Abstract

Alzheimer disease (AD) is the most dominant form of dementia characterized by the deposition of extracellular amyloid plaques and intracellular neurofibrillary tau tangles (NFTs). In addition to these pathologies, an emerging pathophysiological mechanism that influences AD is neuroinflammation. Astrocytes are a vital type of glial cell that contribute to neuroinflammation and reactive astrocytes, or astrogliosis, are a well-known pathological feature of AD. However, the mechanisms by which astrocytes contribute to the neurodegenerative process in AD have not been fully elucidated. Here we showed that astrocytic α2-Na+/K+ ATPase (α2-NKA) is elevated in postmortem human brain tissue from AD and progressive nuclear palsy, a primary tauopathy. The increased astrocytic α2-NKA was also recapitulated in a mouse model of tauopathy. Pharmacological inhibition of the α2-NKA robustly suppressed neuroinflammation, and neurodegeneration, and reduced brain atrophy. In addition, α2-NKA knockdown in tauopathy mice halted the accumulation of tau pathology. We also demonstrated that α2-NKA promoted tauopathy in part by regulating the pro-inflammatory protein lipocalin-2 (Lcn2). Overexpression of Lcn2 in tauopathy mice increased tau pathology and prolonged Lcn2 exposure to primary neurons promoted tau uptake in vitro. These studies collectively highlight the contribution of reactive astrocytes to tau-pathogenesis in mice and define α2-NKA as a major regulator of astrocytic-dependent neuroinflammation.

One-sentence Summary:

Astrocytic α2-Na+/K+ ATPase inhibition and knockdown in a model of tauopathy protects against neurodegeneration by attenuating astrocytic reactivity.

Introduction

Tauopathies are a group of diverse neurodegenerative disease that include Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the most dominant form of dementia. The defining neuropathological features of AD include extracellular amyloid plaques and the intracellular neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs). The primary component of amyloid plaques is the accumulation of aggregated non-fibrillar, fibrillar, or oligomeric amyloid-β (Aβ) peptide. The NFTs are mainly composed of aggregated hyperphosphorylated tau that ultrastructurally appears as paired helical filaments (PHF)(1, 2). Although there is much clarity needed before fully understanding the relationship between Aβ and tau, it appears Aβ pathophysiological effects occur early in AD development, which seems necessary but not sufficient for priming vulnerable brain regions for the intrusion of tau pathology (reviewed in (3, 4). Additionally, the recent advances in basic research, genetics, and biomarkers are demonstrating that AD is a multifaceted degenerative process with several potential pathophysiological mechanisms occurring both downstream and in parallel with Aβ and tau pathology that are important in mediating neurodegeneration. An emerging pathophysiological mechanism influencing AD development is activation of the resident glial cells, predominantly astrocytes and microglia, which are responsible for modulating brain inflammation resulting in elevated amounts of pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, secondary messengers, and reactive oxygen species in the brain (5, 6). These pro-inflammatory molecules correlate with disease pathology, including the amount of NFTs in AD and related tauopathies. Whereas microglia have been extensively studied in the context of AD-related glia activation, the role of astrocytes remains to be fully explored.

Astrocytes are one of the most abundant cell type in the CNS and play a critical role in diverse functions, including metabolic support of neurons, calcium signaling essential for synaptic transmission, and modulation of bran inflammation (7–11). Reactive astrocytes, or astrogliosis, are a well-known feature of neurodegeneration and are commonly classified by an increase in glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), hypertrophy of the cell body, and increased secretion of inflammatory factors (6, 12). In AD, reactive astrogliosis develops early in the disease and is positively associated with the density of NFTs and neuronal cell death (5, 13–15). Moreover, reactive astrocytes co-localize with amyloid β (Aβ) plaques in postmortem brain tissue and can contain Aβ intracellularly (5, 15). Previous studies in mouse models of amyloidosis have shown that astrocytes regulate major inflammatory pathways. Reducing astrocyte activation by inhibiting the calcineurin (CN)-Nuclear Factor of Activation T cells (NFAT) signaling pathways that regulate cytokine production, lowered amyloid burden in a mouse model of amyloidosis (16). In addition, the exposure of Aβ fibrils to astrocytes has been shown to activate the key immune regulator Nuclear Factor ƙB (NFƙB) that in turn mediated the release of complement protein C3, a neurotoxic molecule (17). Both the activation of NFƙB and C3 protein are associated with AD development and the inhibition of C3 in a mouse model of amyloidosis and tauopathy reduced synapse loss and rescued cognitive impairments (17–20). However, the role of astrocytes in tau pathogenesis and their contribution to tau-dependent neurodegeneration remains largely unknown.

In previous studies, we identified an enrichment of α2-Na+/K+ ATPase (α2-NKA), an astrocyte-specific isoform of the Na+/K+ ATPase transmembrane ionic pump, in the spinal cord of sporadic and familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) human brain samples and a mouse model of familial ALS expressing mutant human SOD1. A component of motor neuron degeneration in human SOD1 transgenic mice is a gain-of-toxicity in astrocytes and we demonstrated that the α2-NKA is a key regulator of this neurotoxicity (21). In the present study. we found that escalated amounts of α2-NKA correlated with an increase of reactive astrocytes in both AD human brain samples and the PS19 tauopathy mouse model (tau-tg) (22). The conserved enrichment in AD samples suggests that the elevated expression of the α2-NKA previously identified in ALS astrocytes are not due to an ALS-specific gain-of-toxicity but rather a shared mechanism for astrocytic-dependent reactivity that potentially contributes to neurodegeneration and spans across diseases. We found that the pharmacological inhibition and short hairpin RNAi (shRNA) mediated knockdown of α2-NKA significantly reduced tauopathy in aged tau-tg mice. Importantly, we found that α2-NKA inhibition reduced markers of glia reactivity as well as chemokine and cytokine production. Collectively, these data reveal that α2-NKA inhibition or knockdown results in robust attenuation of astrogliosis, thereby potentially protecting against tau-associated pathologies.

Results

α2-NKA is Elevated in Human Tauopathies and in a Mouse Model of Tauopathy

We first evaluated whether the expression of the ATP1A2 gene encoding the α2-NKA was differentially expressed in brains from autopsy-confirmed AD cases compared with neuropathology-free controls. We examined previously generated gene expression profiles from 76 control and 80 AD brains and found a significant increase in ATP1A2 expression in the temporal cortex of patients with AD (P-value 1.97E-07) (table s1). To determine whether tau pathology was sufficient to cause this change in ATP1A2 gene expression, we also analyzed ATP1A2 in 82 brains from patients with the primary tauopathy, progressive nuclear palsy (PSP), revealing a significant increase of the ATP1A2 expression (P-value 7.89E-03) (table s1). We further validate α2-NKA elevation at the protein level in AD confirmed human samples by immunoblotting analysis, which revealed an increase in the α2-NKA and GFAP not evident in age-matched control subjects (α2-NKA P-value 0.0337 and GFAP P-value 0.0013) (Fig.1A, B). From these results, we surmise that the elevated amounts of the α2-NKA previously observed in ALS human samples also occur in AD.

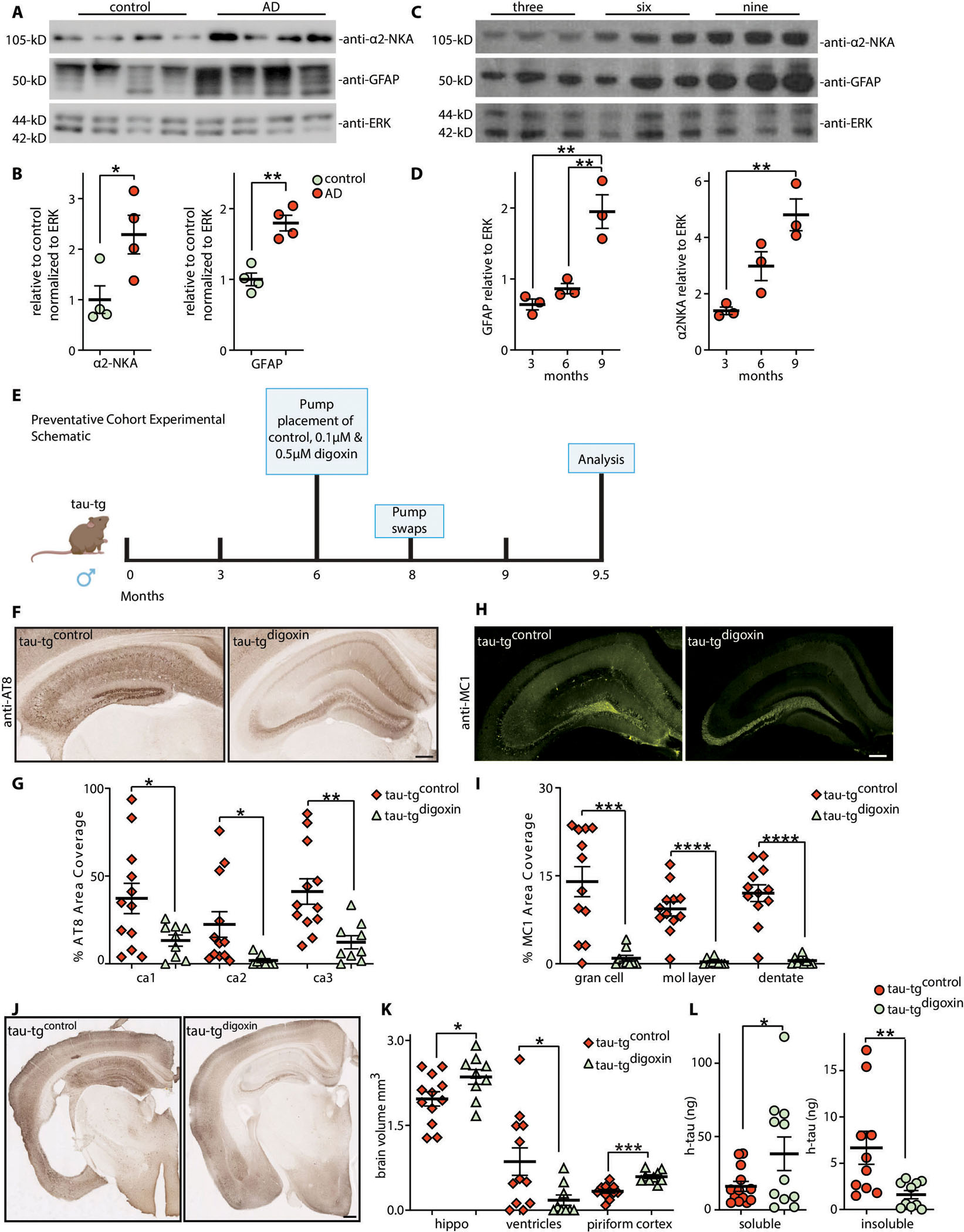

Fig. 1. Human tauopathies and tau-tg mice display elevated α2-NKA and inhibition with digoxin prior to overt pathology prevents tau pathology in tau-tg mice.

(A) Immunoblots of α2-NKA and GFAP relative to ERK protein from patients with confirmed AD and aged matched controls (n=4 per group) quantified in (B). (C) Immunoblot analysis of α2-NKA and GFAP in 3, 6, and 9-month diseased tau-tg mice (n=3 per group) relative to ERK protein quantified in (D). (E) Experimental schematic and timeline of digoxin infusion in preventative cohort. (F) Representative hippocampal brain sections for AT8 phosphorylated pathological tau protein in tau-tgcontrol mice (left panel) and tau-tgdigoxin mice (right panel) quantified by percent area coverage in G (n=9–12 per group). Scale bar, 200 μm. (H) Representative hippocampal brain sections for MC1 aggregated pathological tau protein in tau-tgcontrol mice (left panel) and tau-tgdigoxin mice (right panel) quantified by percent area coverage in I (n=9–12 per group). Scale bar, 200 μm. (J) Representative image of brain atrophy in tau-tgcontrol mice (left panel) and tau-tgdigoxin mice (right panel). Scale bar, 400μm. (K) Quantification of hippocampal (hippo) volume, ventricular size, and piriform cortex area in tau-tgdigoxin mice relative to tau-tgcontrol mice (n=9–12 per group). (L) Sarkosyl insoluble purification of tau protein in tau-tgdigoxin mice relative to tau-tgcontrol mice measured by ELISA (n=9–12 per group). Significance determined by unpaired, two-tailed student t-test. Error bars represent ±s.e.m. *p<0.5, **<0.01; ***p<0.001.

To investigate the potential role for the astrocytic α2-NKA in tau pathology, we next assessed α2-NKA in tau-tg mice. Tau-tg mice display an age-dependent increase of tau pathology, brain atrophy, and glia reactivity that are characteristic of tauopathy progression in human disease. Immunoblot analysis of the α2-NKA and GFAP protein in 3-, 6-, and 9- month old tau-tg mice revealed an age-dependent increase in both the α2-NKA and GFAP protein (α2-NKA 3 months vs 9 months P-value 0.0050, GFAP 3 months vs 9 months P-values 0.0024 and GFAP 6 months vs 9 months P-value 0.0064) (Fig. 1C, D). In an additional analysis, a cohort of 9.5 month (end-stage disease) old tau-tg mice revealed an increase in both α2-NKA and GFAP relative to aged matched non-transgenic (non-tg) littermates (α2-NKA P-value 0.0085 and GFAP P-value 0.0041) (fig. s1A, B). Moreover, histopathological characterization of tau-tg mice at 3, 6, 8, 9 months confirmed an age-dependent increase in astrogliosis, labeled with GFAP, that correlated with an increase in pathological tau, labeled with an antibody detecting paired helical filament tau (AT8) (AT8 3 months vs 9 months P-values 0.0004, AT8 6 months vs 9 months P-value 0.0007, AT8 8 months vs 9 months P-value 0.0217, GFAP 3 months vs 9 months P-value 0.0002, GFAP 6 months vs 9 months P-value 0.0009, GFAP 8 months vs 9 months P-value 0.0249) (fig. s1C–F) (1). This initial characterization confirms that the increase of α2-NKA in astrocytes correspond with increased astrogliosis and tauopathy in both a model of tauopathy and human disease.

α2-NKA Inhibition with Digoxin Prior to Disease Onset in a Mouse Model of Tauopathy Prevents Tau-Pathogenesis and Brain Atrophy

The elevated amount of α2-NKA in human tauopathies and in tau-tg mice that coincide with increased astrogliosis suggest the α2-NKA may be regulating astrocytic-dependent reactivity that could be influencing tau-associated pathologies. We hypothesized that inhibiting the α2-NKA would attenuate astrogliosis in tau-tg mice, thereby protecting against tau pathogenesis. To determine the impact of inhibiting the α2-NKA, we first took a pharmacological approach by infusion of the cardiac glycoside digoxin, a selective inhibitor of Na+/K+ ATPases which displays a higher affinity for the α2-NKA isoform at specific concentrations (21, 23–25). Our initial characterization of the tau-tg mice revealed two distinct time points prior to overt tau pathology and chronic astrogliosis (~6-months, early disease) and after overt tau pathology and chronic astrogliosis (~8-months, mid-disease) (fig. s1C–F). We first aimed to model preventative action against disease progression by pharmacological inhibition of the α2-NKA prior to chronic astrogliosis and overt tau pathology in a cohort of mice (preventative cohort) (Fig. 1E). Therefore, we delivered two dosages of digoxin (0.1 and 0.5 μM) or control vehicle into the ventricles of 6-month-old tau-tg mice by surgically implanted subcutaneous osmotic mini pumps. Following three months of digoxin infusion, we assessed the effects of inhibiting the α2-NKA on tau pathology at disease end-stage, corresponding to 9.5-months of age. Histopathological analysis with AT8 revealed a significant decrease in the accumulation of pathological tau in hippocampal sub-regions following the infusion of 0.1 μM digoxin relative to the control vehicle (tau-tgcontrol) (ca1 P-value 0.0405, ca2 P-value 0.0432) (fig. s2A,B). Moreover, histopathological analysis with AT8 revealed a greater significant neuroprotective effect in preventing the accumulation of pathological tau following the infusion of 0.5 μM digoxin (tau-tgdigoxin) compared to tau-tgcontrol mice (ca1 P-value 0.0320, ca2 P-value 0.0356, ca3 P-value 0.0046) (Fig. 1F, G). To further elucidate the effect of α2-NKA inhibition on different forms of tauopathy, histopathological analysis with MC1, an antibody that targets an abnormal conformational form of tau that is present in AD- and is one of the earliest detectable changes in tau in the AD and other tauopathies, demonstrates a significant decrease of MC1 positive tau in hippocampal subregions in tau-tgdigoxin mice compared to tau-tgcontrol mice (gran cell P-value 0.0004, mol layer P-value <0.0001, dentate P-value <0.0001) (Fig. 1H, I).

In addition, tau-tg mice exhibit brain atrophy at the degenerative stage, displaying a decrease of hippocampal volume, an increase of ventricular volume, and a thinning of the piriform cortex (26). Correlating with a decrease in tau pathology, which displays a stronger neuroprotective effect against tau pathology, volumetric analysis of the tau-tgdigoxin mice revealed significant protection against brain atrophy of the hippocampus, ventricles, and piriform cortex relative to tau-tgcontrol mice (hippo P-value 0.0189, ventricles P-value 0.0124, piriform cortex P-value<0.0001) (Fig. 1J, K). We also assessed sarkosyl-insoluble tau protein, as abnormal pathological tau is predominately insoluble in the ionic detergent sarkosyl (27). Following the sarkosyl purification of human tau (h-tau) protein, ELISA-based measurements revealed a significant increase of soluble h-tau and a significant decrease of insoluble h-tau protein in the tau-tgdigoxin mice relative to tau-tgcontrol mice (soluble P-value 0.0290, insoluble P-value 0.0129) (Fig. 1L). These results are consistent with our histopathological analysis that exhibited a significant decrease in pathological AT8 and MC1 positive tau in tau-tgdigoxin mice. Collectively, these data demonstrate that the inhibition of the α2-NKA prior to chronic astrogliosis and overt pathology substantially prevented several forms of pathological tau and protected against brain atrophy.

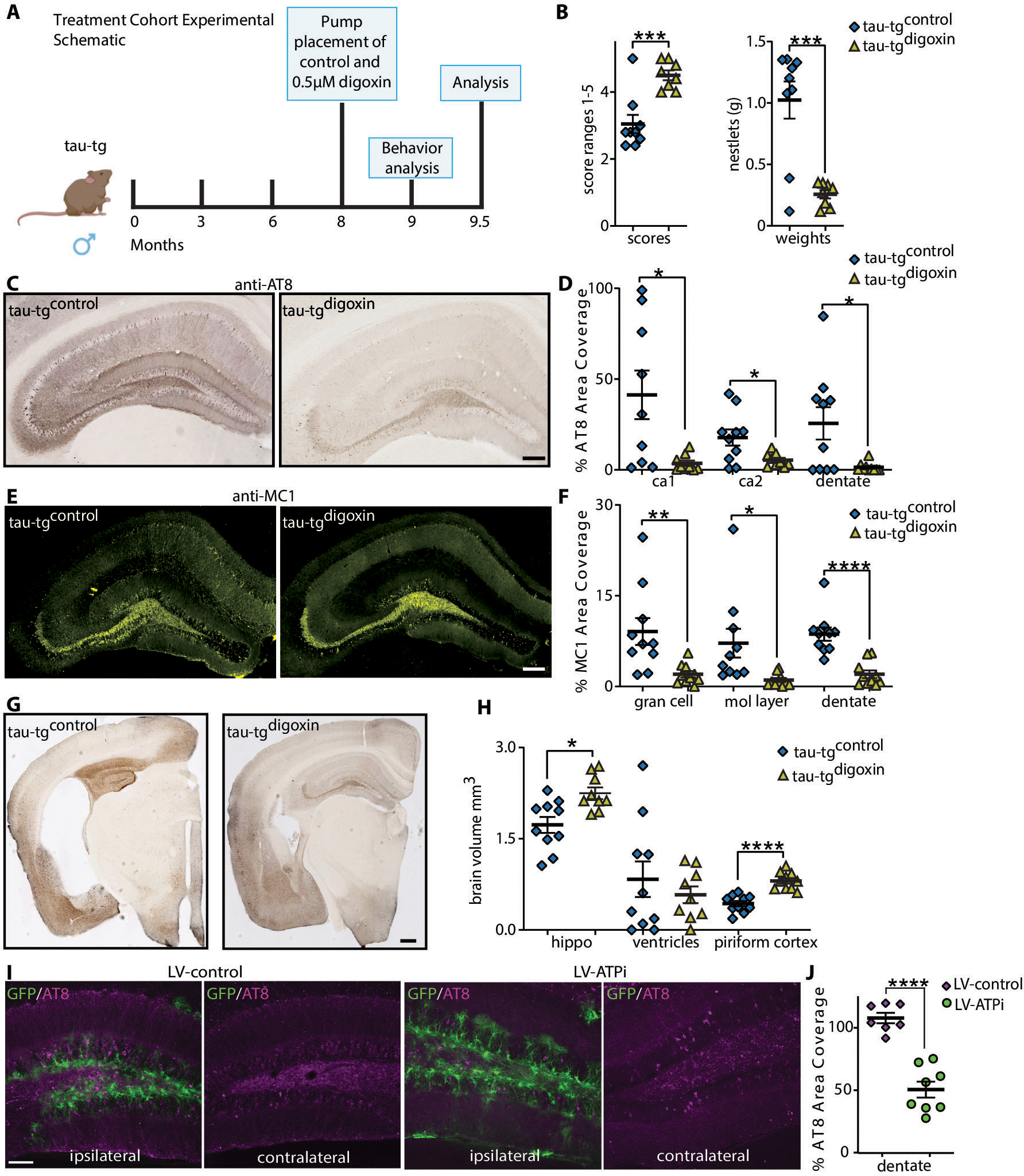

α2-NKA Inhibition or Knockdown after Disease Onset Halts Tau-pathogenesis and Brain Atrophy in a Tauopathy Mouse Model

In the preventative paradigm cohort, we have demonstrated that pharmacological inhibition of the α2-NKA prior to chronic astrogliosis and overt tauopathy prevents the accumulation of tau pathology and protects against brain atrophy (Fig. 1). However, AD and tauopathies are progressive neurodegenerative diseases, where pathology and degeneration accompanied by chronic neuroinflammation occur over years and are often diagnosed after disease onset (28). To model whether this inhibition would yield neuroprotective effects after chronic astrogliosis and diffuse tau pathology, in a second cohort of mice we infused 0.5 μM digoxin or the control vehicle into 8-month-old tau-tg mice (treatment cohort) (Fig. 2A). At this disease stage, tau-tg mice display tauopathy and the initial neuroinflammatory response has progressed to a more sustained state (fig. s1 C–E). Given the robust protection against tauopathy in the preventative cohort, we first evaluated if digoxin infusion would prevent the impaired nesting behavior of aged tau-tg mice. We utilized published criteria to assess behavior impairment in nesting, four weeks after infusion of digoxin in tau-tg mice (29–32).The nest quality was first scored on a scale of 1–5, then measured for the amount of untorn nestlets by weight. This analysis revealed tau-tgdigoxin mice have significantly improved nest scores as well as a decrease in the amount of untorn nestlet weight relative to tau-tgcontrol mice, providing evidence of improved behavior in tau-tgdigoxin mice (scores P-value 0.0004 and weights P-value 0.0003) (Fig. 2B). Following six weeks of infusion, we next evaluated if inhibition with digoxin infusion would delay accumulation of tauopathy in this treatment cohort. Consistent with our preventative cohort and behavioral improvement, histopathological analysis with AT8 and MC1 revealed a significant decrease in tauopathy in this treatment cohort in hippocampal sub-regions in tau-tgdigoxin mice relative to tau-tgcontrol mice (AT8 ca1 P-value 0.0150, AT8 ca2 P-value 0.0206, AT8 dentate P-value 0.0142, MC1 gran cell P-value 0.0062, MC1 mol layer P-value 0.0203, MC1 dentate P-value <0.0001) (Fig. 2C–F). In addition, brain volume is preserved in the tau-tgdigoxin mice following the treatment at this time point, leading to a significant increase in the hippocampus and piriform cortex volume with a trending decrease in ventricular atrophy relative to tau-tgcontrol mice (hippo P-value 0.0060 and piriform cortex P-value <0.0001) (Fig. 2G,H).

Fig. 2. The inhibition or selective knockdown of α2-NKA after disease onset attenuates neuroinflammation and halts tau pathogenesis in tau-tg mice.

(A) Experimental schematic and timeline of digoxin infusion in treatment cohort. (B) Nesting activity of tau-tgdigoxin and tau-tgcontrol assessed using a published scoring criteria to assess the quality of nest construction and amount of torn nestlet (n=8–9). (C) Representative hippocampal brain sections for AT8 phosphorylated pathological tau protein in tau-tgcontrol mice (left panel) and tau-tgdigoxin mice (right panel), quantified by percent area coverage in D (n=9–10 per group). Scale bar, 200μm. (E) Representative hippocampal brain sections for MC1 aggregated pathological tau protein in tau-tgcontrol mice (left panel) and tau-tgdigoxin mice (right panel), quantified by percent area coverage in F (n=9–10 per group). Scale bar, 200μm. (G) Representative image of brain atrophy in tau-tgcontrol mice (left panel) and tau-tgdigoxin mice (right panel) Scale bar, 400μm. (H) Quantification of hippocampal (hippo), ventricular size, and piriform cortex volume in tau-tgdigoxin mice relative to tau-tgcontrol mice (n=9–10 per group). (I) Representative hippocampal sections of tau-tg mice unilaterally injected into dentate gyrus with a lentivirus encoding GFP under a GFAP promoter and shRNA targeting the knockdown of the α2-NKA (LV-ATPi, green) and the corresponding control lentivirus (LV-control, green). Scale bar. 100μm. (J) Quantification of percent area covered of pathological phosphorylated tau (AT8) of control LV-control injected relative to LV-ATPi (n=7–8 per group). Significance determined by unpaired, two-tailed student t-test. Error bars represent ±s.e.m. *p<0.5, ***p<0.001, ****p p<0.0001.

To ensure these neuroprotective effects were mediated by targeting astrocytic α2-NKA, we next unilaterally injected into the hippocampus dentate gyrus lentivirus encoding both GFP driven by a GFAP promoter and shRNAs for the selective knockdown of the α2-NKA (LV-ATPi) or the corresponding control lentivirus (LV-control) after disease onset (21, 33). Efficacy for the knockdown of α2-NKA with LV-ATPi in vivo was evaluated with immunofluorescence (IF) analysis, revealing a significant decrease in α2-NKA signal that co-localized with GFP positive astrocytes in LV-ATPi tau-tg mice but not with GFP positive astrocytes in LV-control mice (P-value <0.0001) (fig. s3A–C). The knockdown of α2-NKA led to a significant decrease in the accumulation of tau pathology in the LV-ATPi injected dentate gyrus relative to the LV-control injected dentate gyrus at the degenerative stage (P-value <0.0001) (Fig. 2I, J). These experiments collectively demonstrate that pharmacological inhibition with digoxin or selective knockdown with shRNAs of the α2-NKA after overt tau pathology halts disease progression in tau-tg mice and preserves brain volume.

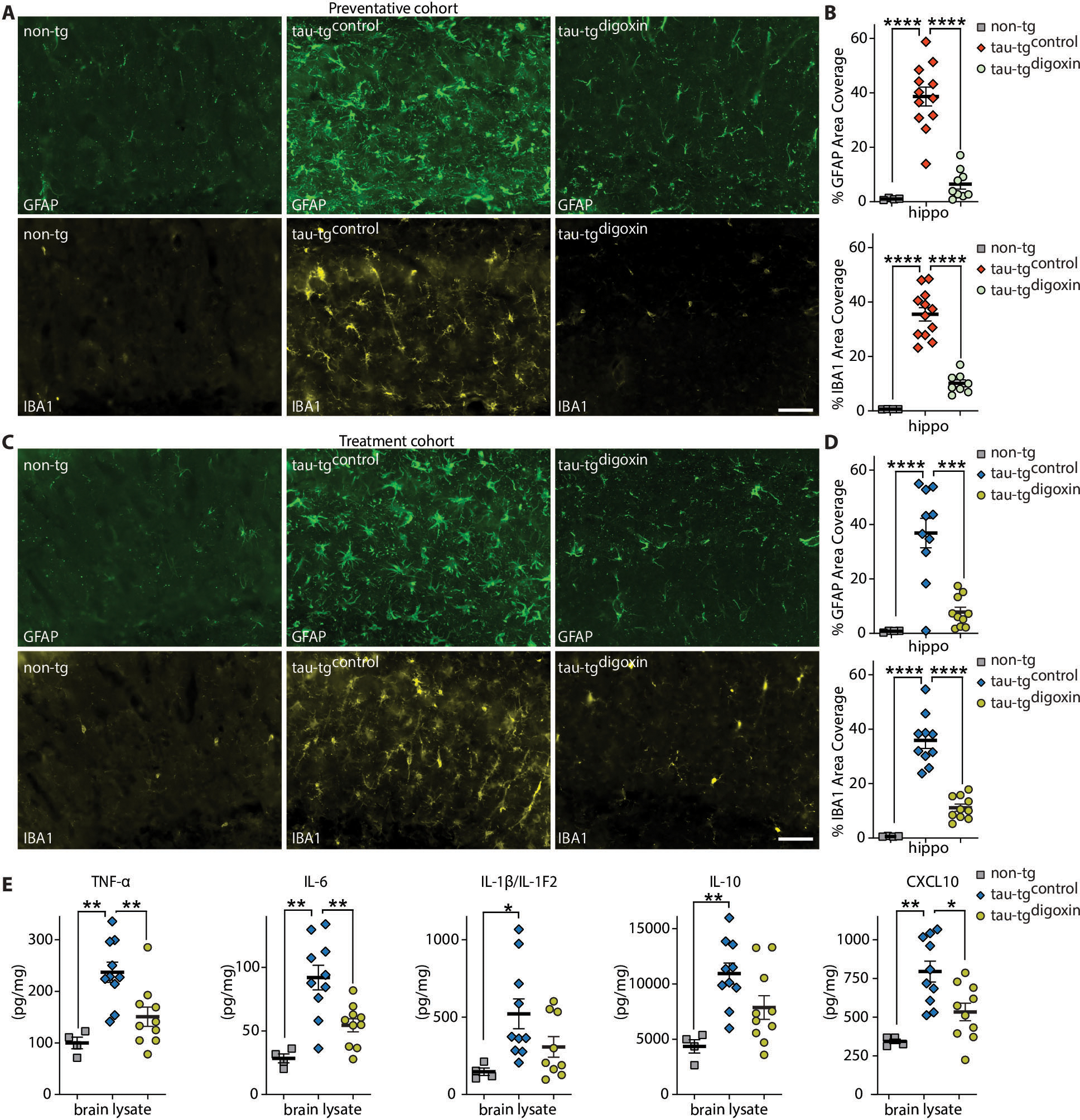

α2-NKA Inhibition with Digoxin Exerts Anti-inflammatory Effects, Neutralizing Pro-Inflammatory Cytokine and Chemokine Secretion in a Tauopathy Mouse Model

To ensure digoxin infusion targeted elevated amounts of α2-NKA present in aged tau-tg mice, we infused digoxin and control vehicle in 6- and 8-month-old non-tg control littermates and aged them to 9.5 months for assessment, revealing no effect in GFAP or microgliosis marker ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1 (IBA1) (fig. s4A–D). Next, to validate that digoxin infusion prevents tau pathology by attenuating astrogliosis, we subjected our preventative cohort of tau-tg mice as well as sham non-tg control mice to quantitative IF analysis of GFAP. We found significant chronic astrogliosis in tau-tgcontrol mice relative to non-tg (P-value <0.0001) (Fig. 3A,B). Digoxin inhibition of the α2-NKA in tau-tgdigoxin mice significantly prevented the chronic state of astrogliosis evident in tau-tgcontrol mice (P-value <0.0001) (Fig. 3A,B). Additionally, to examine the effects of attenuating astrogliosis on microglia reactivity, we preformed quantitative IF analysis with IBA1revealing an increase in tau-tgcontrol mice relative to non-tg that is significantly reduced in tau-tgdigoxin mice (P-value <0.0001 and P-value <0.0001) (Fig. 3A,B). Further analysis for GFAP and IBA1 in the treatment cohort of tau-tg mice after disease onset and chronic astrocyte reactivity revealed that the chronic astrogliosis and microgliosis evident in tau-tgcontrol mice relative to non-tg is significantly suppressed in this treatment cohort of tau-tgdigoxin mice (astrogliosis P-value <0.0001 and microgliosis P-value <0.0001)(Fig. 3C,D). These analyses demonstrate that digoxin infusion suppresses elevated astrogliosis and microgliosis present in tau-tg mice when administered before and after chronic glia activation, thereby likely preventing the progression of tau-associated pathology.

Fig. 3. Inhibition of the α2-NKA in preventative and treatment cohort suppresses neuroinflammation.

(A) Representative immunostaining of hippocampus in the preventative cohort for astrogliosis marker GFAP (green) and microgliosis marker IBA1 (gold) in aged, matched sham non-tg (left panel), tau-tgcontrol (middle panel), and tau-tgdigoxin (right panel). Scale bars 50μm. (B) Analysis for percent area covered of GFAP (top) and IBA1 (bottom) in the hippocampus of sham non-tg mice, tau-tgcontrol mice, and tau-tgdigoxin mice (n=4–12). (C) Representative immunostaining of hippocampus in treatment cohort with GFAP (green) and IBA1 (gold) in non-tg mice (left panel), tau-tgcontrol (middle panel), and tau-tgdigoxin (right panel). Scale bars 50μm. (D) Analysis for percent area covered of GFAP (top) and IBA1 (bottom) of the hippocampus normalized to sham non-tg mice (n=4–10). (E) Assessment of chemokines and cytokines TNFα, IL-6, IL-1β/IL-1F2, IL-10, and CXCL10 in treatment cohort (n=4–10 per group). Significance determined by one-way ANOVA and Bonferonni post hoc test for both the preventative and treatment cohort and chemokines/cytokines. Error bars represent ±s.e.m. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001

In order to effectively evaluate the effects of α2-NKA inhibition on suppressing neuroinflammation after disease onset, we next analyzed the amount of major chemokines/cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα), interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-1β (IL-1β/IL-1F2), interleukin 10 (IL-10), and CXCL10 by ELISA in sham non-tg, tau-tgcontrol mice, and tau-tgdigoxin mice. These chemokines and cytokines are well-known constituents of the inflammatory milieu present in neurodegeneration that perpetuate both astrocytic and microglial reactivity, resulting in neuronal injury and increased pathology in disease-dependent inflammatory conditions (34, 35). Our ELISA analysis revealed that TNFα, IL-6, and CXCL10 were significantly elevated in tau-tgcontrol mice compared to non-tg and these factors were significantly reduced in the tau-tgdigoxin mice (non-tg vs tau-tgcontrol TNFα P-value 0.0014, non-tg vs tau-tgcontrol IL-6 P-value 0.0003, non-tg vs tau-tgcontrol CXCL10 P-value 0.012 and tau-tgcontrol vs tau-tgdigoxin TNFα P-value 0.0072, tau-tgcontrol vs tau-tgdigoxin IL-6 P-value 0.0039, tau-tgcontrol vs tau-tgdigoxin CXCL10 P-value 0.0118) (Fig. 3E). In addition, there was a significant increase in IL-1β/IL-1F2 and IL-10 in in tau-tgcontrol mice relative to non-tg mice which exhibited a decrease in tau-tgdigoxin mice (IL-1β/IL-1F2 P-value 0.0486, and IL-10 P-value 0.0036)(Fig. 3E). Collectively, our evidence for the suppression of astrogliosis and microgliosis and the robust decrease of neuroinflammatory chemokines and cytokines further substantiates our conclusion that inhibition of α2-NKA attenuates a key inflammatory pathway in astrocytic-dependent reactivity.

Inhibition of α2-NKA Neutralized the Expression of the Neurotoxic Protein LCN2 and Overexpressing Lcn2 Increases Tauopathy in vivo

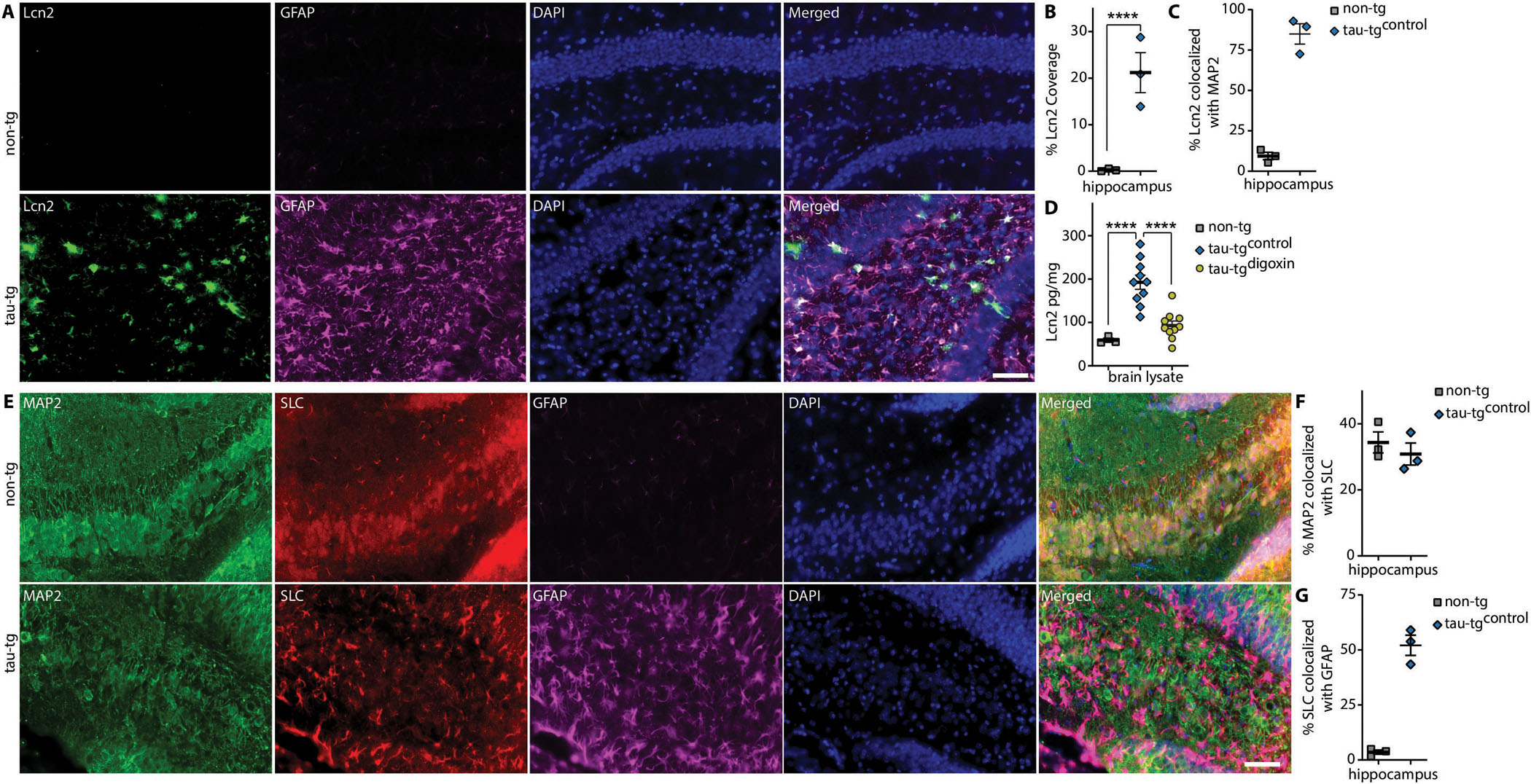

The suppression of secreted pro-inflammatory chemokines and cytokines following digoxin infusion in diseased tau-tg mice potentially protects against tau pathology and brain atrophy. To further evaluate this notion, we assessed the iron-binding cytokine Lipocalin-2 (Lcn2) in addition to TNFα, IL-6, IL-10, IL-1β/IL-1F2, and CXCL10 in tau-tg mice. Several studies have demonstrated that Lcn2 participates in diverse physiological roles, including apoptotic cell death, cellular uptake of iron, and glial activation and we previously reported that the α2-NKA also regulates astrocytic Lcn2 expression in a model of ALS (36–38). IF analysis of Lcn2 in aged diseased tau-tg mice revealed an increase in Lcn2 specifically localized with GFAP that is not present in non-tg littermate controls (% area covered P-Value 0.0082 and co-localized P-value) (Fig. 4A–C). Furthermore, ELISA analysis of Lcn2 in our treatment cohort confirmed elevated Lcn2 in tau-tgcontrol mice relative to non-tg mice (P-value 0.0002) (Fig. 4D). Consistent with the notion that inhibition of the α2-NKA with digoxin attenuates pro-inflammatory chemokines/cytokines, analysis of Lcn2 in the tau-tgdigoxin mice revealed a significant decrease relative to tau-tgcontrol mice (P-value<0.0001) (Fig. 4D). Additional IF analysis for Lcn2 following the knockdown of the α2-NKA with the LV-ATPi revealed a decrease in co-localization in GFP positive astrocytes with Lcn2 protein (P-value<0.0001) (fig. s5).

Fig. 4. Tau-tg display increased astrocytic Lcn2 that is significantly decreased with α2-NKA inhibition.

(A) Immunostaining of Lcn2 (green) co-localized with GFAP (magenta) in aged tau-tg mice (bottom panels) and aged match non-tg control (top panels) quantified for percent area coverage in B and co-localization in C (n=3 per group). Scale bars 50μm. (D) ELISA measurement of Lcn2 in tau-tgdigoxin mice relative to tau-tgcontrol (n=3–10 per group). (C) Immunostaining of MAP2 (green), Lcn2 receptor SLC (red) and GFAP (magenta) in aged non-tg control and aged tau-tg (n=3 per group) quantified for co-localization in F and G. Scale bars 50μm. Significance determined by one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post hoc test. Error bars represent ±s.e.m. ****P < 0.0001.

Previous studies have shown that astrocytic secreted Lcn2 is selectively toxic to neurons but innocuous to glia (39, 40). We next assessed the neuronal expression of Lcn2 receptor Solute Carrier Family 22 Member 17 (SLC) by IF analysis in 9.5-month-old tau-tg mice and non-tg littermates. This analysis revealed SLC localizes with neurons in aged non-tg control littermate mice but displays co-localization with both GFAP and neurons in tau-tg mice (Fig. 4E–G).The presence of Lcn2 receptor SLC in neurons indicates that Lcn2 may potentially target neurons through this receptor in vivo. Collectively, these data suggest that the α2-NKA regulates astrocytic secretion of Lcn2 in tau-tg mice and the inhibition or knockdown of α2-NKA decreases astrocytic Lcn2, which may be targeting neurons via the SLC receptor in tau-tg mice.

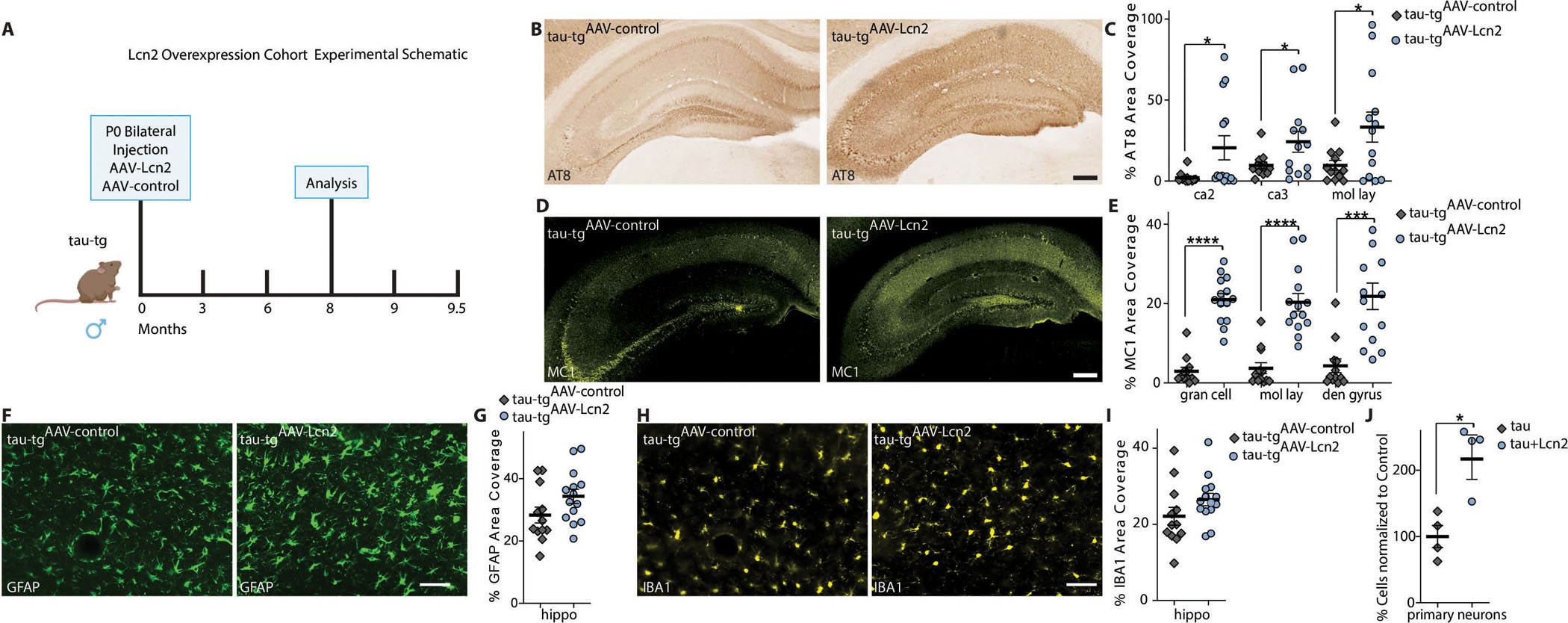

The decrease in elevated Lcn2 protein following the inhibition of the α2-NKA and the localization of Lcn2 receptors on neurons led us to reason that global overexpression of Lcn2 in the brain would progress tau pathology in tau-tg mice. To assess the role of Lcn2 in tauopathies, we overexpressed Lcn2 by intracerebral ventricular injections of AAV2/9 encoding HA-tagged Lcn2 (tau-tgAAV-LCN2) or the control AAV (tau-tgAAV-control) at P0 and aged to 8-month (mid-disease) enabling us to determine a potential detrimental or a protective role as reported in sepsis (Fig. 5A) (41). We performed IF analysis with dual labeling for HA, GFAP, and NeuN, a nuclear marker for neurons to confirm the global expression of secreted Lcn2 in the brain (fig. s6). We next evaluated the effects for the global expression of Lcn2 at mid-disease of tau-tg mice by histopathological analysis of AT8 and MC1. The overexpression of Lcn2 lead to a significant increase in tau-related pathologies throughout the hippocampus relative to tau-tgAAV-control (AT8 ca2 P-value 0.0319, AT8 ca3 P-value 0.0488, AT8 mol lay P-value 0.0284, MC1 gran cell P-value <0.0001, MC1 mol lay P-value <0.0001, MC1 dentate P-value 0.0002) (Fig. 5B–E). Additional histopathological analysis of GFAP and IBA1 revealed no effect, indicating the overexpression of Lcn2 did not exacerbate astrogliosis or microgliosis (Fig. 5 F–I). Thus, the increase in tau pathology suggests Lcn2 predominantly targets neurons in tau-tg mice. We hypothesized that the overexpression and exposure of Lcn2 to neurons may be augmenting tauopathy by increasing neuronal extracellular tau uptake, a proposed mechanism for propagating tau pathology (42). To further investigate this potential mechanism, we evaluated human tau uptake into primary neurons following sustained exposure of recombinant Lcn2 for 48 hours. This analysis revealed Lcn2 treatment of primary neurons significantly increased tau uptake (P-value 0.0157) (Fig. 5J). These data confirm that secreted Lcn2 targets neurons, thereby potentially increasing tauopathy in tau-tg mice via tau uptake without exacerbating astrocyte or microglia reactivity.

Fig. 5. Global overexpression of Lcn2 increased tau pathology accumulation in vivo and induced neuronal tau uptake in vivo.

(A) Experimental schematic and timeline of Lcn2 overexpression cohort. (B) Representative hippocampal brain sections for AT8 phosphorylated pathological tau protein in tau-tg AAV control (tau-tgAAV-control) mice and tau-tg mice overexpressing Lcn2 (tau-tgAAV-Lcn2) quantified by percent area coverage in C (n=12–14 per group). Scale bar, 200μm. (D) Representative hippocampal brain sections for MC1 aggregated pathological tau protein in tau-tg AAV control (tau-tgAAV-control) mice and tau-tg mice overexpressing Lcn2 (tau-tgAAV-Lcn2) quantified by percent area coverage in E. (n=12–14 per group). Scale bar, 200μm. (F) Representative immunostaining of the hippocampus of tau-tgAAV-control mice and tau-tgAAV-Lcn2 mice of GFAP, quantified by percent area coverage in G (n=12–14 per group). Scale bar, 50μm. (H) Representative immunostaining of the hippocampus of tau-tgAAV-control mice and tau-tgAAV-Lcn2 mice of IBA1, quantified by percent area coverage in I (n=12–14 per group). Scale bar, 50μm. (J) Fluorescently labeled h-tau uptake by primary neurons measured by flow cytometry (n=4). Significance determined by unpaired, two-tailed student t-test. Error bars represent ±s.e.m. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001

Discussion

Reactive astrocytes have been shown to be present in many neurodegenerative diseases. However, the role astrogliosis plays in the pathophysiology of AD and related tauopathies remains largely unknown. Here, we demonstrate that the α2-NKA is a main regulator of astrocytic-dependent neuroinflammation. The astrocytic α2-NKA in particular has also been shown to regulate an LPS-dependent inflammatory response triggering activation of pro-inflammatory pathways including TNFα/NFκB in primary glial cells and a mouse model of sepsis (43, 44). In ALS, the astrocytic toxic gain-of-function that is causative for neuronal death is in part regulated by the elevated amounts of the astrocytic α2-NKA ((21). The current study demonstrates a similar mechanism in AD, where the astrocytic α2-NKA was shown to be elevated in human samples and tau-tg mice. Our data indicates that the inhibition of α2-NKA protects against tau-related pathologies, including brain atrophy, by suppressing astrocytic-dependent neuroinflammation in tau-tg mice. These results draw parallel across diverse degenerative diseases, including ALS and dementia-related neurodegeneration, in which astrocytic dependent neuroinflammation maybe be driving the degenerative process.

We demonstrate a critical role for reactive astrocytes in tau pathogenesis by utilizing a pharmacological approach with the cardiac glycoside digoxin that inhibits the α2-NKA and suppresses neuroinflammation in tau-tg mice at two distinct time points. Infusion of digoxin prior to overt pathology models a preventative scenario where inhibition is a preemptive measure taken against the disease before chronic neuroinflammation and tau pathology. In this preventative cohort, tau-tgdigoxin mice displayed a decrease in the accumulation of tau pathology and brain atrophy of the hippocampus, piriform cortex, and ventricular enlargement compared tau-tgcontrol mice. In a second cohort of mice that modeled inhibition after chronic neuroinflammation and overt pathology, digoxin infusion or the shRNA knockdown of α2-NKA protected against tau-associated pathologies. Importantly, the assessment of GFAP and IBA1 expression in both cohorts revealed that inhibition of the α2-NKA prevented and suppressed chronic astrogliosis as well as microgliosis. To further elucidate the anti-neuroinflammatory effects of α2-NKA inhibition, we analyzed critical inflammatory chemokines and cytokines TNFα, IL-6, IL-10, and IL-1β/IL-1F2. These chemokines and cytokines are well known constituents of neuroinflammation present in neurodegeneration. TNFα is a key cytokine that is elevated in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of patients with AD and overexpression of TNFα leads to neuronal death in a mouse model of AD (45, 46). IL-6 is a secreted inflammatory regulator whose concentrations have been shown to correlate with NFT pathology in patients with AD and has been implicated in tau-phosphorylation (47, 48). Whereas, blocking the IL-β/IL-1F2 receptor in a mouse model that exhibits both amyloid plaques and tauopathy reduced neuroinflammation and fibrillary plaques (49). Additionally, we assessed the expression of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10. Though anti-inflammatory, this cytokine has been found to be elevated in pathological conditions, including AD (50, 51). Our analysis revealed that these inflammatory factors were decreased in tau-tgdigoxin mice, further validating that inhibition of α2-NKA suppresses neuroinflammation thereby protecting against tauopathy.

It is also well established that microglia cells play a critical role in neuroinflammation and understanding the dynamic relationship of this cell type with astrocytes remains a critical question. The suppression of astrogliosis and microgliosis following the digoxin infusion in diseased tau-tg mice suggests that attenuation of astrogliosis may modulate microglia activity. Importantly, microglial do not express any Na/K ATPase isoforms; thus, digoxin infusion likely mainly targets the suppression of astrocytic response. Several studies have demonstrated that astrocytes and microglia are in close physical contact and “communicate” through different signaling mechanisms and reactive astrocytes are sources of secreted pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines that illicit microglia activation (52–54). Our studies also identified elevated amounts of CXCL10, a key chemokine predominately expressed by astrocytes that was suppressed in tau-tg mice following the inhibition of the α2-NKA. Astrocytic CXCL10 has been implicated in microglia activation in a model of myelin dysfunction (55). Previous work further corroborated the notion that astrocytes may be influencing microglia reactivity showing that the astrocytic interleukin-3 (IL-3) secretion induces transcriptional and morphological changes in microglia in the presence of Aβ deposition, thus eliciting an acute microglial immune response (56). Additionally, recent studies further demonstrated the networking between microglia and astrocytes in a tauopathy mouse model expressing human Apoe4, the strongest genetic risk factor for AD (57). The conditional knockout of Apoe4 selectively from astrocytes mitigated astrocytic reactivity and was protective via a microglia modulatory mechanism (32). Certain studies have suggested that microglia activity is the primary regulator of the reactive state of astrocytes (58). However, our study and others highlight that glial signaling is bidirectional and highly complex in neuroinflammation and future studies are needed to determine the mechanism by which altering reactivity astrocytes affects microglial function.

Our studies also identified the pro-inflammatory Lcn2 as a candidate cytokine regulated by the α2-NKA. Lcn2 participates in several physiological roles, including apoptotic cell death, cellular uptake of iron, promoting cell migration, and glial activation. In mouse models of Parkinson’s disease and ALS, elevated Lcn2 expression appears to contribute to the neurodegenerative process (36–38). Recently, Lcn2 has become a potential clinical biomarker in Aβ-related dementia in Down Syndrome (59). Importantly, Lcn2 has emerged as a biomarker for vascular dementia (VaD), the second most common cause of dementia after AD. In a recent study Lcn2 has been shown to be increased in the CSF of patients with VaD compared to other neurodegenerative diseases and healthy controls. The authors also demonstrated Lcn2 expression is increased in the reactive astrocytes of AD human samples and localizes primarily with reactive astrocytes as opposed to microglia (60). This study corroborates our finding that there is an increase in astrocytic Lcn2 in tau-tg mice and a decreased following the inhibition of the α2-NKA. Additionally, a recent study also demonstrated Lcn2 exerts a key role in regulating oxysterol induced astrocytic synaptotoxicity effects present in AD (61). Moreover, we found that Lcn2 receptors were expressed in neurons in tau-tg mice and the overexpression of Lcn2 exacerbated tau pathology in aged tau-tg mice. We hypothesized that increased neuronal exposure to Lcn2 promoted tauopathy by increasing neuronal tau uptake and found that subjecting primary neurons to Lcn2 did increase tau uptake. These data provide evidence that reactive astrocytes secrete Lcn2 and target neurons via Lcn2 receptors, thereby increasing tau pathology via increased tau uptake.

There are limitations to the current study, including the inefficient evaluation of pericytes which also express α2-NKA. Although astrocytes are the predominant cell type in the CNS expressing the ATP1A2 allele, potentially intracerebral ventricular administration of digoxin also alters pericytes function which may contribute to the therapeutic effects. Pericytes are vascular mural cells responsible for maintaining the integrity of the blood-brain barrier and have been shown to degenerate in AD (62). However, the contribution of pericytes per se in tau-dependent neurodegeneration remains largely unknown. In this current study, we administered digoxin after disease onset, characterized by chronic astrogliosis, and inhibition of the α2-NKA led to a profound suppression of astrogliosis. This data supports the notion that the astrocytic α2-NKA regulates the reactive state of astrocytes. In additional studies, to further support that the astrocytic α2-NKA is a major factor in progressing tau-associated pathology, we selectively knockdown the ATP1A2 gene using a lentiviral shRNA approach that drives expression of GFP under a GFAP promoter for astrocytic specificity within the hippocampal dentate gyrus. After disease onset, the shRNA-mediated knockdown of the α2-NKA in astrocytes prevented the accumulation of tau pathology surrounding GFP positive astrocytes. Collectively, these analyses suggest the beneficial effects of digoxin are in large part mediated by suppressing astrogliosis. Another limitation is the lack of analysis on oligodendritic precursor cells (OPC), a second cell types expressing α2-NKA and are critical for producing oligodendrocytes and the myelination of the CNS. A recent study has suggested that OPC disruption may be contributing to amyloidosis as a decrease in the number of OPC cells was reported in an aged APP/PS1 mice (63). Although these analyses do not rule out a potential contribution of the α2-NKA expressed in OPC in tau-dependent neurodegeneration, they do support that astrocytes are the primary glial cell altered by the α2-NKA in aged tau-tg mice. Nevertheless, future studies should investigate the potential contribution of the α2-NKA expressed in pericytes and OPC in tau pathogenesis. Furthermore, additional studies are needed to elucidate the intricacies of how astrocytic secreted Lcn2 facilitates neuronal tau uptake and whether these mechanisms play a role progressing in other proteinopathies such as amyloidosis or Parkinson’s disease.

In summary, we have provided evidence that the upregulation of the astrocytic α2-NKA regulates a neuroinflammatory response that contributes to tau pathology and promotes brain atrophy in tau-tg mice. We identified an increased secretion of Lcn2 as a potential mechanism by which astrogliosis increases tauopathy. The current study suggests that reactive astrocytes and or neuroinflammation could be targeted for therapeutic intervention of AD and related tauopathies and in particular, we provide evidence that inhibiting α2-NKA might be effective for treating neurodegenerative tauopathies.

Materials and Methods

Study design

The primary goal of this study was to determine the role of the enriched astrocytic α2-NKA in reactive astrocytes present in tauopathies using the cardiotonic steroid digoxin in a mouse model of tauopathy. Our previous studies have shown that the α2-NKA is enriched in human ALS samples and modulates as gain-of-toxicity inflammatory response in a mouse model for ALS. This study confirmed this enrichment was present in human AD samples and evaluated the role of the α2-NKA in progressing tauopathy by inhibition with digoxin, in tau-tg mice. All mice are on the B6C3F1/J genetic background. The PS19 tau transgenic mouse model expressing human P301S mutant human tau was utilized for its highly progressive tauopathy-associated pathologies. The sample size for the infusion of digoxin and stereotactic injections, as well as endpoints were initially selected on the basis of power analyses of published data (26, 64, 65). For in vivo studies, aged-matched male littermates were randomly assigned to drug or vehicle groups. Females were excluded due to inconsistencies in tauopathy documented in previous studies (26). Mice with brain damage due to misplaced canula were excluded from the study based histological analysis of ventricular damage. Drug dosage was determined as previously described (21). In vitro studies of primary neurons were done with at least three biological replicates per study after initial dosage and time point determination. All analyses were done blindly. All animal studies were done in accordance with Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) guidelines.

Statistical Analysis

All results were reported as mean ± s.e.m and all statistical analysis was conducted in Prism 8 (GraphPad). Significant differences between two groups was performed with Student’s t-test, unless otherwise specified. For nest-building behavior, Chi-square test was utilized to compare difference. One AONVA and Bonferroni post hoc test was used for assessing significance between more than two groups. p-value less than 0.05 (p < 0.05) was considered as statistic significant difference. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. The value of n per group is indicated within each figure legend.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients who participated in this research, their families and the investigators and staff at the Washington University ADRC that provided human tissue samples. The human data results published here are in whole or in part based on data obtained from the AMP-AD Knowledge Portal (https://adknowledgeportal.synapse.org/). Study data were provided by the following sources: The Mayo Clinic Alzheimers Disease Genetic Studies, led by Dr. Nilufer Taner and Dr. Steven G. Younkin, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL using samples from the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging, the Mayo Clinic Alzheimers Disease Research Center, and the Mayo Clinic Brain Bank. We thank the Genome Technology Access Center in the Department of Genetics at Washington University School of Medicine for help with genomic analysis. Digital immunohistopathological images were captured using instrutments in the Alfai Neuroimaging Laboratory and the Washington University Center for Cellular imaging. Experimental schematics were created with BioRender.com.

Funding:

This work was supported by funding from NIH grant R56NS109007 and Cure Alzheimer’s Fund to GG, CMK from NIH grant NS090934 and the JPB foundation to DMH. In addition, the Hope Center Viral Vectors Core, the Hope Center Alafi Neuroimaging Lab and a NIH Shared Instrumentation Grant (S10 RR027552) to Washington University School of Medicine supported this work. Washington University ADRC supported through NIH funding grants P01 AG03991, P30 AG066444, and P01 AG026276. Human data collection was supported through funding by NIA grants P50 AG016574, R01 AG032990, U01 AG046139, R01 AG018023, U01 AG006576, U01 AG006786, R01 AG025711, R01 AG017216, R01 AG003949, NINDS grant R01 NS080820, CurePSP Foundation, and support from Mayo Foundation. Study data includes samples collected through the Sun Health Research Institute Brain and Body Donation Program of Sun City, Arizona. The Brain and Body Donation Program is supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (U24 NS072026 National Brain and Tissue Resource for Parkinsons Disease and Related Disorders), the National Institute on Aging (P30 AG19610 Arizona Alzheimers Disease Core Center), the Arizona Department of Health Services (contract 211002, Arizona Alzheimers Research Center), the Arizona Biomedical Research Commission (contracts 4001, 0011, 05–901 and 1001 to the Arizona Parkinson’s Disease Consortium) and the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinsons Research.” The Genome Technology Access Center in the Department of Genetics at Washington University School of Medicine Center is partially supported by NCI Cancer Center Support Grant #P30 CA91842 to the Siteman Cancer Center and by ICTS/CTSA Grant# UL1TR002345 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). This publication is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR or NIH.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: GG and DMH are inventors on a patent # 16/817339 entitled Anti-tau Constructs licensed by Washington University to C2N Diagnostics on the therapeutic use of anti-tau antibodies. DMH co-founded and is on the scientific advisory board of C2N Diagnostics. C2N Diagnostics has licensed certain anti-tau antibodies to AbbVie for therapeutic development. DMH is on the scientific advisory board of Denali, Genentech, and Cajal Neurosciences and consults for Eli Lilly. DMH receives sponsored research agreements to Washington University from NextCure, C2N Diagnostics, and Novartis. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Supplementary Materials

Datafile S1: Raw data (provided as supplementary Excel file)

References

- 1.Kidd M, Paired helical filaments in electron microscopy of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 197, 192–193 (1963); published online EpubJan 12 ( [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joachim CL, Morris JH, Selkoe DJ, Kosik KS, Tau epitopes are incorporated into a range of lesions in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 46, 611–622 (1987); published online EpubNov ( [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Musiek ES, Holtzman DM, Three dimensions of the amyloid hypothesis: time, space and ‘wingmen’. Nat Neurosci 18, 800–806 (2015); published online EpubJun ( 10.1038/nn.4018nn.4018 [pii]). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karran E, Mercken M, De Strooper B, The amyloid cascade hypothesis for Alzheimer’s disease: an appraisal for the development of therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov 10, 698–712 (2011); published online EpubAug 19 ( 10.1038/nrd3505nrd3505 [pii]). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nagele RG, Wegiel J, Venkataraman V, Imaki H, Wang KC, Contribution of glial cells to the development of amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 25, 663–674 (2004); published online EpubMay-Jun ( 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.01.007S0197458004001034 [pii]). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leyns CEG, Holtzman DM, Glial contributions to neurodegeneration in tauopathies. Mol Neurodegener 12, 50 (2017); published online EpubJun 29 ( 10.1186/s13024-017-0192-x10.1186/s13024-017-0192-x [pii]). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vasile F, Dossi E, Rouach N, Human astrocytes: structure and functions in the healthy brain. Brain Struct Funct 222, 2017–2029 (2017); published online EpubJul ( 10.1007/s00429-017-1383-5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taft JR, Vertes RP, Perry GW, Distribution of GFAP+ astrocytes in adult and neonatal rat brain. Int J Neurosci 115, 1333–1343 (2005); published online EpubSep ( 10.1080/00207450590934570). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sofroniew MV, Vinters HV, Astrocytes: biology and pathology. Acta Neuropathol 119, 7–35 (2010); published online EpubJan ( 10.1007/s00401-009-0619-8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pelvig DP, Pakkenberg H, Regeur L, Oster S, Pakkenberg B, Neocortical glial cell numbers in Alzheimer’s disease. A stereological study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 16, 212–219 (2003) 10.1159/000072805). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pelvig DP, Pakkenberg H, Stark AK, Pakkenberg B, Neocortical glial cell numbers in human brains. Neurobiol Aging 29, 1754–1762 (2008); published online EpubNov ( 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.04.013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ransohoff RM, How neuroinflammation contributes to neurodegeneration. Science 353, 777–783 (2016); published online EpubAug 19 ( 10.1126/science.aag2590). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verkhratsky A, Olabarria M, Noristani HN, Yeh CY, Rodriguez JJ, Astrocytes in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurotherapeutics 7, 399–412 (2010); published online EpubOct ( 10.1016/j.nurt.2010.05.017S1933-7213(10)00077-2 [pii]). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vincent AJ, Gasperini R, Foa L, Small DH, Astrocytes in Alzheimer’s disease: emerging roles in calcium dysregulation and synaptic plasticity. J Alzheimers Dis 22, 699–714 (2010) 10.3233/JAD-2010-1010893P23585404211542 [pii]). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cai Z, Wan CQ, Liu Z, Astrocyte and Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol, (2017); published online EpubAug 18 ( 10.1007/s00415-017-8593-x10.1007/s00415-017-8593-x [pii]). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Furman JL, Sama DM, Gant JC, Beckett TL, Murphy MP, Bachstetter AD, Van Eldik LJ, Norris CM, Targeting astrocytes ameliorates neurologic changes in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci 32, 16129–16140 (2012); published online EpubNov 14 ( 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2323-12.201232/46/16129 [pii]). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lian H, Yang L, Cole A, Sun L, Chiang AC, Fowler SW, Shim DJ, Rodriguez-Rivera J, Taglialatela G, Jankowsky JL, Lu HC, Zheng H, NFkappaB-activated astroglial release of complement C3 compromises neuronal morphology and function associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 85, 101–115 (2015); published online EpubJan 7 (S0896–6273(14)01046–0 [pii] 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.11.018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaltschmidt B, Uherek M, Volk B, Baeuerle PA, Kaltschmidt C, Transcription factor NF-kappaB is activated in primary neurons by amyloid beta peptides and in neurons surrounding early plaques from patients with Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94, 2642–2647 (1997); published online EpubMar 18 ( [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hong S, Beja-Glasser VF, Nfonoyim BM, Frouin A, Li S, Ramakrishnan S, Merry KM, Shi Q, Rosenthal A, Barres BA, Lemere CA, Selkoe DJ, Stevens B, Complement and microglia mediate early synapse loss in Alzheimer mouse models. Science 352, 712–716 (2016); published online EpubMay 6 ( 10.1126/science.aad8373). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu T, Dejanovic B, Gandham VD, Gogineni A, Edmonds R, Schauer S, Srinivasan K, Huntley MA, Wang Y, Wang TM, Hedehus M, Barck KH, Stark M, Ngu H, Foreman O, Meilandt WJ, Elstrott J, Chang MC, Hansen DV, Carano RAD, Sheng M, Hanson JE, Complement C3 Is Activated in Human AD Brain and Is Required for Neurodegeneration in Mouse Models of Amyloidosis and Tauopathy. Cell Rep 28, 2111–2123 e2116 (2019); published online EpubAug 20 ( 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.07.060). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gallardo G, Barowski J, Ravits J, Siddique T, Lingrel JB, Robertson J, Steen H, Bonni A, An alpha2-Na/K ATPase/alpha-adducin complex in astrocytes triggers non-cell autonomous neurodegeneration. Nat Neurosci 17, 1710–1719 (2014); published online EpubDec ( 10.1038/nn.3853nn.3853 [pii]). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoshiyama Y, Higuchi M, Zhang B, Huang SM, Iwata N, Saido TC, Maeda J, Suhara T, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM, Synapse loss and microglial activation precede tangles in a P301S tauopathy mouse model. Neuron 53, 337–351 (2007); published online EpubFeb 01 (S0896–6273(07)00030-X [pii] 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.01.010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Touza NA, Pocas ES, Quintas LE, Cunha-Filho G, Santos ML, Noel F, Inhibitory effect of combinations of digoxin and endogenous cardiotonic steroids on Na+/K+-ATPase activity in human kidney membrane preparation. Life Sci 88, 39–42 (2011); published online EpubJan 03 ( 10.1016/j.lfs.2010.10.027S0024-3205(10)00488-1 [pii]). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cano NJ, Sabouraud AE, Debray M, Scherrmann JM, Dose-dependent reversal of digoxin-inhibited activity of an in vitro Na+K+ATPase model by digoxin-specific antibody. Toxicol Lett 85, 107–111 (1996); published online EpubMay (0378–4274(96)03647–8 [pii]). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cherniavsky Lev M, Karlish SJ, Garty H, Cardiac glycosides induced toxicity in human cells expressing alpha1-, alpha2-, or alpha3-isoforms of Na-K-ATPase. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 309, C126–135 (2015); published online EpubJul 15 (ajpcell.00089.2015 [pii] 10.1152/ajpcell.00089.2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shi Y, Yamada K, Liddelow SA, Smith ST, Zhao L, Luo W, Tsai RM, Spina S, Grinberg LT, Rojas JC, Gallardo G, Wang K, Roh J, Robinson G, Finn MB, Jiang H, Sullivan PM, Baufeld C, Wood MW, Sutphen C, McCue L, Xiong C, Del-Aguila JL, Morris JC, Cruchaga C, Fagan AM, Miller BL, Boxer AL, Seeley WW, Butovsky O, Barres BA, Paul SM, Holtzman DM, ApoE4 markedly exacerbates tau-mediated neurodegeneration in a mouse model of tauopathy. Nature 549, 523–527 (2017); published online EpubSep 28 ( 10.1038/nature24016nature24016 [pii]). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hirata-Fukae C, Li HF, Ma L, Hoe HS, Rebeck GW, Aisen PS, Matsuoka Y, Levels of soluble and insoluble tau reflect overall status of tau phosphorylation in vivo. Neurosci Lett 450, 51–55 (2009); published online EpubJan 23 ( 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.11.023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ballard C, Gauthier S, Corbett A, Brayne C, Aarsland D, Jones E, Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet 377, 1019–1031 (2011); published online EpubMar 19 ( 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61349-9). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deacon RM, Assessing nest building in mice. Nat Protoc 1, 1117–1119 (2006) 10.1038/nprot.2006.170). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maeda S, Djukic B, Taneja P, Yu GQ, Lo I, Davis A, Craft R, Guo W, Wang X, Kim D, Ponnusamy R, Gill TM, Masliah E, Mucke L, Expression of A152T human tau causes age-dependent neuronal dysfunction and loss in transgenic mice. EMBO Rep 17, 530–551 (2016); published online EpubApr ( 10.15252/embr.201541438). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schoch KM, DeVos SL, Miller RL, Chun SJ, Norrbom M, Wozniak DF, Dawson HN, Bennett CF, Rigo F, Miller TM, Increased 4R-Tau Induces Pathological Changes in a Human-Tau Mouse Model. Neuron 90, 941–947 (2016); published online EpubJun 1 ( 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.04.042). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang C, Xiong M, Gratuze M, Bao X, Shi Y, Andhey PS, Manis M, Schroeder C, Yin Z, Madore C, Butovsky O, Artyomov M, Ulrich JD, Holtzman DM, Selective removal of astrocytic APOE4 strongly protects against tau-mediated neurodegeneration and decreases synaptic phagocytosis by microglia. Neuron 109, 1657–1674 e1657 (2021); published online EpubMay 19 ( 10.1016/j.neuron.2021.03.024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yan Y, Ding X, Li K, Ciric B, Wu S, Xu H, Gran B, Rostami A, Zhang GX, CNS-specific therapy for ongoing EAE by silencing IL-17 pathway in astrocytes. Mol Ther 20, 1338–1348 (2012); published online EpubJul ( 10.1038/mt.2012.12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Allan SM, Rothwell NJ, Cytokines and acute neurodegeneration. Nat Rev Neurosci 2, 734–744 (2001); published online EpubOct ( 10.1038/35094583). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krauthausen M, Kummer MP, Zimmermann J, Reyes-Irisarri E, Terwel D, Bulic B, Heneka MT, Muller M, CXCR3 promotes plaque formation and behavioral deficits in an Alzheimer’s disease model. J Clin Invest 125, 365–378 (2015); published online EpubJan ( 10.1172/JCI66771). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim BW, Jeong KH, Kim JH, Jin M, Lee MG, Choi DK, Won SY, McLean C, Jeon MT, Lee HW, Kim SR, Suk K, Pathogenic Upregulation of Glial Lipocalin-2 in the Parkinsonian Dopaminergic System. J Neurosci 36, 5608–5622 (2016); published online EpubMay 18 ( 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4261-15.201636/20/5608 [pii]). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee S, Kim JH, Seo JW, Han HS, Lee WH, Mori K, Nakao K, Barasch J, Suk K, Lipocalin-2 Is a chemokine inducer in the central nervous system: role of chemokine ligand 10 (CXCL10) in lipocalin-2-induced cell migration. J Biol Chem 286, 43855–43870 (2011); published online EpubDec 23 ( 10.1074/jbc.M111.299248M111.299248 [pii]). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tong J, Huang C, Bi F, Wu Q, Huang B, Liu X, Li F, Zhou H, Xia XG, Expression of ALS-linked TDP-43 mutant in astrocytes causes non-cell-autonomous motor neuron death in rats. EMBO J 32, 1917–1926 (2013); published online EpubJul 3 ( 10.1038/emboj.2013.122emboj2013122 [pii]). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bi F, Huang C, Tong J, Qiu G, Huang B, Wu Q, Li F, Xu Z, Bowser R, Xia XG, Zhou H, Reactive astrocytes secrete lcn2 to promote neuron death. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110, 4069–4074 (2013); published online EpubMar 5 ( 10.1073/pnas.1218497110). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zamanian JL, Xu L, Foo LC, Nouri N, Zhou L, Giffard RG, Barres BA, Genomic analysis of reactive astrogliosis. J Neurosci 32, 6391–6410 (2012); published online EpubMay 2 ( 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6221-11.2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kang SS, Ren Y, Liu CC, Kurti A, Baker KE, Bu G, Asmann Y, Fryer JD, Lipocalin-2 protects the brain during inflammatory conditions. Mol Psychiatry 23, 344–350 (2018); published online EpubFeb ( 10.1038/mp.2016.243). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Holmes BB, Furman JL, Mahan TE, Yamasaki TR, Mirbaha H, Eades WC, Belaygorod L, Cairns NJ, Holtzman DM, Diamond MI, Proteopathic tau seeding predicts tauopathy in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111, E4376–4385 (2014); published online EpubOct 14 ( 10.1073/pnas.1411649111). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kinoshita PF, Yshii LM, Orellana AMM, Paixao AG, Vasconcelos AR, Lima LS, Kawamoto EM, Scavone C, Alpha 2 Na(+),K(+)-ATPase silencing induces loss of inflammatory response and ouabain protection in glial cells. Sci Rep 7, 4894 (2017); published online EpubJul 7 ( 10.1038/s41598-017-05075-910.1038/s41598-017-05075-9 [pii]). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leite JA, Isaksen TJ, Heuck A, Scavone C, Lykke-Hartmann K, The alpha2 Na(+)/K(+)-ATPase isoform mediates LPS-induced neuroinflammation. Sci Rep 10, 14180 (2020); published online EpubAug 25 ( 10.1038/s41598-020-71027-5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tarkowski E, Andreasen N, Tarkowski A, Blennow K, Intrathecal inflammation precedes development of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 74, 1200–1205 (2003); published online EpubSep ( 10.1136/jnnp.74.9.1200). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Janelsins MC, Mastrangelo MA, Park KM, Sudol KL, Narrow WC, Oddo S, LaFerla FM, Callahan LM, Federoff HJ, Bowers WJ, Chronic neuron-specific tumor necrosis factor-alpha expression enhances the local inflammatory environment ultimately leading to neuronal death in 3xTg-AD mice. Am J Pathol 173, 1768–1782 (2008); published online EpubDec ( 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080528). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Luterman JD, Haroutunian V, Yemul S, Ho L, Purohit D, Aisen PS, Mohs R, Pasinetti GM, Cytokine gene expression as a function of the clinical progression of Alzheimer disease dementia. Arch Neurol 57, 1153–1160 (2000); published online EpubAug ( 10.1001/archneur.57.8.1153). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Quintanilla RA, Orellana DI, Gonzalez-Billault C, Maccioni RB, Interleukin-6 induces Alzheimer-type phosphorylation of tau protein by deregulating the cdk5/p35 pathway. Exp Cell Res 295, 245–257 (2004); published online EpubApr 15 ( 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.01.002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kitazawa M, Cheng D, Tsukamoto MR, Koike MA, Wes PD, Vasilevko V, Cribbs DH, LaFerla FM, Blocking IL-1 signaling rescues cognition, attenuates tau pathology, and restores neuronal beta-catenin pathway function in an Alzheimer’s disease model. J Immunol 187, 6539–6549 (2011); published online EpubDec 15 ( 10.4049/jimmunol.1100620). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Porro C, Cianciulli A, Panaro MA, The Regulatory Role of IL-10 in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Biomolecules 10, (2020); published online EpubJul 9 ( 10.3390/biom10071017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cisbani G, Koppel A, Knezevic D, Suridjan I, Mizrahi R, Bazinet RP, Peripheral cytokine and fatty acid associations with neuroinflammation in AD and aMCI patients: An exploratory study. Brain Behav Immun 87, 679–688 (2020); published online EpubJul ( 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.02.014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McKimmie CS, Graham GJ, Astrocytes modulate the chemokine network in a pathogen-specific manner. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 394, 1006–1011 (2010); published online EpubApr 16 ( 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.03.111). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.He M, Dong H, Huang Y, Lu S, Zhang S, Qian Y, Jin W, Astrocyte-Derived CCL2 is Associated with M1 Activation and Recruitment of Cultured Microglial Cells. Cell Physiol Biochem 38, 859–870 (2016) 10.1159/000443040). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nimmerjahn A, Kirchhoff F, Helmchen F, Resting microglial cells are highly dynamic surveillants of brain parenchyma in vivo. Science 308, 1314–1318 (2005); published online EpubMay 27 ( 10.1126/science.1110647). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Clarner T, Janssen K, Nellessen L, Stangel M, Skripuletz T, Krauspe B, Hess FM, Denecke B, Beutner C, Linnartz-Gerlach B, Neumann H, Vallieres L, Amor S, Ohl K, Tenbrock K, Beyer C, Kipp M, CXCL10 triggers early microglial activation in the cuprizone model. J Immunol 194, 3400–3413 (2015); published online EpubApr 1 ( 10.4049/jimmunol.1401459). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McAlpine CS, Park J, Griciuc A, Kim E, Choi SH, Iwamoto Y, Kiss MG, Christie KA, Vinegoni C, Poller WC, Mindur JE, Chan CT, He S, Janssen H, Wong LP, Downey J, Singh S, Anzai A, Kahles F, Jorfi M, Feruglio PF, Sadreyev RI, Weissleder R, Kleinstiver BP, Nahrendorf M, Tanzi RE, Swirski FK, Astrocytic interleukin-3 programs microglia and limits Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 595, 701–706 (2021); published online EpubJul ( 10.1038/s41586-021-03734-6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Holtzman DM, Herz J, Bu G, Apolipoprotein E and apolipoprotein E receptors: normal biology and roles in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2, a006312 (2012); published online EpubMar ( 10.1101/cshperspect.a006312). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liddelow SA, Guttenplan KA, Clarke LE, Bennett FC, Bohlen CJ, Schirmer L, Bennett ML, Munch AE, Chung WS, Peterson TC, Wilton DK, Frouin A, Napier BA, Panicker N, Kumar M, Buckwalter MS, Rowitch DH, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Stevens B, Barres BA, Neurotoxic reactive astrocytes are induced by activated microglia. Nature 541, 481–487 (2017); published online EpubJan 26 ( 10.1038/nature21029nature21029 [pii]). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Naude PJ, Dekker AD, Coppus AM, Vermeiren Y, Eisel UL, van Duijn CM, Van Dam D, De Deyn PP, Serum NGAL is Associated with Distinct Plasma Amyloid-beta Peptides According to the Clinical Diagnosis of Dementia in Down Syndrome. J Alzheimers Dis 45, 733–743 (2015) 10.3233/JAD-14251400506437542L272R [pii]). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Llorens F, Hermann P, Villar-Pique A, Diaz-Lucena D, Nagga K, Hansson O, Santana I, Schmitz M, Schmidt C, Varges D, Goebel S, Dumurgier J, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Paquet C, Baldeiras I, Ferrer I, Zerr I, Cerebrospinal fluid lipocalin 2 as a novel biomarker for the differential diagnosis of vascular dementia. Nat Commun 11, 619 (2020); published online EpubJan 30 ( 10.1038/s41467-020-14373-2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Staurenghi E, Cerrato V, Gamba P, Testa G, Giannelli S, Leoni V, Caccia C, Buffo A, Noble W, Perez-Nievas BG, Leonarduzzi G, Oxysterols present in Alzheimer’s disease brain induce synaptotoxicity by activating astrocytes: A major role for lipocalin-2. Redox Biol 39, 101837 (2021); published online EpubFeb ( 10.1016/j.redox.2020.101837). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sengillo JD, Winkler EA, Walker CT, Sullivan JS, Johnson M, Zlokovic BV, Deficiency in mural vascular cells coincides with blood-brain barrier disruption in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Pathol 23, 303–310 (2013); published online EpubMay ( 10.1111/bpa.12004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chacon-De-La-Rocha I, Fryatt G, Rivera AD, Verkhratsky A, Raineteau O, Gomez-Nicola D, Butt AM, Accelerated Dystrophy and Decay of Oligodendrocyte Precursor Cells in the APP/PS1 Model of Alzheimer’s-Like Pathology. Front Cell Neurosci 14, 575082 (2020) 10.3389/fncel.2020.575082). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gallardo G, Wong CH, Ricardez SM, Mann CN, Lin KH, Leyns CEG, Jiang H, Holtzman DM, Targeting tauopathy with engineered tau-degrading intrabodies. Mol Neurodegener 14, 38 (2019); published online EpubOct 22 ( 10.1186/s13024-019-0340-610.1186/s13024-019-0340-6 [pii]). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ising C, Gallardo G, Leyns CEG, Wong CH, Jiang H, Stewart F, Koscal LJ, Roh J, Robinson GO, Remolina Serrano J, Holtzman DM, AAV-mediated expression of anti-tau scFvs decreases tau accumulation in a mouse model of tauopathy. J Exp Med 214, 1227–1238 (2017); published online EpubMay 1 ( 10.1084/jem.20162125jem.20162125 [pii]). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

This work was supported by funding from NIH grant R56NS109007 and Cure Alzheimer’s Fund to GG, CMK from NIH grant NS090934 and the JPB foundation to DMH. In addition, the Hope Center Viral Vectors Core, the Hope Center Alafi Neuroimaging Lab and a NIH Shared Instrumentation Grant (S10 RR027552) to Washington University School of Medicine supported this work. Washington University ADRC supported through NIH funding grants P01 AG03991, P30 AG066444, and P01 AG026276. Human data collection was supported through funding by NIA grants P50 AG016574, R01 AG032990, U01 AG046139, R01 AG018023, U01 AG006576, U01 AG006786, R01 AG025711, R01 AG017216, R01 AG003949, NINDS grant R01 NS080820, CurePSP Foundation, and support from Mayo Foundation. Study data includes samples collected through the Sun Health Research Institute Brain and Body Donation Program of Sun City, Arizona. The Brain and Body Donation Program is supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (U24 NS072026 National Brain and Tissue Resource for Parkinsons Disease and Related Disorders), the National Institute on Aging (P30 AG19610 Arizona Alzheimers Disease Core Center), the Arizona Department of Health Services (contract 211002, Arizona Alzheimers Research Center), the Arizona Biomedical Research Commission (contracts 4001, 0011, 05–901 and 1001 to the Arizona Parkinson’s Disease Consortium) and the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinsons Research.” The Genome Technology Access Center in the Department of Genetics at Washington University School of Medicine Center is partially supported by NCI Cancer Center Support Grant #P30 CA91842 to the Siteman Cancer Center and by ICTS/CTSA Grant# UL1TR002345 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). This publication is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR or NIH.