CKD affects approximately 37 million of those in the United States and $114 billion were spent caring for this population in 2016, most of which was spent on RRT.1,2 Kidney transplantation has the best clinical outcomes at the lowest cost, but not everyone is eligible for a transplant. As a result, most individuals will receive some form of dialysis, and home therapies offer similar outcomes to facility-based dialysis at lower costs.

The laudable Advancing American Kidney Health Initiative (“the Initiative”) was announced in 2019 with the aim to produce “better outcomes, often at a lower cost, for millions of Americans” with CKD. One of the key goals is to make care more person-centered and to reduce costs by increasing the utilization of home dialysis or transplantation. The ambitious, and perhaps aspirational, goal was to more than double the percentage of patients treated with these therapies to 80% by 2025.

Although we support the Initiative and its goals, we believe this target cannot be plausibly reached by increasing the numbers of individuals who receive home dialysis or transplantation. In fact, the most plausible way to hit the target is to reduce the total number of patients treated with RRT by restricting access to facility-based hemodialysis (HD), increasing the proportion of elderly patients who choose conservative (palliative) care, and limiting the ability of patients to choose their dialysis modality. As a consequence, we argue the chosen metric may incent strategies that would impede progress toward the Initiative’s true goals.

A High-Level View of How Individuals with ESKD Are Treated

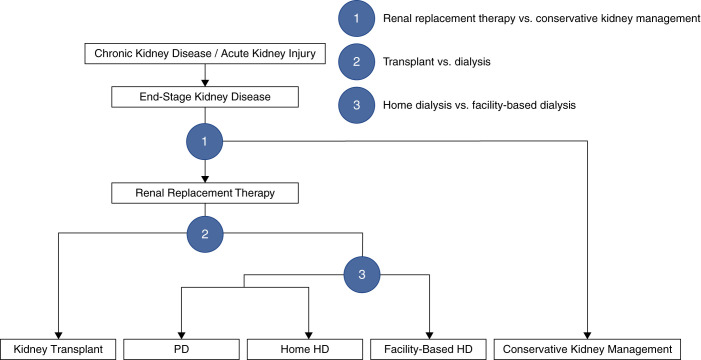

Patients who develop kidney failure are faced with a decision between RRT and conservative (palliative) kidney management (symptom-based care without dialysis or transplant; Figure 1). If patients choose RRT, they then must decide between transplantation and dialysis, recognizing that many patients will not be eligible for a transplant. Patients who opt for dialysis can choose between home dialysis (peritoneal dialysis [PD] or home HD) and facility-based HD.

Figure 1.

A three-step process is required to decide on the appropriate treatment modality for patients with kidney failure. Patients are assigned to one of five modalities: kidney transplantation, PD, home HD, facility-based HD, or conservative kidney management. A number of patient, provider, and health system factors influence the decision making at each step and, therefore, how patients are distributed among the different treatments. All five treatment approaches must be accounted for to understand the performance of a health system and the resources required to manage this population. Home dialysis refers to PD and home HD, whereas renal replacement therapy refers to all therapies except conservative kidney management.

The percentage of patients treated with home dialysis and transplantation is calculated as:

Historically, the focus has been on improving the numerator. However, we argue that the denominator is more important in the US context. Disaggregating the two and examining the absolute numbers of patients receiving each treatment modality helps to illustrate why this is the case.

The Numerator: Home Dialysis and Kidney Transplantation in the United States

The Initiative aims to double the number of organs available for transplant by 2030, suggesting there is considerable room to improve uptake of transplantation in the United States. In 2016, the United States ranked fifth in the world for its population-based rate of kidney transplantation—with a prevalent rate that was similar, in absolute terms, to that of the global leader, Portugal (643 per million population [pmp] versus 694 pmp, respectively).2 The US rate of home dialysis utilization was similarly strong and ranked seventh. In fact, if the combined, prevalent rate of home dialysis and transplantation was considered, the United States ranked third globally, at 823 pmp.2 So, if performance, as assessed by the numerator, is relatively strong, why is the United States considered to be underperforming overall? Although incremental gains in absolute rates of home dialysis and transplantation could be made, the perception of poor performance in this area is driven by the denominator. The large number of individuals receiving RRT reduces the percentage of patients treated with home dialysis or transplantation.

The Denominator Problem: The United States Has Very High Rates of RRT and Few Patients Opt for Conservative Care

Rates of RRT vary nearly 30-fold worldwide. Although some of this variation could be attributed to differences in the burden and progression of CKD, other factors are probably more important.2 The United States treats more patients with RRT than any other country in the world, except Taiwan and Japan. To put this in perspective, the rate of treated kidney failure is 85% higher in the United States than it is in Canada (2196 versus 1346 pmp). The high US rate is due to widespread availability of treatment and the fact that few patients will opt for conservative care.3 In a study of patients from Veterans Affairs hospitals, only 14.5% of patients with kidney failure chose conservative management overall.3 This may overestimate the proportion of patients receiving conservative care given that the study involved an older population, and some individuals who intend to do conservative care ultimately change their minds and pursue dialysis.

Hong Kong is the only country achieving the goal of treating >80% of patients with home dialysis or transplantation. Their rate of RRT is 40% lower than that in the United States, and 70% lower in individuals over age 75.2 As a result, the pool of treated patients is much larger in the United States and includes a substantially larger number and proportion of elderly patients. The expansion of the denominator with individuals who are generally not eligible for transplantation and are less likely to be treated with home dialysis demonstrates the challenge of achieving “high performance” in the US context. The coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic led to a decline in the prevalent dialysis population in 2020 as a consequence of increased mortality—an unfortunate and, hopefully, transient effect.4 Addressing the timing of dialysis initiation in the United States could also reduce the denominator by implementing an intent-to-defer strategy. In the Initiating Dialysis Early and Late (IDEAL) trial, the percentage of patients with kidney failure receiving dialysis was 3.8% lower when this strategy was used.5 Finally, measures to facilitate the earlier identification of CKD and slow progression may have an effect on the denominator. However, making significant gains in the percentage of patients treated with home dialysis or transplantation would likely require reducing access to RRT, especially among the elderly.

Aligning Measures of Success with Policy Goals

The discussion so far has highlighted the tension between maximizing the numbers of patients for whom RRT is available and achieving high rates of home dialysis and transplantation. In fact, not one country that appears in the top ten for rates of RRT also appears in the top ten for the percentage of patients treated with home dialysis or transplantation.2

The Central Renal Committee of Hong Kong adopted a PD-First policy in 1985. At that time, Hong Kong was unable to provide dialysis to all patients who needed it and there was a desire to expand services. After careful consideration, PD was selected as the first-line treatment for kidney failure, given its favorable cost profile. The policy dictated that patients with kidney failure would receive PD unless they had a medical contraindication or could pay out of pocket for facility-based HD.6 By 2016, 74% of patients on dialysis were treated with PD. However, success came at the cost of restricting patient choice in dialysis modality selection, limited access to facility-based HD, and low rates of RRT in the elderly.3,7 This was justified by the overarching policy goal of treating more patients with limited resources, and their measure of success was aligned with that goal.

The US context is very different than the situation Hong Kong faced in 1985. RRT is widely available, patient autonomy is highly valued, and the Initiative is focused on improving the quality of care and increasing patient choice, while reducing costs. The numbers of people treated with home dialysis and transplantation could be increased to some degree, but they are already relatively high. The only real opportunities to make progress is by addressing the denominator (reducing the number of patients who receive RRT) or restricting modality choice in patients who might otherwise prefer facility-based dialysis. As for the likelihood of this happening in clinical practice, it is somewhat dependent on the motivation to improve performance and the consequences of not hitting targets. Because these actions are not consistent with the stated policy goals, the measure of success should be revisited.

The overall objective of the Initiative is to produce better outcomes for patients with CKD at lower cost. The goals of the Initiative are laudable, and the focus on action plans and performance metrics all suggest a commitment to meaningful change. We applaud the emphasis on person-centered treatment options, but believe that the metric chosen to measure progress toward this goal should be reconsidered because it may have unintended consequences, and will likely impede the Initiative from achieving its desired results.

Disclosures

P.G. Blake reports serving in an advisory or leadership role for American Journal of Nephrology (on the editorial board) and Ontario Renal Network (as medical director); receiving honoraria from Baxter Global; and having consultancy agreements with Ontario Renal Network. M.J. Oliver reports receiving honoraria from Amgen, Baxter Healthcare, and Janssen; being the sole owner of Oliver Medical Management Inc., which is a private corporation that licenses the Dialysis Measurement Analysis and Reporting (DMAR) software system; having patents or royalties with Oliver Medical Management Inc., which is co-owner of a Canadian patent for DMAR systems; and having other interests in, or relationships with, Ontario Health and Ontario Renal Network (for contracted medical leads). R.R. Quinn reports receiving honoraria from Baxter (PD University and advisory board); having consultancy agreements with Baxter Corporation; receiving research funding from International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis PD Catheter Registry (Baxter partially funding project); and having a patent for the DMAR System. M. Tonelli reports serving in an advisory or leadership role for the American Journal of Kidney Diseases, Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes, and Kidney International; receiving honoraria from AstraZeneca (lecture fees); receiving research funding from B. Braun in 2019 as a lecture fee, the fee was donated to charity; and having other interests in, or relationships with, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

None.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

Author Contributions

N.N. Lam and R.R Quinn were responsible for methodology; R.R Quinn wrote the original draft, provided supervision, and was responsible for data curation, formal analysis, investigation, project administration, and resources; and all authors conceptualized the study and reviewed and edited the manuscript.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention : Chronic kidney disease in the United States, 2021. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/kidneydisease/publications-resources/CKD-national-facts.html. Accessed September 2, 2021

- 2.The United States Renal Data System : 2018 USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD, United States Renal Data System, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong SP, Hebert PL, Laundry RJ, Hammond KW, Liu CF, Burrows NR, et al. : Decisions about renal replacement therapy in patients with advanced kidney disease in the US Department of Veterans Affairs, 2000–2011. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 1825–1833, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.United States Renal Data System : 2021 USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD, United States Renal Data System, 2021

- 5.Cooper BA, Branley P, Bulfone L, Collins JF, Craig JC, Fraenkel MB, et al. ; IDEAL Study : A randomized, controlled trial of early versus late initiation of dialysis. N Engl J Med 363: 609–619, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li PK, Chow KM: Peritoneal dialysis-first policy made successful: perspectives and actions. Am J Kidney Dis 62: 993–1005, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwok W, Yong S, Kwok O: Outcomes in elderly patients with end-stage renal disease: Comparison of renal replacement therapy and conservative management. Hong Kong J Nephrol 19: 42–56, 2016 [Google Scholar]