Abstract

Purpose

Due to population aging, the number of older adults with cancer will double in the next 20 years. There is a gap in research about older adults who are the caregiver of a spouse with cancer. Therefore, this review seeks to answer the overarching research question: What is known about the association of providing care on Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQOL), psychological distress, burden, and positive aspects of caregiving for an older adult caregiver to a spouse with cancer?

Methods

This scoping review was guided by the framework of Arksey and O’Malley and refined by Levac et al. Comprehensive search strategies were conducted in Medline, Excerpta Medica Database (EMBASE), PsycINFO, and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) from inception until April 15, 2021. Two independent reviewers screened abstracts, full text, and completed data abstraction. A gray literature search and two stakeholder consultations were conducted.

Results

A total of 8132 abstracts were screened, and 17 articles were included. All studies outlined caregivers provided preventive, instrumental, and protective care to a spouse in active cancer treatment. However, the time spent on caregiving was rarely examined (n = 4). Providing care had a negative association on HRQOL, perceived burden, and psychological distress outcomes. Five studies examined positive experiences of caregivers.

Conclusion

The scoping review findings highlight the informal care provided by older adult caregivers to a spouse with cancer and how the care provided is associated with HRQOL, burden, psychological distress, and the positive aspects of caregiving.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00520-022-07176-2.

Keywords: Older adult, Scoping review, Caregiver, Cancer, Spouse

Introduction

Cancer is the leading cause of death in Canada, predominantly affecting older adults [1]. The Canadian population is aging—17.5% of Canadians were ≥ 65 in 2020, and the number of older adults with cancer is expected to double in the next 20 years [2]. Statistics Canada’s General Social Survey indicated that 28% of Canadians are family caregivers, and 13% of all caregivers are spouses [3]. Many older adult caregivers can have chronic diseases like diabetes and arthritis [4–8]. Spousal caregivers experience more significant mental and physical health problems related to caregiving than other informal caregivers [9]. Spousal caregivers have reported higher levels of physical burden, more psychological symptoms such as depression, and lower overall well-being than adult–child caregivers [9]. Caregiving for an older adult with cancer may present many physical and psychological challenges, especially for caregivers coping with their own history of chronic health conditions [4–8]. Recent reviews [10, 11] examining caregivers’ roles to older adults with cancer reported that distress in caregivers is affected by several factors including patient characteristics, caregiver characteristics, intensity of care provided (hours, caregiver duration), and available supports. Adashek and Subbiah [10] reported that up to 40% of older adult caregivers had major comorbidities and 22% experienced worsened health due to caregiving. Similarly, anxiety, depression, and distress were common symptoms experienced by most caregivers during the caregiving trajectory [10]. However, both reviews have significant methodological limitations. Neither review specified the detailed review methodology, nor used a comprehensive search of multiple databases. Even though adverse caregiving outcomes have been well documented in the literature, less is known about older adult caregivers’ possible benefits and positive experiences. For example, previous literature has outlined that family caregivers also experience positive aspects of caregiving, related to being present and strengthening the relationship, spiritual growth, and emotional healing, which may even buffer against depression and burden [12, 13].

While there have been efforts to document the experiences of caregivers to older adults with cancer [10, 11, 14], there is a gap in research about older adults who are the caregiver of a spouse with cancer. It is unknown what care they provide for their spouses and how it affects the caregiver.

Step 1: Research questions

What is the type and amount of care provided to a spouse with cancer?

What is the association of providing care to a spouse with cancer on the caregiver's health-related quality of life (HRQOL), perceived burden, and psychological distress?

What is the association of providing care on the positive experiences of caregivers of individuals with cancer?

Materials and methods

The scoping review (SCR) framework outlined by Arksey and O’Malley and refined by Levac et al. [15–17] and the PRISMA extension for Scoping Reviews statement was used [18]. The framework includes six steps: (1) identifying the research questions (listed above); (2) identifying relevant literature; (3) study selection; (4) charting the data; (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results; (6) consulting with key stakeholders and translating knowledge.

Step 2: Identification of relevant literature

A comprehensive search strategy was conducted on April 15, 2021, and reviewed by a health sciences librarian in the following electronic databases: Medline, EMBASE, APA PsycINFO, and CINAHL. Search strategies were developed by the first author (VD), with input from the research team (NT, SA, KM, MP). The search was initially built in MEDLINE Ovid before being translated into other databases. Searches were limited to English. The search results were exported into Covidence [19], where duplicates were identified and removed. A gray literature search plan included (1) targeted website browsing (American Cancer Society, Oncology Nursing Society, Association of Cancer Online Resources, etc.), and (2) gray literature databases (TRIP Pro). For the complete Medline search strategy, see Online Resource Supplemental File S1.

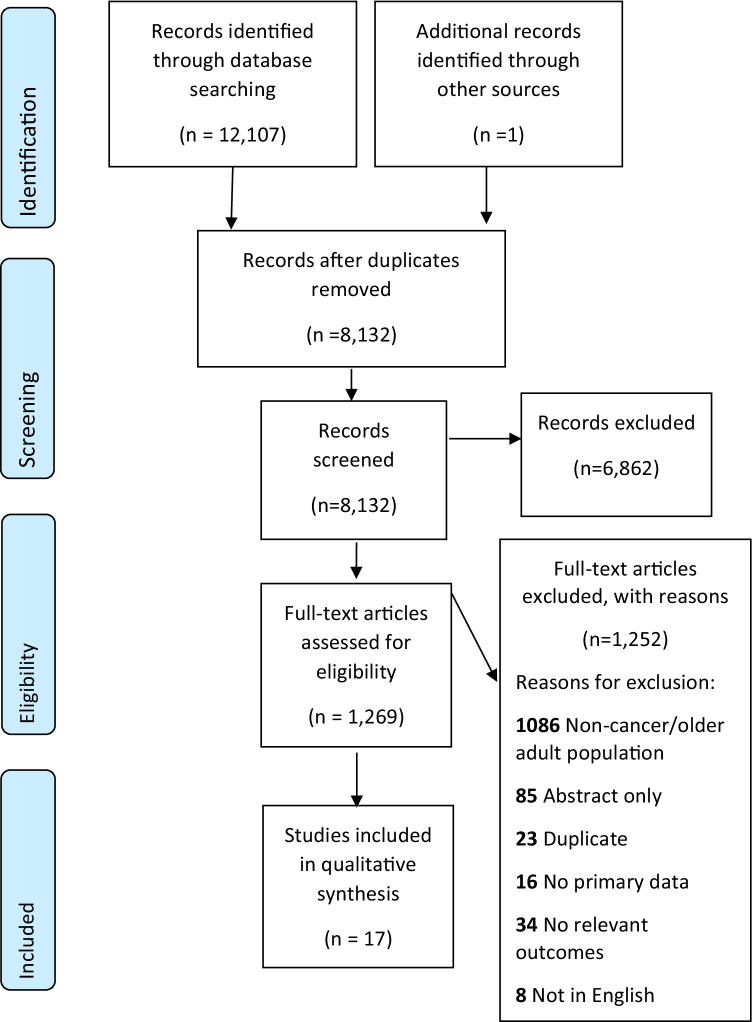

Step 3: Study selection

Studies were selected through a two-step process. First, titles and abstracts were screened independently by two team members (VD, NT). Next, full-text articles were screened by the same two reviewers (see Fig. 1 PRISMA flowchart). A third reviewer assessed the abstract or full text in case of disagreements, and a consensus decision was made (AS). The references of all included studies were screened, and additional articles that met the inclusion criteria were included.

Fig. 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flowchart

Eligibility criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they were: Any type of study design reporting primary data (except editorials, opinion papers), older adults (aged 65 and over or the mean age in a study population 65 and over, or if younger included subgroup analysis of those 65 years and over), informal caregivers to a spouse with any cancer on active treatment (chemotherapy, radiation, or other systemic therapy), reported on type and amount of care provided, HRQOL, psychological distress, caregiver burden, or positive experiences of caregivers, published in English from the beginning of each database to April 15, 2021.

Inclusion criteria for the caregiver: Older adults (aged 65 and over or the mean age in a study population 65 and over, or if younger included subgroup analysis of those 65 years and over)

Inclusion criteria for the patient: Patients of any age, undergoing active cancer treatment (chemotherapy, radiation, or other systemic therapy).

Conceptualization of outcomes

For this review, type of care was defined using Bower’s (1987) conceptualization of family care and refined by Nolan et al. (1995) [20], which constitutes of eight categories: (1) anticipatory care, (2) preventive care, (3) supervisory care, (4) instrumental care, (5) protective care, (6) preservative care, (7) (re)constructive care, and (8) reciprocal care [20, 21]. HRQOL is defined as a multidimensional concept that measures domains related to physical, mental, emotional, and social functioning and impact on daily life. As many studies reported on the unmet needs of caregivers, it was additionally included in our results. Caregiver report of unmet needs is defined as the health care service needs, psychological and emotional needs, and work and information needs [22]. Please see Online Resource Supplemental Table S1 definitions for further explanation on type of care, amount of care, HRQOL, unmet needs, psychological distress, caregiver burden, and positive caregiving experiences outcomes.

In this review, caregiver burden and psychological distress were assessed separately from HRQOL. Previous studies of cancer caregivers have shown that an increased burden on caregivers has led to poor physical and psychological health and decreased HRQOL [23, 24]. The degree to which the spousal caregiver experiences distress in the caregiving role directly affects their ability to care for the spouse with cancer, as suggested by previous literature on family caregivers of cancer survivors [25, 26]. Positive caregiving experiences were defined as benefit finding such as personal growth, increased meaning, purpose in ones’ life, extra time spent with a spouse, as outlined by the caregiver, and the reciprocal nature of caregiving.

Step 4: Data abstraction

All studies and data were extracted and charted by two reviewers using Excel spreadsheets. Extracted data included study details and details on study population (patient and caregiver characteristics), caregiver outcomes regarding the type and amount of care provided, HRQOL, caregiver burden, psychological distress, and positive experiences of caregivers. A total of 11/17 authors were contacted via email and only two responded to provide missing data.

Quality assessment

The quality of included studies was assessed by two independent reviewers (VD, NT), using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 [27]. This tool can be used to assess quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods studies. Studies were not excluded based on the quality assessment.

Step 5: Data synthesis and presentation of results

Data synthesis

Study characteristics are summarized narratively in the text and shown in summary tables in the manuscript and supplementary file.

Step 6: Stakeholder consultation and knowledge translation

Stakeholder consultations were conducted with (1) the Registered Nurses Association of Ontario (RNAO)-Nursing Research Interest Group (NRIG), and (2) the Geriatric Oncology Journal Club (GOJC) monthly rounds at Princess Margaret Cancer Center, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, through informal online zoom webinars. NRIG and GOJC were chosen as they have interprofessional team members with expertise in geriatrics and oncology and include members with research and clinical expertise.

Results

After deduplication, two independent reviewers screened 8132 abstracts and 1269 full-text papers. Twenty papers reporting on 16 studies were retained, and one additional study [23] was included through hand screening the reference lists of included articles and systematic reviews (see Fig. 1).

Description of included studies

The characteristics of the 17 included studies are summarized in Appendix A Online Resource Supplemental Table S2.

Five studies were conducted in the USA [24–26, 28, 29], two in Israel [30, 31], two in Australia [32, 33], two in China [34, 35], and the rest in various individual countries. Nine studies were qualitative [23–25, 29, 32, 34, 36–38], five studies were cross-sectional [26, 31, 33, 35, 39], and three were mixed-methods [28, 30, 40]. All included studies were published between 1994 [30] and 2021 [24, 40]. The median sample size was 31 participants.

Characteristics of participants

Characteristics of participants are summarized in Online Resource Supplemental Table S3.

Caregivers

The mean age of caregivers ranged between 65 and 72 years (see Online Resource Supplemental Table S3). Twelve studies included a majority of female caregivers [23–26, 28, 29, 32, 34, 38–40], and the rest were majority male caregivers [30, 31, 35–37]. Six studies included a majority of their sample to be predominantly White [23, 25, 26, 28, 29, 32], one study had a minority White sample [37], and the remaining studies did not disclose ethnicity. Only one study [39] described caregiver chronic conditions including cancer, hypertension, chronic heart disease, musculoskeletal disease, diabetes, chronic lung disease, and dementia.

Patients

The mean age of patients ranged from 55.5 [36] to 78 [32] years. Ten studies had a majority of male patients [23, 25, 26, 28, 30–34, 39], three had a majority of female patients [35, 36, 40], and the rest did not account for sex.

Cancer type of the patient varied considerably across studies: four studies included participants with prostate cancer [23, 25, 28, 39], the rest of the studies were heterogeneous and included multiple cancer types [26, 29–37], and two did not describe cancer type [38, 40]. Modalities used for treatment were heterogeneous across all studies. See for more details on the caregivers Online Resource Supplemental Table S3.

Quality of included studies

The quality assessment results of the studies are reported in Online Resource Table 5. Most studies were of moderate to good quality. The five cross-sectional studies [26, 31, 33, 35, 39], and three mixed-methods studies [28, 30, 40] were of moderate quality. Two studies did not outline response rates [26, 33], and the sampling strategy was not always clear [26, 30], potentially increasing sample bias. The included qualitative studies were of good quality [23–25, 29, 32, 34, 36–38].

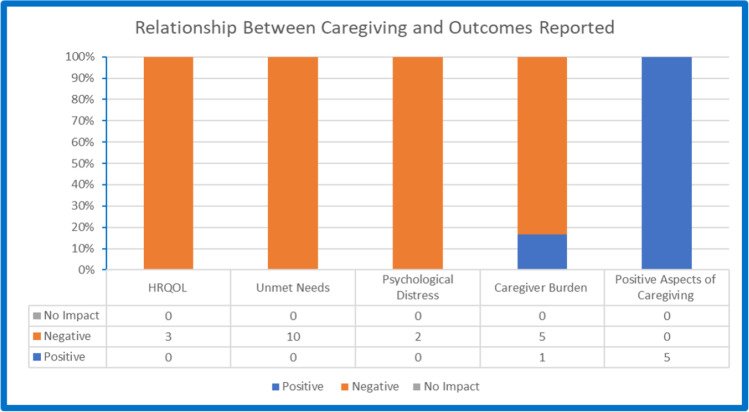

Description of outcomes in included studies

The outcomes described in included studies are described in Fig. 2 and Online Resource Table 4. Figure 2 outlines the relationship between caregiving and the outcomes of interest studied. All studies reported negative associations for the relationship between caregiving and HRQOL and psychological distress outcomes. Of the six papers that examined caregiver burden, five outlined negative associations, and one reported lower caregiver burden and positive caregiving experiences.

What is the type and amount of care provided to a spouse with cancer?

Fig. 2.

Relationship between caregiving and outcomes reported

All studies included domains related to the type of care, including preventive, instrumental, and protective care provided to a spouse in active cancer treatment. The proportion of studies that report on one of the eight included domains of care are listed first, and then are followed by the details of each care domain.

Ten of 17 studies included domains related to instrumental care [24, 28–32, 34, 36, 37, 40]. In 5/10 studies, caregivers were involved in most domestic tasks such as home maintenance, food preparation, shopping, laundry, and cooking during the postoperative phase and while patients were receiving chemotherapy and radiotherapy [30, 31, 34, 36, 37]. In particular, in 2/10 studies, husbands were involved in all aspects of the caregiving process, including helping with daily personal care (bathing, etc.), and they became responsible for domestic tasks previously performed by their wives before breast cancer surgery [34, 37]. In 2/10 studies, caregivers accompanied the spouse for treatments at the hospital [24, 37], and 3/10 studies caregivers helped patients access and obtain medication [29, 32, 40]. In another study wives provided medical care post-surgery (i.e., dressing changes) and helped with medication administration [28]. Only 1/17 studies examined preventive care. In a qualitative study, spouses had a significant role in managing cancer-related symptoms [29].

In 7/17 studies, protective care was evaluated [23, 25, 32, 33, 37, 39, 40]. In 4/7 studies, caregivers supported the patient emotionally during cancer treatment and assisted with managing the patient’s social life [25, 37, 39, 40]. In 4/7 studies, it was outlined that most caregivers reported seeking information about cancer and cancer-related treatment [23, 25, 32, 33].

Most commonly, caregivers sought information from health care providers, online sources, cancer support organizations, and friends/personal contacts [23, 32]. Managing anxiety and depression by promoting social activities and maintaining hobbies was reported in 1/7 studies [32]. No studies examined anticipatory care, supervisory care, preservative care, and (re)constructive care.

The amount of time spent on caregiving was analyzed in four studies (n = 4) [24, 26, 34, 35]. In one study, caregivers reported providing a median of 10 h/week, with the highest quartile providing ≥ 35 h of care per week, with 61%providing care for at least a year (n = 1) [26]. In another study, 69.4% of the participants provided care for less than 6 months, and 30.6% provided care for greater than 6 months [35]. Furthermore, in two qualitative studies, caregivers provided round-the-clock care for their partners [34], and participants identified time spent on medical logistics, such as organizing medical care, attending medical and treatment appointments, and time impacted by symptoms as burdensome [24]. However, neither study provided a measurable amount of time spent on care by the caregivers [24, 34].

-

2.

What is the association of providing care to a spouse with cancer on the caregiver’s HRQOL, perceived burden, and psychological distress?

HRQOL

In 3/17 studies, caregivers reported that providing care related to the effects of cancer treatment was associated with an impact on daily life and time available for personal and social activities [24, 25, 36]. Daily routines and hobbies were frequently interrupted by cancer and cancer treatment, and care demands limited time for personal activities and self-care [24, 36]. Caregivers reported that the need to rest up for long trips to the cancer center resulted in less frequent visits from participants’ children, and caregivers reported difficulty associated with interrupted plans and the inability to take vacations or take time off from cancer care [24, 25]. In another study, it was noted that a caregiver was forced to retire, as the spouse’s treatment was in another city. Due to this, the caregiver’s social relations with close friends suffered greatly [36].

Unmet needs

Many studies (10/17) reported on the unmet needs of caregivers. As this is an important finding in this review, it was additionally included in our results [24, 25, 28, 29, 33, 34, 36–38, 40]. The Supportive Care Needs Survey—Partners and Caregivers definitions of unmet needs (SCNS-P&C) [22] was used to categorize the unmet needs reported by the included studies in the manuscript. The categories of the SCNS-P&C that were mainly reported in the studies include discussion of concerns with a doctor [29, 33, 38], involvement in patient care [38], communication with the patient [38], information needs of carer [28, 33, 38, 40], information needs related to prognosis [34], information patient physical needs [28], information needs about support services [29], emotional support for self [33, 40], emotional support for loved ones [40], financial support [40], and access to health care services [40]. The need for more information was outlined in 6/10 studies [28, 29, 33, 34, 38, 40]. Caregivers reported a median of 3, moderately high/highly unmet needs [40]. Needs emerged related to health care service, up-to-date information, psycho-spiritual, social, and financial [40]. Researchers reported that spouses felt they needed to be provided with more information from health care providers’ (HCPs) on what is expected post-cancer treatment [28, 34, 38]. In one cross-sectional study, 31% of caregivers would have liked to be provided with clearer information [33]. Caregivers indicated they needed accurate and consistent information post-surgery and what is expected from them as caregivers from HCPs and were dissatisfied with the inconsistencies in the information that they obtained from different sources, such as from other healthcare professionals and friends [28, 34, 38]. Also, tasks related to nursing care were never adequately explained, so caregivers had to execute unfamiliar tasks without knowledge and support [38].

Burden

The association of providing care on perceived caregiver burden was examined in 6/17 studies [26, 28, 30, 31, 35, 40]. In 5/6 studies, caregivers reported that caregiving tasks are burdensome [26, 30, 31, 35, 40]. Researchers reported that caregivers caring for patients who required help with 2 or more IADL’s were more likely to experience high caregiver burden (Caregiver Strain Index score, ≥ 7) [26]. One study outlined that spouses rated the burden of caregiving on a higher level than do the patients themselves (mean: 2.11 caregivers versus 1.34 among patients using the Zarit Caregiver Burden Scale, p < 0.05) [30]. On the contrary, one study [28] included participants with a low caregiver burden (mean 15.4, possible score ranges 9 to 45) on the Appraisal of Caregiving Scale and 60% of wives felt that their husbands were not demanding and felt that husbands showed appreciation for the care provided.

Psychological distress

Only 2/17 studies reported on the association of providing care on psychological distress [25, 33]. In both studies, psychological distress was related to the cgs’ involvement in the treatment decision making process [25, 33]. In particular, in one study, almost 25% of caregivers felt the choice to have chemotherapy negatively affected the patient, as assessed on the Decisional Regret Scale, where the mean score was in the moderate–severe range and thought their choice had caused harm to the patient [33]. In another study, wives were involved in the decision process from diagnosis to treatment options, and many expressed a nagging worry about their future together [25]. However, 4/17 studies reported that cgs’ cause of distress was primarily due to cancer-related experiences such as the diagnoses and treatment phase, and not associated with caregiving [34, 36, 37, 39]. In particular, in 3/4 studies, caregivers experienced stress and emotional difficulties such as fear, anxiety, and worry when they acknowledged the diagnosis of their spouses and needed to cope with it [34, 37, 39]. One cross-sectional study outlined that all caregivers reported at least one psychological symptom on the Cancer specific-Rotterdam symptom checklist (RSCL) (mean 9.7, SD 5.8, with higher scores indicating more symptoms) [39].

-

3.

What is the association of providing care on the positive experiences of caregivers of individuals with cancer?

In 5/17 studies, the association of providing care on the positive experiences of caregivers and the reciprocal nature of caregiving [25, 28, 34, 36, 37] was described. Several domains related to positive aspects of caregiving were reported by caregivers including appreciation of the relationship [28, 34], comfort and togetherness [28], increase in spiritual well-being, finding meaning in the disease [36], extra time spent with spouse and family [25, 37], improvement in relationship [34], and increased meaning and purpose in one’s life [37]. In one study, the disease process provoked an internal change in spouses, and a greater awareness and understanding of the disease process [37]. In this study, the husbands stated that they regularly took time to reflect on their existence, as referenced by the patient quote, “as a product of the whole process, I had an experience: we think that we will never confront a similar problem. I see that death is a natural thing. I changed very much. Nowadays, I help my wife more than before, to avoid health problems; I became aware of the importance of my wife in my life” [37].

Gray literature findings

The National Cancer Institute’s (2021) Physician Data Query (PDQ) document on “Informal Caregivers in Cancer: Roles, Burden, and Support” [41] summarizes that older family caregivers often feel unprepared, receive minimal guidance from the oncology team in providing patient care, and have inadequate knowledge. However, the findings of this report should be interpreted with caution, as the summary reflects a narrative review by the PDQ board members.

Step 6: Consulting with key stakeholders and translating knowledge

Stakeholder consultations were conducted with NRIG on September 21, 2021, and the GOJC monthly rounds on September 28, 2021. Stakeholders reported that this is a very relevant topic that is understudied and a population they regularly cared for in their clinical setting. Stakeholders mentioned that it is vital to assess what the caregiver needs in terms of support. Some stated that caregivers have personally reported that they need help in terms of supports to assist with caregiving.

Both groups also addressed the importance of examining the influence of COVID-19 on caregiver experiences, such as restricted visits and the effect of education related to care provided post-treatment, and how the lack of the caregiver being present may affect the care provided post-treatment. Stakeholders mentioned that caregivers with chronic conditions, such as cancer, might be hesitant to begin treatment due to the caregiving needs of the spouse. The stakeholders recommended that future research focus on supportive interventions based on the caregiving needs.

Discussion

The review focusing on spousal caregivers of older adults in active cancer treatment identified that caregiving was negatively associated with HRQOL burden and psychological distress on the caregiver. This finding is consistent with previous literature on the association of being a cancer caregiver on the caregivers’ HRQOL burden and psychological distress [42–45]. In our review, caregivers experienced unmet needs related to inconsistencies in information and what is expected of them as caregivers [28, 33, 34, 38]. Furthermore, caregivers that provided care to spouses requiring assistance in ADL’s and IADL’s experienced greater caregiver burden [26, 30, 35], and caregivers experienced psychological distress related to the treatment decision making process [25, 33]. [25, 34, 36, 39]. However, there were some reciprocal and positive aspects to providing care to spouses, such as closeness and strengthening of the relationship [28, 34]. Only a few categories of caregiving were identified in this review including preventive, instrumental, and protective care provided to a spouse in active cancer treatment. None examined other important categories including anticipatory care, supervisory care, preservative care, and (re)constructive care. Caregivers provided instrumental care post treatment in most studies included in this review. This finding builds on previous reviews where caregivers provide a broad range of support most often focused on aspects of routine and daily life [10, 11]. However, the time spent by the spouse in providing care was seldom discussed.

Gender differences were highlighted in 1/17 studies [40]. Females were more likely to report negative health consequences, and detriment to social relationships due to caregiving than male caregivers [40]. These findings are consistent with the results of previous literature, where female caregivers experienced greater negative health consequences and decreased quality of life than men [46, 47]. However, consideration of important gender differences in this population was largely unexplored.

Only one study utilized a developmental perspective based on the association of caregiving on older adult caregivers by age cohort [25]. The findings in this literature review may not reflect the experience of caring for an older adult patient with cancer since the age of the patients in this review varied. For example, it has been previously noted in the literature that with aging, older adults tend to use accommodation (psychological reorientation, realignment of priorities, revision of goals, and cognitive appraisal of life) as a method to counteract problems [25]. Furthermore, chronic illness in later life may impact both spouses, and could be associated with specific stressors and coping abilities that are unique to older adults [48]. However, consideration of important developmental perspectives in this age group was not captured.

Research implications and research recommendations

Future studies should explore the needs of spousal older adult caregivers, the needs for supports needed for them to provide care, and to explore how their caregiving experiences are impacting their health and psychosocial HRQOL domains, such as financial concerns. Also, studies should explore how caregiver chronic conditions may impact the type and amount of care provided to the patient.

Future studies should conduct a caregivers’ needs assessment to understand what supportive interventions are needed to help support caregiving. Moreover, future studies should address essential gender differences and how providing care may affect men and women caregivers differently and whether the need for supports differ by gender.

Limitations of literature

Four databases were searched for studies published in English. There may be studies in other databases or languages that were not identified. Based on the gray literature search, the authors found only one PDQ document [41] on cancer caregiving; there could be literature that was missed. Most studies included White, retired, and higher educated female spouses, which affect the generalizability of findings to other caregiver populations. A limited number of articles examined caregiver chronic conditions and how this was associated with the care provided, and the time spent on providing care to the patient. Also, the variation in the patients studied, including cancer type, disease stage and treatment modalities, and heterogeneity of instruments used to assess outcomes of interest, made it challenging to compare studies. Due to the nature of the population and topic of interest, most studies used non-probability sampling to recruit patients and caregivers, therefore decreasing the generalizability of the findings to the target population. As the findings are limited to the studies published, the quality of the reviewed quantitative studies should impact interpretation of the results of this review. As all five quantitative studies were cross-sectional, limiting the ability to measure the impact and effects of the predictors on the outcomes of interest. Also, two studies did not outline response rates [26, 33], and the sampling strategy was not always clear [26, 30], potentially increasing sample bias. Moreover, most of the cross-sectional studies focused on female caregivers, which limits the generalization to other populations. Only one study [25] reported the results based on age groups (i.e., young-old, old-old, etc.).

There was a limited exploration of important psychosocial HRQOL domains, such as financial concerns, such as the association of caregiving on personal and household finances. Also, no study analyzed the association of chronic caregiver conditions on the care provided. It remains largely unknown how the conditions and the experiences of spousal caregivers with their chronic conditions, such as cancer, might impact the health, well-being, and care of the spousal caregiver and their care recipient. Since the majority of spousal caregivers will have one or more chronic conditions, it is important that the association and impact of having a chronic condition(s) on the care provided is examined in future studies. An additional limitation of the review is the focus on spousal caregivers. Older adults with cancer may receive care from other caregivers, especially adult children. Furthermore, a limitation of the literature is a failure to assess and consider the unique context of caring for an older adult. For example, only one study utilized a developmental perspective based on the association of caregiving by age cohort [25]. Future research should capture the unique context of caring for an older adult. As the studies were conducted prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, future studies should explore how the pandemic has interfered with caregiving for spouses with cancer.

In conclusion, providing care to a spouse undergoing active cancer treatment had a negative association on the HRQOL, burden, and psychological distress in older spouse caregivers. Future studies need to focus on addressing these gaps and implementing supportive interventions for this population.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Ms. Valentina Donison is supported by the Ontario Graduate Scholarship, Queen Elizabeth II/University of Toronto Foundation Graduate Fellowship in Science and Technology.

The authors would like to thank the stakeholders for their time and involvement in providing expertise and valuable feedback on this population.

The authors would like to thank Ana Patricia Ayala for her assistance with the search strategy used for this review.

This review has been presented as an oral lightning session at the annual meeting of the Canadian Cancer Research Alliance Conference in November 2021, and as a poster at the International Society of Geriatric Oncology Conference in November 2021.

Author contribution

Conception and design: VD, SA, MP, KM.

Data collection: VD, NT.

Analysis: VD, NT, AS.

Interpretation of data: VD, NT, MP, SA, KM,

Manuscript writing: VD, NT, AS, MP, SA, KM.

Approval of final article: VD, NT, AS, MP, SA, KM.

All the authors have approved the final article.

Funding

Ms. Valentina Donison is supported by the Ontario Graduate Scholarship, Queen Elizabeth II/University of Toronto Foundation Graduate Fellowship in Science and Technology. Dr. Puts is supported by a Canada Research Chair in the care for frail older adults.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable. Data collected from previously published studies in which informed consent was obtained by primary investigators.

Consent to participate

Not applicable. Data collected from previously published studies in which informed consent was obtained by primary investigators.

Consent for publication

All the authors have given their consent for this manuscript to be published in Supportive Care in Cancer.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Canadian Cancer Society 2020 S Cancer Statistics

- 2.Statistics Canada 2020 Older adults and population aging statistics

- 3.Hardy MO 2018 Senka, Statistics Canada: Caregivers in Canada, 2018

- 4.Ketcher D, et al. The psychosocial impact of spouse-caregiver chronic health conditions and personal history of cancer on well-being in patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021;62(2):303–311. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Onishi H, et al. Spouse caregivers of terminally-ill cancer patients as cancer patients: a pilot study in a palliative care unit. Palliat Support Care. 2005;3(2):83–86. doi: 10.1017/S1478951505050157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reblin M, et al. Everyday couples’ communication research: overcoming methodological barriers with technology. Patient Educ Couns. 2018;101(3):551–556. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2017.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reblin M, et al. In-home conversations of couples with advanced cancer: support has its costs. Psychooncology. 2020;29(8):1280–1287. doi: 10.1002/pon.5416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reblin M, et al. Behind closed doors: how advanced cancer couples communicate at home. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2019;37(2):228–241. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2018.1508535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oldenkamp M, et al. Subjective burden among spousal and adult-child informal caregivers of older adults: results from a longitudinal cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16(1):208–208. doi: 10.1186/s12877-016-0387-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adashek JJ, Subbiah IM. Caring for the caregiver: a systematic review characterising the experience of caregivers of older adults with advanced cancers. ESMO open. 2020;5(5):e000862–e000862. doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2020-000862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kadambi S, et al. Older adults with cancer and their caregivers - current landscape and future directions for clinical care. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2020;17(12):742–755. doi: 10.1038/s41571-020-0421-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen CA, Colantonio A, Vernich L. Positive aspects of caregiving: rounding out the caregiver experience. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17(2):184–188. doi: 10.1002/gps.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee JH. Exploring family caregivers’ subjective experience of positive aspects in home-based elder caregiving: from Korean family caregivers’ experience. Int J Soc Sci Stud. 2020;8(4):176. doi: 10.11114/ijsss.v8i4.4876. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ochoa CY, Buchanan Lunsford N, Lee Smith J. Impact of informal cancer caregiving across the cancer experience: a systematic literature review of quality of life. Palliat Support Care. 2020;18(2):220–240. doi: 10.1017/S1478951519000622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Colquhoun HL, et al. Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(12):1291–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci IS. 2010;5(1):69–69. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tricco AC, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Covidence Software 2021 [cited 2021; Available from: covidence.org.

- 20.Nolan M, Keady J, Grant G. Developing a typology of family care: implications for nurses and other service providers. J Adv Nurs. 1995;21(2):256–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1995.tb02522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garcia-Ptacek S, et al. The caregiving phenomenon and caregiver participation in dementia. Scand J Caring Sci. 2019;33(2):255–265. doi: 10.1111/scs.12627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Girgis A, Lambert S, Lecathelinais C. The supportive care needs survey for partners and caregivers of cancer survivors: development and psychometric evaluation. Psycho-oncology (Chichester, England) 2011;20(4):387–393. doi: 10.1002/pon.1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Docherty A, Brothwell CPD, Symons M. The impact of inadequate knowledge on patient and spouse experience of prostate cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2007;30(1):58–63. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200701000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hall ET, et al. Perceptions of time spent pursuing cancer care among patients, caregivers, and oncology professionals. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(5):2493–2500. doi: 10.1007/s00520-020-05763-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harden JK, Northouse LL, Mood DW. Qualitative analysis of couples' experience with prostate cancer by age cohort. Cancer Nurs. 2006;29(5):367–377. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200609000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hsu T, et al. Factors associated with high burden in caregivers of older adults with cancer. Cancer. 2014;120(18):2927–2935. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hong QN, Gonzalez-Reyes A, Pluye P. Improving the usefulness of a tool for appraising the quality of qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies, the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) J Eval Clin Pract. 2018;24(3):459–467. doi: 10.1111/jep.12884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Brien ME. Wife caregiver experiences in the patient with prostate cancer at home. Urol Nurs. 2017;37(1):37–46. doi: 10.7257/1053-816X.2017.37.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwartz AJ, et al. The experiences of older caregivers of cancer patients following hospital discharge. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(2):609–616. doi: 10.1007/s00520-018-4355-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gilbar O. The elderly cancer patient and his spouse: two perceptions of the burden of caregiving. J Gerontol Soc Work. 1994;21(3/4):149–158. doi: 10.1300/J083V21N03_10. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lowenstein A, Gilbar O. The perception of caregiving burden on the part of elderly cancer patients, spouses and adult children. Fam Syst Health: J Collab Fami HealthCare. 2000;18(3):337–346. doi: 10.1037/h0091862. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pethybridge R, Teleni L, Chan RJ. How do family-caregivers of patients with advanced cancer provide symptom self-management support? A qualitative study. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2020;48:101795. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2020.101795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Warby A, et al. A survey of patient and caregiver experience with malignant pleural mesothelioma. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(12):4675–4686. doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-04760-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li Q, et al. The experiences of Chinese couples living with cancer: a focus group study. Cancer Nurs. 2015;38(5):383–394. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luo J, et al. Factors related to the burden of family caregivers of elderly patients with spinal tumours in Northwest China. BMC Neurol. 2020;20(1):69. doi: 10.1186/s12883-020-01652-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Akyüz A, et al. Living with gynecologic cancer: experience of women and their partners. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2008;40(3):241–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2008.00232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoga LA, Mello DS, Dias AF. Psychosocial perspectives of the partners of breast cancer patients treated with a mastectomy: an analysis of personal narratives. Cancer Nurs. 2008;31(4):318–325. doi: 10.1097/01.NCC.0000305748.43367.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marcotte J, et al. Needs-focused interventions for family caregivers of older adults with cancer: a descriptive interpretive study. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(8):2771–2781. doi: 10.1007/s00520-018-4573-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lehto U-S, Aromaa A, Tammela TL (2018) Experiences and psychological distress of spouses of prostate cancer patients at time of diagnosis and primary treatment. Eur J Cancer Care 27(1):e12729. 10.1111/ecc.12729 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Stolz-Baskett P, et al. Supporting older adults with chemotherapy treatment: a mixed methods exploration of cancer caregivers' experiences and outcomes. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2021;50:101877. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2020.101877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Informal Caregivers in Cancer: Roles, Burden, and Support (PDQ®)–Health Professional Version, pp 1–41. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/coping/family-friends/family-caregivers-hp-pdq [PubMed]

- 42.Daly BJ, et al. Needs of older caregivers of patients with advanced cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(Suppl 2):S293–S295. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02516.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frost MH, et al. Spiritual well-being and quality of life of women with ovarian cancer and their spouses. J Support Oncol. 2012;10(2):72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.suponc.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goldzweig G, et al. Informal caregiving to older cancer patients: preliminary research outcomes and implications. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(10):2635–2640. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goldzweig G, et al. Coping and distress among spouse caregivers to older patients with cancer: an intricate path. J Geriatr Oncol. 2012;3(4):376–385. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2012.07.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burnette D, Duci V, Dhembo E. Psychological distress, social support, and quality of life among cancer caregivers in Albania. Psycho-oncology (Chichester, England) 2017;26(6):779–786. doi: 10.1002/pon.4081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ketcher D, et al. Caring for a spouse with advanced cancer: similarities and differences for male and female caregivers. J Behav Med. 2019;43(5):817–828. doi: 10.1007/s10865-019-00128-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Berg CA, Upchurch R. A developmental-contextual model of couples coping with chronic illness across the adult life span. Psychol Bull. 2007;133(6):920–954. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.6.920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Not applicable.