Abstract

Background

The use of marijuana (MJ), combustible cigarettes (hereafter cigarettes), and electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) is widespread among United States (US) adults and linked to worsening respiratory symptoms, especially among adults with asthma. This study examined state-specific prevalence and factors associated with MJ, ENDS, and cigarette use among US adults with asthma.

Methods

We analyzed data of 41 974 adults aged ≥18 years having self-reported current asthma from the 2018 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS). We reported weighted prevalence to account for complex survey design and performed multivariable logistic regression models to examine factors associated with current use of MJ, ENDS, and cigarettes.

Results

Overall prevalence of current MJ, ENDS, and cigarette use among adults with asthma was 14.5%, 6.6%, and 27.2%, respectively. Our results showed the US states and territories with highest and lowest use prevalence for MJ (California: 23.6% vs Guam: 3.2%), ENDS (Indiana: 12.8% vs North Dakota: 4.0%), and cigarettes (West Virginia: 42.1% vs Guam: 12.3%). Both MJ and ENDS users were more likely to be male, younger, and live in an urban area, but MJ users were more likely and ENDS users less likely to be Non-Hispanic (NH) American Indian/Alaskan Native. Cigarette users were more likely to be older, have at least 1 health condition, and were less likely to be NH Black or Hispanic and college-educated.

Conclusion

Many US adults with asthma use MJ, ENDS, and cigarettes. Our findings provide insights for clinicians about the urgent need for effective interventions to reduce tobacco and MJ use among adults with asthma.

Introduction

Asthma is a major non-communicable disease, affecting more than 25 million children and adults in the United States (US) with a mortality rate of 10.7 per million. 1 Substance use, either legal (eg, tobacco products) or illegal (eg, cocaine), can accelerate the decline in lung function and increase life-threatening asthma attacks and asthma mortality.2,3 Well-established evidence shows that combustible cigarettes (hereafter cigarettes) smoking can adversely affect clinical, prognostic, and therapeutic outcomes in adults with asthma.4-6 Emerging evidence also shows that electronic nicotine delivery system (ENDS) use may worsen asthma symptoms. 7 Marijuana (MJ) is another apparent popular substance among adults. While the health effects of MJ use on asthma remain controversial among clinicians, 8 its use can cause an asthma attack leading to hospitalization and even death. 9

Ongoing legalization of MJ across the US has coincided with the popularity of ENDS use.10-12 Therefore, it is crucial to understand the state-specific prevalence of MJ and ENDS use along with cigarette use among adults with asthma to inform clinicians and regulatory bodies. Here, we sought to assess state-specific prevalence and factors associated with MJ, ENDS, and cigarette use among adults with asthma in the US.

Methods

We analyzed data for participants aged ≥18 years using the 2018 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS). It comprises telephone surveys conducted by all 50 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Guam. 13 Of the 437 436 respondents, 41 974 reported currently having asthma. We limited our analysis to adults with asthma who provided information on their current use of MJ (n=10 381), ENDS (n=25 280), and cigarettes (n=28 878). Since BRFSS is publicly deidentified state-level data, it is not required to obtain IRB approval.

Measures

Covariates

Assessed covariates included sex, race/ethnicity, education level, age, body mass index, binge and heavy alcohol drinking, residence (urban/rural), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and having ≥1 chronic health condition. 14 Previous studies15,16 found alcohol intake as a trigger for an asthma attack or a risk for developing adult-onset asthma. Therefore, we included the history of alcohol consumption as a potential covariate. Additionally, since COPD and asthma coexist in some patients, 17 we accounted for having COPD in our analysis (see details for covariates in Table 1 footnote).

Table 1.

Weighted prevalence and factors associated with current marijuana, ENDS, and cigarette use among adults with current asthma, BRFSS 2018 (n= 41 974)

| Current MJ use (n=10 381) | Current ENDS use (n= 25 280) | Current Cigarette use (n=28 878) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (yes vs no) | (yes vs no) | (yes vs no) | ||||

| Weighted%(95%CI) | AOR (95%CI) | Weighted % (95%CI) | AOR (95%CI) | Weighted%(95%CI) | AOR (95%CI) | |

| Overall | 14.45 (12.82-16.07) | –– | 6.5873 (5.90-7.26) | –– | 27.17 (26.11-28.23) | –– |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 51.88(45.63-58.14)¥ | 1 (Reference) | 52.84 (47.36- 58.32)¥ | 1 (Reference) | 64.30(62.07-66.52)¥ | 1 (Reference) |

| Male | 48.12 (41.86-54.37) | 1.82 (1.28-2.60) * | 47.16 (41.68- 52.64) | 2.38 (1.29-4.38) * | 35.70 (33.48-37.93) | 1.23 (.86-1.77) |

| Age, years | ||||||

| 18-24 | 22.25 (16.68-27.82)¥ | 5.74 (2.77-11.91) * | 31.85 (26.79-36.92)¥ | 40.14 (12.95-124.43) * | 9.55 (8.16- 10.93)¥ | 1.20 (.50-2.89) |

| 25-34 | 25.21 (19.98-30.44) | 4.67 (2.28-9.56) * | 26.32 (21.03-31.61) | 9.91 (3.47-28.34) * | 21.14 (19.14-23.14) | 9.35 (5.43-16.07)* |

| 35-44 | 18.54 (13.24-23.84) | 1.85 (.92-3.72) | 16.03 (11.94- 20.12) | 9.57 (3.64-25.21) * | 19.29 (17.45-21.13) | 9.35 (5.66-15.44)* |

| 45-54 | 13.14 (8.94- 17.35) | 1.53 (.75-3.11) | 12.76 (9.72- 15.79) | 5.44 (2.14-13.83) * | 21.19 (19.13-23.25) | 6.49 (4.15-10.14)* |

| 55-64 | 11.63 (8.80-14.46) | 1.29 (.66-2.54) | 9.79 (7.64- 11.94) | 3.80 (1.58-9.14) * | 19.79 (18.20-21.38) | 4.03 (2.62-6.22)* |

| ≥65 | 9.22 (5.78- 12.67) | 1 (Reference) | 3.25 (2.29- 4.21) | 1 (Reference) | 9.04 (8.01- 10.08) | 1 (Reference) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| NH White | 48.25 (42.11-54.38)¥ | 1 (Reference) | 67.15 (61.63- 72.67)¥ | 1 (Reference) | 65.90(63.53-68.27)¥ | 1 (Reference) |

| NH Black | 16.27 (11.17-21.36) | 1.79 (1.12-2.88) * | 11.04 (7.35-14.72) | .58 (.23-1.44) | 15.08 (13.33-16.82) | .44 (.24-.82)* |

| Hispanic | 23.72 (17.66-29.79) | 1.60 (.95-2.69) | 14.08 (9.11- 19.05) | .30 (.11-.80) * | 11.67 (9.73- 13.61) | .44 (.25-.78)* |

| NH American Indian/Alaskan Native | 3.73 (1.73- 5.73) | 6.28 (3.02-13.09)* | 1.55 (.63- 2.47) | .16 (.03-.83) * | 3.20 (2.10- 4.29) | 1.34 (.60-3.01) |

| NH Asian | 3.87 (.09-7.64) | .82 (.32-2.09) | 1.06 (.23 -1.90) | .89 (.19-4.27) | .57 (.29- .85) | .21 (.04-1.12) |

| NH Other | 4.17 (2.39- 5.94) | 1.78 (.87-3.63) | 5.12 (3.13- 7.10) | .46 (.17-1.25) | 3.58 (3.03-4.14) | .94 (.52-1.69) |

| BMI | ||||||

| Normal | 31.66(25.88-37.44)¥ | 1 (Reference) | 30.26 (25.43- 35.09)¥ | 1 (Reference) | 25.81(23.91-27.71)¥ | 1 (Reference) |

| Underweight | 3.49 (1.00- 5.98) | .56 (.19-1.64) | 4.82 (2.00- 7.65) | 3.80 (1.03-13.99) * | 3.37 (2.57- 4.17) | 3.00 (1.17-7.72) * |

| Overweight | 31.23 (25.33-37.13) | .95 (.61-1.46) | 28.13 (23.40- 32.86) | .73 (.35-1.55) | 28.13 (25.98-30.29) | 1.12 (.72-1.76) |

| Obese | 33.61 (27.68-39.54) | .56 (.37-.86)* | 36.79 (31.17- 42.41) | .74 (.40-1.37) | 42.69 (40.30-45.07) | .75 (.51-1.10) |

| Education | ||||||

| <high school | 18.03(12.21-23.85)¥ | 1 (Reference) | 21.27 (15.66- 26.88)¥ | 1 (Reference) | 28.97(26.63-31.31)¥ | 1 (Reference) |

| Highschool | 28.47 (23.19-33.76) | .98 (.57-1.69) | 35.55 (30.70-40.39) | 1.43 (.57-3.57) | 33.68 (31.55-35.80) | .67 (.37-1.22) |

| Some college | 37.82 (31.70-43.94) | .96 (.55-1.68) | 33.69 (28.69-38.69) | 1.85 (.72-4.75) | 29.41 (27.40-31.42) | .40 (.22-.72) * |

| College graduate | 15.68 (12.32-19.04) | 1.06 (.60-1.85) | 9.49 (7.39- 11.59) | .60 (.23-1.57) | 7.95 (7.06- 8.83) | .13 (.07-.24) * |

| Current Cigarette use | ||||||

| No | 48.23 (41.14-55.32)¥ | 1 (Reference) | 31.06 (25.10-37.03)¥ | 1 (Reference) | –– | –– |

| Yes | 51.77 (44.68-58.86) | 3.34 (2.21-5.06) * | 68.94 (62.97- 74.90) | 5.61 (2.77-11.37)* | –– | –– |

| Current ENDS use | ||||||

| No | 83.02(78.44-87.60)¥ | 1 (Reference) | –– | –– | 83.31(81.04-85.58)¥ | 1 (Reference) |

| Yes | 16.98 (12.40-21.56) | 1.74 (.89-3.39) | –– | –– | 16.69 (14.42-18.96) | 4.46 (2.07-9.60)* |

| Current MJ use | ||||||

| No | –– | –– | 54.44 (44.41- 64.48)¥ | 1 (Reference) | 70.76(66.14-75.38)¥ | 1 (Reference) |

| Yes | –– | –– | 45.56 (35.52- 55.59) | 2.06 (1.09-3.90) * | 29.24 (24.62-33.86) | 3.27 (2.11-5.08) * |

| Binge alcohol use a | ||||||

| No | 67.28(61.16-73.40)¥ | 1 (Reference) | 69.27 (64.34-74.20)¥ | 1 (Reference) | 77.46(75.45-79.47)¥ | 1 (Reference) |

| Yes | 32.72 (26.60-38.84) | 3.68 (2.24-6.03) * | 30.73 (25.80- 35.66) | 1.66 (.74-3.74) | 22.54 (20.53-24.55) | 2.91 (1.59-5.35) * |

| Heavy alcohol use a | ||||||

| No | 86.53(81.77-91.30)¥ | 1 (Reference) | 88.48 (85.28-91.67)¥ | 1 (Reference) | 88.10(86.40-89.81)¥ | 1 (Reference) |

| Yes | 13.47 (8.70- 18.23) | .65 (.31-1.38) | 11.52 (8.33-14.72) | 1.63 (.56-4.79) | 11.90(10.19-13.60) | 2.17 (.98-4.81) |

| COPD b | ||||||

| No | 75.46 (70.72-80.20) | 1 (Reference) | 71.78 (67.38- 76.19) | 1 (Reference) | 56.91(54.67-59.16)¥ | 1 (Reference) |

| Yes | 24.54 (19.80-29.28) | 1.38 (.90-2.11) | 28.22 (23.81-32.62) | 1.48 (.71-3.12) | 43.09 (40.84-45.33) | 4.50 (3.10-6.52) * |

| ≥1 health condition | ||||||

| No | 33.11 (26.86-39.36) | 1 (Reference) | 29.97 (25.17-34.77) | 1 (Reference) | 21.27(19.18-23.36)¥ | 1 (Reference) |

| Yes | 66.89 (60.64-73.14) | 1.56 (1.05-2.33) * | 70.03 (65.23-74.83) | 1.54 (.77-3.08) | 78.73 (76.64-80.82) | 2.40 (1.59-3.61) * |

| Residence | ||||||

| Rural | 2.75 (1.93- 3.57)¥ | 1 (Reference) | 8.11 (3.71- 12.52) | 1 (Reference) | 8.51 (7.39- 9.63)¥ | 1 (Reference) |

| Urban | 97.25 (96.43-98.07) | 1.83 (1.10-3.02) * | 91.89 (87.48-96.29) | 2.00 (1.01-3.98) * | 91.49 (90.37-92.61) | .96 (.67-1.38) |

Abbreviations: AOR, Adjusted odds ratio; CI, Confidence interval; MJ, Marijuana; ENDS, Electronic nicotine delivery system; NH, non-Hispanic; COPD, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Sign (¥) denotes a Rao Scot X2 test, which was performed for the univariate analysis of the difference in substance use (marijuana, ENDS, cigarettes) by study covariates. Sign (*) indicates significant AORs.

aBinge alcohol drinker (defied as males having 5 or more drinks on 1 occasion, females having 4 or more drinks on 1 occasion), heavy drinkers (defined as males having more than 14 drinks per week and females having more than 7 drinks per week).

bThe report of having COPD was included in the analysis independently. Those who responded “yes” to “Do you still have asthma?” were considered as currently having asthma.

Outcome Variables

Adults who reported using MJ at least 1 day in the past 30 days were categorized as current users (yes vs no). Those who responded “yes” to questions “Have you smoked at least 100 cigarettes in your entire life?” and “Have you ever used an ENDS…even just 1 time, in your entire life?” and reported using these products on “some days” or “every day” at the time of interview were classified as current users of cigarettes and ENDS, respectively. 18 For cigarettes and ENDS users, those who responded with “no” to the aforementioned questions and were not using these products at the time of interview were classified as non-current users of cigarettes and ENDS. Therefore, the outcome for the 2 tobacco products (cigarettes and ENDS) and for MJ were binary coded as “yes” (current use) vs “no” (non-current use), considering the non-current user group (“no”) as the reference group.

Statistical Analyses

All estimates were weighted using SAS procedures to provide nationally representative and unbiased measures, adjusting for differences in selection probability and nonresponse while accounting for design features. Detailed weighing information for 2018 BRFSS can be found on CDC website. 19 To examine factors associated with current use (yes vs no [reference group]) of MJ, ENDS, and cigarettes, we applied 3 separate multivariable logistic regression models (1 for each assessed substance) accounting for all above-mentioned covariates. Analyses were conducted in SAS v.9 with a significance level set at α=.05.

Results

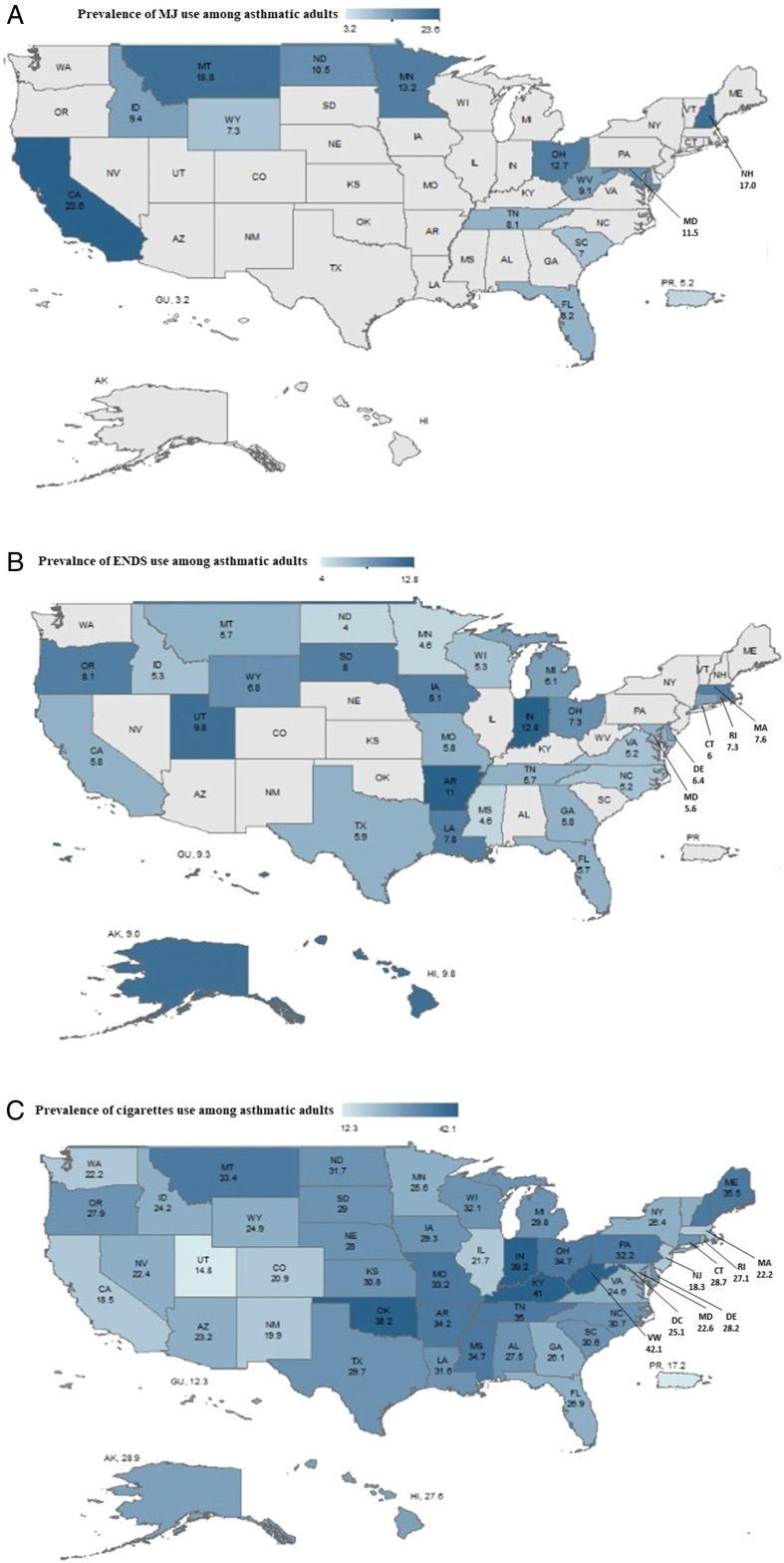

Weighted prevalence of current MJ, ENDS, and cigarettes use among adults with asthma were 14.5%, 6.6%, and 27.2%, respectively. Figure 1 illustrates a large variation in the use of these products among adults with asthma across the US states and territories, with the highest and lowest use prevalence of MJ (California (CA): 23.6% vs Guam: 3.2%), ENDS (Indiana: 12.8% vs North Dakota: 4.0%), and cigarettes (West Virginia (WV): 42.1% vs Guam: 12.3%).

Figure 1.

Maps show the percentage of current MJ use (panel A), ENDS use (panel B), and cigarette use (panel C) among adults with current asthma. Note: All states participated in the cigarette module in the 2018 BRFSS survey. Only 31 and 13 states participated in ENDS and MJ use modules, respectively. Data were not available for states indicated in gray.

Adults with asthma who use MJ were more likely to be male, aged 18-34 (compared to ages ≥65), non-Hispanic (NH) Black or NH American Indian/Alaskan Native (compared to NH White), current users of cigarettes and binge drinkers, have at least 1 health condition, reside in an urban area, and less likely to be obese (Table 1). Those who use ENDS were more likely to be male, younger than 65 years (with greatest odds in the 18-24 years old group), current users of cigarettes and MJ, resided in an urban area, and less likely to be Hispanic or NH American Indian/Alaskan Native. Adults with asthma who smoked cigarettes were more likely to be younger than 65 years old, underweight, current users of ENDS, MJ, binge drinkers, reported having a chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and at least 1 other health condition, and less likely to be NH Black or Hispanic, and college-educated (Table 1).

Discussion

This nationally representative study demonstrated that a large proportion of adults with asthma in the US were using MJ, ENDS, and cigarettes with a wide variation across the country. In 2018, 14.5% of adults with asthma were current users of MJ, 6.6% current users of ENDS, and 27.2% current users of cigarettes. 20 These proportions are higher than what was reported for all US adults in the same year (11% MJ use, 3.2% ENDS use, and 13.7% cigarette use).18,20 These differences demonstrate the popularity of these products among adults with asthma and call for urgent actions to curb substance use among adults with asthma.

The variation and differences in characteristics of MJ, ENDS, and cigarettes use patterns among adults with asthma in the US signal the importance of targeted interventions to curb preventable triggers of asthma attacks and improve the quality of life of these patients. For example, findings from our study show that adults with asthma in CA were more likely to use MJ than in other states. This is unsurprising, given that CA has been at the forefront of legalizing MJ use in the US 21 . On the other hand, adults with asthma in WV were more likely to use cigarettes than in other states, which was also expected since smoking is embedded in the culture of a state considered 1 of the top tobacco producers in the US.22,23 These geographical differences have important clinical implications since clinicians can provide more product-focused interventions to increase awareness about health effects among adults with asthma based on their state of residence.

Limitations should be noted. The cross-sectional nature of the BRFSS precludes the causal relationships. The BRFSS does not collect MJ data from all US states or territories; therefore, it may not be fully generalizable to the states with different MJ legalization statutes. Although self-reported asthma condition is subject to social desirability bias, the psychometric validity of BRFSS data on health conditions has been confirmed in previous studies.24,25 In this study, we focused only on current users of these products (vs. non-users). Unlike other tobacco-specific datasets (eg, PATH), the BRFSS dataset does not include specific variables to confirm former use of tobacco products, thus, we were not able to conduct a more granular analysis of former and experimental use of these tobacco products. Therefore, future studies are warranted to include never users and how it differs from former users among adults with asthma, including adolescents.

A large nationally representative sample of adults with asthma in the US use MJ, ENDS, and cigarettes at higher rates than national estimates. Our findings provide insights for clinicians regarding the exclusive and concurrent use of these products among adults with asthma and associated factors. Additionally, our results will help develop effective public health policies urgently needed in light of the ongoing legalization of MJ and the popularity of ENDS in the US.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs

Mohammad Ebrahimi Kalan https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7709-5392

Wei Li https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7530-3485

Abir Rahman https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3854-4655

Kenneth D Ward https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8972-538X

References

- 1.Center for Diseases Control and Prevention . Most Recent National Asthma Data; 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/most_recent_national_asthma_data.htm. Accessed 27 Nov 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caponnetto P, Auditore R, Russo C, Alamo A, Campagna D, Demma S, et al. Dangerous relationships": asthma and substance abuse. J Addict Dis. 2013;32(2):158-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Self TH, Shah SP, March KL, Sands CW. Asthma associated with the use of cocaine, heroin, and marijuana: A review of the evidence. J Asthma. 2017;54(7):714-722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomson NC, Chaudhuri R, Livingston E. Asthma and cigarette smoking. Eur Respir J. 2004;24(5):822-833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cerveri I, Cazzoletti L, Corsico AG, Marcon A, Niniano R, Grosso A, et al. The impact of cigarette smoking on asthma: a population-based international cohort study. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2012;158(2):175-183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Polosa R, Thomson NC. Smoking and asthma: dangerous liaisons. Eur Respir J. 2013;41(3):716-726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kotoulas S-C, Katsaounou P, Riha R, Grigoriou I, Papakosta D, Spyratos D, et al. Electronic Cigarettes and Asthma: What Do We Know So Far? J Pers Med. 2021;11(8):723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reisfield G, DuPont RJTNEJoM. Recommend against the Medicinal Use of Marijuana: Option 2. 2013;368(9):867-868. [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Thoracic Society . Smoking Marijuana and the Lungs. Am J Respir Crit. 2017;195(3):P5-P6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Procon. Legal . Medical Marijuana States and DC as of Feburary 9 2021; 2021. https://medicalmarijuana.procon.org/legal-medical-marijuana-states-and-dc/. Accessed April 30 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cassidy RN, Meisel MK, DiGuiseppi G, Balestrieri S, Barnett NP. Initiation of vaporizing cannabis: Individual and social network predictors in a longitudinal study of young adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;188:334-340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uddin SMI, Osei AD, Obisesan OH, El-Shahawy O, Dzaye O, Cainzos-Achirica M, et al. Prevalence, Trends, and Distribution of Nicotine and Marijuana use in E-cigarettes among US adults: The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System 2016-2018. Preventive medicine. 2020;139:106175-106175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . BRFSS Survey Data and Documentation; 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/annual_2020.html. Accessed March 29 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dai H, Richter KP. A National Survey of Marijuana Use Among US Adults With Medical Conditions, 2016-2017. JAMA Network Open. 2019;2(9):e1911936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vally H, de Klerk N, Thompson PJ. Alcoholic drinks: important triggers for asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105(3):462-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lieberoth S, Backer V, Kyvik KO, Skadhauge LR, Tolstrup JS, Gronbæk M, et al. Intake of alcohol and risk of adult-onset asthma. Respir Med. 2012;106(2):184-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Marco R, Pesce G, Marcon A, Accordini S, Antonicelli L, Bugiani M, et al. The coexistence of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): prevalence and risk factors in young, middle-aged and elderly people from the general population. PloS One. 2013;8(5):e62985-e62985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS); 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/. Accessed March 29 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weights CDC. Complex SamplingThe Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS); 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/2018/pdf/Complex-Smple-Weights-Prep-Module-Data-Analysis-2018-508.pdf. Accessed 4 May 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Creamer MR, Wang TW, Babb S, Cullen KA, Day H, Willis G, et al. Tobacco Product Use and Cessation Indicators Among Adults - United States, 2018. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2019;68(45):1013-1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baldassare M, Lopes L, Bonner D. Californians’ attitudes toward marijuana legalization. Public Policy Institue of California; 2015. https://www.ppic.org/publication/californians-attitudes-toward-marijuana-legalization/. Accessed Dec 18 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 22.The West Virginia Division of Tobacco . The Division of Tobacco Prevention. 2021. https://dhhr.wv.gov/wvdtp/pages/default.aspx. https://dhhr.wv.gov/wvdtp/pages/default.aspx.Accessed Dec 18 2021.

- 23.Tobacco in Virginia. 2021. http://www.virginiaplaces.org/agriculture/tobacco.html. Accessed Dec 18 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fahimi M, Link M, Mokdad A, Schwartz DA, Levy P. Tracking chronic disease and risk behavior prevalence as survey participation declines: statistics from the behavioral risk factor surveillance system and other national surveys. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008;5(3):A80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li C, Balluz LS, Ford ES, Okoro CA, Zhao G, Pierannunzi C. A comparison of prevalence estimates for selected health indicators and chronic diseases or conditions from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, the National Health Interview Survey, and the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2007-2008. Prev Med. 2012;54(6):381-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]