Abstract

In lactococci, transamination is the first step of the enzymatic conversion of aromatic and branched-chain amino acids to aroma compounds. In previous work we purified and biochemically characterized the major aromatic aminotransferase (AraT) of a Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris strain. Here we characterized the corresponding gene and evaluated the role of AraT in the biosynthesis of amino acids and in the conversion of amino acids to aroma compounds. Amino acid sequence homologies with other aminotransferases showed that the enzyme belongs to a new subclass of the aminotransferase I subfamily γ; AraT is the best-characterized representative of this new aromatic-amino-acid-specific subclass. We demonstrated that AraT plays a major role in the conversion of aromatic amino acids to aroma compounds, since gene inactivation almost completely prevented the degradation of these amino acids. It is also highly involved in methionine and leucine conversion. AraT also has a major physiological role in the biosynthesis of phenylalanine and tyrosine, since gene inactivation weakly slowed down growth on medium without phenylalanine and highly affected growth on every medium without tyrosine. However, another biosynthesis aromatic aminotransferase is induced in the absence of phenylalanine in the culture medium.

The enzymatic degradation of amino acids in cheese plays a major role in cheese flavor development. Indeed, degradation products from aromatic, branched-chain, and sulfurous amino acids have been identified in various cheeses and highly contribute to their flavor (7, 12, 23, 26, 27) or to their off-flavor (10, 11, 18, 35). However, the pathways of amino acid degradation in cheese microflora, and especially in lactococci, which are widely used as starter cultures, are still poorly understood. We previously found that in lactococci, the first step in degradation of aromatic and branched-chain amino acids is transamination (40), and this was confirmed by Gao et al. (13). In a previous work, we purified and biochemically characterized an aromatic aminotransferase (AraT) from Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris NCDO763 (43) that initiates the degradation of leucine, tyrosine, phenylalanine, tryptophan, and methionine, all precursors of cheese flavor compounds. Recently, a homologous enzyme was purified from a Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis strain (14). In the course of the purification, it was estimated that AraT was responsible for more than 93% of the phenylalanine aminotransferase activity in the cell extract (CE) (43). Also, it has been shown that phenylpyruvate formed from phenylalanine by transamination was further degraded to the flavor compounds phenyllactate and phenylacetate by lactococcal cells in vitro (43). Recently, this degradation of phenylpyruvate to phenyllactate, phenylacetate, and also to benzaldehyde in cheese was confirmed (44). Thus, AraT seems to have a major role in the conversion of aromatic amino acids to aroma metabolites by lactococcal cells and is also involved in the degradation of leucine and methionine. However, the real importance of this enzyme in amino acid degradation could only be demonstrated by experiments with an araT mutant. In previous work on AraT (43), we failed to conclude anything about its precise physiological role. It was suggested only that the enzyme is probably involved in both catabolism and biosynthesis of aromatic amino acids, since generally in bacteria, transamination of corresponding α-ketoacids is the last step in biosynthesis of phenylalanine and tyrosine. However, in several gram-negative bacteria, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, this major biosynthesis pathway can be replaced by another biosynthesis pathway via the conversion of prephenate in arogenate by a prephenate aminotransferase. Arogenate is then transformed to either phenylalanine or tyrosine by a cyclohexadienyl dehydratase or a cyclohexadienyl dehydrogenase, respectively, which are broad-specificity enzymes that also catalyze the transformation of prephenate to the α-ketoacids (phenylpyruvate and hydroxyphenylpyruvate) in the major biosynthesis pathway (20, 21, 30, 31, 42). A third pathway for tyrosine biosynthesis via hydroxylation of phenylalanine exists in P. aeruginosa, but this pathway is rare in prokaryotes (38, 45). Finally, tryptophan is synthesized in L. lactis by an alternative way, with the last step catalyzed by a tryptophan synthase (3).

The aim of this work was to evaluate the role and importance of AraT in both amino acid biosynthesis and conversion of amino acids to aroma compounds. For this purpose, we characterized the gene encoding lactococcal AraT and constructed an araT mutant. By investigating the impact of gene inactivation on amino acid degradation and on growth in different media, we demonstrated that AraT is almost completely responsible for the degradation of aromatic amino acids and is also highly involved in their biosynthesis. However, another biosynthetic aromatic aminotransferase that is induced by the absence of phenylalanine in culture media exists in L. lactis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. L. lactis strains were grown either in M17 medium (39) supplemented with 0.5% lactose or glucose or in a chemically defined medium (CDM) (37) at 30°C. Escherichia coli was grown in Luria-Bertani medium (34) at 37°C with aeration. When needed, erythromycin (5 μg · ml−1 for L. lactis and 150 μg · ml−1 for E. coli) or ampicillin (50 μg · ml−1 for E. coli) was added to the culture medium.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Characteristic(s) | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| L. lactis subsp. cremoris | ||

| NCDO763 | Wild type | National Collection of Food Bacteria (Shinfield, Reading, England) |

| TIL46 | NCDO763 cured of its 2-kb plasmid | |

| TIL313 | TIL46 araT mutant | This work |

| L. lactis subsp. lactis | ||

| NCDO2118 | Prototroph for branched-chain amino acids | 6 |

| JIM5762 | NCDO2118 with luxAB downstream of the araT promoter | This work |

| JIM5929 | NCDO2118 araT mutant with luxAB downstream of the araT promoter | This work |

| E. coli TG1 | 16 | |

| Plasmids | ||

| pTag | Cloning vector (T overhangs); lacZ f1 ori Apr Kanr ColE1 ori; 3.8 kb | Ingenius, Novagen, Inc. (Madison, Wis.) |

| pTIL200 | 1-kb fragment of araT in pTag | This work |

| pTIL212 | pTIL200 Emr | This work |

| pIL253 | Emr; 4.6 kb | 36 |

| pJIM2374 | Emr; integrative transcriptional fusion vector with the luxAB genes | 9 |

| pVE6007 | Cmr; allows the replication of pJIM2374 when present in trans | 25 |

DNA techniques.

All DNA manipulations were performed as described by Sambrook et al. (34). DNA restriction and modification enzymes were purchased from GIBCO-BRL (Cergy Pontoise, France) and Eurogentec (Seraing, Belgium) and used as recommended by the suppliers. The oligonucleotides were synthesized by Eurogentec.

Electrocompetent L. lactis cells were prepared by the Holo and Nes method (19), with minor modifications, and electrocompetent E. coli cells were prepared and transformed as described by Sambrook et al. (34).

Plasmid DNA was prepared with a plasmid purification kit from Qiagen Inc. (Chatsworth, Calif.) for E. coli and by the method of O’Sullivan and Klaenhammer for L. lactis (29). Chromosomal DNA from L. lactis was prepared as previously described (24, 34). RNA from L. lactis was prepared by the method described by Glatron and Rapoport (17).

Southern and Northern hybridizations were performed as described by Sambrook et al. (34) and as described by the supplier of the ECL kit (Amersham), respectively. A 1-kb PCR fragment obtained with oligonucleotides 1 and 2 (see below) was used as a probe; it was prepared with Ready to Go DNA Labeling Beads (without dCTP) from Pharmacia Biotech and [α-32P]dCTP (Amersham, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom) for Southern hybridization and with the ECL kit (Amersham) for Northern hybridization.

PCR, cloning, and sequencing.

PCR amplifications were done on a Perkin-Elmer model 480 or 2400 DNA thermal cycler by using the following cycling parameters. DNA denaturation was performed at 95°C for 1 min, followed by annealing at 50°C for 1 min and amplification at 72°C for 2 min, using Taq DNA polymerase (Appligene, Illkirch, France). This cycle was performed 30 times before a final amplification at 72°C for 10 min.

An araT fragment was amplified by PCR with two degenerated oligonucleotides (oligonucleotide 1, 5′-CAR-TTY-GAY-CAR-CAR-GT; oligonucleotide 2, 5′-TCN-CCR-TAY-TGN-CCR-AA, with Y being C, T; R being A, G; and N being A, G, C, T) deduced from the N-terminal sequence and an internal protein sequence of the purified enzyme (43). The 1-kb fragment obtained was cloned into plasmid pTag to yield pTIL200. The rest of the gene and its flanking regions were amplified by inverse PCR with a religated EcoRV digest of chromosomal DNA of L. lactis as a template and two primers chosen from the previously sequenced 1-kb fragment (oligonucleotide 3, 5′-GCG-TAA-TTA-AAG-GCT-CAT; oligonucleotide 4, 5′-GCA-CAG-ATT-ATT-AAG-ACG).

Sequencing was done at least twice for both strands, either on pTIL200 or on amplified fragments extracted from 0.7% agarose with Spin-X (Costar, Cambridge, United Kingdom). Samples for sequencing were prepared with the Tag Dye Primer cycle sequencing kit or the PRISM Ready Reaction Dye Deoxy terminator cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, United Kingdom). The sequences were determined on an automatic DNA sequencer (model 370A; Applied Biosystems).

The DNA and protein sequences were analyzed with the GCG program (Genetics Computer Group Inc., Madison, Wis.). Protein homology searches were carried out with the BLAST network service (2).

Gene inactivation.

The araT mutant was constructed from L. lactis subsp. cremoris TIL46. The erythromycin resistance gene of pIL253 (1.2-kb Sau3A fragment) was cloned into the unique BamHI site of pTIL200 to yield pTIL212. Plasmid pTIL212, which does not replicate in L. lactis, was integrated into the chromosome by single crossover, yielding the mutant TIL313 with araT interrupted.

The regulation of the araT promoter was studied with L. lactis subsp. lactis NCDO2118, which is more convenient than L. lactis NCDO763 for regulation studies, since it has fewer amino acid requirements and can grow in minimal media (8). Two mutants were constructed in which the luxAB genes were placed under the control of the araT promoter, one having araT interrupted while in the other araT was still expressed (Fig. 1). For this purpose, the 359-bp EcoRI-HindII and 739-bp HindII-HindIII fragments of araT, containing the potential promoter region and a part of the coding sequence of araT, respectively, were inserted into the integrative transcriptional fusion vector pJIM2374. The fusion vectors were integrated in the chromosome, yielding, respectively, JIM5762 (Fig. 1B) with araT intact and JIM5929 (Fig. 1C) with araT interrupted, both with the luxAB genes under the control of the araT promoter.

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the constructions of mutants with the luxAB genes as reporters under the control of the araT promoter. (A) Chromosome region containing araT in the wild-type strain; (B) construction with araT intact; (C) construction with araT interrupted.  , the region upstream of araT with two potential promoters and a potential terminator just upstream.

, the region upstream of araT with two potential promoters and a potential terminator just upstream.

Final constructions were verified by PCR or sequencing of the modified region or by Southern hybridization.

Luciferase assay.

Luciferase assays were performed with the fusion vector containing the promoter region of araT and mutants JIM5762 and JIM5929. Luciferase activity was monitored during growth by mixing 1 ml of culture with 5 μl of nonaldehyde and measuring the light emission in a Bertold luminometer (33). Values given in this work are those read on a curve (lux versus optical density [OD]) at an OD of 0.5.

Determination of aminotransferase activity.

Cells grown to late log phase were harvested by centrifugation (10,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C) and washed twice with 50 mM sodium β-glycerophosphate buffer (pH 7.0). They were resuspended in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) containing 2 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM EDTA, and 0.1 mM pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (Sigma Chemicals, St. Louis, Mo.) and were disrupted with glass beads in a mini-beadbeater cell disrupter three times for 1 min each time, with 1 min of cooling on ice after each time. After centrifugation (14,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C), the supernatants were filtered through 0.45-μm-pore-size filters (Millipore Co., Bedford, Mass.) and were considered CEs. The protein concentrations of the CEs were determined by the Bradford method (4) with the Coomassie protein assay reagent as specified by Pierce Chemical Company (Rockford, Ill.), with bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Amino acid aminotransferase activity in CEs was determined as previously described (43). The reverse reaction was determined by the same method, but the reaction was stopped by protein precipitation with phosphoric acid at a final concentration of 0.1%. l-Glutamate was measured after dilution with the sample buffer (pH 2.2; Biotronik, Eppendorf, Maintal, Germany) by amino acid analysis with an LC3000 automatic analyzer (Biotronik), and α-ketoglutarate was measured by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with an ion exclusion column (IC-PAK; Waters) thermostated at 60°C, with 0.1% phosphoric acid as the eluent at a flow rate of 0.8 ml min−1. Data are means of activity determinations in extracts of cells from three individual cultures.

Catabolism of amino acids.

The catabolism of amino acids by whole cells of L. lactis subsp. cremoris TIL46 was compared with that by whole cells of its araT mutant, using radiolabeled amino acids as a tracer (Isotopchim, Peyruis, France). The following radiolabeled amino acids were used: l-[2,6-3H]phenylalanine (60 Ci mmol−1), l-[3,5-3H]tyrosine (60 Ci mmol−1), l-[5-3H]tryptophan (20 Ci mmol−1), l-[4,5-3H]leucine (60 Ci mmol−1), l-[4,5-3H]isoleucine (89.6 Ci mmol−1), l-[3,4-3H]valine (40 Ci mmol−1), and l-[1-14C]methionine (55 mCi mmol−1). The reaction mixture contained 100 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8), a 2 mM concentration of an unlabeled amino acid, a 0.05 μM concentration of the same, labeled, amino acid, and 10 mM α-ketoglutarate. A quantity of cells from a CDM culture corresponding to an OD at 480 nm (OD480) of 10 were added to 500 μl of reaction mixture and incubated at 37°C. Aliquots of the reaction mixtures were analyzed after 0, 10, 20, and 40 h by reverse-phase HPLC with both UV (214 nm) and radioactivity detection as previously described (43, 44). Data are means of results obtained with cells from at least two individual cultures.

Growth curves.

The growth rates of the L. lactis NCDO763 strains in different minimal media were measured with a Bioscreen C analyzer (Labsystems, Helsinki, Finland) and a Biolink software program. A total of 300 μl of medium was inoculated with 6 μl of cells from an overnight saturated culture in CDM and washed twice with β-glycerophosphate, and the ODs were measured every 10 min at 450 nm during a 30-h period. Results are means of at least four determinations.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence reported in this paper appears in the DDBJ, EMBL, and GenBank nucleotide sequence databases under the accession no. AF146529.

RESULTS

Characterization of araT.

The analysis of the sequence revealed an open reading frame of 392 codons that could encode a 43-kDa protein. This size is in agreement with the molecular mass of the purified enzyme, which was previously estimated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis at 43.5 kDa (43). The amino acid sequences of the four protein fragments of the enzyme that had been sequenced earlier (42a) were present in the deduced amino acid sequence. We found a putative ribosome binding site (GAGG) ending 7 bp upstream of the ATG start codon and two potential promoters (TTGTCA-TATAAT and TTGTCA-TAGAAC) ending 12 and 40 bp upstream of the ribosome binding site. We also observed a putative ρ-independent transcriptional terminator ending 24 bp downstream of the stop codon. The araT potential promoters are preceded by a sequence that can form a ρ-independent terminator structure, suggesting that a specific promoter initiates the transcription of araT. Northern hybridization demonstrated that araT was expressed in a 1.3-kb transcript (results not shown), which means that araT is transcribed as a single gene. A comparison with the nucleotide sequence of the araT gene of L. lactis NCDO2118 showed that it is 91% homologous. As the latter strain is less auxotrophic for amino acids, it was used for expression studies. Also, the cloned potential promoter region in the fusion vector allowed the expression of the luciferase. These results confirm the presence of a promoter just upstream of the coding sequence of araT. Two gene fusions with the luxAB genes as reporter genes were introduced downstream of the promoter in a L. lactis NCDO2118 wild-type background and an araT mutant background. The activities of the two fusions were measured in CDM with or without phenylalanine, tyrosine, tryptophan, methionine, branched-chain amino acids, and α-ketoglutarate. The levels of transcription of these fusions were similar in all media (180 to 220 klx/OD unit), except in the absence of methionine, where it decreased twofold (80 to 110 klx/OD unit). The difference in expression between JIM5762 (with wild-type araT) and JIM 5929 (with mutant araT) was not significant (less than 20%).

Homologies.

The deduced amino acid sequence of araT had 21 to 36% homology with those of several aromatic, aspartate, and imidazole/acetol phosphate aminotransferases that belong to the subfamilies α, β, and γ of aminotransferase family I (22). For these subfamilies, Jensen and Gu (22) have revealed patterns of residue conservation (fingerprints), so in an attempt to classify AraT, we studied homologies of AraT with these fingerprints (Fig. 2). We also compared the substrate specificity of AraT with that of the enzymes of each subfamily. The amino acid sequence of AraT contained 80% of the conserved residues of subfamily γ, while it contained only 42% of the conserved residues of subfamily β and 24% of the conserved residues of subfamily α. Moreover, the AraT sequence did not contain the highly conserved subfamily α hinge region, whose role in the mechanism of action was thoroughly established. Also, the substrate specificity of AraT corresponds best to the enzymes of subfamily γ, since AraT is active on aromatic amino acids, leucine, and methionine, but not on aspartate. Indeed, aminotransferases classified in subfamily γ have narrow specificity, i.e., for either aspartate or the aromatic amino acids, while the aminotransferases of subfamily α have broad specificity, i.e., for both aspartate and the aromatic amino acids, and those of subfamily β have specificity for both imidazole acetol phosphate and aromatic amino acids. With these findings, we classified AraT in aminotransferase I subfamily γ.

FIG. 2.

Alignment of the fingerprints of subfamilies α, β, and γ of aminotransferase family I (according to Jensen and Gu [22]) with the amino acid sequence of AraT. The fingerprint residues conserved in AraT are bold and underlined. Asterisks indicate conserved residues of the subfamily α hinge region.

Distribution of araT in LAB.

An internal 1-kb fragment of araT was used as a probe for Southern hybridization with EcoRV digestions of DNA from 10 strains of lactic acid bacteria (LAB): L. lactis subsp. cremoris MG1363, AM2, and E8; L. lactis subsp. lactis IL1403 and IL2118; Streptococcus thermophilus CNRZ302; Lactobacillus bulgaricus ATCC 11842; Lactobacillus paracasei CNRZ262; Lactobacillus helveticus CNRZ223; and Lactobacillus plantarum CNRZ1008. Under high-stringency conditions (50% formamide), the probe hybridized only with all lactococcal DNA, but hybridization with L. lactis subsp. cremoris AM2 was weak. Under low-stringency conditions (20% formamide), it hybridized also with the DNA of S. thermophilus, but not with DNA of the Lactobacillus strains tested (data not shown).

Role of AraT in the degradation of amino acids to aroma compounds.

araT inactivation led to a 90 to 95% decrease of aminotransferase activity on aromatic amino acids and to 50 and 25% decreases of activity on methionine and leucine, respectively. In contrast, it did not alter aminotransferase activity on isoleucine and valine (data not shown).

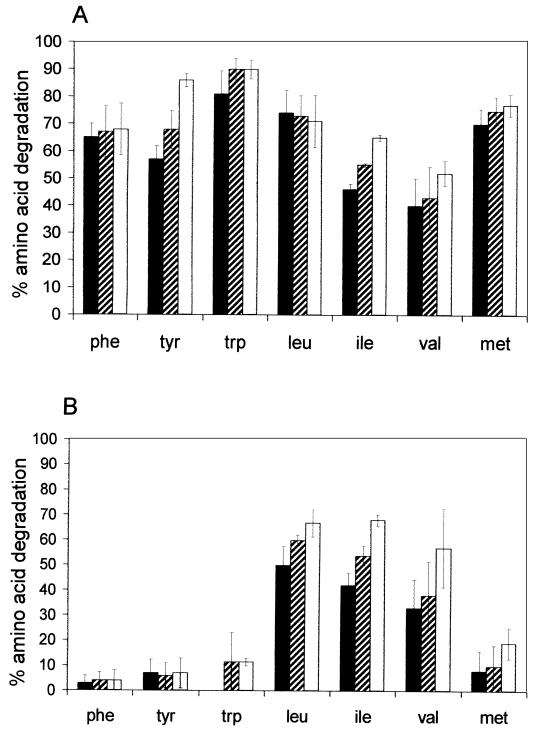

The role of AraT in the total catabolism of the aromatic and branched-chain amino acids and of methionine was studied by comparing amino acid degradation and metabolite formation by wild-type cells and cells of the araT mutant for 40 h in vitro. In the reaction medium without α-ketoglutarate, no degradation occurred (results not shown), while in the presence of α-ketoglutarate, the wild-type cells degraded all amino acids to aroma compounds. For example, after 40 h of incubation, around 80% of initial phenylalanine was degraded to various metabolites (Fig. 3), which were previously identified as phenylpyruvate, phenyllactate, and phenylacetate (43). Phenylpyruvate is the product of phenylalanine transamination, and phenyllactate and phenylacetate are further degradation products of phenylpyruvate. In contrast, the araT mutant was not capable of degrading phenylalanine (Fig. 3). The gene inactivation also prevented almost completely the degradation of tyrosine and tryptophan and decreased the degradation of leucine and methionine. In contrast, it did not affect isoleucine and valine degradation (Fig. 4).

FIG. 3.

Reverse-phase HPLC separation and identification of [3H]phenylalanine metabolites produced by incubation for 40 h of resting wild-type cells (WT) and araT mutant cells (ArAT−) in a reaction mixture containing α-ketoglutarate under the conditions described in Materials and Methods. C, refers to the reaction mixture with the cells of the wild type before incubation (time zero) (control).

FIG. 4.

Amino acid degradation by wild-type cells (A) and araT mutant cells (B) after incubation for 10 h (black bars), 20 h (hatched bars), and 40 h (white bars) of resting cells in reaction medium containing radiolabeled amino acids as a tracer and α-ketoglutarate, under conditions described in Materials and Methods. Abbreviations: phe, phenylalanine; tyr, tyrosine; trp, tryptophan; leu, leucine; ile, isoleucine; val, valine; met, methionine. Error bars indicate standard deviations of triplicate determinations.

Role of AraT in amino acid biosynthesis.

The wild-type strain grew similarly in CDM and in CDM without tryptophan and a little slower in the media lacking phenylalanine or tyrosine (Table 2). araT inactivation did not affect growth in CDM or in CDM without tryptophan and reduced the growth in CDM lacking phenylalanine. In contrast, it almost completely prevented growth in all CDM lacking tyrosine (Table 2). These results suggest that in medium without phenylalanine, another enzyme, maybe an aminotransferase, is expressed, that was not expressed in all media without tyrosine.

TABLE 2.

Parameters of growth curves of the wild-type strain and the araT mutant strain in minimal mediaa

| Medium | Wild type

|

Mutant

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k (h−1) | Maximum OD450 | Growth time (h) | k (h−1) | Maximum OD450 | Growth time (h) | |

| CDM | 1.00 | 1.05 | 7.5 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 6.5 |

| CDM + Phe, Tyr, and Trp | 0.56 | 0.90 | 12.4 | 0.04 | 0.26 | 30.0 |

| CDM + Phe | 0.68 | 0.91 | 12.4 | 0.21 | 0.66 | 18.3 |

| CDM + Tyr | 0.85 | 0.99 | 10.0 | 0.03 | 0.32 | 30.0 |

| CDM + Trp | 0.93 | 0.96 | 9.2 | 0.93 | 0.98 | 9.0 |

| CDM + Phe and Tyr | 0.56 | 0.90 | 11.3 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 30.0 |

| CDM + Tyr and Trp | 0.80 | 0.96 | 9.5 | 0.03 | 0.30 | 30.0 |

The maximum growth rates (k) are relative to that of the wild-type strain in CDM. The growth time is the time at maximum OD. The standard deviations for maximal growth rate and maximum OD and those for time at maximum OD are less than 5 and 10%, respectively.

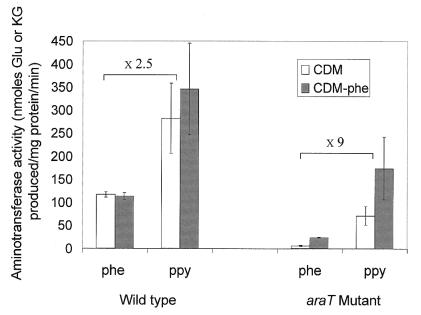

To test whether another aminotransferase was expressed in medium lacking phenylalanine, we compared aminotransferase activities in wild-type and mutant cells grown in the different media. In wild-type cells, the aminotransferase activity on phenylalanine was 2.5-fold lower than on phenylpyruvate (Fig. 5). The aminotransferase activities were not significantly affected by a lack of phenylalanine (Fig. 5) or tyrosine (results not shown). In mutant cells grown in CDM, the aromatic aminotransferase activities were much lower than in the wild-type cells, but above all, the ratios of activities on amino acid and α-ketoacid substrates were very different. Indeed, the phenylalanine aminotransferase activity of the mutant was about ninefold lower than its phenylpyruvate aminotransferase activity (Fig. 5), and a similar ratio was observed for tyrosine and hydroxyphenylpyruvate activities (results not shown). This means that the aminotransferase present in the mutant strain had a relative specific activity on α-ketoacid substrate more than threefold higher than that of AraT, which was the major aromatic aminotransferase of the wild-type cells. Moreover, the aminotransferase activities of the mutant were multiplied by about three in cells grown in medium without phenylalanine.

FIG. 5.

Phenylalanine (phe) and phenylpyruvate (ppy) aminotransferase activities of wild-type cells and araT mutant cells grown in CDM and CDM without phenylalanine (CDM-phe). Aminotransferase activities are expressed as glutamate (Glu) or α-ketoglutarate (KG) produced from α-ketoglutarate or glutamate. Error bars indicate standard deviations of triplicate determinations.

DISCUSSION

With the aim of evaluating the role of AraT in the amino acid biosynthesis and in the conversion of amino acids to aroma compounds, we cloned and sequenced the gene coding for AraT in L. lactis. Sequence and transcriptional analyses and Northern blotting showed that araT is transcribed as a single gene, from one of the two potential promoters located just upstream to a putative ρ-independent transcriptional terminator downstream of the gene. Gene fusions showed that transcription of araT is initiated in a fragment present just upstream of the coding sequence, although the potential promoters present in this fragment are not canonical (long spacing between the −10 and −35 boxes or a poor −10 box). araT is likely constitutively expressed, because, firstly, we observed that the concentration of aromatic amino acids in the growth medium did not significantly affect the phenylalanine aminotransferase activity. Secondly, the expression of the reporter under the control of the araT promoter is not significantly regulated by the composition of amino acids in the growth medium. Lastly, araT inactivation had no influence on its transcriptional regulation.

Homology analysis led us to classify AraT in aminotransferase I subfamily γ, described by Jensen and Gu (22). However, we propose a subdivision in this subfamily, separating the aspartate-specific aminotransferases from the aromatic-amino-acid-specific aminotransferases. Indeed, phylogenic analysis performed with the sequences of all members of subfamily γ, including AraT and homologous unidentified enzymes of the unfinished genomes of Streptococcus mutans, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Enterococcus faecalis, Bacillus subtilis, and Clostridium acetobutylicum, revealed a subdivision into two subclasses (data not shown). Subclass 1 contained AraT (which is the only well-characterized enzyme of the subclass), five unidentified AraT-homologous enzymes, and B. subtilis PatA, while subclass 2 contained only aspartate aminotransferases and three unidentified AspaT-homologous enzymes. This subdivision suggests that PatA of B. subtilis is an aromatic amino acid aminotransferase, rather than an aspartate aminotransferase as previously hypothesized (22).

araT seems to be widespread in gram-positive bacteria, since we detected by Southern hybridization a very homologous gene in all strains of L. lactis subsp. lactis and L. lactis subsp. cremoris tested and a less homologous gene in S. thermophilus. Also, we found high homologies with unidentified genes of S. mutans (68%), S. pneumoniae (67%), E. faecalis (62%), B. subtilis (48%), and C. acetobutylicum (36%). Although no gene with sufficient homology was detected in four Lactobacillus strains by Southern hybridization, an aminotransferase with activity on aromatic amino acids was present in these bacteria, since we observed an increased degradation of aromatic amino acids by these strains in the presence of an α-ketoacid (42a).

The construction of an araT mutant allowed the evaluation of the role of AraT in the catabolism and synthesis of amino acids. AraT is almost essential for the conversion of aromatic amino acids to aroma compounds and is also highly involved in leucine and methionine conversion. It is responsible for 90 to 95% of the aminotransferase activity towards aromatic amino acids, and there is no other catabolic pathway for aromatic amino acids in lactococci, since we did not observe any amino acid degradation in the absence of α-ketoacid (results not shown). AraT also contributes to leucine and methionine degradation, but contrary to what we found for the aromatic amino acids, other aminotransferases are also highly involved in their degradation. Such an aminotransferase, active on isoleucine, valine, leucine, and methionine, was recently purified from L. lactis subsp. cremoris NCDO763 (42a). Methionine might also be degraded by another pathway, initiated by cystathionine γ-lyase (5) or cystathionine β-lyase (1), although we did not detect methionine degradation in the medium without α-ketoglutarate. Gao et al. did not detect cystathionine lyase or methionine lyase activity in lactococci either (15). Our results suggest that AraT plays a role in cheese aroma development, since it is responsible for more than 90% of the aromatic amino acid conversion to α-ketoacids, which are precursors of major aroma compounds, such as phenylacetate or benzaldehyde, in cheese (44). It is also responsible for around 50% of the methionine conversion to α-keto-γ-methylthiobutyric acid, which was identified as the direct precursor of the aroma compound methanethiol (15).

AraT also plays a major role in the biosynthesis of phenylalanine and tyrosine, but it is not essential for tryptophan biosynthesis, since another pathway was previously revealed in L. lactis (3). Indeed, its inactivation slowed down the growth in medium deprived of phenylalanine, but above all, it highly affected the growth in all media deprived of tyrosine. However, after araT inactivation, a low residual aromatic aminotransferase activity was still present. Interestingly, this aminotransferase was ninefold more active on the α-ketoacid substrates than on amino acid substrates, compared to AraT, which was only 2.5-fold more active on the α-ketoacid substrates than on amino acid substrates, suggesting that this aminotransferase is specialized in the biosynthesis of aromatic amino acids. This is in agreement with the fact that this aminotransferase activity was repressed by the presence of phenylalanine in the medium. Surprisingly, the mutant did not grow in the medium lacking both phenylalanine and tyrosine, although the aminotransferase induced by a lack of phenylalanine was also active on hydroxyphenylpyruvate. On an other hand, the lack of tyrosine in the medium did not affect the growth of the wild-type strain, which has aromatic aminotransferase activity. These results suggest that tyrosine also plays a role in the regulation of the aminotransferase activity present in the mutant. Further investigations will be necessary to completely understand the regulation of these activities. The biosynthetic aromatic aminotransferase activity might be due to one of the other aminotransferase-homologous genes found in the genome of L. lactis subsp. lactis (32a). The presence of two or more aromatic aminotransferases with catabolic and biosynthetic functions was also demonstrated for several other bacteria, such as B. subtilis (28), E. coli (32), and P. aeruginosa (31, 42).

In conclusion, we characterized the gene coding for the major lactococcal AraT and we demonstrated that it belongs to a new subclass of aminotransferase subfamily I/γ. By using an araT mutant, we demonstrated the major role of AraT in the conversion of aromatic amino acids to flavor compounds and in aromatic-amino-acid biosynthesis. However, another biosynthetic aromatic aminotransferase is induced in the absence of phenylalanine in the culture medium.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The work was supported by a FAIR contract (CT97-3173) and a TMR grant (ERB4001GT954921) from the Commission of European Communities.

We thank M. Nardi, P. Renault, F. Rul, E. Maguin, and P. Tailliez for providing chromosomal DNAs of LAB strains and P. Renault for helpful discussions and for critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alting A C, Engels W J M, van Schalkwijk S, Exterkate F A. Purification and characterization of cystathionine β-lyase from Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris B78 and its possible role in flavor development in cheese. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:4037–4042. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.11.4037-4042.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schaffer A A, Zang J, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bardowski J, Ehrlich S D, Chopin A. Tryptophan biosynthesis genes in Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:6563–6570. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.20.6563-6570.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruinenberg P G, de Roo G, Limsowtin G K V. Purification and characterization of cystathionine γ-lyase from Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris SK11: possible role in flavor compound formation during cheese maturation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:561–566. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.2.561-566.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chopin A, Chopin M C, Moillo-Batt A, Langella P. Two plasmid-determined restriction and modification systems in Streptococcus lactis. Plasmid. 1984;11:260–263. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(84)90033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christensen K R, Reineccius G A. Aroma extract dilution analysis of aged Cheddar cheese. J Food Sci. 1995;60:218–220. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cocaign-Bousquet M, Garrigues C, Novak L, Lindley N D, Loubiere P. Rational development of a simple synthetic medium for the sustained growth of Lactococcus lactis. J Appl Bacteriol. 1995;79:108–116. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delorme C, Ehrlich D S, Renault P. Regulation of expression of the Lactococcus lactis histidine operon. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:2026–2037. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.7.2026-2037.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dumont J P, Roger S, Adda J. Etude des composés volatils neutres présents dans les fromages à pâte molle et croûte lavée. Lait. 1974;54:31–43. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunn H, Lindsay R C. Evaluation of the role of microbial Strecker-derived aroma compounds in unclean-type flavors of Cheddar cheese. J Dairy Sci. 1985;68:2859–2874. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Engels W J M, Dekker R, de Jong C, Neeter R, Visser S. A comparative study of volatile compounds in the water-soluble fraction of various types of ripened cheese. Int Dairy J. 1997;7:225–263. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao S, Oh D H, Broadbent J R, Johnson M E, Weimer B C, Steele J L. Aromatic amino acid catabolism by lactococci. Lait. 1997;77:371–381. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao S, Steele J L. Purification and characterization of oligomeric species of an aromatic amino acid aminotransferase from Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis S3. J Food Biochem. 1998;22:197–211. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao S, Mooberry E S, Steele J L. Use of 13C nuclear magnetic resonance and gas chromatography to examine methionine catabolism by lactococci. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:4670–4675. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.12.4670-4675.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gibson T J. Studies on the Eppstein Barr virus genome. Ph.D. thesis. Cambridge, England: University of Cambridge; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glatron M F, Rapoport G. Biosynthesis of the parasporal reclusion of Bacillus thuringiensis: half-life of its corresponding messenger RNA. Biochimie. 1972;54:1291–1301. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(72)80070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guthrie B D. Influence of cheese-related microflora on the production of unclean-flavored aromatic amino acid metabolites in Cheddar cheese. Ph.D. dissertation. Madison: University of Wisconsin—Madison; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holo H, Nes I F. High-frequency transformation, by electroporation, of Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris grown with glycine in osmotically stabilized media. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:3119–3123. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.12.3119-3123.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jensen R A, Stenmark S L. The ancient origin of a second microbial pathway for l-tyrosine biosynthesis in prokaryotes. J Mol Evol. 1975;4:249–259. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jensen R A. Biochemical pathways in prokaryotes can be traced backward through evolutionary time. Mol Biol Evol. 1985;2:92–108. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jensen R A, Gu W. Evolutionary recruitment of biochemically specialized subdivisions of family I within the protein superfamily of aminotransferases. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2161–2171. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.8.2161-2171.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kubickova J, Grosch W. Evaluation of potent odorants of Camembert cheese by dilution and concentration techniques. Int Dairy J. 1997;7:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loureiro dos Santos A L, Chopin A. Shotgun cloning in Streptococcus lactis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1987;42:209–212. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maguin E, Duwat P, Hege T, Ehrlich D, Gruss A. New thermosensitive plasmid for gram-positive bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5633–5638. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.17.5633-5638.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Milo C, Reineccius G A. Identification and quantification of potent odorants in regular-fat and low-fat mild Cheddar cheese. J Agric Food Chem. 1997;45:3590–3594. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morgan M E, Lindsay R C, Libbey L M. Identity of additional aroma constituents in milk cultures of Streptococcus lactis var. Maltigenes. J Dairy Sci. 1966;49:15–18. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(66)87777-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nester E W, Montoya A L. An enzyme common to histidine and aromatic amino acid biosynthesis in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1976;126:699–705. doi: 10.1128/jb.126.2.699-705.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Sullivan D J, Klaenhammer T R. Rapid mini-prep isolation of high-quality plasmid DNA from Lactococcus and Lactobacillus spp. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:2730–2733. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.8.2730-2733.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patel N, Pierson D L, Jensen R A. Dual enzymatic routes to l-tyrosine and l-phenylalanine via pretyrosine in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:5839–5846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patel N, Stenmark-Cox S L, Jensen R A. Enzymological basis of reluctant auxotrophy for phenylalanine and tyrosine in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:2972–2978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Powell T, Morrison J F. The purification and properties of the aspartate aminotransferase and aromatic-amino-acid aminotransferase from Escherichia coli. Eur J Biochem. 1978;87:391–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1978.tb12388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32a.Renault, P. Personal communication.

- 33.Renault P, Corthier G, Goupil N, Delorme C, Ehrlich S D. Plasmid vectors for Gram-positive bacteria switching from high to low copy number. Gene. 1996;183:175–182. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00554-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schormüller J. The chemistry and biochemistry of cheese ripening. Adv Food Res. 1968;16:231–234. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2628(08)60360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simon D, Chopin A. Construction of a vector plasmid family for molecular cloning in Streptococcus lactis. Biochimie. 1988;70:559–566. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(88)90093-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smid E J, Konings W N. Relationship between utilization of proline and proline-containing peptides and growth of Lactococcus lactis. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:5286–5292. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.9.5286-5292.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Song J, Jensen R A. PhhR, a divergently transcribed activator of the phenylalanine hydroxylase gene cluster of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:497–507. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.00131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Terzaghi B E, Sandine W E. Improved medium for lactic streptococci and their bacteriophages. Appl Microbiol. 1975;29:807–813. doi: 10.1128/am.29.6.807-813.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thirouin S, Rijnen L, Gripon J-C, Yvon M. Inventaire des activités de dégradation des acides aminés aromatiques et des acides aminés à chaines ramifiées chez Lactococcus lactis, abstr. M4. Paris, France: Club des bactéries lactiques—7ème Colloque; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Whitaker R J, Gaines C G, Jensen R A. A multispecific quintet of aromatic aminotransferases that overlap different biochemical pathways in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:13550–13556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xia T, Jensen R A. A single cyclohexadienyl dehydrogenase specifies the prephenate dehydrogenase and arogenate dehydrogenase components of the dual pathways to l-tyrosine in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:20033–20036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42a.Yvon, M. Personal communication.

- 43.Yvon M, Thirouin S, Rijnen L, Fromentier D, Gripon J-C. An aminotransferase from Lactococcus lactis initiates conversion of amino acids to cheese flavor compounds. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:414–419. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.2.414-419.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yvon M, Berthelot S, Gripon J-C. Adding α-ketoglutarate to semi-hard cheese curd highly enhances the conversion of amino acids to aroma compounds. Int Dairy J. 1999;8:889–898. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao G, Xia T, Song J, Jensen R A. Pseudomonas aeruginosa possesses homologues of mammalian phenylalanine hydroxylase and 4α-carbinolamine dehydratase/DCoH as part of a three-component gene cluster. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1366–1370. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.4.1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]