Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) is increasing among pediatric patients in the United States. Previous studies on obesity as a risk factor have produced mixed results.

METHODS:

We completed a retrospective chart review of patients aged 2 to 18 years with VTE identified by using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, codes and confirmed by imaging. Patients were admitted between January 2000 and September 2012. Control subjects were matched on age, gender, and the presence of a central venous catheter. Data were collected on weight, height, and risk factors, including bacteremia, ICU admission, immobilization, use of oral contraceptives, and malignancy. Underweight patients and those without documented height and weight data were excluded. Independent predictors of VTE risk were identified by using univariate and multivariate analyses.

RESULTS:

We identified 88 patients plus 2 matched control subjects per case. The majority of cases were nonembolic events (77%) of the lower extremity (25%) or head and neck (22%) confirmed by ultrasound (43%) or computed tomography scan (41%). A statistically significant association was found between VTE and increased BMI z score (P = .002). In multivariate analysis, BMI z score (odds ratio [OR]: 3.1; P = .007), bacteremia (OR: 4.9; P = .02), ICU stay (OR: 2.5; P = .02), and use of oral contraceptives (OR: 17.4; P < .001) were significant predictors.

CONCLUSIONS:

In this single-institution study, the diagnosis of VTE was significantly associated with overweight and obesity. Further study is needed to fully define this association.

Dramatic increases in the incidence of pediatric venous thromboembolism (VTE) have been documented over the last 20 years,1,2 with estimates of prevalence ranging from 10 to 58 per 10 000 admissions.1,3,4 Several groups are currently developing guidelines for thromboprophylaxis for at-risk pediatric inpatients to help prevent this complication,5,6 which results in substantial morbidity for affected children.7,8

Multiple risk factors for pediatric VTE have been identified, including mechanical ventilation,9 presence of a central venous catheter (CVC),4,5,9,10 bloodstream infection,4,5,10 direct admission to an ICU,10 use of estrogen-containing birth control pills, and prolonged hospitalization.5,9,10

Obesity is a well-established risk factor for VTE in adults11,12; however, studies in pediatric populations have yielded mixed results.9,10,13,14 Pediatric overweight and obesity remain highly prevalent in the United States, affecting >30% of children,15 with continued increases in the rates of severe obesity.16 In addition, children with obesity require increased enoxaparin dosing for prophylaxis of VTE,17 and it is therefore important to identify the risk of VTE in this population.

The objective of the present study was to evaluate the association between obesity and VTE in children. The study used a case–control design with matching based on the presence of a CVC, a significant risk factor for pediatric VTE.4,5,9,10 We hypothesized that obesity would have a positive association with VTE, especially among adolescents whose physiology may more closely resemble that of adults.

METHODS

This retrospective case–control study was approved by the institutional review board at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center, Winston-Salem, North Carolina. It included children ages 2 to 18 years admitted to Brenner Children’s Hospital between January 2000 and September 2012; this institution had no standing protocol for pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis during this time. Cases were identified by using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, codes listed in Supplemental Table 4. All cases were confirmed by review of the radiology report from imaging studies documented in the medical record. Two control subjects matched on age, gender, and the presence or absence of a CVC were identified for each case subject. Control subjects were identified by age <18 years and Current Procedural Terminology codes specific to hospital admission (99222 and 99223) and CVC placement (36555, 36556, 36557, 36558, 36560, 36561, 36563, 36565, 36566, 36568, 36569, 36570, and 36571). Current CVC status for both case and control subjects was verified during primary chart review. Exclusion criteria included patients with no documented height and weight data and those who were underweight. Underweight patients were excluded due to their high likelihood of a concurrent pathologic condition that would confound the analysis.

Data were collected on both case subjects and control subjects by retrospective chart review. Demographic data on patient age, date of admission, and gender were extracted. In addition, we collected clinical data on length of stay (LOS), height, weight, and previously established risk factors for VTE. These risk factors included the presence of a CVC, bacteremia, ICU admission, immobilization, use of estrogen containing oral contraceptives (OCPs), and malignancy. For case subjects, data on the type and location of the thromboembolic event as well as the confirmatory imaging study were recorded. Height and weight were used to calculate BMI, BMI percentile, BMI category, and BMI z score according to the guidelines of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: underweight, <5%; normal weight, 5% to <85%; overweight, 85% to <95%; and obese, ≥95%.18,19

Descriptive statistics were used to determine frequencies and proportions of categorical variables, which were compared between case and control subjects by using the Pearson x2 tests or Fisher exact tests. BMI, BMI z score, and hospital LOS were also considered as continuous variables and compared between case and control subjects by using an analysis of variance model. Unadjusted associations between risk factors and case/control status were performed with univariate logistic regression and reported as odds ratios (ORs) with accompanying 95% confidence intervals (CIs) by using the Wald method. In addition, multivariate logistic regression was used to isolate weight status as a risk factor for case/control status. A significance value of P < .1 was used for inclusion of variables in the multivariate regression; P < .05 was otherwise used as a significance cutoff for all hypothesis testing. Statistical analysis was performed by using SPSS version 22 (IBM SPSS Statistics, IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY).

RESULTS

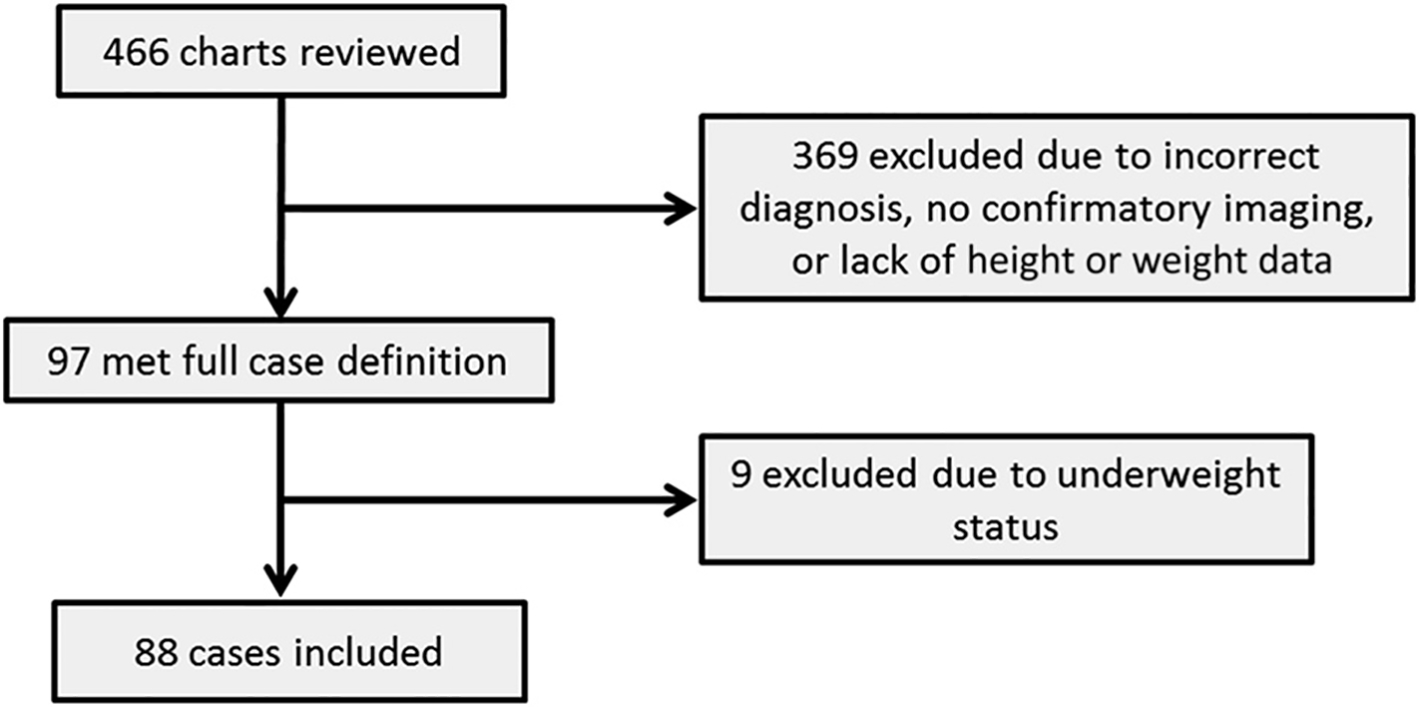

Searches conducted by using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, codes yielded 578 possible events in 466 patients. After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria (Fig 1), 88 cases were identified for study. The majority of the cases were nonembolic events (77%) of the lower extremity (25%) or head and neck (22%). Case definitions were confirmed by review of the radiology report, typically for ultrasound (43%) or computed tomography scan (41%). Details regarding the VTE events are included in Table 1. Two control subjects matched on age (within 6 months), gender, and presence or absence of a CVC were identified for each case, with demographic information on case subjects and control subjects included in Table 2. Their mean age was 12 years; 45% were male, and 34% had a CVC. When considered as a categorical variable (P = .001) and a continuous variable (P = .002), weight status was significantly associated with identity as a case or control. Case subjects had a significantly longer LOS than control subjects (P < .001). All previously identified risk factors were significantly associated with identity as a case except malignancy. All case and control subjects identified as using OCPs were receiving estrogen; this factor had the strongest association with identity as a case, with an OR of 17.4 (95% CI: 3.6–83.6; P < .001). After multivariate logistic regression (Table 3), the BMI z score was significantly associated with case status (OR: 3.1 [95% CI: 1.4–7.0]; P = .007). A similar magnitude of association was seen in our study regarding ICU admission and bacteremia, which have previously been established as risk factors for VTE.4,5,10

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart of case selection.

TABLE 1.

Description of VTE Events (N = 88)

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Embolic event | |

| Thrombus | 68 (77) |

| Embolus | 13 (15) |

| Both | 7 (8) |

| Site | |

| Lower extremity | 22 (25) |

| Head and neck | 19 (22) |

| Pulmonary | 13 (15) |

| Other/multiple | 12 (14) |

| Upper extremity | 8 (9) |

| Superior/inferior vena cava | 7 (8) |

| Abdominal | 7 (8) |

| Confirmatory imaging | |

| Ultrasound | 38 (43) |

| Computed tomography scan | 36 (41) |

| MRI | 13 (15) |

| Angiography | 1 (1) |

TABLE 2.

Demographic Characteristics of Case and Control Subjects (Univariate Analysis)

| Characteristic | Case Subjects (n = 88) | Control Subjects (n = 176) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age | 11.9 ± 5.2 | 12.0 ± 5.1 | |

| Male gender | 40 (45) | 80 (45) | |

| Presence of CVC | 30 (34) | 60 (34) | |

| BMI category | .001 | ||

| Normal weight | 41 (47) | 122 (69) | |

| Overweight | 14 (16) | 12 (7) | |

| Obese | 33 (38) | 42 (24) | |

| BMI percentilea | 74.0 ± 30.0 | 64.5 ± 29.3 | .014 |

| BMI z scorea | 1.05 ± 1.2 | 0.58 ± 1.1 | .002 |

| LOSa | 16.2 ± 21.5 | 6.2 ± 8.0 | <.001 |

| Bacteremia | 9 (10) | 4 (2) | .012 |

| ICU stay | 26 (30) | 23 (13) | .001 |

| Immobilization >72 h | 23 (26) | 19 (11) | .001 |

| Use of OCPs | 11 (13) | 2 (1) | <.001 |

| Malignancy | 15 (17) | 23 (13) | .39 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD or n (%).

P value calculated by using an analysis of variance model; other P values were calculated by using the Pearson χ2 test or the Fisher exact test.

TABLE 3.

Significant Variables After Multivariate Logistic Regression

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Use of OCPs | 17.4 (3.6–83.6) | <.001 |

| Bacteremia | 4.9 (1.3–18.2) | .02 |

| BMI z score | 3.1 (1.4–7.0) | .007 |

| ICU admission | 2.5 (1.2–5.3) | .02 |

DISCUSSION

The present study found a small but significant association between obesity and pediatric VTE after adjusting for known risk factors. To our knowledge, this is the first case-control study to match on the presence or absence of a CVC when assessing this association. Our findings, based on a larger number of cases, are similar to those seen in previous studies.14 The age distribution of our case subjects (data not shown) was similar to that seen previously, with peaks in very young children and adolescents. The majority, although not all, of our case subjects had risk factors for VTE in addition to obesity, which is also consistent with earlier studies.

Some of our findings differ from previous results, however. Our patients had a higher percentage of head and neck thromboses than the national average.1,2 Furthermore, although concurrent malignancy has previously been well established as a risk factor for VTE,20,21 it was not significantly associated in the present univariate analysis. In previous studies, the association with malignancy may be partially confounded by the presence of a CVC, which is extremely common among oncology patients and which was addressed as a confounder in our study by matching.

There are several limitations to our study. Most importantly, the control subjects did not undergo systematic VTE screening to verify their status. It is therefore possible that control subjects could have been misclassified, which would bias our results toward the null. Similarly, we were unable to include thrombophilia in the analysis because none of our control subjects underwent an evaluation for this abnormality. It is possible that the association between BMI and VTE is mediated by another previously established risk factor for VTE. It is reassuring that the difference in BMI percentile between case and control subjects was not dramatic; therefore, we would not anticipate major clinical findings based solely on that difference. However, additional studies are needed to define the mechanism underlying the association we identified.

Our study represents data from a single institution with relatively small sample sizes given the rare nature of pediatric VTE. Our sample size was too small to assess the association between obesity and VTE within specific age ranges. However, many of our results are consistent with previously reported data on pediatric VTE, which reinforces the generalizability of these findings beyond our institution. For this small study, we did not include details about the type of CVC or OCP in the analysis, although these factors can affect the VTE risk associated with therapy.9 All data were collected retrospectively from within the electronic medical record. Future studies could include a multicenter prospective design with standardized screening for VTE and thrombophilia of all patients meeting inclusion criteria; this approach would minimize the information bias and other limitations found in the present study.

CONCLUSIONS

Knowledge of risk factors for pediatric VTE is important given the rising incidence of this condition. In this single-institution case-control study, we have demonstrated an association between obesity and pediatric VTE, which should be explored further in future studies.

Supplementary Material

FUNDING:

Supported in part by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development/National Institutes of Health Mentored Patient-Oriented Research Career Development Award (K23 HD061597) to Dr Skelton. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Footnotes

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Dr Halvorson conceptualized and designed the study, participated in data analysis, and drafted the initial manuscript; Drs Ervin, Russell, and Skelton assisted with study design, participated in data collection and data analysis, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Mr Davis and Dr Spangler assisted with case and control identification, participated in data analysis, and critically reviewed the manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Raffini L, Huang YS, Witmer C, Feudtner C. Dramatic increase in venous thromboembolism in children’s hospitals in the United States from 2001 to 2007. Pediatrics. 2009;124(4):1001–1008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boulet SL, Grosse SD, Thornburg CD, Yusuf H, Tsai J, Hooper WC. Trends in venous thromboembolism-related hospitalizations, 1994–2009. Pediatrics. 2012;130(4). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/130/4/e812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.A Setty B, O’Brien SH, Kerlin BA. Pediatric venous thromboembolism in the United States: a tertiary care complication of chronic diseases. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;59(2):258–264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim SJ, Sabharwal S. Risk factors for venous thromboembolism in hospitalized children and adolescents: a systemic review and pooled analysis. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2014;23(4):389–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atchison CM, Arlikar S, Amankwah E, et al. Development of a new risk score for hospital-associated venous thromboembolism in noncritically ill children: findings from a large single-institutional case-control study. J Pediatr. 2014;165(4):793–798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thompson AJ, McSwain SD, Webb SA, Stroud MA, Streck CJ. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in the pediatric trauma population. J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48(6):1413–1421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biss TT, Brandão LR, Kahr WH, Chan AK, Williams S. Clinical features and outcome of pulmonary embolism in children. Br J Haematol. 2008;142(5): 808–818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Journeycake JM, Manco-Johnson MJ. Thrombosis during infancy and childhood: what we know and what we do not know. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2004;18(6):1315–1338, viii–ix [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Branchford BR, Mourani P, Bajaj L, Manco-Johnson M, Wang M, Goldenberg NA. Risk factors for in-hospital venous thromboembolism in children: a case-control study employing diagnostic validation. Haematologica. 2012;97(4): 509–515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharathkumar AA, Mahajerin A, Heidt L, et al. Risk-prediction tool for identifying hospitalized children with a predisposition for development of venous thromboembolism: Peds-Clot clinical decision rule. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10(7):1326–1334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kabrhel C, Varraso R, Goldhaber SZ, Rimm EB, Camargo CA. Prospective study of BMI and the risk of pulmonary embolism in women. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2009;17(11):2040–2046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stein PD, Beemath A, Olson RE. Obesity as a risk factor in venous thromboembolism. Am J Med. 2005; 118(9):978–980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vu LT, Nobuhara KK, Lee H, Farmer DL. Determination of risk factors for deep venous thrombosis in hospitalized children. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43(6): 1095–1099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stokes S, Breheny P, Radulescu A, Radulescu VC. Impact of obesity on the risk of venous thromboembolism in an inpatient pediatric population. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2014;31(5): 475–480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. JAMA. 2014;311(8):806–814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skinner AC, Skelton JA. Prevalence and trends in obesity and severe obesity among children in the United States, 1999–2012. JAMA Pediatr. 2014; 168(6):561–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lewis TV, Johnson PN, Nebbia AM, Dunlap M. Increased enoxaparin dosing is required for obese children. Pediatrics. 2011;127(3). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/127/3/e787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ogden CL, Flegal KM. Changes in Terminology for Childhood Overweight and Obesity, National Health Statistics Report 25. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Guo SS, et al. 2000. CDC growth charts for the United States: methods and development. Vital Health Stat. 2002; (246):1–190 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chalmers EA. Epidemiology of venous thromboembolism in neonates and children. Thromb Res. 2006;118(1): 3–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Ommen CH, Heijboer H, Büller HR, Hirasing RA, Heijmans HSA, Peters M. Venous thromboembolism in childhood: a prospective two-year registry in The Netherlands. J Pediatr. 2001;139(5): 676–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.