Abstract

Lymphedema results from inadequate lymphatic function. Extreme obesity can cause lower extremity lymphedema, termed “obesity-induced lymphedema (OIL).” OIL is a form of secondary lymphedema that may occur once an individual's body mass index (BMI) exceeds 40. The risk of lymphatic dysfunction increases with elevated BMI and is almost universal once BMI exceeds 60. Obesity has a negative impact on lymphatic density in subcutaneous tissue, lymphatic endothelial cell proliferation, lymphatic leakiness, collecting-vessel pumping capacity, and clearance of macromolecules. Lymphatic fluid unable to be taken up by lymphatic vessels results in increased subcutaneous adipose deposition, fibrosis, and worsening obesity. Individuals with OIL are in an unfavorable cycle of weight gain and lymphatic injury. The fundamental treatment for OIL is weight loss.

Lymphedema results from inadequate lymphatic function, and is a chronic, progressive condition. Severe obesity can independently cause lymphedema (“obesity-induced lymphedema” [OIL]). OIL is a type of secondary lymphedema and can occur once an individual's body mass index (BMI) is greater than 40 (obesity is defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as a BMI ≥ 30). OIL is almost universal when BMI is greater than 60. The condition has been studied extensively in animal models and involves increased perilymphatic inflammation (Kataru et al. 2020). The resulting changes affect lymphatic endothelial cell (LEC) gene expression and impair lymphatic function. Furthermore, dysfunctional lymphatics alter lipid utilization and result in increased subcutaneous adipose deposition contributing to worsening obesity. Thus, lymphedema and obesity have a reciprocal relationship. This article will review the clinical features and pathophysiology of OIL.

LYMPHEDEMA AND OBESITY

The adverse effects of obesity on the lymphatic system were first recognized in patients who developed upper extremity lymphedema following breast cancer treatment (Helyer et al. 2010). BMI is the most important variable associated with lymphedema following axillary lymphadenectomy and radiation; as BMI increases, the risk of lymphedema also increases (Werner et al. 1991). Elevated BMI is associated with greater morbidity in patients diagnosed with lymphedema as well. Obese individuals with lymphedema are more likely to have infection, hospitalization, and moderate or severe extremity overgrowth compared to normal-weighted patients (Greene et al. 2020).

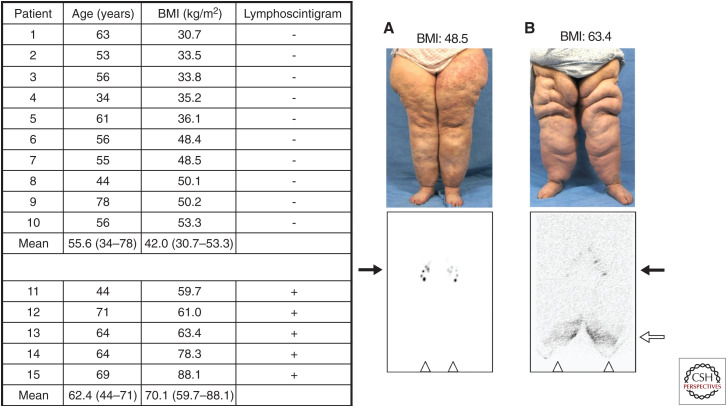

Our group demonstrated that extreme obesity can independently cause lymphedema in 2012 (Greene et al. 2012) and named the condition “obesity-induced lymphedema” (OIL) (Fig. 1; Greene and Maclellan 2013). As our volume of patients increased, we published follow-up studies in 2015 (Fig. 2; Greene et al. 2015b) and in 2020 (Greene and Sudduth 2020b), updating our experience with this disease. Lymphatic dysfunction starts to occur when BMI exceeds 40; the risk is 6% at a BMI < 50 and 90% when BMI is >60 (Greene and Sudduth 2020b). In non-ambulatory patients with neuromuscular disease, the BMI threshold to cause lymphedema is lower; these patients can develop OIL once their BMI exceeds 30 (Greene and Sudduth 2020a). We showed that patients with OIL are at risk for developing localized areas of overgrowth termed “massive localized lymphedema” (MLL) (Fig. 3; Maclellan et al. 2017).

Figure 1.

Original 2012 cohort of obese patients with bilateral lower extremity enlargement and a referral diagnosis of “lymphedema.” All patients with a body mass index (BMI) ≤ 53.3 had a negative lymphoscintigram, indicating normal lymphatic function of the lower limbs. Each patient with a BMI ≥ 59.7 had a positive study (i.e., delayed transport of radiolabeled tracer and/or dermal backflow), showing abnormal lymphatic drainage consistent with lymphedema. (A) 55-yr-old woman (patient #7) with normal transit of technetium-99m (Tc-99m) filtered sulfur colloid to the inguinal nodes 45 min following intradermal injection into the feet. (B) 64-yr-old woman (patient #13) with delayed tracer uptake into the inguinal nodes and dermal backflow 5 h after injection of the radiolabeled colloid. Inguinal nodes (black arrows); dermal backflow in distal lower extremities (white arrow); injection sites in feet (triangles). (Figure from Greene et al. 2012; reprinted, with permission, from the Massachusetts Medical Society © 2012.)

Figure 2.

Follow-up 2015 cohort of obese patients with or without lymphedema. Patients without a history of massive weight loss and a body mass index (BMI) <50 kg/m2 had normal lower extremity lymphatic function. Individuals with a BMI >60 kg/m2 had abnormal findings on lymphoscintigraphy consistent with lymphedema. A BMI threshold between 50 kg/m2 and 60 kg/m2 appeared to exist, at which point lymphatic dysfunction occurs. Patients on the left with a normal lymphoscintigram result exhibited inguinal lymph node uptake of technetium Tc-99m sulfur colloid 45 min after injection into the feet. Subjects on the right with an abnormal lymphoscintigram result showed delayed transport of tracer and/or dermal backflow on 3-h images. Black arrows identify inguinal lymph nodes, and the white arrow marks dermal backflow. (Figure from Greene et al. 2015; reprinted, with permission, from Wolters Kluwer Health © 2015.)

Figure 3.

Patients with obesity-induced lymphedema (OIL) are at risk for developing areas of massive localized lymphedema (MLL). (A) Patient with a body mass index (BMI) of 70 has OIL and MLL of the left thigh. (B) The abnormal lymphoscintigram exhibits reduced inguinal lymph node uptake of technetium-99m sulfur colloid and dermal backflow in the left leg. (C) The area of MLL is significantly improved after the BMI was lowered to 30 following a surgical-weight loss procedure. (Figure from Maclellan et al. 2017; reprinted, with permission, from Elsevier © 2017.)

Obesity and lymphedema have a reciprocal relationship. Obesity increases the risk and morbidity of lymphedema and can cause the disease. Lymphedema, in turn, results in subcutaneous adipose deposition that contributes to obesity (Brorson et al. 2006). The association between the two diseases has important consequences for public health. Obesity affects one-third of the U.S. population (6% have a BMI > 40) (Hales et al. 2018), while 1/1000 Americans have lymphedema (Rockson and Rivera 2008).

CLINICAL FEATURES OF OBESITY-INDUCED LYMPHEDEMA

Most patients with OIL were previously healthy and had either a normal (<25) or overweight (25–30) BMI as a teenager and young adult. As the individual gained weight they noted swelling of their extremities, followed by a worsening cycle of weight gain and lower extremity enlargement. The most important risk factor for OIL is the patient's maximum BMI history. Individuals who currently or previously had a BMI > 40 can develop the disease; the likelihood is much higher if a patient has had a BMI > 60 (Greene et al. 2015b; Greene and Sudduth 2020b). At a BMI > 60, 90% of patients will have lymphatic dysfunction (Greene and Sudduth 2020b). Patients with OIL have a higher risk of infection (58%) compared to patients with other causes of lymphedema (24%) (Sudduth et al. 2020).

Physical examination is inadequate to diagnose OIL because an obese leg with or without lymphedema appears the same. Although the likelihood of OIL is predicted by BMI, definitive diagnosis requires lymphoscintigraphy (Greene et al. 2012, 2015b; Greene and Sudduth 2020b). This test is 96% sensitive and 100% specific for lymphedema (Hassanein et al. 2017) and all patients being evaluated for OIL undergo this test. Delayed transit of radiolabeled colloid to regional lymph nodes, dermal backflow, presence of abnormal nodes, and/or tortuous collateral lymphatic channels indicate the presence of lymphatic dysfunction (Gloviczki et al. 1989; Szuba et al. 2003; Scarsbrook et al. 2007; Hassanein et al. 2017).

The risk of OIL increases with elevated BMI: BMI < 40 (0%), 40–49 (17%), 50–59 (63%), 60–69 (86%), 70–79 (91%), and >80 (100%) (Table 1; Greene and Sudduth 2020b). Lymphoscintigraphy shows abnormalities bilaterally (75%) or unilaterally (25%) (Greene et al. 2015b). OIL also can affect the upper extremities (Greene and Maclellan 2013). MLL of the lower extremities is present in 60% of patients with OIL and involves the thigh (94%; 2/3 bilateral, 1/3 unilateral), genitalia (18%), and suprapubic area (12%) (Maclellan et al. 2017). The probability of patients with OIL developing MLL is directly related to their BMI: BMI = 40 (4%), BMI = 50 (15%), BMI = 60 (40%), BMI = 70 (75%), BMI = 80 (92%) (Table 1; Fig. 3). Patients with OIL and a BMI > 56 have 213 times greater odds of developing MLL versus a BMI < 56 (Maclellan et al. 2017).

Table 1.

Increasing body mass index predicts the risk of lymphedema and correlates with the development of massive localized lymphedema

| Body mass index (BMI) | Obesity-induced lymphedema (OIL) | Massive localized lymphedema (MLL) |

|---|---|---|

| <40 | 0% | 0% |

| 40–49 | 17% | 4% |

| 50–59 | 63% | 15% |

| 60–69 | 86% | 40% |

| 70–79 | 91% | 75% |

| >80 | 100% | 92% |

Table based on data from Greene and Sudduth (2020b) and Maclellan et al. (2017).

Definitive management of OIL requires treating the underlying cause of the disease, which is the patient's elevated BMI. While a minority of individuals are able to lose significant weight by diet and exercise, most benefit from a surgical weight-loss procedure. Reducing the patient's BMI is the only way to stop the vicious cycle of inflammation, adipose deposition, further lymphatic damage, enlarging extremity size, and the development of MLL. We also recommend obese patients with a BMI > 40 who do not yet have OIL by lymphoscintigraphy to lose weight before they develop the potentially incurable condition. Unlike other comorbidities that are reversible with weight loss (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia), lymphatic dysfunction may not be improved.

Operations to reduce leg volume or remove areas of MLL are performed only after patients have achieved their lowest possible BMI and their BMI is <40. Following weight loss, most patients will have a satisfactory reduction in the size of their legs and areas of MLL (Greene et al. 2015a; Maclellan et al. 2017). If an excisional procedure is still indicated, the reduced BMI significantly facilitates the intervention and reduces the risk of recurrence.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF OBESITY-INDUCED LYMPHATIC DYSFUNCTION

The relationship between obesity and lymphedema has been an important focus of recent basic science research in the field (Kataru et al. 2020). Animal models have recapitulated the negative effects of obesity on lymph flow and uncovered mechanisms by which obesity results in impaired lymphatic function. Murine data shows that exercise, weight reduction, and pharmacotherapy can improve lymphatic dysfunction associated with obesity (Kataru et al. 2020).

The lymphatic system consists of capillary lymphatic vessels and collecting lymphatic vessels that transport interstitial fluid into lymph nodes and return the fluid to blood circulation. This system functions in fluid homeostasis, immune response, macromolecule transport, and dietary fat and cholesterol absorption. Lymph transport depends on the function of the lymphatic vasculature (clearance) and the volume of lymph produced by the tissues (load). Obesity results in pathologic inflammatory changes that adversely affect lymphatic structure and function (Kataru et al. 2020).

Several mechanisms may explain the pathophysiology of OIL. One hypothesis is that the lymphatics in the extremity are normal but are unable to transport the increased volume of lymph. As the patient's BMI rises, the amount of lymph produced by the leg increases, while ambulation/muscle contraction to transport the fluid decreases. Clinical evidence supporting this theory is that nonambulatory individuals develop OIL at a lower BMI than ambulatory patients (Greene and Sudduth 2020a). Because this patient population is unable to walk and has nonfunctional lower extremity muscles, a lower BMI “second hit” may be necessary to overwhelm lymph transport. Excessive pressure from the weight of the tissue and/or progressive skin folds might also reduce lymphatic flow by collapsing lymph vessels.

Much of our knowledge about the etiopathogenesis of OIL is derived from animal studies using obese mice fed a high-fat diet (Kataru et al. 2020). These mice have increased inflammation, decreased lymphatic density in subcutaneous tissues, reduced LEC proliferation, increased lymphatic leakiness, decreased collecting-vessel pumping capacity, and impaired clearance of macromolecules (Hwee et al. 2009; Savetsky et al. 2014; Kataru et al. 2020). Lymphatic fluid transport is significantly impaired, lymph node uptake is reduced, and inguinal lymph nodes are threefold smaller with less lymphatics (Weitman et al. 2013). Obese mice have reduced frequency of lymphatic vessel contractions and a diminished response to mechanostimulation (Blum et al. 2014).

Pathologic changes in lymphatic structure and function are related to alterations in lymphatic-specific gene expression. Lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronan receptor 1 (LYVE-1), prospero-related homeobox 1 (PROX-1), podoplanin, and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 (VEGFR3) expression is decreased in obese mice (García Nores et al. 2016; Kataru et al. 2020). PROX-1 is the master regular of LEC differentiation and VEGFR3 is the main receptor for lymphangiogenic growth factors. These changes in gene expression have downstream effects on LEC proliferation and differentiation in obese mice likely contributing to impairment of lymphatic function.

On a cellular level, a chronic inflammatory response appears to mediate the damage to lymphatics associated with obesity. Obesity in humans impairs lymphatic drainage of macromolecules, which promotes inflammation (Arngrim et al. 2013). Obese mice have chronic inflammation in subcutaneous fat, and inflammatory cells accumulate around lymphatic vessels (García Nores et al. 2016; Torrisi et al. 2016). The mechanism likely is related to increased leakiness of collecting lymphatic vessels and resultant trapping of inflammatory cells in tissues (Kataru et al. 2020). Furthermore, growth factors that are highly chemotactic for inflammatory cells are up-regulated in the perilymphatic tissues (Weitman et al. 2013; Kataru et al. 2020). Increased free fatty acids associated with obesity damage LECs. In vitro, free fatty acids result in increased apoptosis, decreased proliferation, and down-regulation of PROX-1 and VEGFR3 in LECs (García Nores et al. 2016; Kataru et al. 2020).

The lymphatic dysfunction caused by obesity creates an unfavorable cycle because decreased lymphatic function subsequently worsens obesity by increasing subcutaneous adipose deposition (Brorson et al. 2006). Histologically, lymphedema results in progressive hypertrophic adipocytes with increased collagen deposits, impaired regenerative capacity, and reduced immunological function (Tashiro et al. 2017). In mice, lymphatic injury is associated with remodeling of adipose tissues and up-regulation of genes involved in adipocyte differentiation (CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein-α [CEBP-α], adiponectin, and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ [PPAR-γ]) (Zampell et al. 2012; Kataru et al. 2020). The downstream result is activation of adipocytes and subsequent deposition of adipose tissue.

The pathophysiology of MLL is unclear. As BMI continues to rise, skin folds might obstruct lymphatics resulting in localized overgrowth. The thighs might be preferentially affected because there is more skin laxity compared to the distal extremity. Histologically, MLL is different than typical lymphedema, which exhibits subcutaneous fibroadipose tissue with inflammation (Li et al. 2020). MLL histologically appears similar to well-differentiated liposarcoma (WDL) because widened septa resemble the fibrous bands of WDL (Farshid and Weiss 1998). MLL, however, does not exhibit significant nuclear atypia present in WDL (Farshid and Weiss 1998).

Behavioral modifications have demonstrated improved lymphatic function in animal models of OIL. Aerobic exercise decreases perilymphatic inflammatory cell accumulation, improves lymphatic function, and reverses pathologic LEC gene expression of VEGFR3 and PROX-1 in obese mice (Hespe et al. 2016). Decreased caloric intake also lowers adipose inflammation and normalizes lymphatic function (Nitti et al. 2016). Targeted pharmacotherapy may play a future role in the management of OIL. Inhibition of T-cell response with an IL-2 inhibitor in obese mice decreases lymphatic leakiness and improves lymphatic pumping capacity (Torrisi et al. 2016; Kataru et al. 2020). Additionally, small molecule inhibition of iNOS expressed by perilymphatic macrophages enhances lymphatic pumping and function (Torrisi et al. 2016).

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Lymphedema and obesity are reciprocal conditions that negatively affect each other. OIL is a type of secondary lymphedema that results from elevated BMI. A BMI threshold of 40 exists at which point lower extremity lymphatic dysfunction can occur. The risk of OIL increases with elevated BMI; 90% of individuals with a BMI > 60 will have the disease. OIL is caused by a chronic perilymphatic inflammatory response that decreases lymphatic density in subcutaneous tissues, reduces LEC proliferation, increases lymphatic leakiness, decreases collecting vessel pumping capacity, and impairs clearance of macromolecules. The treatment for OIL is weight loss to break the cycle of worsening lymphedema and weight gain.

Footnotes

Editors: Diane R. Bielenberg and Patricia A. D'Amore

Additional Perspectives on Angiogenesis: Biology and Pathology available at www.perspectivesinmedicine.org

REFERENCES

- Arngrim N, Simonsen L, Holst JJ, Bülow J. 2013. Reduced adipose tissue lymphatic drainage of macromolecules in obese subjects: a possible link between obesity and local tissue inflammation. Int J Obes 37: 748–750. 10.1038/ijo.2012.98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum KS, Karaman S, Proulx ST, Ochsenbein AM, Luciani P, Leroux JC, Wolfrum C, Detmar M. 2014. Chronic high-fat diet impairs collecting lymphatic vessel function in mice. PLoS ONE 9: e94713. 10.1371/journal.pone.0094713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brorson H, Ohlin K, Olsson G, Nilsson M. 2006. Adipose tissue dominates chronic arm lymphedema following breast cancer: an analysis using volume rendered CT images. Lymphat Res Biol 4: 199–210. 10.1089/lrb.2006.4404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farshid G, Weiss SW. 1998. Massive localized lymphedema in the morbidly obese: a histologically distinct reactive lesion simulating liposarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol 22: 1277–1283. 10.1097/00000478-199810000-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García Nores GD, Cuzzone DA, Albano NJ, Hespe GE, Kataru RP, Torrisi JS, Gardenier JC, Savetsky IL, Aschen SZ, Nitti MD, et al. 2016. Obesity but not high-fat diet impairs lymphatic function. Int J Obes (Lond) 40: 1582–1590. 10.1038/ijo.2016.96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloviczki P, Calcagno D, Schirger A, Pairolero PC, Cherry KJ, Hallett JW, Wahner HW. 1989. Noninvasive evaluation of the swollen extremity: experiences with 190 lymphoscintigraphic examinations. J Vasc Surg 9: 683–690. 10.1016/S0741-5214(89)70040-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene AK, Maclellan RA. 2013. Obesity-induced upper extremity lymphedema. Plast Reconstr Surg 1: 59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene AK, Sudduth CL. 2020a. Lower extremity lymphatic function in nonambulatory patients with neuromuscular disease. Lymphat Res Biol 19: 126–128. 10.1089/lrb.2020.0008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene AK, Sudduth CL. 2020b. Lower extremity lymphatic function predicted by body mass index: a lymphoscintigraphic study of obesity and lipedema. Int J Obes (Lond) 45: 369–373. 10.1038/s41366-020-00681-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene AK, Grant FD, Slavin SA. 2012. Lower-extremity lymphedema and elevated body-mass index. N Engl J Med 366: 2136–2137. 10.1056/NEJMc1201684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene AK, Grant FD, Maclellan RA. 2015a. Obesity-induced lymphedema nonreversible following massive weight loss. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 3: e426. 10.1097/GOX.0000000000000398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene AK, Grant FD, Slavin SA, Maclellan RA. 2015b. Obesity-induced lymphedema: clinical and lymphoscintigraphic features. Plast Reconstr Surg 135: 1715–1719. 10.1097/PRS.0000000000001271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene AK, Zurakowski D, Goss JA. 2020. Body mass index and lymphedema morbidity: comparison of obese versus normal-weight patients. Plast Reconstr Surg 146: 402–407. 10.1097/PRS.0000000000007021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hales CM, Fryar CD, Carroll MD, Freedman DS, Ogden CL. 2018. Trends in obesity and severe obesity prevalence in US youth and adults by sex and age, 2007–2008 to 2015–2016. JAMA 319: 1723–1725. 10.1001/jama.2018.3060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassanein AH, MacLellan RA, Grant FD, Greene AK. 2017. Diagnostic accuracy of lymphoscintigraphy for lymphedema and analysis of false-negative tests. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 5: e1396. 10.1097/GOX.0000000000001396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helyer LK, Varnic M, Le LW, Leong W, McCready D. 2010. Obesity is a risk factor for developing postoperative lymphedema in breast cancer patients. Breast J 16: 48–54. 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2009.00855.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hespe GE, Kataru RP, Savetsky IL, García Nores GD, Torrisi JS, Nitti MD, Gardenier JC, Shou J, Yu JZ, Jones LW, et al. 2016. Exercise training improves obesity-related lymphatic dysfunction. J Physiol 594: 4267–4282. 10.1113/JP271757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwee YL, Rutkowski JM, Helft J, Reddy ST, Swartz MA, Randolph GJ, Angeli V. 2009. Hypercholesterolemic mice exhibit lymphatic vessel dysfunction and degeneration. Am J Pathol 175: 1328–1337. 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataru RP, Park HJ, Baik JE, Li C, Shin J, Mehrara BJ. 2020. Regulation of lymphatic function in obesity. Front Physiol 11. 10.3389/fphys.2020.00459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CY, Kataru RP, Mehrara BJ. 2020. Histopathologic features of lymphedema: a molecular review. Int J Mol Sci 21: 2546. 10.3390/ijms21072546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maclellan RA, Zurakowski D, Grant FD, Greene AK. 2017. Massive localized lymphedema: a case-control study. J Am Coll Surg 224: 212–216. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2016.10.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitti MD, Hespe GE, Kataru RP, García Nores GD, Savetsky IL, Torrisi JS, Gardenier JC, Dannenberg AJ, Mehrara BJ. 2016. Obesity-induced lymphatic dysfunction is reversible with weight loss. J Physiol 594: 7073–7087. 10.1113/JP273061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockson SG, Rivera KK. 2008. Estimating the population burden of lymphedema. Ann NY Acad Sci 1131: 147–154. 10.1196/annals.1413.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savetsky IL, Torrisi JS, Cuzzone DA, Ghanta S, Albano NJ, Gardenier JC, Joseph WJ, Mehrara BJ. 2014. Obesity increases inflammation and impairs lymphatic function in a mouse model of lymphedema. Am J Physiol Circ Physiol 307: H165–H172. 10.1152/ajpheart.00244.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarsbrook AF, Ganeshan A, Bradley KM. 2007. Pearls and pitfalls of radionuclide imaging of the lymphatic system. Part 2: Evaluation of extremity lymphoedema. Br J Radiol 80: 219–226. 10.1259/bjr/68256780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudduth CL, Maclellan RA, Greene AK. 2020. Study of 700 referrals to a lymphedema program. Lymphat Res Biol 18: 534–538. 10.1089/lrb.2019.0086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szuba A, Shin WS, Strauss HW, Rockson S. 2003. The third circulation: radionuclide lymphoscintigraphy in the evaluation of lymphedema. J Nucl Med 44: 43–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashiro K, Feng J, Wu SH, Mashiko T, Kanayama K, Narushima M, Uda H, Miyamoto S, Koshima I, Yoshimura K. 2017. Pathological changes of adipose tissue in secondary lymphoedema. Br J Dermatol 177: 158–167. 10.1111/bjd.15238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrisi JS, Hespe GE, Cuzzone DA, Savetsky IL, Nitti MD, Gardenier JC, García Nores GD, Jowhar D, Kataru RP, Mehrara BJ. 2016. Inhibition of inflammation and iNOS improves lymphatic function in obesity. Sci Rep 6: 1–12. 10.1038/srep19817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitman ES, Aschen SZ, Farias-Eisner G, Albano N, Cuzzone DA, Ghanta S, Zampell JC, Thorek D, Mehrara BJ. 2013. Obesity impairs lymphatic fluid transport and dendritic cell migration to lymph nodes. PLoS ONE 8: e70703. 10.1371/journal.pone.0070703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner RS, McCormick B, Petrek J, Cox L, Cirrincione C, Gray JR, Yahalom J. 1991. Arm edema in conservatively managed breast cancer: obesity is a major predictive factor. Radiology 180: 177–184. 10.1148/radiology.180.1.2052688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zampell JC, Aschen S, Weitman ES, Yan A, Elhadad S, De Brot Andrade M, Mehrara BJ. 2012. Regulation of adipogenesis by lymphatic fluid stasis. Part I: Adipogenesis, fibrosis, and inflammation. Plast Reconstr Surg 129: 825–834. 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182450b2d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]