Abstract

This study aimed to analyze prehospital Emergency Medical Services (EMS) response to the COVID-19 pandemic in the US through a brief systematic review of available literature in context with international prehospital counterparts. An exploration of the NCBI repository was performed using a search string of relevant keywords which returned n=5128 results; articles that met the inclusion criteria (n=77) were reviewed and analyzed in accordance with PRISMA and PROSPERO recommendations. Methodical quality was assessed using critical appraisal tools, and the Egger’s test was used for risk of bias reduction upon linear regression analysis of a funnel plot. Sources of heterogeneity as defined by P < 0.10 or I^2 > 50% were interrogated. Findings were considered within ten domains: structural/systemic; clinical outcomes; clinical assessment; treatment; special populations; dispatch/activation; education; mental health; perspectives/experiences; and transport. Findings suggest, EMS clinicians have likely made significant and unmeasured contributions to care during the pandemic via nontraditional roles, ie, COVID-19 testing and vaccine deployment. EMS plays a critical role in counteracting the COVID-19 pandemic in addition to the worsening opioid epidemic, both of which disproportionately impact patients of color. As such, being uniquely influential on clinical outcomes, these providers may benefit from standardized education on care and access disparities such as racial identity. Access to distance learning continuing education opportunities may increase rates of provider recertification. Additionally, there is a high prevalence of vaccine hesitancy among surveyed nationally registered EMS providers. Continued rigorous investigation on the impact of COVID-19 on EMS systems and personnel is warranted to ensure informed preparation for future pandemic and infectious disease responses.

Keywords: EMS, COVID-19, prehospital, pandemic response, EMT, paramedic

Introduction

Prehospital clinical care under the purview of Emergency Medical Services (EMS) has been traditionally understudied in the United States, as illustrated by the scarcity of literature as compared to other allied health professions. Under the federal oversight of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), EMS models of care vary drastically, shaped largely by geographic assignment, local community partners, and additional presiding authorities. Common models include municipality-based, private nonprofit, and private for-profit services.1

Within these structural differences exist a subset variance of agencies’ scope of practice. In accordance with the National EMS Scope of Practice Model, the Basic Life Support (BLS) scope extends to Emergency Medical Responders (EMRs) and Emergency Medical Technicians (EMTs), while the Advanced Life Support (ALS) scope is characteristic of Advanced EMTs (AEMTs) and Paramedics (EMT-Ps).2 As of January 2022, COVID-19, the respiratory infection caused by novel SARS-CoV-2, is a leading cause of death in the US.3 This global pandemic has established an unprecedented call for rigorous investigation of resource capacity and competency amid allied health care industries to ascertain structural deficits and strengths that have implications for future pandemic response. Further, preliminary mixed-method studies on EMS pandemic response in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic have identified deficits in the domains of resource availability, continued education, administrative protocols, and decontamination practices.4

Although evidently there is an apparent scarcity of academic literature centering US EMS systems in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, it may be useful to summatively review existing literature of satisfactory methodical quality to highlight research areas that warrant further investigatory attention, as no review of this scope and nature currently exists. In this study, we aimed to systematically review peer-reviewed literature indexed in PubMed pertaining to COVID-19 considerations, effects, and implications on US EMS systems and clinicians within the context of prehospital international counterparts by employing artificial intelligence and conventional PRISMA and PROSPERO recommendations.

Methods

Search Strategy

On 07 March 2022 a PubMed National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) repository search was conducted using the keywords “COVID,” “COVID-19,” “SARS-COV-2,” “CORONAVIRUS,” “EMERGENCY MEDICAL SERVICES,” “EMS”, “EMT”, “PREHOSPITAL,” “OUT OF HOSPITAL,” and “PARAMEDIC.” The returned English results were uploaded to Rayyan.ai for comprehensive abstract and full text review.5

Data Extraction

Duplicate results were assessed for and removed. Editorials, commentaries, and non-peer reviewed manuscripts were excluded. Two investigators independently reviewed abstracts to identify articles eligible for full text review. The investigators then independently reviewed full text articles to identify studies that met the PICOS-guided inclusion criteria.6 Studies were excluded if there were concerns regarding methodical quality or integrity of the data as per discretion of the two investigators and a third consultant. SIGN appraisal tools were used to exclude retrospective and cohort-based studies that did not meet an acceptable level of evidence for inclusion in the review.7 Conflicts were resolved through discussion and by mediation from a third or fourth consultant when necessary. Study methods were consistent with PRISMA recommendations, and although PROSPERO registration was not sought, the work remained faithful to conventional review standards.8,9

Analysis

Stata/BE software was used to assess aggregate prevalence of data. Heterogeneity was defined as P < 0.10 or I^2 > 50% which warranted a fixed effects approach.10 Otherwise, a random effects approach was assumed. We then sought to investigate sources of heterogeneity. During full text review, studies were primarily taxonomized in one of the following ten domains: i. structural/systemic, ii. clinical outcomes, iii. clinical assessment, iv. treatment, v. special populations, vi. dispatch/activation, vii. education, viii. mental health, ix. perspectives/experiences, x. transport.

Methodical Quality

Investigators determined risk of bias for prevalence studies based upon appropriateness of sampling, sampling methods, use of standard assessment methods, and setting characteristics. The criteria were adapted from either the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist for Studies Reporting Prevalence Data or the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Tool for Quasi-Experimental Studies.11,12 A 95% confidence interval was used to standardize prevalence and pooling of data, and the linear regression based Egger’s test was used to analyze the presence of any publication bias after a funnel plot was created and assessed.13 P > 0.05 deemed no risk of publication bias. Microsoft Excel was used to calculate standard deviation and mean. Sensitivity analyses assessed for source of heterogeneity and stability of results. Because the work did not involve the use of human research subjects, it did not require approval or review by an institutional review board or bioethics committee.

Diversity in the Research Team

The work represents a cross-institutional and multi-disciplinary collaboration amongst public health oriented researchers, EMS clinicians, and physician scientists.

Results

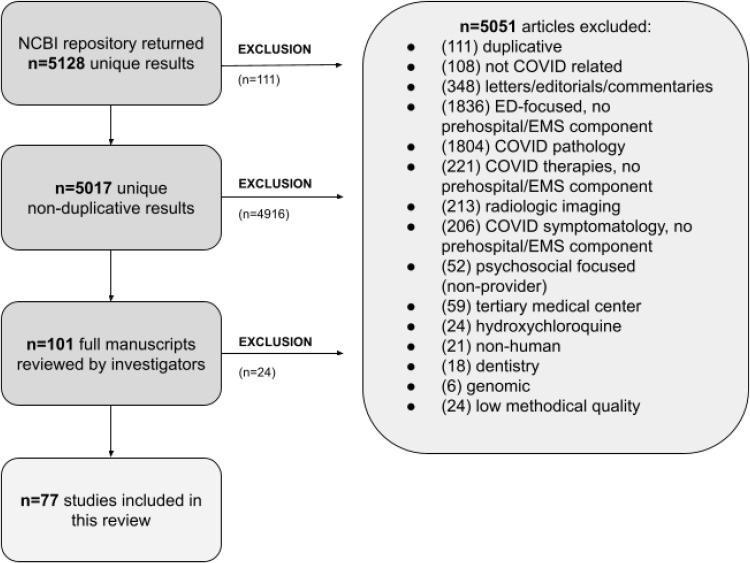

The NCBI repository returned n=5128 results, with n=77 utilized for analysis and inclusion in this study. Results were excluded if they did not satisfy the inclusion criteria. Figure 1 depicts an overview of the exclusion schema. AI identified n=111 duplicative results, n=4916 results were excluded due to irrelevance with respect to the area of investigation, and n=24 studies were excluded after investigators performed full text reviews and found studies to be of unsatisfactory evidence levels in accordance with SIGN appraisal guidelines. Table 1 depicts characteristics of studies selected for inclusion, with high confidence in stability and quality of the aggregate data.

Figure 1.

Schematic selection of relevant articles for inclusion in review.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Studies Selected for Inclusion

| # | Author(s) | Title | Design | Sample | Country/Region | Summary of Key Findings | Primary Domain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Slavova et. al14 | Signal of increased opioid overdose during COVID-19 from emergency medical services data | Cohort | Incidences of opioid overdose | Kentucky, US | ● Post-COVID emergency declaration, daily opioid overdose runs increased. ● EMS conditions for other chief complaints remained static or declined. ● 50% increase in suspected opioid overdose death calls. |

Clinical Outcomes |

| 2 | Tien et. al15 | Critical care transport in the time of COVID-19 | Case | Performance of region-based medical transport service | Ontario, CA | ● Ornge, a critical care transport service, has transported 325 patients either confirmed or suspected to have COVID-19. ● This was divided into three types of transport: critical care land ambulances (52.3%), PC-12 Next Generation fixed wing aircraft (28.9%), and AW-139 rotary wing aircraft (16.6%). ● No staff members tested positive for COVID-19 during this period. ● Though not typical for critical care transport, Ornge has also transported 450 COVID-19 test samples. |

Transport |

| 3 | Dahmen et. al16 | COVID-19 Stress test for ensuring emergency healthcare: strategy and response of emergency medical services in Berlin | Case | Emergency calls by region-based medical transport service | Berlin, DE | ● Increase in visits to patients with acute respiratory diseases. ● 11% of all visits were to patients suspected of having COVID-19. ● The average call time increased by 1 minute and 36 seconds due to extended screening processes. ● The average visit time increased by 17 minutes when patients experienced acute respiratory problems. |

Structural/ Systemic |

| 4 | Levy et. al17 | Correlation between Emergency Medical Services Suspected COVID-19 Patients and Daily Hospitalizations | Retrospective, correlational | Statewide EMS electronic medical records | Maryland, US | ● 26,855 patients out of 225,355 emergency calls were considered to be suspected COVID-19 cases. ● 91.2% of these patients were moved to hospitals and 25.6% had abnormal initial pulse oximetry. ● Cross correlation was found between transports and daily hospitalizations, with a 9-day lag in hospitalization rate (p < 0.01). |

Clinical Outcomes |

| 5 | Şan et. al18 | Effects of COVID-19 Pandemic on Emergency Medical Services | Retrospective, correlational | Provincial EMS electronic medical records | Ankara, TR | ● 90.9% increase in calls during the COVID-19 pandemic. ● Of these, 15.2% were suspected to have COVID-19 and 2.9% were eventually diagnosed. ● Frequency of cases for children 0–18 decreased, while 18+ saw an increase. ● Symptoms of fever and cough increased by 14.1% and 956.3%, respectively. ● Other cases such as myocardial infarction or cerebrovascular disease decreased in frequency. |

Structural/ Systemic |

| 6 | Handberry et. al19 | Changes in Emergency Medical Services Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic in the United States, January 2018-December 2020 | Longitudinal | Nationwide 911 activations from NEMSIS data | US | ● Decrease in overall volume of EMS cases during the early pandemic. ● However, there was an increase in on-scene death (1.3% to 2.4%), cardiac arrest (1.3% to 2.2%), and opioid use or overdose (0.6% to 1.1%) during the early height of the pandemic. |

Structural/ Systemic |

| 7 | Roto-Cámara et. al20 | Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Out-of-Hospital Health Professionals: A Living Systematic Review | Systematic Review | Peer-reviewed literature | Global | ● 6.8% of participants examined experience post traumatic stress, between 15–20% experience anxiety, and around 15% have a history of depression. ● Female out-of-hospital health professionals, and those who worked closely with COVID-19 patients were more likely to have stress or anxiety during this time. ● Health professionals with history of illnesses that could make them more susceptible to infection were more likely to have depressive symptoms. |

Mental Health |

| 8 | Al Amiry, Maguire21 | Emergency Medical Services (EMS) Calls During COVID-19: Early Lessons Learned for Systems Planning (A Narrative Review) | Narrative Review | Peer-reviewed literature | Global | ● Call volume and response time dramatically increased, most notably Israel with a 1900% increase in calls and India with an up to 12 hour response time. ● Length of call time increased, eg from 8 minutes to 1 hour in Italy. ● Fewer calls were made for cases of stroke and cardiac arrest, which lead to collateral mortality (eg 300% increase in mortality in Italy one month post- pandemic). |

Dispatch/ Activation |

| 9 | Satty et. al22 | EMS responses and non-transports during the COVID-19 pandemic | Case Control | 911 call responses by 22 regiospecific EMS agencies | Pennsylvania, US | ● 26.5% decrease in EMS response in 2020, compared to responses per year from 2016–2019. ● Slight increase in respiratory illnesses and patients’ abnormal vital signs. ● 48% increase in non-transports in April 2020 compared to April 2019. |

Transport |

| 10 | Grawey et. al23 | ED EMS time: A COVID-friendly alternative to ambulance ride-alongs | Qualitative | Medical students | Wisconsin, US | ● ED-EMS time is an effective alternative to EMS ride time. ● Medical students report increased understanding of EMS capabilities and prehospital considerations. ● Method limits patient contact, maintains PPE, and limits COVID-19 exposure. |

Education |

| 11 | Fernandez et. al24 | COVID-19 Preliminary Case Series: Characteristics of EMS Encounters with Linked Hospital Diagnoses | Cohort | National EMS electronic medical records | US | ● EMS COVID-19 Suspicion was present in 78% of hospital diagnosed COVID-19 patients. ● EMS COVID-19 Suspicion had a 20% positive predictive value compared to hospital codes. ● EMS PPE use was documented at higher rates on records that has a hospital COVID-19 diagnosis. |

Clinical Outcomes |

| 12 | Gregory et. al25 | COVID-19 Vaccinations in EMS Professionals: Prevalence and Predictors | Cross Sectional | National Survey of EMS Professionals | US | ● 70% of EMS professionals are vaccinated in the US. ● The majority of those who did not receive the vaccine reported concerns of safety as well as feeling it was not necessary. ● 84% of those who had not yet received the vaccine do not plan to receive it in the future. |

Perspectives/ Experiences |

| 13 | Ardebili et. al26 | Healthcare providers experience of working during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study | Qualitative | Medical Professionals of 3 major cities | IR | ● 4 major themes present in interviews included: ‘Working in the pandemic era’, ‘Changes in personal life and enhanced negative affect’, ‘Gaining experience, normalization and adaptation to the pandemic’ and ‘Mental Health Considerations’. |

Perspectives/ Experiences |

| 14 | Jaffe et. al27 | Responses of a Pre-hospital Emergency Medical Service During Military Conflict Versus COVID-19: A Retrospective Comparative Cohort Study | Cohort | Emergency Ambulance Calls to A National EMS Organization | IL | ● During conflict call amounts decreased with an increase in calls post-conflit compared to pre- conflict. ● During COVID lockdown call amounts increased with a decrease in calls post-conflit compared to pre- conflict. ● There was a significant decrease in MVC and other injuries only during the lockdown. |

Structural/ Systemic |

| 15 | Vanhaecht et. al28 | COVID-19 is having a destructive impact on health-care workers’ mental well-being | Cross Sectional | Survey of Healthcare workers in a cit. | Flanders, BE | ● Negative psychological symptoms increased during the pandemic and Positive symptoms were experienced less frequently. ● 18% of healthcare workers felt there was a need for psychological guidance and 27% wanted more leadership support. ● Strongest correlation between COVID-19 and psychological symptoms was in 30–49 years, females, nurses and residential care centers. |

Mental Health |

| 16 | Jensen et. al29 | Strategies to Handle Increased Demand in the COVID-19 Crisis: A Coronavirus EMS Support Track and a Web-Based Self-Triage System | Cross Sectional | City EMS Agency Call Records | Copenhagen, DK | ● Total EMS call volume increased by 23.3% between 2019 and 2020. ● 4.4% increase was seen in the 112 emergency line and a 25.1% increase in the 1813 medical helpline. ● The wait time of the medical helpline increased from 2m:23s to 12m:2s from 2019 to 2020. ● There appears to be no correlation between call volume and web triage system usage. |

Structural/ Systemic |

| 17 | Firew et. al30 | Protecting the front line: a cross-sectional survey analysis of the occupational factors contributing to healthcare workers’ infection and psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic in the USA | Cross Sectional | National survey of healthcare workers | US | ● 29% of respondents could be considered a probable case from symptoms or test results. ● Healthcare workers with COVID-19 appear to have higher levels of depressive symptoms. ● Emergency Department workers have the highest likelihood of contracting COVID-19. |

Mental Health |

| 18 | Jouffroy et. al31 | Hypoxemia Index Associated with Prehospital Intubation in COVID-19 Patients | Case Control | Clinical care reports of COVID-19 patients cared for by regional ALS prehospital service | Paris, FR | ● A hypoxemia index (HI) < 1.3 correlated with a 3 fold increase in prehospital endotracheal intubation of patients with COVID-19. ● Hypoxemia index may be a reliable indicator for prehospital endotracheal intubation in respiratorily compromised patients with COVID-19. |

Clinical Outcomes |

| 19 | Ventura et. al4 | Emergency Medical Services resource capacity and competency amid COVID-19 in the United States: preliminary findings from a national survey | Cohort | Survey of Practicing US EMS clinicians | US | ● There is a lack of knowledge among EMS providers on the risk and transmission of COVID 19. ● There is a lack of equipment and PPE available to EMS providers. ● EMS agencies are often not providing training or resources to employees in regard to COVID-19. |

Structural/ Systemic |

| 20 | Tabah et. al32 | Personal protective equipment and intensive care unit healthcare worker safety in the COVID-19 era (PPE-SAFE): An international survey | Cross Sectional | Survey International Healthcare Workers | Global | ● 52% of Healthcare workers reported missing at least one piece of PPE. ● 30% report having to reuse single-use PPE. ● Significant adverse effects from long PPE use was reported. |

Structural/ Systemic |

| 21 | Prezant et. al33 | System impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on New York City’s emergency medical services | Longitudinal | City EMS Agency Call Records | New York City, US | ● On March 30, 2020 call volumes increased 60% compared to the same dates in 2019. ● The proportion of high acuity calls increased 42.3% in 2020 from 36.4% in 2019. ● High acuity call response time had an increase in 3min compared to low acuity calls which had an increase of 11min. ● The most common call types were respiratory and cardiovascular related. |

Structural/ Systemic |

| 22 | Berry et. al34 | Helicopter Emergency Medical Services Transport of COVID-19 Patients in the “First Wave”: A National Survey | Cross Sectional | National Survey of Helicopter EMS services | US | ● 85% of programs reported that they chose to transport known or suspected COVID-19 patients. ● 93% reported providing COVID-19 training to its providers. ● PAPR or N95 protective equipment was provided in Covid-19 suspected cases by 77% of programs and 95% included pilots in distribution. |

Transport |

| 23 | Xie et. al35 | Predicting Covid-19 emergency medical service incidents from daily hospitalization trends | Case | Documented EMS incidents within a specific region | Texas, US | ● On March 17th, the daily number of non-pandemic EMS incidents dropped significantly. ● On May 13th, the daily number of EMS calls climbed back to 75% of the number in pre-Covid-19 time. ● For every 2.5 cases where EMS takes a Covid-19 patient to a hospital, one person is admitted. ● The mean daily number of non-pandemic EMS demand was significantly less than the period before Covid-19 pandemic. |

Clinical Outcomes |

| 24 | Gonzalez et. al36 | Proctologic emergency consultation during COVID-19: Comparative cross-sectional cohort study | Cross Sectional | Retrospective review of patient data | ES | ● 191 patients were reviewed from 2019–2020. ● There was a 56% decrease in protocologic emergency consultation, but the need for surgery was 2x more frequent. ● There was no difference in outpatients regimen after emergency surgery. |

Clinical Assessment |

| 25 | Greenhalgh et. al37 | Where did all the trauma go? A rapid review of the demands on orthopaedic services at a UK Major Trauma Centre during the COVID-19 pandemic | Cohort | Database of Trauma Patients at a Regional Trauma Center | UK | ● There was a 50.7% decrease in the number of referrals to the orthopedic team. ● There was a 43.2% decrease in the number of trauma operations carried out at the MTC trust. ● There was a 53.6% decrease in the number of pediatric referrals. ● There was a 35.4% decrease in the number of major trauma patients. ● Covid-19 had a big effect of the provision of trauma and orthopedic surgery. |

Clinical Outcomes |

| 26 | Bourn et. al38 | Initial prehospital Rapid Emergency Medicine Score (REMS) to predict outcomes for COVID-19 patients | Cohort | Prehospital and hospital records from ESO Data Collaborative | Texas, US | ● Initial prehospital Rapid Emergency Response Score was modestly predictive of ED and hospital dispositions for pts with Covid-19. ● Prediction was stronger for outcomes closer to the first set of EMS vital signs. ● In 13,890 Covid-19 pts, the median Rapid Emergency Response Score was 6. |

Clinical Outcomes |

| 27 | Nishikimi et. al39 | Intubated COVID-19 predictive (ICOP) score for early mortality after intubation in patients with COVID-19 | Cohort | Hospital medical records of Intubated patients with COVID-19 | New York City, US | ● The predictors of death within 14 days after intubation included old age, hx of chronic kidney disease, lower mean arterial pressure or increased dose of required vasopressors, higher urea nitrogen level, higher ferritin, higher oxygen index, and abnormal pH levels. |

Clinical Outcomes |

| 28 | Feng et. al40 | Impact of COVID-19 on emergency patients in the resuscitation room: A cross-sectional study | Cross Sectional | Emergency room patients in 2019 and 2020 | Nanning, CN | ● There was a decrease in the number of emergency patients in the resuscitation room during the Covid- 19 Pandemic in intrinsic/extrinsic diseases and pediatric cases. ● There was a decrease in the length of stay of emergency patients in the resuscitation room. ● Comparison made between 2020 and 2019 in Nanning, China. |

Clinical Outcomes |

| 29 | Garcia-Castrillo et. al41 | European Society For Emergency Medicine position paper on emergency medical systems’ response to COVID-19 | Review | Literature of current and previous pandemic recommendations | EU | ● Current literature states that only critical patients with COVID-19 should be admitted to the emergency department. ● It is suggested that pre-hospital personnel be used to perform initial assessment on COVID-19 patients and possible contacts and if transportation or home isolation is indicated. ● It is also stated that an additional consultation line should not be used for noncritical cases instead of the emergency line. |

Structural/ Systemic |

| 30 | Albrecht et. al42 | Transport of COVID-19 and other highly contagious patients by helicopter and fixed-wing air ambulance: a narrative review and experience of the Swiss air rescue | Review | Air Ambulance Crew Narratives | CH | ● Lots of different means are being used for the aeromedical transport of infectious pts. ● A method of transporting infectious pts are either isolating/pt. ● Small Patient Isolation Units are beneficial, ex: transport can easily be changed without contamination and still allowing access to pt. |

Transport |

| 31 | US Centers for Disease Control & Prevention43 | Interim Guidance for Emergency Medical Services (EMS) Systems and 911 Public Safety Answering Points (PSAPs) for COVID-19 in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention | N/A | N/A | US | ● Face masks are used as an alternative to respirators when the supply chain is low. ● Eye protection, gowns, and gloves should continue to be worn. ● Recommended EPA-registered disinfectants are on a reference list on the EPA website. |

Structural/ Systemic |

| 32 | Yang et. al44 | Clinical Characteristics of Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Receiving Emergency Medical Services in King County, Washington | Cohort | COVID-19 patient records of a country EMS service | Washington, US | ● Most patients with Covid-19 who went to emergency services were older and had multiple chronic health conditions. ● Saying that Covid-19 is a febrile respiratory illness does not necessarily fit for early diagnostic suspicion, at least for prehospital settings. ● As of June 1, 2020, mortality among the study cohort was 52.4%. |

Clinical Assessment |

| 33 | Murphy et. al45 | Occupational exposures and programmatic response to COVID-19 pandemic: an emergency medical services experience | Cohort | Mixed | Washington, US | ● Of 700 EMS clinicians 0.4% tested positive during the duration of the investigation. ● Less than 0.5% experienced COVID related illness within 14 days of exposure. |

Perspectives/ Experiences |

| 34 | Spangler et. al46 | Prehospital identification of Covid-19: an observational study | Observational | Patient care reports | Uppsala, SE | ● Patients who tested positive for Covid-19 had worse outcomes than those who tested negative. ● 30 day mortality rates were 24% vs 11% in Covid-19 positive vs negative. ● Suspicion of Covid-19 in a prehospital setting should not be solely relied on to rule out using isolation precautions. |

Clinical Assessment |

| 35 | Albright et. al47 | A Dispatch Screening Tool to Identify Patients at High Risk for COVID-19 in the Prehospital Setting | Case Control | Prehospital care reports and electronic health charts | Massachusetts, US | ● In MA, the rate of positive Covid-19 tests was 2%. ● Reporting shortness of breath was the most common symptom that resulted in a positive screening for Covid-19. ● Most positive tests did not belong to high-risk populations. |

Dispatch/ Activation |

| 36 | Cash et. al48 | Emergency Medical Services Personnel Awareness and Training about Personal Protective Equipment during the COVID-19 Pandemic | Cross-sectional | Mixed | US | ● Despite increased CDC guidance for N95 fit testing for EMS, there are still substantial gaps in PPE training use among EMS. ● Part-time workers, 911 response service, working at non-fire based EMS services, and working in rural areas are associated with lower odds of awareness/ training. |

Perspectives/ Experiences |

| 37 | Moeller et. al49 | Symptom presentation of SARS-CoV-2-positive and negative patients: a nested case-control study among patients calling the emergency medical service and medical helpline | Case | Clinical data from patient care reports | Copenhagen, DK | ● Loss of smell/taste as a symptom of Covid-19 was almost always reported for patients younger than 60. ● Fever and cough were the most common symptoms in all age groups. ● Loss of appetite and feeling unwell were symptoms that were more common for patients over 60 years old. |

Clinical Assessment |

| 38 | Jouffroy et. al50 | Prehospital management of acute respiratory distress in suspected COVID-19 patients | Cohort | EMS and Hospital Patient Care Records | Paris, FR | ● 15% of 256 patients with COVID-19 symptoms died at the scene but there was a low prevalence of prior cardiovascular risk factors. ● Out of the 185 patients analyzed 44% were transported via BLS and 42% received non- invasive ventilation. ● 56% were transported via ALS and 52% of these patients received noninvasive ventilation and 18% received intubation. |

Treatment |

| 39 | Shekhar et. al51 | COVID-19 and the Prehospital Incidence of Acute Cardiovascular Events (from the Nationwide US EMS) | Mixedl | Mixed | US | ● 10.33% decrease in EMS calls between January and March 2020. ● 4.62% decrease from February to March 2020. ● STEMI and CVA alerts decreased across all months. ● Incidence of VF/VT and asystole decreased from January to March, but increased from March to April. |

Clinical Outcomes |

| 40 | Glenn et. al52 | Refusals After Prehospital Administration of Naloxone during the COVID-19 Pandemic | Cohort | Incidences of refusals following naloxone administration | US | ● The amount of patients that refused transport following prehospital administration of naloxone increased during the pandemic. ● During the COVID-19 pandemic, over twice as many patients who received naloxone in a prehospital setting refused transport than prior to the pandemic. ● 29.7% of patients who did not receive naloxone refused transport prior to the pandemic, while 41.3% refused during the pandemic. |

Clinical Outcomes |

| 41 | Jarvis et. al53 | Examining emergency medical services’ prehospital transport times for trauma patients during COVID-19 | Cohort | Trauma patients transported via EMS to six US trauma centers | US | ● There was no significant difference in total EMS prehospital times between 2019 and during COVID- 19 pandemic. ● Times during transport were less during the pandemic than in 2019. ● Less trauma patients were transported during the pandemic than in 2019. |

Transport |

| 42 | March et. al54 | Effects of COVID-19 on EMS Refresher Course Completion and Delivery | Case | Commission Accreditation for Prehospital Continuing Education database of continuing education records | US | ● There was a 179% increase in completion of EMS refresher courses from 2018 to 2020. ● There was a 185% increase in asynchronous online refresher course completion from 2018 to 2020. ● No significant difference in mean monthly live in person and virtual instructor-led training in the months between 2018 and 2020. ● Study suggests EMS refresher course completions are more likely when given via asynchronous methods rather than live in person methods as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. |

Education |

| 43 | Saberian et. al55 | How the COVID-19 Epidemic Affected Prehospital Emergency Medical Services in Tehran, Iran | Case Control | Records of EMS activations, employees, and time codes | Tehran, UQ | ● Tehran prehospital personnel experienced a 347% increase in EMS calls and 21% increase in EMS dispatches. ● After the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, Tehran EMS saw an increase in chief complaints of fever by 211% and respiratory distress by 245%. ● To keep up with the increased EMS demand, Tehran increased the amount of EMS providers available, decreased time between shifts, and raised amount of overtime hours. ● In-service education continued during the pandemic. |

Structural /Systemic |

| 44 | Oulasvirta et. al56 | Paediatric prehospital emergencies and restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic: a population-based study | Cohort | EMS contacts involving children between 0 and 15 years old | Helsinki, FL | ● There was a decrease in pediatric EMS calls by 30.4% from March 2020 to May 2020. ● After the onset of the pandemic, a majority of pediatric EMS contacts were a result of trauma or a need for intensive care. ● There was a decrease in number of transports of pediatric patients following contact with EMS personnel after onset of the pandemic. ● Pediatric patients that made contact with EMS were more likely to be critically ill between March 2020 and May 2020 than prior to this period. |

Special Populations |

| 45 | Hadley et. al57 | 911 EMS Activations by Pregnant Patients in Maryland (USA) during the COVID-19 Pandemic | Retrospective | Records of EMS calls related to obstetric emergencies | Maryland, US | ● There was a decrease in EMS calls in response to obstetric issues during the pandemic than was seen in the months prior. ● High fraction (as compared to population demographics) of obstetric-related EMS calls were from African-American women during the pandemic. ● Percent of EMS contacts with female patients remained unchanged in the periods during and prior to the pandemic. |

Special Populations |

| 46 | Hart et. al58 | Recommendations for Prehospital Airway Management in Patients with Suspected COVID-19 Infection | Systematic Review | Peer-reviewed literature | US | ● Providers should always don and secure Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) prior to making contact with a patient suspected of having COVID-19. ● EMS should not try endotracheal intubation more than once, as to prevent additional exposure to infection, and should attempt with video laryngoscopy rather than direct laryngoscopy if possible. ● After ET or SGA placement, HEPA filter should be placed on ET tube or SGA to prevent potential COVID-19 exposure to other equipment. ● For BLS crews who are unauthorized to perform intubation or SGA placement techniques, it is recommended to perform two-person resuscitation techniques to ensure a tight seal of BVM on patient’s mouth to prevent contamination. |

Treatment |

| 47 | Mohammadi et. al59 | Management of COVID-19-related challenges faced by EMS personnel: a qualitative study | Qualitative | Detailed interviews with pre-hospital emergency care personnel | IR | ● EMS providers are unsure how to approach patients suspected of COVID-19 infection due to a lack of standard, comprehensive treatment protocols. ● EMS personnel experience psychological strain as a result of inadequate equipment and increased work hours during the COVID-19 pandemic. ● EMS personnel are frustrated with the lack of public education of COVID-19 which leaves many patients unable to take proper precautions to prevent exposing providers to infection. |

Perspectives/ Experiences |

| 48 | Lancet et. al60 | Prehospital hypoxemia, measured by pulse oximetry, predicts hospital outcomes during the New York City COVID-19 pandemic | Longitudinal | Adult patients transported by EMS in NYC | New York, US | ● Prehospital oxygen saturation level is an indicator of mortality and length of stay in hospital. ● In patients over 65 years old, an oxygen saturation above 90% showed a 26% chance of death in hospital, while a saturation below 90% showed a 54% chance of death. ● In patients under 66, a prehospital oxygen saturation above 90% revealed 11.5% chance of death, while oxygen saturation under 90% revealed a 31% chance of death in hospital. |

Clinical Outcomes |

| 49 | Powell et. al61 | Prehospital Sinus Node Dysfunction and Asystole in a Previously Healthy Patient with COVID-19 | Case | Female with nodal dysfunction and asystole following COVID-19 infection | US | ● A 47 year old patient with no history of prior illness experienced nodal dysfunction and asystole episodes, characterized by hypoxia due to pneumonia. ● Post-recovery, no other arrhythmias were observed. |

Clinical Assessment |

| 50 | Velasco et. al62 | Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on the Incidence, Prehospital Evaluation, and Presentation of Ischemic Stroke at a Nonurban Comprehensive Stroke Center | Retrospective | Patients presenting with ischemic stroke symptoms as obtained by prehospital quality improvement database | US | ● There was a decrease in the number of transports of patients experiencing stroke symptoms from 2019 to 2020. ● The median amount of transport time between EMS dispatch and hospital arrival for patients diagnosed with a stroke increased from 2019 to 2020. ● There is a decrease in patient transport volumes and increase in time taken to access appropriate care from 2019 to 2020 in nonurban areas. |

Clinical Outcomes |

| 51 | Solà-Muñoz et. al63 | Impact on polytrauma patient prehospital care during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study | Cross Sectional | Records of EMS activations as a result of polytrauma patients | Catalonia, ES | ● There was a 52% decrease in polytraumatic patients treated after the onset of the pandemic. ● There was a decrease in EMS dispatches to traffic accidents and pedestrian-vehicle collisions from before the pandemic to the first few months of the pandemic. ● There was an increase in injuries caused by weapons and burns after the onset of the pandemic. ● The COVID-19 pandemic decreased the amount of polytraumatic patients treated by EMS, and saw a difference in the severity and category of trauma. |

Clinical Outcomes |

| 52 | Siman-Tov et. al64 | An assessment of treatment, transport, and refusal incidence in a National EMS’s routine work during COVID-19 | Comparative | Patient care reports | IL | ● Incidence of infectious disease, cardiac arrest, psychiatric, and labor and delivery calls increased from March and April 2019 to 2020 ● Incidence of neurology and trauma calls decreased in the same period. ● Refusal by patients for transport to a hospital increased from 13.4% to 19.9%, accompanied by an increase in deaths 8 days post-refusal. |

Structural/ Systemic |

| 53 | Marincowitz et. al65 | Prognostic accuracy of triage tools for adults with suspected COVID-19 in a prehospital setting: an observational cohort study | Cohort | Patient care reports | GB | ● 65% of patients were transported to hospital and EMS decision to transfer patients achieved a sensitivity of 0.84. ● NEWS2, PMEWS, PRIEST tool and WHO algorithm identified pts at risk of adverse outcomes with a high sensitivity. ● Using NEWS2, PMEWS, PRIEST tool, and the WHO algorithm can improve sensitivity of EMS triage of patients with suspected COVID-19 infection. |

Clinical Assessment |

| 54 | Ong et. al66 | An international perspective of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation during the COVID-19 pandemic | Comparative | Mixed | Global | ● Studies in Italy, New York City, and France showed a significant increase in out-of-hospital cardiac arrests with the arrival of the pandemic. ● The difficulties that the first responder system faced during Covid-19 were dispatcher overload, increased response times, and adherence to PPE requirements, superimposed on PPE shortages. ● New noninvasive, adjunct tools, warrant consideration with the rise in OCHA during the pandemic. |

Perspectives/ Experiences |

| 55 | Yu et. al67 | Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on emergency medical service response to out-of-hospital cardiac arrests in Taiwan: a retrospective observational study | Observational | Patient care reports | TW | ● There was a longer EMS response time for patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrests during the pandemic. ● The rate of prehospital ROSC was lower in 2020. ● Significantly fewer cases had favorable neurological function in 2020. |

Structural/ Systemic |

| 56 | Azbel et. al68 | Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on trauma-related emergency medical service calls: a retrospective cohort study | Cohort | Patient care reports | FL | ● During lockdown, there was a 12.2% decrease in the number of weekly total EMS calls. ● There was also a 23.3% decrease in the number of weekly trauma related calls ● There was also a 41.8%. decrease in the weekly number of injured patients met by EMS while intoxicated with alcohol. ● After the lockdown, numbers returned to normal pre-lockdown. |

Clinical Outcomes |

| 57 | Seo et. al69 | Pre-Hospital Delay in Patients With Acute Stroke During the Initial Phase of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Outbreak | Cohort | Patient care reports | Seoul, KR | ● In the initial phase after the Covid-19 outbreak, EMS response times for acute strokes were delayed. ● Clinical outcomes of patients with acute stroke deteriorated. ● The ICU admission and mortality rate increased in the early phase of the Covid-19 outbreak. |

Clinical Outcomes |

| 58 | Mälberg et. al70 | Physiological respiratory parameters in pre-hospital patients with suspected COVID-19: A prospective cohort study | Cohort | Clinical data from patient care reports | Uppsala, SE | ● The odds of having COVID-19 increased with higher respiratory rate, lower tidal volume and negative inspiratory pressure. ● Patients taking smaller, faster breaths with less pressure had higher odds of having COVID-19. ● Smaller, faster breaths and higher dead space percentage increased the odds of hospital admission. |

Clinical Assessment |

| 59 | Ng et. al71 | Impact of COVID-19 ‘circuit-breaker’ measures on emergency medical services utilisation and out-of-hospital cardiac arrest outcomes in Singapore | Case control | Patient care reports | SG | ● EMS call volume and total out-of-hospital cardiac arrests remained comparable to past years. ● There was a decline in prehospital ROSC rates, but not statistically lower than pre-COVID periods. ● There is a growing body of literature internationally on the potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on EMS utilization and outcomes. |

Clinical Outcomes |

| 60 | Cash et. al72 | Emergency medical services education research priorities during COVID-19: A modified Delphi study | Case | Mixed | US | ● The top 4 research priorities were prehospital internship access, impact of lack of field and clinical experience, student health and safety, and EMS education program availability and accessibility. |

Education |

| 61 | Borkowska et. al73 | Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest treated by emergency medical service teams during COVID-19 pandemic: A retrospective cohort study | Cohort | Clinical data from patient care reports | PL | ● The average age of patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest was 67.8 years. ● Among resuscitated patients, 73.8% were cardiac etiology. 9.4% of patients had ROSC, 27.2% of patients were admitted to hospital with ongoing chest compression. ● In the case of 63.4% cardiopulmonary resuscitation was ineffective and death was determined. ● The presence of shockable rhythms was associated with better prognosis. |

Clinical Outcomes |

| 62 | Kalani et. al74 | Self-Referred Walk-in (SRW) versus Emergency Medical Services Brought Covid-19 Patients | Cohort | Mixed | Jahrom, IR | ● 27.1% of COVID-19 patients in the ER were brought in by EMS while 72.9% were self referred walk ins. ● Survival rates were lower among patients brought in by EMS. ● Critically ill patients were more likely to utilize EMS therefore EMS usually brought in patients with lower chances of survival. |

Clinical Outcomes |

| 63 | Talikowska et. al75 | No apparent effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on out-of-hospital cardiac arrest incidence and outcome in Western Australia | Case Control | Incidences of OOHCA events | AU | ● There was no significant change in the number of OOHCAs during the 2020 period compared to a period of similar length in 2017. ● There was no significant change in bystander CPR rates between the two periods. ● There was no significant change in survival rates for OOHCAs. |

Clinical Outcomes |

| 64 | Saberian et. al76 | Changes in COVID-19 IgM and IgG antibodies in emergency medical technicians (EMTs) | Correlational | Acquired clinical data | Tehran, IR | ● There were less seropositive participants than seronegative ones. ● 9.5% only tested positive for IgG. ● 1.1% were only positive for IgM. ● 32.4% were positive for both. ● There was a significant. reduction is seropositivity after the second phase. |

Clinical Outcomes |

| 65 | Ageta et. al77 | Delay in Emergency Medical Service Transportation Responsiveness during the COVID-19 Pandemic in a Minimally Affected Region | Case | Patient care reports | Okayama, JP | ● Prehospital time can be divided into three components: response time, on-scene time, and transportation time. ● The duration of response time and on-scene time increased in April 2020 from April 2019 from 32.2 to 33.8 minutes and 8.7 to 9.3 minutes, respectively (p < 0.001). ● However, there was no significant change in duration of transportation. |

Transport |

| 66 | Hunt et. al78 | Novel Negative Pressure Helmet Reduces Aerosolized Particles in a Simulated Prehospital Setting | Experimental | Particle counts | Michigan, US | ● A personal negative pressure helmet (“AerosolVE”) was developed to filter and trap virus particles from the patient. ● The amount of particles trapped inside the helmet were significantly higher than those outside. ● An average of less than one particle was found externally to the filter. |

Prevention |

| 67 | Tanaka et. al79 | Evaluation of the physiological changes in prehospital health-care providers influenced by environmental factors in the summer of 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic | Correlational | Acquired clinical data | JP | ● A positive correlation was found between WGBT, and pulse rate. ● Forehead temperature increased upon entrance to a 33°C environment. ● Hot environments posed a higher risk of heat stroke while wearing PPE. |

Clinical Outcomes |

| 68 | Melgoza et. al80 | Emergency Medical Service Use Among Latinos Aged 50 and Older in California Counties, Except Los Angeles, During the Early COVID-19 Pandemic Period | Cohort | Data from the California Emergency Medical Services Information System (CEMSIS) | California, US | ● Latinos are disproportionately affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, as they make up 32% of the Californian population, but comprised 52% of COVID-19 cases and 64% of COVID-19 deaths. ● Latinos also comprised a larger proportion of respiratory distress calls than Whites, but a statistically significant smaller proportion than Blacks. |

Special Populations |

| 69 | Goldberg et. al81 | Home-based Testing for SARS-CoV-2: Leveraging Prehospital Resources for Vulnerable Populations | Case | Case Study | US | ● An EMS-created COVID-19 home testing program was established. ● From its inception to April 2020, the program had tested 477 homebound patients, with an average of about 15 per day. ● Mass testing locations were also established for up to 900 tests per day. |

Prevention |

| 70 | Saberian et. al82 | The Geographical Distribution of Probable COVID-19 Patients Transferred by Tehran Emergency Medical Services; a Cross Sectional Study | Cross-sectional | Electronic patient care data | Tehran, IR | ● The mean age of patients increased over the three month study period, from 53.2 to 54.5 to 56.0. ● The average incidence rate of COVID-19 was 4.6 per 10,000 people, with municipalities varying greatly in incidence. |

Transport |

| 71 | Tušer et. al83 | Emergency management and internal audit of emergency preparedness of pre-hospital emergency care | Case | Mixed | CZ | ● Documents, communications technology, and processes for identification in triage are not uniform across the nation. ● Healthcare providers and staff are ill-informed on resource points in life-threatening (for themselves or the patient) situations. |

Structural/ Systemic |

| 72 | Masuda et. al84 | Variation in community and ambulance care processes for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis | Meta-analysis | Peer-reviewed Literature | US | ● Out-of-hospital sudden cardiac arrest was more common throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, with an odds ratio of 1.38. ● Defibrillation by bystanders while waiting for an EMS response was significantly lower (OR = 0.69). ● Delays in EMS arrival were more common. |

Structural/ Systemic |

| 73 | Hasani-Sharamin et. al85 | Characteristics of Emergency Medical Service Missions in Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest and Death Cases in the Periods of Before and After the COVID-19 Pandemic | Cross-sectional | Mission data | Tehran, IR | ● The number of OOHCAs in 2019 was greater than that of 2018 or 2020. ● Respiratory distress and infection were more common in 2020 than 2019. ● History of diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease was more common in 2020. |

Clinical Outcomes |

| 74 | Jaffe et. al86 | The Role of Israel’s Emergency Medical Services During a Pandemic in the Pre-Exposure Period | Case | Mixed | IL | ● Out of 121 protected transports, 36.3% were referred to by medical sources. ● Out of 121 protected transports, 63.7% were identified as “suspected COVID-19” by dispatchers. ● EMS can work effectively in the pre-exposure period through instructing home quarantine, providing protected transport, and staffing border control checkpoints. |

Structural/ Systemic |

| 75 | Masterson et. al87 | Rapid response and learning for later: establishing high quality information networks and evaluation frameworks for the National Ambulance Service response to COVID-19 - The ENCORE COVID Project Protocol | Case | Survey responses from a national ambulance service | IE | ● The aim of this project was to disseminate pandemic related information using an evidence based framework. ● The project intends to systematically evaluate information frameworks for the Irish National Ambulance Service. |

Structural/ Systemic |

| 76 | Le Borgne et. al88 | Pre-Hospital Management of Critically Ill Patients with SARS-CoV-2 Infection: A Retrospective Multicenter Study | Cohort | Patient enrollment from regiospecific EMS calls | FR | ● Of patients with suspected COVID-19 no difference was found in hospital mortality between silent hypoxemia and hypoxemia with clinical acute respiratory failure. ● 53.4 of patients suspected to have COVID-19 presented with signs of respiratory distress ● All patients presenting with COVID-19 symptoms required high flow oxygen therapy. |

Treatment |

| 77 | Natalzia et. al89 | Evidence-based crisis standards of care for out-of-hospital cardiac arrests in a pandemic | Cohort | Cardiac arrest events in the CARES database | US | ● Favorable outcomes were associated with initial shockable rhythms or arrest witnessed by EMS. ● A proposed crisis standard of care protocol suggested to only initiate out-of-hospital resuscitation in these patients resulted in a prevalence of 70.5% favorable neurological outcomes. ● Incidences of favorable neurological outcome correlated with 6.3 free available beds |

Treatment |

Of the included studies, 44% were US-based. Primary taxonomy schema revealed the following prevalence of data: n=16 structural/systemic, n=23 clinical outcomes, n=7 clinical assessment, n=4 treatment, n=3 special populations, n=2 dispatch/activation, n=6 education, n=3 mental health, n=6 perspectives/experiences, and n=7 transport (see Table 1).

Discussion

Structural Considerations

Of the studies selected for inclusion in the “structural/systemic” domain, only 25% pertained to regions within the US. Only one study at the start of the pandemic (April 2020) rigorously assessed resource capacity and clinical competency at the national level, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Study participants were licensed practicing EMS clinicians in all 50 US states including the District of Columbia. Ventura et al report regular dissatisfactory decontamination practices both prior to and during the pandemic, required prolonged use of N95 respirators past the recommended efficacy period, and overall inadequate education for infection control and clinical considerations for COVID-19 patients.4 Notably, this captures a vulnerable representation of the US EMS system when there was minimal consensus on COVID-19 clinical symptomatology, transmissibility, appropriate precautionary measures, and discovery of vaccines. Globally, highly populated regions in the US, Germany, Turkey, Ireland and Denmark observed an increase in emergency medical calls of varying chief complaints, with many agency and regiospecific ambulance agencies reporting call volumes exceeding 60% compared to 2019.14,16,33 Based upon analysis of 911 de-identified patient care reports from the National EMS Information System (NEMSIS), between January 2018 to December 2020, Methley et al report an increase in frequency of on-scene death (1.3% to 2.4%), cardiac arrest (1.3% to 2.2%), and opioid related emergencies (0.6% to 1.1%) at the national level.6 States such as Kentucky observed higher rates of opioid related 911 calls, with a 50% increase in suspected opioid overdose death calls, while calls for other chief complaints remained static or declined.14 This is consistent with an apparent national trend of a worsening opioid epidemic, which we hypothesize has been only exacerbated by COVID-19. In February 2022, the American Medical Association issued a statement alleging an increase in drug related deaths in all US states and territories.90 To that end, it is critical to acknowledge that recent studies suggest black and brown communities are likely to be disproportionately harmed by both the opioid epidemic and the COVID-19 pandemic, as rates of morbidity and mortality are generally higher in this clinical population.91–94 Because EMS clinicians are crucial in overdose resuscitation and sustaining life of patients experiencing opioid overdose, prehospital providers may be uniquely responsible for understanding foundational systemic issues, such as racial inequity, and how they translate to emergency clinical care, which is not currently requisite by national EMS curriculum standards despite the measurable impact of care and access disparities experienced by patients of color.95–105

Mental Health

It has been well established in the literature that the COVID-19 pandemic has correlated with worse mental health outcomes in healthcare workers (HCWs).20 The strongest correlation among COVID-19 and psychological symptoms appeared in female-identifying HCWs ages 30–49 years.28 There is a continued need for strong psychological support and further investigation into determinants of poor mental health outcomes to develop evidence driven preventive measures.

EMS Activation

911 dispatchers at public safety answering points (PSAPs) are critical to functional operations of the EMS system. Albright et al investigated the efficacy of a dispatch screening tool to identify high suspicion of COVID-19 in patients based upon a questionnaire deployed by the 911 call taker in a study based in Massachusetts. The authors report a sensitivity of 74.9% (CI, 69.21–80.03) and a specificity of 67.7% (CI, 66.91–68.50) where n=263.47 Amiry and Maguire report an exponential increase in emergency medical calls globally during the pandemic, so further investigation into ways PSAPs can best support responding clinicians using evidence based practices may be warranted.21

Clinical Assessment, Treatment, and Outcomes

In a cohort study based in King County, Washington, US, Yang et al found that EMS responded to approximately 16% of COVID-confirmed cases. From study initiation to June 2020 (four months), the study cohort mortality was 52.4%. Fever, tachypnea, and hypoxia was only present in a limited quantity of patients.44 This is consistent with international prehospital consensus that suspicion of COVID-19 based solely on symptomatology should not be solely relied on for contemplating precautionary measures and isolation procedures. In a prehospital study in Denmark, patients under 60 years old were more likely to present with a loss of taste and/or smell upon assessment, however fever and cough were equally distributed across all age groups.49 In England, Marincowitz et al studied the accuracy of prognostic triage tools used prehospitally in the Yorkshire and Humber region. The WHO algorithm, PRIEST, NEWS2, and PMEWS tools all had high sensitivity for detecting COVID-19 infection.65 In Uppsala, Sweden, Mälberg et al report correlational findings of physiological respiratory parameters with patients suspected of having COVID-19. They found that the odds of COVID-19 diagnosis increased with respiratory rate, lower tidal volume, and negative inspiratory pressure.65 In Paris, France, Jouffroy et al report that pulse oximetry may be a reliable indicator for the need of mechanical ventilation in COVID-19 patients.38 It is important to acknowledge, however, that clinically significant inaccuracy of pulse oximetry for detecting hypoxia in darker skin patients has been well established in the literature.106,107 While many methods for assessing risk of COVID-19 infection exist, a universal guidance for prehospital assessment has not been established.

As COVID-19 is categorized as a respiratory illness, the majority of available articles on prehospital treatment had a significant focus on airway and breathing management. A study out of Paris reported that of the 15% of suspected COVID-19 patients who were found to be in cardiac arrest upon arrival, while the majority did not have prior cardiovascular risk factors present. This suggests that it is critical to provide sufficient respiratory support in the prehospital setting. It was found that of the suspected COVID-19 patients who were assessed by EMS personnel, 42% of BLS cases and 52% of ALS cases provided non-invasive ventilation, however, prehospital intubation was significantly less common as it was only present in 18% of ALS cases.50, Jouffroy et al report that of all COVID−19 suspected patients, 53.4% showed signs of respiratory distress. Most of these patients presented with respiratory rates of approximately 30/min and oxygen saturations of 72%. Additionally, all patients required some method of high flow oxygen treatment.88

Studies, such as one conducted by Hart et al, provides recommendations for personal protection protocols for EMS providers. They suggest that if endotracheal intubation is needed, it should only be attempted once and with the assistance of video laryngoscopy to minimize time exposure to aerosols. A HEPA filter should then be added following the placement of an advanced airway to further minimize risk for contamination of the provider and all other equipment present in the ambulance. In the event that advanced airway intervention is not possible or clinically indicated, it is suggested to use two individuals for BVM ventilation to ensure that an air-tight seal is made with the mask. In agreement with other established protocols, they stress that donning of PPE should be performed before any contact is made with a suspected COVID-19 patient.58

As mentioned previously, there is a shortage of available resources not just pre-hospital but in-hospital as well. Considerations need to be made to ensure resources are used in the most efficient manner. Natalzia et al proposes a protocol to maximize cardiac arrest resources in EMS in which one should only initiate resuscitation of a patient in cardiac arrest if the arrest is witnessed or a shockable rhythm is present. They state that this protocol could account for 70.5% of favorable neurological outcomes and provide 6.3 additional available hospital beds per patient.89

Education

As part of their initial education program, EMS students must generally acquire co-requisite field experience.1 During the early era of the COVID-19 pandemic, it may have been difficult to participate in field experience opportunities due to facility policy limitations designed to reduce transmission. Grawey et al examined an alternative model to the traditional ambulance “ride along” by providing a field-like experience in an emergency department setting. Grawey et al report that this alternative experience was likely as effective as traditional prehospital clinical internships. Additionally, they found university medical students to have increased knowledge regarding EMS roles and responsibilities, which may have beneficial implications for transfer of care.23 With regard to continuing education, the Commission on Accreditation for Prehospital Continuing Education (CAPCE) saw a 179% increase in EMS refresher courses during 2018 to 2020, with a 185% increase in asynchronous online learning.54 This may suggest that distance learning as a method for recertifying provider credentials may increase rates of recertification, in contrast with in-person continuing education programs.

Vaccine Perspectives and Prevalence

US EMS clinicians have also assumed nontraditional healthcare roles during the COVID-19 pandemic, such as in the case of a scope of practice expansion which allowed EMS clinicians to administer the COVID-19 to patients in states like New York, Massachusetts, and Vermont. Because EMS clinicians are highly trained in specific psychomotor clinical skills and knowledgeable in fundamental methods of patient assessment and treatment, it is likely that EMS in general has served unmeasurable utility through contributions in traditional and nontraditional roles. In April 2021, Gregory et al conducted a cross sectional study of nationally certified EMS clinicians rostered with the National Registry of Emergency Medical Technicians (NREMT). Of a sample size of n=2584, 70% reported receiving a COVID-19 vaccine. Of the sampled population, 53% had concerns regarding the safety of COVID vaccines, 39% felt it was not necessary, and 84% of providers who did not receive any dose of the COVID vaccine did not plan to get it in the future.25 The significant vaccine hesitancy amongst EMS clinicians poses a compelling public health concern, and approaches to mediate this, such as through local education and role modeling, may be necessary.108

Limitations

Little literature exists on the interrogated area of investigation, and studies that are relevant to the area are often preliminary and may require continued study and design modifications to increase external validity. While all attempts to achieve a high level of internal validity were made as captured by robust quality assessments at each level of investigation, it was not possible to accommodate for every confounder. While this review is not exhaustive, the authors affirm satisfaction in the methods and results available at the time of study.

Conclusion

US EMS clinicians are healthcare workers that have often held many roles and responsibilities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Within the subset domains of i. structural/systemic, ii. clinical outcomes, iii. clinical assessment, iv. treatment, v. special populations, vi. dispatch/activation, vii. education, viii. mental health, ix. perspectives/experiences, and x. transport, there is minimal high quality literature that faithfully reflect the status of modern American EMS in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The available data reflect strides in contemporary approaches to assessment, treatment, transport, and education, but fall short in accounting for care and access disparities influenced by social determinants. Continued investigation on the impact of COVID-19 on EMS systems and personnel is warranted to ensure informed, appropriate, and evidence-based preparation for future pandemic and infectious disease response.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to sincerely thank Paramedic Catherine Smith, EMT Rosa Turinetti, and Judith Inumerable for their expert opinions and experiences.

Funding Statement

The work is not funded by any specific source.

Institutional Disclaimer

The work is solely that of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views, policies, or opinions of their affiliated institutions, employers, or partners. It was not reviewed or endorsed by any specific institution in particular.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to data analysis, drafting or revising the article, have agreed on the journal to which the article will be submitted, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The investigators report no known conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise.

References

- 1.Pollak AN. Emergency care and transportation of the sick and injured. Jones Bartlett Learning. 2021;2021:1 [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Association of State EMS Officials. National EMS Scope of Practice Model 2019. Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration;2019. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ortaliza J. Covid-19 leading cause of death ranking. Peterson KFF Health Sys Track. 2022;9:15 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ventura C, Gibson C, Collier GD. Emergency medical services resource capacity and competency amid COVID-19 in the United States: preliminary findings from a national survey. Heliyon. 2020;6. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e03900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. Rayyan — a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Methley AM, Campbell S, Chew-Graham C, et al. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: a comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):579. doi: 10.1186/s12913-014-0579-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Methodology checklist 1: systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Available from: https://www.sign.ac.uk/what-we-do/methodology/checklists/. Accessed May 24, 2022.

- 8.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harris JD, Quatman CE, Manring MM, Siston RA, Flanigan DC. How to write a systematic review. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(11):2761–2768. doi: 10.1177/0363546513497567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quality appraisal of case series studies checklist. Edmonton (AB) institute of health economics; 2014.

- 12.“Critical Appraisal Checklists”. The Joanna Briggs institute critical appraisal tools for use in JBI systematic reviews; 2014.

- 13.Lin L, Chu H. Quantifying publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2018;74(3):785–794. doi: 10.1111/biom.12817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Slavova S, Rock P, Bush HM, Quesinberry D, Walsh SL. Signal of increased opioid overdose during COVID-19 from emergency medical services data. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;214:108176. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tien H, Sawadsky B, Lewell M, Peddle M, Durham W. Critical care transport in the time of COVID-19. CJEM. 2020;22(S2):S84–S88. doi: 10.1017/cem.2020.400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dahmen J, Bäker L, Breuer F, et al. COVID-19-stresstest für die sicherstellung der notfallversorgung: strategie und Maßnahmen der notfallrettung in Berlin [COVID-19 Stress test for ensuring emergency healthcare: strategy and response of emergency medical services in Berlin]. Anaesthetist. 2021;70(5):420–431. German. doi: 10.1007/s00101-020-00890-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levy MJ, Klein E, Chizmar TP, et al. Correlation between emergency medical services suspected COVID-19 patients and daily hospitalizations. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2021;25(6):785–789. doi: 10.1080/10903127.2020.1864074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Şan İ, Usul E, Bekgöz B, Korkut S. Effects of COVID-19 pandemic on emergency medical services. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75(5):e13885. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.13885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Handberry M, Bull-Otterson L, Dai M, et al. Changes in emergency medical services before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(Suppl 1):S84–S91. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soto-Cámara R, García-Santa-Basilia N, Onrubia-Baticón H, et al. Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on out-of-hospital health professionals: a living systematic review. J Clin Med. 2021;10(23):5578. doi: 10.3390/jcm10235578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amiry A A, Maguire BJ. Emergency Medical Services (EMS) calls during COVID-19: early lessons learned for systems planning (A narrative review). Open Access Emerg Med. 2021;13:407–414. doi: 10.2147/OAEM.S324568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Satty T, Ramgopal S, Elmer J, Mosesso VN, Martin-Gill C. EMS responses and non-transports during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;42:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.12.078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grawey T, Hinze J, Weston B. ED EMS time: a COVID-friendly alternative to ambulance ride-alongs. AEM Educ Train. 2021;5(4):e10689. doi: 10.1002/aet2.10689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fernandez AR, Crowe RP, Bourn S, et al. COVID-19 preliminary case series: characteristics of EMS encounters with linked hospital diagnoses. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2021;25(1):16–27. doi: 10.1080/10903127.2020.1792016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gregory ME, Powell JR, MacEwan SR, et al. COVID-19 vaccinations in EMS professionals: prevalence and predictors. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2021:1–9. doi: 10.1080/10903127.2021.1993391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eftekhar Ardebili M, Naserbakht M, Bernstein C, Alazmani-Noodeh F, Hakimi H, Ranjbar H. Healthcare providers experience of working during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. Am J Infect Control. 2021;49(5):547–554. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jaffe E, Sonkin R, Alpert EA, Zerath E. Responses of a pre-hospital emergency medical service during military conflict versus COVID-19: a retrospective comparative cohort study. Mil Med. 2021;usab437. doi: 10.1093/milmed/usab437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vanhaecht K, Seys D, Bruyneel L, et al. COVID-19 is having a destructive impact on health-care workers’ mental well-being. Int J Qual Health Care. 2021;33(1):mzaa158. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzaa158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jensen T, Holgersen MG, Jespersen MS, et al. Strategies to handle increased demand in the COVID-19 crisis: a coronavirus EMS support track and a web-based self-triage system. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2021;25(1):28–38. doi: 10.1080/10903127.2020.1817212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Firew T, Sano ED, Lee JW, et al. Protecting the front line: a cross-sectional survey analysis of the occupational factors contributing to healthcare workers’ infection and psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic in the USA. BMJ Open. 2020;10(10):e042752. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jouffroy R, Kedzierewicz R, Derkenne C, et al. Hypoxemia index associated with prehospital intubation in COVID-19 patients. J Clin Med. 2020;9(9):3025. doi: 10.3390/jcm9093025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tabah A, Ramanan M, Laupland KB, et al. Personal protective equipment and intensive care unit healthcare worker safety in the COVID-19 era (PPE-SAFE): an international survey. J Crit Care. 2021;63:280–281. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2020.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prezant DJ, Lancet EA, Zeig-Owens R, et al. System impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on New York City’s emergency medical services. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2020;1(6):1205–1213. doi: 10.1002/emp2.12301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berry CL, Corsetti MC, Mencl F. Helicopter emergency medical services transport of COVID-19 patients in the “first wave”: a National survey. Cureus. 2021;13(8):e16961. doi: 10.7759/cureus.16961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xie Y, Kulpanowski D, Ong J, Nikolova E, Tran NM. Predicting Covid-19 emergency medical service incidents from daily hospitalisation trends. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75(12):e14920. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.14920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maqueda Gonzalez R, Cerdán Santacruz C, García Septiem J, et al. Proctologic emergency consultation during COVID-19: comparative cross-sectional cohort study. Cir Esp. 2021;99(9):660–665. doi: 10.1016/j.cireng.2021.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Greenhalgh M, Dupley L, Unsworth R, Boden R. Where did all the trauma go? A rapid review of the demands on orthopaedic services at a UK Major Trauma Centre during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75(3):e13690. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.13690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bourn SS, Crowe RP, Fernandez AR, et al. Initial prehospital Rapid Emergency Medicine Score (REMS) to predict outcomes for COVID-19 patients. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021;2(4):e12483. doi: 10.1002/emp2.12483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nishikimi M, Rasul R, Sison CP, et al. Intubated COVID-19 predictive (ICOP) score for early mortality after intubation in patients with COVID-19. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):21124. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-00591-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Feng J, Yang Y, Zheng X, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on emergency patients in the resuscitation room: a cross-sectional study. J Clin Lab Anal. 2022;36(3):e24264. doi: 10.1002/jcla.24264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garcia-Castrillo L, Petrino R, Leach R, et al. European society for emergency medicine position paper on emergency medical systems’ response to COVID-19. Eur J Emerg Med. 2020;27(3):174–177. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Albrecht R, Knapp J, Theiler L, Eder M, Pietsch U. Transport of COVID-19 and other highly contagious patients by helicopter and fixed-wing air ambulance: a narrative review and experience of the Swiss air rescue Rega. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2020;28(1):40. doi: 10.1186/s13049-020-00734-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim guidance for Emergency Medical Services (EMS) systems and 911 public safety answering points (PSAPs) for COVID-19 in the United States; 2020.

- 44.Yang BY, Barnard LM, Emert JM, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) receiving emergency medical services in King County, Washington. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(7):e2014549. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.14549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Murphy DL, Barnard LM, Drucker CJ, et al. Occupational exposures and programmatic response to COVID-19 pandemic: an emergency medical services experience. Emerg Med J. 2020;37(11):707–713. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2020-210095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spangler D, Blomberg H, Smekal D. Prehospital identification of Covid-19: an observational study. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2021;29(1):3. doi: 10.1186/s13049-020-00826-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Albright A, Gross K, Hunter M, O’Connor L. A dispatch screening tool to identify patients at high risk for COVID-19 in the prehospital setting. West J Emerg Med. 2021;22(6):1253–1256. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2021.8.52563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cash RE, Rivard MK, Camargo CA Jr, Powell JR, Panchal AR. Emergency medical services personnel awareness and training about personal protective equipment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2021;25(6):777–784. doi: 10.1080/10903127.2020.1853858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moeller AL, Mills EHA, Collatz Christensen H, et al. Symptom presentation of SARS-CoV-2-positive and negative patients: a nested case-control study among patients calling the emergency medical service and medical helpline. BMJ Open. 2021;11(5):e044208. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jouffroy R, Lemoine S, Derkenne C, et al. Prehospital management of acute respiratory distress in suspected COVID-19 patients. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;45:410–414. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.09.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shekhar AC, Effiong A, Ruskin KJ, Blumen I, Mann NC, Narula J. COVID-19 and the prehospital incidence of acute cardiovascular events (from the Nationwide US EMS). Am J Cardiol. 2020;134:152–153. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2020.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Glenn MJ, Rice AD, Primeau K, et al. Refusals after prehospital administration of naloxone during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2021;25(1):46–54. doi: 10.1080/10903127.2020.1834656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jarvis S, Salottolo K, Berg GM, et al. Examining emergency medical services’ prehospital transport times for trauma patients during COVID-19. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;44:33–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2021.01.091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.March JA, Scott J, Camarillo N, Bailey S, Holley JE, Taylor SE. Effects of COVID-19 on EMS refresher course completion and delivery. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2021;1–6. doi: 10.1080/10903127.2021.1977876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Saberian P, Conovaloff JL, Vahidi E, Hasani-Sharamin P, Kolivand PH. How the COVID-19 epidemic affected prehospital emergency medical services in Tehran, Iran. West J Emerg Med. 2020;21(6):110–116. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2020.8.48679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Oulasvirta J, Pirneskoski J, Harve-Rytsälä H, et al. Paediatric prehospital emergencies and restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic: a population-based study. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2020;4(1):e000808. doi: 10.1136/bmjpo-2020-000808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hadley ME, Vaught AJ, Margolis AM, et al. 911 EMS activations by pregnant patients in Maryland (USA) during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2021;36(5):570–575. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X21000728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]