Abstract

Two different Cd2+ uptake systems were identified in Lactobacillus plantarum. One is a high-affinity, high-velocity Mn2+ uptake system which also takes up Cd2+ and is induced by Mn2+ starvation. The calculated Km and Vmax are 0.26 μM and 3.6 μmol g of dry cell−1 min−1, respectively. Unlike Mn2+ uptake, which is facilitated by citrate and related tricarboxylic acids, Cd2+ uptake is weakly inhibited by citrate. Cd2+ and Mn2+ are competitive inhibitors of each other, and the affinity of the system for Cd2+ is higher than that for Mn2+. The other Cd2+ uptake system is expressed in Mn2+-sufficient cells, and no Km can be calculated for it because uptake is nonsaturable. Mn2+ does not compete for transport through this system, nor does any other tested cation, i.e., Zn2+, Cu2+, Co2+, Mg2+, Ca2+, Fe2+, or Ni2+. Both systems require energy, since uncouplers completely inhibit their activities. Two Mn2+-dependent L. plantarum mutants were isolated by chemical mutagenesis and ampicillin enrichment. They required more than 5,000 times as much Mn2+ for growth as the parental strain. Mn2+ starvation-induced Cd2+ uptake in both mutants was less than 5% the wild-type rate. The low level of long-term Mn2+ or Cd2+ accumulation by the mutant strains also shows that the mutations eliminate the high-affinity Mn2+ and Cd2+ uptake system.

It is well established that heavy metals, such as Cd2+, are toxic for microorganisms, although the underlying mechanism is not clear. In most cases, heavy metals must enter the cells to be toxic (21, 23). They can be accumulated by cells via uptake systems responsible for essential cations. In Escherichia coli, Cd2+ enters cells via a Zn2+ transport system (16). In gram-positive bacteria, such as Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus, or Lactobacillus plantarum, Cd2+ competes for transport with Mn2+ (5, 8, 15, 22). Of all the reported Mn2+ and Cd2+ uptake systems, the one in L. plantarum appears to have the highest affinity. L. plantarum contains high concentrations of Mn2+ (30 to 35 mM), which acts as a scavenger of toxic oxygen species, such as superoxide radical anions (O2−), replacing the micromolar level of superoxide dismutase which functions in other oxygen-tolerant organisms (1–4). A highly active Mn2+ uptake system has been identified in L. plantarum; this uptake system maintains its high Mn2+ content (5). This Mn2+ uptake system also takes up Cd2+. Several Cd2+-resistant mutants of B. subtilis have been isolated (8, 15, 17). Surprisingly, only Cd2+ transport was reduced in these mutants; their Mn2+ transport was unaffected.

In an attempt to understand Cd2+ uptake by bacterial Mn2+ transport systems and to explore the possible applications of uptake systems in the bioremediation of heavy metal-contaminated environments (9, 10), we further characterized the Cd2+ uptake activity of L. plantarum and isolated Mn2+-dependent mutant strains by chemical mutagenesis and ampicillin enrichment. The mutant strains were found to have reduced Mn2+ and Cd2+ uptake activities.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Organisms and culture conditions.

L. plantarum ATCC 14917 and ATCC 8014 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va. L. plantarum CCM 1904 and NCIMB 7220 were kind gifts from Francoise Bringel (7). Cells were grown in APT complex medium as described previously (5), except that Tween 80 was omitted. Omission of MnSO4 produced low-Mn2+ APT medium, containing 1.0 to 1.8 μM Mn2+ derived from the tryptone and yeast extract. Modified APT medium containing 100 mM MnSO4 was used to grow Mn2+-dependent mutants. It has the same composition as APT medium, except that it contains only 1 g of K2HPO4 per liter and the pH is adjusted to 5.6. Cells were grown at 37°C without shaking.

Cd2+ transport assay.

Cd2+ uptake experiments were performed with Mn2+-starved or Mn2+-sufficient cells of L. plantarum. To obtain Mn2+-starved cells, cells from an Mn2+-sufficient culture were washed with low-Mn2+ APT medium, diluted 1:100 in the same medium, and incubated overnight at 37°C. One milliliter of this culture was inoculated into 100 ml of fresh low-Mn2+ APT medium; after several hours at 37°C, growth tapered off at an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of about 0.5 due to Mn2+ limitation. The cells were washed with fresh low-Mn2+ APT medium, resuspended in transport medium (see below), and placed on ice. Mn2+-sufficient cells were harvested at an OD600 of about 0.5 and washed and resuspended as described above. Mn2+-starved mutant cells were obtained by harvesting log-phase cells from modified APT medium containing 100 mM MnSO4, washing the cells with fresh low-Mn2+ APT medium, resuspending the cells in low-Mn2+ APT medium, and incubating the cells at 37°C. They only divided two or three times due to Mn2+ limitation. Cells were harvested, washed, and resuspended as described above. The transport medium was low-Mn2+ APT medium, except that in some experiments, morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (MOPS), piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid (PIPES), or phosphate buffer with glucose was used.

To measure Cd2+ uptake, cells were incubated in a 37°C shaking water bath for 10 min, and a mixture of 109CdCl2 and nonradioactive CdCl2 was added. The number of cells was adjusted so that less than 5% of the total Cd2+ was taken up during the assay. Duplicate 0.2-ml samples were removed at different times, filtered through 0.45-μm-pore-size filters (Millipore Corporation, Bedford, Mass.), and rinsed twice with 4 ml of ice-cold low-Mn2+ APT medium, and radioactivity was counted with a Beckman LS-7500 scintillation counter.

Mn2+ or Cd2+ accumulation assay.

To measure long-term Mn2+ or Cd2+ uptake, cells were grown, harvested, washed, and resuspended as described above. After recovery at 37°C for 10 min, MnCl2 or CdCl2 was added to the culture to various final concentrations, and the mixture was incubated in a 37°C shaking water bath for 1 h. Cells were harvested and washed three times at 4°C with low-Mn2+ APT medium by centrifugation. The cell pellets were lyophilized, and the dried cells were digested overnight in 70% nitric acid at 45°C. The digestion mixture was diluted with water to a final nitric acid concentration of 10 to 15%. The total Mn2+ or Cd2+ content of the cells was measured with a Perkin-Elmer model 2380 atomic absorption spectrophotometer.

Isolation of Mn2+-dependent mutants.

L. plantarum ATCC 8014 cells were mutagenized with N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine (MNNG), and mutants were selected in BK-4 medium (19) containing ampicillin as described below. An overnight culture in APT medium was diluted 1:100 and grown to an OD600 of 0.1. The culture (10 ml) was harvested by centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 10 min, washed, and concentrated 15-fold in 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7). The cell suspension was treated with MNNG at a concentration of 170 μg/ml at 37°C for 15 min, harvested immediately at 3,000 × g for 2 min, washed in the same buffer twice, and resuspended in 100 ml of modified APT medium containing 100 mM MnSO4. This culture was incubated at 30°C for 9 h to allow the growth of mutants.

The above-described culture was harvested, washed twice with BK-4 medium without Mn2+, and resuspended in BK-4 medium containing 1 M sorbitol and 20 μM MnSO4 to a cell density of 106 cells/ml. This culture was incubated at 30°C for 12 h, and then ampicillin was added to a final concentration of 60 μg/ml. After another 12 h of incubation at 30°C, the culture was diluted and plated on modified APT medium plates containing 100 mM Mn2+ to produce about 500 colonies per plate. Colonies from the plates were transferred by use of toothpicks onto both low-Mn2+ (20 μM) and high-Mn2+ (100 mM) APT medium plates. Colonies growing on only the 100 mM Mn2+ APT medium plates were selected for further study.

RESULTS

Kinetics of Cd2+ uptake.

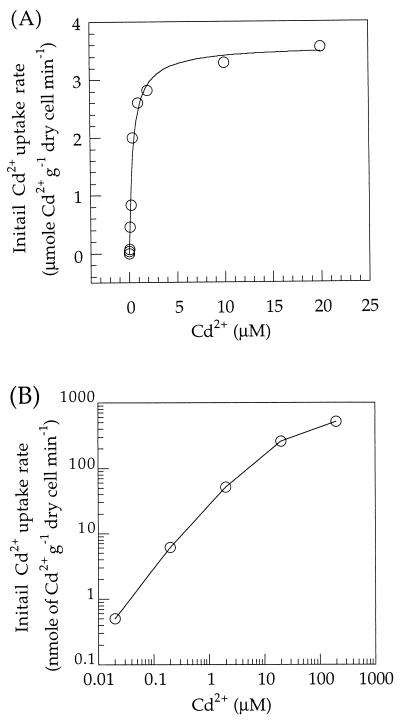

L. plantarum ATCC 14917 cells were assayed for their initial Cd2+ uptake rate in low-Mn2+ APT medium containing CdCl2 at concentrations of 0.01 to 200 μM (Fig. 1A and B). In Mn2+-starved cells, the uptake rates followed Michaelis-Menten kinetics (Fig. 1). The calculated Km was 0.44 μM, and the Vmax was 3.6 μmol g of dry cell−1 min−1. In Mn2+-sufficient cells, transport was not saturated, even at 200 μM Cd2+, so that the Km could not be calculated. The dramatically different level of transport between Mn2+-starved and Mn2+-sufficient cells indicated that Mn2+ starvation induced a high-affinity, high-velocity Cd2+ uptake system in this organism. Furthermore, the difference in kinetics indicated that Cd2+ uptake in Mn2+-starved cells was due to the induction of an uptake system which was repressed in Mn2+-sufficient cells. This result was observed for all L. plantarum strains tested: ATCC 8014, NCIMB 7220, and CCM 1904. The Cd2+ uptake activity of all these strains was comparable to that of ATCC 14917 in both Mn2+-starved and Mn2+-sufficient cells (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Kinetics of initial Cd2+ uptake by Mn2+-starved (A) or Mn2+-sufficient (B) L. plantarum ATCC 14917. Cells were prepared and preincubated for 10 min at 37°C in low-Mn2+ APT medium as described in Materials and Methods. The initial Cd2+ uptake rate was determined with duplicate 0.2-ml samples harvested 15 s after radioactive Cd2+ was added. The solid line in panel A results from fitting the data according to the Michaelis-Menten equation to produce a Km of 0.44 ± 0.07 μM and a Vmax of 3.57 ± 0.13 μmol of Cd2+ g of dry cell−1 min−1.

Specificity of Cd2+ uptake.

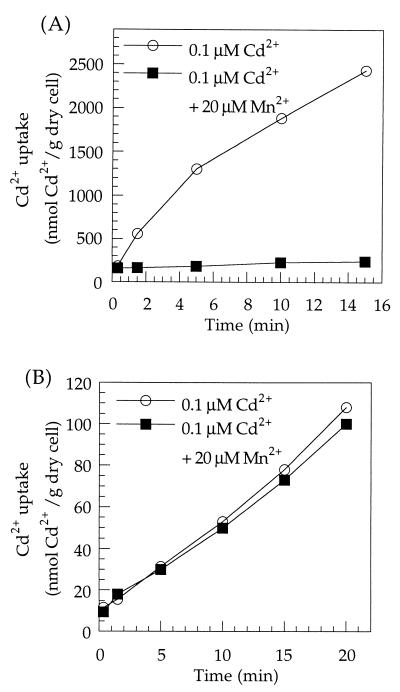

The cation specificity of Cd2+ uptake was investigated with both Mn2+-starved and Mn2+-sufficient cells by exposing them to 0.1 μM 109Cd2+ combined with 20 μM each of a series of other metal ions, including Mn2+ (Fig. 2A and B) and Zn2+, Cu2+, Co2+, Mg2+, Ca2+, Fe2+, and Ni2+ (data not shown). Only Mn2+ significantly inhibited the rate of Cd2+ uptake in Mn2+-starved cells (Fig. 2A), while none of the cations inhibited Cd2+ uptake in Mn2+-sufficient cells (Fig. 2B). The difference in cation specificity is further evidence that there are at least two different Cd2+ uptake systems in L. plantarum: a low-affinity, nonsaturable Cd2+ uptake system which is independent of Mn2+ starvation and is not inhibited by Mn2+ and a high-affinity Cd2+ uptake system which is induced by Mn2+ starvation and is inhibited by Mn2+.

FIG. 2.

Cation specificity of Cd2+ uptake by Mn2+-starved (A) or Mn2+-sufficient (B) L. plantarum ATCC 14017. Cells were prepared and preincubated for 10 min at 37°C in low-Mn2+ APT medium as described in Materials and Methods. The initial Cd2+ uptake rate was determined with duplicate 0.2-ml samples harvested 15 s after radioactive Cd2+ was added to a 0.1 μM final concentration together with 20 μM MnCl2.

A previous study (5) showed that many organic acids, such as citrate, stimulated Mn2+ uptake in starved L. plantarum cells. The presence of 20 mM citrate or other organic acids increased Mn2+ uptake over sixfold from that in a buffer solution (pH 6.7) containing 0.1 μM Mn2+. To test the effect of citrate on Cd2+ uptake in Mn2+-starved cells, uptake assays were carried out with various buffer solutions containing 0.1 μM Cd2+ and 20 mM citrate. In contrast to its reported effect on Mn2+ uptake, citrate at 20 mM did not increase but inhibited Cd2+ uptake by Mn2+-starved cells in HEPES buffer (pH 6.7) by about 23%. The same result was also observed with other buffer solutions containing 20 mM citrate. Since citrate forms stable complexes with both Cd2+ and Mn2+, its opposite effects on Cd2+ uptake and Mn2+ uptake in L. plantarum provide evidence that the form of Mn2+ recognized by the uptake system may be different from that of Cd2+.

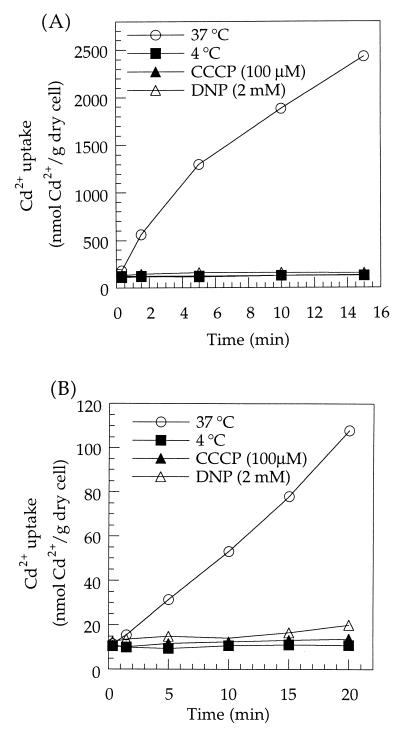

Energy dependence of Cd2+ uptake.

In order to determine the energy requirement of Cd2+ uptake by L. plantarum, the uncouplers 2,4-dinitrophenol and carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone were added to Mn2+-starved or Mn2+-sufficient cells in low-Mn2+ APT medium. The effect of low temperature was also studied by carrying out the uptake assay at 4°C. As shown in Fig. 3, when cells were poisoned or kept at 4°C, there was no significant uptake of Cd2+ by either Mn2+-starved or Mn2+-sufficient cells. Although low levels of 109Cd2+ were present at all the time points, the amount of radioactivity did not increase with time. These results indicated that Cd2+ uptake by both the saturable and the nonsaturable Cd2+ uptake systems in L. plantarum is energy dependent. These properties had been observed for Mn2+ uptake by Mn2+-starved cells (5).

FIG. 3.

Effect of low temperature or ionophores on Cd2+ uptake by Mn2+-starved (A) or Mn2+-sufficient (B) L. plantarum ATCC 14917. Cells were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. Cd2+ uptake was assayed with low-Mn2+ APT medium containing 0.1 μM Cd2+ at either 37°C (in the presence of carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone or 2,4-dinitrophenol) or 4°C.

Isolation and characterization of Mn2+-dependent mutants.

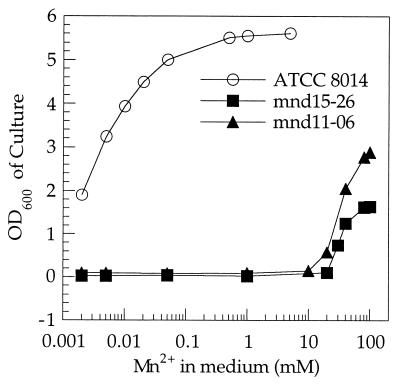

L. plantarum strains with mutations eliminating the high-affinity Mn2+ and Cd2+ uptake system should require a high concentration of Mn2+ for growth. Mutants of L. plantarum requiring such supplementation were isolated after MNNG mutagenesis and ampicillin enrichment. Two Mn2+-dependent strains, designated mnd11-06 and mnd15-26, were obtained after screening of 3,500 survivors of the enrichment process. Both strains failed to grow in normal or modified APT medium containing up to 10 mM Mn2+, and growth started only when the Mn2+ concentration was over 20 mM (Fig. 4). In contrast, the wild-type strain required only 2 μM Mn2+ for growth. The growth rate of the mutant strains did not reach that of the wild-type strain even at 100 mM Mn2+. However, anaerobic growth of the mutant strains started at a lower level of Mn2+ (1 to 5 mM). This result was expected because a high intracellular Mn2+ level (30 to 35 mM) is required for L. plantarum cells to grow under aerobic conditions, as Mn2+ acts as a scavenger of toxic oxygen species. These results suggested that the high Mn2+ requirement of the mutants was due to an intracellular limitation of Mn2+. The Mn2+ accumulation assay confirmed that the mutant strains accumulated a much lower level of Mn2+ than the wild-type strain (Table 1).

FIG. 4.

Mn2+-dependent growth of mutants isolated from L. plantarum ATCC 8014. A liquid culture of the mutant or parental strains was harvested, washed with low-Mn2+ APT medium, and diluted in modified APT medium containing different levels of Mn2+ to an OD600 of 0.01. After 24 h of incubation at 37°C, the OD600 was determined.

TABLE 1.

Mn2+ or Cd2+ accumulation in L. plantarum ATCC 8014 and its Mn2+-dependent mutantsa

| Strain | Accumulation (μmol/g of dry cell) of:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Mn2+ | Cd2+ | |

| ATCC 8014 | 48.2 ± 4.2 | 40.1 ± 3.0 |

| mnd11-06 | <0.5 | 1.7 ± 0.3 |

| mnd15-26 | <0.5 | 1.3 ± 0.3 |

Mn2+-starved cells were prepared and assayed in low-Mn2+ APT medium containing 10 μM Mn2+ or Cd2+ as described in the text. Total accumulation of Mn2+ or Cd2+ was measured by atomic absorption spectrophotometry.

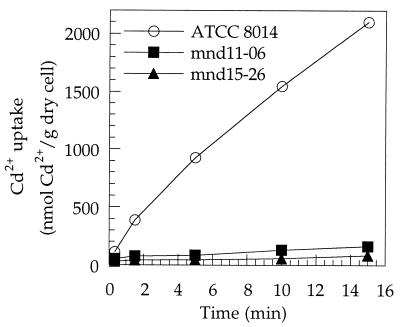

As shown in Fig. 5, the initial rate of Cd2+ uptake by strain mnd11-06 or mnd15-26 in low-Mn2+ APT medium containing 0.1 μM Cd2+ was less than 5 or 3% that of the wild-type strain, respectively, indicating that the high-affinity Cd2+ uptake system was not functional in either mutant.

FIG. 5.

Cd2+ uptake by Mn2+-dependent mutants of L. plantarum ATCC 8014. Mn2+-starved cells were prepared and assayed with low-Mn2+ APT medium containing 0.1 μM Cd2+ as described in the text.

To assay Cd2+ and Mn2+ accumulation, cells were exposed to 10 μM Cd2+ or Mn2+ and incubated for 1 h before being harvested. Cd2+ or Mn2+ accumulated by the cells was calculated by subtracting the accumulation before the addition of Cd2+ or Mn2+ from the accumulation after incubation. As shown in Table 1, mutant cells accumulated less than 5% the amount of Cd2+ taken up by wild-type cells, consistent with the results of the uptake assay. Mutant and wild-type cells grown in medium containing 50 mM Mn2+ were also tested for Cd2+ accumulation. Strain mnd11-06 accumulated the same level of Cd2+ as the wild-type strain, while strain mnd15-26 accumulated about 20% the wild-type level (data not shown). It is not clear whether the mutation affected the low-affinity Cd2+ uptake system in strain mnd15-26, as the cells were unhealthy.

DISCUSSION

Cd2+ uptake in L. plantarum was first reported by Archibald and Duong (5) in their study of Mn2+ uptake by L. plantarum ATCC 14917. However, the kinetics that they measured were different from what was seen in this study, as they observed high-affinity, high-velocity, nonsaturable Cd2+ uptake in Mn2+-starved cells and did not measure Cd2+ uptake in Mn2+-sufficient cells. Our kinetic parameters were determined from samples taken from 15 s to 5 min. The rapid initial uptake phase (within 15 s), which increased with increasing Cd2+, was subtracted, as it most likely represented cell surface binding. The resulting linear rate was used for the analysis of kinetics.

Cd2+ uptake has been reported for other gram-positive as well as gram-negative bacteria. In gram-positive organisms, such as B. subtilis (15) and S. aureus (22), Cd2+ competes for transport with Mn2+, while in E. coli, Cd2+ competes with Zn2+ (16). The reported Km values are 2.1, 1.8, 5.4, and 820 μM for Cd2+ uptake in E. coli (16), B. subtilis (15), S. aureus (22), and Pseudomonas putida (14), respectively. These values are higher than that for L. plantarum (0.44 μM), while the rate of uptake for L. plantarum (3.6 μmol g of dry cell−1 min−1) is comparable to those for other studied bacteria (reported in the same units: E. coli, 0.83; B. subtilis, 1.5; S. aureus, 2.6; and P. putida, 8.2).

L. plantarum and related lactic acid bacteria contain millimolar levels of Mn2+ for protection against oxygen radical damage (1–4). A high-affinity, high-velocity Mn2+ uptake system that creates a high Mn2+ content has been identified in L. plantarum. Interestingly, the Mn2+ uptake system also takes up Cd2+ and appears to have a higher affinity for Cd2+. A higher affinity of an Mn2+ uptake system for Cd2+ has also been found in S. aureus (20, 23). In terms of its crystal and hydrated radii, electron shell configuration, and citrate complex stability constants, Mn2+ is more similar to Co2+ or Fe2+ than to Cd2+. However, only Cd2+ inhibited Mn2+ uptake and only Mn2+ inhibited Cd2+ uptake by Mn2+-starved L. plantarum cells. It is possible that the form of Mn2+ or Cd2+ recognized by the uptake system may be other than the free ions. Archibald and Duong (5) found that an Mn2+ ion did not appear to be as available to the uptake system as Mn2+ complexed with an anion, such as citrate or acetate. They demonstrated that at pH 6.7, a variety of buffered organic acids provided good Mn2+ availability to the uptake system, and that at pH 5.5, Mn2+-starved L. plantarum cells could efficiently take up Mn2+ only when buffers contained citrate or related tricarboxylic acids. In this study, Cd2+ uptake was weakly inhibited by the presence of 20 mM citrate, suggesting that the forms of Mn2+ and Cd2+ recognized by the uptake system are different. It is likely that the Cd2+ form recognized by the uptake system is the free or hydrated ion instead of one complexed with an anion.

While Mn2+ inhibited Cd2+ uptake by the high-affinity Cd2+ uptake system in L. plantarum, none of the divalent cations tested, i.e., Mn2+, Zn2+, Cu2+, Co2+, Mg2+, Ca2+, Fe2+, and Ni2+, inhibited Cd2+ uptake by the low-affinity Cd2+ uptake system expressed in Mn2+-sufficient cells. It is unlikely that cells evolved this uptake system for Cd2+, and its physiological function is not known. It could be a transport system similar to the tetracycline-resistant systems from pBR322 and S. aureus (11, 13). Both of these systems mediate potassium transport in E. coli. The pBR322 tetracycline-resistant element also confers on E. coli cells an increased sensitivity to a variety of organic compounds and cadmium (6, 12, 18).

Two mutants which grew only in medium supplemented with high levels of Mn2+ were isolated. Their growth requirement for Mn2+ was more than 5,000 times higher than that of the parental strain. Mn2+ starvation-induced Cd2+ uptake in both mutants was less than 5% the wild-type rate. The results of an analysis of long-term Mn2+ or Cd2+ accumulation by the mutant strains also indicated that the mutations in these strains eliminated the high-affinity Mn2+ and Cd2+ uptake system. Cd2+-resistant mutants of B. subtilis were isolated by growth of the parental strain in high concentrations of Cd2+ (8, 16, 17). The mutants had reduced Cd2+ transport, but Mn2+ transport was unaffected.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Peter C. Hinkle and John D. Helmann for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by a grant from the Cornell Superfund Basic Research and Education Program of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

REFERENCES

- 1.Archibald F S, Fridovich I. Manganese and defenses against oxygen toxicity in Lactobacillus plantarum. J Bacteriol. 1981;145:442–451. doi: 10.1128/jb.145.1.442-451.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Archibald F S, Fridovich I. Manganese, superoxide dismutase, and oxygen tolerance in some lactic acid bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1981;146:928–936. doi: 10.1128/jb.146.3.928-936.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Archibald F S, Fridovich I. Investigation of the state of the manganese in Lactobacillus plantarum. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1982;215:589–596. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(82)90120-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Archibald F S, Fridovich I. The scavenging of the superoxide radical by manganous complexes: in vitro. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1982;214:452–463. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(82)90049-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Archibald F S, Duong M. Manganese acquisition by Lactobacillus plantarum. J Bacteriol. 1984;158:1–8. doi: 10.1128/jb.158.1.1-8.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bochner B R, Huang H C, Schieven G L, Ames B N. Positive selection for loss of tetracycline resistance. J Bacteriol. 1980;143:926–933. doi: 10.1128/jb.143.2.926-933.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bringel F, Hubert J. Optimized transformation by electroporation of Lactobacillus plantarum strains with plasmid vectors. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1990;33:664–670. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burke B E, Pfister R M. Cadmium transport by a Cd2+-sensitive and a Cd2+-resistant strain of Bacillus subtilis. Can J Microbiol. 1986;32:539–542. doi: 10.1139/m86-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen S-L, Wilson D B. Construction and characterization of Escherichia coli genetically engineered for bioremediation of Hg2+-contaminated environments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:2442–2445. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.6.2442-2445.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen S-L, Kim E-K, Shuler M L, Wilson D B. Hg2+ removal by genetically engineered Escherichia coli in a hollow fiber bioreactor. Biotechnol Prog. 1998;14:667–671. doi: 10.1021/bp980072i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dosch D C, Salvacion F F, Epstein W. Tetracycline resistance element of pBR322 mediates potassium transport. J Bacteriol. 1984;160:1188–1190. doi: 10.1128/jb.160.3.1188-1190.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Griffith J K, Buckingham J M, Hanner J L, Hildebrand C E, Walters R A. Plasmid-conferred tetracycline resistance confers collateral cadmium sensitivity of E. coli. Plasmid. 1982;8:86–88. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(82)90044-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guay G G, Tuckman M, McNicholas P, Rothstein D M. The tetK gene from Staphylococcus aureus mediates the transport of potassium in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:4927–4929. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.15.4927-4929.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higham D P, Sadler P J, Scawen M D. Cadmium resistance in Pseudomonas putida: growth and uptake of cadmium. J Gen Microbiol. 1985;131:2539–2544. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laddaga R A, Bessen R, Silver S. Cadmium-resistant mutant of Bacillus subtilis 168 with reduced cadmium transport. J Bacteriol. 1985;162:1106–1110. doi: 10.1128/jb.162.3.1106-1110.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laddaga R A, Silver S. Cadmium uptake in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1985;162:1100–1105. doi: 10.1128/jb.162.3.1100-1105.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mahler I, Levinson H S, Wang Y, Halvorson H O. Cadmium- and mercury-resistant Bacillus subtilis strains from a salt marsh and from Boston Harbor. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1986;52:1293–1298. doi: 10.1128/aem.52.6.1293-1298.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maloy S R, Nunn W D. Selection for loss of tetracycline resistance by Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1981;145:1110–1112. doi: 10.1128/jb.145.2.1110-1111.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Masson A, Kammerer B, Hubert J-C. Selection and biochemical studies of pyrimidine-requiring mutants of Lactobacillus plantarum. J Appl Bacteriol. 1994;77:88–95. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perry R D, Silver S. Cadmium and manganese transport in Staphylococcus aureus membrane vesicles. J Bacteriol. 1982;150:973–976. doi: 10.1128/jb.150.2.973-976.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silver S, Perry R D, Tynecka Z, Kinscherf T G. Mechanisms of bacterial resistance to the toxic heavy metals antinomy, arsenic, cadmium, mercury and silver. In: Mitsuhashi S, editor. Drug resistance in bacteria. Tokyo, Japan: Japanese Scientific Societies Press; 1982. pp. 347–361. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tynecka Z, Gos Z, Zajac J. Reduced cadmium transport determined by a resistance plasmid in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1981;147:305–312. doi: 10.1128/jb.147.2.305-312.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vallee B L, Ulmer D D. Biochemical effects of mercury, cadmium, and lead. Annu Rev Biochem. 1972;41:91–128. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.41.070172.000515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]