Abstract

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic brought social, economic, and health impacts, requiring fast adaptation of health systems. Although information and communication technologies were essential for achieving this objective, the extent to which health systems incorporated this technology is unknown.

Objective

The aim of this study was to map the use of digital health strategies in primary health care worldwide and their impact on quality of care during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

We performed a scoping review based on the Joanna Briggs Institute manual and guided by the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses) Extension for Scoping Reviews. A systematic and comprehensive three-step search was performed in June and July 2021 in multidisciplinary health science databases and the gray literature. Data extraction and eligibility were performed by two authors independently and interpreted using thematic analysis.

Results

A total of 44 studies were included and six thematic groups were identified: characterization and geographic distribution of studies; nomenclatures of digital strategies adopted; types of information and communication technologies; characteristics of digital strategies in primary health care; impacts on quality of care; and benefits, limitations, and challenges of digital strategies in primary health care. The impacts on organization of quality of care were investigated by the majority of studies, demonstrating the strengthening of (1) continuity of care; (2) economic, social, geographical, time, and cultural accessibility; (3) coordination of care; (4) access; (5) integrality of care; (6) optimization of appointment time; (7) and efficiency. Negative impacts were also observed in the same dimensions, such as reduced access to services and increased inequity and unequal use of services offered, digital exclusion of part of the population, lack of planning for defining the role of professionals, disarticulation of actions with real needs of the population, fragile articulation between remote and face-to-face modalities, and unpreparedness of professionals to meet demands using digital technologies.

Conclusions

The results showed the positive and negative impacts of remote strategies on quality of care in primary care and the inability to take advantage of the potential of technologies. This may demonstrate differences in the organization of fast and urgent implementation of digital strategies in primary health care worldwide. Primary health care must strengthen its response capacity, expand the use of information and communication technologies, and manage challenges using scientific evidence since digital health is important and must be integrated into public service.

Keywords: digital health, telehealth, telemedicine, primary health care, quality of care, COVID-19, pandemic, science database, gray literature

Introduction

Quality in health care is a multidimensional concept related to how offered services increase the probability of desired health outcomes. Health care quality also permeates correct care at the right time and in a coordinated manner, responding to the needs and preferences of service users, and reducing damage and wasted resources through a continuous and dynamic process [1]. Quality of care approximates health services to the population and has three dimensions: technical (accuracy of actions and the way they are performed), interpersonal (social and psychological relationships between care providers and users), and organizational (conditions in which services are offered, including globalization and continuity of care, coverage, coordination of actions, access, and accessibility to services) [2-4].

The COVID-19 pandemic led to immediate and profound social, economic, and health impacts, and required fast adaptation of health systems focusing on quality. Health systems, particularly primary health care (PHC), were pushed to maintain care routines, which required changes to maintain access and continuous management of health problems. This was possible owing to the creativity and innovation of professionals and managers, who introduced or expanded the use of information and communication technology (ICT) in the critical initial phase of the pandemic, where lack of coordination has negatively influenced access to health care [5].

ICT use has digital health as a great exponent in remote care strategies. This term is historically addressed as telemedicine or telehealth, which refers to communication and interaction tools between health care professionals and patients that provide remote health services and care as alternative to face-to-face appointments [6-8].

The use of telephones to answer doubts of patients, videos or text messages through mobile apps, and social media are helpful strategies for expanding the scope of health care by enabling population access. ICT also reduces the distance between patients and health professionals (eg, rural areas lacking health professionals), and facilitates appointment scheduling and renewal of prescriptions, thereby changing the professional-patient relationship and expanding personal health management [6,7,9-11].

The COVID-19 pandemic became a catalyst for expanding ICT worldwide [12]. Although digital health was recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) [13-15] to reduce geographic barriers, its use increased only during the pandemic to maintain or increase access to health care, fight the pandemic, minimize economic impacts, and enable continuity of remote care [16,17].

Technological evolution may accelerate health care and improve access in the context of public health preparedness and response to outbreaks and emergencies. Despite these advances, the pandemic was challenging for health systems, mainly due to the lack of integration of technologies [17,18]. Considering the relevance of the topic for health and the wide use of ICT in PHC during the pandemic, we sought to gather knowledge about the quality of PHC using digital technologies. Therefore, the aim of this study was to map the use of digital health strategies in PHC worldwide and their impact on quality of care in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Design

This scoping review was performed based on the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) manual [19] and guided by PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews) guidelines [20]. We also followed the steps proposed by Arksey and O’Malley [21] and Levac et al [22]: formulation of research questions, identification of relevant studies, study selection, data extraction and coding, analysis and interpretation of results, and consultation with stakeholders.

Ethics Approval

The study was approved by the research ethics committee of the Faculty of Health Sciences of Trairí, Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (CAAE: 47473121.3.0000.5568), and direct participation of participants involved in the study occurred only during consultation with stakeholders. The methodology used was previously reported in a protocol [23]. The term “telemedicine” used in the protocol [23] was replaced by “digital health” in this scoping review since it was considered to be more appropriate to reflect the broad scope of the study.

Formulation of Research Questions

Study questions were defined by consensus among the authors and were formulated using the PCC (Population, Concept, and Context) mnemonic and the respective results of interest [19]: (1) Which countries used digital health in PHC in response to the COVID-19 pandemic? (2) What options of ICT were used in PHC in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic? (3) What is the impact of digital health on quality of health care delivery in PHC in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic?

Identification of Relevant Studies

The following multidisciplinary health science databases were searched for relevant articles: MEDLINE/PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, CINAHL, Embase, and LILACS. For gray literature, we consulted Google Scholar, WHO Global Research on Coronavirus Disease, PAHO Technical Documents and Research Evidence on COVID-19, Cochrane Library, medRxiv, SciELO Preprints, preprints.org, Open Grey, and Grey Literature Report.

The following types of studies and documents that addressed the research questions, focused on the use of remote strategies in PHC during the COVID-19 pandemic, and were available in full text were included: primary studies with quantitative, qualitative, or a mixed approach; experience reports; case reports; intervention studies; preprints; guidelines; manuals; reports; and government documents. No date or language filters were applied. Duplicate studies, protocols, literature reviews, opinion letters, and editorials were excluded.

Study Selection

The search was performed between June 14 and July 14, 2021, using a three-step search strategy [24]: (1) exploratory search in two databases to identify descriptors and keywords, followed by construction of the search strategy, which was improved by a librarian using the Extraction, Conversion, Combination, Construction, and Use model [25]; (2) definition and search in all databases; and (3) manual search for additional sources in references of selected studies. The detailed search strategies are presented in Multimedia Appendix 1.

Study selection followed the PRISMA steps [26]: identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion. A pilot study was independently conducted by two authors (CRDVS and RHL) using Rayyan software [27] to verify blinding, exclusion of duplicates, and selection of studies by titles and abstracts. Subsequently, full texts and reference lists of included studies were analyzed. For studies that did not meet inclusion criteria, a third author (SACU) was consulted.

Data Extraction and Coding

Data extraction and coding ensured the consistency and reliability of results. Two authors (CRDVS and RHL) independently extracted all relevant data using an extraction form based on the JBI template [24], which was adapted by the authors, containing the following information: characterization of studies (first author, year, journal, country, type of study, participants); names of digital strategies adopted; types of ICT; characteristics of digital strategies in PHC; impacts on quality of care; and benefits, limitations, and challenges of digital strategies in PHC.

The database was organized in a Microsoft Excel 2016 spreadsheet and is provided for consultation in Multimedia Appendix 2.

Analysis and Interpretation of Results

Data were analyzed qualitatively (narrative analysis) and quantitatively (absolute and relative frequencies). Thematic analysis [28] was structured based on familiarization with data, generation of initial codes, search for topics, review of topics, definition and naming of topics, and implications of studies. Results and narrative analyses are reported in tables and figures.

Consultation With Stakeholders

Results of this review were presented to five stakeholders (ie, researchers with experience in digital health, ICT in health, and PHC) to fulfill the following objectives recommended by Levac et al [22]: preliminary sharing of study findings, considered a mechanism for transferring and exchanging knowledge, and development of effective dissemination strategies and ideas for future studies. The form questions are provided in Multimedia Appendix 3.

Results

Included Studies

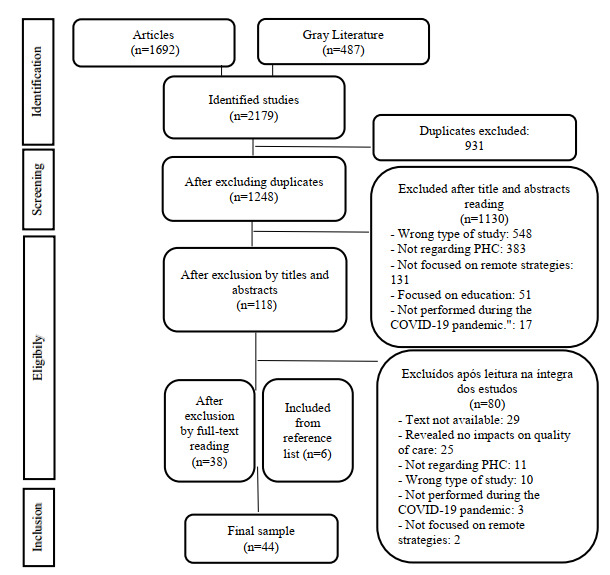

A total of 2179 publications were identified (1692 peer-reviewed articles and 487 gray literature documents). After excluding duplicates, analysis of titles and abstracts, and full-text reading, 38 studies were included. The manual search of reference lists added 6 studies, resulting in a total of 44 publications for analysis (Figure 1). All included studies demonstrated the impacts of remote strategies on quality of care in PHC in the context of COVID-19.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study selection for scoping review adapted from the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA).

Characterization and Geographic Distribution of Studies

The studies included were mostly published during 2021 (28/44, 64%). Among the 44 articles, 27 (61%) used a cross-sectional design, 6 (14%) used qualitative investigation, 6 (14%) used mixed methods, 2 (5%) were cohort studies, 1 (2%) was an experience report, 1 (2%) was a case report, and 1 (2%) was an intervention study. The sample consisted mainly of patients (n=19, 43%), health professionals (n=13, 30%), medical or consultation records (n=9, 21%), and documented interviews with patients or health professionals (n=3, 7%).

The studies covered 18 countries that used digital strategies in PHC; 18 studies were performed in North America (United States [29-43] and Canada [44-46]), 4 studies were performed in South America (Brazil [47-50]), 14 studies were performed in Europe (England [51-53], United Kingdom [54,55], Spain [56,57], Belgium [58,59], Norway [60], Portugal [61], Romania [62], Germany [63], and Poland [64]), four studies were performed in Asia (Israel [65], Oman [66], Saudi Arabia [67], and Iran [68]), and four studies were performed in Oceania (Australia [69-71] and New Zealand [72]). The characteristics of studies and distribution of countries that used digital strategies in PHC are described in Table 1 and Figure 2, respectively.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies.

| Reference | Source | Country | Study design | Participants/sample |

| Alexander et al [29] | JAMA Network Open | United States | Cross-sectional | National audit of consultations (n=117.9 million) |

| Schweiberger et al [30] | Journal of Medical Internet Research | United States | Cross-sectional | Electronic medical records (n=45) and physicians (n=121) |

| Olayiwola et al [31] | JMIR Public Health Surveillance | United States | Cross-sectional | Consultation records (n=3617) |

| Atherly et al [32] | JMIR Public Health Surveillance | United States | Cross-sectional | Patients (n=1694) |

| Judson et al [33] | Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association | United States | Cross-sectional | Consultation records (n=1129) |

| Mills et al [34] | Journal of the American Health Association | United States | Cross-sectional | Patients (n=587) |

| Tarn et al [35] | Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine | United States | Cross-sectional | Medical records (n=202) |

| Adepoju et al [36] | Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved | United States | Cross-sectional | Health workers (n=1344) |

| Ritchie et al [37] | Journal of the American Medical Directors Association | United States | Mixed methods | Health workers (n=79) |

| Drerup et al [38] | Telemedicine Journal and e-Health | United States | Cross-sectional | Patients (n=65) |

| Kalicki et al [39] | Journal of the American Geriatrics Society | United States | Cross-sectional | Medical records (n=873) |

| Chang et al [40] | Milbank Quarterly | United States | Cross-sectional | Health workers (n=918) |

| Thies et al [41] | Journal of Primary Care & Community Health | United States | Cross-sectional | Health workers (n=655) |

| Godfrey et al [42] | Contraception | United States | Cross-sectional | Medical records (n=534) |

| Juarez-Reyes et al [43] | Therapeutic Advances in Chronic Disease | United States | Qualitative investigation | Patients (n=6) |

| Bui et al [44] | Hamilton Family Health Team | Canada | Cross-sectional | Clinicians (n=126) and nurses (n=6) |

| Mohammed et al [45] | PLoS One | Canada | Cross-sectional | Clinicians (n=163) and nurses (n=37) |

| Donnelly et al [46] | BMC Family Practice | Canada | Mixed methods | Health workers (n=473) |

| Castro et al [47] | Revista Brasileira de Medicina da Família e da Comunidade | Brazil | Cross-sectional | Consultation records (n=329) |

| Dimer et al [48] | CoDAS | Brazil | Experience report | Consultation records (n=17) |

| Queiroz et al [49] | Acta Diabetologica | Brazil | Cohort | Patients (n=627) |

| Silva et al [50] | Ciência e Saúde Coletiva | Brazil | Cross-sectional | Clinicians and nurses (n=7054) |

| Sahni et al [51] | Cureus | England | Cross-sectional | Clinicians (n=312) |

| Leung et al [52] | BMJ Open Quality | England | Intervention study | Patients (n=12) |

| Tuijt et al [53] | British Journal of General Practice | England | Qualitative investigation | Patients (n=30) and caregivers (n=31) |

| Salisbury et al [54] | Journal of Medical Internet Research | United Kingdom | Mixed methods | Patients (n=1452) and health workers (n=12) |

| Murphy et al [55] | British Journal of General Practice | United Kingdom | Mixed methods | Medical records (n=350,966) and health workers (n=87) |

| Llamosas et al [56] | Physiotherapy | Spain | Case report | Patient (n=1) |

| Coronado-Vázquez et al [57] | Journal of Personalized Medicine | Spain | Cohort | Patients (n=166) |

| Morreel et al [58] | PLoS One | Belgium | Cross-sectional | Home visit records (n=15,655) |

| Verhoeven et al [59] | BMJ Open | Belgium | Qualitative investigation | Patients (n=132) |

| Johnsen et al [60] | Journal of Medical Internet Research | Norway | Cross-sectional | Clinicians (n=1237) |

| Lapão et al [61] | Journal of Medical Internet Research | Portugal | Mixed methods | Patients (n=35) |

| Florea et al [62] | International Journal of General Medicine | Romania | Cross-sectional | Clinicians (n=108) |

| Mueller et al [63] | JMIR Medical Informatics | Germany | Qualitative investigation | Patients (n=20) |

| Kludacz-Alessandri et al [64] | PLoS One | Poland | Cross-sectional | Patients (n=100) |

| Zeltzer et al [65] | National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER)/NBER Working Paper Series | Israel | Cross-sectional | Records from clinicians (n=4293) and patients (n=3.7 million) |

| Hasani et al [66] | Journal of Primary Care & Community Health | Oman | Qualitative investigation | Clinicians (n=22) |

| Alharbi et al [67] | Journal of Family and Community Medicine | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional | Patients (n=439) |

| Jannati et al [68] | International Journal of Medical Informatics | Iran | Cross-sectional | Patients (n=400) |

| Isautier et al [69] | Journal of Medical Internet Research | Australia | Cross-sectional | Patients (n=596) |

| Javanparast et al [70] | BMC Family Practice | Australia | Qualitative investigation | Patients (n=30) |

| Ervin et al [71] | Australian Journal of Primary Health | Australia | Cross-sectional | Clinicians (n=24) |

| Imlach et al [72] | BMC Family Practice | New Zealand | Mixed methods | Patients (n=1010) |

Figure 2.

Distribution of countries that used digital strategies in primary health care. Numbers represent the number of studies performed in each country.

Nomenclatures of Adopted Digital Strategies

Nomenclatures regarding remote care strategies varied considerably among studies, with the terms “telehealth” [30,33,36,44,45,47,54,55,60,63,64,67-69,72] and “telemedicine” [29,31,32,38,39,46,47,51,59,61,63,69,71] being the most frequent. The following terms were also mentioned: teleconsultation [40,58,71], virtual visit [41,48,58], virtual health/eHealth [35,51], remote consultation [37,50,56,65], electronic consultation [35,62], telephone follow-up [35,66], video visit [35,70], video consultation [34,49], online consultation [69], virtual care [53], web-based video consultation [69], digital monitoring [72], nonpresential consultation [52], and remote self-monitoring [43]. Figure 3 shows the word cloud representing the most commonly used nomenclatures.

Figure 3.

Word cloud with nomenclatures used to refer to digital strategies in primary health care.

Types of ICT Employed

A total of 39 of the 44 studies (89%) mentioned the types of ICT used in PHC. Telephone calls had the highest number of records (29/39, 74%) [30,31,33-38,40,44-48, 50,52,53,55-60,62,65,66,69,70,72], followed by video calls (25/39, 64%) [30,31,33-41,43-48,55,60,62-65,69,72], patient portal (11/39, 28%) [31,33,35-37,40,42,44,58,61,72], smartphone apps (5/39, 13%) [44,49,52,54,68], text messages (3/39, 8%) [35,46,60], email (3/39, 8%) [46,62,72], electronic medical record (2/39, 5%) [31,72], and social networks (1/39, 3%) [46]. We highlight that many studies used more than one type of technology, mainly phone and video calls.

Moreover, the following electronic platforms and apps were used to conduct services: WhatsApp, Updox, Epic MyChart, Doximity, Facetime, Skype, Zoom, Telegram, iCARE-DATA, Babylon GP at Hand (BGPaH), EyerCloud, DRiQ, Aid Access, Telus PS Suite, eVisit Ontario Telemedicine Network, and Multimorbidity Management Health Information System (METHIS).

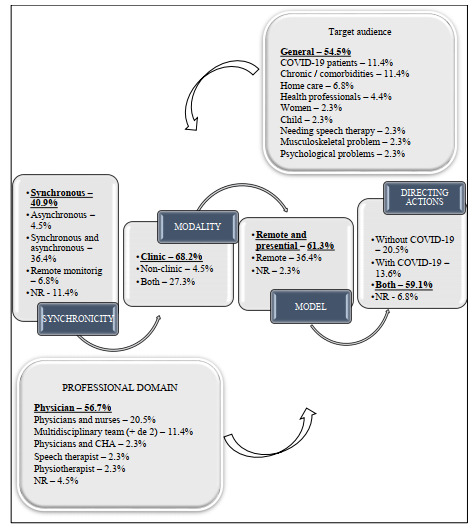

Characteristics of Digital Strategies in PHC

We analyzed the target audience, professionals involved, direction, synchronicity, and modality and model of actions in PHC (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Characteristics of remote strategies in primary health care.

Actions were mostly directed to the general public (ie, any health status or characteristic) [29,31,32,34-36,38,40-42, 44,46,48,49,51,53,55,56,58-60,63,67,71]. Regarding professionals who conducted the actions, the majority were clinicians [29-31, 34, 36-38, 42, 44-46, 49-51, 54, 55, 57, 58, 60, 63-66, 69, 71, 72] and nurses [35,39,41,43,47,48,56,70,72]. Actions were directed toward people with and without COVID-19 [31,32,34,36,38,40,42, 44,49,51,53-56,58-63, 65,67,68,70-72]. Synchronous interaction [31-33, 40,42,44-46,51,52,54,63-66,68,70,71] was the most frequently reported interaction type. The clinical modality was the most commonly reported [29-31, 33, 36-38, 40-46, 48-52, 54, 58-60, 63, 65-67, 69, 71, 72], referring to the following actions: consultations, renewal of medical prescriptions, exams, follow-up, health guidelines, issuance of certificates, treatments, screening, monitoring, diagnosis, management of chronic conditions, referrals, clinical self-monitoring, and risk classification. Remote consultation associated with in-person actions was the most prevalent model [29-32,34-38,40,42-46,49,51,53,54,56,57,60-64,67].

Impacts on Quality of Care

Studies reported the impacts of remote strategies on technical, interpersonal, or organizational dimensions of quality of care. Positive impacts were highlighted in 19 of the 44 (43%) studies [31,33,34,38,41,42,45,47-50, 52,56,57,60,62,64,65,70], negative impacts were mentioned in 6 (14%) studies [36,40,51,53,63,69], and positive and negative impacts were mentioned in 19 (43%) studies [29, 30, 32, 35, 37, 39, 43, 44, 46, 54, 55, 58, 59, 61, 66-68, 71, 72].

Technical [29-31,33-40,42-44,46,47,49-69,71,72] and organizational [29-43,45-50,52-61,64,65,67-72] dimensions were the most cited, followed by the interpersonal dimension [31,35-43,46-48,52,53,55,59,64,65,67-70,72]. More than one dimension of quality of care was directly or indirectly addressed in most studies.

Textbox 1 summarizes the positive and negative impacts on dimensions of quality of care evidenced in the studies.

Impacts on dimensions of quality of care.

Technical dimension

Positive impacts

Security in care provision [31,33,35,37,38,42,43,46,49,52,55,57-59,61,64,66,67,71,72]

Technical quality of information and communication technology [31,34,49,52,57,60,62,68]

Utility [30]

Attendance [56]

Privacy [31]

Negative impacts

Technical inaccuracy/inaccuracy [36,37,46,53,55,59,61,69,72]

Lack of assessment of vital signs and physical exams [29,59,63,69]

Discrepancy between professional conduct [66]

Interpersonal dimension

Positive impacts

Trust and bond with professionals improved adherence [43,47,48,65,67,68,70,72]

Humanization of care [31]

Negative impacts

Loss of nonverbal communication; lack of eye contact or touch [36,43,53,55,59,68,69,72]

Interpersonal communication hampered by technology, speed of consultation, or memory difficulties of patients [39,40,53,59,69]

Fear of not being resolutive compared with face-to-face modality; insecurity [35,37]

Organizational domain

Positive impacts

Continuous care [32-34,38,39,42,43,47,48,54-57,59,60,65,67,68,70]

Economic, social, geographical, time, and cultural accessibility [29,31,34,38,42,52,54,55,57,67,70-72]

User-friendly technologies [33]

Community engagement [37]

Negative impacts

Reduced access; evidence of inequity [32,35-37,39,40,54,55,59,69]

Lack of planning in defining the role of the team; disarticulation between actions and needs of the population [37,46,53,55,59,69,71]

Reduced training of professionals using information and communication technology [37,53,54,59,61,69]

Reduced coordination of care; fragile remote-presential articulation [37,46,54,55,68]

Reduced active search in the community [53]

Benefits, Limitations, and Challenges of Digital Strategies in PHC

The following benefits of digital strategies in PHC were highlighted in the studies: (1) acceptability and patient satisfaction [29,31,34,36,38,43-45,47,52,54,56-58,62-64,67,68]; (2) great possibility of sustainability in the postpandemic period [31,32,38,40,43,54,55,58,62,64,68-72]; (3) increased frequency of people seeking care in PHC, especially in remote areas with difficult access and little face-to-face demand [29,34-36,41,46,49,50,53, 55,59,70-72]; (4) great safety against COVID-19 transmission [33,35,38,42,47,54, 55,57-59,61,66,71,72]; (5) time and cost savings due to geographic displacements [33,34,36,38, 43,49,55,63,68,70,72]; (6) organization of work process and scheduling of face-to-face and remote demands [31,39,41,47,48,53,54,63]; (7) faster service [33,52-54,61,66-68]; (8) reduced need for referrals to secondary care and hospitalizations [33,35,44,50,52,57,65]; (9) great comfort and practicality [34,36,42,43,68,72]; (10) optimization of training, meetings, and education of professionals [31,33,41,49,59]; (11) opportunity to be present in patients’ lives, which benefits emotional health [30,32,43,44]; (12) fast home screening in cases of clinical changes [31,44,57]; (13) better communication with patients [46,64]; (14) great facility of use of technological tools and opportunity to overcome technological limitations [52,64]; (15) advantage of video calls over other tools [39,63]; (16) possibility of choosing the attendance modality [54]; (17) anonymity in situations that generate stigma, such as abortion care [42]; and (18) increased possibility of contacting inaccessible patients [61].

Conversely, the following limitations and challenges of digital strategies in PHC were identified: (1) difficulty in accessing internet, poor connectivity, digital divide (ie, more people with access to telephones and less to video calls) or digital desert (ie, people without access to technologies) [32-36,38-40,42,45-47,54,55,59,64,67,68,72]; (2) increased need for training professionals and the population regarding digital health [36,37,39-41,44-47,50,51,55,59,61,66,69-71]; (3) great diagnostic imprecision and professional misconduct due to absence of physical examinations [39,43,52, 54-56,59-61,65,68,69,72]; (4) inconsistent platforms, with errors in data storage, limited resources, or both [31,33,38,41,43,45,58,60,64,68,71]; (5) difficult communication with the elderly, children, and people with disabilities or dementia [37-39,46,48,53,55,59,69]; (6) lack of planning regarding management of services [40,41,46,52,54,55,61,71]; (7) uncertainty about privacy and confidentiality of personal data [35,36,41,61,63,66,67]; (8) rapid implementation of remote services without prior guarantee of equitable access [30,42,55,63,71,72]; (9) poor support from information technology professionals [31,36,41,43,66,71]; (10) great need for good articulation between remote and face-to-face modalities to meet demands [39,40,60,63,70]; (11) mental stress in health workers [37,43,46,55,59]; (12) lack of health professionals, high turnover of professionals, or both [37,54,57,59,67]; (13) possible increase of chronic conditions (eg, certain groups of people who stopped seeking services) and side effects due to excessive self-medication [53,55,58,59]; (14) telephone calls are used but not resolutive [34,35,53,64]; (15) low acceptability of professionals toward new remote workflows [46,51,55]; (16) difficult clinical monitoring of patients at home [51,57,64]; (17) difficulty regarding early identification of more complex health demands [31,59,69]; (18) delayed administrative tasks of health teams due to increased care demands [47,59]; (19) fast and urgent care [53,54]; (20) difficult articulation between professionals to meet more complex demands [44,54]; (21) difficulty regarding referral to other services [46]; (22) poor resolution in situations of risk at home (ie, domestic violence) [72]; (23) reduced supply of services [32]; and (24) difficulty in long-term follow-up of patients [49].

Discussion

Main Findings and Relation to Existing Literature

This scoping review demonstrated that the COVID-19 pandemic impacted health care in PHC worldwide (ie, fast implementation or increased use of remote care strategies or both) to mitigate the pandemic and ensure continuity of activities [73]. Various terms to refer to remote strategies were found in the literature [8,74]. Beyond concepts, technologies and tools are important components for health care systems, supporting the interaction among health care professionals or between health care professionals and patients [9]. The WHO [13,14] suggests telemedicine or telehealth to define distance care using ICT, whose purpose is to provide health care services in situations where distance or geographic barriers hinder the provision of care. Recently, “digital health” was introduced as an umbrella term, covering the use of electronic and mobile technologies (eg, advanced computer science, artificial intelligence, and big data) to support health and emerging health care areas [75].

The WHO and others [75,76] highlight the importance of digital technologies for achieving sustainable development goals and the advance of universal health coverage as opportunities to face challenges of health systems (ie, delayed provision of care, and reduced demand, adherence, and geographic accessibility) and increase coverage, accessibility, and quality of actions.

Telephone and video consultations are efficient tools for offering digital health [77,78]. Although telephone may increase follow-up contact and is more accessible than tools that require an internet connection, the assessment of severity and health status is compromised due to the absence of eye contact [79].

Telephone and audio consultations were recognized as telehealth modalities during the COVID-19 pandemic to support social distancing [80]. Although video consultations were rare in many locations before the pandemic [77], they are superior to phone calls, mainly due to eye contact and better communication for building bonds. Nevertheless, technical problems are more frequent when using digital strategies, and people need a stable connection to the internet, which may raise questions about the relationship between equity and the type of technology used [81-84]. For greater benefits, the literature indicates that the use of technology should be simple, consistent with local workflows, convenient for users, offer advantages over face-to-face consultations [76,85,86], and complement other existing technologies.

Results of this study corroborate with those of Breton et al [87], in which phone calls and video calls were identified as the most frequently used remote technologies, especially in the first months of the pandemic. We highlight that communication between health services users and professionals, mainly regarding platforms that ensure safety and reliability in the context of health care [88], is an important measure to be adopted due to the increased offer of newly developed applications.

The results of this scoping review also revealed the positive and negative impacts of remote strategies on quality of care in PHC worldwide, suggesting different types of organization (eg, fast or urgent implementation) of digital strategies. Safe offer of care, technical quality and accuracy, and resolvability were the positive impacts most frequently reported in the technical dimension. By contrast, technical inaccuracy or imprecision, consultations with poor quality, lack of detailed physical examination, and selective solving of problems were also observed.

The interpersonal dimension was characterized by trust and bond with professionals that facilitated adherence to technologies, increased the possibility of talking to someone, alleviated loneliness caused by isolation, and improved respect between professionals and patients. From another perspective, we also found loss of nonverbal communication, lack of physical contact, difficult communication aggravated by technologies, and negative and stressful emotional load among professionals as negative impacts.

The impacts in the organizational dimension were the most frequently identified in the included studies, which strengthened continuity of care; economic, social, geographical, time, and cultural accessibility; coordination of care; access; integrality of care; and optimization of appointment time and efficiency. Negative impacts were also observed in this dimension, such as reduced access to services, inequity, and unequal use of services offered; digital exclusion of part of the population due to lack of technologies, connectivity, or knowledge regarding use; reduced integrality of care; lack of planning for defining the role of professionals; disarticulation of actions with real needs of the population; impaired continuity of care; reduced coordination of care; fragile articulation between remote and face-to-face modalities; and unpreparedness of professionals to meet demands mediated by ICT.

One study [89] that verified how the pandemic impacted primary care services suggested digital health as an inflection point for PHC and the only alternative for restructuring the workflow of health care providers during the pandemic. The latter may have also contributed to the impaired quality of health care, especially for the elderly and people with preexisting health conditions (ie, psychological problems, addictions, or victims of domestic violence).

Issues limiting technological barriers and ethics in the use of information might be linked to work organization, health financing, and lack of familiarity of professionals and patients [6]. When properly available, patients considered digital health to be satisfactory and safe, and felt comfortable when trusting relationships with professionals and person-centered practices were present.

In PHC, preexisting virtual solutions to COVID-19 served as opportunities to support public health responses in combating the pandemic and minimizing the risk of exposure [90-93]. The adaptation of health systems based on PHC and training of professionals regarding the use of digital tools to fulfill clinical responsibilities, which previously required face-to-face contact, were also useful [90]. Studies also highlighted the relevance of digital strategies in preventive and health promotion actions, such as remote monitoring of clinical signs; management of chronic diseases and medication; and guidance on healthy lifestyle, exercises, and eating habits [94,95].

Studies conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated the importance of digital health in expanding access in PHC [82,96,97], even though face-to-face care was preferred [98]. Positive experiences were associated with planning according to the health needs of the population [99-101], whereas health professionals complained about insufficient remuneration, unavailability of technologies, and lack of standardization [102,103]. Based on these prepandemic experiences, digital strategies in PHC were an option to mitigate barriers and increase access for hard-to-reach populations. During periods of greater restriction and social isolation due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the reality of virtual assistance was extrapolated beyond populations with difficulties in accessing services. This fact allowed us to observe different results regarding the strengthening of digital health or predominance of persistent problems that depended on decision-making factors of governance to provide broad coverage of technologies (complementary or alternative) to populations. In fact, in most situations, digital health was adopted without the support of a national strategy.

The results of this study emphasize the benefits, limitations, and challenges of remote strategies in PHC, offering lessons during a global public health crisis. In this sense, quality of care in PHC can still be improved with consolidation and advances in digital health.

Implications for Practice and Research

According to the Pan American Health Organization [104], ICTs are essential to increase access of citizens to high-quality PHC, regardless of their distance from large urban centers. Technologies are becoming the primary method in which people, governments, and health institutions work, communicate, and generate and exchange knowledge. In this context, we must reflect on how remote technologies and strategies can support and strengthen essential characteristics of PHC, since this is the first point of contact for people, and offers comprehensive, accessible, and community-based health care. PHC also offers health promotion and prevention, treatment of acute and infectious diseases, control of chronic diseases, palliative care, and rehabilitation to individuals, families, and communities [105].

This study demonstrates that the fast transition and expansion of digital health impacted access and quality of care in PHC worldwide, even considering that health needs, policies, management, and financing differ between countries. PHC must take advantage of the lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic, strengthen its response capacity, balance the offer of new modalities of care with expanded use of technologies, and be more equitable and accessible. In contrast, equity of health care supply is beyond the power of action of health professionals or management of local services, since it is a larger and structural problem that depends on the integrated actions and engagement of public and social policies.

PHC services must be aligned with the needs and satisfaction of the population, while efforts must be made to perform self-assessments and improve quality of in-person and remote processes. Planning and intersectoral articulation at the management level, along with investment in financial and human resources are essential to improve the cost-effectiveness of remote care. Furthermore, technical and operational infrastructure is imperative for using technologies, strengthening security and protection of the patients and professional data.

Services and actions exceeding needs increase costs and do not improve results regarding patient-centered care and needs [106,107]. Moreover, health outcomes are worse, and costs are high when care is not based on the needs of the population. For digital health strategies in PHC, Lillrank et al [108] recommend planning actions by homogeneous groups with similar health needs, and organizing the supply of care considering demand, severity, and duration of needs, according to demand and supply–based operating modes. This organization could also facilitate continuity of care and optimize the work process using remote strategies.

The identification of gaps in the literature is expected in scoping reviews. As the COVID-19 pandemic changed the provision of services at all levels of care worldwide (eg, expansion of remote care strategies), directions for future research are challenging because the long-term impacts are unknown. Based on the observations from this scoping review, we recommend the following primary studies focused on remote strategies in PHC, especially in countries that have not yet investigated the topics discussed here: (1) assess implementation and differences between health systems (either public and private or with different forms of management and financing) based on the principles of universality and universal coverage; (2) assess the effectiveness and safety of remote strategies between users, professionals, and health managers; (3) monitor the impacts of remote strategies on quality of care and investigate how to enhance quality; and (4) perform intervention studies to investigate innovative strategies or approaches to improve clinical practice. Moreover, systematic reviews with meta-analysis could be performed to (1) assess the impact of remote strategies on clinical outcomes in vulnerable populations and (2) follow-up of patients with COVID-19 complications using ICT.

Consultation With Stakeholders

In the consultation stage, stakeholders were asked about ideas for future research, applicability of the results, and dissemination strategies. From the perspective of the participants, this scoping review can stimulate development agencies to finance ICT in PHC; reflect on cost-effectiveness of digital health to achieve greater adherence to therapeutic plans, reduce disease transmission, and prevent injuries; demonstrate the benefits of using digital health for monitoring indicators, goals, and indices in PHC, and for health surveillance; and support health professionals with lessons learned for improving care in remote mode.

Regarding the possibilities of disseminating the results, the following suggestions were discussed: scientific dissemination (indexed journals, conferences, and workshops); disclosure by health secretariats; creation of networks with interested social agents; linking of agents to research groups to approximate academia from health services and the general population; meetings and debates with local and national health managers; and adaptation of dissemination of results according to the local culture, choosing the most accessible means of communication (ie, social networks).

When asked about ideas for future research, the following were suggested: action research with health managers and professionals focusing on solutions for digital inclusion of vulnerable populations; sectorial studies inserted in PHC (eg, sectional and intervention research designs regarding digital pharmaceutical and oral health care industries); studies investigating the acceptability of remote strategies by specific groups and its associated factors (eg, age, gender, socioeconomic status, preexisting health conditions, and beliefs); and long-term follow-up of patients using remote monitoring in PHC.

Strengths and Limitations

This scoping review is the first to broadly map evidence regarding the use of remote strategies in PHC and its impacts on quality of care in the context of COVID-19. The study met the criteria for scoping reviews [24,109], and followed methodological references, checklists, and published protocols [23].

We did not conduct a meta-analysis [23] or assess the quality of studies. However, these steps are not essential due to the exploratory and descriptive nature of a scoping review. The search was performed to retrieve the highest number of publications regarding the topic, rather than focusing on studies with the highest standards of scientific rigor. Even though databases for peer-reviewed publications and gray literature were included with no filter limits and a high-sensitivity search strategy was performed, we do not know to what extent relevant studies and important databases were included.

Conclusion

This review provides information on the use of digital strategies in PHC and its impacts on quality of care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Confronting a public health situation of such proportion sheds light on realities that were not as evident previously. Given the importance of digital health in the current global health situation and the possibility of integrating and advancing this strategy after the pandemic, primary care must strengthen its response capacity, expand ICT use, and manage challenges using scientific evidence.

The number of digital health initiatives launched worldwide without a scientific basis during the pandemic had its foundation in the health crisis. Digital health needs to be improved and expanded to strengthen primary care and health systems.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support provided by the Graduate Program in Health Sciences of the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte and the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior-Brazil (CAPES) (finance code 001). The authors thank Probatus Academic Services for providing scientific language translation, revision, and editing.

Abbreviations

- ICT

information and communication technology

- JBI

Joanna Briggs Institute

- PCC

Population, Concept, and Context

- PHC

primary health care

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses

- PRISMA-ScR

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews

- WHO

World Health Organization

Search strategy.

Data extraction spreadsheet (original language).

Stakeholders consultation guide.

Footnotes

Authors' Contributions: SAdCU, CRDVS, RHL, and MF-T planned the study. CRDVS and RHL performed article selection and data extraction, and SAdCU was the third reviewer. CRDVS, RHL, OdGBJ, and CSM performed the analysis and synthesis of results. CRDVS conducted the consultation with stakeholders. All authors contributed to writing the manuscript. SAdCU, MF-T, RAA, LVL, and SD critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine . Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donabedian A. An introduction to quality assurance in health care. New York: Oxford University Press; 2002. Epigenomics. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Champagne F, Hartz Z, Brousselle A. A apreciação normativa. In: Brousselle A, Champagne F, Contradriopoulos AP, Hartz Z, editors. Avaliação: conceitos e métodos. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Fiocruz; 2011. pp. 77–94. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donabedian A. Explorations in quality assessment and monitoring: the definition of quality and approaches to its assessment. Ann Arbor, MI: Health Administration Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rawaf S, Allen LN, Stigler FL, Kringos D, Quezada Yamamoto H, van Weel C, Global Forum on Universal Health Coverage Primary Health Care Lessons on the COVID-19 pandemic, for and by primary care professionals worldwide. Eur J Gen Pract. 2020 Dec;26(1):129–133. doi: 10.1080/13814788.2020.1820479. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32985278 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garattini L, Badinella Martini M, Mannucci PM. Improving primary care in Europe beyond COVID-19: from telemedicine to organizational reforms. Intern Emerg Med. 2021 Mar;16(2):255–258. doi: 10.1007/s11739-020-02559-x. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/33196973 .10.1007/s11739-020-02559-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liao C, Chang W, Yu W, Toh HS. Management of acute cardiovascular events in patients with COVID-19. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2020 Dec 30;21(4):577–581. doi: 10.31083/j.rcm.2020.04.140. https://www.imrpress.com/journal/RCM/21/4/10.31083/j.rcm.2020.04.140 .1609227829849-827432669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waqas A, Teoh SH, Lapão LV, Messina LA, Correia JC. Harnessing telemedicine for the provision of health care: bibliometric and scientometric analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2020 Oct 02;22(10):e18835. doi: 10.2196/18835. https://www.jmir.org/2020/10/e18835/ v22i10e18835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tuckson RV, Edmunds M, Hodgkins ML. Telehealth. N Engl J Med. 2017 Oct 19;377(16):1585–1592. doi: 10.1056/nejmsr1503323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stefos T, Carey K, Shen M, Poe S, Oh D, Moran E. The effect of telehealth services on provider productivity. Med Care. 2021 May 01;59(5):456–460. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001529.00005650-202105000-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Snoswell CL, Taylor ML, Comans TA, Smith AC, Gray LC, Caffery LJ. Determining if telehealth can reduce health system costs: scoping review. J Med Internet Res. 2020 Oct 19;22(10):e17298. doi: 10.2196/17298. https://www.jmir.org/2020/10/e17298/ v22i10e17298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wosik J, Fudim M, Cameron B, Gellad ZF, Cho A, Phinney D, Curtis S, Roman M, Poon EG, Ferranti J, Katz JN, Tcheng J. Telehealth transformation: COVID-19 and the rise of virtual care. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020 Jun 01;27(6):957–962. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa067. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32311034 .5822868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.WHO Global Observatory for eHealth . Telemedicine: opportunities and developments in Member States: report on the second global survey on eHealth. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14.A health telematics policy in support of WHO's Health-for-all strategy for global health development: report of the WHO Group Consultation on Health Telematics, 11-16 December, Geneva, 1997. World Health Organization, Institutional Repository for Information Sharing. 1997. [2021-11-20]. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/63857 .

- 15.Estrategia mundial sobre salud digital 2020–2025. World Health Organization, Institutional Repository for Information Sharing. 2020. [2021-11-20]. https://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_docman&view=download&category_slug=56-directing-council-spanish-

- 16.Mann DM, Chen J, Chunara R, Testa PA, Nov O. COVID-19 transforms health care through telemedicine: Evidence from the field. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020 Jul 01;27(7):1132–1135. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa072. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32324855 .5824298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhaskar S, Bradley S, Sakhamuri S, Moguilner S, Chattu VK, Pandya S, Schroeder S, Ray D, Banach M. Designing futuristic telemedicine using artificial intelligence and robotics in the COVID-19 era. Front Public Health. 2020 Nov 2;8:556789. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.556789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Webster P. Virtual health care in the era of COVID-19. Lancet. 2020 Apr 11;395(10231):1180–1181. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30818-7. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32278374 .S0140-6736(20)30818-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peters M, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Tricco A, Khalil H. Chapter 11: scoping reviews. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI manual for evidence synthesis. Adelaide, Australia: JBI Collaboration; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters MDJ, Horsley T, Weeks L, Hempel S, Akl EA, Chang C, McGowan J, Stewart L, Hartling L, Aldcroft A, Wilson MG, Garritty C, Lewin S, Godfrey CM, Macdonald MT, Langlois EV, Soares-Weiser K, Moriarty J, Clifford T, Tunçalp Ö, Straus SE. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018 Oct 02;169(7):467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/abs/10.7326/M18-0850?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3dpubmed .2700389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Method. 2005 Feb;8(1):19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010 Sep 20;5:69. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69. https://implementationscience.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 .1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silva CRDV, Lopes RH, de Goes Bay Júnior O, Fuentealba-Torres M, Arcêncio RA, da Costa Uchôa SA. Telemedicine in primary healthcare for the quality of care in times of COVID-19: a protocol. BMJ Open. 2021 Jul 12;11(7):e046227. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046227. https://bmjopen.bmj.com/lookup/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=34253666 .bmjopen-2020-046227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peters MDJ, Marnie C, Tricco AC, Pollock D, Munn Z, Alexander L, McInerney P, Godfrey CM, Khalil H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid Synth. 2020 Oct;18(10):2119–2126. doi: 10.11124/JBIES-20-00167.02174543-202010000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oliveira Araújo WC. Recuperação da informação em saúde. ConCI. 2020 Jul 10;3(2):100–134. doi: 10.33467/conci.v3i2.13447. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P, Stewart LA, PRISMA-P Group Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015 Jan 02;350:g7647. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g7647. http://www.bmj.com/lookup/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=25555855 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016 Dec 05;5(1):210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4. https://systematicreviewsjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4 .10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006 Jan;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alexander GC, Tajanlangit M, Heyward J, Mansour O, Qato DM, Stafford RS. Use and content of primary care office-based vs telemedicine care visits during the COVID-19 pandemic in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Oct 01;3(10):e2021476. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.21476. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.21476 .2771191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schweiberger K, Hoberman A, Iagnemma J, Schoemer P, Squire J, Taormina J, Wolfson D, Ray KN. Practice-level variation in telemedicine use in a pediatric primary care network during the COVID-19 pandemic: retrospective analysis and survey study. J Med Internet Res. 2020 Dec 18;22(12):e24345. doi: 10.2196/24345. https://www.jmir.org/2020/12/e24345/ v22i12e24345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olayiwola JN, Magaña C, Harmon A, Nair S, Esposito E, Harsh C, Forrest LA, Wexler R. Telehealth as a bright spot of the COVID-19 pandemic: recommendations from the virtual frontlines ("Frontweb") JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020 Jun 25;6(2):e19045. doi: 10.2196/19045. https://publichealth.jmir.org/2020/2/e19045/ v6i2e19045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Atherly A, Van Den Broek-Altenburg E, Hart V, Gleason K, Carney J. Consumer reported care deferrals due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and the role and potential of telemedicine: cross-sectional analysis. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020 Sep 14;6(3):e21607. doi: 10.2196/21607. https://publichealth.jmir.org/2020/3/e21607/ v6i3e21607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Judson TJ, Odisho AY, Neinstein AB, Chao J, Williams A, Miller C, Moriarty T, Gleason N, Intinarelli G, Gonzales R. Rapid design and implementation of an integrated patient self-triage and self-scheduling tool for COVID-19. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020 Jun 01;27(6):860–866. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa051. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32267928 .5817825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mills KT, Peacock E, Chen J, Zimmerman A, He H, Cyprian A, Davis G, Fuqua SR, Gilliam DS, Greer A, Gray-Winfrey L, Williams S, Wiltz GM, Winfrey KL, Whelton PK, Krousel-Wood M, He J. Experiences and beliefs of low-income patients with hypertension in Louisiana and Mississippi during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021 Feb 02;10(3):e018510. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.018510. https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/JAHA.120.018510?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3dpubmed . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tarn DM, Hintz C, Mendez-Hernandez E, Sawlani SP, Bholat MA. Using virtual visits to care for primary care patients with COVID-19 symptoms. J Am Board Fam Med. 2021 Feb 23;34(Supplement):S147–S151. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2021.s1.200241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adepoju O, Liaw W, Chae M, Ojinnaka C, Britton E, Reves S, Etz R. COVID-19 and telehealth operations in Texas primary care clinics: disparities in medically underserved area clinics. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2021;32(2):948–957. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2021.0073.S1548686921200302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ritchie CS, Gallopyn N, Sheehan OC, Sharieff SA, Franzosa E, Gorbenko K, Ornstein KA, Federman AD, Brody AA, Leff B. COVID challenges and adaptations among home-based primary care practices: lessons for an ongoing pandemic from a national survey. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021 Jul;22(7):1338–1344. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2021.05.016. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/34111388 .S1525-8610(21)00480-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Drerup B, Espenschied J, Wiedemer J, Hamilton L. Reduced no-show rates and sustained patient satisfaction of telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic. Telemed J E Health. 2021 Dec;27(12):1409–1415. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2021.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kalicki AV, Moody KA, Franzosa E, Gliatto PM, Ornstein KA. Barriers to telehealth access among homebound older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021 Sep;69(9):2404–2411. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17163. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/33848360 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chang JE, Lai AY, Gupta A, Nguyen AM, Berry CA, Shelley DR. Rapid transition to telehealth and the digital divide: implications for primary care access and equity in a post-COVID era. Milbank Q. 2021 Jun;99(2):340–368. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12509. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/34075622 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thies KM, Gonzalez M, Porto A, Ashley KL, Korman S, Lamb M. Project ECHO COVID-19: vulnerable populations and telehealth early in the pandemic. J Prim Care Community Health. 2021;12:21501327211019286. doi: 10.1177/21501327211019286. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/21501327211019286?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3dpubmed . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Godfrey EM, Thayer EK, Fiastro AE, Aiken ARA, Gomperts R. Family medicine provision of online medication abortion in three US states during COVID-19. Contraception. 2021 Jul;104(1):54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2021.04.026. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/33939985 .S0010-7824(21)00142-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Juarez-Reyes M, Mui HZ, Kling SM, Brown-Johnson C. Accessing behavioral health care during COVID: rapid transition from in-person to teleconferencing medical group visits. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2021 Feb 12;12:2040622321990269. doi: 10.1177/2040622321990269. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2040622321990269?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3dpubmed .10.1177_2040622321990269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bui V, Ackerman S. Hamilton Primary Care Virtual Care Survey Analysis. Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-term Care. [2021-11-20]. http://health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/publichealth/coronavirus/docs/2019_primary_care_guidance.pdf .

- 45.Mohammed HT, Hyseni L, Bui V, Gerritsen B, Fuller K, Sung J, Alarakhia M. Exploring the use and challenges of implementing virtual visits during COVID-19 in primary care and lessons for sustained use. PLoS One. 2021;16(6):e0253665. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0253665. https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0253665 .PONE-D-21-06021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Donnelly C, Ashcroft R, Bobbette N, Mills C, Mofina A, Tran T, Vader K, Williams A, Gill S, Miller J. Interprofessional primary care during COVID-19: a survey of the provider perspective. BMC Fam Pract. 2021 Feb 03;22(1):31. doi: 10.1186/s12875-020-01366-9. https://bmcfampract.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12875-020-01366-9 .10.1186/s12875-020-01366-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Araujo Gomes de Castro F, Oliveira dos Santos ?, Valadares Labanca Reis G, Brandão Viveiros L, Hespanhol Torres M, De Oliveira Junior PP. Telemedicina rural e COVID-19. Rev Bras Med Fam Comunidade. 2020 Jun 24;15(42):2484. doi: 10.5712/rbmfc15(42)2484. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dimer NA, Canto-Soares ND, Santos-Teixeira LD, Goulart BNGD. The COVID-19 pandemic and the implementation of telehealth in speech-language and hearing therapy for patients at home: an experience report. Codas. 2020;32(3):e20200144. doi: 10.1590/2317-1782/20192020144. https://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2317-17822020000300401&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=en .S2317-17822020000300401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Queiroz MS, de Carvalho JX, Bortoto SF, de Matos MR, das Graças Dias Cavalcante C, Andrade EAS, Correa-Giannella ML, Malerbi FK. Diabetic retinopathy screening in urban primary care setting with a handheld smartphone-based retinal camera. Acta Diabetol. 2020 Dec;57(12):1493–1499. doi: 10.1007/s00592-020-01585-7. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32748176 .10.1007/s00592-020-01585-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Silva RSD, Schmtiz CAA, Harzheim E, Molina-Bastos CG, Oliveira EBD, Roman R, Umpierre RN, Gonçalves MR. The role of telehealth in the Covid-19 pandemic: a Brazilian experience. Cien Saude Colet. 2021 Jun;26(6):2149–2157. doi: 10.1590/1413-81232021266.39662020. https://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1413-81232021000602149&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=en .S1413-81232021000602149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sahni M, Choudhry J, Mittal A, Bhogal G. Remote musculoskeletal consultations: a survey of general practitioner registrars' level of confidence, acceptability, and management. Cureus. 2021 May 18;13(5):e15084. doi: 10.7759/cureus.15084. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/34150413 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Leung K, Qureshi S. Managing high frequency users of an electronic consultation system in primary care: a quality improvement project. BMJ Open Qual. 2021 Jun;10(2):e001310. doi: 10.1136/bmjoq-2020-001310. https://bmjopenquality.bmj.com/lookup/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=34112657 .bmjoq-2020-001310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tuijt R, Rait G, Frost R, Wilcock J, Manthorpe J, Walters K. Remote primary care consultations for people living with dementia during the COVID-19 pandemic: experiences of people living with dementia and their carers. Br J Gen Pract. 2021 Aug;71(709):e574–e582. doi: 10.3399/BJGP.2020.1094. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/33630749 .BJGP.2020.1094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Salisbury C, Quigley A, Hex N, Aznar C. Private video consultation services and the future of primary care. J Med Internet Res. 2020 Oct 01;22(10):e19415. doi: 10.2196/19415. https://www.jmir.org/2020/10/e19415/ v22i10e19415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Murphy M, Scott LJ, Salisbury C, Turner A, Scott A, Denholm R, Lewis R, Iyer G, Macleod J, Horwood J. Implementation of remote consulting in UK primary care following the COVID-19 pandemic: a mixed-methods longitudinal study. Br J Gen Pract. 2021;71(704):e166–e177. doi: 10.3399/BJGP.2020.0948. https://bjgp.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=33558332 .BJGP.2020.0948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Saiz Llamosas J, Pérez García R. Eficacia del tratamiento fisioterápico en atención primaria, mediante consulta no presencial, a un paciente dado de alta de neumonía por Coronavirus. Fisioterapia. 2021 Jan;43(1):58–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ft.2020.09.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Coronado-Vázquez Valle, Ramírez-Durán MDV, Gómez-Salgado Juan, Dorado-Rabaneda MS, Benito-Alonso E, Holgado-Juan M, Bronchalo-González C. Evolution of a cohort of COVID-19 infection suspects followed-up from primary health care. J Pers Med. 2021 May 24;11(6):459. doi: 10.3390/jpm11060459. https://www.mdpi.com/resolver?pii=jpm11060459 .jpm11060459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Morreel S, Philips H, Verhoeven V. Organisation and characteristics of out-of-hours primary care during a COVID-19 outbreak: a real-time observational study. PLoS One. 2020;15(8):e0237629. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237629. https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0237629 .PONE-D-20-15141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Verhoeven V, Tsakitzidis G, Philips H, Van Royen P. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the core functions of primary care: will the cure be worse than the disease? A qualitative interview study in Flemish GPs. BMJ Open. 2020 Jun 17;10(6):e039674. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039674. https://bmjopen.bmj.com/lookup/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=32554730 .bmjopen-2020-039674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Johnsen TM, Norberg BL, Kristiansen E, Zanaboni P, Austad B, Krogh FH, Getz L. Suitability of video consultations during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown: cross-sectional survey among Norwegian general practitioners. J Med Internet Res. 2021 Feb 08;23(2):e26433. doi: 10.2196/26433. https://www.jmir.org/2021/2/e26433/ v23i2e26433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lapão LV, Peyroteo M, Maia M, Seixas J, Gregório João, Mira da Silva M, Heleno B, Correia JC. Implementation of digital monitoring services during the COVID-19 pandemic for patients with chronic diseases: design science approach. J Med Internet Res. 2021 Aug 26;23(8):e24181. doi: 10.2196/24181. https://www.jmir.org/2021/8/e24181/ v23i8e24181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Florea M, Lazea C, Gaga R, Sur G, Lotrean L, Puia A, Stanescu AMA, Lupsor-Platon M, Florea H, Sur ML. Lights and shadows of the perception of the use of telemedicine by Romanian family doctors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Gen Med. 2021;14:1575–1587. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S309519.309519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mueller M, Knop M, Niehaves B, Adarkwah CC. Investigating the acceptance of video consultation by patients in rural primary care: empirical comparison of preusers and actual users. JMIR Med Inform. 2020 Oct 22;8(10):e20813. doi: 10.2196/20813. https://medinform.jmir.org/2020/10/e20813/ v8i10e20813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kludacz-Alessandri M, Hawrysz L, Korneta P, Gierszewska G, Pomaranik W, Walczak R. The impact of medical teleconsultations on general practitioner-patient communication during COVID-19: a case study from Poland. PLoS One. 2021;16(7):e0254960. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0254960. https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0254960 .PONE-D-21-15441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zeltzer D, Einav L, Rashba J, Balicer R. The impact of increased access to telemedicine. Stanford. [2021-11-20]. http://web.stanford.edu/~leinav/wp/telemed.pdf .

- 66.Hasani SA, Ghafri TA, Al Lawati H, Mohammed J, Al Mukhainai A, Al Ajmi F, Anwar H. The use of telephone consultation in primary health care during COVID-19 pandemic, Oman: perceptions from physicians. J Prim Care Community Health. 2020;11:2150132720976480. doi: 10.1177/2150132720976480. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2150132720976480?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3dpubmed . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Alharbi K, Aldosari M, Alhassan A, Alshallal K, Altamimi A, Altulaihi B. Patient satisfaction with virtual clinic during coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic in primary healthcare, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. J Fam Community Med. 2021;28(1):48. doi: 10.4103/jfcm.jfcm_353_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jannati N, Nakhaee N, Yazdi-Feyzabadi V, Tjondronegoro D. A cross-sectional online survey on patients' satisfaction using store-and-forward voice and text messaging teleconsultation service during the COVID‑19 pandemic. Int J Med Inform. 2021 Jul;151:104474. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2021.104474. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/33965682 .S1386-5056(21)00100-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Isautier JM, Copp T, Ayre J, Cvejic E, Meyerowitz-Katz G, Batcup C, Bonner C, Dodd R, Nickel B, Pickles K, Cornell S, Dakin T, McCaffery KJ. People's experiences and satisfaction with telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia: cross-sectional survey study. J Med Internet Res. 2020 Dec 10;22(12):e24531. doi: 10.2196/24531. https://www.jmir.org/2020/12/e24531/ v22i12e24531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Javanparast S, Roeger L, Kwok Y, Reed RL. The experience of Australian general practice patients at high risk of poor health outcomes with telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2021 Apr 08;22(1):69. doi: 10.1186/s12875-021-01408-w. https://bmcfampract.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12875-021-01408-w .10.1186/s12875-021-01408-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ervin K, Weller-Newton J, Phillips J. Primary healthcare clinicians. Aust J Prim Health. 2021 Mar 03;:158–162. doi: 10.1071/PY20182.PY20182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Imlach F, McKinlay E, Middleton L, Kennedy J, Pledger M, Russell L, Churchward M, Cumming J, McBride-Henry K. Telehealth consultations in general practice during a pandemic lockdown: survey and interviews on patient experiences and preferences. BMC Fam Pract. 2020 Dec 13;21(1):269. doi: 10.1186/s12875-020-01336-1. https://bmcfampract.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12875-020-01336-1 .10.1186/s12875-020-01336-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zandi D. Digital health and COVID-19. Bull World Health Organ. 2020 Nov 01;98(11):731–732. doi: 10.2471/BLT.20.021120. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/33177768 .BLT.20.021120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fatehi F, Wootton R. Telemedicine, telehealth or e-health? A bibliometric analysis of the trends in the use of these terms. J Telemed Telecare. 2012 Dec;18(8):460–464. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2012.gth108.jtt.2012.GTH108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Recommendations on digital interventions for health system strengthening. World Health Organization. 2019. [2021-11-20]. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241550505 . [PubMed]

- 76.Maia MR, Castela E, Pires A, Lapão LV. How to develop a sustainable telemedicine service? A Pediatric Telecardiology Service 20 years on - an exploratory study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019 Sep 23;19(1):681. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4511-5. https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-019-4511-5 .10.1186/s12913-019-4511-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Atherton H, Brant H, Ziebland S, Bikker A, Campbell J, Gibson A, McKinstry B, Porqueddu T, Salisbury C. The potential of alternatives to face-to-face consultation in general practice, and the impact on different patient groups: a mixed-methods case study. Health Serv Deliv Res. 2018 Jun;6(20):1–200. doi: 10.3310/hsdr06200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Thiyagarajan A, Grant C, Griffiths F, Atherton H. Exploring patients' and clinicians' experiences of video consultations in primary care: a systematic scoping review. BJGP Open. 2020;4(1):bjgpopen20X101020. doi: 10.3399/bjgpopen20X101020. http://bjgpopen.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=32184212 .bjgpopen20X101020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Huibers L, Moth G, Carlsen AH, Christensen MB, Vedsted P. Telephone triage by GPs in out-of-hours primary care in Denmark: a prospective observational study of efficiency and relevance. Br J Gen Pract. 2016 Sep;66(650):e667–73. doi: 10.3399/bjgp16X686545. https://bjgp.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=27432608 .bjgp16X686545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Uscher-Pines L, Jones M, Sousa J, Predmore Z, Ober A. The doctor will call me maybe: the uncertain future of audio-only visits and why we need them to address disparities. The Rand Blog. 2021. Mar 12, [2021-11-01]. https://www.rand.org/blog/2021/03/the-doctor-will-call-me-maybe-the-uncertain-future.html .

- 81.Donaghy E, Atherton H, Hammersley V, McNeilly H, Bikker A, Robbins L, Campbell J, McKinstry B. Acceptability, benefits, and challenges of video consulting: a qualitative study in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2019 Sep;69(686):e586–e594. doi: 10.3399/bjgp19X704141. https://bjgp.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=31160368 .bjgp19X704141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Randhawa RS, Chandan JS, Thomas T, Singh S. An exploration of the attitudes and views of general practitioners on the use of video consultations in a primary healthcare setting: a qualitative pilot study. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2019 Jan;20:e5. doi: 10.1017/S1463423618000361. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/29909798 .S1463423618000361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lawson E, Kumar S. The Wass report: moving forward 3 years on. Br J Gen Pract. 2020 Apr;70(693):164–165. doi: 10.3399/bjgp20X708953. https://bjgp.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=32217573 .70/693/164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Greenhalgh T, Wherton J, Shaw S, Morrison C. Video consultations for covid-19. BMJ. 2020 Mar 12;368:m998. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Greenhalgh T, Wherton J, Papoutsi C, Lynch J, Hughes G, A'Court C, Hinder S, Fahy N, Procter R, Shaw S. Beyond adoption: a new framework for theorizing and evaluating nonadoption, abandonment, and challenges to the scale-up, spread, and sustainability of health and care technologies. J Med Internet Res. 2017 Nov 01;19(11):e367. doi: 10.2196/jmir.8775. https://www.jmir.org/2017/11/e367/ v19i11e367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Farr M, Banks J, Edwards HB, Northstone K, Bernard E, Salisbury C, Horwood J. Implementing online consultations in primary care: a mixed-method evaluation extending normalisation process theory through service co-production. BMJ Open. 2018 Mar 19;8(3):e019966. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019966. https://bmjopen.bmj.com/lookup/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=29555817 .bmjopen-2017-019966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Breton M, Deville-Stoetzel N, Gaboury I, Smithman MA, Kaczorowski J, Lussier M, Haggerty J, Motulsky A, Nugus P, Layani G, Paré G, Evoy G, Arsenault M, Paquette J, Quinty J, Authier M, Mokraoui N, Luc M, Lavoie M. Telehealth in primary healthcare: a portrait of its rapid implementation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Healthc Policy. 2021 Aug;17(1):73–90. doi: 10.12927/hcpol.2021.26576. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/34543178 .hcpol.2021.26576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Coronavirus (COVID-19): Guide de soutien pour la mise en œuvre des téléconsultations dans les établissements de santé du Québec dans le contexte de pandémie. Telesante Quebec. 2020. [2021-11-20]. https://telesantequebec.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/20_210_133W_Guide_mise_en_oeuvre_teleconsultations_pandemie_MSSS_V2_VF.pdf .

- 89.Lim J, Broughan J, Crowley D, O'Kelly B, Fawsitt R, Burke MC, McCombe G, Lambert JS, Cullen W. COVID-19's impact on primary care and related mitigation strategies: a scoping review. Eur J Gen Pract. 2021 Dec;27(1):166–175. doi: 10.1080/13814788.2021.1946681. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/34282695 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Neves AL, Li E, Gupta PP, Fontana G, Darzi A. Virtual primary care in high-income countries during the COVID-19 pandemic: policy responses and lessons for the future. Eur J Gen Pract. 2021 Dec;27(1):241–247. doi: 10.1080/13814788.2021.1965120. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/34431426 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Jnr BA. Use of telemedicine and virtual care for remote treatment in response to COVID-19 pandemic. J Med Syst. 2020 Jun 15;44(7):132. doi: 10.1007/s10916-020-01596-5. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32542571 .10.1007/s10916-020-01596-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Car J, Koh GC, Foong PS, Wang CJ. Video consultations in primary and specialist care during the covid-19 pandemic and beyond. BMJ. 2020 Oct 20;371:m3945. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Jnr BA. Implications of telehealth and digital care solutions during COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative literature review. Inform Health Soc Care. 2021 Mar 02;46(1):68–83. doi: 10.1080/17538157.2020.1839467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Telehealth to expand access to essential health services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. Jun 10, [2021-12-30]. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/telehealth.html .

- 95.Gerke S, Stern AD, Minssen T. Germany's digital health reforms in the COVID-19 era: lessons and opportunities for other countries. NPJ Digit Med. 2020;3:94. doi: 10.1038/s41746-020-0306-7.306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Seto E, Smith D, Jacques M, Morita PP. Opportunities and challenges of telehealth in remote communities: case study of the Yukon telehealth system. JMIR Med Inform. 2019 Nov 01;7(4):e11353. doi: 10.2196/11353. https://medinform.jmir.org/2019/4/e11353/ v7i4e11353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]