Abstract

We evaluated the specificity and sensitivity of 11 previously described species differentiation and genotyping PCR protocols for detection of Cryptosporidium parasites. Genomic DNA from three species of Cryptosporidium parasites (genotype 1 and genotype 2 of C. parvum, C. muris, and C. serpentis), two Eimeria species (E. neischulzi and E. papillata), and Giardia duodenalis were used to evaluate the specificity of primers. Furthermore, the sensitivity of the genotyping primers was tested by using genomic DNA isolated from known numbers of oocysts obtained from a genotype 2 C. parvum isolate. PCR amplification was repeated at least three times with all of the primer pairs. Of the 11 protocols studied, 10 amplified C. parvum genotypes 1 and 2, and the expected fragment sizes were obtained. Our results indicate that two species-differentiating protocols are not Cryptosporidium specific, as the primers used in these protocols also amplified the DNA of Eimeria species. The sensitivity studies revealed that two nested PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) protocols based on the small-subunit rRNA and dihydrofolate reductase genes are more sensitive than single-round PCR or PCR-RFLP protocols.

Cryptosporidium parasites infect the microvillus border of the gastrointestinal epithelium of a wide range of vertebrate hosts, including humans. To date, at least 21 Cryptosporidium species have been named (20). However, only six to eight species (Cryptosporidium parvum, C. muris, C. wrairi, C. felis, C. meleagridis, C. baileyi, C. serpentis, and C. nasorum) are considered valid by most researchers (9, 20). C. parvum is the species that infects immunocompetent humans and most mammals. Cross-transmission studies performed with various mammals have suggested the possibility that zoonotic transmission of C. parvum to humans occurs (13, 20, 24). However, person-to-person transmission of this parasite has also been demonstrated (2, 8). In recent years, C. parvum has been reported to cause waterborne disease outbreaks worldwide (25).

Workers have described many PCR-based protocols for detection of Cryptosporidium parasites. The primers of these PCR protocols are based on undefined genomic sequences (14, 18, 29) or specific genes (2, 4, 12, 15). PCR methods have been shown to be more sensitive and specific than traditional microscopic techniques for detecting Cryptosporidium spp. in clinical and environmental samples (16, 19). Recently, workers have compared the performance of some PCR techniques commonly used for detection of Cryptosporidium parasites (7, 22, 23).

In recent years, researchers have also developed PCR-based techniques for differentiating C. parvum of human origin and C. parvum of animal origin. These techniques are based on the polymorphic nature of C. parvum strains that infect humans and most animals at the β-tubulin, oocyst wall protein (COWP), dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR), thrombospondin-related adhesive protein 1 (TRAP-C1), thrombospondin-related adhesive protein 2 (TRAP-C2), internally transcribed spacer 1 (ITS1), polythreonine repeat (Poly-T), small-subunit (SSU) rRNA, and undefined genomic sequences (2, 3, 5, 6, 11, 15, 17, 21, 26–28, 30–32). These genotyping tools, however, were designed to analyze clinical specimens, and the comparative performance of the protocols has not been evaluated previously. In this study, we compared eight genotyping protocols (3, 5, 6, 11, 17, 21, 26–28), two species-differentiating protocols (2, 15), and one species-differentiating and genotyping protocol (31) for detecting and differentiating Cryptosporidium parasites.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Oocysts and DNA extraction.

Fecal samples containing genotype 1 and genotype 2 of C. parvum (based on a DNA sequence analysis of the TRAP-C2, β-tubulin, and SSU rRNA genes), C. muris, C. serpentis, Eimeria neischulzi, E. papillata, and Giardia duodenalis oocysts were obtained from infected humans and animals and were stored at 4°C in 2.5% potassium dichromate solutions. Oocysts and cysts were purified following sucrose and Percoll flotation (1). Genomic DNA was isolated from the purified oocysts as described previously (27, 30) and was stored at −20°C until it was used. The concentrations of DNA samples were determined by UV absorption at 260 nm.

For sensitivity experiments, genomic DNA was extracted from 500,000, 200,000, 5,000, 1,000, 500, 250, 100, and 50 oocysts of a genotype 2 C. parvum isolate. The DNA was dissolved in 100 μl of water. Two microliters of each DNA stock preparation was used in the PCR in order to obtain the equivalent of 10,000, 4,000, 400, 100, 20, 10, 5, 2, and 1 oocysts per PCR mixture.

PCR.

Usually, the PCR mixture contained 50 ng of genomic DNA, each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, Calif.) at a concentration of 200 μM, 1× PCR buffer (GeneAmp 10× PCR buffer; 500 mM KCl, 100 mM Tris-Cl [pH 8.3], 15 mM MgCl2, 0.01% gelatin; Applied Biosystems, Branchburg, N.J.), 5.0 U of Taq polymerase (GIBCO BRL, Frederick, Md.), and the required amounts of forward and reverse primers in a total volume of 100 μl. The Mg2+ concentration was adjusted by adding MgCl2. DNA amplification was carried out with a Perkin-Elmer model PCR 9700 Gene Amp thermocycler for each pair of primers by using the previously described cycling conditions (initial hot start, denaturation, annealing, elongation, final extension, and total number of cycles). A negative control, consisting of a reaction mixture without the DNA template, was included in each experiment. Each PCR product was analyzed by electrophoresis in a 1.5% agarose gel and was visualized after ethidium bromide staining. The same DNA stock preparation was used as the template in all evaluation experiments.

PCR-RFLP analysis.

Restriction digestion and PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) techniques based on Poly-T repeats, COWP, DHFR, TRAP-C1, TRAP-C2, and the SSU rRNA gene were carried out by using previously described protocols (6, 11, 26–28, 31). For the restriction fragment analysis, 20 μl of amplified products was digested by using 10 U of BpuAI (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.), BstEI (Boehringer), HaeIII (New England BioLabs, Beverly, Mass.), RsaI (Promega, Madison, Wis.), SspI (New England BioLabs), or VspI (GIBCO BRL) and 5 μl of the appropriate restriction buffer for 1 h under the conditions recommended by the supplier. The digested products were fractionated by agarose gel electrophoresis and were visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

DNA sequencing and data analysis.

When desired, the amplified PCR product was purified by using the Wizard PCR Preps DNA purification system (Promega) and was sequenced with a model ABI 377 automated sequencer by using a dRhodomine terminator cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). A multiple alignment of the sequences was prepared by using the Genetics Computer Group program (10).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The COWP sequences determined in this study have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession no. AF161577 to AF161580.

RESULTS

Genotyping techniques evaluated in the present study.

In the present study we evaluated 16 primer pairs used for 11 previously described Cryptosporidium species differentiation and C. parvum genotyping protocols (Table 1). Of these 11 protocols, 4 are based on the rRNA gene (2, 5, 15, 31), 2 are based on unknown sequences (3, 17), and the remainder are based on COWP, DHFR, TRAP-C1, TRAP-C2, and Poly-T repeats (6, 11, 26–28); 10 of the 11 techniques amplified C. parvum DNA efficiently, and PCR fragments of the expected sizes were produced. The technique of Bonnin et al. (3) amplified DNA from C. parvum genotype 2 isolates. However, we were not able to amplify the DNA of C. parvum genotype 1, C. muris, and C. serpentis isolates under the conditions used in this study. No amplification was observed even after the Mg2+ concentration was modified and the amount of template was increased or decreased.

TABLE 1.

Sources of the genotyping primers used in this study

| Protocol

|

Target | Product size(s) (bp) | Type of PCR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authors | Reference | |||

| Awad-El-Kariem et al. | 2 | SSU rRNA | 556 | PCR-RFLP |

| Leng et al. | 15 | SSU rRNA | 1,750 | PCR-RFLP |

| Bonnin et al. | 3 | Unknown | 1,353 | PCR-RFLP |

| Carraway et al. | 5 | ITS1 of rRNA | 513 (human), 519 (bovine) | Genotype-specific PCR |

| Spano et al. | 26 | COWP | 553 | PCR-RFLP |

| Morgan et al. | 17 | Unknown | 411 (human), 311 (bovine) | Genotype-specific PCR |

| Gibbons et al. | 11 | DHFR | 408 | Nested PCR-RFLP |

| Carraway et al. | 6 | Poly-T | 318 | PCR-RFLP |

| Spano et al. | 27 | TRAP-C1 | 1,200 | PCR-RFLP |

| Sulaiman et al. | 28 | TRAP-C2 | 369 | PCR-RFLP |

| Xiao et al. | 31 | SSU rRNA | ∼825 | Nested PCR-RFLP |

Specificity of Cryptosporidium genotyping tools.

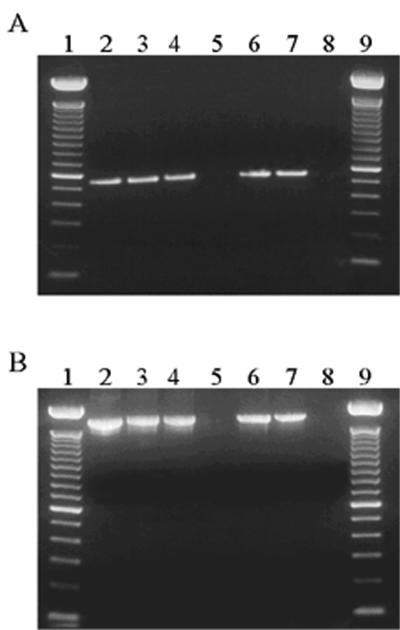

The specificity of the primers was examined by using DNA from three Cryptosporidium species (genotype 1 and genotype 2 of C. parvum, C. muris, and C. serpentis), two Eimeria species (E. neischulzi and E. papillata), and one Giardia species (G. duodenalis). The specificity data are summarized in Table 2. Three SSU rRNA gene-based protocols were used, and the primers of two of these protocols, those developed by Awad-El-Kariem et al. (2) and Leng et al. (15), amplified the DNA of Eimeria species in addition to the DNA of Cryptosporidium species, generating bands of similar sizes (Fig. 1). In contrast, the Cryptosporidium-specific primers developed by us (31) produced an ∼1,325-bp band during primary PCR and an ∼825-bp band during nested PCR from genomic DNA of all Cryptosporidium species but not from genomic DNA of Eimeria species or G. duodenalis.

TABLE 2.

Specificities of previously described Cryptosporidium species differentiation and C. parvum genotyping protocols

| PCR method

|

Amplificationa

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

C. parvum

|

C. muris | C. serpentis | E. neischulzi | E. papillata | G. duodenalis | |||

| Authors | Reference | Human | Bovine | |||||

| Awad-El-Kariem et al. | 2 | + | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| Leng et al. | 15 | + | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| Bonnin et al. | 3 | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| Carraway et al.b | 5 | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| Spano et al. | 26 | + | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| Morgan et al.b | 17 | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| Gibbons et al. | 11 | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| Carraway et al. | 6 | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| Spano et al. | 27 | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| Sulaiman et al. | 28 | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| Xiao et al. | 31 | + | + | + | + | − | − | − |

+, amplification; −, no amplification.

Both the genotype 1 and genotype 2 C. parvum-specific primers were tested.

FIG. 1.

Ethidium bromide-stained gel showing amplification products obtained from various members of the Apicomplexa by using the primers of protocols described by Awad-El-Kariem et al. (2) and Leng et al. (15). Lanes 1 and 9, 100-bp marker; lane 2, C. parvum; lane 3, C. muris; lane 4, C. serpentis; lane 5, G. duodenalis; lane 6, E. neischulzi; lane 7, E. papillata; lane 8, negative control. (A) Primers of Awad-El-Kariem et al. (2), which amplified a ∼556-bp product. (B) Primers of Leng et al. (15), which amplified a ∼1,750-bp product.

The PCR-RFLP protocol of Spano et al. (26) was found not to be C. parvum specific in this study, as it also amplified genomic DNA of C. muris and C. serpentis. The COWP gene-based primers did not amplify the DNA of non-Cryptosporidium parasites but did produce a 550-bp band with isolates of the two genotypes of C. parvum, C. muris, and C. serpentis. The Poly-T-based PCR-RFLP protocol of Carraway et al. (6), the TRAP-C1-based protocol of Spano et al. (27), the TRAP-C2-based protocol of Sulaiman et al. (28), and the DHFR-based nested PCR-RFLP protocol of Gibbons et al. (11) were found to be C. parvum specific; the primers used in these protocols amplified only the DNA of genotype 1 and genotype 2 isolates of C. parvum and did not amplify the DNA of non-C. parvum parasites.

The two ITS1-based genotype-specific primer sets used in the C. parvum genotyping protocol developed by Carraway et al. (5) amplified the genomic DNA of genotype 1 and genotype 2 C. parvum isolates. As expected, these primers did not amplify C. muris, C. serpentis, Eimeria, and Giardia genomic DNA. The C. parvum-specific randomly amplified polymorphic DNA diagnostic primers of Morgan et al. (17) produced a 411-bp band with genotype 1 C. parvum DNA when a human-specific primer was used and a 311-bp band with genotype 2 C. parvum DNA when bovine-specific primers were used. These primers did not amplify the genomic DNA of non-C. parvum parasites in this study.

Evaluation of PCR-RFLP protocols and nucleotide sequencing.

We also evaluated the restriction digestion procedures used in five different PCR-RFLP protocols (6, 11, 26–28, 31). The two species-differentiating protocols of Awad-El-Kariem et al. (2) and Leng et al. (15) were not evaluated further due to nonspecific amplification of DNA from other Apicomplexa species, such as E. neischulzi and E. papillata. An RFLP analysis of DHFR (11), Poly-T (6), TRAP-C1 (27), and TRAP-C2 (28) PCR products showed that the restriction patterns for genotype 1 and genotype 2 of C. parvum were distinct, as reported in the original papers. Restriction digestion of SSU rRNA products could be used to differentiate the Cryptosporidium species, as well as the two genotypes of C. parvum, as reported previously (31).

The PCR-amplified COWP products (26) of genotype 1 and genotype 2 C. parvum and C. muris isolates were digested with restriction endonuclease RsaI, which resulted in three distinct band patterns for these isolates (data not shown). Since the PCR product of a C. serpentis isolate was faint, it was not subjected to restriction digestion. However, all of the COWP PCR products were sequenced. A multiple alignment revealed that the sequences of genotype 1 and genotype 2 C. parvum, C. muris, and C. serpentis isolates were distinct.

Sensitivity of the genotyping primers, as determined by using genomic DNA extracted from known numbers of oocysts from C. parvum genotype 2 isolates.

Nine PCR protocols were also evaluated to determine their sensitivity for detecting Cryptosporidium parasites by using genomic DNA extracted from known numbers of oocysts of genotype 2 C. parvum isolates. Genotype 2 C. parvum oocysts were used in the sensitivity experiments because of their abundance. Sensitivity tests were not performed for the two protocols (2, 15) that were not specific. Our data on the sensitivity of primers revealed that the nested PCR protocols of Gibbons et al. (11) and Xiao et al. (31) were the most sensitive protocols as the two primer pairs amplified the DNA of even a single oocyst. The results of a comparison of the sensitivities of the genotyping primers are shown in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of the sensitivities of various genotyping PCR tools for detection of C. parvum oocysts

| Protocol

|

Primers | Target | Detection of the following no. of oocysts

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authors | Reference | 10,000 | 4,000 | 400 | 100 | 20 | 10 | 5 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Bonnin et al. | 3 | PAP1-PAP2 | Unknown | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| Carraway et al.a | 5 | Cry7-ITS1 | ITS1 | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| Carraway et al. | 6 | Cry39-Cry44 | Poly-T | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| Spano et al. | 26 | Cry15-Cry9 | COWP | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| Morgan et al.a | 17 | 021F-CPCR | Unknown | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| Gibbons et al. | 11 | Nested PCR | DHFR | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Spano et al. | 27 | Cp.E-Cp.Z | TRAP-C1 | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| Sulaiman et al. | 28 | Forward-Reverse | TRAP-C2 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − |

| Xiao et al. | 31 | Nested PCR | SSU RNA | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

For these protocols, C. parvum genotype 1-specific primers were not tested as the template was from a C. parvum genotype 2 isolate.

DISCUSSION

Results of recent molecular characterization studies have shown that there are extensive genetic differences among different Cryptosporidium species, as well as within C. parvum. These inter- and intraspecies differences have been used in the development of molecular diagnostic tools for Cryptosporidium spp. and for genotype differentiation. So far, at least two species-specific (2, 15) and seven genotyping-specific (3, 5, 6, 11, 17, 21, 26–28) protocols have been described. One PCR-RFLP protocol has been developed for both species and genotype differentiation (31). Most of these techniques have not been subjected to evaluation. Recently, several PCR techniques were evaluated to determine whether they detected C. parvum in environmental samples (7, 22, 23), but most of the species and genotype differentiation techniques were not included. The nature of environmental samples suggests that multiple Cryptosporidium spp. and C. parvum genotypes may be present. Therefore, the species differentiation and C. parvum genotyping techniques should be evaluated before they are used for analysis of environmental samples.

Two of the three Cryptosporidium species differentiation techniques based on the SSU rRNA gene were found not to be Cryptosporidium specific. The primers used in these two protocols (2, 15) amplified DNA from two Eimeria species (E. neischulzi and E. papillata). As RFLP was used for species differentiation and the taxon Apicomplexa contains thousands of species, the nonspecificity of the two techniques makes diagnosis of Cryptosporidium species unreliable. The major reason for the nonspecificity is the fact that conserved 18S rRNA sequence data were used when the primers were designed. The primers used by Leng et al. (15) are the universal primers used by most researchers to clone the SSU rRNA gene of eukaryotic organisms. However, another SSU rRNA-based PCR-RFLP protocol, the protocol of Xiao et al. (31), was shown to be Cryptosporidium specific. The primers used in this protocol did not amplify the DNA of non-Cryptosporidium species. This protocol differentiated three Cryptosporidium species and two genotypes of C. parvum.

Six C. parvum genotyping protocols, which were based on DHFR, TRAP-C1, TRAP-C2, ITS1, Poly-T repeats, and an unknown genomic sequence (5, 6, 11, 17, 27, 28), were found to be C. parvum specific. The primers used in these protocols amplified the DNA of genotype 1 and genotype 2 isolates of C. parvum but not the DNA of non-C. parvum species, Eimeria spp., or G. duodenalis. In the techniques of Carraway et al. (5) and Morgan et al. (17) genotype 1- and genotype 2-specific primers are used. The genotype 1-specific primers amplify DNA of C. parvum genotype 1 and not DNA of genotype 2 isolates, whereas the genotype 2-specific primers amplify DNA of C. parvum genotype 2 and not DNA of genotype 1 isolates. Our studies revealed that these four genotype-specific primers are indeed C. parvum genotype 1 or genotype 2 specific, as they amplified and distinguished the two genotypes of C. parvum, as claimed previously. The DHFR-, TRAP-C1-, TRAP-C2-, and Poly-T-based PCR-RFLP techniques (6, 11, 27, 28) were found to be C. parvum specific, and following restriction digestion of single-round PCR and nested PCR products two distinct band patterns were obtained for the genotype 1 and genotype 2 C. parvum isolates. However, a PCR protocol based on an unknown genomic sequence (3) was shown to be less sensitive, as it amplified only C. parvum genotype 2 isolates even after the Mg2+ concentration and the amount of DNA template were modified.

We found that the PCR-RFLP protocol based on the COWP gene (26) was not C. parvum specific, as the primers also amplified genomic DNA from other Cryptosporidium spp. However, the primers did not amplify the DNA of non-Cryptosporidium parasites. The COWP gene-based PCR-RFLP protocol has been reported to differentiate C. wrairi (some workers consider this organism C. parvum) from the two genotypes of C. parvum (26). We evaluated this technique by using C. muris and C. serpentis and identified distinct band patterns for these parasites. Furthermore, nucleotide sequencing of the PCR products also revealed similar distinct sequences for different species and genotypes. Therefore, the set of primers may be utilized for species- and genotype-specific diagnosis of Cryptosporidium parasites after the primer sequences are modified.

In summary, the PCR-RFLP protocols of Awad-El-Kariem et al. (2) and Leng et al. (15) for Cryptosporidium species differentiation described previously are not Cryptosporidium specific. We found that the set of primers developed by Bonnin et al. (3) has poor diagnostic sensitivity for genotype 1 C. parvum isolates. The PCR-RFLP method of Spano et al. (26) has the potential to distinguish different Cryptosporidium species (C. muris and C. serpentis), as well as the two genotypes of C. parvum. We found that the genotype 1-specific and genotype 2-specific primers of Carraway et al. (5) and Morgan et al. (17) are C. parvum specific, as these primers detected C. parvum genotype 1 and genotype 2 isolates. Similar results were obtained for the DHFR-, TRAP-C1-, TRAP-C2-, and Poly-T-based PCR-RFLP techniques of Gibbons et al. (11), Spano et al. (27), Sulaiman et al. (28), and Carraway et al. (6). The nested PCR-RFLP protocols developed by Gibbons et al. (11) and Xiao et al. (31) are the most sensitive protocols evaluated in this study. Additional evaluations with other apicomplexan parasites and Cryptosporidium species may be needed before these techniques can be used for analysis of environmental samples.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by interagency agreement DW 75937984-01-1 between the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and by Opportunistic Infectious Diseases funds from the CDC.

We thank William P. Shulaw, Bruce Anderson, and Richard J. Montali for providing Cryptosporidium and Eimeria oocysts and Giardia cysts.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arrowood M J, Sterling C R. Isolation of Cryptosporidium oocysts and sporozoites using discontinuous sucrose and isopycnic Percoll gradients. J Parasitol. 1987;73:314–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Awad-El-Kariem F M, Warhurst D C, McDonald V. Detection of Cryptosporidium oocysts using a system based on PCR and endonuclease restriction. Parasitology. 1994;109:19–22. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000077714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonnin A, Fourmaux M N, Dubremetz J F, Nelson R G, Gobet P, Harly G, Buisson M, Puygauthier-Toubas D, Gabriel-Pospisil F, Naciri M, Camerlynch P. Genotyping human and bovine isolates of Cryptosporidium parvum by polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of a repetitive DNA sequence. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;137:207–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cai J, Collins M D, McDonald V, Thompson D E. PCR cloning and nucleotide sequence determination of the 18S rRNA genes and internal transcribed spacer 1 of the protozoan parasites Cryptosporidium parvum and Cryptosporidium muris. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1131:317–320. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(92)90032-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carraway M, Tzipori S, Widmer G. Identification of genetic heterogeneity in the Cryptosporidium parvum ribosomal repeat. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:712–716. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.2.712-716.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carraway M, Tzipori S, Widmer G. A new restriction fragment length polymorphism from Cryptosporidium parvum identifies genetically heterogeneous parasite populations and genotypic changes following transmission from bovine to human hosts. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3958–3960. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.9.3958-3960.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Champliaud D, Gobet P, Naciri M, Vagner O, Lopez J, Buisson J C, Varga I, Harly G, Mancassola R, Bonnin A. Failure to differentiate Cryptosporidium parvum from C. meleagridis based on PCR amplification of eight DNA sequences. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:1454–1458. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.4.1454-1458.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cordell R L, Addiss D G. Cryptosporidiosis in child care settings: a review of the literature and recommendations for prevention and control. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1994;13:311–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fayer R, Speer C A, Dubey J P. The general biology of Cryptosporidium. In: Fayer R, editor. Cryptosporidium and cryptosporidiosis. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1997. pp. 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Genetics Computer Group. Wisconsin package, version 9.0. Madison, Wis: Genetics Computer Group; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gibbons C L, Gazzard B G, Ibrahim M, Morris-Jones S, Ong C S L, Awad-El-Kariem F M. Correlation between markers of strain variation in Cryptosporidium parvum: evidence of clonality. Parasitol Int. 1998;47:139–147. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson D W, Pienaiazek N J, Griffin D W, Misener L, Rose J B. Development of a PCR protocol for sensitive detection of Cryptosporidium oocysts in water samples. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:3849–3855. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.11.3849-3855.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laberge I, Ibrahim A, Barta J R, Griffiths M W. Detection of Cryptosporidium parvum in raw milk by PCR and oligonucleotide probe hybridization. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:3259–3264. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.9.3259-3264.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laxer M A, Timblin B K, Patel R J. DNA sequences for the specific detection of Cryptosporidium parvum by the polymerase chain reaction. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1991;45:688–694. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1991.45.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leng X, Mosier D A, Oberst R D. Differentiation of Cryptosporidium parvum, C. muris, and C. baileyi by PCR-RFLP analysis of the 18S rRNA gene. Vet Parasitol. 1996;62:1–7. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(95)00863-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mayer C L, Palmer C J. Evaluation of PCR, nested PCR, and fluorescent antibodies for detection of Giardia and Cryptosporidium species in wastewater. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:2081–2085. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.6.2081-2085.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morgan U M, Clare C, Constantine C C, Forbes D A, Thompson R C A. Differentiation between human and animal isolates of Cryptosporidium parvum using rDNA sequencing and direct PCR analysis. J Parasitol. 1997;83:825–830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morgan U M, O’Brien P A, Thompson R C A. The development of diagnostic PCR primers for Cryptosporidium using RAPD-PCR. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1996;77:103–108. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(96)02577-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morgan U M, Pallant L, Dwyer B W, Forbes D A, Rich G, Thompson R C A. Comparison of PCR and microscopy for detection of Cryptosporidium parvum in human fecal specimens: clinical trial. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:995–998. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.4.995-998.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Donoghue P J. Cryptosporidium and cryptosporidiosis in man and animals. Int J Parasitol. 1995;25:139–195. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(94)e0059-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peng M P, Xiao L, Freeman A R, Arrowood M J, Escalante A, Weltman A C, Ong C S L, MacKenzie W R, Lal A A, Beard C B. Genetic polymorphism among Cryptosporidium parvum isolates supporting two distinct transmission cycle. Emerg Infect Dis. 1997;3:1–9. doi: 10.3201/eid0304.970423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rochelle P A, Leon R D, Stewart M H, Wolf R L. Comparisons of primers and optimization of PCR conditions for detection of Cryptosporidium parvum and Giardia lamblia in water. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:106–114. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.1.106-114.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sluter S D, Tzipori S, Widmer G. Parameters affecting polymerase chain reaction detection of waterborne Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1997;48:325–330. doi: 10.1007/s002530051057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith H V. Environmental aspects of Cryptosporidium species: a review. J R Soc Med. 1990;83:629–631. doi: 10.1177/014107689008301012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith H V, Rose J B. Water borne cryptosporidiosis: current status. Parasitol Today. 1998;14:14–22. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(97)01150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spano F, Putignani L, McLauchlin J, Casemore D P, Crisanti A. PCR-RFLP analysis of the Cryptosporidium oocyst wall protein (COWP) gene discriminates between C. wrairi and C. parvum, and between C. parvum isolates of human and animal origin. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;150:209–217. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1097(97)00115-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spano F, Putignani L, Guida S, Crisanti A. Cryptosporidium parvum: PCR-RFLP analysis of the TRAP-C1 (thrombospondin-related adhesive protein of Cryptosporidium-1) gene discriminates between two alleles differentially associated with parasite isolates of animal and human origin. Exp Parasitol. 1998;90:195–198. doi: 10.1006/expr.1998.4324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sulaiman I M, Xiao L, Yang C, Escalante L, Moore A, Beard C B, Arrowood M J, Lal A A. Differentiating human from animal isolates of Cryptosporidium parvum. Emerg Infect Dis. 1998;4:681–685. doi: 10.3201/eid0404.980424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sulaiman I M, Xiao L, Arrowood M J, Lal A A. Biallelic polymorphism in the intron region of β-tubulin gene of Cryptosporidium parasites. J Parasitol. 1999;85:154–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Webster K A, Pow J D E, Giles M, Catchpole J, Woodward M J. Detection of Cryptosporidium parvum using specific polymerse chain reaction. Vet Parasitol. 1993;50:35–44. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(93)90005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xiao L, Escalante L, Yang C, Sulaiman I, Escalante A A, Montali R J, Fayer R, Lal A A. Phylogenetic analysis of Cryptosporidium parasites based on the small-subunit rRNA gene locus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:1578–1583. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.4.1578-1583.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xiao L, Sulaiman I M, Fayer R, Lal A A. Species and strain-specific typing of Cryptosporidium parasites in clinical and environmental samples. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz, Rio de J. 1998;93:687–692. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761998000500022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]