Abstract

O-Methyltransferase I catalyzes both the conversion of demethylsterigmatocystin to sterigmatocystin and the conversion of dihydrodemethylsterigmatocystin to dihydrosterigmatocystin during aflatoxin biosynthesis. In this study, both genomic cloning and cDNA cloning of the gene encoding O-methyltransferase I were accomplished by using PCR strategies, such as conventional PCR based on the N-terminal amino acid sequence of the purified enzyme, 5′ and 3′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends PCR, and thermal asymmetric interlaced PCR (TAIL-PCR), and genes were sequenced by using Aspergillus parasiticus NIAH-26. A comparison of the genomic sequences with the cDNA of the dmtA region revealed that the coding region is interrupted by three short introns. The cDNA of the dmtA gene is 1,373 bp long and encodes a 386-amino-acid protein with a deduced molecular weight of 43,023, which is consistent with the molecular weight of the protein determined by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The C-terminal half of the deduced protein exhibits 76.3% identity with the coding region of the Aspergillus nidulans StcP protein, whereas the N-terminal half of dmtA exhibits 73.0% identity with the 5′ flanking region of the stcP gene, suggesting that translation of the stcP gene may start at a site upstream from methionine that is different from the site that has been suggested previously. Also, an examination of the 5′ and 3′ flanking regions of the dmtA gene in which TAIL-PCR was used demonstrated that the dmtA gene is located in the aflatoxin biosynthesis cluster between (and in the same orientation as) the omtA and ord-2 genes. Northern blotting revealed that expression of the dmtA gene is influenced by both medium composition and culture temperature and that the pattern correlates with the patterns observed for other genes in the aflatoxin gene cluster. Furthermore, Southern blotting and PCR analyses of the dmtA gene showed that a dmtA homolog is present in Aspergillus oryzae SYS-2.

Aflatoxins are secondary metabolites produced by certain strains of Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus parasiticus, Aspergillus nomius, and Aspergillus tamarii. Aflatoxins are known to be highly toxic, mutagenic, and carcinogenic to animals and humans, and contamination of agricultural commodities with aflatoxins can have serious effects on the health of animals and humans (6). In order to devise effective methods for preventing aflatoxin contamination of feed and food, elucidation of the aflatoxin biosynthetic mechanism in fungi is important. The pathways for aflatoxin biosynthesis have been extensively studied, and it is known that at least 18 enzymatic steps are required for conversion of acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) to its final products, aflatoxins B1, B2, G1, and G2. The generally accepted pathway for aflatoxin B1 formation is as follows: acetyl-CoA–hexanoyl-CoA–norsolorinic acid–averantin–5′-hydroxyaverantin–averufin–versiconal hemiacetal acetate–versiconal–versicolorin B—versicolorin A–demethylsterigmatocystin–sterigmatocystin–O-methylsterigmatocystin–aflatoxin B1 (1, 5, 22, 30–33, 36). Involvement of averufanin in aflatoxin biosynthesis has not been confirmed with cell-free systems or in vivo feeding experiments (29a). Recently, several enzymes have been purified, and many genes encoding the enzymes and the transcription factor have been cloned and characterized; these genes include nor-1, ver-1, omtA, and aflR (reviewed in references 25 and 29). These genes have been shown to form a gene cluster located in an approximately 75-kb region in the A. flavus and A. parasiticus genomes, although there are minor differences between the species (29, 39).

On the other hand, several fungi (Aspergillus nidulans, Bipolaris spp., Chaetomium spp., Farrowia spp., Monocillium spp., et al.) produce sterigmatocystin, a precursor of aflatoxins, and it has been suggested that pathways almost identical to the aflatoxin biosynthesis pathway may also be involved in sterigmatocystin biosynthesis; in fact, genes similar to the genes involved in aflatoxin biosynthesis have been isolated from A. nidulans, and it has been found that these genes are located in a 60-kb cluster in the A. nidulans genome (3, 14, 25).

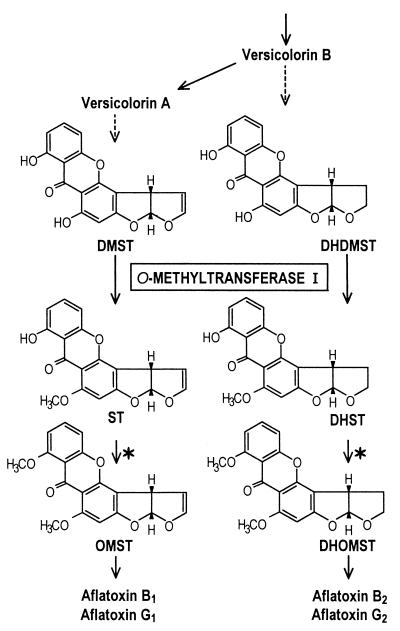

During biosynthesis of aflatoxins, two different O-methyltransferases are involved; on the basis of the order of the reactions (Fig. 1) these enzymes are designated O-methyltransferase I (MT-I) and O-methyltransferase II (MT-II) (33). MT-II, which is involved in the conversion of sterigmatocystin to O-methylsterigmatocystin and the conversion of dihydrosterigmatocystin to dihydro-O-methylsterigmatocystin, has been purified (2, 13), and the gene encoding the enzyme been isolated from A. parasiticus and A. flavus (37, 38). This gene was designated omtA (38), although the same gene was designated omt-1 previously (37). The gene encoding MT-I has not been identified previously. Kelkar et al. recently sequenced an stcP gene from the sterigmatocystin gene cluster of A. nidulans and through gene disruption determined that it is involved in the conversion of demethylsterigmatocystin to sterigmatocystin (12). These authors assumed that the 612-bp stcP open reading frame encodes a protein containing 204 amino acids. However, the gene homologous to stcP has not been isolated from aflatoxigenic fungi, such as A. flavus and A. parasiticus. Thus, the goal of this study was to clone a gene encoding MT-I from A. parasiticus and characterize it.

FIG. 1.

Metabolic scheme for biosynthesis of aflatoxins B1, G1, B2, and G2, showing the structures of critical intermediates. The reactions catalyzed by MT-I are indicated, and the reactions catalyzed by MT-II are indicated by asterisks. Solid arrows, enzymologically confirmed reactions; dashed arrows, unconfirmed reactions. DMST, demethylsterigmatocystin; DHDMST, dihydrodemethylsterigmatocystin; ST, sterigmatocystin; DHST, dihydrosterigmatocystin; OMST, O-methylsterigmatocystin; DHOMST, dihydro-O-methylsterigmatocystin.

We recently purified MT-I from A. parasiticus (34). Here we describe cloning of the cDNA and genomic DNA encoding MT-I from A. parasiticus NIAH-26 by rapid amplification of cDNA ends PCR (RACE-PCR) and thermal asymmetric interlaced PCR (TAIL-PCR) (21). We designated the gene obtained dmtA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fungal strains and culture conditions.

A. parasiticus NIAH-26, a UV-irradiated mutant of A. parasiticus SYS-4 (= NRRL-2999), was used in this study (35). This fungus induces all enzymes during conversion of norsolorinic acid to aflatoxins in aflatoxin-inducible media, such as YES medium (2% [wt/vol] yeast extract, 20% [wt/vol] sucrose) and SY medium (6% [wt/vol] sucrose, 2% [wt/vol] yeast extract), although it produces neither aflatoxins nor anthraquinone or xanthone precursors (30–33, 36). A nonaflatoxigenic strain, Aspergillus oryzae SYS-2 (= IFO 4251), was also used. Each fungus was grown in a potato dextrose agar (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) at 28°C for 1 week, and the conidiospores were then collected as described previously (31).

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

To clone the PCR product, the product was ligated into TA cloning vector pCR 2.1 and then transformed into bacterial strain INVaF′ (Invitrogen BV, Groningen, The Netherlands).

Determination of the amino acid sequence of MT-I.

MT-I was purified as described previously (34) and was analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) by using a 13% polyacrylamide gel (19). The protein was blotted onto a polyvinylidine difluoride membrane (Immobilon P; Millipore Corp., Bedford, Mass.) by using a semidry blotting system (model AE 6675; Atto Co., Tokyo, Japan), and the part corresponding to MT-I in the membrane was cut out and applied to an automated Edman degradation gas phase sequencer (model G 1000A; Hewlett-Packard Co., Palo Alto, Calif.).

Preparation of the genomic DNAs of fungi and plasmid DNA.

DNAs were purified from A. parasiticus NIAH-26 and A. oryzae SYS-2 by using the method of Ullrich et al. (26), with some modifications. A spore suspension (containing approximately 5 × 108 spores) was inoculated into 100 ml of YES medium and cultured without agitation at 28°C in the dark for 4 days. The mycelia were harvested, lyophilized, ground with a mortar with a pestle, and extracted with a solution containing 0.15 M NaCl, 0.1 M sodium EDTA, 50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0), 2% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 0.2 volume of toluene. The DNA was purified further by performing two phenol extractions followed by ethanol precipitation.

For the PCR analyses, a spore suspension was inoculated into 100 ml of Czapek medium (Difco Laboratories) and incubated on a shaker (200 rpm) at 28°C for 3 days. DNA was extracted from the mycelia with an ISOPLANT kit (Wako Nippon Gene, Tokyo, Japan).

To screen the transformed bacteria by TA cloning, plasmid DNA was purified by alkaline lysis miniprep (24). To prepare highly purified plasmid DNA for DNA sequencing, a QIAprep Spin Miniprep kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) was used.

Preparation of total RNA and poly(A) RNA.

Either A. parasiticus NIAH-26 or A. oryzae SYS-2 was cultured in YES medium without agitation at 28°C for 4 days, and then the total RNA was extracted from the mycelia by the guanidium thiocyanate method (24). To prepare cDNA for RACE-PCR, polyadenylated [poly(A)+] RNA was purified by using an oligo(dT)-cellulose column-based mRNA purification kit (Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden).

For Northern blotting, a spore suspension (containing approximately 5 × 108 spores) was inoculated into 100 ml of either liquid SY medium (an aflatoxin-inducing medium) or liquid PY medium (4% peptone, 2% yeast extract) (a non-aflatoxin-inducing medium) (18), and the culture was incubated at either 28°C (permissive temperature for aflatoxin production) or 37°C (nonpermissive temperature) (7) for 3 days on a rotary shaker (100 rpm); then the mycelia were harvested. The total RNA was extracted with an RNeasy plant mini kit (QIAGEN).

Primers and PCR apparatus.

The primers used in this work are shown in Table 1. All PCRs except RACE-PCRs were performed by using Ready-to-Go beads (Pharmacia) and the conditions shown in Table 2. A model 9700 thermal cycler and a model 9600 thermal cycler (both obtained from Perkin-Elmer Cetus, Norwalk, Conn.) were used, although only the model 9600 thermal cycler was used for the TAIL-PCR because a nine-step reaction was possible only with this model.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used as primers for PCRs

| Primer | Sequencea | Positions |

|---|---|---|

| Degenerate primers | ||

| mt-I 1F | 5′-ACNGGNYTNGAYATGGARAT-3′ | 4 to 23 |

| mt-I 1R | 5′-GCNARNCKCATNACNACRTC-3′b | 149 to 130 |

| RACE-PCR primers | ||

| GSP1 | 5′-GCCAGAACAGACGATGTGGGCAAACGGC-3′ | 52 to 79 |

| GSP2 | 5′-GCCGACCTGAAGCTCGCGGATATGGCCC-3′ | 114 to 87 |

| NGSP1 | 5′-GAGTGGATGCCACAGCATCCCAAGCACA-3′ | 710 to 737 |

| AP1 | 5′-CCATCCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGC-3′ | Adapter |

| TAIL-PCR primers | ||

| TAIL1 | 5′-TTGCCGTTTGCCCACATCGTCTGTT-3′ | 81 to 57 |

| TAIL2 | 5′-ACCCTACCACTTTCGACAGGCGGTA-3′ | −8 to −32 |

| TAIL3 | 5′-GGTCCCTGAGCCAGGGGTATTTGTT-3′ | −85 to −109 |

| TAIL4 | 5′-TGATGAACTCTCTCGGCGGAGTAGA-3′ | 1194 to 1218 |

| TAIL5 | 5′-GGTGGGTCTGGAAATTATCCAGTCA-3′ | 1255 to 1279 |

| TAIL6 | 5′-CCCCAGACTAGCCCAGTAGATAAAT-3′ | 1343 to 1367 |

| RA1c | 5′-NGTCGASWGANAWGAA-3′ | |

| RA2d | 5′-NCAGCTWSCTNTSCTT-3′ | |

| RA3c | 5′-GTNCGASWCANAWGTT-3′ | |

| RA4d | 5′-CANGCTWSGTNTSCAA-3′ | |

| RA5c | 5′-WGTGNAGWANCANAGA-3′ | |

| RA6d | 5′-SCACNTCSTNGTNTCT-3′ | |

| Primers used to determine the internal and flanking regions | ||

| mt-I 2Fe | 5′-ACAAATACCCCTGGCTCAGG-3′ | −108 to −89 |

| mt-I 2Re | 5′-ACCTGTTCCATCAAATCGTC-3′b | 1257 to 1238 |

| mt-I 3F | 5′-CAGCCTCAAAGAGAGCGACACGCCA-3′ | 270 to 294 |

| mt-I 3R | 5′-TAAATGACCGAGTGATTCCATGTGC-3′ | 757 to 733 |

| omtA 1F | 5′-CGGACCATGCAAGTTTACGC-3′ | −703 to −684 (2104 to 2123)f |

| ord-2 1R | 5′-AACGTGAACTTGTGGGCGTC-3′ | 1683 to 1664 (155 to 174)g |

N = A, C, G, or T; K = G or T; R = A or G; S = C or G; W = A or T; Y = C or T.

The underlined nucleotides differ from the nucleotides obtained from cDNA and genomic DNA sequences (Fig. 2).

Constructed by using the method of Liu and Whittier (21).

Constructed in this study by using the method of Liu and Whittier (21).

Primer also used for Northern and Southern analyses.

The position numbers in parentheses correspond to the genomic DNA sequence of the omtA gene (38).

The position numbers in parentheses correspond to the cDNA sequence of the ord-2 gene (39).

TABLE 2.

Cycling conditions used for PCR experiments

| Reaction | No. of cycles | Thermal conditions |

|---|---|---|

| PCR with degenerate primers | 1 | 94°C (5 min) |

| 35 | 94°C (1 min), 40°C (2 min), 72°C (3 min) | |

| 1 | 72°C (7 min), 4°C (∞) | |

| PCR used to determine internal regions of the gene | 1 | 94°C (5 min) |

| 35 | 94°C (1 min), 50°C (2 min), 72°C (3 min) | |

| 1 | 72°C (7 min), 4°C (∞) | |

| PCR used to determine flanking regions of the gene | 1 | 94°C (5 min) |

| 35 | 94°C (1 min), 57°C (1 min), 72°C (1 min) | |

| 1 | 72°C (7 min), 4°C (∞) | |

| Tail-PCRa | ||

| Primary | 1 | 94°C (5 min), 95°C (1 min) |

| 5 | 94°C (1 min), 64°C (1 min), 72°C (3 min) | |

| 1 | 94°C (1 min), 27.5°C (3 min), ramping to 72°C over 3 min, 72°C (3 min) | |

| 15 | 94°C (30 s), 64°C (1 min), 72°C (3 min) | |

| 94°C (30 s), 64°C (1 min), 72°C (3 min) | ||

| 94°C (30 s), 44°C (1 min), 72°C (3 min) | ||

| 1 | 72°C (5 min), 4°C (∞) | |

| Secondary | 1 | 94°C (5 min) |

| 12 | 94°C (30 s), 64°C (1 min), 72°C (3 min) | |

| 94°C (30 s), 64°C (1 min), 72°C (3 min) | ||

| 94°C (30 s), 44°C (1 min), 72°C (3 min) | ||

| 1 | 72°C (5 min), 4°C (∞) | |

| Tertiary | 1 | 94°C (5 min) |

| 10 | 94°C (30 s), 64°C (1 min), 72°C (3 min) | |

| 94°C (30 s), 64°C (1 min), 72°C (3 min) | ||

| 94°C (30 s), 44°C (1 min), 72°C (3 min) | ||

| 1 | 72°C (30 min), 4°C (∞) |

The program used was the program described by Liu and Whittier (21), with minor modifications.

cDNA synthesis and 5′- and 3′-RACE-PCRs.

To obtain the full-length cDNA sequence, mRNA (1 μg) was used to generate double-stranded cDNA with a Marathon cDNA amplification kit (CLONTECH Laboratory, Inc., Palo Alto, Calif.), and the double-stranded cDNA was ligated with a Marathon cDNA adaptor. 3′-RACE was performed by using the double-stranded cDNA as a template, a dmtA gene-specific primer (primer GSP1), and adapter primer AP1. An additional gene-specific primer, primer NGSP1, was also used for 3′-RACE in order to determine the complete sequence of the cDNA. 5′-RACE was performed by using the cDNA as a template, a dmtA gene-specific primer (primer GSP2), and adapter primer AP1. The PCR products resulting from both 5′-RACE and 3′-RACE were gel purified, ligated into vector TA, and sequenced.

Cloning of genomic DNA and TAIL-PCR.

To determine the internal sequence of the genomic dmtA gene, PCRs were performed by using the genomic DNA of A. parasiticus NIAH-26 as the template and various primers having the cDNA sequence (primers mt-I 2F, mt-I 2R, mt-I 3F, and mt-I 3R), and the resulting PCR products were sequenced.

To determine the sequences of the 5′ and 3′ flanking regions, TAIL-PCR was used. This technique consists of consecutive PCRs performed with nested sequence-specific primers and a shorter arbitrary degenerate primer. Three nested sequence-specific primers (primers TAIL1, TAIL2, and TAIL3) for the dmtA gene and six random primers were used to amplify the 5′ upstream region in Ready-to-Go PCR tubes (Pharmacia). All of the random primers were kind gifts from K. Yamagishi, Tohoku National Agricultural Experiment Station, Fukushima, Japan. Three other primers, primers TAIL4, TAIL5, and TAIL6, were used to amplify the 3′ downstream regions of the dmtA gene. Six kinds of TAIL-PCRs were performed with six random primers at the same time. After three successive nested PCRs with TAIL cycling (Table 2) performed with the model 9600 thermal cycler, the reaction products of the secondary and tertiary PCR steps were separated and compared on the same agarose gel. All of the bands from the tertiary PCRs which showed the expected decrease in length, which was consistent with the differences in the positions of the sequences of primers TAIL2 and TAIL3 or primers TAIL5 and TAIL6 on the genome, were assumed to be the desired products and were then cut out, cloned, and sequenced. In order to rule out PCR mismatches during many repetitions in the TAIL-PCR analysis, we confirmed the nucleotide sequences resulting from TAIL-PCR by performing conventional PCR either with primers TAIL3 and omtA 1F or with primers TAIL4 and ord-2 1R.

DNA sequence analysis.

All PCR products were ligated into vector TA, cloned, and sequenced. A DNA sequence analysis was performed for both strands by using M13 reverse and forward primers and an ABI Prism BigDye terminator cycle sequencing Ready Reaction kit (The Perkin-Elmer Corp.). Every sequence was confirmed by examining both strands; in addition, at least two bacterial clones obtained by TA cloning were examined.

Southern and Northern analyses.

For Southern analysis, 10 μg of A. parasiticus NIAH-26 or A. oryzae SYS-2 genomic DNA was completely digested with either HindIII or EcoRI restriction endonuclease. Digested DNA fragments were separated on a 1.0% agarose gel together with DNA molecular weight marker VII and digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled DNA molecular weight marker VI (Boehringer Mannheim GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). For Northern analysis, total RNA samples (7 μg) and DIG-labeled RNA molecular weight marker I (Boehringer Mannheim) were separated on a 1.2% agarose–formaldehyde gel. DNA or RNA fragments were blotted onto a nylon membrane (Boehringer Mannheim) by using a VacuGene XL vacuum system (Pharmacia), followed by UV cross-linking (model UVC 500 UV crosslinker; Hoefer). To prepare the probe for Southern and Northern analyses, the PCR products made by using the genomic DNA as a template with primers mt-I 2F and mt-I 2R (Table 2) were cloned into the TA vector. The plasmid DNA was cut with restriction enzyme EcoRI, and the resulting DNA fragment containing the PCR product was labeled with DIG-High Prime (Boehringer Mannheim). The membranes were then probed with the DIG-labeled DNA fragment, and the hybridized DNA band was immunodetected by using a Detection DIG luminescent detection kit (Boehringer Mannheim).

Computer analyses of sequence data.

Computer analyses of nucleotide sequence data were performed by using the Wisconsin Genetics Computer Group (GCG) package. Translation of the nucleotide sequences into amino acid sequences and the search for sequence motifs was carried out by using the Genetic Mac software program.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The genomic and cDNA nucleotide sequence data for dmtA have been deposited in the DDBJ, EMBL, and GenBank nucleotide sequence databases under accession no. AB022905 and AB022906, respectively.

RESULTS

Determination of N-terminal amino acid sequence of MT-I.

We purified MT-I from A. parasiticus NIAH-26 to homogeneity. Its molecular weight was 43,000 (as determined by SDS-PAGE) (34). The N-terminal sequence consisted of 51 amino acid residues, and three positions had two possible candidate amino acids because of ambiguity of the signals, as follows: T - G - L - D - M - E - I - I - F - A - K - I - K - E - E - Y - A - R - T - D - D - V - G - K - R - Q - I - Q - G - H - I - R - E - L - Q - V - G - F - Y - S(P) - D - L(W) - D - V - V - M - R -L-A(S)-S-G-. The presence of an unblocked N-terminal threonine indicates that the N terminus may have been posttranslationally processed.

BLAST analysis revealed that the 48 amino acid residues from the fifth amino acid to the last amino acid exhibited 72% identity with amino acid sequences putatively encoded by the A. nidulans sterigmatocystin biosynthetic gene cluster (GenBank accession no. ENU34740; positions 43273 to 43130). However, the nucleotides encoding these amino acid sequences occurred between the stcO and stcP genes and were located in the 5′ flanking region of stcP. Therefore, we speculated that the coding part of stcP that Kelkar et al. described (12) may actually be the C-terminal part of an undetermined whole larger enzyme.

Cloning and nucleotide sequencing of MT-I cDNA and the deduced amino acid sequence.

In order to determine the specific nucleotide sequence of dmtA, we used degenerate oligonucleotides mt-I 1F and mt-I 1R, which corresponded to the N-terminal sequence of the MT-I protein. A 144-bp PCR product was obtained. The deduced amino acid of this product sequence was consistent with the whole N-terminal amino acid sequence of the MT-I protein, but amino acids 41, 43, and 50 were confirmed to be S, W, and S, respectively, and not P, L, and A.

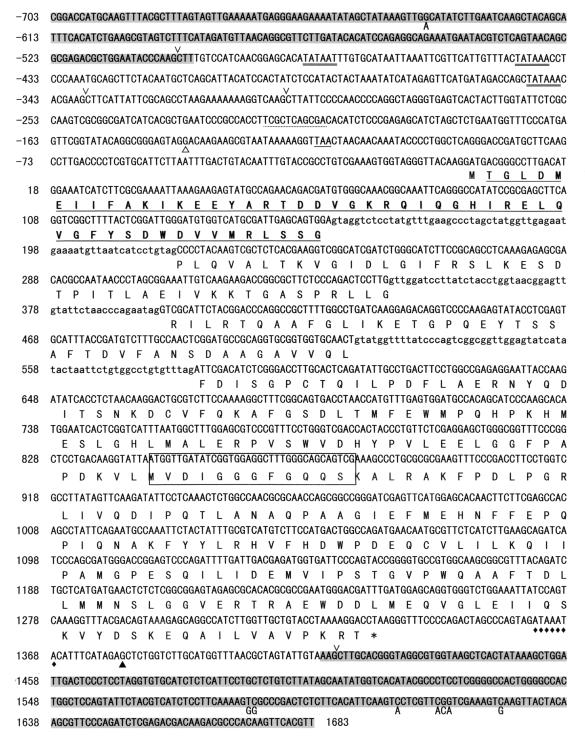

We then used 5′-RACE and 3′-RACE techniques to determine the cDNA sequence of the dmtA gene. The nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences for the dmtA regions are shown in Fig. 2. Following 5′-RACE-PCR four transformed TA clones were randomly picked and sequenced. The 5′ ends of two of these clones were at position −140, whereas the 5′ ends of the other clones were at positions −77 and −22. We assumed that the site at position −140 was a transcription start site, and the overall cDNA sequence was determined to be 1,373 bp long. The first M at position +1 to +3 may later be processed posttranslationally. The open reading frame of the cDNA codes for a 386-amino-acid protein, and the theoretical molecular mass of this protein without the N-terminal methionine was calculated to be 43,023 Da, which corresponded well to the mass determined by SDS-PAGE (43 kDa) (34). The polyadenylation occurred 44 nucleotides downstream after the translation stop codon (TAA; positions 1334 to 1336). Although three kinds of consensus motifs (motifs I, II, and II) of S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferase have recently been described (11), DmtA contains only motif I in the central region (10).

FIG. 2.

Nucleotide sequence of the dmtA gene of A. parasiticus and deduced amino acid sequence. The first nucleotide of the translational initiation codon was assigned position +1. The deduced amino acid sequence (one-letter designations) is shown below the nucleotide sequence. Amino acid residues are numbered beginning with the initiating methionine, whereas this methionine is processed translationally. A nonsense codon preceding the initiation codon in the same reading frame is underlined. The start of the dmtA cDNA sequence is indicated by an open triangle. The polyadenylation site is indicated by a solid triangle. A potential polyadenylation signal sequence is indicated by diamonds. The three intron sequences are indicated by lowercase letters. The consensus S-adenosylmethionine binding site is enclosed with a box. Putative TATA boxes are underlined with double lines. The substituted nucleotides in the A. parasiticus omtA and ord-2 gene sequences are indicated under the corresponding positions. The underlined amino acid sequences correspond to the sequences determined for the purified 43-kDa MT-I protein from A. parasiticus. The regions similar to omtA regions (positions −703 to −499) (38) and ord-2 regions (positions 1415 to 1683) (39) are shaded. HindIII restriction sites are indicated by wedges.

Cloning and nucleotide sequence of the genomic dmtA gene and its flanking regions.

We then analyzed the genomic sequence of dmtA by performing conventional PCR and TAIL-PCR with oligonucleotides mt-I 2F, mt-I 2R, mt-I 3F, and mt-I 3R, which were synthesized on the basis of the cDNA nucleotide sequence. We compared the cDNA sequence with the genomic DNA sequence and confirmed that the consensus splicing sequence (GT---AG) was present; this analysis showed that the coding sequence of dmtA (nucleotides 1 to 1333) was separated by three introns consisting of 63 bp (nucleotides 157 to 219), 50 bp (nucleotides 347 to 396), and 62 bp (nucleotides 521 to 582). In addition, the palindrome sequence TCG(N5)CGA, which has been suggested as a possible binding region of AflR in A. nidulans (8), was found at positions −216 to −206. Three TATAA sequences close to the transcription initiation site were found at positions −479 to −474, −442 to −437, and −350 to −345.

Using TAIL-PCR, we obtained a PCR product containing the homologous region of omtA found in A. flavus and A. parasiticus (37, 38). The presence of omtA was confirmed by performing a conventional PCR with a primer (primer omtA 1F) constructed on the basis of a previously published sequence (38). Consequently, we could sequence 563 bp of the flanking region 5′ with respect to the transcription start site, and we determined that the sequence of the region from position −703 to position −499 overlapped the 3′ flanking region of the omtA gene. The orientations of dmtA and omtA were the same.

We also found that the 3′ flanking region of dmtA (positions 1415 to 1683) overlapped the 5′ cDNA sequence of ord-2 (39), and the orientations of dmtA and ord-2 were also the same. Interestingly, the distance between the polyadenylation site of dmtA and the 5′ transcription start site of the ord-2 gene was short (34 bp), and no TATAA motif was detected in this region, even in the 3′ region of dmtA (positions 716 to 1683).

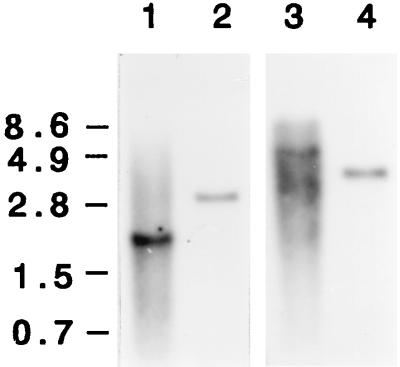

Southern analysis of dmtA.

During sequencing of dmtA with PCR, the patterns of the PCR products suggested that dmtA is a single-copy gene (data not shown). In order to confirm this, genomic DNAs from A. parasiticus NIAH-26 and A. oryzae SYS-2 were subjected to Southern analysis (Fig. 3). Although dmtA of A. parasiticus contains four HindIII restriction sites (Fig. 2), only the largest fragment after digestion with HindIII (positions −301 to 1418) contained the sequence (positions −108 to 1257) of the DIG-labeled 1,365-bp dmtA PCR fragment. Southern analysis clearly showed that the DIG-labeled probe hybridized to a DNA fragment of the predicted size (1,860 bp). Also, a single fragment (length, about 6 kb) was obtained after digestion with EcoRI. These results indicate that dmtA is a single-copy gene in the genome. Similarly, a single fragment of A. oryzae DNA hybridized to the probe after digestion with either HindIII or EcoRI, indicating that this fungus also contains a single copy of a dmtA homolog, whereas A. oryzae SYS-2 appears to have lost some HindIII sites, because a larger DNA fragment (length, about 3 kb) hybridized to the probe.

FIG. 3.

Southern analysis of the dmtA gene. Genomic DNAs of A. parasiticus NIAH-26 (lanes 1 and 3) and A. oryzae SYS-2 (lanes 2 and 4) were digested with HindIII (lanes 1 and 2) or EcoRI (lanes 3 and 4) and probed with a 1,365-bp PCR fragment corresponding to positions −108 to 1257. The positions of size markers are indicated on the left.

In order to examine the sequence similarity of the homologs of A. parasiticus and A. oryzae in more detail, we also performed PCR analyses with the following three combinations of primers: primers mt-I 2R and mt-I 2F, primers mt-I 2F and mt-I 3R, and primers mt-I 3F and mt-I 2R. With all combinations of primers, the same predicted sizes of PCR products were obtained when the DNA of either fungus was used as the template (data not shown). These results indicate that A. oryzae SYS-2 also contains a dmtA homolog.

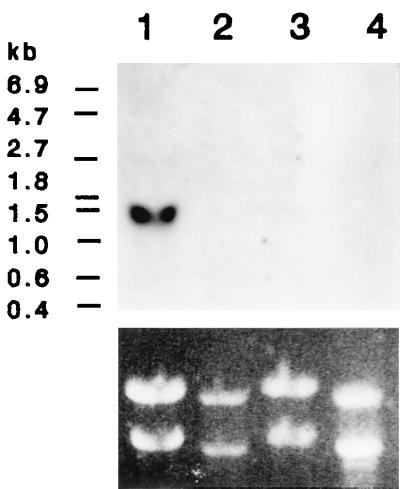

Expression of the dmtA gene.

Transcription of dmtA gene was determined by Northern blotting. When A. parasiticus NIAH-26 was cultured at 28°C for 3 days in aflatoxin-inducing SY medium, a 1.4-kb transcript of dmtA was observed (Fig. 4). In contrast, when non-aflatoxin-inducing PY medium was used instead of SY medium, dmtA was not expressed. Also, when the fungi were cultured at a higher temperature (37°C, a non-aflatoxin-permissive temperature) (7), expression of dmtA was not detected, irrespective of the medium. On the other hand, a reverse transcriptase PCR analysis showed that the amounts of dmtA transcript were almost the same after 2 and 3 days when SY medium was used (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Northern analysis of dmtA expression. The PCR product corresponding to primer mt-I 2F to primer mt-I 2R (1,365 bp) was used as a probe to detect the dmtA transcript. Total RNAs were prepared from A. parasiticus NIAH-26 cultured in either SY medium (lanes 1 and 3) or PY medium (lanes 2 and 4) at 28°C (lanes 1 and 2) or 37°C (lanes 3 and 4) for 3 days. The bottom part of the figure shows rRNA bands in the ethidium bromide-stained gel used to prepare the blot.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we determined the cDNA and genomic DNA sequences encoding MT-I in A. parasiticus. This gene is present as a single-copy gene in the genome and is located between the omtA and ord-2 genes in the aflatoxin biosynthesis gene cluster. The open reading frame encodes a 386-amino-acid enzyme and is interrupted by three introns, and expression of the open reading frame is regulated by the culture conditions.

Difference in the deduced amino acid sequences of dmtA and omtA.

The omtA gene product is another O-methyltransferase that is involved in aflatoxin biosynthesis and catalyzes the conversion of sterigmatocystin to O-methylsterigmatocystin and the conversion of dihydrosterigmatocystin to dihydro-O-methylsterigmatocystin (Fig. 1) (37). As determined by a GCG homology search, the deduced amino acid sequence encoded by the dmtA gene exhibited 28.2% identity and 50% similarity to the sequence encoded by omtA. The C-terminal half of the dmtA gene product exhibited 32.8% identity to the same region of the omtA product of A. parasiticus, and these regions contain an S-adenosylmethionine binding consensus sequence (10), indicating that this part of the protein may contain a common functional domain for methylation in many methyltransferases. In contrast, the N-terminal halves exhibited only 22.7% identity, and the numbers and sites of the introns of the two genes were different; the omtA gene contains four introns (38).

We have reported previously that MT-I exhibits substrate inhibition (34), whereas MT-II does not exhibit this kind of inhibition (29a). These results may indicate that the functional domain related to substrate inhibition is in the N-terminal half of the protein. We have also reported that N-ethylmaleimide treatment of MT-I results in inhibition of enzyme activity, whereas it does not affect MT-II activity (33). The deduced amino acid sequence of the MT-I protein contains three cysteine residues at positions 143, 165, and 300. Although a cysteine residue corresponding to the last cysteine residue at position 300 was also found in omtA gene products, the other two cysteines were not found in omtA in the GCG Bestfit analysis. These results suggest that either or both of the cysteines at positions 143 and 165 may be involved in the enzyme activity.

Comparison of dmtA and A. nidulans stcP and the deduced amino acid sequences.

Kelkar et al. (12) found by using a gene disruption strategy that an open reading frame from position 42597 to position 41970 (accession no. ENU34740) of the A. nidulans stcP gene encodes MT-I. Since the dmtA gene of A. parasiticus is supposed to be a homolog of the stcP gene, the deduced amino acid sequences of the two genes were compared (Fig. 5). The dmtA gene product exhibited 74.4% identity and 87% similarity with the deduced gene product encoded by a nucleotide sequence in the 1,289-bp region (positions 43273 to 41985). The N-terminal half of the dmtA product exhibited 73% identity with the amino acid sequence encoded by the 5′ flanking region of the stcP gene, whereas the C-terminal half exhibited 76.3% identity with the stcP product. This whole region of stcP may encode a protein composed of 424 amino acids, whose theoretical molecular mass is 47,840 Da.

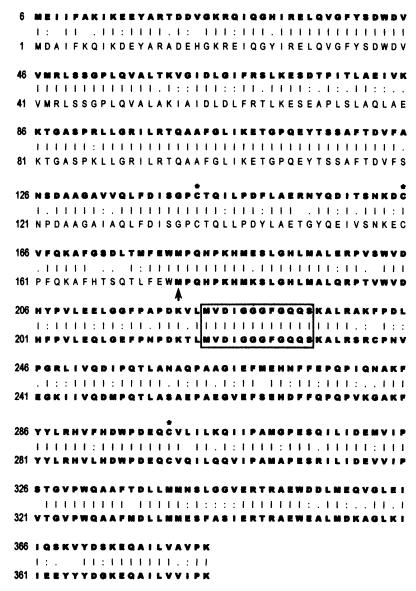

FIG. 5.

Comparison of the deduced amino acid sequence of MT-I with the A. nidulans StcP sequence, which is encoded by stcP and its 5′ flanking region. The translation initiation site which Kelkar et al. suggested (12) is indicated by an arrow. The predicted StcP sequence (12) and MT-I are shown in boldface type. The cysteinyl residues of MT-I are indicated by asterisks.

Recently, sequence data for A. nidulans 24-h asexual cDNA clones have been reported in the DataBank database, and the deduced amino acid sequences encoded by some of the clones are consistent with the sequence of part of the stcP gene product (DataBank clones AA783469, AI209606, AI212908, AI212909, AA785366, AI210056, and AA783468). In particular, clones AA783469 and AI209606 encode regions corresponding to positions +1 to 58 and 133 to 282 of the whole StcP protein. These data strongly indicate that the 5′ flanking region of the stcP gene is in fact expressed as part of the whole stcP gene transcript. A comparison of the genomic and cDNA nucleotide sequences of dmtA with the sequences of whole stcP revealed that the coding regions of dmtA and stcP are especially conserved in the different fungi compared to the intron regions.

Involvement of the dmtA gene in the aflatoxin gene cluster.

Gene walking performed with TAIL-PCR technology revealed that the dmtA gene is located between the omtA gene and the ord-2 gene in the same direction. The region between omtA and dmtA contains the TATA sites and the AflR recognition site (8), indicating that expression of dmtA is also regulated by the aflR gene product, which has been found to regulate other enzyme genes involved in aflatoxin biosynthesis (4, 9, 20, 23, 28). This was confirmed by results showing that expression of dmtA has the same dependency on the culture temperature and the culture medium (Fig. 4); such expression patterns have been found commonly in the genes involved in the cluster (7).

The stcP gene is located between the stcQ and stcO genes in the sterigmatocystin biosynthesis cluster (3, 14), and the directions of transcription of these three genes are the same, which is similar to the relationship among omtA, dmtA, and ord-2. However, stcQ and stcO commonly exhibit 31.0 and 51.8% identity, respectively, to ord-2 of A. parasiticus. Also, the distance from the termination codon of stcQ to the translation start site of the whole stcP gene is only 169 bp, which is much shorter than the distance between omtA and dmtA sites (1,317 bp). In contrast, the distance between the stcP and stcO sites (139 bp) is similar to the distance between the dmtA and ord-2 sites. These data support the suggestion (14, 29) that the distribution pattern of the genes in gene clusters is unique to each cluster.

The distance between the transcription termination site of the dmtA gene and the transcription start site of the ord-2 gene was very short, only 34 bp, as described above. There is no typical TATA motif or AflR recognition sequence in this region or in the internal region of dmtA (from position 716 to position 1683). However, using reverse transcriptase PCR analysis, we found that expression of ord-2 is affected by the culture conditions, like expression of other genes containing dmtA involved in the aflatoxin biosynthesis gene cluster (data not shown). Therefore, the promoter structure of ord-2 and regulation of its expression remain to be studied.

Presence of dmtA gene homologs in both A. parasiticus and A. oryzae.

We have reported previously that the enzyme activities of MT-I, as well as other enzymes involved in aflatoxin biosynthesis, could not be detected in cell extracts of nonaflatoxigenic A. oryzae SYS-2 that had been cultured in aflatoxin-inducible YES medium (30, 32, 33, 36). In the present study, we showed that A. oryzae SYS-2 also has a single copy of a dmtA gene homolog (Fig. 3). Recently, Watson et al. (27) reported that sequences homologous to nor-1, ver-1, omtA, and aflR are also present in strains of A. oryzae and Aspergillus sojae, although no transcripts of these homologs have been found in any of the strains examined. Similar results have been reported by other researchers (15–18). It has been suggested that the nonaflatoxigenic phenotype is caused by a regulatory malfunction. We are now investigating the mechanism of regulation of expression of this gene.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank S. Mori for her technical advice concerning amino acid sequencing, S. Suzuki for her technical advice concerning RACE-PCR, and K. Yamagishi, Tohoku National Agricultural Experiment Station, for his advice concerning TAIL-PCR and the supply of random primers. We also thank Y. Ando, National Institute of Animal Health, for taking photographs.

This work was supported in part by grant-in-aid BDP-99-V-1-4 (Bio-Design Program) from the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bhatnagar D, Erlich K C, Cleveland T E. Oxidation-reduction reactions in biosynthesis of secondary metabolites. In: Bhatnagar D, Lillehoj E B, Arora D K, editors. Handbook of applied mycology. Vol. 5. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 1992. pp. 255–286. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhatnagar D, Ullah A H J, Cleveland T E. Purification and characterization of a methyltransferase from Aspergillus parasiticus SRRC 163 involved in aflatoxin biosynthesis pathway. Prep Biochem. 1988;18:321–349. doi: 10.1080/00327488808062532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown D W, Yu J-H, Kelkar H S, Fernandes M, Nesbitt T C, Keller N P, Adams T H, Leonard T J. Twenty-five coregulated transcripts define a sterigmatocystin gene cluster in Aspergillus nidulans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:1418–1422. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang P-K, Cary J W, Bhatnagar D, Cleveland T E, Bennett J W, Linz J E, Woloshuk C P, Payne G A. Cloning of the Aspergillus parasiticus apa-2 gene associated with the regulation of aflatoxin biosynthesis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:3273–3279. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.10.3273-3279.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dutton M F. Enzymes and aflatoxin biosynthesis. Microbiol Rev. 1988;52:274–295. doi: 10.1128/mr.52.2.274-295.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dvorackova I. Aflatoxins and human health. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feng G H, Leonard T J. Culture conditions control expression of the genes for aflatoxin and sterigmatocystin biosynthesis in Aspergillus parasiticus and A. nidulans. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:2275–2277. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.6.2275-2277.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernandes M, Keller N P, Adams T H. Sequence-specific binding by Aspergillus nidulans AflR, a C6 zinc cluster protein regulating mycotoxin biosynthesis. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:1355–1365. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flaherty J E, Payne G A. Overexpression of aflR leads to upregulation of pathway gene transcription and increased aflatoxin production in Aspergillus flavus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3995–4000. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.10.3995-4000.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haydock S F, Dowson J A, Dhillon N, Roberts G A, Cortes J, Leadlay P F. Cloning and sequence analysis of genes involved in erythromycin biosynthesis in Saccharopolyspora erythraea: sequence similarities between EryG and a family of S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferases. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;230:120–128. doi: 10.1007/BF00290659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kagan R M, Clarke S. Widespread occurrence of three sequence motifs in diverse S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferases suggests a common structure for these enzymes. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1994;310:417–427. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1994.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelkar H S, Keller N P, Adams T H. Aspergillus nidulans stcP encodes an O-methyltransferase that is required for sterigmatocystin biosynthesis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:4296–4298. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.11.4296-4298.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keller N P, Dischinger H C, Jr, Bhatnagar D, Cleveland T E, Ullah A H J. Purification of a 40-kilodalton methyltransferase active in the aflatoxin biosynthetic pathway. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:479–484. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.2.479-484.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keller N P, Hohn T M. Metabolic pathway gene clusters in filamentous fungi. Fungal Genet Biol. 1997;21:17–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klich M A, Yu J, Chang P-K, Mullaney E J, Bhatnagar D, Cleveland T E. Hybridization of genes involved in aflatoxin biosynthesis to DNA of aflatoxigenic and non-aflatoxigenic aspergilli. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1995;44:439–443. doi: 10.1007/BF00169941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klich M A, Montalbano B, Ehrlich K. Northern analysis of aflatoxin biosynthesis genes in Aspergillus parasiticus and Aspergillus sojae. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1997;47:246–249. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kusumoto K-I, Mori K, Nogata Y, Ohta H, Manabe M. Homologs of the aflatoxin biosynthetic gene ver-1 in strains of Aspergillus oryzae and related species. J Ferment Bioeng. 1996;82:161–164. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kusumoto K-I, Yabe K, Nogata Y, Ohta H. Aspergillus oryzae with and without a homolog of aflatoxin biosynthetic gene ver-1. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1998;50:98–104. doi: 10.1007/s002530051262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu B-H, Chu F S. Regulation of aflR and its product, AflR, associated with aflatoxin biosynthesis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:3718–3723. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.10.3718-3723.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Y-G, Whittier R F. Thermal asymmetric interlaced PCR: automatable amplification and sequencing of insert end fragments from P1 and YAC clones for chromosome walking. Genomics. 1995;25:674–681. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(95)80010-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Minto R E, Townsend C A. Enzymology and molecular biology of aflatoxin biosynthesis. Chem Rev. 1997;97:2537–2555. doi: 10.1021/cr960032y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Payne G A, Nystrom G J, Bhatnagar D, Cleveland T E, Woloshuk C P. Cloning of the afl-2 gene involved in aflatoxin biosynthesis from Aspergillus flavus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:156–162. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.1.156-162.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trail F, Mahanti N, Linz J. Molecular biology of aflatoxin biosynthesis. Microbiology. 1995;141:755–765. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-4-755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ullrich R C, Kohorn B D, Specht C A. Absence of short-period repetitive-sequence interspersion in the basidiomycete Schizophyllum commune. Chromosoma (Berlin) 1980;81:371–378. doi: 10.1007/BF00368149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Watson A J, Fuller L J, Jeenes D J, Archer D B. Homologs of aflatoxin biosynthesis genes and sequence of aflR in Aspergillus oryzae and Aspergillus sojae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:307–310. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.1.307-310.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Woloshuk C P, Foutz K R, Brewer J F, Bhatnagar D, Cleveland T E, Payne G A. Molecular characterization of aflR, a regulatory locus for aflatoxin biosynthesis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:2408–2414. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.7.2408-2414.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woloshuk C P, Prieto R. Genetic organization and function of the aflatoxin B1 biosynthetic genes. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;160:169–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb12907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29a.Yabe, K. Unpublished data.

- 30.Yabe K, Ando Y, Hamasaki T. Biosynthetic relationship among aflatoxins B1, B2, G1, and G2. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:2101–2106. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.8.2101-2106.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yabe K, Ando Y, Hamasaki T. A metabolic grid among versiconal hemiacetal acetate, versiconol acetate, versiconol and versiconal during aflatoxin biosynthesis. J Gen Microbiol. 1991;137:2469–2475. doi: 10.1099/00221287-137-10-2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yabe K, Ando Y, Hamasaki T. Desaturase activity in the branching step between aflatoxins B1 and G1 and aflatoxins B2 and G2. Agric Biol Chem. 1991;55:1907–1911. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yabe K, Ando Y, Hashimoto J, Hamasaki T. Two distinct O-methyltransferases in aflatoxin biosynthesis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:2172–2177. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.9.2172-2177.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yabe K, Matsushima K-I, Koyama T, Hamasaki T. Purification and characterization of O-methyltransferase I involved in conversion of demethylsterigmatocystin to sterigmatocystin and of dihydrodemethylsterigmatocystin to dihydrosterigmatocystin during aflatoxin biosynthesis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:166–171. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.1.166-171.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yabe K, Nakamura H, Ando Y, Terakado N, Nakajima H, Hamasaki T. Isolation and characterization of Aspergillus parasiticus mutants with impaired aflatoxin production by a novel tip culture method. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:2096–2100. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.8.2096-2100.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yabe K, Nakamura Y, Nakajima H, Ando Y, Hamasaki T. Enzymatic conversion of norsolorinic acid to averufin in aflatoxin biosynthesis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:1340–1345. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.5.1340-1345.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu J, Cary J W, Bhatnagar D, Cleveland T E, Keller N P, Chu F S. Cloning and characterization of a cDNA from Aspergillus parasiticus encoding an O-methyltransferase involved in aflatoxin biosynthesis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:3564–3571. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.11.3564-3571.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yu J, Chang P-K, Payne G A, Cary J W, Bhatnagar D, Cleveland T E. Comparison of the omtA genes encoding O-methyltransferases involved in aflatoxin biosynthesis from Aspergillus parasiticus and A. flavus. Gene. 1995;163:121–125. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00397-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu J, Chang P-K, Cary J W, Wright M, Bhatnagar D, Cleveland T E, Payne G A, Linz J E. Comparative mapping of aflatoxin pathway gene clusters in Aspergillus parasiticus and Aspergillus flavus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2365–2371. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.6.2365-2371.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]