Abstract

Background

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) impacts quality of life. We assessed patient-reported outcomes (PROs), pain, fatigue, health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and work productivity in a phase III trial of tofacitinib.

Methods

Adults with AS and with inadequate response/intolerance to ≥2 non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs received tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily or placebo for 16 weeks. Afterwards, all received open-label tofacitinib until week 48. Change from baseline to week 48 was determined for PROs: total back pain; nocturnal spinal pain; Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) overall spinal pain (Q2); Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue; BASDAI fatigue (Q1); AS Quality of Life (ASQoL); Short Form-36 Health Survey Version 2 (SF-36v2); EuroQoL-Five Dimension-Three Level health profile and Visual Analogue Scale; and the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI) questionnaire. Improvements from baseline ≥minimum clinically important difference, and scores ≥normative values at week 16 were evaluated.

Results

In 269 randomised and treated patients, at week 16, there were greater least squares mean improvements from baseline with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily versus placebo in BASDAI overall spinal pain (–2.85 vs –1.34), BASDAI fatigue (–2.36 vs –1.08), ASQoL (–4.03 vs –2.01) and WPAI overall work impairment (–21.49 vs –7.64) (all p<0.001); improvements continued/increased to week 48. Improved spinal pain with tofacitinib was seen by week 2. Patients receiving tofacitinib reported clinically meaningful PRO improvements at week 16. Percentages with PRO scores ≥normative values at week 16 were greater with tofacitinib in SF-36v2 Physical Component Summary, physical functioning and bodily pain domains (p≤0.05).

Conclusions

In patients with AS, treatment with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily resulted in clinically meaningful improvements in pain, fatigue, HRQoL and work productivity versus placebo to week 16, which were sustained to week 48.

Trial registration number

Keywords: Antirheumatic Agents, Inflammation, Patient Reported Outcome Measures

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC.

The efficacy of tofacitinib has been demonstrated for patients with active ankylosing spondylitis (AS) in phase II and III trials.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

This study provides further evidence of tofacitinib’s effectiveness in AS.

Tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily was associated with clinically meaningful improvements compared with placebo, up to week 16, across a wide range of patient-reported outcomes, including pain, fatigue, health-related quality of life and work productivity. Improvements continued or increased to week 48.

Improvements in pain and fatigue with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily were reported as early as week 2.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE AND/OR POLICY

These findings show promise for patients with AS experiencing debilitating symptoms such as pain, stiffness and fatigue.

Introduction

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS), also known as radiographic axial spondyloarthritis, is a chronic inflammatory arthritis with an estimated incidence rate of 0.4–15.0 per 100 000 patient-years.1 AS predominantly manifests as back pain, although peripheral joints and extra-musculoskeletal structures may also be impacted.2 Key symptoms of AS include pain, stiffness, restricted spinal mobility and fatigue.2 3 Patients with AS experience reduced work productivity and increased rates of absenteeism (sick leave), along with reduced quality of life.2 4

According to the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society (ASAS)/EULAR, treatments for AS should aim to maximise health-related quality of life (HRQoL) via control of inflammation and symptoms such as pain and fatigue, inhibition of structural damage progression, and maintenance or normalisation of function and social involvement.5

The ASAS/EULAR, American College of Rheumatology/Spondylitis Association of America/Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network, and Asia-Pacific League of Associations for Rheumatology recommend non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) as a first-line treatment option in AS, followed by biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARDs).5–7 In patients with an inadequate response (IR) or intolerance to these therapies (approximately 40%),8 9 there is an unmet need for convenient oral treatment options with alternative mechanisms of action.

Tofacitinib is an oral Janus kinase inhibitor for the treatment of adult patients with AS. The efficacy and safety of tofacitinib in patients with active AS with IR or intolerance to NSAIDs (NSAID-IR) has been demonstrated in 16-week, phase II (NCT01786668)10 and 48-week, phase III trials (NCT03502616).11 Compared with placebo, tofacitinib demonstrated greater efficacy associated with improvements in patient-reported outcomes (PROs) relating to disease activity, mobility, function and HRQoL.

The objective of the current analysis was to evaluate the effect of tofacitinib on patient-reported pain, fatigue, HRQoL and work productivity in patients with active AS enrolled in the phase III randomised controlled trial (RCT). The percentages of patients reporting PRO improvements ≥minimum clinically important difference (MCID) and scores ≥normative values were investigated for each treatment arm in this trial.

Methods

Study design

This was a 48-week, phase III, placebo-controlled RCT. Full details have been reported previously, along with the primary efficacy and safety analyses.11

Briefly, patients were aged ≥18 years, had a diagnosis of AS, were NSAID-IR and fulfilled modified New York criteria (documented with central reading of the radiograph of the sacroiliac joints), with active disease at screening and baseline, defined as a Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) score ≥4 and a back pain score (BASDAI overall spinal pain; question 2) ≥4. Approximately 80% were to be bDMARD-naïve, and approximately 20% were to have an IR to ≤2 tumour necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi) or prior bDMARD (TNFi or non-TNFi) use without IR (non-IR).

In the double-blind phase, patients were randomised 1:1 to receive tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily or placebo for 16 weeks. After week 16, all patients received open-label tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily to week 48. Investigators, patients and the study sponsor team remained blinded to the first 16 weeks of assigned treatment for the entire duration of the trial until database release. Certain stable background therapies could be continued: NSAIDs; methotrexate (≤25 mg/week); sulfasalazine (≤3 g/day) and oral corticosteroids (≤10 mg/day of prednisone or equivalent). Patients who completed the study or were withdrawn from treatment after week 40 underwent a follow-up visit approximately 28 days after the week 48 visit.

Assessment of PROs

PROs were assessed to week 48 in the following four domains: pain, fatigue, HRQoL and work productivity.

Patient-reported pain included: total back pain and nocturnal spinal pain, by a numerical rating scale (NRS; range 0–10; higher values indicate worse pain)12 and BASDAI overall spinal pain (question 2 ‘How would you describe the overall level of AS neck, back or hip pain you have had?’) (NRS).13 14

Fatigue was evaluated using the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-F) total score (range 0–52; lower scores indicate more fatigue), which includes the experience (range 0–20) and impact (range 0–32) domains,15–18 as well as BASDAI fatigue (question 1 ‘How would you describe the overall level of fatigue/tiredness you have experienced?’) (NRS).13 14

HRQoL was assessed using disease-specific AS Quality of Life (ASQoL) questionnaire (total score range 0–18; a higher score indicates poorer HRQoL)19; generic Short Form-36 Health Survey Version 2 (SF-36v2; acute) questionnaire Physical (PCS) and Mental Component Summary (MCS), and eight domain scores (either norm-based (for change from baseline and correlation analyses) or 0–100 scores (for spydergram illustrations, comparisons vs age-matched and sex-matched US population norms, MCID, numbers needed to treat (NNT) and normative value analyses)); a lower score indicates poorer HRQoL)17; EuroQoL-Five Dimension-Three Level (EQ-5D-3L) health profile mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression domains (scores range 1–3; higher scores indicate poorer HRQoL)20; and Visual Analogue Scale (EQ-VAS; Your Own Health State Today) (range 0–100 mm; lower values indicate poorer health state today).20

Work productivity was evaluated using the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI) questionnaire: spondyloarthritis; scores included percentage of absenteeism (ie, work time missed due to health problem), percentage of presenteeism (ie, impairment while working), percentage of overall work impairment and percentage of activity impairment (higher percentages indicate greater impairment and less productivity).21 Absenteeism, presenteeism and overall work impairment were only assessed in patients who were currently employed.

The FACIT-F, ASQoL, SF-36v2, EQ-5D-3L/EQ-VAS and WPAI instruments, and the NRS for total back pain, nocturnal spinal pain and BASDAI, have been validated in patients with AS.13 17 19 21–24

Changes from baseline to week 48 in total back pain, nocturnal spinal pain, FACIT-F, ASQoL, SF-36v2, EQ-5D-3L dimension scores, EQ-VAS and WPAI were prespecified secondary endpoints. Changes from baseline in BASDAI fatigue (BASDAI question 1) and BASDAI overall spinal pain (BASDAI question 2) were post-hoc endpoints defined after study unblinding.

Changes from baseline in total back pain, ASQoL, SF-36v2 PCS score and FACIT-F total score have been reported previously11; these data are tabulated here for completeness, but not discussed further.

The MCID, defined as the smallest change perceived by patients to be beneficial, can be used to determine whether an improvement due to treatment is also clinically meaningful for the patient population of interest.25–27 The percentages of patients reporting improvements from baseline ≥MCID at week 16 were analysed in: total back pain and nocturnal spinal pain (decrease ≥1)28; FACIT-F total score (increase ≥4.0 points)15 18 29; BASDAI fatigue and BASDAI overall spinal pain (decrease ≥1)30; ASQoL (decrease ≥1.8)29; SF-36v2 PCS and MCS (increases ≥2.5) and domain 0–100 scores (increases ≥5.0)25 29 31; and EQ-VAS (increase ≥10 mm).32

Normative values, based on age-matched and sex-matched data from the general population, can also add clinical context by providing an important reference point against which to quantify patient treatment outcomes25 33 34; scores ≥normative values are indicative that the patient feels and functions as if they do not have arthritis. Here, the percentages of patients reporting scores ≥normative values at week 16 were assessed in FACIT-F total score (≥43.5)33 and SF-36v2 PCS, MCS (≥50), and domain 0–100 scores (normative values are domain-specific).34 The percentages of patients reporting clinically meaningful improvements from baseline and scores ≥normative values at week 16 were post-hoc endpoints defined after study unblinding. No MCID or normative value data were available for WPAI.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were based on two datasets: for PROs up to week 16 (primary analysis dataset, data cut-off 19 December 2019, data snapshot 29 January 2020); all other data are from the final week 48 analysis. Analyses were based on the full analysis set, that is, all patients who were randomised and received ≥1 dose of study drug, using on-treatment data.

Statistical tests were conducted at the two-sided 5% (or equivalently one-sided 2.5%) significance level for tofacitinib versus placebo (up to week 16) or placebo→tofacitinib (up to week 48). Families of efficacy endpoints were tested in hierarchical sequences with a step-down approach to control for global type I error, as described previously.11 Changes from baseline in FACIT-F total, ASQoL and SF-36v2 PCS scores at week 16 were among the global type I error-controlled endpoints, and change from baseline in total back pain at week 16 was a type I error-controlled secondary endpoint; these were adjusted for multiple comparisons. For endpoints not prespecified for type I error control, p values were reported without multiple comparison adjustment.

Up to week 16, changes from baseline in total back pain, nocturnal spinal pain, BASDAI fatigue/overall spinal pain and FACIT-F total/experience/impact domain scores (continuous endpoints) were analysed using a mixed model for repeated measures (MMRM) that included fixed effects of treatment group, visit, treatment-group-by-visit interaction, stratification factor derived from the clinical database, stratification-factor-by-visit interaction, baseline value and baseline-value-by-visit interaction; missing values were not imputed. Changes from baseline at week 16 in ASQoL, SF-36v2 PCS, MCS and domains (norm-based), EQ-5D-3L dimensions, EQ-VAS and WPAI scores were evaluated via an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model, including fixed effects of treatment group, stratification factor derived from the clinical database and baseline value; missing values were not imputed. These analyses included all postbaseline data up to the week 16 cut-off point. After week 16 to week 48, all continuous endpoints were analysed using another MMRM that comprised all postbaseline data through week 48 (the results up to week 16 were discarded).

To enable the assessment of all the HRQoL domains, spydergrams were generated using 0–100 scores for the eight SF-36v2 domains from baseline to weeks 16 and 48 versus age-matched and sex-matched US population norms.

The percentages of patients reporting improvements from baseline ≥MCID and scores ≥normative values at week 16 were compared between tofacitinib and placebo using normal approximation to the difference in proportions, via the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel approach adjusting to the stratification factor (bDMARD-naïve vs TNFi-IR or bDMARD use (non-IR)). Missing response was considered as non-response.

The NNT were calculated at week 16 based on the percentage reporting improvements ≥MCID, defined as the inverse of the difference in proportions of patients receiving tofacitinib versus placebo.

Pearson correlations among related PROs of interest at baseline and week 16, respectively, were calculated. These included: total back pain and nocturnal spinal pain versus SF-36v2 bodily pain domain; FACIT-F total score versus BASDAI fatigue; SF-36v2 physical functioning domain versus Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI; NRS 1–10); and SF-36v2 mental health domain versus EQ-5D-3L anxiety/depression. Correlation coefficient values of ≤0.3, >0.30–≤0.60 and >0.60 were regarded as weakly, moderately and highly correlated, respectively.

Results

Patients

In total, 134 patients were randomised to receive tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily, of whom 133 were treated; 136 patients were randomised to the placebo→tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily arm and all were treated. In the tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily and placebo→tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily arms, respectively, 129 and 131 patients completed the double-blind phase (week 16), and 118 and 122 patients completed the open-label phase (week 48).

Baseline patient demographics, published previously,11 were generally similar between treatment arms. Briefly, most patients in the tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily and placebo→tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily arms were male (87.2% and 79.4%, respectively), Caucasian (80.5% and 77.9%) and bDMARD-naïve (76.7% and 77.2%); in the respective groups, for bDMARD-experienced patients (23.3% and 22.8%), the majority were TNFi-IR (21.8% and 22.1%) and a very small proportion of patients had prior bDMARD use without an IR (1.5% and 0.7%). In the tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily and placebo→tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily arms, respectively, mean patient age was 42.2 and 40.0 years and mean disease duration since symptoms was 14.2 and 12.9 years. Baseline PROs were similar between the tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily and placebo→tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily arms (table 1).

Table 1.

Change from baseline to weeks 16 and 48 for PROs

| PRO | Baseline, mean (SD) [N1] (range) |

Week 16, LS mean ∆ (SE) [N1] | Week 48, LS mean ∆ (SE) [N1] | |||

| Tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily (N=133) |

Placebo (N=136) |

Tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily (N=133) |

Placebo (N=136) |

Tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily (N=133) |

Placebo→ tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily (N=136) |

|

| Pain | ||||||

| Total back pain (NRS 0–10)‡,§ | 6.9 (1.5) (1–10) | 6.9 (1.6) (2–10) | –2.57 (0.19)*** [129] | –0.96 (0.19) [131] | –3.57 (0.22)* [113] | –2.87 (0.22) [112] |

| Nocturnal spinal pain (NRS 0–10)§ | 6.8 (1.9) (0–10) | 6.8 (1.9) (1–10) | –2.67 (0.20)*** [129] | –0.84 (0.20) [131] | –3.52 (0.23) [112] | –3.01 (0.23) [112] |

|

BASDAI overall spinal pain (Question 2; NRS 0–10)§ |

7.3 (1.7) (2–10) | 7.3 (1.6) (2–10) | –2.85 (0.20)*** [129] | –1.34 (0.20) [131] | –3.79 (0.22)* [113] | –3.07 (0.22) [113] |

| Fatigue | ||||||

| FACIT-F§ | ||||||

| Total score (0–52)¶ | 27.2 (10.7) (4–52) | 27.4 (9.3) (1–46) | 6.54 (0.80)*** [129] | 3.12 (0.79) [131] | 9.54 (0.90) [112] | 7.35 (0.89) [111] |

| Experience domain score (0–20) | 8.9 (4.3) (0–20) | 8.7 (4.0) (0–17) | 2.85 (0.36)*** [129] | 1.29 (0.36) [131] | 4.22 (0.40) [112] | 3.40 (0.40) [111] |

| Impact domain score (0–32) | 18.3 (6.9) (4–32) | 18.8 (5.9) (1–30) | 3.68 (0.49)** [129] | 1.81 (0.49) [131] | 5.32 (0.54)* [112] | 3.95 (0.54) [111] |

| BASDAI fatigue (Question 1; NRS 0–10)§ | 6.8 (1.5) (2–10) | 6.8 (1.7) (2–10) | –2.36 (0.20)*** [129] | –1.08 (0.20) [131] | –3.21 (0.22)* [113] | –2.57 (0.22) [113] |

| HRQoL | ||||||

| ASQoL (0–18)¶ †† | 11.6 (4.7) (0–18) | 11.3 (4.2) (0–18) | –4.03 (0.40)*** [129] | –2.01 (0.41) [130] | –5.97 (0.45)* [112] | –4.70 (0.45) [112] |

| SF-36v2 PCS (norm-based)¶ †† | 33.5 (7.3) (17.9–57.3) | 33.1 (7.0) [135] (14.7–53.7) | 6.69 (0.59)*** [129] | 3.14 (0.59) [130] | 8.81 (0.72) [112] | 7.39 (0.71) [111] |

| SF-36v2 MCS (norm-based)†† | 39.4 (11.1) (14.1–65.3) | 39.8 (12.7) [135] (8.0–64.7) | 3.45 (0.91) [129] | 2.13 (0.92) [130] | 7.07 (0.93) [112] | 6.35 (0.92) [111] |

| SF-36v2 domain scores (norm-based)†† | ||||||

| Physical functioning | 36.2 (9.5) (16.2–57.1) | 36.6 (9.2) [135] (16.2–57.1) | 5.52 (0.67)** [129] | 3.29 (0.67) [130] | 7.80 (0.78) [112] | 6.94 (0.77) [111] |

| Role-physical | 34.1 (9.2) (18.4–56.6) | 34.0 (8.1) [135] (18.4–56.6) | 6.13 (0.74)** [129] | 3.13 (0.75) [130] | 8.66 (0.87) [112] | 7.29 (0.86) [111] |

| Bodily pain | 32.5 (6.4) (19.2–54.2) | 32.2 (6.0) [135] (19.2–50.1) | 7.93 (0.71)*** [129] | 3.47 (0.71) [130] | 11.67 (0.92) [112] | 9.55 (0.91) [111] |

| General health | 31.4 (8.4) (16.8–59.0) | 31.5 (8.2) [135] (16.8–52.9) | 5.00 (0.62)*** [129] | 1.76 (0.62) [130] | 6.31 (0.78) [112] | 5.10 (0.77) [111] |

| Vitality | 40.3 (9.3) (22.0–66.9) | 38.5 (9.2) [135] (22.0–60.9) | 5.34 (0.86) [129] | 3.56 (0.87) [130] | 9.83 (1.00) [112] | 9.28 (0.99) [111] |

| Social functioning | 36.7 (10.5) (13.4–56.4) | 36.9 (10.5) [135] (13.4–56.4) | 5.45 (0.84)** [129] | 2.49 (0.84) [130] | 8.16 (0.92) [112] | 6.77 (0.92) [111] |

| Role-emotional | 35.2 (12.3) (10.2–55.7) | 36.3 (13.1) [135] (10.2–55.7) | 4.13 (1.02) [129] | 2.05 (1.02) [130] | 7.17 (1.00) [112] | 6.32 (0.99) [111] |

| Mental health | 38.7 (11.2) (8.0–63.4) | 39.5 (12.3) [135] (8.0–63.4) | 3.57 (0.89) [129] | 2.49 (0.89) [130] | 7.10 (0.96) [112] | 6.45 (0.95) [111] |

| EQ-5D-3L dimension scores (1–3)†† | ||||||

| Mobility | 1.8 (0.4) (1–2) | 1.7 (0.5) (1–2) | –0.23 (0.04)** [129] | –0.06 (0.04) [131] | –0.32 (0.05) [112] | –0.26 (0.05) [112] |

| Self-care | 1.6 (0.5) (1–2) | 1.6 (0.5) (1–2) | –0.21 (0.04) [129] | –0.20 (0.04) [131] | –0.33 (0.05) [112] | –0.33 (0.05) [112] |

| Usual activities | 1.9 (0.4) (1–3) | 1.9 (0.4) (1–3) | –0.18 (0.05) [129] | –0.09 (0.05) [131] | –0.32 (0.05) [112] | –0.34 (0.05) [112] |

| Pain/discomfort | 2.3 (0.5) (2–3) | 2.3 (0.5) (1–3) | –0.30 (0.04)*** [129] | –0.12 (0.04) [131] | –0.37 (0.05) [112] | –0.36 (0.05) [112] |

| Anxiety/depression | 1.7 (0.6) (1–3) | 1.6 (0.6) (1–3) | –0.11 (0.05) [129] | –0.10 (0.05) [131] | –0.17 (0.05) [112] | –0.21 (0.05) [112] |

| EQ-VAS (0–100 mm)†† | 46.9 (18.6) (10.0–95.0) | 47.4 (21.9) [135] (5.0–95.0) | 13.0 (1.84)*** [128] | 2.89 (1.84) [130] | 20.64 (1.88) [112] | 18.00 (1.86) [111] |

| Work productivity | ||||||

| WPAI†† | ||||||

| Activity impairment, % | 56.5 (23.4) (0–90) | 56.0 (21.4) (0–100) | –19.03 (1.97)*** [129] | –5.63 (1.97) [131] | –27.37 (2.34)** [112] | –19.77 (2.31) [112] |

| Absenteeism (work time missed), % | 9.9 (22.4) [81] (0–100) | 11.5 (24.6) [88] (0–100) | –3.65 (2.66) [74] | 0.88 (2.62) [81] | –8.10 (2.14) [61] | –5.79 (2.05) [70] |

| Presenteeism (impairment while working), % | 48.4 (26.3) [79] (0–100) | 49.6 (22.2) [85] (0–90) | –19.83 (2.27)*** [71] | –6.94 (2.30) [77] | –25.35 (2.77) [58] | –23.00 (2.66) [70] |

| Overall work impairment, % | 50.8 (27.4) [79] (0–100) | 53.5 (23.1) [85] (0–100) | –21.49 (2.51)*** [71] | –7.64 (2.56) [76] | –27.63 (3.01) [58] | –23.22 (2.90) [69] |

Mean baseline values and LS mean changes from baseline to weeks 16 and 48 for PROs in patients with AS receiving tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily or placebo→tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily.†

*p≤0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 versus placebo (week 16) or placebo→tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily (week 48). For endpoints not prespecified for type I error control, p values are reported without multiple comparison adjustment.

†Patients receiving placebo advanced to tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily at week 16.

‡Change from baseline at week 16 was a type I error-controlled secondary endpoint.

§Week 16 results are based on MMRM including all postbaseline data to week 16 (data cut-off 19 December 2019; data snapshot 29 January 2020); week 48 results based on another MMRM including all postbaseline data to week 48.

¶Change from baseline at week 16 was a global type I error-controlled endpoint.

††Week 16 results based on ANCOVA including all postbaseline data at week 16 (data cut-off 19 December 2019; data snapshot 29 January 2020); week 48 results based on MMRM including all postbaseline data to week 48.

N, number of patients in full analysis set; N1, number of patients with observation at visit, if different from the full analysis set.

∆, change from baseline; ANCOVA, analysis of covariance; AS, ankylosing spondylitis; ASQoL, Ankylosing Spondylitis Quality of Life; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BID, twice daily; EQ-5D-3L, EuroQol-Five Dimension-Three Level Health Questionnaire; EQ-VAS, EuroQol Visual Analogue Scale; FACIT-F, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue; HRQoL, health-related quality of life; LS, least squares; MCS, Mental Component Summary; MMRM, mixed model for repeated measures; NRS, numerical rating scale; PCS, Physical Component Summary; PRO, patient-reported outcome; SF-36v2, Short Form-36 Health Survey Version 2; WPAI, Work Productivity and Activity Impairment questionnaire.

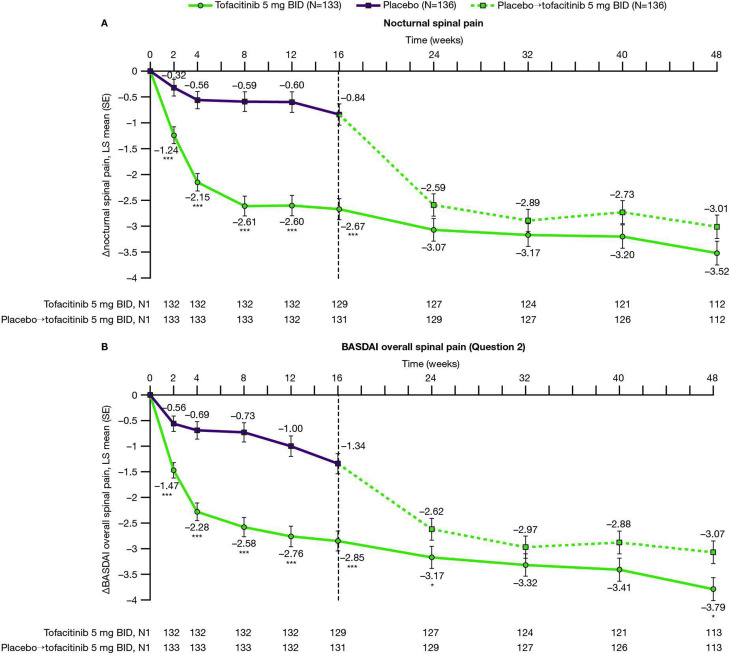

Pain

From week 2 (first postbaseline visit) to week 16, improvements from baseline in nocturnal and BASDAI overall spinal pain scores were greater with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily versus placebo (p<0.001 for each study visit; table 1 and figure 1); improvements generally increased to week 48. In patients who advanced from placebo to tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily at week 16, improvements in pain were reported between weeks 16 and 32, sustained to week 48.

Figure 1.

Changes from baseline to week 48 in (A) nocturnal and (B) BASDAI overall spinal pain. LS mean changes from baseline are shown to week 48 for (A) nocturnal spinal pain and (B) BASDAI overall spinal pain, in patients with AS receiving tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily or placebo→tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily.† Results up to week 16, based on MMRM, include all postbaseline data to week 16 (data cut-off 19 December 2019; data snapshot 29 January 2020); results after week 16 are based on another MMRM including all postbaseline data to week 48 (reporting results after week 16 only). *p≤0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 for comparing tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily versus placebo (up to week 16) or placebo→tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily (up to week 48). P values are reported without adjustment for multiple comparisons. †Patients receiving placebo advanced to tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily at week 16 (dashed line). ∆, change from baseline; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BID, twice daily; LS, least squares; MMRM, mixed model for repeated measures; N, number of patients in full analysis set; N1, number of patients with observation at visit, if different from the full analysis set.

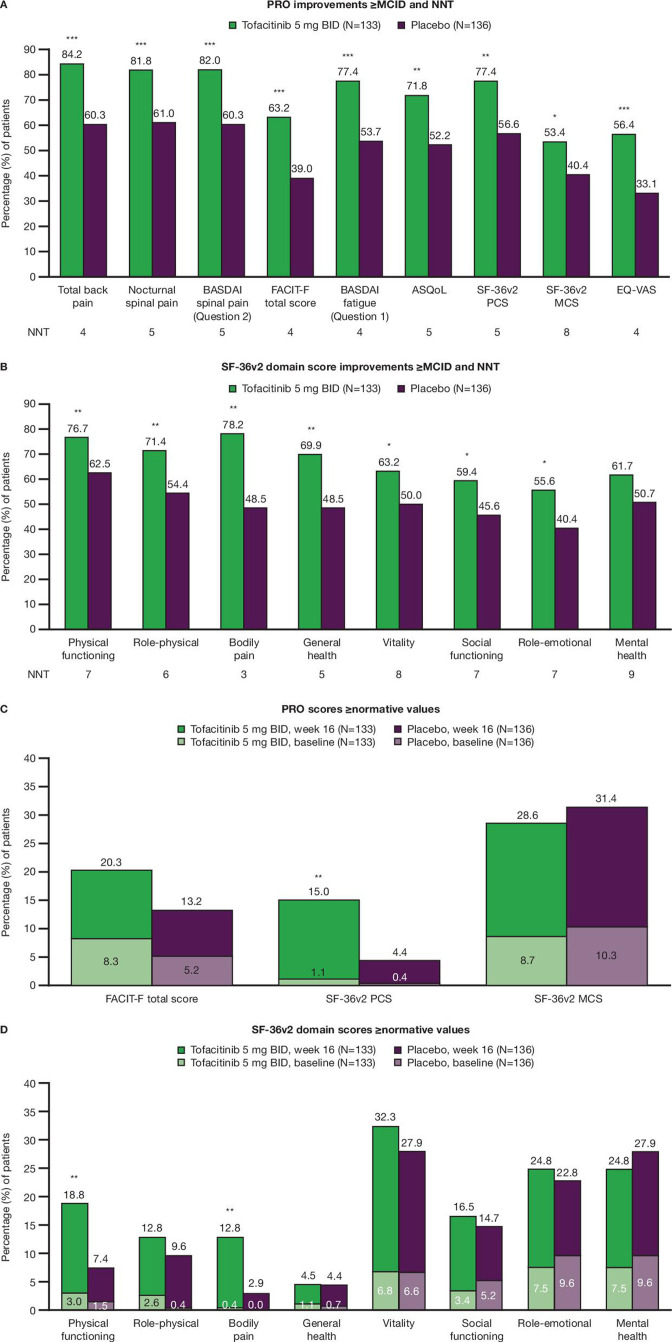

Percentages of patients reporting improvements from baseline ≥MCID at week 16 in total back pain (tofacitinib: 84.2%; placebo: 60.3%), nocturnal spinal pain (tofacitinib: 81.8%; placebo: 61.0%) and BASDAI overall spinal pain (tofacitinib: 82.0%; placebo: 60.3%), were greater with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily versus placebo (p<0.001; figure 2A). Corresponding NNT values for the tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily treatment arm at week 16 were 4, 5 and 5, respectively.

Figure 2.

PRO (A, B) improvements ≥MCID† and NNTs,‡ and (C, D) scores ≥normative values§ at week 16. Data are from the week 16 analysis: data cut-off 19 December 2019; data snapshot 29 January 2020. Missing response was considered as non-response. P values are nominal. *p≤0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 for comparing tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily versus placebo at week 16; Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel approach adjusting for stratification factor (bDMARD-naïve versus TNFi-IR or bDMARD use (non-IR)). †MCID cut-offs: total back pain, nocturnal spinal pain, BASDAI overall spinal pain and BASDAI fatigue, decrease from baseline ≥1; FACIT-F total score, increase from baseline ≥4.0; ASQoL, decrease from baseline ≥1.8; SF-36v2 PCS and MCS scores, increase from baseline ≥2.5; eight SF-36v2 domain 0–100 scores, increase from baseline ≥5.0: EQ-VAS, increase from baseline ≥10 mm. ‡NNT defined as the inverse of the difference in proportions of patients in the tofacitinib arm versus placebo arm reporting ≥MCID. §≥normative values: FACIT-F total score, ≥43.5; SF-36v2 PCS and MCS scores, ≥50; and eight SF-36v2 domain 0–100 scores: physical functioning, ≥88.23; role-physical, ≥87.96; bodily pain, ≥76.81; general health, ≥73.00; vitality, ≥60.55; social functioning, ≥87.66; role-emotional, ≥91.04; mental health, ≥76.70 (the domain-specific cut-offs were calculated as the study protocol’s age-distributed and sex-distributed means matched to the 1998 US population norms on the raw scale with a range of 0–100). AS, ankylosing spondylitis; ASQoL, Ankylosing Spondylitis Quality of Life; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; bDMARD, biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; BID, twice daily; EQ-VAS, EuroQol Visual Analogue Scale; FACIT-F, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue; IR, inadequate response; MCID, minimum clinically important difference; MCS, Mental Component Summary; N, number of patients in full analysis set; NNT, number needed to treat; PCS, Physical Component Summary; PRO, patient-reported outcome; SF-36v2, Short Form-36 Health Survey Version 2; TNFi, tumour necrosis factor inhibitor.

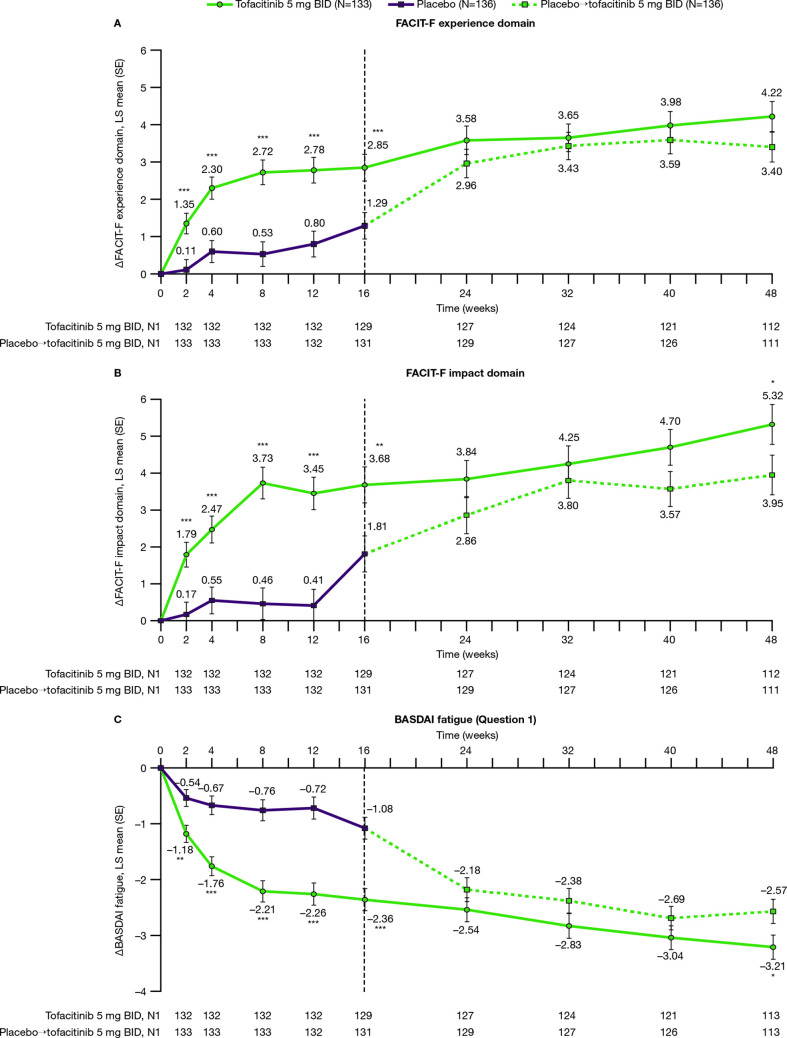

Fatigue

Greater improvements from baseline in FACIT-F total score (published previously11), experience and impact domain scores, and BASDAI fatigue score, were reported from week 2 to week 16, in patients receiving tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily versus placebo (p<0.01 for each study visit; table 1 and figure 3); improvements continued to week 48. Patients receiving placebo who advanced to tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily at week 16 reported improvements in FACIT-F domains and BASDAI fatigue from weeks 16–32, sustained to week 48.

Figure 3.

Changes from baseline to week 48: FACIT-F (A) experience, (B) impact and (C) BASDAI fatigue. LS mean changes from baseline to week 48 for FACIT-F (A) experience, (B) impact and (C) BASDAI fatigue in patients with AS receiving tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily or placebo→tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily.† Results up to week 16, based on MMRM, include all postbaseline data to week 16 (data cut-off 19 December 2019; data snapshot 29 January 2020); results after week 16 are based on another MMRM including all postbaseline data to week 48 (reporting results after week 16 only). *p≤0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 for comparing tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily versus placebo (up to week 16) or placebo→tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily (up to week 48). P values are reported without adjustment for multiple comparisons. †Patients receiving placebo advanced to tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily at week 16 (dashed line). ∆, change from baseline; AS, ankylosing spondylitis; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BID, twice daily; FACIT-F, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue; HRQoL, health-related quality of life; LS, least squares; MMRM, mixed model for repeated measures; N, number of patients in full analysis set; N1, number of patients with observation at visit, if different from the full analysis set.

Percentages of patients reporting improvements ≥MCID at week 16 in FACIT-F total and BASDAI fatigue scores were greater with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily versus placebo (p<0.001; figure 2A), with NNTs of 4. At week 16, percentages of patients reporting FACIT-F scores ≥normative value were numerically higher with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily than placebo (figure 2C).

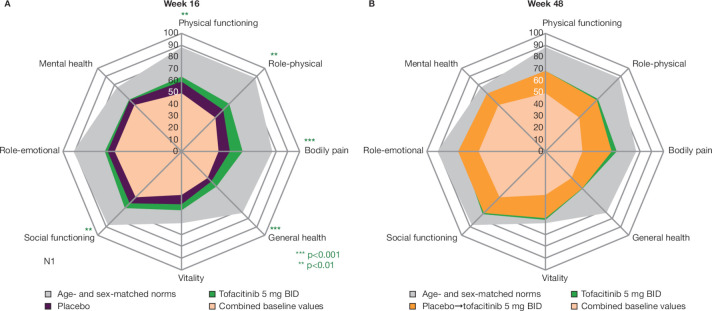

Health-related quality of life

Compared with patients receiving placebo, patients receiving tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily reported greater improvements from baseline at week 16 in ASQoL and SF-36v2 PCS scores (published previously11), and greater improvements in five SF-36v2 domain scores, EQ-5D-3L mobility and pain/discomfort dimensions, and EQ-VAS (all p<0.01; table 1; figure 4A). Improvements with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily were sustained at week 48, with SF-36v2 vitality and mental health domain scores approaching age-matched and sex-matched norms (table 1; figure 4B). Patients receiving placebo who advanced to tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily at week 16 reported improvements in HRQoL PROs at week 48 (table 1).

Figure 4.

Spydergrams of SF-36v2 domains from baseline to (A) week 16 and (B) week 48. Spydergrams of SF-36v2 domain scores from baseline to (A) week 16 (data cut-off 19 December 2019; data snapshot 29 January 2020) and (B) week 48 versus age-matched and sex-matched norms, in patients with AS receiving tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily or placebo→tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily.† Spydergrams were based on sample means generated using domain 0–100 scores. US age-sex norms were matched to the protocol population. Spydergrams are for illustrative purposes only. **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 for tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily versus placebo (week 16) without adjustment for multiple comparisons. P values at week 16 were generated using ANCOVA, including data at week 16 for comparisons with placebo based on LS mean changes from baseline in domain norm-based scores to week 16. †Patients receiving placebo advanced to tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily at week 16. ANCOVA, analysis of covariance; AS, ankylosing spondylitis; BID, twice daily; LS, least squares; SF-36v2, Short Form-36 Health Survey Version 2.

Percentages of patients reporting improvements ≥MCID at week 16 with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily were greater than placebo in ASQoL, SF-36v2 PCS, MCS and seven domain scores, and EQ-VAS (p≤0.05; figure 2A and B). For patients receiving tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily, NNTs at week 16 ranged from 5 to 8 (figure 2A). At week 16, the percentages of patients reporting scores ≥normative values with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily exceeded placebo in SF-36v2 PCS and physical functioning and bodily pain domain scores (p≤0.05; figure 2C and D).

Work productivity

Improvements from baseline in WPAI scores at week 16 were greater in patients treated with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily versus placebo (p<0.001), except for percentage of work time missed due to health problems (table 1); improvements were maintained at week 48. Patients receiving placebo who advanced to tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily at week 16 reported WPAI score improvements at week 48.

Correlation analyses

At week 16: total back pain and nocturnal spinal pain highly correlated with the SF-36v2 bodily pain domain; FACIT-F moderately to highly correlated with BASDAI fatigue; the SF-36v2 physical functioning domain highly correlated with BASFI; and the SF-36v2 mental health domain highly correlated with EQ-5D-3L anxiety/depression (p<0.001; table 2) in both treatment arms.

Table 2.

Correlation analyses for related PRO endpoints of interest at week 16

| Endpoint 1 | Endpoint 2 | N1 | Correlation coefficient value* | |

| Tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily (N=133) | Total back pain | SF-36v2, bodily pain | 129 | –0.76 |

| Nocturnal spinal pain | SF-36v2, bodily pain | 129 | –0.69 | |

| FACIT-F total score | BASDAI fatigue | 128 | –0.66 | |

| SF-36v2, physical functioning | BASFI | 129 | –0.76 | |

| SF-36v2, mental health | EQ-5D-3L anxiety/depression | 129 | –0.69 | |

| Placebo (N=136) | Total back pain | SF-36v2, bodily pain | 131 | –0.66 |

| Nocturnal spinal pain | SF-36v2, bodily pain | 131 | –0.65 | |

| FACIT-F total score | BASDAI fatigue | 130 | –0.60 | |

| SF-36v2, physical functioning | BASFI | 131 | −0.71 | |

| SF-36v2, mental health | EQ-5D-3L anxiety/depression | 131 | −0.64 |

Data are from the week 16 analysis: data cut-off 19 December 2019; data snapshot 29 January 2020.

For SF-36v2 domains, norm-based scores were used.

*All correlations were ***p<0.001, based on Student’s t distribution (N1–2 degree of freedom) to test the null hypothesis of no correlation. Correlation coefficient values of ≤0.3, >0.30–≤0.60 and >0.60 were regarded as weakly, moderately and highly correlated, respectively.

BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BASFI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index; EQ-5D-3L, EuroQol-Five Dimension-Three Level Health Questionnaire; FACIT-F, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue; N, number of patients in full analysis set; N1, number of patients with observation in both PRO endpoints for calculating the correlation; PRO, patient-reported outcome; SF-36v2, Short Form-36 Health Survey Version 2.

Discussion

The goal of treatment of chronic disease, such as AS, is to improve the patient’s overall health and their quality of life. PROs provide a valuable and quantifiable measure of the impact that these diseases and their treatments have on patients’ daily lives. The importance of PROs in the management of AS is highlighted by their inclusion as disease-monitoring measures in current treatment guidelines.5 The ASAS and Outcome Measures in Rheumatology international consensus efforts have identified disease activity, pain, morning stiffness, fatigue, physical function, overall functioning and health, and adverse events, including death, as core domains for patients with AS, and spinal mobility, sleep, and work and employment, as optional domains, to be measured in all trials.35

In this phase III RCT in patients with active AS, improvements in pain, fatigue, HRQoL and work productivity were greater with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily versus placebo at week 16. PRO improvements in pain and fatigue with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily were reported as early as week 2 (first postbaseline visit), consistent with the rapid clinical responses reported previously.11 Improvements in PROs with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily were maintained or further increased to week 48. It should be noted that although improvements in work productivity were reported with tofacitinib at week 16, there was no field in the questionnaire for patients to indicate whether they were working outside the home. Furthermore, the placebo→tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily arm exhibited rapid improvements in pain and fatigue after the switch from placebo to tofacitinib at week 16. It can be noted that both treatment arms continued to exhibit improvement trends, which may explain the numerical differences at week 48.

At week 16, the percentages of patients reporting improvements from baseline ≥MCID were greater with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily versus placebo across a range of PROs, with NNTs at week 16 that were ≤10 and considered to be clinically meaningful.36 Although generally low, these NNTs do suggest that, in this selective population of patients with AS and high inflammatory disease activity, likely other factors contribute to PROs (such as pain and fatigue). Compared with placebo, the percentages of patients reporting PRO scores ≥normative values at week 16 were greater with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily in SF-36v2 PCS and physical functioning and bodily pain domain scores, indicating that patients receiving tofacitinib were more likely to feel improvements within the parameters of these patient measures. Accordingly, in patients receiving tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily, the spydergrams illustrate that some SF-36v2 domain scores approached age-matched and sex-matched norms at week 48.

In a survey of 592 patients with rheumatic diseases, including AS, normalising HRQoL was reported to be the most important treatment outcome to patients.37 This highlights the value of these current findings. Furthermore, our results are encouraging as higher patient-reported pain has been reported in AS (and psoriatic arthritis) when compared with rheumatoid arthritis, another inflammatory rheumatic disease.38 Although not investigated in this study, a prior descriptive analysis indicated that tofacitinib may have an effect on residual pain in patients with PsA with controlled inflammation.39

Improvements in PROs have also been reported in patients with AS treated with other Janus kinase inhibitors, namely upadacitinib and filgotinib, in RCTs.40 41 Compared with placebo in phase II/III SELECT-AXIS-1 trial, 14 weeks of treatment with upadacitinib 15 mg once daily was associated with improvements in function and HRQoL (including BASFI, ASQoL and ASAS Health Index).41 Similarly, in the phase II TORTUGA trial, improvements in function, HRQoL and disease activity (as per BASFI, ASQoL, SF-36 PCS, BASDAI and Patient Global Assessment of Disease Activity) were reported with filgotinib 200 mg once daily versus placebo after 12 weeks of therapy.40

PROs have also been shown to improve in patients with AS being treated with interleukin-17 inhibitors, including secukinumab and ixekizumab, both approved for the management of AS. In the phase III MEASURE 1 RCT, patients receiving secukinumab (loading dose followed by 150 mg or 75 mg every 4 weeks) reported improved PROs versus placebo at week 16, including function, HRQoL, disease activity and fatigue,29 42 which were maintained to week 52,29 with some (BASDAI, BASFI and SF-36 PCS) sustained over 4 years of therapy.43 Similar PRO improvements were also seen in the similarly designed MEASURE 2 trial.42 44 Additionally, PRO improvements with secukinumab treatment were reported in a pooled analysis from patients with AS enrolled in the MEASURE 1–4 trials.45 Likewise, in two phase III RCTs (COAST-V and COAST-W), ixekizumab therapy was associated with sustained improvements in fatigue, spinal pain, HRQoL and physical function over 52 weeks.46–48

Various limitations require consideration when interpreting the findings of the current trial. These include the relatively small study population (although results are robust), placebo comparisons being limited to the 16-week, double-blind portion (although the ethics of limiting placebo exposure is well recognised49), and follow-up being relatively short to assess the long-term impact of tofacitinib treatment. In addition, some analyses (MCID, normative values, NNT, BASDAI fatigue and BASDAI overall spinal pain) were conducted post-hoc, and the ASAS Health Index (a self-reported questionnaire that measures functioning and health across 17 aspects of health and 9 environmental factors50) was not included as an HRQoL measure in this study. Furthermore, the magnitude of effect for tofacitinib appeared greater for the FACIT-F impact domain in this study than for the other measures of fatigue, likely due to the scoring varying between measures. More items of the FACIT-F are included in the impact domain (eight items) compared with the experience domain (five items).18

In patients with active AS, treatment with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily was associated with clinically meaningful improvements versus placebo up to week 16, across a wide range of PROs, including pain, fatigue, HRQoL and work productivity. Improvements with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily were maintained at week 48 or continued to increase up to week 48.

Acknowledgments

Some data reported in this manuscript were previously presented at EULAR 2021. The authors would like to thank the patients, investigators and study teams involved in the study. This study was sponsored by Pfizer Inc. Medical writing support, under the guidance of the authors, was provided by Emma Mitchell, PhD, CMC Connect, McCann Health Medical Communications and was funded by Pfizer Inc, New York, New York, USA in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines (Ann Intern Med 2015;163:461–4).

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors had access to the data reported in this manuscript, contributed to the interpretation of the data, critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content, provided final approval of the version submitted for publication, and accept accountability for the accuracy and integrity of the work. LW, JCC, CW, JW, OD, LF and VS are responsible for the study conception or design. JC-CW, LW, DF, CW and JW are responsible for the acquisition of data. VN-C, JC-CW, VDB, LW, DF, JCC, CW, JW, OD, LF and VS are responsible for the analysis of data.

Funding: This study was sponsored by Pfizer Inc.

Competing interests: VN-C has received research/grant support from AbbVie and Novartis, and is a member of the speakers’ bureaus for AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Moonlake, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer Inc, and UCB. JC-CW has received research/grant support from AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer Inc, and UCB, is a consultant for Eli Lilly, Novartis, and Pfizer Inc, and is a member of the speakers’ bureaus for Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, and Pfizer Inc. FVdB has received consultancy and/or speaker fees from AbbVie, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Galapagos, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer Inc, and UCB. MM has received research/grant support from AbbVie and UCB, and has received consultancy fees from AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer Inc, and UCB. VS has received consultancy fees from AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celltrion, Eli Lilly, Genentech/Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer Inc, Regeneron, Samsung, Sandoz, Sanofi, and UCB. LW, DF, JCC, CW, JW, OD, and LF are employees and shareholders of Pfizer Inc.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Upon request, and subject to review, Pfizer will provide the data that support the findings of this study. Subject to certain criteria, conditions and exceptions, Pfizer may also provide access to the related individual de-identified participant data. See https://www.pfizer.com/science/clinical-trials/trial-data-and-results for more information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and this trial was conducted in accordance with the International Council for Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines, local regulatory requirements and the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Patients provided written informed consent, and the study protocol was approved by an Institutional Review Board or Independent Ethics Committee at each study site.

References

- 1.Bohn R, Cooney M, Deodhar A, et al. Incidence and prevalence of axial spondyloarthritis: methodologic challenges and gaps in the literature. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2018;36:263–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sieper J, Braun J, Rudwaleit M, et al. Ankylosing spondylitis: an overview. Ann Rheum Dis 2002;61 Suppl 3:8iii–18. 10.1136/ard.61.suppl_3.iii8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schneeberger EE, Marengo MF, Dal Pra F, et al. Fatigue assessment and its impact in the quality of life of patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Rheumatol 2015;34:497–501. 10.1007/s10067-014-2682-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nikiphorou E, Ramiro S. Work disability in axial spondyloarthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2020;22:55. 10.1007/s11926-020-00932-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van der Heijde D, Ramiro S, Landewé R, et al. 2016 update of the ASAS-EULAR management recommendations for axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:978–91. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ward MM, Deodhar A, Gensler LS. 2019 Update of the American College of Rheumatology/Spondylitis association of America/Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network recommendations for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis and nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2019;71:1599–1613. 10.1002/art.41042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tam LS, Wei JC-C, Aggarwal A, et al. 2018 APLAR axial spondyloarthritis treatment recommendations. Int J Rheum Dis 2019;22:340–56. 10.1111/1756-185X.13510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tahir H. Therapies in ankylosing spondylitis-from clinical trials to clinical practice. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2018;57:vi23–8. 10.1093/rheumatology/key152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dubash S, McGonagle D, Marzo-Ortega H. New advances in the understanding and treatment of axial spondyloarthritis: from chance to choice. Ther Adv Chronic Dis 2018;9:77–87. 10.1177/2040622317743486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van der Heijde D, Deodhar A, Wei JC, et al. Tofacitinib in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a phase II, 16-week, randomised, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:1340–7. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deodhar A, Sliwinska-Stanczyk P, Xu H, et al. Tofacitinib for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis: a phase III, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Ann Rheum Dis 2021;80:1004–13. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-219601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van der Heijde D, Dougados M, Davis J, et al. Assessment in Ankylosing Spondylitis International Working Group/Spondylitis Association of America recommendations for conducting clinical trials in ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:386–94. 10.1002/art.20790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garrett S, Jenkinson T, Kennedy LG, et al. A new approach to defining disease status in ankylosing spondylitis: the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index. J Rheumatol 1994;21:2286–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Ankylosing Spondylitis Society (NASS) . Ankylosing spondylitis (axial spondyloarthritis) (AS) - the Bath Indices, 2016. Available: https://nass.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Bath-Indices.pdf [Accessed 09 Aug 2021].

- 15.Cella D, Yount S, Sorensen M, et al. Validation of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy Fatigue Scale relative to other instrumentation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2005;32:811–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chandran V, Bhella S, Schentag C, et al. Functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-fatigue scale is valid in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:936–9. 10.1136/ard.2006.065763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Revicki DA, Rentz AM, Luo MP, et al. Psychometric characteristics of the short form 36 health survey and functional assessment of chronic illness Therapy-Fatigue subscale for patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2011;9:36. 10.1186/1477-7525-9-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cella D, Wilson H, Shalhoub H, et al. Content validity and psychometric evaluation of Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue in patients with psoriatic arthritis. J Patient Rep Outcomes 2019;3:30. 10.1186/s41687-019-0115-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doward LC, Spoorenberg A, Cook SA, et al. Development of the ASQoL: a quality of life instrument specific to ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2003;62:20–6. 10.1136/ard.62.1.20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.EuroQol Research Foundation . EQ-5D-3L user guide, 2018. Available: https://euroqol.org/publications/user-guides [Accessed 10 May 2021].

- 21.Reilly MC, Gooch KL, Wong RL, et al. Validity, reliability and responsiveness of the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment questionnaire in ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010;49:812–9. 10.1093/rheumatology/kep457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cella D, Lenderking W, Chongpinitchai P, et al. OP0239 Psychometric evaluation of Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis [abstract]. Ann Rheum Dis 2021;80:146–7. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-eular.62 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsang HHL, Cheung JPY, Wong CKH, et al. Psychometric validation of the EuroQoL 5-dimension (EQ-5D) questionnaire in patients with spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 2019;21:41. 10.1186/s13075-019-1826-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Tubergen A, Black PM, Coteur G. Are patient-reported outcome instruments for ankylosing spondylitis fit for purpose for the axial spondyloarthritis patient? A qualitative and psychometric analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2015;54:1842–51. 10.1093/rheumatology/kev125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strand V, Boers M, Idzerda L, et al. It's good to feel better but it's better to feel good and even better to feel good as soon as possible for as long as possible. Response criteria and the importance of change at OMERACT 10. J Rheumatol 2011;38:1720–7. 10.3899/jrheum.110392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beaton DE, Boers M, Wells GA. Many faces of the minimal clinically important difference (MCID): a literature review and directions for future research. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2002;14:109–14. 10.1097/00002281-200203000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maltenfort M, Díaz-Ledezma C. Statistics in brief: minimum clinically important difference-availability of reliable estimates. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2017;475:933–46. 10.1007/s11999-016-5204-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salaffi F, Stancati A, Silvestri CA, et al. Minimal clinically important changes in chronic musculoskeletal pain intensity measured on a numerical rating scale. Eur J Pain 2004;8:283–91. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2003.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deodhar AA, Dougados M, Baeten DL, et al. Effect of secukinumab on patient-reported outcomes in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis: a phase III randomized trial (MEASURE 1). Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68:2901–10. 10.1002/art.39805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pavy S, Brophy S, Calin A. Establishment of the minimum clinically important difference for the bath ankylosing spondylitis indices: a prospective study. J Rheumatol 2005;32:80–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strand V, de Vlam K, Covarrubias-Cobos JA, et al. Effect of tofacitinib on patient-reported outcomes in patients with active psoriatic arthritis and an inadequate response to tumour necrosis factor inhibitors in the phase III, randomised controlled trial: OPAL Beyond. RMD Open 2019;5:e000808. 10.1136/rmdopen-2018-000808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coates LC, Orbai A-M, Morita A, et al. Achieving minimal disease activity in psoriatic arthritis predicts meaningful improvements in patients’ health-related quality of life and productivity. BMC Rheumatol 2018;2:24. 10.1186/s41927-018-0030-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Montan I, Löwe B, Cella D, et al. General population norms for the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT)-Fatigue scale. Value Health 2018;21:1313–21. 10.1016/j.jval.2018.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maglinte GA, Hays RD, Kaplan RM. US general population norms for telephone administration of the SF-36v2. J Clin Epidemiol 2012;65:497–502. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Navarro-Compán V, Boel A, Boonen A, et al. The ASAS-OMERACT core domain set for axial spondyloarthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2021;51:1342–9. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2021.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Citrome L, Ketter TA. When does a difference make a difference? Interpretation of number needed to treat, number needed to harm, and likelihood to be helped or harmed. Int J Clin Pract 2013;67:407–11. 10.1111/ijcp.12142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.González CM, Carmona L, de Toro J, et al. Perceptions of patients with rheumatic diseases on the impact on daily life and satisfaction with their medications: RHEU-LIFE, a survey to patients treated with subcutaneous biological products. Patient Prefer Adherence 2017;11:1243–52. 10.2147/PPA.S137052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Michelsen B, Fiane R, Diamantopoulos AP, et al. A comparison of disease burden in rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis and axial spondyloarthritis. PLoS One 2015;10:e0123582. 10.1371/journal.pone.0123582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dougados M, van der Heijde D, Bingham C. The effect of tofacitinib on residual pain in patients with psoriatic arthritis [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019;71:1502 https://acrabstracts.org/abstract/the-effect-of-tofacitinib-on-residual-pain-in-patients-with-psoriatic-arthritis/ [Google Scholar]

- 40.van der Heijde D, Baraliakos X, Gensler LS, et al. Efficacy and safety of filgotinib, a selective Janus kinase 1 inhibitor, in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis (TORTUGA): results from a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2018;392:2378–87. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32463-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van der Heijde D, Song I-H, Pangan AL, et al. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis (SELECT-AXIS 1): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2/3 trial. Lancet 2019;394:2108–17. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32534-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baeten D, Sieper J, Braun J, et al. Secukinumab, an interleukin-17A inhibitor, in ankylosing spondylitis. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2534–48. 10.1056/NEJMoa1505066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Braun J, Baraliakos X, Deodhar A, et al. Secukinumab shows sustained efficacy and low structural progression in ankylosing spondylitis: 4-year results from the MEASURE 1 study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2019;58:859–68. 10.1093/rheumatology/key375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marzo-Ortega H, Miceli-Richard C, Gill S. Subcutaneous secukinumab 150 mg provides sustained relief in total and nocturnal back pain, morning stiffness, fatigue, and low disease activity in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis: end-of-study (5-year) data from the MEASURE 2 trial [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 2020;72:0364 https://acrabstracts.org/abstract/subcutaneous-secukinumab-150-mg-provides-sustained-relief-in-total-and-nocturnal-back-pain-morning-stiffness-fatigue-and-low-disease-activity-in-patients-with-active-ankylosing-spondylitis-end-of/ [Google Scholar]

- 45.Deodhar A, Mease PJ, Poddubnyy D, et al. FRI0271 Impact of HLA-B27 status on clinical outcomes among patients with ankylosing spondylitis treated with secukinumab [abstract]. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79:FRI0271. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-eular.1448 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Deodhar A, Mease P, Rahman P. Ixekizumab improves fatigue, pain, and sleep up to 52 weeks in patients with radiographic axial spondyloarthritis [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019;71:1510 https://acrabstracts.org/abstract/ixekizumab-improves-fatigue-pain-and-sleep-up-to-52-weeks-in-patients-with-radiographic-axial-spondyloarthritis/ [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kiltz U, van der Heijde D, Boonen A. Ixekizumab improves self-reported overall functioning and health as measured by the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society Health Index in patients with active radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: 52-week results of two phase 3 randomized trials [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019;71:1547 https://acrabstracts.org/abstract/ixekizumab-improves-self-reported-overall-functioning-and-health-as-measured-by-the-assessment-of-spondyloarthritis-international-society-health-index-in-patients-with-active-radiographic-axial-spondy/ [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wei C-C, Hunter T, Van den Bosch F. Ixekizumab significantly improves patient-reported overall health as measured by SF-36 in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis/radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: 52-week results of two phase 3 trials [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019;71:434 https://acrabstracts.org/abstract/ixekizumab-significantly-improves-patient-reported-overall-health-as-measured-by-sf-36-in-patients-with-active-ankylosing-spondylitis-radiographic-axial-spondyloarthritis-52-week-results-of-two-phase/ [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gupta U, Verma M. Placebo in clinical trials. Perspect Clin Res 2013;4:49–52. 10.4103/2229-3485.106383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society . Description of ASAS Health Index, 2021. Available: https://www.asas-group.org/instruments/asas-health-index/#:~:text=The%20ASAS%20Health%20Index%20has%20been%20developed%20under,non-radiographic%20axial%20SpA%20as%20well%20as%20peripheral%20SpA%29 [Accessed 24 Aug 2021].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Upon request, and subject to review, Pfizer will provide the data that support the findings of this study. Subject to certain criteria, conditions and exceptions, Pfizer may also provide access to the related individual de-identified participant data. See https://www.pfizer.com/science/clinical-trials/trial-data-and-results for more information.