Abstract

Background

Pembrolizumab is the recommended first‐line therapy for patients with advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and a programmed death ligand‐1 (PD‐L1) tumor proportion score (TPS) of ≥50% without driver mutations. However, its efficacy and safety for patients ≥75 years have not been prospectively investigated; this was the aim of this study.

Methods

This multicenter and open‐label single‐arm phase II study was conducted at 12 institutions. Chemotherapy‐naïve patients with advanced NSCLC and a PD‐L1 TPS of ≥50% without EGFR mutations or translocation of the ALK received pembrolizumab every 3 weeks. The primary endpoint was progression‐free survival (PFS) with a threshold of 4.3 months. The secondary endpoints were overall survival (OS), objective response rate (ORR), disease control rate (DCR), safety, and quality of life.

Results

Twenty‐six patients were enrolled between October 2017 and March 2020. The median PFS was 9.6 (95% confidence interval [CI] 2.1–20.6) months. The lower limit of the 95% CI did not exceed the target. The median OS was 21.6 months. The ORR and DCR were 41.7% and 70.8%, respectively. The proportion of patients with grade ≥3 treatment‐related adverse events was 15.4%. The quality of life score did not change significantly during treatment.

Conclusion

While this study showed that pembrolizumab was a tolerable treatment for elderly patients, the safety requires further confirmation in a larger study. Although the primary endpoint, the median PFS (9.6 months), was slightly shorter than that (10.3 months) of the previous phase III study (KEYNOTE‐024 study), the median PFS did not achieve the expected value.

Keywords: elderly patients, non‐small‐cell lung cancer, pembrolizumab, programmed death ligand‐1

This study showed that pembrolizumab monotherapy would be tolerable for advanced elderly patients with NSCLC having a PD‐L1 TPS of ≥50%. The primary endpoint, the median PFS (9.6 months), was slightly shorter than that (10.3 months) of the previous phase III study (KEYNOTE‐024 study). The median PFS did not achieve the expected value. A multicenter study of a large cohort in the future is needed to compare the safety and efficacy of pembrolizumab monotherapy.

INTRODUCTION

Lung cancer is the most common cause of cancer‐related death. 1 It is classified into two broad histological types: non‐small‐cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and small‐cell lung cancer. NSCLC comprises approximately 80% of lung cancers, and they are histologically classified as adenocarcinomas, squamous cell, large cell, or bronchioalveolar carcinoma. Approximately 50% of all NSCLC cases are advanced NSCLC. 2

Formerly, a platinum‐based doublet with third‐generation chemotherapy was the standard treatment for patients with NSCLC, a performance status of 0–1, and no driver mutations. However, antibodies against programmed death 1 (PD‐1; pembrolizumab or nivolumab) and programmed death ligand 1 (PD‐L1; atezolizumab) are the standard treatment options for advanced NSCLC. The KEYNOTE‐024 study, a randomized open‐label phase III trial, compared pembrolizumab and platinum‐based doublet chemotherapy as first‐line treatment for patients with advanced NSCLC, no driver mutations, and a PD‐L1 tumor proportion score (TPS) of ≥50%. 3 The primary endpoint was progression‐free survival (PFS), which was better in the pembrolizumab group than in the chemotherapy group (median 10.3 vs. 6.0 months, hazard ratio 0.50, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.37–0.68, p < 0.001). In addition, a recent updated analysis showed that the overall survival (OS) of the pembrolizumab group was significantly longer than that of the chemotherapy group (hazard ratio 0.62, 95% CI 0.48–0.81). 4 These results support pembrolizumab as the standard treatment for these patients. 5 However, that phase III study did not consider patients who were ≥75 years old.

Lung cancer is primarily a disease affecting the older population, and the number of older patients aged ≥75 years with lung cancer is increasing. 6 Several studies have shown the efficacy of PD‐1 antibody treatment in older patients with NSCLC. In fact, a previous study involving patients with squamous cell carcinomas who were treated with nivolumab after first‐line treatment showed that the median OS of patients aged >75 years (5.8 months) was lower than that of patients aged <65 years (8.6 months). 7 However, no prospective study on the efficacy and safety of pembrolizumab in elderly patients with NSCLC and a PD‐L1 TPS of ≥50% has been conducted.

The physiological functioning of elderly patients is lower than that of the nonelderly population. Therefore, systemic chemotherapy for elderly patients should be selected carefully to avoid adverse reactions. A randomized phase 3 trial (the IFCT‐0501) including elderly patients with NSCLC reported that the platinum‐doublet chemotherapy regimen improved survival compared with the single‐agent monotherapy regimen. 8 However, the rate of toxic deaths was slightly higher in the doublet chemotherapy group than in the monotherapy group. Thus, third‐generation chemotherapy agents were standard treatment options for elderly patients with NSCLC. 5 The WJTOG 9904 revealed the prevalence of grade 3 or 4 leukopenia and neutropenia, and febrile neutropenia was 58.0%, 82.9%, and 12.5 in the docetaxel group. 9 Conversely, the KEYNOTE‐024 study revealed that pembrolizumab was associated with fewer severe adverse events relative to platinum‐doublet chemotherapy (26.6% vs. 53.3%). 3 These results suggest that pembrolizumab monotherapy may be safer than platinum‐doublet chemotherapy or docetaxel treatment for elderly patients with NSCLC.

Based on these observations, this study aimed to examine the efficacy and safety of pembrolizumab monotherapy for patients aged ≥75 years with untreated advanced NSCLC and a PD‐L1 TPS of ≥50%.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Patients with pathologically confirmed NSCLC, with stage IIIB, IIIC, or IV (Tumor–Node–Metastasis Classification, 8th edition) or recurrence after surgical resection or chemoradiotherapy were enrolled in this study. 10 Patients with stage IIIB NSCLC were enrolled in our study when a physician determined that chemoradiotherapy was not suitable for these patients. Other eligibility requirements included age ≥75 years, performance status of 0 or 1, adequate bone marrow, lung, hepatic and renal functions, an expected survival of at least 3 months, absence of sensitizing epidermal growth factor receptor mutations or anaplastic lymphoma kinase translocations (analysis of BRAF gene mutation or ROS‐1 gene arrangement was not mandatory), PD‐L1 TPS ≥50% (22C3 pharmDx assay), no previous chemotherapy, and a treatment‐free period of more than 6 months after adjuvant chemotherapy. The exclusion criteria were untreated central nervous system metastases and/or carcinomatous meningitis, uncontrollable pleural effusion, ascites, or pericardial fluid, double cancer with a disease‐free interval below 5 years, evidence of severe or uncontrolled systemic disease, evidence of interstitial pneumonia on chest computed tomography (CT), any major surgical procedure (as defined by the investigators) within 28 days of the first pembrolizumab dose, radiotherapy within 4 weeks before the first pembrolizumab dose, and active autoimmune disease requiring systemic treatment with corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive medications.

Clinical study design

This was a multicenter single‐arm phase II study that evaluated the efficacy and safety of pembrolizumab as first‐line therapy for Japanese patients aged ≥75 years with advanced NSCLC and a PD‐L1 TPS of ≥50% without driver mutations. After the patient's eligibility was confirmed and informed consent was obtained, the patients were registered and treatment was initiated. Patients received intravenous pembrolizumab (200 mg every 3 weeks) until radiologic disease progression or treatment‐related adverse events of unacceptable severity were observed, the patient withdrew their consent, or the investigator terminated treatment at their own discretion. Ethical approval was obtained from the Hiroshima University Certified Review Board, Hiroshima, Japan (jRCTs061180068), and was approved by the Ethics Committee of each participating institution. In addition, this study protocol conformed to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and has been registered in the University Hospital Medical Information Network Clinical Trials Registry database (UMIN000029602).

Efficacy and assessments

Before treatment initiation, a physical examination, complete blood count and serum chemistry, CT or magnetic resonance imaging scan of the brain, thoracoabdominal CT, and bone CT or positron emission tomography were performed. Physical examination, a complete blood count, and serum chemistry were performed at least once during each subsequent cycle of treatment. Patients underwent tumor assessments every three treatment cycles or at least 9 weeks. The tumor response and/or radiologic disease progression was evaluated based on version 1.1 of the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors. 11 Adverse events were recorded using version 4.0 of the National Cancer Institute's Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events. 12 PFS was defined as the interval from the first day of therapy to the first instance of treatment failure, which included death and disease progression. OS was defined as the period from registration until death due to any cause.

Quality of life (QOL) was assessed using EORTC QLQ‐C30 and EORTC QLQ‐LC13. The patients completed the questionnaires immediately after providing informed consent, and also before the third, sixth, 12th, 18th, and 24th treatment cycles.

Statistical design

The primary endpoint was PFS. Secondary endpoints were OS, overall response rate (ORR), disease control rate, safety, and QOL. PFS and OS were analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier method to estimate the median points with 95% CI. ORR was the proportion of patients who achieved partial response (PR) and overall response (CR). The disease control rate was the proportion of patients who achieved CR, PR, and stable disease (SD). All these rates are expressed with their 95% CI. Changes in QOL were analyzed with reference to pretreatment scores. The sample size was based on a threshold median PFS of 4.3 months for previous single‐drug treatments, 9 , 13 an expected median PFS of 10.3 months 3 for this study, a two‐sided alpha value of 0.05, and power of 0.8. Based on these parameters, 24 patients needed to be enrolled within the first 3 years, with an additional 1 year of follow‐up. Therefore, the sample size was 26, assuming that some patients would drop out of the study.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

Twenty‐six patients were enrolled from 12 institutions between October 2017 and March 2020. All the patients received pembrolizumab and were included in the safety analysis (Figure 1). The patients' characteristics are shown in Table 1. The median age was 78 (range 75–90) years. Eighteen (69.3%) patients were men and eight (30.7%) were women. Five (19.2%) patients had stage III disease, 14 (53.9%) had stage IV disease, and seven (26.9%) experienced recurrence. Eighteen (69.2%) patients had adenocarcinoma, seven (26.9%) had squamous cell carcinoma, and one (3.9%) had pleomorphic carcinoma. The median PD‐L1 TPS was 80% (range 50–100). There was no patient with any EGFR mutation.

FIGURE 1.

Study flow chart

TABLE 1.

Patient characteristics

| Patient characteristics | n = 26 |

|---|---|

| Age, years | |

| Median (range) | 78 (75–90) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 18 (69.3) |

| Female | 8 (30.7) |

| PS, n (%) | |

| 0 | 16 (61.5) |

| 1 | 10 (38.5) |

| Smoking history, n (%) | |

| Current | 2 (7.7) |

| Former | 19 (73.0) |

| Never | 5 (19.3) |

| Histology, n (%) | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 18 (69.2) |

| Squamous | 7 (26.9) |

| Pleomorphic | 1 (3.9) |

| Stage, n (%) | |

| 3B | 2 (7.7) |

| 3C | 3 (11.5) |

| 4A | 4 (15.4) |

| 4B | 10 (38.5) |

| Recurrence | 7 (26.9) |

| PD‐L1 TPS (%) | |

| Median (range) | 80 (50–100) |

Abbreviations: PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; PD‐L1, programmed cell death ligand‐1; TPS, tumor proportion score.

Efficacy and survival analysis

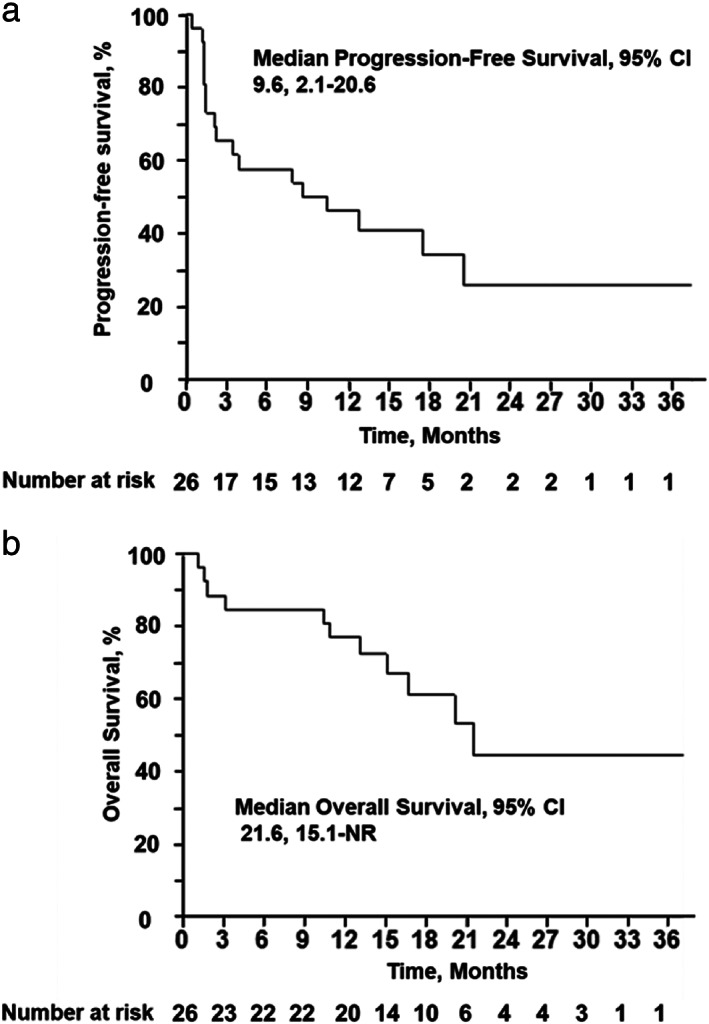

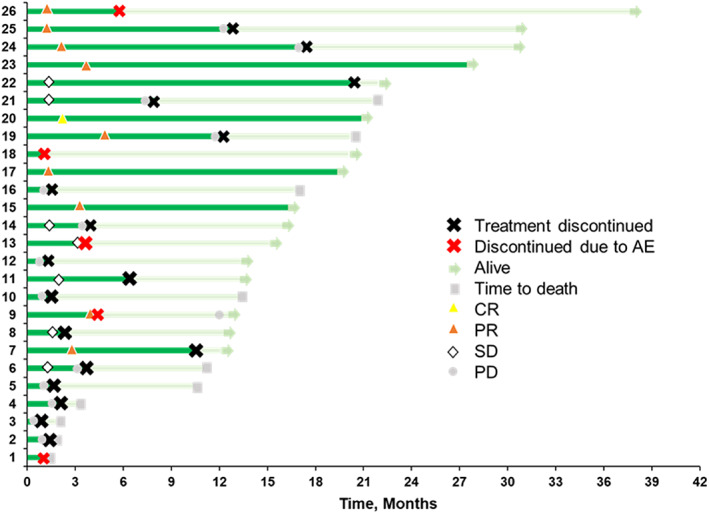

The median PFS was 9.6 (95% CI 2.1–20.6) months. By the end of the study (March 5, 2021, median follow‐up 15.1 months), 11 patients had died. The median OS was 21.6 (95% CI 15.1–not reached) months (Figure 2). The patient ORRs are shown in Table 2. CR, PR, and SD were achieved by one, nine, and seven patients, respectively (Figure 3). The ORR was 41.7% (95% CI 24.5–61.2). The disease control rate was 70.8% (50.8–85.1).

FIGURE 2.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of (a) progression‐free survival and (b) overall survival in patients with metastatic non‐small‐cell lung cancer treated with pembrolizumab. CI, confidence interval; NR, not reached

TABLE 2.

Overall response

| Tumor response | n = 26 (%) |

|---|---|

| Complete response | 1 (3.8) |

| Partial response | 9 (34.6) |

| Stable disease | 7 (26.9) |

| Progressive disease | 7 (26.9) |

| Not estimated | 2 (7.7) |

| Response rate | 41.7% (95% CI 24.5–61.2) |

| Disease control rate | 70.8% (95% CI 50.8–85.1) |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

FIGURE 3.

Duration of treatment and time‐to‐response. The bar lengths represent the duration of treatment (dark green) and months of follow‐up (light green). AE, adverse event; CR, complete response; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease

Safety

Treatment‐related adverse events are shown in Table 3. A total of 15.4% of patients developed grade 3, 4, or 5 adverse events. Adverse events led to treatment discontinuation in 19.2% of patients. The grade 3 adverse events included colitis (n = 1), hypothyroidism (n = 1), and pulmonary infection (n = 1). One patient developed grade 5 pneumonitis.

TABLE 3.

Summary of treatment‐related adverse events

| Treatment‐related adverse events, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Any grade | 20 (76.9) | |

| Grade 3–5 | 4 (15.4) | |

| Led to discontinuation | 5 (19.2) | |

| Led to death | 1 (3.8) | |

| Any grade, n (%) | Grade 3–5, n (%) | |

| Fatigue | 9 (33.5) | 0 (0) |

| Anorexia | 7 (26.9) | 0 (0) |

| Skin reaction | 7 (26.9) | 0 (0) |

| Colitis | 4 (15.4) | 1 (3.8) |

| Hepatitis | 4 (15.4) | 0 (0) |

| Increased blood creatinine level | 3 (11.5) | 0 (0) |

| Hypothyroidism | 2 (7.7) | 1 (3.8) |

| Pneumonitis | 2 (7.7) | 1 (3.8) |

| Lung infection | 2 (7.7) | 1 (3.8) |

Quality of life

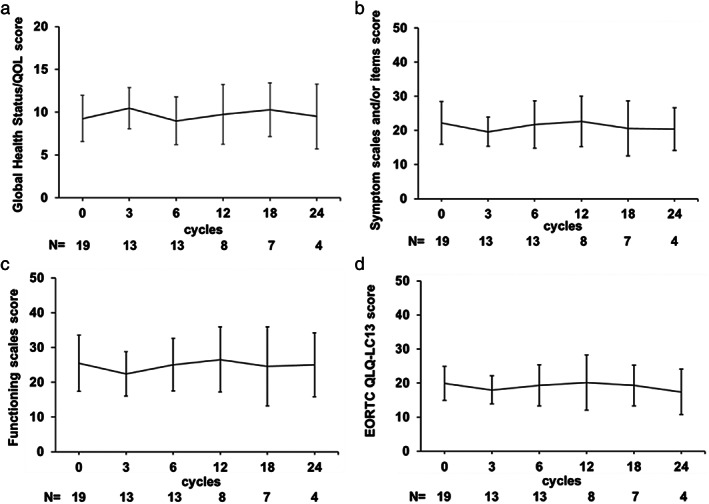

The distribution of patients who answered the questionnaires was as follows: 19 (73.1%) at the time of pretreatment, 13 (50.0%) after three treatment cycles, 13 (50.0%) after six cycles, eight (30.8%) after 12 cycles, seven (26.9%) after 18 cycles, and four (15.4%) after 24 cycles. The Score of Global Health Status/QOL, symptom scales and/or items, and functioning scales of EORTC QLQ‐C30 and EORTC QLQ‐LC13 did not change significantly during the treatment (Figure 4a–d).

FIGURE 4.

Quality‐of‐life assessments with EORTC QLQ‐C30 (a) score changes of Global Health Status/QOL, (b) symptoms and/or items score, (c) functioning scale score, (d) EORTC QLQ‐LC13 score. Scales of EORTC QLQ‐C30 and EORTC QLQ‐LC13 did not change significantly during the treatment. QOL, quality of life; QLQ, quality of life questionnaire

DISCUSSION

The subgroup analysis of the KEYNOTE‐024 study showed the PFS benefit of pembrolizumab in patients aged ≥65 years. 3 Unlike the KEYNOTE‐024 trial, this study included patients aged ≥75 years, with the oldest being 90 years. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first clinical trial to investigate the efficacy and safety of pembrolizumab as first‐line therapy for patients who are ≥75 years old with advanced NSCLC and a PD‐L1 TPS of ≥50%. Although the primary endpoint, the median PFS, was slightly shorter than that in the KEYNOTE‐024 study (10.3 months), the lower limit of the 95% CI did not exceed the target (4.3 months). Thus, the primary end point was not met. The median OS was 21.6 (95% CI 15.1–not reached) months. The ORR was 43.4% (95% CI 25.6–63.2). The proportion of patients with treatment‐related adverse events of grade ≥3 was 15.4%, and the QOL did not worsen with treatment.

When we started this study, third‐generation cytotoxic chemotherapy was the standard treatment for elderly patients with NSCLC. 9 , 13 However, a randomized phase III trial showed that the OS of elderly patients (aged ≥75 years) with advanced nonsquamous NSCLC who received carboplatin plus pemetrexed followed by pemetrexed maintenance was noninferior to the OS of those who received the third‐generation chemotherapy agent, docetaxel monotherapy. In addition, the prevalence of grade 3 or 4 leukopenia and neutropenia, and febrile neutropenia was lower in the carboplatin‐pemetrexed group than in the docetaxel group. 14 In addition, a randomized phase III trial (the CAPITAL study) showed that the OS and PFS of elderly patients (aged ≥70 years) with advanced squamous NSCLC who received carboplatin plus nab‐paclitaxel was significantly superior to the OS and PFS of those who received docetaxel. 15 From these observations, carboplatin‐pemetrexed treatment followed by pemetrexed maintenance or carboplatin plus nab‐paclitaxel is considered to be the standard treatment for elderly patients with advanced nonsquamous or squamous NSCLC, respectively. Although the primary end point, PFS, was not met in this study, the median PFS (9.6 months) is longer than that of carboplatin and pemetrexed followed by pemetrexed (6.4 months) or carboplatin and nab‐paclitaxel (5.8 months). 14 Furthermore, the median OS (21.6 months) of this study is longer than that of carboplatin plus pemetrexed followed by pemetrexed maintenance (18.7 months) or the median OS in the CAPITAL study (16.9 months). 14 , 15 In addition, in a pooled analysis of elderly patients with advanced NSCLC (≥75 years) and a PD‐L1 TPS of ≥50%, pembrolizumab improved OS more than chemotherapy did. 16 From these observations, pembrolizumab monotherapy could be an effective treatment for these patients. However, to investigate whether pembrolizumab monotherapy or these platinum doublet chemotherapies is an optimal treatment for these patients, a randomized study of a large cohort is needed.

The response rate of this study is similar to that of a previous phase III study. 3 Patients who achieved CR or PR had a longer OS (Figure 3). This is consistent with the results of a previous study. 17 Within a few months, several patients in this study had progressive disease. The treatment for such patients should be changed promptly. Previous studies have shown that patients with early disease progression after administration of anti‐PD‐1/PD‐L1 antibodies had a higher tumor burden, 18 but we were unable to examine the tumor burden in our study. For such patients, cytotoxic chemotherapy or PD‐1/PD‐L1 antibodies plus chemotherapy may be more effective than PD‐1/PD‐L1 antibodies. In addition, the oncogenic driver subtype should be investigated, since treatment with PD‐1/PD‐L1 antibodies could be considered ineffective for patients with NSCLC who have not only EGFR mutation or ALK rearrangement, but also BRAF, HER2, or MET mutations or RET translocation. 19 , 20

The safety profile of pembrolizumab in this study was tolerable. In fact, the rate of grade ≥3 adverse events in this study (15.4%) was lower than that of the KEYNOTE‐024 study (26.6%). 3 However, a multicenter, retrospective study of 928 geriatric patients with various tumors (NSCLC, melanoma, genitourinary) treated with single‐agent ICIs also reported that the rate of grade ≥3 immune‐related events was 12.2%. 21 In addition, grade ≥3 adverse events in a pooled analysis of elderly patients with advanced NSCLC (≥75 years) treated with pembrolizumab was 24.2%, which is higher than that of our study. Furthermore, one patient developed grade 5 pneumonitis in our study. On the contrary, it is known that the frequency of cytopenia due to chemotherapy was high in elderly patients. In the study for elderly nonsquamous NSCLC patients, the rates of neutropenia, anemia, and febrile neutropenia of grade 3 and more were 46.2%, 29.5%, and 4.2%, respectively, in the carboplatin‐pemetrexed group. In addition, in the CAPITAL study, the rates of neutropenia and anemia of grade 3 and more were 63.2% and 38.9%, respectively. 14 We should pay attention to immune‐related adverse events. However, the safety of pembrolizumab monotherapy is considered to be superior to cytotoxic chemotherapy in elderly patients. The proportion of each adverse event did not differ between elderly and nonelderly patients, and no novel adverse event was observed in the pooled analysis. 16

There are several randomized phase III trials (the KEYNOTE‐409, KEYNOTE‐189, and IMpower‐150 studies) that compare platinum‐doublet chemotherapy plus PD‐1/PD‐L1 antibodies or placebo, followed by PD‐1/PD‐L1 antibodies or placebo in patients with NSCLC. 22 , 23 , 24 These studies showed that the primary endpoint, PFS, and OS were significantly longer in the PD‐1/PD‐L1 antibody‐combination group than in the placebo‐combination group, irrespective of the PD‐L1 expression level. Thus, platinum doublet chemotherapy plus PD‐1/PD‐L1 antibodies is also recommended as first‐line treatment. 5 Furthermore, ipilimumab, an antibody against CTL antigen 4 (CTLA‐4), is an available treatment for patients with advanced NSCLC. A randomized phase III trial (the CheckMate 227 study) involving patients with advanced NSCLC who had a PD‐L1 expression level of ≥1% showed that OS was significantly longer in the nivolumab plus ipilimumab group than in the chemotherapy group. 25 Another randomized phase III trial (the CheckMate 9LA study) showed that nivolumab plus ipilimumab with two cycles of chemotherapy provided a significantly longer OS than chemotherapy alone. 26 Based on these observations, these treatments with ipilimumab are also standard treatment options. 27 The efficacy of these treatments might be superior to that of pembrolizumab monotherapy for patients with NSCLC having a PD‐L1 TPS of ≥50%. However, these studies did not consider patients who were ≥75 years old. Moreover, in studies on platinum‐doublet chemotherapy plus PD‐1/PD‐L1 antibody or placebo, grade ≥3 adverse events were more frequent in the PD‐1/PD‐L1 antibody combination group than in the placebo group. Furthermore, a previous phase III study showed that there were more adverse events in the nivolumab plus ipilimumab group than in the nivolumab monotherapy group. Given these observations, pembrolizumab monotherapy is a possible treatment option for elderly patients with NSCLC.

In this study, the scores of EORTC QLQ‐C30 GHS/QOL, QLQ‐C30 functioning and symptom domains, and QLQ‐LC13 did not change significantly during treatment. These results suggested that pembrolizumab monotherapy did not decrease the QOL of elderly patients with NSCLC. Conversely, in the health‐related QOL results of the KEYNOTE‐024 study, the mean baseline‐to‐week‐15 QLQ‐C30 GHS/QOL was improved in the pembrolizumab group (6.9, 95% CI 3.3–10.6). In addition, patients who were treated with pembrolizumab had improved baseline‐to‐week 15 scores of the QLQ‐C30 functioning and symptom domains, and QLQ‐LC13. 28 These discrepancies were due to our study's small sample size, which limited the assessment of QOL change.

This study has a few limitations. First, this was a single‐arm phase II study with a small sample size. Second, an independent central review for response and/or progression was not conducted.

CONCLUSION

These findings show that pembrolizumab monotherapy would be tolerable for advanced elderly patients with NSCLC having a PD‐L1 TPS of ≥50%. However, the safety of pembrolizumab needs to be confirmed in a larger prospective study. The primary endpoint, the median PFS, did not achieve the expected value. However, the PFS was slightly shorter than that of the KEYNOTE‐024 study. The results of our study and a pooled analysis 16 suggest that pembrolizumab monotherapy is an effective treatment for these patients. A multicenter study of a large cohort in the future is needed to compare the efficacy of pembrolizumab monotherapy to that of carboplatin plus pemetrexed or nab‐paclitaxel in these patients.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

T.M. received honoraria from ONO Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd and Chugai Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. K.F. received honoraria from ONO Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, Chugai Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, MSD K.K., and Bristol‐Myers Squibb. T.S. and R.N. received honoraria from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co. K.H., N.I. and M.Y. received honoraria from ONO Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, Chugai Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, and MSD K.K. S.S. received honoraria from ONO Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. N. Hattori received scholarship endowment from MSD K.K. and Chugai Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, funding from ONO Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, and honoraria from ONO Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, Chugai Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, MSD K.K., and Bristol‐Myers Squibb.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the patients, their families, and the participating investigators. In addition, we thank Kenichi Yoshimura (Future Medical Center, Hiroshima University Hospital, Hiroshima 734‐8551, Japan) for statistical analysis and Akiko Miyake (Department of Molecular and Internal Medicine, Graduate School of Biomedical & Health Sciences, Hiroshima University, Hiroshima, Japan) for supporting us in this study. We thank Jyunya Inada (Department of Respiratory Medicine, JR Hiroshima Hospital) and Yojiro Ohnari (Department of Respiratory Medicine, Mazda Hospital) from the Safety Monitoring Committee. We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Masuda T, Fujitaka K, Suzuki T, Hamai K, Matsumoto N, Matsumura M, et al. Phase 2 study of first‐line pembrolizumab monotherapy in elderly patients with non‐small‐cell lung cancer expressing high PD‐L1 . Thorac Cancer. 2022;13(11):1611–1618. 10.1111/1759-7714.14428

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data archiving is not mandated but data will be made available on reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:7–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chen VW, Ruiz BA, Hsieh MC, Wu XC, Ries LAG, Lewis DR. Analysis of stage and clinical/prognostic factors for lung cancer from SEER registries: AJCC staging and collaborative stage data collection system. Cancer. 2014;120(Suppl 23):3781–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Reck M, Rodriguez‐Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD‐L1‐positive non‐small‐cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1823–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Reck M, Rodríguez‐Abreu D, Robinson AG, Hui R, Csőszi T, Fülöp A, et al. Five‐year outcomes with pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for metastatic non‐small‐cell lung cancer with PD‐L1 tumor proportion score ≥ 50. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:2339–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Akamatsu H, Ninomiya K, Kenmotsu H, Morise M, Daga H, Goto Y, et al. The Japanese lung cancer society guideline for non‐small cell lung cancer, stage IV. Int J Clin Oncol. 2019;24:731–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sato A, Matsubayashi K, Morishima T, Nakata K, Kawakami K, Miyashiro I. Increasing trends in the prevalence of prior cancer in newly diagnosed lung, stomach, colorectal, breast, cervical, and corpus uterine cancer patients: a population‐based study. BMC Cancer. 2021;21:264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Grossi F, Crino L, Logroscino A, et al. Use of nivolumab in elderly patients with advanced squamous non‐small‐cell lung cancer: results from the Italian cohort of an expanded access programme. Eur J Cancer. 2018;100:126–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Quoix E, Zalcman G, Oster JP, Westeel V, Pichon E, Lavolé A, et al. Carboplatin and weekly paclitaxel doublet chemotherapy compared with monotherapy in elderly patients with advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer: IFCT‐0501 randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2011;378:1079–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kudoh S, Takeda K, Nakagawa K, Takada M, Katakami N, Matsui K, et al. Phase III study of docetaxel compared with vinorelbine in elderly patients with advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer: results of the West Japan thoracic oncology group trial (WJTOG 9904). J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3657–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Masuda T, Fujitaka K, Ishikawa N, Nakano K, Yamasaki M, Kitaguchi S, et al. Treatment rationale and design of the PROLONG study: safety and efficacy of pembrolizumab as first‐line therapy for elderly patients with non‐small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Dis. 2020;12:1079–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Common terminology criteria for adverse events: (CTCAE), v4.03. ed. Bethesda, MD. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gridelli C, Perrone F, Gallo C, Cigolari S, Rossi A, Piantedosi F, et al. Chemotherapy for elderly patients with advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer: the multicenter Italian lung cancer in the elderly study (MILES) phase III randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:362–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Okamoto I, Nokihara H, Nomura S, Niho S, Sugawara S, Horinouchi H, et al. Comparison of carboplatin plus pemetrexed followed by maintenance pemetrexed with docetaxel monotherapy in elderly patients with advanced nonsquamous non‐small cell lung cancer: a phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:e196828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hamamoto Y, Kogure Y, Kada A, et al. A randomized phase III study comparing carboplatin with nab‐paclitaxel versus docetaxel for elderly patients with squamous‐cell lung cancer: Capital study. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:9031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nosaki K, Saka H, Hosomi Y, Baas P, de Castro G Jr, Reck M, et al. Safety and efficacy of pembrolizumab monotherapy in elderly patients with PD‐L1‐positive advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer: pooled analysis from the KEYNOTE‐010, KEYNOTE‐024, and KEYNOTE‐042 studies. Lung Cancer. 2019;135:188–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Satouchi M, Nosaki K, Takahashi T, Nakagawa K, Aoe K, Kurata T, et al. First‐line pembrolizumab vs chemotherapy in metastatic non‐small‐cell lung cancer: KEYNOTE‐024 Japan subset. Cancer Sci. 2020;111:4480–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 18. Miyawaki T, Kenmotsu H, Mori K, Miyawaki E, Mamesaya N, Kawamura T, et al. Association between clinical tumor burden and efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitor monotherapy for advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2020;21:e405–e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bylicki O, Paleiron N, Margery J, Guisier F, Vergnenegre A, Robinet G, et al. Targeting the PD‐1/PD‐L1 immune checkpoint in EGFR‐mutated or ALK‐translocated non‐small‐cell lung cancer. Target Oncol. 2017;12:563–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Guisier F, Dubos‐Arvis C, Viñas F, Doubre H, Ricordel C, Ropert S, et al. Efficacy and safety of anti‐PD‐1 immunotherapy in patients with advanced NSCLC with BRAF, HER2, or MET mutations or RET translocation: GFPC 01‐2018. J Thorac Oncol. 2020;15:628–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nebhan CA, Cortellini A, Ma W, Ganta T, Song H, Ye F, et al. Clinical outcomes and toxic effects of single‐agent immune checkpoint inhibitors among patients aged 80 years or older with cancer: a multicenter international cohort study. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7:1856–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gandhi L, Rodriguez‐Abreu D, Gadgeel S, et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in metastatic non‐small‐cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2078–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Paz‐Ares L, Luft A, Vicente D, Tafreshi A, Gümüş M, Mazières J, et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy for squamous non‐small‐cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2040–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Socinski MA, Jotte RM, Cappuzzo F, Orlandi F, Stroyakovskiy D, Nogami N, et al. Atezolizumab for first‐line treatment of metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2288–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hellmann MD, Paz‐Ares L, Bernabe Caro R, Zurawski B, Kim SW, Carcereny Costa E, et al. Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab in advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2020–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Paz‐Ares L, Ciuleanu TE, Cobo M, Schenker M, Zurawski B, Menezes J, et al. First‐line nivolumab plus ipilimumab combined with two cycles of chemotherapy in patients with non‐small‐cell lung cancer (CheckMate 9LA): an international, randomised, open‐label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:198–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Netwook NCC . NCCN clinical practice guideline in oncology Non‐small cell lung cancer. Version 4. 2021, March 3 2021 https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nscl.pdf. Accessed June, 8 2021.

- 28. Brahmer JR, Rodríguez‐Abreu D, Robinson AG, Hui R, Csőszi T, Fülöp A, et al. Health‐related quality‐of‐life results for pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy in advanced, PD‐L1‐positive NSCLC (KEYNOTE‐024): a multicentre, international, randomised, open‐label phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:1600–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data archiving is not mandated but data will be made available on reasonable request.