Abstract

In 2019, 4.4 million referrals of maltreatment were made that affected approximately 7.9 million children. It was estimated that 9.3% of the referrals were related to child sexual abuse (CSA). To prevent negative psychosocial and health-related outcomes associated with CSA, CSA survivors often participate in a forensic interview, medical and behavioral health assessments, and behavioral health treatment while navigating other life disruptions or changing family dynamics precipitated by the CSA (e.g., change in custody or household, lack of contact with preparator, etc.). The assessment and treatment of pediatric survivors of CSA by multidisciplinary teams (MDT) can enhance families’ engagement and participation with the legal process, medical evaluation, and behavioral health services. This paper explores the Nemours Children’s Health, Delaware MDT’s approach to assessing and treating CSA, explores benefits and barriers associated with the current model, and discusses public health implications of a MDT approach to addressing CSA.

Introduction

Child sexual abuse (CSA) is a global public health concern and a serious issue in pediatric medicine. Studies have reported associations between CSA and many negative psychosocial and health-related outcomes, including development of behavioral issues (e.g., posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, suicidality) and physical health morbidities (e.g., smoking cigarettes, sexually transmitted diseases, premature death) particularly if CSA-related concerns are untreated or unaddressed.1–5 Given these negative associations and estimated rates of CSA affecting 1% to 35% of children,6 it is critical to develop systematic frameworks that support the early identification and provision of evidence-based treatment for CSA survivors to potentially mitigate negative long-term effects of abuse victimization.

The Multidisciplinary Team (MDT) Approach to Treating Child Sexual Abuse

Investigations of CSA necessitate coordination of various multidisciplinary team (MDT) members including law enforcement, child protective services, medical and behavioral health professionals, legal professionals and victim advocates, often based at a Children’s Advocacy Center (CAC), to increase access to community-based medical and behavioral healthcare services, improve continuity of care for children and families, and reduce duplicative services.7 In addition to agency-specific roles, MDT members provide needed education to families about the benefits of medical and behavioral healthcare services and advocate to ensure a family is successfully connected with evidence-based treatment to mitigate any long-term impact of CSA for the survivor. For example, the Delaware (DE) Department of Services for Children, Youth, and Their Families (DSCYF) and law enforcement professionals often complete family assessments which may recognize service needs, and frequently connect families with agency-specific victim advocates if a need for additional support is identified. At the local level, the partnership between Nemours Children’s Health DE medical and behavioral healthcare services and the CAC of DE serves this goal by directly providing family-centered/trauma-informed services for the CSA survivor and their family. In addition to medical and behavioral health trauma services, Nemours Children’s Health, DE provides pediatric primary and specialty care for more than 100 pediatric specialties in Delaware, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania, which enables trauma providers to make appropriate referrals to other specialties (e.g., psychiatry, adolescent medicine, gastroenterology, etc.) as needed. In this brief report, we aim to provide an overview of the collaboration between Nemours Children’s Health and multi-agency partners that delivers trauma-informed care to CSA survivors.

Approach to Assessing and Treating Child Sexual Abuse at the Local Level in Delaware

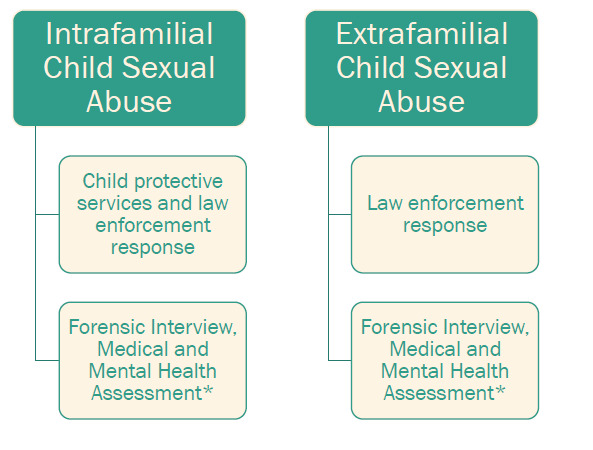

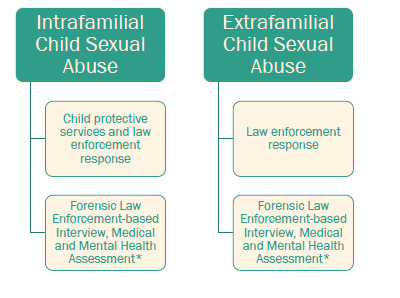

Once an allegation of CSA has been made, the CSA survivor is referred by local law enforcement, child protective services (i.e., DSCYF), or the DE Department of Justice to the CAC for a forensic interview (FI). The agency that refers the CSA survivor for the forensic interview depends on the survivor’s age and the status of the survivor’s relationship with the alleged perpetrator(s) (See Figures 1 & 2). Intrafamilial CSA, or that involving a family/household family in a caretaking capacity, necessitates involvement of DSCYF, whereas extrafamilial CSA may involve only law enforcement investigators. Forensic interviewing, a means of gathering factual information from a CSA survivor or witness about abuse for use in a legal setting in a legally defensible and developmentally appropriate manner, is frequently essential to the conduction of CSA investigations, as the survivor and alleged perpetrator may be the only people who know details of what really happened.8,9 Interviews are conducted by individuals who are skilled in child development, linguistics, civil and criminal offenses, memory, and suggestibility using a nationally recognized and approved forensic interview process. These FIs, which are performed in a safe, child-friendly, neutral setting, provide a unique opportunity for the survivor to share specific details regarding their abuse experience that may impact investigation and prosecutorial trajectory and the safety of other children and adolescents around them (such as through the identification of other abuse survivors and/or perpetrators).

Figure 1.

Referral for Forensic Interview, Survivor Age < 12 Years

Figure 2.

Referral for Forensic Interview, Survivor Age > 12 Years

*A survivor may disclose abuse in the medical or mental health setting, that then results in notification of child protective services and/or law enforcement.

*A survivor may disclose abuse in the medical or mental health setting, that then results in notification of child protective services and/or law enforcement.

Beyond disclosures with legal or safety significance, participation in a FI importantly provides CAC professionals an opportunity to engage CSA survivors and their families in longitudinal access to community-based services to promote long-term coping and psychosocial functioning for symptoms related to CSA psychological trauma. The CAC employees, specifically the Family Resource Advocate (FRA), perform a comprehensive family needs assessment during initial contact with the caregiver of a survivor of CSA. This comprehensive family needs assessment permits the MDT to tailor referrals to appropriate services (social, medical, or behavioral health-based) for the family and CSA survivor during post-FI debriefings. Through completion of a checklist, the FRA may identify essential needs (clothing, food, housing, transportation, utilities, or energy assistance), social needs (childcare, custody, legal assistance, employment, or workforce training, educational resources, legal assistance) or other child or family health and safety-based needs (e.g., dental/oral care, family planning, prenatal care, insurance, or child development-related issues).

Through a unique, geographical co-location at the Nemours Children’s Hospital Wilmington-based facility, the New Castle County CAC-based FRA frequently provides a “warm-handoff,” or a brief face-to-face transfer of services, to Nemours medical and behavioral health professionals when identifying survivor or caregiver needs in addition to referrals to other community-based programs. The “warm-handoff” permits the Nemours medical or behavioral health professional to further assess symptoms of significant concern (e.g., suicidal ideation, depression, etc.) or schedule a follow up visit with the family. External to the co-located site in Wilmington, two operational, southern-based Delaware CACs collaborate with medical and behavioral health professionals both at Nemours and across the state via telephone, teleconference, or electronically to ensure expedited, comprehensive communication of survivor and family needs irrespective of geographic location.

Survivors of CSA may receive medical care through the Nemours Children at Risk Evaluation (CARE) Program which offers non-acute medical examinations similar to the regular well-child visit a child has had with a pediatrician, assessing the child’s physical health from head-to-toe. This examination often includes an ano-genital assessment to identify any injuries or infection related to the CSA experience or address any medical concerns the survivor or family may have. The examination may also include lab and radiology tests depending on the reason the child has been referred for a forensic examination. Photodocumentation may be performed during the examination for a variety of reasons to assist in medical management of the child survivor and for documentation of injuries for medico-legal, forensic purposes.

Parents and caregivers are encouraged to dually participate in the examination and be present throughout care. A CSA survivor under the age of 12 must be accompanied by an adult chaperone during the examination; if the survivor is 12 years of age or older, he or she may choose to have a support person (family member, friend, or advocate) in the room during the exam, but there will always be an accompanying chaperone.

Undergoing a medical examination may be a stressful time for a CSA survivor and caregiver. Care is taken to discuss the exam before it is completed to prepare the survivor and their caregiver in advance of any interventions. It is important that the survivor and their caregiver(s) have the opportunity to ask questions and express any concerns they might have. During the assessment, the survivor and accompanying caregiver or support person may be asked about medical and behavioral symptoms, such as pain, discomfort, difficulty sleeping, changes in appetite, changes in school performance, self-injurious behaviors and suicidal ideation. Identification of emergent medical or behavioral symptoms may warrant referral to the Nemours emergency department for crisis intervention, based on case-specific circumstances. Utilizing a trauma-informed approach, the CARE Program medical professionals explain every part of the examination before and as it is performed. They also seek feedback during the process about how the survivor is feeling to minimize anxiety and answer any questions.

At the conclusion of the appointment, the medical professional reviews the findings from the examination and any results of testing available during a post-exam debriefing and call with any outstanding results. The outcome of the visits and testing results are discussed with the parent/legal guardian and the survivor within the context of patient confidentiality considerations and their developmental stage. Referrals to counseling, supportive services or other subspecialty medical professionals may be made if needed, based on case-dependent circumstances, the findings from the examination, psychological distress reported during the visit, or parent- or youth-reported interest in additional services. The healthcare professional also maintains contact with the MDT regarding the specific needs of the child CSA survivor and family.

Once a referral is placed by the CARE team or a handoff complete, families are connected to a behavioral health professional with specialized trauma training. Of note, families are also able to access behavioral health services for trauma at Nemours Children’s Hospital DE through a self-referral, a referral from a Nemours healthcare professional, or a direct referral from the CAC. Every CSA survivor between the ages of three and 21, and their family, must complete a trauma consultation at the Trauma and Resiliency Clinic located in Nemours’ Division of Behavioral Health to identify whether trauma services offered best fit the family’s presenting concerns before they are placed on therapy waitlists.

Trauma Consultation. The trauma consultation occurs over two appointments, typically 75-90 minutes in length, and is conducted by a behavioral health clinician with specialized trauma training. This consultation is provided in person at Nemours Children’s Health DE or via a HIPAA compliant virtual platform. This consultation is divided into two parts: information gathering and a formal assessment of posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS). The clinician begins and ends the trauma consultation with the CSA survivor and their caregiver to orient the family to the process and to emphasize the importance of a family-based approach to addressing PTSS. However, during the information gathering portion of the trauma consultation process, the caregiver and the CSA survivor meet with the clinician independently for much of the appointment to ensure both parties have privacy and can independently express their thoughts and feelings about the allegations of sexual abuse freely. It is also common for individuals to fear judgement from family members or may be protective of loved ones’ feelings, which may result in underreporting of CSA details and associated symptomatology; therefore, gathering information about the CSA survivor’s experience independently of the caregiver helps mitigate underreporting. The goals of the trauma consultation are multifaceted and include:

Gathering information about the CSA and any other potentially traumatic events the family has experienced,

Ensuring that the CSA survivor is safe,

Assessing suicide and homicide risk,

Determining whether any additional mandated reporting is needed,

Confirming with the caregiver that the CSA survivor has completed the forensic interview before any questions about the allegations are asked of the CSA survivor, and

Briefly gathering more information about the family’s concerns surrounding the CSA survivor’s emotional and behavioral concerns.

Information about the status of the investigation is also gathered at this first appointment to determine when the CSA survivor should be clinically evaluated. For example, for CSA survivors who have not completed their forensic interview, questions about the allegation or how the CSA survivor is adjusting to the allegation are not asked. Instead, an additional appointment may be scheduled after the CSA survivor’s scheduled forensic interview.

The second portion of the trauma consultation includes a formal assessment of caregiver- and CSA survivor-reported PTSS, as well as other presenting concerns (e.g., depression, anxiety, problematic sexual behavior, oppositional behavior, substance use). The formal assessment includes one broadband measure and one trauma screening. The Behavior Assessment System for Children, 3rd Edition (BASC-3)10 is administered to the caregiver and age-appropriate CSA survivor to provide information about the child’s presenting behavioral and emotional concerns. The Child and Adolescent Trauma Screening, Version 2.0 (CATS 2.0)11 is also administered to both the caregiver and/or the CSA survivor, independently, to assess whether any other potentially traumatic events (PTEs) have occurred, and to assist in determining whether the CSA survivor’s adjustment to the allegations of abuse is normative, indicative of posttraumatic stress, or indicative of other behavioral health concerns. The CATS 2.0 is administered to the caregiver and CSA survivor independently to explore both parties’ perception of the traumatic event(s) and its aftermath, which may play an important role in treatment. The CATS 2.0 produces a total symptom score that is used to identify whether a survivor is experiencing clinically relevant levels of posttraumatic stress symptoms. Of note, a recent meta-analysis found that only 15.9% of youth who were exposed to a PTE developed posttraumatic stress disorder.12 Given that CSA survivors with elevated PTSS are more likely to have positive treatment outcomes if connected with trauma-focused, evidence-based treatments,13 such as Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT),14 identifying elevated PTSS via a trauma symptom screening like the CATS 2.0 is helpful in identifying CSA survivor and families who would benefit from trauma-focused, evidence-based treatments. For the CSA survivor who appears to be adjusting well (i.e., not clinically elevated PTSS, many protective factors), clinicians may share psychoeducation with families about how they can continue to enhance the CSA survivor’s protective factors, as well as how to recognize when treatment may be needed. Conversely, for CSA survivors who are not endorsing PTSS but are presenting with other symptoms that have seemingly been exacerbated by the CSA or another traumatic event identified during the administration of the CATS 2.0, clinicians may offer treatment referrals for other evidence-based interventions—such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Exposure and Response Prevention, or Dialectical Behavioral Therapy—that may be a better fit with the CSA survivor’s presenting concerns. Before finalizing recommendations and referrals for families, a brief risk assessment is also conducted to ensure that the CSA survivor is safe to be placed on a treatment waitlist. Feedback regarding PTSS scores and treatment recommendations are provided to the CSA survivor and their caregivers. Time is spent answering questions about treatment recommendations as well as providing relevant psychoeducation and brief parenting skills that may be help the CSA survivor’s adjustment.

Trauma Treatment. After the Trauma Consultation is completed, families who are referred for trauma treatment through Nemours are placed on the waitlist. The Trauma and Resiliency Clinic offers two trauma-specific interventions, TF-CBT and Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT), and two trauma-informed evidence-based intervention, Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) and Body Safety (i.e., an abbreviated version of TF-CBT). Risk assessments, such as the “Ask Suicide-Screening Questions” (ASQ)15 and the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS),16 are administered to ensure that families are safe to be placed on a treatment waitlist. Once CSA survivor and their family complete treatment, symptom progress is monitored via re-administration of the BASC-3 and CATS 2.0. At this time, a clinician may make additional referrals (e.g., further testing to assess other areas of concerns, psychotropic intervention) as necessary.

Booster Sessions and Additional Referrals to Consider. Once the CSA survivor and their family complete treatment, they are welcome to return for booster sessions as needed until they are no longer eligible for services as a patient at Nemours. These booster sessions are often limited to less than five sessions total, often due to the clinical needs of the families, and may serve many purposes, such as to reassess new symptoms of concern, review skills to help the CSA survivor regulate emotions related to court testimony, engage in additional cognitive processing work, or review skills in the wake of an additional PTE.

Implications of the Nemours Children’s Health, Delaware MDT’s Approach to Assessing and Treating Child Sexual Abuse

The co-location of the Wilmington-based Nemours CARE Program and Trauma and Resiliency Clinic with the New Castle County-based CAC streamlines services aimed to support those who have experienced CSA and encourages efficient information sharing to improve the social and emotional outcomes of CSA survivors and families. Although the appointments may occur at different points in time, families experience the forensic interview, medical examination, trauma consultation, and trauma therapy in the same building. Families who complete the trauma consultation but are not exhibiting significant PTSS may be referred to clinicians in the community if the CSA survivor is experiencing other symptoms of emotional and/or behavioral distress unrelated to the CSA. This may minimize the stress often experienced by families who must obtain multiple services by various providers at different locations. The co-location of services also provides continuity of care between the medical and psychological healthcare professionals as they are able reference documentation in the medical record, which often helps reduce the number of times families must repeat their trauma histories. This access also allows for professionals from the medical and behavioral health disciplines to prepare for the family’s visit more effectively. For example, behavioral observations indicative of low mood made during the medical examination may prompt the behavioral health professional to administer an additional depression screening that is not currently part of the Trauma Consultation’s standard protocol. It is also for the CSA survivor and their family, who are experiencing a significant amount of distress, and may unintentionally forget to mention important events or concerns. Therefore, allowing medical and behavioral health professionals to have access to information gathered during the respective appointments may provide a more comprehensive clinical picture of the family. Creating a comprehensive clinical picture of a family is important in selecting an appropriate behavioral health intervention for the survivor and their family.

An Imperfect Process

Although many of CSA cases will complete the forensic interview first, before the family is referred for a medical examination or trauma consultation, this is not always the case; it is not a unidirectional process. For example, families may self-refer a CSA survivor for a trauma consultation before they complete a forensic interview, and speaking with the CSA survivor about allegations of CSA before they complete the forensic interview could interfere with the investigation. This example highlights the importance of clinicians clarifying what aspects of the investigation, assessment, and treatment process have been completed at the start of the visit, as well as emphasizes the value of being able to access records across teams and highlights the benefits of warm handoffs. Although in ideal practice, the team strives to do warm handoffs, the precise estimate of cases that do not follow this trajectory is unknown at this time. Another limitation to the model is that this is one piece of the CAC’s larger MDT; therefore, the youth and their family may interact with many other systems unknown to Nemours which may result in the duplication of services, confusion for the family, and a greater opportunity for children to be lost to follow-up care. Statewide initiatives to improve communication across systems that interact with CSA survivors may improve the likelihood of families successfully connecting with and completing treatment.

Public Health Implications

Nemours remains committed to the MDT response to child abuse and neglect in DE and is involved in the various statewide efforts to streamline the investigation, assessment, and treatment of CSA. Under the leadership of The Child Protection Accountability Commission (CPAC) Committee on the Investigation, Prosecution, and Treatment of CSA, co-chaired by attorneys Haley King, Esq. and Jennifer Donahue, Esq., the MDT partners remain dedicated to improving the multidisciplinary response to CSA through the facilitation of various working groups to identify system weaknesses and strengths in the investigation, prosecution, assessment, and treatment of CSA. Through committee work, MDT members have identified that availability and accessibility of behavioral health services for CSA survivors in DE remains an issue of public health concern. Besides identified local shortages, there is a broader national shortage of behavioral health clinicians, especially those who have specialized training in assessing PTSS and providing evidence-based trauma services. This national shortage may be the result of a lack of opportunity to participate in specialized, evidence-based trauma training due to cost, availability of trainings, and appropriate supervision and consultation after training is completed. Another contributing factor to the growing shortage of behavioral health professionals is secondary traumatic stress, vicarious traumatization, and worker burnout. These are distinctly different processes that practitioners and management need to differentiate, even though they are often similar in presentation.17 The behavioral health professional shortage has frequently compelled long wait times prior to assessment and treatment initiation that may cause families to disengage from the pursuit of behavioral health treatment services. Noted also were gaps in trauma-focused services that address the diverse needs of traumatized families and survivors, such as youth with neurodevelopmental disorders, those who are multilingual, and individuals who reside in rural geographic regions of the state. In an ideal model, all three operational CAC’s across the state would be co-located with medical and behavioral health professionals to facilitate a “warm-handoff” process to ensure continuity of care for CSA survivors and their families; current barriers to co-location replication include financial and staff constraints, and a paucity of medical and mental health professionals skilled in the evaluation and management of CSA across the state. Despite these barriers, Nemours and CAC-based collaborators from the Wilmington location continue to comprehensively serve CSA survivors living in southern DE through creative navigation of transportation and other logistical supports that ensure the northern geographic location of the medical facility is not prohibitive.

Enhancing caregiver engagement in treatment also emerges as a priority. Therefore, coordinated follow-up efforts, such as through assignment of a longitudinal victim advocate to the CSA survivor and their family, may better ensure that families are able to participate in therapeutic services. How best to provide caregivers with anticipatory guidance about the PTSS presents in affected CSA survivors, the difference between a natural reaction to a stressor and PTSS, and destigmatizing abnormal stress-related symptoms to ensure caregivers develop skills to proactively address concerning symptoms remain best-practice issues under review by CPAC committee members. Lastly, providing information to caregivers about evidence-based trauma treatments is necessary to ensure that families are established with effective services that meet their unique needs.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Pauline Corso, Senior Vice President and Chief Operating Officer at Nemours Children’s Health, Delaware Valley for her assistance with editing this manuscript.

References

- 1.Brown, D. W., Anda, R. F., Tiemeier, H., Felitti, V. J., Edwards, V. J., Croft, J. B., & Giles, W. H. (2009, November). Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of premature mortality. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 37(5), 389–396. 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.06.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dube, S. R., Felitti, V. J., Dong, M., Giles, W. H., & Anda, R. F. (2003, September). The impact of adverse childhood experiences on health problems: Evidence from four birth cohorts dating back to 1900. Preventive Medicine, 37(3), 268–277. 10.1016/S0091-7435(03)00123-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hailes, H. P., Yu, R., Danese, A., & Fazel, S. (2019, October). Long-term outcomes of childhood sexual abuse: An umbrella review. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 6(10), 830–839. 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30286-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pérez-Fuentes, G., Olfson, M., Villegas, L., Morcillo, C., Wang, S., & Blanco, C. (2013, January). Prevalence and correlates of child sexual abuse: A national study. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 54(1), 16–27. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2012.05.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scoglio, A. A. J., Kraus, S. W., Saczynski, J., Jooma, S., & Molnar, B. E. (2021, January). Systematic review of risk and protective factors for revictimization after child sexual abuse. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 22(1), 41–53. 10.1177/1524838018823274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Child Advocacy Center Foundation . (2022). Sexual Abuse. Retrieved from: https://cac-foundation.org/sexual-abuse/

- 7.Jones, L. M., Cross, T. P., Walsh, W. A., & Simone, M. (2005, July). Criminal investigations of child abuse: The research behind “best practices”. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 6(3), 254–268. 10.1177/1524838005277440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mart, E. G. (2010). Common errors in the assessment of allegations of child sexual abuse. The Journal of Psychiatry & Law, 38(3), 325–343. 10.1177/009318531003800306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Newlin, C., Steele, L. C., Chamberlin, A., Anderson, J., Kenniston, J., Russell, A., . . . Vaughan-Eden, V. (2015). Child forensic interviewing: Best practices (pp. 1-20). US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. Retrieved from https://www.ojjdp.gov/pubs/248749.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reynolds, C. R., & Kamphaus, R. W. (2015). Behavior assessment system for children–Third Edition (BASC-3). Bloomington, MN: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sachser, C., Berliner, L., Holt, T., Jensen, T. K., Jungbluth, N., Risch, E., et al. Goldbeck, L. (2017, March 1). International development and psychometric properties of the Child and Adolescent Trauma Screen (CATS). Journal of Affective Disorders, 210, 189–195. 10.1016/j.jad.2016.12.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alisic, E., Zalta, A. K., van Wesel, F., Larsen, S. E., Hafstad, G. S., Hassanpour, K., & Smid, G. E. (2014). Rates of post-traumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed children and adolescents: Meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry, 204(5), 335–340. 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.131227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keeshin, B., Byrne, K., Thorn, B., & Shepard, L. (2020, September 5). Screening for trauma in pediatric primary care. Current Psychiatry Reports, 22(11), 60. 10.1007/s11920-020-01183-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deblinger, E., Mannarino, A. P., Cohen, J. A., Runyon, M. K., & Heflin, A. H. (2015). Child sexual abuse: A primer for treating children, adolescents, and their nonoffending parents. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horowitz, L. M., Bridge, J. A., Teach, S. J., Ballard, E., Klima, J., Rosenstein, D. L., et al. Pao, M. (2012, December). Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ): A brief instrument for the pediatric emergency department. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 166(12), 1170–1176. 10.1001/archpediatrics.2012.1276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Posner, K., Brent, D., Lucas, C., Gould, M., Stanley, B., Brown, G., . . . Mann, J. (2008). Columbia-suicide severity rating scale (C-SSRS). New York, NY: Columbia University Medical Center, 10. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Canfield, J. (2005). Secondary traumatization, burnout, and vicarious traumatization: A review of the literature as it relates to therapists who treat trauma. Smith College Studies in Social Work, 75(2), 81–101. 10.1300/J497v75n02_06 [DOI] [Google Scholar]