Abstract

Experimental evidence demonstrated that fluoro-edenite (FE) can develop chronic respiratory diseases and elicit carcinogenic effects. Environmental exposure to FE fibers is correlated with malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM). An early diagnosis of MPM, and a comprehensive health monitoring of the patients exposed to FE fibers are two clinical issues that may be solved by the identification of specific biomarkers. We reported the microRNA (miRNA) and transfer RNA-derived non coding RNA (tRNA-derived ncRNA) transcriptome in human normal mesothelial and malignant mesothelioma cell lines exposed or not exposed to several concentration FE fibers. Furthermore, an interactive mesothelioma-based network was derived by using NetME tool. In untreated condition, the expression of miRNAs and tRNA-derived ncRNAs in tumor cells was significantly different with respect to non-tumor samples. Moreover, interesting and significant changes were found after the exposure of both cells lines to FE fibers. The network-based pathway analysis showed several signaling and metabolic pathways potentially involved in the pathogenesis of MPM. From papers analyzed by NetME, it is clear that many miRNAs can positively or negatively influence various pathways involved in MPM. For the first time, the analysis of tRNA-derived ncRNAs molecules in the context of mesothelioma has been made by using in vitro systems. Further studies will be designed to test and validate their diagnostic potential in high-risk individuals' liquid biopsies.

Subject terms: Cancer, Computational biology and bioinformatics, Biomarkers, Health occupations

Introduction

Malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) is an aggressive and rare malignant neoplasm of the pleural surface, predominantly caused by asbestos fibers exposure1. A high incidence of MPM due to asbestos exposure has been reported by several international studies conducted in Finland2, California, USA3, China4, Corsica5, New Caledonia6, Cyprus7, and Greece8. Literature also shows a high incidence of this malignancy caused by asbestiform fibers exposure9. Fluoro-edenite (FE) fibers fall into this category, along with erionite, antigorite, winchite, magnesio‑riebeckite, richterite, and Libby asbestos9. FE is a silicate mineral, an amphibole found in 1997 in Biancavilla, a small town of the Etnean volcanic complex (Sicily, Italy)10. This mineral presents some characteristics similar to the asbestos group11 and scientific evidence led to the classification of FE as Group 1 human carcinogens12.

Epidemiological studies have indeed confirmed that FE fibers have shown similar effects to those already reported after exposure to asbestos fibers13–17, leading to chronic inflammation, DNA damage, and carcinogenesis.

Thus, environmental exposure to these carcinogen fibers continues to represent a public health problem due to the long latency of MPM and to its aggression not alerted by specific symptoms. Certainly, the prevention of diseases related to carcinogen fibers exposure is to reduce their presence in the environment through reclamation, encapsulation, and confinement9. However, having available biomarkers that give information on the health state of the patients exposed to FE fibers or that allow an early diagnosis on MPM patients still asymptomatic would be a tremendous goal. Some studies have been conducted deep into the link between common genetic variations in the molecular pathways, and cancer risk in order to find useful biomarkers for screening and early diagnosis of MPM in fibers-exposed subjects. Interestingly, literature has demonstrated that non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) may be used both as valuable non-invasive diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers and as therapeutic targets for cancer18,19.

As it is widely known, ncRNAs are a very heterogeneous class of RNA molecules that do not encode for proteins, and they represent a considerable amount of the transcriptome. More importantly, they are involved in several aspects of cell physiology by regulating a broad spectrum of cellular processes, from regulating gene expression to contributing to genome organization and stability20,21. ncRNAs are usually classified according to their size in small ncRNAs (< 200 nucleotides) and long ncRNAs (> 200 nucleotides)20,21. Alternatively, they can also be classified according to their function in housekeeping and regulatory ncRNAs20,21. The latter includes several classes of small RNA molecules in which microRNAs (miRNAs) and the new emergent transfer RNA-derived non-coding RNAs (tRNA-derived ncRNAs) represent very interesting components20,21.

Concerning miRNAs, they are long 18–25 nucleotide (nt) single-stranded RNAs, evolutionarily conserved, which negatively modulate the expression of their target messenger RNAs (mRNAs). They bind to the 3′ Untranslated Region (3′ UTR) of specific mRNA targets, leading to translational repression, or mRNA cleavage21. miRNAs are very important molecules in the regulation of gene expression at the post-transcriptional level, indeed, a single miRNA can control the expression of several mRNAs and a single mRNA may be targeted by more than one miRNA, thus creating a complex network of cooperative regulation21. Since the discovery of miR-15\16 deletion in Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients in 200222, many studies have been published about miRNAs and their involvement in the pathogenesis of several human cancers23. In addition, many efforts have been made to use miRNAs present in biological fluids as non-invasive diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for several human cancers24. Unfortunately, despite the extensive work, very few miRNAs might be used today in clinical practice24.

Contrary to miRNAs, tRNA-derived ncRNAs are a very heterogeneous class of ncRNAs that derive from tRNA processing. Indeed, in the last few years, several kinds of tRNA-derived ncRNAs have been discovered. However, a unique classification is still missing. A common grouping of such molecules is based on the location they originate from within the tRNA gene. Therefore, tRNA-derived ncRNAs can be divided into two main classes: (i) tRNA-derived small RNAs (tsRNAs), which derive from pre-tRNA; (ii) and tRNA-derived fragments (tRFs), which derive from mature tRNA25. tsRNAs are produced inside the nucleus and result from the cleavage of the pre-tRNAs 3’ trailer sequence by ribonucleases Z (RNases Z). They usually begin after the 3’-end of mature tRNAs and are characterized by a polyuracil sequence at their 3’-ends25. On the other hand, tRFs, ranging from 14–30 nt in length, are derived from mature tRNA26–28. Precisely, tRF-5 s are generated in the cytoplasm by Dicer-mediated cleavage of the mature tRNA D-loop29,30 while tRF-3 s are produced in the cytoplasm via cleavage of the T-loop in mature tRNAs operated by Dicer, angiogenin, and other members of the ribonuclease A (RNase A) superfamily. They are fragments originating from mature tRNA 3’-ends and include the final CCA sequence28,29,31. All these tRNA-derived ncRNA classes have been recently identified to have a major role in cancer biology. Indeed, it has been shown that tRNA-derived ncRNAs are not mere byproducts of random tRNA cleavage, rather they may actively play roles in several biological phenomena such as ribosome biogenesis, retrotransposition, virus infections, apoptosis, and cancer pathogenesis25,32–40. Furthermore, some classes of tRNA-derived ncRNAs have been shown to bind argonaute (AGO) and PIWI proteins, potentially acting as post- or pre-transcriptional regulators of gene expression37,41. Accumulating evidence also suggests the presence of functional tRNA-derived ncRNAs in human biological fluids, such as urine and serum from cancer patients26,42–45. However, such molecules have never been analyzed in the context of mesothelioma.

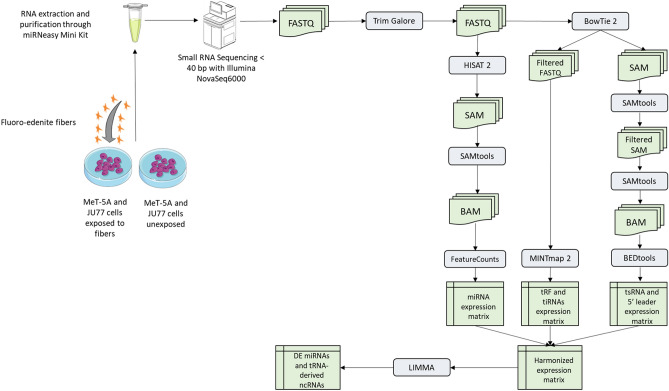

As mentioned above, in this study, we reported for the first time a small RNA-Seq transcriptome profiling of healthy mesothelial and malignant mesothelioma cell lines exposed to FE fibers. Precisely, we analyzed the miRNA and tRNA-derived ncRNA transcriptome in a human normal mesothelial cell line (MeT-5A) and in a human malignant mesothelioma cell line (JU77). Both these cell lines have been processed with and without fluoro-edenite fibers exposure, as reported in the experimental workflow (Fig. 1). All cell lines characteristics and the functional in vitro experiments were shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Experimental workflow used to extract, process, and analyze RNA from cell lines.

Table 1.

Characteristics of cell lines and functional in vitro experiments.

| Cell line | Species | Origin | Morphology | Treatment | Exposure time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MeT-5A | Homo sapiens | Healthy mesothelium | Epithelial-like | / | / |

| MeT-5A | Homo sapiens | Healthy mesothelium | Epithelial-like | 10 µg/ml fluoro-edenite fibers | 48 h |

| MeT-5A | Homo sapiens | Healthy mesothelium | Epithelial-like | 50 µg/ml fluoro-edenite fibers | 48 h |

| JU77 | Homo sapiens | Malignant mesothelioma | Epithelial-like | / | / |

| JU77 | Homo sapiens | Malignant mesothelioma | Epithelial-like | 10 µg/ml fluoro-edenite fibers | 48 h |

| JU77 | Homo sapiens | Malignant mesothelioma | Epithelial-like | 50 µg/ml fluoro-edenite fibers | 48 h |

Furthermore, in this study, a mesothelioma-based knowledge graph has been derived from PubMed central46 full texts (17,762 full texts) by using NetME tool47. The utility of this graph is to allow scientists, biologists, and researchers to find or learn logical relationships/interactions between MPM and other biological and chemical entities (such as miRNAs, diseases, xenobiotics, etc.) without the need to download and read mesothelioma-based articles available in the literature. The knowledge graph is released in a csv format and could be loaded in Neo4j48 or Cytoscape49 to be queried.

Results

Differential expression analysis

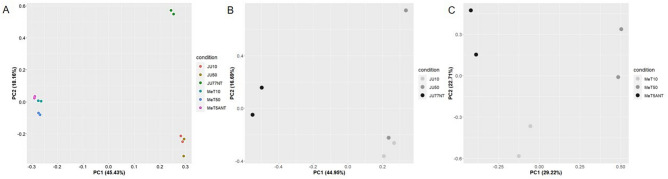

In order to identify dysregulation in miRNAs and tRNA-derived ncRNAs induced by FE fibers, we performed an RNA-Seq transcriptome profiling of unexposed and exposed normal mesothelial (MeT-5A) and malignant mesothelioma (JU77) cell lines. Differential expression analysis of such data showed major differences in small ncRNAs expression. Specifically, differences were observed when we compared MeT-5A and JU77 unexposed vs. FE-exposed at the same concentration. The Principal Component Analysis (PCA) showed a separation between MeT-5A and JU77 cell lines in their miRNAs and tRNA-derived ncRNAs expression. The greater separation was observed between the two different cell lines (PC1: 45.43%) while treated and untreated cell lines showed minor differences (PC2: 18.16%) (Fig. 2A). Moreover, to better highlight intra-cell line differences in small ncRNA expression, we performed PCAs specifically for each cell line (Figs. 2B, C). These confirmed a great separation between treated and untreated JU77 (PC1: 44.95%) (Fig. 2B). As about MeT-5A cells, the separation was greater by comparing untreated cells with that one exposed to 50 µg/ul of FE fibers (PC1: 29.22%) (Fig. 2C). In combination, these results seem to suggest that although differences in small ncRNA expression between treated and untreated MeT-5A were detected, major effects were observed in the JU77 cell line.

Figure 2.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) showing a separation in miRNAs and tRNA-derived ncRNAs between: (A) JU77 (human malignant mesothelioma) vs. MeT-5A (human normal mesothelium) cell lines; (B) JU77 controls vs. exposed to 10 and 50 ug/ml FE fibers; (C) MeT-5A controls vs. exposed to 10 and 50 ug/ml FE fibers.

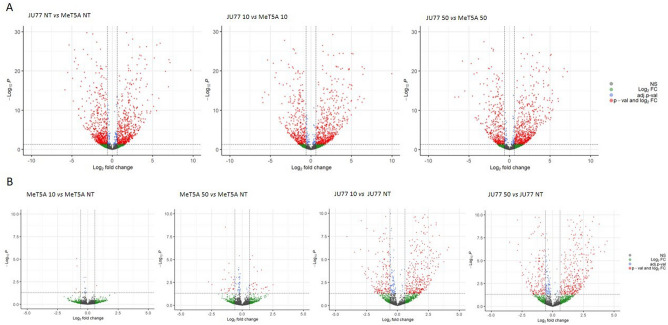

The differentially expressed miRNAs and tRNA-derived ncRNAs were: 1171 in untreated JU77 vs. MeT-5A, 960 in JU77 vs. MeT-5A exposed to 10 ug/ml FE fibers, and 969 in JU77 vs. MeT-5A exposed to 50 ug/ml FE fibers (Fig. 3A). The common population of differentially expressed miRNAs and tRNA-derived ncRNAs between the two cell lines increased with the exposure to FE fibers.

Figure 3.

Volcano plots showing the differentially expressed miRNAs and tRNA-derived ncRNAs between: (A) JU77 (human malignant mesothelioma) vs. MeT-5A (human normal mesothelium); (B) Untreated vs. FE fibers treated JU77 and MeT-5A.

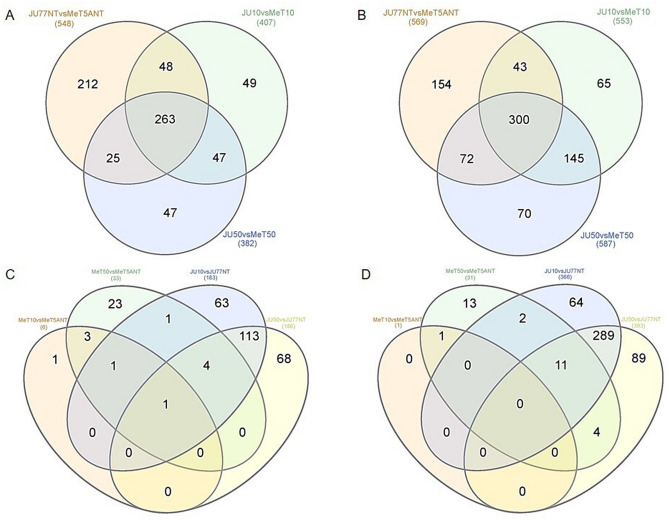

In more detail, the down-regulated miRNAs and tRNA-derived ncRNAs were: 548 in untreated JU77 vs. MeT-5A, 407 in JU77 vs. MeT-5A exposed to 10 ug/ml FE fibers, and 382 in JU77 vs. MeT-5A exposed to 50 ug/ml FE fibers (Fig. 4A). Among all samples, the differentially expressed miRNAs and tRNA-derived ncRNAs in common were 263 (Fig. 4A). Among these, 48 were in common between the JU77 and MeT-5A untreated and exposed to 10 ug/ml FE fibers (40 tRNA-derived ncRNAs and 8 miRNAs), 25 were in common between the JU77 and MeT-5A untreated and exposed to 50 ug/ml FE fibers (22 tRNA-derived ncRNAs and 3 miRNAs), and 47 were in common between the JU77 and MeT-5A exposed to 10 and 50 ug/ml FE fibers (30 tRNA-derived ncRNAs and 17 miRNAs) (Fig. 4A, Table 2).

Figure 4.

Venn diagrams showing down-regulated miRNAs and tRNA-derived ncRNAs distribution between: (A) JU77 vs. MeT-5A cell lines both not exposed and exposed to FE fibers; (C) The same cellular line both not exposed and exposed to FE fibers. Venn diagrams showing up-regulated miRNAs and tRNA-derived ncRNAs distribution between: (B) JU77 vs. MeT-5A cell lines both not exposed and exposed to FE fibers; (D) The same cellular line both not exposed and exposed to FE fibers.

Table 2.

Down-regulated ncRNAs in common among JU77 (human malignant mesothelioma) vs. MeT-5A (human normal mesothelium) controls and JU77 vs. exposed to 10 and 50 ug/ml FE fibers; down-regulated ncRNAs in common among JU77 vs. MeT-5A exposed to 10 and exposed to 50 ug/ml FE fibers.

| Down-regulated ncRNAs in common | ||

|---|---|---|

| JU77NTvs.MeT5ANT and JU10vs.MeT10 | JU77NTvsMeT5ANT and JU50vsMeT50 | JU10vsMeT10 and JU50vsMeT50 |

| tRF-43-ZMB3UEVPQOH7HLWXD2 | tRF-26-VJUE3QHMY1B | tRF-18-8R6Q46D2 |

| tRF-34-XRK4WO2F9IY9E2 | tRF-26-MJ8F81KLB5D | ts-52 |

| tRF-27-5BF900BY4D5 | tRF-30-M2OSRNLNKSEK | tRF-18-H5KQBFD2 |

| tRF-33-XRK4WO2F9IY9V | tRF-27-HK4B8XVQN52 | tRF-17-08Q2B52 |

| 5P_tRNA-His-GTG-1–1 | tRF-23-QOH7HLWXD2 | tRF-19-J9BBF3E2 |

| tRF-17-9N1EWJM | tRF-40-ZSE6YBY4HEJQY1B6 | tRF-35-4S14IZJQXEXOIS |

| tRF-31-QKF1R3WE8RO80 | tRF-17-73V2Y8K | tRF-28-4S14IZJQXE0M |

| tRF-35-I1KQSX0DIJZ726 | tRF-21-941QKS3WD | tRF-22-WB86N7O52 |

| tRF-28-PS5P4PW3FJDD | tRF-20-9DH48V7K | tRF-29-4S14IZJQXEJU |

| tRF-39-H2SBUL6JYBKRYNJO | tRF-16-XXW27ZE | tRF-22-WEKSPM852 |

| tRF-17-BS68BFJ | tRF-41-SO1XDXVJUE3QHMY1B | tRF-23-Z5EFOK8YDZ |

| tRF-19-V47P59I8 | tRF-48-9NZ6V6Z3M8ZLSSXUOLD2 | tRF-19-1SS2PMER |

| tRF-33-M2OSRNLNKSEKDS | tRF-19-DRVQHZE2 | tRF-32-3JVIJMRPFQ5D5 |

| tRF-34-QKF1R3WE8RO8IS | 5P_tRNA-Val-AAC-2–1 | tRF-31-YSV4V4SQ2WW1E |

| tRF-30-FN8DYDZDL9X1 | tRF-18-J6K6UDV | tRF-22-8EKSP1852 |

| tRF-35-1WZ4RZDMKNR7F6 | tRF-19-Y87HFKJJ | tRF-22-8B8SOUPR2 |

| tRF-36-D4ZWRNU3KQ9MV1B | tRF-18-H7HLWXD2 | tRF-20-L3KQNKWH |

| tRF-36-9LVPZO0BEBXNWDE | tRF-24-ROWFUBNO0W | tRF-17-73V6M7M |

| tRF-18-VKS4I7D4 | tRF-17-2YU04DQ | tRF-22-WB8647O52 |

| tRF-31-Y2MJ8F81KLB5D | tRF-28-PLBIUBNXJMX | tRF-31-WZVLUE15MXE9D |

| tRF-37-U37Y93Y086Z34J2 | tRF-16-S8V0J80 | tRF-18-I6BB5LD2 |

| tRF-29-32VIJMRPFQFX | tRF-18-9LVPZOU | tRF-26-32VIJMRPFQD |

| tRF-24-FSXMSL732Z | tRF-24-L3KZM8WM2Q | |

| tRF-20-Q622EVUI | hsa-miR-4645-3p | tRF-19-9DH48V24 |

| tRF-20-S8V0J8O9 | hsa-miR-33a-3p | tRF-20-BLS17ONR |

| tRF-17-KE6KM8N | hsa-miR-2355-5p | tRF-18-18VUY9DW |

| tRF-20-NB8PLML3 | tRF-30-7RH3S3RX8HWV | |

| tRF-45-EZ5P1OHE10NO0RNQYX | tRF-22-WB0Q37Q52 | |

| tRF-22-W087W4SV2 | tRF-20-L3KZM8WM | |

| tRF-37-7O58J0K8UMPLBIO | tRF-27-LEK5YY0FYWQ | |

| tRF-45-BF82Z4D7OOJ0QXL13X | ||

| tRF-27-INVDRI2Q2R2 | hsa-miR-22-3p | |

| tRF-17-8R6Q46J | hsa-miR-140-3p | |

| tRF-37-9LVPZO0BEBXNWD5 | hsa-miR-381-3p | |

| tRF-16-3KJBP1B | hsa-miR-132-5p | |

| tRF-23-86V8WPMNY | hsa-miR-3176 | |

| tRF-22-WKXU53K8N | hsa-miR-323a-3p | |

| tRF-16-4P64R90 | hsa-miR-296-5p | |

| tRF-25-V4V4SQ2WW1 | hsa-let-7 g-3p | |

| tRF-41-U5YKFN8DYDZDL9X1B | hsa-miR-19b-3p_1 | |

| hsa-miR-32-3p | ||

| hsa-miR-1248 | hsa-miR-378a-5p | |

| hsa-miR-26a-5p_1 | hsa-miR-15a-3p | |

| hsa-miR-324-5p | hsa-miR-548 k | |

| hsa-miR-1301-3p | hsa-miR-7974 | |

| hsa-miR-664a-3p | hsa-miR-671-3p | |

| hsa-miR-641 | hsa-miR-561-3p | |

| hsa-miR-3651 | hsa-miR-7-5p_1 | |

| hsa-miR-627-3p | ||

As for the up-regulated miRNAs and tRNA-derived ncRNAs, these were: 569 in untreated JU77 vs. MeT-5A, 553 in JU77 vs. MeT-5A exposed to 10 ug/ml FE fibers, and 587 in JU77 vs. MeT-5A exposed to 50 ug/ml FE fibers (Fig. 4B). Among all samples, the differentially expressed miRNAs and tRNA-derived ncRNAs in common were 300 (Fig. 4B). Among these, 43 were in common between the JU77 and MeT-5A untreated and exposed to 10 ug/ml FE fibers (37 tRNA-derived ncRNAs and 6 miRNAs), 72 were in common between the JU77 and MeT-5A untreated and exposed to 50 ug/ml FE fibers (54 tRNA-derived ncRNAs and 18 miRNAs), and 145 were in common between the JU77 and MeT-5A exposed to 10 and 50 ug/ml FE fibers (143 tRNA-derived ncRNAs and 2 miRNAs) (Fig. 4B, Table 3).

Table 3.

Up-regulated ncRNAs in common among JU77 (human malignant mesothelioma) vs. MeT-5A (human normal mesothelium) controls and JU77 vs. exposed to 10 and 50 ug/ml FE fibers; down-regulated ncRNAs in common among JU77 vs. MeT-5A exposed to 10 and exposed to 50 ug/ml FE fibers.

| Up-regulated ncRNAs in common | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JU77NTvsMeT5ANT and JU10vsMeT10 | JU77NTvsMeT5ANT and JU50vsMeT50 | JU10vsMeT10 and JU50vsMeT50 | |||

| ts-9 | tRF-33-79MP9P9MH57SD3 | hsa-miR-4521 | tRF-17-8WQ0D52 | tRF-37-LP21W3WB8US5652 | tRF-19-1R7HFEE2 |

| ts-7 | tRF-33-PSQP4PW3FJIKW | hsa-miR-92a-3p_1 | tRF-16-KQ3SW1B | tRF-26-63U0EZY9X1B | tRF-30-JMRPFQ5DWXH9 |

| tRF-19-LNKSEKHY | tRF-40-70K8HJ83ML5F82NZ | hsa-miR-532-5p | tRF-19-N2NYDRE8 | tRF-26-MI7O3B1NR8E | tRF-20-K87SIRM1 |

| tRF-32-5BVNUEVBWXQZ4 | tRF-32-MIF91SS2P46I3 | hsa-miR-429 | tRF-41-8OYDVNZDBQ8BB2S1B | tRF-34-I8W47W1R7HFEE2 | tRF-21-987X1RJY0 |

| tRF-16-ML5HMVE | tRF-33-MIF91SS2P4FIDQ | hsa-miR-485-3p | tRF-31-R008R959KUMKB | tRF-34-34HWH3RXSINHKN | tRF-36-L85DMKYUYRLHR0D |

| tRF-16-ML5F82D | ts-17 | hsa-miR-30c-2-3p | tRF-33-PS5P4PW3FJHPW | tRF-17-WS72092 | tRF-19-PS5P4PJ4 |

| tRF-18-I8W47WZ | tRF-20-L3K5J0WB | hsa-miR-493-3p | tRF-42-Y6IO43ZU2FYOB0152 | tRF-25-5NB2NZW7O6 | tRF-35-EO7N987X1RJYSX |

| ts-11 | tRF-31-5BVNUEVBWXQZ0 | hsa-miR-29b-2-5p | tRF-33-Z3M8ZLSSXUOLD2 | tRF-32-7EMQ18Y3E7QNN | tRF-20-Y8NNBSBK |

| tRF-22-WE8SP6X52 | tRF-33-3JVIJMRPFQRD03 | hsa-miR-190b | tRF-42-YDU37Y93Y086Z34J2 | tRF-30-623K7SIR3DR2 | tRF-33-RRJ89O9NF5W8W |

| tRF-26-9NS334L2H1B | tRF-18-W3FJHPW | hsa-miR-502-3p | tRF-17-8SPOL52 | tRF-40-2VR0PSR9593J2426 | tRF-26-M0IBB7Z92KB |

| tRF-25-6IZB8PLML3 | tRF-20-LIK898OH | hsa-miR-532-3p | tRF-30-945NB2NZW7O6 | tRF-17-8S68L52 | tRF-39-86J8WPMN1E8Y7ZFV |

| tRF-16-RPM830E | tRF-39-70K8HJ83ML5F82HQ | hsa-miR-500a-3p | tRF-17-KSP1852 | tRF-31-PW5SVP9N15WV0 | tRF-26-U3XOUZDZN1B |

| tRF-31-3JVIJMRPFQRDE | tRF-30-MIF91SS2P4FI | hsa-miR-409-5p | tRF-20-KS7SB1RH | tRF-19-Z3M8ZL2J | tRF-43-Z6V6Z3M8ZLSSXUOLD2 |

| tRF-22-LEKPMK3WP | tRF-36-PSQP4PW3FJI0E7E | hsa-miR-431-3p | tRF-43-Y6FPZD3KYUYR66EFD2 | tRF-17-WJ9X0UF | tRF-27-90YBOZZ7ND2 |

| tRF-25-LEKPV03X1N | tRF-22-45N2P4Z9Q | hsa-miR-660-3p | tRF-40-XENDBP1IUUK7VZ0R | tRF-20-4VZ87HFK | tRF-26-Q6S8V0J6OZE |

| tRF-19-FEWS3VF8 | tRF-20-PSQP4PW3 | hsa-miR-505-5p | tRF-41-XENDBP1IUUK7VZ0RB | tRF-18-YR66EFD2 | tRF-37-Y91293WEW6VM4J2 |

| tRF-30-MIF91SS2P46I | tRF-16-O0SRMND | hsa-miR-502-5p | tRF-23-ZOSRI8WPD2 | tRF-37-87R8WP9N1EWJQ72 | tRF-18-Y9PYKHD4 |

| tRF-24-739P8WQ0EB | tRF-21-U9XW983F0 | hsa-miR-2277-5p | tRF-17-8Y3HSV2 | ts-89 | tRF-24-7W1R7HFEE2 |

| tRF-28-F91SS2PMFI0Q | tRF-36-87R8WP9N1EWJQ7D | tRF-27-945NB2NZW7L | tRF-34-MUWLV47PU9XWK0 | tRF-21-XOUZDZN1B | |

| tRF-19-S998LOJX | tRF-33-MIF91SS2P46IDQ | tRF-18-Y8NNBS6 | tRF-29-34HWH3RXSIHM | tRF-26-727OFIZ9WUD | |

| tRF-33-2QR7F8YKIR9N05 | tRF-19-LE308HI1 | tRF-17-KS8WP92 | tRF-29-R9JP9P9NH523 | tRF-39-86V8WPMN1E8Y7ZFV | |

| tRF-16-XIW282B | tRF-29-2E489B3VI8KQ | tRF-35-PW5SVP9N15WV7W | tRF-26-08R959KUMKB | tRF-18-Y9H33PD2 | |

| tRF-30-3JVIJMRPFQ5D | tRF-41-70K8HJ83ML5F82NZB | tRF-29-945NB2NZW7HV | tRF-39-XENDBP1IUUK7VZEJ | tRF-16-K8M0W1B | |

| tRF-22-3638FQ7Z3 | tRF-20-S3M8309N | tRF-26-R81XDDZZ4YB | tRF-25-3K7SIR3DR2 | tRF-37-L85DMKYUYRLHR0J | |

| tRF-18-XIW282X | tRF-32-9M739P8WQ0D52 | tRF-41-8HM2OSRNLNKSEK51B | tRF-32-PW5SVP9N15WVN | tRF-44-9XEO7N987X1RJYSXI2 | |

| tRF-32-6XQ6S8V0J8O9Q | tRF-38-EH623K7SIR3DR2DV | tRF-17-W18FLUF | tRF-16-WJ9X0UB | tRF-19-9N15WV2P | |

| tRF-16-739P8W0 | tRF-17-8R1546J | tRF-28-727OFIZ9WUD2 | tRF-38-YDU37Y93Y086Z3DO | tRF-24-VUUMHNU6E2 | |

| tRF-26-17JOWU1M70E | tRF-22-8190JWZ75 | tRF-34-PW5SVP9N15WV2P | tRF-16-8871K9D | tRF-18-SRI8WPD2 | |

| tRF-16-9NS334D | tRF-34-Y6V4VH7Q2WNIK1 | tRF-20-WVZ5EFOK | tRF-18-0RSSX7D2 | tRF-22-877343RX4 | |

| tRF-20-WJ9X0UD3 | tRF-21-LEKPV03XB | 5P_tRNA-His-GTG-1–8 | tRF-33-7EMQ18Y3E7QN00 | tRF-31-I363U0EZY9X1B | |

| tRF-32-6LQ6S8V0J6OZQ | tRF-35-PS5P4PW3FJHPEZ | tRF-21-MI7O3B1N0 | tRF-29-PSQP4PW3FJF4 | tRF-20-7KZOSRI8 | |

| tRF-17-HO53KYN | tRF-34-Y6V4V47Q2WNIK1 | tRF-36-M2OSRNLNKSEK51B | tRF-23-WJ9X0UD304 | tRF-17-YR66EFJ | |

| tRF-19-LNKSEKH9 | tRF-36-Q99P9P9NH57S36D | tRF-35-EH623K7SIR3DR2 | tRF-36-EO7N987X1RJYSX0 | tRF-32-R9JP9P9NH5SY3 | |

| tRF-19-LJK1JKE4 | tRF-30-R9JP9P9NH5SY | tRF-29-R81XDDZZ4YE2 | tRF-36-XSXMSL73VL4YMYE | tRF-16-PSQP4PE | |

| tRF-22-9M739P8WM | tRF-34-PSQP4PW3FJI0E5 | tRF-40-KEUI1ZXF0N2BD0U6 | tRF-17-W6VM4J2 | tRF-37-PSQP4PW3FJIKE7O | |

| tRF-17-7M3PVIK | tRF-20-LNK88KO4 | tRF-42-YQHQ9M739P8WQ0D52 | tRF-18-MI7O3BY | ||

| tRF-18-QQKNR70H | tRF-17-OB9ZFH4 | tRF-43-7O409Z7KZOSRI8WPD2 | tRF-38-V6Z3M8ZLSSXUOLD2 | hsa-miR-335-5p | |

| tRF-19-L61MQKKK | tRF-28-K8HJ83ML5F02 | tRF-16-3VWIQ1B | hsa-miR-5586-5p | ||

| hsa-miR-376b-3p | tRF-16-YPSV17D | tRF-21-U0EZY9X1B | tRF-20-K87SERM4 | ||

| hsa-miR-188-5p | tRF-28-LE3V8FQMEP0Q | 5P_tRNA-His-GTG-1–7 | tRF-21-RNLNK88K0 | ||

| hsa-miR-410-3p | tRF-21-NRDF7UK80 | tRF-28-R81XDDZZ4YV | tRF-17-RPM830K | ||

| hsa-miR-29b-3p_1 | tRF-25-8Q9KZR3HJ3 | tRF-16-3VLIE1B | tRF-16-Q01LQKB | ||

| hsa-miR-449a | tRF-34-KSLP7SDRXSE5I2 | tRF-26-IQ5O8LZ521B | tRF-17-9NS334K | ||

| hsa-miR-548u | tRF-35-JYSWRYVMMV5BU6 | tRF-24-1XDDZZ4YE2 | tRF-25-M0IBB7Z92K | ||

| tRF-40-OB9ZFH690M0RHB26 | tRF-27-727OFIZ9WUJ | tRF-26-Z3M8ZLSSXU0 | |||

| tRF-17-RN8RQF4 | tRF-16-362VO00 | tRF-20-387SDRJH | |||

| tRF-37-P4R8YP9LON4VN11 | tRF-20-48Z8SSFK | tRF-20-J0DPZOIP | |||

| tRF-29-W47W1R7HFEE2 | tRF-42-8OP3X1M3WE8SPOL52 | tRF-39-9Q53K87SHRMF3RE2 | |||

| tRF-25-SP58309MUK | tRF-27-93Y086Z34J2 | tRF-18-XEKJ5RDS | |||

| 5P_tRNA-Pro-AGG-2–1 | tRF-17-86Z34J2 | tRF-19-URYRSIE2 | |||

| tRF-19-WJ9X0U0Y | tRF-23-1XDDZZ4YV | tRF-39-XU53F85SI1LQ3RE2 | |||

| tRF-32-897PVP9N1QKSJ | tRF-33-PW5SVP9N15WV0E | tRF-38-WD8NBNIED6VZ0OD2 | |||

| tRF-28-Z8XO46DODLD2 | tRF-26-8DYDZDL9X1B | tRF-21-OB9ZFH69B | |||

| tRF-37-Q99P9P9NH57S362 | tRF-34-M2OSRNLNKSEKH9 | tRF-39-PSQP4PW3FJIKE727 | |||

When we compared miRNAs and tRNA-derived ncRNAs expression between unexposed vs. exposed MeT-5A the results showed several differentially expressed molecules. In particular, miRNAs and tRNA-derived ncRNAs differentially expressed in MeT-5A untreated vs. exposed to 10 and 50 ug/ml FE fibers were 7 and 64, respectively (Fig. 3B). Indeed, the miRNAs and tRNA-derived ncRNAs differentially expressed in MeT-5A increased in dose-dependent manner with the exposure to FE fibers. On the other hand, the comparison between untreated vs. FE-treated JU77 showed a substantial difference between the differentially expressed miRNAs and tRNA-derived ncRNAs. In particular, miRNAs and tRNA-derived ncRNAs differentially expressed in JU77 unexposed vs. exposed to 10 and 50 ug/ml FE fibers were 549 and 579, respectively (Fig. 3B).

In more detail, the down-regulated miRNAs and tRNA-derived ncRNAs were: 6 and 33 in untreated MeT-5A vs. exposed to 10 and 50 ug/ml FE fibers, respectively (Fig. 4C). While in the case of neoplastic cells, the down-regulated miRNAs and tRNA-derived ncRNAs were: 183 and 186 in untreated JU77 vs. exposed to 10 and 50 ug/ml FE fibers, respectively (Fig. 4C). Among these, 3 were in common between the MeT-5A untreated and exposed to 10 ug/ml FE fibers vs. MeT-5A untreated and exposed to 50 ug/ml FE fibers (tRF-42-YDU37Y93Y086Z34J2, tRF-40-XENDBP1IUUK7VZ0R, and tRF-41-XENDBP1IUUK7VZ0RB), 113 were in common between the JU77 untreated and exposed to 10 ug/ml FE fibers vs. JU77 untreated and exposed to 50 ug/ml FE fibers (87 tRNA-derived ncRNAs and 26 miRNAs), only hsa-miR-3618 was in common between the MeT-5A untreated and exposed to 50 ug/ml FE fibers vs. JU77 untreated and exposed to 10 ug/ml FE fibers, no compound was in common between the MeT-5A untreated and exposed to 50 ug/ml FE fibers vs. JU77 untreated and exposed to 50 ug/ml FE fibers (Fig. 4C, Table 4). If we compare MeT-5A exposed to 10 ug/ml FE fibers vs. MeT5A untreated and MeT-5A exposed to 50 ug/ml FE fibers vs. MeT5A untreated and JU77 exposed to 10 ug/ml FE fibers vs. JU77 untreated the only compound in common was hsa-miR-1248 (Fig. 4C, Table 4). tRF-40-8B7OIQ1IBM4LV7U6, tRF-31-79MP9P9MH57SD, tRF-32-P4R8YP9LON4V3, tRF-25-SP58309MUK were the down-regulated tRNA-derived ncRNAs in common among MeT-5A exposed to 50 ug/ml FE fibers vs. MeT5A untreated and JU77 exposed to 10 ug/ml FE fibers vs. JU77 untreated and JU77 exposed to 50 ug/ml FE fibers vs. JU77 untreated (Fig. 4C, Table 4). Among all samples, tRF-33-79MP9P9MH57SD3 was the only down-regulated compound in common (Fig. 4C, Table 4).

Table 4.

Down-regulated ncRNAs in common among JU77 (human malignant mesothelioma) vs. MeT-5A (human normal mesothelium) in all tested conditions.

| Down-regulated ncRNAs in common | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| MeT10vMeT5ANT and MeT50vs.MeT5ANT | JU10vs.JU77NT and JU50vs.JU77NT | ||

| tRF-42-YDU37Y93Y086Z34J2 | tRF-33-Q99P9P9NH57SD3 | ts-7 | tRF-35-86J8WPMN1E8Y7Z |

| tRF-40-XENDBP1IUUK7VZ0R | tRF-16-RPM830D | tRF-20-L3KQNKWH | tRF-22-WEK6S1852 |

| tRF-41-XENDBP1IUUK7VZ0RB | ts-49 | tRF-22-WE8SPOL52 | tRF-16-R29P4PE |

| tRF-34-Q99P9P9NH57S15 | tRF-31-WZVLUE15MXE9D | tRF-19-1SS2PMER | |

| MeT10vs.MeT5ANT and MeT50vs.MeT5ANT and JU10vs.JUNT | ts-111 | tRF-17-W3FJHP1 | tRF-31-YSV4V4SQ2WW1E |

| hsa-miR-1248 | ts-52 | tRF-20-L3KZM8WM | tRF-34-4WVLV470VR31KD |

| tRF-35-LSM1M3WE8SSP6D | 5P_tRNA-His-GTG-1–5 | tRF-21-45N2P4Z9E | |

| MeT10vs.MeT5ANT and MeT50vs.MeT5aNT and JU10vs.JU77NT and JU50vs.JU77NT | tRF-20-9P8WQ0D5 | tRF-27-86J8WPMN1E5 | tRF-20-LMK1JKE2 |

| tRF-33-79MP9P9MH57SD3 | ts-70 | tRF-40-I6D3987SDR265M5Z | tRF-22-8FLUD3KSN |

| tRF-22-9P8WQ0D52 | 5P_tRNA-Gln-TTG-3–3 | ts-51 | |

| MeT50vs.MeT5ANT and JU10vs.JUNT | tRF-34-P4R8YP9LON4VHM | tRF-33-U4727OFIZ9WUD2 | tRF-22-WEKSPM852 |

| hsa-miR-3618 | tRF-32-3JVIJMRPFQ5D5 | tRF-34-K84J83ML5F92H3 | |

| ts-34 | tRF-22-79MP9PMNI | hsa-let-7 g-3p | |

| MeT50vsMeT5ANT and JU50vsJU77NT | tRF-22-1SS2PMFIQ | tRF-22-8EKSP1852 | hsa-miR-200b-3p |

| - | tRF-33-79MP9PMNH5ISD3 | tRF-22-WE8SPOX52 | hsa-let-7c-3p |

| tRF-19-S334L2F1 | tRF-36-PSQP4PW3FJI0E7E | hsa-miR-7974 | |

| MeT50vsMeT5ANT and JU10vsJU77NT and JU50vsJU77NT | tRF-16-S3M830E | tRF-18-I8W47WZ | hsa-miR-100-3p |

| tRF-40-8B7OIQ1IBM4LV7U6 | tRF-37-HQ9M739P8WQ0D52 | tRF-18-I6BB5LD2 | hsa-miR-503-5p |

| tRF-31-79MP9P9MH57SD | ts-98 | tRF-23-JMRPFQJD0Q | hsa-miR-222-5p |

| tRF-32-P4R8YP9LON4V3 | tRF-19-J9BBF3E2 | tRF-20-H1NRM5U6 | hsa-miR-484 |

| tRF-25-SP58309MUK | ts-101 | tRF-22-WE8SP6X52 | hsa-miR-363-3p |

| tRF-32-3JVIJMRPFQRD5 | ts-112 | hsa-miR-4521 | |

| ts-96 | tRF-32-5BVNUEVBWXQZ4 | hsa-miR-29a-5p | |

| ts-20 | tRF-16-ML5F82D | hsa-miR-18a-5p | |

| ts-2 | tRF-31-MIF91SS2P46ID | hsa-miR-29b-1-5p | |

| tRF-40-70K8HJ83ML5F82NZ | tRF-31-3JVIJMRPFQ5DE | hsa-miR-18a-3p | |

| tRF-34-79MP9PMNH5IS15 | tRF-16-I6D3880 | hsa-miR-503-3p | |

| tRF-33-3JVIJMRPFQRD03 | ts-95 | hsa-miR-362-5p | |

| tRF-33-87R8WP9N1EWJDW | tRF-33-3JVIJMRPFQ5D03 | hsa-miR-20a-3p | |

| ts-23 | tRF-31-5BVNUEVBWXQZ0 | hsa-let-7a-2-3p | |

| tRF-16-PJ5830E | tRF-42-D3IPBBKN8LEZSO1XF | hsa-miR-200a-3p | |

| tRF-28-4S14IZJQXE0M | tRF-22-WB86N7O52 | hsa-miR-132-5p | |

| tRF-29-4S14IZJQXEJU | tRF-18-INVDRID1 | hsa-miR-32-3p | |

| tRF-18-YDVNZDR | tRF-17-H7V3LYN | hsa-miR-125b-2-3p | |

| tRF-21-9P8WQ0D5D | tRF-35-86V8WPMN1E8Y7Z | hsa-miR-16–1-3p | |

| tRF-18-H5KQBFD2 | tRF-20-W3FJHPEZ | hsa-miR-19b-1-5p | |

| tRF-33-PSQP4PW3FJIKW | tRF-32-MIF91SS2P46I3 | hsa-miR-429 | |

| ts-68 | tRF-18-W3FJHPW | hsa-miR-548 k | |

As for the up-regulated miRNAs and tRNA-derived ncRNAs, these were: 1 and 31 in untreated MeT-5A vs. exposed to 10 and 50 ug/ml FE fibers, respectively (Fig. 4D). While in the case of neoplastic cells, the up-regulated miRNAs and tRNA-derived ncRNAs were: 366 and 393 in untreated JU77 vs. exposed to 10 and 50 ug/ml FE fibers, respectively (Fig. 4D). Among these, only ts-96 was in common between the MeT-5A untreated and exposed to 10 ug/ml FE fibers vs. MeT-5A untreated and exposed to 50 ug/ml FE fibers, 289 were in common between the JU77 untreated and exposed to 10 ug/ml FE fibers vs. JU77 untreated and exposed to 50 ug/ml FE fibers (among these only one was a miRNA, specifically hsa-miR-615-3p) (Fig. 4D, Table 5). tRF-16-PSSELQB, and tRF-21-JYSWRYVMD.

Table 5.

Up-regulated ncRNAs in common among JU77 (human malignant mesothelioma) vs. MeT-5A (human normal mesothelium) in all tested conditions.

| Up-regulated ncRNAs in common | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MeT10vMeT5ANT and MeT50vs.MeT5ANT | JU10vs.JU77NT and JU50vs.JU77NT | |||

| ts-96 | tRF-17-8WQ0D52 | tRF-30-M2OSRNLNKSEK | tRF-34-MUWLV47PU9XWK0 | tRF-18-Y8NNBS6 |

| tRF-16-3JWB61B | tRF-22-YBOZZ7ND2 | tRF-36-L85DMKYUYRLHR0D | tRF-27-R81XDDZZ4Y1 | |

| MeT10vs.MeT5ANT and MeT50vs.MeT5ANT and JU10vs.JUNT | tRF-26-5BF900BY4DE | tRF-34-34HWH3RXSINHKN | tRF-42-8OP3X1M3WE8SPOL52 | tRF-17-8Y3HSV2 |

| - | tRF-32-897PVP941QKSJ | tRF-21-WSNSRV500 | tRF-39-XENDBP1IUUK7VZEJ | tRF-19-J6K6UDE2 |

| tRF-16-K8KDP1B | tRF-25-5BF900BY4D | tRF-35-1WZ4RZDMKNR7F6 | tRF-33-PS5P4PW3FJHPW | |

| MeT10vs.MeT5ANT and MeT50vs.MeT5aNT and JU10vs.JU77NT and JU50vs.JU77NT | tRF-32-M2OSRNLNKSEKL | tRF-39-EO7N987X1RJYSXI2 | tRF-26-JYSWRYVMMV0 | tRF-30-945NB2NZW7O6 |

| - | tRF-22-5BF900BY3 | tRF-31-PW5SVP9N15WV0 | tRF-22-WEW6VM4J2 | tRF-21-WSNYRV500 |

| tRF-17-884U1D2 | tRF-34-PW5SVP9N15WV2P | tRF-20-Y8NNBSBK | tRF-17-K6S1852 | |

| MeT50vs.MeT5ANT and JU10vs.JUNT | tRF-33-QKF1R3WE8RO8DX | tRF-18-Y9H33PD2 | tRF-35-E6YBY4HEJQY1B6 | tRF-23-ZOSRI8WPD2 |

| tRF-16-PSSELQB | tRF-16-KQ3SW1B | tRF-23-8RR9ODMJDX | tRF-26-M0IBB7Z92KB | tRF-27-93Y086Z34J2 |

| tRF-21-JYSWRYVMD | tRF-19-N2NYDRE8 | tRF-35-PW5SVP9N15WV7W | tRF-18-HSQSD2D2 | tRF-34-I8W47W1R7HFEE2 |

| tRF-16-L7P5QKB | tRF-38-V6Z3M8ZLSSXUOLD2 | tRF-35-7OIQ1IBM4LV7U6 | tRF-18-5BF900R | |

| MeT50vsMeT5ANT and JU50vsJU77NT | tRF-41-8OYDVNZDBQ8BB2S1B | tRF-27-5BF900BY4D5 | tRF-26-ROWFUBNOBZE | tRF-24-1XDDZZ4YE2 |

| tRF-18-WKXU53DJ | tRF-17-88481D2 | tRF-19-1R7HFEE2 | tRF-16-2KWHR90 | tRF-29-R81XDDZZ4YE2 |

| tRF-48-9NZ6V6Z3M8ZLSSXUOLD2 | tRF-33-86J8WPMN1E8Y0E | tRF-20-4VZ87HFK | tRF-46-7Z8L8NRS9NS334L2H1B | tRF-26-08R959KUMKB |

| tRF-19-OSM83OJX | tRF-16-884U1DD | tRF-32-QKF1R3WE8RO84 | tRF-29-PS5P4PW3FJF2 | tRF-17-KS8WP92 |

| tRF-22-7OFIZ9WUJ | tRF-16-8WQ0D5D | tRF-17-8871K92 | tRF-16-K8M0W1B | tRF-44-ZW20YBYL6XDRVQHZE2 |

| tRF-19-5BF9000W | tRF-19-Z3M8ZL2J | tRF-41-YDU37Y93Y086Z34JD | tRF-30-P4R8YP9LON4V | |

| MeT50vsMeT5ANT and JU10vsJU77NT and JU50vsJU77NT | tRF-32-86J8WPMN1E8YN | tRF-24-VUUMHNU6E2 | tRF-26-Z3V5393L41B | tRF-43-Y6FPZD3KYUYR66EFD2 |

| tRF-28-727OFIZ9WUD2 | tRF-28-945NB2NZW7DR | tRF-33-86V8WPMN1E8Y0E | tRF-27-MJ8F81KLB52 | tRF-25-5NB2NZW7O6 |

| tRF-18-51MLHVDB | tRF-16-K5J0W1B | tRF-22-4B8XVQN52 | tRF-33-9Z7KZOSRI8WPD2 | tRF-26-R81XDDZZ4YB |

| tRF-19-86J8WP1Z | tRF-17-K0SVRNK | tRF-31-VDRI2Q2RJO01B | tRF-17-941QKSJ | tRF-16-34L2H1B |

| tRF-18-7X9PN5D5 | tRF-31-R008R959KUMKB | tRF-21-5BF900BYD | tRF-35-I1KQSX0DIJZ726 | tRF-26-VJUE3QHMY1B |

| tRF-23-1XDDZZ4YV | tRF-39-X553387SHRJL3RE2 | tRF-17-86Z34J2 | tRF-26-727OFIZ9WUD | tRF-36-M2OSRNLNKSEK51B |

| tRF-19-7X9PN5HJ | tRF-20-5BF900BY | tRF-39-HMI8W47W1R7HFEE2 | tRF-43-96L85DMKYUYRLHR0D2 | tRF-17-863IP52 |

| tRF-40-ZSE6YBY4HEJQY1B6 | tRF-38-L85DMKYUYRLHR0D2 | tRF-20-387SDRJH | tRF-26-90YBOZZ7NDD | tRF-40-KEUI1ZXF0N2BD0U6 |

| tRF-20-48Z8SSFK | tRF-17-8689SV2 | tRF-40-JQJYSWRYVMMV5BU6 | tRF-31-I363U0EZY9X1B | tRF-43-ZMB3UEVPQOH7HLWXD2 |

| tRF-31-897PVP941QKSD | tRF-33-Z3M8ZLSSXUOLD2 | tRF-27-90YBOZZ7ND2 | tRF-32-ZPEK45H5KQBFJ | tRF-29-945NB2NZW7HV |

| tRF-18-J6K6UDV | tRF-34-L85DMKYUYRLHIX | tRF-17-W18FLUF | tRF-46-OE0D58ZZJQJYSWRYVMD | tRF-17-W1X6L8L |

| tRF-16-K0SVRND | tRF-16-K53SW1B | tRF-36-P4R8YP9LON4VN1B | tRF-33-PY5P4PW3FJHPW | tRF-34-XRK4WO2F9IY9E2 |

| tRF-17-8SPOL52 | tRF-35-EO7N987X1RJYSX | tRF-20-FP18LPMB | tRF-34-M2OSRNLNKSEKH9 | |

| tRF-31-P4R8YP9LON4VD | tRF-19-URYRSIE2 | tRF-39-YU4QUEVUUMHNU6E2 | tRF-40-XENDBP1IUUK7VZ0R | |

| tRF-20-KS7SB1RH | tRF-21-UUK7VZ0RB | tRF-18-V29K9U0H | tRF-42-YQHQ9M739P8WQ0D52 | |

| tRF-42-Y6IO43ZU2FYOB0152 | tRF-29-34HWH3RXSIHM | tRF-36-VFYDNZDNB2Y0FDD | tRF-17-XU53F8L | |

| tRF-16-3VL8W1B | tRF-18-Z3M8ZL0D | tRF-21-UE3QHMY1B | tRF-23-5BF900BYDO | |

| tRF-16-3KXR3RB | tRF-21-MI7O3B1N0 | tRF-28-2YU04DYJIOD3 | tRF-26-MJ8F81KLB5D | |

| tRF-16-K8QJP1B | tRF-28-R81XDDZZ4YV | tRF-31-QKF1R3WE8RO80 | tRF-27-945NB2NZW7L | |

| tRF-43-7O409Z7KZOSRI8WPD2 | tRF-24-V6Z3M8ZL2J | tRF-26-OB1690PQR3E | tRF-50-JONY8B7OIQ1IBM4LV7U6 | |

| tRF-37-QKF1R3WE8RO86J2 | tRF-26-8DYDZDL9X1B | tRF-22-5OJIH6Z33 | tRF-20-YV45EHBK | |

| tRF-42-YDU37Y93Y086Z34J2 | tRF-20-J0DPZOIP | tRF-16-3QHMY1B | tRF-42-96DNBNHK4B8XVQN52 | |

| tRF-17-KSP1852 | tRF-19-I8W47WFD | tRF-33-V29K9UV36562DE | tRF-30-623K7SIR3DR2 | |

| tRF-26-63U0EZY9X1B | tRF-16-8Z1MQ8E | tRF-26-U3XOUZDZN1B | tRF-26-IQ5O8LZ521B | |

| tRF-17-WJ9X0UF | tRF-16-3VWIQ1B | tRF-30-I363U0EZY9X1 | tRF-20-K87SERM4 | |

| tRF-22-Z3M8ZLSSP | tRF-30-J0DPZOIPD7VI | tRF-21-OB9ZFH69B | tRF-22-KS7SB1RHL | |

| tRF-35-L85DMKYUYRLHR0 | tRF-28-K8HJ83ML5F02 | tRF-39-PSQP4PW3FJIKE727 | tRF-41-XENDBP1IUUK7VZ0RB | |

| tRF-17-RPM830K | tRF-45-NY8B7OIQ1IBM4LV7U6 | tRF-19-I7JP8XI2 | tRF-27-727OFIZ9WUJ | |

| tRF-36-QR535Z8LZBZFD90 | tRF-16-489B3RB | tRF-32-EH623K7SIR3D4 | tRF-17-8S68L52 | |

| tRF-20-598LS7F6 | tRF-36-JVK697BOJ8N981B | tRF-21-LN4Q1RV1B | tRF-41-8HM2OSRNLNKSEK51B | |

| tRF-35-INVDRI2Q2RJO01 | tRF-25-3K7SIR3DR2 | tRF-48-EBXNWD8NBNIED6VZ0OD2 | tRF-17-W6VM4J2 | |

| tRF-48-UIZMB3UEVPQOH7HLWXD2 | tRF-16-8SPOL5D | tRF-39-XU53F85SI1LQ3RE2 | tRF-21-2Q2RJO01B | |

| tRF-38-31QJ3KYUYRR6RBD2 | tRF-49-I3Z9HMI8W47W1R7HFEE2 | tRF-31-ZWRNU3KQ9MV1B | tRF-20-WVZ5EFOK | |

| tRF-20-K87SIRM1 | tRF-32-7EMQ18Y3E7QNN | tRF-23-F9LKXNYQDE | tRF-16-WJ9X0UB | |

| tRF-34-9ZFH690M0RHBFV | tRF-38-YDU37Y93Y086Z3DO | tRF-21-WS7YRR500 | tRF-17-WS3V2V4 | |

| tRF-35-M2OSRNLNKSEK51 | tRF-20-I8W47W1R | tRF-24-F9LKXNYQFP | tRF-22-WJ9X0UD3P | |

| tRF-27-EK45H5KQBFJ | tRF-22-ZFHIUNWV2 | tRF-32-86V8WPMN1E8YN | tRF-35-EH623K7SIR3DR2 | |

| tRF-32-L85DMKYUYRLH4 | tRF-18-F9LKXN05 | tRF-16-Q01LQKB | tRF-18-SRI8WPD2 | |

| tRF-42-5ZLIJXDXXLHQIXKD2 | tRF-32-7Y93Y086Z34J2 | tRF-33-8NBNIED6VZ0OD2 | tRF-37-LP21W3WB8US5652 | |

| tRF-20-OL7XDXOM | tRF-16-3VLIE1B | tRF-21-YDZDL9X1B | tRF-25-HMI8W47W1R | |

| tRF-16-W1X6L80 | tRF-23-8HYV45EH6 | tRF-16-3KMB01B | tRF-30-JMRPFQ5DWXH9 | |

| tRF-21-U0EZY9X1B | tRF-38-WD8NBNIED6VZ0OD2 | tRF-25-R3VJ4ZZ526 | tRF-32-JXDXXLHQIXKD2 | |

| tRF-37-F9LKXNYQIUIVBNK | tRF-41-I9O9IOIQ5O8LZ521B | tRF-25-2IUIX1Q7O6 | tRF-16-362VO00 | |

| tRF-22-7PP9ZZ052 | tRF-33-L85DMKYUYRLHDY | tRF-28-P4R8YP9LOND5 | tRF-31-D890YBOZZ7NDD | |

| tRF-49-WXQZR44ER81XDDZZ4YE2 | tRF-17-F9LKXNQ | tRF-22-8F81KLB52 | tRF-40-2VR0PSR9593J2426 | |

| tRF-30-897PVP941QKS | tRF-34-7N987X1RJYSXI2 | tRF-22-UF04QZ452 | tRF-27-HK4B8XVQN52 | |

| tRF-16-8871K9D | tRF-24-5NB2NZW7HV | tRF-23-YUYRR6RBD2 | tRF-17-KS01852 | |

| tRF-25-1IBM4LV7U6 | tRF-29-E7ZPVOH30W2R | tRF-21-987X1RJY0 | tRF-43-Z6V6Z3M8ZLSSXUOLD2 | |

| tRF-18-RPM830D4 | tRF-32-PW5SVP9N15WVN | tRF-30-KQSX0DIJZ726 | tRF-24-Q6J6K6UDE2 | |

| tRF-23-QOH7HLWXD2 | tRF-28-VPQOH7HLWXD2 | tRF-29-987X1RJYSXI2 | tRF-36-PW5SVP9N15WV7W0 | |

| tRF-23-45H5KQBFD2 | tRF-21-F9LKXNYQB | tRF-19-F9LKXNK2 | tRF-30-VDRI2Q2RJO01 | |

| tRF-36-EO7N987X1RJYSX0 | tRF-32-KRIMUF04QZ452 | tRF-24-7X1RJYSXI2 | ||

| tRF-16-EO7N980 | tRF-18-0RSSX7D2 | tRF-18-86J8WPD4 | hsa-miR-615-3p | |

| tRF-28-5BF900BY4D02 | tRF-18-YSQSD2D2 | tRF-25-J0DPZOIPD7 | ||

| tRF-44-IEYU4QUEVUUMHNU6E2 | tRF-19-K8YUBSI8 | tRF-18-S7PVRSD2 | ||

were in common between the MeT-5A untreated and exposed to 50 ug/ml FE fibers vs. JU77 untreated and exposed to 10 ug/ml FE fibers (Fig. 4D, Table 5). tRF-18-WKXU53DJ, tRF-48-9NZ6V6Z3M8ZLSSXUOLD2, tRF-19-OSM83OJX, tRF-22-7OFIZ9WUJ were the up-regulated tRNA-derived ncRNAs in common between the MeT-5A untreated and exposed to 50 ug/ml FE fibers vs. JU77 untreated and exposed to 50 ug/ml FE fibers (Fig. 4D, Table 5). If we compare MeT-5A exposed to 10 ug/ml FE fibers vs. MeT5A untreated and MeT-5A exposed to 50 ug/ml FE fibers vs. MeT5A untreated and JU77 exposed to 10 ug/ml FE fibers vs. JU77 untreated there was no compound in common (Fig. 4D, Table 5). tRF-28-727OFIZ9WUD2, tRF-18-51MLHVDB, tRF-19-86J8WP1Z, tRF-18-7X9PN5D5, tRF-23-1XDDZZ4YV, tRF-19-7X9PN5HJ, tRF-40-ZSE6YBY4HEJQY1B6, tRF-20-48Z8SSFK, tRF-31-897PVP941QKSD, tRF-18-J6K6UDV, and tRF-16-K0SVRND were the up-regulated tRNA-derived ncRNAs in common among MeT-5A exposed to 50 ug/ml FE fibers vs. MeT5A untreated and JU77 exposed to 10 ug/ml FE fibers vs. JU77 untreated and JU77 exposed to 50 ug/ml FE fibers vs. JU77 untreated (Fig. 4D, Table 5). Among all samples, no up-regulated compound there was in common (Fig. 4D, Table 5).

Surely, between miRNAs and tRNA-derived ncRNAs molecules, the latter were found to be the most deregulated among the samples compared.

The results of the differential expression analysis were reported in Sup. Table 1.

Pathways analysis

Once we identified the differentially expressed miRNAs for each comparison, we tried to investigate the impact of their dysregulation in metabolic and signaling pathways by using MITHrIL50. MITHrIL fully exploits the topological information encoded by pathways when computing perturbation scores. Pathways are then modeled as complex graphs where each node is a biological element (protein-coding gene, miRNA, or metabolite), and each edge is an interaction between them50. Importantly, MITHrIL takes into account experimentally validated miRNA-mRNA interaction in order to predict their effects on biological pathways50.

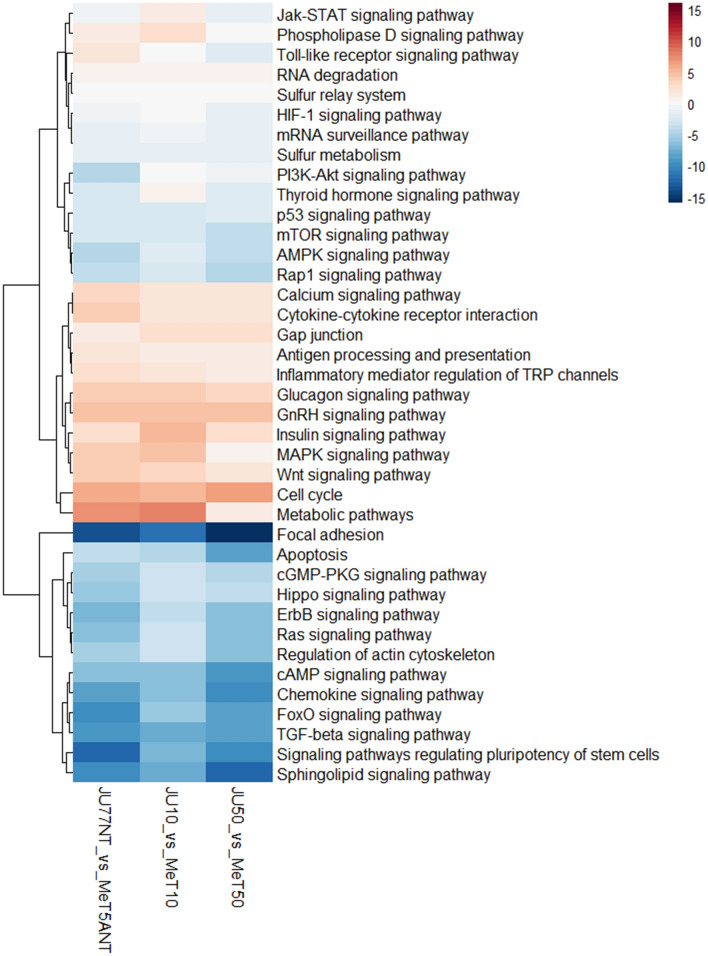

The results demonstrated clear patterns of negative and positive perturbation scores involving 39 different pathways. Considering untreated JU77 vs. MeT-5A, 24 pathways showed a negative perturbation score while 15 pathways showed a positive perturbation score.

A similar trend was found in the case of the JU77 vs. MeT-5A exposed to 10 ug/ml FE fibers, indeed 23 pathways showed a negative perturbation score while 16 pathways showed a positive perturbation score. In fact, the Jak-STAT signaling pathway, the toll-like receptor signaling pathway, and the thyroid hormone signaling pathway showed a different trend between the samples mentioned above. In particular, in samples not exposed and exposed to 10 ug/ml FE fibers, the Jak-STAT signaling pathway and the thyroid hormone signaling pathway showed a negative and positive perturbation score, respectively. Both of these pathways reverse their score again in the samples exposed to the FE fiber concentration equal to 50 ug/ml. On the contrary, the toll-like receptor signaling pathway showed a positive perturbation score in the samples not exposed and a negative perturbation score in the samples exposed to both FE fibers concentrations.

Considering the JU77 vs. MeT5A exposed to 50 ug/ml FE fibers, 26 pathways showed a negative perturbation score while 13 pathways showed a positive perturbation score. Comparing these results with the cells that did not undergo any exposure to FE fibers, the phospholipase D signaling pathway and the toll-like receptor signaling pathway showed a negative perturbation score after FE fibers exposure (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Heatmap showing the dysregulated pathways in JU77 (human malignant mesothelioma) vs. MeT-5A (human normal mesothelium) at the same concentration of FE fibers exposure by taking into account the differentially expressed miRNAs.

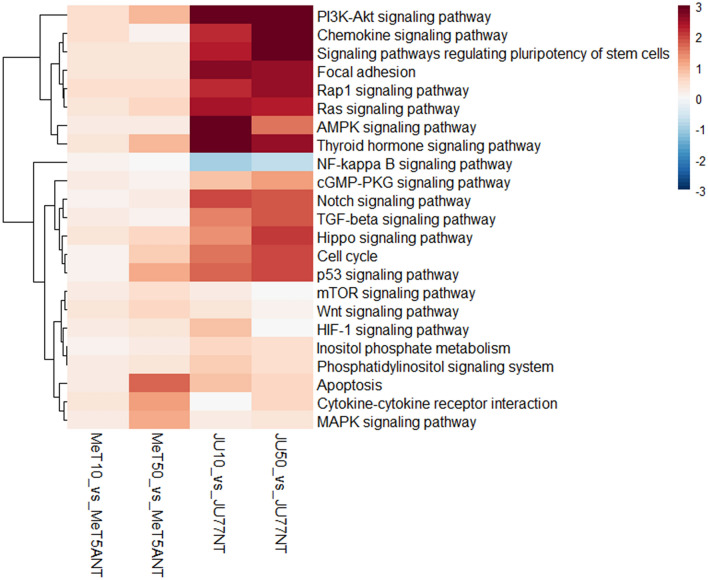

The pathway analysis performed between untreated vs. FE fibers treated JU77 and MeT-5A and the main impacted pathways showed clear patterns of positive correlations involving 23 different pathways. Only the NF-kappa B signaling pathway showed negative perturbation in the neoplastic samples (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Heatmap showing the dysregulated pathways between untreated vs. FE fibers treated JU77 (human malignant mesothelioma) and MeT-5A (human normal mesothelium) by taking into account the differentially expressed miRNAs.

The results of the pathways analysis were reported in Sup. Table 2.

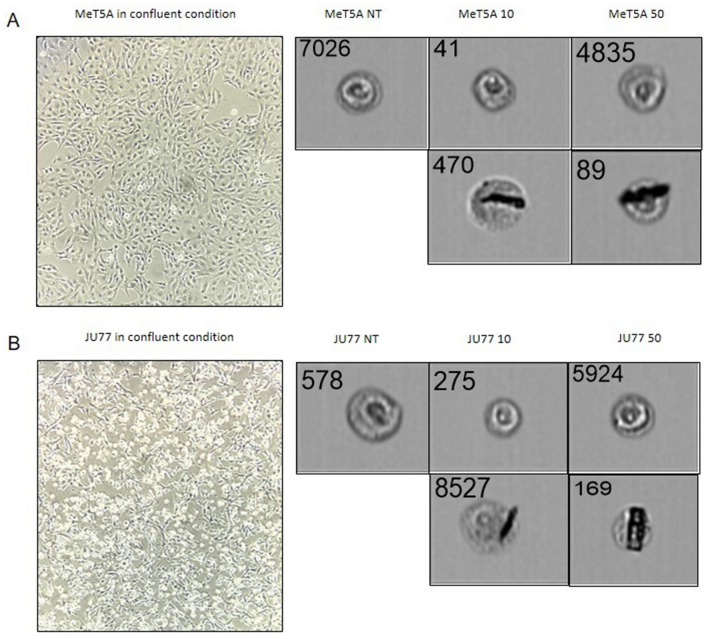

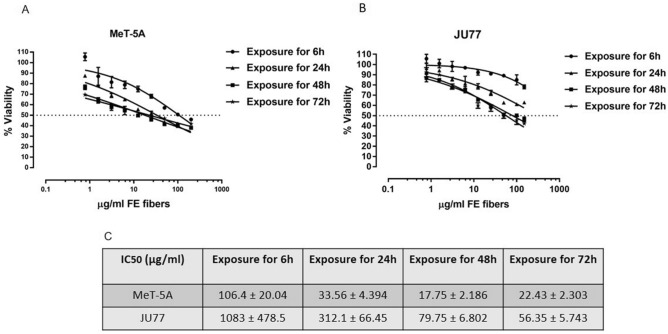

Effects of fluoroedenite exposure in morphology and viability

MeT-5A are epithelial-like cells needle shaped that upon confluence develop a flattened shape. JU77 are epithelial-like cells spindle shaped with few vacuoles. Upon confluent condition assumed the epithelioid “cobblestone-like mat”. Both cell lines do not show evident morphological differences after exposure for 48 h to the different concentrations of FE fibers (10 and 50 µg/ml), with the exception of cells that come into direct contact with the fibers. In fact, these cells incorporate the fibers inside them, as shown in Fig. 7. Therefore, with the exception of the presence of fibers, neoplastic cells are not distinguished from healthy cells by cellular morphology. In accordance with Panzetta et al.51 morphology alone is not sufficient to discriminate malignant cells from benign cells. In addition, the in vitro viability of MeT-5A and JU77 from 6 to 72 h exposure to FE has been evaluated to examine the effects of FE fibers upon mesothelium and MM. The results showed that MeT-5A cells were more sensitive to FE fibers compared to JU77 cells, as shown in Fig. 8.

Figure 7.

Morphology of cells in confluent condition immortalized through Nikon microscope Eclipse Ts2 (magnification 10x), and morphology of single cells immortalized through FlowSight Imaging Flow Cytometer after no exposure, exposure to 10 ug/ml FE fibers, and exposure to 50 ug/ml FE fibers (magnification 20x) for: A) MeT-5A (human normal mesothelium); B) JU77 (human malignant mesothelioma).

Figure 8.

(A) Dose–response curves of MeT-5A (human normal mesothelium) with FE fibers from 200 to 0.78 μg/ml until 72 h of treatments; (B) Dose–response curves of JU77 (human malignant mesothelioma) with FE fibers from 200 to 0.78 μg/ml from 6 to 72 h of treatments; (C) IC50 values (μg/ml) for MeT-5A and JU77 cell lines.

Mesothelioma knowledge-network inference

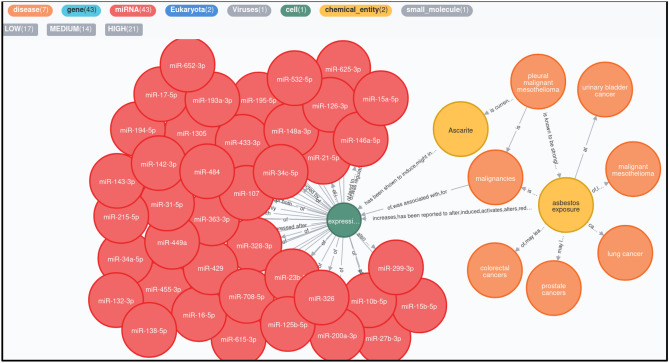

NetME47 has been used to recover known interactions among malignant mesothelioma, asbestos, miRNAs, and other biological elements. For this purpose, we selected (through the NCBI APIs) the whole set of PubMed Central (PMC)46 documents related to the term “mesothelioma” in at least one of the following document sections: title, abstract, full text, references. The downloaded papers consist of 17.762 documents. Then, NetME generated the mesothelioma network as follows: (i) First, NetME converted the full text of the input documents into a list of nodes (biological entities) through literature databases and ontologies (Drug-Bank52, DisGenNET53, Obofoundry54, PubChem55); (ii) Next, an NLP model, based on Python SpaCy56 and NLTK57 libraries, has been executed to infer relations among nodes belonging to the same sentence (Si) or adjacent ones (Si, Si+1) of the same document. Such relationships represent disease-disease interactions, disease-gene interactions, gene regulations, molecular functions, etc. The network is composed of 2,468,187 nodes and 8,508,601 edges, and it is released in csv format to be loaded in Neo4j48, cytoscape49, or other graph visualization systems. The mesothelioma network was reported in Sup. csv files 1 and 2. Table 2 shows the most relevant sentences from 38 papers analyzed by NetME to infer the knowledge network. From these documents, it is clear how several miRNAs were involved in apoptosis, necrosis, and cell growth inhibition. Among these, the main miRNAs studied are miR-302b, miR-192, and miR-193a. The miR-193b is involved in the autophagy process while miR-1, miR-34a, miR-215, miR-16, miR-320a, and miR-21 seem to participate as oncogenes or oncosuppressors in malignant mesothelioma. To date, in literature, there are no papers that have analyzed tRNA-derived ncRNAs in malignant mesothelioma both induced and not induced by FE fibers. Data collected by NetME showed several research papers that demonstrated the correlation between asbestos exposure and different cancers. In fact, breathing asbestos fibers causes not only malignant mesothelioma, but also may lead to laryngeal cancer, prostate cancer, colorectal cancer, lung cancer, and ovarian cancer. Malignant mesothelioma and lung cancer have also been associated with exposure to carbon nanotubes. In Fig. 9, is shown the mesothelioma-miRNAs interactions network achieved by running the following cypher query against the whole mesothelioma network (stored in neo4j db): MATCH (n1:disease {name:”pleural malignant mesothelioma”})-[:*1.0.3]- > (n2:miRNA). Where, n1 (disease) and n2 (miRNAs) are the source and destination nodes, respectively. While, the term [:*1.0.3] selects all the paths (collections of nodes and edges into the network) from n1 to n2 having a minimum length of 1 and a maximum of 3. For example: path: (asbestos exposure)-[increases]- > (expression)-[of]- > (miR-107).

Figure 9.

Mesothelioma-miRNAs network showing the relationships among pleural malignant mesothelioma disease and miRNAs derived from the PubMed Central full texts by using NetME tool. Such a network has been queried and displayed through Neo4j graph database and user interface.

Each path has been inferred through the NetME syntactic analysis performed over the mesothelioma-based documents collected in PubMed Central.

Discussion

Small RNA-Seq transcriptome profiling of healthy mesothelium and MPM in vitro has been evaluated to highlight the deregulated miRNAs and tRNA-derived ncRNAs and the different pathways involved in an aggressive cancer such as MPM.

The results showed that MeT-5A cells were more sensitive to FE fibers compared to JU77 cells and that morphology alone is not sufficient to discriminate malignant cells from benign cells. Certainly, a big difference was found in the number of deregulated miRNAs and tRNA-derived ncRNAs between tumor and non-tumor samples both exposed and not exposed to FE fibers. The common population of differentially expressed miRNAs and tRNA-derived ncRNAs between the two cell lines increased with the exposure to FE fibers. Though, the effect of exposure to FE fibers is more evident in the expression of miRNA and tRNA-derived ncRNAs in tumor samples than in non-tumor samples. Within the same cell line, the effect of exposure to FE fibers caused a dose-dependent increase in differentially expressed miRNAs and tRNA-derived ncRNAs. While the increase was noticeable in MeT-5A cells, in JU77 cells this was less pronounced. In the latter, in fact, the differentially expressed miRNAs and tRNA-derived ncRNAs were already many even in the neoplastic cells that had not undergone treatment with the cancer-causing fibers.

Several molecules aroused interest in their behavior in the various samples analyzed. Among them is a list of down-regulated and up-regulated miRNAs and tRNA-derived ncRNAs in common both between the two cell lines, and the different conditions of exposure with the FE fibers. While tRNA-derived ncRNAs have never been explored in the MPM, miRNAs have already been studied in this context. Several miRNAs are considered potential tumor suppressors in MPM. Expression of miR-15/16 family was consistently down-regulated both in MPM specimens and in cell lines and had tumor suppressor function in MPM58, in accordance with our results. miR-193a-3p is also considered a potential tumor suppressor in MPM59, indeed these miRNAs belonging to the group of mesomiRs (MM-associated miRNAs)60,61 could be considered a novel therapeutic approach for MPM.

In the present paper, we analyzed several pathways that are involved in the pathogenesis of malignant mesothelioma. It is very interesting to point out the strong perturbation scores involving the above-mentioned pathways in MPM vs. healthy mesothelial cells. Among these, there was the involvement of pathways that have important functions in inflammatory processes and in angiogenesis. Pathways that showed a different trend in healthy vs tumor samples at different FE fiber exposures were Jak-STAT, phospholipase D, toll like receptors, and thyroid hormone signaling pathways. Jak-STAT signaling pathway is involved in processes such as cell death, and carcinogenesis62. Phospholipase D activity is significantly increased in cancer tissues and cells, indicating that it plays a critical role in signal transduction, cell proliferation, and anti-apoptotic processes. In addition, phospholipase D is a downstream transcriptional target of proteins that contribute to inflammation and carcinogenesis such as Sp1, NF-kappa B, TCF4, ATF-2, NFATc2, and EWS-Fli63. Instead, toll like receptors have roles and functions in anti-cancer immunity and in tumor rejection64. Thyroid hormones not only regulate the physiological processes of normal cells but also stimulate cancer cell proliferation via dysregulation of molecular and signaling pathways65. Inflammation plays a central role since mesothelioma is a multicentric neoplasm, which originates from inflammatory foci. Inflammation has been correlated with cancer, enhancing the development of malignancies66. In particular, the chemokine and TGF-beta signaling pathways lead to acute and chronic inflammation, the latter resulting in several fiber-associated pulmonary and pleural diseases14,67. The inflammasome is responsible for the activation of inflammatory processes via multiple mechanisms67 that induce a process of cell death called pyroptosis, characterized by both apoptosis and necrosis. Cell death mechanisms and release of chemokines and cytokines may help cancer regress, and resist toxicity by fibers and cell growth68, in inflammasome-dependent and -independent pathways69. Indeed, apoptosis is a mechanism for removing cells with irreparable damage induced by FE fibers, causing genetic changes that predispose cells to a neoplastic transformation70. Specific signaling pathways such as sphingolipid, FoxO, and Hippo pathways are involved in many important signal transduction processes such as cell proliferation, and apoptosis71–73. Dysregulation of the Hippo signaling pathway is highly conserved by phosphorylating and inhibiting the transcription co-activators YAP and TAZ, key regulators of proliferation and apoptosis. On the contrary, dephosphorylated YAP/TAZ translocates into the nucleus and activates gene transcription through binding to TEAD family and other transcription factors. Such changes in gene expression promote cell proliferation and stem cell/progenitor cell self-renewal but inhibit apoptosis, thereby promoting tissue regeneration, and tumorigenesis72. An experimental model demonstrated the activation of YAP caused by ATG7 deletion74, which is an important transcription activator in malignant mesothelioma75. In our recent research, ATG7's high expression represents a promising prognostic tool for patients with MPM76, thus it would be interesting to explore if there is an inverse correlation between ATG7 and YAP in malignant mesothelioma. The leukocyte migration to the site of injury is led by chemokines. The first to be recruited to the site of injury are neutrophils, followed by monocytes, which differentiate into macrophages. Macrophages, once activated, are the main source of growth factors and cytokines which influence the local microenvironment. Mast cells, such as histamine, cytokines, proteases, and lipid mediators also contribute to inflammatory mediators77. In previous studies14,78–80, it was demonstrated the involvement of cytokines IL-18, IL-1beta, and NF-kappa B in the inflammasome activation process, suggesting that these immune-modulators are involved in the pathogenic mechanisms triggered by asbestos fibers. Acute and chronic inflammations often generate common molecular mediators70. The higher inflammation, with greater angiogenesis, causes the fatal outcome of the neoplasm. The release of angiogenic cytokines, including TGF-beta and VEGF, occurs during the angiogenesis process in the malignant mesothelioma progression81,82. In particular, VEGF represents the principal angiogenic cytokine involved in this cancer81,83, modulating also the development of pleural effusion and ascites through an increase in vascular permeability84. VEGF activation plays an essential role in increasing the survival of normal cells exposed to carcinogenic agents. The FE fibers are able to induce functional modifications of parameters with crucial roles in cancer development and progression9. The synthesis of VEGF and beta-catenin, two critical steps of epithelial cell activation pathways, are affected by the FE fibers exposure shown by an abnormal cellular status with upregulated cell activities and a risk of neoplastic transformation85. Furthermore, the influence of the FE fibers on cell motility has been demonstrated through a dysregulated and altered distribution of actin network85. Focal adhesion, which forms mechanical links between cytoskeleton and extracellular matrix (ECM), and adherens junction, result clearly involved in malignant mesothelioma pathogenesis. About that, our recent study, on FE exposure in lung fibroblasts, suggested an ECM remodeling that can give rise to profibrotic cellular phenotypes and tumor microenvironment86.

Specific signaling pathways have been found to be involved in malignant mesothelioma. Among these, Ras and p53, the commonly mutated genes associated with cancer, are rarely targeted in malignant mesothelioma87. Ras has not been found to be mutated in mesothelioma cell lines88,89. However, several receptor tyrosine kinase pathways have been shown to be activated in mesothelioma including the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), insulin-like growth factor receptor (IGFR), and c-Met90–92, all of which activate Ras signaling. According to these results, several studies have already suggested that the PI3K-Akt pathway is hyperactivated in mesothelioma cell lines87,93, resulting in the gain or loss of function of its downstream proteins, 4E-BP1 and pS6, both crucial to the regulation of protein synthesis94. But, the prognostic role of the PI3K pathway in MPM is not yet defined95.

From papers analyzed by NetME to infer the knowledge network, it is clear that many miRNAs have the ability to positively or negatively influence various pathways involved in apoptosis, necrosis, cell cycle, and cell growth inhibition in malignant mesothelioma, in accordance with our experimental results. Among these,… Furthermore, several pathways, emerging from the literature involved in asbestos exposure, are in common with our data obtained from the expression profiles of miRNAs of healthy mesothelium and MPM in vitro both exposed and not exposed to FE fibers. Among the signaling pathways emerging from our in vitro analyses, we found that some of them are in common with the results processed by NetME. These include e.g. the NF-kappa B, p53, …. already discussed above. Surely, the computational analysis performed to establish the functional role of miRNAs in MPM pathogenesis has shown that these miRNAs can target genes playing a potentially key role in inflammatory processes, angiogenesis, and tumor cell development. Furthermore, miRNAs reach their biological impact by targeting multiple genes with similar biological effects96 thus, finding potential biomarkers is a very difficult aim that provides a lot of research work. However, surprising results emerged from the expression analysis of tRNA-derived ncRNAs, which have not yet aroused interest in the literature regarding their use as new potential biomarkers in malignant mesothelioma.

After this first preliminary work, the analysis will be followed by the validation of the most significantly deregulated miRNAs by RT-qPCR in an independent sample set. Subsequently, this screening of microRNAs and tRNA-derived ncRNAs will allow us to validate the most interesting and promising results as potential biomarkers for MPM. Our goal is the validation of the most promising results in patients chronically exposed to FE using the liquid biopsy, to provide a minimally invasive screening method for the secondary prevention of MPM. Early detection of circulating tumor biomarkers represents one of the most promising strategies to enhance the survival of cancer patients by increasing treatment efficiency61,97. Besides this large amount of data, further studies will be designed for the selection of the most significant miRNAs and tRNA-derived ncRNAs to test and validate their diagnostic potential in high-risk individuals.

Methods

Cell cultures

Human normal mesothelium (MeT-5A cells) and human malignant mesothelioma (JU77 cells) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA, USA). Both cell lines have been cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute 1640 (RPMI 1640) medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% L-glutamine (Lonza; Walkersville, MD, USA), 1% non-essential amino acids solution (Gibco by Thermo Fisher Waltham; Massachusetts, USA), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Lonza; Walkersville, MD, USA). The culture conditions were 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. The MeT-5A and JU77 cell lines were split 1:3 and 1:6 respectively, twice a week.

Cells in confluent condition were separated from the culture flask (SPL Life Sciences; Korea) using 0.25% trypsin in 2.21 mM EDTA solution (Corning; Manassas, VA, USA) and counted using Bürker chamber by Trypan Blue Stain 0.4% (Gibco by Life Technologies; NY, USA)10. The cells have been used for the experiments between the III and IV passages.

In vitro treatments for RNA-Seq transcriptome profiling

FE fibers were collected from the Biancavilla quarry (Sicily, Italy). These were sterilized under UV light for 10 min, suspended in RPMI 1640 medium, and sonicated through Omni-Ruptor 4000 Ultrasonic Homogenizer (OMNI INternational Inc.; Kennesaw, GA, USA) for 10 min10. The stock solution was then diluted appropriately to obtain the different concentrations for in vitro treatments.

MeT-5A and JU77 were plated onto 100 × 20 mm Petri Dishes (Eppendorf; Hamburg, Germany) at the density of 1 × 106 cells and 8.5 × 105 cells, respectively. After 24 h of incubation, the medium of both cell lines has been removed and replaced with FE fibers solutions to final concentrations of 50 and 10 ug/ml. MeT-5A and JU77 cells grown in normal medium were used as controls. After 48 h from FE fibers exposure, pellets have been collected in duplicate.

After elimination of the supernatant, cells were harvested on ice by scraping in cold Dulbecco’s Phosphate-Buffered Saline (DPBS) (Corning; Manassas, VA, USA). Cells are then centrifuged at 0.2 × g for 5 min at 4 °C and suspended in 1 ml cold DPBS. The cell solution was transferred to Eppendorf tubes. Cells were centrifuged at 0.8 × g for 5 min at 4 °C and supernatant has been removed10. The samples have been stored to—80 °C until RNA isolation.

RNA isolation

Total RNA containing small non-coding RNA was extracted from the cell lines using miRNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN; Venlo, Netherlands) according to the manufacturer’s recommended protocols (miRNeasy Mini Handbook 11/2020). The RNA was directly quantified by the absorbance ratio at λ = 260/280 nm through NanoDrop (ND 1000) UV–Vis spectrophotometer10,98. All samples were diluted at the final concentration of 50 ng/µl for the subsequent analysis.

Small RNA-Seq

QIAseq miRNA library kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) has been used for small RNA-Seq library preparation following the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA samples were quantified and quality tested by Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer RNA assay (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Libraries were then checked with both Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and Agilent Bioanalyzer DNA assay or Caliper (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA). Finally, libraries were prepared for sequencing and sequenced on single-end 150 bp mode on NovaSeq 6000 (Illumina, San Diego, CA).

Small RNA-Seq analysis

Low-quality reads and adapters were trimmed using Trim Galore, which is a wrapper of FASTQC99 and Cutadapt100. After that, for miRNA analysis, trimmed reads were aligned onto the reference human genome (HG38 version) using HISAT2101. The generated SAM files were first converted into BAM files using Samtools102, and second, mapped reads were quantified by featureCounts (parameters: -d 14 –primary) using the GTF annotation file retrieved from miRBase103. All the above-mentioned steps for the miRNA analysis were performed using RNAdetector104 software. Concerning the tRNA-derived ncRNA analysis, we first generated an indexed transcriptome using Bowtie 2105 containing tsRNA and 5’ leader pre-tRNA sequences retrieved from tRFexplorer106. After that, trimmed reads were mapped on the indexed transcriptome using Bowtie 2 in order to filter them from the reads that may map on tRFs. Filtered mapped reads in SAM format were then converted into BAM files by Samtools102, and tsRNAs and 5’ leader pre-tRNA sequences were quantified by using bedtools (multicov -q 30). Unfiltered reads in FASTQ format that did not map on tsRNA and 5’ leader pre-tRNA sequences were given as input to MINTmap107 for identifying and quantifying reads associated with tRFs. After that, the raw counts obtained from the miRNA and tRNA-derived ncRNAs analyses were all harmonized together in order to have a single raw count matrix that can be used for the differential expression analysis. The raw count values were then normalized to scale the raw library sizes in Trimmed Mean of M values (TMM) by using edgeR108 and all miRNAs and tRNA-derived ncRNAs whose geometric mean of TMM values across all samples were less than one were removed from the analysis because they were non-expressed or expressed at a very low level. Finally, the filtered count matrix was used for the differential expression analysis using LIMMA109. miRNA and tRNA-derived ncRNAs with a |Log2FC|> 0.58 and an adjusted p-value (Benjamini–Hochberg correction) < 0.05 were considered differentially expressed. Finally, the impact of differentially expressed miRNAs on biological pathways was evaluated by using MITHrIL50. In this case, we selected all miRNAs with significant adjusted p-values without a Log2FC cutoff in order to evaluate also the impact of slightly differentially expressed miRNAs on biological pathways.

Determination of dose–response curves and IC50

For the determination of dose–response curves, MeT-5A were plated onto 96-well plates at the density of 6 × 103 cells/50 μl while JU77 were plated at the density of 4 × 103 cells/50 μl. After 24 h of incubation, 50 μl of FE fibers solutions were added to the cell cultures in amounts corresponding to final concentrations of 200, 100, 50, 25, 12.5, 6.25, 3.12, 1.56, 0.78 μg/ml. Both cell lines grown in FE-free medium were used as controls. At each time point (6, 24, 48, 72 h of FE exposure) in cell culture, 10% MTT in DPBS has been added to each well. After 4 h of incubation, the lysis solution has been added to each well. The optical density was measured with an absorbance microplate reader at λ = 620 nm. For each sample, 3 replicates were performed. Cell viability was calculated as the percentage of viable cells exposed to FE fibers vs.. control cells no exposed as follows:

Cell viability (%) = [OD (Treatment) − OD (Blank)]/[OD (Control) − OD (Blank)] × 100. IC50 values have been calculated through the following equation:

[Inhibitor] vs. normalized response–Variable slope.

Results have been analyzed using PRISM GraphPad v. 7.00 and data were represented as the mean ± SD. An unpaired Student's t-test was used to compare data between the two groups. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

VF: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft Prepara-tion. ALF: Formal Analysis, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft Preparation. ADM: Formal Analysis, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft Preparation. VC: Conceptualiza-tion, Methodology, Writing—Review and Editing. ACEG: Formal Analysis. VR: Conceptu-alization, Visualization. Cle: Conceptualization, Writing—Review and Editing. AP: Con-ceptualization, Methodology, Writing—Review and Editing, Supervision. CLo: Validation, Supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received funding by 2020/2021 PIA.CE.RI.—DIPREME project (UPB: 20722142130).

Data availability

Raw sequencing data will be deposited on NCBI SRA while processed data will be deposited on GEO". Raw data have been uploaded on SRA, BioProject ID: PRJNA812748.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Alfredo Pulvirenti and Carla Loreto.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-13044-0.

References

- 1.Bibby AC, et al. Malignant pleural mesothelioma: an update on investigation, diagnosis and treatment. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2016;25:472–486. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0063-2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koskinen K, et al. Screening for asbestos-induced diseases in Finland. Am. J. Ind. Med. 1996;30:241–251. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0274(199609)30:3<241::AID-AJIM1>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pan X-L, Day HW, Wang W, Beckett LA, Schenker MB. Residential proximity to naturally occurring asbestos and mesothelioma risk in California. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2005;172:1019–1025. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200412-1731OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luo, S., Liu, X., Mu, S., Tsai, S. P. & Wen, C. P. Asbestos related diseases from environmental exposure to crocidolite in Da-yao, China. I. Review of exposure and epidemiological data. Occup. Environ. Med.60, 35–41; discussion 41–2 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Rey F, et al. Environmental pleural plaques in an asbestos exposed population of northeast Corsica. Eur. Respir. J. 1993;6:978–982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baumann F, et al. Pleural mesothelioma in New Caledonia: associations with environmental risk factors. Environ. Health Perspect. 2011;119:695–700. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McConnochie K, et al. Mesothelioma in Cyprus: the role of tremolite. Thorax. 1987;42:342–347. doi: 10.1136/thx.42.5.342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Constantopoulos SH. Environmental mesothelioma associated with tremolite asbestos: lessons from the experiences of Turkey, Greece, Corsica, New Caledonia and Cyprus. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2008;52:S110–S115. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Filetti V, et al. Update of in vitro, in vivo and ex vivo fluoro-edenite effects on malignant mesothelioma: A systematic review (Review) Biomed. Rep. 2020;13:60. doi: 10.3892/br.2020.1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Filetti V, et al. Modulation of microRNA expression levels after naturally occurring asbestiform fibers exposure as a diagnostic biomarker of mesothelial neoplastic transformation. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020;198:110640. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.110640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biggeri A, et al. Mortality from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and pleural mesothelioma in an area contaminated by natural fiber (fluoro-edenite) Scand. J. Work Environ. Health. 2004;30:249–252. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grosse Y, et al. Carcinogenicity of fluoro-edenite, silicon carbide fibres and whiskers, and carbon nanotubes. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:1427–1428. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71109-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ledda C, et al. Natural carcinogenic fiber and pleural plaques assessment in a general population: a cross-sectional study. Environ. Res. 2016;150:23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2016.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ledda C, et al. Immunomodulatory effects in workers exposed to naturally occurring asbestos fibers. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017;15:3372–3378. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.6384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ledda C, Rapisarda V. Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma: The Need to Move from Research to Clinical Practice. Arch. Med. Res. 2016;47:407. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2016.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loreto, C. et al. Defense and protection mechanisms in lung exposed to asbestiform fiber: the role of macrophage migration inhibitory factor and heme oxygenase-1. Eur. J. Histochem.64, (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Loreto C, et al. Activation of caspase-3 in malignant mesothelioma induced by asbestiform fiber: an in vivo study. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents. 2020;34:1163–1166. doi: 10.23812/19-441-L-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Romano G, Veneziano D, Acunzo M, Croce CM. Small non-coding RNA and cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2017;38:485–491. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgx026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quinn L, Finn SP, Cuffe S, Gray SG. Non-coding RNA repertoires in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Lung Cancer. 2015;90:417–426. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Di Bella S, et al. A benchmarking of pipelines for detecting ncRNAs from RNA-Seq data. Brief. Bioinform. 2019 doi: 10.1093/bib/bbz110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.La Ferlita A, et al. Non-coding RNAs in endometrial physiopathology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19:2120. doi: 10.3390/ijms19072120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Calin GA, et al. Frequent deletions and down-regulation of micro- RNA genes miR15 and miR16 at 13q14 in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:15524–15529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242606799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peng, Y. & Croce, C. M. The role of MicroRNAs in human cancer. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy vol. 1 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Wang H, Peng R, Wang J, Qin Z, Xue L. Circulating microRNAs as potential cancer biomarkers: the advantage and disadvantage. Clin. Epigenetics. 2018;10:59. doi: 10.1186/s13148-018-0492-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Balatti V, Pekarsky Y, Croce CM. Role of the tRNA-derived small RNAs in cancer: new potential biomarkers and target for therapy. Adv. Cancer Res. 2017;135:173–187. doi: 10.1016/bs.acr.2017.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li S, Xu Z, Sheng J. tRNA-derived small RNA: a novel regulatory small non-coding RNA. Genes. 2018;9(5):246. doi: 10.3390/genes9050246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee YS, Shibata Y, Malhotra A, Dutta A. A novel class of small RNAs: tRNA-derived RNA fragments (tRFs) Genes Dev. 2009;23:2639–2649. doi: 10.1101/gad.1837609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar P, Anaya J, Mudunuri SB, Dutta A. Meta-analysis of tRNA derived RNA fragments reveals that they are evolutionarily conserved and associate with AGO proteins to recognize specific RNA targets. BMC Biol. 2014;12:78. doi: 10.1186/s12915-014-0078-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu W-L, Yang Y, Wang Y-D, Qu L-H, Zheng L-L. Computational approaches to tRNA-derived small RNAs. Noncoding RNA. 2017;3(1):2. doi: 10.3390/ncrna3010002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cole C, et al. Filtering of deep sequencing data reveals the existence of abundant Dicer-dependent small RNAs derived from tRNAs. RNA. 2009;15:2147–2160. doi: 10.1261/rna.1738409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kumar P, Kuscu C, Dutta A. Biogenesis and Function of Transfer RNA-Related Fragments (tRFs) Trends Biochem. Sci. 2016;41:679–689. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2016.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim HK, et al. A transfer-RNA-derived small RNA regulates ribosome biogenesis. Nature. 2017;552:57–62. doi: 10.1038/nature25005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schorn AJ, Gutbrod MJ, LeBlanc C, Martienssen R. LTR-retrotransposon control by tRNA-derived small RNAs. Cell. 2017;170:61–71.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ivanov P. Emerging roles of tRNA-derived fragments in viral infections: the case of respiratory syncytial virus. Mol. Ther. J. Am. Soc. Gene Ther. 2015;23:1557–1558. doi: 10.1038/mt.2015.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saikia M, et al. Angiogenin-cleaved tRNA halves interact with cytochrome c, protecting cells from apoptosis during osmotic stress. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2014;34:2450–2463. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00136-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Balatti V, et al. tsRNA signatures in cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2017;114:8071–8076. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1706908114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pekarsky Y, et al. Dysregulation of a family of short noncoding RNAs, tsRNAs, in human cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016;113:5071–5076. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1604266113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Slack FJ. Tackling tumors with small RNAs derived from transfer RNA. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018;378:1842–1843. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr1716989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang B, et al. tRF/miR-1280 Suppresses stem cell-like cells and metastasis in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2017;77:3194–3206. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-3146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shao Y, et al. tRF-Leu-CAG promotes cell proliferation and cell cycle in non-small cell lung cancer. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2017;90:730–738. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.12994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kuscu C, et al. tRNA fragments (tRFs) guide Ago to regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally in a Dicer-independent manner. RNA. 2018;24:1093–1105. doi: 10.1261/rna.066126.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao C, et al. 5′-tRNA halves are dysregulated in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. J. Urol. 2018;199:378–383. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2017.07.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yeri A, et al. Total extracellular small RNA profiles from plasma, saliva, and urine of healthy subjects. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:44061. doi: 10.1038/srep44061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dhahbi, J. M., Spindler, S. R., Atamna, H., Boffelli, D. & Martin, D. I. K. Deep Sequencing of Serum Small RNAs Identifies Patterns of 5′ tRNA Half and YRNA Fragment Expression Associated with Breast Cancer. Biomark Cancer6, BIC.S20764 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Godoy PM, et al. Large differences in small RNA composition between human biofluids. Cell Rep. 2018;25:1346–1358. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Beck, J. Report from the Field: PubMed Central, an XML-based Archive of Life Sciences Journal Articles. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on XML for the Long Haul: Issues in the Long-term Preservation of XML10.4242/balisagevol6.beck01.

- 47.Muscolino, A. et al. NETME: On-the-Fly Knowledge Network Construction from Biomedical Literature. in Complex Networks and Their Applications IX 386–397 (Springer International Publishing, 2021). 10.1007/978-3-030-65351-4_31.

- 48.Needham, M. & Hodler, A. E. Graph Algorithms: Practical Examples in Apache Spark and Neo4j. (‘O’Reilly Media, Inc., 2019).

- 49.Shannon P, et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alaimo S, et al. Post-transcriptiona.l knowledge in pathway analysis increases the accuracy of phenotypes classification. Oncotarget. 2016;7:54572–54582. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Panzetta V, Musella I, Fusco S, Netti PA. ECM Mechanoregulation in Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Front Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022;10:797900. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2022.797900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wishart DS, et al. DrugBank 5.0: a major update to the DrugBank database for 2018. Nucl. Acids Res. 2018;46:D1074–D1082. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]