Abstract

Background

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a frequent complication in patients with cancer and a leading cause of morbidity and death.

Objectives

The objective of the RIETECAT study was to compare the long‐term effectiveness and safety of enoxaparin versus dalteparin or tinzaparin for the secondary prevention of VTE in adults with active cancer.

Methods

We used the data from the multicenter, multinational RIETE registry to compare the rates of VTE recurrences, major bleeding, or death over 6 months in patients with active cancer and acute VTE using full doses of enoxaparin versus dalteparin or tinzaparin, and a multivariable Cox proportional hazard model was used to analyze the primary end point.

Results

From January 2009 to June 2018, 4451 patients with active cancer received full doses of the study drugs: enoxaparin, 3526 patients; and dalteparin or tinzaparin, 925 (754 + 171) patients. There was limited difference in VTE recurrences (2.0% vs 2.5%) and mortality rate (19% vs 17%) between the enoxaparin and dalteparin or tinzaparin subgroups. However, there was a slight numerical increase in major bleeding (3.1% vs 1.9%). Propensity score matching confirmed that there were no differences in the risk for VTE recurrences (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 0.81; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.48‐1.38), major bleeding (aHR, 1.40; 95% CI, 0.80‐2.46), or death (aHR, 1.07; 95% CI, 0.88‐1.30) between subgroups.

Conclusions

In RIETECAT, in patients with cancer and VTE receiving full‐dose enoxaparin or dalteparin or tinzaparin, no statistically significant differences were observed regarding effectiveness and safety outcomes over a 6‐month period.

Keywords: cancer, cohort, dalteparin, enoxaparin, LMWH, recurrences, tinzaparin, venous thromboembolism

Essentials.

Patients with cancer and venous thromboembolism (VTE) should receive long‐term anticoagulant therapy.

RIETECAT compared the effectiveness and safety of enoxaparin versus dalteparin or tinzaparin.

There was no statistical difference between treatments in recurrent VTE.

There was no statistical difference between treatments in bleeding complications or death.

1. INTRODUCTION

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a frequent complication in patients with cancer and a leading cause of death, morbidity, delays in care, and increased costs. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 Current practice guidelines recommend, on the basis of data from randomized trials, that patients with cancer and VTE receive long‐term therapy with low‐molecular‐weight heparin (LMWH) over vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) or direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs). 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 At the time of this study, in Europe, only dalteparin and tinzaparin have this specific indication for patients with cancer mentioned in their label. Enoxaparin, another LMWH, is also used in patients with cancer and VTE, although at the time it was not approved for this indication.

The efficacy and safety of enoxaparin versus VKAs for the long‐term therapy of VTE in patients with cancer was demonstrated in two randomized controlled trials. 11 , 12 In the real‐world setting, however, the effectiveness and safety of enoxaparin compared with dalteparin or tinzaparin in patients with cancer remains unexplored. Thus, we used the data in the RIETE (Registro Informatizado de la Enfermedad TromboEmbólica) registry, to compare the effectiveness and safety of enoxaparin versus dalteparin or tinzaparin in patients with active cancer and acute VTE over a 6‐month period.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design

RIETE (clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT02832245) is an ongoing prospective, multicenter, multinational registry of consecutive patients with objectively confirmed VTE. 13 To date, RIETE is the world’s largest database of patients with VTE. The RIETECAT study is an analysis of patients with active cancer from RIETE presenting with VTE and receiving initial and long‐term therapy with full doses of enoxaparin versus dalteparin or tinzaparin. The information on LMWH regimen (once daily or twice daily) was introduced in RIETE on January 1, 2009. Thus, the study included patients from January 2009 to June 2018. Full doses were defined as (i) enoxaparin: 1 mg/kg ± 20% twice daily or 1.5 mg/kg ± 20% once daily for initial and long‐term therapy; (ii) dalteparin: 200 IU/kg ± 20% once daily during the first month, and then 150 IU/kg ± 20% once daily; and (iii) tinzaparin: 175 IU/kg ± 20% once daily for initial and long‐term therapy. Patients were assessed for up to 6 months following the index date or until the first individual occurrence of each clinical outcome (VTE recurrences, major bleeding, nonmajor bleeding of clinical significance, death) or due to loss during the 6‐month period. The baseline characteristics and treatment exposures were reported to describe the population included in RIETECAT. The rates of VTE recurrences, bleeding, and death were compared over a period of 6 months after the index VTE.

2.2. Patient selection

Consecutive patients were included who had an acute episode of symptomatic, objectively confirmed VTE between January 1, 2009, and June 30, 2018, and fulfilled the following criteria: age ≥18 years; active cancer (defined by a histological or cytological confirmation of malignancy and at least one of the following features: cancer diagnosis within 6 months before VTE, metastatic disease or hematological malignancy not in complete remission, or treatment for cancer during the previous 6 months); start of treatment with full‐dose enoxaparin, dalteparin, or tinzaparin within the first 48 hours after VTE diagnosis.

To be enrolled in the registry, patients needed to have had an acute deep vein thrombosis (DVT), pulmonary embolism (PE), or both, confirmed by objective tests (ie, contrast venography or compression ultrasonography for suspected DVT, helical computed tomography scan, ventilation‐perfusion lung scintigraphy, or pulmonary angiography for suspected PE).

Patients were excluded from the RIETECAT study if they had: (i) prior VTE <12 months before the index event; (ii) started LMWH therapy >48 hours after the index VTE; (iii) started enoxaparin, dalteparin, or tinzaparin but switched to other drugs before day 90; or (iv) started enoxaparin, dalteparin, or tinzaparin at full doses, but then switched to other doses before day 90, in the absence of VTE recurrences or bleeding events. Patients who started on enoxaparin, dalteparin, or tinzaparin at full doses but then switched to nonfull doses or other anticoagulants before day 90 in the absence of VTE recurrences or bleeding events were excluded from the main study but were included in a sensitivity analysis.

2.3. Data elements

Variables routinely collected in RIETE included baseline characteristics (sex, age, body weight); initial VTE presentation (proximal‐, bilateral‐ or upper‐limb DVT); systolic blood pressure levels; heart rate; blood oxygen saturation levels (in patients with PE); cancer characteristics (location, time since cancer diagnosis, presence of metastases, and oncologic therapy); additional risk factors for VTE (recent surgery within 2 months before index VTE, recent immobility with bathroom privileges for >4 days within 2 months, estrogen use, pregnancy or postpartum, and personal history of VTE); comorbidities and blood tests at baseline (including anemia, leukocyte and platelet count, and creatinine clearance [CrCl] levels); and concomitant therapies, including antiplatelet drugs and corticosteroids.

2.4. Study objectives and outcomes

The primary objective of RIETECAT was to assess the noninferiority of enoxaparin versus dalteparin or tinzaparin in preventing VTE recurrences in adult patients with active cancer over a 6‐month period. VTE recurrences were defined as composite outcomes of symptomatic, objectively confirmed DVT and fatal or nonfatal PE. A noninferiority margin of 1.5 was determined based on a review of the literature and inputs from clinical experts. With an overall sample size of 4451 subjects, and considering the expected VTE recurrence rate in the reference group was 2.5% at 6 months, the power to show noninferiority with the margin of 1.5 was 80%, using a one‐sided test with a 0.03 significance level. Noninferiority of enoxaparin versus dalteparin or tinzaparin on VTE incidence would be demonstrated if the upper limit of 95% confidence interval (CI) of the hazard ratio (HR) was lower than 1.5. It was assumed that the HR was constant over the study period. Cox proportional hazards models were used to analyze the data. Secondary effectiveness outcomes were the individual components of VTE recurrences, that is, symptomatic, objectively confirmed DVT recurrences and PE recurrences (fatal and nonfatal). The secondary objective of RIETECAT was to compare the safety of enoxaparin versus dalteparin or tinzaparin in adult patients with active cancer over a 6‐month period. Secondary safety outcomes were major bleeding events (fatal or nonfatal), all‐cause death, fatal PE, fatal bleeding, and nonmajor but clinically relevant (NMCR) bleeding. Only bleeding events that occurred within 24 hours after the last dose of the study drug (enoxaparin, dalteparin, or tinzaparin) were considered. Major bleeding was defined as bleeding events that were overt and required a transfusion of ≥2 units of blood; were retroperitoneal, spinal, intracranial, intrathecal, intrapericardial, or intraocular; or were fatal. NMCR bleeding were those overt bleeds not meeting criteria for major bleeding but requiring medical assistance. Fatal bleeding was defined as any death occurring within 10 days of a major bleeding episode, in the absence of an alternative cause of death. Fatal PE was defined as any death occurring within 10 days of a PE episode (either the index event or recurrent PE) in the absence of an alternative cause of death.

2.5. Statistical analyses

Patient characteristics at the time of initial VTE diagnosis were described and compared across the two exposure categories. Differences across subgroups were assessed using a t test for continuous variables, and a chi‐square test for categorical variables. For each treatment exposure category, the proportion of patients with primary or secondary outcomes at 6 months was obtained. Multivariable analyses were performed. A multivariable Cox proportional hazard model was used to analyze the primary end point. Crude and adjusted HRs, and corresponding 95% CIs of the primary and secondary outcomes were estimated using Cox proportional hazards models. Treatment exposure served as a time‐dependent variable. Models were adjusted for the following covariates: sex, age, body weight, initial presentation of VTE (unstable PE, stable PE, or DVT), location of cancer (according to Khorana score), metastases, treatment for cancer, recent immobility, recent surgery, chronic heart or lung disease, recent (<30 days prior) major bleeding, concomitant therapy with antiplatelets and/or corticosteroids, anemia, leukocyte count, platelet count, CrCl levels, size of hospital (>500 beds, 250‐500 beds, or <250 beds), and year of diagnosis.

In addition, an analysis was conducted on the primary end point, using propensity score matching to adjust for differences in the baseline characteristics of patients exposed to enoxaparin versus dalteparin or tinzaparin (same covariates as those used in the Cox model of the primary analysis). As no adjustments for multiplicity were made for secondary evaluation variables, all tests were exploratory. Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Similar analyses were conducted for the sensitivity analysis. Patient characteristics at baseline were compared across the two exposure categories; for each treatment exposure category, the proportion of patients with primary or secondary outcomes at 6 months was obtained, and a multivariable Cox proportional hazard model was used to analyze the primary end point. Crude and adjusted HRs, and corresponding 95% CIs of the primary and secondary outcomes were estimated using Cox proportional hazards models. Treatment exposure served as a time‐dependent variable. Models were adjusted for the same covariates as those listed above.

3. RESULTS

From March 2001 to June 2018, 84 918 patients with VTE were recruited in RIETE. Of these, 21 234 had active cancer. The use of LMWH for the long‐term therapy of VTE in patients with active cancer progressively increased from 40% to 80%, the use of VKAs decreased, and the use of DOACs increased from zero to 10% (Figure S1A). Among all LMWHs, enoxaparin accounted for the largest proportion (Figure S1B). Over 50% of patients in Europe received LMWH as long‐term therapy for VTE (Table S1). Its use in other countries also reached a high proportion, except in Brazil, where VKAs accounted for 93% of use.

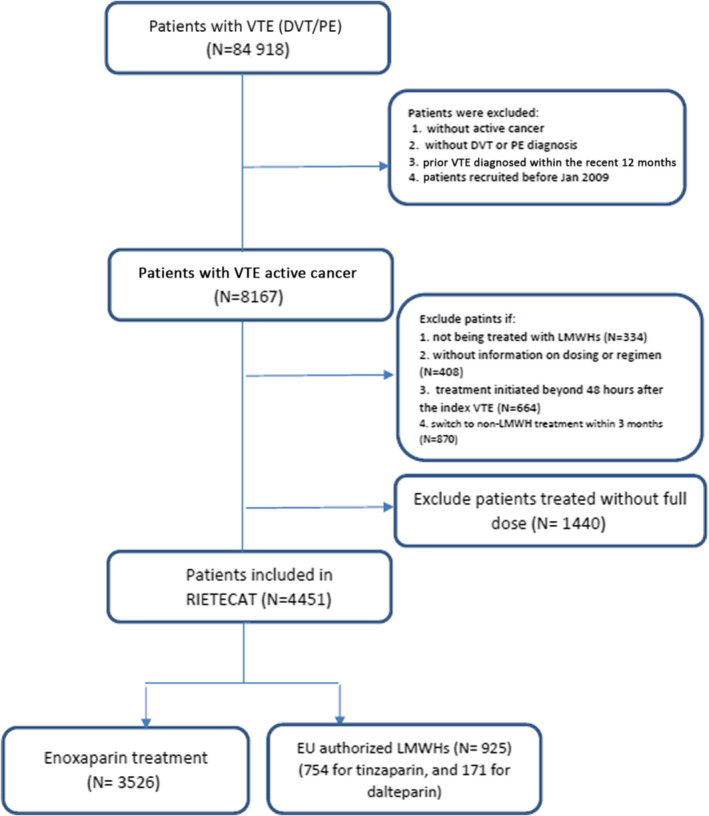

In total, 8167 patients with active cancer and VTE were diagnosed from January 2009 to June 2018. For the current study, we excluded 334 patients (4.1%) who received long‐term therapy with other drugs, 408 (5.0%) with no information on LMWH doses or regimen, 664 (8.1%) who started with LMWH beyond the first 48 hours, and 870 (10.6%) who switched from LMWH to other drugs (mostly VKAs) within the first 3 months (Figure 1). Thus, there were 5891 patients: 4704 (80%) received enoxaparin, 257 (4.4%) received dalteparin, and 930 (16%) received tinzaparin. Among these, we excluded 1440 patients (18%) who did not receive the recommended doses (±20%) or regimen of LMWH (Table S2). Thus, the main study analysis included 4451 patients: 3526 treated with enoxaparin, 171 treated with dalteparin, and 754 treated with tinzaparin.

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart of patients. DVT, deep vein thrombosis; LMWH, low‐molecular‐weight heparin; PE, pulmonary embolism; VTE, venous thromboembolism

3.1. Baseline characteristics

Patients receiving enoxaparin were more likely to initially present with PE (58%) than those on dalteparin or tinzaparin (44%) (Table 1). Among patients presenting with PE, those receiving enoxaparin were more likely to have tachycardia (36%) than those on dalteparin or tinzaparin (30%). Among patients initially presenting with DVT, those on enoxaparin were more likely to have proximal lower‐limb DVT (80%) than those on dalteparin or tinzaparin (62%). Patients receiving enoxaparin were also more likely to have been immobilized for ≥4 days (16%) or to receive corticosteroids (19%) or antiplatelet drugs (16%) concomitantly than patients receiving dalteparin or tinzaparin (12%, 13%, and 16%, respectively) but less likely to have had prior VTE (7.5% compared with 9.6% in the dalteparin or tinzaparin subgroup).

TABLE 1.

Patient demographics, clinical characteristics, and underlying conditions at baseline in patients receiving recommended doses of LMWH

| Enoxaparin | Dalteparin or tinzaparin | |

|---|---|---|

| Patients, N | 3526 | 925 |

| Demographics | ||

| Male sex, n (%) | 1670 (47) | 448 (48) |

| Age (mean years ± SD) | 68 ± 13 | 67 ± 13 |

| Body weight (mean kg ±SD) | 73 ± 14 | 74 ± 14 |

| Race/ethnicity a , n (%) | ||

| White | 1315 (37) | 292 (32) |

| Latino | 39 (1.1) | 5 (0.5) |

| Asian | 19 (0.5) | 3 (0.3) |

| Arab | 4 (0.1) | 4 (0.4) |

| Mixed/other | 15 (0.4) | 6 (0.6) |

| Not provided | 2134 (61) | 615 (66) |

| Initial VTE presentation, n (%) | ||

| PE | 2058 (58) | 411 (44) |

| SBP levels <100 mm Hg | 188 (9.1) | 32 (7.8) |

| Heart rate >100 bpm | 727 (36) | 122 (30) |

| Sat O2 levels <90% | 298 (29) | 43 (24) |

| Isolated DVT | 1468 (42) | 514 (56) |

| Proximal | 1178 (80) | 320 (62) |

| Bilateral lower limb | 69 (4.7) | 25 (4.9) |

| Upper limb | 309 (21) | 198 (38) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||

| Chronic heart disease | 185 (5.2) | 50 (5.4) |

| Chronic lung disease | 443 (13) | 99 (11) |

| Chronic liver disease | 100 (2.8) | 22 (2.4) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 115 (3.3) | 32 (3.5) |

| Recent (<30 days) major bleeding | 75 (2.1) | 13 (1.4) |

| Anemia | 1442 (41) | 351 (38) |

| Platelet count <100,000/mm3 | 174 (4.9) | 44 (4.8) |

| CrCl levels ˂30 mL/min | 142 (4.0) | 29 (3.1) |

| Additional risk factors for VTE | ||

| Postoperative | 486 (14%) | 117 (13%) |

| Recent immobility ≥4 days | 579 (16%) | 114 (12%) |

| Prior VTE | 266 (7.5%) | 89 (9.6%) |

| Concomitant medications, n (%) | ||

| Corticosteroids | 613 (19) | 135 (16) |

| Antiplatelets | 540 (16) | 113 (13) |

Abbreviations: bpm, beats per minute; CrCl, creatinine clearance; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; LMWH, low‐molecular‐weight heparin; PE, pulmonary embolism; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SD, standard deviation; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

Information on race/ethnicity was incorporated in RIETE on April 2014.

Comorbidities did not differ between the two subgroups regarding chronic heart failure, chronic lung disease, gastrointestinal diseases, or current anemia. In each subgroup, most patients (97.9% vs 98.6%) had no recent history of major bleeding (within 1 month before index VTE). Comorbidities that might influence coagulation were reported, and there were no significant differences between the two treatment subgroups regarding the incidence of patients with liver cirrhosis (29 [0.82%] vs 8 [0.86%]), chronic liver disease (41 [1.2%] vs 11 [1.2%]), chronic thrombocytopenia (5 [0.14%] vs 2 [0.22%]), or antiphospholipid syndrome (5 [0.14%] vs 1 [0.11%]).

3.2. Cancer characteristics

The majority (≈92%) of patients in both subgroups had solid cancers. There were no differences in cancer sites, except for breast cancer, which was slightly less likely in patients receiving enoxaparin. The median time elapsed from cancer diagnosis to VTE was slightly shorter in patients on enoxaparin (4 vs 5 months; Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Cancer characteristics

| Enoxaparin | Dalteparin or tinzaparin | |

|---|---|---|

| Patients, N | 3526 | 925 |

| Location, n (%) | ||

| Lung | 639 (18) | 151 (16) |

| Colorectal | 478 (14) | 134 (15) |

| Breast | 433 (12) | 140 (15) |

| Prostate | 291 (8.3) | 62 (6.7) |

| Hematological | 277 (7.9) | 70 (7.6) |

| Bladder | 183 (5.2) | 49 (5.3) |

| Pancreas | 178 (5.0) | 50 (5.4) |

| Brain | 147 (4.2) | 29 (3.1) |

| Gastric | 130 (3.7) | 24 (2.6) |

| Uterine | 129 (3.7) | 43 (4.6) |

| Ovary | 120 (3.4) | 41 (4.4) |

| Kidney | 76 (2.2) | 19 (2.1) |

| Oropharynx/larynx | 62 (1.8) | 18 (1.9) |

| Carcinoma of unknown origin | 57 (1.6) | 14 (1.5) |

| Esophagus | 39 (1.1) | 10 (1.1) |

| Others | 287 (8.1) | 71 (7.7) |

| Time since cancer diagnosis | ||

| Mean months ±SD | 20 ± 42 | 23 ± 45 |

| Cancer stage, n (%) | ||

| With metastases | 1845 (52) | 504 (54) |

| Current cancer therapy, n (%) | ||

| Radiotherapy | 496 (14) | 107 (12) |

| Chemotherapy | 1540 (44) | 525 (57) |

| Hormonal | 410 (12) | 112 (12) |

| Other | 40 (1.1) | 9 (0.97) |

| None | 1040 (29.0) | 172 (19) |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation.

3.3. Treatment characteristics

For initial therapy, the median duration was 8 days in patients on enoxaparin and 27 days in those on dalteparin or tinzaparin, until the regimen or doses changed (Table 3). Mean daily doses were 195 ± 16 IU/kg/d in patients on twice‐daily enoxaparin, 148 ± 15 IU/kg/d in those on once‐daily enoxaparin, 176 ± 22 IU/kg/d in those on once‐daily dalteparin, and 177 ± 14 IU/kg/d in those on once‐daily tinzaparin. Overall, 34% of patients on enoxaparin and 21% of patients on dalteparin or tinzaparin had changed their daily dose during the 6‐month period (Table 3). Most of them experienced a one‐time dose decrease (patients were on initial therapy and switched to long‐term therapy). Moreover, 78% of patients receiving enoxaparin (and all patients on dalteparin or tinzaparin) maintained the initial regimen (once daily alone or twice daily alone). In patients whose regimen was modified, the majority was a switch from twice‐daily to once‐daily injections, while very few had a switch from once‐daily to twice‐daily injections or experienced multiple changes.

TABLE 3.

Treatment characteristics

| Enoxaparin | Dalteparin or tinzaparin | |

|---|---|---|

| Patients, N | 3526 | 925 |

| Switching LMWH doses | ||

| Yes, n (%) | 1215 (34) | 197 (21) |

| Number of days until switch | ||

| Mean days ±SD | 17 ± 27 | 28 ± 28 |

| Median days (min‐max) | 8 (1‐178) | 27 (1‐150) |

| Changes of daily doses, n (%) | ||

| Increase in doses | 225 (6.4) | 46 (5.0) |

| Decrease in doses | 1095 (31) | 172 (19) |

| Both increase and decrease | 105 (3.0) | 21 (2.3) |

| Number of doses switch | ||

| 1 | 1027 (29) | 173 (19) |

| 2 | 134 (3.8) | 18 (1.9) |

| ≥3 | 54 (1.5) | 6 (0.65) |

| Regimen, n (%) | ||

| Once daily | 891 (25) | 925 (100) |

| Twice daily | 1856 (53) | 0 |

| Regimen modification | ||

| Twice daily to once daily | 687 (20) | 0 |

| Once daily to twice daily | 42 (1.2) | 0 |

| Multiple dosing changes | 50 (1.4) | 0 |

| Different drugs | 0 | 49 (5.3) |

Abbreviations: LMWH, low‐molecular‐weight heparin; SD, standard deviation.

3.4. Clinical outcomes

In the 6 months following the acute VTE, of a total of 4451 patients, 93 patients presented with VTE recurrences (PE recurrences, 47; DVT recurrences, 47), 129 had major bleeding (intracranial, 21), 111 had NMCR bleeding, and 823 died (fatal PE, 39; fatal bleeding, 20).

The rate of recurrent VTE was 2.0% (n = 70/3526) in patients receiving enoxaparin and 2.5% (n = 23/925) in the dalteparin or tinzaparin subgroup (Table 4). Similarly, there was limited difference in DVT recurrences between the enoxaparin and dalteparin or tinzaparin subgroups (1.0% vs 1.2%) or PE recurrences between the enoxaparin and dalteparin or tinzaparin subgroups (0.99% vs 1.3%) (Table 4). The rate of major bleeding was numerically higher in the enoxaparin subgroup compared with the dalteparin or tinzaparin subgroup (3.1% vs 1.9%). There were no differences in the rates of NMCR bleeding (2.5% vs 2.6%) or all‐cause death (19% vs 17%) between the two subgroups. Similarly, there was no difference in the rates of the composite of fatal PE or fatal bleeding (1.4% vs 1.2%) between the treatment subgroups (Table 4). The rates of major bleeding in specific sites are given in Table S3.

TABLE 4.

Six‐month outcomes

|

Enoxaparin n = 3526 |

Dalteparin or tinzaparin n = 925 |

|

|---|---|---|

| Main outcome, n (%) | ||

| Recurrent VTE a | 70 (2.0) | 23 (2.5) |

| Secondary outcomes | ||

| Recurrent DVT b | 36 (1.0) | 11 (1.2) |

| Recurrent PE c | 35 (0.99) | 12 (1.3) |

| Safety outcomes | ||

| Major bleeding c | 111 (3.1) | 18 (1.9) |

| Recurrent VTE or major bleeding | 181 (5.1) | 41 (4.4) |

| Nonmajor bleeding | 87 (2.5) | 24 (2.6) |

| All‐cause death | 666 (19) | 157 (17) |

| Cause of death | ||

| Pulmonary embolism | 33 (0.94) | 6 (0.65) |

| Bleeding | 15 (0.43) | 5 (0.54) |

| Fatal PE or fatal bleeding | 48 (1.4) | 11 (1.2) |

| Sudden, unexpected death | 3 (0.09) | 3 (0.32) |

Abbreviations: DVT, deep vein thrombosis; PE, pulmonary embolism; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

Composite effectiveness outcome = symptomatic DVT and fatal or nonfatal PE.

Symptomatic.

Fatal and nonfatal.

3.5. Multivariable analysis

On the adjusted analyses, there were no differences between treatment subgroups in terms of VTE recurrences with enoxaparin meeting the prespecified criterion for noninferiority of 1.5 (adjusted HR [aHR], 0.82; 95% CI, 0.50‐1.34; P = .008 for noninferiority), DVT recurrences (aHR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.41‐1.70; P = .62), PE recurrences (aHR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.41‐1.56; P = .51), nonmajor bleeding of clinical significance (aHR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.55‐1.41; P = 0.60) or all‐cause death (aHR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.81‐1.16; P = .77). The rate of major bleeding was nonsignificantly higher in patients treated with enoxaparin (aHR, 1.52; 95% CI, 0.90‐2.58; P = 0.12; Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Time‐dependent Cox proportional hazards for the crude and adjusted association between outcomes and treatment

| Cox proportional hazards | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Crude analysis | Adjusted analysis | Propensity score | |

| Recurrent DVT a | 0.88 (0.45‐1.73) | 0.83 (0.41‐1.70) | 0.90 (0.43‐1.90) |

| Recurrent PE b | 0.78 (0.41‐1.51) | 0.79 (0.41‐1.56) | 0.73 (0.35‐1.55) |

| Recurrent VTE c | 0.82 (0.51‐1.31) | 0.82 (0.50‐1.34) | 0.81 (0.48‐1.38) |

| Major bleeding b | 1.67 (1.02‐2.76) | 1.522 (0.90‐2.58) | 1.40 (0.80‐2.46) |

| Non‐major bleeding | 0.97 (0.62‐1.53) | 0.88 (0.55‐1.41) | 0.89 (0.53‐1.49) |

| All‐cause death | 1.14 (0.96‐1.36) | 0.97 (0.81‐1.16) | 1.07 (0.88‐1.30) |

| Fatal PE | 1.46 (0.61‐3.47) | 1.05 (0.43‐2.55) | 1.00 (0.37‐2.71) |

| Fatal bleeding | 0.81 (0.30‐2.24) | 0.57 (0.20‐1.64) | 0.44 (0.12‐1.65) |

Results expressed as hazard ratio (95% confidence interval).

Abbreviations: DVT, deep vein thrombosis; PE, pulmonary embolism; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

Symptomatic.

Fatal and nonfatal.

Composite effectiveness outcome = symptomatic DVT and fatal or nonfatal PE.

Results of the propensity score matching involved 1662 patients on enoxaparin and 903 patients on dalteparin or tinzaparin. The matched analysis revealed no significant differences in the risk for DVT recurrences (aHR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.43‐1.90; P=0.78), PE recurrences (aHR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.35‐1.55; P = 0.42), major bleeding (aHR, 1.40; 95% CI, 0.80‐2.46; P = 0.24), nonmajor bleeding of clinical significance (aHR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.53‐1.49; P = .64), or death (aHR, 1.07; 95% CI, 0.88‐1.30; P = .48) between subgroups.

3.6. Sensitivity analysis

The sensitivity analysis had a total of 5128 (n = 4099 enoxaparin; n = 1029 dalteparin/tinzaparin) patients, which included 677 of the 1440 excluded patients who started on full‐dose LMWH but were then moved to another anticoagulant treatment or to a nonfull dose before day 90, and the 4451 patients from the primary analysis. The 677 patients consisted of 279 patients on enoxaparin and 21 patients on dalteparin or tinzaparin who were prescribed recommended doses within the first 48 hours after VTE diagnosis but were then transferred to an alternative treatment, and 294 patients on enoxaparin and 83 patients on dalteparin or tinzaparin who received recommended doses within the first 48 hours after VTE diagnosis but were then switched to nonfull doses. The 6‐month outcomes observed with this larger cohort were similar to those observed in the primary analysis. The rate of recurrent VTE was 2.1% in the enoxaparin group and 2.4% in the dalteparin or tinzaparin subgroup, and the rate of major bleeding was 2.8% in the enoxaparin subgroup and 1.7% in the dalteparin or tinzaparin subgroup. The results from the adjusted analyses were also similar to those from the primary analysis and similar between the subgroups in terms of VTE recurrences (aHR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.57‐1.41), DVT recurrences (aHR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.46‐1.76), PE recurrences (aHR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.49‐1.73), nonmajor bleeding of clinical significance (aHR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.56‐1.33) or all‐cause death (aHR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.89‐1.27). The rate of major bleeding was slightly higher in patients treated with enoxaparin (aHR, 1.57; 95% CI, 0.93‐2.66; Tables S4‐S8).

4. DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the largest study comparing the effectiveness and safety of different LMWHs in a real‐world cohort of patients with cancer and VTE. In our cohort, 25% of patients on enoxaparin, 12% on dalteparin, and 14% on tinzaparin were not prescribed full doses, and thus were excluded from the study. Our findings reveal that in real‐life clinical practice, most physicians followed label instructions of dalteparin or tinzaparin to treat their patients, but enoxaparin (which was lacking guidance for the long‐term therapy of VTE in patients with active cancer) was used variably. This is important since LMWHs accounted for >50% of clinical use as long‐term therapy in our study, 14 and around 50% of these patients were prescribed enoxaparin. We also found different treatment regimens adopted by clinicians (once‐daily injection, twice‐daily injections, or switch from initial twice daily to once daily as long‐term therapy). On the contrary, patients receiving dalteparin or tinzaparin had more consistent treatment regimens following their respective labels.

There were unbalanced patient numbers (with a ratio of 4:1 for enoxaparin versus dalteparin or tinzaparin) and unbalanced characteristics at baseline (in the enoxaparin subgroup there was a higher proportion of patients initially presenting with PE, and more proximal DVT). Moreover, patients on enoxaparin were more likely to have been immobilized or to be using corticosteroids or antiplatelet drugs concomitantly. Following multivariable analysis, the risks for VTE recurrences, NMCR bleeding, and death between the two treatment subgroups (enoxaparin vs the other LMWHs) were comparable. There was no statistically significant difference between the subgroups for major bleeding, although there was a tendency to numerically more major bleeds in the enoxaparin subgroup. While an increased risk of major bleeding cannot be excluded based on these study results, there were differences in baseline characteristics between the subgroups that may explain this finding. The variability of the treatment regimens in the enoxaparin subgroup compared with the dalteparin or tinzaparin subgroup should also be taken into consideration, and further analysis regarding regimen variance between subgroups may be required. Importantly, the rate of fatal bleeding risks was comparable between the enoxaparin and dalteparin or tinzaparin subgroups.

While the proportion of patients with hematological malignancies in RIETECAT was small, this is reflective of the real‐life incidence and is also similar to the proportion included across clinical trials with LMWHs. In the Cox proportional model, cancer location (type) was considered as a covariate for data adjustment, and VTE recurrence risk did not differ between patients treated with enoxaparin and those treated with dalteparin or tinzaparin. However, due to the small number of patients in each cancer subgroup, it was not feasible to perform any comparison of effectiveness and safety for each cancer type.

The efficacy and safety of enoxaparin versus VKAs for the long‐term therapy of VTE in patients with cancer have been studied in two randomized controlled trials, which found nonsignificant differences between subgroups. 11 , 12 However, ours is the first study consistently comparing enoxaparin with the other two LMWHs as a subgroup. The incidence rate of VTE recurrences, major bleeding, or death in our cohort was lower than in previous studies. 15 , 16 This is consistent with recent reports that found a progressive improvement in the outcomes of VTE patients, particularly in those with cancer. 17 , 18

The present study has potential limitations. First, given the noninterventional nature of the study, comparability of patients treated with enoxaparin versus dalteparin or tinzaparin may be difficult to achieve. For this reason, we used a multivariable Cox model adjusted by relevant covariables and propensity score matching to minimize the confounding bias (although these could not adjust for unmeasured confounding). Second, data from registries are susceptible to selection bias if a nonrepresentative sample of patients is selected for analysis. However, the RIETE registry captures a broad range of consecutive patients with symptomatic VTE from multiple medical centers, countries, and treatment settings, making it less likely that the study cohort is made up of a skewed population. The primary analysis excluded patients who switched from full‐dose treatment with enoxaparin, dalteparin, or tinzaparin to a non–full‐dose or to another anticoagulant treatment in the first 90 days. Exclusion of patients based on information obtained during follow‐up can introduce bias. 19 A switch in dose or treatment during follow‐up to avoid bleeding complications (eg, following admission to hospital for an invasive diagnostic test, surgical intervention, or other complications) can be indicative of a different bleeding risk at baseline. However, these patients were included in the sensitivity analysis and the results from the 6‐month outcomes and adjusted analyses were similar to those observed in the primary analysis. This multinational study provided real‐world data on the 6 months comparative effectiveness of enoxaparin versus dalteparin or tinzaparin for secondary VTE prevention in patients with active cancer by leveraging existing data. The main strength of our observation is that the population‐based sample we used describes the effects of initial therapy for VTE in “real‐world” clinical care, as opposed to a protocol‐driven randomized trial, and enhances the generalizability of our findings.

To conclude, in RIETECAT, patients with active cancer and acute symptomatic VTE receiving full‐dose enoxaparin had a nonsignificantly lower risk for VTE recurrences, a nonsignificantly higher risk for major bleeding, and similar risks for NMCR bleeding or death over 6 months compared with patients treated with full‐dose dalteparin or tinzaparin.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

JT‐S participated in the design of the study, recruited patients, performed the statistical analyses, and revised the final version of the manuscript. DF‐B, JMP, CG‐G, AB, ABr, IM, AV, and JAP participated in the design of the study, recruited patients, and helped to write the manuscript. MM participated in the design of the study, recruited patients, wrote the manuscript, and obtained funds.

RELATIONSHIP DISCLOSURE

This RIETECAT study was sponsored and funded by Sanofi, but Sanofi did not have any access to the data at any time, nor did they have any influence or implication on the preparation of the manuscript. The manuscript was written, reviewed, and approved by the authors. None of the authors perceived any fee or other forms of compensation for the study or the manuscript.

Supporting information

Fig S1

Fig S2

Table S1‐S8

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We express our gratitude to Sanofi Spain and LEO PHARMA for supporting this registry with an unrestricted educational grant. We also thank the RIETE Registry Coordinating Center, S&H Medical Science Service, for their quality control data, logistic, and administrative support; and Prof. Salvador Ortiz, Universidad Autónoma Madrid, and Silvia Galindo, both statistical advisors in S&H Medical Science Service, for the statistical analysis of the data presented in this paper. The manuscript was written, reviewed, and approved by the authors. Editorial support was provided by Jane Juif and Ann‐Marie Shaw from Lucid Group Communications Ltd, First Floor, Jubilee House, Third Avenue, Globe Park, Marlow, Buckinghamshire, SL7 1EY, UK, and was funded by Sanofi.

Coordinator of the RIETE Registry: Manuel Monreal.

RIETE Steering Committee Members: Paolo Prandoni, Benjamin Brenner, and Dominique Farge‐Bancel.

RIETE National Coordinators: Raquel Barba (Spain), Pierpaolo Di Micco (Italy), Laurent Bertoletti (France), Sebastian Schellong (Germany), Inna Tzoran (Israel), Abilio Reis (Portugal), Marijan Bosevski (R. Macedonia), Henri Bounameaux (Switzerland), Radovan Malý (Czech Republic), Peter Verhamme (Belgium), Joseph A. Caprini (USA), Hanh My Bui (Vietnam).

RIETE Registry Coordinating Center: S & H Medical Science Service.

1. Members of the RIETE Group

SPAIN: MD Adarraga, J Aibar, MA Aibar, C Amado, JI Arcelus, A Asuero, A Ballaz, R Barba, C Barbagelata, M Barrón, B Barrón‐Andrés, A Blanco‐Molina, E Botella, AM Camon, I Casado, J Castro, M Castro, L Chasco, J Criado, C de Ancos, J del Toro, P Demelo‐Rodríguez, AM Díaz‐Brasero, JA Díaz‐Peromingo, MV Di Campli, A Dubois‐Silva, JC Escribano, F Espósito, C Falgá, AI Farfán‐Sedano, C Fernández‐Capitán, JL Fernández‐Reyes, MA Fidalgo, K Flores, C Font, L Font, I Francisco, C Gabara, F Galeano‐Valle, MA García, F García‐Bragado, M García de Herreros, R García de la Garza, C García‐Díaz, R García‐Hernáez, A García‐Raso, A Gil‐Díaz, M Giménez‐Suau, C Gómez‐Cuervo, E Grau, L Guirado, J Gutiérrez, L Hernández‐Blasco, E Hernando, L Jara‐Palomares, MJ Jaras, D Jiménez, R Jiménez, C Jiménez‐Alfaro, MD Joya, S Lainez‐Justo, A Latorre, J Lima, P Llamas, JL Lobo, L López‐Jiménez, P López‐Miguel, JJ López‐Núñez, R López‐Reyes, JB López‐Sáez, A Lorenzo, O Madridano, A Maestre, PJ Marchena, F Martín‐Martos, D Martínez‐Urbistondo, C Mella, MI Mercado, J Moisés, M Monreal, MV Morales, A Muñoz‐Blanco, N Muñoz‐Rivas, MS Navas, JA Nieto, E Nofuentes‐Pérez, MJ Núñez‐Fernández, B Obispo, M Olid, MC Olivares, JL Orcastegui, J Osorio, S Otalora, R Otero, D Paredes, P Parra, JM Pedrajas, G Pellejero, JA Porras, J Portillo, F Rivera‐Civico, DA Rodríguez‐Chiaradía, C Rodríguez‐Matute, J Rogado, V Rosa, P Ruiz‐Artacho, N Ruiz‐Giménez, J Ruiz‐Ruiz, P Ruiz‐Sada, G Salgueiro, R Sánchez‐Martínez, JF Sánchez‐Muñoz‐Torrero, T Sancho, S Soler, B Suárez‐Rodríguez, JM Suriñach, R Tirado, MI Torres, C Tolosa, J Trujillo‐Santos, F Uresandi, B Valero, R Valle, JF Varona, G Vidal, A Villalobos, P Villares, C Zamora, BELGIUM: M Engelen, T Vanassche, P Verhamme, CZECH REPUBLIC: J Hirmerova, R Malý, FRANCE: N Ait Abdallah, L Bertoletti, A Bura‐Riviere, J Catella, F Couturaud, B Crichi, P Debourdeau, O Espitia, N Falvo, D Farge‐Bancel, H Helfer, K Lacut, R Le Mao, I Mahé, F Moustafa, G Poenou, I Quere, GERMANY: S Schellong, ISRAEL: A Braester, B Brenner, I Tzoran, IRAN: R Nikandish, ITALY: F Bilora, B Brandolin, M Ciammaichella, P Di Micco, E Imbalzano, R Maida, F Pace, R Pesavento, P Prandoni, R Quintavalla, A Rocci, C Siniscalchi, A Tufano, A Visonà, B Zalunardo, LATVIA: J Birzulis, A Skride, A Zaicenko, PORTUGAL: S Fonseca, F Martins, J Meireles, REPUBLIC OF MACEDONIA: M Bosevski, SWITZERLAND: H Bounameaux, L Mazzolai, USA: CI Ochoa‐Chaar, I Weinberg, VIETNAM: HM Bui.

Trujillo‐Santos J, Farge‐Bancel D, Pedrajas JM, et al; The RIETE Investigators . Enoxaparin versus dalteparin or tinzaparin in patients with cancer and venous thromboembolism: The RIETECAT study. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2022;6:e12736. doi: 10.1002/rth2.12736

A full list of the RIETE investigators is given in the Appendix A1.

Handling Editor: Dr Suzanne Cannegieter

Contributor Information

Aitor Ballaz, @AitorBallaz.

Isabelle Mahé, @isabellemahe1.

Manuel Monreal, Email: manuelmonrealbosch@gmail.com, @mmonrealriete.

The RIETE Investigators:

MD Adarraga, J Aibar, MA Aibar, C Amado, JI Arcelus, A Asuero, R Barba, C Barbagelata, M Barrón, B Barrón‐Andrés, A Blanco‐Molina, E Botella, AM Camon, I Casado, J Castro, M Castro, L Chasco, J Criado, C de Ancos, J del Toro, P Demelo‐Rodríguez, AM Díaz‐Brasero, JA Díaz‐Peromingo, MV Di Campli, A Dubois‐Silva, JC Escribano, F Espósito, C Falgá, AI Farfán‐Sedano, C Fernández‐Capitán, JL Fernández‐Reyes, MA Fidalgo, K Flores, C Font, L Font, I Francisco, C Gabara, F Galeano‐Valle, MA García, F García‐Bragado, M García de Herreros, R García de la Garza, C García‐Díaz, R García‐Hernáez, A García‐Raso, A Gil‐Díaz, M Giménez‐Suau, E Grau, L Guirado, J Gutiérrez, L Hernández‐Blasco, E Hernando, L Jara‐Palomares, MJ Jaras, D Jiménez, R Jiménez, C Jiménez‐Alfaro, MD Joya, S Lainez‐Justo, A Latorre, J Lima, P Llamas, JL Lobo, L López‐Jiménez, P López‐Miguel, JJ López‐Núñez, R López‐Reyes, JB López‐Sáez, A Lorenzo, O Madridano, A Maestre, PJ Marchena, F Martín‐Martos, D Martínez‐Urbistondo, C Mella, MI Mercado, J Moisés, MV Morales, A Muñoz‐Blanco, N Muñoz‐Rivas, MS Navas, JA Nieto, E Nofuentes‐Pérez, MJ Núñez‐Fernández, B Obispo, M Olid, MC Olivares, JL Orcastegui, J Osorio, S Otalora, R Otero, D Paredes, P Parra, G Pellejero, J Portillo, F Rivera‐Civico, DA Rodríguez‐Chiaradía, C Rodríguez‐Matute, J Rogado, V Rosa, P Ruiz‐Artacho, N Ruiz‐Giménez, J Ruiz‐Ruiz, P Ruiz‐Sada, G Salgueiro, R Sánchez‐Martínez, JF Sánchez‐Muñoz‐Torrero, T Sancho, S Soler, B Suárez‐Rodríguez, JM Suriñach, R Tirado, MI Torres, C Tolosa, F Uresandi, B Valero, R Valle, JF Varona, G Vidal, P Villares, C Zamora, M Engelen, T Vanassche, P Verhamme, J Hirmerova, R Malý, N Ait Abdallah, L Bertoletti, A Bura‐Riviere, J Catella, F Couturaud, B Crichi, P Debourdeau, O Espitia, N Falvo, H Helfer, K Lacut, R Le Mao, F Moustafa, G Poenou, I Quere, S Schellong, B Brenner, I Tzoran, R Nikandish, F Bilora, B Brandolin, M Ciammaichella, P Di Micco, E Imbalzano, R Maida, F Pace, R Pesavento, P Prandoni, R Quintavalla, A Rocci, C Siniscalchi, A Tufano, A Visonà, B Zalunardo, J Birzulis, A Skride, A Zaicenko, S Fonseca, F Martins, J Meireles, M Bosevski, H Bounameaux, L Mazzolai, CI Ochoa‐Chaar, I Weinberg, and HM Bui

REFERENCES

- 1. Khorana AA. Venous thromboembolism and prognosis in cancer. Thromb Res. 2010;125:490‐493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Monreal M, Falga C, Valdes M, et al. Fatal pulmonary embolism and fatal bleeding in cancer patients with venous thromboembolism: findings from the RIETE registry. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:1950‐1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Trujillo‐Santos J, Nieto J, Tiberio G, et al. Predicting recurrences or major bleeding in cancer patients with venous thromboembolism. Findings from the RIETE registry. Thromb Haemost. 2008;100:435‐439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chee CE, Ashrani AA, Marks RS, et al. Predictors of venous thromboembolism recurrence and bleeding among active cancer patients: a population‐based cohort study. Blood. 2014;123:3972‐3978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Farge D, Trujillo‐Santos J, Debourdeau P, et al. Fatal events in cancer patients receiving anticoagulant therapy for venous thromboembolism. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(32):e1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fuentes HE, Tafur AJ, Caprini JA, et al. Prediction of early mortality in patients with cancer‐associated thrombosis in the RIETE database. Int Angiol. 2019;38:173‐184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: chest guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2016;149:315‐352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Watson HG, Keeling DM, Laffan M, Tait RC, Makris M, British Committee for Standards in Haematology . Guideline on aspects of cancer‐related venous thrombosis. Br J Haematol. 2015;170:640‐648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Farge D, Bounameaux H, Brenner B, et al. International clinical practice guidelines including guidance for direct oral anticoagulants in the treatment and prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(10):e452‐e466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lyman GH, Bohlke K, Khorana AA, et al. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis and treatment in patients with cancer. American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline update 2014. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(6):654‐656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Meyer G, Marjanovic Z, Valcke J, et al. Comparison of low‐molecular‐weight heparin and warfarin for the secondary prevention of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer: a randomized controlled study. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1729‐1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Deitcher SR, Kessler CM, Merliet G, et al. Secondary prevention of venous thromboembolic events in patients with active cancer: enoxaparin alone versus initial enoxaparin followed by warfarin for a 180‐day period. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2006;12:389‐396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bikdeli B, Jimenez D, Hawkins M, et al. Rationale, design and methodology of the computerized registry of patients with venous thromboembolism (RIETE). Thromb Haemost. 2018;118:214‐224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mahé I, Sterpu R, Bertoletti L, et al. Long‐term anticoagulant therapy of patients with venous thrombo‐embolism. What are the practices? PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0128741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lee AYY, Levine MN, Baker RI, et al. Low‐molecular‐weight heparin versus a coumarin for the prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:146‐153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lee AYY, Bauersachs R, Janas MS, et al. CATCH: a randomised clinical trial comparing long‐term tinzaparin versus warfarin for treatment of acute venous thromboembolism in cancer patients. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jiménez D, de Miguel‐Díez J, Guijarro R, et al. Trends in the management and outcomes of acute pulmonary embolism. Analysis from the RIETE registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:162‐170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Morillo R, Jiménez D, Aibar MA, et al. DVT management and outcome trends, 2001 to 2014. Chest. 2016;150:374‐383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hernán MA, Sauer BC, Hernández‐Díaz S, Platt R, Shrier I. Specifying a target trial prevents immortal time bias and other self‐inflicted injuries in observational analyses. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;79:70‐75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig S1

Fig S2

Table S1‐S8