Abstract

Background

As transcription factors, the TCP genes are considered to be promising targets for crop enhancement for their responses to abiotic stresses. However, information on the systematic characterization and functional expression profiles under abiotic stress of TCPs in Tartary buckwheat (Fagopyrum tataricum (L.) Gaertn.) is limited.

Results

In this study, we identified 26 FtTCPs and named them according to their position on the chromosomes. Phylogenetic tree, gene structure, duplication events, and cis-acting elements were further studied and syntenic analysis was conducted to explore the bioinformatic traits of the FtTCP gene family. Subsequently, 12 FtTCP genes were selected for expression analysis under cold, dark, heat, salt, UV, and waterlogging (WL) treatments by qRT-PCR. The spatio-temporal specificity, correlation analysis of gene expression levels and interaction network prediction revealed the potential function of FtTCP15 and FtTCP18 in response to abiotic stresses. Moreover, subcellular localization confirmed that FtTCP15 and FtTCP18 localized in the nucleus function as transcription factors.

Conclusions

In this research, 26 TCP genes were identified in Tartary buckwheat, and their structures and functions have been systematically explored. Our results reveal that the FtTCP15 and FtTCP18 have special cis-elements in response to abiotic stress and conserved nature in evolution, indicating they could be promising candidates for further functional verification under multiple abiotic stresses.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12864-022-08618-1.

Keywords: TCP transcription factor, Abiotic stress, Tartary buckwheat, FtTCP15, FtTCP18

Background

Transcription factors usually contain DNA-binding domains, transcription regulation domains, oligomerization sites and nuclear localization signals. Some domains are used to bind DNA, and some are used to activate transcription [1]. A total of 58 transcription factor families have been identified from 156 plant genome sequences [2]. Many studies have shown that identifying key transcription factors provides new insights into how plants respond to abiotic stresses at the cellular and molecular levels [3–8]. Abiotic stress factors or their different combinations can affect the yield and quality of crops on cultivated land worldwide by influencing physiological and biochemical processes within the plant [9–11]. In consideration of global climate change, transcription factors are promising targets for crop enhancement because they are key regulatory switches that control gene expression in various organic and metabolic processes [12].

The transcription factor TCP gene family was originally identified and named based on the characteristics of the first three family members of Zea mays (L.) Sp. (TB1), Antirrhinum majus L. (CYC), and Oryza sativa L. (PCF) [13]. The TCP gene family contains highly conserved and non-canonical TCP domains with a basic helix-loop-helix structure. These domains play a role in protein-protein dimerization and DNA binding [14, 15]. The TCP family is plant-specific and can regulate plant growth, including seed germination and seedling establishment [6], spikelet meristem [16], and branching [17]. Online interaction network prediction shows that the TCP gene family also participates in regulating and synthesizing numerous protein complexes involved in various biological processes such as plant hormone pathways, cell life cycles, and environmental stress responses [18]. Many studies have confirmed that the TCP family is involved in plant responses to abiotic stresses. When the OsTCP19 gene is over-expressed in Arabidopsis, it can enhance plant tolerance to drought and heat during seedling and maturity stages [19]. Additionally, down-regulation of AsTCP14 in the Creeping bentgrass (Agrostis stolonifera L.) can improve plant resistance to drought and salt stresses [20]. TCP transcription factors inhibit the formation of trichomes on the side of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh.) cotyledon, thus affecting the barrier function of these trichomes against biotic and abiotic stresses on the plant [21].

Buckwheat is a pseudo-cereal crop with a long cultivation history and incomparable nutritional characteristics and is one of the potential research objects to realize the diversification of food resources [22–24]. Buckwheat is cultivated and consumed worldwide and has received widespread attention for its synthesis by many substances with health functions and active medicinal ingredients [24–26]. The buckwheat is usually planted in habitats with low rainfall, low temperatures, and high altitudes [27, 28]. In addition, sufficient light and ultraviolet radiation, for example, high UV-B doses, can affectthe physiological and biochemical processes of plants [29–31], contributing to unusual energy conversion efficiency and plant tissue function [32].To sum up, the growth, yield, and quality of buckwheat are severely threatened by abiotic stress factors or their combinations. To date, many transcription factors in Tartary buckwheat have been well-studied. Some of these transcription factors have been identified to be associated with Al stress [33] and salt stress [34]. However, information on the identification, expression analysis, and potential functions under abiotic stresses of TCP transcription factors in Tartary buckwheat is limited.

In this study, the genome-wide identification of 26 TCPs in Tartary buckwheat (Fagopyrum tataricum (L.) Gaertn.) was carried out. Subsequently, FtTCP15 and FtTCP18 were compared with other members of the FtTCP gene family in terms of evolutionary relationship, gene structure, conservative motifs, and cis-acting elements. Next, expression profiles of selected 12 FtTCP genes under multiple abiotic stresses, including cold, dark, heat, salt, UV, and waterlogging (WL), were analyzed by qRT-PCR, FtTCP15 and FtTCP18 were found to be highly expressed under multiple treatments. Correlation coefficient analysis of gene expression levels, tissue-specific expression, and interaction network prediction was conducted. Then, subcellular localization through laboratory methods demonstrated that both FtTCP15 and FtTCP18 were localized in the nucleus. Our work provides a comprehensive framework for how FtTCPs respond to abiotic stresses and affords valuable clues for further functional verification of FtTCP15 and FtTCP18 as transcription factors in Tartary buckwheat to improve the adaptability under multiple abiotic stresses.

Results

The 26 FtTCP genes identified in the Tartary buckwheat genome are unevenly distributed on 8 chromosomes

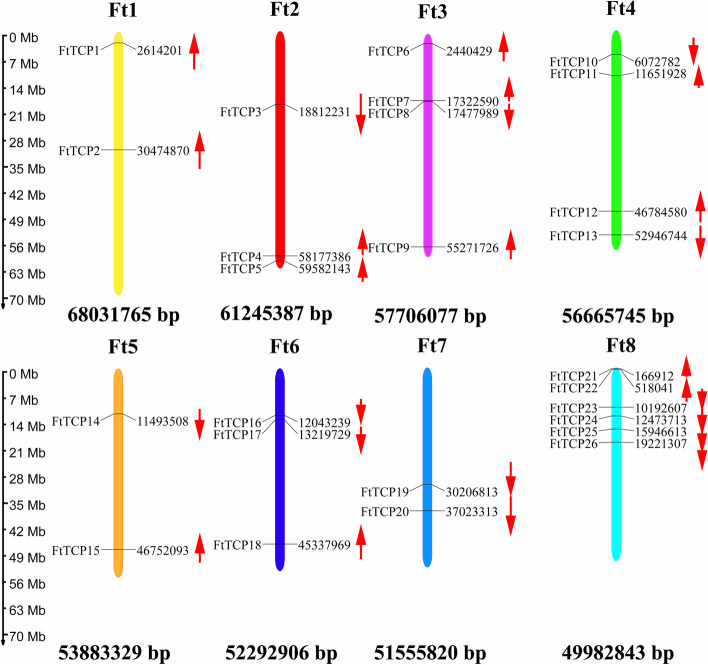

In this paper, 26 FtTCPs from the Tartary buckwheat genome were identified and named from FtTCP1 to FtTCP26 according to their position on the chromosome (Fig. 1). The distribution and arrangement information of genes on chromosomes in the latest Tartary buckwheat gene bank were used for chromosome distribution maps. Figure 1 shows that the 26 FtTCP genes of Tartary buckwheat are unevenly distributed on 8 chromosomes, with 2 to 6 genes on each chromosome. The Ft8 has the largest number of FtTCP genes (6 genes), while Ft1, Ft5, and Ft7 have the least number of FtTCP genes (2 genes). There are 3 genes on Ft2 and Ft6, and 4 genes on chromosomes Ft3 and Ft4. Additionally, the two genes on Ft1 are on the reverse chain, and both the two genes on Ft7 are on the forward chain. The genes on the remaining chromosomes are also in forward or reverse chains.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representations of the chromosomal distribution of the 26 TCPs in Tartary buckwheat. The position of the gene on the chromosome and the corresponding base pair position are marked on the left and right sides. The chromosome number and chromosome full-length base pair are labeled above and below each chromosome. The upward red arrow indicates that the gene has a reverse chain on the chromosome, and the downward red arrow indicates that the gene has a forward chain on the chromosome

Table S1 shows detailed information about these FtTCPs, including the gene name, sequence ID, group, length of protein (PL), molecular weight (MW), the isoelectric point (pI), genome location, and predicted subcellular location (W). The length of the identified FtTCP gene-encoded proteins ranges from 176 aa (FtTCP2) to 475 aa (FtTCP3), with an average of 285.8 aa. The range of MW is from 19.17 kDa (FtTCP2) to 51.04 kDa (FtTCP3), with an average of 31.09 kDa. The theoretical pI also differs greatly from 4.93 (FtTCP20) to 9.71 (FtTCP19) with an average of 7.05. According to the subcellular localization prediction, 21 FtTCP genes have the highest probability of being in the nucleus, and 5 FtTCP members are only located in the nucleus. Additionally, the group and chromosome location of the identified FtTCP genes were provided.

The phylogenic relationship and conserved features predict the potential functions of FtTCP15 and FtTCP18

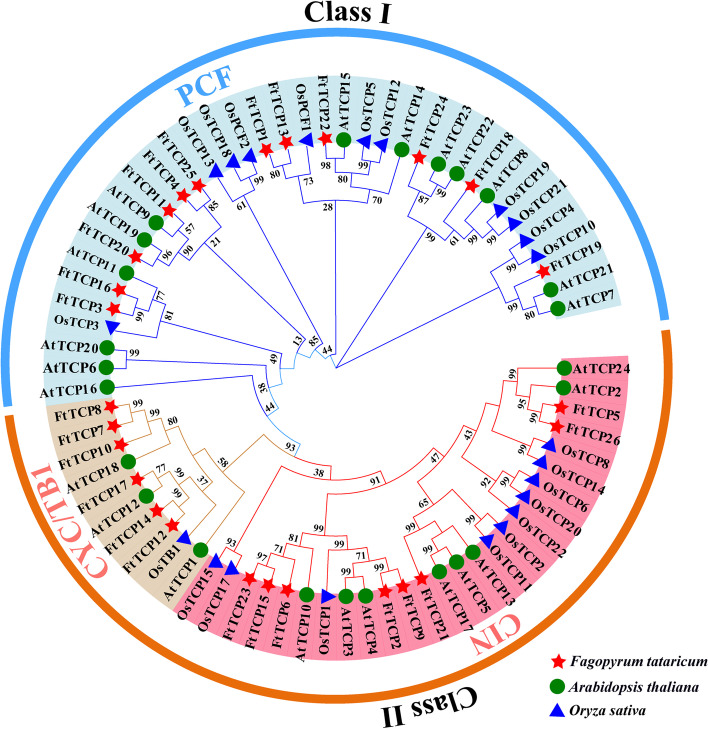

In order to understand the phylogenetic relationship among TCP genes of Tartary buckwheat, Arabidopsis, and rice, the full-length sequence of TCP proteins with known functions was selected to draw a rootless phylogenetic tree (Fig. 2). The numbers of proteins from Tartary buckwheat (FtTCP), Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh.) (AtTCP), and rice (Oryza sativa L.) (OsTCP) were 26, 24, and 22, respectively. The names used for the AtTCP in Arabidopsis and OsTCP in rice were based on the previous study [35]. The result shows that all 72 TCP members are classified into Class I and Class II subfamilies. Class I contains the PCF group, and Class II contains two subclades (CYC/TB1 and CIN). The phylogenetic tree shows that 36 TCPs belong to the PCF clade, 26 to CIN, and 10 to CYC/TB1. The results show that AtTCPs and OsTCPs in the phylogenetic tree fall into the same Class or subclade consistent with the finding in the previous study [35]. All the 26 FtTCPs are classified into three clades, with 12, 6, and 8 in PCF, CYC/TB1 and CIN, respectively. The distribution of the TCP genes in each subfamily is random and uniform. For example, there is only 1 from rice, 6 from Tartary buckwheat, and 3 from Arabidopsis among the 10 CYC/TB1 TCP genes.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of TCP proteins among Arabidopsis thaliana, rice, and Tartary buckwheat. The phylogenetic tree was constructed with the MEGA 7.0 Software, using parameters as bootstrap values (1000 replicates) and the Poisson model. The numbers on each branch line represent bootstrap values. All the TCPs are divided into three groups: PCF (belonging to Class I), CIN and CYC/TB1 (belonging to Class II). Tartary buckwheat is shown with red five-pointed star icons, Arabidopsis thaliana is shown with green circle icons, and rice is shown with blue triangle icons

As shown in Fig. 2, most Arabidopsis class II TCP genes (in the CYC/TB1 group) have one or more counterparts in Tartary buckwheat and rice. OsTCP1, FtTCP12, and FtTCP14 correspond to AtTCP1. FtTCP17 correspond to AtTCP12. FtTCP10, FtTCP7, and FtTCP8 correspond to AtTCP18. FtTCP6, FtTCP15, and FtTCP23 correspond to AtTCP10. However, AtTCP6, AtTCP16, and AtTCP20 have a separation position with no close homology in Tartary buckwheat, implying a lineage-specific gene loss in Tartary buckwheat. A similar result of AtTCP16 was also observed in petunia [36] and tomatoes [37]. In particular, FtTCP15 and FtTCP23 are isolated from each other, and their evolutionary relationships are closely related to FtTCP6 and AtTCP10. In contrast, FtTCP18 is closely related to AtTCP8, OsTCP19, and OsTCP21, indicating that these genes in the same cluster may have similar functions in response to abiotic stresses. Therefore, FtTCP15 and FtTCP18 may have the same function as AtTCP10 and OsTCP19.

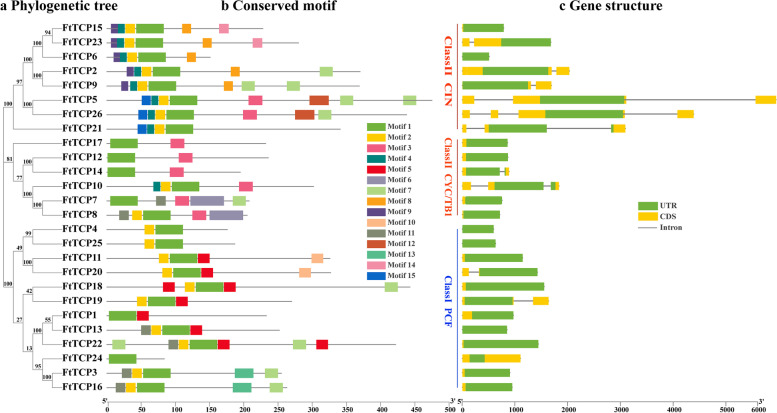

As shown in Fig. 3, the structural features and conserved motifs have been performed to further study TCP genes. The analysis provides a reference to analyze the evolutionary relationship and the structural diversity of members in each subfamily and to fully understand conserved motifs and gene structure of the TCP family. As shown in Fig. 3b, there are 15 conserved motifs (motif 1-motif 15) of the FtTCP protein predicted by the online MEME analysis tool. The different colored boxes in the legend correspond to distinct motifs. The logo and name of the query motifs are displayed in Table S2. Motif 1 and Motif 2 are present in nearly all FtTCP proteins and Motif 1 is included in every protein. However, other motifs exist in less than half of the proteins. Many motifs, such as motifs 6, 9, 14, and 15, shared by the class II (CYC/TB1 and CIN) TCP family, are restricted to specific groups. The CIN group genes only share the last three motifs. Additionally, Motif 13 only exist in FtTCP3 and FtTCP16 (belonging to PCF Group), and Motif 6 is only found in FtTCP7 and FtTCP8 (belong to CYC/TB1). FtTCP24 only has Motif 1.

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic relationship, gene structure, and architecture of conserved protein motifs in TCP genes from Tartary buckwheat. a The phylogenetic tree is constructed based on the full-length sequences of Tartary buckwheat TCP proteins using Geneious R11 software. b Amino acid motifs in the Tartary buckwheat are represented by 15 colored boxes, and the relative protein lengths are indicated by black lines. c The exon–intron structure of Tartary buckwheat TCP genes. Exons, introns, and untranslated regions (UTRs) are indicated by blue rectangles, black lines, and green rectangles, respectively. The unit of the bottom ruler is bp

The structural features of the FtTCP gene family, including the arrangement and quantity characteristics of exons and introns, are shown in Fig. 3c. Gene family members belonging to the same clade have similar numbers and organization of exons/introns. The gene structure of the FtTCP family is characterized by a small number of introns. There are 16 TCP gene CDS with no introns (account for 62%). Most of them are from Class I (PCF), and 6 members (FtTCP6, FtTCP7, FtTCP8, FtTCP12, FtTCP15, and FtTCP17) are from Class II. Among the remaining 10 genes with introns, 8 belong to Class II (6 belong to CIN Group, 2 belong to CYC/TB1 Group). The CIN group contains the most members of introns compared with the other two groups. The FtTCP5 belonging to CIN has the longest exon. Moreover, the number of introns contained in the remaining 10 genes ranges from 1 to 3, indicating little difference among these members. A total of 22 FtTCP members contain exons, accounting for 84%. The genes with exons in the Arabidopsis TCP family account for about 82% [35]. The results indicate that buckwheat and Arabidopsis have similar gene conservatism. Both FtTCP15 and FtTCP18 have no introns, indicating that they are highly conservative in response to abiotic stress. FtTCP15 contains Motifs 1, 2, 8, 9, 14, 15; FtTCP15 contains 2 Motif 5, and Motifs 1, 2, 7. Their specific conserved motifs can be used as the targets for further studies on the molecular mechanisms related to the stress response.

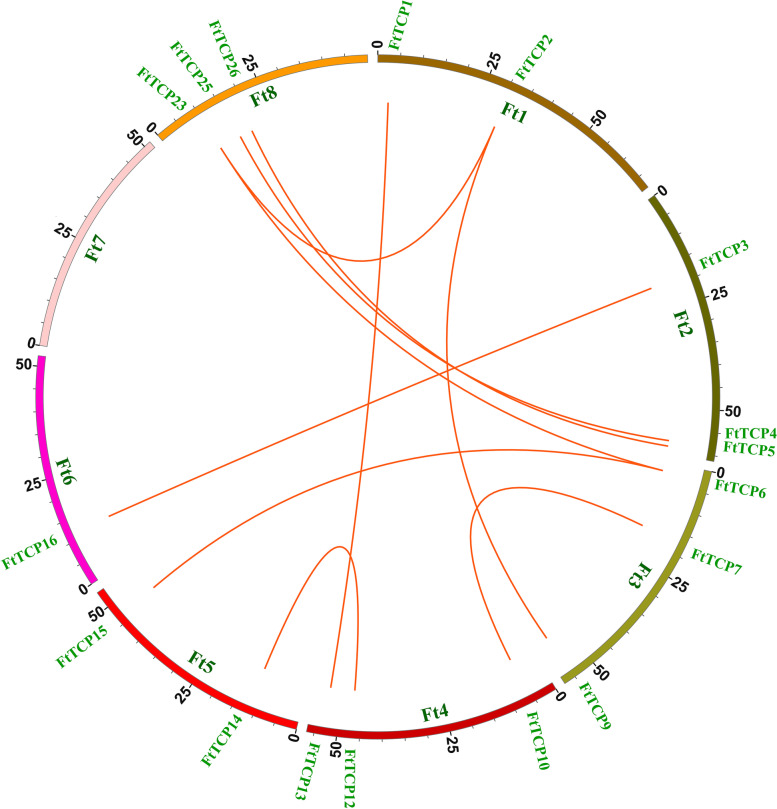

Segmental duplications are the main force in the molecular evolution of FtTCP gene amplification

Gene duplication is the main force that promotes the amplification of gene families and generates new functions of genes. The analysis of replication events (Fig. 4) shows that only segmental duplication events happen in the FtTCP gene family of the Tartary buckwheat genome, and there are no tandem duplication events. As shown in Fig. 4, there are 10 pairs of segment duplication events in the FtTCP gene family. Ft8 and Ft3 have 4 segmental duplication gene pairs. There are 3 segmental duplication gene pairs that occur on Ft1, Ft2, and Ft4, simultaneously. The remaining Ft5 and Ft6 have 2 and 1 segmental duplication gene pairs, respectively. However, no segmental duplication gene pairs occur on the Ft7. As for the subfamily, there are 6 repeated events in Class I (PCF) subfamily. A total of 10 segmental duplication events occurred in CIN subfamily with the highest number, and 4 segmental duplication events occurred in the CYC/TB1 subfamily. There are 14 segmental duplications events in Class II (CIN and CYC/TB1) in all. Segment duplication events can promote the evolution of the FtTCP gene family. Intraspecific collinearity was found between FtTCP15 and FtTCP6, but no intraspecific collinearity was found for FtTCP18.

Fig. 4.

Schematic representations of the chromosomal distribution and intrachromosomal relationships of TCP genes in Tartary buckwheat. Colored lines indicate duplicated TCP gene pairs in the Tartary buckwheat genome. The chromosome number is indicated along each chromosome

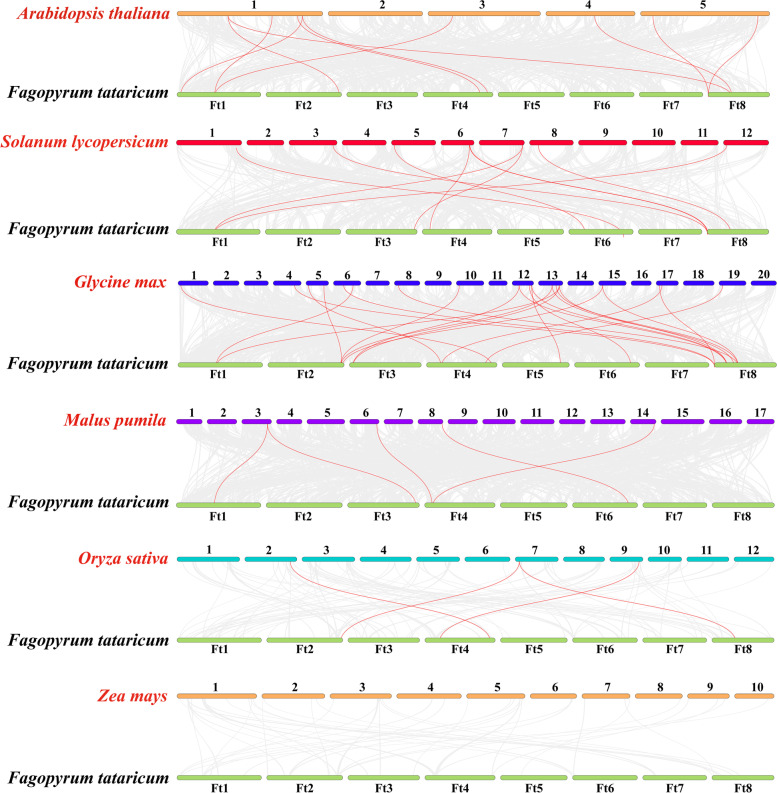

In order to further explore the interspecific collinearity of the TCP gene family between Tartary buckwheat and other species, a comparison system diagram between Tartary buckwheat and other six plants was constructed (Fig. 5). The six plants are Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh.), apple (Malus pumila L.), soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.), rice (Oryza sativa L.), maize (Zea mays (L.) Sp.), and tomato (Solanum lycopersicum (L.) Mill.). The collinearity relationship among TCP genes in different plants is shown in Fig. 5. The FtTCP genes have different degrees of collinear relationship with other plants. Soybean has the most homologous pairs, with 24 pairs, followed by Arabidopsis, tomato, apple, and rice, with 10, 9, 5, and 4 homologous pairs, respectively. There is no syntenic relationship between the Tartary buckwheat and Zea mays (L.) Sp.. There are 2 orthologous gene pairs between soybean and Tartary buckwheat distributed on Ft1 (FtTCP2), 4 on Ft2 (3 pairs on FtTCP4; 1 pair on FtTCP5), 3 on Ft3, 4 on Ft4, 1 on Ft5 and Ft6, and 10 on Ft8. The Ft4 chromosome of selected plants, except the Zea mays (L.) Sp., contains one or more gene pairs.

Fig. 5.

Syntenic analysis of the TCP genes between Tartary buckwheat and six representative plants. Gray lines in the background indicate col-linear blocks within Tartary buckwheat and other plant genomes, while red lines highlight synthetic TCP gene pairs. The chromosome number is indicated above or below each chromosome

Furthermore, some genes have more than one pair of collinearity, indicating their important role in evolution. For example, FtTCP2 (classified into the CIN group) in Tartary buckwheat has two homologous gene pairs with Arabidopsis, tomato, and soybean. The synteny analysis between soybean and Tartary buckwheat reveals that 16 out of 24 orthologous gene pairs are classified into the CIN group, 7 are classified into the PCF group, and only 1 belongs to CYC/TB1. Additionally, the FtTCP15 located on Ft5 has only one interspecific collinearity gene pair with soybean, and FtTCP18 located on Ft6 has one pair with tomato, soybean, and apple, respectively, suggesting that they are relatively conservative during evolution.

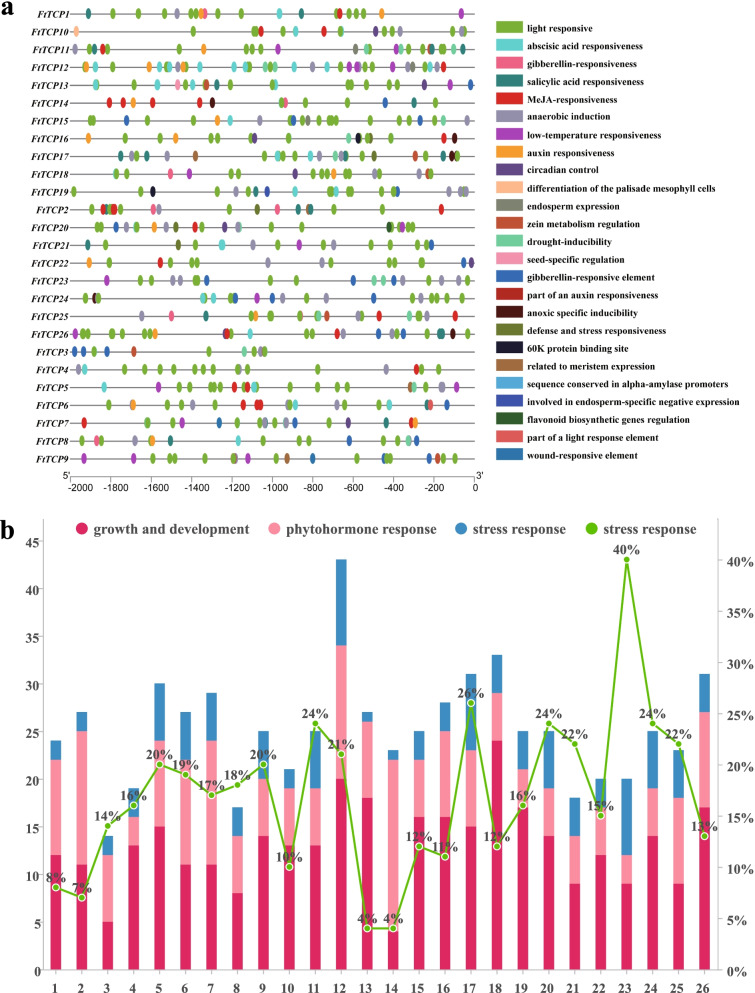

Analysis of cis-acting elements of FtTCPs reflects their potential function in stress response

Cis-acting elements refer to specific DNA sequences in series with structural genes and bind sites for transcription factors. Cis-acting elements regulate the precise initiation and transcription efficiency of gene transcription by binding to transcription factors. In this work, an upstream 2000 bp region was selected to analyze the cis-elements of the FtTCP genome sequence (Fig. 6; Table S3; Table S4).

Fig. 6.

Predicted cis-elements in the promoter regions of the Tartary buckwheat. a The sequences within 2000 bp upstream of the TCP genes are analyzed. The scale bar at the bottom indicates sequence length. Different cis-elements are labeled by rectangles with different colors based on the legend at the bottom. b Promoters are divided into three categories: growth and development, phytohormone response, and stress response. The bar graphs represent the number of the three types in each gene. Red represents growth and development, pink represents phytohormone response, and blue represents stress response. The green broken line graph represents the percentage of stress response in each gene

The results show that the cis-acting elements concerning growth and development are the most (328, about 51%). The light-responsive elements (G-box: TACGTG; GT1-motif: GGTTAA; ATC-motif: AGC-TATCCA; AE-box: AGAAACAA; Box 4: ATTAAT; et.al.) are the most in each gene. There are 296 light-responsive elements, accounting for 46%. There are many kinds of elements related to phytohormone response, such as ABRE (ACGTG; CGTACGTGCA), abscisic acid (ABA) (65 in total), Me-JA (CGTCA-motif; TGACG-motif) (60 in total), gibberellin (TATC-box: TATCCCA) (35 in total), and auxin (Aux RR-core: GGTCCAT) (18 in total), which respond to the stress after being induced by adversity factors [38, 39]. At last, multiple abiotic stress-related promoters were explored, such as those with anaerobic induction (ARE: AAACCA) (61 in all genes), anoxic specific inducibility (GC-motif: CCCCCG) (6 in all genes), low-temperature responsiveness (LTR: CCGAAA) (19 in all genes), drought-inducibility (MBS: CAACTG) (17 in total), stress responsiveness (TC-rich repeats: ATTCTCTAAC) (6 in total), and wound-responsiveness (WUN-motif: AAATTTCCT) (2 in total). The sum of stress-related promoters is 105 (about 17%) (Table S4). It is assumed that these two factors (anaerobic induction and anoxic specific inducibility) are important for the response to abiotic stress. All FtTCPs are found to have light-responsive elements, and FtTCP15 and FtTCP18 have 15 and 11 light-responsive cis-elements, respectively (Table S4). Most cis-elements of FtTCP15 and FtTCP18 are related to growth and development.

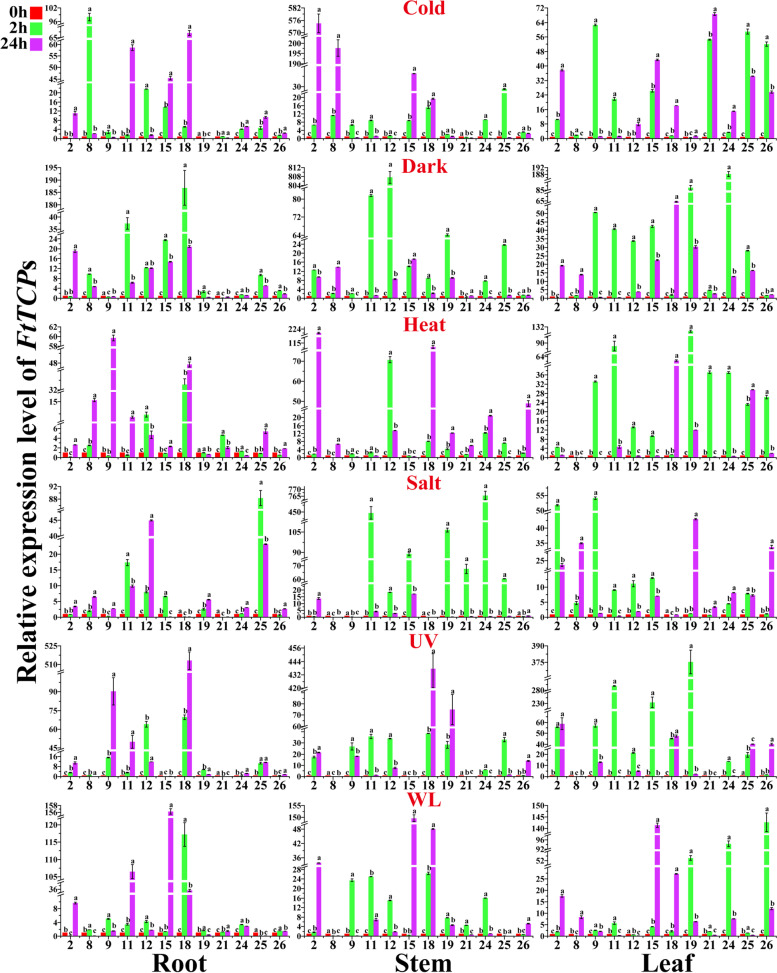

The response of the FtTCP family to abiotic stress is spatio-temporal, and the interaction network is predicted

A total of 12 FtTCPs were selected randomly for expression analysis under multiple abiotic stresses, including cold, dark, heat, salt, UV, and WL. A histogram of the expression of these genes in different tissues after stress at different time points was drawn, and correlation analysis was performed. As shown in Fig. 7 and Figure S1, the expression patterns of FtTCPs under different abiotic stress conditions have time and space specificity, and many genes have obvious up-regulation or down-regulation trends.

Fig. 7.

Gene expression profiles of the TCP gene family in Tartary buckwheat under different treatments. The abiotic stress including Cold, Dark, Heat, Salt, UV, and Waterlogging (WL) stress. The plant samples were collected in the six-week-old Tartary buckwheat seedling stage, after being treated for 2 and 24 h under every treatment. Data represent means (± SE) of three biological replicates. Vertical bars indicate standard deviations. The legend in the upper left corner of the image shows the processing time in different colors (0 h, 2 h, 24 h). Different letters (a, b, c) indicate significant differences in terms of different times using Duncan's multiple range test (P < 0.05; n = 3) by SPSS. The number on the horizontal axis represents the corresponding gene name, for example, 2 represents FtTCP2. The chart is constructed by the Origin 8.0 software

FtTCP11 (24 h, root), FtTCP15 (24 h, root, stem, leaf), FtTCP18 (2 h, root, stem), FtTCP24 (2 h, leaf), and FtTCP26 (2 h, leaf) were significantly up-regulated in WL treatment. Expression levels of FtTCP18 (24 h, root, stem), FtTCP11 (2 h, leaf), FtTCP15 (2 h, leaf), and FtTCP19 (2 h, leaf) were increased significantly in the UV environment. Expressions of FtTCP11 (2 h, stem), FtTCP24 (2 h, stem) and FtTCP25 (2 h, root) were significantly up-regulated in the salt environment. Additionally, FtTCP2 (24 h, stem) was up-regulated under cold and heat stress treatments. FtTCP8 (24 h, stem) was also up-regulated in cold treatment. In summary, 4 FtTCPs (FtTCP11, FtTCP15, FtTCP18, and FtTCP26), 4 FtTCPs (FtTCP11, FtTCP15, FtTCP18, and FtTCP19), 3 FtTCPs (FtTCP11, FtTCP24, and FtTCP25), 2 FtTCPs (FtTCP12 and FtTCP18), 2 FtTCPs (FtTCP2 and FtTCP8), and 3 FtTCPs (FtTCP2, FtTCP18, and FtTCP19) were restricted by WL, UV, salt, dark, cold, and heat stresses, respectively. Among them, 5 FtTCPs (FtTCP8, FtTCP12, FtTCP24, FtTCP25, and FtTCP26) were activated by the specific stress. Several genes were significantly up-regulated in different stress environments at two time points of stress and in three different tissues. The expression profiles of the selected genes under abiotic stress revealed that FtTCP18 was generally responsive to different abiotic stresses, and FtTCP15 was responsive to WL, UV, and salt stress. We are interested in exploring the molecular mechanisms of FtTCP15 and FtTCP18 in response to abiotic stresses. Therefore, we conducted a comprehensive study on the evolution of the FtTCP gene family to explore the particularity of FtTCP15 and FtTCP18.

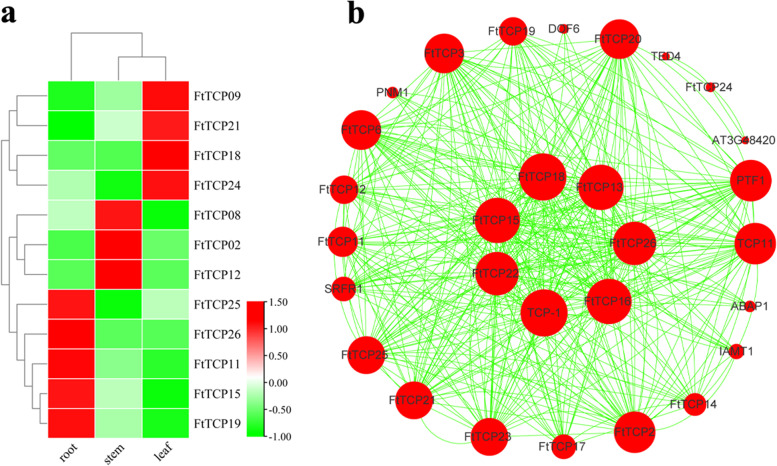

The correlation analysis of gene expression under different abiotic stress conditions (Figure S1) demonstrates that the maximum correlation coefficient is 0.81 (between FtTCP2 and FtTCP8), and the minimum is -0.09 (between FtTCP8 and FtTCP9). These correlation coefficients prove that these genes have a certain connection when performing their functions. FtTCP15 and FtTCP18 are representatives in expression profile analysis under several stresses. A basic overview of multiple potential regulatory mechanisms of FtTCPs can be obtained through various expression patterns in different organizations. In addition, tissue-specific expression analysis of the selected genes in Tartary buckwheat was conducted in the seedling stage (six-week-old) under natural conditions. As shown in Fig. 8a, TCP genes of Class I are highly expressed in the leaf and root. For example, FtTCP18 and FtTCP24 are highly expressed in the leaf, while FtTCP11 and FtTCP19 are highly expressed in the root. The genes from Class II are expressed in all tissues. A particular concern is that FtTCP15 is highly expressed in the root, while the FtTCP18 is highly expressed in the leaf, indicating their different functions in responding to stresses in different tissues.

Fig. 8.

Tissue-specific expression patterns and prediction of interaction network of FtTCPs. a Tissue-specific expression pattern of 12 selected FtTCPs in Tartary buckwheat at the six-week-old seedling stage under natural conditions. The tissues include the root, stem, and leaf. One expression value is shown for each gene in different tissues under natural conditions. The values represent the average expression value of three replicates. b Prediction of interaction network among TCP genes. The green line indicates the interaction relationship between genes. The red circle represents the gene that interacts with other TCPs. The size of the circle represents the number of interaction relationships. Greater circles size, mean more interaction times

Interaction network prediction is significant for studying the function of genes. Interaction prediction data were obtained from STRING (https://string-db.org/) and visualized using Cytoscape software (Table S5; Table S6). As shown in Fig. 8b, the size of the red circle can intuitively represent interaction times between proteins. The FtTCP24 alone interacts with the TBD4 and AT3G48420, indicating that FtTCP24 may have a different function. FtTCP15 and FtTCP18 interact with multiple proteins in the interaction network, and the number of FtTCP15 and FtTCP18 interacting with other proteins is 41 and 44, respectively (Table S6).

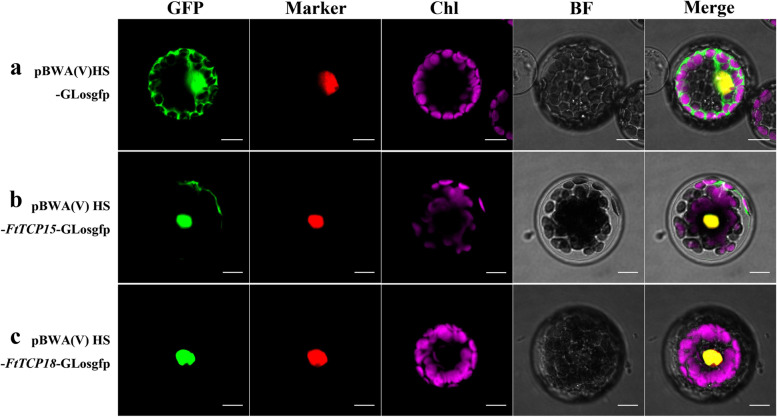

Subcellular localization showed that FtTCP15 and FtTCP18 localized in the nucleus

Transcription factors can regulate the transcription process of genes in the nucleus. To a certain extent, transcription factors can be determined by their subcellular localization. Figure 9 shows the subcellular localization analysis of the FtTCP15 and FtTCP18. It is found that both FtTCP15 and FtTCP18 can be localized in the nucleus, which is consistent with the general understanding of the properties of transcription factors [40]. FtTCP15 also shows weak fluorescence signals in the cytoplasm, suggesting many exceptional cases for subcellular localization of transcription factors.

Fig. 9.

Subcellular localization analysis of FtTCP15 and FtTCP18. a Localization results of pBWA(V)HS-GLosgfp empty plasmid as the control. b Colocalization of pBWA(V) HS-FtTCP15-GLosgfp with vacuolar membrane marker gene Attpk. c Colocalization of pBWA(V) HS-FtTCP18-GLosgfp with vacuolar membrane marker gene Attpk. GFP: Green fluorescent protein signal; Marker: Vacuolar membrane maker Attpk protein signal; Chl: Chlorophyll autofluorescence signal; BF: Bright field; Merge: Overlap of pictures. Bars = 10 μm

Discussion

TCP gene family in Tartary buckwheat is highly conserved

The phylogenetic analysis and sequence alignment of Tartary buckwheat, Arabidopsis, and rice indicate that all 26 FtTCPs can be classified into Class I (PCF) and Class II (CIN and CYC/TB1) (Fig. 2). Genes with close positions in the rootless phylogenetic tree have similar domains, which indicates that their functions are similar. For instance, the FtTCP15 is closed to the AtTCP10, which is one of the members of miR319-regulated class II TCPs and regulates multiple physiological processes, including jasmonic acid (JA) biosynthesis [41]. The OsTCP19 gene belonging to PCF (Class I) has been reported to play a role in modulating abscisic acid pathways to enhance the tolerance to drought and heat during the seedling and maturity stages [19]. The FtTCP18 may have the same function.

Among the two subfamilies, the Class I subfamily has more genes without introns in structure. Moreover, the same group of FtTCP members displays relatively conserved motif compositions and a similar exon–intron organization (Fig. 3), indicating that the FtTCPs have close evolutionary relationships and similar functions to the TCP genes in plants. The similarity of gene structure provides further evidence for the credibility of subfamily classification. Introns can increase the length of genes and the frequency of gene recombination. In this study, 16 FtTCPs, including the FtTCP15 and FtTCP18, have no introns, accounting for 62%. Genes with few introns tend to respond to stress more rapidly [42], and the introns-less genes of FtTCPs may facilitate the response to environmental changes. Additionally, specific conserved motifs are also one of the factors that contribute to the potential function. For example, Motif 5 appears twice in FtTCP15 and may have a special significance for the function of FtTCP15.

Moreover, the expansion in the evolution of the TCP family in Tartary buckwheat is due to segmental duplications rather than tandem duplications (Fig. 4). This fact is consistent with previous research results in Arabidopsis, cotton [43], and grape [44]. The results show that segment duplication is the main driving force for the evolution and expansion of the TCP gene family, coinciding with the relatively high conservation of the TCP gene family. In addition, more orthologous gene pairs from the CIN group were identified among Tartary buckwheat, rice and Arabidopsis (Fig. 5), showing that TCP genes in these plant species originated from a common ancestor during evolution and the genes in the CIN group have the same function.

In conclusion, the lack of introns in gene structure and the conserved nature in evolution endow the functional similarity and stability of TCPs across species, which provides an important genetic basis for further studying the function of TCPs in the response of Tartary buckwheat to abiotic stresses.

Cis-elements indicate the FtTCP15 and FtTCP18 play a unique role in the response of Tartary buckwheat to abiotic stresses

TCP transcription factors usually mediate the transmission of hormone signals, regulate the activity of phytohormone [45], and inhibit the promoting effect of gibberellin [46] and the biosynthesis of auxin [47] in the plant. Recent studies in Arabidopsis have suggested that members of the TCP family can form response modules with other genes to jointly regulate methyl jasmonate homeostasis [41], and thus may affect plant responses to abiotic stresses. Therefore, the FtTCPs can directly or indirectly affect cellular functions of plants, thereby affecting the plants’ growth, development, and response to abiotic stresses.

In this paper, the proportion of cis-elements responding to stress is 17% in Tartary buckwheat (Table S3, S4). The relatively high number of two cis-element promoters (anaerobic induction and anoxic specific inducibility) would result in the high expression of TCP family members in the anaerobic environment, such as WL. Typically, WL is probably caused by artificial irrigation, drainage, and excessive non-human rainfall. An oxygen-deficient state will occur when plants are in a flooded state for a long time [48]. These results provide insights into the molecular mechanism of the response of FtTCP genes, especially FtTCP15 and FtTCP18, to WL (Fig. 7). Particularly, both FtTCP15 and FtTCP18 were significantly activated by WL and UV treatments (Fig. 2). Moreover, all light-responsive elements were found to be abundant in all FtTCPs. This result may be related to the biological clock regulation function of the TCP gene family previously reported [49]. In addition, we speculated that the light response elements are also related to the UV stress response. Ultraviolet radiation can affect plant growth and morphogenesis, especially in places with sufficient light, and high doses of UV-B, which can affect physiological and biochemical processes [31].

These results demonstrate that the TCP gene family may be involved in plant responses to abiotic stresses by regulating different biological processes such as direct response, hormonal regulation, and indirect response to abiotic stresses through morphogenesis. For example, the COM1 protein, which is homologous to the BDI1 TCP regulator in sorghum and Brachy podium, has been reported to adjust the shape of the spike inflorescence [50].

The FtTCPs act as important nodes in the interaction network in response to abiotic stresses

In recent years, several works have demonstrated that transcription factors could be promising targets for improving adaptability under environmental stress. In this work, 26 FtTCP genes were identified from the Tartary buckwheat genome. Under six abiotic stresses, the selected 12 genes in the root, stem, and leaf responded to different stress environments and had different expression patterns in different tissues and at different times. Among the 12 FtTCPs, five genes were activated by the specific stress, and the correlation coefficients of gene expression levels under abiotic stress were calculated (Fig. 7; Figure S1). The TCP family in soybean exhibited similar response trends under different abiotic stresses [51]. In this work, FtTCP2 and FtTCP8 showed the highest correlation of expression levels under abiotic stress and both of them were highly expressed in the stem (Fig. 8a). The FtTCP18 participated in multiple stress responses. Additionally, FtTCP15 was highly up-regulated under WL and UV environments, with the root, stem, and leaf expressed for 24 h.

Transcription factors, such as homo-dimers and hetero-dimers, often build combinations or interact with other proteins rather than acting alone to perform their complex biological functions [8]. Moreover, studies have shown that TCPs belonging to the CIN group can inhibit MYB gene-related transcripts and protein complexes at the transcription and protein levels [21], indicating that TCP members can form a regulatory network through interactions with other genes. The TCPs module, consisting of Class I and Class II TCP proteins, has been reported to manipulate important development processes, including hormone homeostasis in Arabidopsis [41]. In this study, FtTCPs have a high interaction frequency in the interaction network. For example, the nodes of FtTCP15 and FtTCP18 are 41 and 44, respectively. These results indicated that FtTCPs have an important regulatory function in the interaction network and play the regulatory role in different tissues of Tartary buckwheat.

The regulation role of FtTCPs as transcription factors

Subcellular localization shows that FtTCP18 is located in the nucleus (Fig. 9). Additionally, the determination of the subcellular localization of FtTCP15 was in the nucleus and cytoplasm. Some studies also indicated that the subcellular localization of transcription factors is not in the nucleus or incompletely in the nucleus [52, 53]. There are many possible reasons for this phenomenon. Firstly, the results of subcellular localization analysis with different receptor materials are probably inconsistent. For example, bHLH039 is mainly localized in the cytoplasm of tobacco leaf cells. In contrast, the nucleus and cytoplasm of Arabidopsis protoplasts have obvious signals [53]. Secondly, some treatments can change the location of transcription factors. As a transcription factor, BZR1 is located in the cytoplasm without any treatment. After Brassinosteroids (BRs) treatment, BZR1 is recruited into the nucleus because the original components in the cytoplasm have been transferred [52].

In conclusion, we proved that the FtTCP family plays a biological function as transcription factors in buckwheat by laboratory methods. For further study, various methods can be used to verify the transcriptional activity of FtTCPs. For example, a yeast experimental system can be used to analyze the transcriptional activation activity of NAC family members [54].

Further studies on the function and molecular mechanism of FtTCP15 and FtTCP18 response to abiotic stresses in Tartary buckwheat are imperative

As an important pseudo-cereal crop, Tartary buckwheat will also face severe challenges to growth in the natural environment. As the global climate worsens, abiotic stress factors such as WL, UV, salt, dark, heat, cold and/or their combinations pose a serious threat to the growth, yield, and quality of crops. Additionally, TCP transcription factors can transform various endogenous and environmental signals and provide the most comfortable conditions for plant growth [55]. It is credible to hypothesize the manipulation of candidate FtTCP members in Tartary buckwheat with multiple stress adaptability.

In this study, FtTCP15 and FtTCP18 can be regarded as promising candidates for improving the adaptability of abiotic stress in Tartary buckwheat for their molecular characteristics, response to multiple abiotic stresses, and high correlation with other proteins. It is imperative to further study their function by molecular biology techniques. For example, the role of transcription factors in response to abiotic stresses can be determined by studying the binding of transcription factors and promoters using the dual-luciferase gene detection test and by studying the interaction of transcription factors with other proteins through subcellular colocalization tests. Conclusions about the analysis of the clear transcription network, identification of target genes, clarification of the connection with hormones and/or metabolic synthesis, and transcription modification [56] can elucidate the systemic functions of FtTCPs transcription factors in response to stress in Tartary buckwheat.

Conclusions

Many studies have reported that the TCP gene family is vital to abiotic stress response in plants. In this work, 26 FtTCPs were identified in Tartary buckwheat and unevenly distributed on eight chromosomes. Further studies on evolutionary relationships, conservative motifs, gene structure, and cis-elements of the FtTCP gene family have been conducted. Under multiple abiotic stress treatments, the expression levels of the 12 selected FtTCPs were correlated, and the expression patterns of these genes tended to be spatio-temporal specific. The interaction network prediction of FtTCPs with many proteins indicated that FtTCPs are essential in the genetic manipulation response to abiotic stress. In addition, FtTCP15 and FtTCP18 are responsive to multiple abiotic stresses. The subcellular localization showed that both FtTCP15 and FtTCP18 localized in the nucleus, and the properties of FtTCPs as transcription factors are confirmed by laboratory methods. The results demonstrated the conserved nature in the evolution of the TCP gene family in Tartary buckwheat and suggested that the TCP gene family is functionally conserved in different species. The results also showed that the TCP gene family may be involved in plant responses to abiotic stresses by regulating different biological processes. Therefore, further studies on the functions of FtTCP15 and FtTCP18 by molecular biology techniques are feasible and imperative.

Methods

Bio-informatics data of TCP genes in Tartary buckwheat

In this study, two approaches were used to identify the TCP family in the Tartary buckwheat genome. The Hidden Markov Model (HMM) profile and the whole genome sequence information of Tartary Buckwheat were obtained from TBGP (Tartary Buckwheat Genome Project; http://www.mbkbase.org/Pinku1/). These sequences were then combined to compare the model with the TCP domain (PF03634) from the Pfam protein family database (http://pfam.xfam.org/) to ensure consistency. Two BLASTp methods were used to identify FtTCP members. First, all possible FtTCP proteins referring to TCP protein sequences were identified with BLASTp. Then, candidate FtTCP proteins containing the TCP domain were obtained by removing the redundant sequences using PFAM and SMART programs. Second, BLASTp in NCBI was used to verify whether all candidate FtTCPs were members of the TCP family. Finally, 26 FtTCPs were identified. As shown in Table S1, the coding sequence (CDS) length, isoelectric point (pI), and amino acid numbers were analyzed. Conserved domains for protein were analyzed using SMART (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/). The subcellular localization was predicted using the ExPasy website (http://web.expasy.org/protparam/).

Genome-wide characteristic analysis of the FtTCP gene family

The distribution of FtTCPs on eight Tartary buckwheat chromosomes was obtained using CIRCOS software (Version 0.69).

Then, the TCP protein sequence was obtained from the UniProt database (https://www.uniprot.org). The full-length amino acid sequences and TCP domain sequences, 26 from Tartary buckwheat (FtTCP), 24 from Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh.) (AtTCP), and 22 from rice (Oryza sativa L.) (OsTCP), were used to generate an unrooted phylogenetic tree. The Arabidopsis TCP protein sequence was downloaded from The Arabidopsis Information Resources (TAIR) database (http://www.arabidopsis.org). The TCP protein sequences for multiple amino acid sequence alignments in three plants were analyzed, and the phylogenetic tree was built using the neighbor-joining (NJ) method of MEGA 7.0 Software, Geneious R11 with a BLOSUM62 matrix, and the Jukes Cantor substitution model. We set the global alignment with free end gaps and a bootstrap value of 1000.

The exon/intron structures of FtTCPs were generated with TBtools software [57]. The differences in the conserved protein motifs in Tartary buckwheat TCP proteins were compared using the protein conserved motif online search program MEME (http:/meme.nbcr.net/meme/intro.html). The motif breadth was set as 6 to 200 amino acids (aa). A total of 15 motifs (named Motif 1 to Motif 15) were selected for analysis (Table S2).

Multiple collinear scanning toolkits (MCScanX) with an E-value of 1e-10 were used to study the gene duplication events in FtTCP genes. In addition, the relationship of the TCP family between Tartary buckwheat and other plants, including Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh.), tomato (Solanum lycopersicum (L.) Mill.), soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.), apple (Malus pumila L.), rice (Oryza sativa L.) and maize (Zea mays (L.) Sp.), was analyzed using Dual Systeny Plotter software (Version 1.0 +) (https://github.com/CJ-Chen/TBtools).

The sequence regions 2000 bp upstream of FtTCP family members were extracted from the Tartary buckwheat genome as putative promoters. Then, the cis-acting elements on TBtools software (Version 1.0 +) [57] were predicted according to these putative promoters (Table S3; Table S4).

Plant growth and treatments

The seeds of Tartary buckwheat were cultured in plastic pots in Guiyang, Guizhou Province, China. The cultivation environment was a 14/10 h photoperiod (daytime, 06:00–20:00) cycle with about 80% humidity at 22 °C. In order to analyze the expression profiles of FtTCP genes in roots, stems, and leaves in response to stress, 6-week-old seedlings were subjected to multiple abiotic stresses, including cold (low temperature, 4 °C), dark, heat (40 °C), salt (salinity, 200 mM NaCl) [34], UV radiation (70 µW/cm2, 220 V, 30 W), and WL (water inundating the surface of the earth with ddH2O). Under all treatments, samples were harvested with three biological replicates at 0, 2, and 24 h, then immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at -80 °C for RNA extraction. Seedlings without stress treatment were the control. Moreover, seedlings grown in natural conditions were collected for tissue-specific analysis of genes with three biological replicates.

RNA extraction, expression analysis by qRT-PCR, and interaction network prediction

In this work, to ensure that the response of genes contained in each subfamily to stress could be observed, 2 to 5 genes were randomly selected from each group (12 genes in total) for expression analysis. Total RNA was isolated from the sample using the RNAiso reagent Trizol (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Then the potential genomic DNA contamination was removed from RNA using RNase-free DNase I (TaKaRa). The first-strand cDNA was synthesized using the Prime Script RT enzyme mix (Takara). Moreover, the QTower3G instrument (Analytik Jena AG) was used for the qPCR experiment, with each 10 µL amplification reaction containing 5 µL of 2 × PCR MIX (Roche), 0.1 µL of each primer (up 50 pM/µL, down 50 pM/µL), 3.8 µL of H2O, and 1 µL of cDNA template. The PCR cycle program included initial denaturation (95 °C/10 min) and 40 cycles of 94 °C for 10 s, 60 °C for 20 s, and 60 °C for 20 s. The gene-specific primers (Table S7) were designed based on the nucleotide sequence of the TCP gene in Tartary buckwheat using Primer 5.0 software (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/). The Tartary buckwheat FtH3 gene was employed as an internal reference sequence with the same program [58]. Three technical repeats were performed for each biological replicate, and the relative expression levels of each gene under abiotic stress were calculated by the 2–∆∆Ct method [59] compared with the control gene. The relative expression levels for tissue-specific analysis of each gene were calculated by the 2–∆Ct method. Finally, variance analysis and histogram were conducted on all data, and Duncan's multiple range test (P < 0.05; n = 3) was performed using SPSS (Version 25.0) and the Origin software (Origin Lab Corporation, Northampton, Massachusetts, USA) (Version 8.0) statistics program. Data correlation was analyzed using the RStudio (https://www.rstudio.com/) “corrplot” package. The analysis of heatmaps visualizing expression was performed using TBtools software (Version 1.0 +) [57].

The interaction network between the TCP family with known proteins and predicted proteins was predicted using the String (https://string-db.org/) for online protein-protein interaction prediction. The prediction included direct physical interactions between proteins and indirect protein functional relevance interactions. After downloading, relevant data of the prediction (Table S3; Table S4) were visualized using Cytoscape (Version 3.8.2) (https://cytoscape.org/download.html).

Subcellular localization

According to the expression levels of genes under abiotic stress, FtTCP15 and FtTCP18 were found to be generally responsive to multiple abiotic stresses. Moreover, we are interested in further exploring the molecular mechanisms of FtTCP15 and FtTCP18.

First, wild-type Colombian Arabidopsis seedlings were cultured in greenhouses at 25 °C for protoplast preparation. The first step: After 25 days of incubation (no bolting), some leaves were soaked in the enzymolysis solution (Cellulase R10, 1.5%; Macerozyme R10, 0.75%; Mannitol, 0.6 M; MES (pH 5.7), 10 mM; H2O, constant volume of 10 mL), and then left to stand at 24 °C for 4 h. The second step: The treated samples were filtered through a 40 μm strainer and centrifuged at 300 rpm for 3 min to remove the supernatant. Then samples were washed twice with 10 mL of pre-cooled W5 solution (NaCl (58.5), 154 mM; CaCl2 (111), 125 mM; KH2PO4 (136), 2 mM; MES, 2 mM; Glucose (180), 5 mM; H2O, constant volume to 100 mL) and centrifuged at 300 rpm at 4 °C for 3 min. The third step: 500 μL of MMG suspended solution (Mannitol, 0.4 M; MgCl2∙6H2O (203), 15 mM; MES, 4 mM; H2O, constant volume of 100 mL) was added to 100 μL of protoplasts and then observed under a 40 times microscope. The number of protoplasts per field should reach 20–40 to meet the requirements. The Cellulase R10, Macerozyme R10, Mannitol, MES (pH 5.7), and PEG4000 were provided by BIOSHARP (Labgic Co., Ltd, China); CaCl2, NaCl, KH2PO4, and MgCl2∙6H2O were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd, China.

Second, the coding regions of FtTCP15 and FtTCP18 were amplified by PCR and fused to the pBWA(V)HS-ccdb-GLosgfp (Wuhan RiORUN Co., Ltd, China), which was modified by the pCAMBIA1302 expression vector. Using pBWA(V)HS-ccdb-GLosgfp as control, pBWA(V)HS-FtTCP15-GLosgfp and pBWA(V)HS-FtTCP18-GLosgfp were transferred into the Arabidopsis protoplasts prepared from leaves [60]. The 100 μL of protoplast suspension was mixed with a 20 μL plasmid of the target DNA plasmid. Simultaneously, PEG4000 solution (120 μL) equal to the total volume of DNA and protoplast was added, gently mixed, and left to stand at room temperature for 30 min. Finally, the reaction was terminated with 1 mL of W5 dilution. The reactants were centrifuged at 300 rpm for 3 min to collect protoplasts and remove the supernatant. After washing twice, 1 mL of W5 solution was added again and cultured at 28 °C for 24 h in the dark. After transformation, GFP fluorescence was observed under a laser scanning confocal microscope (Nikon C2-ER, Japan). All transient expression assays were repeated at least four times.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplementaryfile 1: Table S1. Detail informationdescription of the TCP gene family in Tartary buckwheat (Fagopyrumtataricum (L.) Gaertn.).

Additional file 2: Supplementaryfile 2: Table S2. The logo and name ofmotifs of FtTCPs in this study.

Additional file 3: Supplementaryfile 3: Table S3. The cis-elements of the FtTCPgenome sequence (detail information).

Additional file 4: Supplementaryfile 4: Table S4. The cis-elements of the FtTCPgenome sequence (data analysis).

Additional file 5: Supplementaryfile 5: Figure S1. The correlation analysisof the gene expression of 12 selected FtTCPs under different abioticstresses in this study.

Additional file 6: Supplementaryfile 6: Table S5. The interaction networkdata of FtTCPs from STRING in this study.

Additional file 7: Supplementaryfile 7: Table S6. The interaction network ofFtTCPs in this study.

Additional file 8: Supplementaryfile 8: Table S7. The primers used forqRT-PCR of FtTCPs in this study.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ABA

Abscisic Acid

- ABRE

Abscisic Acid Response Element

- ARE

Anaerobic

- CDS

Coding Sequence

- CIN

Cincinnata

- CYC

Cycloidea

- GFP

Green Fluorescent Protein

- ID

Identity

- JA

Jasmonic Acid

- LTR

Low-Temperature Responsiveness

- MBS

Myeloblastosis Binding Site

- MCScanX

Multiple Collinear Scanning Toolkits

- MEGA

Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis

- Me-JA

Methyl- Jasmonate

- MEME

Multiple Expectation Maximizations for Motif Elicitation

- MES

MES hydrate (C6H13NO4S)

- MMG

Monomycolylglycerol solution

- Mw

Molecular weight

- NAC

No apical meristem & Ataf1/2 & cup-shaped cotyledon

- PCF

Proliferating Cell Factors

- PEG

Polyethylene Glycol

- pI

Isoelectric point

- PL

Length of protein

- qRT-PCR

Quantificational Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

- SMART

Simple Modular Architecture Research Tool

- TB1

Teosinte Branched 1

- TBGP

Tartary Buckwheat Genome Project

- TCP

Teosinte branched 1 & Cycloidea & Proliferating Cell Factors

- TF

Transcription Factor

- UV

Ultraviolet

- UV-B

Ultraviolet-Biological

- W

Predicted subcellular location

- WUN

Wound-Responsive

- WL

Water Logging

Authors’ contributions

MY planned and designed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. GH revised the manuscript. QH, YF, LD, and KL identified and analyzed the genome-wide of the gene family. XW, ZQ, and EC studied the gene expression by qRT-PCR. TH supervised the research. All authors reviewed the manuscript. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Program Foundation of Institute for Scientific Research of Karst Area of NSFC-GZGOV (No. U1612442), Guizhou Science and Technology Agency Fund for Basic-condition Platform (No. [2019]5701), and Construction Program of Biology First-class Discipline in Guizhou (No. GNYL [2017]009).

Availability of data and materials

The whole Fagopyrum tataricum genome sequence information was obtained from the website (http://buckwheat.kazusa.or.jp/index.html), which is open to all researchers. The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included in the article and additional files. We have not used KEGG Pathway Database.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Tartary buckwheat materials (“Ku Qiao 7 hao”) used in this study were supplied by the Laboratory of Wheat Crop Research Center, Agriculture College, Guizhou University, in compliance with the appropriate permissions and/or licenses for the collection of seed specimens. Experimental research and field studies on plants (either cultivated or wild), including the collection of plant material, comply with relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines and legislation.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Riechmann JL, Heard J, Martin G, Reuber L, Jiang C, Keddie J, Adam L, Pineda O, Ratcliffe OJ, Samaha RR, et al. Arabidopsis transcription factors: genome-wide comparative analysis among eukaryotes. Science. 2000;290(5499):2105–2110. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5499.2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jin J, Tian F, Yang D-C, Meng Y-Q, Kong L, Luo J, Gao G. PlantTFDB 4.0: toward a central hub for transcription factors and regulatory interactions in plants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016:gkw982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Chen J, Nolan TM, Ye H, Zhang M, Tong H, Xin P, Chu J, Chu C, Li Z, Yin Y. Arabidopsis WRKY46, WRKY54, and WRKY70 Transcription Factors Are Involved in Brassinosteroid-Regulated Plant Growth and Drought Responses. Plant Cell. 2017;29(6):1425–1439. doi: 10.1105/tpc.17.00364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heyman J, Canher B, Bisht A, Christiaens F, De Veylder L. Emerging role of the plant ERF transcription factors in coordinating wound defense responses and repair. J Cell Sci. 2018;131(2):jcs208215. doi: 10.1242/jcs.208215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zheng K, Ni Z, Qu Y, Cai Y, Yang Z, Sun G, Chen Q. Genome-wide identification and expression analyses of TCP transcription factor genes in Gossypium barbadense. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):14526. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-32626-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seven M, Akdemir H. DOF, MYB and TCP transcription factors: Their possible roles on barley germination and seedling establishment. Gene Expr Patterns. 2020;37:119116. doi: 10.1016/j.gep.2020.119116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.He G, Tian W, Qin L, Meng L, Wu D, Huang Y, Li D, Zhao D, He T. Identification of novel heavy metal detoxification proteins in Solanum tuberosum: Insights to improve food security protection from metal ion stress. Sci Total Environ. 2021;779:146197. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.146197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khan S-A, Li M-Z, Wang S-M, Yin H-J. Revisiting the role of plant transcription factors in the battle against abiotic stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(6):1634. doi: 10.3390/ijms19061634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aasamaa K, Sõber A. Stomatal sensitivities to changes in leaf water potential, air humidity, CO2 concentration and light intensity, and the effect of abscisic acid on the sensitivities in six temperate deciduous tree species. Environ Exp Bot. 2011;71(1):72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2010.10.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vishwakarma K, Upadhyay N, Kumar N, Yadav G, Singh J, Mishra RK, Kumar V, Verma R, Upadhyay RG, Pandey M, et al. Abscisic Acid Signaling and Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Plants: A Review on Current Knowledge and Future Prospects. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:161. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Devireddy AR, Zandalinas SI, Fichman Y, Mittler R. Integration of reactive oxygen species and hormone signaling during abiotic stress. Plant J. 2021;105(2):459–476. doi: 10.1111/tpj.15010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manna M, Thakur T, Chirom O, Mandlik R, Deshmukh R, Salvi P. Transcription factors as key molecular target to strengthen the drought stress tolerance in plants. Physiol Plant. 2021;172(2):847–868. doi: 10.1111/ppl.13268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cubas P, Lauter N, Doebley J, Coen E. The TCP domain: a motif found in proteins regulating plant growth and development. Plant J. 1999;18(2):215–222. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kosugi S, Ohashi Y. PCF1 and PCF2 specifically bind to cis elements in the rice proliferating cell nuclear antigen gene. Plant Cell. 1997;9(9):1607–1619. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.9.1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kosugi S, Ohashi Y. DNA binding and dimerization specificity and potential targets for the TCP protein family. Plant J. 2002;30(3):337–348. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2002.01294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shang Y, Yuan L, Di Z, Jia Y, Zhang Z, Li S, Xing L, Qi Z, Wang X, Zhu J, et al. A CYC/TB1-type TCP transcription factor controls spikelet meristem identity in barley. J Exp Bot. 2020;71(22):7118–7131. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eraa416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu Z, Yang J, Li S, Liu L, Qanmber G, Chen G, Duan Z, Zhao N, Wang G. Systematic Characterization of TCP Gene Family in Four Cotton Species Revealed That GhTCP62 Regulates Branching in Arabidopsis. Biol (Basel). 2021;10(11):1104. doi: 10.3390/biology10111104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu MM, Wang MM, Yang J, Wen J, Guo PC, Wu YW, Ke YZ, Li PF, Li JN, Du H. Evolutionary and Comparative Expression Analyses of TCP Transcription Factor Gene Family in Land Plants. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(14):3591. doi: 10.3390/ijms20143591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mukhopadhyay P, Tyagi AK. OsTCP19 influences developmental and abiotic stress signaling by modulating ABI4-mediated pathways. Sci Rep. 2015;5:9998. doi: 10.1038/srep09998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou M, Li D, Li Z, Hu Q, Yang C, Zhu L, Luo H. Constitutive expression of a miR319 gene alters plant development and enhances salt and drought tolerance in transgenic creeping bentgrass. Plant Physiol. 2013;161(3):1375–1391. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.208702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lan J, Zhang J, Yuan R, Yu H, An F, Sun L, Chen H, Zhou Y, Qian W, He H, et al. TCP transcription factors suppress cotyledon trichomes by impeding a cell differentiation-regulating complex. Plant Physiol. 2021;186(1):434–451. doi: 10.1093/plphys/kiab053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boukid F, Folloni S, Sforza S, Vittadini E, Prandi B. Current Trends in Ancient Grains-Based Foodstuffs: Insights into Nutritional Aspects and Technological Applications. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2018;17(1):123–136. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joshi DC, Zhang K, Wang C, Chandora R, Khurshid M, Li J, He M, Georgiev MI, Zhou M. Strategic enhancement of genetic gain for nutraceutical development in buckwheat: A genomics-driven perspective. Biotechnol Adv. 2020;39:107479. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2019.107479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huda MN, Lu S, Jahan T, Ding M, Jha R, Zhang K, Zhang W, Georgiev MI, Park SU, Zhou M. Treasure from garden: Bioactive compounds of buckwheat. Food Chem. 2021;335:127653. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.127653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park BI, Kim J, Lee K, Lim T, Hwang KT. Flavonoids in common and tartary buckwheat hull extracts and antioxidant activity of the extracts against lipids in mayonnaise. J Food Sci Technol. 2019;56(5):2712–2720. doi: 10.1007/s13197-019-03761-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sinkovic L, KokaljSinkovic D, Meglic V. Milling fractions composition of common (Fagopyrum esculentum Moench) and Tartary (Fagopyrum tataricum (L.) Gaertn.) buckwheat. Food Chem. 2021;365:130459. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu H, Lv M, Peng Q, Shan F, Wang M. Physicochemical and textural properties of tartary buckwheat starch after heat-moisture treatment at different moisture levels. Starch - Stärke. 2015;67(3–4):276–284. doi: 10.1002/star.201400143. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ge RH, Wang H. Nutrient components and bioactive compounds in tartary buckwheat bran and flour as affected by thermal processing. Int J Food Prop. 2020;23(1):127–137. doi: 10.1080/10942912.2020.1713151. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wargent JJ, Moore JP, Roland Ennos A, Paul ND. Ultraviolet radiation as a limiting factor in leaf expansion and development. Photochem Photobiol. 2009;85(1):279–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2008.00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gruber H, Heijde M, Heller W, Albert A, Seidlitz HK, Ulm R. Negative feedback regulation of UV-B-induced photomorphogenesis and stress acclimation in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(46):20132–20137. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914532107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trost Sedej T, ErznoZnik T, Rovtar J. Effect of UV radiation and altitude characteristics on the functional traits and leaf optical properties in Saxifraga hostii at the alpine and montane sites in the Slovenian Alps. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2020;19(2):180–192. doi: 10.1039/c9pp00032a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hideg E, Jansen MAK, Strid A. UV-B exposure, ROS and stress: inseparable companions or loosely linked associates? Trends Plant Sci. 2013;18:107–115. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang L, Li X, Ma B, Gao Q, Du H, Han Y, Li Y, Cao Y, Qi M, Zhu Y, et al. The Tartary Buckwheat Genome Provides Insights into Rutin Biosynthesis and Abiotic Stress Tolerance. Mol Plant. 2017;10(9):1224–1237. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2017.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li H, Xu G, Yang C, Yang L, Liang Z. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of HKT transcription factor under salt stress in nine plant species. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2019;171:435–442. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yao X, Ma H, Wang J, Zhang D. Genome-Wide Comparative Analysis and Expression Pattern of TCP Gene Families in Arabidopsis thaliana and Oryza sativa. J Integrative Plant Biol. 2007;49(6):885–897. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2007.00509.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang S, Zhou Q, Chen F, Wu L, Liu B, Li F, Zhang J, Bao M, Liu G. Genome-Wide Identification, Characterization and Expression Analysis of TCP Transcription Factors in Petunia. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(18):6594. doi: 10.3390/ijms21186594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parapunova V, Busscher M, Busscher-Lange J, Lammers M, Karlova R, Bovy AG, Angenent GC, de Maagd RA. Identification, cloning and characterization of the tomato TCP transcription factor family. BMC Plant Biol. 2014;14:157. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-14-157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dietz KJ. Redox regulation of transcription factors in plant stress acclimation and development. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;21(9):1356–1372. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Negi P, Rai AN, Suprasanna P. Moving through the Stressed Genome: Emerging Regulatory Roles for Transposons in Plant Stress Response. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1448. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.He G-H, Xu J-Y, Wang Y-X, Liu J-M, Li P-S, Chen M, Ma Y-Z, Xu Z-S. Drought-responsive WRKY transcription factor genes TaWRKY1 and TaWRKY33 from wheat confer drought and/or heat resistance in Arabidopsis. BMC Plant Biol. 2016;16(1):1–16. doi: 10.1186/s12870-015-0700-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rath M. Role of TCP transcription factors in seedling development, leaf morphogenesis and senescence in Arabidopsis thaliana. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fan Y, Yan J, Lai D, Yang H, Xue G, He A, Guo T, Chen L, Cheng XB, Xiang DB, et al. Genome-wide identification, expression analysis, and functional study of the GRAS transcription factor family and its response to abiotic stress in sorghum [Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench] BMC Genomics. 2021;22(1):509. doi: 10.1186/s12864-021-07848-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ma J, Liu F, Wang Q, Wang K, Jones DC, Zhang B. Comprehensive analysis of TCP transcription factors and their expression during cotton (Gossypium arboreum) fiber early development. Sci Rep. 2016;6:21535. doi: 10.1038/srep21535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leng X, Wei H, Xu X, Ghuge SA, Jia D, Liu G, Wang Y, Yuan Y. Genome-wide identification and transcript analysis of TCP transcription factors in grapevine. BMC Genomics. 2019;20(1):786. doi: 10.1186/s12864-019-6159-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nicolas M, Cubas P. TCP factors: new kids on the signaling block. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2016;33:33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2016.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Resentini F, Felipo-Benavent A, Colombo L, Blazquez MA, Alabadi D, Masiero S. TCP14 and TCP15 mediate the promotion of seed germination by gibberellins in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol Plant. 2015;8(3):482–485. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2014.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lucero LE, Uberti-Manassero NG, Arce AL, Colombatti F, Alemano SG, Gonzalez DH. TCP15 modulates cytokinin and auxin responses during gynoecium development in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2015;84(2):267–282. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goyal K, Kaur K, Kaur G. Foliar treatment of potassium nitrate modulates the fermentative and sucrose metabolizing pathways in contrasting maize genotypes under water logging stress. Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2020;26(5):899–906. doi: 10.1007/s12298-020-00779-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aguilar-Martinez JA, Sinha N. Analysis of the role of Arabidopsis class I TCP genes AtTCP7, AtTCP8, AtTCP22, and AtTCP23 in leaf development. Front Plant Sci. 2013;4:406. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Poursarebani N, Trautewig C, Melzer M, Nussbaumer T, Lundqvist U, Rutten T, Schmutzer T, Brandt R, Himmelbach A, Altschmied L, et al. COMPOSITUM 1 contributes to the architectural simplification of barley inflorescence via meristem identity signals. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):5138. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18890-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Feng ZJ, Xu SC, Liu N, Zhang GW, Hu QZ, Gong YM. Soybean TCP transcription factors: Evolution, classification, protein interaction and stress and hormone responsiveness. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2018;127:129–142. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2018.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang R, Wang R, Liu M, Yuan W, Zhao Z, Liu X, Peng Y, Yang X, Sun Y, Tang W. Nucleocytoplasmic trafficking and turnover mechanisms of BRASSINAZOLE RESISTANT1 in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(33):e2101838118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2101838118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Trofimov K, Ivanov R, Eutebach M, Acaroglu B, Mohr I, Bauer P, Brumbarova T. Mobility and localization of the iron deficiency-induced transcription factor bHLH039 change in the presence of FIT. Plant Direct. 2019;3(12):e00190. 10.1002/pld3.190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Hao Y-J, Song Q-X, Chen H-W, Zou H-F, Wei W, Kang X-S, Ma B, Zhang W-K, Zhang J-S, Chen S-Y. Plant NAC-type transcription factor proteins contain a NARD domain for repression of transcriptional activation. Planta. 2010;232(5):1033–1043. doi: 10.1007/s00425-010-1238-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Danisman S. TCP Transcription Factors at the Interface between Environmental Challenges and the Plant's Growth Responses. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1930. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xia C, Gong Y, Chong K, Xu Y. Phosphatase OsPP2C27 directly dephosphorylates OsMAPK3 and OsbHLH002 to negatively regulate cold tolerance in rice. Plant Cell Environ. 2021;44(2):491–505. doi: 10.1111/pce.13938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen C, Chen H, Zhang Y, Thomas HR, Frank MH, He Y, Xia R. TBtools: An Integrative Toolkit Developed for Interactive Analyses of Big Biological Data. Mol Plant. 2020;13(8):1194–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2020.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li C, Zhao H, Li M, Yao P, Li Q, Zhao X, Wang A, Chen H, Tang Z, Bu T. Validation of reference genes for gene expression studies in tartary buckwheat (Fagopyrum tataricum Gaertn.) using quantitative real-time PCR. PeerJ. 2019;7:e6522. doi: 10.7717/peerj.6522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nat Protoc. 2008;3(6):1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yoo SD, Cho YH, Sheen J. Arabidopsis mesophyll protoplasts: a versatile cell system for transient gene expression analysis. Nat Protoc. 2007;2(7):1565–1572. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Supplementaryfile 1: Table S1. Detail informationdescription of the TCP gene family in Tartary buckwheat (Fagopyrumtataricum (L.) Gaertn.).

Additional file 2: Supplementaryfile 2: Table S2. The logo and name ofmotifs of FtTCPs in this study.

Additional file 3: Supplementaryfile 3: Table S3. The cis-elements of the FtTCPgenome sequence (detail information).

Additional file 4: Supplementaryfile 4: Table S4. The cis-elements of the FtTCPgenome sequence (data analysis).

Additional file 5: Supplementaryfile 5: Figure S1. The correlation analysisof the gene expression of 12 selected FtTCPs under different abioticstresses in this study.

Additional file 6: Supplementaryfile 6: Table S5. The interaction networkdata of FtTCPs from STRING in this study.

Additional file 7: Supplementaryfile 7: Table S6. The interaction network ofFtTCPs in this study.

Additional file 8: Supplementaryfile 8: Table S7. The primers used forqRT-PCR of FtTCPs in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The whole Fagopyrum tataricum genome sequence information was obtained from the website (http://buckwheat.kazusa.or.jp/index.html), which is open to all researchers. The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included in the article and additional files. We have not used KEGG Pathway Database.