Abstract

Background

Globally, registered nurses (RNs) are increasingly working in primary care interdisciplinary teams. Although existing literature provides some information about the contributions of RNs towards outcomes of care, further evidence on RN workforce contributions, specifically towards patient-level outcomes, is needed. This study synthesized evidence regarding the effectiveness of RNs on patient outcomes in primary care.

Methods

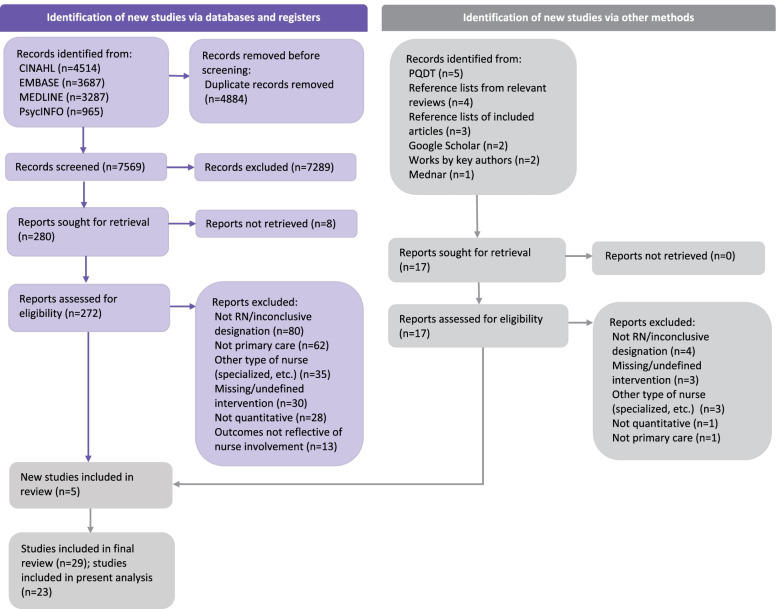

A systematic review was conducted in accordance with Joanna Briggs Institute methodology. A comprehensive search of databases (CINAHL, MEDLINE Complete, PsycINFO, Embase) was performed using applicable subject headings and keywords. Additional literature was identified through grey literature searches (ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, MedNar, Google Scholar, websites, reference lists of included articles). Quantitative studies measuring the effectiveness of a RN-led intervention (i.e., any care/activity performed by a primary care RN) that reported related outcomes were included. Articles were screened independently by two researchers and assessed for bias using the Integrated Quality Criteria for Review of Multiple Study Designs tool. A narrative synthesis was undertaken due to the heterogeneity in study designs, RN-led interventions, and outcome measures across included studies.

Results

Forty-six patient outcomes were identified across 23 studies. Outcomes were categorized in accordance with the PaRIS Conceptual Framework (patient-reported experience measures, patient-reported outcome measures, health behaviours) and an additional category added by the research team (biomarkers). Primary care RN-led interventions resulted in improvements within each outcome category, specifically with respect to weight loss, pelvic floor muscle strength and endurance, blood pressure and glycemic control, exercise self-efficacy, social activity, improved diet and physical activity levels, and reduced tobacco use. Patients reported high levels of satisfaction with RN-led care.

Conclusions

This review provides evidence regarding the effectiveness of RNs on patient outcomes in primary care, specifically with respect to satisfaction, enablement, quality of life, self-efficacy, and improvements in health behaviours. Ongoing evaluation that accounts for primary care RNs’ unique scope of practice and emphasizes the patient experience is necessary to optimize the delivery of patient-centered primary care.

Protocol registration ID

PROSPERO: International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews. 2018. ID=CRD42 018090767.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12913-022-07866-x.

Keywords: Effectiveness, Primary healthcare, Registered nurse, Primary care nursing, Systematic review, Outcomes, Patient measures

Background

Primary care is the foundation of a highly functioning health care system and provides comprehensive, patient-centered care that considers the needs and experiences of the individual patient, their families, and the well-being of the broader community [1]. Primary care providers are the first contact and principal point of continuing care for patients within the health care system, and coordinate other specialist care and services that patients may need [1, 2]. The delivery of primary care occurs across varied settings but is most frequently provided in a clinic and, increasingly, by interprofessional teams that may consist of family physicians, registered nurses (RNs), nurse practitioners, pharmacists, and other health professionals. In primary care settings, RNs function as generalists and provide a broad range of patient services across the lifespan, including preventative screening, health education and promotion, chronic disease prevention and management, and acute episodic care [3–6]. Specifically, family physicians and RNs represent a key collaborative relationship within these teams, contributing to strengthened primary care delivery and improvements in the comprehensiveness, efficiency, and value of care for patients [7–9]. Internationally, nurses are increasingly embedded in primary care settings and are recognized as the most prominent non-physician contributor to primary care teams, although the scope and speed of implementation in this area differs across countries [10, 11]. Primary care nursing in Australia is the fastest growing employment sector, with 63% of general practices employing a primary care nurse (and 82% of this group representing RNs) [12, 13]. The World Health Organization’s report [14] on the state of the world’s nursing workforce emphasizes the need to strengthen the integration of RNs into primary care, as well as the need for further research to evaluate their impact. Global workforce data are unavailable given the variability in scope of practice and role terminology, and the lack of available information across countries. A recent review of the international literature identified that titles used to refer to RNs in primary care vary across countries [15]. For instance, titles for this role in Canada are ‘family practice nurse’ and ‘primary care nurse’, whereas in Australia, the United Kingdom, and Netherlands this title is known as ‘general practice nurse’ [15]. For the purpose of this manuscript, ‘primary care RN’ will be used throughout.

Most research in this area to date has focused on describing the roles and activities of primary care RNs. A systematic review conducted by Norful et al. [5] synthesized 18 studies from eight countries related to primary care RNs and identified assessment, monitoring, and follow-up of patients with chronic diseases as fundamental roles of the primary care RN. In contrast, there have been a number of reviews conducted on the effectiveness of nurse practitioners in primary care [16–18]. It is imperative that primary care RNs also begin to demonstrate their contributions to patient care within this setting. Research examining RN effectiveness has primarily been conducted within the acute care and long-term care settings and focused on staffing, role enactment, and work environment. Within these settings, there is substantial evidence demonstrating the positive effects of RN staffing on improving care and reducing adverse outcomes for hospitalized patients [24, 25].

Furthermore, select countries including Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom have developed national standards of practice or competencies to define the scope and depth of practice for primary care RNs [4, 19–23]. National competencies for primary care RNs were recently published in Canada [7]. These competencies articulate the unique scope of practice and contributions to patient care for primary care RNs across six overarching domains, namely, (1) Professionalism, (2) Clinical Practice, (3) Communication, (4) Collaboration and Partnership, (5) Quality Assurance, Evaluation and Research, and (6) Leadership.

Theoretical foundation

Determining effectiveness normally requires an examination of an intervention (e.g., primary care nursing) on a particular outcome. Incorporation of the patient perspective offers a more complete understanding of the challenges patients face within our healthcare system, especially those with long-term chronic diseases. Measuring the patient experience, which is a strong predictor of quality and value of care, should be done systematically [26]. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Patient Reported Indicator Surveys (PaRIS) Conceptual Framework was developed through a comprehensive process involving extensive international collaborations and provides a roadmap and survey tools (i.e., patient and provider questionnaires) to focus the evaluation of health care interventions on patient-reported metrics [27]. This framework provides a fuller evaluation of performance by complimenting other metrics (e.g., system/cost outcomes), while also focusing attention on the needs of the patient. The main domains of the framework include: patient reported experience measures (PREMs), patient reported outcome measures (PROMs), and health behaviours (e.g., physical activity, diet, tobacco use, alcohol use). Within primary care, the PaRIS Framework can serve as a guide for routine collection of these outcomes to facilitate quality improvement and patient-centered care [27]. A growing body of research in this area has adapted the use of this model to serve as an organizational and methodological framework. For example, multiple studies have used this framework as a method of investigating the suitability and feasibility of questionnaire and survey instruments when addressing patient perspectives [28, 29] or in the evaluation of health-related quality of life measures from the patient’s perspective [30]. A recently published systematic review that explored the opportunities and challenges of routine collection of PREMs and PROMs data for melanoma care within primary care settings found that these measures can address important care gaps and facilitate research and assessment [31]. Similarly, a study employing qualitative methods found that the use of patient-reported measures by practitioners enhanced patients’ ability to self-manage, communicate, engage, and reflect during consultations [32]. A recent environmental scan of the PROMs landscape was conducted within Canada and internationally, indicating a lack of standardized programs for routine collection and reporting of patient outcomes. Consequently, the need for enhanced PROMs information has been identified as an area of high priority [33].

Purpose

Although existing literature provides some information about the contributions of primary care RNs towards outcomes of care, a systematic review synthesizing the effectiveness of the primary care RN workforce is needed. Prior to beginning the study, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Library of Systematic Reviews, and the Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) were searched and no existing registered protocols or previous systematic reviews on this topic were identified. Evaluating PREMs, PROMs, and health behaviours, as well as other patient-level outcomes, is necessary to accurately demonstrate the contribution of primary care RNs, hold them accountable for their care, and generate evidence to inform decisions and policies that impact their implementation and optimization [34, 35]. Therefore, the purpose of this systematic review is to summarize evidence examining primary care RNs’ impact on patient outcomes, including physiologic changes (via biomarkers), PREMs, PROMs, and health behaviours.

Methods

Design

A systematic review of effectiveness was conducted using JBI Systematic Review methodology [36] and findings were reported in accordance with the 2009 (and where possible, the 2021) Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) framework [37, 38]. Covidence software was used to manage and organize the literature [39] and enable a team approach for study and data review. The protocol for this systematic review is registered on PROSPERO (registration ID CRD42018090767). This paper presents a summary of findings from studies that report on patient outcomes, including biomarkers, PREMs, PROMs, and health behaviours. A full description of the methods and findings from studies that measured care delivery and system outcomes are reported in the companion paper “Effectiveness of Registered Nurses on System Outcomes in Primary Care: A Systematic Review” [40].

Search strategy

The search strategy aimed to include both published and unpublished literature. Following a limited search in CINAHL and Medline that identified optimal search terms, two members of the research team performed a comprehensive search of relevant electronic databases (see Supplementary File 1). Grey literature was identified using ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, MedNar, Google Scholar, the websites of relevant nursing organizations (e.g., International Council of Nurses, Community Health Nurses of Canada), and reference lists of included articles. There were no location or publication date restrictions on search criteria. Studies published in any year up to and including the date of article retrieval (January, 2022) were considered. Ongoing searches for grey literature included studies with publication dates up to January, 2022.

Inclusion criteria

Studies considered for inclusion reported on any quantitative study published in English with outcomes that directly measured, or were related to, an intervention attributable to a primary care RN. Only studies focused on RNs or equivalent (e.g., practice nurse, general nurse) [15] were included; if the RN designation was unclear or could not be determined based on the region of publication, the study was excluded. Studies that involved primary care RNs who underwent considerable advanced/focused training or those that exclusively examined structural variables were excluded. Full details regarding inclusion criteria are published in the companion paper [40].

Screening

Reviewers included two study authors (DR and JL) and two trained research assistants (AR and OP). All identified titles and abstracts were screened independently by two reviewers for potential study eligibility. Two reviewers independently screened full-text articles for relevance, applying pre-established eligibility criteria. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion, or by a third reviewer.

Risk of bias

The risk of bias and quality of each study was assessed using the Integrated Quality Criteria for Review of Multiple Study Designs (ICROMS) tool (see scoring matrix located in Supplementary File 2) [41]. All full-text articles that met eligibility criteria were appraised for quality by two independent reviewers. All studies that met inclusion/exclusion criteria also met the minimum ICROMS score to be included in the review.

Data extraction and synthesis

All eligible full-text studies underwent data extraction using a tool pre-designed and tested by the research team and based on the Cochrane Public Health Group Data Extraction Template [42]. Data extracted from the articles included: country and year of publication, study aim and design, description of primary care setting, patient sample sizes and demographics, details of study intervention and primary care RN involvement/role, outcome measures used to evaluate these interventions, and study results. To address the broad range of terms and descriptors used across included studies (e.g., traditional care, standard care, basic support, care delivered by anyone other than a primary care RN) and to provide clarity in the presentation of our results, we refer to all control groups as “usual care” or the “comparator group”. Outcomes were grouped in accordance with the OECD PaRIS Conceptual Framework Classification [27] into one of three categories defined by this model (i.e., PREMS, PROMs, health behaviours), and an additional category added by the research team (i.e., biomarkers) (see Table 1). Biomarkers consist of outcomes related to changes in patient health status as measured by clinical assessment (e.g., hemoglobin A1c [HbA1c] values, blood pressure, body weight). PREMs are defined as patient experience indicators related to health care access, autonomy in care, and overall satisfaction with care received, and are often assessed through self-report questionnaires or population-based surveys [27]. These outcomes can be summarized further based on patient experiences surrounding access (e.g., first point of contact), comprehensiveness of care, self-management support, trust, and overall perceived quality of care. PROMs are described as outcomes relating to a patient’s self-reported physical, mental, and social health status and can be categorized as either generic or condition-specific and applied to a broad patient population [27]. Outcomes identified on this level can be further categorized into functional status (e.g., disability, physical, mental, social function), symptoms, and health-related quality of life. The remaining outcomes were categorized according to the health behaviors classification, which includes lifestyle behaviors and actions that can contribute to a patient’s overall health status (e.g., physical activity, smoking status, dietary intake) [27]. Due to the diversity of included designs, interventions, and outcomes across studies, narrative synthesis was used to present study findings.

Table 1.

Classification of patient outcomes measured in each study based on the OECD PaRIS Conceptual Framework [27]

| Aubert et al., 1998 | Aveyard et al., 2007 | Bellary et al., 2008 | Byers et al., 2018 | Caldow et al., 2006 | Cherkin et al., 1996 | Coppell et al., 2017 | Desborough et al., 2016 | Faulkner et al., 2016 | Gallagher et al., 1998 | Halcomb, Davies, et al., 2015 | Halcomb, Salamonson, et al., 2015 | Harris et al., 2015 | Harris et al., 2017 | Iles et al., 2014 | Karnon et al., 2013 | Marshall et al., 2011 | Moher et al., 2001 | O'Neill et al., 2014 | Pearson et al., 2003 | Pine et al., 1997 | Waterfield et al., 2021 | Zwar et al., 2010 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biomarkers | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||

| PREMs | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||||

| PROMs | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||||

| Health Behaviours | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

Results

Figure 1 presents a PRISMA diagram outlining the results of the literature search.

Fig. 1 .

PRISMA Diagram of Literature Search. *This paper reports on studies that measured patient outcomes. Findings from studies that measured care delivery and system outcomes are reported in the companion paper "Effectiveness of registered nurses on system outcomes in primary care: a systematic review" [40]

Study characteristics

Of the 29 articles included in the final review, 23 reported on patient outcomes (included in the present analysis) [40]. Table 2 presents a detailed summary of the study characteristics for each of these articles. Studies were published between the years 1996–2021 and conducted in the United Kingdom (n = 9), United States (n = 6), Australia (n = 5), and New Zealand (n = 3). Study designs included randomized controlled trials (n = 9), observational (n = 8) (e.g., survey, secondary data analysis), cohort (n = 1), non-controlled (n = 2) and controlled before-after (n = 1), and two studies with mixed-methods designs that combined a non-controlled before-after with a non-randomized controlled trial (n = 1) or with an observational design (n = 1). Sample sizes ranged from 81–2850 patients. Quality scores, as assessed by the ICROMS tool, varied between studies. Four studies were scored at the minimum threshold for their study design [46, 56, 61, 65], six studies scored 1–2 points above threshold [44, 45, 48, 49, 53, 57], and thirteen studies exceeded the minimum cut-off score by 3 or more points [43, 47, 50–52, 54, 55, 58–60, 62–64].

Table 2.

Literature review table of study characteristics (n = 23)

| Author, Year, Country | Aim | Design | Sample | Intervention and RN Involvement | Primary Care Setting Type | ICROMS Quality Appraisal Score [1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Aubert et al., 1998 [43] USA |

To compare diabetes control in patients receiving nurse case management and patients receiving usual diabetes management in a primary care setting | Randomized controlled trial | Prudential HealthCare health maintenance organization members with diabetes (n = 138 patients were randomized; n = 100 provided 12-month follow-up data) |

Nurse case management for patient diabetes control (diabetes management delivered by a RN case manager) v. usual diabetes care (control) One RN provided the intervention for this study; RN had 14 years of clinical experience and was a certified diabetes educator RN provided intervention with support - met at least biweekly with the family medicine physician and the endocrinologist to review patient progress and medication adjustments. RN was trained in the delivery of care while primary care providers oversaw clinical decisions |

2 primary care clinics within a group-model health maintenance organization in Jacksonville, Florida | 25 |

|

Aveyard et al., 2007 [53] UK |

To examine whether weekly behavioral support increased smoking quit rate relative to basic support; and to assess whether primary care nurses can deliver effective behavioral support | Randomized controlled trial | Adults who smoked ≥ 10 cigarettes per day (n = 925) were recruited between July 2002 - March 2005 |

Smoking cessation support provided by a PN (weekly behavioural support [one additional visit and two additional telephone calls]) v. basic, less frequent support provided by a PN (control) Number of PNs and additional characteristics were not indicated PN provided intervention alone. All PNs were provided with mentoring and training on the application of smoking cessation support, as well as information on the use of nicotine replacement therapies |

26 general practices in two urban counties in the UK | 23 |

|

Bellary et al., 2008 [44] UK |

To investigate the effectiveness of a culturally sensitive, enhanced care package for improvement of cardiovascular risk factors in patients of South Asian origin with type 2 diabetes | Cluster randomized controlled trial | Adult patients of South Asian origin with type 2 diabetes (n = 1486) |

Enhanced management care for type 2 diabetes tailored to the needs of the South Asian community (enhanced care [additional time with PN + support with link worker and diabetes-specialist nurse] v. standard care/control [routine PN-led diabetes clinics guided by prescribing algorithm]) Number of PNs not indicated; all were formally trained in diabetes management PN provided intervention with support of diabetes nurse specialist, link worker, and physician. PNs worked with primary care physicians to implement the protocol and encourage appropriate prescribing, provide patient education, and achieve health targets |

21 inner-city practices in 2 cities in the UK with a high-population of South Asian patients. Patients were randomly allotted to the intervention or the control group between March 2004 - April 2005 | 24 |

|

Byers et al., 2018 [54] USA |

To compare smoking cessation rates between nurse-led and physician-led preventative/wellness visits | Observational; retrospective secondary analysis of a de-identified electronic medical record data set | Medicare beneficiaries who received wellness visits or non-Medicare patients who received MD-led annual physicals and identified as smokers (n = 218) between January 2011 - December 2015 |

Nurse-led wellness visits focused on smoking cessation carried out by RNs v. same intervention carried out by GPs Nurses in the RN-led group were non-advanced practice RNs. Due to limited resources and competing clinical demands, efforts to implement Medicare annual wellness visits occurred gradually and included RNs in 4 of the 6 clinics RN provided intervention alone, carrying out point-of-care screening and various other preventative wellness activities |

Network of 6 primary care clinics in Arkansas, USA | 20 |

|

Caldow et al., 2006 [64] UK |

To assess patients’ satisfaction, attitudes, and preferences regarding PN v. doctor consultations for minor illness as first-line contact | Observational; survey and telephone interviews | Large random sample of registered patients over 18 years of age (n = 2949 questionnaires were mailed out; n = 1343 [45.5%] were returned completed) |

National survey of patient satisfaction, attitudes, and preferences regarding PN care v. doctor consultation Number of PNs and additional characteristics were not indicated. Data obtained from postal questionnaire survey including discreet choice experiment, followed by telephone interviews Practices were scored and ranked according to the degree of extended nursing role; the 20 most and 20 least extended practices according to the criteria were invited to participate Organizational-level involvement; practices had PNs with varying roles (traditional and extended) and patients were surveyed about their interactions and attitudes/preferences |

433 general practices, including traditional and extended PN roles in Scotland | 21 |

|

Cherkin et al., 1996 [57] USA |

To evaluate the impact of a proactive and patient-centered educational intervention for low back involving a nurse-intervention group in comparison with two lower impact treatment models | Randomized controlled trial | Patients aged 20–69 years of age visiting the clinic for back pain, low back pain, hip pain, or sciatica (n = 294) were randomly allocated to one of 3 groups; n = 286 provided complete follow-up data |

Educational intervention for back pain carried out by a RN (usual care) v. usual care + educational booklet (intervention arm 1) v. usual care + session with RN + educational booklet (intervention arm 2); outcomes assessed at 1, 3, 7, and 52 weeks Study involved 6 female RNs with at least 20 years of clinical experience. Study RNs received 9 h of training on the management of back pain RN provided intervention alone. The intervention involved a 15–20-min educational session, including the booklet and a follow-up telephone call 1–3 days later |

Suburban primary care clinic in western Washington state, belonging to a staff model Health Maintenance Organization | 24 |

|

Coppell et al., 2017 [50] New Zealand |

To examine the implementation and feasibility of a six-month multilevel primary care nurse-led prediabetes lifestyle intervention compared with current practice for patients with prediabetes | Pragmatic, non-randomized controlled before-after; convergent mixed methods design | Non-pregnant adults aged ≤ 70 years with newly diagnosed prediabetes, a BMI above 25, not prescribed Metformin, and able to communicate in English were sent a study invitation letter between August 2014 -April 2015. One-hundred fifty-seven patients were enrolled and n = 133 patients were retained at the six-month follow-up |

Multi-level primary care nurse-led prediabetes lifestyle intervention involving a structured dietary intervention tool v. usual care (control) Study involved 11 RNs and community nurses. Additional characteristics were not indicated RN provided intervention with support of dietician and liaison nurse. RNs delivered the clinic portion of the intervention (30-min dietary session and evaluation using a validated dietary measurement tool at baseline, 2–3 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months) while community nurses carried out the group education sessions outside of the clinic |

4 intervention general practices and 4 control general practices located in 2 neighboring New Zealand cities; all practices employed a primary care nurse | 26 |

|

Desborough et al., 2016 [62] Australia |

To examine the relationships between specific general practice characteristics, nurse consultation characteristics, and patient satisfaction and enablement | Observational; cross-sectional survey | Patients in general practice who had consulted with a nurse, regardless of health condition, and were 16 years or older, or 5 years or younger (n = 678) between September 2013 - March 2014 |

Nursing care in general practice based on specific practice characteristics and nurse consultation characteristics (measured by patient surveys and interviews with nurses, patients, and practice managers) Study involved 47 baccalaureate-prepared RNs and 3 diploma-prepared enrolled nurses across all practices (average of 2.5 RNs per practice) with a mean of 3 years of experience RN provided intervention alone. The majority of consultations were for clinical care, preventative health care, and chronic disease management |

21 general practice locations in an Australian capital territory, with an average ratio of 3–4 GPs: 1 nurse per clinic | 22 |

|

Faulkner et al., 2016 [55] UK |

To compare differences in smoking cessation treatment delivered by PNs or HCAs on short and long-term abstinence rates from smoking | Cohort study using longitudinal data from a previously conducted randomized controlled trial | Current smokers aged 18–75 years who are fluent in English, not enrolled in another formal smoking cessation study or program, and not using smoking cessation medications (n = 602) |

Smoking cessation support provided by PNs v. HCAs to compare and assess effects on short and long-term smoking abstinence rates on patients Number of PNs and additional characteristics were not indicated PNs provided intervention alone (and were compared to same intervention provided by HCAs). Patients in both groups received an initial consultation, followed by a program-generated cessation advise report tailored to the smoker and a 3-month program of tailored text messages sent to their mobile phone |

32 general practices in East England; 8 of which were in the top 50% of deprived small geographical areas in England | 21 |

|

Gallagher et al., 1998 [65] UK |

To determine the impact of telephone triage, conducted by a PN, on the management of same day consultations in a general practice | Observational (cross-sectional) and uncontrolled before-after using prospective telephone and practice consultation data + patient postal questionnaire | All patients in practice (n = 1250 consultations with diagnosis), in which consultations were recorded between August - October 1995 |

Nurse operated telephone consultations/triage There was a total of 4 PNs working in the practice; the telephone consultation/triage service was managed by a single nurse who had 15 years of experience and was familiar with managing acute illnesses and conducting telephone consultations PN provided intervention with support of physician and receptionist. Patients who telephoned requesting to see a doctor on the same day were put through to the PN, where they would manage the patient’s problem over the phone or arrange for a same-day appointment with either themselves or the GP |

Individual general practice in an urban city in England that contains physicians, PNs, and admin staff | 16; 22* |

|

Halcomb, Davies, & Salamonson, 2015 [63] New Zealand |

To understand the relationship between consumer demographics and their satisfaction with PN services | Observational; survey | Patients with sufficient fluency in English to complete the survey form and provide consent (n = 1505) were recruited through email invitation from December 2010 - December 2011 |

PN-led care in general practice as assessed by a 64-item self-report survey tool completed by patients Number of PNs not indicated, however each participating practice employed between 1–11. All participating nurses were female and had an average of 22 years of experience, a mean age of 49 years, and worked between 8–44 h/week PN provided intervention alone by performing a range of services within primary care nursing scope of practice- vaccination, blood pressure measurement, cardiovascular assessments, treatment of minor illnesses/injuries, cervical smears and sexual health check-ups, tissue collection, lung function tests, etc |

20 general practices in New Zealand, representing a mixture of urban and rural locations | 21 |

|

Halcomb, Salamonson, & Cook, 2015 [45] Australia |

To evaluate consumer satisfaction and comfort with chronic disease management by nurses in general practice | Observational; survey | A convenience sample of all patients in practice (n = 81) who received services from a participating PN |

Chronic disease services delivered by PNs in general practice, as measured by a 33-item survey tool Number of PNs and additional characteristics were not indicated PN provided intervention alone; after services were delivered, patients were provided with an information package containing a survey to evaluate their encounter |

8 general practices that contained GPs and PNs working collaboratively in New South Wales, Australia | 17 |

|

Harris et al., 2015 [59] UK |

To determine whether a primary care nurse-delivered complex intervention increased objectively measured step-counts and moderate to vigorous physical activity when compared to usual care | Cluster randomized controlled trial | 60–75-year-olds who could walk outside and had no contraindications to increasing physical activity (n = 298 patients from n = 250 households) were recruited between 2011 - 2012 from a random sample of eligible households |

Individually-tailored PN consultations centered around physical activity (four physical activity consultations with nurse) v. usual care (no trial contacts other than for data collection at baseline, 3 months, and 12 months) (control) Number of PNs and additional characteristics were not indicated PN provided intervention alone; physical activity consultations incorporated behavioural change techniques, step-count and accelerometer feedback, and an individual physical activity plan |

3 general practices located in Oxfordshire and Berkshire, UK | 28 |

|

Harris et al., 2017 [60] UK |

To evaluate and compare the effectiveness of pedometer-based and nurse-supported interventions v. postal delivery intervention or usual care on objectively measured physical activity in predominantly inactive primary care patients | Cluster randomized controlled trial | A random sample of 45–75-year-olds without contraindications to increasing moderate to vigorous physical activity (n = 956 with at least one follow-up) were sent postal invitations between September 2012 - October 2013 |

Nurse-supported individually-tailored physical activity consultations as measured by patient pedometer activity (nurse-supported pedometer intervention [arm 1]) v. postal pedometer intervention [arm 2] v. usual care [control]) Number of PNs and additional characteristics were not indicated PN provided intervention alone; nurse-supported intervention group involved a pedometer, patient handbook, physical activity diary, and three individually tailored PN consultations offered at 1, 5, and 9 weeks |

7 general family practices with an ethnically and socioeconomically diverse population in South London | 26 |

|

Iles et al., 2014 [46] Australia |

To determine the economic feasibility of using a PN-led care model of chronic disease management in Australian general practices in comparison to GP-led care | Randomized controlled trial; cost-analysis | Patients > 18 years of age with one or more stable chronic diseases (type 2 diabetes, ischemic heart disease, hypertension) (n = 254) |

PN-led care model of chronic disease management (n =120) v. GP-led (usual care) care model (n =134) There were 2 PNs and 1–4 GPs involved in each practice over the 2-year study period PN provided intervention alone, working within their scope of practice and from protocols, rather than under supervision of GP; if patients in the PN-led group became unstable, they could be referred back to the GP-led group until their health re-stabilized |

3 general practices (urban, regional, rural) | 22 |

|

Karnon et al., 2013 [47] Australia |

To conduct a risk adjusted cost-effectiveness analysis of alternative applied models of primary health care for management of obese adult patients based on level of PN involvement (high-level PN practice v. low-level PN practice v. physician-only model) | Observational; risk-adjusted cost-effectiveness analysis | Patients with BMI < 30 prior to October 1, 2009, had at least three visits within the last 2 years, at least two recorded measures of BMI, and aged 18–75 years (n = 383 patients were recruited, n = 208 were excluded, n = 150 patients included in the analysis) who gave consent for researchers to access their medical data |

PN involvement in the provision of clinical-based obesity care. Models of care classification were based on percentage of time spent on clinical activities: high-level model (n = 4), low-level model (n = 6), physician-only model (n = 5; due to low number of eligible patients in the physician-only model, data were not presented) Number of PNs were not indicated, although results indicate that high level practices had a non-significantly higher number of FTE PNs than low level practices (0.35 compared to 0.25 for low level practices, p = 0.34); PNs had varying scopes of practice in clinics, which was informed by survey responses which assessed their clinical-based activities No specific nurse intervention; study examined nursing care related to obesity in general (e.g., education, self-management advice, monitoring clinical progress, assessing treatment adherence) |

15 of 66 general practices within the Adelaide Northern Division of General Practice with varying levels of PN involvement | 22 |

|

Marshall et al., 2011 [51] New Zealand |

To assess patients’ experiences and opinions of the Nurse-Led Healthy Lifestyle Clinic Project as well as recorded clinical outcomes, and to assess how successfully the clinics engaged the target populations | Observational; clinical outcome data and cross-sectional surveys | Patients with a specifically diagnosed condition relevant to the nurse-led lifestyle clinics (diabetes, smoking cessation, women’s health, cardiovascular, respiratory, diet/nutrition) (n = 2850) |

Nurse-led healthy habits lifestyle clinics for patients with or at risk of chronic disease within targeted populations with known health inequalities 115 RNs in total participated; in each clinic the nurses had their own patient caseload. Clinical outcome data were obtained from individuals who participated in the clinics (n = 2850) and patient satisfaction surveys (n = 424) RN provided intervention alone, however, in some cases patients were referred to other professionals when warranted. RNs delivered care using a holistic health approach defined by the patients’ needs. Clinical outcome data was collected on the first and last day of clinic attendance |

17 practices (3 Hauora, 2 community, and 12 general practices) served by the Primary Healthcare Organization | 20 |

|

Moher et al., 2001 [52] UK |

To assess the effectiveness of three different methods for improving the secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in primary care (audit and feedback; recall to a GP; recall to a nurse clinic) | Pragmatic, unblinded, cluster randomized controlled trial comparing three intervention arms | Patients aged 55–75 years with established coronary heart disease (n = 1906) as identified by computer and paper health records were recruited from 1997 - 1999 |

Secondary prevention care of patients with coronary heart disease delivered at three levels (i.e., audit and feedback; GP recall; nurse recall) Number of PNs in study unknown- all practices employed at least 1 PN; additional characteristics not identified PN provided intervention with support of the trial’s nurse facilitator, who gave ongoing support to the practices in setting up a recall system for review of patients with coronary heart disease. The nurse recall and GP recall groups employed the same intervention |

21 general practices in Warwickshire that employed PNs, but were not already running nurse-led clinics | 26 |

|

O’Neill et al., 2014 [48] USA |

To assess expanded CPS and RN roles by comparing blood pressure case management between CPS and physician-directed RN care in patients with poorly controlled hypertension | Observational; non-randomized, retrospective comparison of a natural experiment | Patients that had face-to-face or telephone appointments with a RN case manager for poorly controlled hypertension with either physician-directed or CPS-directed clinical decision making at the index encounter (n = 126) |

Patient hypertension care delivered by CPS-directed RN case management as an alternative to physician-directed RN case management Number of RNs and additional characteristics were not indicated RN provided intervention with support of either CPS or physician; RNs assessed patients independently and presented the case to either a CPS or a physician, if the hypertension continued to be poorly controlled. The RN communicated any changes in the plan to the patient |

A large Midwestern Veteran’s Affairs Medical Center that utilizes team-based care | 18 |

|

Pearson et al., 2003 [61] USA |

To apply the principles from the Kaiser Permanente model for depression treatment towards the development and implementation of a primary care PN telecare program | Uncontrolled before-after | Patients aged 21–64 years, diagnosed with major depressive disorder, depressive disorder NOS with severe symptoms, or dysthymic disorder, were experiencing a first or new episode of depression, and were prescribed an SSRI (n = 177 patients enrolled; n = 102 analyzed at six-month follow-up) |

Nurse telecare case management program based on the principles from the Kaiser Permanente model for patients with diagnosed depression Study consisted of 12 RNs and 2 LPNs involved in the telephone follow-up portion; additional characteristics not identified Organizational-level intervention; providers consisted of 39 physicians, 6 NPs and 5 physician assistants. Telephone follow-up was provided by RNs alone, however, they could consult with a supervising psychiatrist on an as-needed basis |

13 primary care practices in Maine’s urban centers of Augusta, Bangor, Lewiston, and Portland | 22 |

|

Pine et al., 1997 [49] USA |

To evaluate the effect of a nurse-based intervention for patients with high total cholesterol levels in a community practice | Non-controlled before-and-after clinical trial (pre-post study) followed by a non-randomized controlled trial (matching study) | One hundred twenty-three patients agreed to participate. Forty-one were excluded from the final analysis. The final sample consisted of n = 82 white patients with total cholesterol higher than 6.21 mmol/L |

Counseling provided by nurses to patients diagnosed with hypercholesterolemia using the Eating Pattern Assessment Tool and handouts with food advice Study involved 2 RNs; additional characteristics not identified RN provided intervention alone; in the pre-post study, RNs provided 5 counseling visits (1 month after referral, and at 3, 5, 7, and 12 months) to patients, which were focused on nutritional education and physical activity. In the follow-up matching study, intervention patients who attended 2 or more counseling sessions were matched with other patients in the practice |

Large multi-specialty group suburban primary care practice in Minneapolis | 23; 24* |

|

Waterfield et al., 2021 [58] UK |

To determine whether primary care nurses with no prior experience can, after training, provide effective supervised PFMT, when compared to PFMT given by a urogynaecology nurse specialist and that of usual care |

Randomized controlled trial |

Sample consisted of 337 asymptomatic women with weak pelvic floor muscles (Modified Oxford Score 2 or less) in a randomly sampled survey. Two hundred forty women aged 19 - 76 (median 49) years were recruited |

PFMT delivered to patients with weak pelvic floor muscles at three levels: primary care nurse-delivered training (arm 1) v. urogynaecology nurse specialist training (arm 2) v. usual care (no training) Number of primary care nurses involved and additional characteristics were not indicated; at least one primary care nurse from each practice participated Primary care nurse provided intervention alone; the primary care nurse intervention group were provided training materials related to pelvic floor assessment and techniques involved in teaching PFMT. Primary care nurses taught patients a PFMT regimen to perform 3–6 times per day for 3 months and used a perineometer to assess pelvic floor strength at baseline and 3 months |

11 primary care/general practices, covering urban and rural settings in South West England | 27 |

|

Zwar et al., 2010 [56] Australia |

To examine the impact of PN-delivered behavioral support on smoking cessation rates as well as the feasibility and acceptability of this model to patients, PNs, and GPs | Non controlled pre- and post-study using mixed methods | A convenience sample of smokers (n = 498 initial; n = 378 at 6-month follow-up) were recruited during nurse appointment in general practice |

Nurse-delivered smoking cessation counseling Study involved 31 PNs and all practices included in study employed at least 1 PN; additional characteristics not identified PNs took a leading role in providing counseling but were supported by the GPs from participating practices; GPs identified smokers interested in quitting and referred them to the PN for a series of weekly counseling visits of approximately 30-min duration over 4 weeks |

19 general practices in South West Sydney and a nearby rural area, representing 2 Divisions of General Practice | 22 |

*Mixed methods study consisting of multiple designs; separate ICROMS quality appraisal scores were generated for each study type; RN registered nurse, PN practice nurse, MD medical doctor, BMI body mass index, FTE full-time equivalent, HCA health care assistant, GP general practitioner, CPS clinical pharmacy specialist, NP nurse practitioner, NOS not otherwise specified, SSRI selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; LPN licensed practical nurse, PFMT pelvic floor muscle training

Overview of RN interventions

The nature of interventions examined in this review differed across studies. The most common interventions were related to chronic disease prevention and management, specifically, case management or targeted chronic disease management care (e.g., diabetes, obesity, hypertension, hypocholesteremia) (n = 7) [43–49] and primary and secondary preventative care for patients at risk of chronic disease (e.g. prediabetes, coronary heart disease) (n = 3) [50–52]. Other studies examined primary care RN-delivered smoking cessation support (n = 4) [53–56], back pain education and management [57], pelvic floor muscle training [58], consultations aimed at increasing patient physical activity levels [59, 60], and a telecare program for patients with diagnosed depression [61]. Four studies examined the impact of RN care in general (at an organizational-level); three of which focused on consultations with patients in general practice [62–64] and another which examined the impacts of a nurse-operated telephone consultation/triage service [65].

In thirteen studies, primary care RNs carried out the intervention independently without the support of other staff/providers [45, 46, 49, 51, 53–55, 57–60, 62, 63], and in 10 studies, they carried out the intervention interdependently, in collaboration with health care providers (e.g., physicians, clinical pharmacy specialists [CPS], dieticians) or members of the research team (e.g., trial nurse facilitator) [43, 44, 47, 48, 50, 52, 56, 61, 64, 65]. Three of these 10 studies involved evaluating RNs at the general practice-level and therefore are assumed to be evaluating an interdependent role involving support of other health care providers [47, 61, 64]. The presence and type of comparator group also differed across study designs. Specifically, five of the included studies compared a nurse-led intervention to the same intervention led by other health care providers [46, 52, 54, 55, 58]. Other studies compared nurse-led interventions with that of ‘usual care’ not associated with nurse involvement (n = 4) [43, 50, 57, 60], or with ‘usual care’ that was associated with reduced or alternative levels of nurse involvement (n = 5) [44, 49, 53, 56, 59]. The remaining studies examined the effectiveness of a primary care RN-delivered intervention on specific outcomes of care using an observational or before-after design (n = 5) [48, 51, 61, 62, 65], or did not contain a specific intervention, but rather, examined the impact of varying roles and practice characteristics of the primary care RN in general practice (n = 4) [45, 47, 63, 64].

Overview of outcomes

A total of 46 patient outcomes were identified across included studies (Table 3). Physiologic disease control outcomes, which were measured via biomarkers, included quality of care for diabetes (e.g., HbA1c, fasting blood glucose) [43, 44, 50, 51], obesity (e.g., body mass index [BMI], waist circumference) [44, 47, 50, 51, 59, 60], pelvic floor strength and endurance [58], hypercholesterolemia (e.g., total cholesterol) [49], and hypertension (e.g., blood pressure) [43, 44, 48, 50, 51]. Patient experience outcomes identified under the PREMs category included patient satisfaction with access to care (RN versus physician as first point of contact) [64], quality of self-management support (e.g., smoking cessation counseling, chronic disease services) [56, 62], comfort/trust with primary care RN roles [45], and overall satisfaction or perceived quality of care with provider consultations, treatment, or advice/support received [45, 51, 55, 57, 63, 65]. Patient reported outcomes identified within the PROMs category consisted of physical and social functional status [43, 57], level of disability (e.g., activity levels, bed rest, work loss) [57, 61], changes in self-reported anxiety, depression, or pain [59–61], adverse health events (e.g., falls, fractures, severe hypoglycemia) [43, 59, 60], and health-related qualify of life (e.g., physical activity, social activity) [43, 46, 51, 52, 60]. Lastly, outcomes grouped under the health behaviors classification included reduction and/or cessation of tobacco use [51, 53–56], changes to physical activity (e.g., level of aerobic exercise, daily step count) [51, 57, 59, 60], and improvements in dietary intake [49].

Table 3.

Literature Review Table – Description of Patient Outcomes and Study Results

| Author, Year, Country | Description of Outcome | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Biomarkers | ||

|

Aubert et al., 1998 [43] USA |

Changes in HbA1c value and other clinical markers related to diabetes management (fasting blood glucose, medication type and dose, body weight, blood pressure, lipid levels) after 12 months |

The intervention group had a greater decrease in HbA1c values than did the usual care group. The average change in HbA1c value was -1.7 percentage points in the intervention group and -0.6 percentage points in the usual care group (difference -1.1, 95% CI: -1.62 to 0.58; p < 0.001). Patients in the intervention group had a greater decrease in fasting blood glucose than the usual care group (-48.3 mg/dL v. -14.5 mg/dL; difference -33.8, 95% CI: -56.12 to 11.48; p = 0.003); however, other measures were not significant The results show that a RN case manager, in association with primary care physicians and an endocrinologist, can help improve glycemic control in diabetic patients in a group-model health maintenance organization |

|

Bellary et al., 2008 [44] UK |

Changes in type 2 diabetes health markers (blood pressure, total cholesterol, HbA1c) after 2 years Changes in waist circumference, BMI, microalbuminuria, plasma creatinine, Framingham CHD risk after 2 years |

The study produced only modest clinical outcomes when comparing the two groups in diastolic blood pressure (-1.91, 95% CI: -2.88 to -0.94 mm Hg; p = 0.0001) and mean arterial pressure (1.36, 95% CI: -2.49 to -0.23 mm Hg; p = 0.018); other outcomes (total cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, HbA1c) were not significant across the two groups. Across both arms of the study over the 2-year period, systolic and diastolic blood pressure decreased significantly and there was a small, but non-significant, reduction in HbA1c (-0.04%, 95% CI: -0.04 to -0.13; p = 0.29). There were no significant differences between groups for waist circumference, microalbuminuria, plasma creatinine or CHD risk score. BMI was significantly increased in the intervention group (p < 0.0001) Evidence suggests that intensive PN-led management can improve outcomes in type 2 diabetes, although this requires further development |

|

Coppell et al., 2017 [50] New Zealand |

Between-group changes to diabetes health markers (weight, HbA1c, waist circumference, BMI, blood pressure, lipids, urate, liver enzymes) after 6 months |

The intervention group lost a mean 1.3 kg, while the control group gained 0.8 kg (2.2 kg difference; p < 0.001). Mean HbA1c, BMI, and waist circumference decreased in the intervention group and increased in the control group at 6 months, but differences were not statistically significant after 2 years. Implementation fidelity was high and the intervention was considered feasible to implement in busy general practice settings |

|

Harris et al., 2015 [59] UK |

Changes in patient BMI and fat mass at 3-month follow-up | There were no between-group differences in change to BMI (0.001 kg/m2, 95% CI: -0.17 to 0.18, p = 0.98) or fat mass (0.39 kg, 95% CI: -0.85 to 0.07; p = 0.10) at 3 months |

|

Harris et al., 2017 [60] UK |

Changes in patient fat mass, BMI and waist circumference at 3- and 12-month follow-up | Fat mass was slightly reduced at 12 months in both intervention groups, but these differences did not differ significantly when the nurse group was compared to both postal intervention (p = 0.54) and usual care (p = 0.30). There was no change in BMI or waist circumference |

|

Karnon et al., 2013 [47] Australia |

Weight loss as defined by changes in BMI and weight, as well as reduction of obesity-related complications | Relative to low level involvement of practice nurses in the provision of clinical-based activities to obese patients, high level involvement was associated with significantly larger mean reductions in BMI (mean difference -1.10, CI: -0.45 to -1.75; p = 0.001) after 1 year, and non-significant improvements with respect to patients losing any, 5 and 10% of their baseline weight (p = 0.259) |

|

Marshall et al., 2011 [51] New Zealand |

Changes to blood pressure, weight, BMI, HbA1c, waist circumference, and cardiovascular risk between patient’s first and last visit | No significant changes in average blood pressure, weight, BMI, HbA1c, waist circumference and cardiovascular risk assessment were detected between baseline and follow-up visits |

|

O’Neill et al., 2014 [48] USA |

Changes in blood pressure between index and next consecutive visit |

Patients receiving CPS-directed RN case management had greater decreases in systolic blood pressure (-14 mm Hg) than those receiving physician-directed RN management (-10 mm Hg) (p = 0.04). After adjusting for time between visits, blood pressure, and prior stroke, there was no significant effect for provider type on systolic blood pressure change (p=0.24). There were no significant changes in diastolic blood pressure between groups. CPS-directed and physician-directed RN case management for hypertension demonstrated similar effects on blood pressure reduction, supporting an expanded role for CPS-RN teams |

|

Pine et al., 1997 [49] USA |

Changes in total cholesterol levels from first to final nurse visit (pre-post study) | Mean total cholesterol level decreased by 0.29 mmol/L (11.2 mg/dL) (4.3%) from the physician visit to the first nurse visit (p < 0.001) and 0.14 mmol/L (5.4 mg/dL) (2.1%) from the first nurse visit to the final nurse visit (p = 0.4). |

| Differences in total cholesterol levels between intervention and comparison groups (matching study) | The mean total cholesterol level of all patients improved significantly (p = 0.002). However, the improvement in intervention patients was no better than that of comparison patients | |

|

Waterfield et al., 2021 [58] UK |

Strength of pelvic floor muscle contraction | After 3 months, there was an increase in strength in both intervention groups compared with controls, with a median difference of 3.0 cmH20 higher for the primary care nurse group compared to the control group (95% CI: 0.3 to 6.0; p = 0.02), and 4.3 cmH20 for the urogynecology specialist group compared to the control group (95% CI: 1.0 to 7.3; p < 0.01). There was no difference between the primary care nurse and urogynecology nurse specialist groups (1.3; 95% CI: -2.0 to 4.7; p = 0.70) |

| Endurance of pelvic floor muscle contraction | There was an overall significant difference in endurance over the three groups at the end of the study (p < 0.001). Endurance of contraction for both of the intervention groups increased, while there was a slight decline for the controls from baseline endurance levels. Both the primary care nurse group and the urogynecology nurse specialist group had a significant increase in endurance compared to the control group at 3 months (p = 0.009 and p = 0.008, respectively) | |

| Patient-Reported Experience Measures (PREMs) | ||

|

Caldow et al., 2006 [64] UK |

Patient satisfaction with, opinion of, and preference for PN v. doctor consultation in primary care derived from questionnaire responses |

Women, younger people, and those who had a lower level of education were significantly less satisfied with the time spent if they had seen a GP compared with a PN (p < 0.05). Patients reported more satisfaction in this area in practices where the PN had an extended role (p < 0.001) Women and younger people had a significantly higher positive attitude towards, and perception of, PNs than did men and older people, respectively (p < 0001), and thought that a PN would know their family history as well as a GP would (p < 0.05). Younger and less well educated people perceived that a PN would know their medical condition (p < 0.001) as well as a GP would. The main perceived differences between GPs and PNs was academic ability and qualifications. This suggests that if PNs take on more roles that were previously only within GP scope of practice, patients would accept them, particularly if they receive information about nurse capabilities |

|

Cherkin et al., 1996 [57] USA |

Patient satisfaction evaluated based on 5 dimensions of subjects’ perceptions: perceived knowledge, worry, control, symptoms, and evaluation of care | The nurse intervention resulted in higher patient satisfaction than usual care (p < 0.05) and higher perceived knowledge (p < 0.001). There were no significant differences among the three groups in worry or symptoms at any follow-up interval and differences in knowledge were no longer significant at the 52-week follow-up |

|

Desborough et al., 2016 [62] Australia |

Patient scores on the Patient Enablement and Satisfaction Survey regarding nurse-led consultations |

The median total satisfaction score was 63, indicating that patients were either satisfied or very satisfied with nursing care. The median total patient enablement score was 2.25, indicating enablement levels of the same or less than the average, or that the questions were not applicable. Patients who had longer consultations were more satisfied (OR = 2.50, 95% CI: 1.43 to 4.35; p < 0.01) and more enabled (OR = 2.55, 95% CI: 1.45 to 4.50; p < 0.01) than those who had shorter consultations. Patients who had continuity of care (6 or more appointments) with the same nurse were more satisfied (OR = 2.31, 95% CI: 1.33 to 4.00; p = 0.01). Patients who attended practices where nurses worked with broad scopes of practice and high levels of autonomy were more satisfied (OR = 1.76, 95% CI: 1.09 to 2.82; p = 0.04) and more enabled (OR = 2.56, 95% CI: 1.40 to 4.68; p < 0.01). Patients who received care for the management of chronic conditions (OR = 2.64, 95% CI: 1.32 to 5.30; p < 0.01) were more enabled than those receiving preventive health care These results provide evidence of the importance of continuity of nursing care, adequate consultation time, and broad scopes of nursing practice and autonomy for patient satisfaction and enablement |

|

Faulkner et al., 2016 [55] UK |

Patient satisfaction with initial consultations (how clear they found the advice received on pharmacotherapies, the usefulness of cessation advice received, and satisfaction with consultation as a whole) as assessed by self-report questionnaire | Patients in both groups gave positive evaluations of the support they received; 93.2% of patients who saw HCAs and 91.2% who saw nurses said they were ‘happy’ or ‘extremely happy’ with the consultations, and 89.5% and 84.5% of patients who saw HCAs and nurses, respectively, reported finding the advice they received ‘useful’ or ‘extremely useful’. There were no statistically significant differences in any aspect of patient satisfaction by provider type |

|

Gallagher et al., 1998 [65] UK |

Patient satisfaction with nurse-led telephone advice as measured by a postal questionnaire | Most (n = 154; 88%) patients were very or fairly satisfied with nurse telephone advice. Only n = 10 (6%) were fairly or very dissatisfied |

|

Halcomb, Davies, & Salamonson, 2015 [63] New Zealand |

Patient perceptions of PNs based on responses to a 64-item self-report survey tool containing the General Practice Nurse Satisfaction scale |

Participants over 60 years and those of European descent were significantly less satisfied with the PN (p = 0.001); however, controlling for these characteristics, participants who had made < 4 visits to the PN were 1.34 times (95% CI: 1.06–1.70) more satisfied than the comparison group. The study also revealed a high level of satisfaction with PNs overall, with increased satisfaction associated with an increased number of visits Findings suggests that age, ethnicity and employment status were significant predictors of satisfaction levels, and that greater continuity with the PN (i.e., number of visits) strongly influences patient satisfaction with nursing services |

|

Halcomb, Salamonson, & Cook, 2015 [45] Australia |

Patient satisfaction and comfort levels of chronic disease services, based on survey data measuring patient satisfaction with nurse encounters and comfort with nurse roles in general practice |

Patient satisfaction with PN services was very high, with nearly two-thirds (n = 51; 63%) of consumers giving the maximum score. However, no statistically significant group differences were detected between patient characteristics, number of visits to the nurse and satisfaction ratings Patient self-reported comfort was also high (median: 72, range: 18–90). Patients who consulted PNs for diabetes-related conditions were almost three times more comfortable (38% v. 14%, p = 0.016) with their encounter than those who consulted for other chronic health conditions |

|

Marshall et al., 2011 [51] New Zealand |

Patient satisfaction with health and treatment as measured by a consultation satisfaction survey | Of the 424 patients who completed a survey, 91% indicated they agreed or strongly agreed with the questions that stated a positive aspect of their care. Questions 3–5 specifically asked if health had improved as a result of attending clinics; 92% indicated that they agreed or strongly agreed. Ninety-four percent of patients had a better understanding of their diagnosis, medication and treatment plan, and were more motivated to self-manage |

|

Zwar et al., 2010 [56] Australia |

Patient feedback on their satisfaction with the quality of smoking cessation support they received during a 6-month follow-up questionnaire | Of the 391 participants who responded to the patient satisfaction questionnaire, 385 (98%) rated the support provided as ‘helpful’ (19%) or ‘very helpful’ (79%). Less than 2% commented that the program could have been improved and all comments indicated that they may have been more successful if they had been able to have more sessions with the RN |

| Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) | ||

| Aubert et al., 1998 [43] | Episodes of severe hypoglycemia; emergency room and hospital admissions | There were no statistically significant differences between nurse case management groups and usual care for adverse events |

| Patient health-related quality of life as assessed by a questionnaire developed across four domains: 1) patient-perceived general health status, 2) patient-perceived physical dysfunction during the previous 30 days, 3) patient-perceived mental dysfunction during the pervious 30 days, and 4) patient-perceived functional incapacity during the previous 30 days for either mental or physical reasons | Both groups reported an improved perception of health status after 12 months, but patients in the nurse case management group were more than twice as likely to report improvement in health status score (mean change = 0.47) than the usual care group (mean change = 0.20) (difference=0.27; 95% CI: -0.03 to 0.57;p = 0.02) | |

|

Cherkin et al., 1996 [57] USA |

Physical and social function as measured by a modified version of the Roland Disability Questionnaire, including questions that pertained to back and leg pain Disability as measured by an adaptation to the National Health and Interview Survey, which was implemented at 1, 3 and 7 weeks |

There was no statistically significant increase in function or decreases in disability. The proportion of subjects reporting any days of limited activity, bed rest, or work loss resulting from their back pain was similar in all groups at each follow-up interval |

|

Harris et al., 2015 [59] UK |

Changes to patient self-reported levels of depression, anxiety, and pain as measured by questionnaire responses at 3 and 12 months | There were no statistically significant between-group differences in mean scores of depression, anxiety, or pain at 3 or 12 months |

| Falls, fractures, sprains, injuries, or any deterioration of health problems already present at 3 and 12 months | There were no between-group differences in number of adverse events at 3 or 12 months | |

|

Harris et al., 2017 [60] UK |

Changes in patient self-report outcomes of anxiety, depression and pain at 3 and 12 months | The interventions had no significant effects on anxiety, depression, or pain scores |

| Falls, injuries, fractures, cardiovascular events, and deaths at 3 and 12 months | Total adverse events did not differ between groups at 3 or 12 months, however, cardiovascular events over 12 months were lower in the intervention groups than in controls (p = 0.04) | |

| Changes in patient-reported outcomes of exercise self-efficacy and quality of life at 3 and 12 months | Exercise self-efficacy significantly increased in both intervention groups at 3 months for postal group v. control group (ES = 1.1, 95% CI: 0.2 to 2.0; p = 0.01), nurse group versus control (ES = 2.3, 95% CI: 1.4 to 3.2; p < 0.001) and there was a greater effect in the nurse group compared with postal (ES = 1.2, 95% CI: 0.3 to 2.1; p = 0.01). By 12 months, there was a difference between only the nurse and control groups (ES = 1.2, 95% CI: 0.3 to 2.2, p = 0.01). The interventions had no significant effects on quality of life scores | |

|

Iles et al., 2014 [46] Australia |

Patient quality of life measured by patient questionnaires at baseline (pre-intervention) and at 2 years, including a quality of life score using the EuroQol 5-Dimensions, scored with the Australian algorithm | Patient quality of life scores did not differ at baseline between RN-led groups (0.81 ± 0.18) and GP-led groups (0.81 ± 0.18). The quality of life score was inversely associated with MBS item charges (p < 0.001). On average, a 1% increase in the quality of life score resulted in a 44.5% decrease in MBS item charges |

|

Marshall et al., 2011 [51] New Zealand |

Patient physical fitness, daily activity, social activity, social support, feelings, and quality of life, derived from the Dartmouth Primary Care and Cooperative charts and patient self-report survey data | Significant improvements were shown in survey results for social activity (mean difference = -0.20; p = 0.049), change in health (mean difference = -0.42; p = 0.001), and overall health (mean difference = -0.21; p = 0.025); there no changes were reported for quality of life |

|

Moher et al., 2001 [52] UK |

Patient self-report quality of life, as measured by the Dartmouth Primary care and Cooperative charts and the EuroQol questionnaire | The study found no significant or clinically important difference between groups for any dimension of the Dartmouth Primary Care and Cooperative charts or for EuroQol scores |

|

Pearson et al., 2003 [61] USA |

Changes in patient level of depression, overall physical and mental health, and the impact of depression on their work and productivity from baseline to 6-month follow-up |

Significant differences between baseline and six months were seen in the major subscales of the Work Limitations Questionnaire: time demands: 66.5 to 84.2, physical demands: 84.1 to 91.3, mental demands: 63.7 to 83.6, interpersonal demands: 77.2 to 90.5, and work output: 67.7 to 85.3. Paired t-test results for the difference in mean scores at baseline and 6-month follow-up for the SF-12 (mean = 29.9 to 48.2), Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (mean = 14.6 to 6.5) and Work Limitations Questionnaire (mean = 70.4 to 87.2) were statistically significant at the 0.0001 level These results show a significant reduction in depression severity for patients treated by the nurse telecare program, with 63% experiencing at least 50% reduction in their score at the 6-month follow-up |

| Health Behaviours | ||

|

Aveyard et al., 2007 [53] New Zealand |

Confirmed sustained abstinence from smoking at 4, 12, 26, and 52 weeks after quit day |

Of the participants in the basic and weekly arms, the quit % and the percentage difference was 22.4% v. 22.4% at 4 weeks (OR = 1.00; 95% CI: 0.74 to 1.37), 14.1% v. 11.4% at 12 weeks (OR = 0.79; 95% CI: 0.54 to 1.17), 10.7% v. 8.8% at 26 weeks (OR = 0.81; 95% CI: 0.52 to 1.25), and 7.7% v. 6.6% at 52 weeks (OR = 0.85; 95% CI: 0.51 to 1.41). There was no evidence that those in the weekly contact arm were more likely to quit, with point estimate of the quit rates favoring the basic support arm Absolute quit rates achieved are those expected from nicotine replacement therapy alone; neither of the support types were considered effective. PNs have a key role in providing support for smoking cessation, however, providing basic medication support is an adequate approach to achieve positive outcomes |

| Patient reported use of nicotine replacement therapies at first telephone call and at each follow-up contact | Rates of nicotine replacement therapy use were high and did not differ between arms | |

|

Byers et al., 2018 [54] USA |

Smoking status changes (i.e., whether patients reported themselves as smokers or non-smokers [former, quit, etc.]) at their last visit compared to their first visit | In GP-led visits, 18.2% (14 out of 77) patients who were reported as smokers during their first visit were reported as nonsmokers at their last visit, compared with 29.1% (41 out of 141) patients who attended RN-led visits. This difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.077); however, the findings suggest that smoking cessation is at least equivalent in patients who attend nurse-led visits compared with physician-led visits, and may be higher |

|

Cherkin et al., 1996 [57] USA |

Changes to patient self-reported participation in regular aerobic exercise between baseline and follow-up | Self-reported exercise was higher in the nurse intervention group after a 1-week follow-up (p < 0.001), however, there was no significant difference after 7 weeks |

|

Faulkner et al., 2016 [55] UK |

Self-reported 2-week point prevalence smoking abstinence at the 8-week follow-up Self-reported 6-month prolonged smoking abstinence at 6 months follow-up CO2 verified 2-week point-prevalence smoking abstinence at 4 weeks following quit date |

No statistically significant differences between the two groups in the primary outcome measure of 2-week point prevalence abstinence at 8 weeks follow-up in both the unadjusted (OR = 1.01, 95% CI: 0.73 to 1.40) and adjusted models (OR = 1.07, 95% CI: 0.76 to 1.51) (adjusted for patients’ occupational category, initial CO reading and trial intervention arm) There were also no statistically significant differences in abstinence for support delivered by HCAs v. nurses at 4 weeks (unadjusted OR = 1.15, 95% CI: 0.80 to 1.66; adjusted OR = 0.86, 95% CI: 0.52–1.40) or 6 months follow-up (unadjusted OR = 0.86, 95% CI: 0.52 to 1.40; adjusted OR = 0.93; 95% CI: 0.55 to 1.56). Nurses and HCAs appear to be equally effective at supporting smoking cessation, however, nurses appear to be able to provide equivalent care with less patient contact |

|

Harris et al., 2015 [59] UK |

Daily physical activity as defined by change in average daily step-counts between baseline and 3 months, and between baseline and 12 months, assessed by accelerometry | At 3 months, changes in average daily step-counts were significantly higher in the intervention than control group by 1,037 (95% CI: 513 to 1,560; p < 0.001) steps/day. At 12 months, corresponding differences were 609 (95% CI: 104 to 1,115; p = 0.018) steps/day |

| Weekly physical activity as defined by change in average weekly time spent in MVPA; MVPA in > 10-min bouts; accelerometer counts and counts per minute of wear-time between baseline and 3 months | The intervention increased objectively measured physical activity levels in older people at 3 months, with a sustained effect at 12 months. At 3 months, changes in weekly MVPA in ≥ 10-min bouts were significantly higher in the intervention than control group by 63 (95% CI: 40 to 87; p < 0.001) minutes/week, respectively. At 12 months corresponding differences were 40 (95% CI: 17 to 63; p = 0.001) minutes/week. Counts and counts/minute showed similar effects to steps and MVPA | |

|

Harris et al., 2017 [60] UK |

Changes to physical activity as defined by average daily step counts, changes in step counts between baseline and 3 months, changes in time spent weekly in MVPA in > 10-min bouts, and time spent sedentary between baseline, 3 months and 12 months |

Both intervention groups increased their step counts at 12 months compared with control (p < 0.001), with no statistically significant difference between nurse and postal delivery groups There were significant differences for change in step counts at the 3-month follow-up between intervention groups and the control group (nurse-supported group v. control 1,172 steps, 95% CI: 844 to 1,501; p < 0.001; postal group v. control 692 steps, 95% CI: 363 to 1,020; p < 0.001), however, the difference between the intervention groups was statistically significant (481 steps 95% CI: 153 to 809; p = 0.004). The two intervention groups had significantly increased step counts at 12 months, as compared to the control, but the two intervention groups did not significantly differ from each other on this outcome at 12 months. Findings for MVPA showed a similar pattern. The intervention had no significant impact on sedentary time |

| Changes in patient-reported outcomes of exercise self-efficacy and quality of life at 3 and 12 months | Exercise self-efficacy significantly increased in both intervention groups at 3 months for postal group v. control group (ES = 1.1, 95% CI: 0.2 to 2.0; p = 0.01), nurse group versus control (ES = 2.3, 95% CI: 1.4 to 3.2; p < 0.001) and there was a greater effect in the nurse group compared with postal (ES = 1.2, 95% CI: 0.3 to 2.1; p = 0.01). By 12 months, there was a difference between only the nurse and control groups (ES = 1.2, 95% CI: 0.3 to 2.2, p = 0.01). The interventions had no significant effects on quality of life scores | |

|

Marshall et al., 2011 [51] New Zealand |

Changes in smoking status (including both smoking cessation as well as smoking reduction) between first and last clinic attended | Although the percentage of adults who reported smoking remained the same between the first and last clinic data, there was a change in number of cigarettes smoked, in that the percentage of people who smoked between 0 and 10/day increased and those who smoked ≥ 11/day decreased |

| Patient physical fitness, daily activity, social activity, social support, feelings, and quality of life, derived from the Dartmouth Primary Care Cooperative Information charts and patient self-report survey | Significant improvements were shown in survey results for social activity (p = 0.049), change in health (p = 0.001), and overall health (p = 0.025); there no changes were reported for quality of life. Ninety-four percent of patients reported having a better understanding of their diagnosis, medication and treatment plan, and that they were more motivated to self-manage their health needs. | |

|

Pine et al., 1997 [49] USA |

Changes to patient dietary intake as measured by the EPAT from first to final nurse visit | Mean EPAT scores at baseline in both studies demonstrated that intervention patients were already following a diet consistent with the National Cholesterol Education Program Step 1 Diet. However, the mean Section 1 EPAT score improved from 23.4 at the first nurse visit to 20.4 at the final nurse visit (p< 0.001) |

|

Zwar et al., 2010 [56] Australia |

Smoking status, defined as “point prevalence” (no smoking in seven days preceding the assessment) and “continuous abstinence” (no smoking from quit date to assessment at 4- and 6-month follow-up) | At 6-month follow-up, the point-prevalence abstinence rate was 21.7% (108 out of 498 participants at baseline) and the continuous abstinence rate was 15.9% (79 out of 498 participants at baseline). Participants with very low to medium nicotine dependence (0–5 Fagerström Score) had significantly higher point prevalence cessation rates than those with high to very high dependence (score > 5) (p < 0.001). Continuous abstinence rate was not significantly different between these groups. Patients who had attended four or more counseling visits with the RN were significantly more likely to quit at 6 months than patients who attended less than four times (point prevalence abstinence 32% v. 9%, p < 0.001; continuous abstinence 25% v. 3%, p <0.001) |