Abstract

Direct isolation and identification of pathogenic viruses from oysters implicated in gastroenteritis outbreaks are hampered by inefficient methods for recovering viruses, naturally occurring PCR inhibitors, and low levels of virus contamination. In this study we focused on developing rapid and efficient oyster-processing procedures that can be used for sensitive PCR detection of viruses in raw oysters. Poliovirus type 3 (PV3) Sabin strain was used to evaluate the efficacy of virus recovery and the removal of PCR inhibitors during oyster-processing procedures. These procedures included elution, polyethylene glycol precipitation, solvent extraction, and RNA extraction. Acid adsorption-elution in which glycine buffer (pH 7.5) was used was found to retain fewer inhibitors than direct elution in which glycine buffer (pH 9.5) was used. RNA extraction in which a silica gel membrane was used was more effective than single-step RNA precipitation for removing additional nonspecific PCR inhibitors. The final 10-μl volume of RNA concentrates obtained from 2 g of oyster tissue (concentration factor, 200-fold) was satisfactory for efficient reverse transcription-PCR detection of virus. The overall detection sensitivity of our method was 1 PFU/g of oyster tissue initially seeded with PV3. The method was utilized to investigate a 1998 gastroenteritis outbreak in California in which contaminated oysters were the suspected disease transmission vehicle. A genogroup II Norwalk-like virus was found in two of three recalled oyster samples linked by tags to the harvest dates and areas associated with the majority of cases. The method described here improves the response to outbreaks and can be used for rapid and sensitive detection of viral agents in outbreak-implicated oysters.

Viral gastroenteritis cases epidemiologically linked to the consumption of raw or undercooked shellfish are probably caused by human enteric viruses. Human sewage discharged from oyster-harvesting vessels was the probable cause identified in one of the previous major outbreak investigations (4, 27). Isolating and identifying etiological viral agents in outbreak-implicated shellfish have been difficult because of low levels of contamination, inefficient recovery during processing, and high concentrations of natural PCR inhibitors in oyster tissues. Development of a sensitive detection method that is also rapid and efficient should improve public health responses to outbreaks because such a method should allow workers to rapidly identify pathogens in contaminated areas and shellfish. It should also facilitate identification of appropriate viral indicators that can be used to prevent future outbreaks.

The methods used to detect enteric viruses in shellfish consist of the following two major elements: (i) separation and concentration of viruses from shellfish tissue components and (ii) detection of viruses in shellfish concentrates by molecular techniques or cell culture infectivity assays. Molecular techniques, such as PCR, are the preferred techniques for detection of viral pathogens that are noncytopathic or nonculturable (e.g., Norwalk-like virus [NLV] and hepatitis E virus). Successful PCR detection relies on effective removal of natural inhibitors and efficient recovery of viruses from oysters during processing. The initial step commonly used to elute viruses from oyster tissue includes direct alkaline elution (13, 14, 16) and acid adsorption-elution (6, 23, 24). Different eluants containing glycine, beef extract, and other compounds have been compared to determine their virus recovery (16) and PCR compatibility (26) characteristics. Complex eluants, such as beef extract, have been shown to contribute additional PCR inhibitors, which decrease the sensitivity of PCR for detection of viruses in environmental samples. The use of butanol-chloroform during extraction has been shown to improve PCR detection (2). When the levels of viral contamination in shellfish are low, it is necessary to include a concentration step, such as polyethylene glycol (PEG) precipitation, organic flocculation, or ultracentrifugation. After concentration, additional steps to remove PCR inhibitors from the processed concentrates are critical in order to have a sensitive PCR test. RNA extraction (12, 22) and nested PCR (10) have been found to improve significantly the sensitivity of virus detection with environmental and clinical samples.

Attempting to avoid PCR inhibitors, workers in previous studies concentrated limited quantities of oysters for the final PCR examination or included sophisticated and extensive processing steps to clean up the concentrates. Processing and analysis of small samples can result in false-negative PCR results when the level of virus is low. Similarly, extensive processing can produce false-negative results by decreasing recovery because of increased manipulation and handling. The objective of this study was to develop rapid and simple processing procedures that can be used to extract and recover enteric viruses efficiently from 25 to 50 g of oyster tissue in a concentrated volume (≥100-fold concentration factor) for sensitive PCR detection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell cultures and viruses.

Human rhabdomyosarcoma (RD) cells were grown to confluence in Eagle’s minimum essential medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, kanamycin (250 μg/ml), and gentamicin (50 μg/ml) in 25-cm2 flasks or 60-mm-diameter dishes. Confluent cells were maintained in the same medium except that the fetal bovine serum concentration was 2%. Poliovirus type 3 (PV3) Sabin strain was grown in RD cells.

Virus recovery.

PV3 was seeded into shucked oysters and was concentrated by the processing procedures described below. The levels of virus recovered from processing were quantified by performing a plaque assay, and then virus recoveries were determined. Serial 10-fold dilutions of each processed concentrate were inoculated onto confluent RD cells in 60-mm-diameter dishes. Cytopathology resulting from viral replication started to appear 36 to 48 h after inoculation, and viral plaques were enumerated 72 h after inoculation.

Oysters and oyster processing.

Commercial-size eastern oysters (Crassostrea virginica) that were 3.5 to 5 in. long were purchased or collected from Mobile Bay in Alabama and Apalachicola Bay in Florida between May 1997 and March 1998. For low-level virus-seeding studies, oysters were depurated with UV-treated seawater for 1 to 2 weeks prior to processing and seeding. Precise levels of viruses in oysters were obtained by inoculating a PV3 stock preparation directly into freshly shucked oysters. After 10 to 15 min of incubation, the seeded oysters were processed by using the procedures described below.

Approximately 3 weeks after harvesting, three samples of recalled outbreak-implicated oysters (Crassostrea gigas) from California were shipped in a chilled, insulated container by overnight express to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Gulf Coast Seafood Laboratory. Immediately after arrival, the oysters were examined, and viable oysters were shucked (without liquor and adductors). Two to four oysters from each sample (weight, slightly more than 25 g) were stored in each sterile container and were frozen at −70°C.

The oyster-processing procedure consisted of the following steps: step 1, homogenization of 25 g of oyster tissue in 175 ml of cold sterile deionized water; step 2, acid adsorption of viruses to oyster solids from the homogenates by adjusting the pH 5.0 after addition of water to reduce the conductivity to less than 2,000 μS (23) (pellets were collected after centrifugation at 2,000 × g for 20 min); step 3, elution of viruses with 175 ml of 0.05 M glycine–0.15 M NaCl (pH 7.5) (the mixture was shaken for 15 min at room temperature, and the supernatant was collected after centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C); step 4, precipitation of viruses by using 8% PEG 8000–0.3 M NaCl at 4°C for 4 h (pellets were collected after centrifugation at 6,700 × g for 30 min, and pellets were suspended in 10 ml of phosphate-buffered saline); step 5, solvent extraction of viruses with an equal volume of 1,1,2-trichloro-1,1,2-trifluoroethane (Freon) (the supernatant was collected after centrifugation at 1,700 × g for 30 min); step 6, precipitation of viruses again by using 8% PEG 8000–0.3 M NaCl at 4°C for 4 h (pellets were collected after centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 15 min); and step 7, RNA extraction and purification of the PEG precipitate by using a silica gel membrane (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, Calif.). A 25-g portion of oyster tissue was concentrated approximately 150-fold to obtain a final RNA volume of 160 μl. During the development of the method, acid adsorption-elution (steps 1 through 3) was compared to direct alkaline elution of oysters homogenized with 10 volumes of 10% tryptose phosphate broth–0.05 M glycine (pH 9.5) (13, 14). RNA extraction and purification with silica gel (step 7) were compared with two other RNA extraction procedures, single-step RNA extraction (5) alone and single-step RNA extraction combined with Sephadex spin column chromatography (19, 22, 25).

RT and PCR.

Reverse transcription (RT) of poliovirus genomic RNA was carried out with a panenterovirus antisense primer (7) at 42°C for 1 h immediately after the RNA was denatured at 98°C for 5 min. Panenterovirus PCR amplification was performed for 25 cycles, with each cycle consisting of 95°C for 1.5 min, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1.5 min, which yielded an amplified 196-bp product. The panenterovirus primer and probe sequences were selected from the highly conserved 5′ nontranslated region and have been described previously (20). The primers used amplify sequences of human enteroviruses, but they did not amplify sequences of several animal enteroviruses tested.

Polymerase regions of NLV genogroup I (G1) and genogroup II (G2) were examined with NLV primers and probes, as described by Ando et al. (1). RT of NLV was carried out in a 30-μl reaction mixture at 42°C for 1 h with consensus primer SR33 for G1 and G2. PCR amplification of G2 was followed by addition of sense primer SR46. Amplification of G1 was carried out with a mixture of three sense primers, SR48, SR50, and SR52. All NLV PCR were performed for 40 cycles, with each cycle consisting of 94°C for 1 min, 50°C for 1 min, and 68°C for 2 min (shorter annealing time and higher extension temperature than Ando et al. [1] used).

Analysis of DNA by gel electrophoresis and hybridization.

The 196-bp PCR product for panenterovirus and the 123-bp PCR product for NLV were analyzed by 1.8% agarose gel electrophoresis, revealed by ethidium bromide (EtBr) staining, and Southern transferred to positively charged nylon membranes (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, Ind.) for oligohybridization. The membranes were prehybridized for 2 to 4 h at 52°C for enterovirus and at 58°C for NLV and were then hybridized with digoxigenin-labelled probes at the same temperature. The hybridization and colormetric detection conditions recommended by the manufacturer (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) were used.

RESULTS

Recovery of virus during oyster processing.

Several processing steps, including virus elution, PEG precipitations, solvent extraction, and RNA extraction, were used, modified, and evaluated in this study in order to effectively remove PCR inhibitors and to efficiently recover viruses from oysters. Virus recoveries were carried out and measured by seeding PV3 Sabin strain (103 to 105 PFU/g of oyster) into oysters, concentrating the PV3 by using the steps described above, and then assaying the sample concentrates with RD cells. For the first step, acid adsorption-elution and direct alkaline elution were compared. A lower percentage of the PV3 (59%) was recovered by acid adsorption-elution than by direct alkaline elution (Table 1); this finding may be attributed to the two centrifugation steps used during acid adsorption-elution rather than the one centrifugation step used during direct alkaline elution. The final recoveries of viruses were not significantly different (10.3 and 10.5%) (Table 1). The viruses in oysters were concentrated more than 100-fold, and approximately 1 log of the seeded PV3 was lost.

TABLE 1.

Poliovirus recoveries from seeded oysters processed by our method, beginning with acid adsorption-elution or direct alkaline elution

| Processing step | Triala | % Recovery of initial inoculum after:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Acid adsorption-elutionb | Direct alkaline elutionc | ||

| Elution | 1 | NDd | ND |

| 2 | 59 | 79 | |

| 3 | ND | ND | |

| First PEG precipitation | 1 | 38 | 53 |

| 2 | 30 | 59 | |

| 3 | 35 | ND | |

| Second PEG precipitation | 1 | 9 | 12 |

| 2 | 8 | 9 | |

| 3 | 14 (10.3)b | ND (10.5)c | |

For trials 1 and 2, oysters were seeded, briefly homogenized, and then divided into 25-g aliquots. The procedure was begun with acid adsorption-elution or direct alkaline elution. The PV3 seeding density was 103 to 105 PFU per g of oyster tissue, and three trials were performed.

The means ± standard deviations for all three trials for the elution, first PEG precipitation, and second PEG precipitation steps are 59%, 34.3% ± 4.0%, and 10.3% ± 3.2%, respectively.

The means for all three trials for the elution, first PEG precipitation, and second PEG precipitation steps are 79, 56.0, and 10.5%, respectively.

ND, not determined.

Oysters were frequently frozen prior to analysis in order to minimize degradation of the viral RNA. The effect of freeze-thawing on the oyster tissue matrix, which might have resulted in poor viral adsorption, was investigated in trial 3 (Table 1). PV3 was seeded into fresh oysters, as well as into oysters that were frozen and thawed three times prior to seeding. The recoveries of PEG-precipitated PV3 from the two kinds of oysters were not significantly different (35% for fresh oysters [Table 1] and 39% for freeze-thawed oysters after the first PEG precipitation, and 14% for fresh oysters [Table 1] and 16% for freeze-thawed oysters after the second PEG precipitation).

Removal of RT-PCR inhibitors from oysters.

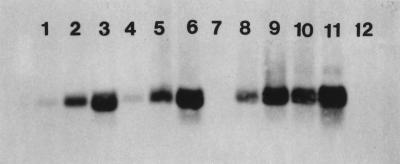

The final RNA concentrates obtained in trials 1 and 2 (Table 1) were compared in order to study RT-PCR interference. The RNA concentrates derived from the process by acid adsorption-elution produced slightly stronger RT-PCR signals than comparable RNA concentrates derived from the process by direct alkaline elution produced (Fig. 1), even when the virus recoveries for the processes were similar (Table 1). Stronger PCR signals may have been due to efficient removal of inhibitors that resulted from the first centrifugation which removed the supernatant and the second centrifugation which removed the oyster solids. Acid adsorption-elution was selected for the final method in this study, because efficient removal of inhibitors resulted in sensitive detection of viruses in final RNA concentrates.

FIG. 1.

RT-PCR-amplified PV3 in oyster concentrates processed by our method, beginning with either acid adsorption elution or direct alkaline elution. Lanes 1 through 7, trial 1 performed with direct alkaline elution (lanes 1 through 3) and acid adsorption-elution (lanes 4 through 6) (lanes 1 and 4, amplified PV3 in 0.025 g of seeded oysters; lanes 2 and 5, PV3 in 0.25 g of seeded oysters; lanes 3 and 6, PV3 in 2.5 g of seeded oysters; lane 7, RT-PCR negative reagent control); lanes 8 through 12, trial 2 performed with direct alkaline elution (lanes 8 and 9) and acid adsorption-elution (lanes 10 and 11) (lanes 8 and 10, amplified PV3 in 0.05 g of oysters; lanes 9 and 11, PV3 in 0.5 g of oysters; lane 12, RT-PCR negative reagent control).

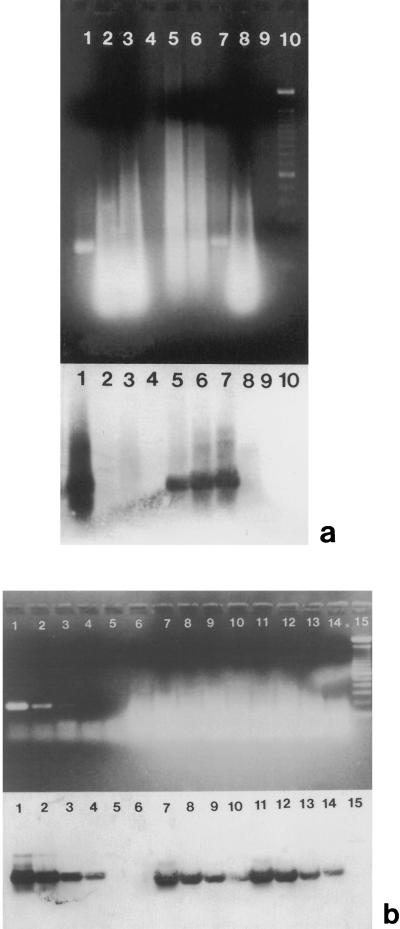

RNA extraction was also evaluated and optimized to efficiently remove RT-PCR inhibitors. The following RNA extraction procedures were evaluated: (i) single-step RNA extraction (procedure 1), (ii) single-step RNA extraction combined with Sephadex G-150 column chromatography (procedure 2), and (iii) RNA adsorption and elution with a silica gel membrane (procedure 3). The efficiency of removing inhibitors from oysters by using the three RNA extraction procedures was evaluated by monitoring the inhibition of Taq DNA polymerase. Thus, in PCR mixtures, equal quantities of PV3 cDNA were mixed with each of the different oyster RNA extracts. Any reduction in the PV3 PCR signal indicated that there were residual inhibitors that were not removed by extraction from the second PEG precipitates. Single-step RNA extraction (procedure 1) did not effectively remove inhibitors from the second PEG precipitates obtained from 3 g of oyster tissue (Fig. 2a, lane 2). RNA-preferential precipitation at pH 4.0 did not improve removal of inhibitors (lane 3) compared with the first precipitation at pH 5.2 (lane 2). When Sephadex G-150 column chromatography was added (procedure 2), however, PCR amplification of PV3 cDNA was improved, as shown in Fig. 2a, lanes 5 through 7. The inhibitors that originally remained in 3 g of oyster extract (Fig. 2a, lane 8) were removed by Sephadex column chromatography combined with single-step RNA precipitation (lane 6). The amplified signals were restored in inverse proportion to the quantity of oyster concentrate incorporated into each PCR mixture (Fig. 2a, lanes 5 through 7).

FIG. 2.

Comparison of RT-PCR amplification of PV3 that were mixed with oyster extracts obtained with three RNA extraction procedures: PCR amplification of PV3 cDNA mixed with oyster extracts obtained with procedures 1 and 2 (a) and RT-PCR amplification of PV3 RNA with and without oyster extracts obtained with procedure 3 (b). We examined amplified PCR products in EtBr-stained gels (top panels) and the corresponding Southern blots hybridized with an inner oligomer labelled with digoxigenin (bottom panels). (a) PCR amplification of PV3 cDNA with oyster RNA extracts obtained with procedure 1 (lanes 2, 3, and 8) and PCR amplification of PV3 cDNA with extracts obtained with procedure 2 (lanes 5 through 7). Lane 1, positive control containing 10 μl of PV3 cDNA; lane 2, 10 μl of PV3 cDNA and 3 g of oyster RNA precipitated at pH 5.2 by procedure 1; lane 3, 10 μl of PV3 cDNA and 3 g of oyster RNA precipitated at pH 4.0 by procedure 1; lane 4, blank; lane 5, 5 μl of PV3 cDNA and 6 g of oyster extract obtained with procedure 2; lane 6, 5 μl of PV3 cDNA and 3 g of oyster extract obtained with procedure 2; lane 7, 5 μl of PV3 cDNA and 0.625 g of oyster extract obtained with procedure 2; lane 8, 5 μl of PV3 cDNA and 3 g of oyster RNA precipitated at pH 5.2 by procedure 1; lane 9, PCR reagent negative control; lane 10, DNA molecular weight standard. (b) RT-PCR amplification of PV3 RNA with and without oyster RNA extracts obtained with procedure 3. Lanes 1 through 4, RT-PCR amplification of PV3 in phosphate-buffered saline (lane 1, 20 PFU; lane 2, 2 PFU; lane 3, 0.2 PFU; lane 4, 0.02 PFU); lane 5, PCR reagent negative control; lane 6, oyster extract negative control; lanes 7 through 10, amplification of PV3 with 1.2 g of oyster extract per reaction mixture (lane 7, 20 PFU; lane 8, 2 PFU; lane 9, 0.2 PFU; lane 10, 0.02 PFU); lanes 11 through 14, amplification of PV3 with 2.1 g of oyster extract per reaction mixture (lane 11, 20 PFU; lane 12, 2 PFU; lane 13, 0.2 PFU; lane 14, 0.02 PFU); lane 15, DNA molecular weight standard.

RNA extraction procedure 3, in which a silica gel membrane was used, was investigated because Sephadex column packing (procedure 2) is complex and can result in inconsistent elution volumes. The total processing time required for procedure 3, in which RNA was adsorbed to and eluted from a silica gel membrane, was less than 1 h. PV3 stock solutions (20, 2, 0.2, and 0.02 PFU) with and without RNA extracts prepared from February Gulf Coast oysters by using procedure 3 were compared for RT-PCR amplification. RNA extracts derived from 1 g (Fig. 2b, lanes 7 through 10) and 2 g (lanes 11 through 14) of oysters were incorporated into each reaction mixture, and we found that these extracts did not interfere with RT-PCR amplification, as shown by the similar detection limits. Up to 3 g of oyster tissue could be extracted and incorporated into each PCR mixture without major interference. The RNAs derived from silica gel membranes were found to be more consistent and reliable for successful PCR amplification than the RNAs obtained from Sephadex column chromatography and single-step RNA extraction. Therefore, RNA extraction with a silica gel membrane (procedure 3) was selected due to its rapid, simple, and reliable removal of inhibitors.

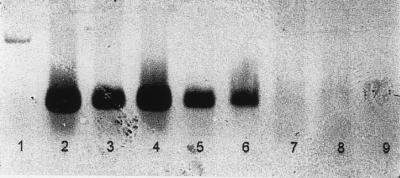

Overall detection sensitivity as determined with low levels of virus seeding.

The overall detection sensitivity of our method was determined by inoculating the PV3 Sabin strain into 25 g of freshly shucked oysters, processing the seeded oysters, and then examining final RNA concentrates by RT-PCR. Experiments were conducted with low initial PV3 seeding densities (280, 58, 5, 1.2, and 0.2 PFU/g of oyster tissue). As shown in Table 2, the PV3 detection limit was established through trial D, in which oysters were seeded with 1.2 PFU of PV3/g. A 10-μl volume of trial D RNA concentrate containing 1.6 PFU was PCR positive, whereas 2 μl of an RNA concentrate containing 0.3 PFU was PCR negative (Table 2 and Fig. 3). The trial D PCR results were consistent with the results of all other trials, especially trial C, in which positive PCR results were obtained with 2 μl of RNA concentrate containing 1.2 PFU in 0.24 g of oyster tissue (Table 2). Overall, the level of virus detectable by the method was 1.2 PFU/g of initially seeded oysters (trial D) or 1.2 PFU of PV3 per PCR mixture (trial C).

TABLE 2.

RT-PCR amplification of PV3 in seeded and processed oyster concentrates

| Trial | Date | Virus seeding density (PFU/g of oyster) | Oyster/virus concn factor | PCR resultsa

|

Total seeded PV3 per reaction mixture (PFU)b

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 μl of RNA concentratec | 2 μl of RNA concentratec | 10 μl of RNA concentratec | 2 μl of RNA concentratec | ||||

| A | January 1998 | 280 | 111 | + | + | 308 | 62 |

| B | February 1998 | 58 | 130 | + | + | 75 | 15 |

| C | February 1998 | 5.0 | 120 | + | + | 6.0 | 1.2 |

| D | March 1998 | 1.2 | 131 | + | − | 1.6 | 0.3 |

| E | March 1998 | 0.2 | 118 | − | − | 0.2 | 0.04 |

| F | March 1998 | 0 | 112 | − | − | 0 | 0 |

Panenterovirus PCR primers were utilized.

The total amount of PV3 per PCR mixture was calculated by using the following formula: virus seeding density × oyster/virus concentration factor × amount of RNA concentrate used (microliters) × 1/1,000.

For each of the trials, 10 and 2 μl of RNA concentrate were derived from 1.1 to 1.3 and 0.22 to 0.26 g of seeded oysters, respectively.

FIG. 3.

RT-PCR amplification of low levels of PV3 in seeded oysters. Lane 1, DNA molecular weight standard; lanes 2 and 3, amplified PV3 in oysters seeded with 58 PFU/g (trial B) (lane 2, 10 μl of RNA concentrate per PCR mixture; lane 3, 2 μl of RNA concentrate per PCR mixture); lanes 4 and 5, amplified PV3 in oysters seeded with 5 PFU/g (trial C) (lane 4, 10 μl of RNA concentrate per PCR mixture; lane 5, 2 μl of RNA concentrate per PCR mixture); lanes 6 and 7, amplified PV3 in oysters seeded with 1.2 PFU/g (trial D) (lane 6, 10 μl of RNA concentrate per PCR mixture; lane 7, 2 μl of RNA concentrate per PCR mixture); lane 8, control containing 10 μl of RNA concentrate (trial F); lane 9, RT-PCR reagent negative control.

Virus detection in outbreak-implicated oysters.

The method described above was applied to oysters implicated in a gastroenteritis outbreak consisting of 171 cases that occurred in 44 clusters located in seven counties of California (3). Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, chills, stomach cramps, and low-grade fevers were common symptoms among the patients who consumed raw or undercooked oysters harvested from Tomales Bay in California. As traced by the oyster-tagging system, illness-associated oysters were harvested by certified growers from approved areas in the mid to outer bay starting on 29 April 1998 (3). The harvested oysters (unshucked) were presumably stored under conditions set by National Shellfish Sanitation Program for human consumption. Three recalled oyster samples, selected on the basis of their harvest dates and proximity to the majority of cases, were shipped to the FDA Gulf Coast Seafood Laboratory for viral pathogen analysis. A 25-g aliquot of each shucked oyster tissue was processed individually, and final RNA concentrates were examined by RT-PCR for the presence of enterovirus, as well as NLV G1 and G2. NLV G2 was found in two samples, samples 87 and 90, by using RT-PCR and Southern hybridization (Table 3). When panenterovirus PCR primers were used, we found enterovirus in sample 88. The NLV G2 in samples 87 and 90 was characterized, and the identity was confirmed by nucleotide sequencing (data not shown). The fact that all three oyster samples contained human enteric viruses indicated that the oysters were contaminated with human wastes.

TABLE 3.

Detection of NLV and enterovirus in outbreak-implicated oysters

| Sample | Harvest date | Harvest area | PCR results

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NLV

|

Enterovirus | ||||

| G1 | G2 | ||||

| 87 | 5 May 1998 | A | − | + | − |

| 88 | 7 May 1998 | A | − | − | + |

| 90 | 5 May 1998 | B | − | + | − |

| Reagent control | − | − | − | ||

| Oyster controla | − | − | − | ||

Depurated Gulf Coast oysters were processed and examined between processing of outbreak samples to ensure that no cross-contamination occurred.

DISCUSSION

In the United States, identification of viral etiological agents in outbreak-implicated shellfish has not been successful except in rare instances (8, 15). The lack of efficient methods for recovering viruses and removing inhibitors from shellfish hinders sensitive PCR detection of viruses, especially in shellfish contaminated with low levels of viruses. In this study we improved the processing procedures by streamlining the steps required to obtain reasonable virus recovery and effective inhibitor removal for the final 150- to 200-fold concentrates used. Acid adsorption-elution was found to have a greater ability to remove inhibitors, possibly due to the two-step process used, although direct alkaline elution with glycine buffer (pH 9 to 10) is quick and commonly used by many researchers (11, 13, 14, 16, 17). In addition, smaller pellets of second PEG precipitates were observed after processing with the acid adsorption-elution procedure. The smaller pellets were dissolved easily by RNA buffer during the final step of RNA extraction.

The final RNA extraction step is indispensable for virus detection in environmental samples as it effectively removes inhibitors and extensively concentrates the final volume (22). Numerous RNA extraction procedures have been described, and some of them have been applied to oyster concentrates. These procedures include the use of phenol-chloroform extraction followed by cetyltrimethylammonium bromide purification (2, 15) and the use of glass powder (13, 14). In our study, a rapid single-step RNA extraction procedure failed to remove inhibitors from the second oyster PEG precipitates. When Sephadex column chromatography preceded single-step RNA extraction, RT-PCR amplification of viruses in processed concentrates was restored. However, this two-step RNA processing (procedure 2) was time-consuming and complex. A third procedure, in which silica gel was used to adsorb and elute RNA, proved to be timely, required less than 1 h, and produced quality RNA more consistently and reliably. This finding is similar to the finding of a study in which the authors showed that guanidinium-silica gel extraction was superior to chromatography combined with RNA precipitation, and also to phenol-chloroform extraction combined with cetyltrimethylammonium bromide purification for detecting virus in fecal specimens (12). In our study, the RNA extraction step did not discriminate between viral RNAs and residual oyster RNAs. Residual oyster RNAs did not interfere with RT-PCR, but they masked and hindered the observation of small amplified products in EtBr-stained gels (Fig. 2). The use of Southern hybridization or the use of Microcon 100 (Amicon Inc., Beverly, Mass.) for product purification before gel electrophoresis resolved the problem. Southern hybridization is strongly recommended for detecting virus in environmental samples because of its high level of sensitivity (it is approximately 1-log more sensitive than EtBr-stained gel electrophoresis) and specificity for recognizing specific amplified targets by nucleic acid hybridization.

The virus recoveries obtained with the method developed in this study (Table 1) were measured by using a cell culture infectivity assay during PV3 seeding experiments (105 to 103 PFU of PV3/g). Since low levels of PV3 in oysters frequently did not produce enough plaque counts on a 60-mm-diameter dish, the efficient way to detect low levels of PV3 was to use RT-PCR, not the cell culture infectivity assay. Using the RT-PCR assay in five low-level PV3 seeding experiments (virus levels, 102 to 10−1 PFU/g) (Table 2), we concluded that the overall limit of virus detection in oysters by the method was 1.2 PFU/g of oysters initially seeded with PV3. Because oysters were depurated first and controls did not contain detectable levels of enterovirus (trial F), we believe that the seeded 1.2 PFU/g represented the actual virus level in the oysters. Background enterovirus was not present in the control oysters simultaneously examined during the January and February trials (data not shown). As the ratio of virus particles to infectivity was greater than one, the method could detect 1 PFU/g of oyster tissue, even when there was a total loss of approximately 1 log of virus during processing. The sensitivity of detection in this study (1 PFU/g) was determined by using single-round PCR with oysters seeded initially and processed by using all of the steps; our method is considered sensitive and comprehensive compared to previously described methods. For example, a sensitivity of 1 PFU of PV1 was reported for a partial processing procedure from nucleic acid extraction to RT-PCR (13). Our low detection limit may be attributed to enhanced removal of inhibitors from the final 10-μl volume of RNA concentrates obtained from 1.5 to 2 g of oyster tissue. Twenty-five to 50 g of oyster tissue can be processed and the final RNA concentrates can be obtained within 10 to 12 h.

As oyster biochemistry differs in different seasonal environments, the inhibitor levels may vary. A previous study showed that the levels of PCR inhibitors in oysters collected from polluted waters were different from the levels in oysters that have been depurated (13). To ensure that oyster biochemical variables were taken into consideration, our method was tested periodically with oysters collected in different months and seasons from Gulf Coast waters. In particular, oysters harvested from January to March were utilized in five trials with low levels of virus seeding (Table 2). During cold months, oysters may accumulate more inhibitory substances, perhaps due to increased storage of glycogen (9). If not removed properly by processing, the inhibitors may alter the virus detection limit.

The method which we developed was successfully used to examine NLV in illness-associated Tomales Bay oysters. Environmental and clinical specimens (oysters and patient stools) were processed and examined independently by workers in different laboratories. We found 100% identity in 175 nucleotide sequences in the capsid gene of NLV in oysters and a patient when NLV capsid primers were utilized (21). During our examination of an NLV strain in implicated oysters, depurated control oysters were always negative for NLV, which indicated that no contaminant was introduced by the processing and examination procedures. Using 1.4 to 1.5 g of oyster tissue, we consistently detected NLV G2 amplicons in concentrated 10-μl volumes of RNAs obtained from two concentrates, samples 87 and 90. Perhaps because of low levels of virus contamination, NLV G2 signals in 2-μl portions of RNA sample concentrates were not observed consistently. It was unlikely that a false-negative NLV result occurred in sample 88 (due to remaining inhibitors), because enterovirus in the same sample was well amplified.

For decades (even in the 1980s and early 1990s), the etiology of the majority of illnesses associated with shellfish consumption was unknown (18). In recent years, NLV etiological agents have been found mostly in patient stool samples but not in illness-implicated shellfish. The ability to find low levels of enteric viruses in shellfish allows more accurate assessment of shellfish as disease transmission vehicles. The method which we developed should improve the public health response to viral illnesses associated with oyster consumption by permitting rapid isolation and sensitive identification of viral agents in oysters implicated in illnesses.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the FDA and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency through the Gulf of Mexico Program (EPA IAG identification no. DW75945791-01-0).

We thank D. W. Cook, R. M. McPhearson, G. P. Hoskin, and P. S. Schwartz of the FDA Office of Seafood for valuable critiques during preparation of the manuscript. We thank California Department of Health Services and FDA shellfish specialists in the Pacific region for providing the recalled oyster samples and illness reports. The assistance of F. A. Bencsath, W. Burkhardt III, and J. L. Mullendore in making this publication possible is also appreciated.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ando T, Monroe S S, Gentsch J R, Jin Q, Lewis D C, Glass R I. Detection and differentiation of antigenically distinct small round-structured viruses (Norwalk-like viruses) by reverse transcription-PCR and Southern hybridization. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:64–71. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.1.64-71.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atmar R L, Neill F H, Romalde J L, Le Guyader F, Woodley C M, Metcalf T G, Estes M K. Detection of Norwalk virus and hepatitis A virus in shellfish tissues with the PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:3014–3018. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.8.3014-3018.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.California Department of Health Services. Gastroenteritis associated with Tomales Bay oysters: investigation, prevention, and control. California morbidity. Berkeley: California Department of Health Services; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Viral gastroenteritis associated with eating oysters—Louisiana, December 1996-January 1997. Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep. 1997;46:1109–1112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocynate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chung H, Jaykus L A, Sobsey M D. Detection of human enteric viruses in oysters by in vivo and in vitro amplification of nucleic acids. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:3772–3778. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.10.3772-3778.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Leon R, Shieh Y-S C, Baric R S, Sobsey M D. Detection of enteroviruses and hepatitis A virus in environmental samples by gene probes and polymerase chain reaction. San Diego, Calif: American Water Works Association; 1990. pp. 833–853. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Desenclos J A, Klontz K C, Wilder M H, Nainan O, Margolis H S, Gunn R A. A multistate outbreak of hepatitis A caused by the consumption of raw oysters. Am J Public Health. 1991;81:1268–1272. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.10.1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galtstoff P S. The American oyster, Crassostrea virginica. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, U.S. Government Printing Office; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green J, Henshilwood K, Gallimore C, Brown D, Lees D N. A nested reverse transcriptase PCR assay for detection of small round-structured viruses in environmentally contaminated molluscan shellfish. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:858–863. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.3.858-863.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hafliger D, Gilgen M, Luthy J, Hubner P. Seminested RT-PCR systems for small round structured viruses and detection of enteric viruses in seafood. Int J Food Microbiol. 1997;37:27–36. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(97)00041-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hale A D, Green J, Brown D W. Comparison of four RNA extraction methods for the detection of small round structured viruses in faecal specimens. J Virol Methods. 1996;57:195–201. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(95)01966-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lees D N, Henshilwood K, Dore W J. Development of a method for detection of enteroviruses in shellfish by PCR with poliovirus as a model. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:2999–3005. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.8.2999-3005.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lees D N, Henshilwood K, Green J, Gallimore C I, Brown D W. Detection of small round-structured viruses in shellfish by reverse transcription-PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:4418–4424. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.12.4418-4424.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.LeGuyader F L, Neill F H, Estes M K, Monroe S S, Ando T, Atmar R L. Detection and analysis of a small round-structured virus strain in oysters implicated in an outbreak of acute gastroenteritis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:4268–4272. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.11.4268-4272.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewis G D, Metcalf T G. Polyethylene glycol precipitation for recovery of pathogenic viruses, including hepatitis A and human rotavirus, from oyster, water, and sediment samples. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:1983–1988. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.8.1983-1988.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pina S, Puig M, Lucena F, Jofre J, Girones R. Viral pollution in the environment and in shellfish: human adenovirus detection by PCR as an index of human viruses. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:3376–3382. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.9.3376-3382.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rippey S R. Infectious diseases associated with molluscan shellfish consumption. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1994;7:419–425. doi: 10.1128/cmr.7.4.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schwab K J, De Leon R, Sobsey M D. Development of PCR methods for enteric virus detection in water. Water Sci Technol. 1993;27:211–218. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shieh Y-S C, Baric R S, Sobsey M D. Detection of low levels of enteric viruses in metropolitan and airplane sewage. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4401–4407. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.11.4401-4407.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shieh, Y.-S. C., S. S. Monroe, R. Fankhauser, G. Langlois, W. Burkhardt III, and R. S. Baric. Detection of Norwalk-like virus in shellfish implicated in illness. J. Infect. Dis., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Shieh Y-S C, Wait D, Tai L, Sobsey M D. Methods to remove inhibitors in sewage and other fecal wastes for enterovirus detection by the polymerase chain reaction. J Virol Methods. 1995;54:51–66. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(95)00025-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sobsey M D, Carrick R J, Jensen H R. Improved methods for detecting enteric viruses in oysters. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1978;36:121–128. doi: 10.1128/aem.36.1.121-128.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sobsey M D, Wallis C, Melnick J L. Development of a simple method for concentrating enteroviruses from oysters. Appl Microbiol. 1975;29:21–26. doi: 10.1128/am.29.1.21-26.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Straub T M, Pepper I L, Abbaszadegan M, Gerba C P. A method to detect enteroviruses in sewage sludge-amended soil using the PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:1014–1017. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.3.1014-1017.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Traore O, Arnal C, Mignotte B, Maul A, Laveran H, Billaudel S, Schwartzbrod L. Reverse transcriptase PCR detection of astrovirus, hepatitis A virus, and poliovirus in experimentally contaminated mussels: comparison of several extraction and concentration methods. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:3118–3122. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.8.3118-3122.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Interagency assessment of factors contributing to occurrence of recent viral outbreaks attributed to consumption of Gulf Coast oysters. Atlanta, Ga: Southeast Regional Office, U.S. Food and Drug Administration; 1998. [Google Scholar]