Abstract

Background

Telemonitoring (TM), mobile-phone technology for health, and bluetooth-enabled self-monitoring devices represent innovative solutions for proper glycemic control, compliance and monitoring, and access to providers.

Objective

In this study, we evaluated the impact of TM devices on glycemic control and the compliance of 38 previously lost-to-follow-up (LTFU) patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).

Methods

This was an interventional single-center study that randomly recruited LTFU patients from the Dubai Diabetes Center (DDC), UAE. After contact and recruitment by phone, patients had an initial visit at which they were provided with home-based TM devices. A follow-up visit was conducted three months later.

Results

The mean HbA1c decreased significantly from 10.3 ± 1.9% at baseline to 7.4 ± 1.5% at the end of follow-up, with a mean difference (MD) of −2.9% [95% CI: −3.6 to −2.2]. The percentage of patients with HbA1c <7% was 50% after three months. Home-based blood sugar monitor devices showed a significant reduction in fasting blood glucose (FBG) after three months (MD = -40.1 mg/dL, 95% CI: −70.8 to −9.3). A significant reduction was observed in terms of body weight after three months (MD = −1.3 kg, 95% CI: −2.5 to −0.08). The mean number of days the participants used a device was the highest for portable pill dispensers (86.5 ± 22.8 days), followed by a OneTouch® blood glucose monitor (72.9 ± 23.5 days).

Conclusions

TM led to significant improvements in overall diabetes outcomes, including glycemic control and body weight, indicating its effectiveness in a challenging population of T2DM patients who had previously been lost to follow-up.

1. Introduction

In the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, diabetes affects 55 million people, with a notably higher prevalence (12.8%) than the global average (nearly 9.3%) in 2019 [1]. After Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) has one of the highest diabetes burdens in the Middle East (16.3%) [1–3]. Although several well-established behavioral and therapeutic interventions exist for diabetes, patient outcomes are still poor, with a high incidence of diabetes-related complications [4, 5]. Diabetes-related complications can be prevented or delayed with intensive glucose control. Nevertheless, up to 60%–78.2% of adult patients with diabetes in the MENA region are inadequately controlled [6–9]. In UAE, a five-year retrospective study noted that only 37.7% of the population with diabetes in Dubai had HbA1c <7% [9]. Generally, inadequate home blood glucose (BG) monitoring, nonadherence with medications or recommended lifestyle behaviors (nutrition and exercise), suboptimal patient education about the disease, and limited access to health experts are all factors that may lead to suboptimal BG control [10, 11]. Loss-to-follow-up (LTFU) is one of the primary drivers of poor diabetes outcomes in well-resourced countries [12, 13]. Patients are more likely to achieve adequate glucose control if they attend their scheduled visits; nonetheless, data from the MENA region highlight that a considerable proportion of patients with diabetes do not follow the recommended appointment schedules with their physicians [14, 15].

Therefore, several researchers proposed the application of telemedicine, including telemonitoring (TM) and teleconsultation, to optimize and improve the management of patients with T2DM. The cumulative body of evidence highlights that the application of telemedicine results in committed patients, which may improve glycemic control and reduce the need for hospital admissions [16]. Telemedicine and mobile-phone technology for health (mHealth), along with Bluetooth-enabled self-monitoring devices, can be effective solutions for educational challenges, compliance and monitoring, and access to providers [17]. BG control could be enhanced safely by adjusting drugs based on home BG readings reported to clinicians remotely [18]. Telemedicine can also be an efficient way to monitor diabetes complications, particularly macrovascular problems and comorbidities (e.g., arterial hypertension) [17]. The high penetration of mobile phones in most countries enables health programs and providers to engage with large numbers of patients directly. This can allow for monitoring patient health outcomes and adherence to medication and treatment regimens at the national, city, and individual levels with TM devices connected through mobile phones [19].

The necessity for the application of telemedicine has been widely recognized following the emergence of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. People with diabetes are classified as a high-risk group for severe COVID-19 illness and are advised to maintain social distancing measures [20]. These measures have negatively impacted the access of patients to healthcare providers [21]. For a chronic disease such as diabetes that requires careful BG monitoring along with recurrent physician consultation, telemedicine can be a viable alternative for patients seeking medical guidance without physical attendance to the clinics and increasing their risk of COVID-19 infection. Telemedicine represents a valuable tool for remote patient consultation and early recognition of possible diabetes complications, signs of blood glucose dysregulation, and infection [22].

This study aimed to evaluate the impact of TM devices, including home BG and vital signs monitoring devices, on the glycemic control and the compliance of previously LTFU patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).

2. Methods

We confirm that none of the study's procedures violated the principles of the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki [23] and applicable local laws. The central institutional review board (IRB) of Dubai Health Authority, Dubai, UAE, approved the study protocol (DSREC-09/2019-06).

2.1. Study Design and Patients

The present study was an interventional, single-center, prospective trial, which was conducted at the DDC, Dubai, UAE. We recruited adult patients (aged ≥18 years) with an established diagnosis of T2DM and HbA1c >8% at the time of the study's initiation. Only patients who had missed their appointments for more than one year before the study's initiation were included. Patients who were familiar with the use of technology (self or dedicated family member) and provided written informed consent were included. We excluded patients receiving care primarily outside DDC, pregnant women or women who planned to become pregnant within six months from the study's initiation, and patients participating in any other clinical trial.

The study' investigators retrospectively reviewed the Dubai Diabetes Center (DDC) databases to select patients with T2DM lost to follow-up at their clinics. The study nurse contacted these subjects via phone call to check for eligibility and willingness to participate in the study and undergo a screening visit. A follow-up visit was conducted after three months, at the end of the study period.

2.2. Data Collection and TM Devices

At the initial study visit, the following data were collected from all eligible patients: demographics, medical history, history of previous medications, current medications (dosages and frequencies), body weight, vital signs, spirometry measurements, glycemic parameters, hemoglobin level, lipid profile, renal function tests, and urine analysis. All patients were provided with TM devices for home use. These included a OneTouch Select Plus Flex® blood glucose monitor (LifeScan Inc, Malvern, PA USA), electronic sphygmomanometer (Cognitive Healthcare International [CHI], European approval, CE mark), heart rate monitor and pulse oximeter (CHI, European approval, CE mark), and portable pill dispenser (CHI, European approval, CE mark). All patients were also provided with a dedicated phone with data connectivity only, which had the CHI app preloaded. Standardized training was provided to the patient on the use of the phone and CHI app.

Data from the CHI app were collected automatically, and the required responses were communicated back to the patient by clinic staff via a dedicated laptop. If the dedicated staff was away from the laptop, the data were available through their CHI app. Similarly, the study's investigators had the data available on their CHI app. Patients were instructed to complete daily data entry in their CHI app for three months. Patients were contacted for reminders or advice, as needed, based on the readings received from all of their TM devices.

At the center, the following devices were used at the screening and follow-up visits: BAYER DCA to test HbA1c (Vantage Siemens Healthcare, Bayer Diagnostics), portable electrocardiography (ECG) machine (CHI, European approval, CE mark), pulmonary function testing spirometer (CHI, European approval, CE mark), blood testing analyzer (CHI, European approval, CE mark), portable urine analyzer (CHI, European approval, CE mark), and weighing scale (CHI, European approval, CE mark). The incidence of adverse events was recorded throughout the study period.

2.3. Study Outcomes

The primary outcome was to assess the mean change from baseline in the HbA1c level after three months of use of TM devices. Additional outcomes measured included the three-month changes in fasting blood glucose (FBG) and random blood glucose (RBG), body weight, blood pressure, pulse rate, oxygen saturation, spirometer measurements, hemoglobin level, lipid profile, renal function tests, urine analysis, and ECG.

2.4. Sample Size Calculation and Statistical Analysis

According to estimates, this study needed 32 patients to detect an effect size of 0.5% between the average HbA1c at the final visit and the baseline visit using the two-sided paired t-test with 80% power and a 5% significance level. The effect size of 0.5% lies within the effect sizes reported by many studies, such as Yu et al. [24].

Data analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 24. Frequencies and percentages summarized categorical variables. Continuous variables were summarized by means and standard deviations (SDs) or median and interquartile range (IQRs) after checking the assumption of normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Data were presented with their 95% confidence interval (CI) for the estimate of the parameter, where applicable. Comparing two means was done using the Student's t-test for paired data. Comparing two categorical variables was done using the McNemar chi-square test. Spearman correlation was used to test the association between the change in HbA1c and the number of days glucose monitoring devices were used. No multivariate analyses were done for this study due to the small sample size. In the case of missing data, the denominator was reported in the body of the table. All statistical tests were two-sided. p values <0.05 were considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

A total of 38 patients were included with a mean age of 48.2 ± 10.1 years. Patients were predominately female (57.9%). All participants had underlying conditions other than diabetes, mainly vitamin D deficiency (94.7%), dyslipidemia (89.5%), obesity (71.1%), hypertension (60.5%), and chronic kidney disease (36.8%). Sixty-five percent of the patients had microalbuminuria, and 35.7% had proteinuria. Additionally, coronary artery diseases and neuropathy were recorded in 13.2% and 10.5% of the patients, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and medical history of the patients.

| Baseline characteristics | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 48.2 | 10.1 |

| Count | Percent | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 16 | 42.1 |

| Female | 22 | 57.9 |

| Medical history | ||

| Any medical history other than diabetes | 38 | 100 |

| Vitamin D deficiency | 36 | 94.7 |

| Dyslipidemia | 34 | 89.5 |

| Obesity | 27 | 71.1 |

| Hypertension | 23 | 60.5 |

| CKD | 14 | 36.8 |

| Microalbumin | 9 | 64.3∗ |

| Proteinuria | 5 | 35.7∗ |

| Hypothyroidism | 8 | 21.1 |

| Coronary artery disease | 5 | 13.2 |

| Neuropathy | 4 | 10.5 |

| Prior T2DM medications | Median | IQR |

| Number of medications | 2.0 | 3.00 |

| Class of medications | Count | Percent |

| Biguanides | 23 | 60.5 |

| DDP4 inhibitors | 21 | 55.3 |

| Insulin secretagogue | 15 | 39.5 |

| SGLT2 inhibitors | 11 | 28.9 |

| Insulin | 3 | 7.9 |

| GLP1 | 2 | 5.3 |

| Thiazolidinediones | 2 | 5.3 |

| Current T2DM medications | Median | IQR |

| Number of medications | 4.0 | 1.0 |

| Class of medications | Count | Percent |

| Biguanides | 36 | 94.7 |

| SGLT2 inhibitors | 34 | 89.5 |

| DDP4 inhibitors | 21 | 55.3 |

| Insulin secretagogue | 24 | 63.2 |

| Insulin | 22 | 57.9 |

| GLP1 | 18 | 47.4 |

| Thiazolidinediones | 2 | 5.3 |

| Alpha glucosidase inhibitor | 1 | 2.63 |

∗ The percentage was calculated for a total of 14 CKD patients.

Most of the patients were on multiple medications. The median number of prior antidiabetic medications taken since the patient was first diagnosed with diabetes was 2 (3). Biguanides were among the top prescribed medications in 60.5% of the population, followed by dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP4) inhibitors (55.3%) and insulin secretagogues (39.5%). Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors were used in 28.9% of the patients. In terms of current medications, the median number of antidiabetic medications at the time of entry into the study was 4 (3), with biguanides (94.7%) and SGLT2 inhibitors (89.5%) accounting for the majority of current medications (Table 1). A detailed map of each patient's prior and current medications is presented in Supplementary material 1.

3.2. The Changes in Glycemic Parameters

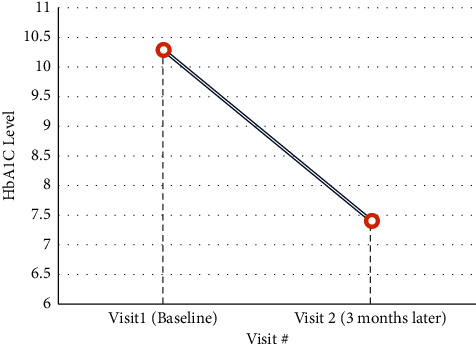

The mean HbA1c decreased significantly from 10.3 ± 1.9% at baseline to 7.4 ± 1.5% at the end of the third month of follow-up, with a mean difference (MD) of −2.9% [95% CI: −3.6 to −2.2, p < 0.001] (Figure 1). Overall, half of the patients (n = 19) achieved a HbA1c level of <7% after three months.

Figure 1.

Mean HbA1C level at baseline and after three months measured in the center.

The average paired FBG exhibited a significant reduction from the baseline to the end of follow-up (MD = −40.1 mg/dL, 95% CI: −70.8 to −9.3, p=0.013) when measured using home-based BG monitors (Table 2). The same finding was observed using the center-based lab testing (Table 3). On the other hand, the average paired RBG did not change significantly from the baseline to the end of follow-up (MD = −40.8 mg/dL, 95% CI: −84.7 to 3.2, p=0.067) (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Results of home-based devices of T2DM indicators at baseline and after three months.

| Clinical characteristics (mean ± SD) | N | Baseline | N | 3 months | N with both measures | Difference (95% CI) (3 months–baseline) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood glucose (mg/dL) | |||||||

| FBG | 26 | 192.2 (61.4) | 31 | 147.9 (40.3) | 20 | −40.1 (−70.8–−9.3) | 0.013 |

| RBG | 32 | 199.5 (66.4) | 25 | 171.3 (83.3) | 21 | −40.8 (−84.7–3.2) | 0.067 |

| Blood pressure (mmHg) | |||||||

| SBP | 37 | 135.4 (15.3) | 38 | 133.5 (15.1) | 37 | −2.2 (−7.2–2.8) | 0.386 |

| DBP | 37 | 85.7 (11.7) | 38 | 82.5 (9.4) | 37 | −3.5 (−6.6–−0.4) | 0.028 |

| Pulse rate (beats/min) | 37 | 82.7 (12.5) | 38 | 82.2 (15.4) | 37 | −0.7 (−4.5–3.1) | 0.710 |

| Oxygen saturation (%) | 38 | 97.4 (1.4) | 38 | 95.7 (12.7) | 38 | −1.8 (−5.9–2.4) | 0.393 |

FBG: fasting blood glucose; RBG: random blood glucose; SBP: systolic blood pressure; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; CI: confidence interval.

Table 3.

Results of center-based measures of T2DM indicators at baseline and after three months.

| Clinical characteristics (mean ± SD) | N | Baseline | N | 3 months | N with both measures | Difference (95% CI) 3 months–baseline | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bodyweight/Composition (mean ± SD) | |||||||

| Weight (kg) | 37 | 92.3 (19.8) | 37 | 90.9 (19.7) | 36 | −1.3 (−2.5–−0.08) | 0.037∗ |

| Fat percent (%) | 37 | 47.7 (10.5) | 33 | 47.7 (9.8) | 32 | −0.7 (−2.0–0.60) | 0.276 |

| Muscle percent (%) | 37 | 48.9 (9.8) | 33 | 48.9 (9.1) | 32 | 0.65 (−0.56–1.85) | 0.286 |

| Water percent (%) | 37 | 39.2 (7.4) | 33 | 39.1 (6.9) | 32 | 0.52 (−0.43–1.5) | 0.270 |

| Bone weight (kg) | 37 | 3.8 (4.3) | 33 | 3.1 (1.05) | 32 | −0.82 (−2.5–0.9) | 0.331 |

| Spirometry Measurement (mean ± SD) | |||||||

| FVC (L) | 36 | 2.2 (0.78) | 37 | 2.1 (0.73) | 35 | −0.04 (−0.28–0.2) | 0.768 |

| FEV1 (L) | 36 | 1.8 (0.78) | 37 | 1.8 (0.65) | 35 | −0.007 (−0.22–0.2) | 0.947 |

| PEF (L/S) | 36 | 4.8 (2.5) | 37 | 4.8 (2.5) | 35 | −0.13 (−0.9–0.6) | 0.727 |

| FEV1% | 36 | 84.6 (20.9) | 37 | 86.4 (17.1) | 35 | 1.04 (−8.2–10.3) | 0.821 |

| FEF25% | 36 | 4.0 (2.3) | 37 | 4.2 (2.2) | 35 | 0.05 (−0.7–0.8) | 0.907 |

| FEF75% | 36 | 1.9 (1.0) | 37 | 1.8 (0.94) | 35 | −0.11 (−0.3–0.1) | 0.313 |

| FEF25-75% | 36 | 3.0 (1.5) | 37 | 2.9 (1.6) | 35 | −0.09 (−0.5–0.4) | 0.683 |

| Blood Tests (mean ± SD) | |||||||

| FBG (mg/dl) | 26 | 192.2 (61.4) | 31 | 147.9 (40.3) | 20 | −40.1 (−70.8–−9.3) | 0.013∗ |

| RBG (mg/dl) | 32 | 199.5 (66.4) | 25 | 171.3 (83.3) | 21 | −40.8 (−84.7–3.2) | 0.067 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 35 | 13.5 (3.0) | 37 | 14.2 (2.0) | 34 | 0.6 (−0.24–1.5) | 0.148 |

| Uric acid (mg/dl) | 35 | 6.2 (3.0) | 37 | 6.3 (1.9) | 34 | 0.08 (−0.9–1.04) | 0.863 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 34 | 154.7 (31.9) | 37 | 134.5 (26.4) | 33 | −20.6 (−33.9–−7.3) | 0.003∗ |

| HDL-C (mg/dl) | 34 | 41.3 (15.7) | 37 | 43.4 (17.9) | 33 | 2.9 (−4.3–10.2) | 0.412 |

| LDL-C (mg/dl) | 32 | 87.5 (26.4) | 37 | 67.2 (22.99) | 31 | −18.4 (-29.5–−7.3) | 0.002∗ |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 34 | 128.9 (87.0) | 37 | 131 (77.0) | 33 | −9.0 (−37.3–19.2) | 0.520 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl) | 35 | 0.99 (0.4) | 37 | 1.17 (0.26) | 34 | 0.16 (−0.005–0.300) | 0.056 |

| Urine Tests (mean ± SD) | |||||||

| Glucose (μmol/L) | 37 | 33.6 (25.6) | 38 | 41.05 (23.8) | 37 | 7.0 (−2.2–16.3) | 0.131 |

| Bilirubin (μmol/L) | 37 | 10.0 (15.9) | 38 | 11.6 (17.3) | 37 | 1.9 (−5.9–9.6) | 0.628 |

| Specific gravity | 37 | 1.02 (0.008) | 38 | 1.02 (0.009) | 37 | 0. (−0.008–0.0) | 0.027∗ |

| Ketones (μmol/L) | 37 | 0.04 (0.25) | 38 | 0 | 37 | −0.04 (−0.12–0.04) | 0.324 |

| Occult blood (μmol/L) | 37 | 0 | 38 | 6.58 (40.6) | 37 | 6.7 (−6.9–20.5) | 0.324 |

| Proteins (μmol/L) | 37 | 0.34 (0.70) | 38 | 0.34 (0.62) | 37 | 0.007 (−0.25–0.26) | 0.955 |

| Urobilinogen (μmol/L) | 37 | 3.3 (0) | 38 | 3.2 (0.54) | 37 | −0.09 (−0.27–0.09) | 0.324 |

| Nitrites (μmol/L) | 37 | 0.49 (2.96) | 38 | 0 | 37 | −0.486 (−1.5–0.50) | 0.324 |

| Leukocytes (cells/μl) | 37 | 13.9 (82.2) | 38 | 0 | 37 | −13.9 (−41.3–13.5) | 0.310 |

| Vitamin C (μmol/L) | 37 | 0.016 (0.10) | 38 | 0.2 (0.93) | 37 | 0.19 (−0.13–0.5) | 0.235 |

| Ph | 37 | 5.95 (0.23) | 38 | 5.89 (0.4) | 37 | −0.05 (−0.19–0.08) | 0.422 |

| ECG measurement (%Normal) | — | ||||||

| P wave | 37 | 100 | 37 | 100 | — | ||

| PR interval | 37 | 100 | 37 | 100 | — | ||

| QRS complex | 37 | 100 | 37 | 100 | — | ||

| ST segment | 37 | 100 | 37 | 100 | — | ||

| T wave | 37 | 100 | 37 | 100 | — | ||

| QT interval | 37 | 100 | 37 | 100 | — | ||

3.3. Changes in Other Parameters

The home-based measurements revealed no significant changes in systolic blood pressure, pulse rate, and oxygen saturation across the three months of follow-up. On the other hand, the diastolic blood pressure significantly decreased at the end of follow-up (−3.5 mmHg, 95% CI −6.6 to −0.4, p=0.028) (Table 2).

The center-based measurements of body composition markers, including weight, fat percent, muscle percent, water percent, and bone weight, showed that only weight exhibited a significant reduction at the end of follow-up (MD = −1.3 kg, 95% CI: −2.5 to −0.08, p=0.037). Analysis showed nonsignificant changes between baseline and measures recorded at the 3-month visit in terms of forced vital capacity (FVC; p=0.768), forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1; p=0.947), peak expiratory flow (PEF; p=0.727), FEV1/FVC ratio (FEV1%; p=0.821), 25% flow of the FVC (FEF25; p=0.907), 75% flow of the FVC (FEF75; p=0.313), and average flow between 25% and 75% of the FVC (FEF25-75; p=0.683) (Table 3).

Laboratory testing showed a significant reduction in total cholesterol (MD = −20.6 mg/dL, 95% CI: −33.9 to −7.3, p=0.003) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C; MD = −18.4 mg/dL, 95% CI: −29.5 to −7.3 p=0.002) after three months, compared to baseline measures. Other blood tests did not show significant changes at the end of follow-up. Likewise, none of the urine analysis markers showed significant changes at the end of follow-up, except for specific gravity, which decreased significantly (MD = −0.004, 95% CI: −0.008 to −0.0005, p=0.027). All ECG measurements were normal at baseline and after three months (Table 3).

3.4. The Usability of Home-Based TM Devices

The mean number of days the participants used a device was the highest for portable pill dispensers, with a mean of 86.5 ± 22.8 days. The OneTouch® Select Plus Flex® BGM was the second most used device with a mean of 72.9 ± 23.5 days. The electronic sphygmomanometer was used for a mean of 62.3 ± 28.6 days, while the pulse oximeter was used for 50.4 ± 28.6 days (Table 4). The mean number of reminders per patient was 2952 ± 935.5. The Spearman correlation showed a weak negative association between the frequency of BG monitor use and change in HbA1c (r = −0.028, p=0.866).

Table 4.

Mean number of days the participants used home-based devices and required number of reminders needed.

| Home-based devices | Mean number of days used | SD | Median | IQR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OneTouch® select plus Flex® BGM | 72.9 | 23.5 | 79 | 40 |

| Electronic sphygmomanometer | 62.3 | 28.6 | 71 | 49 |

| Pulse oximeter | 50.4 | 28.6 | 47 | 39 |

| Portable pill dispenser | 86.5 | 22.8 | 91 | 19 |

| Number of reminders per patient | 2952 | 935.5 | 2837 | 1306 |

∗ SD: standard deviation.

3.5. Safety Outcomes

No adverse events were reported by the participants.

4. Discussion

The current international guidelines recommend routine consultations every three months for patients with T2DM, particularly for poorly controlled patients [25]. Nonetheless, many patients were reported to skip regular face-to-face consultations. The traditional consultation method is relatively time-consuming for health care professionals and patients and ineffectively supports patient self-management [26]. TM, where the patient measures their signs and symptoms at home and makes them electronically available to their healthcare provider, is an intervention requiring input from patients and providers [27]. Many countries have used various TM strategies to manage T2DM, depending on their clinical circumstances [28]. Recent reports from the MENA region highlighted raised awareness about the benefits of TM among the general population and their willingness to use it [29]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in the UAE that assessed the impact of TM on the management of patients with diabetes.

TM interventions, given via cellular phones and the Internet, have demonstrated their usefulness in multiple clinical trials in enhancing diabetes outcomes and lowering diabetes care costs [30]. Previous reports have shown that BG and blood pressure monitoring via TM of patients with T2DM was feasible and supported self-care and medical treatment decisions [31]. Nevertheless, health outcomes with diabetes TM systems have been varied, and a TM system by itself is unlikely to enhance outcomes [17]. The impact of TM systems varies depending on the level of patient engagement in diabetes self-management [32]. In the present study, we utilized a combination of various home- and clinic-based TM devices to ensure adequate monitoring of patients' statuses and prompt timely consultations and advice based on the readings received from these devices. Our findings demonstrated that TM was associated with a significant improvement in glycemic control after three months from the implementation of the TM system. Half of the patients achieved the targeted glycemic control at the end of follow-up.

Such findings are in good agreement with recent reports from different parts of the world. In the meta-analysis of Kim and his colleagues, a pooled analysis of 38 studies showed that TM was associated with a significant reduction in HbA1c levels of 6855 patients compared to usual care. This reduction was observed in the studies that monitored medication compliance, counseling, and education. In addition, they have demonstrated that the rate of achieving HbA1c <7% in the TM group was higher than usual care [33]. Lee et al. [34] conducted a randomized controlled trial that showed that TM (MyGlucoHealth, web-enabled glucometer) significantly reduced the HbA1c in a cohort of the population by a mean of 1.07% compared to only 0.24% in the usual care group (p < 0.01). Interestingly, they highlighted that compared with usual care, receiving TM was associated with a lower number of hypoglycemic events during Ramadan fasting and at the end of the study. Jeong et al. [35] reported a significant reduction in HbA1c among patients receiving TM devices for 24 weeks. The rate of patients who achieved HbA1c <7% was 33.9%. These findings suggest that TM could be used to encourage patients to acquire healthier habits. Thus, TM for diabetes management appears to help in the reduction of HbA1c levels through interventions that encourage the transmission of patient data, as well as regular and intensive feedback [36]. TM may be more beneficial in people with high HbA1c values, since TM can help patients modify their health behaviors such as diet and physical activity by monitoring them [37].

Metabolic control is a cornerstone in diabetes care and a significant modifier to the risks of diabetes-related complications. Alongside glycemic control, proper management of dyslipidemia, hypertension, and obesity is a well-established protective measure against the development of various micro- and macrovascular complications [38]. While recent decades have witnessed a paradigm shift towards antidiabetic medications with a beneficial impact on overall metabolic control [39], a considerable proportion of patients with T2DM from the MENA region still suffer from poor metabolic control [40]. Our results demonstrated that the TM devices led to significant reductions in blood pressure, body weight, and lipid profile among previously LTFU patients with T2DM. Notably, the reduction in the DBP was clinically relevant with a mean reduction of 3.5 mmHg; the Heart Outcome Prevention Evaluation (HOPE) study found that improvements in systolic and diastolic blood pressure of 3.3 and 1.4 mmHg, respectively, were associated with a 22% reduction in the relative risk of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke [41]. In concordance with our findings, a previous report demonstrated that TM led to a statistically significant reduction in SBP and body mass index (MD = −1.33 mmHg and −0.25 kg/m2, respectively) [33]. Similar results were demonstrated in previous reports [35]. However, although HbA1c and number of hypoglycemic events both improved, Lee et al. reported [34] that blood pressure, weight, diabetes distress, and diabetes self-efficacy showed no significant changes with their TM device.

Poor adherence to medication and BG monitoring schedules is a strong independent predictor of inadequate glycemic control in people with T2DM [42]. In this regard, various telehealth modalities were found to improve patients' adherence to antidiabetic medications [43], diabetes self-care [44], and, in return, overall glycemic control [45]. In the present study, we found that the application of the TM approach resulted in adequate patient compliance, as reflected by the high utilization of BG monitoring devices and portable pill dispensers over the study's period. Our findings run in parallel with the current body of evidence highlighting the beneficial role of telemedicine in the patients' adherence to diabetes self-care practices [44].

Despite the reported benefits of telemedicine during the COVID-19 crisis, especially in patients with diabetes, many barriers have been identified, including resistance to change, patient preference for face-to-face visits, concerns about patients' health literacy, and their ability to cope with telemedicine consultations [46]. For patients with diabetes, an additional concern is the potential difficulty of uploading device data independently [47]. The top barriers are technology-specific and could be overcome through training, change-management techniques, and interspersing delivery by telemedicine with personal patient-to-provider interactions [46]. Therefore, it is essential to provide mass awareness campaigns to educate patients with diabetes and answer their concerns regarding the new diabetes management technologies. Offering more telemedicine consultations has the potential to minimize life disruptions, increase engagement opportunities, and allow for the delivery of timely and personalized ongoing diabetes education and training [48].

We acknowledge that this study has some limitations, including the single-center setting and the small sample size, which may hinder the generalizability of our findings. In addition, the causality association between TM implementation and overall diabetes control cannot be confirmed here as the study was a single arm with no control group. The study also did not investigate other risk factors that can interact with the efficacy of TM, including educational level, socioeconomic status, and health literacy.

5. Conclusions

TM can serve as an effective tool to support improved glycemic and overall diabetes control in LTFU patients with poor glycemic status. Our single-center experience demonstrated that implementing the TM program, which involved home-based and center-based devices, led to significant improvements in overall diabetes measures, including glycemic control, body weight, and lipid profile. Thus, TM intervention represents an effective solution to engage a challenging population of patients with T2DM who had previously been lost to follow-up, resulting in improvements in metabolic parameters, such as HbA1c, FBG, DBP, weight, total cholesterol, and LDL-cholesterol. Future multicenter studies are required to assess the feasibility and barriers towards the application of a comprehensive TM program in the MENA region.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by LifeScan for Medical writing, statistical analysis, and editorial assistance. CHI provided the necessary technological support. The concept, study protocol, and the clinical conduct and data gathering of the study were independently done by the DDC team. Medical writing, statistical analysis, and editorial assistance were provided by Clinart MENA.

Abbreviations

- BG:

Blood glucose

- CI:

Confidence interval

- COVID-19:

Coronavirus disease 2019

- DDC:

Dubai Diabetes Center

- ECG:

Electrocardiography

- FBG:

Fasting blood glucose

- IRB:

Institutional Review Board

- LTFU:

Loss-to-follow-up

- MD:

Mean difference

- MENA:

Middle East and North Africa

- RBG:

Random blood glucose

- T2DM:

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- TC:

Teleconsultations

- TM:

Telemonitoring

- UAE:

United Arab Emirates.

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

Faisal Amir Nawaz is the CEO of Cognitive Healthcare International. Other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 1. Classes of Medications taken by each patient at the end of the study.

References

- 1.Duke L., Fereira de Moura A., Silvia Gorban de Lapertosa S., et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas 9th edition . 9th. Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al Awadi F., Hassanein M., Hussain H. Y., et al. Prevalence of diabetes and associated health risk factors among adults in Dubai, United Arab Emirates: results from Dubai household survey 2019. Dubai Diabetes and Endocrinology Journal . 2020;26(4):164–173. doi: 10.1159/000512428. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalan Farmanfarma K. H., Ansari-Moghaddam A., Zareban I., Adineh H. A. Prevalence of type 2 diabetes in Middle-East: systematic review & meta-analysis. Primary Care Diabetes . 2020;14(4):297–304. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2020.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deshpande A. D., Harris-Hayes M., Schootman M. Epidemiology of diabetes and diabetes-related complications. Physical Therapy . 2008;88(11):1254–1264. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20080020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trikkalinou A., Papazafiropoulou A. K., Melidonis A. Type 2 diabetes and quality of life. World Journal of Diabetes . 2017;8(4):120–129. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v8.i4.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chawla R., Chawla A., Jaggi S. Microvascular and macrovascular complications in diabetes mellitus: distinct or continuum? Indian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism . 2016;20(4):546–551. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.183480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chetoui A., Kaoutar K., Elmoussaoui S., et al. Prevalence and determinants of poor glycaemic control: a cross-sectional study among Moroccan type 2 diabetes patients. International Health . 2020;107 doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihz107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Rasheedi A. A. Glycemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in countries of Arabic gulf. International Journal of Health Sciences . 2015;9(3):339–344. doi: 10.12816/0024701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alawadi F., Abdelgadir E., Bashier A., et al. Glycemic control in patients with diabetes across primary and tertiary government health sectors in the emirate of Dubai, United Arab Emirates: a five-year pattern. Oman Medical Journal . 2019;34(1):20–25. doi: 10.5001/omj.2019.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oluma A., Abadiga M., Mosisa G., Etafa W. Magnitude and predictors of poor glycemic control among patients with diabetes attending public hospitals of Western Ethiopia. PLoS One . 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0247634.e0247634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Rasheedi A. A. S. The role of educational level in glycemic control among patients with type II diabetes mellitus. International Journal of Health Sciences . 2014;8(2):177–187. doi: 10.12816/0006084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malcolm J. C., Maranger J., Taljaard M., et al. Into the abyss: diabetes process of care indicators and outcomes of defaulters from a Canadian tertiary care multidisciplinary diabetes clinic. BMC Health Services Research . 2013;13(1):303–309. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chew B.-H., Lee P.-Y., Shariff-Ghazali S., Cheong A.-T., Ismail M., Taher S.-W. Predictive factors of follow-up non-attendance and mortality among adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus- an analysis of the Malaysian diabetes registry 2009. Current Diabetes Reviews . 2015;11(2):122–131. doi: 10.2174/1573399811666150115105206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abdelmotaal H., Ibrahim W., Sharaf M., Abdelazeem K. Causes and clinical impact of loss to follow-up in patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Journal of Ophthalmology . 2020;2020:8. doi: 10.1155/2020/7691724.7691724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saadi H., Al-Kaabi J., Benbarka M., et al. Prevalence of undiagnosed diabetes and quality of care in diabetic patients followed at primary and tertiary clinics in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. The Review of Diabetic Studies . 2010;7(4):293–302. doi: 10.1900/RDS.2010.7.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Groot J., Wu D., Flynn D., Robertson D., Grant G., Sun J. Efficacy of telemedicine on glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. World Journal of Diabetes . 2021;12(2):170–197. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v12.i2.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aberer F., Hochfellner D. A., Mader J. K. Application of telemedicine in diabetes care: the time is now. Diabetes Therapy . 2021;12(3):629–639. doi: 10.1007/s13300-020-00996-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dailey G. Assessing glycemic control with self-monitoring of blood glucose and hemoglobin A1c measurements. Mayo Clinic Proceedings . 2007;82(2):229–236. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(11)61003-3. quiz 236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abaza H., Marschollek M. mHealth application areas and technology combinations: a comparison of literature from high and low/middle income countries. Methods of Information in Medicine . 2017;56:e105–e122. doi: 10.3414/ME17-05-0003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doupis J., Avramidis K. Managing diabetes during the COVID-19 pandemic. European Journal of Endocrinology . 2020;16(2):85–87. doi: 10.17925/EE.2020.16.2.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang B. Expert consensus on telemedicine management of diabetes (2020 edition) International Journal of Endocrinology . 2021;2021:12. doi: 10.1155/2021/6643491.6643491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sayed S. COVID-19 and diabetes; possible role of polymorphism and rise of telemedicine. Primary Care Diabetes . 2021;15(1):4–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2020.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.JAVA. Declaration of Helsinki world medical association declaration of Helsinki. Bulletin of the World Health Organization . 2013;79(4):373–374. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu Y., Yan Q., Li H., et al. Effects of mobile phone application combined with or without self-monitoring of blood glucose on glycemic control in patients with diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Diabetes Investigation . 2019;10(5):1365–1371. doi: 10.1111/jdi.13031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.American Diabetes Association (ADA) 9. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment: standards of medical care in diabetes—2020. Diabetes Care . 2020;43(Supplement 1):S98–S110. doi: 10.2337/dc20-S009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hewitt H., Gafaranga J., McKinstry B. Comparison of face-to-face and telephone consultations in primary care: qualitative analysis. British Journal of General Practice . 2010;60(574):e201–e212. doi: 10.3399/bjgp10x501831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martín-Lesende I., Orruño E., Mateos M., et al. Telemonitoring in-home complex chronic patients from primary care in routine clinical practice: impact on healthcare resources use. The European Journal of General Practice . 2017;23(1):136–143. doi: 10.1080/13814788.2017.1306516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee S. W. H., Chan C. K. Y., Chua S. S., Chaiyakunapruk N. Comparative effectiveness of telemedicine strategies on type 2 diabetes management: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Scientific Reports . 2017;7(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-12987-z.12680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alboraie M., Allam M. A., Youssef N., et al. Knowledge, applicability, and barriers of telemedicine in Egypt: a national survey. International Journal of Telemedicine and Applications . 2021;2021:8. doi: 10.1155/2021/5565652.5565652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shan R., Sarkar S., Martin S. S. Digital health technology and mobile devices for the management of diabetes mellitus: state of the art. Diabetologia . 2019;62(6):877–887. doi: 10.1007/s00125-019-4864-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hanley J., Fairbrother P., McCloughan L., et al. Qualitative study of telemonitoring of blood glucose and blood pressure in type 2 diabetes. BMJ Open . 2015;5(12) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008896.e008896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee M.-K., Lee K.-H., Yoo S.-H., Park C.-Y. Impact of initial active engagement in self-monitoring with a telemonitoring device on glycemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes. Scientific Reports . 2017;7(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-03842-2.3866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim Y., Park J.-E., Lee B.-W., Jung C.-H., Park D.-A. Comparative effectiveness of telemonitoring versus usual care for type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare . 2019;25(10):587–601. doi: 10.1177/1357633x18782599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee J. Y., Wong C. P., Tan C. S. S., Nasir N. H., Lee S. W. H. Telemonitoring in fasting individuals with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus during Ramadan: a prospective, randomised controlled study. Scientific Reports . 2017;7(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10564-y.10119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jeong J. Y., Jeon J.-H., Bae K.-H., et al. Smart care based on telemonitoring and telemedicine for type 2 diabetes care: multi-center randomized controlled trial. Telemedicine and e-Health . 2018;24(8):604–613. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2017.0203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sherwani S. I., Khan H. A., Ekhzaimy A., Masood A., Sakharkar M. K. Significance of HbA1c test in diagnosis and prognosis of diabetic patients. Biomarker Insights . 2016;11:95–104. doi: 10.4137/BMI.S38440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bashshur R. L., Shannon G. W., Smith B. R., Woodward M. A. The empirical evidence for the telemedicine intervention in diabetes management. Telemedicine and e-Health . 2015;21(5):321–354. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2015.0029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huayanay-Espinoza I. E., Guerra-Castañon F., Lazo-Porras M., et al. Metabolic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in a public hospital in Peru: a cross-sectional study in a low-middle income country. PeerJ . 2016;4(10) doi: 10.7717/peerj.2577.e2577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chao E. C. A paradigm shift in diabetes therapy--dapagliflozin and other SGLT2 inhibitors. Discovery Medicine . 2011;11:255–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Colosia A., Khan S., Palencia R. Prevalence of hypertension and obesity in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in observational studies: a systematic literature review. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity: Targets and Therapy . 2013;6:327–328. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S51325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sleight P., Yusuf S., Pogue J., Tsuyuki R., Diaz R., Probstfield J. Blood-pressure reduction and cardiovascular risk in HOPE study. Lancet . 2001;358 doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)07186-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Polonsky W. H., Henry R. R. Poor medication adherence in type 2 diabetes: recognizing the scope of the problem and its key contributors. Patient Prefer Adherence . 2016;10:1299–1306. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S106821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bingham J. M., Black M., Anderson E. J., et al. Impact of telehealth interventions on medication adherence for patients with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and/or dyslipidemia: a systematic review. Annals of Pharmacotherapy . 2021;55:637–649. doi: 10.1177/1060028020950726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cassimatis M., Kavanagh D. J. Effects of type 2 diabetes behavioural telehealth interventions on glycaemic control and adherence: a systematic review. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare . 2012;18(8):447–450. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2012.gth105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weisser B., Predel H. G., Gillessen A., et al. Single pill regimen leads to better adherence and clinical outcome in daily practice in patients suffering from hypertension and/or dyslipidemia: results of a meta-analysis. High Blood Pressure & Cardiovascular Prevention . 2020;27(2):157–164. doi: 10.1007/s40292-020-00370-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Scott Kruse C., Karem P., Shifflett K., Vegi L., Ravi K., Brooks M. Evaluating barriers to adopting telemedicine worldwide: a systematic review. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare . 2018;24(1):4–12. doi: 10.1177/1357633x16674087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fuchs J., Hovorka R. COVID-19 and diabetes: could diabetes technology research help pave the way for remote healthcare? Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology . 2020;14(4):735–736. doi: 10.1177/1932296820929714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Prahalad P., Tanenbaum M., Hood K., Maahs D. M. Diabetes technology: improving care, improving patient-reported outcomes and preventing complications in young people with Type 1 diabetes. Diabetic Medicine . 2018;35(4):419–429. doi: 10.1111/dme.13588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 1. Classes of Medications taken by each patient at the end of the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.