Abstract

Background

Use of traditional medicine (TM) is widespread in sub-Saharan Africa as a treatment option for a wide range of disease. We aimed to describe main characteristics of TM users and estimate the association of TM use with control of hypertension.

Methods

We used data on 2128 hypertensive patients of a cross-sectional study (convenience sampling), who attended cardiology departments of 12 sub-Saharan African countries (Benin, Cameroon, Congo, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Gabon, Guinea, Côte d’Ivoire, Mauritania, Mozambique, Niger, Senegal, Togo). To model association of TM use with odds of uncontrolled, severe and complicated hypertension, we used multivariable mixed logistic regressions, and to model the association with blood pressure (systolic (SBP) and diastolic (DBP)) we used mixed linear models. All models were adjusted for age, sex, wealth, adherence to hypertension conventional treatment and country (random effect).

Results

A total of 512 (24%) participants reported using TM, varying across countries from 10% in the Congo to 48% in Guinea. TM users were more likely to be men, living in rural area, poorly adhere to prescribed medication (frequently due to its cost). Use of TM was associated with a 3.87 (95% CI 1.52 to 6.22)/1.75 (0.34 to 3.16) mm Hg higher SBP/DBP compared with no use; and with greater odds of severe hypertension (OR=1.34; 95% CI 1.04 to 1.74) and of any hypertension complication (OR=1.27; 95% CI 1.01 to 1.60), mainly driven by renal complication (OR=1.57; 95% CI 1.07 to 2.29) after adjustment for measured confounders.

Conclusions

The use of TM was associated with higher blood pressure, more severe hypertension and more complications in Sub-Saharan African countries. The widespread use of TM needs to be acknowledged and worked out to integrate TM safely within the conventional healthcare.

Keywords: Hypertension, Epidemiology

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC.

Few existing studies suggest patients with hypertension who use traditional medicine (TM) are more likely to be older, male, low socioeconomic status and reside in rural area, but results differ according to country and setting.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

In this large cross-sectional study on 12 sub-Saharan African countries, self-reported use of TM in patients with hypertension was common and varied drastically from 10% (Congo) to 48% (Guinea).

TM users were more likely to be male, with poor treatment adherence, and to report missing treatment because of its cost, and to have severe hypertension (OR=1.34; 95% CI 1.04 to 1.74) and complications of hypertension (OR=1.27; 95% CI 1.01 to 1.60).

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE AND/OR POLICY

The widespread use of TM in patients with hypertension needs to be acknowledged and worked out to integrate it safely within the conventional healthcare.

Introduction

Hypertension is extremely common with 1.278 billion people (34% of men, 32% of women) aged 30–79 years worldwide estimated to have hypertension in 2019, with 1 billion of them living in low-income and middle-income countries.1 2 The rise in incidence of hypertension since 1990 has been particularly striking in sub-Saharan Africa, where it is still predominantly undiagnosed (52% of women, 66% of men), uncontrolled and not treated, with only 13% of women and 9% of men estimated to have controlled hypertension in sub-Saharan Africa.2 When uncontrolled, hypertension can have an array of complications, including stroke, ischaemic heart disease, kidney and heart failure.1 3

Use of traditional medicine (TM) is widespread in sub-Saharan Africa as a treatment option for a wide range of disease,4 including for the management of hypertension.5–7 TM encompasses different types of healthcare practices.8 According to a recent systematic review, in sub-Saharan Africa, the most common form is biological-based (use of medicinal herbs and plants, homeopathy), followed by faith-based (prayer, spirituality), and mind–body therapies (eg, massage, meditation).4 There is a growing interest in evaluating the potential beneficial role of TM use in the management of chronic diseases, as it has been recognised as a potential solution in contexts of limited access to essential health services. The WHO has developed a strategy paper with objectives of integrating TM in national healthcare systems, fostering its access and rational use, but also expanding the knowledge base on its safety, efficacy and quality.8

Little is known on the profile of users of TM with hypertension. Studies in patients with hypertension from Nigeria (three studies),9–11 Ghana,12 Ethiopia,13 Uganda14 and South Africa15 16 report a prevalence of use, alone or in combination with ‘modern’ medicine, between 20% and 68% (mean 27%). A synthesis of these studies of modest sample size (the largest being n=500) is that users were more likely to be older, male, low income level, less educated and reside in rural area, although the results differ according to country and setting. More importantly, there has been little work on the actual efficacy of TM in the management and control of hypertension.

We aimed (1) to describe the proportion and characteristics of patients who use TM, and (2) estimate the association between TM use and blood pressure, (BP) and complications of hypertension in a pan-African study.

Methods

Study design

The Evaluation of Hypertension in Sub-Saharan Africa study (EIGHT) is an observational, cross-sectional study conducted in outpatient consultations specialised in hypertension in cardiology departments of 29 medical centres from 17 cities across 12 sub-Saharan African countries between January 2014 and November 2015. The study design and sample size calculation have been described in details elsewhere.17–20 It was designed by a multidisciplinary collaborative team of epidemiologists, cardiologists and pharmacists from Africa and France. Participants gave informed consent.

The sampling strategy was convenience sampling. In each participating hospital, patients with a hypertension diagnosis, aged 18 years or older were eligible to participate. Each patient received an information leaflet about the study. Further, the on-site physician presented and explained the study in the regional language to all patients meeting eligibility criteria and collected patient consent. Those who agreed to participate completed a standard questionnaire while waiting for their appointment. A total of 2198 adult hypertensive patients were enrolled during outpatient consultations, in the cardiology departments of the participating hospitals. The first section of the questionnaire was completed by patients and collected data on demographic factors and medication details including self-reported adherence. The second section was completed by the physician during the consultation and provided data on patient socioeconomic status, treatment prescribed, BP values, complications and cardiovascular risk factors.

Measurements

Seated BP was measured twice by physicians, at least 15 min apart; attention was paid to avoid caffeine and smoking within the 30 min before BP measurement. We took the mean of the two measurements for the description of systolic BP (SBP) and diastolic BP (DBP). Uncontrolled hypertension was defined by an SBP ≥140 mm Hg and/or DBP ≥90 mm Hg on any of the two measurements. Mild (SBP, 140–159 mm Hg OR DBP, 90–99 mm Hg), moderate (SBP, 160–179 mm Hg or DBP, 100–109 mm Hg) and severe hypertension (SBP,≥180 mm Hg or DBP ≥110) mm Hg were defined according to the European Society of Cardiology guidelines.21

TM use was assessed by a simple question ‘Do you ever use traditional medicine as a treatment for your cardiovascular disease?’ with a yes/no answer.

Adherence to prescribed medication(s) was assessed by the eight items Medication Adherence Scale.22 The scale scores from 0 to 8: high adherence was defined as a score of 8, and poor adherence as a score <8. An additional item on the impact of patient financial situation on adherence was included with a yes/no answer: ‘Some medications are expensive. Did you ever skip taking your treatment for financial reasons?’.

The country income was obtained from the World Bank database (http://data.worldbank.org/country) and categorised into low-income and middle-income countries. Individual patient wealth categories were assessed by the physician and classified as low (patients who have difficulties to afford medical consultations), middle (patients who can manage paying medical consultations) and high (no difficulties to pay medical consultations).

Complications of hypertension were assessed in the physician questionnaire by the question ‘If the patient has hypertension, has he/she presented with complications?’ (yes/no). If yes, indicate if mild or severe for the following: Ocular, Renal, Cardiac, Cerebral.

Statistical analysis

We report the proportion of TM use overall and in each country. We describe the main characteristics of the overall study participants according to use of TM, reporting p values of χ2 for categorical variables or t-tests for continuous variables. Based on these univariable descriptive results, we then proceeded to explore the factors associated with TM use, by fitting multivariable mixed logistic regression models with a random effect for country to account for intra and intercountry variability.20 The covariates considered were age, sex, living location (urban, rural), individual patient wealth, country income level, treatment adherence, missing treatment for financial reason, number of treatments prescribed (0, 1, 2, ≥3), severity of hypertension, presence of complications of hypertension (renal, cerebral, cardiac, ocular). After fitting a model including all covariates, we did a ‘backwards’ selection by selecting a limited set of factors that showed stronger associations with TM use, and that did not have more than 5% of missing data.

To answer our second aim, we assessed the association between TM use and BP using mixed linear regression models where SBP and DBP were the outcomes. The association of TM use with uncontrolled hypertension, severe hypertension and presence of hypertension complications were assessed by mixed logistic regression models. All models included the following covariates, as they were associated with uncontrolled hypertension and its complications: age, sex, treatment adherence (high, poor), patient wealth index (low, medium, high) and a random effect for country.

All analyses were performed using R V.4.0.3 (2020-10-10) and the level of significance was set at p<0.05.

Patients and public involvement

It was not possible to involve patients or the public in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of our research.

Results

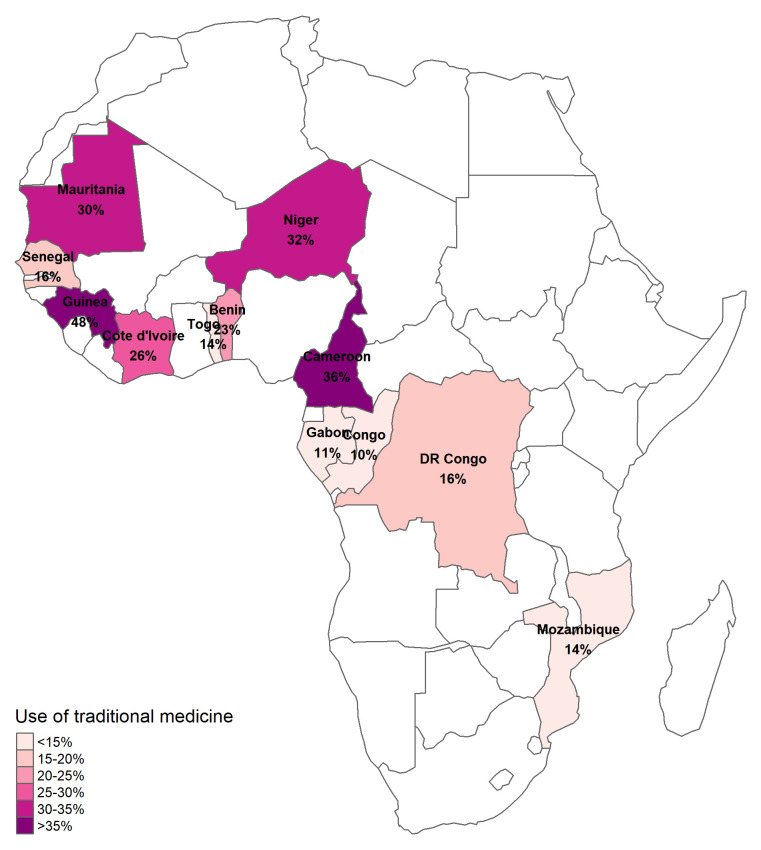

Out of 2198 patients with hypertension included in the EIGHT study, 2128 participants had data on TM use. Of them, 512 (24%) reported using TM, and this percentage varied drastically across countries from 10% in the Congo to 48% in Guinea (figure 1, p value for difference <0.001).

Figure 1.

Proportion of self-reported reported use of traditional medicine in patients with hypertension across the 12 African countries included in the EIGHT study. EIGHT, Evaluation of Hypertension in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Participants characteristics according to use of TM, and unadjusted t-tests and χ2 are presented in table 1. Those reporting using TM were on average slightly older (59±11 years) than non-users (58±12 years, p value for difference=0.05), more likely to be male, live in a rural area, to have poor treatment adherence and to report missing treatment because it is too expensive than those not reporting TM use. No striking difference was observed regarding country level income or individual wealth index, time of diagnostic of hypertension, CVD risk factors and lifestyle (table 1, unadjusted t-tests and χ2). After selection and mutual adjustment (online supplemental figure), TM users were more likely to be male, with poor treatment adherence, reporting missing treatment because it is too expensive, and presenting any complication of hypertension.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with hypertension included in the EIGHT study, according to their use of traditional medicine

| Use of traditional medicine | P value* | Missing N | ||

| No | Yes | |||

| N | 1616 | 512 | ||

| Age (mean (SD)) | 57.99 (11.97) | 59.18 (11.19) | 0.05 | 0 |

| Male sex (n (%)) | 598 (37.0) | 244 (47.7) | <0.001 | 0 |

| Hypertension (n (%)) | 0.05 | 12 | ||

| Controlled | 382 (23.8) | 101 (19.8) | ||

| Mild | 474 (29.5) | 154 (30.3) | ||

| Moderate | 416 (25.9) | 122 (24.0) | ||

| Severe | 335 (20.8) | 132 (25.9) | ||

| Systolic blood pressure (mean (SD)) | 148.07 (23.29) | 152.03 (24.48) | 0.001 | 12 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mean (SD)) | 87.99 (14.05) | 89.32 (14.96) | 0.07 | 15 |

| Time since hypertension diagnostic (n (%)) | 0.41 | 44 | ||

| <1 year | 240 (15.2) | 77 (15.3) | ||

| 1–5 years | 820 (51.9) | 280 (55.7) | ||

| 6–9 years | 231 (14.6) | 65 (12.9) | ||

| >10 years | 290 (18.3) | 81 (16.1) | ||

| Low-income country (n (%)) | 748 (46.3) | 232 (45.3) | 0.74 | 0 |

| Individual wealth index (n (%)) | 0.22 | 52 | ||

| High | 536 (33.8) | 152 (30.9) | ||

| Middle | 769 (48.5) | 261 (53.0) | ||

| Low | 279 (17.6) | 79 (16.1) | ||

| Place of residence (n (%)) | 0.001 | 40 | ||

| Rural | 88 (5.6) | 52 (10.3) | ||

| Semirural | 226 (14.3) | 68 (13.5) | ||

| Urban | 1271 (80.2) | 383 (76.1) | ||

| No of treatments for hypertension (mean (SD)) | 1.95 (0.92) | 1.86 (0.90) | 0.05 | 0 |

| Type of treatment | 0 | |||

| Calcium inhibitor (n (%)) | 910 (58.0) | 261 (53.5) | 0.09 | |

| Diuretic (n (%)) | 878 (56.0) | 253 (51.8) | 0.12 | |

| Converting enzyme inhibitor (n (%)) | 710 (45.3) | 241 (49.4) | 0.12 | |

| Betablocker (n (%)) | 351 (22.4) | 100 (20.5) | 0.42 | |

| Angiotensin II antagonist (n (%)) | 240 (15.3) | 75 (15.4) | 1.00 | |

| Central antihypertensive (n (%)) | 57 (3.6) | 21 (4.3) | 0.59 | |

| Vasodilator (n (%)) | 23 (1.5) | 8 (1.6) | 0.95 | |

| Poor treatment adherence (n (%)) | 1007 (62.3) | 379 (74.0) | <0.001 | 0 |

| Reported missing treatment because of its cost (n (%)) | 381 (24.1) | 168 (33.3) | <0.001 | 40 |

| Number of complications of hypertension (n (%)) | 0.001 | 93 | ||

| 0 | 894 (57.9) | 245 (49.9) | ||

| 1 | 511 (33.1) | 191 (38.9) | ||

| 2 | 119 (7.7) | 39 (7.9) | ||

| 3 or more | 20 (1.3) | 16 (3.3) | ||

| Type of complications (n (%)) | 93 | |||

| Renal | 104 (6.7) | 50 (10.2) | 0.02 | |

| Cardiac | 407 (26.4) | 152 (31.0) | 0.05 | |

| Cerebral | 133 (8.6) | 62 (12.6) | 0.01 | |

| Ocular | 162 (10.5) | 48 (9.8) | 0.71 | |

| Cardiovascular disease risk factors (n (%)) | 545 | |||

| Current tobacco smoking | 56 (4.5) | 21 (6.2) | 0.24 | |

| Diabetes | 208 (16.7) | 69 (20.5) | 0.12 | |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 255 (20.4) | 55 (16.4) | 0.11 | |

| Hypertriglyceridaemia | 60 (4.8) | 23 (6.8) | 0.18 | |

| Obesity | 251 (20.1) | 75 (22.3) | 0.42 | |

| Sedentary lifestyle | 494 (39.6) | 129 (38.4) | 0.73 | |

*P alue is for t-test (continuous) of χ2 (categorical variables).

bmjgh-2021-008138supp001.pdf (39KB, pdf)

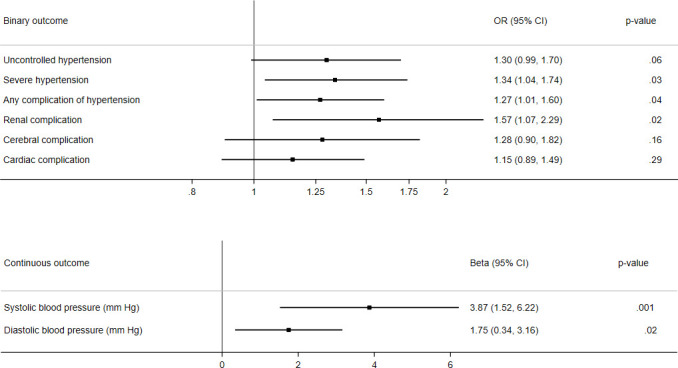

As seen on figure 2, the use of TM was associated with greater odds of uncontrolled hypertension, independent of age, sex, treatment adherence, wealth and country (OR 1.30; 95% CI 0.99 to 1.70), although not statistically significant at the conventional level (p=0.06). The same association was observed with severe hypertension (OR 1.34; 95% CI 1.04 to 1.74), and for any complication of hypertension (cerebral, renal, ocular, cardiac; OR 1.27; 95% CI 1.01 to 1.60), particularly renal complication (OR 1.57; 95% CI 1.07 to 2.29). In multivariable linear regression, use of TM was associated with a 3.87 (95% CI 1.5 to 6.22) mm Hg higher SBP and 1.75 (95% CI 0.34 to 3.16) mm Hg higher DBP compared with no use. Further adjustment for lifestyle and CVD risk factors reduced the sample size due to missing data on these variables, and did not modify the direction or magnitude of the associations between TM and hypertension outcome variables.

Figure 2.

Multivariable associations of use of traditional medicine with hypertension-related outcomes. all estimates are adjusted for age, sex, treatment adherence, patient wealth index (low, medium, high), with a random effect for country. for binary outcomes (top panel), estimates are ORs from multivariable logistic mixed regression models. for continuous outcomes (bottom panel), betas were estimated by multivariable linear mixed regression models.

Discussion

This is the first cross-country study that describes the proportion of TM use, the profile of users, and health status associated with TM in patients with hypertension in 12 sub-Saharan African countries. We observed large differences across countries with proportion lower than 15% in Congo, Gabon or Togo to greater than 35% in Cameroon and Guinea. Factors associated with TM use were male sex, older age, having low treatment adherence and more likely to miss treatment due to expensive price. Moreover, those using TM presented worse markers of severe hypertension and complications of hypertension.

The overall proportion (24%) shows that self-reported use of TM is common in patients with diagnosed hypertension, and matches the literature with a mean prevalence of published studies in sub-Saharan Africa of 27%.4 However, in the study centres in Congo, Gabon, Mozambique, Togo, Senegal and DRC this proportion was lower than the lowest prevalence reported in the literature of 20%. To the best of our knowledge, no data on TM use have been published in hypertensive patients in any of the countries included in our study, making our results novel.

Regarding the sociodemographic factors associated with the use of TM (first objective of our study), some of our results are in line with most published studies, that found that patients with hypertension who are male, older and reside in rural area are more likely to be TM users.9 10 12 13 However, some studies12 13 found that they tended to be of low income level, which was not the case in this study. We found very little evidence of difference in TM use reported by individual wealth or country income. Despite the fact that ‘missing treatment because it is too expensive’ was strongly associated with TM use, as it was in other studies such as in Ghana,23 it appears to not be directly linked to patient’s wealth. Rather, the answer to the question on missing treatment may reflect a perception of the treatment price, attributing a lower priority to its purchase, or the hassle that it represents to get the medicine from the hospital or the pharmacy. Poor treatment adherence was strongly associated with TM use, in line with a South African study that showed that non-compliant hypertensive patients were more likely to seek complementary medicine.15 An implication of this is that, beyond advocating for regulation, accessibility and affordability of drugs for chronic diseases in all the communities, efforts should be made by healthcare professionals to communicate on the importance of treatment adherence to patients, and have open discussion on the use of TM.24

Because hypertension is usually asymptomatic for many years, health seeking is lower and long-term treatments can be perceived as a useless burden if one is apparently in good health. We lacked information on psychosocial and behavioural variables, such as belief, to better understand the reasons of use of TM. Psychosocial variables, such as belief that hypertension is due to supernatural causes, or positive perception of traditional healers, have been shown to be very important determinants of TM use.10 14

The use of TM needs to be recognised, especially in countries where it is common. It has been acknowledged as providing healthcare in the context of limited access to health services, in particular in the rural and most deprived areas in some countries.25 However, the results of our second objective show that TM users presented worse hypertension profile and complications, independent of age, sex, country, wealth and treatment adherence. The cross-sectional design of our study is a great limitation that does not allow to disentangle the temporal sequence, therefore no causal conclusion can be made. One explanation may be that people who use TM wait longer before seeking conventional treatment, therefore, presenting with complicated forms of hypertension with worse prognosis. However, the duration of hypertension since its diagnosis did not differ between the patients who used and did not use TM. Our study suffers from a referral bias since it was conducted in cardiology departments of major cities in sub-Saharan countries. Indeed, people prefer TM over conventional care because of lengthy procedures and fear of being diagnosed of a serious disease4, so TM users are likely under-represented in our study. On the contrary, those people who manage to control hypertension with TM may simply never go to a cardiology consultation and therefore would not be included in this study. Another explanation can be that using TM gives a false sense of protection, in particular faith/spiritual based medicine, and that people present to the consultation with worse symptoms. Finally, another likely phenomenon that occurs is that people who have worse symptoms and complications try also using TM as a complement of modern treatment, which they deem insufficient.

Therefore, despite the multiple potential interpretations of our results, the worse health profile of patients with hypertension using TM warrants caution when promoting TM use. It is fundamental to promote an open dialogue about TM between patients and physicians: destigmatise the reporting of the use of TM to the physician, discuss possible interactions with treatment, differentiating spiritual-based from plant-based for which some research may suggest mild efficacy.26

Our study presents strengths including its large sample size (over 2000 patients), the multicentre design from 29 medical centres in 17 cities from 12 countries, the strong and structured collaborative multidisciplinary network and active involvement of local cardiologists in the design and data collection and analysis. However, we need to acknowledge several important limitations. First, the cross-sectional design does not allow to draw causal conclusions on the effect of TM on hypertension control. The negative association that we observe is not likely to represent an intrinsic deleterious effect of TM, but rather the use of TM may be a consequence of various factors that led to a worse hypertension profile. Second, our main exposure of interest, use of TM, was assessed with only one self-reported question. It did not include information on exposure duration of TM, whether it was prior or posterior to the diagnostic of hypertension. Moreover, it would have been very useful to have detail on the type of TM (medicinal herbs, potions, prayers, incantations, meditation, other modalities) and on drivers of use of TM such as low cost, greater accessibility, trust and confidence in traditional healers. Moreover, it has been shown that it is common for patients to hide use of TM to their healthcare providers,4 and we did not have this data available. This means that because the study questionnaire was filled when visiting the hospital, self-report of TM use may have been underreported and the prevalence of use is likely underestimated.

To conclude, we find that on average one-quarter of patients with hypertension in 12 sub-Saharan countries report using TM, with large variations across countries. Users were more likely to have overall worse markers of BP and associated complications of hypertension. The widespread use of TM needs to be acknowledged and worked out to integrate TM safely within the conventional healthcare.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patients and the members of the African Research Network for their participation in this research.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Sanne Peters

Twitter: @DrLassale

Contributors: XJ is the guarantor of this work. XJ, IBD and MAn designed the study and take responsibility for integrity of the data and accuracy of data analysis; Responsible for data collection: IBD, KEK, IAT, DMB, BF, MH, MSI, AK, SGK-K, SK, CKK, LMK, CN, EL, JLT, JBM, ASA, RN, AD, JMD. CL conducted the data analysis; CL, XJ, MAn, MA and BG interpreted the results; CL and MAn drafted the manuscript; All authors critically revised and approved the final manuscript. In online supplemental appendix, we present a reflexivity statement on international partnership between high-income and low-income and/or middle-income countries.

Funding: Camille Lassale is supported by a fellowship from 'La Caixa' Foundation (ID 100010434) and from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No 847 648. The fellowship code is LCF/BQ/PR21/11840003. Bamba Gaye is supported by a Lefoulon Delalande grant and a Fondation Bettencourt Schueller Price. The EIGHT study is supported by INSERM (Institut national de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale), AP-HP (Assistance Publique Hôpitaux de Paris), Paris Descartes University.

Disclaimer: The funding bodies had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; and in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Map disclaimer: The inclusion of any map (including the depiction of any boundaries therein), or of any geographic or locational reference, does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ concerning the legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of its authorities. Any such expression remains solely that of the relevant source and is not endorsed by BMJ. Maps are provided without any warranty of any kind, either express or implied.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. All relevant data are within the paper and its supporting information files. Data are available on reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained directly from patient(s)

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Ile-de-France III Ethics Committee (No. 2014-A00710-47) and was declared to the National Commission of Informatics (No. 1762715).

References

- 1.Zhou B, Perel P, Mensah GA, et al. Global epidemiology, health burden and effective interventions for elevated blood pressure and hypertension. Nat Rev Cardiol 2021;18:785–802. 10.1038/s41569-021-00559-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC) . Worldwide trends in hypertension prevalence and progress in treatment and control from 1990 to 2019: a pooled analysis of 1201 population-representative studies with 104 million participants. Lancet 2021;398:957–80. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01330-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forouzanfar MH, Liu P, Roth GA, et al. Global burden of hypertension and systolic blood pressure of at least 110 to 115 MM Hg, 1990-2015. JAMA 2017;317:165. 10.1001/jama.2016.19043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.James PB, Wardle J, Steel A, et al. Traditional, complementary and alternative medicine use in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. BMJ Glob Health 2018;3:e000895. 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adeoye RI, Joel EB, Igunnu A, et al. A review of some common African spices with antihypertensive potential. J Food Biochem 2022;46:e14003. 10.1111/jfbc.14003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balogun FO, Ashafa AOT. A review of plants used in South African traditional medicine for the management and treatment of hypertension. Planta Med 2019;85:312–34. 10.1055/a-0801-8771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liwa A, Roediger R, Jaka H, et al. Herbal and alternative medicine use in Tanzanian adults admitted with Hypertension-Related diseases: a mixed-methods study. Int J Hypertens 2017;2017:1–9. 10.1155/2017/5692572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization . Who traditional medicine strategy: 2014-2023. World Health Organization, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olisa NS, Oyelola FT. Evaluation of use of herbal medicines among ambulatory hypertensive patients attending a secondary health care facility in Nigeria. Int J Pharm Pract 2010;17:101–5. 10.1211/ijpp.17.02.0005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Osamor PE, Owumi BE. Complementary and alternative medicine in the management of hypertension in an urban Nigerian community. BMC Complement Altern Med 2010;10:36. 10.1186/1472-6882-10-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amira OC, Okubadejo NU. Frequency of complementary and alternative medicine utilization in hypertensive patients attending an urban tertiary care centre in Nigeria. BMC Complement Altern Med 2007;7:1–5. 10.1186/1472-6882-7-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kretchy IA, Owusu-Daaku F, Danquah S. Patterns and determinants of the use of complementary and alternative medicine: a cross-sectional study of hypertensive patients in Ghana. BMC Complement Altern Med 2014;14:1–7. 10.1186/1472-6882-14-44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Asfaw Erku D, Basazn Mekuria A. Prevalence and correlates of complementary and alternative medicine use among hypertensive patients in Gondar town, Ethiopia. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2016;2016:1–7. 10.1155/2016/6987636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nuwaha F, Musinguzi G. Use of alternative medicine for hypertension in Buikwe and Mukono districts of Uganda: a cross sectional study. BMC Complement Altern Med 2013;13:1–6. 10.1186/1472-6882-13-301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peltzer K. Health beliefs and prescription medication compliance among diagnosed hypertension clinic attenders in a rural South African Hospital. Curationis 2004;27:15–23. 10.4102/curationis.v27i3.994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hughes GD, Aboyade OM, Clark BL, et al. The prevalence of traditional herbal medicine use among hypertensives living in South African communities. BMC Complement Altern Med 2013;13. 10.1186/1472-6882-13-38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cavagna P, Stéphane Ikama M, Euloge Kramoh K, et al. Antihypertensive strategies and hypertension control in sub-Saharan Africa. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2021;28:e21–5. 10.1177/2047487320937492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Macquart de Terline D, Kane A, Kramoh KE, et al. Factors associated with poor adherence to medication among hypertensive patients in twelve low and middle income sub-Saharan countries. PLoS One 2019;14:e0219266. 10.1371/journal.pone.0219266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Macquart de Terline D, Kramoh KE, Bara Diop I, et al. Poor adherence to medication and salt restriction as a barrier to reaching blood pressure control in patients with hypertension: cross-sectional study from 12 sub-Saharan countries. Arch Cardiovasc Dis 2020;113:433–42. 10.1016/j.acvd.2019.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Antignac M, Diop IB, Macquart de Terline D, et al. Socioeconomic status and hypertension control in sub-Saharan Africa: the Multination eight study (evaluation of hypertension in sub-Saharan Africa). Hypertension 2018;71:577–84. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.10512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J 2018;39:3021–104. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Korb-Savoldelli V, Gillaizeau F, Pouchot J, et al. Validation of a French version of the 8-item Morisky medication adherence scale in hypertensive adults. J Clin Hypertens 2012;14:429–34. 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2012.00634.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kretchy IA, Owusu-Daaku F, Danquah S. Patterns and determinants of the use of complementary and alternative medicine: a cross-sectional study of hypertensive patients in Ghana. BMC Complement Altern Med 2014;14:44. 10.1186/1472-6882-14-44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cavagna P, Kramoh KE, Sidy Ali A, et al. The importance of considering cultural and environmental elements in an interventional model of care to fight hypertension in Africa. J Clin Hypertens 2021;23:1269–70. 10.1111/jch.14252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.The African Health Monitor - Special Issue: African Traditional Medicine - World | ReliefWeb. Available: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/african-health-monitor-special-issue-african-traditional-medicine [Accessed 25 May 2021].

- 26.Azizah N, Halimah E, Puspitasari IM, et al. Simultaneous use of herbal medicines and antihypertensive drugs among hypertensive patients in the community: a review. J Multidiscip Healthc 2021;14:259–70. 10.2147/JMDH.S289156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjgh-2021-008138supp001.pdf (39KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request. All relevant data are within the paper and its supporting information files. Data are available on reasonable request.