Abstract

Complete (Ba-L) and truncated (Ba-S) forms of α-amylases from Bacillus subtilis X-23 were purified, and the amino- and carboxyl-terminal amino acid sequences of Ba-L and Ba-S were determined. The amino acid sequence deduced from the nucleotide sequence of the α-amylase gene indicated that Ba-S was produced from Ba-L by truncation of the 186 amino acid residues at the carboxyl-terminal region. The results of genomic Southern analysis and Western analysis suggested that the two enzymes originated from the same α-amylase gene and that truncation of Ba-L to Ba-S occurred during the cultivation of B. subtilis X-23 cells. Although the primary structure of Ba-S was approximately 28% shorter than that of Ba-L, the two enzyme forms had the same enzymatic characteristics (molar catalytic activity, amylolytic pattern, transglycosylation ability, effect of pH on stability and activity, optimum temperature, and raw starch-binding ability), except that the thermal stability of Ba-S was higher than that of Ba-L. An analysis of the secondary structure as well as the predicted three-dimensional structure of Ba-S showed that Ba-S retained all of the necessary domains (domains A, B, and C) which were most likely to be required for functionality as α-amylase.

The primary structures of a wide variety of amylolytic enzymes have recently been reported, and based on this information, the sequences and structures of these enzymes at the domain level have been studied (19). Taka-amylase A (TAA; an α-amylase [EC 3.2.1.1] from Aspergillus oryzae), a typical starch-hydrolyzing enzyme, consists of three domains (domains A, B, and C) (6, 41). Catalytic domain A contains an amino-terminal (β/α)8-barrel structure, followed by a domain consisting of antiparallel β-strands (domain C). A smaller domain (domain B) is present as a loop between the third β-strand and the third α-helix of the (β/α)8-barrel. In addition to these three domains, some α-amylases, such as α-amylase from Streptomyces limosus (αSli) (37) and maltotetraohydrolase from Pseudomonas saccharophila (G4α) (61), have an extra domain (domain E) at their carboxyl-terminal region which is known to play a role in raw starch adsorption. Considering that the primary structure of TAA is smaller than those of other starch-degrading enzymes, such as αSli, cyclodextrin glucanotransferase (CGTase [EC 2.4.1.19]) (12, 22, 24), branching enzyme (EC 2.4.1.18) (2), and neopullulanase (EC 3.2.1.135) (26), it is likely that all three of these domains of TAA are essential for functionality as α-amylase.

Carboxyl-terminal truncation has been observed on α-amylases of Bacillus subtilis (59), Pseudomonas stutzeri (42), and barley (49), while artificial truncation has been performed on various amylolytic enzymes, such as α-amylases of B. subtilis (38), Bacillus sp. (36), Bacillus stearothermophilus (58), Aspergillus kawachii (20), and Cryptococcus sp. (13); CGTases of Bacillus macerans, Bacillus circulans (11), and alkalophilic Bacillus (23); α-amylase-pullulanase (EC 3.2.1.1/41) of alkaliphilic Bacillus sp. (54); glucoamylase of Aspergillus awamori var. kawachi (48); and β-amylase of barley (60). As far as α-amylase is concerned, the experimental data show that most of the carboxyl-terminal-truncated enzymes retain the same level of amylolytic activity as the original (36, 42, 49, 59), while some truncations have been reported to affect the thermostability of the enzymes (38, 42, 58). However, there has been no report of an active α-amylase in which more than 25% of the carboxyl-terminal polypeptide has been truncated.

Neopullulanase catalyzes the hydrolysis of α-1,4- and α-1,6-glucosidic linkages, as well as transglycosylation, to form α-1,4- and α-1,6-glucosidic linkages (29, 56). The replacement of several amino acid residues that comprised the active center of the enzyme proved that one active center of the enzyme participated in all four of the reactions described above (32). This work suggested that in addition to the fact that the structures of α-amylase, pullulanase (EC 3.2.1.41)/isoamylase (EC 3.2.1.68), CGTase, and branching enzyme were similar, their catalytic mechanisms may also be similar (56). Based on these results, an enzyme family, the α-amylase family, was established and this includes enzymes that catalyze hydrolysis and transglycosylation at α-1,4- and α-1,6-glucosidic linkages (25, 28, 51, 56). It must be emphasized that all of the members of the α-amylase family have related catalytic (β/α)8-barrels (domain A) with a small domain (domain B) protruding between the third β-strand and the third α-helix (18, 31, 51).

B. subtilis X-23 produces a unique α-amylase which strongly induces transglycosylation in hydroquinone and kojic acid (43). We found two α-amylases (designated Ba-S and Ba-L in this paper), both of which have almost the same capacity for hydrolysis and transglycosylation. In this report, we describe when and how Ba-S is produced and compare the characteristics of these two enzymes. The structural implications based on an analysis of the secondary structure and the predicted three-dimensional (3-D) structure of Ba-S are also discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

B. subtilis ANA-1 (arg-15 hsdR hsdM ΔaprA3 amyE nprE) (35) and Escherichia coli TG1 [supE hsdΔ5 thi Δ(lac-proAB)/F′(traD36 proAB+ lacIq lacZΔM15)] (47) were used as a cloning and a sequencing host, respectively. pTB522 (encoding resistance to tetracycline) (14) was used as a cloning vector, and pBluescript II SK(+) (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan) was used as a sequencing vector. B. subtilis X-23 was grown in medium containing 0.5% soluble starch, 0.5% meat extract, 0.5% polypepton, and 0.3% NaCl (pH 6.8) (43). E. coli was grown in Luria-Bertani medium (47).

Construction of a genomic DNA library and screening.

Bacillus chromosomal DNA was prepared by using Qiagen Genomic-tips (Qiagen Inc., Chatsworth, Calif.), and plasmid DNA was isolated by the alkaline lysis method (16). Isolated genomic DNA was digested with HindIII, and 3- to 8-kbp fragments were collected after size fractionation in a sucrose gradient to be ligated into the HindIII site of pTB522. The ligation mixtures were used to transform B. subtilis ANA-1 (1). The constructed genomic library was screened using a starch-azure plate (containing 1.5% agarose, 25 μg of tetracycline per ml, and 0.4% starch-azure [Sigma] on Luria-Bertani medium), on which positive clones form a halo.

Southern analysis.

DNA fragments separated by agarose gel (0.7%) electrophoresis were transblotted to a nucleic acid transfer membrane (Amersham, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom), and the digoxigenin high-prime DNA labeling and detection system (Boehringer Mannheim) was used for DNA hybridization (50).

Nucleotide sequencing and computer analysis.

Nucleotide sequencing of genomic DNA inserted into pBluescript II SK(+) was performed by constructing a nested set of deletions with exonuclease III and mung bean nuclease and then sequencing the deletions with a dRhodamine Terminator Cycle Sequencing System (Applied Biosystems, Foster, Calif.). Sequence data were analyzed with GENETYX-MAC (Software Development Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

Assay and purification of enzyme.

α-Amylase activity was assayed based on the 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid method, as described previously (15). The reaction mixture (200 μl) consisted of 0.5% soluble starch (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) in 20 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.5) and the enzyme. The reaction was stopped after 10 min of incubation at 55°C by the addition of 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid reagent (200 μl). The reagent was prepared by mixing 0.4 M NaOH, 22 mM 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid, and 1.1 M potassium sodium (+)-tartrate tetrahydrate. One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that released 1 μmol of reducing sugar as glucose per min under the assay conditions described above. Purification of α-amylase from B. subtilis X-23 was performed as described previously (43).

SDS-PAGE and Western analysis.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was performed on 8 to 16% gradient polyacrylamide gels, and immunoblotting was carried out by using a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore, Yonezawa, Japan) with a Semi-Dry Electrophoretic Transfer Cell (Bio-Rad). Rabbit antiserum raised against Ba-L was used as a primary antibody. The antigen-antibody complex was detected by using anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G–alkaline phosphatase (Boehringer Mannheim) with BCIP (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate) reagent (Boehringer Mannheim).

Chromatography of hydrolysis products.

Soluble starch was digested with purified α-amylase (Ba-L or Ba-S) at 37°C for various durations of incubation. Samples were taken and boiled for 10 min to stop the reaction, and 10-μl aliquots were spotted on Toyo no. 50 filter paper. Paper chromatography was carried out in the ascending mode with a solvent mixture of n-butanol-pyridine-water (6:4:3 [vol/vol/vol]) as described previously (30). Sugars on the paper were detected by the silver nitrate dip method (45).

Measurement of transglycosylation activity against hydrolysis activity by high-performance liquid chromatography analysis.

The reaction mixture (100 μl) consisted of 80 mM 4-nitrophenyl α-d-maltotrioside (G3-PNP), 50 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.5), and the enzyme. After an appropriate incubation period at 37°C, 10-μl samples were collected and the reaction was stopped by adding glacial acetic acid (20 μl). For the analysis of the transglycosylation reaction to hydroquinone, 1% hydroquinone was added to the reaction mixture. The substrate, hydrolysis products, and transglycosylation products were quantitatively analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (33) with a TSK-GEL oligo-PW column (7.8 by 300 mm) (Tosoh, Tokyo, Japan) combined with a UV spectrometer (A313) (39, 40). For the analysis of the transglycosylated-hydroquinone (hydroquinone glucosides), another UV spectrometer (A280) was connected in series to the detection system.

Adsorption of α-amylase on raw starch.

The desired amount of enzyme was added to a suspension of 90 mg of raw cornstarch in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) to prepare 200 μl of suspension. The mixture was allowed to sit at 25°C for 10 min and was filtered through a membrane filter (pore size, 0.45 μm). After the raw starch was washed with the same buffer, adsorption on cornstarch (ra) was measured based on the method of Iefuji et al. (13) by the following equation: ra(%) = [(A−B)/A] × 100, where A is the α-amylase activity of the original enzyme solution and B is the activity of the filtrate, including the buffer fraction used to wash the raw starch.

The adsorbed enzyme was eluted with 0.4% SDS solution, and the starch-binding ability of the enzyme was also analyzed by SDS-PAGE.

Analysis of amino- and carboxyl-terminal sequences.

The amino acid sequences of the amino and carboxyl termini of the purified Ba-L and Ba-S were determined by an HP241 N/C Protein Sequencer System (Hewlett-Packard) by using isothiocyanate reagents for carboxyl-terminal amino acid sequence analysis (3, 4).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence for the α-amylase gene of B. subtilis X-23 was deposited in the DDBJ, EMBL, and GenBank databases under accession no. AB015592.

RESULTS

Purification of α-amylase from B. subtilis X-23.

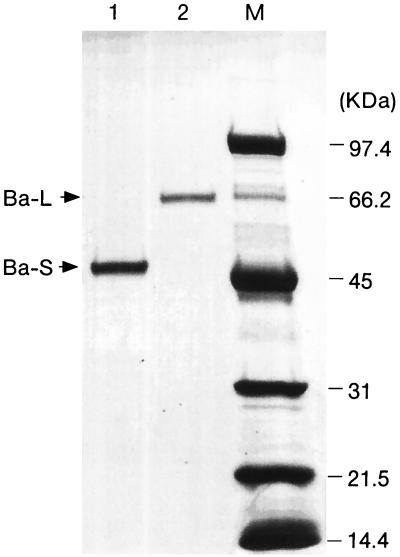

The purification steps are summarized in Table 1. The enzyme was eluted from a Q-Sepharose column as a single active peak and from a subsequent phenyl-Sepharose column as double active peaks (peaks a and b). The fractions corresponding to the two peaks were separated and further purified with a Superdex 75 column to show single bands by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1). The molecular masses of the two purified enzymes deduced from Fig. 1 were 47 and 67 kDa, and these enzymes were designated Ba-S and Ba-L, respectively. The specific activities of Ba-S and Ba-L were 514 and 362 U/mg, respectively, and the two enzymes exhibited almost identical specific activities when enzyme activity was evaluated on a molar basis (24.2 U/nmol [Ba-S] and 24.4 U/nmol [Ba-L]).

TABLE 1.

Summary of purification of the α-amylase from B. subtilis X-23a

| Column | Total activity (U) | Protein (mg) | Specific activity (U/mg) | Recovery (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (NH4)2SO4(ppt) | 1,986 | 72.2 | 3.4 | 100 |

| Q-Sepharose | 1,043 | 25.1 | 41.5 | 52.5 |

| Phenyl-Sepharoseb | ||||

| Peak a | 109 | 0.34 | 320 | 5.5 |

| Peak b | 485 | 2.16 | 225 | 24.4 |

| Total | 29.9 | |||

| Superdex 75 | ||||

| Peak a | 87.4 | 0.17 | 514 | 4.4 |

| Peak b | 387 | 1.07 | 362 | 19.5 |

| Total | 23.9 |

The initial culture volume was 3,500 ml.

The activity was detected as two peaks in the phenyl-Sepharose elution.

FIG. 1.

SDS-PAGE of purified Ba-S and Ba-L. Five micrograms of Ba-S and 2 μg of Ba-L were loaded onto an SDS-polyacrylamide gel, electrophoresed, and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. Lanes: 1, Ba-S; 2, Ba-L; M, molecular size markers.

Cloning, nucleotide sequencing, and Southern analysis.

The α-amylase gene from B. subtilis X-23 was cloned by using B. subtilis ANA-1 as a host. The clone carrying the plasmid pXA1 (composed of a vector pTB522 and a 6.8-kbp HindIII fragment from the B. subtilis X-23 genome) formed a clear halo on a starch-azure plate, indicating that the starch-degrading ability was associated with the recombinant plasmid. Using deletion analysis, we confirmed that the 2.3-kbp HindIII-SacI fragment contained the entire coding region for the α-amylase gene of B. subtilis X-23. The nucleotide sequence of the 2.3-kbp HindIII-SacI fragment was determined. A single open reading frame composed of 1,977 nucleotides (659 amino acid residues; molecular weight, 72,279) was found. Four regions that are highly conserved in enzymes in the α-amylase family (26, 56) were present in the deduced amino acid sequence (see Fig. 4). Genomic Southern analysis was performed by using a 1.7-kbp EcoRI-PvuI DNA fragment which contains most of the α-amylase gene of B. subtilis X-23 as a probe. The genomic DNA was digested with various restriction enzymes that had no restriction sites within the α-amylase gene, and the digests were subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis. The probe hybridized with only one DNA fragment from each DNA digestion, indicating that there is only one copy of the α-amylase gene in the genomic DNA of B. subtilis X-23.

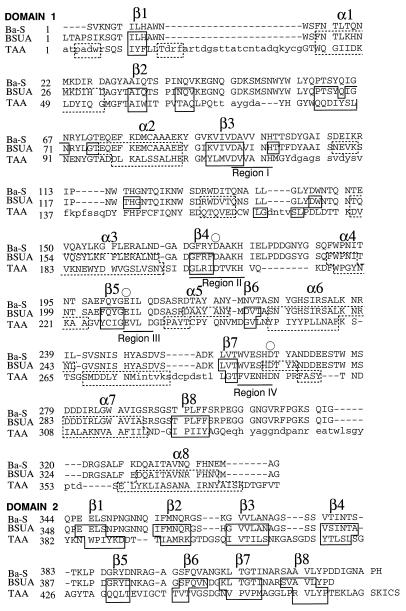

FIG. 4.

Topological alignment of Ba-S, BSUA (9), and TAA (53). The topological alignment and data regarding the secondary structure are based on a previous work (9). An amino-terminal (β/α)8-barrel (domain A) and a loop (domain B) between the third β-strand and the third helix of the (β/α)8-barrel are indicated as domain 1. β-Strands folded in a Greek-key motif (domain C) are domain 2. Small letters in the alignment indicate topologically unpaired residues. Residues that belong to α-helices and β-strands are surrounded by dotted and solid boxes, respectively. The catalytic residues are represented by an open circle. Only the secondary structures of the (β/α)8-barrel and β-sandwich structures are designated. Four regions (I, II, III, and IV) that are highly conserved in the α-amylase family (26, 56) are underlined.

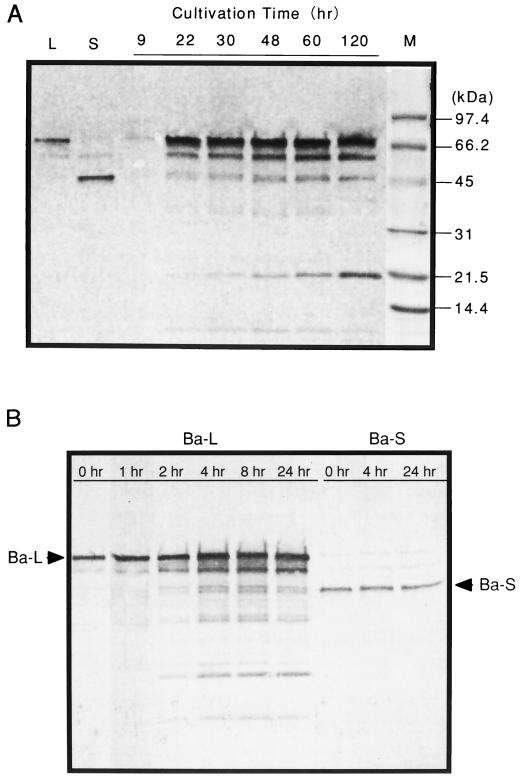

Western analysis.

Western analysis was performed to confirm immunologically that Ba-S was produced from Ba-L. As shown in Fig. 2A, signals of both Ba-S and Ba-L were detected after 22 h of cultivation. The Ba-S signal became stronger as the duration of the cultivation period increased and was accompanied by a polypeptide signal of about 20 kDa. Purified Ba-L was converted to Ba-S by the 22-h culture supernatant of B. subtilis X-23, whereas purified Ba-S was not digested even after 24 h of incubation with this culture supernatant (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Western immunoblot analysis of Ba-L and Ba-S. (A) Lanes L and S indicate purified Ba-L and Ba-S, respectively. Three microliters of culture supernatant taken at various time points in cultivation was applied. The marker lane (M) was separated before transblotting and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. (B) The purified Ba-L or Ba-S (30 or 22 μg, respectively, in 150 μl of distilled water) was incubated at 37°C with 75 μl of the 22-h culture supernatant of B. subtilis X-23 and 5 μl of toluene. After various periods of time, aliquots (30 μl) were removed and treated at 100°C for 10 min. Each reaction mixture (0.075 μl) was individually subjected to SDS-PAGE.

Amino- and carboxyl-terminal amino acid sequences of Ba-L and Ba-S.

The amino-terminal amino acid sequences of Ba-L and Ba-S were determined, and these sequences were identical: Ser-Val-Lys-Asn-Gly-Thr-Ile-Leu-His. The same sequence was deduced from the nucleotide sequence of the B. subtilis X-23 α-amylase gene. Therefore, the 45 amino-terminal amino acid residues are the signal peptide that is removed during the secretion process. The carboxyl-terminal amino acid sequence of Ba-L was Leu-Pro-His, and that of Ba-S was Ala-Pro-His. The former sequence was deduced from the nucleotide sequence at the carboxyl terminus, and the latter was deduced at the 186 amino acid residues upstream from the carboxyl terminus. Considering these results together with the molecular masses of Ba-L and Ba-S estimated by SDS-PAGE (67 and 47 kDa, respectively [Fig. 1]), we concluded that the carboxyl termini of Ba-L and Ba-S were His-614 and His-428, respectively. The deduced molecular weights of mature Ba-L and Ba-S proteins calculated from their amino acid sequences were 67,445 and 47,227, respectively.

Comparison of the characteristics of Ba-L and Ba-S. (i) Amylolytic pattern.

Soluble starch was hydrolyzed with Ba-L and Ba-S, and the products were analyzed by paper chromatography (data not shown). Both enzyme forms efficiently hydrolyzed starch to produce glucose, maltose, and O-α-d-glucopyranosyl-(1-6)-α-d-glucopyranosyl-(1-4)-d-glucopyranose as the final products. There were no differences between Ba-L and Ba-S with regard to their pattern of action on soluble starch.

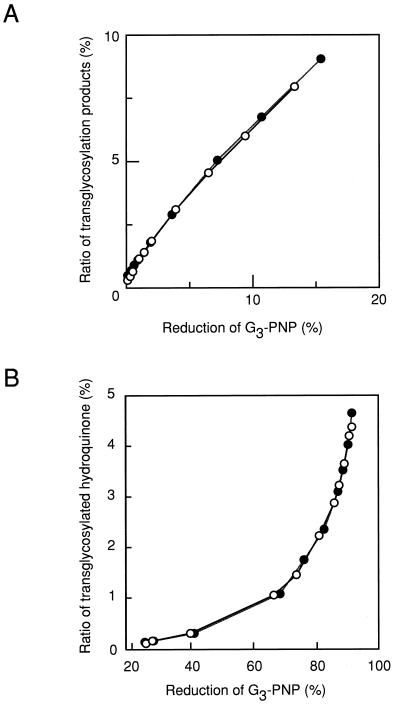

(ii) Transglycosylation of glucosyl residues of G3-PNP to Gn-PNP and hydroquinone.

Hydrolysis and transglycosylation products were measured simultaneously in the same reaction mixtures. Figure 3A shows a plot of the transglycosylation products, i.e., 4-nitrophenyl α-d-maltotetraoside (G4-PNP), 4-nitrophenyl α-d-maltopentaoside (G5-PNP), 4-nitrophenyl α-d-maltohexaoside (G6-PNP), 4-nitrophenyl α-d-maltoheptaoside (G7-PNP), and 4-nitrophenyl α-d-maltooctaoside (G8-PNP), against reduction of the substrate (G3-PNP). There were no differences between the reactions of Ba-L and Ba-S. Figure 3B is a plot of the transglycosylation products with hydroquinone as an acceptor, i.e., hydroquinone glucoside (HQ-G1), hydroquinone maltoside (HQ-G2), hydroquinone trioside (HQ-G3), and hydroquinone tetraoside (HQ-G4), against reduction of the donor substrate (G3-PNP). Again, there was no difference between the reactions of Ba-L and Ba-S.

FIG. 3.

Comparison of the transglycosylation abilities of Ba-L (○) and Ba-S (●). (A) The ratio of transglycosylation products, i.e., G4-PNP, G5-PNP, G6-PNP, G7-PNP, and G8-PNP, against reduction of the substrate (G3-PNP). (B) The ratio of transglycosylated hydroquinone, i.e., HQ-G1, HQ-G2, HQ-G3, and HQ-G4, against the reduction of the substrate (G3-PNP).

(iii) Effects of pH and temperature on enzyme activity and stability.

The optimum pHs for Ba-L and Ba-S activities were the same (pH 5.5), and both enzyme forms were stable from pH 5.5 to 10.0 (data not shown). Although the optimum temperature for enzyme activity was 65°C for both Ba-L and Ba-S, the relative activities of Ba-S at 70, 75, and 80°C were slightly higher than those of Ba-L. The activity of Ba-S that remained after treatment at 65°C for 10 min was about 60%, whereas that of Ba-L was about 30% (data not shown).

(iv) Binding ability to raw starch.

Some amylolytic enzymes have been reported to be able to bind to or digest raw starch (5, 7, 8, 10, 13, 17, 21, 44, 46, 57), and all of them have putative raw starch-binding motifs at their carboxyl-terminal region (52), except that Rhizopus sp. glucoamylase has one at its amino-terminal region (55). Therefore, we examined the raw starch-binding abilities of Ba-L and Ba-S by using TAA as a negative control and α-amylase from a porcine pancreas as a positive control (13). Neither Ba-L, Ba-S, nor TAA was adsorbed to raw starch, whereas more than 75% of porcine pancreas activity was adsorbed to raw starch. In this context, the carboxyl-terminal region of Ba-L does not contain a putative raw starch-binding motif (52) (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

We found two enzymatically active peaks during the purification of B. subtilis X-23 α-amylase with a phenyl-Sepharose column (Table 1) and purified both of the enzymes (Ba-S and Ba-L). The amino- and carboxyl-terminal amino acid sequences of these enzymes were determined by a protein sequencer. Based on the following experimental results, we concluded that Ba-L and Ba-S were produced from the same α-amylase gene and that Ba-S arose from Ba-L by the processing of its carboxyl-terminal region during the cultivation of B. subtilis X-23. (i) The amino-terminal sequences of Ba-L and Ba-S were identical, and the carboxyl-terminal sequence of Ba-S was seen in the Ba-L sequence (Ala-426, Pro-427, and His-428) at a point that encoded a polypeptide with a molecular weight of 47,227, which is the same as the molecular mass of Ba-S (47 kDa [Fig. 1]) estimated by SDS-PAGE. (ii) Genomic Southern analysis of B. subtilis X-23 indicated that there was only one copy of the α-amylase gene. (iii) In Western analysis with an antibody raised against Ba-L, the signal of Ba-S became stronger along with that of a 20-kDa polypeptide, which is most likely the truncated carboxyl-terminal part of Ba-L, during the cultivation of B. subtilis X-23 (Fig. 2A). In Fig. 2A, an unidentified signal can be seen between those for Ba-S and Ba-L. No α-amylase activity could be detected in any purification steps, except for those of Ba-L and Ba-S. Therefore, this unidentified immunologically active protein might also be produced from Ba-L by amino- or carboxyl-terminal truncation but was not obtained during purification because it was not enzymatically active or its activity was below the level of detection. The signal at about 20 kDa in Fig. 2A, which based on its size is most likely a fragment caused by the protease digestion of Ba-L, was stronger than expected. One possible explanation is that the specificity of the antibody raised against Ba-L might be greater for the carboxyl-terminal region of Ba-L than for its amino-terminal region. Our conclusion was further confirmed by digesting purified Ba-L and Ba-S with the 22-h culture supernatant of B. subtilis X-23 (Fig. 2B). Purified Ba-L was converted to Ba-S by this culture supernatant, whereas purified Ba-S was not digested even after 24 h. Although two signals, which migrated at nearly the same rate as that of Ba-S, are visible in the first half of Fig. 2B, it is obvious that one of these signals corresponds to Ba-S.

There were essentially no differences between Ba-S and Ba-L with regard to amylolytic pattern, transglycosylation ability, optimum pH, pH stability, optimum temperature, or raw starch adsorption. However, Ba-S was more thermostable than Ba-L. The compact structure of Ba-S might increase its thermostability. It is intriguing that there are essentially no differences between these two enzyme forms, one of which is 186 amino acids shorter than the other. Vihinen et al. (58) concluded that truncation of the 32 carboxyl-terminal amino acids of B. stearothermophilus α-amylase enhanced its thermal stability and affected the end product profile. Marco et al. (38) deleted the 171 carboxyl-terminal amino acids of B. subtilis α-amylase and replaced them with 33 amino acids during the cloning procedure, and the resultant α-amylase showed considerably enhanced thermostability. Since the characteristics of Ba-S were essentially the same as those of Ba-L, we concluded that the extra 186 carboxyl-terminal amino acids of Ba-L were not necessary for the functionality of the α-amylase. Although the 3-D structure of this extra carboxyl-terminal region is still unknown, we speculate that this region forms a domain without affecting the folding of the whole enzyme and that proteases secreted by B. subtilis X-23 into the medium could attack native Ba-L to give Ba-S, as reported for the thermostable and alkaliphilic α-amylase-pullulanase from Bacillus sp. strain XAL601 (54).

Although the amino acid sequence homology between TAA and B. subtilis N7 α-amylase (BSUA) (9) is 22.3%, the secondary structures of their catalytic domains (domains A, B, and C), from the beginning of the (β/α)8-barrel to the end of the β-strands, are in good agreement (Fig. 4), and their 3-D structures are similar over the entire main chain. On the other hand, Ba-S and BSUA are highly homologous (88.5%). Therefore, it is most likely that the 3-D structure of Ba-S is similar to that of BSUA. In this context, the 3-D structure of Ba-S was predicted by computer-aided molecular modeling (27) based on the X-ray crystal structure of BSUA (9) (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Stereoview of the predicted structure of Ba-S from the side of the (β/α)8-barrel. Molecular modeling of Ba-S was performed based on the 3-D structure of BSUA complexed with maltopentaose (9) by using Discover-Insight II software (version 4.3; Molecular Simulation Inc.) on an ONYX2 workstation (Silicon Graphics, Inc.). Residues 422 to 428 are not shown since the corresponding structure for BSUA could not be determined because of disorder (9). The main chains of domains A and B (residues 1 to 343) are indicated by an orange ribbon, and domain C (residues 344 to 421) is indicated by a green ribbon. Red cylinders and yellow arrows represent α-helices and β-strands, respectively. The carboxyl terminus of Ba-S is shown by a blue arrow.

According to this molecular model, the carboxyl terminus of Ba-S is located opposite the catalytic cleft (Fig. 5). We also analyzed the hydropathy profile (34) of the 186 carboxyl-terminal amino acid residues of Ba-L. There is no expansion of the hydrophobic region, which is often seen in membrane-spanning regions of some membrane-intrinsic proteins. Therefore, the extra carboxyl-terminal polypeptide of Ba-L may not be a long-stretched structure that reaches the catalytic cleft, but it may form a normal globular structure without having direct interactions with the catalytic center.

Our data strongly suggest that the truncated α-amylase, Ba-S, folds correctly and independently to function as an α-amylase with or without the extra carboxyl-terminal region. The Ba-S protein might show compact folding since carboxypeptidase Y did not digest native Ba-S protein (data not shown), although there were no specific amino acid sequences that carboxypeptidase Y did not digest at the carboxyl-terminal region of Ba-S.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We express our sincere thanks to T. Imanaka of Kyoto University for providing pTB522 and the host strain B. subtilis ANA-1. We also thank T. Nishimura, T. Takaha, and H. Takata for their helpful discussions.

This work was supported in part by a grant for the development of a next-generation bioreactor system from the Society for Techno-Innovation of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries (STAFF).

REFERENCES

- 1.Anagnostopoulos C, Spizizen J. Requirements for transformation in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1961;81:741–746. doi: 10.1128/jb.81.5.741-746.1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baecker P A, Greenberg E, Preiss J. Biosynthesis of bacterial glycogen: primary structure of Escherichia coli 1,4-α-D-glucan:1,4-α-D-glucan 6-α-D-(1,4-α-D-glucano)-transferase as deduced from the nucleotide sequence of the glgB gene. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:8738–8743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bailey J M, Nikfarjam F, Shenoy N R, Shively J E. Automated carboxy-terminal sequence analysis of peptides and proteins using diphenyl phosphoroisothiocyanatidate. Protein Sci. 1992;12:1622–1633. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560011210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bailey J M, Tu O, Issai G, Ha A, Shively J E. Automated carboxy-terminal sequence analysis of polypeptides containing C-terminal proline. Anal Biochem. 1995;224:588–596. doi: 10.1006/abio.1995.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Belshaw N, Williamson G. Production and purification of a granular-starch-binding domain of glucoamylase 1 from Aspergillus niger. FEBS Lett. 1990;269:350–353. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81191-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boel E, Brady L, Brzozowski A, Derewenda Z, Dodson G, Jensen V, Petersen S, Swift H, Thim L, Woldike H. Calcium binding in α-amylases: an X-ray diffraction study at 2.1-Å resolution of two enzymes from Aspergillus. Biochemistry. 1990;29:6244–6249. doi: 10.1021/bi00478a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chatterjee B, Ghosh A, Das A. Starch digestion and adsorption by β-amylase of Emericella nidulans (Aspergillus nidulans) J Appl Bacteriol. 1992;72:208–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1992.tb01825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dalmia B, Schütte K, Nikolv Z. Domain E of Bacillus macerans cyclodextrin glucanotransferase: an independent starch-binding domain. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1995;47:575–584. doi: 10.1002/bit.260470510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fujimoto Z, Takase K, Doui N, Momma M, Matsumoto T, Mizuno H. Crystal structure of a catalytic-site mutant α-amylase from Bacillus subtilis complexed with maltopentaose. J Mol Biol. 1998;277:393–407. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fukuda K, Teramoto Y, Goto M, Sakamoto J, Mitsuiki S, Hayashida S. Specific inhibition by cyclodextrins of raw starch digestion by fungal glucoamylase. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1992;56:556–559. doi: 10.1271/bbb.56.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hellman J, Wahlberg M, Karp M, Korpela T, Mäntsälä P. Effects of modifications at the C-terminus of cyclomaltodextrin glucanotransferase from Bacillus circulans var. alkalophilus on catalytic activity. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 1990;12:387–396. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hofmann B E, Bender H, Schulz G E. Three-dimensional structure of cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase from Bacillus circulans at 3.4 Å resolution. J Mol Biol. 1989;209:793–800. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90607-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iefuji H, Chino M, Kato M, Iimura Y. Raw-starch-digesting and thermostable α-amylase from the yeast Cryptococcus sp. S-2: purification, characterization, cloning and sequencing. Biochem J. 1996;318:989–996. doi: 10.1042/bj3180989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Imanaka T, Himeno T, Abia S. Effect of in vitro DNA rearrangement in the NH2-terminal region of the penicillinase gene from Bacillus licheniformis on the mode of expression in Bacillus subtilis. J Gen Microbiol. 1985;131:1753–1763. doi: 10.1099/00221287-131-7-1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Imanaka T, Kuriki T. Pattern of action of Bacillus stearothermophilus neopullulanase on pullulan. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:369–374. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.1.369-374.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ish-Horowicz D, Burke J F. Rapid and efficient cosmid cloning. Nucleic Acids Res. 1981;14:8605–8613. doi: 10.1093/nar/9.13.2989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Itkor P, Tsukagoshi N, Udaka S. Nucleotide sequence of the raw-starch-digesting amylase gene from Bacillus sp. B1018 and its strong homology to the cyclodextrin glucanotransferase genes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;166:630–636. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)90855-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Janecek S, Svensson B, Henrissat B. Domain evolution in the α-amylase family. J Mol Evol. 1997;45:322–331. doi: 10.1007/pl00006236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jespersen H M, MacGregor E A, Sierks M R, Svensson B. Comparison of the domain-level organization of starch hydrolases and related enzymes. Biochem J. 1991;280:51–55. doi: 10.1042/bj2800051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaneko A, Sudo S, Takayasu-Sakamoto Y, Tamura G, Ishikawa T, Oba T. Molecular cloning and determination of the nucleotide sequence of a gene encoding an acid-stable α-amylase from Aspergillus kawachii. J Ferment Bioeng. 1996;81:292–298. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim C, Sata H, Taniguchi H, Maruyama Y. Cloning and expression of raw-starch-digesting α-amylase gene from Bacillus circulans F-2 in Escherichia coli. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1990;1048:223–230. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(90)90060-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kimura K, Kataoka S, Ishii Y, Takano T, Yamane K. Nucleotide sequence of the β-cyclodextrin glucanotransferase gene of alkalophilic Bacillus sp. strain 1011 and similarity of its amino acid sequence to those of α-amylases. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:4399–4402. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.9.4399-4402.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kimura K, Kataoka S, Nakamura A, Takano T, Kobayashi S, Yamane K. Functions of the COOH-terminal region of cyclodextrin glucanotransferase of alkalophilic Bacillus sp. #1011: relation to catalyzing activity and pH stability. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;161:1273–1279. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)91380-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klein C, Schulz G E. Structure of cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase refined at 2.0 Å resolution. J Mol Biol. 1991;217:737–750. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90530-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuriki T. Can protein engineering interconvert glucanohydrolases/glucanotransferases, and their specificities? Trends Glycosci Glycotechnol. 1992;4:567–572. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuriki T, Imanaka T. Nucleotide sequence of the neopullulanase gene from Bacillus stearothermophilus. J Gen Microbiol. 1989;135:1521–1528. doi: 10.1099/00221287-135-6-1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuriki T, Kaneko H, Yanase M, Takata H, Shimada J, Handa S, Takada T, Umeyama H, Okada S. Controlling substrate preference and transglycosylation activity of neopullulanase by manipulating steric constraint and hydrophobicity in active center. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:17321–17329. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.29.17321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuriki T, Okada S. Amylase Research Society of Japan (ed.) 1995. A new concept of the criteria for classification of various amylolytic enzymes and related enzymes; similarities in specificities and structures; pp. 87–92. Enzyme chemistry and molecular biology of amylases and related enzymes. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Fla. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuriki T, Okada S, Imanaka T. New type of pullulanase from Bacillus stearothermophilus and molecular cloning and expression of the gene in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:1554–1559. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.4.1554-1559.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuriki T, Park J-H, Okada S, Imanaka T. Purification and characterization of thermostable pullulanase from Bacillus stearothermophilus and molecular cloning and expression of the gene in Bacillus subtilis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:2881–2883. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.11.2881-2883.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuriki T, Stewart D C, Preiss J. Construction of chimeric enzymes I and II: activity and properties. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:28999–29004. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.46.28999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuriki T, Takata H, Okada S, Imanaka T. Analysis of active center of Bacillus stearothermophilus neopullulanase. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:6147–6152. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.19.6147-6152.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuriki T, Yanase M, Takata H, Takesada Y, Imanaka T, Okada S. A new way of producing isomalto-oligosaccharide syrup by using the transglycosylation reaction of neopullulanase. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:953–959. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.4.953-959.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kyte J, Doolittle R F. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J Mol Biol. 1982;157:105–132. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee S, Morikawa M, Takagi M, Imanaka T. Cloning of the aapT gene and characterization of its product, α-amylase-pullulanase (AapT), from thermophilic and alkaliphilic Bacillus sp. strain XAL601. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:3764–3773. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.10.3764-3773.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin L L, Hsu W H, Chu W S. A gene encoding for an α-amylase from thermophilic Bacillus sp. strain TS-23 and its expression in Escherichia coli. J Appl Microbiol. 1997;82:325–334. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1997.00364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Long C M, Virolle M J, Chang S, Bibb M J. α-Amylase gene of Streptomyces limosus: nucleotide sequence, expression motifs, and amino acid sequence homology to mammalian and invertebrate α-amylases. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:5745–5754. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.12.5745-5754.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marco J L, Bataus L A, Valência F F, Ulhoa C J, Astolfi-Filho S, Felix C R. Purification and characterization of a truncated Bacillus subtilis α-amylase produced by Escherichia coli. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1996;44:746–752. doi: 10.1007/BF00178613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matsui I, Ishikawa K, Miyairi S, Fukui S, Honda K. An increase in the transglycosylation activity of Saccharomycopsis α-amylase altered by site-directed mutagenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1077:416–419. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(91)90560-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matsui I, Svensson B. Improved activity and modulated action pattern obtained by random mutagenesis at the fourth β-α loop involved in substrate binding to the catalytic (β/α)8-barrel domain of barley α-amylase 1. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:22456–22463. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.36.22456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matsuura Y, Kusunoki M, Harada W, Kakudo M. Structure and possible catalytic residues of Taka-amylase A. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1984;95:697–702. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a134659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakada T, Kubota M, Sakai S, Tsujisaka Y. Purification and characterization of two forms of maltotetraose-forming amylase from Pseudomonas stutzeri. Agric Biol Chem. 1990;54:737–743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nishimura T, Kometani T, Takii H, Terada Y, Okada S. Purification and some properties of α-amylase from Bacillus subtilis X-23 that glucosylates phenolic compounds such as hydroquinone. J Ferment Bioeng. 1994;78:31–36. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Penninga D, van der Veen B, Knegtel R, van Hijum S, Rozeboom H, Kalk K, Dijkstra B, Dijkhuizen L. The raw starch binding domain of cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase from Bacillus circulans strain 251. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:32777–32784. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.51.32777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Robyt J, French D. Action pattern and specificity of an amylase from Bacillus subtilis. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1963;100:451–467. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(63)90112-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saha B, Lecureux L, Zeikus J. Raw starch adsorption-desorption purification of a thermostable β-amylase from Clostridium thermosulfurogenes. Anal Biochem. 1988;175:569–572. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(88)90585-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Semimaru T, Goto M, Furukawa K, Hayashida S. Functional analysis of the threonine-rich and serine-rich Gp-I domain of glucoamylase I from Aspergillus awamori var. kawachi. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2885–2890. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.8.2885-2890.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Søgaard M, Olsen F L, Svensson B. C-terminal processing of barley α-amylase 1 in malt, aleurone protoplasts, and yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:8140–8144. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.18.8140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Southern E M. Detection of specific sequences among DNA fragments separated by gel electrophoresis. J Mol Biol. 1975;98:503–517. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(75)80083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Svensson B. Protein engineering in the α-amylase family: catalytic mechanism, substrate specificity, and stability. Plant Mol Biol. 1994;25:141–157. doi: 10.1007/BF00023233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Svensson B, Jespersen H, Sierks M R, MacGregor E A. Sequence homology between putative raw-starch binding domains from different starch-degrading enzymes. Biochem J. 1989;264:309–311. doi: 10.1042/bj2640309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Swift H J, Brady L, Derewenda Z S, Dodson E J, Dodson G G, Turkenburg J P, Wilkinson A J. Structure and molecular model refinement of Aspergillus oryzae (TAKA) α-amylase; an application of the simulated-annealing method. Acta Crystallogr B. 1991;47:535–544. doi: 10.1107/s0108768191001970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Takagi M, Lee S, Imanaka T. Diversity in size and alkaliphily of thermostable α-amylase-pullulanases (AapT) produced by recombinant Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis and the wild-type Bacillus sp. J Ferment Bioeng. 1996;81:557–559. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Takahashi T, Kato K, Ikegami Y, Irie M. Different behavior towards raw starch of three forms of glucoamylase from a Rhizopus sp. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1985;98:663–671. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a135323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Takata H, Kuriki T, Okada S, Takesada Y, Iizuka M, Minamiura N, Imanaka T. Action of neopullulanase: neopullulanase catalyzes both hydrolysis and transglycosylation at α-(1→4)- and α-(1→6)- glucosidic linkages. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:18447–18452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tanaka Y, Ashikari T, Nakamura N, Kiuchi N, Shibano Y, Amachi T, Yoshizumi H. Glucoamylase produced by Rhizopus and by a recombinant yeast containing the Rhizopus glucoamylase gene. Agric Biol Chem. 1986;50:1737–1742. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vihinen M, Peltonen T, Iitiä A, Suominen I, Mäntsälä P. C-terminal truncations of a thermostable Bacillus stearothermophilus α-amylase. Protein Eng. 1994;7:1255–1259. doi: 10.1093/protein/7.10.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yamane K, Hirata Y, Furusato T, Yamazaki H, Nakayama A. Changes in the properties and molecular weights of Bacillus subtilis M-type and N-type α-amylases resulting from a spontaneous deletion. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1984;96:1849–1858. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a135019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yoshigi N, Sahara H, Koshino S. Role of the C-terminal region of β-amylase from barley. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1995;117:63–67. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhou J H, Baba T, Takano T, Kobayashi S, Arai Y. Nucleotide sequence of the maltotetraohydrolase gene from Pseudomonas saccharophila. FEBS Lett. 1989;255:37–41. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81056-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]