Abstract

Background

Self-efficacy is decisive for the quality of life of elderly, multimorbid persons. It may be possible to strengthen patients’ self-efficacy can be strengthened by the targeted reinforcement of individual spirituality, social activity, and self-care. This hypothesis was tested with the aid of a complex intervention.

Methods

A non-blinded, exploratory, cluster-randomized, controlled trial was carried out, with primary care practices as the randomization unit (registration number DRKS00015696). The patients included were at least 70 years of age, had at least three chronic diseases, were taking at least three medications, and were participating in a disease management program. In the intervention group, primary care physicians took a spiritual history, and medical assistants advised the patients on the use of home remedies (e.g., tea, application of heat/cold) and on regionally available programs for the elderly. The primary endpoint—health-related self-efficacy, measured using the SES6G scale—and further, secondary endpoints were evaluated with multistep regression analyses.

Results

Data from 297 patients treated in 24 primary care practices were evaluated. The analysis of the primary endpoint indicated no effect (mean difference between study arms 0.30 points, 95% confidence interval [-0.21; 0.81], d = 0.14, p = 0.25). Subgroup analysis revealed the following situation for the secondary endpoint “mental well-being” (SF-12 subscale): patients who had already been using home remedies before the trial began experienced a marked improvement (a difference of 7.3 points on a scale from 0 to 100; d = 0.77, p < 0.001). This was also the case for patients who stated that spirituality played a major role in their lives (a difference of 6.2 points on a scale from 0 to 100; d = 0.65; p = 0.002).

Conclusion

The main hypothesis concerning health-related self-efficacy was not confirmed. The results of the analysis of secondary parameters indicate that some subgroups of patients can benefit from the interventional approach.

About one third of the European population suffer from chronic conditions requiring treatment with multiple medications (1). Disease Management Programs (DMP) offer chronically ill patients structured assessments every 3–6 months (2). While DMP are mainly intended to standardize diagnostic procedures and treatment, the integration of holistic aspects of healthcare, such as spirituality, social activity, and self-care, could strengthen patients’ self-efficacy and thus contribute to more patient empowerment.

Self-efficacy, i.e., the subjectively perceived ability to achieve self-defined goals, has been demonstrated to be a decisive factor for elderly patients’ quality of life (3).

Spirituality has been linked to self-efficacy (4). The definitions of spirituality and spiritual needs are heterogeneous but often have four attributes in common (5, 6):

Connectedness (e.g., feeling connected to family)

Transcendence (e.g., immersion in nature, praying)

Peace (e.g., finding inner peace, relaxing in a peaceful place)

Meaning in life (e.g., passing on life experience, being sure that one’s own life is meaningful)

In the context of this study, we defined spirituality as anything that lends meaning to a person’s life and serves as a personal resource. This definition was also chosen to emphasize that spirituality encompasses more than religion.

Self-care, defined in this study as activities—aside from taking medication—that patients can accomplish on their own to increase their personal well-being, and social activity are reciprocally related to self-efficacy (7– 9) and spirituality (4, 10).

The overall aim of the “Holistic Care Program for Elderly Patients to Integrate Spiritual Needs, Social Activity and Self-Care into Disease Management in Primary Care (HoPES3)” was to strengthen these aspects in primary care. It was assumed that interventions designed to increase patients’ awareness of their personal and spiritual resources and encourage social activities and self-care would strengthen self-efficacy and in the long run improve the quality of life. Self-efficacy was therefore defined as the primary outcome. The rationale for these assumptions is described in detail in the study protocol which also contains a theoretical model of the assumed effect mechanisms of the intervention (11).

The objective of this study was to assess the effectiveness of the HoPES3 intervention at the patient level in terms of primary and secondary outcomes.

Methods

Trial design

Between March 2019 and June 2020, a cluster-randomized controlled trial was conducted with primary care physicians’ offices as unit of randomization and follow-up of 6 months. Owing to the lack of previous experience regarding possible intervention effects, the study was conceived as an exploratory pilot study. The study was reviewed by the responsible ethics committees of the University Hospital Heidelberg and the Baden-Württemberg Medical Association, registered with the German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS 00015696), and funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (funding code 01GL1803).

Recruitment

All general practices in defined regions of southern Baden-Württemberg were contacted by post. Primary care physicians (PCP) who offered at least one DMP and the medical assistants of these PCP were eligible (a task description of medical assistants in Germany can be found in [12]). The participating PCP informed all patients who met the inclusion criteria and were scheduled for DMP appointments within the next 3 months about the study. The inclusion criteria were as follows:

Age ≥ 70 years

At least three chronic conditions

Taking at least three medications

Participating in at least one DMP

Capable of active participation in the study

Moreover, the PCP were requested predominantly to include patients who, in their estimation, would benefit from the intervention.

Data collection

The data on measurement of outcomes were collected using questionnaires that were completed at the time of enrolment (T0) and 6 months after the intervention (T1). Furthermore, at T0, the medication plans were acquired from the office’s administration system.

Interventions

While in the control group the DMP was conducted as before, patients in the intervention group additionally received the HoPES3 intervention, which focused on three domains:

Spiritual needs

Self-care by means of home remedies

Social activity and loneliness

A spiritual history was taken by the PCP according to the conversational model SPIR: The four key questions (Box and https://www.aerzteblatt.de/down.asp?id=29943 which can be supplemented or replaced by subquestions in order to adapt the language to the individual patient, allow structured acquisition of important information about the patients’ spirituality, including their desire for more social contacts and self-care measures (13).

Box. Key questions of the conversational model SPIR with exemplary sub-questions (13).

-

S (Spirituality)

Would you describe yourself—in the broadest sense of the term—as a believing/spiritual/religious person?

From what do you draw strength?

-

P (Place of spirituality in your life)

What is the place of spirituality in your life? How important is it in the context of your illness?

How do these convictions influence the degree to which you care for yourself and for your health?

-

I (Integration)

Are you integrated in a spiritual community?

Is there a person or a group of people who really mean a lot to you and who are important to you?

Would you like to have more companionship?

-

R (Role)

What role would you like to assign to your doctor in the domain of spirituality?

What role should these beliefs play in your medical treatment?

(Reproduced by kind permission of Prof. Dr. med. Eckhard Frick)

Next, the medical assistants provided information about regional social activities for seniors and/or home remedies, i.e. non-pharmacological interventions that patients can accomplish on their own to relieve symptoms that frequently occur in old age (e.g., heat/cold treatments and herbal applications). For this purpose, PCP offices and patients received information leaflets on home remedies https://www.aerzteblatt.de/down.asp?id=29944 and a web-based list of social activities for seniors within a radius of 10 km of the respective office. All materials had been elaborated by the study team and were available via the study’s website (www.hopes3.de). Patients were asked to document their spiritual, social, and self-care activities in a standardized diary. The PCP and medical assistants were trained by the study team in a 4-hour workshop. A more detailed description of the intervention can be found in other publications (11, 14).

Outcomes and instruments

Health-related self-efficacy was defined as primary outcome and measured on the Self-Efficacy for Managing Chronic Disease 6-Item Scale (SES6G) (15). In accordance with to the exploratory character of the trial, a range of secondary patient outcomes (n = 8) were measured with validated questionnaires (Table 2, eTable 1). Additionally, non-validated items were used to assess patients’ awareness of their sources of strength (two items) and the use of home remedies (one item) (etable 1).

Table 2. Baseline characteristics of the study participants.

| Intervention | Control | Total | |

| Patients | n = 164 | n = 133 | n = 297 |

| Mean age in years (range, SD) | 78.29 (70–91; 4.69) | 78.68 (70–91; 4.85) | 78.46 (70–91; 4.76) |

| Female n (%) | 87 (53.0) | 76 (57.1) | 163 (54.9) |

| Living alone n (%) | 50 (32.1) | 40 (30.5) | 90 (31.4) |

| Level of education n (%) – General or intermediate secondary school – University preparatory high school – University degree |

133 (85.3) 7 (4.5) 16 (10.3) |

111 (84.8) 6 (4.6) 10 (7.6) |

244 (85.1) 13 (4.5) 26 (9.1) |

| Mean number of medications (range, SD) | 7.70 (3–20; 3.23) | 7.57 (3–16; 2.68) | 7.64 (3–20; 2.99) |

| Religion n (%) – Christian – Other – No religion |

136 (87.2) 8 (5.1) 12 (7.7) |

112 (86.1) 3 (2.3) 15 (11.5) |

248 (86.7) 11 (3.8) 27 (9.4) |

| Patients stating that spirituality or religious beliefs are generally (very) important in their life*1 n (%) | 58 (36.0) | 42 (32.3) | 100 (34.4) |

| Patients stating use of home remedies 6 months prior to the trial*2 n (%) | 54 (33.3) | 51 (39.2) | 105 (36.0) |

| Lonely patients according to DJGS-6*3 n (%) | 18 (11.1) | 14 (10.9) | 32 (11.0) |

| Patients with a small social network according to LSNS*4 n (%) | 25 (15.9) | 23 (18.5) | 48 (17.1) |

| Patients who were taking at least one psychotropic drug according to their medication plan*5 n (%) | 24 (14.6) | 16 (12.0) | 40 (13.5) |

| Primary care physicians | n = 13 | n = 14 | n = 27 |

| Mean age in years (range, SD) | 52.46 (36–64; 7.72) | 52.00 (43–62; 5.71) | 52.22 (36–64; 6.62) |

| Female n (%) | 6 (46.2) | 5 (35.7) | 11 (40.7) |

| Mean work experience in years (range, SD) | 23.23 (4–40; 9.57) | 21.57 (7–35; 7.75) | 22.37 (4–40; 8.54) |

| Further training in complementary medicine n (%) | 7 (53.8) | 8 (57.1) | 15 (55.6) |

| Single-handed office n (%) | 4 (30.8) | 10 (71.4) | 14 (51.9) |

| Religion n (%) – Christian – No religion |

7 (53.9) 6 (46.2) |

12 (85.7) 2 (14.3) |

19 (70.4) 8 (29.6) |

| Primary care physicians stating that spirituality or religious beliefs are generally (very) important in their life*1 n (%) | 9 (64.3) | 5 (38.5) | 14 (51.8) |

| Medical assistants | n = 17 | n = 17 | n = 34 |

| Mean age in years (range, SD) | 44.12 (20–55; 10.17) | 44.88 (21–56; 9.88) | 44.50 (20–56; 9.88) |

| Female n (%) | 17 (100.0) | 17 (100.0) | 34 (100.0) |

| Mean work experience in years (range, SD) | 18.76 (1–35; 10.60) | 18.29 (1–37; 11.09) | 18.53 (1–37; 10.69) |

| Single-handed office n (%) | 10 (58.8) | 12 (70.6) | 22 (64.7) |

| Religious affiliation n (%) – Christian – Muslim – No religion |

12 (70.6) 1 (5.9) 3 (17.6) |

11 (64.7) 1 (5.9) 4 (23.5) |

23 (67.6) 2 (5.9) 7 (20.6) |

| Medical assistants stating that spirituality or religious beliefs are generally (very) important in their life*1 n (%) | 6 (35.3) | 10 (53.8) | 16 (47.1) |

*1 In general, how important are spiritual or religious beliefs in your life? (four response options: very important, important, somewhat, not at all)

*2 Have you used home remedies within the past 6 months? (response options: yes or no)

*3 DJGS-6 = De-Jong–Gierveld Loneliness Scale (six-item short version with four response options, score > 2.5 indicates loneliness) (16).

*4 LSNS-6 = Lubben Social Network Scale (six-item version, sum score ranging from 0 to 30, sum score < 12 indicates risk of social isolation) (23).

*5 Psychotropic drugs: all substances classified as psychoanaleptics (N06) and psycholeptics (N05) in the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) Classification System (29).

n, Number; SD, standard deviation

eTable 1. Intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis for primary and secondary endpoints (supplementing Table 1).

| Outcome | Group | T0 | T1 | EST [95% CI] | d | p | ||||

| n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | |||||

|

LSNS-6 (social isolation) |

IG | 157 | 17.10 | 5.43 | 111 | 17.23 | 5.93 | 0.02 [−1.11; 1.16] | 0.00 | 0.97 |

| CG | 124 | 16.68 | 5.56 | 120 | 16.29 | 6.00 | ||||

| DJGS-6 (loneliness) | IG | 162 | 1.79 | 0.58 | 109 | 1.76 | 0.57 | 0.01 [−0.09; 0.12] | 0.02 | 0.81 |

| CG | 128 | 1.75 | 0.65 | 121 | 1.78 | 0.64 | ||||

|

GSES (general self-efficacy) |

IG | 158 | 30.99 | 5.17 | 105 | 31.14 | 0.16 [−0.89; 1.21] | 0.03 | 0.81 | |

| CG | 120 | 31.39 | 5.24 | 114 | 31.51 | 5.24 | ||||

|

PAM (patient activation) |

IG | 155 | 43.04 | 5.77 | 104 | 43.90 | 5.18 | 0.87 [−0.35; 2.08] | 0.15 | 0.16 |

| CG | 126 | 42.97 | 6.19 | 118 | 42.94 | 6.08 | ||||

|

EUROPEP (overall satisfaction with primary care) |

IG | 163 | 3.55 | 0.60 | 114 | 3.50 | 0.63 | −0.03 [−0.22; 0.16] | -0.04 | 0.75 |

| CG | 131 | 3.39 | 0.76 | 123 | 3.41 | 0.74 | ||||

|

MARS (treatment adherence) |

IG | 162 | 23.52 | 1.73 | 112 | 23.53 | 1.79 | 0.08 [−0.28; 0.44] | 0.04 | 0.65 |

| CG | 130 | 23.72 | 1.61 | 124 | 23.57 | 1.91 | ||||

|

BMQ (general overuse of medication) |

IG | 159 | 12.01 | 2.27 | 110 | 11.99 | 2.58 | 0.22 [−0.37; 0.82] | 0.08 | 0.46 |

| CG | 129 | 12.43 | 2.39 | 123 | 11.93 | 2.86 | ||||

|

BMQ (harmfulness of medication) |

IG | 156 | 9.38 | 2.39 | 112 | 9.40 | 2.57 | 0.33 [−0.21; 0.87] | 0.13 | 0.23 |

| CG | 127 | 9.29 | 2.39 | 124 | 9.16 | 2.65 | ||||

|

BMQ (benefit of medication) |

IG | 161 | 15.86 | 2.10 | 111 | 15.77 | 2.12 | 0.09 [−0.40; 0.58] | 0.04 | 0.72 |

| CG | 130 | 15.69 | 2.28 | 123 | 15.41 | 2.18 | ||||

| n | % | n | % | OR | p (MWU) | |||||

|

Awareness of spiritual resources (I know what I can draw strength and energy from – Not true at all – Rather not true – Partly true – True |

IG | 161 | 5 32 67 57 |

3.1 19.9 41.6 35.4 |

112 | 3 14 54 41 |

2.7 12.5 48.2 36.6 |

– | 0.36 | |

| CG | 131 | 15 20 54 42 |

11.5 15.3 41.2 32.1 |

123 | 16 19 47 41 |

13.0 15.4 38.2 33.3 |

||||

|

Awareness of spiritual resources (I regular take time to make use of my sources of strength) – Not true at all – Rather not true – Partly true – True |

IG | 160 | 6 46 62 46 |

3.8 28.8 38.8 28.8 |

114 | 6 18 48 42 |

5.3 15.8 42.1 36.8 |

– | 0.21 | |

| CG | 131 | 17 30 53 31 |

13.0 22.9 40.5 23.7 |

123 | 16 27 44 36 |

13.0 22.0 35.8 29.3 |

||||

|

Use of home remedies in the previous 6 months – Yes – No |

IG | 162 | 54 108 |

33.3 66.7 |

114 | 53 61 |

46.5 53.5 |

1.68 [0.84; 3.33] | 0.14 | |

| CG | 130 | 51 79 |

39.2 60.8 |

125 | 44 81 |

35.2 64.8 |

||||

EST = Mean difference between treatment groups at T1, adjusted for age, gender, number of medications, baseline value of respective endpoint, and PCP office.

OR = Odds ratio between treatment groups at T1, adjusted for age, gender, number of medications, baseline value of home remedy use, and PCP office.

d = Cohen’s d/effect size of mean differences, interpreted as follows: < 0.2 = no effect, ≥ 0.2 = weak, ≥ 0.5 = moderate, ≥ 0.8 = strong.

p = p-value, expressing whether, according to a hypothesis test, EST = 0.

CG, Control group; CI, confidence interval; IG, intervention group; MWU, Mann–Whitney U test; n, number; SD, standard deviation

LSNS-6 = Lubben Social Network Scale (six-item version, sum score ranging from 0 to 30, sum score below 12 indicates a small social network) (23).

DJGS-6 = De-Jong-Gierveld Loneliness Scale (six-item short version with a 4-point response option, values > 2.5 indicate loneliness) (16).

GSES = General Self-Efficacy Scale (sum score of 10 items, scale from 10 to 40, higher scores indicate higher level of self-efficacy) (24).

PAM = Patient Activation Measure (sum score of 13 items, total score between 13 and 52, higher scores indicate higher level of activation) (25).

EUROPEP = Selected items of the European Project on Patient Evaluation of General Practice Care questionnaire. Mean of items 8 and 9, score range from 1 to 5, higher scores indicate greater satisfaction with PCP care (28).

MARS = Medication Adherence Report Scale (sum of all five items,scores between 5 and 25, higher scores are indicative of better treatment adherence) (26).

BMQ General = first part of the Beliefs About Medicines Questionnaire, which addresses general opinions about drugs on three scales (sum scores from 4 to 20, higher scores indicate stronger beliefs) (27).

Statistical methods

The primary efficacy analysis was carried out via a mixed linear model, with the SES6G score at T1 as a dependent variable as well as the fixed factors treatment group, gender, SES6G score at T0, age, and number of drugs and the random factor PCP office. The primary analysis was conducted according to the intention to treat (ITT) principle. Secondary endpoints were evaluated analogously to the primary endpoint. A detailed description of the statistical methods can be found in the eMethods.

Results

Inclusion and exclusion of participants

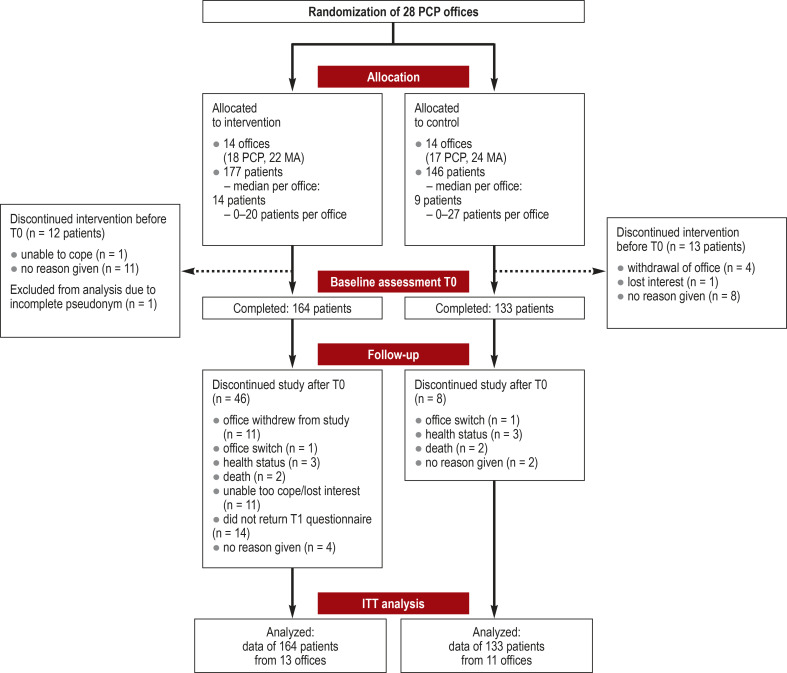

The Figure shows the study participants’ inclusion and exclusion. Data from 24 PCP offices (13 intervention group, 11 control group) and 297 patients (164 intervention group, 133 control group) were analyzed.

Figure.

Flow chart showing inclusion and exclusion of study participants; ITT, intention to treat; MA,medical assistant; PCP, primary care physician

Recruitment

The PCP offices were recruited between March and May 2019. Baseline assessments were completed within 4 weeks prior to the workshops for office teams (on 29 June 2019 and 3 July 2019) which marked the beginning of the intervention phase. Since the targeted patient sample size had not been reached, enrolment continued till September 2019. Therefore, allocation concealment could not be maintained for patients recruited after the workshop (n = 73, 24.6%). Six months after the HoPES3 intervention, between December 2019 and June 2020, patients completed the questionnaires for follow-up assessment.

Baseline data

Table 2 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants. The baseline characteristics of the two groups were broadly comparable.

Primary and secondary outcomes

Intention-to-treat analysis

As shown in Table 1, the intention-to-treat analysis, which included all 297 patients from 24 offices, detected no effect on the primary outcome (health-related self-efficacy measured on the SES6G scale). The intracluster correlation coefficient for the primary outcome was 0.0479, indicating a small but not inconsiderable degree of similarity among the patients from a given office with regard to health-related self-efficacy.

Table 1. ITT analysis for primary and secondary outcomes.

| Outcome | Group | T0 | T1 | EST [95% CI] | d | p | ||||

| n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | |||||

| SES6G (primary outcome) | IG | 159 | 7.22 | 1.98 | 106 | 7.19 | 1.96 | 0.30 [−0.21; 0.81] | 0.14 | 0.25 |

| CG | 131 | 7.07 | 2.15 | 122 | 6.75 | 2.20 | ||||

| SF12 (physical well-being) | IG | 147 | 38.73 | 9.78 | 94 | 38.04 | 10.11 | −0.73 [−3.24; 1.78] | −0.08 | 0.57 |

| CG | 116 | 37.17 | 9.98 | 106 | 37.16 | 9.11 | ||||

| SF12 (mental well-being) | IG | 147 | 49.62 | 11.23 | 94 | 52.56 | 9.06 | 3.34 [0.99; 5.69] | 0.35 | 0.006 |

| CG | 116 | 49.90 | 9.16 | 106 | 48.74 | 9.85 | ||||

EST = Mean difference between treatment groups at T1, adjusted for age, gender, number of medications, baseline value of respective endpoint, and PCP office. d = Cohen’s d/effect size of mean differences, interpreted as follows: < 0.2 = no effect, ≥ 0.2 = weak, ≥ 0.5=moderate, ≥ 0.8 = strong. p = p-value, expressing whether, according to a hypothesis test, EST = 0.

SES6G = health related self-efficacy scale (mean of at least four of six items, scale from 1 to 10 with higher scores indicating higher self-efficacy) (15)

SF12 = Questionnaire on health status, consisting of the two subscales mental health and physical health, each ranging from 0 to 100 with higher scores indicating higher quality of life (17). The remaining secondary endpoints are presented in eTable 1

CG, Control group; CI, confidence interval; IG, intervention group; ITT, intention to treat; n, number; SD, standard deviation.

Among the 11 secondary endpoints, a marginal effect of the HoPES3 intervention could be observed on mental well-being as measured by a subscale of the SF12 questionnaire (17). The difference of 3.34 points on a scale of 0–100 corresponds to a weak effect (d = 0.35, p = 0.006). The data for the remaining secondary outcomes can be found in eTable 1.

Per-protocol and subgroup analyses

eTable 2 shows the detailed results of the subgroup analyses. Interesting observations were made especially with regard to mental well-being:

eTable 2. Per-protocol and subgroup analyses.

| Outcome | Subgroup |

n

(IG/CG) |

ITT

(IG = 164; CG = 133) |

n

(IG/CG) |

PP

(IG = 121; CG = 133) |

n

(IG/CG) |

mPP

(IG = 107; CG = 133) |

||||||

| EST | d | p | EST | d | p | EST | d | p | |||||

|

SES6G (primary outcome) |

All | 164 133 |

0.30 | 0.14 | 0.25 | 92 122 |

0.44 | 0.21 | 0.11 | 83 122 |

0.48 | 0.23 | 0.10 |

| Spirituality – important | 41 38 |

0.54 | 0.26 | 0.20 | 38 38 |

0.58 | 0.28 | 0.17 | 35 38 |

0.56 | 0.27 | 0.20 | |

| Spirituality – not important | 64 82 |

0.12 | 0.05 | 0.73 | 53 82 |

0.28 | 0.13 | 0.41 | 47 82 |

0.34 | 0.16 | 0.33 | |

| Home remedies before trial – yes | 38 47 |

0.79 | 0.37 | 0.05 | 33 47 |

1.04 | 0.49 | 0.01 | 30 47 |

1.01 | 0.48 | 0.02 | |

| Home remedies before trial – no | 66 73 |

−0.01 | −0.00 | 0.98 | 57 73 |

0.07 | 0.03 | 0.83 | 51 73 |

0.16 | 0.08 | 0.65 | |

| Small social network (LSNS) | 15 23 |

−0.30 | −0.14 | 0.61 | 12 23 |

0.13 | 0.06 | 0.72 | 8 23 |

0.28 | 0.13 | 0.69 | |

| Large social network (LSNS) | 86 91 |

0.49 | 0.23 | 0.10 | 75 91 |

0.49 | 0.28 | 0.10 | 71 91 |

0.58 | 0.28 | 0.07 | |

| DJG-6 – lonely | 11 14 |

0.05 | 0.02 | 0.94 | 10 14 |

0.27 | 0.13 | 0.72 | 7 14 |

0.72 | 0.34 | 0.38 | |

| DJG-6 – not lonely | 93 103 |

0.35 | 0.16 | 0.22 | 80 103 |

0.49 | 0.23 | 0.10 | 74 103 |

0.48 | 0.23 | 0.12 | |

|

SF12 – mental well-being |

All | 94 106 |

3.34 | 0.35 | 0.006 | 83 106 |

3.36 | 0.35 | 0.007 | 77 106 |

4.17 | 0.44 | 0.002 |

| Home remedies before trial – yes | 34 37 |

7.34 | 0.77 | < 0.001 | 30 37 |

7.15 | 0.75 | < 0.001 | 29 37 |

7.73 | 0.81 | < 0.001 | |

| Home remedies before trial – no | 59 67 |

1.11 | 0.12 | 0.45 | 52 67 |

1.26 | 0.13 | 0.40 | 47 67 |

2.20 | 0.23 | 0.17 | |

| Spirituality – important | 36 33 |

6.23 | 0.65 | 0.002 | 33 33 |

5.92 | 0.62 | 0.004 | 33 33 |

5.89 | 0.62 | 0.005 | |

| Spirituality – not important | 57 72 |

1.38 | 0.11 | 0.35 | 49 72 |

1.54 | 0.16 | 0.33 | 43 72 |

2.74 | 0.29 | 0.11 | |

| Small social network (LSNS) | 12 21 |

−0.58 | −0.06 | 0.85 | 10 21 |

−1.22 | −0.13 | 0.70 | 6 21 |

2.66 | 0.28 | 0.47 | |

| Large social network (LSNS) | 78 79 |

4.83 | 0.50 | 0.003 | 69 79 |

4.83 | 0.51 | 0.005 | 68 79 |

4.97 | 0.52 | 0.006 | |

| DJG-6 – lonely | 9 12 |

−1.11 | −0.12 | 0.77 | 9 12 |

−1.12 | −0.12 | 0.77 | 6 12 |

2.80 | 0.30 | 0.53 | |

| DJG-6 – not lonely | 84 90 |

3.78 | 0.39 | 0.003 | 73 90 |

3.85 | 0.40 | 0.004 | 70 90 |

4.21 | 0.44 | 0.004 | |

| Psychotropic drugs – yes | 11 11 |

−1.06 | −0.11 | 0.78 | 9 11 |

−1.02 | −0.11 | 0.79 | 8 11 |

0.27 | 0.03 | 0.94 | |

| Psychotropic drugs – no | 83 95 |

3.78 | 0.39 | 0.003 | 74 95 |

3.84 | 0.40 | 0.004 | 69 95 |

4.57 | 0.48 | 0.001 | |

EST = Mean difference between treatment groups at T1, adjusted for age, gender, number of medications, baseline value of respective endpoint, and office.

d = Cohen’s d/effect size of mean differences, interpreted as follows: < 0.2 = no effect, ≥ 0.2 = weak, ≥ 0.5 = moderate, ≥ 0.8 = strong,

p = p-value corresponding to a hypothesis test whether EST = 0.

ITT = Intention to treat (all patients meeting the inclusion criteria), PP = per protocol (all patients who stated they had undergone spiritual history taking), mPP = modified per protocol (all patients who stated they had undergone spiritual history taking and received information about home remedies and/or social activities).

SES6G = Health-Related Self-Efficacy Scale (mean over at least four of six items, score 1–10, higher scores indicate greater self-efficacy) (15).

SF12-mental well-being = subscale of the health status survey, score 0–100, higher scores indicate a higher level of mental well-being (17).

LSNS = Lubben Social Network Scale (six-item version, sum score 0–30, score below 12 indicates a small social network) (23).

DJG-6 = De-Jong–Gierveld Loneliness Scale (six-item short version with four response options, values > 2.5 indicate loneliness) (16).

Psychotropic drugs: all substances classed as psychoanaleptics (N06) and psycholeptics (N05) in the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) Classification System (29). CG, Control group; IG, intervention group

Patients who stated that they had already used home remedies before the trial (n = 71) showed a notable improvement (7.34 points difference). This almost corresponds to a strong effect (d = 0.77, p<0.001). The same was the case for patients who stated that spirituality mattered a lot in their lives (n = 69). Here, the SF12 subscale improved by 6.2 points which indicates a moderate effect (d = 0.65, p = 0.002).

Patients with a large social network (n = 157) showed a stronger improvement regarding mental well-being (4.83-point difference indicating a moderate effect, d = 0.50, p = 0.003) than patients with a small social network (-0.58-point difference indicating no effect). Similarly, patients who did not feel lonely (n = 175) showed more improvement (3.78-point difference indicating a weak effect, d = 0.39, p = 0.003) than lonely patients (-1.11-point difference indicating no effect).

Further, weak effects were found in patients not taking any psychotropic drugs (3.78-point difference, d = 0.39, p = 0.003), but no effects could be detected in those with psychotropic drugs prescribed (n = 22).

Another interesting observation concerned the comparison between the predefined patient populations (eMethods): considering all patients, effects on mental well-being tended to be stronger if patients had participated in both spiritual history taking and advice on home remedies and/or social activities (EST 3.36 versus 4.17). This was also the case for the subgroup of home remedy users (EST 7.15 versus 7.73).

Harmful effects

Patients were asked to complete a questionnaire within 2 weeks after the HoPES3 intervention. Only 2.5% (n = 3) of the patients stated that the conversation had been (very) stressful for them.

Discussion

This study evaluated the effectiveness of a complex intervention to strengthen self-efficacy and thereby improve elderly multimorbid patients’ quality of life. While no relevant effect on the primary outcome was detected, the analyses of the secondary outcomes and the subgroup analyses led to some interesting observations concerning mental well-being:

Strong effects on mental well-being were found in patients who had already used home remedies prior to study participation. This is in line with the findings of Puig Llobet et al., who observed a positive association between self-care ability and mental health (18). An explanation could be that—independent of possible specific therapeutic effects of the home remedies—patients felt empowered to have confidence in their own coping strategies. It is possible that the patients perceived the proactive recommendations on home remedies and the office teams’ deep interest in their personal sources of strength as an expression of respect and assurance towards their pre-existing self-care abilities.

The complex intervention led to a notable improvement on the mental well-being scale in patients who had stated that spiritual or religious beliefs greatly mattered in their lives. A positive correlation between spiritual/religious coping and mental well-being has been described in previous studies (4). The accompanying process evaluation (19, 20) showed that spiritual patients were more open to the spiritual history taking, while less spiritual patients were more reluctant—mainly because they associated spirituality with church or religion in a negative way. This may explain the lack of effects in this patient group.

No improvement of mental well-being was noted in the subgroup of psychotropic drug users. Possible explanations could be that those patients were seriously ill and therefore required a more intensive intervention, or that they were less open to non-pharmacological alternatives.

Similarly, no effects on mental well-being were found in lonely patients or in patients with a small social network. This observation may be due to the low proportion of less than 10% of lonely, isolated patients in the study population, so that the statistical power was not sufficient to detect weaker effects. This suggests that more active, well integrated patients took part in the study, as also shown by the process evaluation (20). Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic restricted social activities. Another explanation is that the strategies used to increase social contacts were not sufficient to activate lonely, isolated patients. Achieving that would probably require a more intensive case management program, including home visits and educational measures targeting behavioral change (21). In addition, other studies indicate that spiritual/religious coping correlates positively with mental well-being only if social support and self-efficacy are present (4).

Interestingly, the effects tended to be stronger in patients whose PCP had taken a spiritual history and who had received information about home remedies and/or social activities, provided mainly by the medical assistants. This finding supports our experiences from previous studies with regard to the involvement of medical assistants in the care of chronically ill patients. Patients frequently approach medical assistants with questions they could not bring themselves to ask their PCP (22). Programs to improve the care of chronically ill patients should take advantage of this potential.

Limitations

The main limitation of the study is the limited representativeness of the samples. It is likely that mainly PCP with a special interest in complementary and holistic medicine participated in the study. Moreover, it is likely that selection bias occurred in favor of active, committed patients. Furthermore, the exploratory character of the trial does not permit any confirmatory conclusions regarding the effectiveness of the complex intervention.

Conclusion

The primary hypothesis of the trial concerning patients’ health-related self-efficacy could not be confirmed. Nevertheless, some interesting observations suggest that a proactive conversation about patients’ spirituality combined with proactive information on home remedies and regional social activities could usefully complement the DMP for certain patient groups. Medical assistants may have an important role in delivering these interventions.

It seems that patients with stronger spiritual convictions and a preference towards non-pharmacological treatment options such as home remedies may benefit from low-threshold interventions. In contrast, patients who are less active, less integrated, and less aware of their personal and spiritual resources may need a more intensive intervention or a different style of intervention.

The strongest effects in these subgroups were observed on mental well-being. This finding may be of interest regarding the new DMP for depression, which was developed after the beginning of this trial. Although no recommendations for daily practice can be derived, our results provide valuable information for future confirmatory trials.

Supplementary Material

eMethods

Statistical methods

Sample size

According to the sample size calculation (11), 22 offices and 264 patients were required to detect a clinically relevant mean difference of 1 point on the SES6G scale (15) at a two-sided α of 0.05 with a power of 1 - ß = 0.8, assuming a standard deviation of σ = 2.2, an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.05, and a cluster size of m = 12. Anticipating dropout rates of 7.5% at office and 20% at patient level, n = 24 offices with n = 360 patients were recruited.

Randomization

Using sealed envelopes, block randomization of offices with a block length of 4, stratified by region, was conducted for 1:1 assignment to either intervention or control group. Allocation remained concealed from offices, patients, and the study nurse who had conducted the office visits until completion of the baseline assessment, with the exception of those patients recruited after the workshop had taken place. Blinding was not possible due to the nature of the intervention.

Statistical analysis

The primary efficacy analysis was performed by fitting a linear mixed model including the SES6G score at T1 as dependent variable; treatment group, gender, SES6G score at T0, age, and number of medications as fixed factors; and office as a random factor. The fixed factors gender, age, number of medications, and SES6G score at T0 were included in the primary analysis model due to their assumed association with the primary outcome. Adjustment for these factors was performed in order to improve the efficiency of the model and to enable adjustment for these factors in the event of imbalances between the two treatment arms.

The primary analysis was conducted adhering to the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle, i.e., all patients and offices that fulfilling the inclusion criteria were included, even if they refused or discontinued the intervention or other protocol deviations occurred.

As sensitivity analyses, a per-protocol (PP) analysis and a modified per-protocol (mPP) analysis were carried out. The PP population consisted of all ITT patients with the exception of those patients from the intervention group who stated in the questionnaire that they had not undergone spiritual history taking. The mPP population comprised all patients of the PP population who stated they had undergone spiritual history taking and additionally another element of the HoPES3 intervention (information about home remedies and/or social activities) and the patients of the control group.

Missing data for the primary outcome were replaced in the primary analysis by means of multiple imputation.

The secondary endpoints were assessed analogously to the primary endpoint.

Subgroup analyses for the primary and secondary endpoints were conducted by including further interaction terms into the respective model. In total, five subgroup pairs were defined according to baseline data as outlined in the legend of Table 2:

Since this is an exploratory trial, the resulting p-values are not confirmatory and should be interpreted descriptively only.

All statistical procedures including allocation of the patients to the ITT, PP, and mPP populations are described in the study’s statistical analysis plan, which was finalized before database lock (except for subgroups 2, 3, and 5), and can be requested from the authors. Analyses were performed with SAS version 9.4.

Deviations from the study protocol

Due to an error in wording, we could not, as planned, analyze the long version of the De-Jong-Gierveld loneliness scale (DJGS-11); instead, we used the short version (DJGS-6) (16).

Spiritual versus non-spiritual patients

Lonely versus non-lonely patients

Patients with a large versus small social network

Home remedy users versus non-home remedy users

Patients with versus without prescription of psychotropic drugs

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

Data sharing

Due to the stipulations of the data protection law we are not able to make the entire data set publicly accessible. Selected data can be made available to individual researchers on reasonable request. The study protocol has already been published and the statistical analysis plan can be requested from the authors.

Funding

The study was supported by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research.

References

- 1.Midão L, Giardini A, Menditto E, Kardas P, Costa E. Polypharmacy prevalence among older adults based on the survey of health, ageing and retirement in Europe. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2018;78:213–220. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2018.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Linder R, Horenkamp-Sonntag D, Bestmann B, Battmer U, Heilmann T, Verheyen F. Disease management programs: difficulties in the analysis of benefit. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2015;58:345–351. doi: 10.1007/s00103-015-2136-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halisch F, Geppert U. Well-being in old age: the influence of self-efficacy, control beliefs, coping strategies, and personal goals Results from the Munich gold study. http://psydok.psycharchives.de/jspui/handle/20.500.11780/1955 (last accessed on 11 August 2021) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fatima S, Sharif S, Khalid I. How does religiosity enhance psychological well-being? Roles of self-efficacy and perceived social support. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. 2018;10:119–127. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weathers E, McCarthy G, Coffey A. Concept analysis of spirituality: an evolutionary approach. Nurs Forum. 2016;51:79–96. doi: 10.1111/nuf.12128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Büssing A. Büssing A, editor. Application and implementation of the spiritual needs questionnaire in spiritual care processes Spiritual needs in research and practice the spiritual needs questionnaire as a global resource for health and social care. Cham: Springer International Publishing. 2021:79–86. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fry PS, Debats DL. Self-efficacy beliefs as predictors of loneliness and psychological distress in older adults. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2002;55:233–269. doi: 10.2190/KBVP-L2TE-2ERY-BH26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eller LS, Lev EL, Yuan C, Watkins AV. Describing self-care self-efficacy: definition, measurement, outcomes, and implications. Int J Nurs Knowl. 2018;29:38–48. doi: 10.1111/2047-3095.12143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tharek Z, Ramli AS, Whitford DL, Ismail Z, Mohd Zulkifli M, Ahmad Sharoni SK, et al. Relationship between self-efficacy, self-care behaviour and glycaemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in the Malaysian primary care setting. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19 doi: 10.1186/s12875-018-0725-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bishop FL, Yardley L, Lewith GT. A systematic review of beliefs involved in the use of complementary and alternative medicine. J Health Psychol. 2007;12:851–867. doi: 10.1177/1359105307082447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Straßner C, Frick E, Stotz-Ingenlath G, Buhlinger-Gopfarth N, Szecsenyi J, Krisam J, et al. Holistic care program for elderly patients to integrate spiritual needs, social activity, and self-care into disease management in primary care (HoPES3): study protocol for a cluster-randomized trial. Trials. 2019;20 doi: 10.1186/s13063-019-3435-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freund T, Everett C, Griffiths P, Hudon C, Naccarella L, Laurant M. Skill mix, roles and remuneration in the primary care workforce: who are the healthcare professionals in the primary care teams across the world? Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52:727–743. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frick E, Riedner C, Fegg MJ, Hauf S, Borasio GD. A clinical interview assessing cancer patients’ spiritual needs and preferences. Eur J Cancer Care. 2006;15:238–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2005.00646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kunsmann-Leutiger E, Straßner C, Schalhorn F, Stolz R, Stotz-Ingenlath G, Buhlinger-Gopfarth N, et al. Training general practitioners and medical assistants within the framework of HoPES3, a holistic care program for elderly patients to integrate spiritual needs, social activity, and self-care into disease management in primary care. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2021;14:1853–1861. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S312778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freund T, Gensichen J, Goetz K, Szecsenyi J, Mahler C. Evaluating self-efficacy for managing chronic disease: psychometric properties of the six-item Self-Efficacy Scale in Germany. J Eval Clin Pract. 2013;19:39–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2011.01764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Jong Gierveld J, Van Tilburg T. The De Jong Gierveld short scales for emotional and social loneliness: tested on data from 7 countries in the UN generations and gender surveys. Eur J Ageing. 2010;7:121–130. doi: 10.1007/s10433-010-0144-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ware J Jr., Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Puig Llobet M, Sánchez Ortega M, Lluch-Canut M, Moreno-Arroyo M, Hidalgo Blanco M, Roldán-Merino J. Positive mental health and self-care in patients with chronic physical health problems: implications for evidence-based practice. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2020;17:293–300. doi: 10.1111/wvn.12453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mächler R, Sturm N, Frick E, Schalhorn F, Stolz R, Valentini J, Krisam J, Straßner C. Evaluation of a spiritual history with elderly multi-morbid patients in general practice—a mixed-methods study within the project HoPES3. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19 doi: 10.3390/ijerph19010538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huperz C, Sturm N, Frick E, Mächler R, Stolz R, Schalhorn F, et al. Experiences of health care professionals with a spiritual needs assessment in general practice—a mixed-method study within the HoPES3 project. Family Practice. 2022 doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmac106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jarvis MA, Padmanabhanunni A, Chipps J. An evaluation of a low-intensity cognitive behavioral therapy mhealth-supported intervention to reduce loneliness in older people. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16 doi: 10.3390/ijerph16071305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gensichen J, Jaeger C, Peitz M, Torge M, Guthlin C, Mergenthal K, et al. Health care assistants in primary care depression management: role perception, burdening factors, and disease conception. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7:513–519. doi: 10.1370/afm.1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lubben J, Blozik E, Gillmann G, Iliffe S, von Renteln Kruse W, Beck JC, et al. Performance of an abbreviated version of the Lubben Social Network Scale among three European community-dwelling older adult populations. Gerontologist. 2006;46:503–513. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.4.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwarzer R, Jerusalem M. Weinman J, Wright S, Johnston M, editors. Generalized self-efficacy scale Measures in health psychology: a user’s portfolio causal and control beliefs: Windsor, England. NFER-NELSON. 1995:35–37. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brenk-Franz K, Hibbard JH, Herrmann WJ, Freund T, Szecsenyi J, Djalali S, et al. Validation of the German version of the patient activation measure 13 (PAM13-D) in an international multicentre study of primary care patients. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074786. e74786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mahler C, Hermann K, Horne R, Ludt S, Haefeli WE, Szecsenyi J, et al. Assessing reported adherence to pharmacological treatment recommendations Translation and evaluation of the Medication Adherence Report Scale (MARS) in Germany. J Eval Clin Pract. 2010;16:574–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horne R, Weinman J, Hankins M. The beliefs about medicines questionnaire: the development and evaluation of a new method for assessing the cognitive representation of medication. Psychol Health. 1999;14:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wensing M, Mainz J, Grol R. A standardised instrument for patient evaluations of general practice care in Europe. Eur J Gen Pract. 2000;6:82–87. [Google Scholar]

- 29.GKV-Arzneimittelindex im Wissenschaftlichen Institut der AOK (WIdO) des AOK-Bundesverbandes GbR. ATC-Klassifikation. Berlin, Germany. Deutsches Institut für Medizinische Dokumentation und Information (DIMDI) www.dimdi.de/dynamic/.downloads/arzneimittel/atcddd/atc-ddd-amtlich-2019.pdf (last accessed on 11 August 2021) 2019 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods

Statistical methods

Sample size

According to the sample size calculation (11), 22 offices and 264 patients were required to detect a clinically relevant mean difference of 1 point on the SES6G scale (15) at a two-sided α of 0.05 with a power of 1 - ß = 0.8, assuming a standard deviation of σ = 2.2, an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.05, and a cluster size of m = 12. Anticipating dropout rates of 7.5% at office and 20% at patient level, n = 24 offices with n = 360 patients were recruited.

Randomization

Using sealed envelopes, block randomization of offices with a block length of 4, stratified by region, was conducted for 1:1 assignment to either intervention or control group. Allocation remained concealed from offices, patients, and the study nurse who had conducted the office visits until completion of the baseline assessment, with the exception of those patients recruited after the workshop had taken place. Blinding was not possible due to the nature of the intervention.

Statistical analysis

The primary efficacy analysis was performed by fitting a linear mixed model including the SES6G score at T1 as dependent variable; treatment group, gender, SES6G score at T0, age, and number of medications as fixed factors; and office as a random factor. The fixed factors gender, age, number of medications, and SES6G score at T0 were included in the primary analysis model due to their assumed association with the primary outcome. Adjustment for these factors was performed in order to improve the efficiency of the model and to enable adjustment for these factors in the event of imbalances between the two treatment arms.

The primary analysis was conducted adhering to the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle, i.e., all patients and offices that fulfilling the inclusion criteria were included, even if they refused or discontinued the intervention or other protocol deviations occurred.

As sensitivity analyses, a per-protocol (PP) analysis and a modified per-protocol (mPP) analysis were carried out. The PP population consisted of all ITT patients with the exception of those patients from the intervention group who stated in the questionnaire that they had not undergone spiritual history taking. The mPP population comprised all patients of the PP population who stated they had undergone spiritual history taking and additionally another element of the HoPES3 intervention (information about home remedies and/or social activities) and the patients of the control group.

Missing data for the primary outcome were replaced in the primary analysis by means of multiple imputation.

The secondary endpoints were assessed analogously to the primary endpoint.

Subgroup analyses for the primary and secondary endpoints were conducted by including further interaction terms into the respective model. In total, five subgroup pairs were defined according to baseline data as outlined in the legend of Table 2:

Since this is an exploratory trial, the resulting p-values are not confirmatory and should be interpreted descriptively only.

All statistical procedures including allocation of the patients to the ITT, PP, and mPP populations are described in the study’s statistical analysis plan, which was finalized before database lock (except for subgroups 2, 3, and 5), and can be requested from the authors. Analyses were performed with SAS version 9.4.

Deviations from the study protocol

Due to an error in wording, we could not, as planned, analyze the long version of the De-Jong-Gierveld loneliness scale (DJGS-11); instead, we used the short version (DJGS-6) (16).

Spiritual versus non-spiritual patients

Lonely versus non-lonely patients

Patients with a large versus small social network

Home remedy users versus non-home remedy users

Patients with versus without prescription of psychotropic drugs