strongly suggest that the enzyme purified in this study belongs to the SDR family.

FIG. 4.

Comparison of the NH2-terminal and internal (K-1 and K-2) amino acid sequences of the levodione reductase of C. aquaticum M-13 (LERE) with the amino acid sequences of 2,5-dichloro-2,5-cyclohexadiene-1,4-diol dehydrogenase of S. paucimobilis (13) (LinC).

The enzyme protein was digested with lysyl endopeptidase, and the resulting digest was separated by the Smart system. Three peptides (K-1, K-2, and K-3) were isolated, and the amino acid sequences of these peptides were analyzed with a protein sequencer. The K-1 and K-2 sequences are shown in Fig. 4, and the K-3 sequence was A-A-V-L-E-T-A-P-D-A-E-V-L-T-T. When these sequences were compared with the sequences in three protein sequence databases (PIR, PRF, and SWISS-PROT) by using the sequence similarity search programs Blast (1) and Fasta (18), the K-1 and K-2 sequences were found to be significantly similar to partial amino acid sequences of 2,5-dichloro-2,5-cyclohexadiene-1,4-diol dehydrogenase of S. paucimobilis (14) and 3-oxoacyl-[acyl-carrier protein] reductase of Haemophilus influenzae (6), respectively, both of which belong to the SDR family. However, K-3 did not exhibit significant similarity to any other SDR family protein. Overall, the partial amino acid sequence of this enzyme exhibited the greatest similarity to the sequence of 2,5-dichloro-2,5-cyclohexadiene-1,4-diol dehydrogenase of S. paucimobilis (14). A sequence alignment is shown in Fig. 4.

Spectral properties.

The absorption spectrum of the enzyme had a maximum at 278 nm. No absorbance was detected at wavelengths greater than 320 nm. Thus, the enzyme does not contain flavin or pyrroloquinoline quinone, which are the coenzymes present in most quinone reductases (5) and in quinoprotein dehydrogenase (2).

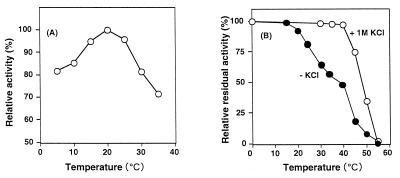

Effects of temperature on enzyme activity and stability.

As shown in Fig. 5A, the optimum temperature for levodione reduction was determined to be 20°C at pH 7.0. Although the dialyzed enzyme was stable at temperatures below 15°C for 10 min at pH 7.0, in the presence of 1 M KCl the enzyme was stable at temperatures below 40°C for 10 min at pH 7.0 (Fig. 5B). At 55°C, all of the initial enzyme activity was lost under both conditions.

FIG. 5.

Effects of temperature on enzyme activity (A) and stability (B). (A) Activity of the enzyme was measured at various temperatures from 20 to 60°C at pH 7.0. Relative activity is expressed as percentages of the maximum activity under the experimental conditions. (B) Enzyme (30 μg), in a total volume of 1.0 ml, was incubated in 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4) containing 0.1 mM dithiothreitol at various temperatures for 10 min in the presence (○) or absence (●) of KCl. The residual activity was measured under the standard assay conditions.

DISCUSSION

Levodione-reducing microorganisms have been described in previous papers (15, 16); however, levodione reductase was not purified previously. To our knowledge, this is the first report concerning levodione reductase.

Judging from the substrate specificity (Table 3), a diketone structure seems to be necessary in order for a compound to be transformed by levodione reductase. However, the physiological substrate of this enzyme is still unknown.

This enzyme was activated by monovalent cations, such as K+, Na+, and NH4+, as are the glycerol dehydrogenases of Escherichia coli (21), Aerobacter aerogenes (12), and Cellulomonas sp. (17, 23). These glycerol dehydrogenases exhibit maximum activity at monovalent cation concentrations of 0.7 to 40 mM, although the enzyme purified in our experiment exhibited maximum activity in the presence of 1.5 to 2.0 M NH4Cl and 1.8 to 2.0 M NaCl. Oxidoreductases, which exhibit maximum activity at extremely high salt concentrations, have been found in some halophilic bacteria, such as Halobacterium salinarium and Halobacterium cutirubrum (8). However, C. aquaticum M-13 is not a halophilic bacterium and scarcely grows in the presence of 1 M KCl.

The partial amino acid sequence of the enzyme was similar to the partial amino acid sequences of other SDR family enzymes (4, 19). This result suggests that the enzyme which we purified belongs to the SDR family. Although the NH2-terminal amino acid sequence of levodione reductase exhibited significant similarity to the sequence of cis-benzene glycol dehydrogenase of P. putida, the former enzyme cannot oxidize cis-benzene glycol at a concentration of 2.0 mM. Glucose dehydrogenases from Bacillus megaterium IAM1030 have been shown to be SDR enzymes and also have been reported to be stabilized in the presence of 2 M NaCl (13), and one of the glucose dehydrogenase isozymes, GlcDH-III, has been reported to be activated by 2 M NaCl. However, the effects of other monovalent cations, such as NH4+ and K+, and kinetic parameters with and without NaCl have not been reported. To our knowledge, we found the first example of an SDR family enzyme which is clearly activated by monovalent cations.

C. aquaticum M-13 can grow on a medium containing 1,4-cyclohexanedione as the sole carbon source. However, the levodione reductase purified in this study could not reduce 1,4-cyclohexanedione. Thus, we suggest that in C. aquaticum M-13 cells 1,4-cyclohexanedione is not degraded through a pathway initiated by a reductase. This compound may be degraded, for example, by a ring cleavage reaction; however, the fate of 1,4-cyclohexanedione in C. aquaticum M-13 is still unclear. Levodione reductase seemed to be useful for production of optically active actinol; however, the physiological role of this enzyme remains to be clarified.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Michihiko Kataoka for analyzing the NH2-terminal amino acid sequence.

This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research 6382 (to M.W) and 10356004 (to S.S.) from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan and by Research for the Future Program grant JSPS-RFTF 97I00302 to S.S. from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anthony C, Ghosh M. The structure and function of the PQQ-containing quinoprotein dehydrogenases. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 1998;69:1–21. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(97)00020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burden R S, Taylor H F. The structure and chemical transformation of xanthoxin. Tetrahedron Lett. 1970;47:4071–4074. doi: 10.1016/s0040-4039(01)98668-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Danielsson O, Atrian S, Luque T, Hjelmqvist L, Gonzalez-Duarte R, Jörnvall K. Fundamental molecular differences between alcohol dehydrogenase classes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4980–4984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ernster L. DT diaphorase. Methods Enzymol. 1967;10:309–317. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fleischmann R D, Adams M D, Rebecca A C, Kirkness E F, Kerlavage A R, Bult C J, Tomb J-F, Dougherty B A, Merrick J M, McKenney K, Sutton G, Fitzhugh W, Fields C, Gocayne J D, Scott J, Shirley R, et al. Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Science. 1995;269:496–512. doi: 10.1126/science.7542800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fukuda M, Yasukochi Y, Kikuchi Y, Nagata Y, Kimbara K, Horiuchi H, Takagi M, Yano K. Identification of the bphA and bphB genes of Pseudomonas sp. strain KKS102 involved in degradation of biphenyl and polychlorinated biphenyls. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;202:850–856. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hochsten L I. Studies of a halophilic NADH dehydrogenase. II. Kinetic properties of the enzyme in relation to salt activation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1975;403:58–66. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(75)90008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Irie S, Doi S, Yorifuji T, Takagi M, Yano K. Nucleotide sequencing and characterization of the genes encoding benzene oxidation enzymes of Pseudomonas putida. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:5174–5179. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.11.5174-5179.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kita K, Matuzaki K, Hashimoto T, Yanase H, Kato N, Chung M C-H, Kataoka M, Shimizu S. Cloning of the aldehyde reductase gene from red yeast, Sporobolomyces salmonicolor, and characterization of the gene and its product. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:2303–2310. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.7.2303-2310.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leuenberger H G W, Boguth W, Widmer E, Zell R. Synthesis of optically active natural carotenoids and structurally related compounds. I. Synthesis of chiral key compound (4R,6R)-4-hydroxy-2,2,6-trimethylcyclohexanone. Helv Chim Acta. 1976;59:1832–1849. [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGregor W G, Phillips J, Suelter C H. Purification and kinetic characterization of a monovalent cation-activated glycerol dehydrogenase from Aerobacter aerogenes. J Biol Chem. 1974;249:3132–3139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagao T, Mitamura T, Wang X H, Negoro S, Yomo T, Urabe I, Okada H. Cloning, nucleotide sequences, and enzymatic properties of glucose dehydrogenase isozymes from Bacillus megaterium IAM1030. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5013–5020. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.15.5013-5020.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagata Y, Ohtomo R, Miyauchi K, Fukuda M, Yano K, Takagi M. Cloning and sequencing of a 2,5-dichloro-2,5-cyclohexadiene-1,4-diol dehydrogenase gene involved in the degradation of γ-hexachlorocyclohexane in Pseudomonas paucimobilis. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:3117–3125. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.11.3117-3125.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nishi K, Sode K, Karube I. Microbial conversion of dihydrooxoisophorone (DOIP) to 4-hydroxy-2,2,6-trimethylcyclohexanone (4- HTMCH) by thermophilic bacteria. J Biotechnol. 1989;9:117–128. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishi K, Sode K, Karube I. Sequential two-step conversion of 4-oxoisophorone to 4-hydroxy-2,2,6-trimethylcyclohexanone by thermophilic bacteria. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1990;33:245–250. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nishise H, Nagao A, Tani Y, Yamada H. Further characterization of glycerol dehydrogenase from Cellulomonas sp. NT3060. Agric Biol Chem. 1984;448:1603–1609. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pearson W R, Lipman D J. Improved tools for biological sequence comparison. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:2444–2448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.8.2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reid M F, Fewson C A. Molecular characterization of microbial alcohol dehydrogenases. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1994;20:13–56. doi: 10.3109/10408419409113545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shimizu S, Yamada H, Hata H, Morishita T, Akutsu S, Kawamura M. Novel chemoenzymatic synthesis of d(−)-pantoyl lactone. Agric Biol Chem. 1987;51:289–290. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tang C-T, Ruch F E, Jr, Lin E C C. Purification and properties of a nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide-linked dehydrogenese that serves an Escherichia coli mutant for glycerol catabolism. J Bacteriol. 1979;140:182–187. doi: 10.1128/jb.140.1.182-187.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wada M, Kataoka M, Kawabata H, Yasohara Y, Kizaki N, Hasegawa J, Shimizu S. Purification and characterization of NADH-dependent carbonyl reductase, involved in stereoselective reduction of ethyl 4-chloro-3-oxobutanoate, from Candida magnoliae. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1998;62:280–285. doi: 10.1271/bbb.62.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamada H, Nagao A, Nishise H, Tani Y. Glycerol dehydrogenase from Cellulomonas sp. NT3060: purification and characterization. Agric Biol Chem. 1982;46:2333–2339. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zylstra G J, Gibson D T. Toluene degradation by Pseudomonas putida F1, nucleotide sequencing of the todC1C2BADE genes and their expression in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:14940–14946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]