Abstract

American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) persons bear a disproportionate burden of human papillomavirus (HPV)-associated cancers and face unique challenges to HPV vaccination. We undertook a systematic review to synthesize the available evidence on HPV vaccination barriers and factors among AI/AN persons in the United States. We searched fourteen bibliographic databases, four citation indexes, and six gray literature sources from July 2006 to January 2021. We did not restrict our search by study design, setting, or publication type. Two reviewers independently screened the titles and abstracts (stage 1) and full-text (stage 2) of studies for selection. Both reviewers then independently extracted data using a data extraction form and undertook quality appraisal and bias assessment using the modified Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool. We conducted thematic synthesis to generate descriptive themes. We included a total of 15 records after identifying 3017, screening 1415, retrieving 203, and assessing 41 records. A total of 21 unique barriers to HPV vaccination were reported across 15 themes at the individual (n=12) and clinic or provider (n=3) levels. At the individual level, the most common barriers to vaccination--safety and lack of knowledge about the HPV vaccine--were each reported in the highest number of studies (n=9; 60%). The findings from this review signal the need to develop interventions that target AI/AN populations to increase the adoption and coverage of HPV vaccination. Failure to do so may widen disparities.

INTRODUCTION

Human papillomavirus (HPV), the most common sexually transmitted infection,1 causes certain cancers collectively known as HPV-associated cancers. In the United States (US), over 45,000 new cases of HPV-associated cancer cases occur annually.2 The burden of HPV-associated cancers is disproportionately higher among American Indians and Alaska Natives (AI/AN). From 2013 to 2017, the incidence rate (per 100,000) for all HPV-associated cancers was significantly higher among AI/AN women (15.9) than non-Hispanic White women (13.7), highlighting the disparity in disease burden.3

Vaccines to prevent HPV-associated cancers have been available since 2006 for girls and since 2009 for boys in the US. However, in 2019, only 71.1% of AI/AN adolescents aged 13 to 17 years had initiated, and 57.5% were up to date with HPV vaccination nationally.4 Previous systematic reviews have identified several factors and barriers associated with HPV vaccination.5–11 However, some factors, such as insurance coverage,8,12,13 and barriers, such as the cost of the HPV vaccine,5–7 may not apply to the AI/AN context. In addition, reviews have centered on specific racial and ethnic groups, including African Americans and Latinos.14,15 However, no review on HPV vaccination barriers and factors has focused on the AI/AN population. Even reviews that have assessed racial factors and disparities in vaccination did not include AI/AN persons.16–18 Furthermore, data on HPV vaccination factors for AI/AN persons are combined with other racial groups in the analysis of national surveys,19–22 making it challenging to discern vaccination factors unique to AI/AN communities.

In the absence of a review focused on the AI/AN population and given the elevated burden of HPV-associated cancers and unique challenges AI/AN communities face, we undertook this review to synthesize the available evidence on HPV vaccination barriers and factors. The objective of this systematic review was to identify and assess factors that (i) are barriers to HPV vaccination, (ii) support or enhance HPV vaccination, and (iii) are found not to be associated with HPV vaccination among AI/AN persons in the US.

METHODS

We developed and published the protocol for this systematic review using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for Protocols 2015 (PRISMA-P 2015).23,24 The systematic review is registered in PROSPERO (CRD42020156865). We also adhered to the PRISMA 2020 guidelines and report our review according to their recommendations (see Supplementary File A).25

Eligibility criteria.

We included studies published in English that assessed HPV vaccination barriers and factors among AI/AN persons in the US, except territories, covering the period from July 1, 2006 to January 05, 2021. We did not restrict by study design (except existing reviews), setting, or publication type.

Information sources.

We followed and reported the information sources, search strategy, and record management using PRISMA-S guidelines.26 To minimize the risk of bias and maximize the inclusion of relevant studies, we searched fourteen bibliographic databases, four citation indexes, and six gray literature sources. A list of sources searched is presented in Table 1. We also undertook complementary searching activities, including citation chaining and searching.

TABLE 1.

Sources searched for systematic review of human papillomavirus vaccination barriers or factors, July 2006-January 2021.

| Name | Interface/Platform | Search executed (# of records*) | Total # of records* |

|---|---|---|---|

| MEDLINE and Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations | Ovid | July 8, 2019 (n = 364) Search updated: October 3, 2019 (n = 34) December 16, 2020 (n = 82) |

480 |

| PubMed | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/ | July 22, 2019 (n = 428) Search updated: October 3, 2019 (n = 18) December 16, 2020 (n = 43) |

489 |

| Embase | Ovid | July 8, 2019 (n = 348) Search updated: October 3, 2019 (n = 9) December 16, 2020 (n = 95) |

452 |

| Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) | Ovid | October 4, 2019 (n = 7) Search updated: December 16, 2020 (n = 2) |

9 |

| CINAHL Complete | EBSCO | July 22, 2019 (n = 31) Search updated: December 16, 2020 (n = 9) |

40 |

| ERIC | Ovid | July 22, 2019 (n = 87) Search updated: December 16, 2020 (n = 19) |

106 |

| PsycINFO | Ovid | July 8, 2019 (n = 154) Search updated: December 16, 2020 (n = 31) |

185 |

| SocINDEX | EBSCO | July 22, 2019 (n = 34) Search updated: December 16, 2020 (n = 52) |

86 |

| Bibliography of Native North Americans | EBSCO | July 22, 2019 (n = 6) Search updated: December 16, 2020 (n = 0) |

6 |

| Social Work Abstracts | EBSCO | July 22, 2019 (n = 11) Search updated: December 16, 2020 (n = 11) |

22 |

| Native Health Database | https://hslic-nhd.health.unm.edu/ | December 22, 2019 (n = 0) Search updated: January 5, 2021 (n = 0) |

0 |

| Indigenous Studies Portal (iPortal) | https://iportal.usask.ca/ | December 23, 2019 (n = 3) Search updated: January 5, 2021 (n = 0) |

3 |

| Arctic Health Publications Database | https://arctichealth.org/ | December 23, 2019 (n = 1) Search updated: January 5, 2021 (n = 0) |

1 |

| Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI-Expanded) | Web of Science | July 8, 2019 (n = 313) Search updated: December 16, 2020 (n = 116) |

429 |

| Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) | Web of Science | ||

| Arts & Humanities Citation Index (A&HCI) | Web of Science | ||

| Emerging Sources Citation Index | Web of Science | ||

| Scopus | https://www.scopus.com/home.uri | July 22, 2019 (n = 56) Search updated: December 16, 2020 (n = 285) |

341 |

| Dissertations and Theses | ProQuest | October 4, 2019 (n = 212) Search updated: December 17, 2020 (n = 41) |

253 |

| Northern Light Life Sciences Conference Abstracts | Ovid | July 22, 2019 (n = 65) Search updated: December 16, 2020 (n = 15) |

80 |

| PapersFirst | FirstSearch | October 4, 2019 (n = 1) Search updated: December 17, 2020 (n = 0) |

1 |

| Proceedings | FirstSearch | October 4, 2019 (n = 33) Search updated: December 17, 2020 (n = 0) |

33 |

| OSF Preprints | https://osf.io/preprints/ | December 24, 2020 (n = 0) Search updated: January 5, 2021 (n = 0) |

0 |

| Tribal Epidemiology Centers | https://tribalepicenters.org/12-tecs/ | January 5, 2020 (n = 1) Search updated: January 5, 2021 (n = 0) |

1 |

Abbreviations:

CINAHL, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health; ERIC, Education Resources Information Center.

Notes:

Number of records prior to screening. May include duplicate records.

Search strategy.

We selected the information sources and developed the search strategy in consultation with an experienced health sciences librarian. We used controlled vocabulary terms and keywords, such as synonyms and trade names, to capture key concepts. To strike a balance between comprehensiveness and precision, we used truncation and proximity searching to ensure comprehensiveness, and set appropriate limits and removed duplicates to achieve precision. We piloted the search strategy in three Ovid databases (MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO), and Web of Science Core Collection’s Social Sciences Citation Index, Science Citation Index-Expanded, Arts & Humanities Citation Index, and Emerging Sources Citation Index. We refined the search terms, if needed. The refined search strategy for all sources with interface and coverage has been published previously.24 We also updated our search to include newer literature from December 2020 to January 2021.

Selection process.

We screened and selected studies in two stages. In stage 1, two reviewers used the following keywords to screen titles and abstracts: HPV vaccine or vaccination, American Indian, Alaska Native, Native American, race or racial. In stage 2, we developed, piloted, and revised a screening and selection form to screen the full-text of records included in stage 1. The two reviewers resolved discrepancies through discussions and consulted a third reviewer to aid decision-making and achieve resolution when needed.

Data collection process and data items.

We developed and piloted a data extraction form by adapting questions from the Cochrane Collaboration’s intervention reviews for RCTs and non-RCTs,27 Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guideline for quantitative studies,28 and Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) guideline.29 The data extraction form and the included data items are provided in a previous publication.24

Quality appraisal and bias assessment.

We used a modified Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) (version 2018) to assess the methodological quality of included studies.30 We selected the tool because it covers different study designs, has improved content validity, and has high inter-rater reliability.30 We added five questions to the MMAT and expanded the scope to include methodological and reporting criteria. The first three questions (Are the data collection and analysis methods appropriate? Are the limitations of the study adequately described? Are there any ethical concerns or conflict of interest?) are a requirement of several reporting guidelines.28,29,31 The remaining two questions were adapted from the CONSIDER statement to assess whether AI/AN stakeholders were involved in the research process and whether a culturally appropriate methodology was used.32 Similar to screening and selecting studies, the two reviewers undertook independent quality and bias assessment, with disagreements being resolved through discussion and in consultation with the third reviewer when needed.

Data synthesis.

We did not undertake a meta-analysis due to the unavailability of individual data and heterogeneity in study designs and measures. However, we assessed HPV vaccination barriers and factors at the individual and clinic or provider levels. When available, we reported measures of frequency and association.

For thematic synthesis, we reviewed each study included in our final review and extracted data about barriers and factors related to and unrelated to HPV vaccination. Two reviewers verified the extracted data and resolved any discrepancies. In addition, the reviewers assessed similarities and differences and organized and grouped the data into related areas to construct descriptive themes.

RESULTS

Study selection.

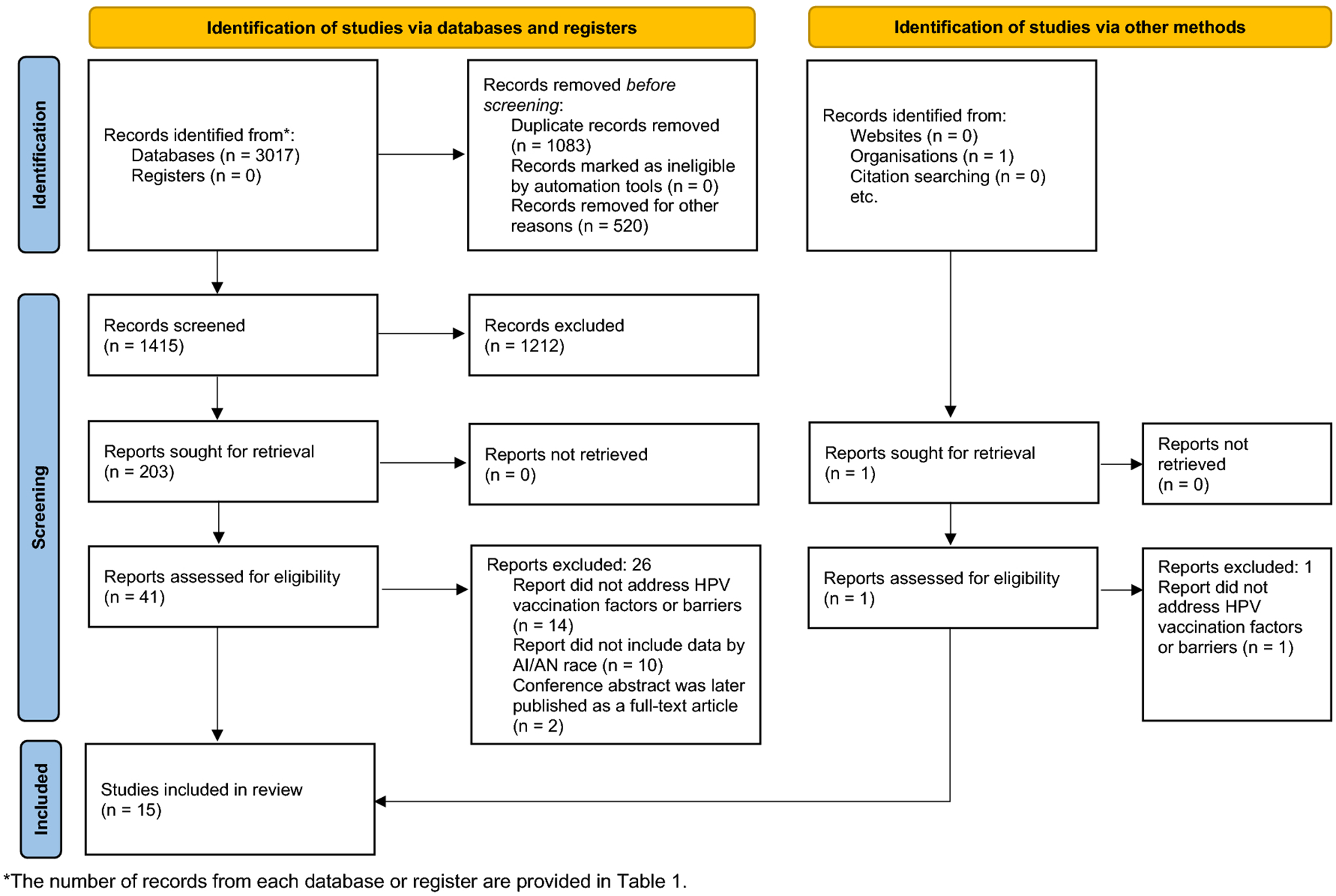

From July 2006 to January 2021, we identified 3,017 records from databases and citation indexes and one record from the gray literature. After removing duplicate, non-English, and non-US records, we screened 1,415, retrieved 203, and assessed 41 records. For the final review, we included a total of 15 records33–47 after excluding records that did not address HPV vaccination barriers or factors (n=14) or did not include data by AI/AN race (n=10), and excluding conference abstracts if they were later published as full-text articles (n=2). Figure 1 shows a PRISMA 2020 flow diagram with the results of the search and selection process.

Figure 1:

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram.

Study characteristics.

Key characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 2. Of the 15 studies, nine assessed HPV vaccination barriers or factors at the individual level,33–41 five studies assessed barriers at the clinic or provider level,42–46 and one study included both levels.47 Four studies used quantitative research methodology,34,35,42,43 four used qualitative methodology,33,36,38,40 six used both qualitative and quantitative approaches,37,39,44–47 and one was a cluster-randomized trial.41 Most studies were published as full-text articles (n=12), but our final review also included one dissertation,34 one presentation,40 and one abstract.42 Two studies focused on AN adolescents38 and parents39 and one study included provider surveys and interviews from IHS in Alaska.45

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of included studies (n=15).

| HPV vaccination | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author (year) | Publication Type | Study Period | State or Location | Method | Size (% female) | Population | Barriers | Factors |

| Individual-level | ||||||||

| Bowen (2014)33 | Article | 2009–2010 | CT, MA, ME, NH, RI, VT | Qualitative (focus group) | 50 (100%) | Parents | Yes | Yes |

| Bowker (2017)34 | Dissertation | 2017 | SD | Quantitative (survey) | 89 (100%) | Young adults (18–25 years) |

Yes | Yes |

| Buchwald (2013)35 | Article | 2007–2009 | SD | Quantitative (survey) | 351 (100%) | Adults (18–65 years) |

Yes | Yes |

| Hodge (2014)36 | Article | 2009 | AZ & CA | Qualitative (focus group) | 53 (60.4%) | College students (18–26 years) |

No | Yes |

| Hodge (2011)37 | Article | 2009 | AZ & CA | Quantitative (survey) & Qualitative (focus group) | 57 (59.6%) | College students (18–26 years) |

No | Yes |

| Kemberling (2011)38 | Article | 2008 | AK | Qualitative (interviews) | 79 (100%) | Adolescents (11–18 years) |

Yes | Yes |

| Toffolon-Weiss (2008)39 | Article | 2007 | AK | Quantitative (survey) & Qualitative (focus group) | 80 (>80%) | Parents | Yes | Yes |

| White (2018)40 | Presentation | –* | WA | Qualitative (focus group) | 9 (–*) | Parents & Young adults (18–26 years) |

Yes | Yes |

| Winer (2016)41 | Article | 2007–2013 | AZ | Cluster-randomized trial | 97 (100%) | Parents & Adolescents (9–12 years) |

Yes | Yes |

| Clinic- or Provider-level | ||||||||

| Bruegl (2016)42 | Abstract | –* | –* | Quantitative (survey) | 60 (–*) | Physicians | Yes | Yes |

| Duvall (2012)43 | Article | 2009–2010 | WA | Quantitative (survey) | 31 IHS or tribal clinics (–*) | –* | No | Yes |

| Jacobs-Wingo (2017)44 | Article | 2013–2015 | 5 IHS regions | Quantitative (survey) & Intervention study | 19 I/T/U facilities (–*) | –* | Yes | Yes |

| Jim (2012)45 | Article | 2009–2010 | 12 IHS areas | Quantitative (survey) & Qualitative (semi-structured interview) | Survey: 268 (74.6%) Interview: 51 (78.4%) |

Healthcare provider | No | Yes |

| Kashani (2019)46 | Article | 2006–2015 | MI | Qualitative (semi-structured interview) & Secondary data analysis | Interview: 14 (–*) Data: 684,509 adolescents (49.9%) |

Providers and public health professionals | Yes | Yes |

| Both | ||||||||

| Schmidt-Grimminger (2013)47 | Article | 2009 | SD | Quantitative (survey) & Qualitative (focus group) | 73 (–*) | Tribal and IHS health providers, young adults (19–26 years), adolescents (14–18 years), and parents. | No | Yes |

Notes:

Data not specified or not applicable.

Abbreviations: IHS, Indian Health Service; I/T/U, Indian Health Service, tribally-operated, and urban Indian healthcare facilities.

U.S. State: AK, Alaska; AZ, Arizona; CA, California; CT, Connecticut; MA, Massachusetts; ME, Maine; MI, Michigan; NH, New Hampshire; RI, Rhode Island; SD, South Dakota; VT, Vermont; WA, Washington.

Participant characteristics.

At the individual level, studies assessed HPV vaccination barriers or factors among AI/AN adolescents (n=2), young adults or college students (n=4), adults (n=1), and parents (n=3). Most participants at the individual level were female. The proportion of females was 100% in five studies,33–35,38,41 >80% in one study,39 and approximately 60% in two studies.36,37 One study did not specify the sex of the participants.48 At the clinic or provider level, five studies assessed factors or barriers among healthcare providers, public health professionals, and staff from the Indian Health Service (IHS), Tribal and Urban Indian (I/T/U) facilities.42–46

Quality assessment.

We have included a summary table of the quality and risk of bias assessment for each study according to the modified MMAT in Supplementary File B. All qualitative studies, except one,45 met every methodological quality criterion of MMAT. Conversely, the methodological quality for quantitative studies varied. For example, only two studies (22.2%) adequately addressed the risk of nonresponse bias,34,43 and two studies (22.2%) clearly described the target population and sample.34,44

Across all studies, information addressing the additional questions on the modified MMAT was not uniformly reported. We could not ascertain information about conflicts of interest for nine studies,33,34,36–40,42,47 indicating the need for authors and journals to be more transparent. In addition, nine studies did not specify whether and how they considered the physical, social, economic, and cultural environment of the AI/AN stakeholders and participants,33,35–37,40,42,43,45,46 making it challenging to evaluate the context and implications for AI/AN communities.

Barriers associated with HPV vaccination.

We have summarized barriers and factors related to and unrelated to HPV vaccination in concise (Table 3) and detailed (Supplementary File C) tables.

TABLE 3.

Summary of barriers and factors associated with HPV vaccination among American Indians and Alaska Natives.

| HPV vaccination | Population | Themes (n)* | Key Findings | Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barriers | ||||

| Parents | ||||

| Safety (n=7) | Parents or caregivers expressed concerns about side effects and long-term safety. | Bowen (2014), Jacobs-Wingo (2017), Jim (2012), Kashani (2019), Schmidt-Grimminger (2013), Toffolon-Weiss (2008), Winer (2016) | ||

| Knowledge (n=6) | Parents or caregivers lacked awareness and knowledge of the HPV vaccine. They also expressed confusion and misconceptions about the HPV vaccine. | Bowen (2014), Bruegl (2016), Duvall (2012), Jacobs-Wingo (2017), Kashani (2019), Winer (2016) | ||

| Sexual activity (n=5) | Some parents or caregivers believed that the HPV vaccine increases sexual activity. Some parents refused the vaccine because they believed that their child was not sexually active, while some parents believed that their child was already sexually active. | Jacobs-Wingo (2017), Jim (2012), Schmidt-Grimminger (2013), White (2018), Winer (2016) | ||

| Mistrust (n=4) | Parents expressed mistrust of the HPV vaccine and the medical system. | Bowen (2014), Duvall (2012), Toffolon-Weiss (2008), White (2018) | ||

| Vaccine efficacy (n=2) | Parents expressed concerns about the efficacy of the HPV vaccine. | Bruegl (2016), Jim (2012) | ||

| Cost (n=1) | Physician perceived barriers to vaccination uptake included concerns about vaccine cost. | Bruegl (2016) | ||

| Clinic access issues (n=1) | One of the top five barriers to vaccination was clinic access issues. | Jacobs-Wingo (2017) | ||

| Moral or religious reasons (n=1) | 57% of providers from I/T/U facilities reported that parent opposition to the vaccine was for moral or religious reasons. | Jim (2012) | ||

| Young adults | ||||

| Knowledge (n=3) | College students and young adults showed a lack of knowledge about HPV and HPV vaccine. | Bowker (2017), Hodge (2014), Hodge (2011) | ||

| Cultural barriers (n=2) | Some college students explained that discussing HPV may be considered taboo culturally. | Hodge (2014), Hodge (2011) | ||

| Risk perception (n=2) | Some college students held poor personal risk perception, and getting vaccinated against HPV was not seen as important. | Hodge (2014), Hodge (2011) | ||

| Safety (n=1) | Female college students reported the fear of short- or long-term side effects. | Hodge (2011) | ||

| Funding (n=1) | Providers from I/T/U facilities reported funding to be the main barrier for young adults. | Jim (2012) | ||

| Access issues (n=1) | College students shared that not all American Indian persons have access to IHS clinics or providers due to distance or rural location. | Hodge (2011) | ||

| Adolescents | ||||

| Side effects (n=1) | Older Alaska Native teens were concerned about the vaccine side effects. | Kemberling (2011) | ||

| Vaccine efficacy (n=1) | Older Alaska Native teens cited doubts about vaccine efficacy. | Kemberling (2011) | ||

| Afraid of shots (n=1) | Younger Alaska Native teens reported that being afraid of shots was the reason for not wanting to be vaccinated. | Kemberling (2011) | ||

| Healthcare providers | ||||

| Provider recommendation (n=2) | Lack of provider recommendations were reported as important barriers to vaccination. | Kashani (2019), Schmidt-Grimminger (2013) | ||

| Resource constraints (n=1) | IHS providers reported lack of time and provider shortages as potential barriers. | Schmidt-Grimminger (2013) | ||

| Funding (n=1) | Some clinics cited an overall lack of funding as a barrier to administering the HPV vaccine. | Duvall (2012) | ||

| Factors | ||||

| Parents | ||||

| Provider trust (n=1) | Healthcare provider influence and trust (39%) was the most important factor for receiving the HPV vaccination. | White (2018) | ||

| HPV vaccine education (n=1) | Mothers who received an HPV vaccine education intervention were more likely to initiate HPV vaccination (adjusted RR: 2.6; 95% CI: 1.4, 4.9) compared with the control group. | Winer (2016) | ||

| HPV knowledge (n=1) | Parents’ level of HPV knowledge was associated with willingness to vaccinate their child against HPV (OR: 1.2–1.5; p<.00–.05). | Buchwald (2013) | ||

| Young adults | ||||

| Provider trust (n=1) | Healthcare provider influence and trust (36%) was the most important factor for receiving the HPV vaccination. | White (2018) | ||

| Cultural practices (n=1) | Lakota women aged 18–25 who participated in the Hunkapi (Making of Relative) were two and a half times more likely to receive the HPV vaccine (OR: 2.58; 95% Cl: 1.07, 6.62). | Bowker (2017) | ||

| Healthcare providers | ||||

| None | ||||

| Factors not found to be associated | ||||

| Young adults | ||||

| Ceremonial practices (n=1) | Some ceremonial practices among Lakota women aged 18–25 were not associated with HPV vaccination. | Bowker (2017) | ||

| Language (n=1) | Speaking or understanding the Lakota language was not associated with HPV vaccination. | Bowker (2017) |

Abbreviations:

AN, Alaska Native; AI, American Indian; HPV, human papillomavirus; IHS, Indian Health Service; I/T/U, IHS, Tribal and Urban Indian.

Notes:

Indicates number of studies.

Twenty-one unique barriers to HPV vaccination were reported across 15 themes at the individual (n=12) and clinic or provider (n=3) levels. The most common barriers to vaccination—safety concerns33,37–39,41,44–47 and lack of knowledge33,34,36,37,41–44,46 about the HPV vaccine—were each reported in the highest number of studies (n=9; 60%). In these studies, AI/AN parents, young adults, and adolescents expressed concerns about the side effects and long-term safety of the HPV vaccine. They also lacked knowledge about the HPV vaccine, including lack of awareness, confusion, and misconceptions about the vaccine. For example, in a survey of Lakota women aged 18 to 25 years, 42.7% of participants believed that the HPV vaccine is only available for women, and 21.3% thought it was only for women under 18.34 Among other commonly noted barriers, AI/AN parents expressed mistrust of the vaccine and medical system in four studies33,39,40,43 and believed that the HPV vaccine could encourage earlier or riskier sexual behavior in three studies.44,45,47

At the provider or clinic level, studies reported funding issues or resource constraints as barriers.43,47 In a survey of 31 tribal and IHS clinics, 39% cited an overall lack of funding as a barrier to administering the HPV vaccine.43 In another study, IHS providers reported lack of time and provider shortages as potential barriers for vaccine administration.47

Factors associated with HPV vaccination.

We identified four studies elucidating factors associated with HPV vaccination across four themes: HPV knowledge,35 HPV education,41 provider trust,40 and cultural practices.34 First, HPV knowledge is an essential factor for vaccination. In a survey of rural AI women in the Northern Plains, knowledge about HPV was associated with willingness to vaccinate their child, underscoring the influence of educational interventions to increase vaccination rates.35 Mothers who received educational presentations on HPV as a part of a cluster-randomized trial were more likely to initiate (adjusted RR: 2.6; 95% CI: 1.4, 4.9) and complete (adjusted RR: 4.0; 95% CI: 1.2, 13.1) HPV vaccination in their daughters.41 In addition, 39% of parents and 36% of young adults in a focus group cited healthcare provider influence and trust as the most important factor for receiving the HPV vaccine.40

Factors not associated with HPV vaccination.

Among Lakota women aged 18 to 25 years, participating in ceremonial practices, such as Hunkapi (making of relative), increased the likelihood of HPV vaccination (odds ratio [OR]: 2.58; 95% Cl: 1.07, 6.62).34 However, other ceremonial practices, such as Inipi (rite of purification), Isnati (womanhood ceremony), and Wiwanyag Wachipi (Sundance), were not associated with HPV vaccination.34 In the same population, speaking or understanding the Lakota language was not associated with HPV vaccination.34

DISCUSSION

This systematic review provides an extensive synthesis of evidence to identify and summarize the barriers and factors to HPV vaccination at the individual and clinic level among AI/AN persons in the US. The results of this review revealed several barriers in this population, the most prominent of which were safety concerns, lack of knowledge about the vaccine, and medical and vaccine mistrust.

We found that concerns about safety and side effects are a major obstacle to HPV vaccination; this finding is consistent with systematic reviews in other populations.7,49–54 In previous reviews, adolescents,7,51,52 young adults,7,50 parents,49,53 and racial and ethnic minorities54 have shared safety concerns about the HPV vaccine, all of whom perceive it as an impediment to vaccination. Furthermore, in line with other systematic reviews,9,51–54 we found a lack of awareness and knowledge coupled with confusion and misconceptions about the HPV vaccine. HPV and HPV vaccine knowledge is associated with vaccination, as seen in one of the studies included in the review.35 In addition, an HPV educational presentation directed at Hopi mothers led to a higher HPV vaccine initiation and completion rate among their daughters.41 Therefore, to address the knowledge gaps and safety concerns, the development and dissemination of strong public health education campaigns tailored to the population are critical.

Another prominent reason for non-vaccination was medical and vaccine mistrust, which extended to drug companies, healthcare providers, and overall medical professionals in one study.33 Mistrust among AI/AN communities stems from multiple factors and has roots in historical events, including historical trauma and distrust.33,55 Therefore, it is critical for healthcare and public health systems and professionals to engage, address the long-standing historical and contemporary concerns, and establish trust with AI/AN communities.56 Building and maintaining trust will also translate into higher vaccination coverage, as seen in a study involving AI/AN parents of adolescent children, who reported that healthcare provider influence and trust was the most important factor for receiving the HPV vaccination for their children.40

Additionally, the cost of the HPV vaccine has been reported as a barrier in other systematic reviews.5,6 However, barring one study in our review,42 we did not find vaccination costs to be a barrier to HPV vaccination, primarily because the AI/AN persons can receive the HPV vaccine at no cost and are entitled to federally funded health care under treaties negotiated between Tribal Nations and the US government. HPV vaccines are often funded through the Vaccines for Children (VFC) program.

Limitations

Per PRISMA 2020 guidelines,25 limitations of this systematic review include limitations related to the included studies and the review process itself. The evidence from studies included in our review are subject to at least five limitations. First, based on the assessment using the modified MMAT, the quality of the studies included in our review was variable, highlighting methodological concerns. For example, most quantitative studies failed to adequately address the potential for selection bias and measurement error. Similarly, some qualitative studies did not use a theoretical framework or apply theory to inform the study design. Second, the reporting in some of the studies was inadequate, which limited our assessment. Specifically, some studies did not adequately describe study limitations, discuss ethical concerns, or describe how tribal communities were engaged as partners in the design and conduct of the research. Third, close to half of the studies included in our review were conducted before 2010, which may influence our results about vaccine knowledge, as these studies were completed only a few years after the vaccine’s introduction in 2006. As barriers or factors to HPV vaccination may evolve, we did not emphasize evidence found in newer studies compared with older studies. Fourth, although we did not assess for publication bias, only one study in our review reported factors that were not associated with HPV vaccination. Lastly, our research question did not allow us to differentiate between those who were hesitant and those who refused the HPV vaccine, as these differences may require different approaches and interventions.

Our review process also has some limitations that merit consideration. First, we excluded studies that included AI/AN populations, but did not provide data on barriers or factors by AI/AN status. Second, we could not report a pooled proportion of HPV vaccination among AI/AN adolescents due to missing coverage estimates and varying age groups and study participants. Third, information regarding our outcomes and key characteristics was unavailable for some studies; however, we did not contact the authors to obtain this information or seek further clarification. Lastly, and more importantly, we combine AI and AN persons into a single category of AI/AN in this review. In doing so, we are combining culturally and geographically distinct groups, which differ in traditions, languages, lifestyles, and laws. Aggregating AI and AN persons may mask important differences in HPV vaccination barriers and factors unique to each population, highlighting the value of examining these groups separately. The disaggregation of data in other U.S. populations, such as Asian American and Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander (NHPI) persons, has shown variation in cancer risk factors and outcomes.57 For example, when data on HPV vaccine initiation was disaggregated for Asian and NHPI women, it was found that adult Asian women aged 18 to 26 years reported a higher HPV vaccine initiation than adult NHPI women.58 Our review does not disaggregate AI groups from AN groups and fails to capture the diversity and heterogeneity between and within AI and AN communities. Therefore, our findings need to be interpreted in this context, thus limiting the generalizability of this review.

Conclusions

Identifying and understanding barriers and factors associated with HPV vaccination can increase vaccination coverage and ultimately reduce the incidence of HPV-associated cancers. Evidence from this review provides priority areas for improving HPV vaccination coverage in AI/AN persons, such as safety concerns and lack of vaccine knowledge. Our findings also signal the need for health systems, providers, and public health professionals to establish or strengthen trust with AI/AN communities. Additionally, and closely related, any intervention aimed at benefiting an AI/AN community must be sensitive to its culture and tradition to ensure engagement and adoption of HPV vaccination. Failure to do so may increase vaccine hesitancy and widen health disparities in this population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the guidance of Drs. Alicia Salvatore and Julie Stoner on the protocol for this systematic review. The authors appreciate the efforts of Kathy J. Kyler (Staff Editor, Office of the Vice President for Research, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center) in preparing this manuscript for publication.

Funding

SVG was supported by the Hudson Fellows in Public Health program through the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center. JEC and JDP were partially supported by the Oklahoma Shared Clinical and Translational Resources (U54GM104938) with an Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. JEC was partially supported by the National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support (Grant P30CA225520) awarded to the University of Oklahoma Stephenson Cancer Center for the use of the Biostatistics and Research Design Shared Resources.

The study sponsors did not have any role in study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing the report; and the decision to submit the report for publication.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Human Participant Protection

Human participant protection was not required for this study because it did not involve human participants.

Author Contributions (CRediT author statement)

Sameer Gopalani: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, data curation, writing – original draft.

Ami Sedani: Methodology, formal analysis, writing – original draft.

Amanda Janitz: Conceptualization, methodology, writing – review and editing.

Shari Clifton: Methodology, data curation, writing – review and editing.

Jennifer Peck: Supervision, writing – review and editing.

Ashley Comiford: Supervision, writing – review and editing.

Janis Campbell: Conceptualization, methodology, writing – review and editing, funding acquisition.

REFERENCES

- 1.Satterwhite CL, Torrone E, Meites E, et al. Sexually transmitted infections among US women and men: prevalence and incidence estimates, 2008. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40(3):187–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McQuillan G, Kruszon-Moran D, Markowitz LE, Unger ER, Paulose-Ram R. Prevalence of HPV in Adults Aged 18–69: United States, 2011–2014. NCHS Data Brief. 2017(280):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Melkonian SC, Henley SJ, Senkomago V, et al. Cancers Associated with Human Papillomavirus in American Indian and Alaska Native Populations - United States, 2013–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(37):1283–1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, Singleton JA, et al. National, Regional, State, and Selected Local Area Vaccination Coverage Among Adolescents Aged 13–17 Years - United States, 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(33):1109–1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holman DM, Benard V, Roland KB, Watson M, Liddon N, Stokley S. Barriers to human papillomavirus vaccination among US adolescents: a systematic review of the literature. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(1):76–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Radisic G, Chapman J, Flight I, Wilson C. Factors associated with parents’ attitudes to the HPV vaccination of their adolescent sons : A systematic review. Prev Med. 2017;95:26–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rambout L, Tashkandi M, Hopkins L, Tricco AC. Self-reported barriers and facilitators to preventive human papillomavirus vaccination among adolescent girls and young women: a systematic review. Prev Med. 2014;58:22–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kessels SJ, Marshall HS, Watson M, Braunack-Mayer AJ, Reuzel R, Tooher RL. Factors associated with HPV vaccine uptake in teenage girls: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2012;30(24):3546–3556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dibble KE, Maksut JL, Siembida EJ, Hutchison M, Bellizzi KM. A Systematic Literature Review of HPV Vaccination Barriers Among Adolescent and Young Adult Males. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2019;8(5):495–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smulian EA, Mitchell KR, Stokley S. Interventions to increase HPV vaccination coverage: A systematic review. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12(6):1566–1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walling EB, Benzoni N, Dornfeld J, et al. Interventions to Improve HPV Vaccine Uptake: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics. 2016;138(1). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fisher H, Trotter CL, Audrey S, MacDonald-Wallis K, Hickman M. Inequalities in the uptake of human papillomavirus vaccination: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42(3):896–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gallagher KE, Kadokura E, Eckert LO, et al. Factors influencing completion of multi-dose vaccine schedules in adolescents: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galbraith KV, Lechuga J, Jenerette CM, Moore LA, Palmer MH, Hamilton JB. Parental acceptance and uptake of the HPV vaccine among African-Americans and Latinos in the United States: A literature review. Soc Sci Med. 2016;159:116–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suárez P, Wallington SF, Greaney ML, Lindsay AC. Exploring HPV Knowledge, Awareness, Beliefs, Attitudes, and Vaccine Acceptability of Latino Fathers Living in the United States: An Integrative Review. J Community Health. 2019;44(4):844–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jeudin P, Liveright E, Del Carmen MG, Perkins RB. Race, ethnicity, and income factors impacting human papillomavirus vaccination rates. Clin Ther. 2014;36(1):24–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spencer JC, Calo WA, Brewer NT. Disparities and reverse disparities in HPV vaccination: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med. 2019;123:197–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jeudin P, Liveright E, del Carmen MG, Perkins RB. Race, ethnicity and income as factors for HPV vaccine acceptance and use. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9(7):1413–1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirth JM, Fuchs EL, Chang M, Fernandez ME, Berenson AB. Variations in reason for intention not to vaccinate across time, region, and by race/ethnicity, NIS-Teen (2008–2016). Vaccine. 2019;37(4):595–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Landis K, Bednarczyk RA, Gaydos LM. Correlates of HPV vaccine initiation and provider recommendation among male adolescents, 2014 NIS-Teen. Vaccine. 2018;36(24):3498–3504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Osazuwa-Peters N, Adjei Boakye E, Mohammed KA, Tobo BB, Geneus CJ, Schootman M. Not just a woman’s business! Understanding men and women’s knowledge of HPV, the HPV vaccine, and HPV-associated cancers. Prev Med. 2017;99:299–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liddon NC, Hood JE, Leichliter JS. Intent to receive HPV vaccine and reasons for not vaccinating among unvaccinated adolescent and young women: findings from the 2006–2008 National Survey of Family Growth. Vaccine. 2012;30(16):2676–2682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews. 2015;4(1):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gopalani SV, Sedani AE, Janitz AE, et al. HPV vaccination and Native Americans: protocol for a systematic review of factors associated with HPV vaccine uptake among American Indians and Alaska Natives in the USA. BMJ Open. 2020;10(9):e035658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rethlefsen ML, Kirtley S, Waffenschmidt S, et al. PRISMA-S: an extension to the PRISMA Statement for Reporting Literature Searches in Systematic Reviews. Systematic Reviews. 2021;10(1):39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cochrane Collaboration. Data collection forms for intervention reviews: RCTs and non-RCTs. Cochrane: London, UK. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 28.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Epidemiology. 2007;18(6):800–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1245–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hong QN, Gonzalez‐Reyes A, Pluye P. Improving the usefulness of a tool for appraising the quality of qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies, the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT). Journal of evaluation in clinical practice. 2018;24(3):459–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 Statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 2010;340:c332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huria T, Palmer SC, Pitama S, et al. Consolidated criteria for strengthening reporting of health research involving indigenous peoples: the CONSIDER statement. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2019;19(1):173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bowen DJ, Weiner D, Samos M, Canales MK. Exploration of New England Native American Women’s Views on Human Papillomavirus (HPV), Testing, and Vaccination. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. 2014;1(1):45–51. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bowker DM. Knowledge and beliefs regarding HPV and cervical cancer among Lakota women living on the Pine Ridge Reservation and cultural practices most predictive of cervical cancer preventive measures [Ph.D.]. Ann Arbor, New Mexico State University; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buchwald D, Muller C, Bell M, Schmidt-Grimminger D. Attitudes toward HPV vaccination among rural American Indian women and urban White women in the northern plains. Health Educ Behav. 2013;40(6):704–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hodge F. American Indian Male College Students Perception and Knowledge of Human Papillomavirus (HPV). Journal of Vaccines and Vaccination. 2014;5:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hodge FS, Itty T, Cardoza B, Samuel-Nakamura C. HPV vaccine readiness among American Indian college students. Ethn Dis. 2011;21(4):415–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kemberling M, Hagan K, Leston J, Kitka S, Provost E, Hennessy T. Alaska Native adolescent views on cervical cancer, the human papillomavirus (HPV), genital warts and the quadrivalent HPV vaccine. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2011;70(3):245–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Toffolon-Weiss M, Hagan K, Leston J, Peterson L, Provost E, Hennessy T. Alaska Native parental attitudes on cervical cancer, HPV and the HPV vaccine. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2008;67(4):363–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.White L, Yang A, Dodge L. Barriers and Facilitators to HPV Vaccine Uptake in American Indians/Alaska Natives in King County, Washington. 2018.

- 41.Winer RL, Gonzales AA, Noonan CJ, Buchwald DS. A Cluster-Randomized Trial to Evaluate a Mother-Daughter Dyadic Educational Intervention for Increasing HPV Vaccination Coverage in American Indian Girls. J Community Health. 2016;41(2):274–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bruegl AS, Bottsford-Miller JN, Bodurka DC. HPV vaccination practices among American Indian/Alaska Native providers. Gynecologic Oncology. 2016;141:132. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Duvall J, Buchwald D. Human papillomavirus vaccine policies among american Indian tribes in Washington State. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2012;25(2):131–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jacobs-Wingo JL, Jim CC, Groom AV. Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Uptake: Increase for American Indian Adolescents, 2013–2015. Am J Prev Med. 2017;53(2):162–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jim CC, Lee JW, Groom AV, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination practices among providers in Indian health service, tribal and urban Indian healthcare facilities. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2012;21(4):372–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kashani BM, Tibbits M, Potter RC, Gofin R, Westman L, Watanabe-Galloway S. Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Trends, Barriers, and Promotion Methods Among American Indian/Alaska Native and Non-Hispanic White Adolescents in Michigan 2006–2015. J Community Health. 2019;44(3):436–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schmidt-Grimminger D, Frerichs L, Black Bird AE, Workman K, Dobberpuhl M, Watanabe-Galloway S. HPV knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs among Northern Plains American Indian adolescents, parents, young adults, and health professionals. J Cancer Educ. 2013;28(2):357–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.White L, Yang A, Dodge L. Barriers and Facilitators to HPV Vaccine Uptake in American Indians/Alaska Natives in King County, Washington. Published 2018. Accessed.

- 49.Trim K, Nagji N, Elit L, Roy K. Parental Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behaviours towards Human Papillomavirus Vaccination for Their Children: A Systematic Review from 2001 to 2011. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2012;2012:921236–921236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ferrer HB, Trotter C, Hickman M, Audrey S. Barriers and facilitators to HPV vaccination of young women in high-income countries: a qualitative systematic review and evidence synthesis. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rodriguez SA, Mullen PD, Lopez DM, Savas LS, Fernández ME. Factors associated with adolescent HPV vaccination in the U.S.: A systematic review of reviews and multilevel framework to inform intervention development. Prev Med. 2020;131:105968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Loke AY, Kwan ML, Wong YT, Wong AKY. The Uptake of Human Papillomavirus Vaccination and Its Associated Factors Among Adolescents: A Systematic Review. J Prim Care Community Health. 2017;8(4):349–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hendry M, Lewis R, Clements A, Damery S, Wilkinson C. “HPV? Never heard of it!”: a systematic review of girls’ and parents’ information needs, views and preferences about human papillomavirus vaccination. Vaccine. 2013;31(45):5152–5167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Amboree TL, Darkoh C. Barriers to Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Uptake Among Racial/Ethnic Minorities: a Systematic Review. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Petereit DG, Burhansstipanov L. Establishing trusting partnerships for successful recruitment of American Indians to clinical trials. Cancer Control. 2008;15(3):260–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Guadagnolo BA, Cina K, Helbig P, et al. Medical mistrust and less satisfaction with health care among Native Americans presenting for cancer treatment. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2009;20(1):210–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gomez SL, Noone AM, Lichtensztajn DY, et al. Cancer incidence trends among Asian American populations in the United States, 1990–2008. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(15):1096–1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gopalani SV, Janitz AE, Martinez SA, Campbell JE, Chen S. HPV Vaccine Initiation and Completion Among Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander Adults, United States, 2014. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2021;33(5):502–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.