Abstract

Background

We explored perceptions and preferences regarding the conversion of in-person to virtual conferences as necessitated by travel and in-person meeting restrictions.

Methods

A 16-question online survey to assess preferences regarding virtual conferences during the COVID-19 pandemic and future perspectives on this subject was disseminated internationally online between June and August 2020.

Findings

A total of 508 responses were received from 73 countries. The largest number of responses came from Italy and the USA. The majority of respondents had already attended a virtual conference (80%) and would like to attend future virtual meetings (97%). The ideal duration of such an event was 2–3 days (42%). The preferred time format was a 2–4-h session (43%). Most respondents also noted that they would like a significant fee reduction and the possibility to attend a conference partly in-person and partly online. Respondents indicated educational sessions as the most valuable sections of virtual meetings. The reported positive factor of the virtual meeting format is the ability to re-watch lectures on demand. On the other hand, the absence of networking and human contact was recognized as a significant loss. In the future, people expressed a preference to attend conferences in person for networking purposes, but only in safer conditions.

Conclusions

Respondents appreciated the opportunity to attend the main radiological congresses online and found it a good opportunity to stay updated without having to travel. However, in general, they would prefer these conferences to be structured differently. The lack of networking opportunities was the main reason for preferring an in-person meeting.

Key Points

• Respondents appreciated the opportunity to attend the main radiological meetings online, considering it a good opportunity to stay updated without having to travel.

• In the future, it is likely for congresses to offer attendance options both in person and online, making them more accessible to a larger audience.

• Respondents indicated that networking represents the most valuable advantage of in-person conferences compared to online ones.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00330-022-08903-3.

Keywords: Videoconferencing, Survey, Radiology

Introduction

The spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) from Wuhan, Hubei region, People’s Republic of China, in late 2019 [1] imposed drastic changes to almost all aspects of our lives. The spread of the virus was rapid due to the highly interconnected nature of the world and on the 11th of March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) labeled the disease as a pandemic [2]. A response to this spread was the national lockdowns with the closing of borders around the world and variably strict restrictions on the size of public gatherings [3]. Consequently, the scientific community was forced to cancel scheduled international and national scientific meetings, or convert them into a newly designed virtual format [4, 5]. Virtual meetings which were previously limited to small groups had to be rapidly adapted for large national and international audiences [6–10]. Several papers have already explored the emerging standards for organizing scientific events during and after the pandemic highlighting the future trend towards hybrid events, which should become a part of routine practice in the scientific community [11–14].

While already present prior to the pandemic period, virtual conferences were not as prevalent [5]. Several institutions or journals had already developed an online presence through webinars and podcasts, such as the European Society of Medical Imaging Informatics Webinar Series (https://www.eusomii.org/webinars/) [15]. In the initial phases of travel and meeting limitations, some societies, including the Radiological Society of North America and the European Society of Radiology, streamed their annual meetings in part or entirely. However, the global lockdown eventually required a transition of all annual meetings to a virtual format. While successful meetings of this kind had already been organized by Academic Centers (e.g., in Austria and Germany), the crisis allowed us to further improve this format through widespread adoption and shared experience. However, while the online format surely presented some advantages and was a necessary solution in a time of crisis, in-person congresses are primed for returning to prominence in the near future. The latter also present several distinct aspects, such as networking, that are not easy to replicate in a virtual setting.

The aim of this survey was to evaluate the perceptions and preferences of attendees when converting in-person meetings to virtual ones and to propose an ideal future meeting format. These could allow us to gain insights which can be useful for the improvement of congress organization after this time of crisis.

Methods

An online survey was developed by an international group of radiologists as an online questionnaire on Survey Monkey (SurveyMonkey Inc.). The survey was designed and tested by all the authors, board-certified radiologists, prior to its dissemination. The survey was anonymous and contained a total of 16 questions (Table 1) focused on the preferences of attendees comparing in-person to virtual meetings. It was disseminated via e-mail to all members of The European Society of Neuroradiology (ESNR) (two times) and more broadly to an international radiologist audience via social media using the author’s personal accounts (Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn). The audience was mixed, and the authors decided to not include distinction between radiologists and neuroradiologists in the collected data considering it not relevant for the survey aim. The survey was conducted between June and August of 2020.

Table 1.

Survey design

|

1. Role - Medical student - Resident/fellow - Radiologist | |

|

2. Age - 18-24 - 25-34 - 35-44 - 45-54 - 55-64 - 65+ | |

|

3. Sex - Male - Female - Other | |

| 4. Country of current professional activity | |

|

5. Have you already attended a virtual meeting? - Yes - No | |

|

6. Would you consider attending a virtual meeting? - Yes - No | |

|

7. What do you consider to be the ideal duration of a virtual meeting? - Half a day - One day - 2-3 days - 4+ days | |

|

8. What session formula do you prefer for the virtual meeting? - Same as in-person, live meeting - 1-hour meeting - 2-4 hours meeting, with 1-2 breaks - 5-7 hours, with 2-3 breaks | |

|

9. Do you think the registration fee for a virtual meeting should be less expensive than for a live meeting, and if yes how much less? - Around the same - 25% less - 50% less - 75% less - 90% less | |

|

10. Would you be willing to pay for attending a virtual meeting? - Yes, for the whole event - Yes, but for key lectures only - Yes, but the price should depend on the number of sessions. - No | |

|

11. Would you prefer to attend the virtual or live version of a meeting if both are available? - I would prefer a virtual meeting - I would prefer to attend in person - I will try to find a combination of both | |

|

12. What part of a virtual meeting do you consider important? (Rank 1-5) a. Keynote b. Educational c. Abstract/scientific session d. Q&A session e. Open Forum f. Cases presentation | |

|

13. Benefit of virtual meetings (rank 1-5) a. Easier to attend distant meetings b. Easier to follow the lecture of a specific speaker c. Less financial burden than in-person, live meeting d. Possible to re-watch or follow asynchronously e. More efficient, no loss of time f. Better interaction with Q&A session g. Easier to speak up, less intimidating h. Better for accommodating childcare logistics i. Can hear everyone speaking | |

|

14. Negative factors of virtual meetings (rank 1-5) a. less networking opportunity b. no human contact c. difficult to attend because of overlap with work d. no CME accreditation always available e. I can’t attend virtual meetings of more than 1 hour f. too costly, or no reimbursement from hospital to attend meeting g. I’m not granted free time for such meetings h. Quality of connection (sound, video) not always optimal i. No scientific sessions j. Other | |

|

15. What factors will influence in person attendance at meetings going forward? (rank 1-5) a. Networking opportunity b. Committee meetings c. Desirable location d. Summer date e. Spring date f. Fall date g. Winter date h. CME i. Ability to present scientific data j. Attend scientific sessions k. No virtual meeting option l. Large size m. Opportunity to preview new products n. Safer health condition (vaccine availability) o. Other | |

| 16. Other comments |

The survey was divided into 4 sections:

Information about the respondent

Experience with virtual meetings

Preferences regarding virtual meetings

Future considerations

All questions were designed with multiple choice answers (with exception of question nos. 4 and 16: country and comments). A weighted average for each answer choice was calculated for rating scale questions, to better capture and understand variability. For this reason, we used the survey option to automatically assign weights to each rating scale question answer choice, corresponding to the presented Likert scale values.

To assess differences in responses due to role or age group, a Pearson’s chi-square or a Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test with post hoc analysis (pairwise comparisons using Wilcoxon rank sum test and Benjamini-Hochberg correction) was employed, as appropriate. All statistical tests were performed using R (R Core Team, 2022. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. URL https://www.R-project.org/).

Preliminary results of this survey were presented at the 2020 Virtual Annual Meeting of European Society of Medical Imaging Informatics (EUSOMII) [16].

Results

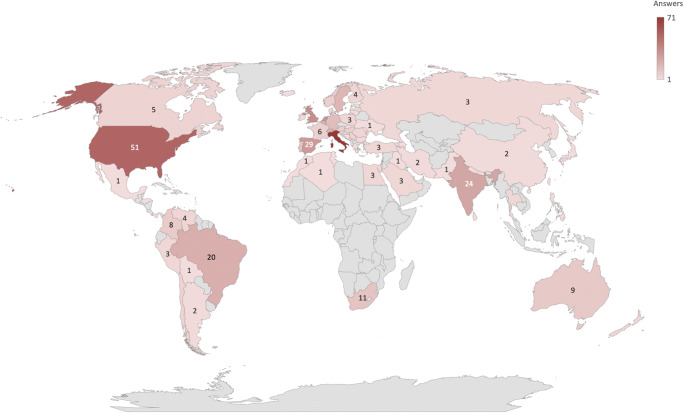

A total of 508 responses were received from an estimated audience of about 6,000 recipients. Most respondents were board-certified radiologists (431, 85%), followed by residents (66, 13%) and medical students (11, 2%) (Supplementary Table 1). Most respondents were aged between 25 and 54 years (35–44: 182, 36%; 45–54: 109, 21%; 25–34: 108, 21%), whereas other age groups were less represented (18–24: 7, 1%; 65+: 25, 5%) (Supplementary Table 2). Males (55%) represented a slightly higher number of respondents (Supplementary Table 3) and most responses were obtained from individuals working in Italy (71, 14%) and the USA (51, 10%). The demographics from respondents are summarized in Supplementary Table 4 and Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Distribution map of respondents

Four hundred three (80%) respondents had already attended a virtual meeting at the time of the survey (Supplementary Table 5) and 97% were interested in attending one in the future (Supplementary Table 6). Most respondents preferred either a 2–3 day (42%) or a half-day (33%) meeting with most respondents (43%) (Supplementary Table 7) selecting a 2–4-h meeting with 1–2 breaks as the preferred format (Supplementary Table 8). Most respondents indicated that the ideal price for the virtual meetings should be less than in-person meetings (50% less: 40%; 75% less: 36%) (Supplementary Table 9) and the majority (47%) would prefer a dynamic price dependent on the content selected (Supplementary Table 10).

There was no clear preference of meeting format with a relatively even split between a combination of virtual and in-person meeting (35%), in-person meeting (33%), and virtual meeting (32%) (Supplementary Table 11). The respondents found the educational aspect of virtual meetings to be most important (4.57 weighted average, WA), followed by keynote (3.91 WA), and case presentation (3.91 WA). The Q&A (3.31 WA), abstracts/scientific (2.94 WA), and open forum (2.78 WA) were considered less important (Fig. 2) (Supplementary Table 12).

Fig. 2.

Diagram of question 12 answer distribution

The ability to watch sessions on one’s own time or re-watch them (4.54 WA) was considered the most important benefit of virtual meetings. This was followed by the absence of need to travel (4.44 WA), lower costs (4.02 WA), and more time efficiency (3.95 WA). The ability to follow lectures more easily (3.89 WA) and hear clearly (3.31 WA) was also considered important. Better childcare logistics (3.08 WA), Q&A interactions (2.69 WA) and ease of speaking up (2.67 WA) were not as important (Fig. 3) (Supplementary Table 13).

Fig. 3.

Diagram of question 13 answer distribution

The most frequently selected negative aspects of virtual meetings included decreased networking opportunities (3.79 WA), no human contact (3.71 WA), absence of Continuing Medical Education (CME) for all sessions (3.19 WA), difficulty to attend due to overlap with clinical duties (3.12 WA), and network issues (3.05 WA) (Fig. 4) (Supplementary Table 14).

Fig. 4.

Diagram of question 14 answer distribution

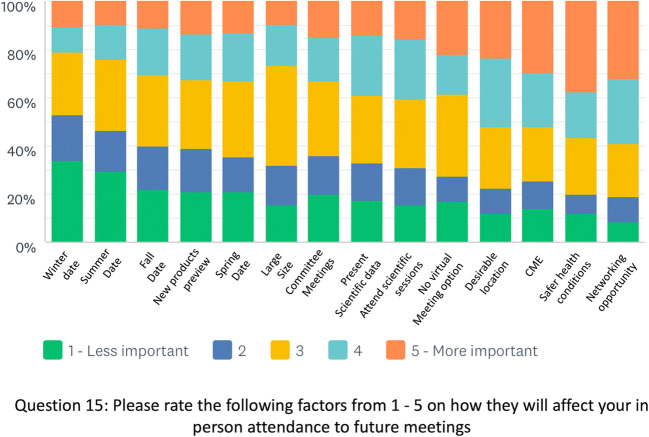

The most important factor driving people’s decision to attend in-person meetings again was the ability to network (3.74 WA). The other important factors included safer conditions such as a vaccination available (3.38 WA), desirable location (3.30 WA), and presence of CMEs (3.30 WA) (Fig. 5) (Supplementary Table 15).

Fig. 5.

Diagram of question 15 answer distribution

Regarding differences due to respondent role or age group, the results are presented in full in the supplementary materials with the relevant descriptive statistics (“test_results.doc” and “descriptive.xlsx” files).

Discussion

The pandemic event of the past years has impacted many aspects of our personal and work lives. Our customs in relation to conference and course attendance have also been affected. These changes may influence the post-pandemic reality in yet unforeseen ways. In particular, this transition to and evolution of virtual conferences was also driven by initiatives from individuals or smaller organizations, such as the International Pediatric Neuroradiology Teaching Group [6]. Obviously, technological advances also played a crucial role in facilitating this transition. In developed countries, most physicians own a smartphone or laptop and an access to the Internet, removing any barriers to meet or interact with others virtually. Unfortunately, this is not a global standard, and the pandemic further highlighted digital divide issues [17]. In the end, the current situation allowed for wider implementation and development of already-available technology, not widely used in this setting. This trend did not concern only conferences, as demonstrated by the explosion of virtual schooling, remote working, and increase of home activities that relied heavily on the Internet, even leading some entertainment companies to lower their bandwidth [18].

To our knowledge, this survey has been the only attempt to identify attendee preferences regarding the transition from in-person to online virtual conferences. The large majority of respondents were between the ages of 25 to 54, including a fairly broad age range.

The answers to questions 7–10 are of particular interest, reflecting the different approaches and possibilities to follow a virtual meeting. Physicians during the pandemic were required to work and preferred shorter meetings, limiting the days and time away from clinical practice. These preferences also highlight the potential advantage for physicians to follow virtual conferences from the workplace. Medical students indicated half a day as the ideal duration of a virtual meeting, while both radiologists and residents/fellows preferred a 2–3-days-long event. The same result was confirmed in the age group analysis.

Respondents also felt conference fees should be lower compared to an in-person meeting, presumably reflecting the absence of part of the expenditures related to in-person meetings (e.g., catering and venue hire). The possibility to modulate final price registering to specific sessions alone is also enticing. On the other hand, the end user may not yet be fully aware of the infrastructural costs tied to streaming and/or hosting of virtual conference presentations for on-demand access. This limitation may reduce the perceived value of registration costs in relation to the actual service provided. In regard to the willingness to pay for the event, radiologists are more likely to bear the cost for the whole congress, while medical students and residents/fellows significantly prefer free participation or to be charged based on the attended lectures.

It should also be noted that respondents wanted more educational sessions. A possible explanation is that virtual meetings often offer less opportunities for interaction with the speaker which may limit in turn discussions that normally occur during scientific sessions. Furthermore, students and residents/fellows assigned more value to abstract/scientific and Q&A sessions compared to radiologists.

We also investigated the positive and negative factors of virtual meetings. The most positively rated aspect of this format was the chance to easily switch between sessions: it is a crucial point for a virtual conference. This response further highlights that the flexibility provided by online platforms in terms of accessibility (e.g., from home or at work, from a phone or a personal computer) and selection (e.g., easy access to presentations of interest in different sessions, live or on demand) is their strong suit. This lesson should be taken into account even when in-person meetings will return to be the de facto standard.

Another very well-rated aspect was the possibility to follow more meetings by eliminating the need to travel. This is especially true for the countries farthest from the most important and/or common meeting locations. The virtual format expanded the audience of many congresses, and possibly included audiences from far countries that would have not previously attended. Further strengthening this consideration, the ESNR noted their Web Lectures webinar series were well attended by radiologists from India and Brazil. Not only did respondents highlight the convenience of attending virtually but also pointed out that it was more efficient and avoided loss of time.

Interestingly, highly rated options also included “can hear a specific speaker” and “hear everyone.” The online congress format allows the audience to follow the most important and “famous” lecturers more easily, potentially even if multiple speakers were live at the same time through on demand access. Respondents also rated the ability to earn CME as an important factor and should be a consideration for meetings in the future. CME is always an important factor in getting people to attend in-person meetings, and it is important to know that the lack of virtual meeting option could be a strong incentive to attend on site. Understandably, amid virtual meetings negative factors, medical students consider the lack of CME accreditation of little importance compared to radiologist.

We found mixed ratings for childcare logistics. Some organizations such as the RSNA [19] and ACR [20] have already made accommodations for childcare, and it is a concern for many attendees with children.

Considering negatively rated factors, respondents highlighted the reduced networking opportunities due to the absence of human contact. Social media usage to stimulate discussion during in-person meetings is now well known and studied [21–23]. The feedback we received shows that, despite the commitment by meeting organizers to stimulate discussions through the use of chat platforms and social media, further efforts and new tools may be necessary to address this point. The overlap of meetings during work hours was also reported as an issue, but this could be more easily solvable. For example, ensuring on demand availability of recorded lectures for a sufficient time frame after the congress could prove the most straightforward solution. While attending the meeting during work may be more efficient, this could be distracting and not ideal for patient care.

In looking to the future, most responders’ preferred choice for medical imaging conferences was a “combination of in-person and virtual meeting,” leaning into hybrid meeting format. This was not a common option prior to the pandemic. Certainly, this choice implies a greater organizational challenge as well as increased costs. Time will prove if these negative aspects can be balanced by greater attendance and new pricing models, making hybrid conferences become the “new normal.” As a reference example, we can consider the Consumer Electronics Show, the most influential tech event in the world hosted in Las Vegas since 1967, whose 2022 edition has been planned and took place in a hybrid format, after the 2021 virtual edition [24].

Respondents believe that the most likely reason to return to in-person meetings is represented by networking opportunities. This is consistent with other answers proving that attendants enjoy chatting with others during social events, at round table discussions, and in-between sessions. This is linked to another highly valued factor, “desirable location”, mixing the scientific purposes with the opportunity to enjoy appealing travel locations (e.g., landscapes, foods). This desirability is, however, currently tempered by an awareness about health safety with vaccination coverage rated high as a condition to attend an in-person meeting. After the first vaccine became available in December 2020 [25], and with the emergence of additional vaccines, we believe (and hope) these concerns may be mitigated. As a final consideration, it was interesting to note that the timing of conferences during the year was not considered a relevant factor.

Conclusions

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic may have established a “new normal” scenario for organizing scientific meetings. It is highly likely that in the future it will be possible to attend such events not only in person but also digitally, making them also more accessible to a larger audience, potentially reducing geographical and economic barriers to participation. The data presented in this survey, while still a limited sample compared to the entirety of the global imaging community, may be also useful in the design and planning of future meetings and continuing learning initiatives.

Supplementary information

(DOCX 54 kb)

(XLSX 22 kb)

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank European Society of Neuroradiology Central Office and Paola Rinaldi, European Society of Medical Imaging Informatics, for the support provided.

Abbreviations

- CME

Continued medical education

- COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 19

- ESNR

European Society of Neuroradiology

- ESR

European Society of Radiology

- EUSOMII

European Society of Medical Imaging Informatics

- RSNA

Radiological Society of North America

- SARS-CoV-2

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- WA

Weighted average

- WHO

World Health Organization

Funding

The authors state that this work has not received any funding.

Declarations

Guarantor

The scientific guarantor of this publication is Gennaro D’Anna.

Conflict of interest

The authors of this manuscript declare no relationships with any companies, whose products or services may be related to the subject matter of the article.

D’Anna G: Chair, Social Media Committee, European Society of Neuroradiology.

Ugga L: Nothing to disclose.

Cuocolo R: Member of the European Radiology Editorial Board.

Chen MM: American Society of Neuroradiology RUC Primary Advisor.

Shatzkes DR: American Society of Head and Neck Radiology Past President.

Tali ET: World Federation of Neuroradiological Societies President.

Patel A: Associated Editor Journal of American College of Radiology.

Kotsenas AL: Vice Speaker, American College of Radiology.

Van Goethem J: European Society of Neuroradiology Past President.

Garg T: Nothing to disclose.

Hirsch JA: American Society of Neuroradiology Past President.

Martì-Bonmatì L: Editor in Chief Insights into Imaging.

Gaillard F: radiopaedia.org Founder

Ranschaert E: European Society of Medical Imaging Informatics Past President.

Statistics and biometry

One of the authors has significant statistical expertise.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants in this study, by agreeing to participate in the survey.

Ethical approval

Institutional Review Board approval was not required because the study was a voluntary survey among radiology professionals not concerning any health information and all data was handled anonymously. Participants were informed that the results collected would be handled anonymously and may be used for scientific publication.

Study subjects or cohorts overlap

Preliminary results have been presented as educational exhibit at 2020 EUSOMII Annual Meeting.

Methodology

• survey

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(2020) WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020. https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19%2D%2D-11-march-2020

- 3.Mahajan A, Hirsch JA (2020) Novel coronavirus: what neuroradiologists as citizens of the world need to know. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 41:552–554. 10.3174/ajnr.A6526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Rubinger L, Gazendam A, Ekhtiari S, et al. Maximizing virtual meetings and conferences: a review of best practices. Int Orthop. 2020;44:1461–1466. doi: 10.1007/s00264-020-04615-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Porpiglia F, Checcucci E, Autorino R, et al. Traditional and virtual congress meetings during the COVID-19 pandemic and the post-COVID-19 era: is it time to change the paradigm? Eur Urol. 2020;78:301–303. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D’Anna G, D’Arco F, Van Goethem J. Virtual meetings: a temporary choice or an effective opportunity for the future? Neuroradiology. 2020;62:769–770. doi: 10.1007/s00234-020-02461-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.González-Ortiz S, Medrano S, Maiques JM, Capellades J (2020) Challenges in Neuroimaging in COVID-19 Pandemia. Front Neurol 11. 10.3389/fneur.2020.579079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Antonoff MB, Mitzman B, Backhus L, et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) virtual conference taskforce: recommendations for hosting a virtual surgical meeting. Ann Thorac Surg. 2021;111:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2020.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Viglione G. A year without conferences? How the coronavirus pandemic could change research. Nature. 2020;579:327–328. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-00786-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laniado M. Radiological congresses and the corona pandemic - the future and beyond. Radiologia. 2021;63:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.rx.2020.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hameed BZ, Tanidir Y, Naik N, et al. Will “hybrid” meetings replace face-to-face meetings post COVID-19 era? Perceptions and Views From The Urological Community. Urology. 2021;156:52–57. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2021.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanaei S, Takian A, Majdzadeh R et al (2020) Emerging standards and the hybrid model for organizing scientific events during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 1–6. 10.1017/dmp.2020.406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Rissman L, Jacobs C (2020) Responding to the climate crisis: the importance of virtual conferencing post-pandemic. Collabra Psychol 6. 10.1525/collabra.17966

- 14.Douglas Phillips C RSNA 2021: are we back? https://opmed.doximity.com/articles/rsna-2021-are-we-back?_csrf_attempted=yes

- 15.Clarke CGD, Nnajiuba U, Howie J, et al. Giving radiologists a voice: a review of podcasts in radiology. Insights Imaging. 2020;11:33. doi: 10.1186/s13244-020-0842-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.(2021) EuSoMII Virtual Annual Meeting 2020 Book of Abstracts. Insights Imaging 12:39. 10.1186/s13244-021-00975-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Coronavirus reveals need to bridge the digital divide. https://unctad.org/news/coronavirus-reveals-need-bridge-digital-divide

- 18.Netflix to cut streaming quality in Europe for 30 days. https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-51968302

- 19.RSNA 2021 updates and announcements

- 20.McGinty Focuses on ACR’s Strategic Vision at RBMA. https://www.acr.org/Advocacy-and-Economics/Advocacy-News/Advocacy-News-Issues/In-the-April-14-2018-Issue/McGinty-Focuses-on-ACR-Strategic-Vision-at-RBMA

- 21.D’Anna G, Chen MM, McCarty JL et al (2019) The continued rise in professional use of social media at scientific meetings: an analysis of twitter use during the ASNR 2018 annual meeting. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 40:935–937. 10.3174/ajnr.A6064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.D’Anna G, Pyatigorskaya N, Appelman A, et al. Exploring new landmarks: analysis of Twitter usage during the 41st ESNR Annual Meeting. Neuroradiology. 2019;61:621–626. doi: 10.1007/s00234-019-02193-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Radmanesh A, Kotsenas AL (2016) Social media and scientific meetings: an analysis of Twitter use at the annual meeting of the American Society of Neuroradiology. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 37:25–27. 10.3174/ajnr.A4168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.CES official website. https://www.ces.tech

- 25.Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2603–2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 54 kb)

(XLSX 22 kb)