Abstract

The gfp-tagged Pseudomonas fluorescens biocontrol strain DR54-BN14 was introduced into the barley rhizosphere. Confocal laser scanning microscopy revealed that the rhizoplane populations of DR54-BN14 on 3- to 14-day-old roots were able to form microcolonies closely associated with the indigenous bacteria and that a majority of DR54-BN14 cells appeared small and almost coccoid. Information on the viability of the inoculant was provided by a microcolony assay, while measurements of cell volume, the intensity of green fluorescent protein fluorescence, and the ratio of dividing cells to total cells were used as indicators of cellular activity. At a soil moisture close to the water-holding capacity of the soil, the activity parameters suggested that the majority of DR54-BN14 cells were starving in the rhizosphere. Nevertheless, approximately 80% of the population was either culturable or viable but nonculturable during the 3-week incubation period. No impact of root decay on viability was observed, and differences in viability or activity among DR54-BN14 cells located in different regions of the root were not apparent. In dry soil, however, the nonviable state of DR54-BN14 was predominant, suggesting that desiccation is an important abiotic regulator of cell viability.

Fluorescent pseudomonads have the potential to suppress fungal plant pathogens (12, 37) and thereby improve plant growth. Several factors such as rhizosphere competence and the production of antibiotics are considered to be important for efficient control of pathogens (10, 11). In addition, it is essential that the inoculant be able to establish a metabolically active population in the rhizosphere which is capable of expressing the traits needed for biological control (11). We still need to understand the factors governing the distribution and activity patterns of the inoculants. The rhizosphere habitat exhibits great spatial and temporal heterogeneity, making information at the level of single cells invaluable for addressing these factors.

The single-cell distribution of pseudomonads in the rhizosphere has previously been studied by scanning electron microscopy (4, 7), by using gfp-tagged cells (2), and by immunochemical techniques (15). However, because these studies have been performed exclusively in gnotobiotic systems, the effects of the indigenous population on the distribution of an inoculated strain are not known.

The rhizosphere is generally referred to as a hot spot for bacterial growth due to the release of plant exudates. In accordance with this, Söderberg and Bååth (33) found that the activity of bacterial populations in the rhizosphere of young barley roots was higher than in bulk soil, as measured by thymidine and leucine incorporation. However, it is less clear whether the metabolic activity of pseudomonads is higher in the rhizosphere than in bulk soil (20, 22).

Loss of culturability and the occurrence of a viable but nonculturable (VBNC) state have been reported for pseudomonads in the soil environment. For example, Troxler et al. (34) introduced Pseudomonas fluorescens CHA0 to outdoor lysimeters planted with wheat and found that after 8 months fewer than 2% of the CHA0 cells were culturable and only ca. 25% were viable, as determined by Kogure’s nalidixic-acid assay (19). However, information on the cell viability in the rhizosphere has not yet been linked to other indicators of cellular activity.

We report here on the single-cell distribution, viability, and activity of gfp-tagged P. fluorescens DR54-BN14 in the rhizosphere of barley planted in an agricultural soil. The localization of DR54-BN14 in relation to the indigenous rhizoplane populations was determined by confocal laser scanning microscopy. The viability of the strain was examined by a microcolony assay recording the capability of the cells to perform one or more cell divisions (1, 29). The cell volume, intensity of green fluorescent protein (GFP) fluorescence, and ratio of dividing cells to total cells were used as indicators of cellular activity. The viabilities and activities of DR54-BN14 cells in different regions of the root were compared, and factors affecting the persistence and viability of the inoculated cells were examined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of a gfp-tagged P. fluorescens strain.

The sugar beet rhizosphere isolate P. fluorescens DR54 (biovar 1) is effective against several soil-borne fungal diseases of plants (25). The strain was chromosomally marked with kanamycin resistance and GFP by triparental mating using a modified pUT vector (9) with the npt gene and the gfpmut3b gene (5) within the Tn5 cassette. The gfpmut3b gene was controlled by the constitutive promoter PA1/04/03 (26). Bright green fluorescent exconjugant colonies of DR54 were identified by epifluorescence microscopy, and the fluorescence intensity was measured by a Fluostar-P fluorometer (excitation wavelength, 485 nm; emission wavelength, 535 nm) (BMG-LabTechnologies, Offenburg, Germany).

Four mutants displaying the highest fluorescence were selected and compared to the wild type by determination of growth rates at 28°C in glucose minimal medium (16) and in Luria broth (LB) (23). Biolog (Hayward, Calif.) GN plates were used to examine the mutants’ utilization of 95 different carbon sources. No differences in growth rates and Biolog fingerprints were observed between the four mutants and the wild type. The stability of the Tn5 insertions was tested by growing the four mutants in liquid LB for approximately 50 generations. Microscopic examinations and plating on LB alone and LB supplemented with 50 μg of kanamycin ml−1 showed no loss of either green fluorescence or kanamycin resistance after repeated subculturing.

P. fluorescens DR54 and one of the mutant strains, DR54-BN14, were tested for their abilities to colonize barley roots. Seed inoculation and extraction of bacteria from the rhizosphere of 8-day-old barley plants were carried out as described below. CFU were enumerated after growth for 2 days at 25°C on Gould S1 agar (14). No differences in root colonization between the two strains were observed (data not shown).

Inoculation and growth of barley plants.

An overnight culture of P. fluorescens DR54-BN14 in LB was washed twice in 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), and the final concentration was adjusted to 1010 CFU ml−1. Barley seeds (Hordeum vulgare cv. Pastoral), pregerminated on moist filter paper for 48 h, were added to the bacterial suspension and incubated for 30 min with slow stirring. Inoculated seedlings with primary roots 5 to 10 mm long were each planted in a pot containing approximately 70 g of a sandy loam agricultural soil (Højbakkegård, Tåstrup, Denmark). The soil had been sieved (mesh size, 3 mm) and adjusted with tap water to 80% of the water-holding capacity (WHC), corresponding to 15% (wt/wt) water. The pots were incubated in a growth chamber at 18 to 22°C with a 12-h light, 12-h darkness cycle. Aliquots of 3 to 6 ml of a 5% (vol/vol) Hornum plant nutrient solution (P. Brøste Industri A/S, Lyngby, Denmark) were added to the top soil so that a soil moisture of 80% of WHC was maintained.

Extraction of P. fluorescens DR54-BN14 from the barley rhizosphere.

Triplicate pots were randomly picked on selected sampling days. Unattached soil was gently removed from the roots. The roots of each plant were then cut into three segments of equal length (designated upper, middle, and lower rhizosphere). Root segments and seeds were separately transferred to glass tubes with 8 ml of 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0).

The tubes were vortexed for 60 s, sonicated for 5 min in a Branson 5210 ultrasonic bath, and vortexed for an additional 60 s to extract bacteria from the rhizosphere samples. The plant material in each tube was removed, thoroughly rinsed in MilliQ-water, dried for 24 h at 110°C, and weighed to determine the dry weight. Soil particles in the remaining rhizosphere extract were sedimented by centrifugation for 5 min at 800 × g.

In some experiments, the rhizosphere soil was removed from whole roots before the extraction of bacteria by careful rinsing of the roots for 20 to 30 s in 8 ml of 10 mM phosphate buffer. Bacteria extracted from this fraction were considered rhizosphere soil bacteria, while those extracted from the root tissue were considered rhizoplane bacteria.

Detection of P. fluorescens DR54-BN14 in the barley rhizosphere.

The number of CFU of DR54-BN14 was determined by plating 0.1 ml of an appropriate dilution of the extract on LB plates supplemented with 50 μg of kanamycin ml−1 and 25 μg of natamycin ml−1 (Delvocid fungicide; Gist-Brocades, Delft, The Netherlands). Plates were incubated for 2 days at 25°C.

Direct detection of DR54-BN14 was carried out by epifluorescence microscopy. Aliquots of the extracts containing approximately 106 cells of DR54-BN14 were mixed with 5 ml of 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) and filtered through a 0.2-μm-pore-size polycarbonate membrane (Poretics Products, Livermore, Calif.). A cellulose nitrate filter (Sartorius AG, Göttingen, Germany) was used as a filter support. The polycarbonate membrane was then placed on a microscope slide and mounted in Vectashield (Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, Calif.). Digital images of green fluorescent cells on the membrane were recorded (exposure time, 2 s) with a charge-coupled-device camera (cooled slow-scan, KAF 1400 chip, 12-bit; Photometrics Ltd., Tucson, Ariz.) mounted on a Zeiss Axioplan microscope equipped with an HBO-100 mercury lamp and a Zeiss filter set 10 (excitation filter, 450 to 490 nm; dichroic mirror, 510 nm; emission filter, 515 to 565 nm). As many as eight images with a total of approximately 400 cells were recorded per membrane. The cell volume, GFP fluorescence intensity, and fraction of dividing cells of DR54-BN14 were determined by image analysis using the UNIX program Cellstat (24).

The spatial distribution of microorganisms on the root surface was examined in situ with a Leica Lasertechnik TCS 4D confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM) equipped with an argon/krypton ion laser (excitation wavelengths, 488, 568, and 647 nm) and a UV laser (excitation wavelength, 360 nm) (Table 1). Barley plants were inoculated with DR54-BN14 and grown as described above. Roots were collected on different sampling days, rinsed in MilliQ-water for 10 to 20 s, and incubated for 10 min in a 1-μg ml−1 DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) solution. Excised root segments 5 to 20 mm long were examined with the CLSM, and two-dimensional sections were recorded and combined to three-dimensional images as described previously (26). To discriminate between the green fluorescence emitted by cells of DR54-BN14, the light-blue fluorescence emitted by the DAPI-stained microorganisms, and the autofluorescence of the root, optical filters were used as listed in Table 1. All image processing was performed with the Imaris software package (Bitplane AG, Zürich, Switzerland) running on a Silicon Graphics (Mountain View, Calif.) Indigo 2 workstation.

TABLE 1.

Excitation and emission wavelengths

| Image | Excitation wavelength (nm) | Emission wavelengtha (nm) | Color in RGBb display |

|---|---|---|---|

| Green fluorescent cells | 488 | BP530 | Green |

| DAPI-stained cells | 360 | BP440/LP450 | Light blue |

| Root, soil particles | 488, 568 | LP590 | Red/brown |

BP, band pass; LP, long pass.

RGB, red-green-blue.

Viability of P. fluorescens DR54-BN14 in the barley rhizosphere.

A microcolony assay, modified from the procedure of Binnerup et al. (1), was used to demonstrate viable cells of DR54-BN14. The microcolony method was chosen as a viability assay because it proved to give a significantly higher number of viable cells of DR54-BN14 than Kogure’s nalidixic-acid method (19) (data not shown). In the assay, polycarbonate membranes with approximately 105 cells of DR54-BN14 (prepared as described above) were placed on LB plates and incubated in the dark at 25°C for 6 h. Green fluorescent microcolonies (mCFU) of 2 to 16 cells represented viable cells of DR54-BN14, whereas single cells were designated nonviable. A minimum of 100 mCFU were counted per membrane.

Factors affecting the culturability and viability of P. fluorescens DR54-BN14.

The effect of soil moisture on the culturability and viability of DR54-BN14 was investigated. After 7 days of incubation of barley plants, selected pots were no longer watered (water content was below 10% of the WHC after a few days) while other pots were placed in a few millimeters of water to obtain a soil slurry (water content, ca. 160% of WHC). The numbers of culturable, VBNC, and nonviable cells of DR54-BN14 on the roots was enumerated 10 and 25 days later as described previously.

The effect of defoliation was studied by clipping off the stem and leaves of 17-day-old barley plants and then, at 1, 3, 6 and 14 days after clipping, enumerating DR54-BN14 cells in the rhizospheres of growing and defoliated plants. After 6 days, the roots of defoliated plants displayed clear signs of degeneration in the form of mechanical fragility.

Activity of P. fluorescens DR54-BN14 during starvation.

An overnight culture of P. fluorescens DR54-BN14 was washed twice (as previously described) and adjusted to approximately 5 × 107 CFU ml−1 in 10 mM phosphate buffer. The suspension was incubated at room temperature on a rotary shaker at 200 rpm. At each sampling time, 50 μl of the suspension was mixed with 5 ml of phosphate buffer and filtered through a 0.2-μm-pore-size polycarbonate membrane. For unknown reasons, starved cells did not adhere to the membrane surface as well as growing cells. Therefore, to prevent the cells from floating during microscopy, the polycarbonate membranes were coated with poly-l-lysine (0.01% solution). Epifluorescence microscopy and image analysis were performed as for the rhizosphere extracts.

Data analysis.

Analysis of variance and z tests were performed by using the SigmaStat software for Windows (Jandel Corp., Erkrath, Germany).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Distribution of P. fluorescens DR54-BN14 in the barley rhizosphere.

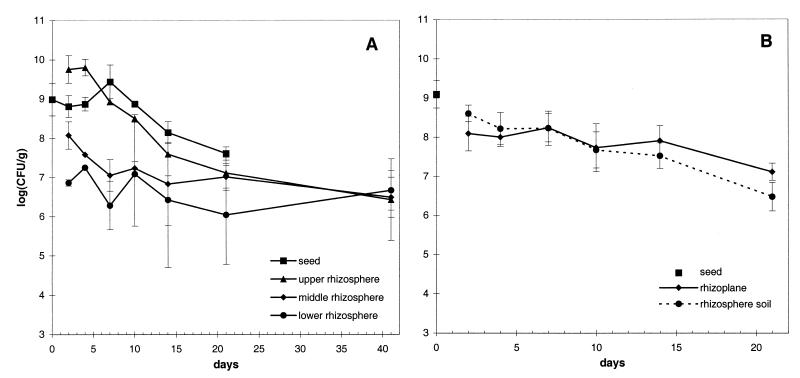

The gfp-tagged P. fluorescens DR54-BN14 was introduced to the barley rhizosphere by inoculation of 2-day-old seedlings. DR54-BN14 persisted on the seed at population densities between ca. 5 × 109 and 1 × 108 CFU g of dry seed−1 for as long as the seed could be recovered from the soil and established itself in the rhizosphere (Fig. 1A). The population on the upper third of the root declined from ca. 7 × 109 to 1 × 107 CFU g of dry root−1 during the 41-day-long experiment, while on the lower third of the roots, the population remained relatively constant at 1 × 107 CFU g of dry root−1. Thus, DR54-BN14 was, initially, most abundant on the upper third of the roots, in accordance with previous studies of gnotobiotic (4) and natural (8) root systems. A more even distribution was seen towards the end of the experiment, probably due to the limited space for root extension in the pots and the spread of bacteria by watering.

FIG. 1.

Population size of P. fluorescens DR54-BN14 in different rhizosphere sections (A) and in the rhizoplane and rhizosphere soil (B) of barley. The data are represented as log10 units of CFU per gram (dry weight) of plant material. On day 41 the seeds were no longer identifiable (A). In panel B, the bacterial cell density on the seeds was measured only on day 0. Error bars, standard deviations (SD) of triplicate samples.

The sizes of the populations of DR54-BN14 in the rhizosphere soil and on the rhizoplane were comparable (P > 0.05) through a 3-week period (Fig. 1B). In contrast, P. fluorescens DF57 and Ag1 were predominantly found in the rhizosphere soil (20, 21). Hence, different bacterial populations might be present in different parts of the rhizosphere, as reported for Paenibacillus and Pseudomonas (32, 36).

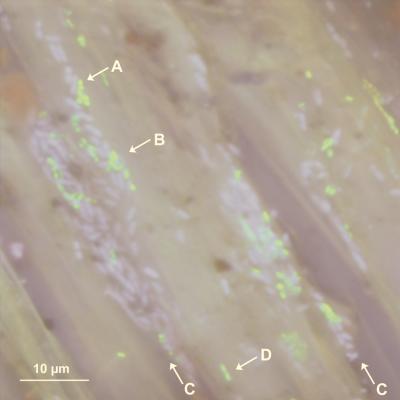

The large rhizoplane population of DR54-BN14 prompted us to investigate the localization of individual DR54-BN14 cells on the root surface by CLSM. Roots from 20 plants (3 to 14 days old) were examined. Three observations were frequently made by this qualitative analysis: (i) considerable variability in the cell size and division state of DR54-BN14 was observed within short distances (<30 μm; data not shown), although a majority of the cells appeared small and almost coccoid; (ii) DR54-BN14 cells were often situated in the crevices between the epithelial cells; and (iii) the green fluorescent cells were clustered in microcolonies, and these were often physically associated with the DAPI-stained indigenous bacteria (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Localization of P. fluorescens DR54-BN14 on the rhizoplane of barley roots as visualized by CLSM. The image shows DR54-BN14 (green cells) and DAPI-stained indigenous bacteria (light-blue cells) on the upper-third section of a 7-day-old barley root. The epithelial cells appear as the greyish background. DR54-BN14 was often clustered in microcolonies mixed with indigenous bacteria (arrows A and B), and these were commonly situated near the crevices of the epithelial cells (arrow C; also indicating the orientation toward the root base). The cell morphology of DR54-BN14 varied considerably, from small, almost coccoid cells (arrow A) to rod-shaped dividing cells (arrow D).

A similar distribution and formation of microcolonies has been observed for other pseudomonads in gnotobiotic systems (2, 4, 7, 15). However, our approach allowed us, to our knowledge for the first time, to demonstrate that microcolonies of a plant growth-promoting pseudomonad were closely associated with cells of indigenous bacterial populations. It has recently been demonstrated that different bacterial strains communicate by diffusible compounds such as N-acyl-l-homoserine lactones in the rhizosphere (28). Mixed microcolonies of pseudomonads and indigenous bacteria at the rhizoplane, possibly embedded in a mucigel, might be ideal locations for cellular interactions mediated by diffusible signalling (4, 7).

Viability and activity of P. fluorescens DR54-BN14 in the barley rhizosphere.

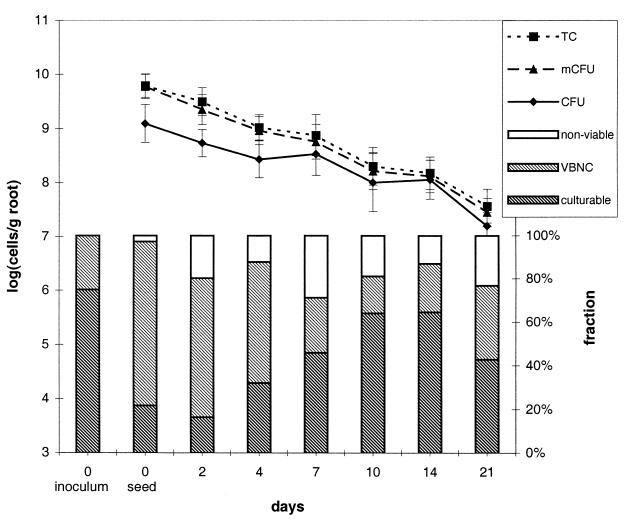

Total cell counts, microcolony counts, and culturable cell numbers of DR54-BN14 all declined during the 21-day experimental period (Fig. 3). Prior to inoculation, ca. 25% of DR54-BN14 cells were VBNC, but no nonviable cells were detected (detection limit, 0.1%). However, immediately after inoculation, ca. 75% of the extracted DR54-BN14 cells were VBNC, while 3% were nonviable (Fig. 3). The low culturability seen immediately after inoculation may be due to stresses encountered during inoculation. During the remaining part of the experiment, an average of 19% of the DR54-BN14 population on the root samples was nonviable, while the fraction of VBNC cells decreased with plant age from ca. 60% on the first 4 days to an average of 25% thereafter (Fig. 3). There were no measurable differences in viability pattern among root regions (upper, middle, lower, rhizoplane, and rhizosphere soil [data not shown]). For comparison, Troxler et al. found no VBNC or “inactive-dormant” (equivalent to cells referred to as nonviable in this paper) cells of P. fluorescens CHA0 in the interiors of maize roots (35), while these physiological states were dominant in the top soil of outdoor cereal lysimeters (34). These authors suggested that the occurrence of nonculturable cells was affected by water availability and the presence of roots in the soil, two factors which are addressed below.

FIG. 3.

Culturability and viability of P. fluorescens DR54-BN14 in the barley rhizosphere. Curves represent log10 units of total cells (TC), microcolonies (mCFU), and culturable cells (CFU) per gram (dry weight) of barley root. Error bars, SD of triplicate samples. The bar graph shows percentages of nonviable, VBNC, and culturable cells of P. fluorescens DR54-BN14 on barley roots.

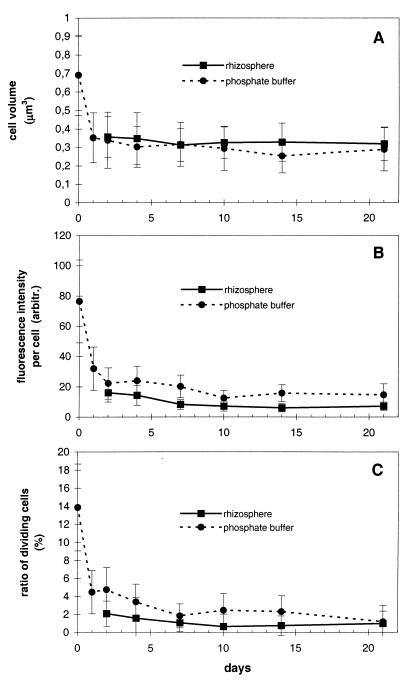

As a complement to the analysis of viability and culturability of the inoculant, we determined three growth-related parameters. The cell volume, GFP fluorescence intensity, and ratio of dividing cells to total cells of DR54-BN14 in the rhizosphere samples were reduced to 52, 21, and 15%, respectively, of the inoculum values after 2 days (P < 0.0001) and then declined slowly until day 21 (Fig. 4). The three activity parameters did not vary significantly (P > 0.05) between different regions of the root (lower, middle, upper, rhizoplane, and rhizosphere soil), and these measurements were similar (P > 0.05) to those obtained for cells in a starved culture (Fig. 4). Thus, DR54-BN14 cells extracted from the rhizosphere had properties characteristic of growth-arrested cells: the majority of the cells were small and almost coccoid, a morphology that we also observed by CLSM and that is typical of starving pseudomonads (13, 18). Analogous results were obtained by Marschner and Crowley (22), who used a ribosomal-promoter-driven lux reporter to conclude that, although the activity of P. fluorescens 2-79 was higher in the rhizosphere than in bulk soil, the cells in the rhizosphere were subject to moderate to severe starvation.

FIG. 4.

Cell volume (A), GFP fluorescence intensity (B), and ratio of dividing cells to total cells (C) of P. fluorescens DR54-BN14 in barley rhizosphere and in phosphate buffer. Error bars, SD of 200 to 500 cells. In panel C, SD is calculated from the binomial distribution.

Hence, we conclude that in the present experiments (i) the majority of DR54-BN14 cells in the rhizosphere have properties similar to those of starved cells, while a minor part of the population is active, and (ii) the majority of the DR54-BN14 population maintains culturability or viability.

Factors affecting the culturability and viability of P. fluorescens DR54-BN14 in the barley rhizosphere.

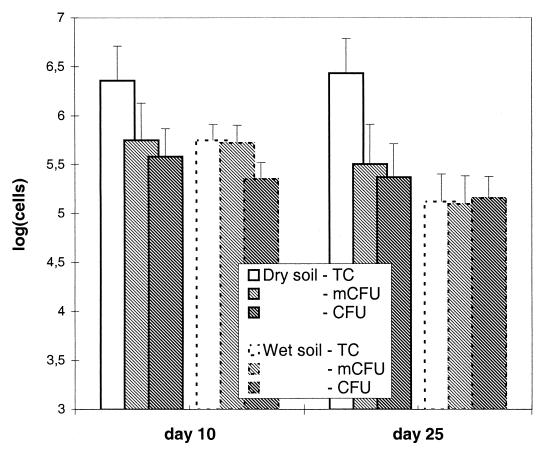

The water content of the soil had a dramatic impact on the persistence of P. fluorescens DR54-BN14 in the rhizosphere (Fig. 5). In dry soil (<10% of WHC) total counts remained constant, while total cell numbers were reduced in wet soil (ca. 160% of WHC), as previously seen under standard conditions (ca. 80% of WHC [Fig. 3]). Although the total population was constant, the proportion of nonviable cells was significantly higher (P < 0.0001) in dry soil than in wet soil (88% nonviable cells in dry soil and 5% in wet soil at day 25 [Fig. 5]).

FIG. 5.

The effect of soil humidity on the number of total cells (TC), microcolonies (mCFU), and culturable cells (CFU) of P. fluorescens DR54-BN14 on barley roots. Due to large differences in root weight between wet and dry soil samples, cell counts are given per root system and not per gram of root as in Fig. 1 and 3. Error bars, SD of triplicate samples.

In general, a low water content of the soil can influence bacterial survival and metabolic state negatively, as osmotic stress and/or matric stress can be imposed on the resident cells (30, 31). Hence, these types of stress may be responsible for the reduced viability of DR54-BN14 in the dry soil. Previous studies have shown that desiccation affects soil bacteria differentially and has the potential to reduce viability and induce the VBNC state in, e.g., Enterobacter and Alcaligenes (now Ralstonia) strains (3, 27). Because the activity of protozoans is limited in dry soil (6), our observation of a stable DR54-BN14 total cell number in dry soil may be explained by reduced predation pressure.

Decaying roots were obtained by defoliating the barley plants at day 17. For as many as 14 days after defoliation, the total count, mCFU, and CFU values for DR54-BN14 on decaying roots were similar (P > 0.05) to the values obtained for DR54-BN14 on roots of intact plants (data not shown). Contrasting observations have been made by Johnsen (17), who observed a significant increase in CFU of fluorescent pseudomonads during the first week of degradation of barley roots. Also, Troxler et al. (35) found improved survival of P. fluorescens CHA0 around decaying maize roots. However, our results indicated that decaying roots do not represent a favorable environment for DR54-BN14.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

B.N. and N.B.H. were supported by a grant from The Ministry of Environment and Energy, and O.N. was supported by a grant from The Danish Environmental Research Programme (Centre for Effects and Risks of Biotechnology in Agriculture).

We thank Søren Molin and his colleagues at the Technical University of Denmark for supplying the modified pUT vector and for providing facilities for CLSM. Jan Sørensen at the Royal Veterinary and Agricultural University kindly provided P. fluorescens DR54, and we acknowledge the technical assistance of Bente Hansen at the National Environmental Research Institute.

REFERENCES

- 1.Binnerup S J, Jensen D F, Thordal-Christensen H, Sørensen J. Detection of viable but non-culturable Pseudomonas fluorescens DF57 in soil using a microcolony epifluorescence technique. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1993;12:97–105. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bloemberg G V, O’Toole G A, Lugtenberg B J, Kolter R. Green fluorescent protein as a marker for Pseudomonas spp. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4543–4551. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.11.4543-4551.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen M, Alexander M. Survival of soil bacteria during prolonged desiccation. Soil Biol Biochem. 1973;5:213–221. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chin-A-Woeng T F C, de Priester W, van der Bij A J, Lugtenberg B J. Description of the colonization of a gnotobiotic tomato rhizosphere by Pseudomonas fluorescens biocontrol strain WCS365, using scanning electron microscopy. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1997;10:79–86. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cormack B P, Valdivia R H, Falkow S. FACS-optimized mutants of the green fluorescent protein (GFP) Gene. 1996;173:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00685-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cowling A J. Protozoan distribution and adaption. In: Darbyshire J F, editor. Soil protozoa. Oxon, United Kingdom: CAB International; 1994. pp. 5–42. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dandurand L M, Schotzko D J, Knudsen G R. Spatial patterns of rhizoplane populations of Pseudomonas fluorescens. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3211–3217. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.8.3211-3217.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Leij F A A M, Sutton E J, Whipps J M, Lynch J M. Spread and survival of a genetically modified Pseudomonas aureofaciens in the phytosphere of wheat and in soil. Appl Soil Ecol. 1994;1:207–218. [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Lorenzo V, Timmis K N. Analysis and construction of stable phenotypes in Gram-negative bacteria with Tn5- and Tn10-derived mini-transposons. Methods Enzymol. 1994;235:386–405. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)35157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Weger L A, van der Bij A J, Dekkers L C, Simons M, Wijffelman C A, Lugtenberg B J J. Colonization of the rhizosphere of crop plants by plant-beneficial pseudomonads. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1995;17:221–228. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dowling D N, O’Gara F. Metabolites of Pseudomonas involved in the biocontrol of plant disease. Trends Biotechnol. 1994;12:133–141. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dunne C, Delany I, Fenton A, O’Gara F. Mechanisms involved in biocontrol by microbial inoculants. Agronomie. 1996;16:721–729. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Givskov M, Eberl L, Møller S, Poulsen L K, Molin S. Responses to nutrient starvation in Pseudomonas putida KT2442: analysis of general cross-protection, cell shape, and macromolecular content. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:7–14. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.1.7-14.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gould W D, Hagedorn C, Bardinelli T R, Zablotowicz R M. New selective media for enumeration and recovery of fluorescent pseudomonads from various habitats. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1985;49:28–32. doi: 10.1128/aem.49.1.28-32.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hansen M, Kragelund L, Nybroe O, Sørensen J. Early colonization of barley roots by Pseudomonas fluorescens studied by immunofluorescence technique and confocal laser scanning microscopy. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1997;23:353–360. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hareland W A, Crawford R L, Chapman P J, Daley S. Metabolic function and properties of 4-hydroxyphenylacetic acid 1-hydroxylase from Pseudomonas acidovorans. J Bacteriol. 1975;121:272–285. doi: 10.1128/jb.121.1.272-285.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnsen K. Pseudomonas diversity in agricultural soil as influenced by pesticide application. Ph.D. thesis. Frederiksberg, Denmark: The Royal Veterinary and Agricultural University; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jørgensen F, Nybroe O, Knøchel S. Effects of starvation and osmotic stress on viability and heat resistance of Pseudomonas fluorescens AH9. J Appl Bacteriol. 1994;77:340–347. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kogure K, Simidu U, Taga N. A tentative direct microscopic method for counting living marine bacteria. Can J Microbiol. 1979;25:415–420. doi: 10.1139/m79-063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kragelund L, Hosbond C, Nybroe O. Distribution of metabolic activity and phosphate starvation response of lux-tagged Pseudomonas fluorescens reporter bacteria in the barley rhizosphere. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4920–4928. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.12.4920-4928.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kragelund L, Nybroe O. Competition between Pseudomonas fluorescens Ag1 and Alcaligenes eutrophus JMP134 (pJP4) during colonization of barley roots. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1996;20:41–51. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marschner P, Crowley D E. Physiological activity of a bioluminescent Pseudomonas fluorescens (strain 2-79) in the rhizosphere of mycorrhizal and non-mycorrhizal pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) Soil Biol Biochem. 1996;28:869–876. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Møller S, Kristensen C S, Poulsen L K, Carstensen J M, Molin S. Bacterial growth on surfaces: automated image analysis for quantification of growth rate-related parameters. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:741–748. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.2.741-748.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nielsen M N, Sørensen J, Fels J, Pedersen H C. Secondary metabolite- and endochitinase-dependent antagonism toward plant-pathogenic microfungi of Pseudomonas fluorescens isolates from sugar beet rhizosphere. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:3563–3569. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.10.3563-3569.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Normander B, Christensen B B, Molin S, Kroer N. Effect of bacterial distribution and activity on conjugal gene transfer on the phylloplane of the bush bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:1902–1909. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.5.1902-1909.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pedersen J C, Jacobsen C S. Fate of Enterobacter cloacae JP120 and Alcaligenes eutrophus AEO106(pRO101) in soil during water stress: effects on culturability and viability. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:1560–1564. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.5.1560-1564.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pierson E A, Wood D W, Cannon J A, Blachere F M, Pierson L S. Interpopulation signaling via N-acyl-homoserine lactones among bacteria in the wheat rhizosphere. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1998;11:1078–1084. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Postgate J R, Crumpton J E, Hunter J R. The measurement of bacterial viabilities by slide culture. J Gen Microbiol. 1961;24:15–24. doi: 10.1099/00221287-24-1-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Potts M. Desiccation tolerance of prokaryotes. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:755–805. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.4.755-805.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scott E M, Rattray E A S, Prosser J I, Killham K, Glover L A, Lynch J M, Bazin M J. A mathematical model for dispersal of bacterial inoculants colonizing the wheat rhizosphere. Soil Biol Biochem. 1995;27:1307–1318. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seldin L, Rosado A S, da Cruz D W, Nobrega A, van Elsas J D, Paiva E. Comparison of Paenibacillus azotofixans strains isolated from rhizoplane, rhizosphere, and non-root-associated soil from maize planted in two different Brazilian soils. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:3860–3868. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.10.3860-3868.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Söderberg K H, Bååth E. Bacterial activity along a young barley root measured by the thymidine and leucine incorporation techniques. Soil Biol Biochem. 1998;30:1239–1268. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Troxler J, Zala M, Moënne-Loccoz Y, Keel C, Défago G. Predominance of nonculturable cells of the biocontrol strain Pseudomonas fluorescens CHA0 in the surface horizon of large outdoor lysimeters. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3776–3782. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.10.3776-3782.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Troxler J, Zala M, Natsch A, Moënne-Loccoz Y, Defago G. Autecology of the biocontrol strain Pseudomonas fluorescens CHA0 in the rhizosphere and inside roots at later stages of plant development. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1997;24:119–130. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Peer R, Punte H L M, de Weger L A, Schippers B. Characterization of root surface and endorhizosphere pseudomonads in relation to their colonization of roots. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:2462–2470. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.8.2462-2470.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weller D M. Biological control of soilborne plant pathogens in the rhizosphere with bacteria. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1988;26:379–407. [Google Scholar]