Abstract

Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) is a self-report method that involves intensive longitudinal assessment of behavior and environmental conditions during everyday activities. EMA has been used extensively in health and clinical psychology to investigate a variety of health behaviors, including substance use, eating, medication adherence, sleep, and physical activity. However, it has not been widely implemented in behavior analytic research. This is likely an example of the empirically based skepticism with which behavioral scientists view self-report measures. We reviewed studies comparing electronic, mobile EMA (mEMA) to more objective measures of health behavior to explore the validity of mEMA as a measurement tool, and to identify procedures and factors that may promote the accuracy of mEMA. We identified 32 studies that compared mEMA to more objective measures of health behavior or environmental events (e.g., biochemical measures or automated devices such as accelerometers). Results showed that the correspondence rates varied considerably across individuals, behavior, and studies (agreement rates ranged from 1.8%–100%), and no unifying variables could be identified across the studies that found high correspondence. The findings suggest that mEMA can be an accurate measurement tool, but further research should be conducted to identify procedures and variables that promote accurate responding.

Key words: ecological momentary assessment, validity, health behavior, mHealth

What did you eat for breakfast today? What did you eat this day last week? Under ordinary life circumstances, the answer to the first question will be much more accurate than the answer to the second. Seeking to harness this advantage, many behavioral researchers have turned to ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in their assessment of everyday behavior. EMA is a self-report assessment method that may minimize recall bias when compared to retrospective recall methods (Shiffman et al., 2008). In particular, EMA typically involves self-report of the environment and behavior at multiple times per day and over many days, either at prompted times or after engaging in a target behavior. EMA is set apart from other self-report assessment methods by four characteristics: (1) assessments focus on the participants’ current state or activity; (2) assessments are delivered under specified conditions; (3) assessments involve repeated measures; and (4) assessments are administered in an individual’s natural environment (Stone & Shiffman, 1994).

EMA has been used extensively in health and clinical psychology research (Beckjord & Shiffman, 2014; Shiffman, 2005). For example, Collins et al. (1998) used EMA to assess self-reported alcohol drinking and affect in a sample of heavy drinkers. Participants were asked to report on their behavior, environment, and mood via a hand-held electronic device in response to random prompts delivered throughout the day, at the start of each day, and at the beginning and end of each drinking episode. The authors found that self-reported excessive drinking episodes were moderately correlated with self-reported positive mood prior to initiation of a drinking episode. EMA has also been used to assess physical activity (Bruening et al., 2016; Dunton et al., 2012), binge eating, (Schaefer, Engel, & Wonderlich, 2020a; Schaefer, Smith, et al., 2020b) dietary intake (Mason et al., 2020), symptoms of psychiatric diagnoses (Abel & Minor, 2021; Burke et al., 2020), and suicide risk (Carretero et al., 2020), to name a few health behaviors.

Although EMA was initially developed with paper and pencil methods, researchers implementing EMA have increasingly employed technology-based methods, such as smartphones and personal digital assistants (PDAs; Williams et al., 2021). These mobile EMA (mEMA) methods increase the convenience of reporting given the accessibility of smartphones today. Another advantage of using mEMA over traditional paper and pencil methods is that it reduces the possibility of participants “faking” compliance by recording answers after the designated survey times, as electronically collected data is usually time-stamped (Stone et al., 2002). To this end, mEMA methods have essentially replaced paper and pencil methods of EMA in recent literature (Schüz et al., 2015).

In applied behavioral science, direct observation by carefully trained human observers is the gold standard in measurement methods (Baer et al., 1968; Hartmann & Wood, 1990; Thompson & Borrero, 2021). However, direct observation of behavior is not always feasible nor desirable. For example, following an individual throughout their day as they engage in illicit drug use could pose safety and ethical issues. Direct observation of a typical individual through their work or school day is resource-intensive and may pose privacy issues. In these cases, EMA could be a valuable method for measuring behavior. Despite these practical advantages, EMA has not been widely used in applied behavior analysis. A search of the flagship journal in the field, the Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, for the terms “ecological momentary” resulted in one report. The dearth of EMA methods may be due to the availability of direct observation methods for behaviors commonly studied in applied behavior analysis, such as the public behavior of individuals who are supervised for most of their day.

Expanding behavior analysis to other behavior, like health behavior, may require an expansion of data collection methods beyond direct observation (Critchfield & Reed, 2017; Sturmey, 2020). However, many behavioral scientists are generally suspicious of self-report methods, likely due to the high variability in correspondence of self-report measures compared with more objective measures (Broden et al., 1971; Critchfield et al., 1998; Finney et al., 1998; Fixsen et al., 1972; Prince et al., 2008; Risley & Hart, 1968). For example, one review found correlations between self-reports (including diaries, questionnaires, interviews, and surveys) and objective measures of physical activity (via accelerometers, doubly labeled water, pedometers, etc.) ranged from -0.71 to 0.96 (Prince et al., 2008). As others have pointed out, however, self-reports are not inherently inaccurate measures and may be accurate under specific conditions (Critchfield et al., 1998; Critchfield & Reed, 2017; Risley & Hart, 1968). It is not clear whether EMA would obviate these concerns regarding accuracy, or if specific procedures or factors can be identified to enhance accuracy. For instance, a reduced latency to assessment relative to a target event may increase accuracy, or repeated assessment may alter accuracy over time (Fuller-Tyszkiewicz et al., 2013; van Berkel et al., 2019).

We reviewed the literature comparing mEMA to more objective1 , 2016 measures to evaluate the criterion validity of mEMA (the extent to which mEMA is a valid measure of the events or stimuli being reported) and to explore conditions that may promote accurate reporting. One prior study reviewed the literature that utilized mEMA in conjunction with objective measures of behavior and physiology (Bertz et al., 2018). The authors discussed the benefits and logistics of including objective measures but did not compare their outcomes to mEMA reports. Likewise, other reviews have been conducted evaluating the content validity of EMA, but these reviews included other self-report measures as comparators (Degroote et al., 2020; Marszalek et al., 2014). The current review only includes objective comparators of behavior and environmental events. These objective measures include permanent product records from automated devices (e.g., accelerometers, hearing aids, and geographic positioning systems) and chemical samples (e.g., doubly labeled water or breath samples), as well as reports from independent observers.

Method

Information Sources

We conducted an electronic search of the literature using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., 2009). The search was completed in August 2021, using the PubMed and PsychInfo databases. We used the following keywords (including grammatical variations and synonyms): ecological momentary assessment AND validity, ecological momentary assessment AND concordance, and EMA AND validity. We did not place any restrictions on the year of publication, published language, or peer-review status. Following the identification of articles that met our inclusion criteria, we reviewed their reference sections to identify other relevant articles.

Study Selection

Studies were subject to two types of review: abstract and full text. Studies were selected to go on to a full-text review if a review of their abstract indicated that the authors directly compared mEMA reports of behavior to an objective measure of the same behavior. If it was not clear that a study met inclusion criteria through a review of the abstract, it was sent on to a full text review. Full text reviews included an analysis of the method and results section to determine if the studies met the inclusion criterion (listed below).

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies were included if they were empirical and compared mEMA to objectively measured behavior or environmental events. We chose to exclude studies using other forms of EMA (e.g., paper and pencil, home telephone calls) because they do not reflect the current technological standards widely employed (Bruening et al., 2016). Studies comparing mEMA to other methods of self-report (e.g., timeline follow back or 24-hr recall) were excluded. We also excluded studies that used an objective measure but did not use that objective measure as the comparator to mEMA. For instance, one study used a transdermal alcohol sensor to detect alcohol consumption, but in their analysis of the results they used the EMA reports to quantify the accuracy of the transdermal alcohol sensor and did not provide alcohol sensor data otherwise. Thus, there was not a purely objective measure used as a comparator to EMA.

Data Collection

For each included study, data were collected on the reported agreement between mEMA reports and the objective measure. When multiple analyses were reported in the article, we selected the most direct comparisons to include in the current review. These data were collected independently by the first and second authors.

Interrater Agreement

For 33% of the articles yielded by the search (n = 189), a secondary independent rater rated the articles as “include” or “exclude.” The articles were selected using a random number generator. An agreement was scored if both the first and second raters chose to include or exclude the article. Interrater agreement was calculated by dividing the number of agreements by the total number of disagreements plus agreements. Interrater agreement was 100%.

Results

Article Search

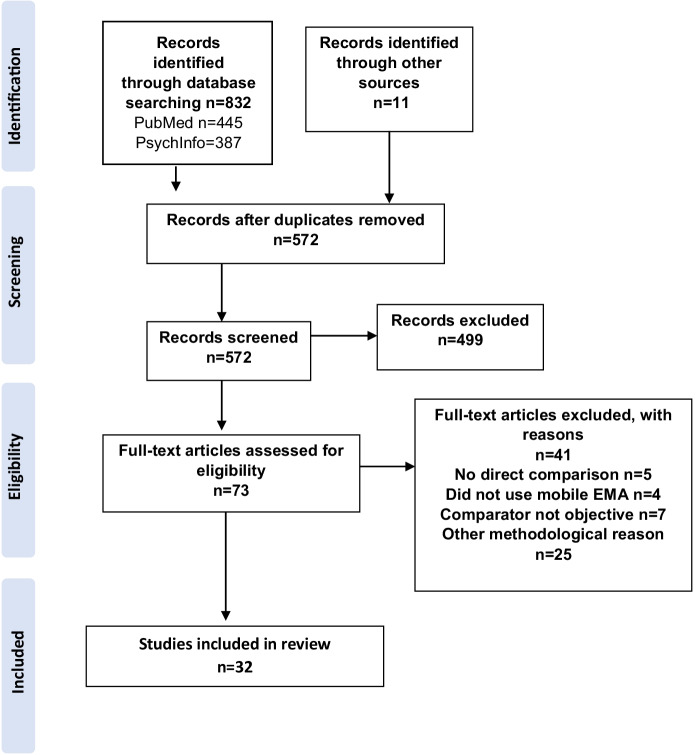

Figure 1 shows the search results and outcomes of the filtering process. The database search yielded a total of 832 articles. After removing duplicates, 572 articles remained. Eleven additional articles were identified through a review of the included articles’ reference sections. An abstract review excluded 499 articles, resulting in 73 articles eligible for a full-text review. The full-text review identified 32 eligible articles and excluded an additional 41.

Fig. 1.

Flow-Diagram of Search Results

Study Characteristics

Studies were broadly divided into four categories based on the measured variables: physical activity and/or sedentary behavior (n = 12), substance-related variables (n = 10), health-related variables (n = 7), and other (n = 3). A variety of statistical approaches were used to report the comparisons, and brief descriptions of each are provided in the footnotes of each table.

Table 1 displays the studies and their outcomes for physical activity. All of these studies compared the results of mEMA with data from an accelerometer (n = 12), although one study used a device that combined a heart-rate monitor and accelerometer (Pannicke et al., 2020), and another used a heart-rate monitor in addition to the accelerometer (Dunton et al., 2005). Measures derived from the devices included activity counts, heart rate, time spent engaged in physical activity or sedentary behavior, in different metabolic equivalents of task (MET) categories and reported body position. Measures derived from the mEMA reports included current activity category (e.g., “I am currently walking”), time spent engaged in physical activity or sedentary behavior, and current body posture. Populations studied ranged from children to older adults.

Table 1.

Studies Comparing EMA Self-Report to Objective Measures of Physical Activity

| Authors & Year | Population | EMA Measure(s) | Comparator (unit) | Results | Author’s Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bruening et al. (2016) | College students | Activity category (strenuous exercise, moderate exercise, mild exercise, sedentary activity) | Accelerometer (activity counts) | Match ratesa ranged from 3.8% (vigorous PA) to 60.3% (sedentary and light PA). Significant differences between activity counts for EMA-reported sedentary and nonsedentary (p < .001), but not across light, moderate, and strenuous PA occasions | “mEMA reports differentiated sedentary from non-sedentary activity, but these reports did not accurately distinguish among objectively measured PA levels” (Bruening et al., 2016, p. 8). |

| Dunton et al. (2011) | Children | Activity category (e.g. active play/sports/ exercising, reading/computer/ homework) | Accelerometer (steps and minutes in MVPA) | Reports of active play, sports, or exercise associated with higher step counts than other reported activities (Adj Wald Fb = 22.16, df = 8, p < 0.001). Mean number of steps recorded while talking on the phone, chores, riding in a car, and something else were significantly greater than mean steps recorded while reading, computer use, homework, watching TV/movies, and playing video games (p < 0.05) | “Overall, construct validity of EMA-reported activities was supported by matching accelerometer data that differentiated between activity types” (Dunton et al., 2011, p. 1210). |

| Dunton et al. (2012) | Adults | Activity category (e.g., running, biking, reading, cooking, standing) | Accelerometer (activity counts, MVPA > 2020 counts/min, SA < 100 counts/min) | MVPA and SA differed significantly across EMA reports (Adj Wald F = 5.63, df = 8, p < 0.001; Adj Wald F = 28.75, df = 8, p < .001) | “Results indicated that time-matched objective activity data (measured by accelerometer) corresponded with EMA self-reports of current activity levels” (Dunton et al., 2012, p. 8). |

| Dunton et al. (2005) | Adolescents (9th–12th graders) | Activity category (nonphysical, walking, and running) | Accelerometer (activity counts) and heart rate monitor (minute-by-minute heart rate) |

Accelerometer agreement rates: 1.8% (exercise), 4.8% (walking), 94.8% (nonphysical activities) Heart rate monitor agreement rates: 56.1% (exercise), 72.7% (walking), 94.5% (nonphysical) |

“Heart rate monitoring and accelerometry distinguished between diary reports of physical . . . and nonphysical activities. Interestingly, the more fine-grained distinction between diary-reported exercise and walking was reflected in heart rate but not actigraph counts” (Dunton et al., 2005, p. 285). |

| Floro et al. (2009) | Children with asthma (aged 9–18) | Activity category (sleep, rest, light, moderate, strenuous) | Accelerometer (1-min epochs) | Spearman correlation coefficientsc for the ¼ hr average data ranged from .06 to .82 (M = .48, SD = .13, p < .0001) | Found “moderate levels of correlation” between measures and “wide variation between participants in the magnitude of the convergent validity estimates” (Floro et al., 2009, p. 161) |

| Knell et al. (2017) | Adults | Min engaged in MPA, VPA, MVPA, and SB | Accelerometer (activity counts) |

Spearman correlation coefficients: .09 (p = .26, VPA), .16 (p < .05, SB), .29 (p < .01, MPA), .31 (p < .001; MVPA) Lin’s CCCd: .07 (95% CI: -.02–.16; SBA), .32 (95% CI: .19–.46; MPA), .28 (95% CI: .15–.41; VPA), and .28 (95% CI: .16–.41; MVPA) |

“The findings of this study support the validity of EMA to measure PA and sedentary behavior” (Knell et al., 2017, p. 10) |

| Maher et al. (2018) | Older adults (aged 60+) | Activity category (PA or SB) | Accelerometer (time spent engaged in PA and SB) | Device-monitored PA was higher (M = 7.09 min, SE = .21) when Ps indicated PA or exercise on EMA than when they did not (M = 2.69 min, SE = 0.12; F = 414.68, df = 1, p < 0.01). Device-measured SB was significantly greater when participants reported sitting (M = 20.91 min, SE = .37) than when they reported not sitting (M = 15.66 min, SE = .26, F = 382.45, df =1, p < .001) | “A 10-day EMA protocol designed to assess PA and SB with random, signal contingent prompting occurring six times per day is both feasible and valid measures of PA and SB” (Maher et al., 2018, p. 8). |

| Pannicke et al. (2020) | Adults | Min engaged in MVPA | Heart rate and accelerometer (time spent in MET categories) | Association between subjective PA and objective MVPA data was βe = .497 (SE = .097, p < .001), no significant differences found between mean subjective and objective PA (t(36) = .076, p = .936) | “Results revealed a significant association between subjective and objective MVPA, as well as largely accurate MVPA estimations” (Pannicke et al., 2020, p. 71) |

| Ponnada et al. (2021) | Adults with Android smartphones | Activity intensity category (sedentary, light/standing, moderate/walking, vigorous) | Accelerometer (activity counts) | Activity counts were lower for reported SB than light/standing (MD = -3.12), lower for light/standing than MVPA (MD = -1.93), and higher for MVPA than SB (MD = 5.05) | “When measuring PA, participants’ μEMA self-report (at a high temporal density) could capture the PA levels consistent with a continuous high-frequency sensor” (Ponnada et al., 2021, p. 7) |

| Romanzini et al. (2019) | Young adults (aged 18–25) | Presence or absence of SB | Accelerometer (activity counts) | Correspondence ratesf were 50.0% (absence of SB) and 76.0% (presence of SB), κg = .42 | “This study demonstrated the viability of using mEMA to obtain information about SB in different contexts and demonstrated good sensibility in the identification of the presence of this outcome in young adults (Romanzini et al., 2019, p. 6).” |

| Weatherson et al. (2019) | Adults with desk-based jobs | Position category (sitting, standing, or moving) | Accelerometer (position) | Agreement rate for position was κ = .713 (p < .001) | “The use of a 5-day EMA protocol with (primarily) random, signal-contingent prompting 5 times during the workday is a valid methodological approach for measuring position/movement in adult office employees” (Weatherson et al., 2019, p. 989) |

| Zink et al. (2018) | Children | Activity category (e.g. “sports or exercise” or “TV, videos, and/or video games” | Accelerometer (time spent engaged in PA and SB) | EMA reports of video games, TV or videos associated with greater time in SB (β =7.3, 95% CI 5.5–9.0, p < .001) | “These findings indicate that EMA may be a promising method for capturing the specific forms of sedentary behavior through self-report with a very short-term recall window” (Zink et al., 2018, p. 7). |

Note.: PA = physical activity, MVPA = moderate to vigorous physical activity, SA = sedentary activity, SB = sedentary behavior, MPA = moderate physical activity, VPA = vigorous physical activity, MET = metabolic equivalents of task.

a Match rate: calculated by determining the number of EMA response categories that matched the accelerometer derived categories (Bruening et al., 2016)

b Adjusted Wald’s F statistic: calculated via regression, provides an indication of the significance of predictor variables in a model, informs whether the explanatory or predictor variable should be included in the model

c Spearman’s correlation coefficient (rs): a nonparametric test in which the x and y values are ranked separately, then the correlation between the two sets of ranks is calculated. Does not quantify the linear relation between the x and y variables, but the monotonic relation (Motulsky, 2018)

d Lin’s concordance correlation coefficient (CCC): quantifies the linear relation between a set of data compared to a “gold standard” and ranges from -1 to 1. Goes one step further than Pearson’s correlation coefficient in that it also quantifies precision and accuracy (Lin, 1989)

e β: a statistical variable calculated using regression that represents the slope of the regression line. Informs you by how many standard deviations, on average, the dependent variable increases when the predictor variable is increased by one standard deviation (Courville & Thompson, 2001; Motulsky, 2018

f Correspondence rates: calculated the same as match rates; compared number of EMA records that reported presence or absence of SB with accelerometer records of presence or absence of SB (Romanzini et al., 2019)

g κ: a measure of interrater reliability that controls for chance agreement between two scores. Ranges from -1 to 1, a negative score indicates that agreement is below chance levels. Does not take into account the magnitude of the differences between reported measures. Appropriate to use when one is seeking to compare two measures of the same variable, but not when one is seeking to compare two different variables (Ranganathan et al., 2017). Values of 0.41–0.60 should be regarded as moderate and a rating of 0.61–0.80 as substantial agreement (McHugh, 2012)

The authors’ conclusions for each study are presented in the last column of Table 1. Conclusions are presented as quotes wherever possible. In general, the conclusions supported the criterion validity of mEMA, although the authors’ standards for validity appeared to rest on conventional thresholds for statistical significance rather than an absolute standard for agreement. For example, several studies utilized statistical tests to determine if objectively measured physical activity differed based on mEMA-indicated activity (Dunton et al., 2011; Dunton et al., 2012; Maher et al., 2018; Pannicke et al., 2020; Zink et al., 2018). Overall, all of the authors indicated that the studies supported the criterion validity of mEMA, with two providing caveats on the limits to that validity. One study reported that the mEMA reports did not differentiate between objectively measured physical activity levels (Bruening et al., 2016), and the other noted that the distinction between mEMA-reported walking and exercise was reflected in heart-rate measures, but not via accelerometer measures (Dunton et al., 2005).

Table 2 displays the studies that investigated variables related to substance use and the outcomes of those studies. Objective comparators to mEMA included salivary cotinine samples, electronic nicotine delivery system (ENDS) devices, sweat patches, breath carbon monoxide (CO) samples, GPS, and transdermal alcohol sensors. Measures obtained through these devices included categorical variables (salivary cotinine samples), frequency of cigarette puffs, frequency of drug use, CO values, ng/mL of salivary cotinine, and location. One study did not specify how salivary cotinine samples were analyzed (Shiffman, 2009). mEMA measures included frequency of ENDS use, mL of e-liquid used, e-cigarette and cigarette puff counts, frequency of smoking sessions, frequency of drug use, cigarettes smoked, and days categorized as “drinking” days or “abstinent” days. Populations studied ranged from teens to adults using a variety of substances (e.g., heroin, amphetamine, e-cigarettes, cigarettes, cocaine, and alcohol).

Table 2.

Studies Comparing EMA Self-Report to Objective Measures of Substance-Related Variables

| Authors & Year | Population | EMA Measure | Comparator (unit) | Results | Authors’ Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Byrnes et al. (2017) | Teens aged 14–16 | Number of alcohol outlets within sight | GPS (number of alcohol outlets within 50–200m) | Bivariate correlationsh: r =.10 (alcohol outlets within 50 m), r = .38 (p < .001, alcohol outlets within 100 m) r =.44 (p < .001, alcohol outlets within 200 m) | N/a |

| Cooper et al. (2019) | Young adults using e-cigarettes (aged 18–29) | Frequency of ENDS use, quantity of e-liquid used (mL), puffs | Salivary cotinine samples (categorical 0, 1, or 2+) | β= .43 (number of days used, event-based assessment), β = .07 (nicotine concentration, event-based assessment), β= .70 (p < .001, puffs per day, random assessment), β= 1.76 (p < .001; number of days used, random assessment) | “While this study supports the use of . . . random EMAs in ENDS research, future studies should explore ways to improve use of event-based EMAs to measure ENDS use” (Cooper et al., 2019, p. 34) |

| Han et al. (2018) | Adults with a heroin or amphetamine-type stimulant dependence | Any drug use | Urine samples (use or nonuse) | Weekly correspondence rates: 51%, 65%, 62%, and 72%, weekly κs: .076, .292, .017, and .103. | “Our study results indicated that the correlations between the EMA and the urine test were poor” (Han et al., 2018, p. 7) |

| Li et al. (2021) | Young adults using e-cigarettes (aged 21–26) | Frequency of puffs, frequency of sessions, quantity of e-liquid used (mL) | ENDS device (Frequency of puffs, mL used) | rrmcsi: 0.49 (p < .001; puff counts), 0.21 (p = .035; ENDS sessions), and 0.06 (mL of nicotine used) | “Our data suggest that the extent of ENDS use assessed by EMA may still underestimate actual use” (Li et al., 2021, p. 847). |

| Linas et al. (2016) | Adults using cocaine and/or heroine | Frequency of drug use | Sweat patches (frequency of drug use) | Lin’s CCCs: .51 (cocaine) and .48 (heroin), percentage agreement: 70% (cocaine) and 72% (heroin) | “This analysis demonstrated moderate to good concordance and inter-rater reliability of reported drug use by EMA when compared to . . . sweat patches” (Linas et al., 2016, p. 7) |

| McClure et al. (2018) | Adolescent and young adult cigarette smokers (aged 15–25) | Cigarettes smoked | Breath CO samples (CO values) | Daily agreement ranged from 55% to 100%, r = .49 (p < .001) | “Though it is likely that cigarettes were being under-reported, objective and self-reported measures of smoking were generally concordant” (McClure et al., 2018, p. 567) |

| Mun et al. (2021) | Adult alcohol drinkers experiencing homelessness | Drinking or abstinent days | Transdermal alcohol sensor (drinking episodes) | κ = .46, p < .05, measures agreed on 73% of days. EMA and SCRAM were correlated at r = 0.46 and 0.78 (day-level and person-level, respectively) | “We found moderate concordance between EMA and SCRAM over 4 weeks among adults with alcohol misuse who were experiencing homelessness. More specifically, the concordance between EMA and SCRAM was modest at the day level but strong at the person level” (Mun et al., 2021, p. 870). |

| Pearson et al. (2017) | African American adult cigarette smokers | E-cigarette puffs | ENDS device (frequency of puffs) | Significant moderate correlation between device and EMA reported puff counts (r = .47, p < .001). Agreement between puff counts was pcj = 0.31 (95% CI 0.15–0.4) for all participants; CCC ranged from .001 to .91 across participants | “The moderate correlation and high agreement between device-reported and self-reported puff data for some participants demonstrate that self-reported e-cigarette puff data may be a feasible method for collecting naturalistic e-cigarette use data, especially among low-level users” (Pearson et al., 2017, p. 6) |

| Schüz et al. (2014) | Adult cigarette smokers | Cigarettes smoked | Breath CO samples | β = .23, p < .001 | “. . . this study found a similarly strong association between EMA CPD and subsequent CO assessments. . . .” (Schüz et al., 2014, p. S91) |

| Shiffman (2009) | Adult cigarette smokers | Cigarettes smoked | Salivary cotinine samples (not specified) and breath CO samples (CO values) | Between salivary cotinine and EMA, β = .33, p < .01; between breath CO and EMA, β = .34, p < .0001 | “The data . . . favored the validity of EMA data, both with regard to digit bias, and also as validated by objective biochemical markers of smoking” (Shiffman, 2009, p. 524) |

Note. GPS = Geographic positioning system, ENDS = electronic nicotine delivery system, CO = carbon monoxide.

h Bivariate correlations: statistical measure of the linear or monotonic relation between two variables. Includes Pearson’s, Spearman’s, and Kendall’s correlation. Byrnes et al. (2017) did not specify which correlation was used.

i Repeated measure correlation (rrmc): estimates the association between paired measures for multiple individuals. Controls for the assumption of independence in the measures and can reveal patterns across individuals’ data (Bakdash & Marusich, 2017). Range from -1 to 1.

j Pearson’s correlation coefficient (pc): quantifies the direction and magnitude of a linear correlation between two variables, ranges from -1 to 1 (Motulsky, 2018).

The last column of Table 2 contains the authors’ conclusions regarding the validity of mEMA, when applicable. Overall, the conclusions were mixed. Most conclusions were favorable, although the authors of two studies described the correspondence results as poor or an underestimation (Han et al., 2018; Li et al., 2021), and the authors of two other studies reported mixed outcomes (Cooper et al., 2019; Mun et al., 2021).

Table 3 displays the studies included in the “health-related” category. Comparators included accelerometers, blood glucose meters, hearing aids, and doubly labeled water. The mEMA reported responses included hours slept, blood glucose level, perceived voice loudness and noise level, and food consumption. The populations included older adults (65+), adolescents with diabetes, adults with hearing aid experience or mild hearing impairment, overweight or obese adults, and obese, pregnant women.

Table 3.

Studies Comparing EMA Self-Report to Objective Measures of Health-Related Variables

| Authors & Year | Population | EMA Measure | Comparator (unit) | Results | Authors’ Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baillet et al. (2016) | Older adults (65+) | Hours slept | Actigraph (total sleep time) | Paired t-testsk showed significant differences (actigraph M = 8.09 hr, self-report M = 6:40 hr, p < .001); average difference was 1 hr and 29 min | “We observed a significant discrepancy between sleep quantity evaluated by actigraphy and EMA” (Baillet et al., 2016, p. 4). |

| Helgeson et al., (2009) | Adolescents with diabetes (aged 13–16) | Blood glucose level | Blood glucose meter (glucose level) | 93% of EMA entries matched glucose meter reports | “The findings of this study demonstrate . . . that this is a feasible method to collect data on . . . how daily events might impact mood, self-care, and blood glucose” (Helgeson et al., 2009, p. 12) |

| Jenstad et al. (2021) | Adults with hearing aid experience | Perceived voice loudness (scale 1–11) | Hearing aid (decibels) | Loudness ratings higher in 65 dB situations (M = 4.39, SE = 0.33) than 50 dB situations (M = 3.76, SE = 0.34) | “We examined construct validity of the ratings and found that ratings did indeed change predictably with the change in acoustics” (Jenstad et al., 2021, p. 8) |

| Martin et al. (2012) | Overweight and obese adults | Food consumption (reported via photos) | Doubly labeled water (EI; energy intake) | Photos underestimated EI by a mean ± SD of 270 ± 748 kcal/day, but estimates did not differ significantly (t(12)= -1.3, p = .22) for customized prompts (see discussion) | “The results indicate that more rigorous EMA methods, which include more prompts delivered around customized mealtimes . . . improve the validity of the RFPM (remote food photography method)” (Martin et al., 2012, p. 895) |

| Most et al. (2018) | Obese, pregnant women | Food consumption (reported via photos) | Doubly labeled water (DLW; total daily energy expenditure) | Photos captured 63.4% ± 2.3% of energy intake calculated via TDEE | “We report here that the SmartIntake application was not able to accurately estimate energy intake compared with TDEE, as assessed by DLW in obese, pregnant women” (Most et al., 2018, p. 662) |

| Timmer et al., (2017) | Adults with mild hearing impairment | Perceived noise level category | Hearing aid (decibels) | rs = .6385; p < .0001. | “This study . . . reinforces the feasibility and validity of using EMA in hearing research” (Timmer et al., 2017, p. 440) |

| Warnick et al. (2020) | Adolescents with Type 1 diabetes (aged 11–21) | Blood glucose monitoring adherence | Blood glucose meter (glucose level, mg/dL) | For time-matched pairs, 41.3% of EMA responses were altered by > 10 mg/dL compared to matching objective value. Bland–Altman plot mean differencel: −5.43 mg/dL (self-reported data, on average, was lower than objective data). Pearson’s r = .3 (p < .01) | “Major findings from this study were that youth often self-reported inaccurate SMBG readings, even when they were aware that their self-reports would be compared with objective readings” (Warnick et al., 2020, p. 285-286). |

Note. TDEE = Total daily energy expenditure.

k Paired t-test: a statistical analysis that compares values from two groups; the p value reports the chance that one would randomly observe a difference as large or larger than the difference observed in the study if there was actually no difference between the two groups; a p value of .05 or smaller in behavioral science indicates a significant difference (Motulsky, 2018).

lBland-Altman plot mean difference: measures the mean difference between two groups (Bland & Altman, 1986).

Table 3 also shows the authors’ conclusions for studies in the “health-related” category. The authors of four studies reported favorable conclusions for the validity of mEMA (Helgeson et al., 2009; Jenstad et al., 2021; Martin et al., 2012; Timmer et al., 2017) and the authors of the remaining three reported inaccurate or discrepant findings.

Table 4 displays the studies included in the “other” category. Objective comparators included geographic information systems (GIS), antisocial behavior reported by staff, and smartphone monitors. The mEMA reported responses included number of observed food outlets, antisocial behavior, and smartphone screen usage duration. Populations studied included adults and juvenile offenders.

Table 4.

Studies Comparing EMA Self-Report to Objective Measures of Other Variables

| Authors & Year | Population | EMA Measure | Comparator (unit) | Results | Authors’ Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elliston et al. (2020) | Adults | Number of food outlets within sight | GIS (number of food outlets within 50 m) | rrmc = 0.17; p < .001 | “Despite finding a small correlation between the self-reported food outlet count and the 50-m GIS count, there is minimal difference between subjective and objective measures of the number of food outlets within the environment” (Elliston et al., 2020, p. 6) |

| Pihet et al. (2017) | Juvenile offenders | Antisocial behavior | Antisocial behavior reported by staff (intensity and frequency) | Association for intensity β = 0.22, p < .001; for frequency, β = 0.44, p = .003 for momentary measures, Spearman’s q = .52, p < .001 for average levels | “These findings suggest EMA allows reliably collecting ecologically valid data in incarcerated juvenile offenders” (Pihet et al., 2017, p. 94) |

| van Berkel et al. (2019) | Adults | Screen usage duration (minutes), unique applications used, number of times screen turned on | Smartphone application (minutes of screen unlocked), number of applications used, number of times screen turned on | MAEm and RMSEn lowest when prompts delivered after phone screen is unlocked (MAE = 12.81 min, RMSE = 25.31 min for screen usage; MAE = 1.80, RMSE = 2.65 for applications used; MAE = 3.65, RMSE = 6.99 for number of times screen turned on) (see discussion for description of conditions) | “Our results show that participants’ recall accuracy was significantly affected by the notification schedule” (van Berkel et al., 2019, p. 126) |

Note. GIS = Geographic Information System, MAE = Mean absolute error, RMSE = Root mean square error.

m Mean average error (MAE): a measure of the average absolute magnitude of the error produced by a model; a smaller number indicates a more accurate model.

n Root mean squared error (RMSE): similar to the MAE, RMSE is a measure of the average absolute magnitude of the error produced by a model, but the difference values are squared, which gives more weight to larger differences. A smaller number indicates a more accurate model (Chai & Draxler, 2014).

Finally, the last column of Table 4 presents the authors’ conclusions in the “other” category. The authors of one study concluded that their data supported the validity of mEMA (Pihet et al., 2017), and the authors of another study reported that accuracy was affected by the prompt-notification schedule (van Berkel et al., 2019). The authors of the final study reported that they found a small correlation between the subjective and objective measures, but still concluded that minimal differences exist between the measures (Elliston et al., 2020).

Discussion

The present review evaluated the correspondence between self-report of behavior and environmental variables via mEMA to more objective measures. The reported correspondence rates varied considerably across individual participants, reported events, and studies. For example, a few studies found agreement rates ranging from very low to high depending on the activity being reported (e.g., vigorous exercise versus sedentary activity; Bruening et al., 2016) or across individual participants (Pearson et al., 2017). Other studies found correspondence rates that were primarily low (e.g., r= .09–.31; Knell et al., 2017) or primarily high (e.g., 93% agreement rate; Helgeson et al., 2009). The current research base suggests that there may be some areas in which mEMA may be used as a valid measure, but further research needs to be conducted to delineate the variables involved in accurate reporting.

Some of the studies in this review suggest that self-report via mEMA has potential to be a valid measure of behavior and environmental events, but problems exist with the current methodology. In particular, the variability of the response–comparator correspondence is a concern, as well as the lack of knowledge surrounding which environmental factors may account for it. Factors that affect the correspondence of EMA reports with objective measures have been explored by a few of the studies in the current review. Zink et al. (2018) noted that correspondence between mEMA and objective measures was higher for boys than it was for girls. Baillet et al. (2016) observed that the discrepancy between self-report and actigraphy-measured sleep was negatively correlated with the subjective degree of positive mood at awakening. Bruening et al. (2016) found that the accuracy of self-reports decreased as accelerometer-measured physical activity level increased, which they posited could be due to social desirability related to overreporting physical activity, or because individuals who are less fit may regard some activities as more intense. Two studies found that participant compliance with mEMA prompts was less likely when accelerometers indicated the participant was engaging in higher levels of physical activity (Dunton et al., 2005; Dunton et al., 2012), and one study found that prompt compliance was higher for white children than children from racial minority groups (Dunton et al., 2011). These findings highlight the importance of considering variables at both the level of the physical and social environment of participants.

Other factors that may affect participant compliance and accuracy include the salience of the events about which the participants are asked to report (Pannicke et al., 2020), the effort required to complete the assessments (Consolvo & Walker, 2003) and experimenter demand characteristics (Finney et al., 1998). In addition, some of the responses may be difficult for participants to describe. For example, describing exercise as “moderate” or “vigorous” may need to be explicitly taught prior to data collection using tact training, where participants are taught to verbally respond to a given set of stimulus conditions (Lowe et al., 2002; Rajagopal et al., 2020; Skinner, 1957). Pannicke et al. (2020) suggest that future research may use objective measures to teach accurate self-reporting of physical activity, similar to a biofeedback model. Supporting the idea of a need for training, Cooper et al. (2019) reported that a participant noted it was difficult to identify specific start and stop times of his near-continuous electronic nicotine delivery system use in certain contexts.

A few studies have experimentally investigated how to increase participant compliance and accuracy with mEMA. Van Berkel et al. (2019) manipulated the scheduled delivery of prompts to assess compliance with mEMA and found that delivering a survey prompt following the participant unlocking their smartphone, as opposed to random or interval contingent prompts, resulted in the most accurate responses. Likewise, Martin et al. (2012) tested both standard prompts that were delivered around generic mealtimes and customized prompts that were tailored to the individual participant’s mealtimes and found that customized prompts increased the concordance of the self-report and objective measures. Future research should continue to explore environmental arrangements that increase the correspondence between objective and subjective measures. Such studies could improve the accuracy of mEMA.

Establishing a standard for what we would consider acceptable correspondence is an important consideration in this discussion and for future research. In the field of applied behavior analysis, interobserver agreements rates of 85% or higher are generally considered acceptable, although this benchmark seems to be based on convention and not a scientific basis (Kennedy, 2005). Applying this standard to the studies in the current review yields just four studies whose agreement rates between EMA and objective measures surpassed this threshold (Dunton et al., 2005; Helgeson et al., 2009;McClure et al., 2018 ; Pearson et al., 2017). It is important to note that three of those four studies reported lower ends of the correspondence range that were considerably lower than 85% (individual participant correspondence of .001, average percent agreement rate of 1.8%, and overall daily agreement of 55%; Pearson et al., 2017; Dunton et al., 2005; McClure et al., 2018, respectively).

Of the four studies that reported agreement rates beyond 85%, three involved adolescent participants (Dunton et al., 2005; Helgeson et al., 2009; McClure et al., 2018), and two of them targeted cigarette smokers (McClure et al., 2018; Pearson et al., 2017). Two of the four studies used interval-based prompts for EMA alone (Dunton et al., 2005; Helgeson et al., 2009), and two studies used both random prompts and event-contingent surveys (McClure et al., 2018; Pearson et al., 2017). Two studies used smartphones (McClure et al., 2018; Pearson et al., 2017), whereas the others used handheld computers and personal digital assistants. No unifying variable could be identified among the four studies that could have led to the higher correspondence rates.

Another way to establish an acceptable correspondence rate involves considering the necessary sensitivity of mEMA, or the smallest amount of change that mEMA can reliably detect. A measure of behavior needs to be sensitive enough to detect meaningful changes in responding. If a measure is only capturing behavior half the time it is occurring, it likely is not sensitive enough to detect important treatment effects. (Correspondence and sensitivity are not to be conflated, but low correspondence between an objective measure and another may indicate a lack of sensitivity.) The necessary sensitivity of a measurement tool may change depending on the specific behavior under study and its severity and frequency. For example, research has shown that complete abstinence from alcohol may not be necessary for recovering alcoholics (Witkiewitz & Tucker, 2020), so recording every instance of alcohol consumption may not be necessary to determine treatment effects. On the other hand, a one-time relapse with another substance, such as an opiate, would be much more concerning because it could prove fatal; therefore, each occurrence of drug use should be recorded (Strang et al., 2003). Li et al. (2021) conducted a sensitivity analysis with four participants who were highly compliant with the mEMA prompts. Despite the high compliance rates, the sensitivity rate of mEMA-reported puffs compared to device-reported puffs varied significantly, with discrepancies ranging from 0 to over 70 per day. Romanzini et al. (2019) also conducted a sensitivity analysis for self-reported versus accelerometer-recorded sedentary behavior and found a sensitivity rate of 84%. Bruening et al. (2016) found that increasing the time window for each mEMA prompt resulted in lower sensitivity across all reported food types consumed. They also found that sensitivity levels were highest for sedentary behavior (91%) and vigorous physical activity (100%) compared to other levels of physical activity. mEMA may be adequately sensitive in some situations for some responses, but without the knowledge of which environmental factors contribute to its sensitivity, it is not yet possible to say for which responses or situations it would be appropriate.

Several studies used statistical significance as the standard for validity. Statistical significance simply means that a p-value is below a pre-set threshold. The p-value indicates the likelihood that the results would have arisen if the null hypothesis were true (e.g., that the EMA measures and the objective measures values are completely unrelated). It does not provide information about the magnitude of the relation between measures. If participants are even providing a rough estimate of their behavior when assessed via EMA, the relation to objective measures may be statistically significant (particularly if the sample size is large enough). Thus, this standard is not sufficient to evaluate the validity of EMA measures. Instead, more direct measures of correspondence should be favored to evaluate validity (Halsey et al., 2015; McShane et al., 2019).

It is interesting that there was little consistency across the studies as to what constituted validity, even when measures of correspondence were used. For example, some studies reported low correlations between objective and subjective measures, yet the authors concluded the self-report measures were valid because the corresponding p-values were statistically significant. Other studies reported similar ranges in correspondence, yet the authors drew conflicting conclusions. For example, Li et al. (2021) concluded that mEMA underestimated ENDS use, whereas Knell et al. (2017) found similar levels of correspondence and concluded that mEMA was a valid measure of physical activity and sedentary behavior. Although the differences in reported statistics across studies do not make for a one-to-one comparison, some discussion of what constitutes validity, perhaps even on a case-by-case basis depending on the response being measured, is warranted.

One limitation with respect to the objective measures of behavior used in these studies is that their accuracy may vary. For example, Dunton et al. (2005) point out that accelerometers worn on the wrist may not be as accurate as accelerometers worn on other parts of the body, because prior research has shown that more accurate energy expenditure estimates are produced by wearing accelerometers on multiple body parts (Chen et al., 2003). Likewise, categorical measures, such as whether a blood glucose check was conducted by a glucose meter, may be more likely to be accurate than some continuous measures (Helgeson et al., 2009). The accuracy of each measure should be taken into account when considering the concordance between the objective and subjective measures.

A final limitation of this review is that many studies did not report direct agreement rates between mEMA and objective measures. Some studies instead reported relations between the two with mEMA reports categorized as predictors of the outcome variable, the objective measures (e.g., as in linear regression or multilevel modeling; Cooper et al., 2019; Dunton et al., 2011; Dunton et al., 2012; Pannicke et al., 2020; Pihet et al., 2017; Schüz et al., 2014; Shiffman, 2009; Zink et al., 2018). In addition, some studies reported statistics that did not portray the magnitude of correspondence between the two measures, but only whether the difference between the two was statistically significant (Cooper et al., 2019; Dunton et al., 2011; Dunton et al., 2012; Pannicke et al., 2020; Pihet et al., 2017; Schüz et al., 2014; Shiffman, 2009). Such reports make interpretation of the agreement less straightforward and limit the conclusions that can be drawn regarding the extent of the correspondence between the measures.

Behavior analysis has the potential to decrease the morbidity and mortality associated with a range of health behaviors (Kaplan et al., 2015; LeBlanc et al., 2020). If we limit ourselves to only studying behavior that aligns with our current research methodology, we will fail at disseminating our science to many populations who would otherwise benefit from it (Vollmer, 2021). The aim of this article was to analyze the current literature base on mEMA and gain an awareness of where it stands, and by how much we can improve the existing methodology. mEMA is a valid measure of behavior and environmental stimuli under some conditions, but more research is needed to identify the specific environmental conditions that promote response accuracy.

Declarations

Conflicts of Interest

We have no known conflicts of interest to disclose.

Availability of Data

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Footnotes

We acknowledge the nuanced discussions surrounding the use of the terms “objective” and “subjective” (Critchfield et al., 1998; Normand, 2017), but chose to use them because they are conventional in this literature.

We thank Ryan Higginbotham for his assistance with interrater agreement and suggestions, and Hailey Donahue, Lindsey Ives, and Alexis Knerr for their comments on this manuscript.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abel DB, Minor KS. Social functioning in schizophrenia: comparing laboratory-based assessment with real-world measures. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2021;138:500–506. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.04.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer DM, Wolf MM, Risley TR. Some current dimensions of applied behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1968;1(1):91–97. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1968.1-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baillet M, Schweitzer P, Pérès K, Catheline G, Swendsen J, Mayo W. Mood influences the concordance of subjective and objective measures of sleep duration in older adults. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. 2016;8:181. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2016.00181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakdash JZ, Marusich LR. Repeated measures correlation. Frontiers in Psychology. 2017;8:456. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckjord E, Shiffman S. Background for real-time monitoring and intervention related to alcohol use. Alcohol Research. 2014;36:9–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertz JW, Epstein DH, Preston KL. Combining ecological momentary assessment with objective, ambulatory measures of behavior and physiology in substance-use research. Addictive Behaviors. 2018;83:5–17. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1(8476):307–310. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(86)90837-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruening, M., van Woerden, I., Todd, M., Brennhoffer, S., Laska, M., & Dunton, G. (2016). A mobile ecological momentary assessment tool (devilSPARC) for nutrition and physical activity behaviors in college students: A validation study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18(7), e209. 10.2196/jmir.5969

- Broden M, Hall RV, Mitts B. The effect of self-recording on the classroom behavior of two eighth-grade students. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1971;4(3):191–199. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1971.4-191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke, T. A., Fox, K., Marin, K., Siegel, D. M., Kleiman, E., & Alloy, L. B. (2020). Real-time monitoring of the associations between self-critical and self-punishment cognitions and nonsuicidal self-injury. Behavioral Research & Therapy, 137, 103775. 10.1016/j.brat.2020.103775

- Byrnes HF, Miller BA, Morrison C, Wiebe DJ, Woychick M, Wiehe SE. Association of environmental indicators with teen alcohol use and problem behavior: Teens observations vs. objectively-measured indicators. Health Place. 2017;43:151–157. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carretero P, Campana-Montes JJ, Artes-Rodriguez A. Ecological momentary assessment for monitoring risk of suicide behavior. Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences. 2020;46:229–245. doi: 10.1007/7854_2020_170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai T, Draxler R. Root mean square error (RMSE) or mean absolute error (MAE)? Arguments against avoiding RMSE in the literature. Geoscientific Model Development. 2014;7:1247–1250. doi: 10.5194/gmd-7-1247-2014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen KY, Acra SA, Majchrzak K, Donahue CL, Baker L, Clemens L, Sun M, Buchowski MS. Predicting energy expenditure of physical activity using hip- and wrist-worn accelerometers. Diabetes Technology & Therapeutics. 2003;5(6):1023–1033. doi: 10.1089/152091503322641088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins, R. L., Morsheimer, E. T., Shiffman, S., Paty, J. A., Gnys, M., & Papandonatos, G. D. (1998). Ecological momentary assessment in a behavioral drinking moderation training program. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 6(3), 306–315. 10.1037//1064-1297.6.3.306

- Cooper MR, Case KR, Hébert ET, Vandewater EA, Raese KA, Perry CL, Businelle MS. Characterizing ENDS use in young adults with ecological momentary assessment: Results from a pilot study. Addictive Behaviors. 2019;91:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consolvo S, Walker M. Using the experience sampling method to evaluate Ubicomp applications. IEEE Pervasive Computing. 2003;2(2):24–31. doi: 10.1109/MPRV.2003.1203750. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Courville T, Thompson B. Use of structure coefficients in published multiple regression articles: β is not enough. Educational & Psychological Measurement. 2001;61(2):229–248. doi: 10.1177/0013164401612006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Critchfield TS, Tucker JA, Vuchinich RE. Self-report methods. In: Lattal KA, Perone M, editors. Handbook of research methods in human operant behavior. Plenum Press; 1998. pp. 435–470. [Google Scholar]

- Critchfield TS, Reed DD. The fuzzy concept of applied behavior analysis research. Behavior Analyst. 2017;40:123–159. doi: 10.1007/s40614-017-0093-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degroote L, DeSmet A, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Van Dyck D, Crombez G. Content validity and methodological considerations in ecological momentary assessment studies on physical activity and sedentary behaviour: A systematic review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition & Physical Activity. 2020;17(1):35. doi: 10.1186/s12966-020-00932-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunton G, Liao Y, Intille S, Spruijt-Metz D, Pentz M. Investigating children’s physical activity and sedentary behavior using ecological momentary assessment with mobile phones. Obesity. 2011;19(6):1205–1212. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunton GF, Liao Y, Kawabata K, Intille S. Momentary assessment of adults’ physical activity and sedentary behavior: Feasibility and validity. Frontiers in Psychology. 2012;3:260. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunton GF, Whalen CK, Jamner LD, Henker B, Floro JN. Using ecologic momentary assessment to measure physical activity during adolescence. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2005;29(4):281–287. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliston KG, Schüz B, Albion T, Ferguson SG. Comparison of geographic information system and subjective assessments of momentary food environments as predictors of food intake: An ecological momentary assessment study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020;8(7):e15948. doi: 10.2196/15948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finney JW, Putnam DE, Boyd CM. Improving the accuracy of self-reports of adherence. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1998;31:485–488. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1998.31-485. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fixsen DL, Phillips EL, Wolf M. Achievement place: The reliability of self-reporting and peer-reporting and their effects on behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1972;5(1):19–30. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1972.5-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floro JN, Dunton GF, Delfino RJ. Assessing physical activity in children with asthma: Convergent validity between accelerometer and electronic diary data. Research Quarterly for Exercise & Sport. 2009;80(2):153–163. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2009.10599549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M, Skouteris H, Richardson B, Blore J, Holmes M, Mills J. Does the burden of the experience sampling method undermine data quality in state body image research? Body Image. 2013;10(4):607–613. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halsey LG, Curran-Everett D, Vowler SL, Drummond GB. The fickle P value generates irreproducible results. Nature Methods. 2015;12(3):179–185. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han H, Zhang J, Hser Y, Liang D, Li X, Wang S, Du J, Zhao M. Feasibility of a mobile phone app to support recovery from addiction in China: Secondary analysis of a pilot study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2018;6(2):Article e46. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.8388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann DP, Wood DD. Observational methods. In: Bellack AS, Hersen M, Kazdin AE, editors. International handbook of behavior modification & therapy. Springer; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Helgeson VS, Lopez LC, Kamarck T. Peer relationships and diabetes: retrospective and ecological momentary assessment approaches. Health Psychology. 2009;28(3):272–282. doi: 10.1037/a0013784. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jenstad LM, Singh G, Boretzki M, DeLongis A, Fichtl E, Ho R, Huen M, Meyer V, Pang F, Stephenson E. Ecological momentary assessment: A field evaluation of subjective ratings of speech in noise. Ear & Hearing. 2021;42(6):1770–1781. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000001071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan BA, Reed DD, Jarmolowicz DP. Effects of episodic future thinking on discounting: Personalized age-progressed pictures improve risky long-term health decisions. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2015;49(1):148–169. doi: 10.1002/jaba.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy CH. Single-case designs for educational research. Pearson; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Knell G, Gabriel KP, Businelle MS, Shuval K, Wetter D, Kendzor D. Ecological momentary assessment of physical activity: Validation study. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2017;19(7):Article e253. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc LA, Lerman DC, Normand M. Behavior analytic contributions to public health and telehealth. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2020;53(3):1208–1218. doi: 10.1002/jaba.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Benowitz-Fredericks C, Ling PM, Cohen JE, Thrul J. Assessing young adults’ ENDS use via ecological momentary assessment and a smart Bluetooth enabled ENDS device. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2021;23(5):842–848. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntaa205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin LI. A concordance correlation coefficient to evaluate reproducibility. Biometrics. 1989;45:255–268. doi: 10.2307/2532051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linas BS, Genz A, Westergaard RP, Chang LW, Bollinger RC, Latkin C, Kirk GD. Ecological momentary assessment of illicit drug use compared to biological and self-reported methods. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2016;4(1):Article e27. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.4470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe CF, Horne PJ, Harris FD, Randle VR. Naming and categorization in young children: Vocal tact training. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2002;78(3):527–549. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2002.78-527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher JP, Rebar AL, Dunton GF. Ecological momentary assessment is a feasible and valid methodological tool to measure older adults’ physical activity and sedentary behavior. Frontiers in Psychology. 2018;9:Article e1485. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01485. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin C, Correa J, Han H, Allen HR, Rood J, Champagne C, Gunturk B, Bray G. Validity of the remote food photography method for estimating energy and nutrient intake in near real-time. Obesity. 2012;20:891–899. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marszalek, J., Morgulec- Adamowicz, N., Rutkowska, I., & Kosmol, A. (2014). Using ecological momentary assessment to evaluate current physical activity. Biomedical Research International, Article e915172. 10.1155/2014/915172.

- Mason TB, Do B, Wang S, Dunton GF. Ecological momentary assessment of eating and dietary intake behaviors in children and adolescents: A systematic review of the literature. Appetite. 2020;144:104465. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2019.104465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure EA, Tomko RL, Carpenter MJ, Treiber FA, Gray KM. Acceptability and compliance with a remote monitoring system to track smoking and abstinence among young smokers. American Journal of Drug & Alcohol Abuse. 2018;44(5):561–570. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2018.1467431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McShane, B. B., Gal, D., Gelman, A., Robert, C., & Tackett, J. L. (2019). Abandon statistical significance. American Statistician, 73(supp1.), 235–245. 10.1080/00031305.2018.1527253

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Prisma Group Reprint—Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Physical Therapy. 2009;89(9):873–880. doi: 10.1093/ptj/89.9.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Most J, Vallo PM, Altazan AD, Gilmore LA, Sutton EF, Cain LE, Burton JH, Martin CK, Redman LM. Food photography is not an accurate measure of energy intake in obese, pregnant women. Journal of Nutrition. 2018;148(4):658–663. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxy009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mun E, Li X, Businelle M, Hébert E, Tan Z, Barnett N, Walters S. Ecological momentary assessment of alcohol consumption and its concordance with transdermal alcohol detection and timeline follow-back self-report among adults experiencing homelessness. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research. 2021;45(4):864–876. doi: 10.1111/acer.14571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh M. Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochemical Medicine. 2012;22(3):276–282. doi: 10.11613/BM.2012.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Motulsky, H. (2018). Intuitive biostatistics: A nonmathematical guide to statistical thinking (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Normand, M. P. (2017). The language of science. Perspectives on Behavior Science, 42(3), 675–688. 10.1007/s40614-017-0123-8

- Pannicke B, Reichenberger J, Schultchen D, Pollatos O, Blechert J. Affect improvements and measurement concordance between a subjective and an accelerometer estimate of physical activity. European Journal of Health Psychology. 2020;27(2):66–75. doi: 10.1027/2512-8442/a000050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson J, Elmasry H, Das B, Smiley S, Rubin L, DeAtley T, Harvey E, Zhou Y, Niaura R, Abrams D. Comparison of ecological momentary assessment versus direct measurement of e-cigarette use with a Bluetooth-enabled e-cigarette: A pilot study. JMIR Research Protocols. 2017;6(5):Article e84. doi: 10.2196/resprot.6501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pihet S, De Ridder J, Suter M. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) goes to jail: Capturing daily antisocial behavior in its context, a feasibility and reliability study in incarcerated juvenile offenders. European Journal of Psychological Assessment. 2017;33(2):87–96. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759/a000275. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prince SA, Adamo KB, Hamel ME, Hardt J, Connor Gorber S, Tremblay M. A comparison of direct versus self-report measures for assessing physical activity in adults: A systematic review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition & Physical Activity. 2008;5:56. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-5-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponnada A, Thapa-Chhetry B, Manjourides J, Intille S. Measuring criterion validity of microinteraction ecological momentary assessment (Micro-EMA): Exploratory pilot study with physical activity measurement. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2021;9(3):e23391. doi: 10.2196/23391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopal S, Nicholson K, Putri TR, Addington J, Felde A. Teaching children with autism to tact private events based on public accompaniments. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2020;54(1):270–286. doi: 10.1002/jaba.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganathan P, Pramesh C, Aggarwal R. Common pitfalls in statistical analysis: Measures of agreement. Perspectives in Clinical Research. 2017;8(4):187–191. doi: 10.4103/picr.PICR_123_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risley TR, Hart B. Developing correspondence between the non-verbal and verbal behavior of preschool children. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1968;1(4):267–281. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1968.1-267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanzini C, Romanzini M, Barbosa C, Batista M, Shigaki G, Ronque E. Characterization and agreement between application of mobile ecological momentary assessment (mEMA) and accelerometry in the identification of prevalence of sedentary behavior (SB) in young adults. Frontiers in Psychology. 2019;10:Article e720. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00720. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer LM, Engel SG, Wonderlich SA. Ecological momentary assessment in eating disorders research: recent findings and promising new directions. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2020;33(6):528–533. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer LM, Smith KE, Anderson LM, Cao L, Crosby RD, Engel SG, Crow SJ, Peterson CB, Wonderlich SA. The role of affect in the maintenance of binge-eating disorder: Evidence from an ecological momentary assessment study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2020;129(4):387–396. doi: 10.1037/abn0000517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schüz N, Walters J, Frandsen M, Bower J, Ferguson S. Compliance with an EMA monitoring protocol and its relationship with participant and smoking characteristics. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2014;16(2):S88–S92. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schüz N, Cianchi J, Shiffman S, Ferguson S. Novel technologies to study smoking behavior: Current developments in ecological momentary assessment. Current Addiction Reports. 2015;2(1):8–14. doi: 10.1007/s40429-015-0039-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S. Dynamic influences on smoking relapse process. Journal of Personality. 2005;73(6):1715–1748. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3506.2005.00364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in studies of substance use. Psychological Assessment. 2009;21(4):486–497. doi: 10.1037/a0017074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Stone AA, Hufford MR. Ecological momentary assessment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2008;4:1–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, B. F. (1957). Verbal behavior. Appleton-Century-Crofts.10.1037/11256-000

- Stone, A. A., & Shiffman, S. (1994). Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in behavioral medicine. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 16(3), 199–202. 10.1093/abm/16.3.199

- Stone AA, Shiffman S, Schwartz JE, Broderick JE, Hufford MR. Patient non-compliance with paper diaries. BMJ. 2002;324:1193–1194. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7347.1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strang J, McCambridge J, Best D, Beswick T, Bearn J, Rees S, Gossop M. Loss of tolerance and overdose mortality after inpatient opiate detoxification: Follow up study. BMJ. 2003;326:959–960. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7396.959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturmey P. Functional analysis in clinical treatment. Elsevier Science & Technology; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, R. H., & Borrero, J. C. (2021). Direct observation. In C. Piazza, H. S. Roane, & W. W. Fisher (Eds.), Handbook of applied behavior analysis (2nd ed.; pp. 191–205). Guilford Press.

- Timmer B, Hickson L, Launer S. Ecological momentary assessment: Feasibility, construct validity, and future applications. American Journal of Audiology. 2017;26:436–442. doi: 10.1044/2017_AJA-16-0126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Berkel N, Goncalves J, Lovén L, Ferreira D, Hosio S, Kostakos V. Effect of experience sampling schedules on response rate and recall accuracy of objective self-reports. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies. 2019;125:118–128. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhcs.2018.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vollmer, T. (2021). Assessment and treatment of behavior disorders: The next 40 years? [Keynote address]. FABA’s 41st Annual Convention, Aventura, FL.

- Warnick J, Western S, Albanese-O’Neill A, Filipp S, Schatz D, Haller M, Janicke D. Use of ecological momentary assessment to measure self-monitoring of glucose adherence in youth with Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Spectrum: A Publication of the American Diabetes Association. 2020;33(3):280–289. doi: 10.2337/ds19-0041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weatherson K, Yun L, Wunderlich K, Puterman E, Faulkner G. Application of an ecological momentary assessment protocol in a workplace intervention: Assessing compliance, criterion validity, and reactivity. Journal of Physical Activity & Health. 2019;16:985–992. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2019-0152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams MT, Lewthwaite H, Fraysse F, Gajewska A, Ignatavicius J, Ferrar K. Compliance with mobile ecological momentary assessment of self-reported health-related behaviors and psychological constructs in adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2021;23(3):Article e1702. doi: 10.2196/17023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K, Tucker JA. Abstinence not required: Expanding the definition of recovery from Alcohol Use Disorder. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research. 2020;44:36–40. doi: 10.1111/acer.14235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zink J, Belcher B, Dzubur E, Ke W, O’Connor S, Huh J, Lopez N, Maher J, Dunton G. Association between self-reported and objective activity levels by demographic factors: Ecological momentary assessment study in children. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2018;6(6):Article e150. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.9592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]