Abstract

Vaccines have been used to fight and protect against infectious diseases for centuries. With the emergence of immunotherapy in cancer treatment, researchers began investigating vaccines that could be used against cancer, especially against tumors that are resistant to conservative chemotherapy, surgery, and radiotherapy. The Wilms' tumor 1 (WT1) protein is immunogenic, has been detected in almost all types of malignancies, and has played a significant role in prognosis and disease monitoring. In this article, we review recent developments in the treatment of various types of cancers with the WT1 cancer vaccine; we also discuss theoretic considerations of various therapeutic approaches, which were based on preclinical and clinical data.

Keywords: peptide-based vaccine, immunotherapy, WT1 gene, leukemia, solid cancer, toxicity, preclinical trails, clinical trials, cancer medicine, cancer vaccine

INTRODUCTION

Immunotherapy, or stimulating the body's immune system to fight disease, has been used in the fight against cancer since the late 18th century.[1] Immunotherapy has an active form consisting of therapeutic cancer vaccines, immunostimulatory cytokines, and checkpoint inhibitors, and a passive form that includes tumor-targeting monoclonal antibodies, immunomodulatory monoclonal antibodies, oncolytic viruses, and adoptively transferred T cells.[2–6] Tumor response to immunotherapy can take more time than tumor response to chemotherapy, and for most patients who receive immunotherapy, the tumor progresses before it regresses; therefore, treatment outcome in immunotherapy cannot be evaluated by the same criteria used to evaluate response to chemotherapy.[7]

In 2009, the National Cancer Institute, selected for study 75 cancer antigens on the basis of (1) therapeutic function, (2) immunogenicity, (3) specificity, (4) oncogenicity, (5) cells' positive rates for antigens, (6) stem cell expression, (7) number of patients who were positive for the antigen, (8) number of epitopes, and (9) cellular location of expression.[8] According to these well-vetted criteria, generated by expert panels, Wilms' tumor 1 (WT1) ranked as the most promising among the 75 cancer antigens.[8]

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN WT1 PROTEIN AND NEOPLASMS

The WT1 gene, located on human chromosome 11 (band p13), is important in transcriptional regulation, which consists of a proline and glutamine-rich region and 4 zinc finger domains.[9] Homogenous deletion of both alleles is required for the development of Wilms' tumor, a childhood kidney tumor, in which WT1 was identified as a tumor suppressor gene.[10]

Oji et al[11] found that WT1 plays an important role as both a tumor suppressor gene and oncogene. Cells from the 32D clone cell line that were infected with wild-type WT1 proliferated without differentiation, whereas normal control cells and mutant WT1-infected 32D clone cells differentiated into mature cells after granulocyte colony-stimulating factor stimulation.[12] Miwa et al[13] concluded that the WT1 gene plays a crucial role in the early stage of hematologic differentiation.

Higher levels of both WT1 mRNA and protein have been seen in prostate carcinoma than in benign prostate tumors.[14] Miyagi et al[15] also reported that WT1 gene expression could be detected in several types of immature lymphoid or myeloid leukemia cells without gene mutation. WT1 protein is detected immunohistochemically in biopsy specimens of most types of cancer.[16] Although very little or no WT1 gene expression was noted with immunostaining for the WT1 gene, more WT1 gene expression was observed with reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction, and Oji et al[17] determined that this discrepancy was primarily due to tests with various levels of sensitivity.[18]

The WT1 gene is important not only for prognosis but also for diagnosis in hematologic malignancies. Increased levels of WT1 gene expression had a significant role in predicting disease relapse in leukemic patients with complete remission.[19] As in Wilms' tumor, mutation of the WT1 gene was reported in acute myeloid leukemia (AML), but it was required primarily for disease progression rather than for disease initiation.[20] Simultaneous production of IgG and IgM antibodies was found not only in patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, but also in patients with hematologic malignancies, such as AML, chronic lymphoblastic leukemia, and myelodysplastic syndrome, owing to repeated and continuous activation of WT1 antigens from leukemic cells.[21]

Study of the WT1 gene significantly improved our understanding of solid tumor malignancies. The WT1 gene is expressed not only in all colorectal carcinomas but also in most normal-appearing colorectal mucosal tissues, and expression of this gene has been reported to be greatly varied.[22] This kind of variation in gene expression was also noted in almost all types of thyroid cancers, in thyroid adenoma, and in normal-appearing thyroid tissue, but was present in only 30% to 70% of tumor cells in adenomas that were weakly stained immunohistochemically for WT1 protein.[23] Expression without mutation was observed in bone and soft-tissue sarcoma.[24] Malignant mesothelioma can be differentiated from other types of cancers, such as adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma, by WT1 immunostaining.[25]

TYPES OF WT1 VACCINE

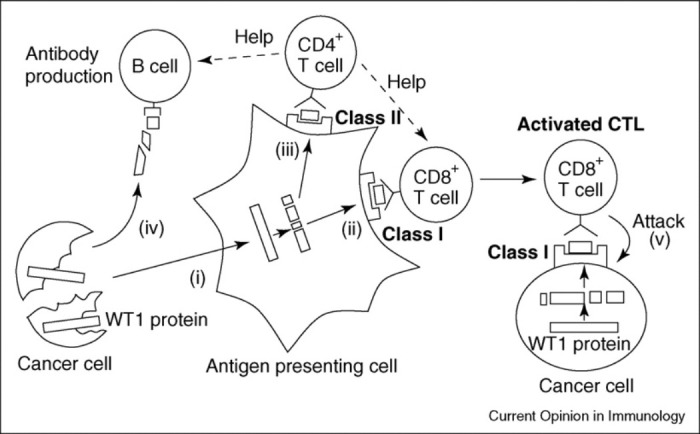

The WT1 gene acts as an oncogene that initiates the proliferation of malignant cells.[26] Loss or mutation of the gene, which can lead to loss of immune vigilance, is not common with WT1 antigen[27] and immune response against WT1 is illustrated in Figure 1.[28] Clinical trials for the WT1 vaccine are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Elicitation of immune responses against Wilms' tumor 1 (WT1) protein in cancer patients. Cancer cell-derived WT1 protein is ingested by antigen-presenting cells (APCs), such as dendritic cells (DCs) (i), and is processed in them, followed by presentation of WT1 peptides in association with human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I or II molecules on the surface of the APCs (ii and iii), while the WT1 protein stimulates B lymphocytes to produce anti-WT1 antibody (iv). WT1 peptide/HLA class I complexes stimulate CD8+ T cells to make WT1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) (ii). WT1 peptide/HLA class II complexes stimulate CD4+ T cells to make WT1-specific helper T cells (iii), which more activate (“help”) cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) and B cells, respectively. Activated B cells produce anti-WT1 antibody of class-switched IgG-type as well as IgM-type. Activated WT1-specific CTLs attack cancer cells that have WT1 peptide/HLA class I complexes on the cell surfaces (v). Reprinted from Current Opinion in Immunology, Vol 20, Oka Y, Tsuboi A, Oji Y, et al, WT1 peptide vaccine for the treatment of cancer, 211-220, Copyright 2008, with permission from Elsevier.

Table 1.

Clinical trials for WT1 peptide-based vaccine in solid and hematological malignancies

|

NCT Number

|

Reference

|

Types of Neoplasm

|

Intervention

|

Sample Size

|

End Point

|

Outcomes

|

Adverse Effects

|

| NR | 53 | AML | WT1 vaccine in combination with zoledronate | 3 | WT1 immune response was noted in patients with transient decline in leukemic cells and stable disease | SD – 1 PD – 1 | No serious adverse effect |

| 00398138 | 54 | AML | WT1 peptide vaccine | 9 | Median overall survival – 35+ mo Mean time for follow-up from diagnosis – 30 mo | CCR – 5 RD – 4 | No serious adverse effect except in 1 patient who developed generalized urticaria and laryngeal spasm as a delayed grade 2 reaction to vaccine |

| NR | 55 | AML | WT1 peptide vaccine | 10 | Immune responses that are closely related to clinical response | Molecular remission – 5 | No serious adverse effect except in 1 patient with pain in axillary LN along drainage and another patient who exhibited transient decline in platelet count and mild flare-up of preexisting Achilles and foot tendonitis |

| 00313638 | 56 | Myeloid malignancies (AML, MDS, CML) | WT1 and PR1 peptide vaccines | 8 | Median follow-up of 252 d (105–523 d) | SD – 2 CR – 3 RD – 2 Mol R – 1 | No serious adverse effect except in 1 patient who developed chest pain that resolved without intervention, probably owing to GM-CSF |

| 00665002 | 57 | Myeloid neoplasm | WT1 peptide vaccine | 13 (MDS – 2, AML – 11) | Patients tolerated the vaccine | Transfusion dependence was noted to be temporally less in a patient with MDS, and relapse-free survival was reported to be longer than 1 year in 2 AML patients | No serious adverse effect |

| 00923910 | 58 | AML, ALL, HL | WT1 peptide vaccine with DLI | 5 (ALL – 3, AML – 1, Hodgkin – 1) | WT 1 vaccine is safe and tolerable after allogenic HCT | PD – 5 | No serious adverse effect except in 1 patient with grade 1 skin GVHD resolved without systemic treatment |

| NR | 59 | Head and neck cancer | WT1 peptide-pulsed dendritic cell vaccination combined with conventional chemotherapy | 11 | PFS – 6.4 mo OS – 12.1 mo | SD – 5 patients PD – 6 patients | No serious adverse effect |

| NR | 60 | Advanced biliary tract cancer | WT1 and/or MUC1 peptide-pulsed dendritic cell vaccination | 65 | MST from diagnosis – 18.5 mo, MST from the first vaccination – 7.2 mo (WT1 alone – 5.1 mo, MUC1 alone – 6.6 mo, WT1+MUC1 – 8.2 mo) | PR – 4 SD – 15 PD – 44 UE – 2 | No serious adverse effect |

| NR | 61 | Advanced pancreatic or biliary tract cancer | Combination therapy of WT1 vaccine and GEM | 18 | MST – 278 d (biliary tract cancer – 288 d, gallbladder cancer – 153 d, intrahepatic bile duct cancer – 384 d, extrahepatic bile duct cancer – 301 d, pancreatic cancer – 259 d) | DCR pancreatic cancer – 89% gallbladder cancer – 25% intrahepatic bile duct cancer – 100% extrahepatic bile duct cancer – 50% | Cytopenia owing to GEM was reported in all patients, grade 3–4 neutropenia in 11 patients and grade 3 anemia in 3 patients |

| NR | 62 | Advanced lung cancer | WT1 peptide vaccine | 2 | Detection of a higher level of WT1-specific CTLs precursors in the pleural fluid than in PBMC | Decline in tumor markers, such as CEA and SLX, was seen after serial WT1 vaccinations in lung cancer patients | No serious adverse effect |

| NR | 63 | Breast or lung cancer, MDS, or AML | WT1 peptide vaccine | 26 | WT1 immune response was noted in 8/11 patients with clinical response (1 patient could not evaluate the immune response because of inadequate PBMC due to pancytopenia) | Clinical response – 12 SD – 2 UE – 6 PD – 6 | No serious adverse effect |

| NR | 64 | Breast cancer, glioblastoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, primary neuroectodermal tumor, and rectal cancer | WT1 peptide vaccine | 10 | Toxicity for the weekly vaccination was acceptable and antitumor effect was noted | PR – 1 SD – 5 PD – 4 | No serious adverse effect |

| NR | 65 | Gynecologic malignancies (ovarian cancer, cervical cancer, uterine carcinoma and, corpus cancer) | WT1 peptide vaccine | 12 | DIC – 25% | SD – 3 PD – 9 | No serious adverse effect |

| 00398138 | 66 | Mesothelioma and non– small cell lung cancer | WT1 peptide vaccine | 11 | MST from initial vaccination – 14 mo | PD – 8 SD – 1 Relapse – 2 | No serious adverse effect |

| NR | 67 | Pancreatic cancer | WT1 peptide vaccine combined with multimodal therapy | 6 | Median OS – 1796.5 d Median PFS – 607 d | SD – 3 PD – 3 | No adverse effect is mentioned |

| NR | 68 | Pediatric cancer | WT1 peptide vaccine | 5 | WT1 vaccine has potential therapeutic outcomes | Clinical response – 1 SD – 1 PD – 3 | No serious adverse effect |

ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; APCs, antigen presenting cells; CCR, continuous complete remission; CD, cluster of differentiation; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; CLL, chronic lymphoblastic leukemia; CR, complete remission; GEM, gemcitabine; GVHD, graft versus host disease; HCT, hematopoietic cell transplantation; HL, Hodgkin lymphoma; LCLs, lymphoblastoid cell lines; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; Mol R, molecular response; MST, median survival time; MUC1, mucin 1 cell surface associated; NCT, national clinical trial; NR, no register; OS, overall survival; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; RD, relapse disease; SD, stable disease; SLX: Sialyl Lewis (x); UE, unevaluable; WT, Wilms' tumor 1

The WT1 vaccine can be categorized into the following 4 groups, depending on the use of the WT1 antigens: (1) human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-restricted peptide vaccines, (2) non–HLA-restricted long peptides vaccines, (3) dendritic cell (DC) vaccines loaded with HLA-restricted peptide, and (4) DC vaccines loaded with mRNA encoding full-length WT1.[28] Among the various types of WT1 vaccines, HLA-restricted WT1 peptides had been used in most of the trials and were extensively investigated.[29] Although HLA-restricted WT1 peptides have the advantage of being simple and effective, Van Driessche et al[29] concluded that they were restricted to individual patients' HLA haplotype and could activate only cytotoxic CD8+ T cells.

When the heteroclite WT1-A1 peptide's sequence was inserted into the longer WT1-122A1–long peptide, which can activate both CD4+ and CD8+ cells, the peptide vaccine was enhanced to be better recognized by T-cell receptors and to have increased immunogenicity over the various HLA subtypes.[30] When WT1 peptide and keyhole limpet–hemocyanin-pulsed donor-derived DC vaccine were given to a patient with relapsed AML after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, no graft-versus-host disease or other serious adverse events were noticed, and only local erythema with grade 2 itching at the injection site was reported.[31]

Although a strong immune response was detected, no clinical response was observed, and Kitawaki et al[31] concluded that sufficient potency of WT1-specific responses for the growing leukemic cells might be needed. Kitawaki et al[31] also recommended treating patients with detectable WT1-specific memory CD8+ T cells before immunization and only those patients with less invasive tumors, such as patients with minimal residual disease or those whose disease is in remission.

In DC-based vaccine, vaccine antigen needs to be in contact with DCs to generate an immune response.[32] The extent of antigen needed for the DCs was unknown.[33] Zityogel et al[34] found that these antigens could be used in immunotherapy for cancer in clinical trials. For example, expression of WT1 mRNA can be detected in bone marrow and peripheral blood in patients with AML.[35–40] Protein vaccination can activate humoral immune responses but is rarely used for immunization in clinical trials due to the lack of CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell induction.[29] Full-length WT1 mRNA can be used to transfect DCs to activate not only humoral immunity but also cellular immunity to eradicate cancer cells.[29] Owing to the advantages of a better clinical safety profile and reproducibility, mRNA was used to transfect DCs for WT1 vaccination.[41–44]

After assessing the differences in immunogenicity between WT1 HLA class I peptide (WT1235) and WT1 HLA class II peptide (WT1332), Tsuboi et al[45] observed more promising immune responses in most of the patients by a surge of (WT1235)-specific interferon (IFN)-γ–producing CD8+ T cells and (WT1332)-specific tumor necrosis factor-α–producing CD4+ T cells after vaccination with the cocktail vaccine of WT1 HLA class I and II peptides. CD4+helper T cells are important for both priming and effector phases for cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) via direct helper signals, such as cytokine or cell contact–mediated stimulation.[46] Results suggested that CD4+ HTLs potentiated the immunotherapeutic effect of CTLs by promoting the functional activity of CTLs via an increase in IFN-γ–producing cell frequencies, and that this effect was stronger than that produced by increasing the tetramer of cell frequencies.[46] Because immature antigen-presenting cells cannot prime CTLs, CD4+ HTLs are needed for differentiation of these immature cells.[47–49]

PRECLINICAL TRIALS

When mice were immunized with a WT1 peptide vaccine, we observed not only WT1-specific CTLs but also rejection across tumor cells, which expressed WT1 without autoimmunity, although podocytes of the kidney glomeruli and bone marrow CD34+ cells expressed WT1.[50] Inhibition of cell growth was seen only in the WT1-expressing leukemic cell line when both the leukemic cell line, which expressed WT1, and a normal cell line, which did not express WT1, were tested with WT1 antisense oligomers; Yamagami et al[51] concluded that WT1 is an essential oncogene in leukemogenesis.

The cytotoxic ability of CTLs was seen in lung cancer cells, which expressed the WT1 gene, but the antitumor effect of CTLs was inhibited by anti-HLA class I mAb.[52] Decreased cytolytic activity of WT-specific lung cancer CTLs was noted with the WT1-WT2–loaded autologous lymphoblastoid cell line, and the absence of cytotoxicity was observed when WT1-WT2–loaded HLA-A24–negative lymphoblastoid cell lines were tested with CTLs.[52] The growth of lung cancer cells in nude mice decreased when mice were treated with WT1-specific CTLs.[52]

CONCLUSIONS

Immunotherapy, reported to be the best option for eradicating residual malignant cells, has been found to be effective and to have with minimal toxicity in cancer patients. Having a better understanding of the WT1 protein can enhance the scope of cancer medicine, not only for diagnostic purposes but also for treatment protocols for malignancy, especially for patients with advanced or aggressive cancers. Because the outcomes of patients who underwent adjuvant treatments were more promising than were those of patients who did not undergo these treatments, the WT1 vaccine can be one of the reliable standard multimodal therapies in the near future. Although excellent overall survival and PFS rates were reported with WT1 vaccination, clinical trials with better protocol guidelines and larger sample sizes are still needed for data on the safety of the WT1 vaccine.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Tamara K. Locke from Scientific Publications, Research Medical Library at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center for her critical review of the manuscript.

Funding Statement

Source of Support: None.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None.

References

- 1.Anguille S, Smits EL, Bryant C, et al. Dendritic cells as pharmacological tools for cancer immunotherapy. Pharmacologic Rev . 2015;67:731–753. doi: 10.1124/pr.114.009456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anguille S, Smits EL, Lion E, van Tendeloo VF, Berneman ZN. Clinical use of dendritic cells for cancer therapy. Lancet Oncol . 2014;15:e257–e267. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70585-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mackall CL, Merchant MS, Fry TJ. Immune-based therapies for childhood cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol . 2014;11:693. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2014.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Melief CJM, van Hall T, Arens R, Ossendorp F, van der Burg SH. Therapeutic cancer vaccines. J Clin Invest . 2015;125:3401–3412. doi: 10.1172/JCI80009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ceppi F, Beck-Popovic M, Bourquin JP, Renella R. Opportunities and challenges in the immunological therapy of pediatric malignancy: a concise snapshot. Eur J Pediatr . 2017;176:1163–1172. doi: 10.1007/s00431-017-2982-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galluzzi L, Vacchelli E, Bravo-San Pedro JM, et al. Classification of current anticancer immunotherapies. Oncotarget . 2014;5:12472. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Childs R, Chernoff A, Contentin N, et al. Regression of metastatic renal-cell carcinoma after nonmyeloablative allogeneic peripheral-blood stem-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med . 2000;343:750–758. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200009143431101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheever MA, Allison JP, Ferris AS, et al. The prioritization of cancer antigens: a national cancer institute pilot project for the acceleration of translational research. Clin Cancer Res . 2009;15:5323–5337. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Call KM, Glaser T, Ito CY, et al. Isolation and characterization of a zinc finger polypeptide gene at the human chromosome 11 Wilms' tumor locus. Cell . 1990;60:509–520. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90601-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huff V, Miwa H, Haber DA, et al. Evidence for WT1 as a Wilms tumor (WT) gene: intragenic germinal deletion in bilateral WT. Am J Human Genet . 1991;48:997. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oji Y, Ogawa H, Tamaki H, et al. Expression of the Wilms' tumor gene WT1 in solid tumors and its involvement in tumor cell growth. Jpn J Cancer Res . 1999;90:194–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1999.tb00733.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inoue K, Tamaki H, Ogawa H, et al. Wilms' tumor gene (WT1) competes with differentiation-inducing signal in hematopoietic progenitor cells. Blood . 1998;91:2969–2976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miwa H, Beran M, Saunders GF. Expression of the Wilms' tumor gene (WT1) in human leukemias. Leukemia . 1992;6:405–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Devilard E, Bladou F, Ramuz O, et al. FGFR1 and WT1 are markers of human prostate cancer progression. BMC Cancer . 2006;6:272. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miyagi T, Ahuja H, Kubota T, Kubonishi I, Koeffler HP, Miyoshi I. Expression of the candidate Wilm's tumor gene, WT1 in human leukemia cells. Leukemia . 1993;7:970–977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakatsuka S, Oji Y, Horiuchi T, et al. Immunohistochemical detection of WT1 protein in a variety of cancer cells. Modern Pathol . 2006;19:804–814. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oji Y, Ogawa H, Tamaki H, et al. Expression of the Wilms' tumor gene WT1 in solid tumors and its involvement in tumor cell growth. Jpn J Cancer Res . 1999;90:194–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1999.tb00733.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silberstein GB, Van Horn K, Strickland P, Roberts CT, Daniel CW. Altered expression of the WT1 Wilms tumor suppressor gene in human breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A . 1997;94:8132–8137. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.15.8132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garg M, Moore H, Tobal K, Yin JAL. Prognostic significance of quantitative analysis of WT1 gene transcripts by competitive reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction in acute leukaemia. Br J Haematol . 2003;123:49–59. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miyagawa K, Hayashi Y, Fukuda T, Mitani K, Hirai H, Kamiya K. Mutations of the WT1 gene in childhood nonlymphoid hematological malignancies. Genes Chromosomes Cancer . 1999;25:176–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elisseeva OA, Oka Y, Tsuboi A, et al. Humoral immune responses against Wilms tumor gene WT1 product in patients with hematopoietic malignancies. Blood . 2002;99:3272–3279. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.9.3272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oji Y, Yamamoto H, Nomura M, et al. Overexpression of the Wilms' tumor gene WT1 in colorectal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Sci . 2003;94:712–717. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2003.tb01507.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oji Y, Miyoshi Y, Koga S, et al. Overexpression of the Wilms' tumor gene WT1 in primary thyroid cancer. Cancer Sci . 2003;94:606–611. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2003.tb01490.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ueda T, Oji Y, Naka N, et al. Overexpression of the Wilms' tumor gene WT1 in human bone and soft-tissue sarcomas. Cancer Sci . 2003;94 doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2003.tb01432.x. 271v276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amin KM, Litzky LA, Smythe WR, et al. Wilms' tumor 1 susceptibility (WT1) gene products are selectively expressed in malignant mesothelioma. Am J Pathol . 1995;146:344. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sugiyama H. Wilms' tumor gene WT1 its oncogenic function and clinical application. Int J Hematol . 2001;73:177–187. doi: 10.1007/BF02981935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Busse A, Letsch A, Scheibenbogen C, et al. Mutation or loss of Wilms' tumor gene 1 (WT1) are not major reasons for immune escape in patients with AML receiving WT1 peptide vaccination. J Transl Med . 2010;8:5. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-8-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oka Y, Tsuboi A, Oji Y, Kawase I, Sugiyama H. WT1 peptide vaccine for the treatment of cancer. Curr Opin Immunol . 2008;20:211–220. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Driessche A, Berneman ZN, Van Tendeloo VFI. Active specific immunotherapy targeting the Wilms' tumor protein 1 (WT1) for patients with hematological malignancies and solid tumors: lessons from early clinical trials. Oncologist . 2012;17:250. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maslak PG, Dao T, Krug LM, et al. Vaccination with synthetic analog peptides derived from WT1 oncoprotein induces T-cell responses in patients with complete remission from acute myeloid leukemia. Blood . 2010;116:171–179. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-250993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kitawaki T, Kadowaki N, Kondo T, et al. Potential of dendritic cell immunotherapy for relapse after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, shown by WT1 peptide and keyhole limpet hemocyanin-pulsed, donor-derived dendritic cell vaccine for acute myeloid leukemia. Am J Hematol . 2008;83:315–317. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steinman RM, Hawiger D, Nussenzweig MC. Tolerogenic dendritic cells. Ann Rev Immunol . 2003;21:685–711. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Banchereau J, Palucka AK. Dendritic cells as therapeutic vaccines against cancer. Nat Rev Immunol . 2005;5:296–306. doi: 10.1038/nri1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zitvogel L, Mayordomo JI, Tjandrawan T, et al. Therapy of murine tumors with tumor peptide-pulsed dendritic cells: dependence on T cells, B7 costimulation, and T helper cell 1-associated cytokines. J Exp Med . 1996;183:87–97. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.1.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cilloni D, Renneville A, Hermitte F, et al. Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction detection of minimal residual disease by standardized WT1 assay to enhance risk stratification in acute myeloid leukemia: a European LeukemiaNet study. J Clin Oncol . 2009;27:5195–5201. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.4865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Inoue K, Ogawa H, Yamagami T, et al. Long-term follow-up of minimal residual disease in leukemia patients by monitoring WT1 (Wilms tumor gene) expression levels. Blood . 1996;88:2267–2278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cilloni D, Gottardi E, De Micheli D, et al. Quantitative assessment of WT1 expression by real time quantitative PCR may be a useful tool for monitoring minimal residual disease in acute leukemia patients. Leukemia . 2002;16:2115–2121. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trka J, Kalinova M, Hrušák O, et al. Real-time quantitative PCR detection of WT1 gene expression in children with AML: prognostic significance, correlation with disease status and residual disease detection by flow cytometry. Leukemia . 2002;16:1381–1389. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garg M, Moore H, Tobal K, Yin JAL. Prognostic significance of quantitative analysis of WT1 gene transcripts by competitive reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction in acute leukaemia. Br J Haematol . 2003;123:49–59. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lapillonne H, Renneville A, Auvrignon A, et al. High WT1 expression after induction therapy predicts high risk of relapse and death in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol . 2006;24:1507–1515. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.5303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van Driessche A, Gao L, Stauss H, et al. Antigen-specific cellular immunotherapy of leukemia. Leukemia . 2005;19:1863–1871. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Driessche A, Van de Velde ALR, Nijs G, et al. Clinical-grade manufacturing of autologous mature mRNA-electroporated dendritic cells and safety testing in acute myeloid leukemia patients in a phase I dose-escalation clinical trial. Cytotherapy . 2009;11:653–668. doi: 10.1080/14653240902960411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van VFT, Ponsaerts P, Berneman ZN. mRNA-based gene transfer as a tool for gene and cell therapy. Curr Opin Mol Ther . 2007;9:423–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van Tendeloo VFI, Ponsaerts P, Lardon F, et al. Highly efficient gene delivery by mRNA electroporation in human hematopoietic cells: superiority to lipofection and passive pulsing of mRNA and to electroporation of plasmid cDNA for tumor antigen loading of dendritic cells. Blood . 2001;98:49–56. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tsuboi A, Hashimoto N, Fujiki F, et al. A phase I clinical study of a cocktail vaccine of Wilms' tumor 1 (WT1) HLA class I and II peptides for recurrent malignant glioma. Cancer Immunol Immunother . 2019;68:331–340. doi: 10.1007/s00262-018-2274-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fujiki F, Oka Y, Tsuboi A, et al. Identification and characterization of a WT1 (Wilms tumor gene) protein-derived HLA-DRB1* 0405-restricted 16-mer helper peptide that promotes the induction and activation of WT1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Immunother . 2007;30:282–293. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000211337.91513.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schoenberger SP, Toes REM, van der Voort EIH, Offringa R, Melief CJM. T-cell help for cytotoxic T lymphocytes is mediated by CD40–CD40L interactions. Nature . 1998;393:480. doi: 10.1038/31002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bennett SRM, Carbone FR, Karamalis F, Flavell RA, Miller JFAP, Heath WR. Help for cytotoxic-T-cell responses is mediated by CD40 signalling. Nature . 1998;393:478–480. doi: 10.1038/30996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ridge JP, Di Rosa F, Matzinger P. A conditioned dendritic cell can be a temporal bridge between a CD4+ T-helper and a T-killer cell. Nature . 1998;393:474–478. doi: 10.1038/30989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tsuboi A, Oka Y, Ogawa H, et al. Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses elicited to Wilms' tumor gene WT1 product by DNA vaccination. J Clin Immunol . 2000;20:195–202. doi: 10.1023/a:1006637529995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yamagami T, Sugiyama H, Inoue K, et al. Growth inhibition of human leukemic cells by WT1 (Wilms tumor gene) antisense oligodeoxynucleotides: implications for the involvement of WT1 in leukemogenesis. Blood . 1996;87:2878–2884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Makita M, Hiraki A, Azuma T, et al. Antilung cancer effect of WT1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Clin Cancer Res . 2002;8:2626–2631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kitawaki T, Kadowaki N, Fukunaga K, et al. A phase I/IIa clinical trial of immunotherapy for elderly patients with acute myeloid leukaemia using dendritic cells co-pulsed with WT1 peptide and zoledronate. Br J Haematol . 2011;153:796–799. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Maslak PG, Dao T, Krug LM, et al. Vaccination with synthetic analog peptides derived from WT1 oncoprotein induces T-cell responses in patients with complete remission from acute myeloid leukemia. Blood . 2010;116:171–179. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-250993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Van Tendeloo VF, Van de Velde A, Van Driessche A, et al. Induction of complete and molecular remissions in acute myeloid leukemia by Wilms' tumor 1 antigen-targeted dendritic cell vaccination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A . 2010;107:13824–13829. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008051107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rezvani K, Yong ASM, Mielke S, et al. Leukemia-associated antigen-specific T-cell responses following combined PR1 and WT1 peptide vaccination in patients with myeloid malignancies. Blood . 2008;111:236–242. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-108241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brayer JB, Lancet JE, Powers JJ, et al. Pilot trial of a WT-1 analog peptide vaccine in patients with high-risk myeloid neoplasms. J Clin Oncol . 2014;32:3089–3089. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shah NN, Loeb DM, Khuu H, et al. Induction of immune response after allogeneic Wilms' tumor 1 dendritic cell vaccination and donor lymphocyte infusion in patients with hematologic malignancies and post-transplantation relapse. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant . 2016;22:2149–2154. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2016.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ogasawara M, Miyashita M, Yamagishi Y, Ota S. Phase I/II pilot study of Wilms' tumor 1 peptide-pulsed dendritic cell vaccination combined with conventional chemotherapy in patients with head and neck cancer. Ther Apher Dial . 2019;23:279–288. doi: 10.1111/1744-9987.12831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kobayashi M, Sakabe T, Abe H, et al. Dendritic cell-based immunotherapy targeting synthesized peptides for advanced biliary tract cancer. J Gastrointest Surg . 2013;17:1609–1617. doi: 10.1007/s11605-013-2286-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kaida M, Morita-Hoshi Y, Soeda A, et al. Phase 1 trial of Wilms tumor 1 (WT1) peptide vaccine and gemcitabine combination therapy in patients with advanced pancreatic or biliary tract cancer. J Immunother . 2011;34:92–99. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181fb65b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tsuboi A, Oka Y, Osaki T, et al. WT1 peptide-based immunotherapy for patients with lung cancer: report of two cases. Microbiol Immunol . 2004;48:175–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2004.tb03503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Oka Y, Tsuboi A, Taguchi T, et al. Induction of WT1 (Wilms' tumor gene)-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes by WT1 peptide vaccine and the resultant cancer regression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A . 2004;101:13885–13890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405884101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Morita S, Oka Y, Tsuboi A, et al. A phase I/II trial of a WT1 (Wilms' tumor gene) peptide vaccine in patients with solid malignancy: safety assessment based on the phase I data. Jpn J Clin Oncol . 2006;36:231–236. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyl005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ohno S, Kyo S, Myojo S, et al. Wilms' tumor 1 (WT1) peptide immunotherapy for gynecological malignancy. Anticancer Res . 2009;29:4779–4784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Krug LM, Dao T, Brown AB, et al. WT1 peptide vaccinations induce CD4 and CD8 T cell immune responses in patients with mesothelioma and non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother . 2010;59:1467–1479. doi: 10.1007/s00262-010-0871-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hanada S, Tsuruta T, Haraguchi K, Okamoto M, Sugiyama H, Koido S. Long-term survival of pancreatic cancer patients treated with multimodal therapy combined with WT1-targeted dendritic cell vaccines. Human Vaccin Immunother . 2019;15:397–406. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2018.1524238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hashii Y, Sato E, Ohta H, Oka Y, Sugiyama H, Ozono K. WT1 peptide immunotherapy for cancer in children and young adults. Pediatr Blood Cancer . 2010;55:352–355. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]