Abstract

Purpose:

This pilot study assesses the association of Raising Our Spirits Together (ROST), a technology-assisted, group-based cognitive behavioral therapy for depression, with rural adults’ depressive symptoms and anxiety.

Method:

Nine adults from rural Michigan participated in an open pilot of ROST. Clergy facilitated pilot groups. The pilot began in February 2020 in-person. Due to COVID-19, the pilot was completed virtually.

Results:

Mean depressive symptom scores, based on the PHQ-9, significantly decreased from pre-treatment (M = 14.4) to post-treatment (M = 6.33; t (8) = 6.79; P < .001). Symptom reduction was maintained at 3-month follow-up (M = 8.00), with a significant pattern of difference in depressive symptoms over time (F(2) = 17.7; P < .001; eta-squared = .689). Similar patterns occurred for anxiety based on the GAD-7. Participants attended an average of 7.33 of 8 sessions. Fidelity ratings were excellent.

Discussion:

ROST is a potentially feasible intervention for rural adults’ depressive symptoms. ROST offers a promising model for increasing treatment access and building capacity in rural areas.

Keywords: rural mental health, depression, technology-assisted cognitive behavioral therapy, clergy, church setting

Introduction

Depression is the leading cause of global disease burden (Friedrich, 2017), representing a significant public health concern. Almost 20% of adults in the United States experience depression during their lifetime (Hasin, Sarvet, & Meyers, et al., 2018; Kessler et al., 2005, 2003, 1994), whereas approximately 8% experience depression in any given two-week period of time (Brody, Pratt, & Hughes, 2018). When untreated, depression has devastating effects on work, family, and social life (Marciniak et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2003b), with estimates suggesting that the disorder costs the United States $210 Billion per year (Greenberg, Fournier, Sisitsky, Pike, & Kessler, 2015). The prevalence of depression, as well as its associated impacts, have been exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic, with recent literature finding that around one-third of US residents are experiencing depression during the pandemic (Czeisler et al., 2020; Luo et al., 2020; Salari et al., 2020).

Despite its high prevalence, only about one-third of persons with depression receive treatment (Kessler et al., 2005; Olfson, Blanco, & Marcus, 2016). This unacceptable depression treatment access disparity is even more salient among rural residents in the United States. Although rural Americans experience depression at rates similar to urban peers (Blazer, Kessler, McGonagle, & Swartz, 1994; Kessler et al., 1994; Probst et al., 2006; Wang, 2004), rural residents are significantly less likely to receive any mental health care (Fortney, Harman, Xu, & Dong, 2010; Wang et al., 2005). Although there are decades of research identifying efficacious interventions for depression, rural residents are unlikely to receive evidence-supported depression treatment or guideline concordant care (Fortney et al., 2010; Hartley, Bird, & Dempsy, 1999; Hauenstein & Peddada, 2007; Wang et al., 2005, 2006).

Rural residents in the United States face substantial barriers to care, the most significant of which may be the persistent shortage of mental health providers. Research reveals that 80% of masters-level social workers (MSW) and 90% of psychologists and psychiatrists practice exclusively in urban settings (Ellis, Konrad, Thomas, & Morrissey, 2009; Sawyer, Gale, & Lambert, 2006). As a result of the lack of available mental health professionals in the rural United States, over 60% of rural residents reside in designated mental health provider shortage areas (Health Resources and Services Administration, 2019). This provider shortage is exacerbated by access challenges, including high poverty and unemployment rates (Proctor, Semega, & Kollar, 2016; USDA Economic Research Service, 2017), high proportions of uninsured or underinsured persons (National Advisory Committee on Rural Health and Human Services, 2014; Newkirk & Damico, 2014), distance to care, and travel burden (Amundson, 2001; Gjesfjeld, Weaver, & Schommer, 2012; Hogan, 2003).

Even when mental health treatment may be available, some rural residents choose not to seek care. Self-reliance and independence, commonly held cultural values among rural residents, contribute to shame and stigma around mental health needs and treatment seeking (Buckwalter, 1991; Crumb et al., 2019; Hill & Fraser, 1995; Rost et al., 2002; Sheffler, 1999). Lack of anonymity also deters help seeking, as limited, close-knit social networks make it difficult to initiate formal mental health treatment without being noticed in rural communities (Logan, Stevenson, Evans, & Leukefeld, 2004; Rost et al., 2002; Smalley et al., 2010). Finally, rural residents often perceive cultural dissimilarities between themselves and mental health providers, whose personal and professional experiences are often urban-based (Rost, Smith, & Taylor, 1993). In fact, rural residents report a preference for seeking help from informal systems of care, such as clergy, family, and friends (Fox, Blank, Rovnyak, & Barnett, 2001; Fox, Merwin, & Blank, 1995; Merwin, Hinton, Dembling, & Stern, 2003; Merwin, Snyder, & Katz, 2006; Weaver, Himle, J., Elliott, Hahn, & Bybee, 2019). Collectively, these factors suggest formal mental health services and existing interventions, often developed and tested in urban settings, may not be available, accessible, or acceptable to many rural residents.

Increasing rural populations’ access to and utilization of depression treatment requires context-specific tailoring and adaptation that decrease known barriers to care (Barrera, Castro, Strycker, & Toobert, 2013; Krebs, Prochaska, & Rossi, 2010; Morrison, 2015; Weaver & Himle, 2017). As mental health providers are scarce in rural areas, and have been for decades, it is imperative to build community capacity to offer depression treatment in non-mental health settings that align with rural residents’ help-seeking preferences. Additionally, the opportunity to leverage technology to increase access to care has been further illuminated by the COVID-19 pandemic and by policy advocacy focused on building infrastructure to bring high speed internet to rural areas. It is critical to consider ways in which technology can be used to close the mental health treatment gap in rural communities.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is effective for treating depression in group and individual formats (e.g., Butler, Chapman, Forman, & Beck, 2006; Hofmann, Asnaani, Vonk, Sawyer, & Fang, 2012; Zhang et al., 2019), among diverse populations (e.g., Ayers, Sorrell, Thorp, & Wetherell, 2007; Wilson & Cottone, 2013), across a variety of treatment settings, and when delivered by non-mental health professionals in their usual care settings (e.g., Himle et al., 2014; Roy-Byrne et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2019). Growing evidence suggests the effectiveness of technology-assisted CBT (T-CBT; Andrews, Cuijpers, Craske, McEvoy, & Titov, 2010; Andrews et al., 2018; Firth et al., 2017; Li, Theng, & Foo, 2014). Though T-CBT is helpful for increasing access to care, it has better results when tailored for specific client groups, settings, or contexts and when paired with professional support (Andrews et al., 2010, 2018; Cuijpers, Noma, Karyotaki, Cipriani, & Furukawa, 2019; Wright et al., 2019).

Limited research testing the effect of CBT for depression and anxiety delivered in rural areas suggest promising results (Weaver & Himle, 2017); however, all studies include intervention adaptations and very few assess intervention fidelity. It is imperative to tailor T-CBT to address common experiences in the rural context, such as limited infrastructure, resources, and opportunities. These experiences impact access to treatment and also affect strategies for introducing core CBT concepts, such as behavioral activation. For instance, most examples of behavioral activation activities assume a level of infrastructure and resources available in the urban context; however, common activity examples, such as meeting a friend for coffee, may not be possible or much more complex to coordinate, for rural residents. Further, common rural cultural values, such as self-reliance and independence, influence thoughts and beliefs; however, T-CBT examples of negative thoughts and faulty beliefs do not typically include these rural values and experiences. Therefore, it is imperative to tailor depression treatment to address the unique needs and experiences of rural residents.

Given literature suggesting that CBT can be effectively delivered by non-mental health providers and that T-CBT with human support leads to better outcomes than self-guided T-CBT, it is also likely that clergy, who have strong interpersonal skills, could be trained to facilitate T-CBT in rural settings. However, very little attention has been paid to collaborating with rural stakeholders, including clergy, to optimize interventions for acceptability and sustainability (Crowther, Scogin, & Norton, 2010; Porter, Spates, & Smitham, 2004; Weaver & Himle, 2017).

Americans seek help for emotional issues from clergy at high rates (Chalfant et al., 1990; Wang, Berglund, & Kessler, 2003a; Weaver, 1995). Rural residents tend to be more religious than urban residents, and churches remain the heart of many rural communities, often providing social and safety net services for the community, such as food pantries and emergency funds (Braun & Maghri, 2004; Chandler & Campbell, 2002; Fischer, 1982). Among a sample of rural southerners in the US with untreated depression, 68% of whites and 93% of people of color stated they would seek mental health services if they were available at church (Fox et al., 2001). Literature suggests church-based interventions for health promotion have potential to reduce disparities in the United States (Hankerson & Weissman, 2012; Hays & Aranda, 2016); though need to underscore the importance of meaningful engagement and partnership with community stakeholders to support successful recruitment, participation, and sustainability. Limited work has examined church-based mental health interventions in rural areas, and to date only one identified study tested a church-based depression group (Mynatt, Wicks, & Bolden, 2008). Results were promising; however, the intervention did not leverage technology to support engagement and standardize the treatment approach.

Offering evidence-supported depression treatment at no cost in a non-stigmatizing, accessible church setting is likely to reduce barriers impacting rural populations’ treatment utilization. Receiving evidence-supported treatment from a preferred informal provider in an acceptable setting may increase openness to seeking traditional care if needed in the future. Therefore, the church setting is a promising option for disseminating evidence-based mental health treatment.

To better understand the feasibility and acceptability of offering depression treatment through rural churches, our research team conducted community-engaged work in rural Michigan. In order to obtain perspectives from a diverse group of community members with various sociodemographic statuses and mental health needs, we administered surveys to congregants at two local churches and to recipients of food bank services in our partner community. We found 25% of congregants and 49% of food bank recipients who responded to the survey screened positive for depression (Weaver et al., 2019, 2020). Survey results indicated that both congregants and recipients of food bank services were receptive to church-based mental health services, with 67% and 55% of respective respondents indicating that they would consider accessing mental health treatment through the church (Weaver et al., 2019, 2020). These preliminary studies led to sustained community partnerships and collaboration to develop and test a T-CBT, tailored for the rural context and for delivery by clergy.

The current pilot study aims to examine the effectiveness of a T-CBT delivered in groups and tailored for the rural context and for delivery by clergy, Raising Our Spirits Together (ROST), on rural adults’ depressive symptoms and anxiety. We began our pilot study in February 2020, with ROST delivered by clergy, in person, at a local church. The COVID-19 pandemic necessitated our ability to adapt to virtual delivery of ROST, using secure, web-based videoconferencing software, with clergy facilitating the virtual groups. This study contributes to our understanding of potentially promising, acceptable approaches to increase depression treatment access in underserved rural communities.

Method

Participants and Recruitment

Participants were recruited from a food bank and two churches in Hillsdale County, Michigan between January 2020 and June 2020. We recruited from these two distinct settings in hopes of recruiting a diverse group of participants, in terms of sociodemographic status and mental health needs. Initially, recruitment methods involved in-person visits to the food bank, referrals from clergy, and distribution of flyers at the food bank and participating churches. As circumstances changed with the COVID-19 pandemic and we could no longer safely engage in in-person research activities, recruitment methods involved referrals from clergy and virtual recruitment events at online worship services held by our partner churches. To participate in this study, individuals had to (1) be 18 years of age or older, (2) live in the participating community for at least one year, (3) screen positive for mild depressive symptoms (≥5) based on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001), and (4) not currently receive regular psychosocial treatment (≤1 session/month). Persons were not eligible to participate if they (1) did not speak English, (2) currently received regular psychotherapy for depression (≥1 session per month), (3) ever completed a course of CBT for depression (≥8 sessions), (4) had a psychotic disorder, (5) currently used non-prescribed opiates or cocaine, (6) had cognitive impairment (≥2 incorrect items on a 6-item mini mental status exam, or (7) had prominent suicidal/homicidal ideation with imminent risk. Although research staff trained to a standard conducted Mini-International Psychiatric Interviews (v. 7.0; Sheehan, 2015) with all participants, probable diagnosis of depressive disorder was not required for study eligibility. This approach increases access to treatment for underserved persons with a range of symptoms, helps fill groups faster, and aligns with potential future real-world implementation. Further, medication treatment for depression was not considered an exclusion criterion. Medication and psychosocial treatment are often complementary, and rural residents are more likely to have access to medication treatment for depression than psychosocial care. Therefore, we believed that excluding individuals taking medication would leave a study sample that would not match well with the typical consumers who might use the technology-assisted treatment in the future.

Raising Our Spirits Together

Raising Our Spirits Together (ROST) is an eight-session, group-based T-CBT intentionally tailored for the rural context and for delivery by clergy. ROST was created in and is housed on “Entertain Me Well,” an online platform for delivering CBT, developed by two of the study authors, Joseph A. Himle and Addie Weaver, to intentionally enhance treatment engagement and flexibility without compromising fidelity to core CBT concepts (i.e., behavioral activation, cognitive restructuring, and problem solving). Entertain Me Well uses a mix of video-based content, text, images, and examples, to deliver T-CBT and includes an accompanying workbook with in-session and between exercises.

Entertain Me Well includes three key innovations: (1) entertaining delivery of T-CBT content through an engaging, character-driven storyline, (2) quick and easy, low-cost treatment tailoring capabilities while retaining core CBT elements, and (3) presentation of T-CBT content in a simple, straightforward manner that avoids text-heavy approaches and jargon, appealing to multiple learning preferences.

Entertain Me Well’s T-CBT for depression includes an introductory session that focuses on psychoeducation of depression and an introduction of CBT, two sessions focused on behavioral activation (Sessions 2 and 3), two sessions focused on cognitive restructuring (Sessions 4 and 5), one session focused on identifying faulty beliefs (Session 6), one session that introduces problem solving (Session 7), and a final session that reviews all skills and tools and facilitates relapse prevention planning (Session 8). For more information about Entertain Me Well, see Himle, Weaver, Zhang, & Xiang, 2021 and Weaver, Zhang, Xiang, Felsman, & Himle, in press.

All ROST sessions were tailored for the rural context and for delivery by clergy through a community-engaged, iterative process. Community partners and researchers collaborated to identify opportunities for tailoring images, text, examples, and vignettes in each session to make the content highly relevant and relatable for this client group and delivery setting. For example, the start of each ROST session includes a quote from scripture that connects to the core CBT content being taught that day. Additionally, the tailoring process led to the intentional identification of potential activities for behavioral activation that can be done for free or inexpensively within the rural context, a context that often lacks the resources and infrastructure that is typically present in urban and suburban contexts. Further, aspects of rural culture related to themes favoring self-reliance and independence, led to customizations of the intervention, such as the inclusion of “I cannot ask for help” as an example of a faulty belief explored in Session 6. Images reflecting rural and natural scenes, as well as people actively engaging with each other in rural environments, were selected and incorporated into ROST. Attention was placed on selecting images that reflected diversity in terms of gender, age, race/ethnicity, abilities, and family composition. ROST also includes a tailored, accompanying participant workbook that provides in-session activities and homework exercises. Finally, ROST has a facilitator manual that supports clergy delivering the intervention.

ROST is provided once, weekly, with each group session lasting approximately 90 min. Clergy facilitate all ROST sessions. Initially, ROST was designed for in-person delivery in rural churches; however, the COVID-19 pandemic necessitated adaptations for virtual, group-based delivery via secure, web-based, videoconferencing software (e.g., Zoom).

Group Leaders

Two clergy in our partner rural community were selected as group leaders for this pilot study. Each clergy independently led one ROST pilot group. Both clergy members participated in structured qualitative interviews exploring their understanding of depression etiology and treatment. We designed ROST such that key concepts related to CBT would be covered in the online platform and group facilitators would not require comprehensive CBT training and certification before leading groups. We believe this approach fits well with the time and effort limitations faced by busy clergy members when presented with an opportunity to provide a new service to their congregants and the larger community.

Although ROST’s core CBT content is delivered via a T-CBT platform, clergy facilitate group exercises, lead discussion of session concepts, answer questions and provide clarification on concepts as needed, and introduce and review homework/action plans. Group leaders were selected due to their strong interpersonal skills and significant experience facilitating small group programs; however, clergy leading ROST groups must understand depression, CBT, and group facilitation skills. Given this, group leaders completed a two-day, multimedia training that provided a combination of video-based and face to face content, including case studies and role plays, focused on DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder and persistent depressive disorder, CBT, suicidal ideation and safety planning, and group facilitation. Group leaders also completed a one-day, session-by-session overview of the ROST treatment program, its structure, and specific roles and responsibilities of group leaders facilitating the intervention program. This ROST-specific training included thorough review of the ROST Facilitator Manual, role plays related to introducing and supporting session concepts, introducing in-session activities, and reviewing homework exercises. The ROST-specific training also emphasized treatment fidelity and adherence. Finally, group leaders completed Dr. Kenneth Kobach’s online training in CBT for depression. All ROST sessions were audio recorded with participants’ consent. Licensed clinicians on the research team listened to the audio recorded sessions and provided weekly supervision to group leaders during treatment.

Overview of Pilot Design and Procedures

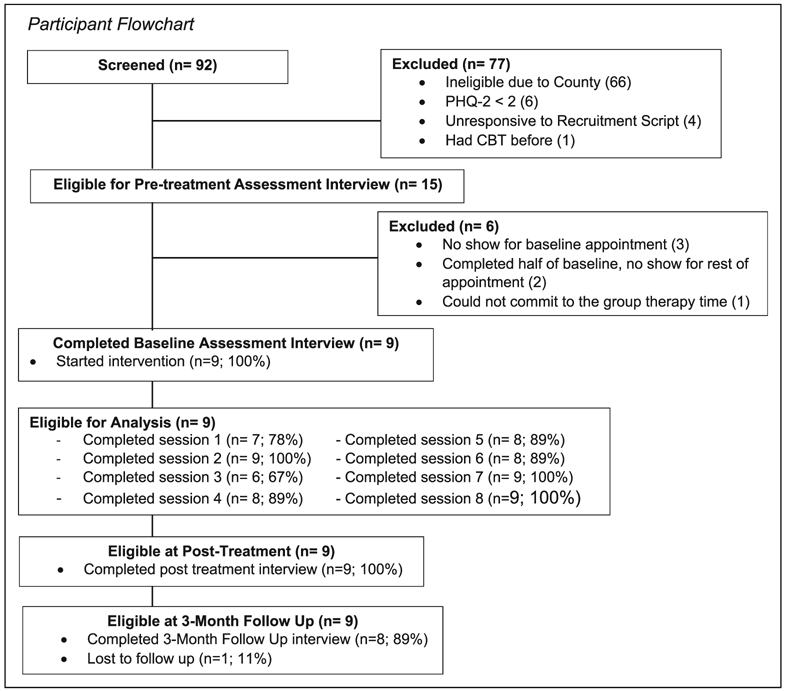

This pilot study was approved by the University of Michigan School of Medicine’s Institutional Review Board (IRBMED). A single group pre-post-test design was employed to compare outcomes over time across pre-treatment, post-treatment, and three-month follow-up time points. Figure 1 shows participant flow through the pilot study.

Figure 1.

Participant flowchart.

Individuals who agreed to be screened completed a brief screening interview either in-person or over the phone. The screening interview assessed individuals’ depressive symptoms using the PHQ-2 (Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2003), cognitive functioning using a 6-item screener (Callahan et al., 2002), place of residence, and current psychosocial treatment.

Individuals who met preliminary screening criteria were invited to provide informed consent and participate in a pre-treatment assessment interview. Pre-treatment interviews were conducted in-person at one of our partner churches (Pilot Group 1; prior to COVID-19 pandemic) or virtually via secure, web-based videoconferencing software (Pilot Group 2; during COVID-19 pandemic). Pre-treatment assessment interviews were conducted by research staff with mental health backgrounds who were trained to a standard. The pre-treatment assessment interviews took approximately 1.5 hours to complete, and participants received a $25 incentive for their time.

Participants who met all eligibility criteria after completing the pre-treatment assessment interview were invited to participate in the ROST intervention group program. Participants attended weekly ROST sessions that lasted approximately 90 min. At the end of each session, participants were asked to complete measures, including the PHQ-9, to assess their depressive symptoms across sessions. If participants endorsed anything above a zero (0) on item 9 of the PHQ-9, asking about suicidal ideation, a research associate immediately administered the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (CSSRS) and contacted a licensed clinician on the research team for clinical back-up. The licensed clinician directly connected with participants to assess risk and engage in appropriate safety planning and referrals. Participants received a $10 incentive for completing the session measures.

The first ROST pilot group started in person at one of our partner churches in February 2020. Three sessions into the first pilot group, the COVID-19 pandemic necessitated stoppage of all in-person research activities. After in-depth discussion with participants and group leaders, we adapted to virtual delivery of ROST, with the same clergy facilitating. The first pilot group was completed virtually (Sessions 4–8). Recruitment for and delivery of the second ROST pilot group was completely virtual, with all pre-treatment assessment interviews and sessions conducted via secure, web-based, videoconferencing software.

After the 8 weeks of active ROST treatment, participants were invited to complete a post-treatment assessment interview. Participants were also asked to complete a three-month follow-up assessment interview 12 weeks after completing the ROST intervention. The post-treatment and three-month follow-up assessment interviews took approximately 1 hour to complete. All post-treatment and three-month follow-up assessment interviews were completed virtually using secure, web-based videoconferencing software and conducted by research staff with mental health backgrounds who were trained to a standard. Participants received a $25 incentive for completing each of these assessment interviews.

Measures

Psychiatric Diagnoses

The MINI Neuropsychiatric Interview v. 7.0 (MINI; Sheehan, 2015) was used to assess symptoms of mental health disorders at pre-treatment, post-treatment, and three-month follow-up timepoints. Trained research associates, blinded to participants’ treatment condition, administered the MINI. The MINI is a widely used structured, diagnostic interview with excellent test-retest and interrater reliability (Sheehan, 2015).

Depressive Symptoms

Depressive symptoms were assessed via the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001). The PHQ-9 includes nine items that ask respondents to indicate how often they have been bothered by problems associated with depression (e.g., little interest or pleasure in doing things; feeling down, depressed, or hopeless) over the last 2 weeks. Response options range from zero (not at all) to three (nearly every day), with total scores ranging from 0 to 27. Scores of 10 or above indicate probable depressive disorder, whereas scores of five to nine suggest mild depressive symptoms. The PHQ-9 is well-established and widely used, with excellent internal reliability and test-retest reliability (Kroenke & Spitzer, 2002). After the nine items focused on depressive symptoms, the PHQ-9 also asks respondents to rate, on a scale of zero to three, how difficult their depressive symptoms have made it for them to do their work, take care of things at home, or get along with other people. The PHQ-9 was administered at pre-treatment, post-treatment, three-month follow-up, and at each of the eight weekly ROST treatment sessions.

Generalized Anxiety Symptoms

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7; Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams, & Lowe, 2006) was used to measure symptoms of generalized anxiety. The GAD-7 is comprised of seven items that ask respondents how often they have experienced common problems associated with generalized anxiety (e.g., feeling nervous, anxious, on edge; not being able to stop or control worrying) over the last 2 weeks. Response options range from zero (not at all) to three (nearly every day) and total scores range from 0 to 21. Scores greater or equal to 10 suggest clinically relevant symptoms of generalized anxiety. The GAD-7 has good internal consistent and test-retest reliability, as well as adequate criterion and construct validity (Spitzer et al., 2006). Participants completed the GAD-7 as part of pre-treatment, post-treatment, and three-month follow-up assessments.

Treatment integrity

A trained independent evaluator with a doctorate in social work and significant experience in CBT rated ROST fidelity using an adapted version of the Cognitive Therapy Rating Scale (Young & Beck, 1980) which measures both protocol adherence and therapist competence. Scale adaptations for ROST included specific emphasis on facilitation of content presented by the technology-assisted intervention program. Ratings range from one (ineffective) to five (extremely effective). A rating of 4–5 is considered within protocol.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were conducted to describe the sample’s sociodemographic and clinical characteristics at pre-treatment, as well as participants’ treatment attendance and treatment integrity ratings made by an independent assessor.

Within-group differences between pre-treatment and post-treatment outcomes were assessed using paired samples t-tests with two tailed tests at an alpha of .05. The within group effect sizes were calculated using a small sample size corrected Hedge’s g (Cooper, Hedges, & Valentine, 2019). The pattern of difference on outcomes across the three timepoints (pre-treatment, post-treatment, 3-month follow-up) was evaluated using Repeated Measures Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). One participant did not complete the 3-month follow-up assessment interview. Missing data for this participant was imputed using their pre-treatment scores on the PHQ-9 and GAD-7. Effect sizes for Repeated Measures ANOVA were calculated using the partial eta-squared. All analyses were conducted using SPSS v 27 (IBM Corp).

Distributional assumptions and outliers were evaluated for all statistical analyses. No concern was revealed except an outlier observation (n = 1) that impacted the distribution of the depressive symptom variable at post-treatment. Sensitivity analyses were conducted with and without the outlier, and the results stayed consistent with both analyses. Therefore, in this paper, we present results based on the using all values, including the one outlier.

Two established criteria for assessing clinical significance were also utilized (Dear et al., 2013). Descriptive statistics were conducted to examine (1) the proportion of participants who scored ≥10 at the pre-treatment assessment interview and <10 at the post-treatment assessment interview and (2) the proportion of participants with ≥50% reduction in their PHQ-9 scores from the pre-treatment assessment interview to the post-treatment assessment interview. We also assessed the proportion of participants meeting each criterion when examining PHQ-9 scores on the pre-treatment assessment interview and the three-month follow-up assessment interview.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Nine individuals provided informed consent, completed the pre-treatment assessment interview, met study eligibility criteria, and began the Raising Our Spirits Together (ROST) group depression treatment program. Analyses include all participants who started the treatment.

As shown in Table 1, the majority of participants identified as female (n = 6; 66.7%) and White (n = 8; 88.9%). On average, participants were 65 years old (SD = 6.25), with ages ranging from 56 to 76 years old. Over half of participants (n = 5; 55.6%) reported being divorced (n = 2; 22.2%), widowed (n =1; 11.1%), or single (n = 2; 22.2%). Two-thirds of the sample (n = 6; 66.7%) reported annual incomes of $39,999 or less, with 22.2% (n = 2) participants reporting annual incomes less than $10,000. Two-thirds (n = 6) of the sample also reported having a college education, with two participants completing an associate’s degree (22.2%), three participants completing a bachelor’s degree (33.3%), and one participant completing a graduate/professional degree (11.1%). One-third of participants (n = 3) indicated that they were currently employed, either full time (n = 1; 11.1%) or part time (n = 2; 22.2%). All but one participant reported affiliation with a church (n = 8; 88.9%).

Table 1.

Baseline Sociodemographic Characteristics (N = 9).

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 6 | 66.7 |

| Male | 3 | 33.3 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 1 | 11.1 |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 8 | 88.9 |

| Race | ||

| American Indian/native Alaskan | 1 | 11.1 |

| Asian American | 0 | 0 |

| Black/African American | 0 | 0 |

| White | 8 | 88.9 |

| Relationship status | ||

| Married | 4 | 44.4 |

| Divorced | 2 | 22.2 |

| Widowed | 1 | 11.1 |

| Single | 2 | 22.2 |

| Living situation | ||

| Own house/Apartment | 6 | 66.7 |

| Rent house/Apartment | 2 | 22.2 |

| Living with family/Friends | 1 | 11.1 |

| Church affiliation | ||

| Yes | 8 | 88.9 |

| No | 1 | 11.1 |

| Educational Attainment | ||

| 9th-11th grade | 1 | 11.1 |

| High school graduate/GED | 1 | 11.1 |

| Some college, no degree | 1 | 11.1 |

| Associates degree | 2 | 22.2 |

| Bachelors degree | 3 | 33.3 |

| Graduate/professional degree | 1 | 11.1 |

| Employment status | ||

| Employed, full time | 1 | 11.1 |

| Employed, part time | 2 | 22.2 |

| Retired | 4 | 44.4 |

| Unemployed | 1 | 11.1 |

| Not reported | 1 | 11.1 |

| Annual income | ||

| Less than $10,000 | 2 | 22.2 |

| $10,000–$19,999 | 2 | 22.2 |

| $20,000–$39,999 | 2 | 22.2 |

| $40,000–$59,999 | 0 | 0 |

| $60,000–$79,999 | 1 | 11.1 |

| $80,000+ | 1 | 11.1 |

| Don’t know | 1 | 11.1 |

| M | SD | |

| Age (range: 56–76 years old) | 65 | 6.25 |

Pre-treatment clinical characteristics, reported in Table 2, indicate that the majority of participants had symptoms indicating probable Major Depressive Episode (n=7; 77.8%) and Major Depressive Disorder (n=6; 66.7%). Two participants’ (22.2%) symptoms indicate they had probable persistent depressive disorder. Five participants (55.6%) reported symptoms suggesting probable Suicidality. At the pre-treatment assessment, participants scored an average of 14.4 (SD=5.39) on the PHQ-9 and an average of 7.89 (SD=5.28) on the GAD-7.

Table 2.

Pre-Treatment Clinical Characteristics (N = 9).

| M | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Mental health symptom measures | ||

| Patient health questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) | 14.4 | 5.39 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder-7 (GAD-7) | 7.89 | 5.28 |

| n | % | |

| MINI v. 7 probable diagnoses | ||

| Major depressive episode (MDE) | 7 | 77.8 |

| Major depressive disorder (MDD) | 6 | 66.7 |

| Persistent depressive disorder (PDD) | 2 | 22.2 |

| Suicidality | 5 | 55.6 |

| Manic episode | 0 | 0 |

| Bipolar disorder 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Bipolar disorder 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Bipolar disorder unspecified | 0 | 0 |

| Panic disorder | 0 | 0 |

| Agoraphobia | 0 | 0 |

| Social anxiety disorder | 3 | 33.3 |

| Obsessive compulsive disorder | 0 | 0 |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 1 | 11.1 |

| Alcohol use disorder | 0 | 0 |

| Substance use disorder | 1 | 11.1 |

| Psychotic disorder | 0 | 0 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 1 | 11.1 |

| Antisocial personality disorder | 0 | 0 |

Treatment Effect

Primary outcome: depressive symptoms

A paired sample t-test revealed an overall significant reduction in depressive symptoms from pre-treatment to post-treatment (t (8) = 6.79; P < .001), with average PHQ-9 scores decreasing from 14.4 (SD = 5.39) at pre-treatment to 6.33 (SD = 4.90) at post-treatment (Table 3). The small sample size corrected Hedge’s g demonstrates a within group effect size of 2.03 (var = .341; 95% CI: 1.37, 2.70) Analysis of clinical significance showed that 6 of the 9 participants (66.7%) scored ≥ 10 on the PHQ-9 at pre-treatment and subsequently scored <10 at post-treatment. Eight of nine participants (88.9%) had a reduction of ≥50% of pre-treatment PHQ-9 scores at post-treatment.

Table 3.

Bivariate Differences in Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms from Pre-treatment to Post-treatment (N = 9).

| Pre-treatment M (SD) | Post-treatment M (SD) | t (df) | P | Small sample size corrected Hedge’s g | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | |||||

| PHQ-9 | 14.4 (5.39) | 6.33 (4.90) | 6.79 (8) | <.001 | 2.03 |

| Secondary outcome | |||||

| GAD-7 | 7.89 (5.28) | 3.56 (3.75) | 2.41 (8) | 0.04 | 0.727 |

Repeated Measures ANOVA showed a significant pattern of difference on depressive symptoms scores over time (F(2)=17.7; p<.001; Table 4). The partial eta-squared demonstrates a within group effect size of 0.689. Five of the eight participants (62.5%) who completed the three-month follow-up time point who scored ≥10 on the PHQ-9 at pre-treatment, scored <10 at three-month follow-up and had a reduction of ≥50% of pre-treatment scores at three-month follow-up.

Table 4.

Repeated Measures ANOVA Examining Pattern of Difference Over Time In Raising Our Spirits Together (N = 8).

| Pre-treatment M (SD) | Post-treatment M (SD) | 3-month follow-up M (SD) | F(df) | P | Partial eta-squared | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | ||||||

| PHQ-9 | 14.4 (5.39) | 6.33 (4.90) | 6.75 (6.11) | 19.4(2) | <.001 | 0.734 |

| Secondary outcome | ||||||

| GAD-7 | 7.89 (5.23) | 3.56 (3.75) | 4.50 (3.82) | 8.44(2) | 0.004 | 0.547 |

| Repeated Measures ANVOA With Missing 3-Month Follow-Up Data for One Participant Imputed With Their Baseline Symptom Scores (N = 9). | ||||||

| Pre-treatment M (SD) | Post-treatment M (SD) | 3-month follow-up M (SD) | F(df) | P | Partial eta-squared | |

| Primary outcome | ||||||

| PHQ-9 | 14.4 (5.39) | 6.33 (4.90) | 8.00 (6.84) | 17.7(2) | <.001 | 0.689 |

| Secondary outcome | ||||||

| GAD-7 | 7.89 (5.23) | 3.56 (3.75) | 4.67 (3.61) | 5.23(2) | 0.018 | 0.395 |

Average PHQ-9 scores by session, reported in Table 5, show a downward trend toward reduced depressive symptoms scores as more sessions were completed.

Table 5.

Treatment Attendance and Mean PHQ-9 Score by Session (N = 9).

| M | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of sessions completed | 7.33 | 1.12 |

| PHQ-9 scores | ||

| Session 1 (n = 7) | 12.7 | 5.64 |

| Session 2 (n = 9) | 10.1 | 6.17 |

| Session 3 (n = 6) | 7.33 | 3.61 |

| Session 4 (n = 8) | 9.13 | 6.22 |

| Session 5 (n = 8) | 7.75 | 5.5 |

| Session 6 (n = 8) | 7.88 | 6.69 |

| Session 7 (n = 9) | 8.89 | 7.36 |

| Session 8 (n = 9) | 7.33 | 6.28 |

Secondary Outcome: Generalized Anxiety Symptoms

A paired samples t-test revealed a significant reduction in generalized anxiety symptoms from pre-treatment to post-treatment (t (8) = 2.41; P = .04), with average GAD-7 scores decreasing from 7.89 (SD = 5.28) at pre-treatment to 3.56 (SD = 3.75) at post-treatment (Table 3). Based on a small sample size corrected Hedge’s g, this demonstrates a within group effect size of .727 (var = .140, 95% CI: .452, 1.00). Repeated measures ANOVA showed a significant pattern of difference on generalized anxiety symptoms over time, across the three timepoints (F(2) = 5.23; P = .018). The partial eta-square indicates a within group effect size of 0.395.

Treatment Adherence and Attrition

All nine participants (100%) remained in the study throughout the entire active treatment phase and completed post-test assessment interviews. Eight of the nine participants (88.9%) were retained at the three-month follow-up time point and completed their final assessment.

Participants attended an average of 7.33 (SD = 1.12) of eight ROST treatment sessions (Table 5). Eight of the nine participants (88.9%) attended seven or eight ROST sessions, with five participants (55.6%) attending all eight sessions and three participants (33.3%) attending seven of the eight sessions. One participant in the first pilot group (11.1%) missed three sessions due to challenges related to the COVID-19 pandemic and transitioning from in-person to virtual group treatment delivery.

Treatment Fidelity

Independent assessor ratings indicate 100% adherence to intervention components by group leaders across all sessions, for both pilot groups (Table 6). Average competency ratings across the eight sessions were 4.54 and 4.64, for each group, respectively. Average competency ratings across groups, for each session ranged from 4.50 to 4.95.

Table 6.

Fidelity Ratings Within and Across Group Leaders.

| Adherence |

Competence |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Group 2 | M | Group 1 | Group 2 | M | |

| Session 1 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 4.45 | 4.55 | 4.50 |

| Session 2 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 4.33 | 4.67 | 4.50 |

| Session 3 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 4.39 | 4.61 | 4.50 |

| Session 4 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 4.75 | 4.50 | 4.63 |

| Session 5 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 4.50 | 4.60 | 4.55 |

| Session 6 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 4.60 | 4.60 | 4.60 |

| Session 7 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 4.78 | 4.67 | 4.73 |

| Session 8 | 100% | 100% | 4.95 | 4.95 | ||

| Average | 100% | 100% | 4.54 | 4.64 | ||

Discussion and Implications for Practice

This pilot study of ROST suggests this group-based T-CBT for depression, tailored for the rural context and delivery by clergy, offers a potentially promising approach for increasing access to evidence-supported depression treatment in underserved, rural communities. Participants meaningfully engaged in treatment, consistently attending ROST sessions. Changes in depressive symptoms over time were both statistically and clinically significant in the expected direction. Symptoms of generalized anxiety, a secondary outcome, also significantly improved over time. Fidelity ratings indicate the feasibility of delivering ROST in the community, as clergy facilitating ROST groups adhered to the treatment protocol and competently facilitated intervention groups. These findings add support to the growing literature that T-CBT is likely to be effective, particularly with human support (e.g., Andrews et al., 2018; Cuijpers et al., 2019; Ebert et al., 2015; Newby, Twomey, Li, & Andrews, 2016; Wright et al., 2019). Further, results echo evidence demonstrating that with adequate training and support, non-mental health professionals can effectively deliver CBT in community settings (Himle et al., 2014; Roy-Byrne et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2019). Our study extends these findings to the rural context and to clergy, showing this model has utility for building capacity for delivering depression treatment in rural areas.

Treatment attendance in this study was excellent, as all participants completed ROST. Eight of the nine participants (88.9%) completed either seven of eight or all eight of the group sessions. Treatment attendance among participants in this study surpasses attendance typically reported in T-CBT programs, where lack of engagement and early drop out have been critical concerns. Individuals using currently available T-CBT programs commonly drop out early in their course of treatment and do not re-engage with the program (Fernandez, Salem, Swift, & Ramtahal, 2015). Meta-analytic work further shows that the median completion rate for T-CBT programs is 54% (Waller & Gilbody, 2009), with an increase to a 65% median completion rate among studies of T-CBT with in-person guidance (Van Ballegoojen et al., 2014). It is likely that the intentional community-engaged tailoring process we engaged in to develop ROST positively impacted attendance, as images, text, examples, and vignettes were intentionally customized to be relevant and meaningful for the rural context and delivery by clergy. Research consistently indicates that treatment tailoring increases intervention uptake, acceptability, and sustainability (Barrera et al., 2013; Krebs et al., 2010; Morrison, 2015; Noar, Benac, & Harris, 2007); yet, to our knowledge existing T-CBT programs for depression utilize a one-size-fits-all approach and cannot be easily modified without substantial cost, time, and effort (Twomey, O’Reilly, & Meyer, 2017). Additionally, the use of an entertaining, character-driven storyline to introduce and reinforce core CBT concepts and show how they are applied in the character’s life may have positively impacted ROST treatment attendance as well. Each session included an “episode” that ended with a cliffhanger, similar to serial television shows. This entertaining, narrative approach was intentionally developed to increase engagement as well as increase participants’ comprehension, learning, and memory (Dahlstrom, 2014) related to CBT skills and tools. Although only two of the nine pilot participants were affiliated with one of the group leaders ‘ churches, it is important to consider that existing connections between clergy leading groups and participants may have positively impacted treatment engagement. More research is needed to understand the impact of treatment tailoring, entertainment, and facilitation by local clergy on ROST participants’ treatment attendance.

Findings also suggest that ROST has promise for treating depression, with statistically and clinically significant decreases in depressive symptoms at post-treatment and a significant pattern of difference on depressive symptoms across the three time points (pre-treatment, post-treatment, and three-month follow-up). The within group treatment effect between pre-treatment and post-treatment was large, with a small sample size corrected Hedge’s g of 2.03. The within group treatment effect across all three time points remained large, with a partial eta-squared of .689. A review of within group effects of CBT for depression among adults reports an aggregate effect size of 1.19 for self-report outcome measures (Rubin & Yu, 2017). A meta-analysis of T-CBT reported an overall superiority effect size of .670 over control conditions, with effect sizes across studies ranging from .19 to 1.56 (Andrews et al., 2018). Results suggest meaningful clinical significance as well, with the majority of participants’ (66.7%) depressive symptom scores changing from ≥10 on the PHQ-9, indicating probable major depressive disorder, to ≤10 on the PHQ-9. Four participants (44.4%) who scored ≥10 on the PHQ-9 at pre-treatment, scored <5 on the PHQ-9 at post-treatment, indicating that these participants did not even have mild depressive symptoms at the end of treatment. Participants completed the ROST program during a time of high stress during the first 6 months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Even within that context, results suggest significant improvement in depressive symptoms, as well as anxiety symptoms.

When assessing session-by-session change in depressive symptom scores during ROST, based on the PHQ-9, findings show the largest deceases in average depressive symptom scores occurred between Session 1 and Session 3. Sessions 2 and 3 introduce behavioral activation and teach group members tools and skills related to activity scheduling, identifying activities for enjoyment and accomplishment, and setting activity goals. Previous research in rural contexts suggests behavioral activation may be particularly impactful for addressing rural adults’ depression (Weaver & Himle, 2017). As ROST content began introducing new skills, including cognitive restructuring strategies in Session 4 and problem solving in Session 7, weekly average depressive symptom scores slightly increased. It may be that the average depressive symptom scores were higher at the end of these sessions because participants were just learning new skills and tools that are often challenging to master.

Additionally, findings suggest clergy effectively facilitated ROST group sessions. Fidelity ratings completed by a doctoral-level independent assessor with deep CBT experience revealed ROST group leaders completely adhered to the ROST program and met competency expectations, with ratings between four and five, on a zero to five scale, across all pilot group sessions. Our results align with growing literature suggesting non-mental health providers are able to support CBT with adequate training (Himle et al., 2014; Roy-Byrne et al., 2005, 2010; Zhang et al., 2019). Our findings specifically indicate that clergy may be well-positioned to facilitate T-CBT groups in rural communities.

Given the decades-long shortage of mental health professionals in rural areas (Ellis et al., 2009; Merwin et al., 2003; Sawyer, Gale, & Lambert, 2006), it is imperative to identify existing helpers in the community and offer mental health interventions in places rural residents naturally go for help. Building capacity to deliver technology-assisted depression treatment among clergy is one potentially important approach to decrease barriers related to the lack of mental health professionals, cost, distance to care, travel burden, and stigma. While this study focused on clergy and the church setting, the ROST intervention model (e.g., utilizing technology and community-based organizations) has broader utility to close mental health treatment access disparities in rural areas.

Our pilot study also has implications for leveraging technology to enhance depression treatment access in the rural context. Though we initially designed ROST for in-person delivery of the T-CBT program by clergy in church settings, the COVID-19 pandemic necessitated adapting the study for virtual delivery. This led to an innovation allowing clergy leading groups to engage with group members via videoconferencing software, sharing their screens to show the ROST platform. Delivering ROST in this way aligned with the intervention’s focus on engagement and entertainment, as it was consistent with the style of a watch party available through popular streaming services.

The transition from in-person to virtual delivery was successful in part because participants had the access to technology, in terms of both devices and internet access. Participants’ access to technology may have been due to recruitment methods, particularly for the second pilot group, in which recruitment materials specified that ROST groups would be held virtually. Individuals who did not have access to a device or the internet likely did not reach out about participating in the study. Although the access to technology among this sample may not generalize to other rural communities, it likely speaks to the trend of increasing access to internet and smartphones in rural areas. As of 2019, 63% of rural residents reported having broadband internet access at home (Pew Research Center, 2019b) and 71% of rural residents reported having smartphones (Pew Research Center, 2019a). As the COVID-19 pandemic illuminated both the need for telehealth services, including technology-assisted mental health treatment, and the disparities in access to these services, there is greater attention to building infrastructure to make broadband more widely available in rural and other underserved areas. Additionally, there is continued advocacy around digital inclusion efforts, including making the internet a public utility (Rahman, 2018). Therefore, it seems there is strong potential for growth in the implementation and utilization of T-CBT programs, like ROST, to increase depression treatment access in rural settings.

Finally, ROST pilot participants were, on average, 65 years old, and engaged with technology very well, as evidenced by their session attendance. The strong engagement of these older adults in ROST is counter to some literature suggesting that older adults may not find technology-assisted treatment acceptable (Crabb et al., 2012; Xiang et al., 2020). It may be that the group-based, virtual delivery format encouraged engagement, especially during COVID-19 when many individuals were socially isolated. Further, the facilitator-led format may have supported engagement among older adults. The facilitator accessed the ROST program and shared their screen to deliver technology-assisted content to group members. Therefore, older adults only had to utilize technology to access videoconferencing software and did not have to figure out how to use the ROST program on their own. Further research on ROST acceptability and accessibility among rural older adults is warranted to better understand factors driving their engagement.

This pilot study has limitations that must be considered. First, the study’s small sample of nine participants is a limitation. Although results suggesting ROST significantly reduced depressive symptoms and anxiety are promising, they must be interpreted with caution, considering the small sample size. It is critical to test ROST with larger samples. Second, the single group pre-/post-test design does not allow for the comparison of ROST with a control condition or another active treatment. Therefore, we can only draw tentative, preliminary conclusions from our results. A Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) of ROST is needed to fully understand the intervention’s effect on depressive symptoms and anxiety, compared to a control condition. Third, this pilot study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, and we do not know the impact of that context on study findings. For example, participants may have been more open to participating in ROST because of experiencing pandemic-related stress and depression. It also may be that the social isolation and inability to do other things led to increased treatment engagement among ROST pilot participants. Finally, the majority of the pilot sample (88.9%) reported being affiliated with a church; although only two participants (22.2%) were affiliated with a church led by one of our group leaders. We do not know if this program is acceptable to rural individuals who are not affiliated with churches. It may be that rural residents not affiliated with a church would not be as open to an intervention program facilitated by clergy.

These limitations notwithstanding, findings from this pilot study suggest the importance of offering treatment that is relevant to the experiences of rural residents, leveraging technology in acceptable ways, and building community capacity to deliver evidence-based depression treatment in settings where rural residents typically go for help, like the church. Rural mental health treatment access disparities have persisted for decades and addressing these disparities is a social justice imperative. It is critical for social work researchers and practitioners to collaborate with rural communities to identify solutions for addressing unacceptable depression treatment access disparities. This pilot study utilized a community-engaged approach to tailor and pilot test ROST, an innovative, entertaining, T-CBT for depression, for the rural context and for delivery by clergy. Results suggest that ROST is likely effective for treating depression among rural adults and acceptable to this population, given the high level of treatment attendance. Further, findings demonstrate clergy’s ability to competently deliver the evidence-supported treatment via a technology-assisted platform. Results from this pilot study show promise for ROST as an effective, feasible, and acceptable depression treatment model in underserved, rural settings. Future research testing ROST with larger samples and via a randomized controlled trial is necessary and warranted.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health [K01MH110605].

Footnotes

Author’s Note

We have no known conflicts of interest to disclose. The views expressed in the article are those of the authors and do not represent the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Amundson B (2001). America’s rural communities as crucibles for clinical reform: establishing collaborative care teams in rural communities. Families, Systems, and Health, 19, 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G, Basu A, Cuijpers P, Craske MG, McEvoy P, English CL, & Newby JM (2018). Computer therapy for the anxiety and depression disorders is effective, acceptable and practical health care: an updated meta-analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 55, 70–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G, Cuijpers P, Craske MG, McEvoy P, & Titov N (2010). Computer therapy for the anxiety and depressive disorders is effective, acceptable and practical health care: a meta-analysis. Plos One, 5, e13196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayers CR, Sorrell JT, Thorp SR, & Wetherell JL (2007). Evidence-based psychological treatments for late-life anxiety. Psychology and Aging, 22, 8–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M Jr, Castro FG, Strycker LA, & Toobert DJ (2013). Cultural adaptations of behavioral health interventions: a progress report. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81, 196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazer DG, Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, & Swartz MS (1994). The prevalence and distribution of major depression in a national community sample: the national comorbidity survey. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 151, 979–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun B, & Maghri JR (2004). Rural families speak: Faith, resiliency, & life satisfaction among low-income mothers. Michigan Family Review, 8, 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Brody DJ, Pratt LA, & Hughes J (2018). Prevalence of depression among adults aged 20 and over: United States, 2013-2016. NCHS data brief, no 303. National Center for Health Statistics. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckwalter KC (1991). The chronically mentally ill elderly in rural environments. In Lebowitz E, & Light E (Eds.), The elderly with chronic mental illness (pp. 216–231). Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Butler AC, Chapman JE, Forman EM, & Beck AT (2006). The empirical status of cognitive-behavior therapy: a review of meta-analyses. Clinical Psychology Review, 26, 17–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callahan CM, Unverzagt FW, Hui SL, Perkins AJ, & Hendrie HC (2002). Six-item screener to identify cognitive impairment among potential subjects for clinical research. Medical care. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalfant HP, Heller PL, Roberts A, Briones D, Aguiree-Hochbaum S, & Farr W (1990). The clergy as a resource for those encountering psychological distress. Review of Religious Research, 31, 305–313. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler AA, & Campbell CD (2002). Barricades to benefits: Religion as a rural woman’s resource. Graduate School of Clinical Psychology, George Fox University. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper H, Hedges LV, & Valentine JC (Eds.), (2019). The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis. Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Crabb RM, Cavanagh K, Proudfoot J, Learmonth D, Rafie S, & Weingardt KR (2012). Is computerized cognitive-behavioural therapy a treatment option for depression in late-life? a systematic review. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 51, 459–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowther MR, Scogin F, & Johnson Norton M (2010). Treating the aged in rural communities: the application of cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression. Journal of clinical psychology, 66, 502–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crumb L, Mingo TM, & Crowe A (2019). “Get over it and move on”: the impact of mental illness stigma in rural, low-income United States populations. Mental Health and Prevention, 13, 143–148. [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P, Noma H, Karyotaki E, Cipriani A, & Furukawa TA (2019). Effectiveness and acceptability of cognitive behavioral therapy delivery formats in adults with depression: a network meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 76, 700–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czeisler MÉ, Lane RI, Petrosky E, Wiley JF, Christensen A, Njai R, & Rajaratnam SM (2020). Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, June 24–30, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69, 1049–1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlstrom MF (2014). Using narratives and storytelling to communicate science with nonexpert audiences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(4), 13614–13620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dear BF, Zou J, Titov N, Lorian C, Johnston L, Spence J, & Knight RG (2013). Internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy for depression: a feasibility open trial for older adults. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 47, 169–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service (2017). Geography of poverty. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/rural-economy-population/rural-poverty-well-being/geography-of-poverty.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Ebert DD, Zarski AC, Christensen H, Stikkelbroek Y, Cuijpers P, Berking M, & Riper H (2015). Internet and computer-based cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression in youth: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled outcome trials. Plos One, 10, e0119895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis AR, Konrad TR, Thomas KC, & Morrissey JP (2009). County-level estimates of mental health professional supply in the United States. Psychiatric Services, 60, 1315–1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez E, Salem D, Swift JK, & Ramtahal N (2015). Meta-analysis of dropout from cognitive behavioral therapy: magnitude, timing, and moderators. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83, 1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firth J, Torous J, Nicholas J, Carney R, Pratap A, Rosenbaum S, & Sarris J (2017). The efficacy of smartphone-based mental health interventions for depressive symptoms: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World Psychiatry, 16, 287–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer C (1982). To dwell among friends: Personal networks in town and city. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fortney JC, Harman JS, Xu S, & Dong F (2010). The association between rural residence and the use, type, and quality of depression care. Journal of Rural Health, 26, 205–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox JC, Blank M, Rovnyak VG, & Barnett RY (2001). Barriers to help seeking for mental disorders in a rural impoverished population. Community Mental Health Journal, 37, 421–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox JC, Merwin EI, & Blank M (1995). De facto mental health services in the rural south. Journal of Healthcare of the Poor and Underserved, 64, 434–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich MJ (2017). Depression is the leading cause of disability around the world. JAMA, 317, 1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjesfjeld CD, Weaver A, & Schommer K (2012). Rural women’s transitions to motherhood: understanding social support in a rural community. Journal of Family Social Work, 15, 435–448. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg PE, Fournier AA, Sisitsky T, Pike CT, & Kessler RC (2015). The economic burden of adults with major depressive disorder in the United States (2005 and 2010). The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 76(2), 155–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankerson SH, & Weissman MM (2012). Church-based health programs for mental disorders among African Americans: a Review. Psychiatric Services, 63, 243–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley D, Bird D, & Dempsey P (1999). Mental health and substance abuse. In Ricketts T (Ed.), Rural health in the United States. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Sarvet AL, Meyers JL, Saha TL, Ruan WJ, Stohl M, & Grant BF (2018). Epidemiology of adult DSM-5 major depressive disorder and its specifiers in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry, 75, 336–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauenstein EJ, & Peddada SD (2007). Prevalence of major depressive episodes in rural women using primary care. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 18, 185–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays K, & Aranda MP (2016). Faith-based mental health interventions with African Americans: a review. Research on Social Work Practice, 26, 777–789. [Google Scholar]

- Health Resources and Services Administration (2019). Designated health professional shortage areas. Bureau of Health Workforce. https://ersrs.hrsa.gov/ReportServer?/HGDW_Reports/BCD_HPSA/BCD_HPSA_SCR50_Smry_HTML&rc:Toolbar=false. [Google Scholar]

- Hill CE, & Fraser GJ (1995). Local knowledge and rural mental health reform. Community Mental Health Journal, 31, 553–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himle JA, Bybee D, Steinberger E, Laviolette WT, Weaver A, Vlnka S, & O’Donnell LA (2014). Work-related CBT versus vocational services as usual for unemployed persons with social anxiety disorder: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 63, 169–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himle JA, Weaver A, Zhang A, & Xiang X (2021) (In press). Digital mental health interventions for depression. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 10.1016/j.cbpra.2020.12.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG, Asnaani A, Vonk IJJ, Sawyer AT, & Fang A (2012). The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy: a review of meta-analyses. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 36, 427–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan MF (2003). The President’s new freedom commission: recommendations to transform mental health care in America. Psychiatric Services, 54, 1467–1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, & Wang PS (2003). The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National comorbidity survey replication (NCS-R). JAMA, 289, 3095–3105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, & Walters EE (2005). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 593–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen H-U, & Kendler KS (1994). Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the national comorbidity survey. Archives of General Psychiatry, 51, 8–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs P, Prochaska JO, & Rossi JS (2010). A meta-analysis of computer-tailored interventions for health behavior change. Preventive medicine, 51, 214–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, & Spitzer RL (2002). The PHQ-9: a new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatric Annals, 32, 509–515. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, & Williams JB (2001). The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16, 606–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, & Williams JB (2003). The patient health questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Medical Care, 41, 1284–1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Theng Y-L, & Foo S (2014). Game-based digital interventions for depression therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 17, 519–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan TK, Stevenson E, Evans L, & Leukefeld C (2004). Rural and urban women’s perceptions of barriers to health, mental health, and criminal justice services: implications for victim services. Violence and Victims, 19, 37–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo M, Guo L, Yu M, & Wang H (2020). The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public–a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry research, 291, 113190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marciniak MD, Lage MJ, Dunayevich E, Russell JM, Bowman L, Landbloom RP, & Levine LR (2005). The cost of treating anxiety: The medical and demographic correlates that impact total medical costs. Depression and Anxiety, 2, 178–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merwin E, Hinton I, Dembling B, & Stern S (2003). Shortages of rural mental health professionals. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 17, 42–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merwin E, Snyder A, & Katz E (2006). Differential access to quality rural healthcare: professional and policy challenges. Family and Community Health, 29, 186–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison LG (2015). Theory-based strategies for enhancing the impact and usage of digital health behaviour change interventions: a review. Digital Health, 1, 2055207615595335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mynatt S, Wicks M, & Bolden L (2008). Pilot study of insight therapy in African American women. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 22, 364–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Advisory Committee on Rural Health and Human Services (2014). Rural implications of the Affordable Care Act outreach, education, and enrollment (Policy brief). https://www.hrsa.gov/advisorycommittees/rural/publications/ruralimplications.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Newby JM, Twomey C, Li SSY, & Andrews G (2016). Transdiagnostic computerised cognitive behavioural therapy for depression and anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 199, 30–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newkirk V, & Damico A (2014). The Affordable Care Act and insurance coverage in rural areas. The Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. https://www.kff.org/uninsured/issue-brief/the-affordable-care-act-and-insurance-coverage-in-rural-areas/. [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM, Benac CN, & Harris MS (2007). Does tailoring matter? Meta-analytic review of tailored print health behavior change interventions. Psychological bulletin, 133, 673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, Blanco C, & Marcus SC (2016). Treatment of adult depression in the United States. JAMA Internal Medicine, 176, 1482–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center (2019a). Mobile fact Sheet. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/mobile/.

- Pew Research Center (2019b). Internet/broadband fact Sheet. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/internet-broadband/.

- Porter JF, Spates CR, & Smitham S (2004). Behavioral activation group therapy in public mental health settings: a pilot investigation. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 35, 297. [Google Scholar]

- Probst JE, Laditka SB, Moore CG, Harun N, Powell MP, & Baxley EG (2006). Rural-urban differences in depression prevalence: Implications for family medicine. Family Medicine, 38, 653–660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor BD, Semega JL, & Kollar MA (2016). Income and poverty in the United States: 2015 (current population reports). US Government Printing Office. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman KS (2018). Regulating informational infrastructure: internet platforms as the new public utilities. Georgetown Law and Technology Review, 2, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Rost K, Fortney J, Fischer E, & Smith J (2002). Use, quality, and outcomes of care for mental health: the rural perspective. Medical Care Research and Review: MCRR, 59, 231–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rost K, Smith GR, & Taylor JL (1993). Rural-urban differences in stigma and the use of care for depressive disorders. Journal of Rural Health, 9, 57–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy-Byrne PP, Craske MG, Stein MB, Sullivan G, Bystrisky A, Katon W, Golinelli D, & Sherbourne CD (2005). A randomized effectiveness trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy and medication for primary care panic disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 290–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy-Byrne P, Craske MG, Sullivan G, Rose RD, Edlund MJ, Lang AJ, …, & Stein MB (2010). Delivery of evidence-based treatment for multiple anxiety disorders in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 303, 1921–1928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin A, & Yu M (2017). Within-group effect size benchmarks for cognitive-behavioral therapy in the treatment of adult depression. Social Work Research, 41, 135–144. [Google Scholar]

- Salari N, Hosseinian-Far A, Jalali R, Vaisi-Raygani A, Rasoulpoor S, Mohammadi M, Rasoulpoor S, & Khaledi-Paveh B (2020). Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Globalization and Health, 16, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer D, Gale J, & Lambert D (2006). Rural and frontier mental and behavioral health care: Barriers, effective policy strategies, best practices. National Association for Rural Mental Health. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan D (2015). s. Mini international neuropsychiatric interview, 2014. version 7.0 s. https://harmresearch.org/index.php/product/mini-international-neuropsychiatric-interview-mini-7-0-2-4/. [Google Scholar]

- Sheffler MJ (1999). Culturally sensitive research methods of surveying rural/frontier residents. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 21, 426–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smalley KB, Yancey CT, Warren JC, Naufel K, Ryan R, & Pugh JL (2010). Rural mental health and psychological treatment: a review for practitioners. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 66, 479–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, & Löwe B (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Archives of internal medicine, 166, 1092–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twomey C, O’Reilly G, & Meyer B (2017). Effectiveness of an individually-tailored computerised CBT programme (Deprexis) for depression: a meta-analysis. Psychiatry research, 256, 371–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ballegooijen W, Cuijpers P, Van Straten A, Karyotaki E, Andersson G, Smit JH, & Riper H (2014). Adherence to Internet-based and face-to-face cognitive behavioural therapy for depression: a meta-analysis. Plos One, 9(7), e100674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller R, & Gilbody S (2009). Barriers to the uptake of computerized cognitive behavioural therapy: a systematic review of the quantitative and qualitative evidence. Psychological medicine, 39, 705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JL (2004). Rural-urban differences in the prevalence of major depression and associated impairment. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 39, 19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PS, Berglund PA, & Kessler RC (2003a). Patterns and correlates of contacting clergy for mental disorders in the United States. Health Services Research, 38, 647–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PS, Simon G, & Kessler RC (2003b). The economic burden of depression and the cost-effectiveness of treatment. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 12, 22–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PS, Demler O, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, & Kessler RC (2006). Changing profiles of service sectors used for mental health care in the United States. American Journal of Psychiatry, 163, 1187–1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, & Kessler RC (2005). Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the national comorbidity survey replication. Archives of Gen Psychiatry, 62, 629–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver AJ (1995). Has there been a failure to prepare and support parish-based clergy in their roles as front-line community mental health workers? a review. The Journal of Pastoral Care, 49, 129–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver A, Hahn J, Tucker KM, Bybee D, Yugo K, Johnson JM, & Himle JA (2020). Depressive symptoms, material hardship, barriers to help-seeking, and receptivity to church-based care among recipients of food bank services in rural Michigan. Social Work in Mental Health, 5, 515–535. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver A, & Himle JA (2017). Cognitive–behavioral therapy for depression and anxiety disorders in rural settings: a review of the literature. Journal of Rural Mental Health, 41, 189. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver A, Himle J, Elliott M, Hahn J, & Bybee D (2019). Rural residents’ depressive symptoms and help-seeking preferences: Opportunities for church-based intervention development. Journal of Religion and Health, 58, 1661–1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver A, Zhang A, Xiang X, Felsman P, Fisher DJ, & Himle JA (in press). Entertain me well: an entertaining, tailorable, online platform for delivering depression treatment. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson CJ, & Cottone RR (2013). Using cognitive behavior therapy in clinical work with African American children and adolescents: a review of the literature. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 41, 130–143. [Google Scholar]

- Wright JH, Owen JJ, Richards D, Eells TD, Richardson T, Brown GK, & Thase ME (2019). Computer-assisted cognitive-behavior therapy for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 80, 18r12188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang X, Wu S, Zuverink A, Tomasino KN, An R, & Himle JA (2020). Internet-delivered cognitive behavioral therapies for late-life depressive symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging & Mental Health, 24, 1196–1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young J, &, & Beck AT (1980). Cognitive therapy scale: Rating manual. unpublished manuscript. https://centralizedtraining.com/resources/Cognitive%20Behavioral%20Treatment%20(CBT)/CTRS%20manual.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang A, Bornheimer LA, Weaver A, Franklin C, Hai AH, Guz S, & Shen L (2019). Cognitive behavioral therapy for primary care depression and anxiety: a secondary meta-analytic review using robust variance estimation in meta-regression. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 42, 1117–1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]