ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE

To analyze the number of yellow fever vaccine doses administered before and during the covid-19 pandemic in Brazil.

METHODS

This is an ecological, time series study based on data from the National Immunization Program. Differences between the median number of yellow fever vaccine doses administered in Brazil and in its regions before (from April/2019 to March/2020) and after (from April/2020 to March/2021) the implementation of social distancing measures in the country were assessed via the Mann-Whitney test. Prais-Winsten regression models were used for time series analyses.

RESULTS

We found a reduction in the median number of yellow fever vaccine doses administered in Brazil and in its regions: North (-34.71%), Midwest (-21.72%), South (-63.50%), and Southeast (-34.42%) (p < 0.05). Series showed stationary behavior in Brazil and in its five regions during the covid-19 pandemic (p > 0.05). Brazilian states also showed stationary trends, except for two states which recorded an increasing trend in the number of administered yellow fever vaccine doses, namely: Alagoas State (before: β = 64, p = 0.081; after: β = 897, p = 0.039), which became a yellow fever vaccine recommendation zone, and Roraima State (before: β = 68, p = 0.724; after: β = 150, p = 0.000), which intensified yellow fever vaccinations due to a yellow fever case confirmation in a Venezuelan State in 2020.

CONCLUSION

The reduced number of yellow fever vaccine doses administered during the covid-19 pandemic in Brazil may favor the reemergence of urban yellow fever cases in the country.

Keywords: Yellow Fever Vaccine, Vaccination Coverage, Immunization Programs, COVID-19, Time Series Studies

INTRODUCTION

National and international health agencies have recommended maintaining the implementation of immunization strategies during the coronavirus disease 2019 (covid-19) pandemic, mainly because immunization is an essential health strategy 1 . However, more than a third of countries in the world have interrupted their immunization services during the covid-19 pandemic 4 . Moreover, fear of getting infected by SARS-CoV-2, which is the etiologic agent of covid-19 5 , has contributed to reducing the demand for vaccination in health services, even in countries which continued to implement immunization strategies.

This process has had a negative impact on the recommended vaccine coverage in several countries and regions worldwide. Consequently, such low vaccination coverage during the covid-19 pandemic may cause yellow fever (YF) outbreaks, according to a study assessing the impact of vaccination interruption during the covid-19 pandemic in 10 countries 6 . In Ethiopia and Nigeria, a one-year delay in campaigns against YF can increase approximately one death per 100,000 people, highlighting the risk of virus circulation in these populations 6 .

Yellow fever is a hemorrhagic disease caused by the yellow fever virus, which stands out among vaccine-preventable infectious diseases 7 . It is endemic to 47 low- and middle-income countries in the African and South American continents. Moreover, YF features varying severity and lethality levels and accounts for at least 60,000 deaths a year 6 . The yellow fever lethality rate in Brazil is also quite high. According to estimates, the disease accounted for 47.8% of death cases in the country from 2000 to 2021, on average 10 .

Yellow fever vaccination was introduced in Brazil by its National Immunization Program (PNI) in 1937. It was provided free of charge by primary care services to the population in the age group between nine months–59 years old. Such a strategy enabled ruling out urban YF in the country and consolidated itself as the main way to control YF 9 , 11 . Based on a systematic immunization schedule, the National Immunization Program ensures the vaccination of individuals who live in or travel to states located in the Áreas com Recomendação de Vacina (Vaccine Recommendation Zones – ACRV), in which YF transmission can take place 11 , 12 .

However, PNI has progressively expanded ACRVs in Brazil from 2014 onward. Such an expansion process comprised states and municipalities which, until then, were classified as free from YF virus circulation. It was implemented in response to surveillance strategies aimed at epizootics (death of non-human primates) and the YF epidemic, which started in the Midwest in 2016. The aforementioned epidemic accounted for 2,114 disease cases and for more than 700 deaths, most of which were recorded in regions that, until then, were YF-free. It was the worst YF outbreak in the history of the country 12 , 13 . Since 2020, the National Immunization Program has expanded its yellow fever vaccination recommendation to the entire national territory 11 , 12 .

The increased number of YF cases recorded during this outbreak has raised red flags to the likelihood of urban YF reemergence in Brazil since Aedes aegypti - which is a potential vector of the YF virus found in all Brazilian urban regions - can infect individuals with YF who will transmit the virus to other susceptible individuals and, consequently, perpetuate the urban cycle of the YF virus 7 , 10 . Although the immunization of individuals living in, or travelling to, ACRVs in Brazil is mandatory, vaccination coverage rates have remained below the targets established by the Ministry of Health 12 .

Many factors have favored such a vaccination coverage reduction, namely: precariousness of the Brazilian Unified Health System (SUS), implementation of the new immunization information system (SI-PNI), social and cultural aspects affecting vaccination acceptance, and inconstant availability of immunobiological drugs in primary care services 9 , 14 . Furthermore, vaccination coverage in Brazil is heterogeneous 16 , 19 . Thus, investigating and monitoring low vaccination coverage zones is a strategic axis of good management practices focused on immunization programs, as recommended by World Health Organization 20 .

This study aimed to investigate the YF vaccination status in Brazil and time variations in the number of YF vaccine doses administered in Brazilian states and regions before and after the onset of the covid-19 pandemic by considering that the reduction in YF vaccine coverage rates in the country may have been worsened by the covid-19 pandemic and that YF incidence in large-sized cities may favor urban YF reemergence. Assumingly, results in this study may guide health strategies and policies focused on priority geographic zones that have shown decreased rates of YF vaccine doses administered over time.

METHODS

Study Design

This is an ecological study conducted with data from the information system of the National Immunization Program (SI-PNI), available at http://sipni.datasus.gov.br/. SI-PNI provides the number of vaccine doses administered countrywide, stratified by month.

Data Collection

Collected data refer to the number of YF vaccine doses administered to the Brazilian population from April 2019 to March 2021. Data extraction was based on the number of doses administered to the target audience – namely: nine-month- (first dose) and four-year-old children (second dose) – on a monthly basis.

Variables

The number of administered doses was used as the dependent variable, whereas independent variables comprised geographic information about the five regions in the country (North, Northeast, Midwest, Southeast, and South), all 26 Federation Units and the Federal District, and all 5,568 Brazilian municipalities.

Statistical Analysis

First, YF vaccine doses administered before (from April 2019 to March 2020) and after (April to March 2021) the implementation of social distancing measures in Brazil and its regions were summed. Next, differences between the median number of doses administered before and after the implementation of social distancing measures were evaluated by the Mann-Whitney U test, by considering interquartile ranges (IQR) at 5% significance level.

Variation rates in the median number of administered doses were estimated by the following equation:

[(median number of doses administered before the implementation of social distancing measures − median number of doses administered after the implementation of social distancing measures)/median number of doses administered before the implementation of social distancing measures x 100].

These analyses were processed in the Statistical Package for Social Sciences software (IBM-SPSS, v.19, IBM, Chicago, IL).

Moreover, time series analysis was used to check the effect of social distancing measures on time series observed for the number of administered YF vaccine doses, based on Prais-Winsten linear regression models 21 .

Time series in the absolute number of YF vaccine doses administered on a monthly basis from April 2019 to March 2020 (before the implementation of social distancing measures) and from April 2020 to March 2021 (during social distancing measures) were estimated. Data analysis also considered the absolute number of doses administered every month countrywide, as well as in its regions (North, Northeast, South, Southeast, and Midwest) and states. Prais-Winsten regression models were used to assess either significant increasing or decreasing trends in the number of administered YF vaccine doses. This model is based on a linear regression analysis. It aims at correcting the autocorrelation effect and is recommended for time series studies 21 .

The indicator of interest (absolute number of administered doses) set for each month was used as the outcome variable in this analysis, whereas the surveyed month was used as an explanatory variable. There was a significant increasing or decreasing trend in the absolute number of doses administered when the model slope was different from zero and its p-value was equal to or lower than 0.05 (p ≤ 0.05). A positive regression coefficient indicates an increased variation in the absolute number of monthly-administered doses within the evaluated period, whereas a negative regression coefficient indicates a reduced variation in this parameter.

A trend in the absolute number of doses administered was considered stationary whenever a statistically insignificant difference in the absolute number of monthly-administered doses was identified (p ≥ 0.05) in the evaluated period. Model accuracy was expressed by the coefficient of determination (R2). The Durbin-Watson test was applied to the entire investigated period to check the incidence of autocorrelation in the series 22 .

Time series trend analyses were performed in the professional statistical software Stata, version 14.

Ethical Aspects

Since this study was based on freely accessible data, it did not require submission to a research ethics committee, as determined by the National Health Council Resolution n. 466/2012.

RESULTS

In total, 11,499,231 yellow fever vaccine doses were administered countrywide from April 2019 to March 2021, of which 4,533,135 (39.42%) after the implementation of social distancing measures. The median number of YF vaccine doses administered before the implementation of social distancing measures was 518,510 (IQR = 432,140–705,034), whereas the median number of vaccine doses administered when these recommendations were in force was 349,028 (IQR = 306,190–395,746). This outcome has indicated a 48.55% reduction (p = 0.003) in the number of administered YF vaccine doses.

All regions showed a reduced median number of YF vaccine doses administered during social distancing, except for the Northeastern region, which recorded an increased median number of YF vaccine doses administered during this period (p < 0.05).

States in the Northeastern region, such as Alagoas, Ceará, Paraíba, and Pernambuco - which became ACRVs in 2020 - showed an increased median number of YF vaccine doses administered during social distancing. Other Brazilian states showed a reduced median number of administered doses which ranged from 73.93% (in Roraima State) to 2.91% (in Espírito Santo State); p < 0.05 ( Table 1 ).

Table 1. Median and rate of variation in the median number of yellow fever vaccine doses administered in the Brazilian population from April 2019 to March 2020 and from April 2020 to March 2021. National Immunization Program, Brazil.

| States and Regions | Apr/19–Mar/20 Median (P25–P75) | Apr/20–Mar/21 Median (P25–P75) | Variation (%) | pa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brazil | 518,510 (432,140–705,034) | 349,028 (306,190–395,746) | -48.55 | 0.003 |

| North | 50,108 (44,692–51,908) | 32,715 (26,462–36,436) | -34.71 | 0.000 |

| Acre | 1,818 (1,645–2,197) | 1,080 (975–1,318) | -40.59 | 0.000 |

| Amapá | 1,962 (1,887–7,736) | 1,811 (889 – 3,698) | -7.69 | 0.000 |

| Amazonas | 13,900 (12,514–15,589) | 10,966 (7,606–12,429) | -21.10 | 0.000 |

| Pará | 16,540 (16,084–17,783) | 11,466 (9,239–13,117) | -30.67 | 0.000 |

| Rondônia | 5,486 (4,449–5,835) | 3,874 (3,042–4,284) | -29.38 | 0.000 |

| Roraima | 6,623 (5,310–7,217) | 1,726 (1,370–2,465) | -73.93 | 0.000 |

| Tocantins | 3,273 (2,629–3,612) | 2,815 (2,445–2,958) | -13.99 | 0.000 |

| Northeast | 58,173 (51,450–89,927) | 108,070 (91,645–149,778) | +85.77 | 0.003 |

| Alagoas | 824 (719–1,414) | 5,025 (265 – 8,214) | +509.83 | 0.000 |

| Bahia | 26,101 (22,959–31,814) | 17,716 (15,645–19,779) | -32.12 | 0.000 |

| Ceará | 1,519 (1,392–2,253) | 16,826 (8,540–31,387) | +1,007.70 | 0.000 |

| Maranhão | 14,954 (13,416–16,586) | 9,399 (7,685–12,399) | -37.14 | 0.000 |

| Paraíba | 1,080 (988–1,314) | 7,268 (2,601–8,531) | +524.40 | 0.000 |

| Pernambuco | 3,290 (2,833–29,374) | 63,087 (31,010–76,894) | +1,817.53 | 0.000 |

| Piauí | 6,381 (5,350–7,382) | 5,077 (4,314–5,450) | -20.43 | 0.000 |

| Rio Grande do Norte | 1,596 (1,253–1,674) | 1,532 (1,296–2,328) | -4.01 | 0.000 |

| Sergipe | 825 (707–949) | 307 (187–334) | -62.78 | 0.000 |

| Midwest | 38,328 (32,905–47,397) | 30,002 (26,385–34,161) | -21.72 | 0.017 |

| Distrito Federal | 6,876 (6,205–10,984) | 6,034 (5,752–7,433) | -12.24 | 0.000 |

| Goiás | 13,850 (12,817–14,678) | 10,157 (9,331–12,115) | -26.66 | 0.000 |

| Mato Grosso | 11,186 (9,655–11,945) | 8,118 (7,172–8,913) | -27.42 | 0.000 |

| Mato Grosso do Sul | 5,859 (5,292–7,116) | 5,117 (4,912–5,754) | -12.66 | 0.000 |

| Southeast | 171,181 (151,379–204,971) | 112,257 (98,569–124,014) | -34.42 | 0.000 |

| Espírito Santo | 7,981 (7,004–12,891) | 7,748 (6,371–8,664) | -2.91 | 0.000 |

| Minas Gerais | 39,856 (33,706–48,029) | 28,281 (25,697–32,761) | -29.04 | 0.000 |

| Rio Janeiro | 20,704 (18,955–24,538) | 15,645 (12,986–17,591) | -24.43 | 0.000 |

| São Paulo | 105,524 (95,106–123,009) | 59,876 (51,960–65,557) | -43.25 | 0.000 |

| South | 174,257 (153,009–272,348) | 63,590 (54,659–78,093) | -63.50 | 0.000 |

| Paraná | 56,869 (47,954–90,699) | 28,450 (22,136–36,574) | -49.97 | 0.000 |

| Santa Catarina | 69,415 (62,682–123,464) | 19,441 (16,330–22,289) | -71.99 | 0.000 |

| Rio Grande do Sul | 35,480 (24,488–50,338) | 15,609 (13,943–20,944) | -56.00 | 0.000 |

P: percentile.

a Mann-Whitney test (difference between medians).

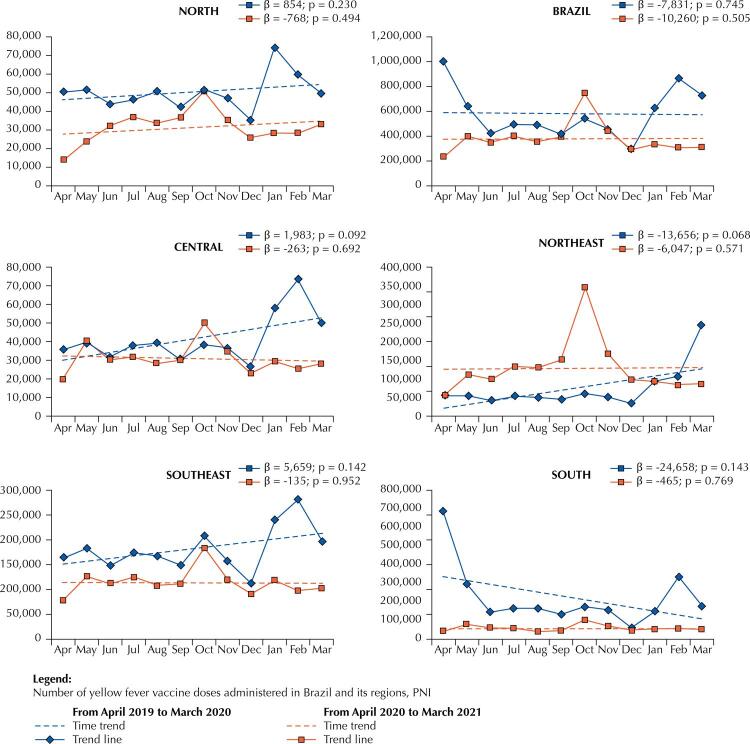

Figure shows the time series referring to the number of YF vaccine doses administered in Brazil and in its regions. There was a reduction in the absolute number of YF vaccine doses administered in April 2020, when the country implemented social distancing measures. Trends in the absolute number of doses administered remained stationary in the two investigated periods in Brazil and in its regions (p ≥ 0.05). However, its slope reduction speed (β) has increased during social distancing.

Figure. Time trends in the number of yellow fever vaccine doses administered before and after the implementation of social distancing measures in Brazil and in its regions. National Immunization Program (PNI). From April 2019 to March 2021, Brazil.

Tables 2 and 3 show the number of vaccine doses administered per month and the time trends referring to the number of YF vaccine doses administered in Brazilian states during the evaluated periods. The time trend observed in the number of vaccine doses changed from increasing to stationary in the Federal District, as well as in Espírito Santo and Piauí states. Distrito Federal, Espírito Santo, and Rio Grande do Norte showed an increasing trend before the pandemic (p < 0.05) which were stationary after the pandemic (p > 0.05). Alagoas and Roraima had stationary trends before the pandemic (p > 0.05), and increasing ones after it (p < 0.05).

Table 2. Time trends in the number of yellow fever vaccine doses administered before the implementation of social distancing measures in Brazil, based on Federation Units. National Immunization Program. From April 2019 to March 2020, Brazil.

| States | Apr/19 | May/19 | Jun/19 | Jul/19 | Aug/19 | Sep/19 | Oct/19 | Nov/19 | Dec/19 | Jan/20 | Feb/20 | Mar/20 | p | Slope (β) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acre | 1,790 | 1,847 | 1,679 | 1,917 | 1,634 | 1,444 | 1,550 | 1,865 | 1,741 | 3,065 | 2,903 | 2,291 | 0.118 | 78 |

| Alagoas | 761 | 777 | 628 | 639 | 705 | 779 | 870 | 993 | 1,537 | 1,675 | 1,698 | 1,047 | 0.081 | 64 |

| Amapá | 1,965 | 2,019 | 2,092 | 2,132 | 2,184 | 1,289 | 2,105 | 1,946 | 1,616 | 1,960 | 1,341 | 1,018 | 0.01 | -67.87 |

| Amazonas | 14,765 | 14,432 | 13,045 | 12,676 | 15,013 | 13,369 | 12,460 | 11,390 | 8,263 | 32,468 | 19,372 | 15,782 | 0.227 | 580 |

| Bahia | 25,532 | 24,413 | 16,884 | 26,068 | 26,135 | 22,475 | 32,732 | 27,514 | 15,447 | 32,161 | 38,954 | 30,774 | 0.066 | 927 |

| Ceara | 2,369 | 2,589 | 2,302 | 2,106 | 1,524 | 1,514 | 1,458 | 1,382 | 1,549 | 1,273 | 1,219 | 1,423 | 0.004 | -105 |

| Distrito Federal | 6,238 | 7,136 | 5,666 | 6,491 | 8,656 | 6,617 | 8,189 | 6,194 | 5,453 | 11,761 | 21,773 | 16,711 | 0.045 | 968 |

| Espírito Santo | 6,836 | 7,831 | 5,883 | 7,765 | 8,131 | 6,844 | 9,350 | 10,476 | 7,486 | 13,697 | 25,898 | 14,291 | 0.011 | 1,078 |

| Goiás | 13,882 | 14,693 | 11,522 | 13,818 | 14,635 | 12,659 | 13,293 | 13,533 | 8,503 | 21,541 | 23,329 | 14,237 | 0.203 | 434 |

| Maranhão | 17,121 | 17,877 | 14,174 | 15,742 | 13,496 | 13,019 | 15,560 | 13,390 | 8,997 | 14,348 | 16,659 | 16,369 | 0.519 | -159 |

| Mato Grosso | 10,889 | 12,017 | 9,390 | 11,134 | 10,452 | 7,216 | 11,238 | 11,319 | 7,694 | 15,923 | 18,555 | 11,730 | 0.185 | 360 |

| Mato Grosso do Sul | 5,023 | 5,846 | 5,285 | 6,621 | 5,969 | 4,268 | 5,873 | 5,758 | 5,315 | 8,763 | 10,194 | 7,281 | 0.056 | 281 |

| Minas Gerais | 39,622 | 46,445 | 36,274 | 40,091 | 35,271 | 26,432 | 48,558 | 33,185 | 21,038 | 55,302 | 63,785 | 43,780 | 0.403 | 888 |

| Pará | 16,444 | 17,421 | 16,324 | 17,836 | 17,789 | 14,359 | 16,126 | 16,070 | 10,163 | 19,060 | 17,766 | 16,636 | 0.695 | -68 |

| Paraíba | 1,295 | 1,096 | 974 | 1,064 | 1,321 | 1,356 | 1,330 | 882 | 1,057 | 1,032 | 1,111 | 607 | 0.116 | -33 |

| Paraná | 164,056 | 95,300 | 63,701 | 47,877 | 58,596 | 48,187 | 53,704 | 45,166 | 26,202 | 55,142 | 110,709 | 76,899 | 0.253 | -5,167 |

| Pernambuco | 3,055 | 2,759 | 2,491 | 3,326 | 3,485 | 3,291 | 3,194 | 2,462 | 3,289 | 38,004 | 40,089 | 188,155 | 0.061 | 12,142 |

| Piauí | 5,154 | 6,134 | 5,767 | 6,629 | 5,837 | 5,211 | 7,392 | 6,893 | 4,668 | 7,653 | 8,866 | 7,354 | 0.024 | 201 |

| Rio de Janeiro | 20,843 | 23,338 | 18,911 | 20,566 | 19,087 | 15,634 | 24,938 | 19,144 | 13,676 | 26,616 | 25,571 | 21,239 | 0.512 | 199 |

| Rio Grande do Norte | 1,678 | 1,650 | 1,637 | 1,555 | 1,829 | 1,760 | 1,662 | 1,216 | 1,101 | 1,367 | 1,433 | 1,009 | 0.016 | -55 |

| Rio Grande do Sul | 28,600 | 25,282 | 22,891 | 60,915 | 51,414 | 24,224 | 40,303 | 36,537 | 21,107 | 34,423 | 95,760 | 47,111 | 0.154 | 2,449 |

| Rondônia | 5,380 | 5,743 | 5,121 | 5,543 | 4,226 | 3,567 | 5,851 | 5,790 | 4,056 | 5,430 | 6,915 | 5,854 | 0.487 | 60 |

| Roraima | 7,100 | 6,713 | 3,025 | 3,794 | 7,008 | 6,433 | 10,568 | 6,460 | 7,257 | 7,589 | 6,533 | 4,936 | 0.724 | 68 |

| Santa Catarina | 495,822 | 181,492 | 65,022 | 67,809 | 61,903 | 71,022 | 86,503 | 82,199 | 26,136 | 67,630 | 135,785 | 59,161 | 0.075 | -23,142 |

| São Paulo | 96,808 | 105,584 | 88,323 | 105,986 | 105,465 | 100,185 | 124,369 | 94,539 | 69,218 | 145,426 | 166,707 | 118,931 | 0.108 | 3,505 |

| Sergipe | 1,296 | 1,173 | 786 | 957 | 644 | 870 | 865 | 739 | 723 | 702 | 927 | 546 | 0.009 | -41 |

| Tocantins | 3,055 | 3,412 | 2,816 | 2,567 | 3,346 | 1,942 | 3,355 | 3,679 | 2,355 | 4,842 | 4,898 | 3,201 | 0.081 | 115 |

Table 3. Time trends in the number of yellow fever vaccine doses administered after the implementation of social distancing measures in Brazil, based on Federation Units. National Immunization Program. From April 2020 to March 2021, Brazil.

| States | Apr/20 | May/20 | Jun/20 | Jul/20 | Aug/20 | Sep/20 | Oct/20 | Nov/20 | Dec/20 | Jan/21 | Feb/21 | Mar/21 | p | Slope (β) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acre | 696 | 953 | 967 | 1,071 | 1,037 | 1,461 | 1,896 | 1,331 | 1,089 | 1,281 | 1,000 | 1,186 | 0.212 | -0.3 |

| Alagoas | 183 | 201 | 150 | 457 | 3,201 | 4,512 | 16,952 | 8,491 | 5,538 | 7,384 | 6,990 | 8,843 | 0.039 | 897 |

| Amapá | 214 | 192 | 520 | 975 | 817 | 1,043 | 1,112 | 473 | 869 | 1,184 | 1,129 | 730 | 0.058 | 59 |

| Amazonas | 1,786 | 7,913 | 12,398 | 12,440 | 11,863 | 12,337 | 20,218 | 12,451 | 8,298 | 6,066 | 7,504 | 10,070 | 0.263 | -637 |

| Bahia | 13,119 | 18,899 | 19,131 | 21,932 | 17,963 | 19,996 | 24,719 | 16,629 | 13,965 | 16,576 | 15,335 | 17,470 | 0.133 | -491 |

| Ceara | 1,208 | 4,436 | 7,603 | 11,351 | 15,863 | 33,416 | 83,355 | 38,839 | 25,301 | 17,789 | 17,861 | 11,864 | 0.872 | -644 |

| Distrito Federal | 5,719 | 13,080 | 7,505 | 6,513 | 5,934 | 6,132 | 11,340 | 7,219 | 4,728 | 5,937 | 4,415 | 5,852 | 0.063 | -342 |

| Espirito Santo | 4,148 | 9,094 | 7,674 | 8,795 | 7,663 | 8,025 | 13,326 | 8,274 | 6,158 | 7,822 | 6,305 | 6,572 | 0.944 | -14 |

| Goiás | 6,100 | 13,851 | 10,341 | 11,245 | 9,974 | 10,854 | 16,981 | 12,405 | 7,995 | 9,376 | 9,316 | 9,974 | 0.883 | -36 |

| Maranhão | 6,039 | 7,444 | 10,661 | 13,533 | 11,537 | 12,687 | 16,073 | 8,409 | 6,951 | 9,195 | 8,477 | 9,603 | 0.374 | -369 |

| Mato Grosso | 4,997 | 9,172 | 7,653 | 8,345 | 7,892 | 8,399 | 13,653 | 9,036 | 6,171 | 8,546 | 7,096 | 7,400 | 0.532 | -126 |

| Mato Grosso do Sul | 3,230 | 5,055 | 5,264 | 5,791 | 4,932 | 5,117 | 8,169 | 6,257 | 4,375 | 5,644 | 4,906 | 5,117 | 0.806 | -28 |

| Minas Gerais | 25,524 | 38,181 | 32,384 | 32,887 | 28,101 | 28,462 | 41,883 | 28,022 | 23,577 | 28,559 | 23,977 | 26,216 | 0.075 | -710 |

| Pará | 5,796 | 6,956 | 10,378 | 13,458 | 11,729 | 13,315 | 15,493 | 12,525 | 8,860 | 11,203 | 10,641 | 12,500 | 0.888 | -53 |

| Paraíba | 87 | 495 | 1,721 | 5,241 | 6,964 | 6,618 | 30,159 | 10,210 | 7,572 | 8,605 | 7,652 | 8,312 | 0.232 | 860 |

| Paraná | 21,123 | 39,622 | 30,772 | 29,118 | 20,423 | 25,178 | 43,207 | 38,509 | 27,494 | 28,284 | 28,616 | 20,704 | 0.33 | -784 |

| Pernambuco | 38,147 | 76,968 | 57,166 | 76,672 | 69,198 | 69,009 | 163,931 | 77,011 | 35,487 | 29,518 | 25,455 | 27,963 | 0.495 | -2,694 |

| Piauí | 2,410 | 4,293 | 5,178 | 5,465 | 5,373 | 5,591 | 8,624 | 5,408 | 4,013 | 4,977 | 4,511 | 4,378 | 0.429 | -137 |

| Rio de Janeiro | 7,653 | 12,798 | 12,094 | 15,373 | 15,917 | 16,124 | 34,457 | 19,329 | 13,553 | 17,760 | 14,551 | 17,086 | 0.298 | 642 |

| Rio Grande do Norte | 140 | 263 | 1,254 | 1,443 | 1,851 | 2,131 | 4,446 | 2,612 | 2,394 | 1,424 | 1,491 | 1,573 | 0.884 | -28 |

| Rio Grande do Sul | 12,745 | 21,885 | 18,121 | 17,521 | 13,776 | 15,615 | 36,966 | 23,411 | 14,121 | 15,603 | 13,884 | 14,739 | 0.51 | -520 |

| Rondônia | 2,556 | 4,100 | 3,871 | 4,364 | 3,981 | 3,877 | 5,714 | 4,346 | 3,015 | 2,805 | 3,124 | 3,364 | 0.145 | -145 |

| Roraima | 751 | 1,101 | 1,340 | 1,736 | 1,677 | 1,880 | 2,430 | 1,462 | 1,717 | 2,896 | 2,584 | 2,477 | 0 | 150 |

| Santa Catarina | 19,798 | 27,866 | 20,710 | 19,085 | 13,339 | 15,606 | 29,530 | 19,003 | 12,464 | 18,503 | 22,290 | 22,287 | 0.762 | -140 |

| São Paulo | 40,687 | 66,011 | 60,152 | 68,357 | 56,159 | 59,600 | 94,071 | 64,196 | 48,003 | 63,606 | 52,734 | 51,703 | 0.939 | -88 |

| Sergipe | 88 | 108 | 170 | 241 | 339 | 300 | 315 | 457 | 315 | 342 | 320 | 251 | 0.979 | -0,5 |

| Tocantins | 2,141 | 3,006 | 2,851 | 2,939 | 2,525 | 2,965 | 4,208 | 2,523 | 1,995 | 2,887 | 2,419 | 2,779 | 0.874 | -8 |

DISCUSSION

There was a significant decrease in the median number of YF vaccine doses administered in Brazil and its Northern, Midwestern, Southern, and Southeastern regions, as well as an increase in the median number of YF vaccine doses administered in the Northeast after the adoption of non-pharmacological measures in response to the covid-19 pandemic. The time trends observed for the number of YF vaccine doses administered in Brazil and its Southeastern, Southern, and Midwestern regions were stationary. However, they showed a faster slope reduction speed during the implementation of social distancing measures imposed by the covid-19 pandemic.

Alagoas State became an ACRV in 2020 10 and Roraima State has intensified yellow fever vaccine administrations due to a YF case confirmed in the Venezuelan State of Bolívar (bordering Roraima State) in 2020 7 , which may explain the increasing trend in the number of vaccine doses administered in these Brazilian states. Furthermore, these findings can be explained by the sharp decrease in the number of YF vaccine doses administered in April 2020, which preceded the abrupt increase in the number of YF vaccine doses administered in the subsequent months until the end of the evaluated period.

Findings in this study have indicated that some states in ACRVs, and those which reported recent cases of wild YF and epizootics, showed decline trends in the number of YF vaccine doses administered within the analyzed period. Santa Catarina State, in Southern Brazil, reported 151 epizootic cases and 26 YF cases in humans from July 2020 to January 2021, indicating YF virus circulation in the State 10 , 23 . Therefore, the decreasing trend in the number of YF vaccine doses identified in this study points toward the risk of sustained YF virus transmission in Santa Catarina State, as well as a risk of urban YF incidence since approximately 55% of its population lives in urban areas 24 .

Moreover, Santa Catarina, Paraná, and Rio Grande do Sul States, which are also located in Southern Brazil, became ACRVs in 2017, when evidence of YF virus circulation was found and its likely dispersion route, identified: it started in areas of typical Atlantic Forest vegetation in São Paulo State (Southeastern Brazil), reaching the South 11 .

Accordingly, the evidence of YF virus circulation associated with a reduction in the median number of administered YF vaccine doses and the downward trend in the number of doses administered in the population living in the South has evidenced the risk of sustained YF virus transmission, which can lead to increasing YF-related mortality rates in humans. The inclusion of Alagoas, Ceará, Maranhão, Paraíba, and Pernambuco States (Northeastern Brazil) in the ACRV 11 group in 2019 may have contributed to the increasing trend in the number of YF vaccine doses administered throughout the sanitary measures adopted during the covid-19 pandemic.

However, in addition to studies focused on investigating the administration of YF vaccine doses, it is necessary to conduct research focused on assessing YF vaccine coverage to assess whether the target population living in these states was properly immunized and reached the vaccination coverage goal of at least 95% set by the PNI 11 , 25 .

Although YF cases in humans have not yet been identified in these Northeastern states, they have become ACRVs, as determined by the Secretariat of Health Surveillance 11 . This strategy was established in response to the progressive increase of YF and epizootic cases in states outside the Amazon region, which, until then, was the only region within the Brazilian territory known to be endemic for YF 7 , 12 . In addition to the progressive increase in the number of YF cases, an outbreak took place in Brazil between 2016 and 2018. It accounted for the largest number of reported cases in the history of the country and favored YF virus circulation in areas which, until then, were free from its circulation 13 . There were also records of YF cases and death of foreign individuals who were in Brazil at the time of the outbreak 12 .

Although the covid-19 pandemic also plagued the richest regions in Brazil, it is worth emphasizing that it has worsened health inequalities and increased social and ethnic-racial disparities in the country. It mainly affected its poorest regions, such as Northern Brazil 26 . It historically shows the worst immunization indicators in the country, in addition to precarious conditions of primary care services, which account for providing immunobiological drugs to the population for free 16 , 18 . Associated with these factors, the collapse of health services in some Northern states, due to the high demand for hospital beds for patients with covid-19, may have contributed to reducing the population’s demand for immunization services 27 , 28 and directly impacting the number of YF vaccine doses administered in the region.

Despite increasing trends in the number of YF vaccine doses administered in the Northern region, it is worth emphasizing that we observed fluctuations. April 2020 recorded an abrupt drop in the number of administered YF vaccine doses, though there was a progressive increase in the number of YF vaccine doses administered after April. However, it was insufficient to reach the number of doses administered before the pandemic, which resulted in a 54.22% decrease in the median number of administered YF vaccine doses.

More than a year after the first case of covid-19 in Brazil, immunization rates against this disease are still low in the Brazilian population 29 . Moreover, high transmission and sustained mortality estimates point toward the long-term maintenance of social distancing strategies 30 . Given this scenario, it is necessary to adopt health strategies and policies capable of ensuring the population’s access to YF vaccination. Otherwise, the country will be at risk of living with overlapping epidemics (covid-19 and YF cases and deaths) which may worsen the severe health crisis observed in the country. Furthermore, it is essential to identify the states and regions showing a decreasing trend in the number of administered YF vaccine doses to help to develop strategies focused on improving YF-immunization indicators and reduce the likelihood of YF cases in humans and urban YF reemergence.

Among the limitations of this study, it is worth mentioning its information bias, which is intrinsic to studies conducted with secondary data. However, we used population data available for the investigated period and the generalization of results was relatively safe for national estimates. Moreover, we employed methodological rigor at all stages of this study to control for biases. Also, it is worth emphasizing that, to the best of our knowledge, this study was the first to portray the yellow fever vaccine status in Brazil before and after the covid-19 pandemic.

Assumingly, results in this study may contribute to surveillance strategies focused on YF and epizootic cases to point out priority areas for the establishment of health strategies and policies focused on this particular issue. Furthermore, this study stood out for analyzing variations in YF vaccine dose indicators, both based on location and time, and it enabled us to identify health inequalities and YF vaccination rates before and during the pandemic.

Significant inequalities mark Brazil. Thus, given its continental territorial extension, it is necessary to identify the areas mostly affected by decreased vaccination coverage during the covid-19 pandemic. Therefore, this research can contribute to identifying priority areas that are mostly vulnerable to low YF vaccine coverage. It is worth emphasizing that immunization is essential to achieving health equity. Therefore, identifying vulnerable areas can help to guide public policies and health strategies to improve immunization indicators, which is a goal included in the 2030 United Nations’ Agenda for Sustainable Development Goals.

We found evidence of worsened YF vaccine indicators in Brazil after the adoption of the sanitary measures set to cope with the covid-19 pandemic. Due to the worrying scenario of expansion in YF virus circulation areas in Brazil, as well as the reduced number of YF vaccine doses administered during the covid-19 pandemic, it is necessary to adopt health strategies and policies focused on improving these immunization indicators, especially in states and regions in which YF or epizootic cases were identified. Furthermore, it is imperative to identify areas showing the worst immunization indicators to support surveillance actions and public policies, as well as to reduce inequalities.

REFERENCES

- 1..Organização Pan-Americana da Saúde. O programa de imunização no contexto da pandemia da COVID-19; versão 2. Washington, DC: OPAS; 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 24]. Available from: https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/52102

- 2..Saxena S, Skirrow H, Bedford H. Routine vaccination during covid-19 pandemic response. BMJ. 2020;369:m2392. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m2392 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3..World Health Organization. Framework for decision-making: implementation of mass vaccination campaigns in the context of COVID-19: interim guidance. Geneva (CH): WHO; 2020 [cited 2021 Apr 5]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Framework_Mass_Vaccination-2020.1

- 4..World Health Organization. Second round of the national pulse survey on continuity of essential health services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Geneva (CH): WHO; 2021 [cited 2021 Jun 25]. Annex 1: National pulse survey on continuity of essential health services during the COVID-19 pandemic; p.65-86. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-EHS-continuity-survey-2021.1

- 5..Silva LLS, Lima AFR, Polli DA, Razia PFS, Pavão LFA, Cavalcanti MAFH, et al. Social distancing measures in the fight against COVID-19 in Bazil: description and epidemiological analysis by state. Cad Saude Publica. 2020;36(9):e00185020. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311X00185020 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6..Gaythorpe K, Abbas K, Huber J, Karachaliou A, Thakkar N, Woodruff K, et al. Health impact of routine immunisation service disruptions and mass vaccination campaign suspensions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic: multimodel comparative analysis of disruption scenarios for measles, meningococcal A, and yellow fever vaccination in 10 low- and lower middle-income countries. medRxiv [Preprint] 2021 [posted 2021 Jan 26]. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.25.21250489

- 7..Figueiredo PO, Stoffella-Dutra AG, Costa GB, Oliveira JS, Amaral CD, Santos JD, et al. Re-emergence of yellow fever in Brazil during 2016-2019: challenges, lessons learned, and perspectives. Viruses. 2020;12(11):1233. https://doi.org/10.3390/v12111233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8..Gaythorpe KA, Hamlet A, Jean K, Ramos DG, Cibrelus L, Garske T, et al. The global burden of yellow fever. Elife. 2021;10:e64670. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.64670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9..Chen LH, Wilson ME. Yellow fever control: current epidemiology and vaccination strategies. Trop Dis Travel Med Vaccines. 2020;6:1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40794-020-0101-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10..Cavalcante KRLJ, Tauil PL. Epidemiological characteristics of yellow fever in Brazil, 2000-2012. Epidemiol Serv Saude. 2016;25(1):11-20. https://doi.org/10.5123/S1679-49742016000100002136/2019/SVS/MS [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11..Ministério da Saúde (BR), Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde, Departamento de Vigilância das Doenças Transmissíveis. Anexo: Orientações técnico-operacionais para implantação da vacina febre amarela (atenuada), nas áreas sem recomendação de vacinação e atualização das indicações da vacina no Calendário Nacional de Vacinação. Brasília, DF; 2020 [cited 2021 Jun 28]. 17 p. https://sbim.org.br/images/files/ms-sei-implantacao-da-vfa-dose-de-reforco.pdf

- 12..Melo CFCA, Vasconcelos PFC, Alcantara LCJ, Araujo WN. The obscurance of the greatest sylvatic yellow fever epidemic and the cooperation of the Pan American Health Organization during the COVID-19 pandemic. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2020;53:e20200787. https://doi.org/10.1590/0037-8682-0787-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13..Ministério da Saúde (BR), Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde, Coordenação Geral de Vigilância das Arboviroses. Situação epidemiológica da febre amarela no monitoramento 2019/2020. Bol Epidemiol. 2020 [cited 2021 Jun 28];51(1):1-19. Available from: https://www.rets.epsjv.fiocruz.br/sites/default/files/arquivos/biblioteca/boletim-epidemiologico-svs-01.pdf

- 14..Kraemer MUG, Faria NR, Reiner RC Jr, Golding N, Nikolay B, Stasse S, et al. Spread of yellow fever virus outbreak in Angola and the Democratic Republic of the Congo 2015-16: a modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17(3):330-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30513-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15..Yismaw AE, Assimamaw NT, Bayu NH, Mekonen SS. Incomplete childhood vaccination and associated factors among children aged 12-23 months in Gondar city administration, Northwest, Ethiopia 2018. BMC Res Notes. 2019;12(1):241. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-019-4276-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16..Arroyo LH, Ramos ACV, Yamamura M, Weiller TH, Crispim JA, Cartagena-Ramos D, et al. [Areas with declining vaccination coverage for BCG, poliomyelitis, and MMR in Brazil (2006-2016): maps of regional heterogeneity]. Cad Saude Publica. 2020;36(4):e00015619. Portuguese. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311X00015619 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17..Césare N, Mota TF, Lopes FFL, Lima ACM, Luzardo R, Quintanilha LF, et al. Longitudinal profiling of the vaccination coverage in Brazil reveals a recent change in the patterns hallmarked by differential reduction across regions. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;98:275-80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.06.092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18..Vieira EW, Pimenta AM, Montenegro LC, Silva TMR. Structure and location of vaccination services influence the availability of the triple viral in Brazil. REME Rev Min Enferm. 2020;24:e1325. https://doi.org/10.5935/1415-2762.20200062

- 19..Pacheco FC, França GVA, Elidio GA, Domingues CMAS, Oliveira C, Guilhem DB. Trends and spatial distribution of MMR vaccine coverage in Brazil during 2007–2017. Vaccine. 2019;37(20):2651-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.04.019 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20..Mantel C, Cherian T. New immunization strategies: adapting to global challenges. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2020;63(1):25-31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00103-019-03066-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21..Antunes JLF, Cardoso MRA. Using time series analysis in epidemiological studies. Epidemiol Serv Saude. 2015;24(3):565-76. https://doi.org/10.5123/S1679-49742015000300024

- 22..Chen Y. Spatial autocorrelation approaches to testing residuals from least squares regression. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0146865. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0146865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23..Ministério da Saúde (BR), Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Informe quinzenal sarampo – Brasil, semanas epidemiológicas 43 de 2020 a 1 de 2021. Bol Epidemiol. 2021 [cited 2021 Jun 28];52(4):1-24. Available from: https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/media/pdf/2021/fevereiro/11/boletim_epidemiologico_svs_4.pdf

- 24..Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Sinopse do Censo Demográfico 2010. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE; 2010 [cited 2021 Aug 1]. Available from: https://censo2010.ibge.gov.br/sinopse/index.php

- 25..Silva FS, Barbosa YC, Batalha MA, Ribeiro MRC, Simões VMF, Branco MRFC, et al. Incompletude vacinal infantil de vacinas novas e antigas e fatores associados: coorte de nascimento BRISA, São Luís, Maranhão, Nordeste do Brasil. Cad Saude Publica. 2018;34(3):e00041717. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311X00041717 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26..Kerr L, Kendall C, Silva AAM, Aquino EML, Pescarini JM, Almeida RLF, et al. COVID-19 in Northeast Brazil: achievements and limitations in the responses of the state governments. Cienc Saude Colet. 2020;25 Suppl 2:4099-120. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-812320202510.2.28642020 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27..Noronha KVMS, Guedes GR, Turra CM, Andrade MV, Botega L, Nogueira D, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil: analysis of supply and demand of hospital and ICU beds and mechanical ventilators under different scenarios. Cad Saude Publica. 2020;36(6):e00115320. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311X00115320 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28..Lemos DRQ, D’Angelo SM, Farias LABG, Almeida MM, Gomes RG, Pinto GP, et al. Health system collapse 45 days after the detection of COVID-19 in Ceará, Northeast Brazil: a preliminary analysis. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2020;53:e20200354. https://doi.org/10.1590/0037-8682-0354-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29..Ritchie A, Esteban Ortiz-Ospina, Diana Beltekian, Edouard Mathieu. Coronavirus (COVID-19) vaccinations. Our World in Data. 2021 [cited 2021 Mar 29]. Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations

- 30..Medina MG, Giovanella L, Bousquat A, Mendonça MHM, Aquino R. Primary healthcare in times of COVID-19: what to do? Cad Saude Publica. 2020;36(8):e00149720. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311x00149720 [DOI] [PubMed]