Abstract

The neural crest (NC) is a vertebrate-specific migratory population of multipotent stem cells that originate during late gastrulation in the region between the neural and non-neural ectoderm. This population of cells give rise to a range of derivatives, such as melanocytes, neurons, chondrocytes, chromaffin cells, and osteoblasts. Because of this, failure of NC development can cause a variety of pathologies, often syndromic, that are globally called neurocristopathies. Many genes are known to be involved in NC development, but not all of them have been identified. In recent years, attention has moved from protein-coding genes to non-coding genes, such as microRNAs (miRNA). There is increasing evidence that these non-coding RNAs are playing roles during embryogenesis by regulating the expression of protein-coding genes. In this review, we give an introduction to miRNAs in general and then focus on some miRNAs that may be involved in NC development and neurocristopathies. This new direction of research will give geneticists, clinicians, and molecular biologists more tools to help patients affected by neurocristopathies, as well as broadening our understanding of NC biology.

Keywords: microRNA, neural crest cells, neurocristopathies

Introduction

Since their discovery in 1993, miRNAs have been associated with a number of physiological and pathological processes [1]. These small RNA molecules (∼22 nt) comprise ∼1–5% of the RNA species in cells but, as a single miRNA can target many genes and many genes can be targeted by multiple miRNAs, it has been estimated that ∼30% of human genes are regulated by miRNAs. As the regulation operated by these elements is subtle and can be subject to additive effects when more than one miRNA is targeting the same mRNA, it is not surprising that these elements have been mainly associated with highly regulated biological processes such as development. In recent years, more and more evidence is pointing in this direction, but many gaps still need to be filled. In particular, more effort is needed in order to include miRNAs in the gene regulatory networks (GRN) that orchestrate the development of different tissues. Together with evidence that links miRNAs and pathological conditions such as cancer and cardiac diseases, a broader understanding of their role in biological processes is required. In this review, we give an insight of what is known about miRNAs during different steps of NC development. We also stress the reason why such knowledge could be beneficial for people affected by diseases of the NC, so-called neurocristopathies (NCP), and for the clinicians treating them. Finally, we suggest further investigations in this direction can be applicable to other aspects of biology, including cancer biology, and might help the development of new innovative drugs for treating these conditions.

Neural crest

The Neural Crest (NC), sometimes referred as the ‘fourth germ layer', is a multipotent population of cells that originate in the region between the neural and non-neural ectoderm of the developing embryo as the neural plate develops [2,3]. The NC is specific to vertebrates and required for the formation of an astonishing number of cells and tissues, such as the craniofacial skeleton, dentine in the teeth, chondrocytes, cardiac septa, the peripheral nervous system, adrenal medulla, and pigment cells [4–6].

To allow the formation of the NC, a complex GRN of secreted growth factors and transcription factors is required. NC formation starts with neural induction, a process orchestrated by a gradient of BMP signalling. Additional signalling by Wnt leads to the transcription of specifiers for the neural plate border (NPB). FGF and Notch signalling are also involved in the expression of NPB specifiers, although these two factors play different roles among various species [2,7–9].

The combined action of these signalling pathways leads to the expression of NPB specifiers, including (but not limited to): Pax3/7, Zic1, nMyc, Tfap2 and Dlx5/6 [2,7,10,11]. A precise balance between neural and non-neural ectoderm, at this stage, is fundamental for the correct formation of NC tissue [2,12]. The next step leading to the formation of NC tissue is the expression of NC specifiers such as FoxD3 and Snai1/2. Their expression is enabled by the action of the NPB specifiers [2,9,13].

One of the most extraordinary properties of NC cells is their ability to undergo an epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT), a property that allows neural crest cells (NCCs) to migrate throughout the developing embryo. EMT requires two steps: delamination and dispersion. Initially, NCCs detach from the neural tube, they then separate from each other to start their migration to the rest of the embryo in a coordinated manner [5,14,15]. To allow the movement of NCCs through the embryo, it is necessary to modulate the activity of cell adhesion molecules, metalloproteinases and the extracellular matrix [2,13,16].

It is important to emphasise that not all the actors involved in NC development have been discovered, and that the GRN that orchestrates this process is constantly being updated [2,3,17]. In addition, other gene regulatory mechanisms, such as the regulation operated by non-coding RNA, need to be considered.

MicroRNAs

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are short RNA molecules of ∼22 nt involved in the post-transcriptional control of gene regulation. They act mainly as repressors of gene expression by binding to the 3′ UTR of targeted mRNAs and either cause stalling of the ribosome, or directly promote degradation of the targeted mRNAs [18].

MiRNAs were first discovered in C. elegans by Lee and colleagues in 1993 [1]. Since then, an increasing number of miRNAs have been characterised, together with evidence of their important roles in regulating gene expression.

The synthesis of miRNAs has been well covered in other reviews [19]. It starts with the action of RNA-Polymerase II, which transcribes a longer primary transcript, called a pri-miRNA. In most cases, the pri-miRNA has stem loops that are recognised by the RNase III, DROSHA, which together with DGCR8, cleaves the pri-miRNA and generates a smaller product of ∼70 nt. This RNA molecule, called the pre-miRNA, is exported to the cytoplasm by the action of Exportin 5. Here, the pre-miRNA is cleaved again by another RNase III, Dicer, which generates a double stranded RNA molecule of ∼22 nt. Generally, only one strand of RNA is used as mature miRNA, while the other is degraded [20].

The mature miRNA is loaded into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), which is then guided to mRNA targets and allows pairing between the ‘seed' sequence of the miRNA (∼7 nt) and the 3′ UTR of the target mRNA. This pairing leads to reduced expression by two mechanisms: the removal of the poly-A tail of the mRNA and the subsequent degradation by exonuclease activity, or the blocking of translation by stalling the ribosome. The stalled ribosome then moves to subcellular organelles called P-bodies. Here, the complex can either be stored or degraded [21–24].

Although this is the main mechanism of biosynthesis of miRNAs, other non-canonical mechanisms are known. For example, Dicer-independent processing of miRNAs can occur using short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) as substrate. In this case AGO2 completes their maturation instead of Dicer [25]. Other non-canonical mechanisms of miRNA biogenesis occur with miRNAs located in introns of transcribed genes (mirtrons) that can be produced during the splicing process and exported by Exportin 5 [26]. Another example is the methylation of the guanosine in position 7 of the capped pre-miRNA, or ‘7-methylguanosine capped pre-miRNA' [27]. This post-transcriptional modification allows the miRNA to be exported directly to the cytoplasm by Exportin 1. In both cases (mirtrons and 7-methylguanosine capped pre-miRNA), the nascent pre-miRNA is not processed by DROSHA/DGCR8.

A different mechanism of action of miRNAs is the so-called RNA activation (RNAa). RNAa is a pathway that promotes the synthesis of mRNA, instead of repressing the translation. This mechanism is mediated by AGO1 that, once it loads the miRNA, is internalised in the nucleus and binds the promoter of specific genes, using the miRNA as guide. This mechanism creates a DNA–RNA duplex (R-loop) in proximity of the promoter that enhances the binding of the RNA-Polymerase II to the DNA [28].

It is important to note that many different miRNAs can target one specific mRNA and specific miRNAs can target more than one mRNA. This mechanism allows for the intricate regulation of gene expression, in particular the presence of more than one miRNA on a single mRNA could generate a stronger silencing effect [18].

The role of miRNAs in NC development

A role for miRNAs during development was first noted in 2003, when Bernstein and colleagues deleted Dicer in mice, observing early embryonic lethality [29]. Other groups have gone on to show miRNAs to be important in many developmental processes, such as, for example, muscle development [30].

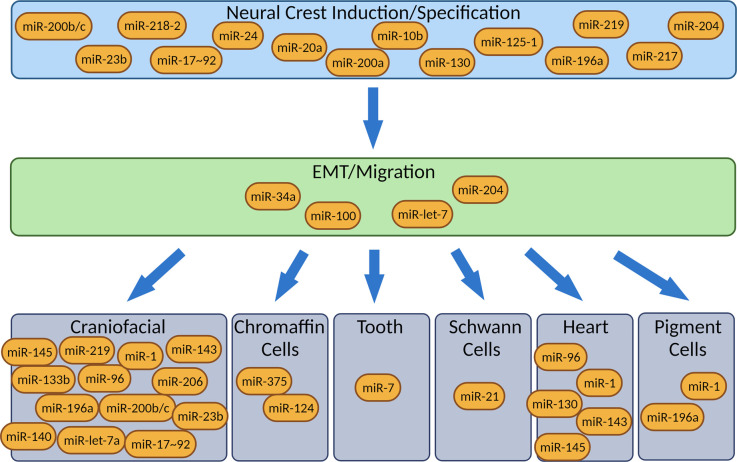

MiRNAs associated with the NC have previously been reviewed by Weiner and colleagues [31]. Here we summarise what is known and look at more recent literature (see Figure 1 and Table 1). A role for miRNAs in NC development was originally shown by knocking out and knocking down Dicer in mice, thus disrupting miRNA biogenesis. It was observed that a NC-specific knockout of Dicer using a Wnt1-CRE is lethal [32]. This effect was due to extensive NC cell death that led to the absence of NC-derived tissues [33]. Similar effects were observed following NC-specific inactivation of DGCR8, an important co-factor of the endonuclease DROSHA. In addition, cardiac defects associated with a defect in the NC were noted [34]. It is important to note that DGCR8 is one of the genes deleted in DiGeorge Syndrome, a Neurocristopathy (NCP) that affects 1 : 4000 children [35].

Figure 1.

MiRNAs described in this review and where they act during Neural Crest development, from induction to differentiation.

Table 1. Neurocristopathies and associated miRNAs, with possible implicated targets.

| Neurocristopathy | Symptoms | miRNA or miRNA-related genes | Implicated target/s | Involvement in NC development | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHARGE Syndrome | Coloboma; Heart defects; Atresia choanae; Growth retardation; Genital abnormalities; Ear abnormalities | let-7 | chd7 | Chondrocyte differentiation | [66] |

| Cleft palate | Incomplete fusion of the bilateral palatal shelves | miR-140 | pdgfra | Chondrocyte differentiation | [67] |

| miR-17∼92 | tbx1, tbx3 | Induction, chondrocyte differentiation | |||

| miR-200b | smad2, snai2, zeb1, zeb2 | Specification | |||

| Congenital central hypoventilation syndrome | CNS development delay; | miR-204 | phox2b | Specification and migration | [58] |

| Hypoxic crisis | |||||

| Craniosynostosis | Premature fusion of two or more skull bones | miR-23b | smad3, smad5 | Induction | [68] |

| miR-133b | egfr, fgfr1 | Chondrocyte differentiation | |||

| Hirschsprung Disease | Swollen belly; | miR-100 | ednrb | EMT [69] | [70] |

| Vomiting; | miR-206 | sdpr | Orofacial development | [63] | |

| Chronic constipation; | miR-214 | plagl2 | [21] | ||

| Fatigue | miR-483 | fhl1 | [71] | ||

| miR-124 | sox9 | Sympathoadrenal development | [72] | ||

| DiGeorge Syndrome | Behaviour problems; | DGCR8 | iRNA pathway | General | [73] |

| Hearing problems; | |||||

| Feeding problems; | |||||

| Congenital heart defects; | |||||

| Hypoparathyroidism | |||||

| Melanoma | Skin tumours | miR-32 | mcl1 | [50] | |

| miR-579-3p | mitf, braf, mdm2 (predicted) | ||||

| miR-200c | bmi1, zeb2, tubb3, abcg5, mdr1 | Specification | |||

| miR-7 | egfr, igf1r, craf | Tooth development | |||

| miR-21 | pten | Schwann cells differentiation [74] | |||

| miR-638 | tp53inp2 | ||||

| miR-34a | bcl2, cdk6, e2f3, mycn | EMT | |||

| miR-100 | trim71 | EMT [69] | |||

| miR-125b | bak1, bcl2, e2f3 | ||||

| miR-192 | zeb2 | ||||

| miR-193b | cdk6, mcl1, bmi1 (predicted) | Orofacial development | |||

| miR-514a | nf1 | ||||

| Neuroblastoma | Sympathetic nervous system (peripheral ganglia and andrenal medulla) tumours | miR-17∼92 | cdkn1a | Induction, chondrocyte differentiation | [49] |

| miR-34a | e2f3, mycn, bcl2, cdk6 | EMT | |||

| miR-204 | bcl2, ntrk2 | Specification and migration | [53] | ||

| miR-193b | mycn, mcl1, ccnd1 | Orofacial development | [51] | ||

| miR-188 | kif1b (predicted) | [52] | |||

| miR-125-1 | e2f3, mcl1 (predicted) | Specification | |||

| miR-501 | bcl2, e2f3, cdk6, ntrk2 (predicted) | ||||

| Neurofibromatosis | Peripheral nerves and Schwann cells tumour | let-7b | lin28b | Chondrocyte differentiation | [75] |

| miR-143 | bcl2, fgf1, igfbp5, camk1d | Cardiac differentiation | |||

| miR-145 | tgfr2, apc, cmyc | Cardiac differentiation | |||

| miR-135 | lzts1, lats2, ndr2, btrc | ||||

| miR-889 | apc | ||||

| miR-128 | nf1 | [76] | |||

| miR-137 | nf1 | ||||

| miR-103 | nf1 |

Many individual miRNAs have now been associated with aspects of NC development. One of the first studies was carried out by Gessert and colleagues [36]. They found that miR-130a, miR-219, miR-23b, miR200b, miR-96 and miR-196a are involved in eye and NC development in Xenopus laevis. By using a morpholino approach, they further showed that miR-130a, miR-219 and miR-23b are essential for the correct development of the eye, while the knock-down of miR-200b, miR-96 and miR-196a cause, other than eye phenotypes, craniofacial defects often associated with NC defects.

In 2013, Avellino and colleagues investigated the role of miR-204 during NC migration. They found that by modulating the expression of miR-204 in Medaka fish embryos, they were able to increase or reduce NCC migration. They also demonstrated that Ankrd13A is a direct target of miR-204 and an important modulator of NCC migration [37]. It is worth noting that, among the human in-silico predicted targets of miR-204, there is Ankrd13C, a paralog of Ankrd13A, and other genes involved in motility and extracellular matrix stability, such as the metalloprotease, Adamts9, the cadherins, Cdh4 and Cdh11, and the collagen, Col5A3. If these in-silico targets were validated in NCCs, it would mean that miR-204 is able to regulate NC migration by targeting several key proteins involved in this process.

These results were partially confirmed by Ward and colleagues [38]. In this study Xenopus laevis embryonic organoids, often termed ‘animal caps’ were induced to become either NC or neural tissue by injection of Wnt1 and Noggin mRNA (to induce NC) or with Noggin alone (to induce neural tissue). The resulting induced-animal caps were then subjected to small RNA next generation sequencing and differential analysis carried out to identify miRNAs specifically expressed in NC tissue. The most abundant miRNA species detected in NC-induced animal caps were miR-219, miR-196a, miR-218-2, miR-10b, miR-204a, miR-130b/c, miR-23, and miR-24, with miR-219 as the most enriched miRNA in NC-induced animal caps, followed by miR-196a. Further experiments using luciferase assays to validate targets of miR-219 found that Eya1 is directly targeted by this miRNA (Ward and Wheeler, unpublished results). Other enriched miRNAs were miR-301a and miR-338-3, but these were also found to be expressed in blastula stage animal caps and could be involved in maintaining pluripotency of the blastula stage ectoderm and putative NC.

Recently, we developed an efficient method to knockout miRNAs using CRISPR/Cas9. To do this, we generate two sgRNAs flanking the miRNA sequence in the genome. Introduction of these sgRNAs plus Cas9 into the embryo leads to deletion of the whole miRNA pri-RNA sequence. Using this method, we have knocked out miR-219 and miR-196a, showing clear NC phenotypes, including craniofacial and pigment abnormalities [39]. The observed phenotype for miR-219 could be due to the direct down-regulation of Pdgfra and Sox6 which have been shown to be targets of miR-219 in oligodendrocyte differentiation and myelination [40].

More recent work in chick, highlighted how miR-20a, miR-200a and miR-217 contribute to NC identity by inhibiting FGF pathway on different levels, reducing the levels of Fgf4, Fgf13 and Fgfr2 in the NC region [41]. In a similar way, other miRNAs have been shown to modulate other key pathways during NC development. For example, Bhattacharya and colleagues showed how the Wnt signalling pathway is modulated by the Lin28/miR-let-7 axis. In particular, high levels of Lin28a promoted by Wnt inhibit the activity of miR-let-7. When NCCs migrate away from the Wnt source, the level of Lin28a is reduced, and this results in an increased level of miR-let-7 activity. The effect leads to the repression of the NC multipotency factors, such as Pax3/7, FoxD3 and cMyc [42].

A number of groups have reported a role for specific miRNAs during NC differentiation [31]. For example, Steeman and colleagues have shown that the highly conserved miR-145, which is transcribed together with miR-143, plays a role during craniofacial development in zebrafish. They speculated that this might be caused by a direct interaction between miR-145 and Sox9b [43]. Zhao and colleagues, also working in zebrafish, have shown that miR-1 plays a role in NC development, as its knock-down produces defects during craniofacial, heart, melanocyte and iridophore development [44].

Other studies have revealed that miR-375 is up-regulated in chromaffin cells from the adrenal medulla, another NC-derived tissue involved in the synthesis of the catecholamines adrenaline and noradrenaline [45]. It has been observed that miR-375 acts as negative regulator of TH and DBH (two key enzymes involved in the synthesis of catecholamines). In particular, the authors showed that miR-375 targets Sp1, the regulator of TH and DBH, in response to stress [46]. Another study conducted by Shtukmaster and colleagues demonstrated that miR-124 is also expressed in developing sympathetic neurons and supports the maintenance of neuronal morphology in sympathoadrenal cells [47].

Figure 1 shows various miRNAs that have been so far identified to potentially play a role in NC specification, migration and differentiation. Future work needs to determine the specific effects of these miRNAs in NC development. In particular, at what point in NC development do they act and how are they regulated? Also, it will be necessary to validate functional and direct targets of the miRNAs involved in NC development. For example, a luciferase assay shows if there is a direct interaction between a miRNA and an mRNA under a non-physiological expression of both miRNA and mRNA, but it does not provide information about the spatial-temporal expression of those two molecules and whether they interact in vivo. To assess the role of a miRNA in the NC-GRN, it is necessary to investigate what factors regulates its expression and verify that the miRNA targets are expressed in the same tissue and at the same stage of development.

miRNAs and neurocristopathies

Neurocristopathies (NCPs) are diseases that can arise due to problems occurring at any time during the development of the NC. These defects can affect a single NC-derived tissue as in albinism that only affects melanocytes, or they can be syndromic and affect several NC-derived tissues as in CHARGE syndrome, which causes coloboma, heart congenital defects and genital abnormalities [48].

MiRNAs are increasingly becoming associated with various NCPs (Table 1). Despite the fact that NCPs are among the most studied genetic diseases, the etiopathogenesis of many NCPs remains to be elucidated, and many factors involved are still to be discovered.

As mentioned before, a well characterised NCP that affects 1 in 4000 to 6000 live births is DiGeorge Syndrome (DGS). The pathology of this condition is characterised by a combination of phenotypes, including cardiac defects, abnormal facies, cleft palate and an absent or hypoplastic thymus. Other common symptoms are renal anomalies, hearing loss and skeletal abnormalities. DGS is often caused by a deletion of 22q11.2, a region that includes the gene that encodes for DGCR8, an important cofactor of DROSHA and essential for proper miRNA biogenesis [35]. The fact that loss of DGCR8 is associated with a syndromic NCP is a strong indication that the miRNA pathway plays an important role at many levels of NC-development.

In recent years, de-regulated miRNAs have been associated with different types of NCPs and NC-derived cancers (Table 1) [49–53]. Some types of cancers, in particular neuroblastoma (NB) and melanoma, are considered NCPs, as they derive from NC tissues. MiRNAs that promote tumour growth are called oncomiRs, while miRNAs known to suppress the malignancy of the tumoral mass are called anti-oncomiRs [54]. MiRNAs associated with NB aggressiveness include the cluster miR-17∼92, which contains five miRNAs (miR-17, miR-18a, miR-19a, miR-20a and miR-92). The overexpression of this cluster in NB is associated with high proliferation and invasiveness, while down-regulation reduces the invasiveness and increases apoptosis in these cells. On the other hand, miR-34a has been shown to have a protective role, as the overexpression of this miRNA induces the arrest of cell proliferation and apoptosis in NB cells. This effect might be due to the targeting of cdkn1a by miR-17-p, while miR-34a is shown to directly target E2F3, which induces cell cycle progression [49]. MiRNAs have also been associated with melanoma. For example, miR-21 is considered an oncomiR, as its expression is often up-regulated in melanoma cells. Its actions involve the inhibition of cell differentiation and apoptosis. Moreover, knock-down of this miRNA in melanoma cells induces apoptosis and enhances the effectiveness of chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Also in this case, other miRNAs have been shown to have oncosupressor activity. MiR-32 is one of these as it promotes the arrest of melanoma growth by inhibiting the expression of MCL-1 and, by doing so, the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathways [50].

Given the increasing number of findings that associate an altered expression of miRNAs and cancer, research groups are starting to give particular attention to regions of DNA harbouring non-translated genes (miRNAs, lncRNAs, piRNAs) and the non-coding regions of mRNAs which are, in fact, important post-transcriptional regulators via interaction with RNA-binding proteins and miRNAs [55,56]. This trend is providing insights into additional facets of gene regulation, mechanisms of development and mechanisms that lead to pathological conditions.

As an example, Bachetti and colleagues (2021) made an association between the miRNA-mediated regulation of phox2B and a pathological condition, congenital central hypoventilation syndrome (CCHS), an NCP that affects the correct development of the CNS and which can cause sudden infant death (SUID) via hypoxic crisis which occurs during sleep [57]. They observed a point mutation in the 3′ UTR of phox2B [58]. This generates a potential new binding site for miR-204, which is already known to target phox2b mRNA in NB cells [59,60]. They speculated that the generation of this new binding site for miR-204 is the cause of the down-regulation of phox2b expression, and that could contribute to the occurrence of SUID [58].

Another NCP that has recently been associated with miRNAs is Hirschsprung Disease (HD), a condition characterised by absence of enteric ganglia. This condition impairs passing stool and can lead to a series of signs such as swollen belly, vomiting, chronic constipation, and fatigue [61]. In 2016, a differential miRNA expression analysis on colon tissue from HD patients was carried out. 168 differentially (up-regulated and down-regulated) expressed miRNAs were identified between Hirschsprung and healthy tissues [62]. In recent years, a number of miRNAs has been associated with HD, including miR-100, miR-206, miR-214 and miR-483. For example, a point mutation in the miR-100 gene has been shown to increase HD susceptibility in a southern China population [63].

These studies are leading the way for a new concept underpinning the diagnosis of rare diseases, in which clinicians analyse regions of the genome producing protein coding mRNAs and/or non-coding RNAs to make predictions. In the future, this approach might be used to treat these conditions before the appearance of symptoms, providing the families of these patients with an alternative that could actually cure the disease [64,65].

Perspectives

The GRN underlying the induction, migration and specification of the NC is under constant revision.

Further studies that focus on the role of non-coding RNA species, such as miRNAs, during NC development are fundamental in order to increase our knowledge of the NC-GRN.

Understanding the role of miRNAs in NC-development can provide clinicians with more powerful tools for the diagnosis of NCPs and other rare diseases.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Amy Kerr and Andrea Münsterberg for useful discussions and comments. M.A. is funded by the European Union's Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program under Marie Sklodowska-Curie (grant agreement No 860635, ITN NEUcrest). G.N.W. is funded by BBSRC grant number BB/T00715X/1

Abbreviations

- BMP

Bone Morphogenic Protein

- CCHS

Congenital Central Hypoventilation Syndrome

- DGS

DiGeorge syndrome

- EMT

Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition

- FGF

Fibroblast Growth Factor

- GRN

Gene Regulatory Network

- lncRNA

long non-coding RNA

- miRNA

microRNA

- MMP

Matrix Metalloproteinases

- mRNA

messenger RNA

- NB

Neuroblastoma

- NC

Neural Crest

- NCCs

Neural Crest Cells

- NCP

Neurocristopathy

- NPB

Neural Plate Border

- ORF

Open Reading Frame

- piRNA

Piwi-interacting RNA

- RISC

RNA Inducing Silencing Complex

- sgRNA

short guide RNA

- SUID

Sudden and Unexpected Infant Death

- UTR

Untranslated Region

Competing Interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests associated with the manuscript.

Open Access

Open access for this article was enabled by the participation of University of East Anglia in an all-inclusive Read & Publish agreement with Portland Press and the Biochemical Society under a transformative agreement with JISC.

Authors Contributions

The authors contributed equally to all the aspects of the preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Lee, R.C., Feinbaum, R.L. and Ambros, V. (1993) The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell 75, 843–854 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-Y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simoes-Costa, M. and Bronner, M.E. (2015) Establishing neural crest identity: a gene regulatory recipe. Development 142, 242–257 10.1242/dev.105445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simoes-Costa, M. and Bronner, M.E. (2013) Insights into neural crest development and evolution from genomic analysis. Genome Res. 23, 1069–1080 10.1101/gr.157586.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martik, M.L. and Bronner, M.E. (2017) Regulatory logic underlying diversification of the neural crest. Trends Genet. 33, 715–727 10.1016/j.tig.2017.07.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mayor, R. and Theveneau, E. (2013) The neural crest. Development 140, 2247–2251 10.1242/dev.091751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Theveneau, E. and Mayor, R. (2012) Neural crest delamination and migration: from epithelium-to-mesenchyme transition to collective cell migration. Dev. Biol. 366, 34–54 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.12.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hockman, D., Chong-Morrison, V., Green, S.A., Gavriouchkina, D., Candido-Ferreira, I., Ling, I.T.C.et al. (2019) A genome-wide assessment of the ancestral neural crest gene regulatory network. Nat. Commun. 10, 4689 10.1038/s41467-019-12687-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hutchins, E.J. and Bronner, M.E. (2018) Draxin acts as a molecular rheostat of canonical Wnt signaling to control cranial neural crest EMT. J. Cell Biol. 217, 3683–3697 10.1083/jcb.201709149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hochgreb-Hagele, T. and Bronner, M.E. (2013) A novel FoxD3 gene trap line reveals neural crest precursor movement and a role for FoxD3 in their specification. Dev. Biol. 374, 1–11 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.11.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schlosser, G. and Ahrens, K. (2004) Molecular anatomy of placode development in Xenopus laevis. Dev. Biol. 271, 439–466 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barembaum, M. and Bronner, M.E. (2013) Identification and dissection of a key enhancer mediating cranial neural crest specific expression of transcription factor, Ets-1. Dev. Biol. 382, 567–575 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.08.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhatt, S., Diaz, R. and Trainor, P.A. (2013) Signals and switches in mammalian neural crest cell differentiation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 5, a008326 10.1101/cshperspect.a008326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Piacentino, M.L., Li, Y. and Bronner, M.E. (2020) Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and different migration strategies as viewed from the neural crest. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 66, 43–50 10.1016/j.ceb.2020.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Batlle, E., Sancho, E., Franci, C., Dominguez, D., Monfar, M., Baulida, J.et al. (2000) The transcription factor snail is a repressor of E-cadherin gene expression in epithelial tumour cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 84–89 10.1038/35000034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cano, A., Perez-Moreno, M.A., Rodrigo, I., Locascio, A., Blanco, M.J., del Barrio, M.G.et al. (2000) The transcription factor snail controls epithelial-mesenchymal transitions by repressing E-cadherin expression. Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 76–83 10.1038/35000025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taneyhill, L.A. and Schiffmacher, A.T. (2017) Should I stay or should I go? Cadherin function and regulation in the neural crest. Genesis 55, 10.1002/dvg.23028 10.1002/dvg.23028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seal, S. and Monsoro-Burq, A.H. (2020) Insights into the early gene regulatory network controlling neural crest and placode fate choices at the neural border. Front. Physiol. 11, 608812 10.3389/fphys.2020.608812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bartel, D.P. (2004) MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 116, 281–297 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00045-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Brien, J., Hayder, H., Zayed, Y. and Peng, C. (2018) Overview of MicroRNA biogenesis, mechanisms of actions, and circulation. Front. Endocrinol. 9, 402 10.3389/fendo.2018.00402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krol, J., Loedige, I. and Filipowicz, W. (2010) The widespread regulation of microRNA biogenesis, function and decay. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11, 597–610 10.1038/nrg2843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu, L., Yuan, W., Chen, J., Zhou, Z., Shu, Y., Ji, J.et al. (2019) Increased miR-214 expression suppresses cell migration and proliferation in hirschsprung disease by interacting with PLAGL2. Pediatr. Res. 86, 460–470 10.1038/s41390-019-0324-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fabian, M.R., Sonenberg, N. and Filipowicz, W. (2010) Regulation of mRNA translation and stability by microRNAs. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 79, 351–379 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060308-103103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Winter, J., Jung, S., Keller, S., Gregory, R.I. and Diederichs, S. (2009) Many roads to maturity: microRNA biogenesis pathways and their regulation. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 228–234 10.1038/ncb0309-228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murchison, E.P. and Hannon, G.J. (2004) miRNAs on the move: miRNA biogenesis and the RNAi machinery. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 16, 223–229 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang, J.S., Maurin, T., Robine, N., Rasmussen, K.D., Jeffrey, K.L., Chandwani, R.et al. (2010) Conserved vertebrate mir-451 provides a platform for Dicer-independent, Ago2-mediated microRNA biogenesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 15163–15168 10.1073/pnas.1006432107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruby, J.G., Jan, C.H. and Bartel, D.P. (2007) Intronic microRNA precursors that bypass Drosha processing. Nature 448, 83–86 10.1038/nature05983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xie, M., Li, M., Vilborg, A., Lee, N., Shu, M.D., Yartseva, V.et al. (2013) Mammalian 5′-capped microRNA precursors that generate a single microRNA. Cell 155, 1568–1580 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramchandran, R. and Chaluvally-Raghavan, P. (2017) miRNA-mediated RNA activation in mammalian cells. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 983, 81–89 10.1007/978-981-10-4310-9_6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bernstein, E., Kim, S.Y., Carmell, M.A., Murchison, E.P., Alcorn, H., Li, M.Z.et al. (2003) Dicer is essential for mouse development. Nat. Genet. 35, 215–217 10.1038/ng1253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mok, G.F., Lozano-Velasco, E. and Munsterberg, A. (2017) microRNAs in skeletal muscle development. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 72, 67–76 10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.10.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weiner, A.M.J. (2018) MicroRNAs and the neural crest: from induction to differentiation. Mech. Dev. 154, 98–106 10.1016/j.mod.2018.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zehir, A., Hua, L.L., Maska, E.L., Morikawa, Y. and Cserjesi, P. (2010) Dicer is required for survival of differentiating neural crest cells. Dev. Biol. 340, 459–467 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.01.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang, T., Liu, Y., Huang, M., Zhao, X. and Cheng, L. (2010) Wnt1-cre-mediated conditional loss of Dicer results in malformation of the midbrain and cerebellum and failure of neural crest and dopaminergic differentiation in mice. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 152–163 10.1093/jmcb/mjq008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chapnik, E., Sasson, V., Blelloch, R. and Hornstein, E. (2012) Dgcr8 controls neural crest cells survival in cardiovascular development. Dev. Biol. 362, 50–56 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lackey, A.E. and Muzio, M.R. (2021) DiGeorge Syndrome, StatPearls, Treasure Island, FL: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gessert, S., Bugner, V., Tecza, A., Pinker, M. and Kuhl, M. (2010) FMR1/FXR1 and the miRNA pathway are required for eye and neural crest development. Dev. Biol. 341, 222–235 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.02.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Avellino, R., Carrella, S., Pirozzi, M., Risolino, M., Salierno, F.G., Franco, P.et al. (2013) miR-204 targeting of Ankrd13A controls both mesenchymal neural crest and lens cell migration. PLoS ONE 8, e61099 10.1371/journal.pone.0061099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ward, N.J., Green, D., Higgins, J., Dalmay, T., Munsterberg, A., Moxon, S.et al. (2018) microRNAs associated with early neural crest development in Xenopus laevis. BMC Genomics 19, 59 10.1186/s12864-018-4436-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Godden, A.M., Antonaci, M., Ward, N.J., van der Lee, M., Abu-Daya, A., Guille, M.et al. (2021) An efficient miRNA knockout approach using CRISPR-Cas9 in Xenopus. Dev. Biol. 483, 66–75 10.1016/j.ydbio.2021.12.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dugas, J.C., Cuellar, T.L., Scholze, A., Ason, B., Ibrahim, A., Emery, B.et al. (2010) Dicer1 and miR-219 Are required for normal oligodendrocyte differentiation and myelination. Neuron 65, 597–611 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.01.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Copeland, J. and Simoes-Costa, M. (2020) Post-transcriptional tuning of FGF signaling mediates neural crest induction. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117, 33305–33316 10.1073/pnas.2009997117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bhattacharya, D., Rothstein, M., Azambuja, A.P. and Simoes-Costa, M. (2018) Control of neural crest multipotency by Wnt signaling and the Lin28/let-7 axis. eLife 7, e40556 10.7554/eLife.40556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Steeman, T.J., Rubiolo, J.A., Sanchez, L.E., Calcaterra, N.B. and Weiner, A.M.J. (2021) Conservation of zebrafish MicroRNA-145 and its role during neural crest cell development. Genes (Basel) 12, 1023 10.3390/genes12071023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhao, N., Qin, W., Wang, D., Raquel, A.G., Yuan, L., Mao, Y.et al. (2021) MicroRNA-1 affects the development of the neural crest and craniofacial skeleton via the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway. Exp. Ther. Med. 21, 379 10.3892/etm.2021.9810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dutt, M., Wehrle, C.J. and Jialal, I. (2022) Physiology, Adrenal Gland, StatPearls, Treasure Island, FL: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gai, Y., Zhang, J., Wei, C., Cao, W., Cui, Y. and Cui, S. (2017) miR-375 negatively regulates the synthesis and secretion of catecholamines by targeting Sp1 in rat adrenal medulla. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 312, C663–CC72 10.1152/ajpcell.00345.2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shtukmaster, S., Narasimhan, P., El Faitwri, T., Stubbusch, J., Ernsberger, U., Rohrer, H.et al. (2016) MiR-124 is differentially expressed in derivatives of the sympathoadrenal cell lineage and promotes neurite elongation in chromaffin cells. Cell Tissue Res. 365, 225–232 10.1007/s00441-016-2395-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vega-Lopez, G.A., Cerrizuela, S., Tribulo, C. and Aybar, M.J. (2018) Neurocristopathies: new insights 150 years after the neural crest discovery. Dev. Biol. 444, S110–SS43 10.1016/j.ydbio.2018.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stallings, R.L. (2009) MicroRNA involvement in the pathogenesis of neuroblastoma: potential for microRNA mediated therapeutics. Curr. Pharm. Des. 15, 456–462 10.2174/138161209787315837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lorusso, C., De Summa, S., Pinto, R., Danza, K. and Tommasi, S. (2020) miRNAs as key players in the management of cutaneous melanoma. Cells 9, 415 10.3390/cells9020415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Roth, S.A., Hald, O.H., Fuchs, S., Lokke, C., Mikkola, I., Flaegstad, T.et al. (2018) MicroRNA-193b-3p represses neuroblastoma cell growth via downregulation of Cyclin D1, MCL-1 and MYCN. Oncotarget 9, 18160–18179 10.18632/oncotarget.24793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ayers, D., Mestdagh, P., Van Maerken, T. and Vandesompele, J. (2015) Identification of miRNAs contributing to neuroblastoma chemoresistance. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 13, 307–319 10.1016/j.csbj.2015.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ooi, C.Y., Carter, D.R., Liu, B., Mayoh, C., Beckers, A., Lalwani, A.et al. (2018) Network modeling of microRNA-mRNA interactions in neuroblastoma tumorigenesis identifies miR-204 as a direct inhibitor of MYCN. Cancer Res. 78, 3122–3134 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-3034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Svoronos, A.A., Engelman, D.M. and Slack, F.J. (2016) Oncomir or tumor suppressor? The duplicity of microRNAs in cancer. Cancer Res. 76, 3666–3670 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mignone, F. and Pesole, G. (2018) mRNA untranslated regions (UTRs). eLS, 1–6 10.1002/9780470015902.a0005009.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chatterjee, S. and Pal, J.K. (2009) Role of 5′- and 3′-untranslated regions of mRNAs in human diseases. Biol. Cell 101, 251–262 10.1042/BC20080104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Matera, I., Bachetti, T., Puppo, F., Di Duca, M., Morandi, F., Casiraghi, G.M.et al. (2004) PHOX2B mutations and polyalanine expansions correlate with the severity of the respiratory phenotype and associated symptoms in both congenital and late onset Central Hypoventilation syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 41, 373–380 10.1136/jmg.2003.015412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bachetti, T., Bagnasco, S., Piumelli, R., Palmieri, A. and Ceccherini, I. (2021) A common 3′UTR variant of the PHOX2B gene Is associated With infant life-threatening and sudden death events in the Italian population. Front. Neurol. 12, 642735 10.3389/fneur.2021.642735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bachetti, T., Di Zanni, E., Ravazzolo, R. and Ceccherini, I. (2015) miR-204 mediates post-transcriptional down-regulation of PHOX2B gene expression in neuroblastoma cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1849, 1057–1065 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2015.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Perri, P., Ponzoni, M., Corrias, M.V., Ceccherini, I., Candiani, S. and Bachetti, T. (2021) A focus on regulatory networks linking MicroRNAs, transcription factors and target genes in neuroblastoma. Cancers (Basel) 13, 5528 10.3390/cancers13215528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lotfollahzadeh, S., Taherian, M. and Anand, S. (2021) Hirschsprung Disease, StatPearls, Treasure Island, FL: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li, S., Wang, S., Guo, Z., Wu, H., Jin, X., Wang, Y.et al. (2016) miRNA profiling reveals dysregulation of RET and RET-regulating pathways in hirschsprung's disease. PLoS ONE 11, e0150222 10.1371/journal.pone.0150222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gunadi, Budi, N.Y.P., Kalim, A.S., Santiko, W., Musthofa, F.D., Iskandar, K.et al. (2019) Aberrant expressions of miRNA-206 target, FN1, in multifactorial Hirschsprung disease. Orphanet. J. Rare Dis. 14, 5 10.1186/s13023-018-0973-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hydbring, P. and Badalian-Very, G. (2013) Clinical applications of microRNAs. F1000Res. 2, 136 10.12688/f1000research.2-136.v1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hanna, J., Hossain, G.S. and Kocerha, J. (2019) The potential for microRNA therapeutics and clinical research. Front. Genet. 10, 478 10.3389/fgene.2019.00478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Evsen, L., Li, X., Zhang, S., Razin, S. and Doetzlhofer, A. (2020) let-7 miRNAs inhibit CHD7 expression and control auditory-sensory progenitor cell behavior in the developing inner ear. Development 147, dev183384 10.1242/dev.183384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schoen, C., Aschrafi, A., Thonissen, M., Poelmans, G., Von den Hoff, J.W. and Carels, C.E.L. (2017) MicroRNAs in palatogenesis and cleft palate. Front. Physiol. 8, 165 10.3389/fphys.2017.00165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ding, H.L., Hooper, J.E., Batzel, P., Eames, B.F., Postlethwait, J.H., Artinger, K.B.et al. (2016) MicroRNA profiling during craniofacial development: potential roles for Mir23b and Mir133b. Front. Physiol. 7, 281 10.3389/fphys.2016.00281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chen, D., Sun, Y., Yuan, Y., Han, Z., Zhang, P., Zhang, J.et al. (2014) miR-100 induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition but suppresses tumorigenesis, migration and invasion. PLoS Genet. 10, e1004177 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhu, Y., Lin, A., Zheng, Y., Xie, X., He, Q. and Zhong, W. (2020) miR-100 rs1834306 A>G increases the risk of Hirschsprung disease in southern Chinese children. Pharmgenomics Pers. Med. 13, 283–288 10.2147/PGPM.S265730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang, G., Guo, F., Wang, H., Liu, W., Zhang, L., Cui, M.et al. (2017) Downregulation of microRNA-483-5p promotes cell proliferation and invasion by targeting GFRA4 in hirschsprung's disease. DNA Cell Biol. 36, 930–937 10.1089/dna.2017.3821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mi, J., Chen, D., Wu, M., Wang, W. and Gao, H. (2014) Study of the effect of miR124 and the SOX9 target gene in hirschsprung's disease. Mol. Med. Rep. 9, 1839–1843 10.3892/mmr.2014.2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Du, Q., de la Morena, M.T. and van Oers, N.S.C. (2019) The genetics and epigenetics of 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Front. Genet. 10, 1365 10.3389/fgene.2019.01365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ni, Y., Zhang, K., Liu, X., Yang, T., Wang, B., Fu, L.et al. (2014) miR-21 promotes the differentiation of hair follicle-derived neural crest stem cells into Schwann cells. Neural Regen. Res. 9, 828–836 10.4103/1673-5374.131599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Amirnasr, A., Verdijk, R.M., van Kuijk, P.F., Kartal, P., Vriends, A.L.M., French, P.J.et al. (2020) Deregulated microRNAs in neurofibromatosis type 1 derived malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Sci. Rep. 10, 2927 10.1038/s41598-020-59789-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Paschou, M. and Doxakis, E. (2012) Neurofibromin 1 is a miRNA target in neurons. PLoS ONE 7, e46773 10.1371/journal.pone.0046773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]