Abstract

The extracellular matrix (ECM) of the meniscus is a gel-like water solution of proteoglycans embedding bundles of collagen fibers mainly oriented circumferentially. Collagen fibers significantly contribute to meniscal mechanics, however little is known about their mechanical properties.

The objective of this study was to propose a constitutive model for collagen fibers embedded in the ECM of the meniscus and to characterize the tissue’s pertinent mechanical properties. It was hypothesized that a linear fiber reinforced viscoelastic constitutive model is suitable to describe meniscal mechanical behavior in shear. It was further hypothesized that the mechanical properties governing the model depend on the tissue’s composition.

Frequency sweep tests were conducted on eight porcine meniscal specimens. A first cohort of experimental data resulted from tissue specimens where collagen fibers oriented parallel with respect to the shear plane were used. This was done to eliminate the contribution of collagen fibers from the mechanical response and characterize the mechanical properties of the ECM. A second cohort with fibers orthogonally oriented with respect to the shear plane that were used to determine the elastic properties of the collagen fibers via inverse finite element analysis.

Our testing protocol revealed that tissue ECM mechanical behavior could be described by a generalized Maxwell model with 3 relaxation times. The inverse finite element analysis suggested that collagen fibers can be modeled as linear elastic elements having an average elastic modulus of 287.5±62.6 MPa. Magnitudes of the mechanical parameters governing the ECM and fibers were negatively related to tissue water content.

Keywords: viscoelasticity, frequency sweep, rheological modeling, water content, inverse finite element analysis, collagen fibers

Graphical Abstract

1. INTRODUCTION

The knee is the main weight bearing joint in the human body and its stability is linked to its complex structure consisting of bones, muscles, ligaments, articular cartilage and menisci (Pena et al., 2006). In particular, the menisci play a crucial role in ensuring congruity between the femoral and tibial surfaces, and bearing and transferring load within the joint, thus protecting articular cartilage degradation (Athanasiou & Sanchez-Adams, 2009; Hsieh & Walker, 1976; Kurosawa et al., 1980; Meakin et al., 2003; Pena et al., 2006; Shrive et al., 1978; Walker & Erkman, 1975). Mechanical performance of the meniscus results from a combination of its unique C-shape and its complex microstructural organization and composition (Bullough et al., 1970; Chevrier et al., 2009; Fithian et al., 1990; Makris et al., 2011). The extracellular matrix (ECM) of the tissue is composed of a gel-like water solution of proteoglycans and ions embedded within collagen type I and II fibers (Athanasiou & Sanchez-Adams, 2009; Chevrier et al., 2009). Specifically, collagen is organized in large fiber bundles aligned along the circumferential direction in concert with fibers aligned in the radial direction (Bullough et al., 1970; Chevrier et al., 2009). Several biomechanical studies have shown that the circumferential fibers provide significant contribution to both tensile (Tissakht & Ahmed, 1995) and torsional (Abraham et al., 2011; Anderson et al., 1991; Nguyen & Levenston, 2012; Norberg et al., 2021; Zhu et al., 1994) tissue properties. To our knowledge, few studies (Anderson et al., 1991; Zhu et al., 1994) have modeled the viscoelastic mechanical response of the meniscal tissue undergoing dynamic shear tests. Likewise, few studies investigated the mechanical contribution of the collagen fibers in the meniscus based on elongation tests and volume fractions of ECM components (Peloquin et al., 2016; Tissakht & Ahmed, 1995). The paucity of data on fiber mechanical properties is partly due to the challenges of identifying, quantitatively, the mechanical contribution of the fibers while they are embedded within the ECM. However, further quantitative knowledge of collagen fiber mechanical properties is critical to developing realistic computational models of the meniscus which, in turn, would help understanding meniscal pathophysiology and developing treatment strategies.

Herein, we utilized a novel inverse finite element analysis approach to determine the elastic properties of circumferential collagen fibers. First, mechanical tests were conducted on porcine meniscal explants while finite element models simulating the actual mechanical tests were also developed. The resultant constitutive equations and material properties of the meniscal tissue used in the computational models (including those of the fibers) were modulated to have the results of the simulations matching those of the experiments.

Mechanical tests were conducted in torsion. This approach was motivated by the fact that shear forces are a relevant component of the mechanical loads the meniscus experiences under normal physiological loading (Athanasiou & Sanchez-Adams, 2009). In addition, torsion loading does not cause changes in volume of the tested specimens. This greatly simplifies the determination of mechanical properties given that the tissue’s response is purely viscoelastic (Anderson et al., 1991; Norberg et al., 2021; Travascio et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 1994). Accordingly, the poroelastic phenomena associated with interstitial fluid redistribution (Ateshian et al., 1997; LeRoux & Setton, 2002; Morejon et al., 2021; Mow et al., 1980; Seitz et al., 2013) due to volume changes can be neglected.

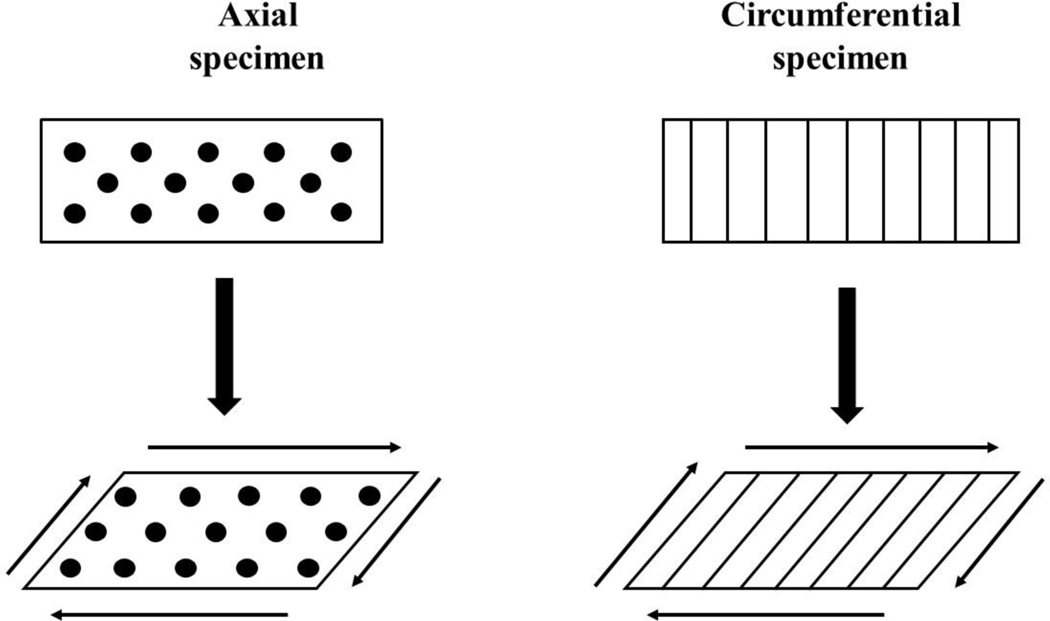

Two types of specimens were used for mechanical testing: those including circumferential fibers oriented in the plane of rotation (axial specimens), and those whose fibers were oriented orthogonally to the plane of rotation (circumferential specimens). When torque is applied to axial specimens, collagen fibers shear relative to each other not contributing to the mechanical response of the sample. In contrast, in circumferential samples, collagen fibers stretch under torque, and contribute to the overall shear stiffness of the specimen (Abraham et al., 2011; Norberg et al., 2021; Travascio et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 1994), see Figure 1. Therefore, testing on axial samples was conducted to study the exclusive response of the ECM of the tissue to shear, and to characterize pertinent mechanical parameters. In contrast, tests on circumferential specimens were carried out to observe the combined mechanical response of the ECM and the fibers, and to characterize the mechanical properties of the latter.

Figure 1:

Contribution of circumferential fibers to meniscal mechanical behavior in pure shear. When shear is applied to axial samples, collagen fibers (black dots) slide with respect to each other, without contributing to the overall shear stiffness of the tissue. When shear is applied to circumferential samples, collagen fibers (vertical lines) stretch and increase to overall stiffness of the specimen.

Based on previous studies (Anderson et al., 1991; Coluccino et al., 2017; Gaugler et al., 2015; Moyer et al., 2012; Murphy et al., 2019; Pereira et al., 2014; Sanchez-Adams et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 1994) and our own preliminary observations, it was hypothesized that the mechanical behavior of the meniscal ECM could be described by a generalized Maxwell model (Tschoegl, 2012). Since mechanical tests in torsion would only produce small elongations of the circumferential collagen fibers, their mechanical behavior was hypothesized to be described by a linear elastic constitutive equation. Finally, as suggested by research on meniscal shear mechanics (Norberg et al., 2021; Travascio et al., 2020), it was further hypothesized that the mechanical properties of both the ECM and the fibers would be related to the tissue’s composition.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Specimen Preparation:

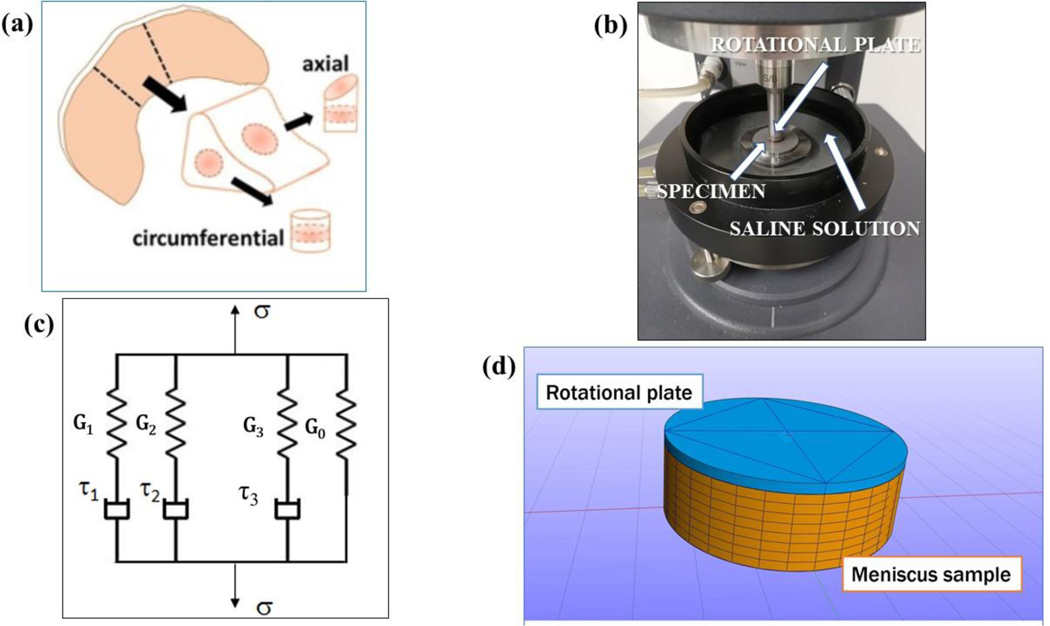

Eight porcine lateral menisci (n = 8) were obtained from a local abattoir. Tissues were visually inspected to determine their degenerative status, which was deemed to be normal. All samples were harvested from the central region of the meniscus, see Figure 2a. Specifically, tissue wedges were dissected from the midbody and punched with a 5 mm diameter corneal trephine to obtain cylindrical cores with either axial or circumferential orientations. A Compresstome® (VF-210–0Z, Precisionary Instruments, Inc., Natick, MA) was used to cut the specimens to ~1.5 mm height. All specimens were obtained from the deep region of the tissue, far from the superficial or lamellar portions. For each meniscus, 1 sample per tissue orientation (axial and circumferential) was prepared. Each specimen was visually inspected to make sure that no visible superficial damages were present. All the specimens were preserved and tested in a protease inhibited (Complete Tablets, Roche, Basel, SWI) 1X phosphate buffered saline (PBS) solution (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

Figure 2:

(a) Schematic of specimen preparation. From each meniscus (n = 8), one axial and one circumferential oriented sample were prepared; (b) Setup of the rotational rheometer: the rotating plate, the location of the specimen and the saline solution in the chamber are indicated; (c) Schematic representation of the generalized Maxwell model for viscoelasticity with 3 relaxation times; (d) finite element model used for the computational analysis: the rotating plate of the rheometer and the meniscus sample are shown.

2.2. Mechanical Testing:

Shear properties were measured with a rotational rheometer (AR-G2, TA Instruments, New Castle, DE) following a previously reported experimental protocol (Norberg et al., 2021). Specifically, the rheometer was fitted with an 8 mm sandblasted flat steel rotational plate geometry and a 40mm sandblasted flat fixed steel plate. To ensure no slip conditions between the specimen and plates, 150 grit sandpaper was adhered onto both plates. To ensure contact between the sample and the plates, the rotational plate was lowered until reaching a threshold normal force of 0.1N. After initial contact was made, the sample was completely immersed in a protease inhibited 1X PBS solution maintained at 37°C, see Figure 2b.

Frequency sweep tests, including 21 logarithmically spaced frequencies ranging from 0.05 to 5 Hz, were carried out to measure the dynamic shear properties of both axial and circumferential samples. For each test, the magnitude of applied shear was γ ≈ 0.2%. Previous studies indicated that this magnitude is appropriate in order to test the shear behavior of meniscal samples within a linear viscoelastic range (Norberg et al., 2021). Based on previous experimental protocols (Norberg et al., 2021; Zhu et al., 1994) and our own observations, specimens were allowed to equilibrate for 30 minutes before testing. All experimental data were collected and post-processed via TA Rheology Advantage™ Data Analysis software v5.5.24 to yield, for each frequency investigated, the torque (T), the phase angle (δ) and the associated complex modulus (G*). Moreover, for the axial specimens only, data were further post-processed (TRIOS v5.3, TA Instruments, New Castle, DE) to yield viscoelastic parameters including the elastic component at equilibrium (Go), relaxation times (τi) and viscoelastic coefficients (γi) of the generalized Maxwell model (Tschoegl, 2012) (see Figure 2c) best fitting the experimental data. Specifically, generalized Maxwell models with 2, 3 and 4 relaxation times were investigated, and the goodness of the datafit was evaluated in terms of R2.

2.3. Theoretical Modeling of the Meniscus Tissue:

The meniscus was modeled as a fiber-reinforced viscoelastic matrix. The viscoelastic behavior of the matrix was modeled as a generalized Maxwell model with a discrete spectrum of relaxation times. More specifically, the second Piola-Kirchhoff stress tensor (S) associated to the solid matrix was expressed as follows (Puso & Weiss, 1998):

| (1) |

In the above equation, Se is the elastic stress, and the relaxation function G(t) was given by:

| (2) |

where τi are the relaxation times, and γi are the viscoelastic coefficients of the generalized Maxwell model.

The elastic constitutive model of the tissue matrix was defined as neo-Hookean, whose hyper-elastic strain-energy function (W) was defined as (Criscione et al., 2000):

| (3) |

where K1 and K2 are the first and second invariants of the left natural strain tensor, while μ and k were the shear and bulk modulus, respectively.

Fibers were homogeneously distributed within the tissue matrix, all oriented in the circumferential direction of the meniscus. Since mechanical tests of torsion would produce small elongation of the fibers in the circumferential samples, their mechanical behavior was hypothesized to be linear elastic. This was done by choosing, as constitutive equation, an exponential-power law, whose strain energy density (ψ) is given by (Maas et al., 2020):

| (4) |

where the coefficients ξ,α and β must satisfy the following constrains:

| (5) |

In equation (4), given the constraints of relations (5), the coefficient ξ represents the linear elastic modulus of the fibers, whose value was determined via inverse finite element analysis (see below).

2.4. Computational analysis:

Finite element models representative of axial and circumferential samples were developed via FEBio Studio v1.2.0 (University of Utah) to simulate the frequency sweep experiments conducted with the rheometer. More specifically, the computational domain included a cylindrical meniscus sample (1.5mm height and 2.5mm radius) in contact with the rotational plate of the rheometer, see Figure 2d. The plate was modeled as a rigid body, and the contact between the sample and the plate was assumed to be rigid. The bottom of the sample was fixed in all six degrees of freedom while the rigid plate was fixed in all the degrees of freedom but the rotational axis of the rheometer (z-axis). Aimed at reproducing the experimental conditions of the rheological tests, in each simulation, the plate rotated to produce 21 sinusoidal cycles with the same amplitude and frequencies used in the experiments. A preliminary mesh convergence study determined that 1536 hex8 (8-node hexahedral) elements were sufficient to discretize the meniscus sample and yield a relative error of 10−3 in the measure of the torque at the rotating plate (data not shown).

The computational analysis was carried out in two steps: validation of the model’s predictions and an inverse finite element analysis to determine the mechanical properties of meniscal fibers. For the model validation, the experimental values of torque, measured in axial meniscal samples across a frequency sweep, were compared to those attained in the computer simulations. A total of 8 simulations (one for each meniscal axial sample) were carried out. In each simulation, the magnitudes of the parameters G0, γi and τi implemented in the computational model were taken from the values experimentally measured for that particular axial sample. It should be noted that, in axial samples, the collagen fibers are oriented in the plane of rotation and do not contribute to the reaction torque at the plate of the rheometer. Accordingly, since the magnitude of ξ does not affect the simulations, its value implemented in the model was arbitrary.

The second step was carried out to determine the elastic properties of the fibers. The experimental data obtained from tests on the circumferential samples were curve-fitted with the numerical solutions provided by the finite element models to yield the modulus ξ. Since each pair axial and circumferential samples was obtained from the same tissue region, it was assumed their composition, as well as their mechanical properties, were the same. Therefore, the parameters G0, γi and τi implemented in the computational model of each circumferential sample were taken from the values experimentally measured in the paired axial specimens. The root mean square was used as a metric to evaluated the goodness of fit of the computer simulations with the experimental data as follows:

| (6) |

where is the experimental peak torque at the i-frequency, is the average of the 21 experimental values of the peak torque and is the computational value of the peak torque calculated for the i-frequency. An RMS value larger than 0.8 was considered to indicate an adequate curve-fit of the experimental data.

2.5. Tissue Composition Measurements:

Water content in menisci samples was measured as the mass fraction with respect to the weight of the hydrated sample (wet weight). Weight measurements were conducted with an analytical scale (Model ML104, Mettler Toledo, Columbus, OH). Water content was calculated based on the following equation (Norberg et al., 2021):

| (7) |

where Wwet is the wet weight, immediately after testing, and Wdry is the ‘dry weight’ of the sample, measured after lyophilization.

2.6. Statistical Analysis:

All data were reported as mean ± standard deviation. Data normality was investigated via Anderson-Darling tests, and outliers, if any, were identified via Grubb’s tests (α = 0.05). When investigating the rheological behavior of the meniscal samples, a one-way ANOVA followed by post-hoc Tukey test was used to determine significant effects of frequency on the values of G* and δ for axial and circumferential samples, separately. For each frequency investigated, a paired t-test was used to investigate differences in G* and δ between axial and circumferential samples. For tissue composition measurements, a paired t-test was used to test the hypothesis that the difference in water content across couples of axial and circumferential samples of the same menisci was null. Simple linear regression models were used to explore possible significant empirical relations among the viscoelastic parameters Go and γi the modulus of thefibers ξ with tissue composition . A 95% level of significance was used for each test conducted (α = 0.05).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Mechanical Testing:

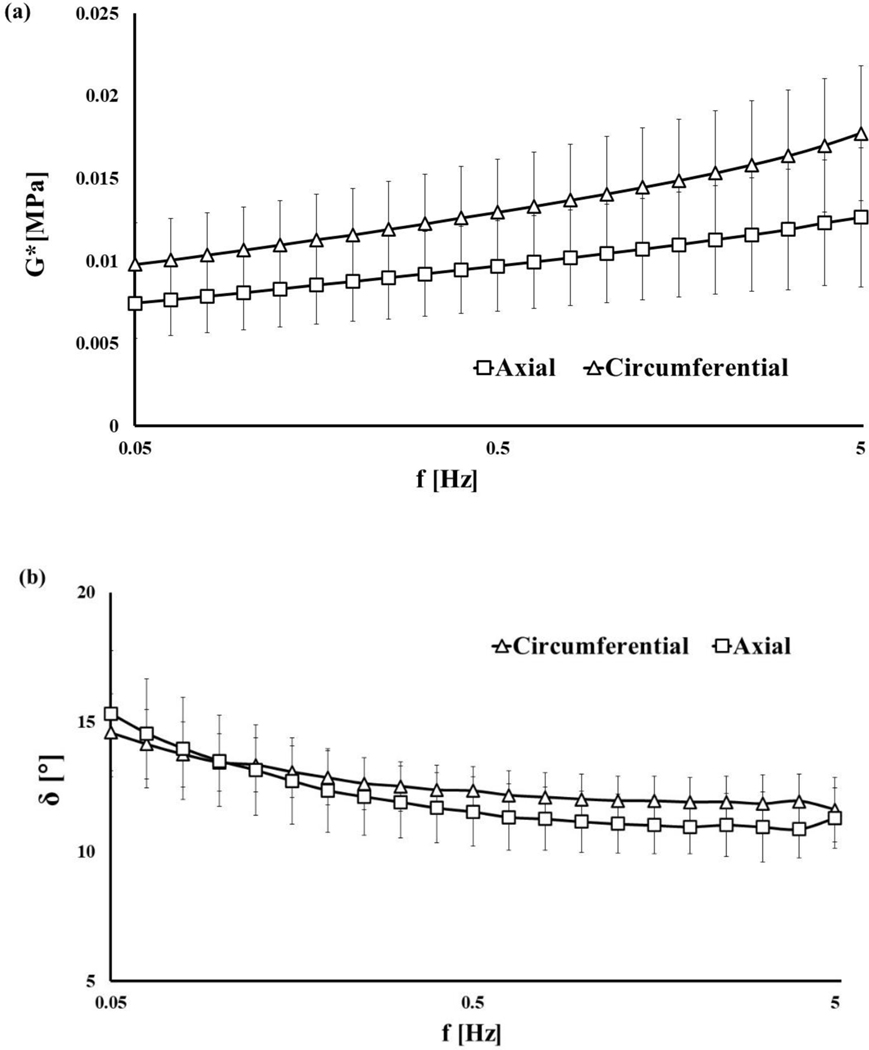

The values of G* ranged between 5.14∙10−3 to 2.21∙10−2 MPa and increased with the shear frequency (see Figure 3a). The opposite behavior was observed in the trend of the phase angle δ, reducing from 15° to 10° as the shear frequency increased (see Figure 3b). For each frequency tested, the mean value of G* associated to circumferential samples was significantly larger than that corresponding to axial ones (p<0.05). No statistical differences were observed in the mean values of δ for all the frequencies tested, with the exception of 1.6, 2 and 4 Hz where the values of the phase angles of the circumferential samples were larger than those of the axial ones (p<0.05).

Figure 3:

Dynamic shear properties of meniscal samples: (a) complex modulus G* for all the frequencies tested; (b) phase angle δ for all the frequencies tested. All the data refer to axial and circumferential oriented samples.

The accuracy of the generalized Maxwell model in describing the shear behavior of the axial samples increased with the number of relaxation times used. A model including 2-relaxation times provided R2 values below 0.75. By comparison, Maxwell models of 3- and 4-relaxation times provided R2 values above 0.9, see Table 1.

Table 1:

Agreement of dynamic shear data with generalized Maxwell models with different relaxation times.

| Relaxation times | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | 0.62±0.24 | 0.92±0.05 | 0.95±0.05 |

Based on these observations, the 3-relaxation times Maxwell model was deemed to be the most appropriate to describe the shear behavior of axial samples, as it provided an agreement with experimental data compared to that of a 4-relaxation times model, but with a lower number of experimental parameters. The mean values of G0, Gi and τi associated with the 3-relaxation times Maxwell model are reported in Table 2.

Table 2:

Parameters of the generalized Maxwell model with 3 relaxation times used to describe the dynamic shear behavior of the ECM. All the values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The symbols γi indicate the ratios Gi/G0.

| Go [MPa.10−3] | γ1 [.10−1] | γ2 [.10−1] | γ3 [.10−1] | τ1 [s.10−2] | τ2 [s.10−1] | τ3 [s] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.39 ± 0.22 | 9.04 ± 1.86 | 5.12 ± 1.17 | 6.82 ± 1.9 | 2.88 ± 0.78 | 3.05 ± 0.43 | 3.07 ± 0.53 |

3.2. Computational Analysis:

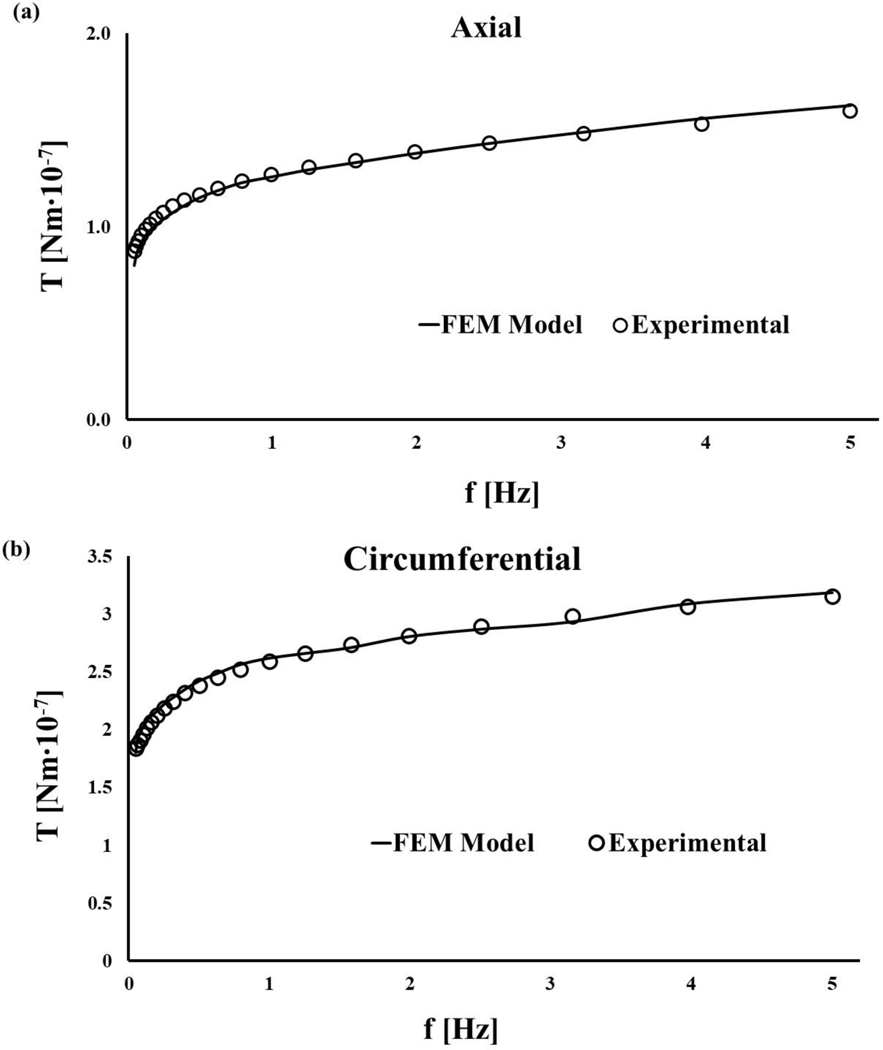

The validation of the meniscal computational model was successfully conducted: numerical solutions resulted to be in good agreement with the experimental results, providing RMS = 0.97 ± 0.02. Similarly, curve-fitting the experimental data collected on the circumferential samples with the numerical solutions obtained by modulating the value of the elastic modulus of the collagen fibers produced RMS = 0.91 ± 0.05. Representative diagrams of the curve-fittings for both axial and a circumferential sample are reported in Figure 4.

Figure 4:

Representative curve-fittings showing the agreement of the predictions of the finite element model with the experimental data: (a) data fit of an axial sample (RMS = 98.06 %); (b) data fit of an axial sample (RMS = 99.13 %).

The estimate of the value of the elastic modulus of the fibers was ξ=287.5 ± 62.6 MPa. A summary of the RMS and ξ values for each simulated case are reported in Table 3.

Table 3:

Accuracy of the finite element model in curve-fitting the experimental data on axial and circumferential samples estimated via RMS as per equation (5). The values of the curve-fitting parameter ξ representing the elastic modulus of the collagen fibers is reported.

| Sample | RMS axial | RMS circ. | ξ [MPa] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.962 | 0.900 | 200 |

| 2 | 0.996 | 0.860 | 280 |

| 3 | 0.943 | 0.813 | 280 |

| 4 | 0.981 | 0.944 | 350 |

| 5 | 0.929 | 0.970 | 180 |

| 6 | 0.975 | 0.904 | 320 |

| 7 | 0.975 | 0.991 | 330 |

| 8 | 0.972 | 0.942 | 360 |

3.3. Tissue Composition:

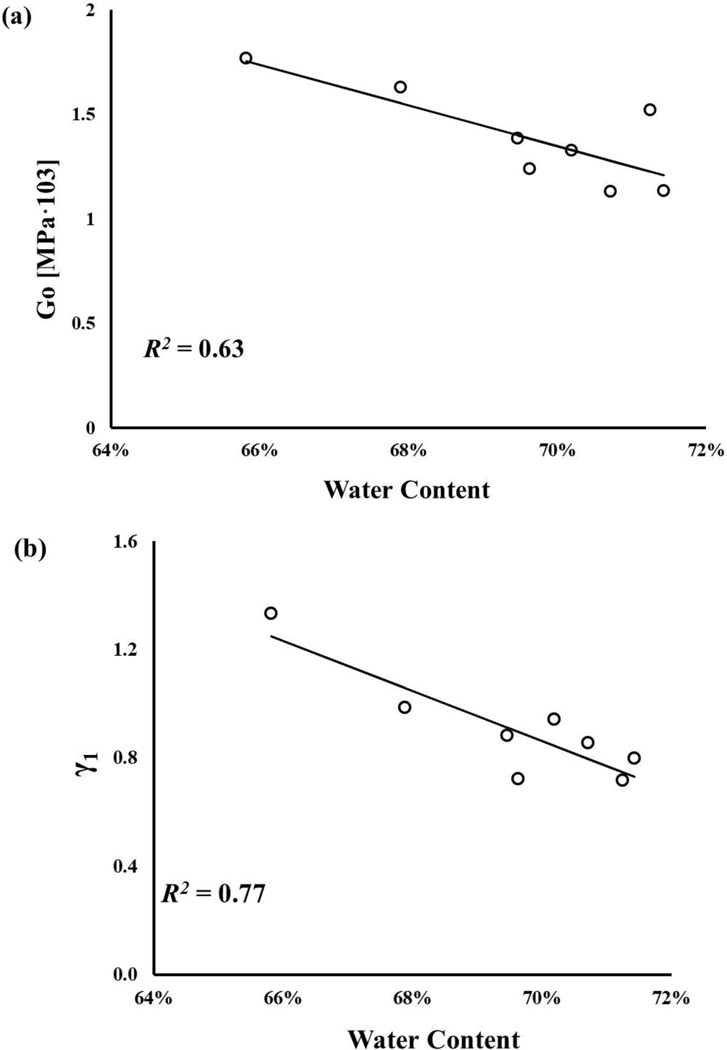

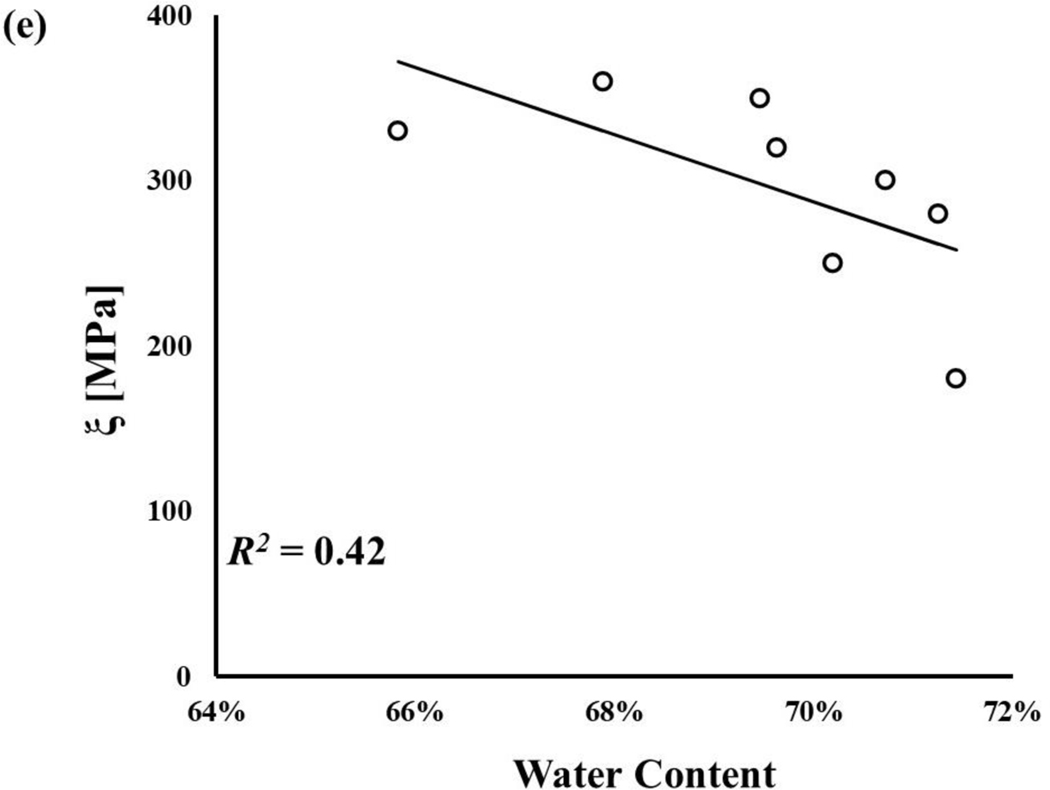

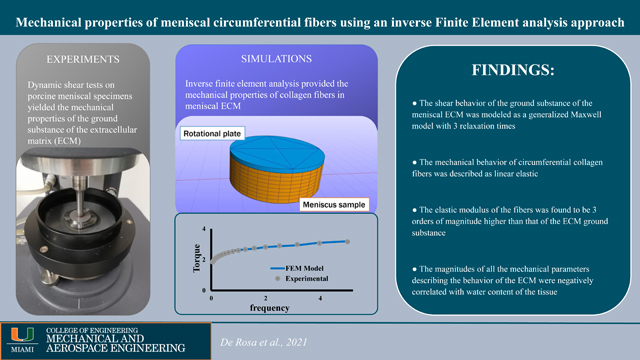

The water content of axial and circumferential samples were normally distributed, and their mean values were 68.1±3.3% and 69.5±1.8%, respectively. No statistically significant difference was observed between the axial and circumferential groups (p>0.05). Statistically significant correlations among meniscal mechanical parameters and water content were found (p < 0.05), see Figure 5. Specifically, a strong correlation was found between, and γi (R2 ~ 77–95%), see Figure 5b-d. A weaker correlation was found for Go, with R2 = 63%, see Figure 5a. The weakest relation was found between ξ and , with R2 = 42%, see Figure 5e.

Figure 5:

Meniscal mechanical properties are related to tissue water content: a) G0;b)γ1;c)γ2; d)γ3; e)ξ All the regressions reported in the figure were statistically significant (p-value < 0.05).

4. DISCUSSION

Numerous studies have been conducted to understand the complex behavior of the meniscus and to develop appropriate constitutive models to predict this behavior (Kazemi et al., 2013). Several solutions, mostly depending on the loading condition considered, have been proposed including; poroelastic (Haemer et al., 2012; Morejon et al., 2021), poro-viscoelastic (Seitz et al., 2013), porohyper-viscoelastic (Seitz et al., 2013), fibril-reinforced poro-hyper-viscoelastic (Quiroga et al., 2014), transversely isotropic biphasic linear elastic (LeRoux & Setton, 2002), transversely isotropic poro-hyperelastic (Freutel et al., 2015), and transversely isotropic poro-hyperviscoelastic (Seyfi et al., 2018). The present contribution focused on the mechanical characterization of the circumferential collagen fibers in the meniscus. Partly based on experimental evidence offered by previous studies (Anderson et al., 1991; Bursac et al., 2009; Norberg et al., 2021; Travascio et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 1994), we hypothesized: (1) in pure shear, the ECM of the meniscus behaves as a linear viscoelastic material; (2) the mechanical contribution of the collagen fibers can be accounted for by reinforcing the ECM with linear elastic fibers; (3) magnitude of the mechanical parameters governing the shear behavior of the meniscus is related to its composition. To test these hypotheses and carry out the mechanical characterization of meniscal fibers, a novel inverse finite element analysis approach was adopted. Specifically, dynamic shear tests on porcine meniscal samples were conducted on axial and circumferential meniscal samples. The experimental data from the axial samples was curve-fitted with a linear viscoelastic model to yield the mechanical parameters governing the dynamic behavior of the tissue’s ECM. Based on these results, a finite element model of the meniscus was developed and used to curve-fit the experimental data from the circumferential cohort with the ultimate goal of yielding the elastic modulus of the circumferential collagen fibers.

In agreement with previous studies (Anderson et al., 1991; Bursac et al., 2009; Norberg et al., 2021; Travascio et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 1994), the rheological tests confirmed that the meniscus is viscoelastic with a preponderant elastic component, as evidenced by the low values of δ obtained throughout the spectrum of shear frequencies investigated (see Figure 3b). The torsional stiffness of the circumferential samples was significantly higher than that observed in the axial ones (Figure 3a). This was expected in light of the considerations of the mechanical role the circumferential fibers have in torsion (see Figure 1), and the experimental results of similar studies (Anderson et al., 1991; Norberg et al., 2021; Travascio et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 1994). As a further corroboration of the results, the magnitudes of G* measured were comparable to those found for animal (Anderson et al., 1991; Travascio et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 1994) and human (Norberg et al., 2021) tissue.

We hypothesized that the mechanical behavior of the meniscal ECM could be described by a generalized Maxwell model. The results of the mechanical tests, for the range of shear frequencies explored, validate this hypothesis. Curve-fitting of frequency sweep tests on axial samples with generalized Maxwell models of 3 or 4 relaxations times provided R2 values of 0.92±0.05 and 0.95±0.05, respectively (Table1). Aimed at limiting the number of experimental parameters governing the modeling equations and preventing potential overfitting, a 3-relaxation times Maxwell model was chosen for the modeling of the ECM in the inverse finite element analysis (Table 2). Specifically, experimental data from frequency sweeps on circumferential samples were curve-fitted with the solutions of a finite element model assuming the meniscus to be a fiber reinforced viscoelastic material. This analysis considered the elastic modulus of the fibers ξ as the sole curve-fitting parameter, while the ECM mechanical parameters were taken from the curve-fitting of the experiments on the axial samples with the generalized Maxwell model. This approach was adopted assuming that, by harvesting axial and circumferential samples from meniscal tissue regions immediately adjacent to each other, the mechanical properties of their ECM would not significantly vary. This assumption was corroborated by the experimental measurements of tissue composition showing no significant water content difference between axial and circumferential samples. Also, the constitutive equation of the collagen fibers was hypothesized to be linear elastic. Such hypothesis was supported by the good agreement observed between the model predictions and the experimental data (RMS = 0.91 ± 0.06, see also Table 3), and by the fact that the magnitude of ξ was comparable to those reported for human and bovine meniscal tissue (Peloquin et al., 2016; Tissakht & Ahmed, 1995).

The average water content of both axial and circumferential samples was within the ranges typically observed in meniscal tissue (Makris et al., 2011). Also, all the measured mechanical properties were negatively related to (see Figure 5). Numerous studies have shown that values of meniscal mechanical properties decrease as water content increases (Bursac et al., 2009; Joshi et al., 1995; Morejon et al., 2021; Norberg et al., 2021; Seitz et al., 2013). During the process of tissue degeneration, water mass fraction increases (Adams et al., 1983; Herwig et al., 1984). Accordingly, the results hereby presented suggest that, with degeneration, tissue compliance increases, potentially affecting meniscal load bearing function and congruency of the knee joint.

Some limitations of this study are noted. Experiments were conducted on porcine tissue. Therefore, the results are not immediately translatable to humans. Nevertheless, both trend and magnitude of the rheological properties measured in the present experiments were similar to those observed in previous studies conducted on human samples (Norberg et al., 2021). Therefore, we do not expect major differences in the mechanical behavior of the human meniscal collagen fibers with respect to that reported herein. Due to the exploratory nature of this study, the sample size was limited to eight lateral meniscal specimens, all collected in the central portion of the tissue. Regional variations of shear properties of the meniscus have been reported (Sweigart et al., 2004). However, a complete mapping of the rheological behavior of all the regions of both medial and lateral meniscus would have been beyond the scope of the present work, which is explorative in nature, and will be addressed in a future study. Moreover, both theoretical and experimental analyses carried out in this study deliberately neglected the presence of radially oriented collagen fibers. Previous experiments on bovine menisci suggest that the contribution of radial fibers to the overall shear stiffness of the meniscus is negligible (Zhu et al., 1994). In addition, both axial and circumferential samples used in this study presented radial fibers oriented in the direction parallel to the plane of rotation. Therefore, they would not have contributed to the torsional stiffness of the samples during testing. Previous research on the relationship between meniscal shear properties and composition showed that proteoglycan and collagen content, along with water affect the mechanical properties of the tissue (Herwig et al., 1984; Makris et al., 2011; Norberg et al., 2021). Since correlation between shear properties and tissue composition was not the main interest of this study, this type of investigation was limited to water content, which previous studies indicated to be the component with the highest level of correlation to meniscal shear properties (Norberg et al., 2021). Finally, the fiber reinforced viscoelastic model proposed in this study is linear and does not take account for any interaction that may exist between the collagen fibers and the extracellular matrix of the tissue. Further studies detailing the microstructural mechanics of the tissue need to be conducted to provide a more realistic behavior of the meniscus. Nevertheless, the model proposed in this work, even if based on several simplifying assumptions, provided satisfactory agreement with the experimental data, see Figure 4.

In conclusion, this study suggests that, when investigating shear behavior, the meniscus can be conveniently assumed as a linear fiber-reinforced viscoelastic material. Pertinent mechanical properties were measured and their relationship with tissue composition indicate that meniscal degeneration may compromise the function of support to knee mechanics the meniscus has. Such information can be utilized to better understand the mechanobiology and physiology of this important tissue, to develop predictive computational mechanical models of the meniscus, as well as to design and develop meniscal replacements.

Meniscal ECM shear behavior modeled via 3-relaxation times generalized Maxwell model

Shear behavior of circumferential collagen fibers is linear elastic

Mechanical properties of fibers and ECM are inversely related to tissue water content

Acknowledgments:

The project described was supported by Grant Number 1R01AR073222 from the NIH (NIAMS).

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

5. REFERENCES

- Abraham AC, Edwards CR, Odegard GM, & Donahue TLH (2011). Regional and fiber orientation dependent shear properties and anisotropy of bovine meniscus. Journal of the mechanical behavior of biomedical materials, 4(8), 2024–2030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams ME, Billingham ME, & Muir H. (1983). The glycosaminoglycans in menisci in experimental and natural osteoarthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatism: Official Journal of the American College of Rheumatology, 26(1), 69–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson DR, Woo SLY, Kwan MK, & Gershuni DH (1991). Viscoelastic shear properties of the equine medial meniscus. Journal of orthopaedic research,, 9, 550–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ateshian GA, Warden W, Kim J, Grelsamer R, & Mow VC (1997). Finite deformation biphasic material properties of bovine articular cartilage from confined compression experiments. Journal of Biomechanics, 30(11–12), 1157–1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Athanasiou KA, & Sanchez-Adams J. (2009). Engineering the knee meniscus. . Synthesis lectures on tissue engineering, 1–97. [Google Scholar]

- Bullough PG., Munuera L., Murphy J., & Weinstein AM. (1970). The strength of the menisci of the knee as it relates to their fine structure. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume, 52(3), 564–570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bursac P, Arnoczky S, & York A. (2009). Dynamic compressive behavior of human meniscus correlates with its extra-cellular matrix composition. Biorheology, 46(3), 227–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevrier A, Nelea M, Hurtig MB, Hoemann CD, & Buschmann MD (2009). Meniscus structure in human, sheep, and rabbit for animal models of meniscus repair. Journal of orthopaedic research, 27(9), 1197–1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coluccino L, Peres C, Gottardi R, Bianchini P, Diaspro A, & Ceseracciu L. (2017). Anisotropy in the viscoelastic response of knee meniscus cartilage. Journal of applied biomaterials & functional materials, 15(1), 77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Criscione JC, Humphrey JD, Douglas AS, & Hunter WC (2000). An invariant basis for natural strain which yields orthogonal stress response terms in isotropic hyperelasticity. Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solids, 48(2), 2445–2465. [Google Scholar]

- Fithian DC, Kelly MA, & Mow VC (1990). Material properties and structure-function relationships in the menisci. Clinical orthopaedics and related research(252), 19–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freutel M, Galbusera F, Ignatius A, & Dürselen L. (2015). Material properties of individual menisci and their attachments obtained through inverse FE-analysis. Journal of Biomechanics, 48, 1343–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler M, Wirz D, Ronken S, Hafner M, Göpfert B, Friederich NF, & Elke R. (2015). Fibrous cartilage of human menisci is less shock-absorbing and energy-dissipating than hyaline cartilage. Knee surgery, sports traumatology, arthroscopy, 23(4), 1141–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haemer JM, Carter DR, & Giori NJ (2012). The low permeability of healthy meniscus and labrum limit articular cartilage consolidation and maintain fluid load support in the knee and hip. Journal of Biomechanics, 45, 1450–1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herwig J, Egner E, & Buddecke E. (1984). Chemical changes of human knee joint menisci in various stages of degeneration. Annals of the rheumatic diseases, 43(4), 635–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh H-H, & Walker P. (1976). Stabilizing mechanisms of the loaded and unloaded knee joint. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume, 58(1), 87–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi MD., Suh JK., Marui T., & Woo SLY. (1995). Interspecies variation of compressive biomechanical properties of the meniscus. Journal of biomedical materials research, 29(7), 823–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazemi M, Dabiri Y, & Li L. (2013). Recent advances in computational mechanics of the human knee joint. Computational and mathematical methods in medicine, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurosawa H, Fukubayashi T, & Nakajima H. (1980). Load-bearing mode of the knee joint: physical behavior of the knee joint with or without menisci. Clinical orthopaedics and related research(149), 283–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeRoux MA, & Setton LA (2002). Experimental and biphasic FEM determinations of the material properties and hydraulic permeability of the meniscus in tension. Journal of biomechanical engineering, 124(3), 315–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas S, Weiss J, & Ateshian G. (2020). User’s Manual Version 3.0. [Google Scholar]

- Makris EA, Hadidi P, & Athanasiou KA (2011). The knee meniscus: structure–function, pathophysiology, current repair techniques, and prospects for regeneration. Biomaterials, 32(30), 7411–7431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meakin JR, Shrive NG, Frank CB, & Hart DA (2003). Finite element analysis of the meniscus: the influence of geometry and material properties on its behaviour. The knee, 10(1), 33–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morejon A, Norberg CD, De Rosa M, Best TM, Jackson AR, & Travascio F. (2021). Compressive Properties and Hydraulic Permeability of Human Meniscus: Relationships With Tissue Structure and Composition. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 8. 10.3389/fbioe.2020.622552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mow VC, Kuei S, Lai WM, & Armstrong CG (1980). Biphasic creep and stress relaxation of articular cartilage in compression: theory and experiments. Journal of biomechanical engineering, 102(1), 73–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyer JT, Abraham AC, & Donahue TLH (2012). Nanoindentation of human meniscal surfaces. Journal of Biomechanics, 45(13), 2230–2235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CA, Cunniffe GM, Garg AK, & Collins MN (2019). Regional dependency of bovine meniscus biomechanics on the internal structure and glycosaminoglycan content. Journal of the mechanical behavior of biomedical materials, 94, 186–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen AM, & Levenston ME (2012). Comparison of osmotic swelling influences on meniscal fibrocartilage and articular cartilage tissue mechanics in compression and shear. Journal of orthopaedic research, 30, 95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norberg C., Filippone G., Andreopoulos F., Best TM., Baraga M., Jackson AR., & Travascio F. (2021). Viscoelastic and equilibrium shear properties of human meniscus: Relationships with tissue structure and composition. Journal of Biomechanics, 120, 110343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peloquin JM, Santare MH, & Elliott DM (2016). Advances in quantification of meniscus tensile mechanics including nonlinearity, yield, and failure. Journal of biomechanical engineering, 138(2), 021002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pena E, Calvo B, Martinez M, & Doblare M. (2006). A three-dimensional finite element analysis of the combined behavior of ligaments and menisci in the healthy human knee joint. Journal of Biomechanics, 39(9), 1686–1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira H, Caridade S, Frias A, Silva-Correia J, Pereira D, Cengiz I, Mano J, Oliveira JM, Espregueira-Mendes J, & Reis R. (2014). Biomechanical and cellular segmental characterization of human meniscus: building the basis for Tissue Engineering therapies. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, 22(9), 1271–1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puso MA, & Weiss JA (1998). Finite element implementation of anisotropic quasi-linear viscoelasticity using a discrete spectrum approximation. Journal of Biomechancal Engineering, 120(1), 62–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quiroga JP, Emans P, Wilson W, Ito K, & Van Donkelaar CC (2014). Should a native depth-dependent distribution of human meniscus constitutive components be considered in FEA-models of the knee joint? Journal of the mechanical behavior of biomedical materials, 38, 242–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Adams J, Wilusz RE, & Guilak F. (2013). Atomic force microscopy reveals regional variations in the micromechanical properties of the pericellular and extracellular matrices of the meniscus. Journal of orthopaedic research, 31(8), 1218–1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seitz AM, Galbusera F, Krais C, Ignatius A, & Dürselen L. (2013). Stress-relaxation response of human menisci under confined compression conditions. Journal of the mechanical behavior of biomedical materials, 26, 68–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seyf B., Fatourae N., & Imen M. (2018). Mechanical modeling and characterization of meniscus tissue using flat punch indentation and inverse finite element method. Journal of the mechanical behavior of biomedical materials, 77, 337–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrive N, O’connor J, & Goodfellow J. (1978). Load-bearing in the knee joint. Clinical orthopaedics and related research(131), 279–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweigart MA, Zhu CF, Burt DM, DeHoll PD, Agrawal CM, Clanton TO, & Athanasiou KA (2004). Intraspecies and interspecies comparison of the compressive properties of the medial meniscus. Annals of biomedical engineering, 32, 1569–1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tissakht M, & Ahmed A. (1995). Tensile stress-strain characteristics of the human meniscal material. Journal of Biomechanics, 28(4), 411–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travascio F, Norberg CD, Filippone G, Best TM, Baraga M, & Jackson AR (2020). Effect of Structural Organization and Composition on Viscoelastic Shear Properties of Porcine Meniscus. Orthopaedic Research Society Annual Meeting. [Google Scholar]

- Tschoegl NW (2012). The phenomenological theory of linear viscoelastic behavior: an introduction. [Google Scholar]

- Walker PS, & Erkman MJ (1975). The role of the menisci in force transmission across the knee. Clinical orthopaedics and related research(109), 184–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W, Chern KY, & Mow VC (1994). Anisotropic viscoelastic shear properties of bovine meniscus. Clinical orthopaedics and related research(306), 34–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]