Key Points

Question

Is there an association between bariatric surgery and the incidence of obesity-associated cancer and cancer-related mortality in patients with obesity?

Findings

In this retrospective cohort study of 30 318 patients (including 5053 patients who underwent bariatric surgery and 25 265 matched patients in the nonsurgical control group), bariatric surgery was significantly associated with a lower risk of obesity-associated cancer (hazard ratio, 0.68) and cancer-related mortality (hazard ratio, 0.52).

Meaning

Among adults with obesity, bariatric surgery compared with no surgery was associated with a significantly lower incidence of obesity-associated cancer and cancer-related mortality.

Abstract

Importance

Obesity increases the incidence and mortality from some types of cancer, but it remains uncertain whether intentional weight loss can decrease this risk.

Objective

To investigate whether bariatric surgery is associated with lower cancer risk and mortality in patients with obesity.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In the SPLENDID (Surgical Procedures and Long-term Effectiveness in Neoplastic Disease Incidence and Death) matched cohort study, adult patients with a body mass index of 35 or greater who underwent bariatric surgery at a US health system between 2004 and 2017 were included. Patients who underwent bariatric surgery were matched 1:5 to patients who did not undergo surgery for their obesity, resulting in a total of 30 318 patients. Follow-up ended in February 2021.

Exposures

Bariatric surgery (n = 5053), including Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy, vs nonsurgical care (n = 25 265).

Main Outcomes and Measures

Multivariable Cox regression analysis estimated time to incident obesity-associated cancer (a composite of 13 cancer types as the primary end point) and cancer-related mortality.

Results

The study included 30 318 patients (median age, 46 years; median body mass index, 45; 77% female; and 73% White) with a median follow-up of 6.1 years (IQR, 3.8-8.9 years). The mean between-group difference in body weight at 10 years was 24.8 kg (95% CI, 24.6-25.1 kg) or a 19.2% (95% CI, 19.1%-19.4%) greater weight loss in the bariatric surgery group. During follow-up, 96 patients in the bariatric surgery group and 780 patients in the nonsurgical control group had an incident obesity-associated cancer (incidence rate of 3.0 events vs 4.6 events, respectively, per 1000 person-years). The cumulative incidence of the primary end point at 10 years was 2.9% (95% CI, 2.2%-3.6%) in the bariatric surgery group and 4.9% (95% CI, 4.5%-5.3%) in the nonsurgical control group (absolute risk difference, 2.0% [95% CI, 1.2%-2.7%]; adjusted hazard ratio, 0.68 [95% CI, 0.53-0.87], P = .002). Cancer-related mortality occurred in 21 patients in the bariatric surgery group and 205 patients in the nonsurgical control group (incidence rate of 0.6 events vs 1.2 events, respectively, per 1000 person-years). The cumulative incidence of cancer-related mortality at 10 years was 0.8% (95% CI, 0.4%-1.2%) in the bariatric surgery group and 1.4% (95% CI, 1.1%-1.6%) in the nonsurgical control group (absolute risk difference, 0.6% [95% CI, 0.1%-1.0%]; adjusted hazard ratio, 0.52 [95% CI, 0.31-0.88], P = .01).

Conclusions and Relevance

Among adults with obesity, bariatric surgery compared with no surgery was associated with a significantly lower incidence of obesity-associated cancer and cancer-related mortality.

This matched cohort study investigates whether bariatric surgery is associated with lower cancer risk and mortality in adult patients with a body mass index of 35 or greater who underwent bariatric surgery at a US health system between 2004 and 2017 vs those who did not undergo surgery for their obesity.

Introduction

Obesity increases the incidence and mortality from some types of cancer. With obesity growing in prevalence worldwide, the effects of obesity-associated cancer on public health are considerable. It remains uncertain whether intentional weight loss can decrease this risk. Conducting sufficiently powered randomized clinical trials with adequate follow-up to assess the effects of intentional weight loss on cancer incidence and mortality is extremely challenging. The incidence of cancer is relatively low and there is a long interval between the exposure (weight loss) and the outcome (development of cancer). Furthermore, many patients with obesity cannot achieve substantial and sustained weight loss only with lifestyle modifications, which would likely be required to meaningfully influence cancer risk.1,2,3,4

Bariatric surgery is the most effective currently available treatment for obesity. Patients typically lose 20% to 35% of body weight after surgery, which is often sustained for many years.5,6,7,8,9 A few observational studies have reported an association between bariatric surgery and reduced cancer risk.3,9,10,11,12,13,14,15 Although they add important findings to the literature, they also leave an opportunity for additional questions to be answered. For example, reliable data are lacking on cancer-related mortality and on cancer risk after different surgical procedures, which distinctly alter anatomy.

This study was designed to investigate the relationship between contemporary bariatric procedures and the incidence of a large number of cancer types and cancer-related mortality during long-term follow-up.

Methods

The Surgical Procedures and Long-term Effectiveness in Neoplastic Disease Incidence and Death (SPLENDID) is a retrospective, observational, matched cohort study in adult patients with obesity who underwent bariatric surgery or received usual care (did not undergo bariatric surgery) at the Cleveland Clinic Health System (CCHS). The study was approved by the CCHS institutional review board as minimal risk research using data collected during routine clinical practice for which the need for informed consent from patients was waived.

During the initial screening process, all patients who had at least a single occurrence of body mass index (BMI; calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) of 35 or greater in the electronic health record (EHR) between January 1, 2004, and December 31, 2017, were considered for inclusion.

Clinical diagnoses, procedure codes, medication use, and other baseline and follow-up data were extracted from the EHRs in the CCHS.16 Diagnosis and procedure codes appear in eTables 1-5 in the Supplement. A diagnosis of incident cancer during follow-up was ascertained by reviewing histopathologic reports or notes from oncologists in the EHRs, either from internal CCHS data or through the Epic Care Everywhere interoperability platform, which provides data exchange of EHRs between health care systems.17

Surgical Cases

The date of the first bariatric surgery served as the index date for patients in the bariatric surgery group. The study included patients aged 18 years to 80 years, who had a BMI between 35 and 80 at the time of surgery, and who underwent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) or sleeve gastrectomy (SG) at CCHS hospitals located in Florida and Ohio.

Patients were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: (1) had any history of cancer, carcinoma in situ, or tumors with uncertain behavior, (2) had a history of excessive alcohol use or any medical conditions related to alcohol use disorder, (3) had received an organ transplant, (4) had HIV infection, (5) had ascites, (6) had peptic ulcer disease, (7) were undergoing dialysis, (8) had a left ventricular ejection fraction less than 20%, (9) had a history of admission to the emergency department within 5 days prior to surgery, or (9) had less than 12 months of follow-up before the index date (to increase the chance of including patients who had their routine care at the CCHS) (Figure 1; the diagnosis codes appear in eTable 1 in the Supplement).

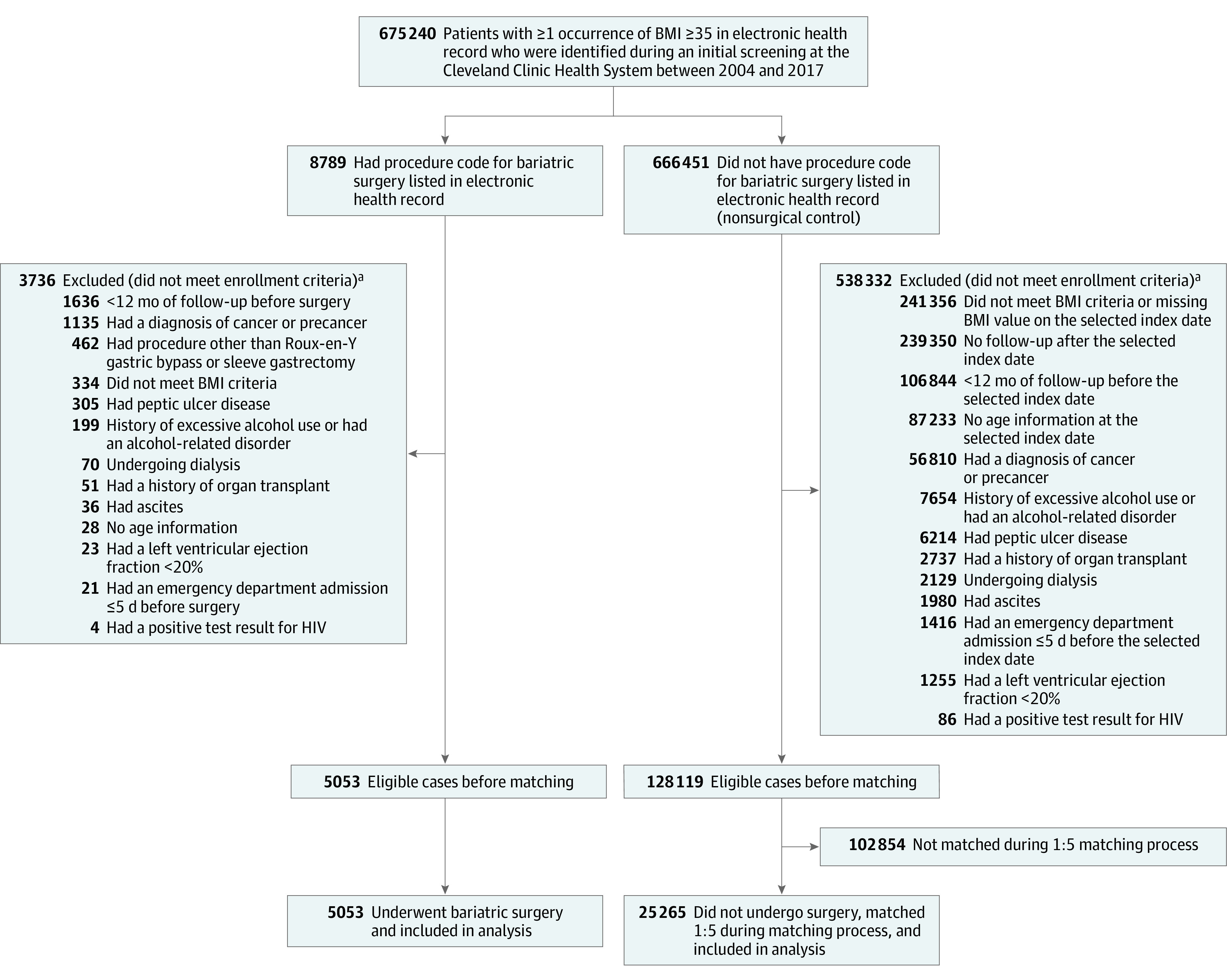

Figure 1. Identification of Eligible Patients and Development of Cohorts in the SPLENDID Study.

To create a comparable control group, dates for bariatric surgery were randomly assigned to a pool of 666 451 patients with a body mass index (BMI; calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) of 35 or greater. Patients who had not undergone bariatric surgery were then removed from the pool if they failed to meet inclusion criteria on the assigned date, at which point the patients could be seen as potentially eligible for bariatric surgery. Using this algorithm, 128 119 comparable patients who had not undergone surgery were identified to be considered for matching. With propensity matching of each patient who underwent bariatric surgery to 5 patients who had not undergone surgery (nonsurgical control), 5053 patients in the bariatric surgery group and 25 265 matched patients in the nonsurgical control group were enrolled in the study. The diagnosis and procedure codes appear in eTables 1-2 in the Supplement. SPLENDID indicates Surgical Procedures and Long-term Effectiveness in Neoplastic Disease Incidence and Death.

aA patient may have met more than 1 exclusion criterion; therefore, the total excluded exceeds the sum of the individual reasons for exclusion.

Nonsurgical Comparators

Among patients who were identified during the initial screening process, those with any procedure codes for weight loss surgery in the EHRs were excluded. Subsequently, each patient was randomly assigned a single date from the collection of surgery dates for patients in the bariatric surgery group. This was considered as the selected index date for patients in the nonsurgical control group.6 Patients were excluded from the nonsurgical control group if they met any of the following criteria on the selected index date: (1) were younger than 18 years of age or older than 80 years, (2) had a BMI of less than 35 or greater than 80, (3) met any of the exclusion criteria mentioned in the prior section for patients in the bariatric surgery group, or (4) had their last follow-up visit or died on or before the selected index date (Figure 1).

End Points

The primary composite end point was the first occurrence of 1 of the 13 types of obesity-associated malignant cancer as described by the International Agency for Research on Cancer Handbook Working Group4 as having sufficient evidence for an association. The primary end point included esophageal adenocarcinoma; renal cell carcinoma; postmenopausal breast cancer (diagnosed at ≥55 years of age) or breast cancer in younger patients who had bilateral oophorectomy; cancer of the gastric cardia, colon, rectum, liver, gallbladder, pancreas, ovary, corpus uteri, or thyroid; and multiple myeloma.

Two secondary end points included the incidence of all types of malignant cancer and cancer-related mortality (defined as death related to any cancer in patients with incident cancer after the index date).

Changes in body weight were compared among the patients in the bariatric surgery group vs patients in the nonsurgical control group. As an exploratory end point, the minimum amount of weight loss needed to see a beneficial change in incidence of obesity-associated cancer was estimated. Patients were censored at the last known follow-up date (ie, last hospital discharge date or last office visit, whichever was later), death, or at the end of follow-up (February 2021).

Statistical Analysis

Baseline data were presented as median (IQR) and number (percentage). Doubly robust estimation combining the propensity score and outcome regression was used. Each patient who underwent bariatric surgery was matched with a propensity score by the nearest-neighbor method to 5 patients who did not undergo bariatric surgery (nonsurgical control), using a logistic regression model based on 10 a priori–identified potential confounders. The matching variables included the index date, age, sex, race (which was obtained from the EHR based on patient self-report using fixed categories and was classified as Black, White, or other), BMI on the index date (35-39.9, 40-44.9, 45-49.9, 50-54.9, 55-59.9, or 60-80), smoking history (categorized as never, former, or current), presence of type 2 diabetes, Elixhauser Comorbidity Index, Charlson Comorbidity Index, and state of residence (Florida, Ohio, or other US state).

Cause-specific event rates per 1000 person-years of follow-up starting from the index date were estimated for each outcome within each study group. Cumulative incidence estimates (Kaplan-Meier method) for 10 years after the index date and the absolute risk difference for each outcome were calculated. The 95% CIs for the between-group difference in 10-year risk were obtained by using the percentile method from 1000 bootstrap iterations.

Fully adjusted Cox proportional hazards regression models were generated for the primary and secondary end points. To minimize the effects of confounding factors, the Cox models were adjusted for annual income within zip code, hemoglobin level, serum calcium level, estimated glomerular filtration rate, medication use (aspirin, hormonal therapy for menopause, diabetes, antihypertensive, and lipid-lowering), and the 10 baseline variables that were used for matching. The proportional hazards assumptions for the treatment variable were satisfied for the primary and secondary end points.18

Overall, there were limited missing data (Table). The missing values were imputed using multiple imputation by chained equations to create 5 imputed data sets. A regression-based imputation model with predictive mean matching was used. Imputation-corrected SEs of the model estimates and comparisons were obtained using the Rubin formula.19,20

Table. Characteristics of Patients at Baseline and During Follow-up.

| Bariatric surgery (n = 5053) |

Nonsurgical control (n = 25 265) |

Standardized mean difference, %a |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics | |||

| Index year, median (IQR) | 2013 (2010 to 2015) | 2013 (2010 to 2015) | 2.1 |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 46.0 (37.0 to 55.0) | 46.0 (34.0 to 57.0) | 4.2 |

| Sex, No. (%) | |||

| Female | 3884 (76.9) | 19 514 (77.2) | 0.9 |

| Male | 1169 (23.1) | 5751 (22.8) | |

| Body mass index, median (IQR)b | 45.5 (41.0 to 51.6) | 45.1 (40.7 to 50.1) | 13.0 |

| Body mass index by category, No. (%) | |||

| 35-39.9 | 1005 (19.9) | 4912 (19.4) | 12.8 |

| 40-44.9 | 1372 (27.2) | 7611 (30.1) | |

| 45-49.9 | 1150 (22.8) | 6279 (24.9) | |

| 50-54.9 | 743 (14.7) | 3477 (13.8) | |

| 55-59.9 | 393 (7.8) | 1608 (6.4) | |

| 60-80 | 390 (7.7) | 1378 (5.4) | |

| Race, No. (%)c | |||

| Black | 1153 (22.8) | 5854 (23.2) | 0.9 |

| White | 3724 (73.7) | 18 542 (73.4) | |

| Otherd | 176 (3.5) | 869 (3.4) | |

| State of residence, No. (%) | |||

| Florida | 829 (16.4) | 3069 (12.1) | 12.6 |

| Ohio | 3997 (79.1) | 21 164 (83.8) | |

| Other US state | 227 (4.5) | 1032 (4.1) | |

| Smoking status, No. (%) | |||

| Never | 3019 (59.7) | 15 763 (62.4) | 5.9 |

| Former | 1889 (37.4) | 8912 (35.3) | |

| Current | 145 (2.9) | 590 (2.3) | |

| Annual income within zip code, median (IQR), $e | 51 962 (42 613 to 67 184) | 50 642 (38 750 to 65 430) | 8.7 |

| Medical history | |||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, median (IQR)f | 2.0 (1.0 to 3.0) | 1.0 (0 to 3.0) | 28.7 |

| Elixhauser Comorbidity Index, median (IQR)g | 1.0 (−4.0 to 8.0) | 0 (−1.0 to 4.0) | 13.7 |

| Type 2 diabetes, No. (%) | 1364 (27.0) | 6252 (24.7) | 5.1 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, No. (%) | 1340 (26.5) | 6424 (25.4) | 2.5 |

| Heart failure, No. (%) | 328 (6.5) | 1953 (7.7) | 4.8 |

| Myocardial infarction, No. (%) | 138 (2.7) | 891 (3.5) | 4.6 |

| Laboratory data, median (IQR) | |||

| Calcium, mg/dLh | 8.60 (8.30 to 8.90) | 9.30 (9.00 to 9.60) | 133.6 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dLi | 11.7 (10.8 to 12.7) | 13.0 (11.9 to 14.1) | 72.1 |

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate, mL/minj | 104 (86 to 122) | 93 (76 to 112) | 35.3 |

| Type of medication use, No. (%) | |||

| Antihypertensive | 4283 (84.8) | 12 348 (48.9) | 82.4 |

| Lipid-lowering | 1817 (36.0) | 7095 (28.1) | 16.9 |

| Diabetes | 1789 (35.4) | 7229 (28.6) | 14.6 |

| Aspirin | 1164 (23.0) | 4766 (18.9) | 10.3 |

| Hormone therapy | 752 (14.9) | 2871 (11.4) | 10.4 |

| Cancer screening before the index date, No. (%)k | |||

| For breast cancer | 891 (17.6) | 1429 (5.7) | 38.0 |

| For colorectal cancer | 322 (6.4) | 277 (1.1) | 28.1 |

| For prostate cancer | 128 (2.5) | 168 (0.7) | 14.9 |

| Follow-up characteristics | |||

| Length of follow-up, median (IQR), y | 5.8 (3.4 to 8.8) | 6.1 (3.9 to 8.9) | 7.7 |

| Length of follow-up by sex, median (IQR), y | |||

| Female | 5.8 (3.4 to 8.9) | 6.1 (3.9 to 9.0) | 9.2 |

| Male | 5.8 (3.1 to 8.6) | 5.9 (3.7 to 8.6) | 6.7 |

| Cancer screening after the index date, No. (%)l | |||

| For breast cancer | 1883 (37.3) | 3482 (13.8) | 55.9 |

| For colorectal cancer | 1340 (26.5) | 1880 (7.4) | 52.5 |

| For prostate cancer | 420 (8.3) | 578 (2.3) | 27.1 |

The absolute value of the difference in means or proportions between the bariatric surgery group and the nonsurgical control group divided by the pooled SD. Values of 10% or less indicate appropriate matching.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Obtained from the electronic health record based on patient self-report using fixed categories. This characteristic was included in the analyses because it could be associated with both exposure and study end points.

American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, multiracial, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, and not reported.

Data are for 4965 patients in the bariatric surgery group and 24 968 in the nonsurgical control group.

Score range is 0 to 29; a higher score indicates greater disease burden and greater prediction for risk of death.

With van Walraven weights, the score range is –19 to 89; a higher score indicates greater comorbidity burden and greater likelihood for in-hospital death.

Data are for 5053 patients in the bariatric surgery group and 19 453 in the nonsurgical control group.

Data are for 5053 patients in the bariatric surgery group and 19 288 in the nonsurgical control group.

Approximated using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease study equation. Data are for 5053 patients in the bariatric surgery group and 19 587 in the nonsurgical control group.

At least 1 screening test for detection of cancer within 12 months prior to the index date.

At least 1 screening test for detection of cancer from the index date until the diagnosis of cancer or until the last follow-up.

For the subgroup analyses of the primary end point, an interaction term between the variables of interest (eg, median age, BMI) and the treatment variable was individually added to the fully adjusted Cox model. The association of bariatric surgery type (RYGB or SG) with the primary end point was separately examined.

Change in body weight between the bariatric surgery group and the nonsurgical control group was fitted with a nonlinear regression model using a 4-knot spline interacted with treatment. An unpaired, 2-sided t test was used to compare the between-group mean differences at 10 years. An unadjusted analysis was performed in the bariatric surgery group for incidence of obesity-associated cancer by quartile of largest (maximum) percentage of weight loss and the log-rank test was used to assess for trend. The largest percentage of weight loss was determined between the surgery date and the 12 months prior to a cancer diagnosis or until the last follow-up for those who were not diagnosed as having cancer.

A significance level of .05 for 2-sided comparisons was considered statistically significant and 95% CIs were reported when applicable. Because of the nature of the study and the potential for type I error due to multiple comparisons, all findings should be interpreted as exploratory. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.5.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Sensitivity Analyses

Four different approaches for the sensitivity analyses were conducted. The sensitivity of the hazard ratio (HR) estimates from the fully adjusted Cox proportional hazards regression models was assessed for 2 components of the process used in creating the nonsurgical control group: random assignment of index dates and the ratio used for matching. The bariatric surgery index dates were randomly assigned to patients potentially included in the nonsurgical control group 5 times, and the matching ratio was repeated with 1:1, 1:3, and 1:5 in the creation of 15 data sets. The fully adjusted Cox models for the primary end point were analyzed on all 15 data sets, although the results from 1 data set were reported as the primary comparison.

In an additional sensitivity analysis, to account for undetected prevalent cancer at baseline, the analysis of the primary end point was repeated without considering cancer cases that occurred during the first 3 years after the index date.

We also calculated the E-value, which can be used to assess the robustness of the identified association between bariatric surgery and cancer risk and mortality to the potential unmeasured confounders.21,22

Among the 13 types of cancer that are recognized as obesity-associated cancers by the International Agency for Research on Cancer Handbook Working Group,4,23 the mendelian randomization approach provided enough evidence to support the causal association of obesity with esophageal adenocarcinoma, renal cell carcinoma, and cancers of the colon, rectum, pancreas, ovary, and endometrium.24 As a sensitivity analysis, we examined the first occurrence of 1 of these 7 types of cancer.

Results

A total of 30 318 patients (median age, 46 years; median BMI, 45; 77% female; and 73% White), including 5053 who underwent bariatric surgery and 25 265 who did not undergo bariatric surgery (nonsurgical control) were included in the primary comparison. The bariatric procedures included in this study were RYGB (n = 3348; 66%) and SG (n = 1705; 34%).

The distribution of key baseline covariates was well-balanced after matching between the bariatric surgery group and the nonsurgical control group. Some baseline comorbidities were more prevalent in the bariatric surgery group than in the nonsurgical control group (Table).

Follow-up was over a 17-year period (ended in February 2021), with a median follow-up of 6.1 years (IQR, 3.8-8.9 years) for the entire cohort, including 5.8 years (IQR, 3.4-8.8 years) for patients in the bariatric surgery group and 6.1 years (IQR, 3.9-8.9 years) for patients in the nonsurgical control group. Patients in the bariatric surgery group were more likely to have had screening tests for breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer compared with patients in the nonsurgical control group (Table).

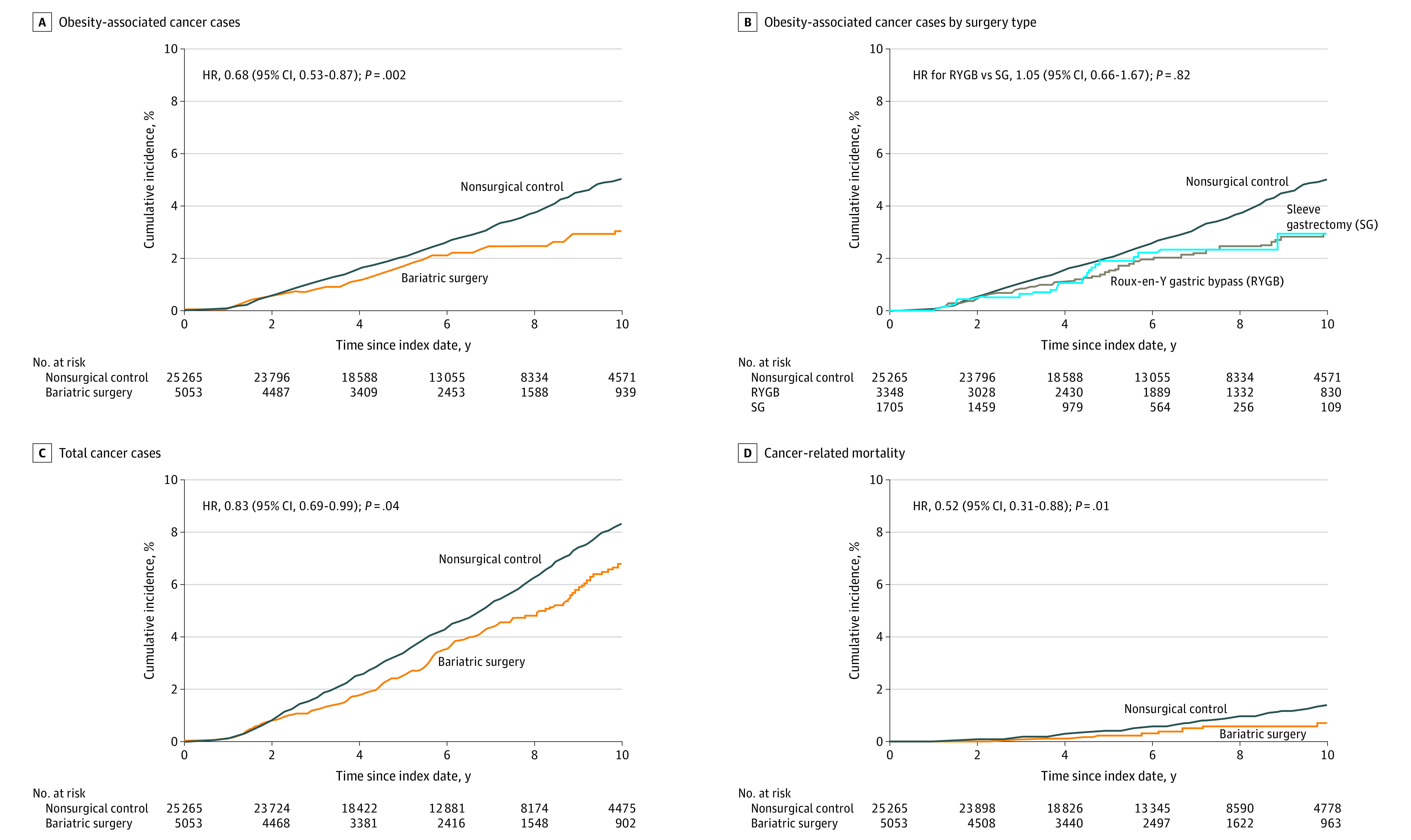

Primary End Point

During follow-up, 96 patients in the bariatric surgery group and 780 patients in the nonsurgical control group had an incident obesity-associated cancer (incidence rate of 3.0 events vs 4.6 events, respectively, per 1000 person-years). The cumulative incidence of the primary end point at 10 years was 2.9% (95% CI, 2.2%-3.6%) in the bariatric surgery group and 4.9% (95% CI, 4.5%-5.3%) in the nonsurgical control group (absolute risk difference, 2.0% [95% CI, 1.2%-2.7%]; adjusted HR, 0.68 [95% CI, 0.53-0.87], P = .002; Figure 2A).

Figure 2. 10-Year Cumulative Incidence Estimates (Kaplan-Meier) for the Primary and Secondary End Points.

A, The primary composite end point was the first occurrence of 1 of the 13 types of obesity-associated cancer. The median observation time was 5.9 years (IQR, 3.4-8.9 years) for patients in the bariatric surgery group and was 6.1 years (IQR, 3.9-9.2 years) for patients in the nonsurgical control group. B, The risk for the primary end point was assessed separately after RYGB and SG. The median observation time was 6.8 years (IQR, 3.4-10.0 years) for RYGB and was 4.6 years (IQR, 3.0-6.8 years) for SG. C, The occurrence of all cancer types was a secondary end point. The median observation time was 5.8 years (IQR, 3.4-8.8 years) for patients in the bariatric surgery group and was 6.1 years (IQR, 3.9-8.9 years) for patients in the nonsurgical control group. D, Cancer-related mortality was a secondary end point. The median observation time was 6.0 years (IQR, 3.4-9.0 years) for patients in the bariatric surgery group and was 6.3 years (IQR, 4.0-9.1 years) for patients in the nonsurgical control group. HR indicates hazard ratio.

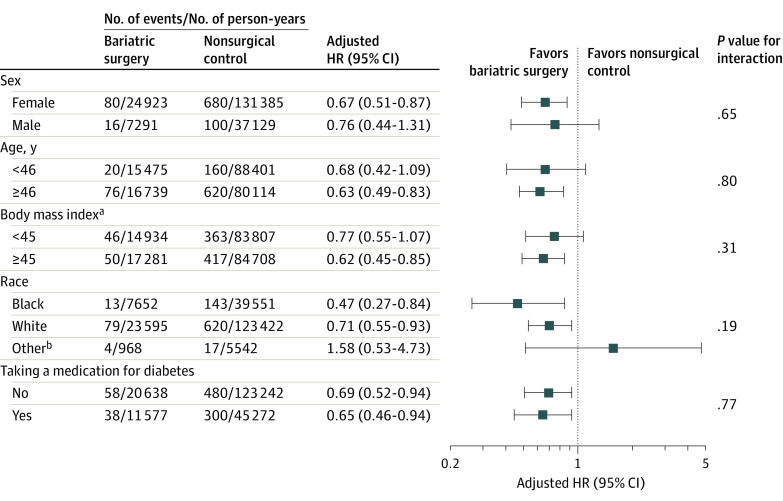

Testing for interaction revealed no heterogeneity for the association between bariatric surgery and the primary outcome based on sex, age, BMI, race, and use of a diabetes medication (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Association of Bariatric Surgery vs Nonsurgical Controls for the Primary End Point in Key Subgroups in the Fully Adjusted Cox Models.

Testing for interaction revealed no heterogeneity in the association of bariatric surgery with the primary end point in a wide range of patients including both men and women, young and old patients, Black and White patients, and patients with or without diabetes. The adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) were obtained after individually removing the original variable from the fully adjusted Cox model and replacing it with the dichotomous subgroup variable as well as its interaction with the treatment variable. For example, the continuous age covariate was replaced by the dichotomous version and its interaction with the treatment. Age and body mass index were categorized based on their median values.

aCalculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

bAmerican Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, multiracial, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, and not reported.

In the analysis of the primary end point based on the surgery type, the cumulative incidence of the primary end point at 10 years was 2.9% (95% CI, 2.1%-3.6%) in the RYGB subgroup and 2.9% (95% CI, 1.5%-4.4%) in the SG subgroup (adjusted HR, 1.05 [95% CI, 0.66-1.67]; Figure 2B). Compared with the nonsurgical control group, the adjusted HR was 0.70 (95% CI, 0.53-0.92) for the RYGB subgroup and was 0.66 (95% CI, 0.44-1.00) for the SG subgroup.

Secondary End Points

At the end of the study period, 200 patients in the bariatric surgery group and 1331 patients in the nonsurgical control group developed any type of invasive cancer (incidence rate of 6.3 events vs 8.0 events, respectively, per 1000 person-years). The cumulative incidence for the composite end point of all types of cancer at 10 years was significantly lower in the bariatric surgery group compared with the nonsurgical control group (6.8% [95% CI, 5.7%-7.9%] vs 8.3% [95% CI, 7.8%-8.8%], respectively; absolute risk difference, 1.5% [95% CI, 0.3%-2.7%]; adjusted HR, 0.83 [95% CI, 0.69-0.99], P = .04; Figure 2C).

Cancer-related mortality occurred in 21 patients in the bariatric surgery group and in 205 patients in the nonsurgical control group (incidence rate of 0.6 events vs 1.2 events, respectively, per 1000 person-years). The cumulative incidence of cancer-related mortality at 10 years was 0.8% (95% CI, 0.4%-1.2%) in the bariatric surgery group and 1.4% (95% CI, 1.1%-1.6%) in the nonsurgical control group (absolute risk difference, 0.6% [95% CI, 0.1%-1.0%]; adjusted HR, 0.52 [95% CI, 0.31-0.88], P = .01; Figure 2D).

Incidence of Individual Cancer Types

The cancer-specific event rates per 1000 person-years of follow-up and the bootstrap 95% CIs for the difference in event rates between the bariatric surgery group and the nonsurgical control group appear in eTable 6 in the Supplement. The 2 most common types of cancer in this cohort included female breast cancer and corpus uteri (endometrial) cancer.

Most cancer types were less common in the bariatric surgery group. However, in the fully adjusted Cox models, the association between bariatric surgery and individual cancer types was only significant for endometrial cancer (adjusted HR, 0.47 [95% CI, 0.27-0.83]).

Change in Body Weight and Cancer Risk

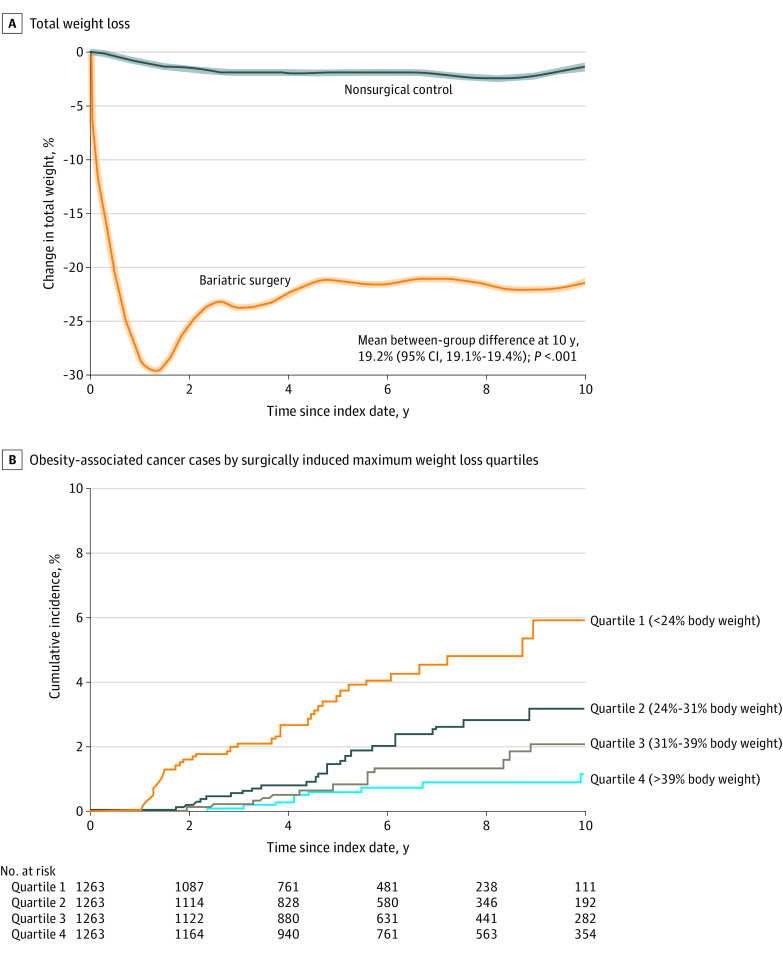

At 10 years, patients in the bariatric surgery group had lost 27.5 kg (95% CI, 27.3-27.8 kg) and patients in the nonsurgical control group had lost 2.7 kg (95% CI, 2.4-3.0 kg) (mean between-group difference, 24.8 kg [95% CI, 24.6-25.1 kg]). Patients in the bariatric surgery group had a 19.2% (95% CI, 19.1%-19.4%) greater weight loss from baseline to 10 years than patients in the nonsurgical control group (P < .001; Figure 4A).

Figure 4. Weight Loss and Cumulative Incidence of Primary End Point Stratified by Maximum Weight Loss Quartile.

A, The data were smoothed and are mean trends for the percentage change in body weight from baseline in patients in the bariatric surgery group and the nonsurgical control group during follow-up. The shaded areas indicate 95% CIs. The mean between-group difference at 10 years from baseline was estimated from a flexible regression model with a 4-knot restricted cubic spline for the time × treatment interaction. The median observation time was 5.9 years (IQR, 3.4-9.0 years) for patients in the bariatric surgery group and was 6.3 years (IQR, 4.0-9.2 years) for patients in the nonsurgical control group. B, The data are Kaplan-Meier estimates for incidence of obesity-associated cancer types by the quartile of maximum (the largest) weight loss in the bariatric surgery group (P < .001 from log-rank test). The findings suggest that weight loss in the bariatric surgery group was associated with lower risk of incident cancer cases in a dose-dependent response.

The cumulative incidence of the primary end point by surgically induced maximum weight loss quartile appears in Figure 4B. The incidence of the primary end point was the highest in a subset of patients in the bariatric surgery group who had lost less than 24% of their body weight (first quartile). Further weight loss among patients in the bariatric surgery group was associated with lower risk of incident cancer in a dose-dependent response.

Sensitivity Analyses

Results of the sensitivity analyses on 15 data sets (15 different nonsurgical control cohorts) appear in eFigure 1 in the Supplement. Overall, the HR differences for these data sets were small for obesity-associated cancer compared with the estimates reported in the article from 1 data set (median HR from 15 data sets, 0.67 [IQR, 0.64-0.71]).

Exclusion of 33 patients with obesity-associated cancer in the bariatric surgery group and exclusion of 227 patients with obesity-associated cancer in the nonsurgical control group that occurred during the first 3 years resulted in a significant association between bariatric surgery and the primary end point (adjusted HR, 0.59 [95% CI, 0.43-0.79]).

Comparing the E-values with the HR estimates of known cancer risk factors indicates that it would be unlikely that an unmeasured confounder exists that could account for the observed association between bariatric surgery and cancer risk and mortality (eTable 7 and eMethods in the Supplement).

Considering only 7 cancer types as obesity-associated cancer based on findings from the mendelian randomization studies24 also resulted in a significant association between bariatric surgery and lower risk of incident cancer (adjusted HR, 0.59 [95% CI, 0.42-0.84]; eFigure 2 in the Supplement).

Discussion

In this matched cohort study with long-term follow-up, bariatric surgery was associated with a significant reduction in the risk of obesity-associated cancer, all invasive cancer types, and cancer-related mortality.

Examining a cancer prevention intervention in a randomized clinical trial is challenging.2,3 In the absence of randomized clinical trials, carefully conducted observational studies can provide potentially useful data on the role of intentional weight loss on cancer risk. In the long-term follow-up of the well-matched Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) study9 that included 2010 surgical and 2037 matched control patients, bariatric surgery was significantly associated with lower risk of cancer (HR, 0.67 [95% CI, 0.53-0.85]). In the SOS study,9 87% of the bariatric surgical procedures were either gastroplasty or gastric banding, which have been replaced by more effective procedures in recent years. A large multicenter study from the Kaiser Permanente health system reported a lower risk of developing any cancer (HR, 0.67 [95% CI, 60-74]) and obesity-associated cancer (HR, 0.59 [95% CI, 0.51-0.69]) compared with a matched control group during a mean follow-up of 3.5 years.10

Data on the association between losing weight and cancer-related mortality are limited. The only available study compared 6596 patients in Utah who had the RYGB procedure (1984-2002) and 9442 patients in a control group matched for 3 baseline factors (sex, age, and BMI category).11 Cancer-related mortality was lower in the surgery group compared with the control group (HR, 0.54 [95% CI, 0.37-0.78]).11 The limitations of the Utah study included absence of matching based on baseline health status associated with cancer risk (eg, smoking history or hormone therapy) and lack of follow-up weight changes.11

The mechanisms of excess cancer risk in patients with obesity are not completely understood. In genetically susceptible individuals, excess adiposity may accelerate cancer development by inducing chronic inflammation, increased release of sex-steroid hormones and adipokines, and insulin resistance with associated hyperinsulinemia.2,3,25,26 Bariatric surgery has been shown to attenuate excess inflammation, hyperinsulinemia, and modulate both sex hormones and adipokine levels.26,27,28,29,30 The mechanisms responsible for reduced cancer risk after bariatric surgery require further study.

Among all cancer types, endometrial cancer has the strongest association with obesity.2,3,4 The current study found that bariatric surgery was associated with a significant reduction in risk of endometrial cancer. Although the association between bariatric surgery and lower risk of different cancer types has been reported in prior studies,10,12,13,14 in the SOS trial31 and in the study performed in Utah,11 consistent with the findings from the current SPLENDID study, endometrial cancer was the only cancer type that had a significantly lower incidence after surgery compared with the nonsurgical control group (HRs, 0.56 and 0.22, respectively). A study in 72 women with severe obesity, for whom endometrial biopsies were examined before and after bariatric surgery, showed a significant reduction in the markers of endometrial proliferation and oncogenic signaling after surgery.26

In current practice, the 2 most common bariatric procedures are SG and RYGB. Although the extent of weight loss is comparable between the 2 procedures, they have different physiological effects. A large part of the stomach is removed with SG, whereas the gastrointestinal tract is re-routed with RYGB. Overlap of Kaplan-Meier curves for RYGB and SG (Figure 2B) suggests that losing weight itself, not procedure-specific physiological changes related to anatomical alterations, could be the principal mechanism for reduced risk of obesity-associated cancer.

In the current study and in other studies, substantial weight loss was required to observe a meaningful reduction in the cancer risk in a dose-dependent response30 (Figure 4B) and the separation of the Kaplan-Meier curves for incident obesity-associated cancer was only observed 6 years after the index date (Figure 2A).31 Currently, bariatric surgery is the only available treatment that can provide this magnitude and durability of weight loss. In an observational single-group study30 of 2107 patients who underwent bariatric surgery, 82 new cancer cases were diagnosed after a median follow-up of 5.5 years. Patients who lost greater than 20% of their total weight were at a significantly reduced risk of cancer compared with those who lost less than 20%.30 In contrast, other studies did not find an association between the extent of weight loss and the risk of obesity-associated cancer.9,32 Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes)1 is the only available randomized clinical trial that has examined long-term cancer outcomes after a nonsurgical weight loss intervention. Among nearly 5000 participants, an intensive lifestyle intervention led to only modest weight loss (8.6% vs 0.7% at 1 year; 6.5% vs 4.6% at 12 years).1 The difference in weight loss was not large enough to statistically mitigate the risk of obesity-associated cancer (HR, 0.84 [95% CI, 0.68-1.04]) or cancer-related mortality (HR, 0.92 [95% CI, 0.68-1.25]).1

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, although a doubly robust approach using comprehensive matching with fully adjusted regression models on a broad range of potential confounding variables was used, residual measured or unmeasured confounders could have influenced the findings and causal inference cannot be assumed. For example, patients who undergo bariatric surgery could partake in healthier lifestyles or use less tobacco and alcohol during follow-up than the nonsurgical control group, leading to healthy user bias. Similarly, physical activity, dietary habits, and exposure to UV light, environmental carcinogens, and cancer-causing pathogens were unknown. Nonetheless, the findings were consistent in several sensitivity analyses. The E-value was used to assess the robustness of observed associations in the presence of potential unmeasured confounders.21,22 The magnitude of the associations of the known cancer risk factors with the study end points was smaller than the estimated E-value for the study end points. Although this suggests that it was unlikely that there were unmeasured confounders that could eliminate the favorable association between bariatric surgery and cancer risk and mortality, the findings may still reflect selection bias.

Second, patients with obesity are often reluctant to undergo cancer screening tests.33,34 Infrequent and irregular cancer screening tests and unbalanced screening frequencies between the study groups might introduce surveillance bias. However, in this study, the nonsurgical control group did not undergo more intense cancer screening tests than the bariatric surgery group that could explain the higher incidence of cancer in the nonsurgical control group.

Third, although the International Agency for Research on Cancer Handbook Working Group identified sufficient evidence for an association between obesity and 13 types of cancer,4,23 recent studies using mendelian randomization strategies have supported the causal association of obesity with only 7 of the 13 cancer types.24 Nonetheless, the findings were consistent regardless of considering 7 or 13 cancer types as obesity-associated cancers. As studies on the link between obesity and cancer develop, future research on cancer risk reduction after bariatric surgery should focus on those cancer types indicated to be causally related to obesity.

Fourth, a small number of incident cancer cases limited the statistical power for comprehensive analysis of individual cancer types. Fifth, the median follow-up time was 6 years and the Kaplan-Meier curves started to separate around that time. This may lead to an underestimation of the long-term association between bariatric surgery and reduced cancer incidence. Sixth, even though the relatively young age of participants is comparable with other bariatric surgery studies,9,10,11,12,13,14,15 younger age may lead to a lower incidence of age-associated cancers in the current study. Nonetheless, there was no heterogeneity in the observed response in patients older or younger than 46 years of age (Figure 3).

Seventh, 96.5% of patients were either Black or White. Although this study showed that bariatric surgery was associated with lower risk of obesity-associated cancer in both Black people and White people (Figure 3), this finding may not be generalizable to individuals in other racial and ethnic groups who were rare in the current study. Eighth, coding errors, misclassification, and misdiagnosis are possible in EHR-based studies. Ninth, although patients who had less than 12 months of follow-up before the index date were excluded to increase the chance of including patients who had their routine care at the CCHS, it is possible that some patients were diagnosed and treated for cancer outside the CCHS or the Epic Care Everywhere interoperability platform.

Conclusions

Among adults with obesity, bariatric surgery compared with no surgery was associated with a significantly lower incidence of obesity-associated cancer and cancer-related mortality.

eTable 1. Diagnosis Codes to Assist in Identifying Pre-existing Conditions that Could Disqualify Patients for Study Eligibility

eTable 2. Procedure and Diagnosis Codes to Assist in Identifying Different Types of Bariatric and Metabolic Surgical Interventions

eTable 3. Diagnosis Codes to Assist in Identifying Baseline Medical Conditions

eTable 4. Diagnosis Codes to Assist in Identifying Malignant Obesity-Associated Cancers (Primary End Point)

eTable 5. Diagnosis Codes to Assist in Identifying Any Type of Malignant Cancer (Secondary End Point)

eTable 6. Cancer-Specific Event Rates (%) per 1000 Person-Years of Follow-up for Each Cancer Type Stratified by Surgical and Nonsurgical Patients

eTable 7. E-value for the Effect of Bariatric Surgery on Study End Points (and its Upper Limit of 95% CI) in Fully-Adjusted Cox Models

eMethods. E-Value: Sensitivity Analysis for Unmeasured Confounding

eFigure 1. Hazard Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals for Bariatric Surgery Versus No Surgery from Fully-Adjusted Cox Models for Primary End Point for 5 Iterations of Index Date Random Sampling and 3 Different Matching Ratios (Total of 15 Data Sets for Sensitivity Analysis)

eFigure 2. 10-year Cumulative Incidence Estimates (Kaplan-Meier) of Seven Obesity-Associated Cancers Identified by Mendelian Randomization Approach

References

- 1.Yeh HC, Bantle JP, Cassidy-Begay M, et al. ; Look AHEAD Research Group . Intensive weight loss intervention and cancer risk in adults with type 2 diabetes. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2020;28(9):1678-1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruno DS, Berger NA. Impact of bariatric surgery on cancer risk reduction. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(suppl 1):S13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byers T, Sedjo RL. Does intentional weight loss reduce cancer risk? Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011;13(12):1063-1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lauby-Secretan B, Scoccianti C, Loomis D, et al. ; International Agency for Research on Cancer Handbook Working Group . Body fatness and cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(8):794-798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adams TD, Davidson LE, Litwin SE, et al. Weight and metabolic outcomes 12 years after gastric bypass. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(12):1143-1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aminian A, Zajichek A, Arterburn DE, et al. Association of metabolic surgery with major adverse cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and obesity. JAMA. 2019;322(13):1271-1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mingrone G, Panunzi S, De Gaetano A, et al. Metabolic surgery versus conventional medical therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes. Lancet. 2021;397(10271):293-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aminian A, Al-Kurd A, Wilson R, et al. Association of bariatric surgery with major adverse liver and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with biopsy-proven nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. JAMA. 2021;326(20):2031-2042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sjöström L, Gummesson A, Sjöström CD, et al. Effects of bariatric surgery on cancer incidence in obese patients in Sweden (Swedish Obese Subjects Study). Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(7):653-662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schauer DP, Feigelson HS, Koebnick C, et al. Bariatric surgery and the risk of cancer in a large multisite cohort. Ann Surg. 2019;269(1):95-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adams TD, Stroup AM, Gress RE, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality after gastric bypass surgery. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2009;17(4):796-802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mackenzie H, Markar SR, Askari A, et al. Obesity surgery and risk of cancer. Br J Surg. 2018;105(12):1650-1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rustgi VK, Li Y, Gupta K, et al. Bariatric surgery reduces cancer risk in adults with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and severe obesity. Gastroenterology. 2021;161(1):171-184.e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lazzati A, Epaud S, Ortala M, et al. Effect of bariatric surgery on cancer risk. Br J Surg. 2022;109(5):433-438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang K, Luo Y, Dai H, Deng Z. Effects of bariatric surgery on cancer risk. Obes Surg. 2020;30(4):1265-1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Milinovich A, Kattan MW. Extracting and utilizing electronic health data from Epic for research. Ann Transl Med. 2018;6(3):42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Epic website . Organizations on the Care Everywhere Network. Accessed April 17, 2022. https://www.epic.com/careeverywhere/

- 18.Grambsch PM, Therneau TM. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika. 1994;81(3):515-526. doi: 10.1093/biomet/81.3.515 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Buuren S. Multiple imputation of discrete and continuous data by fully conditional specification. Stat Methods Med Res. 2007;16(3):219-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rubin DB. Inference and missing data. Biometrika. 1976;63(3):581-592. doi: 10.1093/biomet/63.3.581 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.VanderWeele TJ, Ding P. Sensitivity analysis in observational research. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(4):268-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haneuse S, VanderWeele TJ, Arterburn D. Using the E-value to assess the potential effect of unmeasured confounding in observational studies. JAMA. 2019;321(6):602-603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kyrgiou M, Kalliala I, Markozannes G, et al. Adiposity and cancer at major anatomical sites. BMJ. 2017;356:j477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fang Z, Song M, Lee DH, Giovannucci EL. The role of mendelian randomization studies in deciphering the effect of obesity on cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2022;114(3):361-371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murphy N, Jenab M, Gunter MJ. Adiposity and gastrointestinal cancers. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15(11):659-670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.MacKintosh ML, Derbyshire AE, McVey RJ, et al. The impact of obesity and bariatric surgery on circulating and tissue biomarkers of endometrial cancer risk. Int J Cancer. 2019;144(3):641-650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sinclair P, Brennan DJ, le Roux CW. Gut adaptation after metabolic surgery and its influences on the brain, liver and cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15(10):606-624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farey JE, Fisher OM, Levert-Mignon AJ, et al. Decreased levels of circulating cancer-associated protein biomarkers following bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2017;27(3):578-585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bhatt DL, Aminian A, Kashyap SR, et al. Cardiovascular biomarkers after metabolic surgery versus medical therapy for diabetes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(2):261-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stroud AM, Dewey EN, Husain FA, et al. Association between weight loss and serum biomarkers with risk of incident cancer in the Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery cohort. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2020;16(8):1086-1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anveden Å, Taube M, Peltonen M, et al. Long-term incidence of female-specific cancer after bariatric surgery or usual care in the Swedish Obese Subjects Study. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;145(2):224-229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schauer DP, Feigelson HS, Koebnick C, et al. Association between weight loss and the risk of cancer after bariatric surgery. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2017;25(suppl 2):S52-S57. doi: 10.1002/oby.22002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maruthur NM, Bolen S, Brancati FL, Clark JM. Obesity and mammography. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(5):665-677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Østbye T, Taylor DH Jr, Yancy WS Jr, Krause KM. Associations between obesity and receipt of screening mammography, Papanicolaou tests, and influenza vaccination. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(9):1623-1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Diagnosis Codes to Assist in Identifying Pre-existing Conditions that Could Disqualify Patients for Study Eligibility

eTable 2. Procedure and Diagnosis Codes to Assist in Identifying Different Types of Bariatric and Metabolic Surgical Interventions

eTable 3. Diagnosis Codes to Assist in Identifying Baseline Medical Conditions

eTable 4. Diagnosis Codes to Assist in Identifying Malignant Obesity-Associated Cancers (Primary End Point)

eTable 5. Diagnosis Codes to Assist in Identifying Any Type of Malignant Cancer (Secondary End Point)

eTable 6. Cancer-Specific Event Rates (%) per 1000 Person-Years of Follow-up for Each Cancer Type Stratified by Surgical and Nonsurgical Patients

eTable 7. E-value for the Effect of Bariatric Surgery on Study End Points (and its Upper Limit of 95% CI) in Fully-Adjusted Cox Models

eMethods. E-Value: Sensitivity Analysis for Unmeasured Confounding

eFigure 1. Hazard Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals for Bariatric Surgery Versus No Surgery from Fully-Adjusted Cox Models for Primary End Point for 5 Iterations of Index Date Random Sampling and 3 Different Matching Ratios (Total of 15 Data Sets for Sensitivity Analysis)

eFigure 2. 10-year Cumulative Incidence Estimates (Kaplan-Meier) of Seven Obesity-Associated Cancers Identified by Mendelian Randomization Approach