Abstract

Background:

As health care spending rises internationally, policy makers have increasingly begun to look to improve health care value. However, the precise definition of health care value remains ambiguous.

Methods:

We conducted a scoping review of the literature to understand how value has been defined in the context of health care. We searched PubMed, Embase, Google Scholar, PolicyFile, and SCOPUS between February and March 2020 to identify articles eligible for inclusion. Publications that defined value (including high or low value) using an element of cost and an element of outcomes were included in this review. No restrictions were placed on date of publication. Articles were limited to those published in English.

Results:

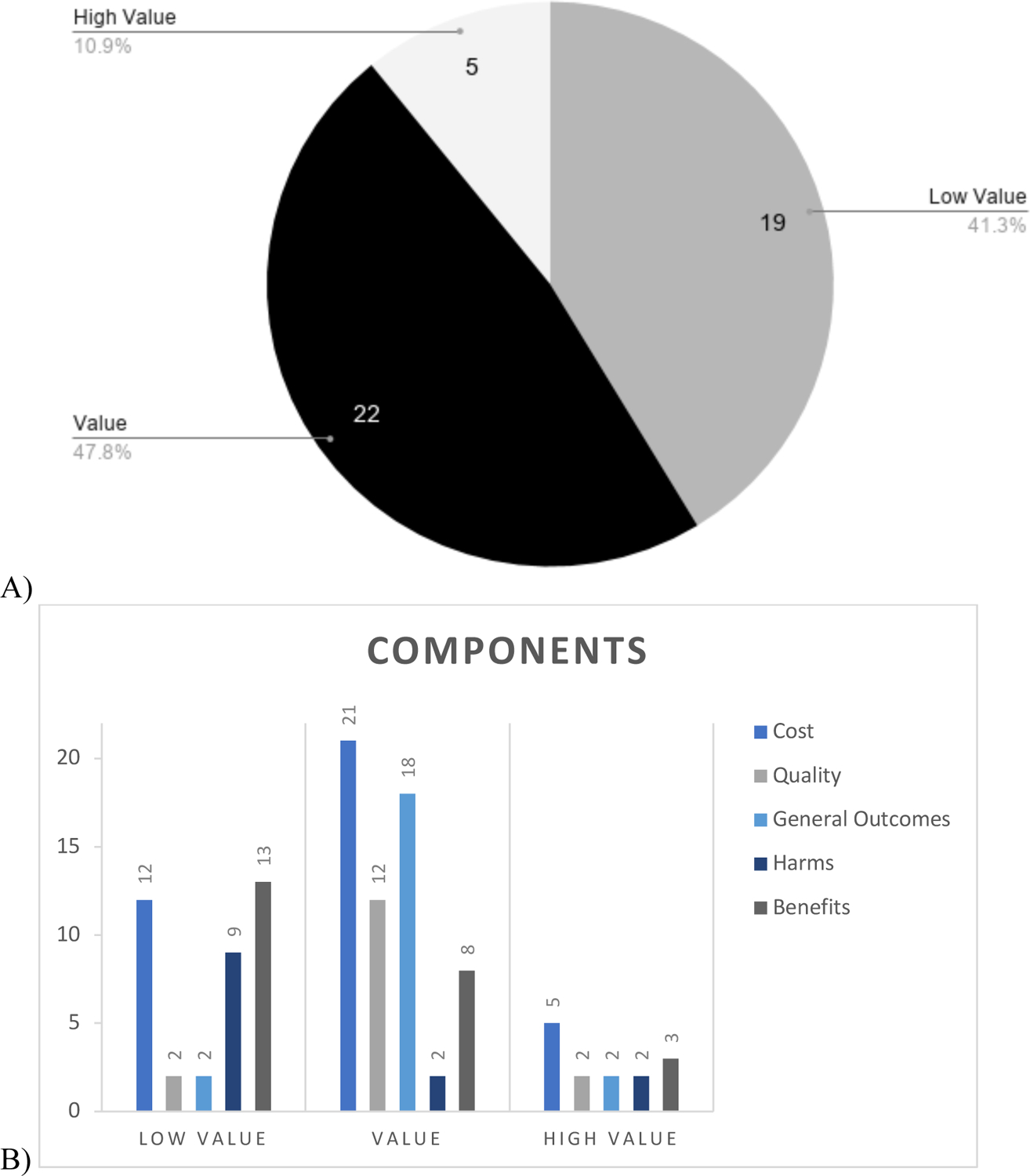

Out of 1,750 publications screened, 46 met inclusion criteria. Among the 46 included articles, 22 focused on overall value, 19 on low value, and 5 on high value. We developed a framework to categorize definitions based on three core domains: components, perspective, and scope. Differences across these three domains contributed to significant variation in definitions of value.

Conclusions:

How value is defined has the potential to influence measurement and intervention strategies in meaningful ways. To effectively improve value in health care systems, we must understand what is meant by value and the merits of different definitions.

Introduction

Health expenditures as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) have been rising in high- and upper-middle income countries, yet improvements in outcomes have lagged.[1] In the USA, health care spending is quickly approaching 20% of GDP, but life expectancy is lower than other high income countries.[2][3] Policy makers and researchers have thus increasingly begun to prioritize health care value.

In the USA, the Affordable Care Act led to the implementation of several value-based payment programs. For example, the Medicare Shared Savings Program provides incentives to improve value [4]. Additionally, the American Board of Internal Medicine launched the Choosing Wisely initiative, encouraging providers to decrease the use of low-value services within their specialties [5]. In the UK, the National Health Service proposed a value-based payment system for pharmaceuticals to replace cost-effectiveness thresholds, but this ultimately failed due to disagreement about the definition of value [6]. Moreover, although not initially implemented to reduce costs, the UK’s Quality and Outcomes Framework proposed a pay-for-performance system to link general practitioner reimbursement to quality and outcome indicators [7]. New South Wales, Australia, also launched a collaborative commissioning initiative to improve value through shared accountability for resource utilization and patient outcomes across multiple local health districts [8].

At a basic level, value is commonly thought of as a ratio of outcomes to cost.[9] Yet, this can be interpreted variably in practice. Outcomes can be defined in terms of quality, harms or benefits. They can be limited to health outcomes or extended to the quality of life. Similarly, definitions of cost can vary by perspective (cost to whom?), time frame (over what period?) or scope (e.g. cost of supplies or services). Given this variability, coming up with a precise, operationalizable definition of value to drive health system change has been challenging. Moreover, ‘low value’ and ‘high value’ may not be opposites: achieving high-value care may require more than elimination of low-value services.

To improve health-care value, a comprehensive understanding of value and its component elements is needed. This scoping review seeks to identify different definitions of value as a first step toward building a comprehensive understanding of value in health care.

METHODS

We conducted a scoping review to characterize how value has been defined in the health-care literature. The scoping review methodology was considered most appropriate for this study, given that our aim was to provide a broad overview of a concept versus gathering evidence to support a practice, as in a systematic review [10, 11].

Search Strategy

Using the terms ‘value’, ‘health care’, ‘low-value care’ and ‘high-value care’, we searched PubMed, Embase, PolicyFile and Google Scholar. No limitations were placed on publication date or study design. Google Scholar hits were limited to the first 100 articles. The search strategy was limited to English-language publications that included search terms in the title to ensure value was the primary focus. Scopus citation tracking was used to identify the top 20 cited articles based on the search terms ‘value’ and ‘health care’. Searches were performed between 10 February 2020 and 25 March 2020. Gray literature was used to provide context for this review but was excluded in analyses.

Article Selection

Articles that focused on defining value using, at a minimum, an element related to cost and an element related to outcomes were eligible for inclusion. This included articles that described definitions of value based on low value services, which implicitly included these elements. Publications investigating the prevalence of high- or low-value care and publications focused on measuring value were included for their definitions of value. Opinion-based articles were included if they focused on defining or measuring value. Replies to articles, books, interviews, introduction pieces, literature reviews and articles inaccessible in full text were excluded. Studies about interventions to improve value were excluded. Supplementary Appendix 2 lists full inclusion/exclusion criteria.

All studies identified through searches were exported and uploaded into Covidence online software. Duplicates were automatically removed. After the initial group review of ∼15 articles to establish inclusion protocols, one author (S.L.) screened the remaining records by title and abstract. Potentially relevant publications were kept for full-text review. One author (S.L.) read all flagged publications in full text. Publications of questionable eligibility were discussed by all three authors, with final decisions made by consensus.

Data Extraction and Analysis

A data extraction template was developed in Microsoft Excel. Elements extracted from articles included the definition of value, components of the definition, perspective, scope and descriptions about what value is not.

Findings from studies were synthesized using narrative methods. Two authors (S.L. and J.P.) reviewed the classification of articles into framework categories. Writing of the review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines for scoping reviews [12].

RESULTS

Search Results

We initially identified 1750 unique publications. Following screening by title and abstract, 113 publications were included in the full-text review, of which 46 met inclusion criteria. The three most common reasons for excluding articles after full-text review were that they did not primarily focus on value, focused on the implementation of interventions to improve value or did not contain an explicit definition of value (Figure 1) [13].

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Chart of Study Selection Process[13]

Among the 46 publications included, 22 focused on overall value [14–35], 19 focused on low value [36–54] and 5 focused on high value [55–59]. Five of the low-value papers were empirical studies that estimated the prevalence of low value care [42–46]. The remaining publications were opinion pieces. Eight publications were from Europe [16, 19, 26, 27, 38, 40, 43, 46], four were from Australia [42, 48, 49, 52] and the remainder were from the USA.

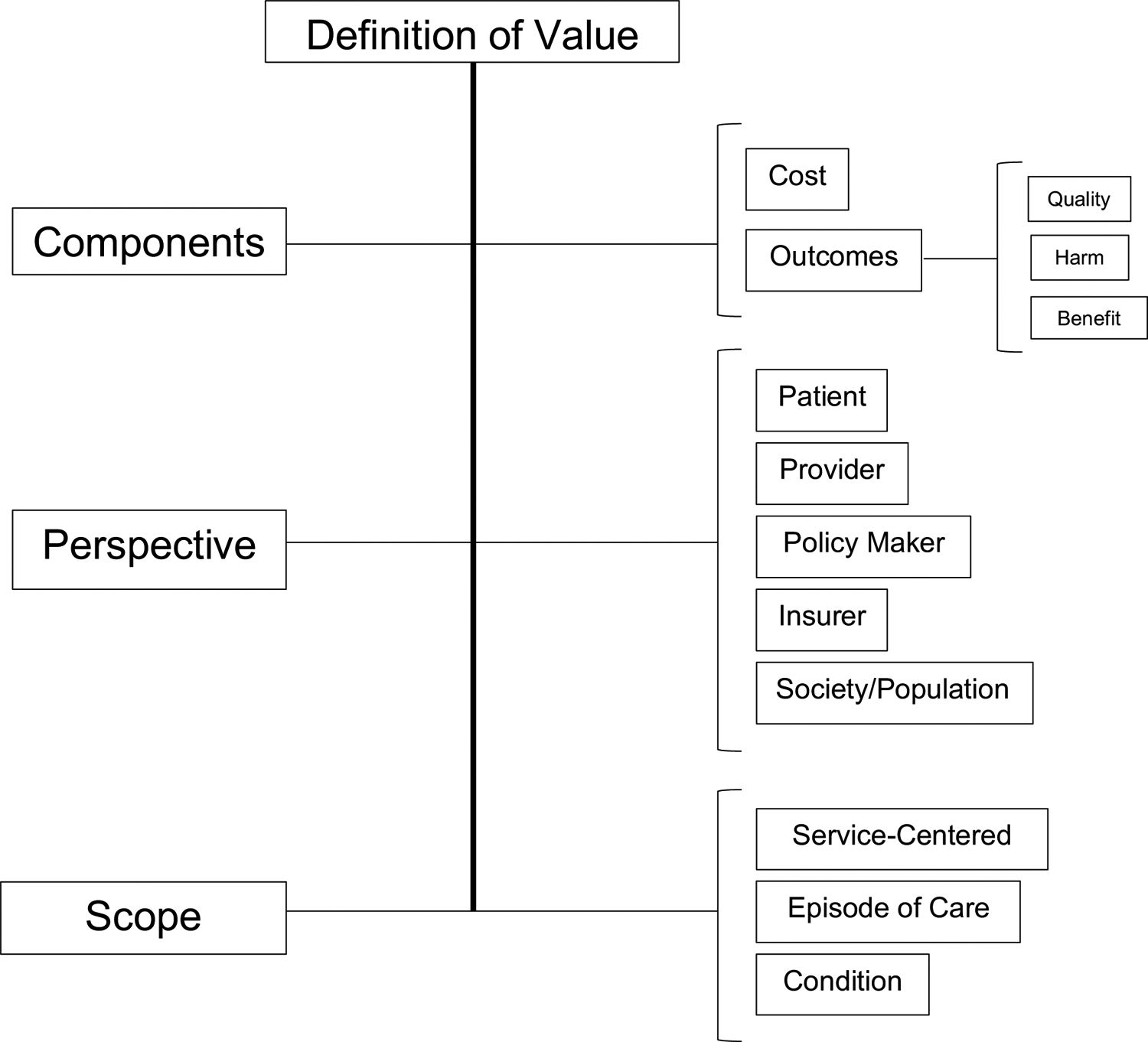

Using the publications included, we developed a framework for conceptualizing and categorizing value definitions (Figure 2). This framework included the following three key elements: components, perspective and scope. Figure 3 categorizes included publications based on these domains. Supplementary Appendix 3 contains a more detailed overview of article classifications across framework domains. Supplementary Appendix 4 showcases examples of operational definitions of value from included publications.

Figure 2.

Framework for Categorizing Definitions of Value

Figure 3.

Summary of Value Definition Categorizations by Framework Element. A) Distribution into low value, value, and high value. B) Distribution of components included. C) Distribution of perspectives. D) Distribution of scope. Note: framework categories are not mutually exclusive, so totals may exceed the number of included publications in the given value category.

Components

Publications incorporated a variety of elements of cost and outcomes. The majority of publications explicitly incorporated cost in their definitions of value. The exceptions were five publications that defined value based on low-value services [38, 39, 44–46]. These publications implicitly assumed that the benefit of these services was zero and thus that any associated costs were wasteful. An additional publication considered the cost of achieving a given outcome to fall under the category of efficiency and value to be defined based on resource allocation from the population or societal perspective [16]. The JAMA patient page on high value care employs the term ‘resource utilization’ instead of cost [56].

Costs typically included monetary costs of care, either limited to direct costs of care or inclusive of indirect costs. In some cases, costs also included opportunity costs. For example, Hall discussed costs in terms of ‘effort, time, or opportunities left behind’ as well as ‘editing of life and costs of adapting to disease and disability’ [28]. Lakdawalla et al. discussed opportunity costs from a governmental perspective, highlighting that ‘the effects on tax revenue, prison spending, public assistance spending, and the like might need to be considered’ [30]. Another element of cost discussed was downstream cost cascades resulting from the initial intervention [59]. Individual health-care services are often grouped or precipitate additional care, and thus, it is important to address cost cascades to understand value [59].

Outcomes and quality were defined interchangeably in some definitions of value, but in others, authors drew distinctions between them. For example, Porter focused on outcomes when defining value, highlighting health status reached, adverse effects of treatment and longer-term health effects as core elements of outcomes. He also distinguished outcomes from quality, defining quality as a measure of care processes [25]. In contrast, Chambers defined quality as a composite measure of patient experience, safety and outcomes [24]. In this case, outcomes were considered a part of quality.

Benefits and harms, as subsets of outcomes, were also commonly used to define value. The term ‘harm’ was used as the counterpoint of benefit, representing ‘adverse effects, unnecessary care, or care that ultimately hurts the patient’ [58] and typically was used in definitions of low-value care. For example, Badgery-Parker defined low-value care as ‘use of an intervention where evidence suggests it confers no or very little benefit to patients, or risk of harm exceeds likely benefit, or, more broadly, the added costs of the intervention do not provide proportional added benefits’ [42]. As reflected in this definition, the terms ‘benefit’ and ‘harm’ were often used in a way that suggested weighing alternatives. Benefits were often recognized to be subjective. For instance, MacStravic described that a benefit ‘depends on what people ascribe positive value to and on whatever they prefer and desire’ [35]. Importantly, benefits and harms may include long-term consequences such as diseases averted or quality-adjusted life years gained [59]. Table 1 illustrates how definitions of value vary by framework domain.

Table 1.

Examples of variation in definitions of value across the three framework elements

| Author | Definition Quotations | Feature |

|---|---|---|

| Components | ||

| Chambers, 2016[24] | “VALUE=QUALITY (Experience + Clinical Outcomes + Safety)/COST” | Quality, Outcome, Cost |

| “Outcomes are optimized when balance is achieved between the clinical aspects of care, attention to the patient’s perceptions of the care, and partnership between the care providers and the patient.” | ||

| Hall, 2020[28] | “Value refers to outcomes in relation to cost.” | Outcome, Cost |

| OUTCOMES: “Traditional value analyses, where health gains are assessed relative to costs, may be adequate for measuring the effectiveness of treatments on objective conditions…But when treatments involve serious side-effects that make overall benefit less obvious, the outcome of interest may need to include quality of life…” COST: “Personal costs paid by individuals rather than costs associated with health care itself” (e.g. loss of dispositional goods, costs of pursuing well-being, editing of life). | ||

| Owens, 2011[59] | “Whether an intervention provides high value depends on assessing whether its health benefits justify its costs.” | Benefit, Cost |

| BENEFITS: “Health benefit can be measured in many ways, including conditions diagnosed or prevented or life-years or quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) gained.” COSTS: “The key principle in assessing costs is that the cost of an intervention should include the cost of the intervention and any downstream costs, defined as costs that occur as a result of the intervention.” | ||

| Perspective | ||

| Razmaria, 2015[56] | “High-value care means providing the best care possible, efficiently using resources, and achieving optimal results for each patient.” | Patient |

| Patients can ask their physicians questions about tests and treatments to pursue high value care. | ||

| Gray, 2017[16] | “Value has two dimensions when considering populations.” 1. “Allocative value--how well the resources available for the population have been allocated to different groups;” 2. “Once the resources have been allocated they have to be used optimally for everyone in need in that population” | Population |

| Verkerk, 2018[40] | “Low-value care is care that provides minimal or no health benefit; which benefit does not weigh up to the harms; which benefit does not weigh up to the costs; that is less cost-effective than alternative care, and that does not fit the preferences of the patient.” | Multiple |

| Includes ineffective (medical), inefficient (societal), and unwanted (patient) care. | ||

| Scope | ||

| Porter, 2010[25] | “Health outcomes achieved per dollar spent” | Cycle of Care / Condition |

| OUTCOMES: Tier 1: health status achieved or retained, Tier 2: incorporates recovery time and any adverse events or effects related to treatment, Tier 3: “sustainability of health,” including ‘recurrences of the original disease or longer-term complications.’ COSTS: “Total costs of the full cycle of care for the patient’s medical condition, not the cost of individual services…To measure true costs, shared resource costs must be attributed to individual patients on the basis of actual resource use.” | ||

| Chalmers, 2017[49] | “Low-value healthcare has been defined as care that is inappropriate for a specific clinical indication, inappropriate for a clinical indication in a specific population or an excessive frequency of services relative to expected benefit.” | Service |

| “Using direct measurement…low value is viewed through a binary lens: if the patient characteristics do not match the indication for a service, then it is counted as a low value service.” | ||

Perspective

Perspective is another important factor to consider in definitions of value. Perspectives considered in these publications included the individual patient, provider, caregiver, insurer, society/population, and policy-maker/health system.

Definitions of costs varied by perspective. From the patient perspective, costs were typically defined in monetary terms (e.g. out-of-pocket and insurance premiums), but they often extended to include opportunity costs or the cost of ‘adapting to disease and disability’ [28]. From the payer perspective, costs were defined as hospital charges and negotiated reimbursement rates [17], while from the health system perspective, cost definitions focused on monetary costs of care to the health system [23]. From the societal perspective, costs for entire populations and elements of resource allocation were considered [16].

Scope

In this context, scope refers to whether value was defined around the delivery of a single service (e.g. imaging for lower back pain), an episode of care (e.g. full course of treatment for acute myocardial infarction) or a condition (e.g. treatment of diabetes over time). Notably, all five prevalence studies measured low-value care based on utilization of specific services [42–46]. Two other publications also defined low value solely based on lists of top five low-value services [38, 39].

Service-centered definitions of value provide snapshot views of value that are relatively easy to measure and may provide useful information to health systems, but they may ignore important elements of care relevant to patients. For example, Chambers et al. note that ‘outcomes are optimized when balance is achieved between the clinical aspects of care, attention to the patient’s perceptions of the care, and partnership between the care providers and the patient’ [24]. Although not all definitions of value with a broad scope took the patient perspective, this nonetheless highlights the more comprehensive nature of a definition of value centered around an episode of care.

DISCUSSION

The articles included in this review showcased a range of definitions of value. Given their unique features, it is impossible to generate one all-encompassing definition of value from them. Thus, we developed a framework for analyzing definitions of value, highlighting the following three core domains: components, perspective and scope. Differences across these features help to elucidate distinctions in definitions.

At first glance, definitions of value collected in this review may seem similar given frequent usage of terms such as quality, outcomes and cost. Yet, the specifics of these terms varied significantly, generating markedly different definitions of value. Additionally, many definitions incorporated subjective judgment. For example, Owens et al. defined high value based on ‘whether its health benefits justify its costs’ [59], while others defined low-value services as those that produce little benefit. Both justification of costs and determination of benefit require judgments that may differ between observers.

Differences in perspective also influenced definitions of value, as illustrated by Porter’s patient-centered definition and Gray’s societal definition. Porter defined value as ‘[patient] health outcomes achieved per dollar spent’ [25]. In contrast, Gray viewed value from a population perspective that requires clinicians to ‘ensure that the right people reach the right service’ [16].

Finally, scope impacts the numerator and denominator of the value equation, thus inviting different interventions for improvement. For example, Volpp et al. defined low-value services as those for which ‘the cost of providing those services is high relative to the health benefit they confer’ [53]. This definition used a narrow scope. In contrast, Hall et al. defined value for a long-term condition, with costs incorporating opportunity costs and adaptation and outcomes incorporating health gains and quality of life [28]. It is likely that the application of definitions of value with such a broad scope would yield different results from those with a narrower scope.

In addition to elucidating differences in definitions of value, this review highlighted important distinctions between low value, overall value and high value, suggesting that these may not necessarily fall along one continuous spectrum. Definitions of low value primarily reflected a service-centered, health system perspective, whereas definitions of overall value generally focused on longer time frames and reflected a patient perspective or multiple perspectives. These differences imply a disconnect between the elimination of low-value care and the promotion of high-value care, leaving fundamental questions about how to reconcile the two. Overall value is not merely the absence of services whose harms and costs outweigh their benefits. Moreover, patients may have concerns or preferences that are not specific to a given service and that may not even be measurable using existing metrics; services considered to be low value also are likely to generate benefits for some patients in particular situations. Achieving a high-value health-care system is likely to include initiatives to reduce the use of low-value services in addition to initiatives aiming to promote good quality and outcomes in a cost-conscious manner, but we must acknowledge that these two efforts may require different strategies for success.

Very few included articles explicitly defined high value as a distinct concept. Two possible explanations for this are that overall value was conflated with high value or that high value was conflated with high quality. In fact, the first element of Razmaria’s definition of high value is ‘providing the best care possible’, emphasizing the centrality of high quality [56]. However, focusing solely on the quality aspect of value ignores the element of cost that distinguishes quality from value. Moreover, unlike definitions of quality, definitions of value often incorporate weighing alternatives or ‘justifying’ costs. If two services produce equally beneficial outcomes but one is lower cost, could both be considered high value? At the crux of this question lies the issue of whether value should be defined in absolute (e.g. quality achieved and exact costs) or relative (e.g. net benefit and opportunity costs) terms. Definitions of value included in this review give different views on this issue, suggesting that either may be appropriate depending on the context. Given that no single definition of value is appropriate for all settings, it is crucial to be explicit and intentional in selecting a definition. Our proposed value framework depicted in this article can assist. For example, consider defining value of outpatient care from the insurer perspective. In the USA, where individuals tend to switch health insurance plans relatively frequently, it is likely that the scope selected would be service-centered, with costs defined in dollar terms and outcomes defined around immediate effects. In countries with national health systems, however, the scope may be broadened to a particular condition with costs and outcomes inclusive of distant downstream costs and long-term effects. Alternatively, we can consider applying the framework from the perspective of a terminally ill cancer patient, with the scope being cancer. It is likely that the patient would consider quality of life as a core aspect of outcomes and indirect costs of treatment as core aspects of costs. Finally, we can apply the framework to define the value of a proposed government policy. In this case, the perspective is the policymaker, and components of the value definition are likely to incorporate opportunity costs (i.e. funding taken away from other government initiatives), direct costs to the government and measurable direct outcomes. The scope may vary based on the content of the policy. As shown through these examples, this framework can help in choosing how to define value in a thoughtful manner.

Limitations

This review has several limitations. First, this was a scoping review, and thus relied on title searches to identify relevant articles representative of the breadth of literature on the topic. There are likely other relevant publications not included. Second, most of the articles included are opinion pieces, which inherently contain bias, though the intent of this review was to describe subjective definitions. Third, articles included were from Europe, Australia and the USA. Thus, findings may not reflect definitions of value from other areas. Finally, although three researchers were involved in the planning of the study, in resolving questions that arose regarding inclusion and exclusion criteria and in an initial review of a subset of articles, only one reviewer selected articles for inclusion, making it susceptible to researcher bias. However, our findings were broad and varied, suggesting that a wide range of perspectives were successfully identified. Moreover, standard criteria for inclusion, standard extraction templates and review of framework categorizations by two authors helped to mitigate this limitation.

Conclusion

This review highlights that there is no single definition of value, but rather different definitions of value may be appropriate for different situations. What is essential is to be intentional and explicit about choices made in defining value. The framework we developed provides a guide for parsing definitions of value based on their components, perspective and scope to facilitate deliberate decision-making, recognizing that generating definitions of value inherently involves subjective judgment. Moreover, this review underscores that there are key differences in how low value and overall (or high) value are defined. It is likely that efforts to improve value will need to incorporate elements of each, depending on the specific setting. As health-care spending continues to grow, addressing costs alongside quality and outcomes becomes ever more critical in ensuring the sustainability of health systems. Although selecting one universal definition of value may not be practical or advisable, recognizing differences across definitions and using them to promote value from multiple angles and settings will help to maximize success.

Supplementary Material

Funding:

This study was supported by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R01HS022882). The AHRQ had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare no competing interests with regard to the submitted work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Domestic general government health expenditure per capita (current US$) | Data. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.GHED.PC.CD (accessed 13 Oct 2020).

- 2.NHE Fact Sheet | CMS. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NHE-Fact-Sheet (accessed 25 Jun 2020).

- 3.Sisko AM, Keehan SP, Poisal JA, et al. National Health Expenditure Projections, 2018–27: Economic And Demographic Trends Drive Spending And Enrollment Growth. Health Aff (Millwood) 2019;38:491–501. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.CMS’ Value-Based Programs | CMS. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/Value-Based-Programs (accessed 22 Jul 2020).

- 5.Our Mission. https://www.choosingwisely.org/our-mission/ (accessed 22 Jul 2020).

- 6.Kuchenreuther MJ, Sackman JE. Value-Based Healthcare in the: United Kingdom. Pharm Technol 2015;39:26–30. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roland M, Campbell S. Successes and failures of pay for performance in the United Kingdom. N Engl J Med 2014;370:1944–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr1316051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collaborative Commissioning - Value based healthcare. https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/Value/Pages/collaborative-commissioning.aspx (accessed 13 Oct 2020).

- 9.Moriates C, Arora V, Shah N. Defining Value: Connecting Quality and Safety to Costs of Care. In: Understanding Value-Based Healthcare. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education, 2015, 73–94 accessmedicine.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?aid=1106933866 (accessed 21 Jan 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colquhoun HL, Levac D, O’Brien KK, et al. Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67:1291–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, et al. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol 2018;18:143. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:467. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Health Care Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration. PLOS Med 2009;6:e1000100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ken Lee KH, Matthew Austin J, Pronovost PJ. Developing a Measure of Value in Health Care. Value Health 2016;19:323–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2014.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeCamp M. Toward a Pellegrino-inspired theory of value in health care. Theor Med Bioeth 2019;40:231–41. doi: 10.1007/s11017-019-09486-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gray M. Value based healthcare. BMJ 2017;356:j437. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta R. Health Care Value: Relationships Between Population Health, Patient Experience, and Costs of Care. Prim Care 2019;46:603–22. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2019.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kamal RN, Lindsay SE, Eppler SL. Patients Should Define Value in Health Care: A Conceptual Framework. J Hand Surg 2018;43:1030–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2018.03.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marzorati C, Pravettoni G. Value as the key concept in the health care system: how it has influenced medical practice and clinical decision-making processes. J Multidiscip Healthc 2017;10:101–6. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S122383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Teisberg E, Wallace S, O’Hara S. Defining and Implementing Value-Based Health Care: A Strategic Framework. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll Published Online First: 10 December 2019. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsevat J, Moriates C. Value-Based Health Care Meets Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:329–32. doi: 10.7326/M18-0342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weeks WB, Weinstein JN. Caveats to consider when calculating healthcare value. Am J Med 2015;128:802–3. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wheeler SB, Spencer J, Rotter J. Toward Value in Health Care: Perspectives, Priorities, and Policy. N C Med J 2018;79:62–5. doi: 10.18043/ncm.79.1.62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chambers P, B L, Boat A. Patient and Family Experience in the Healthcare Value Equation. Curr Treat Options Pediatr 2016;2:267–79. doi: 10.1007/s40746-016-0072-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Porter ME. What is value in health care? N Engl J Med 2010;363:2477–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1011024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elf M, Flink M, Nilsson M, et al. The case of value-based healthcare for people living with complex long-term conditions. BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17:24. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1957-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gilmore KJ, Pennucci F, De Rosis S, et al. Value in Healthcare and the Role of the Patient Voice. Healthc Pap 2019;18:28–35. doi: 10.12927/hcpap.2019.26031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hall A. Quality of Life and Value Assessment in Health Care. Health Care Anal HCA J Health Philos Policy 2020;28:45–61. doi: 10.1007/s10728-019-00382-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kawamoto K, Martin CJ, Williams K, et al. Value Driven Outcomes (VDO): a pragmatic, modular, and extensible software framework for understanding and improving health care costs and outcomes. J Am Med Inform Assoc JAMIA 2015;22:223–35. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2013-002511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lakdawalla DN, Doshi JA, Garrison LP, et al. Defining Elements of Value in Health Care-A Health Economics Approach: An ISPOR Special Task Force Report [3]. Value Health J Int Soc Pharmacoeconomics Outcomes Res 2018;21:131–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2017.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu TC, Bozic KJ, Teisberg EO. Value-based Healthcare: Person-centered Measurement: Focusing on the Three C’s. Clin Orthop 2017;475:315–7. doi: 10.1007/s11999-016-5205-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manner PA. Guest Editorial: Is There Value in Value-based Health Care? Clin Orthop 2019;477:265–7. doi: 10.1097/CORR.0000000000000617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mkanta WN, Katta M, Basireddy K, et al. Theoretical and Methodological Issues in Research Related to Value-Based Approaches in Healthcare. J Healthc Manag Am Coll Healthc Exec 2016;61:402–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wegner SE. Measuring Value in Health Care: The Times, They Are A Changin’. N C Med J 2016;77:276–8. doi: 10.18043/ncm.77.4.276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.MacStravic S. Questions of value in health care. Mark Health Serv 1997;17:50–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beaudin-Seiler B, Ciarametaro M, Dubois R, et al. Reducing low-value care. Health Aff Blog Post 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blumenthal-Barby J. “Choosing wisely” to reduce low-value care: a conceptual and ethical analysis. J Med Philos 2013;38:559–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bonnet R, Laurencet M, Gaspoz J-M, et al. Creating a list of low-value health care interventions according to medical students perspective. Eur J Intern Med 2018;52:e41–2. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2018.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bulger J, Nickel W, Messler J, et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: Five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med 2013;8:486–92. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Verkerk EW, Tanke MA, Kool RB, et al. Limit, lean or listen? A typology of low-value care that gives direction in de-implementation. Int J Qual Health Care 2018;30:736–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weeks WB, Wadsworth EB, Rauh SS, et al. The urgent need to create healthcare value. Healthc Financ Manag J Healthc Financ Manag Assoc 2013;67:136–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Badgery-Parker T, Pearson S-A, Chalmers K, et al. Low-value care in Australian public hospitals: prevalence and trends over time. BMJ Qual Saf 2019;28:205–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kool RB, Verkerk EW, Meijs J, et al. Assessing volume and variation of low-value care practices in the Netherlands. Eur J Public Health. 2020. Apr; 30(2): 236–240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lind K. How Big is the Problem of Low-Value Health Care Service Use. AARP Website Aarp Orgcontentdamaarpppi201803how-Big---Probl--Low-Value-Health-Care-Serv-Use Pdf Publ March 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schwartz AL, Landon BE, Elshaug AG, et al. Measuring low-value care in Medicare. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:1067–76. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.1541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sprenger M, Robausch M, Moser A. Quantifying low-value services by using routine data from Austrian primary care. Eur J Public Health 2016;26:912–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baker DW, Qaseem A, Reynolds PP, et al. Design and use of performance measures to decrease low-value services and achieve cost-conscious care. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:55–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chalmers K, Badgery-Parker T, Pearson S-A, et al. Developing indicators for measuring low-value care: mapping Choosing Wisely recommendations to hospital data. BMC Res Notes 2018;11:163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chalmers K, Pearson S-A, Elshaug AG. Quantifying low-value care: a patient-centric versus service-centric lens. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Miller G, Rhyan C, Beaudin-Seiler B, et al. A framework for measuring low-value care. Value Health 2018;21:375–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pandya A. Adding cost-effectiveness to define low-value care. Jama 2018;319:1977–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scott IA, Duckett SJ. In search of professional consensus in defining and reducing low-value care. Med J Aust 2015;203:179–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Volpp KG, Loewenstein G, Asch DA. Assessing value in health care programs. JAMA 2012;307:2153–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.3619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Beaudin-Seiler B. Reducing Low-Value Care: Saving Money and Improving Health. Alatrum Healthcare Value Hub 2018. Research Brief No.32 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Qaseem A, Alguire P, Dallas P, et al. Appropriate use of screening and diagnostic tests to foster high-value, cost-conscious care. Ann Intern Med 2012;156:147–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Razmaria AA. JAMA PATIENT PAGE. High-Value Care. JAMA 2015;314:2462. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.16990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Roca RP. High-Value Mental Health Care and the Person in the Room. Psychiatr Serv Wash DC 2020;71:110–1. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201900357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Owens D, Qaseem A, Chou R, et al. Summaries for patients. High-value, cost-conscious health care. Ann Intern Med 2011;154:I30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-3-201102010-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Owens DK, Qaseem A, Chou R, et al. High-value, cost-conscious health care: concepts for clinicians to evaluate the benefits, harms, and costs of medical interventions. Ann Intern Med 2011;154:174–80. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-3-201102010-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.