Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic is a global crisis affecting everyone. Yet, its challenges and countermeasures vary significantly over time and space. Individual experiences of the pandemic are highly heterogeneous and its impacts span and interlink multiple dimensions, such as health, economic, social and political impacts. Therefore, there is a need to disaggregate “the pandemic”: analysing experiences, behaviours and impacts at the micro level and from multiple disciplinary perspectives. Such analyses require multi-topic pan-national survey data that are collected continuously and can be matched with other datasets, such as disease statistics or information on countermeasures. To this end, we introduce a new dataset that matches these desirable properties - the Life with Corona (LwC) survey - and perform illustrative analyses to show the importance of such micro data to understand how the pandemic and its countermeasures shape lives and societies over time.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected everyone, but challenges and countermeasures vary significantly over time and space. Individual experiences are far from uniform (Patel et al., 2020, Benzeval et al., 2020) with impacts present in multiple dimensions, such as (mental) health (Pfefferbaum and North, 2020; Nathiya et al., 2020; Kim and Jung, 2021;Abreu et al., 2021), and economic (Bloom et al., 2020; Bottan et al., 2020; Brodeur et al., 2020), social (Jin et al., 2021; Brück et al., 2020) and political outcomes (Barrios and Hochberg, 2020; Kerr et al., 2021). Significant high-quality data have been collected to provide understanding of the pandemic but data that can connect the dots between places, domains and points in time are so far lacking. Most surveys focus on single issues (e.g. Aristovnik et al., 2020; on education; Krpan et al., 2021, on behaviour; Lazarus et al., 2020 on attitudes to government). Some others collect data in multiple domains but only in narrow time windows, such as Fetzer et al. (2020)A third important set of surveys focuses on specific places (e.g. Blom et al., 2020 in Germany; Hensel et al., 2020, USA; Varshney et al., 2020, India). The addition of COVID-specific questions into long-standing panels, such as Understanding Society and the German Socio-Economic Panel will provide important long-term insights but do not capture the earliest phases of the pandemic. In this article, we introduce Life with Corona (LwC), a new, public survey dataset that collects data in multiple domains, across space, in continuous time since the earliest phases of the pandemic. We present illustrative analyses that show, both, the need for such data and the power of our data to answer questions of this sort.

2. Desirable survey properties

Given the comprehensive nature of the pandemic, we note an urgent demand for social science surveys that facilitate micro-level research across domains, time, and exposure rates. Specifically, this implies the need for a survey with the following desirable properties: (C1) collected throughout the pandemic, including before, during and after lockdowns and peaks in infections; (C2) composed of large numbers of observations, between and within countries; (C3) captures COVID-19 exposure and experiences across multiple domains; (C4) collected from different socio-demographic groups; (C5) allows matching with secondary data, such as data on the spread of the disease or social instability data. To our knowledge, the LwC Survey is currently the only survey to satisfy these criteria.

3. The Life with Corona survey

Life with Corona (LwC) is a multi-year research project (see: https://lifewithcorona.org ). The project provides online survey data that were continuously collected in real time during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is led by an international consortium of researchers, supported by a worldwide network of collaborating institutions (see: https://lifewithcorona.org/network). The online survey is based on a publicly-accessible online questionnaire that can be answered in 27 languages and was launched in March 2020 (fulfilling C1). On October 1, 2020, some modules were slightly adapted, starting “round 2” of data collection. Similarly, the questionnaire was updated one more time on April 29, 2021, starting “round 3” of data collection. At the time of submission, the dataset contains 39,449 observations (including 32,958 pure cross-sectional and 6491 panel observations), collected from 167 countries (C2). The majority of our responses (60%) come from Germany. However, there are a significant number of observations from Argentina (1701), Portugal (1309), USA (1089) and the UK (870). In total, there are 21 countries with more than 150 observations in the data. For more details on the number of responses by country and survey round see: Table 1 .

Table 1.

Survey responses by country and survey round.

| Country | Number of respondents |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-sectional data |

Panel |

||||

| Round 1 | Round 2 | Round 3 | Total | ||

| Germany | 5020 | 15835 | 2684 | 23539 | 3145 |

| Argentina | 1013 | 611 | 77 | 1701 | 356 |

| Portugal | 454 | 822 | 33 | 1309 | 289 |

| USA | 785 | 289 | 15 | 1089 | 390 |

| GB | 540 | 311 | 19 | 870 | 290 |

| Brazil | 327 | 148 | 6 | 481 | 173 |

| India | 281 | 74 | 1 | 356 | 83 |

| Finland | 194 | 115 | 9 | 318 | 143 |

| Spain | 195 | 79 | 6 | 280 | 100 |

| Austria | 131 | 105 | 13 | 249 | 71 |

| Mexico | 59 | 176 | 4 | 239 | 33 |

| Australia | 165 | 68 | 5 | 238 | 76 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 175 | 50 | 1 | 226 | 32 |

| Belgium | 64 | 142 | 7 | 213 | 49 |

| Switzerland | 96 | 104 | 10 | 210 | 60 |

| Italy | 142 | 53 | 5 | 200 | 67 |

| France | 122 | 69 | 4 | 195 | 76 |

| Colombia | 110 | 57 | 27 | 194 | 49 |

| Indonesia | 28 | 161 | 3 | 192 | 12 |

| Canada | 102 | 65 | 8 | 175 | 60 |

| Netherlands | 86 | 68 | 9 | 163 | 54 |

| Other | 1705 | 2678 | 2629 | 7012 | 883 |

Note: The table lists all countries with participants>150. All responses from other countries were pooled into the “Other” category.

The survey covers three themes: Health; Economy; and State & Society (C3). Given the diversity of experiences of the pandemic across individuals, a particular emphasis is placed on measuring “SARS-CoV-2 exposure”, including COVID-19 experiences, perceptions of the pandemic, and behaviours to counter it. The three main themes comprise 12 specific modules: 1) Personal information; 2) Household; 3) Location; 4) Living conditions, 5) SARS-CoV-2 exposure; 5) Work; 6) Income; 7) Food Security; 8) Well-being; 9) Trust; 10) Social relations; 11) Public life; and 12) Personal views. Wherever possible, the survey draws on standard survey tools and specific items that have been validated extensively in various cultures and are considered the ‘gold standard’ across research disciplines. All final survey questions were pre-tested and reviewed by an IRB board.

As face-to-face interviews are difficult to implement during a pandemic, telephone and online interviews have become the predominant questionnaire-based survey modes for collecting micro data pertaining to COVID-19. Both modes have strengths and weaknesses. For phone surveys, random and representative samples may be available, but implementation is costly, sample sizes are modest, and the scope of the questionnaire is limited. Online surveys can be made instantly and freely available to anyone with internet access at any time, which means more individuals can be reached than via phone-based alternatives. A key drawback is that the samples are typically not random and not representative. Potential biases due to self-selection into the sample can be mitigated through the use of statistical weights based on population data (as described below). That way, statistics can be made representative in terms of various demographic dimensions at any level for which population data is available. For this reason, we opted to collect our data via an online survey.

We use snowball and panel sampling to survey individuals across social strata (C4). Participants are invited to retake the survey each quarter. The survey is advertised via Google, social media, newspapers, and networks. This strategy maximises the number of respondents, meeting basic sample size requirements for intra- and international comparisons (see: C2). To mitigate potential biases stemming from this sampling approach, we statistically weight the data. The dataset is weighted by gender and age, and in rounds 2 and 3, also by education. For Germany we additionally include weights by income groups (see: Section S3 in the Online Supplementary Materials for more detailed information). Observations include self-reported sub-national location information (e.g. postcodes in Germany) and are time stamped, enabling spatiotemporal matching with other data (C5). The resulting dataset, including weights, is available in real-time to the LwC network. Members of the research teams at the collaborating institutions have access to weekly updated draws of the data. The data are currently available to anyone upon submission of a request to the LwC team. The most recent draw of the data before the point in time when the request is submitted is provided.

We collect comparable data via phone surveys in four African countries (Brück and Regassa, 2022;see: https://lifewithcorona.org/lwc-africa). The merged phone and online survey dataset will be made publicly available upon publication of this article on the project website and via GESIS (see: https://www.gesis.org/en) Findings are regularly posted on the project website, circulated via our newsletter and social media, and used for teaching.

4. Results from the Life with Corona survey

Below, we discuss various examples of analyses that LwC data enable, due to the defining criteria: across domains (C1), socio-demographic groups (C2), space (C3), time (C4), and data sources (C5). Detailed information on analyzed measures is provided in Section S4 of the Online Supplementary Materials.

4.1. Across domains

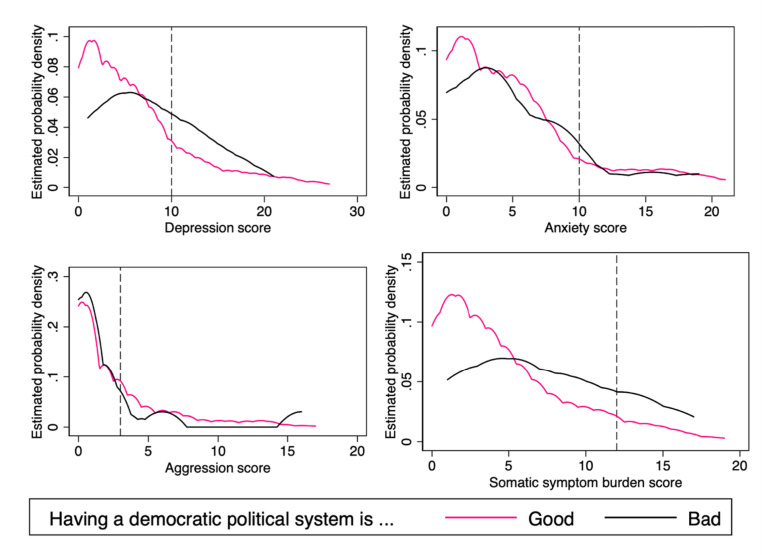

LwC facilitates analyses of interrelated outcomes of key life aspects. For example, we can show that poorer mental health, including depression, anxiety, aggression and somatization, is significantly related to opposing democracy (on average). Comparing kernel density estimates of mental health outcomes between supporters and non-supporters of democracy, we find that medium to high levels of depression and somatic symptom burdens are particularly associated with lower support for democracy (Fig. 1 ). These results not only add evidence for deteriorating mental health during the pandemic but also demonstrate associated risks to political stability and social cohesion, thus informing evidence-based mitigation policies.

Fig. 1.

Democratic preferences and mental health

Note: Kernel density estimates of participants' depression, anxiety, aggression and symptomatic scores by political views. For each mental health outcome, the mean score is significantly higher among those opposing a democratic system than those supporting it (p < .01). The dashed lines indicate thresholds for severe levels of symptoms. Period: October 1, 2020–March 25, 2021. Sample: N = 18,438, weighted based on age, gender and education (observations from countries with less than 150 responses were excluded).

4.2. Across socio-demographic groups

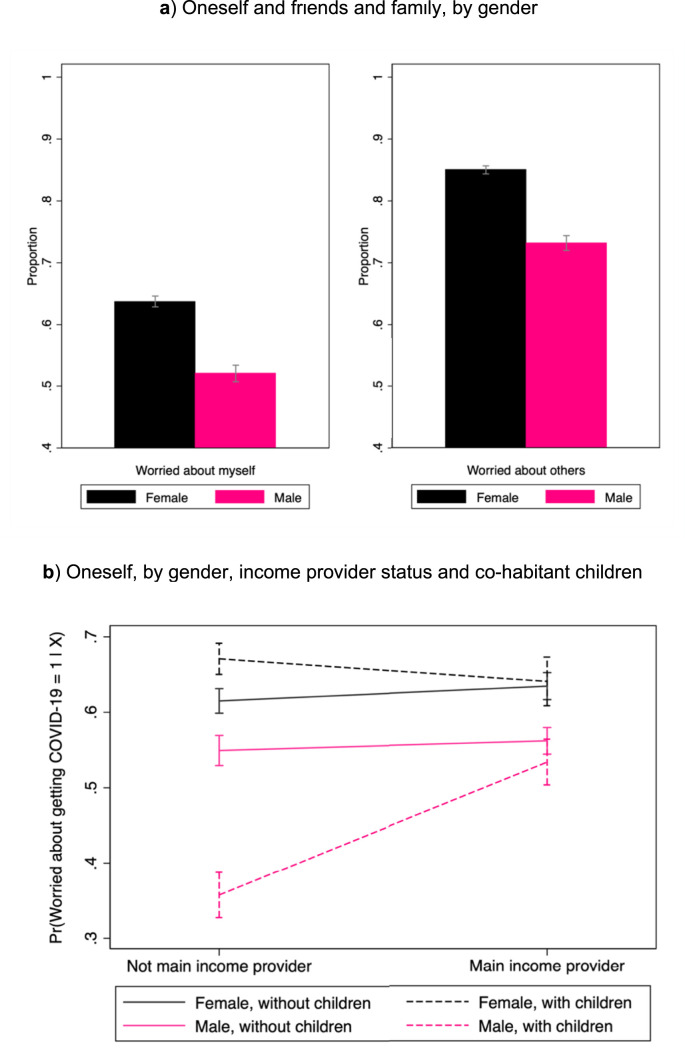

LwC enables us to contrast pandemic experiences across socio-demographic groups. For example, comparisons of weighted mean responses reveal that women are significantly more worried about the disease than men, being both more concerned for themselves and for others (Fig. 2 a). The magnitude of the gender gap is particularly pronounced among those who neither have children nor are the main breadwinner of their household (Fig. 2b). These results have three key implications. First, they highlight the importance of directly surveying worries during a pandemic (and perceptions and beliefs more broadly). Second, they reveal that the pandemic creates new gender disparities (such as pandemic worries) beyond those in commonly discussed domains (such as income). Third, gender critically intersects with other socio-demographic factors in shaping pandemic inequalities.

Fig. 2.

Worries about getting COVID-19 a) Oneself and friends and family, by gender

Note: Unconditional means of “being worried” by sex, with 95% confidence intervals. Period: October 1, 2020–March 25, 2021. Sample: N = 18,438, weighted based on age, gender and education (observations from countries with less than 150 responses were excluded).

b) Oneself, by gender, income provider status and co-habitant children.

Note: Predicted conditional means of “being worried about getting COVID-19”, with 95% confidence intervals. Estimates are based on linear regression of participants' infection worries on gender, income provider status, living with children, and their full interactions, controlling for country fixed effects. Period: October 1, 2020–March 25, 2021. Sample: N = 18,438, weighted based on age, gender and education (observations from countries with less than 150 responses were excluded).

4.3. Across space

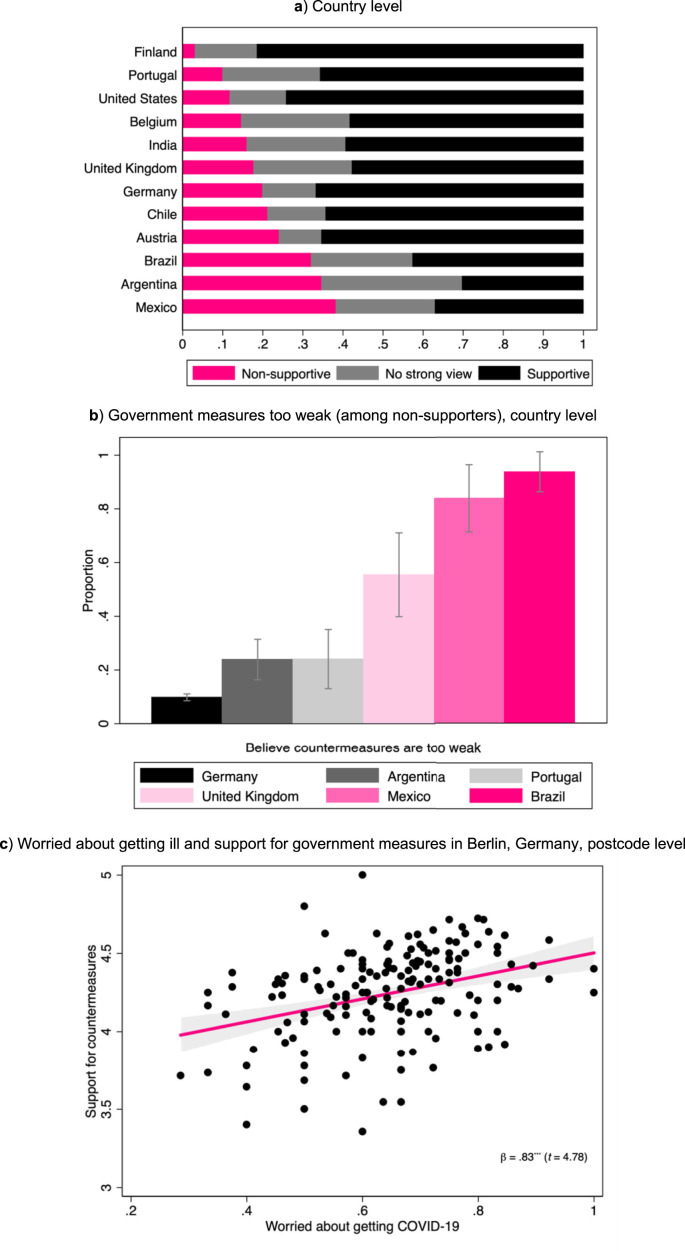

LwC also makes it possible to analyse intra- and international variations in outcomes. For example, simple inspection of the data shows that non-support for government countermeasures ranges from less than 10% to almost 40% across countries (Fig. 3 a). We see a broad range of people who think that measures are too weak, ranging from 10% to 90% (Fig. 3b). In Berlin, Germany, linear regression analysis at the postcode level shows that support is positively and significantly associated with worries about infection at the neighbourhood level (Fig. 3c). These results demonstrate that people's social and political attitudes can vary strongly across localities and that they can also spatially cluster with perception and beliefs pertaining to public health.

Fig. 3.

Support for government measures a) Country level

Note: Country-level shares of respondents who support their government's measures to counter the pandemic. Period: October 1, 2020–March 25, 2021. Sample: N = 18,438, weighted based on age, gender and education (observations from countries with less than 150 responses were excluded). b) Government measures too weak (among non-supporters), country level

Note: Country-level shares of non-supportive respondents who say that their governments' measures to counter the pandemic are too weak. Period: October 1, 2020–March 25, 2021. Sample: N = 2,379, weighted based on age, gender and education (observations from countries with less than 30 ‘unsupportive’ respondents were excluded). c) Worried about getting ill and support for government measures in Berlin, Germany, postcode level

Note: Relationship at the postcode level between the share of respondents worried about getting ill and the mean level of support for countermeasures in Berlin, Germany (scatterplot and linear regression). Period: October 1, 2020–March 25, 2021. Sample: N = 3329 responses from 172 5-digit postcodes (observations from postcodes with less than 5 responses were excluded).

4.4. Across time and panel structure

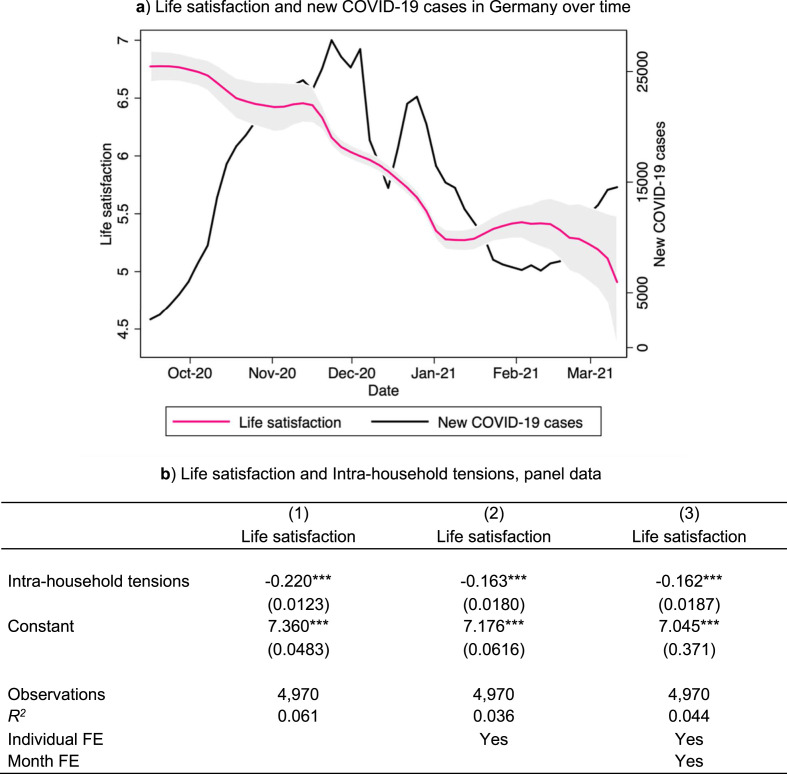

LwC facilitates the study of intertemporal variation in exposure to and consequences of the pandemic, including longitudinal analyses. For example, local polynomial smoothing shows that life satisfaction in Germany almost monotonically decreased from October 2020 until January 2021 (Fig. 4 a). Using our panel observations, linear fixed effects models suggest that intra-household tension is strongly associated with lower life satisfaction (Fig. 4b). This demonstrates that during a pandemic the evolution of individual well-being over time is accompanied by household-level stressors.

Fig. 4.

Life satisfaction a) Life satisfaction and new COVID-19 cases in Germany over time

Note: Kernel-weighted local polynomial smooth of life satisfaction over time, with 95% confidence intervals, and 3-day moving average of new confirmed cases of COVID-19 infections in Germany (Dong et al., 2020). Period: October 1, 2020–March 25, 2021. Sample: N = 15,642, weighted based on age, gender, and education.

b) Life satisfaction and Intra-household tensions, panel data.

Note: Linear panel regressions of the level of life satisfaction on intra-household tensions. Standard errors in parentheses; *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1. Period: March 1, 2020 - March 25, 2021. Sample: N = 4,970 panel responses (rounds 1 and 2).

4.5. Across data sources

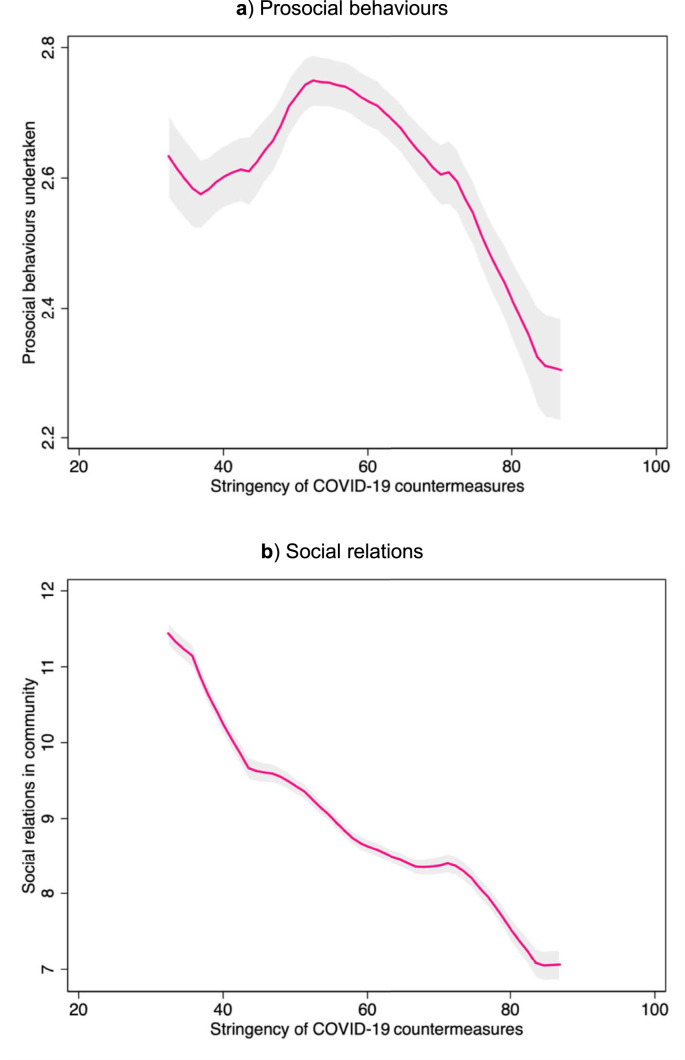

LwC responses can be spatially and temporally matched with external data, based on survey timestamps and respondents' self-reported location. Secondary data may include a variety of data sources at the national and sub-national levels, ranging from public health outcomes (such as daily level of new COVID-19 infections) to policy measures (such as the stringency of countermeasures) to macro-economic indicators (such as the unemployment rate) to social stability indicators. Merging LwC data with countermeasure stringency (Hale et al., 2021), local polynomial smoothing reveals a complex relationship with prosocial behaviour: at low stringency levels, slight increases are associated with more prosocial behaviour, but the opposite holds at higher stringency levels (Fig. 5 a). At the same time, individuals perceive social relations to worsen as stringency rises (Fig. 5b). These results emphasise that the impacts of the pandemic and its countermeasures on social cohesion are complex and potentially non-linear. While ‘low-intensity’ lockdowns can bring communities together, high-intensity lockdowns can drive them apart.

Fig. 5.

Social behaviours and policy stringency a) Prosocial behaviours

Note: Kernel-weighted local polynomial smooth of total number of prosocial behaviours over the stringency level of the national COVID-19 countermeasures on the day of the survey response (Hale et al., 2021), with 95% confidence intervals. Period: October 1, 2020–March 25, 2021. Sample: N = 18,438, weighted based on age, gender and education (observations from countries with less than 150 responses were excluded).

b) Social relations

Note: Kernel-weighted local polynomial smooth of social relations index over the stringency level of the national COVID-19 countermeasures in the day of reporting (Hale et al., 2021), with 95% confidence intervals. Period: October 1, 2020–March 25, 2021. Sample: N = 18,438, weighted based on age, gender and education (observations from countries with less than 150 responses were excluded).

5. Discussion

Even though the ‘acute phase’ of the pandemic might now have ended in countries with high rates of immunisation, the crises created by the pandemic will have lasting heterogeneous impacts. New, multi-topic, micro-level data are required to understand these impacts, how they are interrelated and how they shape the post-pandemic world. In this article, we show the power of such data in the form of the LwC data. Analyses using LwC data allow us to advance our understanding of the multidimensional challenges, inequalities and other impacts the pandemic and its countermeasures have created, and continue to create, for societies around the world.

Funding source

German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF).

UK Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC).

United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU-WIDER).

Alexander von Humboldt Foundation.

Role of funding source

The funding sources had no involvement in the data collection, analysis, interpretation of data, in the writing of the articles, and in the decision to submit it for publication.

Credit author statement

Wolfgang Stojetz: Conceptualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing

Neil T. N. Ferguson: Conceptualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing

Ghassan Baliki: Methodology, Writing - review & editing

Oscar Díaz: Data analysis, Writing - review & editing

Jan Elfes: Data curation, Writing - review & editing

Damir Esenaliev: Methodology, Writing - review & editing

Hanna Freudenreich: Data curation, Writing - review & editing

Anke Koebach: Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing

Liliana Abreu: Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing

Laura Peitz: Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing

Ani Todua: Data curation, Writing - review & editing

Monika Schreiner: Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing

Anke Hoeffler: Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing

Patrícia Justino: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing - review & editing

Tilman Brück: Supervision, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing - review & editing

Submission declaration and verification

The work described has not been published previously. It is not under consideration for publication elsewhere and its publication is approved by all authors. If accepted, it will not be published elsewhere in the same form, in English or in any other language, including electronically without the written consent of the copyright holder.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Acknowledgment

We gratefully acknowledge support from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF), the UK Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), and the United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU-WIDER). Anke Hoeffler acknowledges funding from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation. For excellent support with information technology, software, and website design, we thank Klaus Hartl and Nils Henrik Johansson. For excellent support with project and partnership management, we thank Philip Albers, Iina Kuttila, Eeva Nyyssönen, Myroslava Purska, Babette Regierer, Petra Rietzler, Gabija Verbaite, and Julia Vogt. For excellent support with data collection and analysis, we thank Samuel Carleial, Lea Ellmanns, Helena Meier, Mekdim D. Regassa, Andrej Smirnov, and Dorothee Weiffen.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.115109.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Abreu L., Koebach A., Diaz O., Carleial S., Hoeffler A., Stojetz W, et al. Life with Corona: increased gender differences in aggression and depression symptoms due to the COVID-19 pandemic burden in Germany. Front. Psychol. 2021;12:1–21. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.689396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aristovnik A., Keržič D., Ravšelj D., Tomaževič N., Umek L. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on life of higher education students: a global perspective. Sustainability. 2020;12(20):8438. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2021.107659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrios J.M., Hochberg Y. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 27008; 2020. Risk Perception through the Lens of Politics in the Time of the COVID-19 Pandemic. [Google Scholar]

- Benzeval M., Burton J., Crossley T.F., Fisher P., Jäckle A., Low H., Read B. 2020. The idiosyncratic impact of an aggregate shock: the distributional consequences of COVID-19.https://ssrn.com/abstract=3615691 Available at: SSRN: [Google Scholar]

- Blom A.G., Cornesse C., Friedel S., Krieger U., Fikel M., Rettig T., et al. vol. 14. 2020. High frequency and high quality survey data collection; pp. 171–178. (Survey Research Methods). No. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom D.E., Kuhn M., Prettner K. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 27757; 2020. Modern Infectious Diseases: Macroeconomic Impacts and Policy Responses. [Google Scholar]

- Bottan N., Hoffmann B., Vera-Cossio D. The unequal impact of the coronavirus pandemic: evidence from seventeen developing countries. PLoS One. 2020;15(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodeur A., Gray D., Islam A., Bhuiyan S. A literature review of the economics of COVID-19. J. Econ. Surv. 2020 doi: 10.1111/joes.12423. Available at: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brück T., Ferguson N.T.N., Justino P., Stojetz W. IZA Discussion Paper 13386; 2020. Trust in the Time of Corona. [Google Scholar]

- Brück T., Regassa M. Phone surveys on COVID-19 and food security in Africa. Unpublished paper. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s12571-022-01330-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong E., Du H., Gardner L. An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20(5):533–534. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30120-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fetzer T.R., Witte M., Hensel L., Jachimowicz J., Haushofer J., Ivchenko A., et al. Global Behaviors and Perceptions at the Onset of the COVID-19 Pandemic. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hale T., Angrist N., Goldszmidt R., Kira B., Petherick A., Phillips T., et al. A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker) Nat. Human Behav. 2021;5(4):529–538. doi: 10.1038/s41562-021-01079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensel D.J., Rosenberg M., Luetke M., Fu T.C., Herbenick D. MedRxiv; 2020. Changes in Solo and Partnered Sexual Behaviors during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Findings from a US Probability Survey. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin S., Balliet D., Romano A., Spadaro G., Van Lissa C.J., Agostini M., et al. Intergenerational conflicts of interest and prosocial behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2021;171 doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr J., Panagopoulos C., van der Linden S. Political polarization on COVID-19 pandemic response in the United States. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2021;179 doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2021.110892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.H.S., Jung J.H. Social isolation and psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-national analysis. Gerontol. 2021;61(1):103–113. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnaa168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krpan D., Makki F., Saleh N., Brink S.I., Klauznicer H.V. When behavioural science can make a difference in times of COVID-19. Behav. Publ. Pol. 2021;5(2):153–179. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus J.V., Ratzan S., Palayew A., Billari F.C., Binagwaho A., Kimball S., et al. COVID-SCORE: A global survey to assess public perceptions of government responses to COVID-19 (COVID-SCORE-10) PLoS One. 2020;15(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathiya D., Singh P., Suman S., Raj P., Tomar B.S. Mental health problems and impact on youth minds during the COVID-19 outbreak: cross-sectional (RED-COVID) survey. Social Health Behav. 2020;3(3):83. [Google Scholar]

- Patel J.A., Nielsen F.B.H., Badiani A.A., Assi S., Unadkat V.A., Patel B., et al. Poverty, inequality and COVID-19: the forgotten vulnerable. Publ. Health. 2020;183:110. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum B., North C.S. Mental health and the Covid-19 pandemic. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;383(6):510–512. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2008017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varshney M., Parel J.T., Raizada N., Sarin S.K. Initial psychological impact of COVID-19 and its correlates in Indian Community: an online (FEEL-COVID) survey. PLoS One. 2020;15(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0233874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.