Abstract

For many cellular therapies being evaluated in preclinical and clinical trials, the mechanisms behind their therapeutic effects appear to be the secretion of growth factors and cytokines, also known as paracrine activity. Often, delivered cells are transient, and half-lives of the growth factors that they secrete are short, limiting their long-term effectiveness. The goal of this study was to optimize a hydrogel system capable of in situ cell delivery that could sequester and release growth factors secreted from those cells after the cells were no longer present. Here, we demonstrate the use of a fast photocross-linkable heparin-conjugated hyaluronic acid (HA-HP) hydrogel as a cell delivery vehicle for sustained growth factor release, which extends paracrine activity. The hydrogel could be modulated through cross-linking geometries and heparinization to support sustained release proteins and heparin-binding growth factors. To test the hydrogel in vivo, we used it to deliver amniotic fluid-derived stem (AFS) cells, which are known to secrete cytokines and growth factors, in full thickness skin wounds in a nu/nu murine model. Despite transience of the AFS cells in vivo, the HA-HP hydrogel with AFS cells improved wound closure and reepithelialization and increased vascularization and production of extracellular matrix in vivo. These results suggest that HA-HP hydrogel has the potential to prolong the paracrine activity of cells, thereby increasing their therapeutic effectiveness in wound healing.

Keywords: skin regeneration, photopolymerization, growth factor release, amniotic fluid-derived stem cells, hyaluronic acid

INTRODUCTION

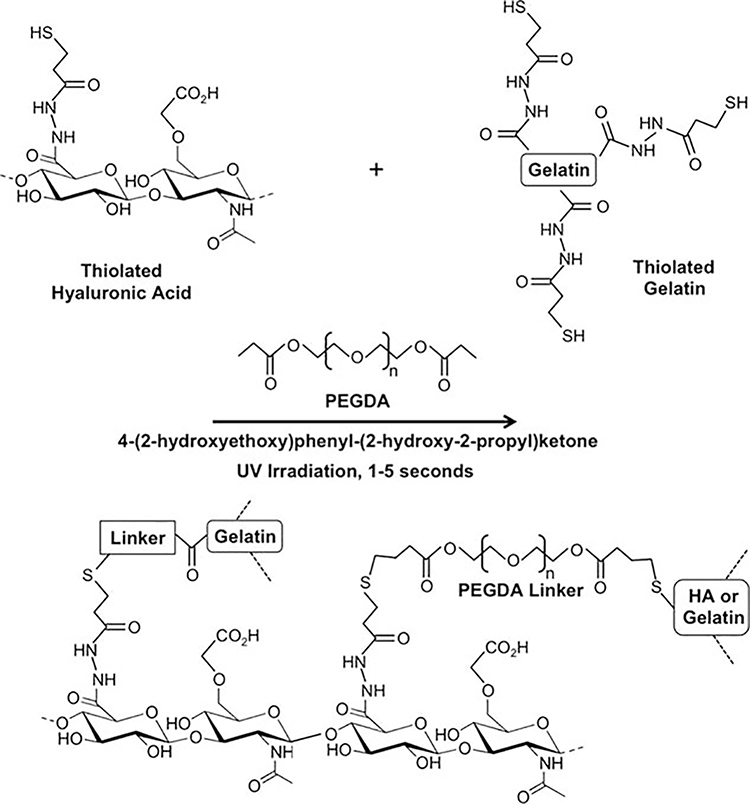

Hydrogel biomaterials have been widely explored for applications in regenerative medicine. In particular, due to the ability to customize their cross-linking characteristics and manipulate available functional moieties, hydrogels have seen extensive exploration as delivery vehicles and biofabrication materials in which living cells can be incorporated. When in optimal hydrogel environments, cells can thrive, proliferating, differentiating into other cell types, or secreting cytokines such as growth factors with therapeutic effects. One such hydrogel explored for these purposes has been hyaluronic acid (HA), a nonsulfated glycosaminoglycan (GAG),1,2 which has been manipulated into various forms using numerous chemistries and modifications,3,4 including a modular system consisting of thiolated HA, thiolated gelatin, and a polyethylene glycol diacrylate (PEGDA) crosslinker (commercially available as HyStem by ESI-BIO).5,6 This hydrogel has been implemented in numerous regenerative medicine applications, including three-dimensional (3-D) cell culture,7 postsurgical adhesion prevention,8 tumor xenografts,9,10 and wound healing.11 However, in their native form, these materials require 15–30 minutes to polymerize, which is unsuitable for the fast delivery and deposition speeds required in applications such as cell therapy delivery and 3-D bioprinting. To overcome that limitation, variations of HA hydrogels using different cross-linking approaches have been explored in order to provide a set of materials with properties that enable extrusion deposition. These hydrogel modifications have resulted in enhanced control over hydrogel elastic modulus,12 multistep photocross-linking,13,14 and hydrogels with fusion capabilities.15 Recently, we found that by adding common photoinitiators to a solution comprised of thiolated HA, thiolated gelatin, and PEGDA, near instantaneous photopolymerization could be induced by UV irradiation, which based on evaluation of material characteristics, was determined to be optimal for cell delivery applications.16

One clinical application in which cell delivery can be employed is the treatment of skin wounds. Extensive burns and full thickness skin wounds can be devastating to patients, even when treated, potentially resulting in long-term complications. It is estimated that over 500,000 burns are treated in the United States each year,17,18 with an overall mortality rate of 4.9% between 1998 and 2007. In addition to burns, full-thickness chronic wounds constitute another large patient base, and despite development of new treatments, healing rates remain below 50% successful.19 These difficult to heal chronic wounds are estimated to effect 7 million people per year in the United States, resulting in yearly costs approaching $25 billion.20 Patients benefit from rapid treatments that result in complete closure and protection of the wounds during the healing process to prevent extensive scarring and negative long-term physiological effects.

In recent years, cell spraying and bioprinting technologies have been tested as wound treatments. We previously demonstrated the effectiveness of this approach by bioprinting amniotic fluid-derived stem (AFS) cells, a stem cell from the perinatal environment with a number of therapeutic properties in wound healing model.21–25 To date, there are now over 500 published studies describing the efficacy of cells derived from the amnion for a myriad of diseases and disorders, including bone defects, Crohn’s disease, bladder reconstruction, lung disease, liver disease, kidney disease, multiple sclerosis, stroke, diabetes, and heart disease.26–48 Delivery of AFS cells in a fibrin–collagen blend hydrogel over full thickness skin wounds in a mouse model not only accelerated wound closure but also induced an increase in vascularization of the tissue.49 However, these cells did not permanently integrate into the tissue, suggesting that healing was due to paracrine activity of secreted trophic factors. Indeed, proteomics data revealed that AFS cells have the capability to secrete a variety of therapeutic growth factors. However, the fibrin–collagen material employed cross-linked slowly and tended to sluff off the wound due to the convex shape of the animals’ backs, resulting in the loss of material and cells. Following this work, we set about to further optimize the biomaterial delivery vehicle in order to maximize the biological function of the cells—their paracrine activity in particular—and wound application efficiency. We continued to focus on cell delivery, rather than delivery of a discrete selection of growth factors, because tissue regeneration is complex, involving a complex array of multiple factors. Cells have the ability to respond to their environment and release different panels of growth factors based on changes in their surrounding microenvironment and other endogenous signals.

The properties of HA hydrogels, including its naturally anti-inflammatory nature of,50–52 the ability to incorporate covalently bound heparin for growth factor release,53–57 and variety of available cross-linking kinetics, including nearly instantaneous in situ photocross-linking through thiol–ene chemistry,14,58 combined with the proangiogenic and wound healing properties of AFS cells, suggest that they can be used together as an “off the shelf” cell therapy product for wound healing. Herein, we demonstrate the use of a heparinized HA hydrogel for delivery of AFS cells via bioprinting for wound healing in a murine skin wound model. We hypothesized that this treatment combination would facilitate wound healing through paracrine activity and thus, can be further considered for clinical application for large or chronic, nonhealing skin wounds.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Hydrogel preparation

HyStem-HP hydrogel (HA-HP) or HyStem hydrogel (HA) (ESI-BIO, Alameda, CA) components were dissolved in sterile water. Briefly, heprasil (thiolated HA with conjugated heparin groups) or glycosil (thiolated HA) and gelin-S (thiolated gelatin) were dissolved in water containing 0.05% (w/v) 2-hydroxy-4′-(2-hydroxyethoxy)–2-methylpropiophenone photoinitiator (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) to make 1% (w/v) solutions. Extralink, a PEGDA cross-linker, was dissolved in water containing the photoinitiator to make a 2% (w/v) solution. Heprasil (or glycosil), gelin-S, and extralink were then mixed in a 2:2:1 ratio by volume, vortexed, and irradiated with UV light (365 nm, 18 W/cm2) at a distance of 3 cm to initiate a thiol–ene stepwise cross-linking reaction (Figure 1). In order to encapsulate cells, the solution was used to resuspend a cell pellet, after which the cell suspension was irradiated to cross-link. For initial cross-linker-based studies, a four-arm PEG-acrylate cross-linker (10 kDa MW; Creative PEGWorks, Winston-Salem, NC) and an eight-arm PEG-acrylate cross-linker (10 kDa MW) were substituted for the linear PEGDA cross-linker described above in order to modulate cross-linking density.12,59

FIGURE 1.

UV irradiation-driven thiol–ene photopolymerization in the presence of the photoenitiator 4-(2-hydroxyethoxy)phenyl-(2-propyl)-ketone forms a hydrogel network quickly in several seconds.

Culture of AFS cells

Multipotent stem cells were isolated from human amniotic fluid as previously described.23,24 To achieve a relatively homogenous subpopulation, the cells were expanded in culture from a single clone. AFS cells (H1 clone, passage 16) were expanded in tissue culture plastic using 150 mm diameter dishes (37°C, 5% CO2) until 75% confluence with Chang Media [α-MEM with 18% Chang B (Irvine Scientific, Santa Ana, CA), 15% ES-FBS (HyClone), 2% Chang C (Irvine Scientific)]. Cells were detached from the substrate with Accutase (Innovative Cell Technologies, San Diego, CA) and counted prior to centrifugation. Pellets of 5 million cells were resuspended in 500 μL of the hydrogel precursor solution immediately prior to use.

Cross-linker-based bovine serum albumin release and basic hydrogel characterization

Nonheparinized HA hydrogels (HyStem) were prepared as described above with the three cross-linkers (linear, four-arm, and eight-arm) in 1 mL volumes in 24-well plates. During mixing of hydrogel components, 10 bovine serum albumin (BSA) was incorporated within the gels. Phosphatebuffered saline (PBS; 1 mL) was added on top of each hydrogel construct, and the plates were then transferred into an incubator at 37°C. At 24 hour increments, the supernatant was removed and frozen for storage, and fresh PBS was added to the hydrogels. After 14 days, the sets of samples were quantified for total protein content using a Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific, cRockford, IL), and the data were used to generate a cumulative protein release curve.

To evaluate porosity, linear, four-arm, and eight-arm-cross-linked HA hydrogels were frozen, lyophilized, after which microstructures were imaged by scanning electron microscopy. Pore size was assessed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health) for image calibration and quantification. Average pore sizes for each experimental group were determined based on 20 measured pores.

Additionally, shear elastic modulus of the hydrogel formulations were determined by rheology as has been previously described.12,13,15 Briefly, the hydrogel varieties described above, including the heparinized HA-HP hydrogels (yielding six total formulations), were prepared as described above and pipetted into 35-mm Petri dishes and cross-linked. Rheological testing was performed using an HR-2 Discovery Rheometer (TA Instruments, Newcastle, DE) with a steel 12-mm parallel plate geometry in ambient conditions. To initiate measurements, the 35-mm Petri dish containing the hydrogels was immobilized on the rheometer stage using double-sided tape, after which the 12-mm steel plate geometry was lowered until contact with the surface of the hydrogel was made. The disc was lowered further until the axial force on the instrument, or normal force acting on the disc from the hydrogel, equaled 0.4N. At this point, the shear elastic modulus G′ was measured for each hydrogel using a shear stress sweep test ranging from 0.6 to 10 Pa at an oscillation frequency of 1 Hz applied by the rheometer.

Lastly, AFS cells were seeded on the six HA hydrogel formulations in order to evaluate cell proliferation and cytocompatiblity in vitro. Initially, 25,000 cells were seeded per hydrogel in 48-well plates (n = 3). On days 4, 7, and 14, total cellular mitochondrial metabolism was quantified by (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium) (MTS) assays (Promega, Madison, WI). Total mitochondrial metabolism is generally proportional to cell number, allowing determination of relative cell number increases over time in culture.

AFS cell-secreted in vitro protein release and kinetic release models

HA-HP hydrogels have previously been demonstrated to support extended growth factor release when loaded with heparin-binding growth factors at time of polymerization.53,54 This property of the hydrogel is desirable as AFS cells secrete cytokines effective in accelerating wound healing as we previously demonstrated.49 To characterize the release of AFS-secreted cytokines from the hydrogel, AFS cells were encapsulated in HA-HP or HA hydrogels in 96-well plates at a density of 100,000 cells/50 μL, and the released protein was quantified over 14 days. Serum-free α-MEM media (100 μL) was added on top of each hydrogel-cell construct, and the plates were then transferred into an incubator at 37°C. At 24-hour increments, the media were removed and frozen for storage, and 100 μL of fresh media were added to the hydrogels. After 14 days, the sets of samples were quantified for total protein content using a Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit, and the data were used to generate the protein release curve used in the kinetic modeling as described below.

In vitro FGF and VEGF release and kinetic release models

To further narrow in on a potential biological mechanism that may be important in wound healing, we specifically analyzed the release of AFS-secreted FGF and VEGF using the media aliquots collected above. Quantification of the released growth factors over the 14-day time course was quantified by a FGF Human ELISA Kit and VEGF Human ELISA Kit (Cat. # ab99979 and ab100662; Abcam, Cambridge, MA). The resulting data from above were converted into cumulative protein released and plotted versus time.

Next, to model the kinetics of the FGF and VEGF release, four release models were applied to the data to achieve a best fitting model. First, a first-order release model was applied to the data. First-order release rates can be described by the following equation:

| (1) |

where Qt is the cumulative amount of drug released at time t, K is the first order release constant, and t is the time in days. Second, the Hixson–Crowell release model applied to the data. Hixson–Crowell release rates can be described by

| (2) |

where Qt is the cumulative amount of drug released at time t, KHC is the Hixson–Crowell release constant, and t is the time in days. In this model, the application of the cube root describes release that is impacted by changes to the surface area or volume of the container (the hydrogel) by degradation or dissolution. Third, the Higuchi release model was applied to the data. Higuchi release rates can be described by

| (3) |

where Qt is the cumulative amount of drug released at time t, KH is the Higuchi release constant, and t is the time in days. In this model, the cumulative release is plotted against the square root of time, effectively providing a model that is governed by diffusion of the released protein through the hydrogel matrix. Lastly, the Korsmeyer–Peppas (K–P) release model was applied to the data. K–P release can be described by

| (4) |

where F is the fraction of drug released at time t, Mt is the amount of drug released at time t, M is the total amount of drug released, Km is the kinetic constant, and n is a diffusion or release exponent. After fitting the data, the value of n indicates the particular type of diffusion modeled by the system. Linear best-fit lines were fit to each of these four models.

Animal surgery and cell-hydrogel deposition

All animal studies were approved by and performed in accordance with the policies of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Wake Forest School of Medicine, which fall under the ethical guidelines of the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science. nu/nu nude mice (female young adults; 10–15 weeks old; average weight 25–30 g) were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA).

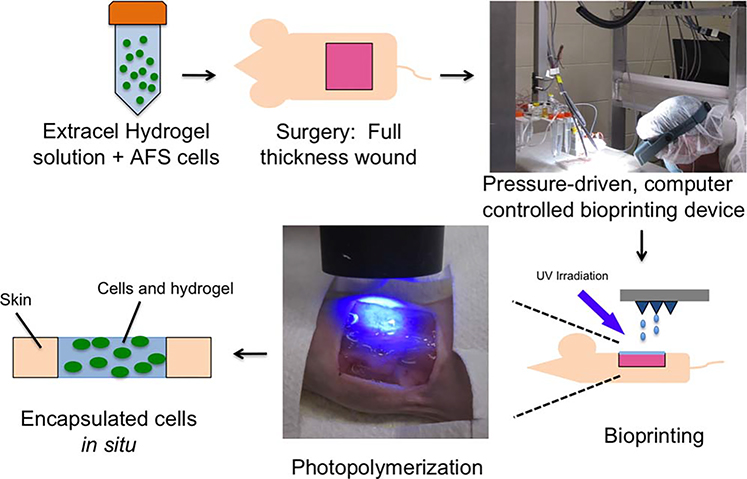

Each aliquot of 5 million cells in 500 μL of the hydrogel precursor solution were mixed fresh before each administration. Anesthesia was induced with 3% isoflurane by air in an approved anesthetic chamber, after which anesthesia was maintained by 1% isoflurane by air through a nose cone for ~30 minutes per surgical protocol. While under anesthesia, a single full thickness skin wound (2.0 cm × 2.0 cm) was surgically created with scissors on the mid-dorsal region of nu/nu mice. A bioprinting device developed in-house,60 originally employed for cell deposition in fibrin/collagen hydrogels as previously described,49 was used for the bioprinting of cells and hydrogels. Briefly, the device consists of a carriage with three-axis movement capability in which is housed the main print head. The print head is made up of a set of pressure-driven nozzles through which the hydrogel solutions, with or without cells, are printed, and an additional set of high-pressure nozzles through which secondary solutions, such as cross-linking solutions if necessary, can be printed. The printable hydrogel solutions are housed in swappable cartridges in-line with the back-pressure and the print nozzles. The printing process is then controlled using software also developed in-house.

For treatment, the bioprinter was used to deposit a layer of the hydrogel precursor solution with cells (HA-HP or HA-only) in the wound bed. The precursor solution was photopolymerized in place instantaneously as the solution met the wound bed using the 365 nm UV light source described above. Additionally, no treatment controls were included. Triple antibiotic (bacitracin zinc, neomycin sulfate, polymyxin-B sulfate; Medi-First, Fort Myers, FL) was applied over each wound after gelation, followed by a Tegaderm bandage (3M, St. Paul, MN). Finally, a custom-made bandage was sutured in place in order prevent the Tegaderm from being removed. Analgesia was administered using buprenorphine (0.1 mg/kg) one time postoperatively. Ketoprofen (5 mg/kg) once every 24 hours for 72 hours. No signs of distress or pain were observed during the study following surgery. Wound size was documented by taking photographs immediately after surgery and again at 4, 7, 10, and 14 days (n = 5). Animals were euthanized at 7 and 14 days, and the regenerated skin was harvested for histological analysis. With the two treatment groups and the control group, two euthanasia time points and n = 5 per condition and time point, a total of 30 mice were used in the study.

Cell tracking

In cellular therapies it is important to document the fate of the administered cells. In order to accomplish this, GFP-tagged AFS cells were implemented within the surgical procedure described above. For visualization and tracking of the printed cells, AFS cells were genetically labeled with green fluorescent protein (GFP), using a lentivirus vector carrying the GFP gene (Lenti-GFP), with a standard procedure. Labeling efficiency (70–80%) was verified and sorted by FACS. The cells were then expanded as needed to reach sufficient numbers for bioprinting. The bioprinting surgery was repeated, after which animals were euthanized at 1, 4, 7, and 14 for cell tracking purposes and to evaluate the consistency and distribution of bioprinted cells.

Gross histology—wound closure, contraction, and reepithelialization

Wound closure, contraction, and re-epithelialization percentages were calculated using photographs and histological examination of the wounds, taken at the time of surgery, days 4, day 7, day 10, and day 14. Using ImageJ software, the original wound area was defined as A, the reepithelialized skin area was defined as B, and the remaining unclosed wound was defined as C. Percentage of wound closure was defined as C/A × 100%, percentage of contraction of the wound was defined as (A − B)/A × 100%, and percentage of reepithelialization was defined as (B − C)/B × 100%. Finally, the aspect ratio of the original wound borders was determined to assess whether contraction was uniform in the X–Y plane. The length of the wound (L) was measured along the direction of the spine, and the width of the wound (W) was measured across the spine. Aspect ratio was defined as L/W.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Harvested skin tissues were first rolled around a syringe needle prior to being fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde. Samples were then washed in PBS three times for 30 minutes per wash, after which the samples were transferred to 30% sucrose for an overnight incubation at 4°C. The rolled tissues were then sliced in half and flash frozen in OCT blocks in liquid nitrogen. A cryotome (Leica) was used to generate 6 μm sections comprised of the entire cross-sections of the regenerating wounds. These slides were stored at −20°C until histological procedures were performed. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for histology, and slides were imaged under light microscopy. Attention was paid to the presence of blood vessels in the regenerated tissue and re-epithelialization of keratinocytes across the surface of the wound area. Quantification of neovascularization was done by determining the microvessel density (MVD) in H&E-stained wound cross-sections. To do this, ImageJ software was used to perform measurements on histological images. For MVD, first the cross-sectional area of tissue in the image was determined. Within that area, the number of vessels was counted. MVD values were calculated by dividing the area by the number of vessels, after which the average MVD per group was determined.

Histology staining of elastin, GAGs, and polysaccharides and immunohistochemical staining of collagen I and collagen III

In addition to H&E staining, several stains were used to assess the presence of various extracellular matrix (ECM) components. Verhoeff-Van Geison and alcian blue histology protocols were performed in order to stain elastin fibers and GAGs/proteoglycans, respectively. Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining with collagen type I and type III antibodies was performed to assess relative levels of collagen between groups and time-points. For IHC, all incubations were carried out at room temperature unless otherwise stated. Slides were warmed at 60°C for 1 hour to increase bonding to the slides. Antigen retrieval was performed on all slides and achieved with incubation in Proteinase K (Dako, Carpinteria, CA) for 5 minutes. Sections were permeabilized by incubation in 0.1% Triton-X for 5 minutes. Nonspecific antibody binding was blocked by incubation in Protein Block Solution (Abcam) for 15 minutes. Sections were incubated for 60 minutes in a humidified chamber with the primary anti-collagen type I antibodies (raised in rabbit, Cat. # ab34710; Abcam) at a 1:200 dilution antibody diluent (Abcam) and with the primary anticollagen Type III antibodies (raised in goat, Cat. # 1330–01; Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL) at a 1:200 dilution in antibody diluent. Following primary incubation, slides were washed three times in PBS for 5 minutes. Sections were then incubated for 60 minutes with DyLight 594-conjugated AffiniPure Anti-Rabbit IgG secondary antibodies in a 1:200 dilution in antibody diluent and Anti-Goat IgG Alexa Fluor 488 secondary antibodies in a 1:200 dilution in antibody diluent. The sections were washed in PBS three times for 5 minutes, counterstained with DAPI, and cover-slipped with Prolong Gold Anti-Fade (Dako). Native skin samples were present as positive controls and were used for comparison. Negative controls were set up at the same time as the primary antibody incubations and included incubation with PBS, in place of the primary antibody. No immunoreactivity was observed in these negative control sections.

Fluorescent imaging of GFP-tagged AFS cells for cell tracking

To investigate whether the deposited cells remain in the regenerating skin long-term after the bioprinting, GFP-transfected AFS cells were used. Animals were euthanized on days 1, 4, 7, and 14, after cell bioprinting and skin samples were harvested and prepared for histology as described above. Samples were then washed three times in PBST, counterstained with DAPI, and washed three times before mounting with Prolong Gold Antifade Reagent (Invitrogen). Sections were imaged using fluorescence microscope and representative images were recorded.

Statistical analysis

All quantitative results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Experiments were performed in triplicate or greater. Values were compared using Student’s t test (two-tailed) with two sample unequal variance, and p < 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Hydrogel formation and cell encapsulation

The hydrogel photopolymerization chemistry (Figure 1) allowed for fast cross-linking that ensured effective encapsulation and delivery of AFS cells (5 × 106 cells/0.5 mL) within the wound volume. We hypothesized that these properties would allow for complete spatial control during polymerization, resulting in accurate deposition of cell containing hydrogel solutions uniformly across a wound bed, despite curvature of the body part. Preliminary photopolymerization tests verified that the hydrogel precursor solution could be easily delivered via syringe or automated bioprinting devices in any desired volume and cross-linked nearly instantaneously with UV light as desired. These gelation kinetics are integral for effective delivery to irregular wound sites. Importantly, previous studies using this form of UV cross-linking chemistry for hydrogel formation, as well as, tests with photocross-linkable methacrylated HA hydrogels showed that UV-induced cross-linking was not cytotoxic to cells.13,16 Additionally, swelling and in vitro stability testing was performed. These HA hydrogels were found to undergo some swelling depending on cross-linking method, but less swelling than several other materials screened, such as methyl cellulose-HA, chitosan, chitosan–collagen, and PEGDA. In vitro stability was determined by incubation in PBS for 14 days, during which bulk stability was assessed daily. No loss of hydrogel integrity was observed in the HA hydrogels.16

Evaluation of hydrogel cross-linking density on BSA release, porosity, elastic modulus, and cell proliferation

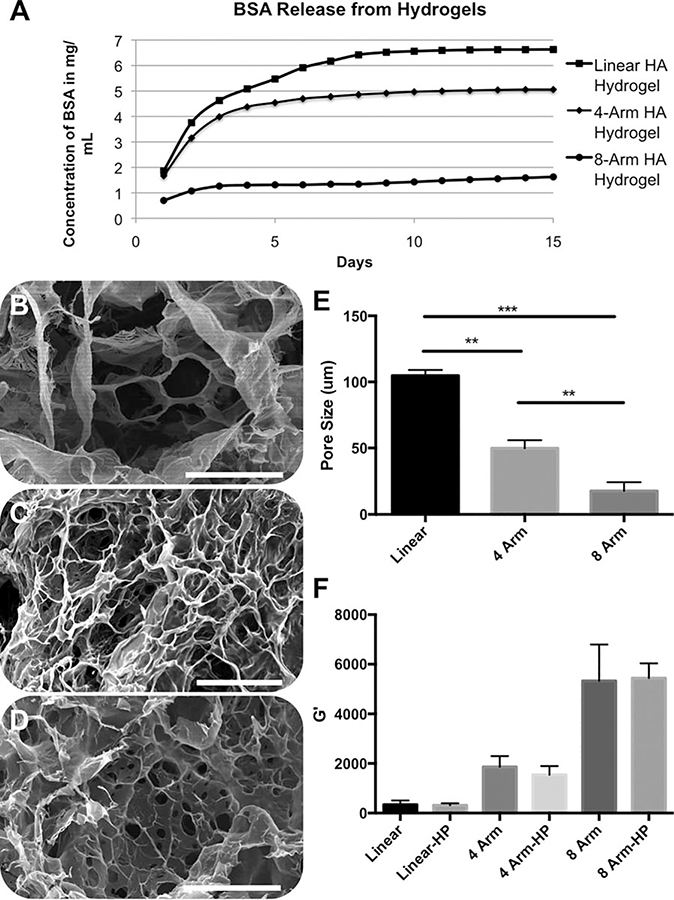

Cumulative BSA release curves were generated from the quantification of BSA released daily from HA hydrogels cross-linked with linear, four-arm, or eight-arm cross-linkers [Figure 2(A)]. The resulting curves show a clear trend in which BSA was released more rapidly and cumulatively in a higher total amount in the linear cross-linker hydrogels in comparison to the four-arm and eight-arm hydrogels over the 2-week time course. Likewise, the four-arm HA hydrogel released BSA at an increase rate and with higher cumulative amount than then eight-arm HA hydrogel. To evaluate if these differences correlated with differences in cross-linking density, SEM imaging was used to determine the average pore size of the three hydrogel formulations. As expected, linear cross-linking resulted in the largest pores [average ~100 μm, Figure 2(B)], and as the number of arms per cross-linking molecule increased the pore sizes decreased: four-arm: average ~50 μm [Figure 2(C)] and eight-arm: average ~25 μm [Figure 2(D)]. These data, summarized in Figure 2€, suggest that the increased cross-linking density, and associated decreased pore size, results in slower and sustained BSA diffusion out of the hydrogel.

FIGURE 2.

(A) Cumulative release of BSA as an effect of the cross-linker geometry employed to form the HA hydrogels. SEM images showing pore structures of lyophilized HA hydrogels: (B) linear cross-linker, (C) four-arm cross-linker, and (D) eight-arm cross-linker. (E) Quantification of porosity. (F) Rheological quantification of the shear elastic modulus in HA-only and heparinized HA (denoted with “HP”) hydrogels as an effect of cross-linker type. Statistical significance: **p < 0.05. Scale bars = 200 μm.

We were also interested in leveraging heparin-mediated growth factor release in the hydrogels (described in the next section) using HA-HP hydrogels. We first verified that pore size was similar between HA and HA-HP hydrogels, which they were [Supporting Information Figure 1(A–C)]. Additionally, we verified additional mechanical similarity between the HA-HP hydrogels and HA hydrogels by determining their elastic modulus, a characteristic dependent on cross-linking density, using rheometry. Rheological data [Figure 2(E)] showed that for each cross-linker geometry (linear, four-arm, and eight-arm), the corresponding HA-HP and HA did not differ significantly in shear elastic modulus. Also, we have observed in other studies,12,59,61 as cross-linking density increased, elastic modulus increased.

Next, in a basic cytocompatibility test, MTS assays were used to quantify mitochondrial metabolism of AFS cells over 2 weeks to assess proliferative activity of the cells on each of the six hydrogels, as well as a tissue culture plastic control. In general, all gel formulations supported positive proliferation over time and were superior to the two-dimensional plastic culture control [Supporting Information Figure 1(D)].

These results suggested that for the intended AFS cell delivery wound healing experiments, which in other studies required ~2 weeks,49 the linear cross-linker hydrogel formulation would likely support release of the largest amount of proteins and cytokines secreted by the AFS cells. Conversely, the four-arm and eight-arm formulations would limit protein release but might be useful in other applications requiring long-term release kinetics, such as the treatment of chronic, nonhealing wounds. Additionally, by comparing HA and HA-HP mechanical properties and cyto-compatibility, we rationalized that we could swap HA with HA-HP, potentially allowing us to capitalize on both cross-linking density release kinetics control and heparin-binding growth factor release. This latter feature was then assessed.

Protein release, FGF and VEGF release, and kinetic release models

To evaluate the effectiveness of HA-HP at delaying cytokine release through heparin-mediated growth factor binding, release of total protein, FGF, and VEGF from AFS-hydrogel constructs was quantified over a 14-day time course. First, protein release from AFS cells in the HA-HP hydrogels was measured (Supporting Information Figure 2), showing a slowing of release after the first several days, and yet a measurable release was sustained through the entire time course.

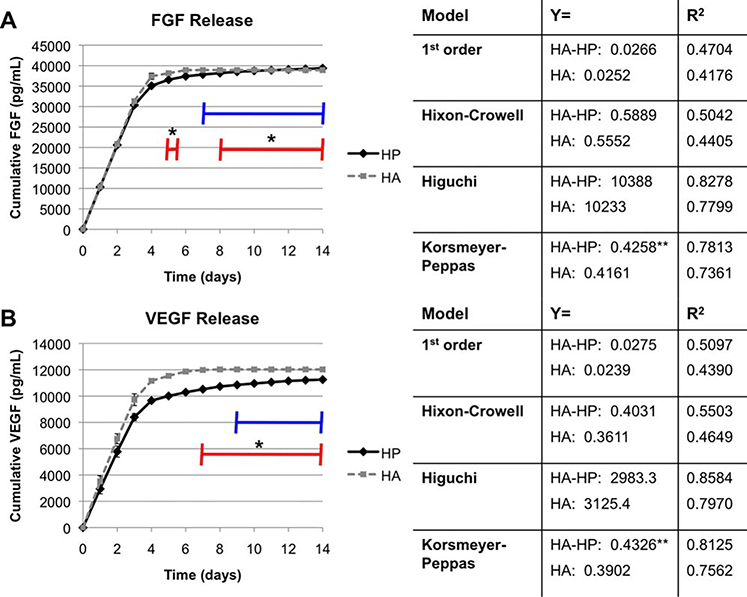

To further test the impact of heparinization on growth factor kinetics, we specifically analyzed the release of AFS-secreted FGF and VEGF from HA-HP hydrogels and HA-only hydrogels. In our previous wound healing study, AFS cells secreted therapeutic relevant concentrations of FGF and VEGF, and AFS-treated wounds showed vastly accelerated blood vessel formation.49 Both FGF and VEGF are known heparin-binding growth factors that are proangiogenic. Furthermore, the heparinized HA hydrogels have been implemented in the past by others for controlled release of these growth factors.55,56 Growth factor release curves from AFS-hydrogel constructs (HA-HP and HA-only) showed HA-HP release of FGF to be relatively constant until day 4, after which release slowed, but remained positive [Figure 3(A)]. The HA-only constructs showed similar release for the first 4 days, after which release slowed. Notably, after day 7, no FGF release was detected from the HA-only constructs. Furthermore, on day 5, and from day 8 onward, daily release was significantly greater (p < 0.05) in the HA-HP constructs.

FIGURE 3.

HA-HP hydrogel supports long-term release of (A) FGF and (B) VEGF secreted by encapsulated AFS cells. Red line—HA-HP supports significantly greater daily VEGF release than HA gels (p < 0.05). Blue line—time period during which zero FGF/VEGF is released from the HA gels. Release kinetic models (first order release, Hixson–Crowell release, Higuchi release, and Korsmeyer–Peppas release) were fit to the data characterizing the mechanism of release. High R2 values of the Higuchi and Korsmeyer–Peppas models indicate that the release is mediated by diffusion through a polymer matrix, as expected. Dotted box—regression line fit to Extracel-HP curve. Dashed box—regression line fit to the fibrin–collagen curve. The x-coefficients of the regression lines indicate Fickian versus non-Fickian diffusion.

Similarly, HA-HP release of VEGF [Figure 3(B)] remained relatively constant until day 4, after which it gradually slowed. Again, it should be noted that release remained positive through the duration of the study. Similar to the FGF release, VEGF release decreased to zero in HA-only constructs from day 9 onward. Additionally, from day 7 onward, daily release was significantly greater (p < 0.05) in the HA-HP constructs. Documentation of this increased long-term release capability in heparinized HA is significant as it supports presentation and sustained release of growth factors over the entire course of wound healing. While release slowed to several picograms per day, this sustained supply of cytokines appears to be enough to maintain accelerated wound regeneration. Specifically, long-term presentation of FGF and VEGF by heparin-binding is likely contributed to the significant increase in angiogenesis in HA-HP treated wounds. Additionally, since HyStem-HP is a modular hydrogel system, we suspect we can modulate the release profiles by changing the concentration and ratios of hydrogel components in order accommodate different stages and time courses of wound healing if necessary.

Hydrogel release mechanisms were assessed using with a set of four kinetic mathematical models. Quantification of modeling was important to verify that the general mechanism of release of growth factors from our material was in line with the actual designed hydrogel system components. A first order release model, the Hixson–Crowell model, the Higuchi model, and the K–P model were applied to the release data described above. First-order models describe simple diffusion without a physical barrier to prevent diffusion. The Hixson–Crowell model describes release that is impacted by changes to the surface area or volume of the container (the hydrogel) by degradation or dissolution, similar to surface dissolution of a drug pill. The Higuchi model effectively provides a model that is governed by diffusion of the released protein through a polymer network, such as the hydrogel matrix. Lastly, the K–P release model describes Fickian versus non-Fickian diffusion, which can indicate more complex diffusion behaviors.

The models were compared using the R2 values generated regression lines fitting the data. The four kinetic mathematical models are summarized in the right panels of Figure 3(A,B), and the kinetic model curves are shown in Supporting Information Figures 3 and 4. R2 values indicated that the Higuchi and K–P diffusion-mediated release models were the most accurate for protein release (R2 of 0.9565 and 0.97565, respectively), as well as growth factor release (R2 of 0.8278 and 0.7813, respectively, for FGF, and 0.8584 and 0.8125, respectively, for VEGF). This is expected, as secreted proteins such as growth factors would be required to diffuse through the polymer network to reach the fluid outside of the hydrogel. The K–P model denotes Fickian versus non-Fickian diffusion depending on the value of the n parameter of the model [Eq. (4)]. If n is below 0.45, release is considered Fickian and depends primarily on basic diffusion principles, while above 0.45 release is considered non-Fickian and refers to a combination of both diffusion and erosion of the network. HA-HP constructs resulted in n = 0.4258 and 0.4326 and HA-only constructs resulted in n = 0.4162 and 0.3902 for FGF and VEGF release, respectively. This behavior comes close to the fluid mechanics properties of non-Fickian diffusion, suggesting that degradation of the matrix may also contribute to the release profile. This also suggests that the HA materials may be susceptible to degradation in situ, allowing cells to remodel it more easily during the healing process. Importantly, the cumulative growth factor release kinetics are reminiscent of those observed in the nonphotopolymerizable hydrogel variety, which has been demonstrated in vitro and in vivo for induction of angiogenesis and vascularization.53–56,62

HA-HP delivery of AFS cells for wound healing treatment

During AFS cell delivery in hydrogels by bioprinting (Figure 4),60 UV irradiation photopolymerized the hydrogel almost instantaneously, consistently yielding a hydrogel that provided 100% coverage over the wound area and formed a tight but flexible seal with the skin at the edges of the excisional wound. As hypothesized, the rapid photopolymerization was useful in achieving a relatively uniform hydrogel over the wound bed.

FIGURE 4.

Photopolymerization of the hydrogel components supports rapid cell encapsulation and quick coverage of skin wounds with spatial control.

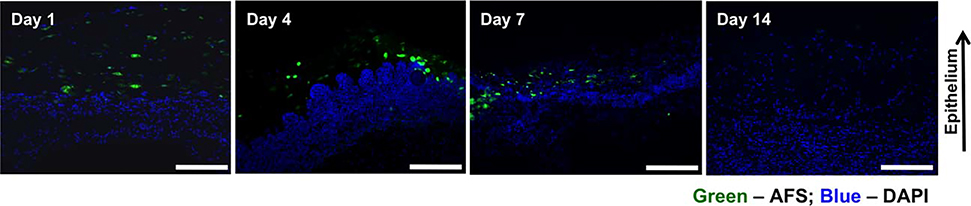

Fluorescent imaging of GFP-expressing AFS cells was carried out in order to track the cells in the regenerating skin tissue, following cell bioprinting (Figure 5). Consistent with our previous findings, skin samples from both groups harvested on day 1 after surgery possessed a large number of GFP-labeled cells were visible in the wounds of the AFS cell groups. This number appeared to decrease by over 50% by day 7. In tissues harvested on day 14 no GFP-labeled cells could be detected. The transient nature of the delivered cells is consistent with the many publications describing the therapeutic effects of cell therapy without long-term tissue integration.49,63–65

FIGURE 5.

Regenerating skin was harvested at days 1, 4, 7, and 14 in order to determine the presence of labeled cells. GFP-labeled AFS cells are visible in decreasing numbers of the time course of the experiment. Green: GFP-expressing AFS and blue: nuclear staining, DAPI.

Gross histology—wound closure, contraction, reepithelialization, and wound aspect ratio

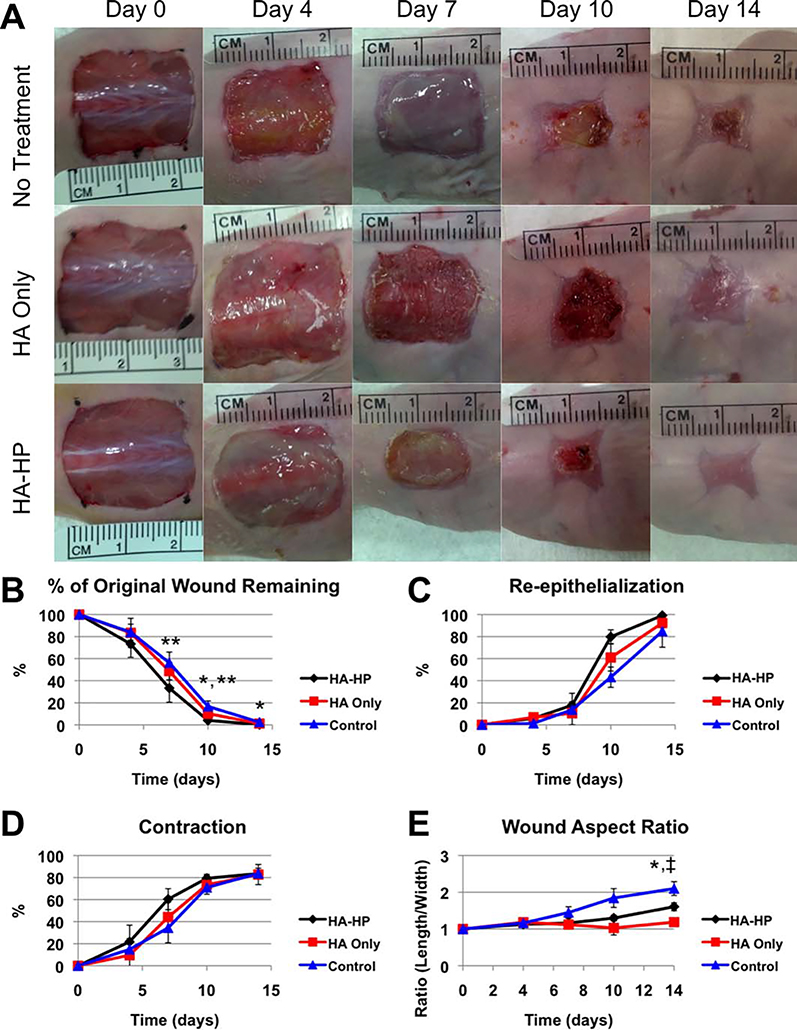

HA-HP-treated wounds closed more quickly, resulting in only 33.3, 4.0, and 0.2% of the original wound area remaining unhealed on days 7, 10, and 14, respectively [Figure 6(A,B)]. In comparison, HA-only-treated wounds had 47.8, 8.5, and 1.1% of the wounds remaining at those time points, and untreated control wounds had 56.3, 16.7, and 2.4% of the wounds remaining at those time points. Although even untreated mouse skin wounds heal quite rapidly, extrapolation of this improvement to chronic, large or nonhealing wounds in humans or large animals would translate into a significant acceleration of wound closure. HA-HP wounds also reepithelialized more quickly, reaching 79.8% reepithelialization at day 10 compared to 61.0% in HA-only wounds and 43.2% in control wounds [Figure 6(C)]. By day 14, HA-HP wounds had reached 99.2% reepithelialization compared to 92.4% in HA-only wounds and 84.9% in control wounds. Despite the clear trend in accelerated reepithelialization, these differences were not statistically significant. HA-HP wounds contracted more quickly than the other groups during the initial stages of the healing process [Figure 6(D)]. However, by day 14 HA-HP, HA-only, and control wounds had contracted nearly the same amount with no significant differences (83.5, 82.7, and 83.7% contractions, respectively). Interestingly, we observed a noticeable difference in wound aspect ratio. Specifically, we observed that the wounds treated with the HA-HP hydrogel (both HA-HP and HA-only) closed more uniformly, with similar wound dimensions in the anterior–posterior direction and media lateral direction. In the case of the control wounds, wounds closed in a nonuniform manner, resulting in an elongated wound in the anterior-posterior direction. At day HA-HP and HA-only wounds had aspect ratios of 1.6 and 1.2, respectively, which were significantly less than the aspect ratio of the control wounds, which was 2.1 [p < 0.05, Figure 6(E)]. This difference may prove notable, as the reported antifibrotic and antiscarring properties of HA66,67 may have an important role in preventing this nonuniform contraction.

FIGURE 6.

(A) Gross morphological images of the wounds over time indicate that AFS cells encapsulated in HA-HP accelerate wound closure. Quantification of gross morphology at days 0, 4, 7, 10, and 14: (B) percentage of the original wound remaining, (C) reepithelialized skin, (D) contraction, and (E) wound aspect ratio. *Significance (p < 0.05) between HA-HP and HA-only. **Significance (p < 0.05) between HA-HP and control. ‡Significance (p < 0.05) between HA-only and control.

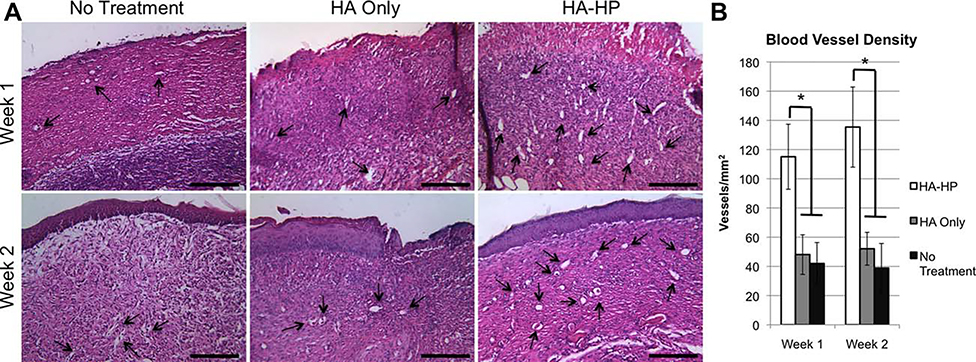

AFS-induced vascularization of regenerated skin

To assess the effects of AFS cells and secreted cytokines on angiogenesis, H&E-stained histological sections of regenerating skin tissues harvested at 1 and 2 weeks into the study were analyzed for the presence of blood vessels [Figure 7(A)]. MVD values were determined from the histological sections by ImageJ software [Figure 7(B)]. At both week 1 and week 2, MVD values in HA-HP-treated wounds were significantly greater than that of the no treatment control wounds and the HA-only-treated wounds (p < 0.01). This increased vascularization may be due to the presence of AFS cell-secreted growth factors, with sustained presence due to sequestration and release by the heparinized HA-HP hydrogel. In our previous study, we also documented increased vascularization activity in wounds treated with AFS cells and compiled a table of growth factors that the cells secrete, which included proangiogenic FGF and VEGF. Additionally, AFS cells have been shown to induce endothelial cell migration in vitro, via secretion of trophic factors.49

FIGURE 7.

(A) HA-HP treatments increase vascularization of the regenerating tissue as evidenced by H&E staining. (B) Quantification of blood vessel density. *p < 0.01.

Extracellular matrix components in regenerated skin

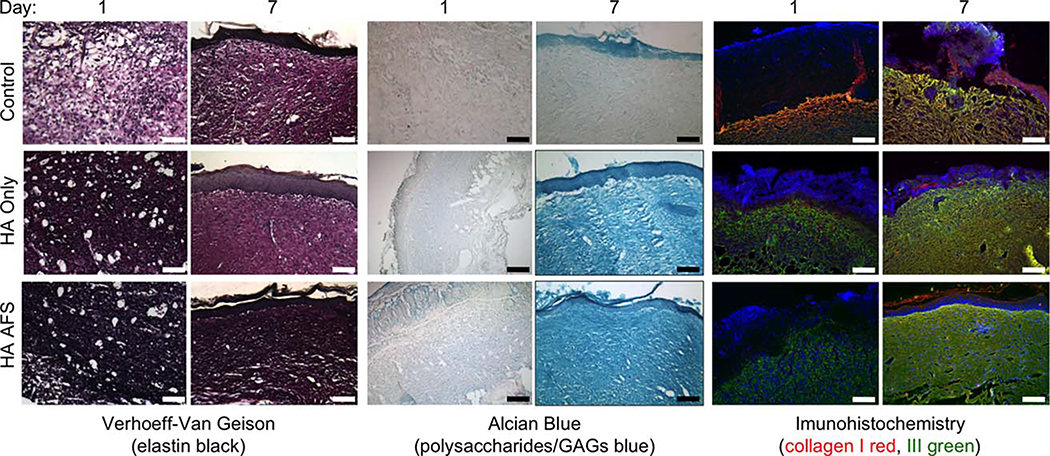

To assess the regeneration of the ECM, we used a series of histology stains to visualize elastin, GAGs, and proteoglycans, which are present in greater amounts in regenerated skin with less scarring. Increased relative ratios of these components to fibrotic collagen type I also result in skin that is more elastic and pliable, similar to normal undamaged skin. We then employed IHC antibody staining to look at collagen type I (Col I), associated with scarring, versus collagen type III (Col III), which is often present during healthy remodeling of damaged tissue.

At 1 week postsurgery (Figure 8), Verhoeff-Van Geison staining for elastin showed significantly more elastin staining in HA-HP-treated tissue. Alcian blue staining at 1 week showed deeper blue staining in both hydrogel treatments compared to controls, and deeper yet in HA-HP-treated tissues, indicating heightened levels of GAGs, which may be due to the presence of residual or incorporated HA hydrogel, but also production of new GAGs, as well as proteoglycans. Interestingly, the Col I and Col III IHC staining clearly showed a greater amount of staining for Col I in the HA-only tissues compared to the HA-HP tissues. Col III, on the other hand, was consistent through the groups. We suspect that the combinatorial treatment of AFS cells together with the HA-HP hydrogel may have been responsible for slowing Col I production while allowing cells to deposit other ECM materials resulting in a more balanced and healthy ECM composition. These observations were observed once again at 2 weeks postsurgery. At this time-point V-V elastin staining was notably darker in HA-HP tissues, suggesting an increased elastin deposition by the cells that had migrated into the wound and matrix. Alcian blue staining for GAGs and proteoglycans was stronger in both the HA-HP and HA-only groups compared to the control tissues. Some of this stain may be attributed the HA from the hydrogels that is now part of the new tissue. Nevertheless, this is a sign of healthy tissue, and is an argument for utilizing a hydrogel such as HA instead of collagen type I-based products. Lastly, the Col I and Col III stains revealed the same results as in week 1; fibrotic Col I appeared the least in HA-HP-treated tissues, while Col III stains appeared relatively similar across groups. The relative intensities of each stain do suggest that the HA-HP-treated tissues may contain a more balanced set of ECM components more indicative of normal skin, which potentially contributed to the faster wound closure, rather than nonhealing tissue or scar tissue.

FIGURE 8.

HA-HP treatments result in a more balanced set of ECM components. Verhoeff-Van Geison staining of elastin (black); alcian blue staining of proteoglycans and GAGs (blue); and collagen type I (red), collagen type III (green), and DAPI (blue) at (A) day 7 and (B) day 14. It appears that the combination treatment of HA-HP gels and AFS cells slows fibrotic collagen type I formation, allowing other important ECM components to be secreted by cells during tissue regeneration.

DISCUSSION

Despite countless advances in biomaterial science in recent years, the majority of biomaterials employed in wound healing therapy remain inadequate, failing either due to difficulties in administration and delivery, biocompatibility, or inefficiency in acting as an optimal delivery vehicle for biologicals such as cells or cytokines. Many materials that have slow gelation kinetics (collagen, nonphotopolymerizable varieties of the HA gel employed here; Matrigel) results in the materials to sluff off of the wound before cross-linking in place. In fact, this was one of the limitations we found using a fibrin-collagen blend in previous wound healing work.49 Rapid, on-demand gelation by thiol–ene photopolymerization solves this problem. Additionally, the formulation of hydrogel described here mirrors that of the nonphotopolymerizable hydrogel variety that has been employed in a wide variety of cell-based applications, showing high cell viability in static cultures7 as well as after being extruded/delivered through a bioprinting device,12,15 suggesting that this system is appropriate as a vehicle for cell therapy applications.

We hypothesized that delivering AFS cells within a UV cross-linkable HA-HP hydrogel, specifically tailored for wound healing applications, would be result in an effective therapy to treat full thickness wounds in an animal model. These cells have been shown previously to be multipotent, capable of secreting potent trophic factors, and highly expandable.23,49 Interestingly, these AFS cell populations have been shown to have extensive self-renewal properties. They do not undergo sensescence as many other primary cells do, maintaining long telomeres for many passages. The reason why this is the case is believed to be due these populations of AFS cells representing an intermediate stage between pluripotent embryonic stem cells and more lineage and passage restricted adult stem and progenitor cells. This hypothesis is somewhat supported by the fact that the AFS populations employed in our research have the presence of a Y chromosome, indicating that the cells’ origin is from the developing fetus rather than the mother. These cells therefore come from a fetal origin, rather than an adult origin, and as such maintain markers such as Oct4 that are often associated with pluripotent, self-renewing cells.23 As such, these cells could be potentially be expanded and banked for off-the-shelf regenerative therapies.

We hypothesized heparin-modulated extended release of AFS-secreted growth factors would likely increase angiogenesis and accelerate wound healing compared to other treatments. Additionally, by transitioning from a type I collagen-containing hydrogel we employed in the past,49 to an HA-based hydrogel tailored for cell delivery, we hypothesized that there may be impacts on the ECM formation during regeneration due to degradation and remodeling, and the anti-inflammatory nature of HA. Type I collagen is one of the primary components of scar tissue, and it’s delivery to wounds may be detrimental for the normal regeneration of functional skin. Additionally, from a surgery logistics perspective, the ability to deliver and polymerize the hydrogel on demand within the open wound is an improvement over hydrogels that require longer times to fully cross-link in place.

The cross-linker assessment on BSA release and the HA-HP versus HA growth factor assessment on growth factor release kinetics allows us to optimize the hydrogel system for the specific application of a 2-week wound healing experiment. By modulating cross-linking density and porosity through simply changing the cross-linker geometry (and leaving the HA and gelatin components constant) we could manipulate protein release through physical means. The looser cross-linking density of the linear cross-linked HA gels allowed delivery more protein during the study duration, which was our objective for the upcoming wound healing study. By including the covalently bound heparin component, we could also improve release of heparin-binding growth factors that were secreted by the encapsulated AFS cells. While the magnitude of the HA and HA-HP growth factor release curves do not differ greatly. The HA hydrogels stopped releasing growth factor after about 1 week. On the other hand, the HA-HP hydrogels, with growth factor sequestration and slow release, continued to release small, but physiologically relevant, amounts of growth factor throughout the study. As such, the HA-HP hydrogels cross-linked using the linear cross-linker were chosen as the optimal vehicle for the wound healing study. It should be noted, however, that based on these experiments, we believe that we can formulate a variety of hydrogel systems in which we can control the long-term release kinetics of the hydrogel, allowing us to deploy this system in other applications that might benefit from longer release profiles (>2 weeks).

The short-term presence of delivered cells has not reduced the clinical application of cellular therapies, and in fact, the decreased the risks of unwanted tumorigenic behavior, rejection, and other risks associated with foreign tissue transplantation has assisted with regulatory approval and clinical translation of many new cell therapies. Together with the protein, FGF, and VEGF release data shown above, this in vivo study illustrates the importance of implementing the HA-HP hydrogel, which supports extended release of AFS-secreted cytokines by heparin-associated sequestration. A potential alternative to treating wounds with AFS cells would be to load the hydrogel with these documented growth factors. However, these cytokines are expensive; it is likely less expensive to incorporate the cells versus incorporating a discrete panel of growth factors that may not fully comprise the cell-secreted combination and concentrations. Furthermore, living cells are capable of responding to environmental stimuli, thus potentially producing appropriate types and concentrations of factors during different phases of wound healing.

In addition to investigating the effect of AFS cells on overall wound closure and vascularization of regenerating tissue, we had hypothesized that a combination of AFS cells together with HA-HP might result in differences in the ECM during the healing and remodeling process. ECM in healthy skin contains a distribution of organized collagens, GAGs such as HA, and elastin. ECM in scarred skin contains an increased bias toward type I collagen in a more disorganized orientation. Interestingly, it has been widely demonstrated that in fetal skin, which heals without scarring, that HA is present in increased concentrations in the ECM. Additionally, it has been shown that the presence of increased vascularization limits formation of fibrotic tissue in various environments. Conversely, in damaged tissues with poor vascularization, severe fibrosis can occur.68,69 As our treatment combined a HA-based material with proangiogenic AFS cells, we hypothesized that our treatment would result in the formation of healthy ECM.

We believe that slowing collagen type I formation in relation to collagen type III deposition may result in reduced scarring in the long term. Additional research with larger animal models will be necessary to test this speculation. This hypothesis would be in line with research that has demonstrated increased type III versus type I collagen in normal fetal skin versus normal adult skin, as well as fetal granulation tissue versus adult granulation tissue.70 The wound treatment using the heparinized photopolymerizable hydrogel to deliver paracrine factor-secreting AFS cells may result in a more fetal-like environment during skin regeneration. This would be immensely beneficial, as there is widespread documentation of wound healing in fetuses occurring more efficiently and scar free,71,72 characteristics that would be in high demand for wound healing in adults.

CONCLUSION

These results illustrate that an appropriate delivery vehicle is essential for the effectiveness of cellular therapy to promote wound healing in patients with skin wounds or burns. The combinatorial therapy consisting of heparinized HA hydrogel and AFS cells presented here may have the potential to address the clinical need for more effective treatment of burns and skin wounds. The thiol–ene photopolymerization mechanism allows fast and accurate coverage of the wound and cell delivery, while control over the hydrogel cross-linking density and porosity through modulating cross-linker geometry and incorporation of heparin pendant chains plays an active role in the healing process by supporting GF release and prolonging paracrine effects despite the transient nature of the delivered cells. We found that the deposition of the HA-HP hydrogel containing AFS cells accelerated closure of full thickness wounds in mice faster than HA-only hydrogels and treatment-free controls, induced increased vascularization, and resulted in the formation of ECM with evidence of a variety of important ECM components, more like healthy skin. This ECM composition—increased levels of elastin, GAGs, and proteoglycans, and decreased relative expression of Col I—suggests that the regenerated skin may be more pliable and elastic in nature, similar to undamaged skin. Taken together, our results demonstrate that cell therapy effectiveness for wound healing can be significantly improved by optimizing the hydrogel delivery vehicle employed. This technology is currently being explored in large animal porcine models with the goal of translation to humans.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Contract grant sponsor: Armed Forces Institute for Regenerative Medicine ET-1

Contract grant sponsor: The State of North Carolina

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fraser JR, Laurent TC, Laurent UB. Hyaluronan: its nature, distribution, functions and turnover. J Intern Med 1997;242(1):27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Toole BP. Hyaluronan in morphogenesis. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2001;12(2):79–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burdick JA, Prestwich GD. Hyaluronic acid hydrogels for biomedical applications. Adv Mater 2011;23(12):H41–H56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allison DD, Grande-Allen KJ. Review. Hyaluronan: A powerful tissue engineering tool. Tissue Eng 2006;12(8):2131–2140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prestwich GD, Kuo JW. Chemically-modified HA for therapy and regenerative medicine. Curr Pharm Biotechnol 2008;9(4):242–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prestwich GD, Skardal A, Zhang J. Modified macromolecules and methods of making and using thereof. 2011. European patent EP2399940 A2. 2012. Dec 18. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang J, Skardal A, Prestwich GD. Engineered extracellular matrices with cleavable crosslinkers for cell expansion and easy cell recovery. Biomaterials 2008;29(34):4521–4531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu Y, Skardal A, Shu XZ, Prestwich GD. Prevention of peritendinous adhesions using a hyaluronan-derived hydrogel film following partial-thickness flexor tendon injury. J Orthop Res 2008;26(4): 562–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu Y, Shu XZ, Prestwich GD. Tumor engineering: orthotopic cancer models in mice using cell-loaded, injectable, cross-linked hyaluronan-derived hydrogels. Tissue Eng 2007;13(5):1091–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Serban MA, Scott A, Prestwich GD. Use of hyaluronan-derived hydrogels for three-dimensional cell culture and tumor xenografts. Curr Protoc Cell Biol 2008;Chapter 10:Unit 10.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu Y, Cai S, Shu XZ, Shelby J, Prestwich GD. Release of basic fibroblast growth factor from a crosslinked glycosaminoglycan hydrogel promotes wound healing. Wound Repair Regen 2007; 15(2):245–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skardal A, Zhang J, Prestwich GD. Bioprinting vessel-like constructs using hyaluronan hydrogels crosslinked with tetrahedral polyethylene glycol tetracrylates. Biomaterials 2010;31(24):6173–6181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Skardal A, Zhang J, McCoard L, Xu X, Oottamasathien S, Prestwich GD. Photocrosslinkable hyaluronan-gelatin hydrogels for two-step bioprinting. Tissue Eng A 2010;16(8):2675–2685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skardal A, Devarasetty M, Kang HW, Mead I, Bishop C, Shupe T, Lee SJ, Jackson J, Yoo J, Soker S, Atala A. A hydrogel bioink toolkit for mimicking native tissue biochemical and mechanical properties in bioprinted tissue constructs. Acta Biomater 2015;25: 24–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skardal A, Zhang J, McCoard L, Oottamasathien S, Prestwich GD. Dynamically crosslinked gold nanoparticle–hyaluronan hydrogels. Adv Mater 2010;22(42):4736–4740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murphy SV, Skardal A, Atala A. Evaluation of hydrogels for bioprinting applications. J Biomed Mater Res A 2013;101(1):272–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cherry DK, Hing E, Woodwell DA, Rechtsteiner EA. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2006 summary. Natl Health Stat Rep 2008(3):1–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pitts SR, Niska RW, Xu J, Burt CW. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2006 emergency department summary. Natl Health Stat Rep 2008(7):1–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kurd SK, Hoffstad OJ, Bilker WB, Margolis DJ. Evaluation of the use of prognostic information for the care of individuals with venous leg ulcers or diabetic neuropathic foot ulcers. Wound Repair Regen 2009;17(3):318–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sen CK, Gordillo GM, Roy S, Kirsner R, Lambert L, Hunt TK, Gottrup F, Gurtner GC, Longaker MT. Human skin wounds: A major and snowballing threat to public health and the economy. Wound Repair Regen 2009;17(6):763–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abdulrazzak H, De Coppi P, Guillot PV. Therapeutic potential of amniotic fluid stem cells. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther 2013;8(2):117–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cananzi M, De Coppi P. CD117 (+) amniotic fluid stem cells: State of the art and future perspectives. Organogenesis 2012;8(3):77–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Coppi P, Bartsch G Jr., Siddiqui MM, Xu T, Santos CC, Perin L, Mostoslavsky G, Serre AC, Snyder EY, Yoo JJ, Furth ME, Soker S, Atala A. Isolation of amniotic stem cell lines with potential for therapy. Nat Biotechnol 2007;25(1):100–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Delo DM, De Coppi P, Bartsch G Jr., Atala A. Amniotic fluid and placental stem cells. Methods Enzymol 2006;419:426–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mirabella T, Hartinger J, Lorandi C, Gentili C, van Griensven M, Cancedda R. Proangiogenic soluble factors from amniotic fluid stem cells mediate the recruitment of endothelial progenitors in a model of ischemic fasciocutaneous flap. Stem Cells Dev 2012; 12(12):2179–2188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun H, Feng K, Hu J, Soker S, Atala A, Ma PX. Osteogenic differentiation of human amniotic fluid-derived stem cells induced by bone morphogenetic protein-7 and enhanced by nanofibrous scaffolds. Biomaterials 2010;31(6):1133–1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murphy SV, Atala A. Amniotic fluid and placental membranes: unexpected sources of highly multipotent cells. Sem Reprod Med 2013;31(1):62–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Minagawa T, Imamura T, Igawa Y, Aizawa N, Ishizuka O, Nishizawa O. Differentiation of smooth muscle cells from human amniotic mesenchymal cells implanted in the freeze-injured mouse urinary bladder. European urology 2010;58(2):299–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murphy S, Lim R, Dickinson H, Acharya R, Rosli S, Jenkin G, Wallace E. Human amnion epithelial cells prevent bleomycin-induced lung injury and preserve lung function. Cell Transplant 2011;20(6):909–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murphy SV, Shiyun SC, Tan JL, Chan S, Jenkin G, Wallace EM, Lim R. Human amnion epithelial cells do not abrogate pulmonary fibrosis in mice with impaired macrophage function. Cell Transplant 2012;21(7):1477–1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carraro G, Perin L, Sedrakyan S, Giuliani S, Tiozzo C, Lee J, Turcatel G, De Langhe SP, Driscoll B, Bellusci S, Minoo P, Atala A, De Filippo RE, Warburton D. Human amniotic fluid stem cells can integrate and differentiate into epithelial lung lineages. Stem Cells 2008;26(11):2902–2911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hodges RJ, Jenkin G, Hooper SB, Allison B, Lim R, Dickinson H, Miller SL, Vosdoganes P, Wallace EM. Human amnion epithelial cells reduce ventilation-induced preterm lung injury in fetal sheep. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012;206(5):448.e8–448.e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hodges RJ, Lim R, Jenkin G, Wallace EM. Amnion epithelial cells as a candidate therapy for acute and chronic lung injury. Stem Cells Int 2012;2012:709763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murphy SV, Lim R, Heraud P, Cholewa M, Le Gros M, de Jonge MD, Howard DL, Paterson D, McDonald C, Atala A, Jenkin G, Wallace EM. Human amnion epithelial cells induced to express functional cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. PLoS One 2012;7(9):e46533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vosdoganes P, Hodges RJ, Lim R, Westover AJ, Acharya RY, Wallace EM, Moss TJ. Human amnion epithelial cells as a treatment for inflammation-induced fetal lung injury in sheep. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011;205(2):156.e26–156.e33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vosdoganes P, Wallace EM, Chan ST, Acharya R, Moss TJ, Lim R. Human amnion epithelial cells repair established lung injury. Cell Transplant 2013;22(8):1337–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Furth ME, Atala A. Stem cell sources to treat diabetes. J Cell Biochem 2009;106(4):507–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwartz RE, Reyes M, Koodie L, Jiang Y, Blackstad M, Lund T, Lenvik T, Johnson S, Hu WS, Verfaillie CM. Multipotent adult progenitor cells from bone marrow differentiate into functional hepatocyte-like cells. J Clin Invest 2002;109(10):1291–1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Manuelpillai U, Lourensz D, Vaghjiani V, Tchongue J, Lacey D, Tee JY, Murthi P, Chan J, Hodge A, Sievert W. Human amniotic epithelial cell transplantation induces markers of alternative macrophage activation and reduces established hepatic fibrosis. PLoS One 2012;7(6):e38631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shaw SW, David AL, De Coppi P. Clinical applications of prenatal and postnatal therapy using stem cells retrieved from amniotic fluid. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2011;23(2):109–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perin L, Sedrakyan S, Giuliani S, Da Sacco S, Carraro G, Shiri L, Lemley KV, Rosol M, Wu S, Atala A, Warburton D, De Filippo RE. Protective effect of human amniotic fluid stem cells in an immunodeficient mouse model of acute tubular necrosis. PloS one 2010;5(2):e9357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tajiri N, Acosta S, Glover LE, Bickford PC, Jacotte Simancas A, Yasuhara T, Date I, Solomita MA, Antonucci I, Stuppia L, Kaneko Y, Borlongan CV. Intravenous grafts of amniotic fluid-derived stem cells induce endogenous cell proliferation and attenuate behavioral deficits in ischemic stroke rats. PLoS One 2012;7(8): e43779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu YH, Vaghjiani V, Tee JY, To K, Cui P, Oh DY, Manuelpillai U, Toh BH, Chan J. Amniotic epithelial cells from the human placenta potently suppress a mouse model of multiple sclerosis. PLoS One 2012;7(4):e35758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rehni AK, Singh N, Jaggi AS, Singh M. Amniotic fluid derived stem cells ameliorate focal cerebral ischaemia–reperfusion injury induced behavioural deficits in mice. Behav Brain Res 2007; 183(1):95–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wei JP, Zhang TS, Kawa S, Aizawa T, Ota M, Akaike T, Kato K, Konishi I, Nikaido T. Human amnion-isolated cells normalize blood glucose in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. Cell Transplant 2003;12(5):545–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bollini S, Cheung KK, Riegler J, Dong X, Smart N, Ghionzoli M, Loukogeorgakis SP, Maghsoudlou P, Dube KN, Riley PR, Lethgoe MF, De Coppi P. Amniotic fluid stem cells are cardioprotective following acute myocardial infarction. Stem Cells Dev 2011;20(11): 1985–1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Delo DM, Olson J, Baptista PM, D’Agostino RB, Jr., Atala A, Zhu JM, Soker S. Non-invasive longitudinal tracking of human amniotic fluid stem cells in the mouse heart. Stem Cells Dev 2008; 17(6):1185–1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.National Institutes of Health. A multi-center study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of intravenous infusion of human placentaderived cells (PDA001) for the treatment of adults with moderateto-severe Crohn’s disease. In: ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US). 2011. [cited 2016 Jun 20]. Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01155362 NLM Identifier: NCT01155362. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Skardal A, Mack D, Kapetanovic E, Atala A, Jackson JD, Yoo J, Soker S. Bioprinted amniotic fluid-derived stem cells accelerate healing of large skin wounds. Stem Cells Transl Med 2012;1(11): 792–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Campo GM, Avenoso A, Campo S, D’Ascola A, Traina P, Sama D, Calatroni A. Glycosaminoglycans modulate inflammation and apoptosis in LPS-treated chondrocytes. J Cell Biochem 2009; 106(1):83–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Oottamasathien S, Jia W, McCoard L, Slack S, Zhang J, Skardal A, Job K, Kennedy TP, Dull RO, Prestwich GD. A murine model of inflammatory bladder disease: Cathelicidin peptide induced bladder inflammation and treatment with sulfated polysaccharides. J Urol 2011;186(4 Suppl):1684–1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang J, Xu X, Rao NV, Argyle B, McCoard L, Rusho WJ, Kennedy TP, Prestwich GD, Krueger G. Novel sulfated polysaccharides disrupt cathelicidins, inhibit RAGE and reduce cutaneous inflammation in a mouse model of rosacea. PLoS One 2011;6(2): e16658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Elia R, Fuegy PW, VanDelden A, Firpo MA, Prestwich GD, Peattie RA. Stimulation of in vivo angiogenesis by in situ crosslinked, dual growth factor-loaded, glycosaminoglycan hydrogels. Biomaterials 2010;31(17):4630–4638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hosack LW, Firpo MA, Scott JA, Prestwich GD, Peattie RA. Microvascular maturity elicited in tissue treated with cytokine-loaded hyaluronan-based hydrogels. Biomaterials 2008;29(15):2336–2347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Peattie RA, Rieke ER, Hewett EM, Fisher RJ, Shu XZ, Prestwich GD. Dual growth factor-induced angiogenesis in vivo using hyaluronan hydrogel implants. Biomaterials 2006;27(9):1868–1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pike DB, Cai S, Pomraning KR, Firpo MA, Fisher RJ, Shu XZ, Prestwich GD, Peattie RA. Heparin-regulated release of growth factors in vitro and angiogenic response in vivo to implanted hyaluronan hydrogels containing VEGF and bFGF. Biomaterials 2006; 27(30):5242–5251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Riley CM, Fuegy PW, Firpo MA, Shu XZ, Prestwich GD, Peattie RA. Stimulation of in vivo angiogenesis using dual growth factor-loaded crosslinked glycosaminoglycan hydrogels. Biomaterials 2006;27(35):5935–5943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Skardal A, Devarasetty M, Soker S, Hall AR. In situ patterned micro 3D liver constructs for parallel toxicology testing in a fluidic device. Biofabrication 2015;7(3):031001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Skardal A, Devarasetty M, Kang HW, Mead I, Bishop C, Shupe T, Lee SJ, Jackson J, Yoo J, Soker S, Atala A. A hydrogel bioink toolkit for mimicking native tissue biochemical and mechanical properties in bioprinted tissue constructs. Acta Biomater 2015;25: 24–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yoo JJ, Atala A, Binder KW, Zhao W, Dice D, Xu T. Delivery system. U.S. patent US 2011/0172611 A1 (2011).

- 61.Deegan DB, Zimmerman C, Skardal A, Atala A, Shupe TD. Stiffness of hyaluronic acid gels containing liver extracellular matrix supports human hepatocyte function and alters cell morphology. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 2015;55:87–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Peattie RA, Nayate AP, Firpo MA, Shelby J, Fisher RJ, Prestwich GD. Stimulation of in vivo angiogenesis by cytokine-loaded hyaluronic acid hydrogel implants. Biomaterials 2004;25(14):2789–2798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Burst VR, Gillis M, Putsch F, Herzog R, Fischer JH, Heid P, Muller-Ehmsen J, Schenk K, Fries JW, Baldamus CA, Benzing T. Poor cell survival limits the beneficial impact of mesenchymal stem cell transplantation on acute kidney injury. Nephron Exp Nephrol 2010;114(3):e107–e116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wei HM, Wong P, Hsu LF, Shim W. Human bone marrow-derive dadult stem cells for post-myocardial infarction cardiac repair: Current status and future directions. Singapore Med J 2009;50(10): 935–942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Meirelles Lda S, Fontes AM, Covas DT, Caplan AI. Mechanisms involved in the therapeutic properties of mesenchymal stem cells. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2009;20(5–6):419–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Edward M, Quinn JA, Sands W. Keratinocytes stimulate fibroblast hyaluronan synthesis through the release of stratifin: A possible role in the suppression of scar tissue formation. Wound Repair Regen 2011;19(3):379–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hu M, Sabelman EE, Cao Y, Chang J, Hentz VR. Three-dimensional hyaluronic acid grafts promote healing and reduce scar formation in skin incision wounds. J Biomed Mater Res B: Appl Biomater 2003;67(1):586–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ebrahimi B, Eirin A, Li Z, Zhu XY, Zhang X, Lerman A, Textor SC, Lerman LO. Mesenchymal stem cells improve medullary inflammation and fibrosis after revascularization of swine atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis. PLoS One 2013;8(7):e67474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chiu LL, Reis LA, Momen A, Radisic M. Controlled release of thymosin beta4 from injected collagen-chitosan hydrogels promotes angiogenesis and prevents tissue loss after myocardial infarction. Regen Med 2012;7(4):523–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Merkel JR, DiPaolo BR, Hallock GG, Rice DC. Type I and type III collagen content of healing wounds in fetal and adult rats. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 1988;187(4):493–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.West DC, Shaw DM, Lorenz P, Adzick NS, Longaker MT. Fibrotic healing of adult and late gestation fetal wounds correlates with increased hyaluronidase activity and removal of hyaluronan. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 1997;29(1):201–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sancho MA, Julia V, Albert A, Diaz F, Morales L. Effect of the environment on fetal skin wound healing. J Pediatr Surg 1997; 32(5):663–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.