Abstract

Multilocus enzyme electrophoresis, partial 23S rRNA sequences, and nearly full-length 16S rRNA sequences all indicated high genetic similarity among root-nodule bacteria associated with Apios americana, Desmodium glutinosum, and Amphicarpaea bracteata, three common herbaceous legumes whose native geographic ranges in eastern North America overlap extensively. A total of 19 distinct multilocus genotypes (electrophoretic types [ETs]) were found among the 35 A. americana and 33 D. glutinosum isolates analyzed. Twelve of these ETs (representing 78% of all isolates) were either identical to ETs previously observed in A. bracteata populations, or differed at only one locus. Within both 23S and 16S rRNA genes, several isolates from A. americana and D. glutinosum were either identical to A. bracteata isolates or showed only single nucleotide differences. Growth rates and nitrogenase activities of A. bracteata plants inoculated with isolates from D. glutinosum were equivalent to levels found with native A. bracteata bacterial isolates, but none of the three A. americana isolates tested had high symbiotic effectiveness on A. bracteata. Phylogenetic analysis of both 23S and 16S rRNA sequences indicated that both A. americana and D. glutinosum harbored rare bacterial genotypes similar to Bradyrhizobium japonicum USDA 110. However, the predominant root nodule bacteria on both legumes were closely related to Bradyrhizobium elkanii.

In recent years, much progress has been made in clarifying the phylogenetic affinities of root nodule bacteria from various taxa of host legumes (1, 6, 8, 9, 13, 14, 28–30, 32, 33). However, the precise relationships of symbiotic bacteria from the vast majority of legume species in natural plant communities remain quite poorly known. Moreover, there is a particular need for studies of bacteria from different legumes that coexist regionally (8), to understand patterns of host specificity and the potential for ecological linkages among legume taxa that may arise from overlap in bacterial symbiont utilization.

In this study, I analyze the extent to which Bradyrhizobium sp. symbionts are shared by three common papilionoid legumes indigenous to eastern North America: Amphicarpaea bracteata, Apios americana, and Desmodium glutinosum. Past studies of bacteria associated with A. bracteata provide a provisional framework for understanding diversity and relationships. Analyses of partial nod, 16S rRNA, and 23S rRNA sequences show that bacteria associated with A. bracteata form a monophyletic group related to Bradyrhizobium elkanii (25). However, multilocus enzyme electrophoresis (MLEE) (21) of 270 isolates sampled from a 1,000-km region indicated that the bacterial associates of A. bracteata are fairly diverse. Three basic lineages (designated A, B, and C) exist that differ at >50% of the enzyme loci surveyed (17), with all three lineages present in each geographic area sampled. These bacterial lineages are heterogeneous in nodulation specificity toward different A. bracteata genotypes. All lineage C isolates display unspecialized symbiotic phenotypes, forming nodules on all A. bracteata genotypes tested. By contrast, most lineage A isolates are specialized on one host subgroup (termed plant lineage Ia and defined by isozyme markers) and form few or no nodules on other A. bracteata genotypes (19). Lineage B isolates are heterogeneous: some display specialized phenotypes identical to lineage A bacteria and some are effective, broad host-range symbionts (like lineage C isolates). Other lineage B isolates form nodules on all A. bracteata genotypes yet are completely ineffective with respect to nitrogen fixation (35).

Since many root nodule bacteria have host ranges that naturally encompass several legume genera (for examples, see references 37 and 39), it is unlikely that the diverse bacteria found in A. bracteata populations all evolved strictly in association with this plant. The goal of the present study was therefore to survey bacteria from two related legumes that sometimes cooccur with A. bracteata, to determine the extent to which bacterial genotypes are shared across host taxa. Bacteria were sampled from A. americana, a perennial vine in the subtribe Erythrininae of the tribe Phaseoleae, and from D. glutinosum, a herbaceous perennial in the tribe Desmodieae (for brevity, I hereafter refer to the three host taxa by their generic names only). Amphicarpaea is a herbaceous annual vine in the Phaseoleae subtribe Glycininae (4). While traditional classifications have placed Desmodium in a separate tribe from the other two genera, phylogenetic analyses of chloroplast DNA sequences have shown that Desmodium is actually more closely related to certain legumes in the subtribes Erythrininae and Glycininae that these are to other subtribes within the Phaseoleae (5). In addition, the results of cross-inoculation experiments published 60 years ago showed that certain bacterial isolates from Apios and Desmodium can form nodules on Amphicarpaea and that bacteria from Amphicarpaea and Apios can nodulate some species of Desmodium (37). However, since these studies provided no information about the genetic relationships of the bacteria tested or about their capacity for nitrogen fixation, it is important to reanalyze the root nodule bacteria associated with these legume taxa.

This study addressed three specific questions. First, using MLEE, is there evidence that isolates from Apios or Desmodium are related to those previously detected in Amphicarpaea populations (17)? Second, do bacterial isolates from the three legume taxa display similar length variants and nucleotide sequences in the 5′ portion of the 23S rRNA gene (22) and in 16S rRNA? Finally, can bacteria that are associated with Apios and Desmodium function as effective nitrogen-fixing symbionts on Amphicarpaea plants, as evidenced by plant growth and nodule nitrogenase activity?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolate sampling.

Root nodule bacteria were collected from one Apios and one Desmodium population both in Broome County and in Tompkins County, New York (Table 1). The Apios and Desmodium sites in Tompkins County were 0.8 km apart in the Fall Creek watershed, while the two Broome County sites were 18 km apart. Approximately 65 km separated the Broome County and Tompkins County sites. These four sample sites were chosen because they are each within 2 km of A. bracteata populations where bradyrhizobial diversity had previously been analyzed (17). At each site, 15 to 18 nodules were sampled haphazardly (each from a different individual plant), and a single bacterial isolate was purified from each nodule as previously described (24).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study

| Strain | Host | Origin | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|---|

| DesB1–DesB15 | D. glutinosum | Broome Co., N.Y. | This study |

| DesT1–DesT18 | D. glutinosum | Tompkins Co., N.Y. | This study |

| ApB1–ApB18 | A. americana | Broome Co., N.Y. | This study |

| ApT1–ApT17 | A. americana | Tompkins Co., N.Y. | This study |

| jwc91-2 (lineage A) | A. bracteata | Cook Co., Ill. | 24 |

| bfs1b (lineage B) | A. bracteata | Cook Co., Ill. | 17 |

| th-b2 (lineage C) | A. bracteata | Broome Co., N.Y. | 17 |

| B. japonicum USDA 110 | Glycine max | United States | L. D. Kuykendall |

| B. elkanii USDA 94 | G. max | United States | L. D. Kuykendall |

Enzyme electrophoresis.

Bacterial isolates were grown in yeast-mannitol broth (31), and enzymes were obtained from sonicated cells (24). Isolates were characterized by starch gel electrophoresis at the following 20 enzyme loci as previously described (24): acid phosphatase (ACP), alanine dehydrogenase (ALA), butyrate esterase (EST), β-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase (HBD), diaphorase (DIA), fumarase (FUM), fructose-1,6-diphosphatase (F16), glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G-6), glutamic-oxalacetic transaminase (GOT), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase type 1 (GP1), isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH), indophenol oxidase (IPO), leucine aminopeptidase (LAP), leucine tyrosine peptidase (PEP), malate dehydrogenase (MDH), malic enzyme (ME), phosphoglucose isomerase (PGI), phosphoglucomutase (PGM), 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase (6PGD), and shikimate dehydrogenase (SDH). Each isolate was characterized by its allelic profile for the 20 enzymes, and each unique multilocus genotype was designated an electrophoretic type (ET). On each gel, two different standards representing ETs from Amphicarpaea were included with the Apios and Desmodium isolates. Two loci were monomorphic across all isolates (IPO and MDH) and were therefore omitted from the allele profile summary (Table 2). Pairwise genetic distances between ETs were estimated by the proportion of enzyme loci at which allelic differences occurred. ETs were then clustered by the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic means (23).

TABLE 2.

Allele profiles at 18 enzyme loci in 19 ETs of Bradyrhizobium isolates from Apios and Desmodium

| Allele at indicated enzyme locusa

|

No. of isolates from population

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ET | ACP | ALA | DIA | EST | F16 | FUM | G-6 | GOT | GP1 | HBD | IDH | LAP | PEP | ME | PGI | PGM | 6PGD | SDH | DesB | DesT | ApB | ApT |

| 1 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 13 | |||

| 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 13 | ||

| 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 1 | |||

| 4 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 1 | |||

| 5 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 1 | |||

| 6 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 1 | |||

| 7 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 6 | 2 | |||

| 8 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 1 | ||

| 9 | 9 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 2 | |||

| 10 | 9 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 2 | |||

| 11 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 1 | |||

| 12 | 8 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 8 | |||

| 13 | 8 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | |||

| 14 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 3 | |||

| 15 | 8 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 1 | |||

| 16 | 8 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | |||

| 17 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |||

| 18 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||

| 19 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

Alleles are listed by relative anodal migration speed (1 = fastest; null alleles are depicted by 0).

DNA amplification and sequencing.

DNA was purified from five Desmodium isolates and four Apios isolates by a cetyltrimethylammonium bromide protocol (38). For reference, Bradyrhizobium japonicum USDA 110, B. elkanii USDA 94, and Amphicarpaea isolate jwc91-2 (lineage A) were also analyzed. A 5′ portion of 23S rRNA that is highly polymorphic within the Rhizobiaceae (22) was amplified with primers 23Sup115 and 23SrIII (25). These primers yield a 260-bp DNA fragment in B. japonicum USDA 110 (GenBank accession no. Z35330). For five selected isolates, a larger segment of DNA spanning this region was then sequenced on both strands, beginning 62 sites from the 5′ end of the 23S rRNA gene using primers 23Sup6n and 23SrII (25) (these amplify 496 bp in B. japonicum USDA 110). For five isolates, nearly full-length 16S rRNA was amplified using primers fD1d (5′-GAGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAGA) and rPla (5′-CTACGGCTACCTTGTTACGACTT). This fragment was sequenced on both strands using the following internal sequencing primers (numbers in brackets indicate primer position relative to the Escherichia coli rrnB gene [2]): m5if (5′-CATGCCGCGTGAGTGATGAAGG [bp 395 to 416]), 5v2ir (5′-AAAGAGCTTTACAACCCTA [bp 420 to 438]), 16smidf (bp 774 to 795) (25), al4r (5′-GAGTTTTAATCTTGCGACCGTA [bp 890 to 911]), 16cup (5′-TCGTGTCGTGAGATGTTGGGTTA [bp 1,069 to 1,091]), and m3ir (5′-GACTTGACGTCATCCCCACCTT [bp 1,178 to 1,199]).

PCR used 25-μl reaction mixtures containing 10 mM Tris buffer with 0.1% Triton X-100, 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM concentrations of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 0.5 μM concentrations of each primer, 0.5 μl of genomic DNA, and 0.5 U of Taq polymerase. Tubes were incubated for 70 s at 94° and then subjected to 35 cycles of 94° (20 s), 58° (50 s), and 72° (50 s), with a final extension of 4 min at 72°. Five microliters of PCR product was run on a 1.9% agarose gel with a DNA size standard to analyze length variation. PCR-amplified DNA was sequenced using an Applied Biosystems Model 310 automated sequencing system with dye terminator chemistry, following protocols recommended by the manufacturer.

Phylogenetic analyses.

Trees were constructed by maximum parsimony using the PAUP software, version 4.0b1 (D. L. Swofford, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.). To determine the degree of statistical support for branches in the phylogeny (7), 1,000 bootstrap replicates of each data set were analyzed. For the 23S rRNA region, data from Apios and Desmodium isolates were compared to reference sequences available for B. japonicum USDA 110, Bradyrhizobium sp. (Lupinus) strain DSM 30140 (X87283), B. elkanii USDA 94 (AF081266), and Bradyrhizobium sp. (Amphicarpaea) strains jwc91-2, bfs1b, and th-b2, representing MLEE lineages A, B and C, respectively (AF081262, AF081263, and AF081265). Rhodopseudomonas palustris (X71839) was used as the outgroup (25). For 16S rRNA, data from Apios, Desmodium, and Amphicarpaea isolates were compared to the following Bradyrhizobium reference sequences (strains without formal names are identified by host legume genus in parentheses): B. japonicum strains USDA 6 (GenBank accession no. U69638) and USDA 110 (Z35330), strain DSM 30140 (Lupinus) (X87273), B. elkanii strains USDA 76 (U35000) and USDA 94 (D13429), strain 129 (Stylosanthes) (D14508) (14), Bradyrhizobium genomic species B (Bossiaea) (Z94812) (8), LMG 9966 (Acacia) (X70403) (6). Several related genera of the alpha subgroup of the class Proteobacteria were also included in the analysis: Azorhizobium caulinodans (X67221), Paracoccus denitrificans (X69159), Rhodobacter sphaeroides (D16424), and R. palustris (D25312). A. caulinodans was chosen as the outgroup (6, 36, 40).

Sequences were first aligned using CLUSTAL W (27), which revealed that three single-nucleotide insertion-deletion polymorphisms (indels), together with two longer gaps of 12 and 16 bp, existed in the 23S rRNA region. Several small indels (1 to 3 bp) were also evident in the aligned 16S rRNA sequence. Since specific indels were commonly shared across taxa and appeared to provide useful information about relationships, gaps were included in the phylogenetic analysis by using the “gapmode = newstate” option in PAUP. However, to avoid counting large gaps as multiple independent characters, all but the first position within the two long 23S rRNA gaps were recoded as missing data. This weighted each gap as a single event regardless of its length.

Plant growth rate and nitrogenase activity.

Three Apios and four Desmodium isolates representing different genotypes revealed by MLEE and rRNA sequence analyses were used to inoculate Amphicarpaea plants according to previously described procedures (35). Two lineage A isolates (DesT1 and ApT2, representing ET1 and ET2, respectively), two lineage B isolates (ApB2 and ApB5, representing ET8 and ET10), two lineage C isolates (DesB1 and DesB3, representing ET13 and ET12), and the sole lineage E isolate (DesT10, representing ET19) were tested. Two lineages of Amphicarpaea plants were inoculated with each isolate: plants from a lineage Ia population in Tompkins County, N.Y., and plants from a lineage Ib population in Broome County, N.Y. (15). These Amphicarpaea populations are close to two of the collection locations for the bacterial isolates. It was not possible to perform reciprocal inoculations to test how plants of Apios and Desmodium interacted with bacterial isolates from Amphicarpaea due to a lack of seeds from these taxa (natural populations of D. glutinosum commonly have low seed productivity, and A. americana populations in this region are sterile triploids [3]).

Amphicarpaea seedlings were germinated under aseptic conditions and then planted individually in 240-cm3 containers using a Bradyrhizobium-free mixture of sand, perlite, and potting soil. For each bacterial isolate, 12 seedlings of each plant lineage were inoculated with approximately 109 cells grown in yeast-mannitol broth (31). Plants were grown in a greenhouse for 48 days with precautions to avoid bacterial contamination across inoculation treatments (35). Twelve uninoculated controls of each plant lineage were grown simultaneously in the same room as contamination checks. No nodules developed on any of these plants. To compare Apios and Desmodium isolates with bacteria endemic to Amphicarpaea populations, 12 plants per lineage were also inoculated with a Bradyrhizobium strain native to the lineage Ib A. bracteata population used in the experiment (th-b2) (Table 1). Starting 14 days after inoculation, all plants were fertilized weekly with a nitrogen-free nutrient solution (18). At harvest, total plant dry mass and nodule numbers were recorded for each plant, and a subsample of two to three plants from each group was analyzed for acetylene reduction activity using a Hewlett Packard 5890 Series II gas chromatograph as described (24).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The five distinct 23S rRNA sequences found among Desmodium and Apios isolates have been placed in GenBank under accession no. AF146820 through AF146824. The five nearly full-length 16S rRNA sequences obtained have been assigned accession no. AF178434 through AF178438, and the partial 16S rRNA sequence from isolate DesT10 has been assigned accession no. AF146827.

RESULTS

Diversity and relationships inferred from MLEE.

Among the 68 isolates sampled from Apios and Desmodium, variation was detected at 18 of the 20 enzyme loci examined, with a mean of 4.4 alleles per polymorphic locus (range, two to nine alleles) (Table 2). A total of 19 distinct multilocus genotypes (ETs) were detected. Most ETs were recovered more than once among different isolates from the same population. However, only two ETs (ET2 and ET8) occurred in more than one population (Table 2). These ETs were found in both Apios populations sampled and represented 71% of all isolates obtained from that host. No ETs were shared by Apios and Desmodium populations, nor were any ETs shared by the two Desmodium populations sampled.

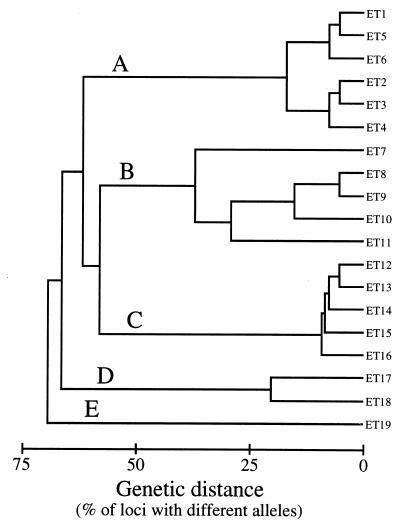

An average linkage cluster analysis revealed the presence of five divergent bacterial lineages (designated A through E) (Fig. 1). These differed at 57 to 69% of the 20 enzyme loci analyzed. All Apios isolates fell into lineages A, B, and D. One Desmodium population (DesB) contained only ETs in lineage C. The other Desmodium population was dominated by lineage A, but also had one isolate each from lineages B and E.

FIG. 1.

Genetic relationships among 19 multilocus genotypes (ETs) of Bradyrhizobium isolated from Apios and Desmodium.

Most of the ETs detected in Apios and Desmodium populations (Table 2 and Fig. 1) were strongly similar to bacterial genotypes associated with Amphicarpaea. In an isozyme survey of 270 Bradyrhizobium isolates from 24 Amphicarpaea populations (17), all bacteria were found to cluster into three groups that corresponded exactly to lineages A, B, and C of Fig. 1, and numerous isolates from the three host taxa had identical multilocus genotypes. For example, the two most common ETs in lineage A of Fig. 1 (ET1 and ET2) were indistinguishable from the two most common ETs in this lineage among bacteria associated with Amphicarpaea (17). The four most common lineage C ETs in Amphicarpaea populations were identical to ET12, ET13, ET14, and ET16 of Fig. 1. The five lineage B ETs from Apios and Desmodium did not match any Amphicarpaea ETs. However, ET10 differed at only one locus from an Amphicarpaea isolate, and ET7 and ET9 also matched lineage B Amphicarpaea ETs at all but two loci. Overall, 6 of the 19 Apios and Desmodium ETs (representing 68% of all isolates) were identical to ETs detected in Amphicarpaea populations, and another six ETs (representing an additional 10% of isolates) differed at only one locus from corresponding Amphicarpaea ETs.

At a finer scale, bacteria from the two Desmodium sites each showed a striking resemblance to those in nearby Amphicarpaea populations. DesB had ETs only from bacterial lineage C, while DesT was dominated by bacterial lineage A (Table 2 and Fig. 1). The nearest Amphicarpaea population to DesB was 40 m away, and it was exclusively occupied by bacteria clustered into lineage C (17). The DesT population was 1.2 km from an Amphicarpaea site where 90% of the bacteria fell into lineage A and 10% grouped into lineage B (17). Thus, within each host legume species, populations in these two areas had no ETs in common. However, bacteria from the Desmodium population at each site overlapped extensively with those in the nearby Amphicarpaea population. A quantitative index of similarity can be defined by PS = Σ min(piv, pjv), where piv = the frequency of ET v in population i (20). Proportional similarity ranges from zero (when no ETs are shared in common) to one (when two populations have the same ETs at exactly the same frequency). Adjacent Desmodium-Amphicarpaea population pairs had PS values of 0.6 to 0.7, while PS values of bacterial populations within each host species were zero.

23S rRNA variation.

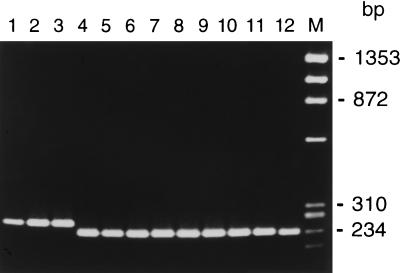

Bacterial lineages D and E (Fig. 1) were uncommon in the Apios and Desmodium samples, and no bacteria resembling these groups have been detected among 270 isolates from Amphicarpaea populations (17). To further characterize the relationships of these divergent genotypes, primers flanking a region in the 5′ portion of 23S rRNA that commonly shows length variation among taxa of Rhizobiaceae (22) were used to amplify DNA from representative isolates (Fig. 2). The lineage D and E isolates (Fig. 2, lanes 2 and 3) both displayed a single band approximately identical in size to that of B. japonicum USDA 110 (lane 1). By contrast, all of the lineage A, B, and C isolates from Apios and Desmodium (lanes 5 to 11) had smaller fragments matching those seen in Amphicarpaea lineage A (lane 4) and B. elkanii USDA 94 (lane 12) isolates.

FIG. 2.

PCR amplification products from a 5′ segment of 23S rRNA. Lane 1, B. japonicum USDA 110; lane 2, DesT10; lane 3, ApB16; lane 4, Bradyrhizobium sp. (Amphicarpaea) isolate jwc91-2; lane 5, DesT1; lane 6, ApT2; lane 7, ApB2; lane 8, ApB5; lane 9, DesB1; lane 10, DesB2; lane 11, DesB3; lane 12, B. elkanii USDA 94. Marker at right is HaeIII-digested φX174 DNA.

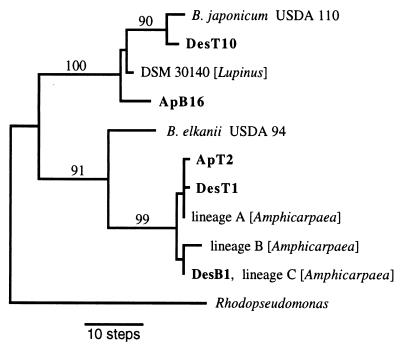

A larger portion of 23S rRNA spanning this region was sequenced in two lineage A isolates (DesT1 and ApT2), one lineage C isolate (DesB1), one lineage D isolate (ApB16), and the sole lineage E isolate (DesT10). This confirmed that the 5′ 23S rRNA regions of the lineage D and E isolates were identical in length and that the lineage A and C isolates had a 27-bp-shorter variant that matched the size of Amphicarpaea lineage A, B, and C isolates documented previously (25). The Desmodium and Apios lineage A isolates each differed from the sequence of Amphicarpaea lineage A isolates at only one nucleotide position and showed two nucleotide differences relative to each other. The lineage C isolate from Desmodium had a sequence which was identical to those of several Amphicarpaea lineage C isolates. The lineage D and E isolates both showed a number of substitutions relative to other published Bradyrhizobium 23S rRNA sequences. Parsimony analysis (Fig. 3) suggested a relationship between the lineage E isolate (Des10) and B. japonicum USDA 110. The lineage D isolate (ApB16) represented a more basally branching member of a clade including both B. japonicum USDA 110 and an isolate from Lupinus (11).

FIG. 3.

Parsimony tree for five partial 23S rRNA sequences from Desmodium and Apios (shown in bold). Numbers above branches are bootstrap percentages (n = 1,000 replicates). GenBank accession no.: B. japonicum USDA 110, Z35330; DesT10, AF146823; Bradyrhizobium sp. (Lupinus) strain DSM 30140, X87283; ApB16, AF146824; B. elkanii USDA 94, AF081266; ApT2, AF146821; DesT1, AF146820; Amphicarpaea lineage A (strain jwc91-2), AF081262; Amphicarpaea lineage B (strain bfs1b), AF081263; DesB1, AF146822; Amphicarpaea lineage C (strain th-b2), AF081265; and R. palustris, X71839.

16S rRNA variation.

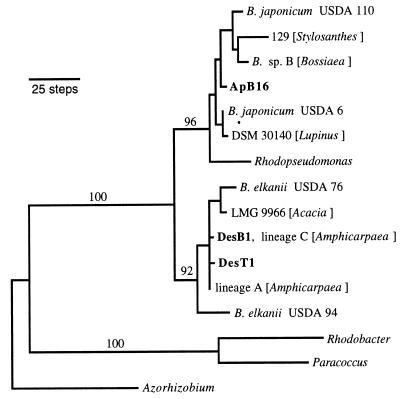

Nearly full-length sequences were obtained for isolates DesT1 (lineage A [ET1]), DesB1 (lineage C [ET13]), ApB16 (lineage D [ET17]), and Bradyrhizobium sp. (Amphicarpaea) strains jwc91-2 and th-b2 (representing isozyme lineages A and C, respectively). The lineage C isolates from Amphicarpaea and Desmodium were identical at all 1,412 bp sequenced. Both lineage A isolates shared a single nucleotide substitution relative to this lineage C 16S rRNA sequence, and DesT1 differed at one additional site from the other lineage A and C isolates. By contrast, ApB16 differed from the other isolates at 37 to 39 positions.

A parsimony tree indicated that these taxa of Bradyrhizobium fell into two distinct clades each with relatively high bootstrap support (Fig. 4). Isolate ApB16 had a clear relationship to the lineage that included B. japonicum. The other Bradyrhizobium clade encompassed a set of isolates related to B. elkanii. Desmodium isolates from MLEE lineages A and C clustered with this group, as did the Amphicarpaea isolates.

FIG. 4.

Phylogenetic relationships of three Bradyrhizobium isolates from Desmodium and Apios (shown in bold) based on parsimony analysis of 16S rRNA sequences. Numbers above branches are bootstrap percentages (n = 1,000 replicates). GenBank accession no.: B. japonicum USDA 110, Z35330; strain 129 (Stylosanthes), D14508; Bradyrhizobium genomic species B (Bossiaea), Z94812; ApB16, AF178434; B. japonicum USDA 6, U69638; DSM 30140 (Lupinus), X87273; R. palustris, D25312; B. elkanii USDA 76, U35000; LMG 9966 (Acacia) X70403; DesB1, AF178436; lineage C (Amphicarpaea), AF178438; DesT1, AF178435; lineage A (Amphicarpaea), AF178437; B. elkanii USDA 94, D13429; R. sphaeroides, D16424; P. denitrificans, X69159; and A. caulinodans, X67221.

A partial 16S rRNA sequence (383 bp, homologous to positions 795 to 1177 of the E. coli rrnB gene [2]) was also obtained for the sole lineage E from Desmodium (DesT10). This sequence was identical to that of B. japonicum USDA 6 and matched ApB16 at all but two sites. Therefore, this isolate also appears to be a member of the B. japonicum clade.

Symbiotic performance of Amphicarpaea with Apios and Desmodium bacteria.

Two representative isolates from lineages A, B, and C, and the sole lineage E isolate (Fig. 1) were used to inoculate Amphicarpaea plants. Because this legume is polymorphic at a locus that controls nodulation specificity, two plant genotypes were tested. Lineage Ia plants are homozygous for a recessive allele that allows nodulation with lineage A bacteria, while lineage Ib plants have a dominant gene that almost completely prevents nodule formation with the lineage A bacteria found in many Amphicarpaea populations (19).

Nodules developed abundantly on most Amphicarpaea plants inoculated with isolates from Apios and Desmodium. Lineage Ib plants inoculated with the lineage A isolate DesT1 mostly lacked nodules (mean = 0.5 nodules per plant), and lineage Ia plants inoculated with the lineage E isolate had a mean of only 20 nodules per plant. Nodule numbers averaged 44 to 207 per plant in most combinations, which resembles the range seen with native Amphicarpaea bacterial isolates (19). However, lineage Ib plants inoculated with the other lineage A bacterial isolate (ApT2) developed numerous very tiny nodules (mean = 258 per plant). This contrasts with the lack of nodule formation by these plants with the lineage A bacteria that are endemic to Amphicarpaea populations (19, 35).

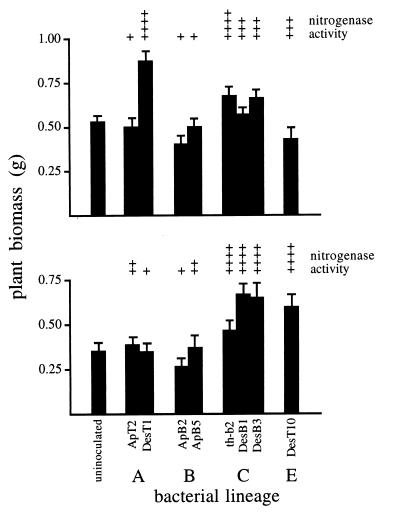

Only a few isolates significantly enhanced plant growth relative to uninoculated control plants. For lineage Ia hosts (Fig. 5, top panel), Student-Newman-Keuls multiple range tests showed that only isolate DesT1 significantly improved plant growth (using an experiment-wise error rate of α = 0.05). For lineage Ib hosts (Fig. 5, bottom panel), only isolates DesB1, DesB3, and DesT10 caused growth significantly higher than that seen in the controls.

FIG. 5.

Symbiotic performance of two A. bracteata plant lineages (Ia, top panel; Ib, bottom panel) inoculated with Bradyrhizobium isolates from Apios and Desmodium. Bars indicate plant biomass (mean ± 1 standard error), and above each bar is the relative nitrogenase activity of root nodules analyzed by acetylene reduction assays (+, 0.04 to 0.16 μmol of ethylene min−1 plant−1; ++, 0.17 to 0.64 μmol of ethylene min−1 plant−1; +++, 0.65 to 2.56 μmol of ethylene min−1 plant−1; ++++, >2.56 μmol of ethylene min−1 plant−1).

There was a 1,000-fold variation in nitrogenase activity (measured by acetylene reduction) among different combinations of plants and bacteria. However, since only two to three plants were assayed per combination, results are only presented qualitatively in Fig. 5. The main overall pattern was that all combinations where bacterial inoculation significantly increased plant growth also showed high nitrogenase activity. However, not all plants displaying high nitrogenase activity showed significant improvements in growth relative to the uninoculated controls. For example, lineage Ia hosts inoculated with lineage E bacteria had relatively high nitrogenase activity. Yet their mean biomass was 23% below that of uninoculated plants, implying that lineage E bacteria were poorly adapted symbionts for these hosts. Plants inoculated with lineage B isolates from Apios consistently showed minimal biomass gain, and nitrogenase activity also tended to be low (0.08 to 0.24 μmol of ethylene min−1 plant−1). Interestingly, lineage B isolates are common in many Amphicarpaea populations, and these often tend to be ineffective symbionts as well (35).

No lineage D isolates were tested for effects on plant biomass. However, a small-scale inoculation test with the ET17 isolate (Fig. 1) indicated that it caused nodule development in the normal range on Amphicarpaea lineage Ib plants (mean = 114 nodules per plant) but formed very few nodules on Ia hosts (mean = four nodules per plant). Nitrogenase assays revealed that activity was quite low on Ia hosts (0.05 μmol of ethylene min−1 plant−1) and moderately high on Ib hosts (1.34 μmol of ethylene min−1 plant−1).

DISCUSSION

The main finding of this study is that there is extensive overlap among the bradyrhizobial symbionts associated with A. bracteata, A. americana, and D. glutinosum. Most Desmodium and Apios isolates had multilocus enzyme allele profiles that were identical to various ETs sampled from Amphicarpaea. Nucleotide sequence analysis of portions of 23S and 16S rRNA also indicated a close relationship between isolates from the three legume genera (Fig. 3 and 4). Desmodium and Amphicarpaea, in particular, appear to share a common pool of symbiotic bacteria, because Amphicarpaea plants inoculated with certain Desmodium isolates had biomass gains and nitrogenase activities that were as good as or better than those achieved with native Bradyrhizobium isolates (Fig. 5). None of the three isolates tested from Apios were very good symbionts for either type of Amphicarpaea host (Fig. 5). Thus, it would be desirable to test additional isolates from Apios to better understand whether these two legume genera currently interact with a common set of bacterial mutualists. Nevertheless, the close genetic similarity of some bacteria from Amphicarpaea and Apios suggests a historical relationship of Bradyrhizobium populations associated with these legumes.

The vast majority of Apios and Desmodium isolates fell into MLEE lineages A, B, and C (64 of 68 isolates [94%]). All Amphicarpaea bacteria also cluster into these same groups (17). The current study supports previous work (25) indicating a phylogenetic relationship between these bacteria and the soybean symbiont B. elkanii (Fig. 3 and 4). For example, 16S rRNA sequences from these bacteria were >98% similar to B. elkanii USDA 94 and were >99% similar to B. elkanii USDA 76. However, despite their 16S rRNA similarity, these bacteria are distinct from B. elkanii in terms of isozyme alleles, nod gene sequences, and symbiotic behavior (12, 25). Because bacterial lineages A, B, and C are also quite divergent from each other for MLEE phenotypes (Table 2) and nodulation host range (19, 35), they possibly represent three distinct species. These bacterial groups are widely distributed across eastern North America (17). The observation that they predominate in nodule samples from three common taxa of native papilionoid legumes raises the question of how many additional legume species in this geographic region (or elsewhere) may also be primarily nodulated by these groups. Future studies of other legumes are planned to resolve the host relationships and systematic status of these bacteria.

Four isolates from Apios and Desmodium (MLEE lineages D and E) were unlike any bradyrhizobia observed in extensive samples from Amphicarpaea. These isolates showed a 23S rRNA length variant similar to B. japonicum USDA 110 (Fig. 2), and parsimony analysis of both 23S and 16S rRNA sequence variation indicated a close relationship to B. japonicum and allied taxa. For both Apios and Desmodium, the simultaneous presence of divergent bradyrhizobial lineages with affinities to B. japonicum and B. elkanii (Fig. 3) emphasizes the high diversity of root nodule bacteria that may be present within even a single local population. Similar results have been observed in other systems (for examples, see references 8 and 9).

Bacterial symbiont sharing across legume taxa is ecologically significant for a number of reasons. First, if plants cause local proliferation of symbiotic bacteria in their vicinity (26, 34), then a site occupied by one plant may become a favorable microhabitat for invasion by a second host. Thus, symbiont sharing across host taxa can make bacterial mutualist partners more predictably available as plants disperse and colonize new habitats. However, since the optimal bacterial partner is not likely to be identical among all cooccurring host taxa, modification of bacterial population composition by some legumes may potentially have a negative effect on certain other plants. A possible example warranting further study is provided by the lineage B isolates harbored by Apios populations (Table 2 and Fig. 1). These bacteria were poor-quality symbionts for both types of Amphicarpaea (Fig. 5), yet isolates resembling these genotypes appear to be prevalent in many Amphicarpaea populations (17, 35). Thus, one legume may potentially create an ecological burden for a second species by serving as a source for bacteria that are inferior-quality symbionts.

Genotypes within a single legume species can also show differential performance with specific strains of rhizobia (10, 16, 35). Each legume may thus experience spatially heterogeneous natural selection arising from effects of various other legume taxa on bacterial population composition. The impact of different legumes on the genetic structure of bacterial populations within natural environments remains very poorly understood. Understanding the spatial scale and temporal dynamics of these processes are key problems that must be addressed by future ecological research on legume-bacterial symbioses.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am grateful to J. Doyle for suggesting population locations, to J. Pfeil for assistance with sequencing, and to L. D. Kuykendall for providing bacterial isolates.

Financial support was provided by NSF grant DEB-9707697.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barrera L L, Trujillo M E, Goodfellow M, Garcia F J, Hernandez-Lucas I, Davila G, van Berkum P, Martinez-Romero E. Biodiversity of bradyrhizobia nodulating Lupinus spp. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:1086–1091. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-4-1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brosius J, Palmer M L, Kennedy P J, Noller H F. Complete nucleotide sequence of a 16S ribosomal RNA gene from Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:4801–4805. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.10.4801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruneau A, Anderson G J. Reproductive biology of diploid and triploid Apios americana (Leguminosae) Am J Bot. 1988;75:1876–1883. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corby H D L, Polhill R M, Sprent J I. Taxonomy. In: Broughton W J, editor. Nitrogen fixation. 3. Legumes. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 1983. pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doyle J J, Doyle J L. Chloroplast DNA phylogeny of the papilionoid legume tribe Phaseoleae. Syst Bot. 1993;18:309–327. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dupuy N, Willems A, Pot B, Dewettinck D, Vandenbruaene I, Maestrojuan G, Dreyfus B, Kersters K, Collins M D, Gillis M. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of bradyrhizobia nodulating the leguminous tree Acacia albida. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1994;44:461–473. doi: 10.1099/00207713-44-3-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution. 1985;39:783–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lafay B, Burdon J J. Molecular diversity of rhizobia occurring on native shrubby legumes in southeastern Australia. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:3989–3997. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.10.3989-3997.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laguerre G, van Berkum P, Amarger N, Prevost D. Genetic diversity of rhizobial symbionts isolated from legume species within the genera Astragalus, Oxytropis, and Onobrychis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4748–4758. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.12.4748-4758.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lohrke J, Orf H, Sadowsky M J. Inheritance of host-controlled restriction of nodulation by Bradyrhizobium japonicum strain USDA 110. Crop Sci. 1996;36:1271–1276. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.6.2378-2383.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ludwig W, Rossello-Mora R, Aznar R, Klugbauer S, Spring S, Reetz K, Beimfohr C, Brockmann E, Kirchhof G, Dorn S, Bachleitner M, Klugbauer N, Springer N, Lane D, Neitupsky R, Weizenegger M, Schleifer K-H. Comparative sequence analysis of 23S rRNA from Proteobacteria. System Appl Microbiol. 1995;18:164–188. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marr D L, Devine T E, Parker M A. Nodulation restrictive genotypes of Glycine and Amphicarpaea: a comparative analysis. Plant Soil. 1997;189:181–188. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nour S M, Cleyet-Marel J-C, Normand P, Fernandez M P. Genomic heterogeneity of strains nodulating chickpeas (Cicer arientinum), and description of Rhizobium mediterraneum sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1995;45:640–648. doi: 10.1099/00207713-45-4-640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oyaizu H, Matsumoto S, Minamisawa K, Gamou T. Distribution of rhizobia in leguminous plants as surveyed by phylogenetic identification. J Gen Appl Microbiol. 1993;39:339–354. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parker M A. Cryptic species within Amphicarpaea bracteata (Leguminosae): evidence from isozymes, morphology, and pathogen specificity. Can J Bot. 1996;74:1640–1650. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parker M A. Mutualism in metapopulations of legumes and rhizobia. Am Nat. 1999;153:S48–S60. doi: 10.1086/303211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parker M A, Spoerke J M. Geographic structure of lineage associations in a plant-bacterial mutualism. J Evol Biol. 1998;11:549–562. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parker M A, Wilkens R T. Effects of disease resistance genes on Rhizobium symbiosis in an annual legume. Oecologia (Berl) 1990;85:137–141. doi: 10.1007/BF00317354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parker M A, Wilkinson H H. A locus controlling nodulation specificity in Amphicarpaea bracteata (Leguminosae) J Hered. 1997;88:449–453. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pielou E C. Mathematical ecology. J. New York, N.Y: Wiley; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Selander R K, Gaugant D A, Ochman H, Musser J M, Gilmour M N, Whittam T S. Methods of multilocus enzyme electrophoresis for bacterial population genetics and systematics. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1986;51:873–884. doi: 10.1128/aem.51.5.873-884.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Selenska-Pobell S, Evguenieva-Hackenberg E. Fragmentation of the large subunit rRNA in the family Rhizobiaceae. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6993–6998. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.23.6993-6998.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sneath P H A, Sokal R R. Numerical taxonomy. W. H. San Francisco, Calif: Freeman; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spoerke J M, Wilkinson H H, Parker M A. Nonrandom genotypic associations in a legume-Bradyrhizobium mutualism. Evolution. 1996;50:146–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1996.tb04481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sterner, J. P., and M. A. Parker. Diversity and relationships of bradyrhizobia from Amphicarpeaea bracteata based on partial nod and ribosomal sequences. Syst. Appl. Microbiol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Thies J E, Woomer P L, Singleton P W. Enrichment of Bradyrhizobium ssp. populations in soil due to cropping of the homologous host legume. Soil Biol Biochem. 1995;27:633–636. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thompson J D, Higgans D G, Gibson T J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Berkum P, Beyene D, Eardly B D. Phylogenetic relationships among Rhizobium species nodulating the common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1996;46:240–244. doi: 10.1099/00207713-46-1-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Berkum P, Beyene D, Bao G, Campbell T A, Eardly B D. Rhizobium mongolense sp. nov. is one of three rhizobial genotypes identified which nodulate and form nitrogen-fixing symbioses with Medicago ruthenica. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1998;48:13–22. doi: 10.1099/00207713-48-1-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Rossum D, Schuurmans F P, Gillis M, Muyotcha A, van Verseveld H W, Stouthamer A H, Boogerd F C. Genetic and phenetic analyses of Bradyrhizobium strains nodulating peanut (Arachis hypogaea) roots. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:1599–1609. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.4.1599-1609.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vincent J M. A manual for the practical study of the root-nodule bacteria. Oxford, England: Blackwell; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vinuesa P, Rademaker J L W, de Bruijn F J, Werner D. Genotypic characterization of Bradyrhizobium strains nodulating endemic woody legumes of the Canary Islands by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of genes encoding 16S rRNA (16S rDNA) and 16S-23S rDNA intergenic spacers, repetitive extragenic palindromic PCR genomic fingerprinting, and partial 16S rRNA sequencing. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:2096–2104. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.6.2096-2104.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang E T, van Berkum P, Sui X H, Beyene D, Chen W X, Martinez-Romero E. Diversity of rhizobia associated with Amorpha fruticosa isolated from Chinese soils and description of Mesorhizobium amorphae sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1999;49:51–65. doi: 10.1099/00207713-49-1-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weaver R W, Frederick L R, Dumenil L C. Effect of soybean cropping and soil properties on numbers of Rhizobium japonicum in Iowa soils. Soil Sci. 1972;114:137–141. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilkinson H H, Spoerke J M, Parker M A. Divergence in symbiotic compatibility in a legume-Bradyrhizobium mutualism. Evolution. 1996;50:1470–1477. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1996.tb03920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Willems A, Collins M D. Phlogenetic analysis of rhizobia and agrobacteria based on 16S rRNA gene sequences. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1993;43:305–313. doi: 10.1099/00207713-43-2-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilson J K. Leguminous plants and their associated organisms. Cornell University Agric Exp Station Memoir. 1939;221:1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilson K. Preparation of genomic DNA from bacteria. In: Ausubel F M, editor. Current protocols in molecular biology. J. New York, N.Y: Wiley; 1994. pp. 2.4.1–2.4.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Young J P W, Johnston A W B. The evolution of specificity in the legume-Rhizobium symbiosis. Trends Ecol Evol. 1989;4:341–349. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(89)90089-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Young J P W, Haukka K E. Diversity and phylogeny of rhizobia. New Phytol. 1996;133:87–94. [Google Scholar]